1. Introduction

Distributed training has become essential for modern deep learning as model complexity and dataset sizes continue to grow exponentially. The parameter server framework [

1,

2] has emerged as a dominant architecture for scaling machine learning workloads across multiple computing nodes. This framework typically employs a centralized server maintaining global model parameters while multiple worker nodes compute gradients on data partitions. The efficiency of such distributed systems heavily depends on the synchronization paradigm governing how workers exchange gradient updates and retrieve updated parameters.

Three primary synchronization paradigms have been established in literature: Bulk Synchronous Parallel (BSP) [

3], Asynchronous Parallel (ASP) [

2,

4], and Stale Synchronous Parallel (SSP) [

5,

6]. BSP ensures strict consistency by requiring all workers to synchronize at every iteration, guaranteeing convergence but suffering from straggler problems where fast workers wait for slow ones. ASP eliminates waiting entirely, allowing maximum hardware utilization but risking convergence issues due to gradient staleness. SSP strikes a middle ground by permitting bounded staleness through a user-specified threshold that limits how far ahead fast workers can proceed.

While SSP represents a practical compromise, its fixed staleness threshold presents significant limitations in production environments. Determining an optimal threshold requires extensive manual tuning through trial and error, which becomes increasingly costly as model complexity grows. Furthermore, a single fixed value cannot adapt to dynamic runtime conditions where worker performance may vary due to resource contention, network fluctuations, or heterogeneous hardware. These limitations motivate the need for adaptive synchronization mechanisms that can automatically adjust staleness bounds based on real-time system behavior.

This paper introduces LagTuner, a dynamic staleness orchestration system that automatically adjusts synchronization boundaries during training runtime. Our approach eliminates the need for manual threshold specification while maintaining convergence guarantees through formal regret bounds. The core innovation lies in a server-side synchronization controller that uses recent worker performance telemetry to predict optimal staleness allowances, minimizing waiting time while preserving training stability.

The contributions of this work are threefold: (1) We present a novel adaptive staleness control mechanism that dynamically adjusts synchronization thresholds based on real-time worker performance; (2) We provide theoretical analysis demonstrating that our approach maintains the same convergence guarantees as fixed-threshold SSP; (3) We empirically validate our method across diverse neural architectures and hardware configurations, showing consistent improvements over existing synchronization paradigms.

2. Related Work

Our work on adaptive staleness control intersects with broader research in scalable systems, adaptive algorithms, and reliable distributed computing. The challenge of optimizing performance in dynamic, heterogeneous environments is a common theme across these domains.

In the realm of large-scale data processing and model optimization, Muneer [

7] explores flexible topic extraction using Gensim’s Online LDA, demonstrating the importance of adaptive parameter tuning for handling massive feedback datasets. Further advancing automated workflows, Muneer [

8] investigates the use of collective intelligence with LLM architectures for agile sprint planning, highlighting how multi-agent systems can enhance complex decision-making processes—a concept relevant to intelligent orchestration in distributed training.

Optimization techniques are crucial for system performance. Ramakrishnan et al. [

9] present a hybrid decision tree and genetic algorithm for enhanced classification accuracy, emphasizing the role of adaptive feature selection. This aligns with our goal of dynamically selecting optimal parameters (staleness thresholds) for improved performance. Similarly, Ramakrishnan [

10] applies genetic algorithms to circuit design, showcasing the use of evolutionary optimization in complex system design, while Ramakrishnan et al. [

11] study the adoption of language features, reflecting on how systems must evolve with technological advancements.

The infrastructure for running these systems is equally critical. Ramakrishnan and Nayak [

12] discuss the integration of Cloud, Edge, and IoT, underscoring the need for dynamic resource orchestration in heterogeneous environments—a challenge directly parallel to managing heterogeneous workers in a training cluster. Ramakrishnan [

13] provides a financial and technological analysis of cloud deployment on AWS, highlighting the trade-offs between performance, cost, and scalability that are also central to efficient distributed training.

