1. Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogeneous immune-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by variable involvement of peripheral and axial joints, entheses, digits, skin and nails. Beyond symptomatic burden, structural joint damage remains a major determinant of long-term disability, impaired function and reduced quality of life [

1,

2]. Although the treat-to-target paradigm and the broader availability of biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying therapies have substantially improved disease control, irreversible damage still occurs in a clinically relevant proportion of patients, and its determinants in routine practice are incompletely understood [

1,

2].

A key challenge in PsA management is the dissociation between cross-sectional measures of disease activity or patient-reported impact and the accumulated structural burden [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Composite activity-indices primarily capture current inflammatory status, whereas radiographic damage reflects the integrated effect of disease duration, past inflammatory burden, mechanical stress and treatment exposure over time [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Consequently, patients may exhibit limited clinical activity while already having structural damage or conversely show high symptom impact with little objective damage [

7]. This discordance complicates risk stratification and may contribute to missed opportunities for early intervention in patients at higher structural risk.

Several clinical and biological factors have been associated with structural progression in PsA, including longer disease duration, polyarticular phenotype, dactylitis, enthesitis, distal interphalangeal involvement, and markers of more extensive cutaneous disease [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Lifestyle and comorbidity factors, particularly smoking, have also been discussed, although their role remains controversial and may be influenced by disease severity and treatment patterns [

8]. Importantly, joint space narrowing can partially overlap with degenerative changes, making the interpretation of cartilage loss more complex in real-world cohorts unless supported by standardized scoring and careful phenotyping. In this setting, analyses that separate erosive and deforming damage from joint space narrowing, and that explore structural burden as an ordinal outcome, may provide more robust and clinically meaningful inferences.

In this study, we aimed to characterize the prevalence and patterns of structural damage in a real-world PsA cohort and to examine its relationship with current disease activity and patient-reported impact. We further sought to identify factors associated with the presence and increasing burden of structural damage, using complementary modelling strategies and multiple sensitivity analyses. By focusing on both “any damage” and damage severity, and by testing alternative definitions that exclude joint space narrowing and isolate erosive lesions, we intended to deliver a pragmatic yet methodologically robust assessment of structural burden in contemporary PsA care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted in a real-world cohort of patients with PsA followed at a tertiary rheumatology clinic. Consecutive adult patients fulfilling classification criteria for PsA and with available clinical, radiographic and patient-reported data were included. All assessments were performed as part of routine clinical care. A total of 165 patients were included in the present analysis. Clinical, laboratory, radiographic and patient-reported data were extracted from the clinical database and medical records at the time of the study visit. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Principality of Asturias (Oviedo-Spain) with endorsement #CEImPA 2025.103. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

2.2. Clinical and Demographic Variables

Demographic variables included age (years), sex, and educational level (low, medium, or higher education). Disease history variables comprised age at onset of psoriasis and arthritis, and disease duration for both conditions, calculated in years. Psoriasis characteristics were recorded using pragmatic clinical proxies, including psoriasis subtype, nail involvement, scalp involvement, intergluteal fold involvement, and extension of cutaneous disease, defined as involvement of more than three body areas. Family history of psoriasis and PsA were recorded as present or absent. Clinical phenotype at presentation and during disease evolution was classified according to standard clinical patterns, including mono-oligoarticular, polyarticular and axial involvement. Specific manifestations such as distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint involvement, dactylitis and enthesitis were recorded as present or absent, both at presentation and during disease evolution. Lifestyle variables included smoking status, which was categorized into never smoker, former smoker and current smoker based on clinical history. Comorbidities were recorded as binary variables and included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, overweight, obesity, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.

2.3. Disease Activity and Impact Measures

Peripheral joint activity was assessed by the number of tender and swollen joints. Disease activity was quantified using the Disease Activity index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) as a continuous variable. Patient-reported impact was assessed using the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease questionnaire (PsAID) and the ASAS Health Index (ASAS HI), both analyzed as continuous variables. Established thresholds were used descriptively to define low disease activity or low impact, but continuous scores were retained for all statistical analyses.

2.4. Treatment Exposure

Current and previous treatments were recorded, including the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic corticosteroids, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs). Exposure to biologic therapies was captured both as a binary variable (ever vs never) and as the number of biologic therapies used, which was considered a marker of cumulative treatment exposure and disease severity rather than a causal determinant of structural damage.

