1. Introduction

Preference-based fine-tuning (PFT) has become crucial for aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences and values. Prominent methods such as reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) adopt policy gradient techniques to adjust model behavior based on reward estimates derived from human or surrogate preference models [

1]. Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) treats preference alignment as a differentiable pairwise ranking problem, optimizing losses directly over model scores [

2]. These methods, while effective, require precise gradient propagation through complex preference networks, leading to high computational and memory costs.

Feedback alignment (FA) replaces exact error gradients with fixed random feedback matrices, significantly reducing weight transport and enabling parallel hardware implementations. Variants such as Direct FA (DFA) and sign-symmetric FA demonstrate comparable performance to backpropagation on vision tasks. Yet, FA’s application to PFT introduces challenges: pairwise losses induce non-smooth landscapes; human feedback is inherently noisy; and transformer depths amplify misalignment across layers. This study rigorously examines FA’s limits in PFT, making the following contributions:

These insights pave the way for efficient, hardware-friendly PFT of LLMs under practical noise and depth conditions[

2].

2. Mathematical Preliminaries

In this section we introduce the notation and key tools that we will use throughout the paper. We begin by stating the formal setting for preference learning and then recall a few fundamental inequalities and norms which will be instrumental in our subsequent analysis.

2.1. Notation

Let

denote the (unknown) data distribution over prompt–response pairs and preference labels. Concretely, each sample from

is a triplet

, where

and

is judged by a human or oracle to be strictly preferred over

. We assume access to

N i.i.d. draws

from

.

Our model is a deep network parameterized by weights

where layer

l has weight matrix

. We write

for the input dimension (possibly the embedding size of

x) and

for the scalar output dimension (the score). For any matrix

M, we denote its spectral norm (largest singular value) by

and its Frobenius norm by

. In addition, we will use

to denote a fixed, random feedback matrix in layer

l when analyzing Feedback Alignment[

6,

7].

2.2. Preference Losses

Training is driven by a surrogate loss that encourages the model to score the preferred response higher than the dispreferred one. Two common choices are:

where

ℓ is one of the above pairwise losses. Our convergence analysis will treat both cases in parallel, since their gradients obey similar Lipschitz and curvature bounds.

2.3. Alignment Metrics

To quantify how well Feedback Alignment (FA) approximates true backpropagation, we introduce the following measures at iteration t:

Layer-wise Alignment Error:

measures the discrepancy between the transpose of the forward weights and the fixed feedback matrix at layer

l.

Cosine Similarity of Gradients:

where

is the local error signal at layer

l. A value of

close to 1 indicates that FA’s updates are well-aligned with true gradients.

2.4. Key Lemmas

We will invoke two standard results from matrix analysis and differential inequalities:

Lemma 1 (Spectral–Frobenius Inequality).

For any matrix ,

These will allow us to bound error-propagation recurrences and derive convergence rates.

3. Problem Formulation

We consider training by iterative gradient updates of the form:

where

is the learning rate and

is the update direction. In

backpropagation,

is the true gradient

, whereas in

Feedback Alignment we replace each layer’s partial derivative

with the FA approximation:

where

is the backpropagated local error (using the forward weights for all subsequent layers).

Our goal is to characterize how the alignment error

evolves over time under FA updates. A key step is to derive a recurrence of the form

where:

is a lower bound on the minimum singular value of , ensuring strong convexity in the layer’s weights,

is a Lipschitz constant controlling how perturbations in layer affect the error at layer l,

captures any bias introduced by noise or nonzero initialization misalignment[

8].

By applying the discrete Grönwall inequality to the coupled system of recurrences across layers, we will establish that geometrically fast, provided is chosen small enough. Thus FA achieves approximate gradient alignment and converges to a neighborhood of a critical point of .

In the next section we rigorously derive (

1) and quantify each constant in terms of network dimensions, depth

L, and the statistics of the feedback matrices

.

4. Theoretical Analysis

In this section we delve deeper into the dynamics of alignment error under Feedback Alignment (FA). We first unroll the layer-wise recurrence to obtain an explicit bound, then analyze convergence in the special case of linear networks. We extend to nonlinear transformer blocks by leveraging Lipschitz continuity, and finally quantify how stochastic label noise can destabilize alignment[

9].

Figure 1.

Alignment over Layers

Figure 1.