Recent trends in decentralized and reliable system design offer valuable insights. Ramakrishnan and Lekkala [

14] propose a blockchain-based solution for decentralized GitHub management, promoting transparent governance. Ramakrishnan et al. [

15] enhance distributed system reliability through fine-grained fault injection and tracing, illustrating how precise control and observability are fundamental to building resilient systems, much like how LagTuner uses telemetry for adaptive control.

Finally, the work of Thomas spans several areas relevant to adaptive and user-centric systems. Thomas [

16] introduces an interactive graph-based file system, demonstrating how intuitive data representation enhances usability. Research on network security [

17], modernizing legacy systems [

18], and digital privacy [

19] emphasizes the need for adaptive, secure, and scalable architectures. Further work on software sustainability [

20], breaking healthcare data silos [

21], scalable AI explainability [

22], and dynamic health record management [

23] collectively highlights the critical role of intelligent, feedback-driven systems across various domains.

LagTuner builds upon these foundational ideas by introducing a server-driven orchestration layer that dynamically adjusts staleness thresholds using real-time telemetry, aligning with the broader trend toward adaptive, scalable, and observable systems evident in contemporary computing research.

3. System Architecture and Design

3.1. Parameter Server Framework

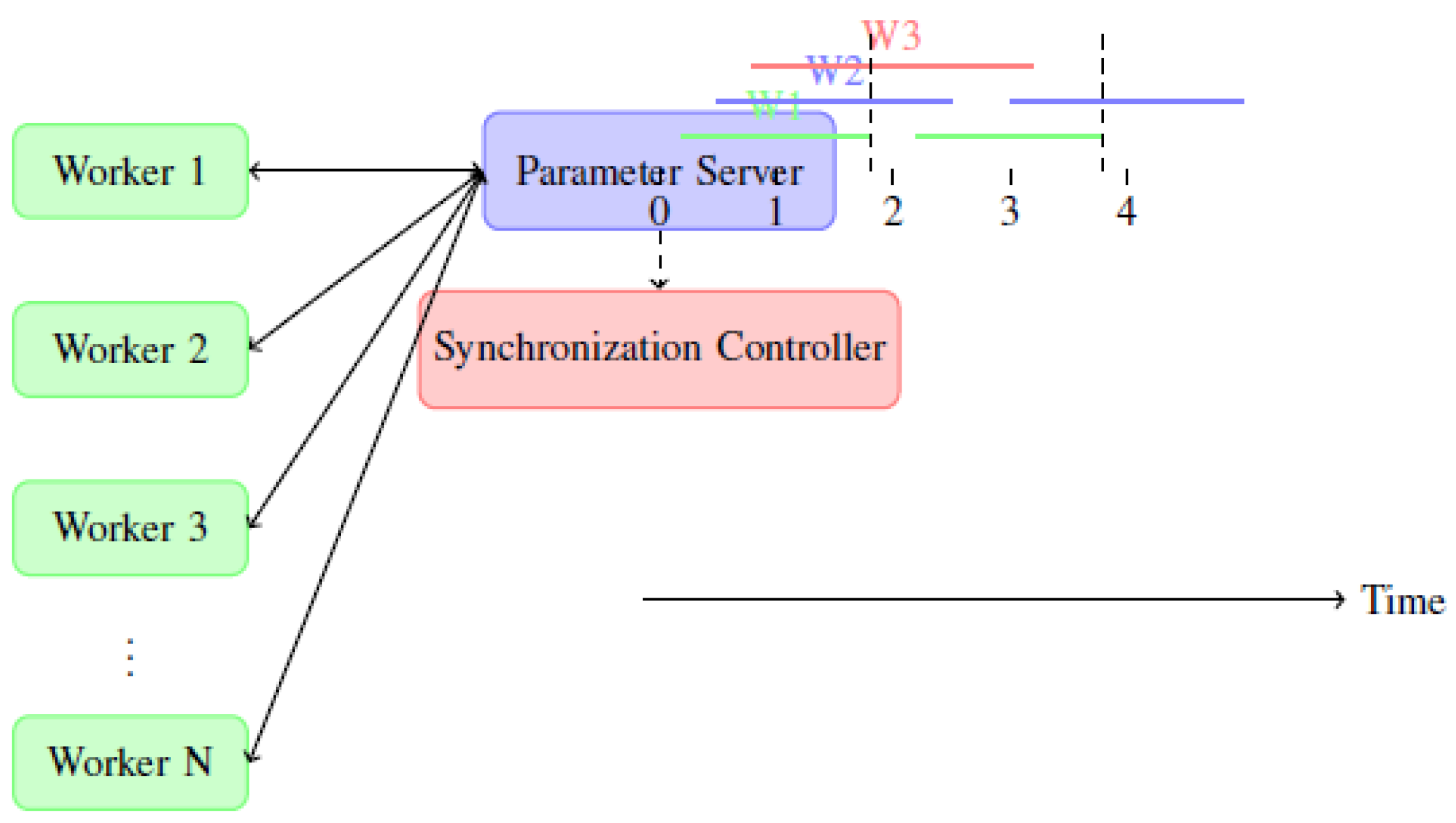

The LagTuner system builds upon the standard parameter server architecture, consisting of a logical server node and multiple worker nodes. The server maintains the global model parameters and coordinates synchronization, while workers store model replicas and process training data partitions. Each worker iteratively performs four key operations: (1) computing gradients on a mini-batch using local parameters, (2) pushing gradients to the server, (3) pulling updated global parameters from the server, and (4) updating local parameters.

The time between consecutive push operations from a worker defines its iteration interval, which includes both computation time (forward/backward passes) and communication time (push/pull operations). In homogeneous environments with stable networks, iteration intervals tend to be consistent across workers and over time. However, real-world deployments often exhibit variability due to hardware heterogeneity, resource contention, or network fluctuations.