2.5. Structural Damage Assessment

Structural joint damage was assessed using conventional radiographs obtained as part of routine clinical care. For each patient, the number of joints showing erosion, deformity/ankylosis, and joint space narrowing (JSN), was recorded by the treating rheumatologist using predefined operational criteria. Structural damage was analyzed using several complementary definitions: (i) global structural damage (binary outcome), defined as the presence of at least one joint with erosions, deformity/ankylosis or JSN; (ii) damage subtypes (binary outcomes) such as erosive damage, deformity/ankylosis, and JSN were also analyzed separately; and (iii) structural damage burden (ordinal outcome), defined as the total number of affected joints (sum of erosions, deformity/ankylosis and, when applicable, JSN), and categorized into: 0 affected joints, 1–2 affected joints, and ≥3 affected joints. To minimize potential overlap with degenerative changes, additional analyses were performed excluding JSN and restricting the outcome to erosive damage only.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between patients with and without structural damage were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Associations between structural damage burden and disease activity or patient-reported impact measures (DAPSA, PsAID and ASAS HI) were explored using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Multivariable analyses were conducted using binary logistic regression for the presence of global structural damage, and ordinal logistic regression for increasing categories of structural damage burden. Covariates were selected a priori based on clinical relevance and included age, sex, disease duration, clinical phenotype, psoriasis extension, smoking status and treatment exposure. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A series of sensitivity analyses were pre-specified and performed to assess the robustness of the findings. These included alternative definitions of structural damage (erosions only; exclusion of JSN), restriction to patients with longer disease duration, and models accounting for or excluding treatment exposure. All analyses were performed using standard statistical software, and two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 165 patients with PsA were included in the analysis. Overall, 44 patients (26.7%) presented evidence of structural joint damage as previously defined. The remaining 121 patients (73.3%) had no radiographic structural damage. Patients with structural damage had a significantly longer disease duration compared with those without damage (median 12.0 [IQR 5.5–22.5] vs 6.0 [2.0–12.0] years; p=0.0002). Age showed a non-significant trend towards higher values in patients with damage (p=0.075), while sex distribution was similar between groups (p=1.00). No significant differences were observed between patients with and without structural damage regarding psoriasis extension (>3 body areas), nail involvement, scalp involvement, or intergluteal fold involvement. Similarly, no significant differences were detected for polyarticular phenotype, history of dactylitis or enthesitis, or smoking status when analyzed as categorical variables. Detailed baseline characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Prevalence and Patterns of Structural Damage