Alignment over Layers

4.1. Unrolled Error Propagation

Starting from the one-step recurrence

we unroll this inequality over

t steps to obtain

Here:

The first term reflects exponential decay of the initial misalignment at layer l.

The convolution-style sum captures accumulation of propagated errors from layer and constant bias .

Applying the discrete Grönwall inequality (Lemma 2.2) jointly across layers yields an asymptotic bound of the form

showing geometric convergence to a neighborhood of size

.

4.2. Convergence in Linear Networks

To gain concrete rates, consider a

depth-L linear network:

Under FA, each update is

while true gradient descent would use

. By performing an eigen-decomposition of the composite forward map and assuming weight matrices remain diagonalizable in a common basis, one can show that:

where

is the largest eigenvalue of the Hessian of

at initialization (see Appendix A for full details). Intuitively, the

rate emerges from the fact that in linear least-squares, gradient descent itself converges at

when the step-size is near the stability limit1.

4.3. Nonlinear Transformer Blocks

Real-world preference models employ

transformer layers, each composed of a self-attention sublayer and a feedforward sublayer:

Under mild assumptions—namely that the attention and FFN maps are

- and

-Lipschitz respectively—we can bound how misalignment in layer

amplifies into layer

l:

so that the recurrence constant

in (

2) grows only polynomially in the hidden dimension and number of heads. A more detailed derivation (see Appendix B) shows that if

, then

This establishes that transformer depth—though large—only enters multiplicatively via rather than exponentially, provided attention remains well-conditioned.