3.2. Dynamic Staleness Control

The core innovation in LagTuner is the dynamic adjustment of staleness thresholds during training. Unlike fixed-threshold SSP that uses a constant staleness bound s, our system operates with a configurable range where represents the minimum staleness guarantee and the maximum permitted staleness. The synchronization controller dynamically selects optimal thresholds for each worker based on recent performance metrics.

The controller maintains telemetry data for each worker, including timestamps of recent push operations and computed iteration intervals. Using this historical data, it simulates future iteration timelines to identify threshold values that minimize expected waiting time while maintaining bounded staleness. This approach allows different workers to operate with different staleness thresholds and permits thresholds to evolve over time as system conditions change.

The dynamic adjustment process focuses particularly on the fastest worker at each synchronization decision point. When a worker’s iteration count exceeds the slowest worker by , the controller determines how many additional iterations () the worker should be permitted before synchronization. This decision aims to minimize the total waiting time while preventing excessive staleness that could impair convergence.

3.3. Synchronization Controller

The synchronization controller implements the core adaptive logic of LagTuner. Algorithm 1 presents the complete procedure executed by workers and server during training. Workers follow the standard parameter server workflow: pulling current parameters, computing gradients, and pushing updates. The server incorporates the adaptive synchronization logic when processing push requests.

For each push request, the server first updates global parameters using the received gradients. It then checks whether the sending worker has exceeded the lower staleness bound relative to the slowest worker. If not, the worker immediately receives permission to continue. If the bound is exceeded and the worker is currently the fastest, the synchronization controller is invoked to determine the optimal number of extra iterations.