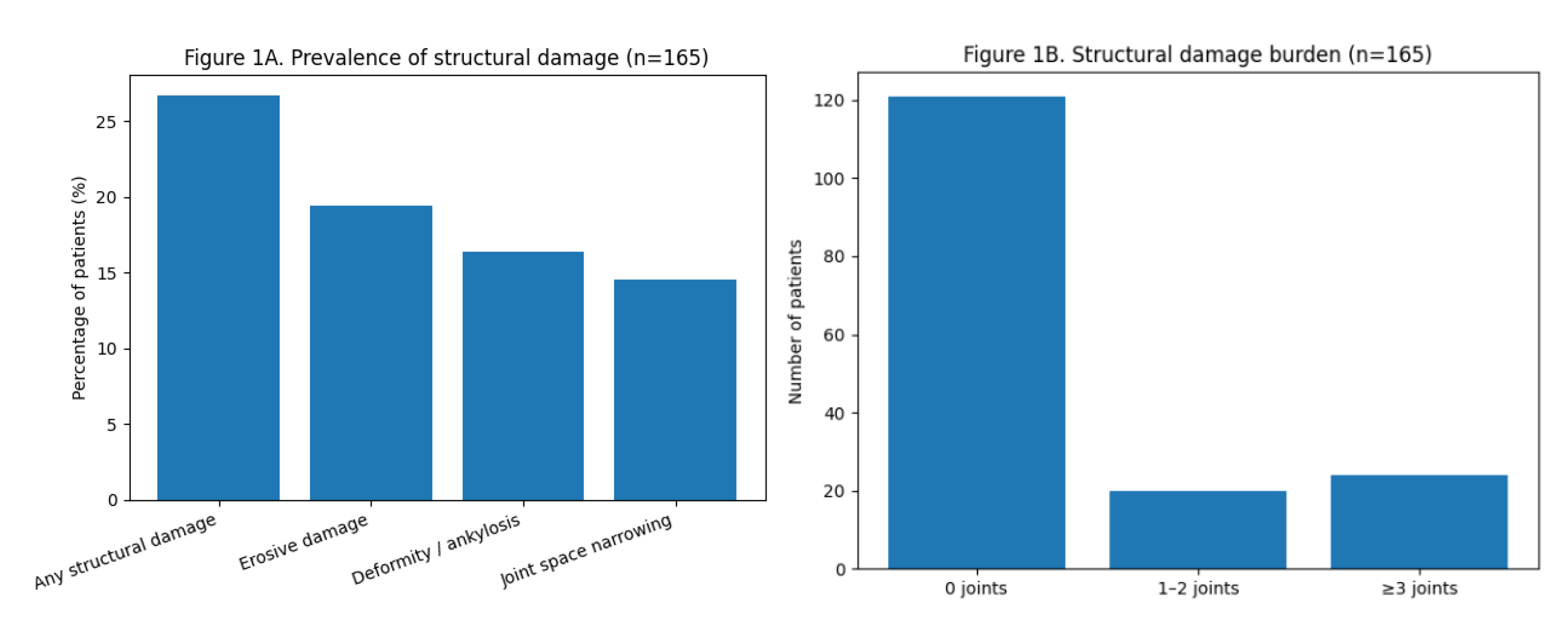

Structural damage was present in approximately one quarter of the cohort. When analyzed by subtype, erosive damage was observed in 32 patients (19.4%), deformity/ankylosis in 27 patients (16.4%), and JSN in 24 patients (14.5%). Overlap between damage subtypes was common. Regarding damage burden, most patients had no affected joints, whereas 20 patients (12.1%) had involvement of 1–2 joints and 24 patients (14.5%) had ≥3 structurally damaged joints. The distribution of damage prevalence and burden is summarized in

Figure 1.