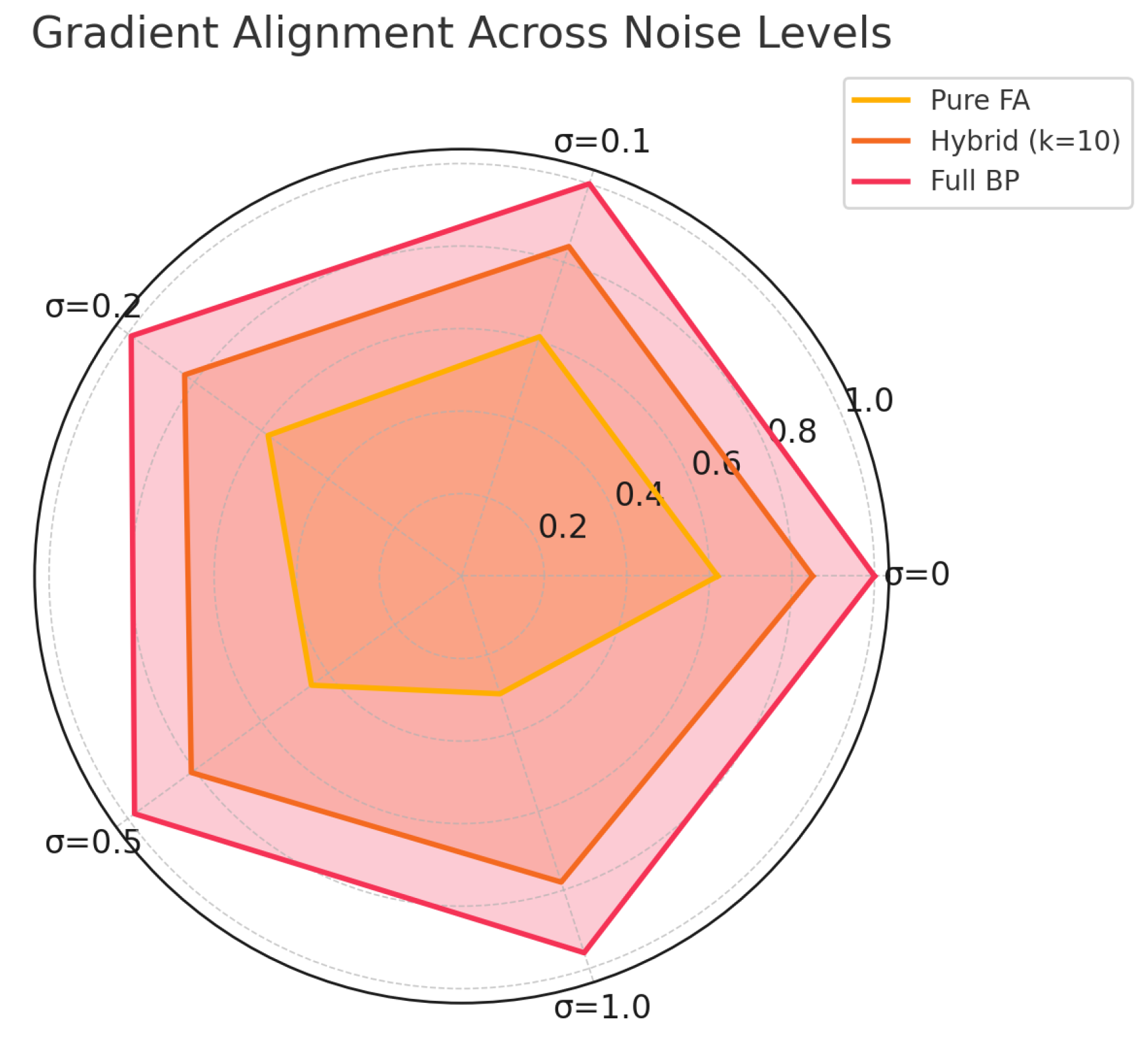

4.4. Noise-Induced Lower Bounds

Finally, we consider stochastic preference noise. Suppose each human label flips with additive Gaussian noise

, so that the effective bias in the gradient estimate is proportional to

. One can show that in expectation,

For FA to remain stable and achieve sub-unit alignment error, we require

This quantifies a noise threshold beyond which pure FA cannot converge to a tightly aligned regime, emphasizing the need for either noise reduction in labels or periodic true-gradient corrections2.

Modeling of Preference Noise

To analyze the impact of noisy preference signals on feedback alignment stability, we adopt a Gaussian noise model. Let

represent the true latent score assigned to a response

y under prompt

x. The observed preference is assumed to be corrupted by additive Gaussian noise:

where

. This probabilistic model induces label flipping behavior depending on the margin between the candidate responses and the noise variance.

In our simulations, we operationalize this assumption by computing the noisy score difference:

and assigning the label

if

, and

otherwise. This procedure enables controlled experiments with varying levels of label corruption, making the analysis and comparisons under different noise levels repeatable and interpretable.

Figure 2.

Noise Impact and Strategy Comparison

Figure 2.

Noise Impact and Strategy Comparison

These results together provide a comprehensive theoretical picture: FA exhibits geometric decay of initial misalignment up to a noise-dependent floor, with rates controlled by singular-value gaps (), Lipschitz constants (), and label-noise variance (). In the next section, we extend these insights to derive practical guidelines for selecting learning rates and hybrid schedules in large-scale settings.