The controller’s decision process (Algorithm 2) uses recent push timestamps to simulate future iterations for both the fastest and slowest workers. It evaluates potential waiting times for different values of

where

. The value

that minimizes projected waiting time is selected and returned to the server procedure. This value determines how many additional iterations the worker may complete before requiring synchronization.

|

Algorithm 1:LagTuner Worker and Server Procedures |

- 1:

procedureWorker(p at iteration ) - 2:

Wait until receiving from Server - 3:

Pull weights from Server - 4:

Replace local weights with

- 5:

Compute gradient

- 6:

Push to Server - 7:

end procedure - 8:

procedureServer(at iteration ) - 9:

Upon receiving push with from worker p: - 10:

▹ Increment worker’s iteration count - 11:

Update server weights with (aggregate if multiple updates) - 12:

if then▹ Worker has extra iterations remaining - 13:

- 14:

Send to worker p

- 15:

else if then▹ Within lower bound - 16:

Send to worker p

- 17:

else▹ Exceeds lower bound - 18:

if p is the fastest worker then

- 19:

synchronization_controller

- 20:

end if

- 21:

if then

- 22:

Send to worker p

- 23:

else

- 24:

Wait until ▹ Force synchronization - 25:

Send to worker p

- 26:

end if

- 27:

end if

- 28:

end procedure |

|

Algorithm 2:Synchronization Controller |

-

Require:

Timestamps of recent push requests from all workers -

Ensure:

Optimal extra iterations for fastest worker - 1:

procedureSynchronization_Controller(, ) - 2:

Maintain table of recent push timestamps for all workers - 3:

Identify fastest worker p and slowest worker n

- 4:

- 5:

Initialize array of size

- 6:

for to do

- 7:

Simulate next r iterations for worker p using recent intervals - 8:

Simulate corresponding iterations for worker n

- 9:

Estimate waiting time for synchronization - 10:

end for

- 11:

▹ Find minimum waiting time - 12:

return

- 13:

end procedure |

4. Theoretical Analysis

4.1. Convergence Guarantees

We establish convergence guarantees for LagTuner by analyzing its behavior under the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization framework. Our analysis builds upon the regret bound formulation for SSP [

5], extending it to accommodate dynamic threshold adjustment.

Consider the optimization problem where each is a convex loss function. Under the parameter server framework with P workers, let represent the potentially stale parameter state used for gradient computation at iteration t. The regret measures the difference between the cumulative loss of our algorithm and the optimal solution .

Theorem 1

(SGD under SSP [

5]).

Suppose is convex and each is L-Lipschitz with constant L. Let with learning rate and . Assume the distance for some constant F. Then SSP with staleness threshold s achieves regret bound:

Thus since .

Theorem 2

(SGD under LagTuner).

Under the same conditions as Theorem 1, with staleness threshold range and representing the dynamically selected threshold adjustment, LagTuner achieves regret bound:

Thus since .

Proof Sketch: The dynamic threshold always satisfies by construction. Since Theorem 1 holds for any fixed , it specifically holds for . The dynamic selection of does not affect the regret bound form, only the specific value within the bounded range. Therefore, LagTuner maintains the regret bound characteristic of bounded staleness methods.

4.2. Consistency Model

LagTuner operates under the consistency model of bounded staleness, ensuring that parameter views across workers never diverge beyond a specified limit. Formally, for any two workers i and j at iterations and respectively, the system guarantees at all times. This bound ensures that gradient updates incorporate limited staleness, preventing the divergence issues that plague fully asynchronous approaches.

The dynamic adjustment of thresholds within the range allows the system to adapt to current conditions while maintaining this consistency guarantee. The lower bound ensures minimum consistency standards, while the upper bound prevents excessive staleness that could impair convergence.

Figure 1.

LagTuner system architecture showing parameter server with synchronization controller and worker nodes. The timeline illustrates variable iteration intervals across workers and dynamic synchronization points.

Figure 1.

LagTuner system architecture showing parameter server with synchronization controller and worker nodes. The timeline illustrates variable iteration intervals across workers and dynamic synchronization points.