3.3. Structural Damage and Current Disease Activity and Patient-Reported Impact

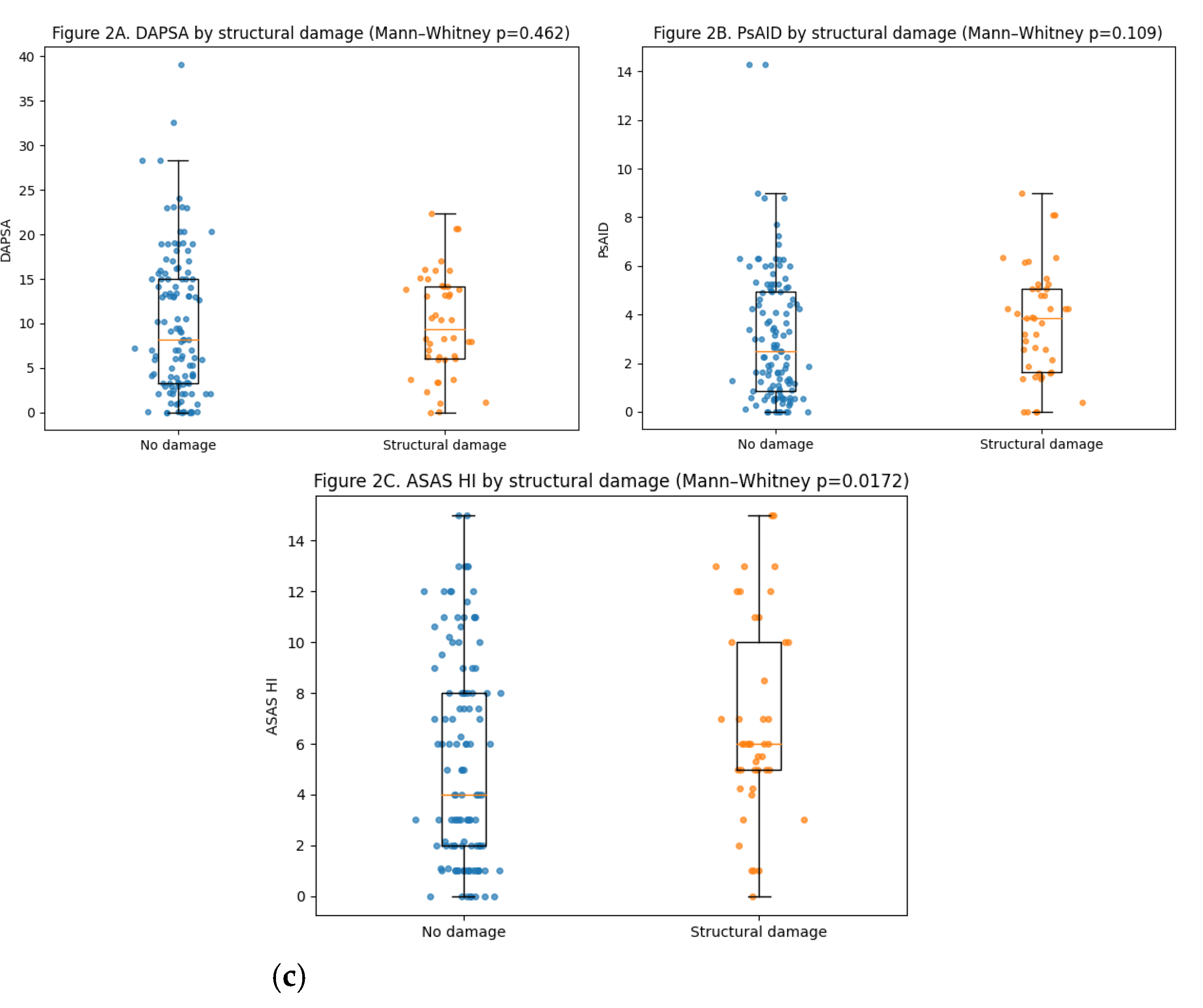

Current peripheral disease activity, assessed by DAPSA, did not differ significantly between patients with and without structural damage (median 8.2 [3.3–15.0] vs 9.4 [6.1–14.2]; p=0.46). Similarly, PsAID scores showed no statistically significant difference between groups (2.5 [0.85–4.95] vs 3.85 [1.64–5.05]; p=0.11). In contrast, patients with structural damage reported significantly worse health status as measured by the ASAS HI (6.0 [5.0–10.0] vs 4.0 [2.0–8.0]; p=0.017). The number of swollen joints was also slightly higher in patients with damage (p=0.012), although absolute differences were small.

When analyzing damage as a continuous burden (number of affected joints), no significant correlation was observed with DAPSA (ρ=0.036; p=0.64) or PsAID (ρ=0.108; p=0.17). In contrast, a weak but statistically significant correlation was found between damage burden and ASAS HI (ρ=0.166; p=0.033), as well as with the number of swollen joints (ρ=0.201; p=0.0097). These relationships are illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.4. Factors Associated with the Presence of Structural Damage