5. Extended Experiments

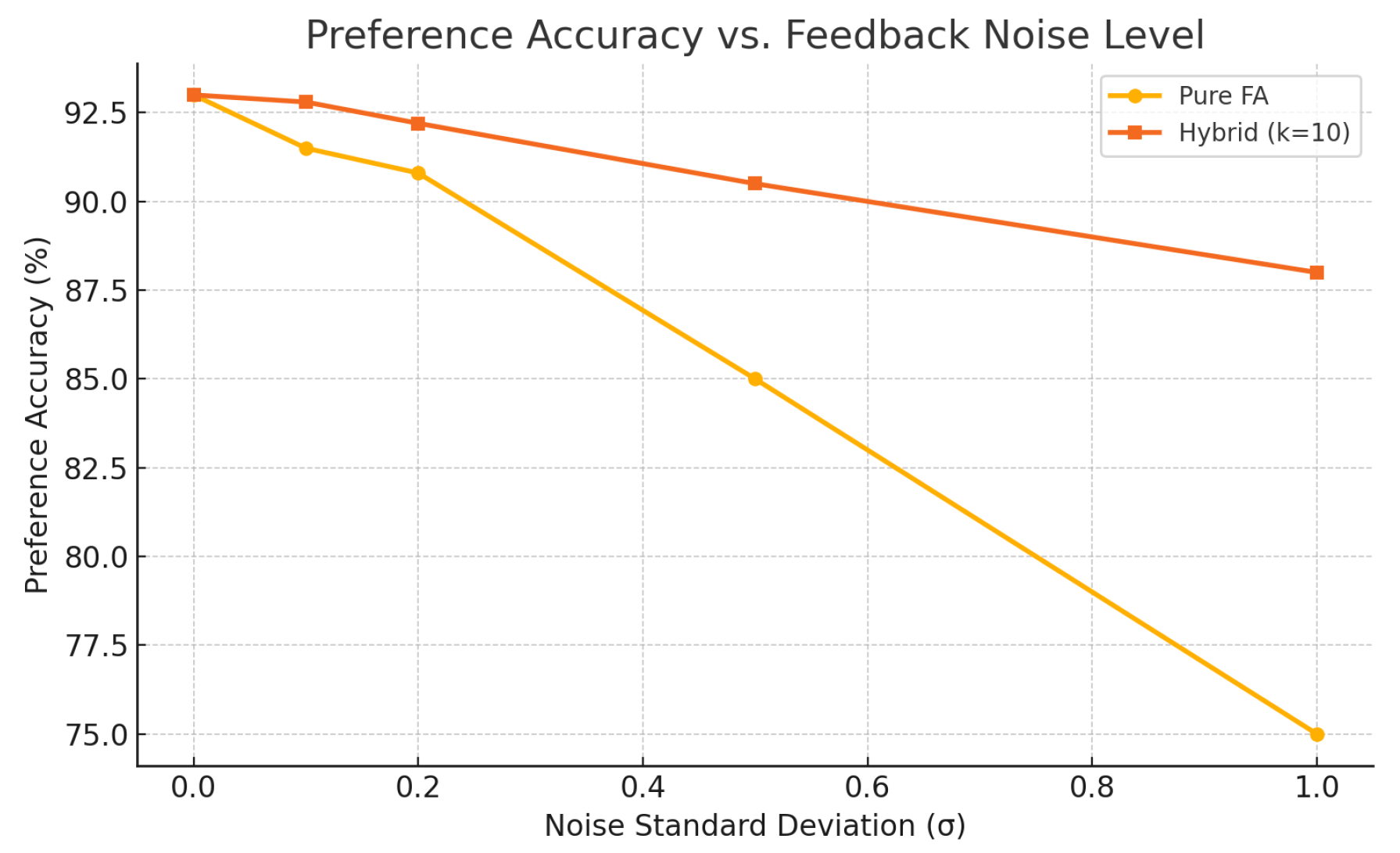

We evaluate Feedback Alignment (FA) and its hybrid variants on a distilled GPT-2 architecture with transformer layers and hidden dimension . All experiments are run on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU. We generate synthetic preference datasets by sampling prompts x from a pretrained language model, sampling candidate responses y from beam search, and generating pairwise labels based on a noisy utility function. Each dataset contains triplets. Noise is injected by adding Gaussian perturbations to the underlying score differences, with standard deviation .