5. Experimental Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

We evaluated LagTuner against established synchronization paradigms (BSP, ASP, SSP) across multiple neural architectures and hardware configurations. Our experiments used the SOSCIP GPU cluster [

24] with up to four IBM POWERS servers, each equipped with four NVIDIA P100 GPUs, 512GB RAM, and 20 CPU cores. Servers interconnected via Infiniband EDR with 100Gbps dedicated bandwidth.

To assess performance under heterogeneity, we created a mixed-GPU environment using Docker containers on a server with NVIDIA GTX1060 and GTX1080 Ti GPUs. This configuration represents realistic deployment scenarios where hardware upgrades occur gradually over time.

We employed two standard image classification benchmarks: CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 [

25], each containing 50,000 training and 10,000 test images. CIFAR-10 has 10 classes while CIFAR-100 has 100 classes, providing varying task difficulties.

Our model selection included a downsized AlexNet [

26] (3 convolutional layers, 2 fully-connected layers), ResNet-50, and ResNet-110 [

27]. The AlexNet modification enabled practical training within 24-hour job limits while maintaining representative architecture characteristics.

For LagTuner, we set and (), providing substantial adaptation range while maintaining bounded staleness. We compared against SSP with fixed thresholds from 3 to 15 to evaluate both against individual configurations and their average performance.

Table 1.

Experimental Configuration Summary.

Table 1.

Experimental Configuration Summary.

| Component |

Configuration |

Parameters |

| Hardware |

SOSCIP Cluster: 4× IBM POWERS, 4× NVIDIA P100/server |

512GB RAM, 20 cores |

| |

Heterogeneous: GTX1060 + GTX1080 Ti |

64GB RAM, 8 cores |

| Datasets |

CIFAR-10 |

10 classes, 50K train, 10K test |

| |

CIFAR-100 |

100 classes, 50K train, 10K test |

| Models |

AlexNet (downsized) |

3 conv, 2 FC layers |

| |

ResNet-50 |

50-layer residual network |

| |

ResNet-110 |

110-layer residual network |

| Training |

Batch size: 128, Epochs: 300 |

Learning rate: 0.001 (AlexNet), 0.05 (ResNet) |

| Synchronization |

BSP, ASP, SSP ( to 15), LagTuner (, ) |

|

5.2. Implementation Details

We implemented LagTuner within the MXNet framework [

28], which provides native support for BSP and ASP paradigms. Our implementation added the synchronization controller and modified the parameter server logic to support dynamic threshold adjustment. Each experimental run used 4 workers, with each worker utilizing 4 GPUs (16 total model replicas). Workers aggregated gradients across their local GPUs before pushing to the server.

We conducted three independent runs for each configuration and reported median results based on test accuracy. This approach mitigated variance from random initialization and transient system conditions. All experiments used the same random seeds where applicable to ensure fair comparison.

Training hyperparameters followed standard practices: batch size 128, learning rate 0.001 for AlexNet and 0.05 for ResNet models. For ResNet training, we applied learning rate decay of 0.1 at epochs 200 and 250. These settings aligned with common configurations from literature [

26,

27].

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Performance on Homogeneous Clusters