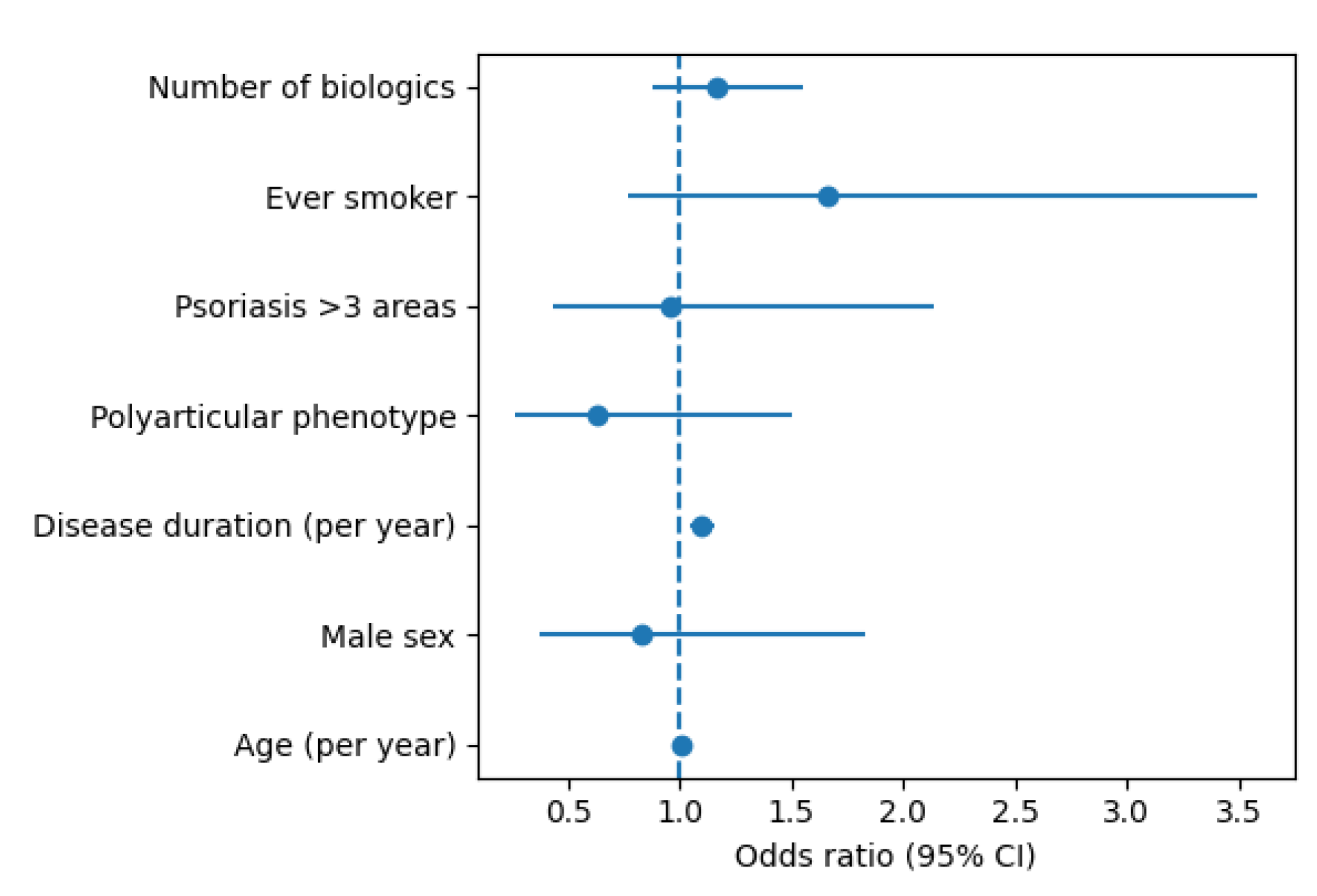

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, structural damage (binary outcome) was independently associated with longer disease duration. Each additional year of arthritis duration was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of structural damage (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05–1.15; p=0.000043). Age, sex, polyarticular phenotype, psoriasis extension (>3 body areas), smoking status (former or current vs never), and number of biologic therapies used were not independently associated with the presence of structural damage in the adjusted model. Results of the multivariable analysis are shown in

Figure 3.