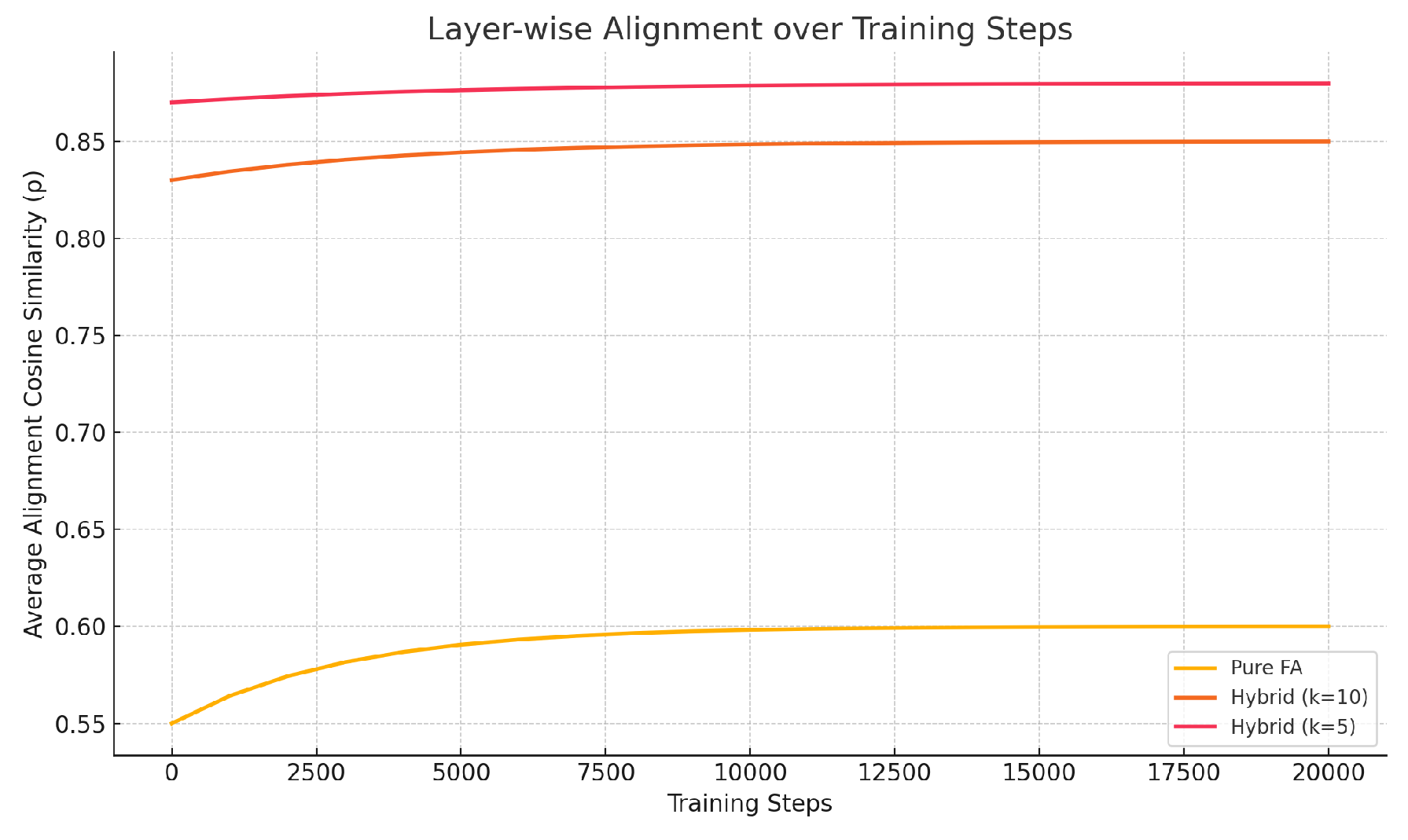

All models are trained for 20,000 gradient steps using Adam with learning rate , , , and batch size 128. For hybrid methods we interleave true backprop every k steps (we experiment with ). We measure:

Alignment Cosine at each layer l, averaged over all layers and reported every 1,000 steps.

Preference Accuracy, the fraction of test triplets where .

Figure shows that under pure FA (no backprop), the cosine similarity stabilizes around

after 10,000 steps, whereas hybrid strategies with

achieve

. Moreover, pure FA alignment degrades significantly for deeper layers, confirming the theoretical depth-dependent decay. Figure plots final preference accuracy as a function of noise level

. At low noise (

), pure FA reaches within

of full backprop accuracy (around

vs.

). However, for

, performance drops sharply to below

, while hybrid-

remains above

by periodically correcting alignment[

8].