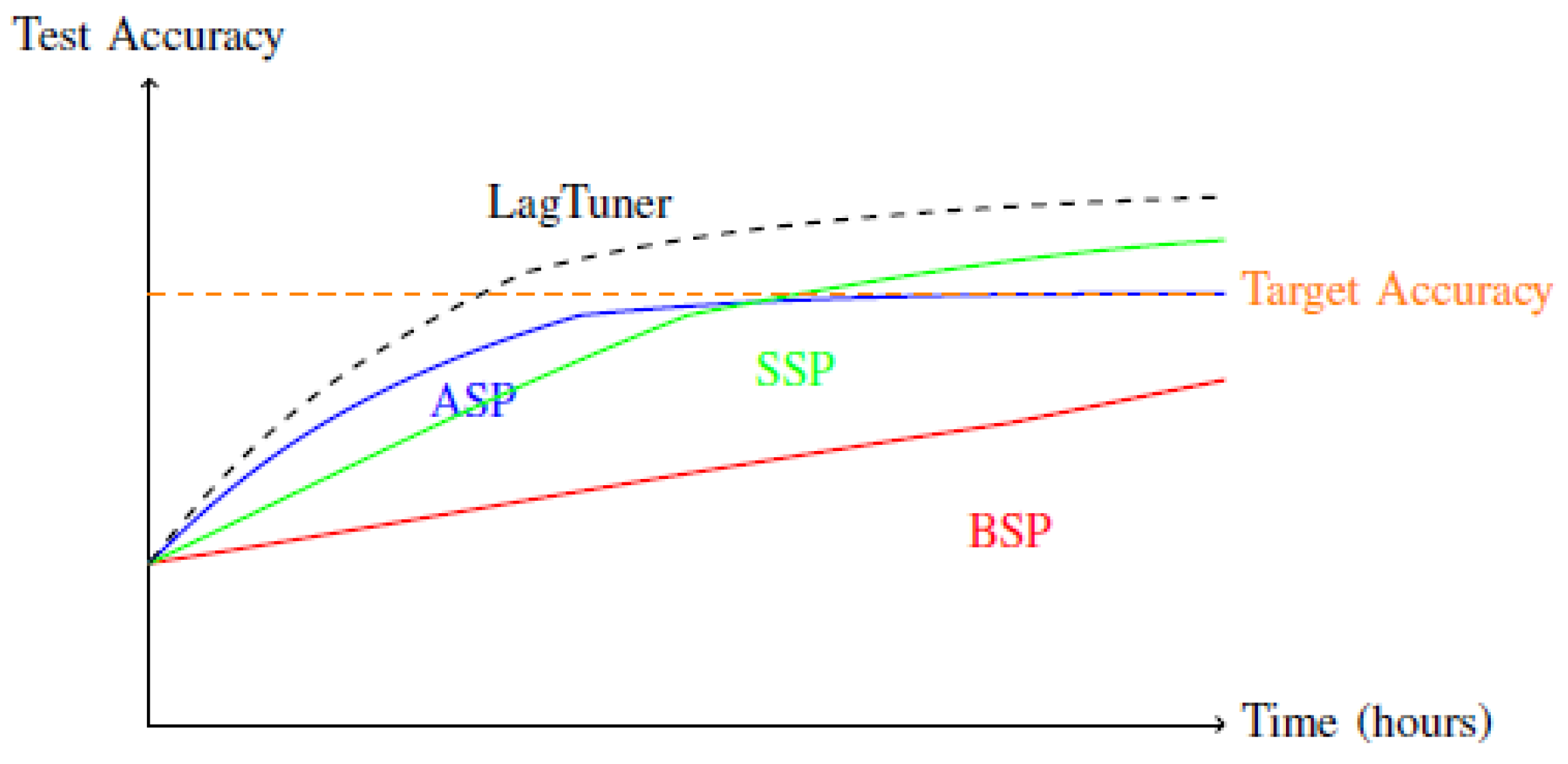

On homogeneous GPU clusters, LagTuner demonstrated consistent advantages over baseline approaches. For AlexNet on CIFAR-10 (

Figure 2), LagTuner converged to high accuracy faster than fixed-threshold SSP variants and maintained stability unlike ASP. While BSP eventually reached the highest accuracy given sufficient time, its convergence rate was significantly slower due to synchronization overhead.

The performance advantage of LagTuner stemmed from its adaptive threshold selection, which minimized waiting time while preventing excessive staleness. In scenarios where worker performance was relatively uniform, the system typically selected thresholds near the middle of the permitted range, balancing throughput and consistency effectively.