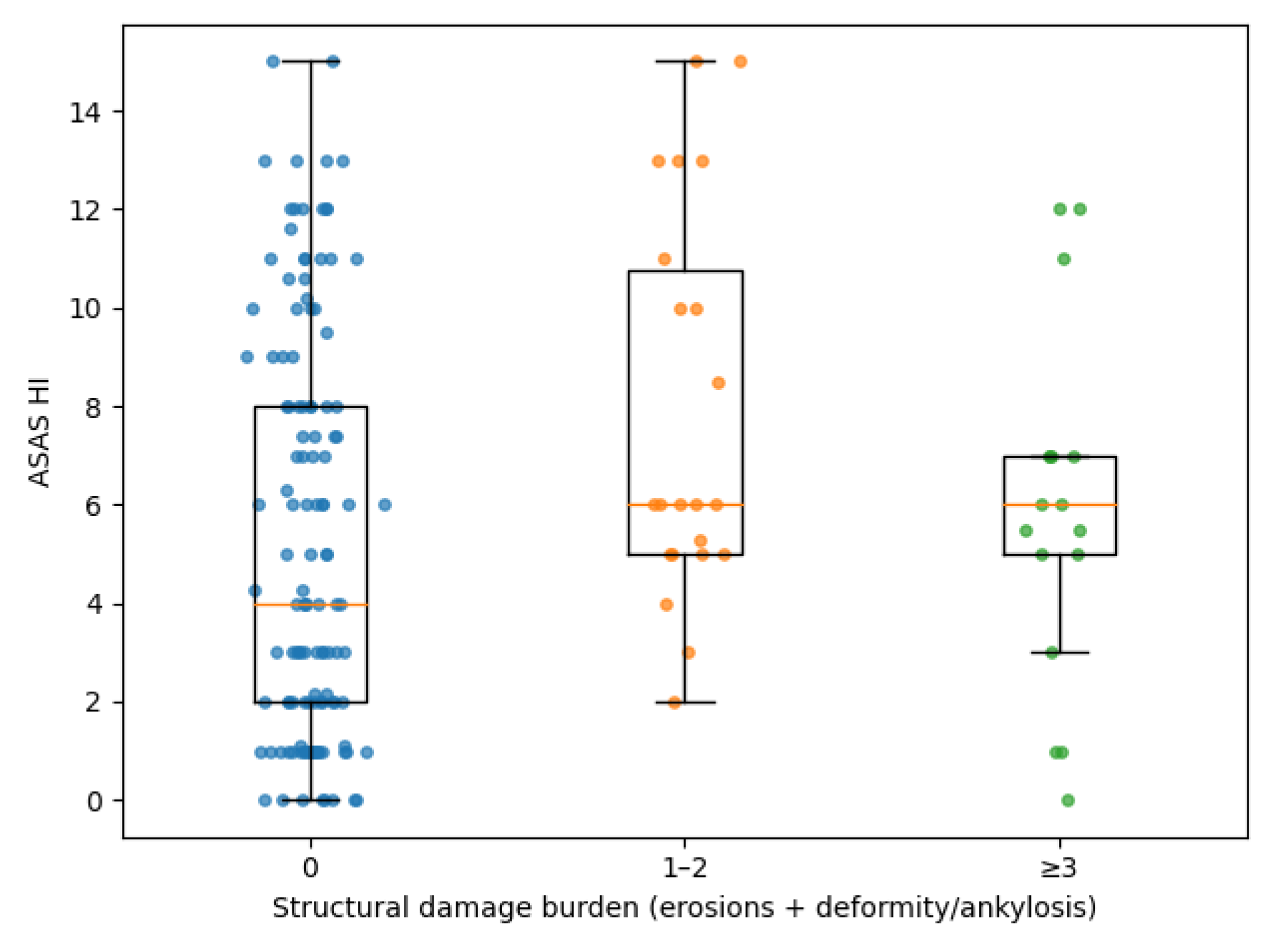

3.5. Structural Damage Burden: Ordinal Analysis

To further explore the relationship between cumulative damage and clinical characteristics, structural damage burden was analyzed as an ordinal outcome (0, 1–2, ≥3 affected joints). A clear dose–response relationship was observed between increasing damage burden and disease duration (ρ=0.307; p=6.0×10⁻5). Patients with higher damage categories also showed progressively worse ASAS HI scores (ρ=0.172; p=0.027) and a higher number of swollen joints (ρ=0.204; p=0.0086). No significant trend was observed for DAPSA or PsAID across damage categories. Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint involvement at presentation showed a strong association with increasing damage burden, with proportions rising from 22.3% in patients without damage to 70.8% in those with ≥3 damaged joints (p for trend <0.001). In ordinal multivariable regression analysis, both disease duration (OR 1.10 per year; 95% CI 1.05–1.15; p=0.00011) and DIP involvement at presentation (OR 4.29; 95% CI 1.88–9.78; p=0.00053) remained independently associated with higher damage burden, whereas age, sex, smoking status and biologic treatment exposure were not. These findings are summarized in

Figure 4.

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

When structural damage was restricted to erosive lesions only, disease duration remained significantly associated with damage (OR 1.07 per year; p=0.006), and distal interphalangeal involvement at presentation showed a strong association with erosive damage (OR 4.62; p<0.001). Excluding joint space narrowing from the damage definition did not materially alter the results, with disease duration (OR 1.10 per year; p<0.001) and distal interphalangeal involvement (OR 3.89; p=0.001) remaining significantly associated with structural damage. When the analysis was restricted to patients with a disease duration of at least 2 years (n=141), disease duration remained independently associated with structural damage (OR 1.10 per year; p<0.001), and distal interphalangeal involvement at presentation continued to show a significant association (OR 2.87; p=0.017), while psoriasis extension (>3 body areas) was not associated with damage. Finally, analyses restricted to patients treated with ≤1 biologic therapy yielded consistent results, with disease duration (OR 1.09 per year; p=0.006) and DIP involvement (OR 8.41; p<0.001) remaining strongly associated with structural damage.

4. Discussion

In this real-world cohort of patients with PsA, structural joint damage was present in approximately one quarter of patients despite contemporary management strategies. Using complementary analytical approaches, including binary and ordinal definitions of damage as well as multiple sensitivity analyses, we identified disease duration as the most robust factor associated with the presence and burden of structural damage. In contrast, current disease activity measures showed limited or no association with structural damage, whereas patient-reported health impact, as captured by the ASAS Health Index, demonstrated a modest but consistent relationship with accumulated structural burden.

The prevalence of structural damage observed in our cohort is broadly consistent with previous real-world studies, supporting the notion that irreversible joint damage remains a clinically relevant issue in PsA even in the biologic era [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, this damage was not as extensive and severe as that recorded in historical PsA series [

9,

10,

11], which may reflect the improvements in diagnosis and treatment introduced in recent years. In our series, damage was not restricted to isolated lesions but showed meaningful burden in a subset of patients, with more than one in ten patients presenting three or more structurally damaged joints. This finding underscores that structural involvement is not merely a historical artefact of untreated disease, but rather a persisting outcome in routine clinical practice, despite the wide range of current treatments for the disease. By analyzing damage subtypes separately, we confirmed that erosive and deforming/ankylosing changes constitute a substantial proportion of the overall structural burden, while JSN accounted for a smaller but non-negligible component. The consistency of our findings after excluding JSN reinforces that the observed associations are not driven by potential overlaps with degenerative changes and strengthens the inflammatory specificity of our results.

Across all analytical strategies, disease duration emerged as the most consistent and robust factor associated with both the presence and increasing burden of structural damage. Each additional year of arthritis duration conferred a measurable increase in the odds of damage, and this association was further strengthened when analyses were restricted to patients with longer-standing disease. These findings align with the concept that structural damage in PsA reflects cumulative inflammatory burden over time rather than short-term disease fluctuations [

12]. Notably, age per se did not retain an independent association with damage after adjustment, suggesting that chronological ageing is less relevant than the duration of inflammatory exposure. This distinction is clinically important, as it emphasizes the need for early disease recognition and timely therapeutic intervention to mitigate long-term structural consequences.

Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint involvement at presentation showed a particularly strong association with increasing structural damage burden, including in analyses restricted to erosive damage. This observation supports the notion that DIP involvement may represent a marker of a more aggressive structural phenotype in PsA [

13,

14]. The association persisted across multiple models and sensitivity analyses, highlighting its potential relevance for risk stratification. The link between DIP involvement and damage burden is biologically plausible, given the close anatomical relationship between joints, entheses and the nail apparatus, as well as the propensity for combined erosive and proliferative changes in this domain [

15]. While causality cannot be inferred from our cross-sectional design, the consistency of this association suggests that early identification of DIP involvement may help identify patients at higher risk of cumulative structural damage.

A central finding of our study is the weak or absent association between structural damage and current disease activity as assessed by DAPSA. Neither the presence nor the burden of damage correlated meaningfully with contemporaneous disease activity scores, reinforcing the concept that activity indices primarily capture current inflammatory status rather than accumulated structural burden [

7,

12]. This dissociation has important clinical implications. Patients with well-controlled disease activity may already harbor significant structural damage, while others with active symptoms may have little irreversible joint involvement. These findings caution against relying exclusively on cross-sectional activity measures to infer long-term structural risk and support the need for complementary assessment strategies.

In contrast to activity indices, patient-reported health impact measured by the ASAS HI showed a modest but consistent association with both the presence and increasing burden of structural damage. Although the magnitude of this association was limited, it remained statistically significant and displayed a clear dose–response pattern in ordinal analyses. The ASAS HI captures a broader construct of functioning and health status, integrating physical limitations, pain, fatigue and psychosocial aspects [

16]. Its association with structural damage likely reflects the cumulative functional consequences of irreversible joint changes rather than acute inflammatory activity. Importantly, this relationship was not observed for PsAID to the same extent, suggesting that different patient-reported instruments may capture distinct dimensions of disease impact. These findings support the complementary value of ASAS HI in PsA, particularly when structural outcomes are of interest, and suggest that it may serve as a useful proxy for accumulated disease burden in cross-sectional settings.

Smoking exposure showed a graded association with increasing damage burden in unadjusted and ordinal analyses, although this relationship did not consistently retain statistical significance in fully adjusted models. This attenuation likely reflects limited power and residual confounding, rather than the absence of a true biological effect. Smoking has been implicated in inflammatory arthritis severity and treatment response, and its potential contribution to structural damage in PsA warrants further investigation in longitudinal studies [

17,

18,

19]. Nevertheless, the observed trends in our data reinforce the relevance of smoking as a modifiable risk factor in the comprehensive management of PsA.

The number of biologic therapies used did not emerge as an independent determinant of structural damage in adjusted analyses. Importantly, sensitivity analyses excluding treatment exposure or restricting the cohort to patients with limited biologic use yielded consistent results. These findings suggest that the observed associations are not primarily driven by confounding by indication. It should be emphasized that treatment exposure in this context is likely to reflect disease severity and therapeutic history rather than a causal effect on damage development. Our results therefore support the interpretation of biologic use as a marker of cumulative disease burden rather than a determinant of structural outcomes in cross-sectional analyses.

Several methodological strengths enhance the robustness of our findings. We employed multiple complementary definitions of structural damage, including binary and ordinal outcomes, and conducted extensive sensitivity analyses to address potential sources of bias, particularly the contribution of joint space narrowing. The consistency of results across these analyses strengthens confidence in the main conclusions.

Nevertheless, some limitations merit consideration. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and does not allow assessment of structural progression over time. Structural damage was assessed using radiographs obtained in routine practice rather than standardized scoring systems, which may introduce variability in damage attribution. However, this pragmatic approach reflects real-world clinical assessment and enhances the external validity of our findings. Furthermore, the analysis of structural damage was limited to peripheral joints and did not include axial joints, which constitutes another limitation of our research. Additionally, although our cohort size is comparable to many real-world PsA studies, limited sample size may have reduced power to detect weaker associations, particularly for lifestyle and comorbidity factors. Finally, residual confounding by unmeasured variables, including historical inflammatory burden and treatment timing, cannot be excluded.

Our findings have several practical implications for PsA management. First, they reinforce the importance of early diagnosis and sustained disease control to limit cumulative inflammatory exposure and subsequent structural damage. Second, they highlight the limitations of relying solely on cross-sectional activity measures to assess long-term structural risk. Third, they support the use of complementary patient-reported outcomes, such as ASAS HI, to capture aspects of disease impact related to irreversible damage. From a clinical perspective, these results argue for periodic structural assessment and a comprehensive approach to risk stratification that integrates disease duration, clinical phenotype and patient-reported impact, alongside traditional activity indices.