For ResNet architectures on CIFAR-100, we observed different relative performance patterns. BSP completed 300 epochs fastest due to reduced communication overhead in convolutional-heavy networks, but achieved lower final accuracy than asynchronous methods. LagTuner matched the convergence rate of ASP and SSP while maintaining slightly higher final accuracy, demonstrating its ability to adapt to different network architectures.

6.2. Performance on Heterogeneous Clusters

Heterogeneous environments revealed more substantial advantages for LagTuner. With mixed GPU models (GTX1060 and GTX1080 Ti), worker iteration times varied significantly, creating challenging conditions for fixed-threshold approaches. As shown in

Table 2, LagTuner achieved target accuracies 45-58% faster than SSP with various fixed thresholds.

The adaptive threshold selection proved particularly valuable in these conditions, automatically adjusting to the performance disparity between workers. When faster workers significantly outpaced slower ones, LagTuner permitted additional iterations only when doing so reduced expected waiting time. This dynamic adjustment prevented the excessive synchronization that plagued BSP and small-threshold SSP, while avoiding the instability of ASP and large-threshold SSP.

Figure 4 illustrates the convergence behavior on heterogeneous hardware. LagTuner reached higher accuracy levels faster than all SSP variants, demonstrating its ability to optimize throughput without sacrificing final model quality. The performance gap widened at higher accuracy targets, where consistent convergence becomes more challenging under significant staleness.

6.3. Architecture-Specific Behavior

Our experiments revealed distinct synchronization behavior patterns across different neural architectures. Networks containing fully-connected layers (like AlexNet) exhibited different characteristics than pure convolutional networks (like ResNet).

For architectures with fully-connected layers, asynchronous methods (ASP, SSP, LagTuner) consistently outperformed BSP in time-to-accuracy metrics. These networks have extensive parameter sets requiring significant communication, making synchronization overhead substantial. LagTuner achieved the best balance, converging faster than fixed-threshold SSP while maintaining higher final accuracy than ASP.

For convolutional networks, BSP showed competitive epoch completion times due to reduced parameter communication relative to computation. However, asynchronous methods often achieved better final accuracy, potentially because gradient staleness acts as a regularizer [

29]. LagTuner consistently matched or exceeded the accuracy of fixed-threshold SSP while maintaining similar convergence rates.

This architectural differentiation highlights the importance of adaptive synchronization. Different network architectures and layer compositions benefit from different staleness thresholds, making fixed-threshold approaches suboptimal across diverse workloads. LagTuner’s runtime adaptation allows it to automatically adjust to these varying requirements.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

We presented LagTuner, an adaptive staleness orchestration system for parameter-server distributed training. By dynamically adjusting synchronization thresholds based on real-time performance telemetry, our approach eliminates the need for manual threshold tuning while maintaining convergence guarantees. Theoretical analysis established formal regret bounds equivalent to fixed-threshold SSP, and empirical evaluation demonstrated consistent advantages across diverse neural architectures and hardware configurations.

The adaptive nature of LagTuner proved particularly valuable in heterogeneous environments, where it significantly outperformed fixed-threshold approaches. Even in homogeneous settings, it provided more stable convergence than ASP and faster convergence than BSP and small-threshold SSP. These advantages position adaptive staleness control as a practical primitive for production distributed training systems.

Future work will explore several directions. First, we plan to investigate adaptation mechanisms for unstable network conditions, where communication latency varies significantly over time. Second, we will extend the approach to federated learning scenarios with non-IID data distributions. Finally, we will explore integration with gradient compression techniques to optimize communication efficiency further.

The LagTuner system demonstrates that intelligent synchronization control can substantially improve distributed training efficiency without compromising model quality. By treating gradient exchange as a feedback-controlled service rather than a fixed protocol, we can better utilize heterogeneous computational resources while maintaining robust convergence across diverse deep learning workloads.

References

- Li, M.; Andersen, D.G.; Park, J.W.; Smola, A.J.; Ahmed, A.; Josifovski, V.; Long, J.; Shekita, E.J.; Su, B.Y. Scaling distributed machine learning with the parameter server. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, 2014; pp. 583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Senior, A.; Tucker, P.; Yang, K.; Le, Q.V.; et al. Large scale distributed deep networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2012; pp. 1223–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbessiotis, A.V.; Valiant, L.G. Direct bulk-synchronous parallel algorithms; Elsevier, 1994; Vol. 22, pp. 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Recht, B.; Re, C.; Wright, S.; Niu, F. Hogwild: A lock-free approach to parallelizing stochastic gradient descent. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2011; pp. 693–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Q.; Cipar, J.; Cui, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.K.; Gibbons, P.B.; Gibson, G.A.; Ganger, G.; Xing, E.P. More effective distributed ml via a stale synchronous parallel parameter server. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2013; pp. 1223–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Cipar, J.; Ho, Q.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, S.; Kumar, A.; Wei, J.; Dai, W.; Ganger, G.R.; Gibbons, P.B.; et al. Exploiting bounded staleness to speed up big data analytics. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference, 2014; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Muneer, T.A.S. Flexible and Scalable Customer Feedback Topic Extraction Using Gensim’s Online LDA. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Smart & Sustainable Technology (INCSST), 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, T.A.S. Leveraging Collective Intelligence in Agile Sprint Planning: A Comparative Study of LLM Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Smart & Sustainable Technology (INCSST), 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Lekkala, J.J. Hybrid Decision Tree and Genetic Algorithm for Enhanced Classification Accuracy. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K. Genetic Algorithm Optimization in Circuit Design. In Proceedings of the 2025 1st International Conference on AIML-Applications for Engineering & Technology (ICAET), 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Lekkala, J.J. Evolution and Adoption of Java Programming Features: A Comparative Study of Generics and Lambda Expressions. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Nayak, A.; Lekkala, J.J. Integrating Cloud, Edge, and IoT. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K. Financial and Technological Considerations for Deploying Applications on Cloud Computing Platforms: A case Study of AWS. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Lekkala, J.J. Decentralized GitHub Management: Blockchain Solution. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Sadineni, M.; Lekkala, J.J. Enhancing Distributed System Reliability through Request-Level Fault Injection and Fine-Grained Tracing. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Atlas: An Interactive Graph-Based File System for Enhanced Document Relationship Visualization. In Zenodo; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Redefining Network Security: The Expansive Role of ACLs in Modern Cisco Deployments. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Modernizing Legacy Systems through Scalable Microservices and DevOps Practices. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Navigating the Digital Privacy Paradox: Balancing Security, Surveillance, and User Control in the Modern Era. Zenodo 2025. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Sustaining Software Relevance: Enhancing Evolutionary Capacity through Maintainable Architecture and Quality Metrics. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Breaking Data Silos in Healthcare: A Novel Framework for Standardizing and Integrating NHS Medical Data for Advanced Analytics. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Enhancing Scalability and Transparency in AI-Driven Credit Scoring: Optimizing Explainability for Large-Scale Financial Systems. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Empowering Healthcare with Dynamic Control: A Strategic Framework for Personal Health Record Management. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOSCIP. SOSCIP GPU. https://docs.scinet.utoronto.ca/index.php/SOSCIP_GPU, 2018. Accessed: 2018-08-01.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Technical report, Citeseer, 2009.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Lin, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, M.; Xiao, T.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. Mxnet: A flexible and efficient machine learning library for heterogeneous distributed systems. In Proceedings of the arXiv preprint arXiv:1512.01274, 2015.

- Neelakantan, A.; Vilnis, L.; Le, Q.V.; Sutskever, I.; Kaiser, L.; Kurach, K.; Martens, J. Adding gradient noise improves learning for very deep networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).