5. Conclusions

Despite the current therapeutic armamentarium, structural joint damage remains prevalent in PsA and is primarily associated with cumulative disease exposure rather than current inflammatory activity. Disease duration and distal interphalangeal involvement emerge as key markers of structural burden, while patient-reported health impact captured by ASAS HI reflects accumulated damage more closely than conventional activity indices and standard impact measures such as PsAID. These findings underscore the need for long-term perspectives in PsA management and support the integration of structural and functional assessments in routine care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A. and R.Q.; methodology, P.A.; S.B.; E.P. and I.B. Software, R.Q.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, R.Q.; S.A and M.A.; investigation, P.A.; S.B.; E.P.; I.B.; M.L.; N.C. and R.Q.; resources, R.Q.; S.A. and M.A.; data curation, P.A.; M.L.; I.B.; S.B and N.C; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.; S.B. and R.Q.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, R.Q. and M.A; project administration, R.Q. and M.A.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Principality of Asturias (Oviedo-Spain) (#CEImPA 2025.103, 22-03-2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to patient confidentiality and institutional policies, raw individual-level data cannot be made publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FitzGerald O, Ogdie A, Chandran V, et al. Psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021; 7(1): 59. [CrossRef]

- Azuaga AB, Ramírez J, Cañete JD. Psoriatic Arthritis: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapies. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24(5): 4901. [CrossRef]

- Geijer M, Lindqvist U, Husmark T, et al. The Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Registry 5-year Followup: Substantial Radiographic Progression Mainly in Men with High Disease Activity and Development of Dactylitis. J Rheumatol 2015; 42(11): 2110-7. [CrossRef]

- Koc GH, Kok MR, do Rosario Y, et al. Determinants of radiographic progression in early psoriatic arthritis: insights from a real-world cohort. RMD Open 2024; 10(2): e004080. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir Isik O, Gokcen N, Temiz Karadag D, Yazici A, Cefle A. Radiological progression and predictive factors in psoriatic arthritis: insights from a decade-long retrospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 2024; 43(1): 259-267. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijde D, Gladman DD, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ. Assessing structural damage progression in psoriatic arthritis and its role as an outcome in research. Arthritis Res Ther 2020; 22(1): 18. [CrossRef]

- Queiro R, Pino M, Charca L. Structural damage is not a major driver of disease impact in patients with long-standing psoriatic arthritis undergoing systemic therapy. Joint Bone Spine 2021; 88(2): 105116. [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Goodson NJ, Robertson S, Gaffney K. Smoking in spondyloarthritis: unravelling the complexities. Rheumatology 2020; 59(7): 1472-1481. [CrossRef]

- Kane D, Stafford L, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. A prospective, clinical and radiological study of early psoriatic arthritis: an early synovitis clinic experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42(12): 1460-8. [CrossRef]

- Bond SJ, Farewell VT, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Predictors for radiological damage in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single centre. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66(3): 370-6. [CrossRef]

- Queiro-Silva R, Torre-Alonso JC, Tinturé-Eguren T, López-Lagunas I. A polyarticular onset predicts erosive and deforming disease in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62(1): 68-70. [CrossRef]

- Lubrano E, Fatica M, Queiro R, Perrotta FM. The concept of severity in psoriatic arthritis: a scoping review of the literature. J Autoimmun 2025; 157: 103494. [CrossRef]

- Mease PJ, Liu M, Rebello S, et al. Association of Nail Psoriasis with Disease Activity Measures and Impact in Psoriatic Arthritis: Data from the Corrona Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. J Rheumatol 2021; 48: 520-26.

- McGonagle D, Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, et al. Association of the clinical components in the distal interphalangeal joint synovio-entheseal complex and subsequent response to ixekizumab or adalimumab in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024; 63(11): 3115-23.

- Queiro R, Alonso S, Pinto-Tasende JA. The nail in psoriatic arthritis: new insights into prognosis and treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2024; 24(8): 715-17.

- Alonso S, Morante I, Alperi M, Queiro R. The ASAS Health Index: A New Era for Health Impact Assessment in Spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol 2022; 49(1): 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Fatica M, Çela E, Ferraioli M, et al. The Effects of Smoking, Alcohol, and Dietary Habits on the Progression and Management of Spondyloarthritis. J Pers Med 2024; 14(12): 1114. [CrossRef]

- Solmaz D, Kalyoncu U, Tinazzi I, et al. Current Smoking Is Increased in Axial Psoriatic Arthritis and Radiographic Sacroiliitis. J Rheumatol 2019: jrheum.190722. [CrossRef]

- Kharouf F, Maldonado-Ficco H, Gao S, et al. The association between cigarette smoking and radiographic progression in Psoriatic Arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2025; 71:152653. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).