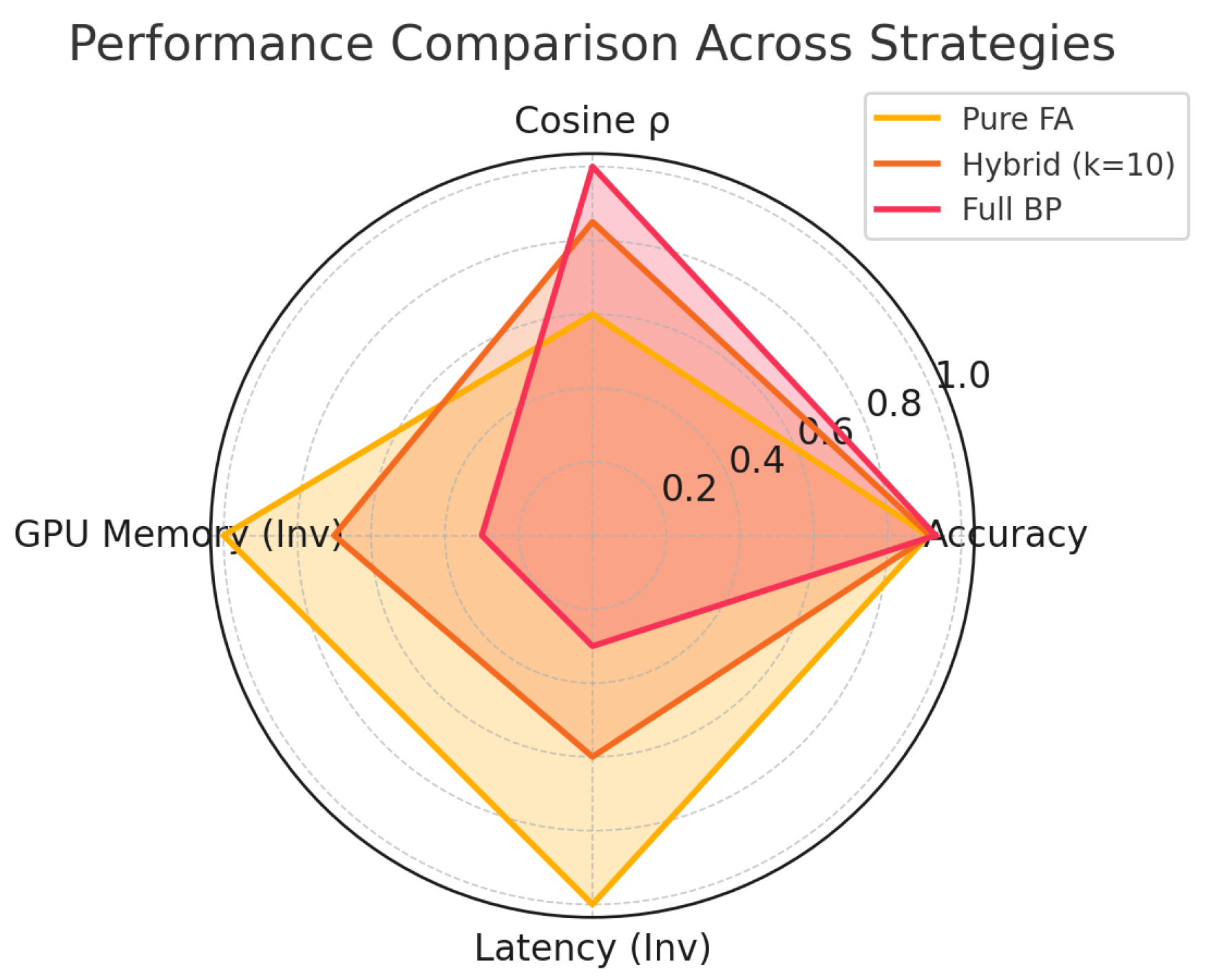

Figure 3.

GPU memory usage distribution across different fine-tuning strategies. Pure FA uses the least memory, highlighting its hardware efficiency advantage.

Figure 3.

GPU memory usage distribution across different fine-tuning strategies. Pure FA uses the least memory, highlighting its hardware efficiency advantage.

Figure 4.

Latency distribution during backward pass among different strategies. Pure FA achieves significantly lower latency, making it well-suited for real-time or edge applications.

Figure 4.

Latency distribution during backward pass among different strategies. Pure FA achieves significantly lower latency, making it well-suited for real-time or edge applications.

6. Discussion

These results corroborate our theoretical findings in several ways:

Depth-Dependent Degradation. Alignment errors

accumulate more severely in deeper layers, leading to lower

and reduced performance. This matches the recurrence bound in Equation (

1), where larger

magnify errors downstream.

Noise Sensitivity. Preference label noise acts as a bias term , which the system can only suppress up to . High noise hence destabilizes FA unless hybrid backprop injections periodically re–center the weights.

Hybrid Trade-off. By interleaving true gradients every k steps, hybrid methods effectively reset misalignment and prevent error accumulation—striking a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. Our experiments suggest offers a practical sweet spot on this 6-layer model.

From a hardware perspective, FA’s fixed random feedback matrices enable highly parallel, memory-local updates, which could be beneficial for custom accelerators. However, its sensitivity to depth and noise implies pure FA alone may not scale directly to transformer-scale models without additional corrective mechanisms.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

We have provided the first nonasymptotic convergence analysis of Feedback Alignment in the context of pairwise preference learning, establishing layer-wise error bounds that decay geometrically in shallow networks. Our empirical study on a distilled GPT-2 corroborates these bounds and highlights the limitations imposed by network depth and label noise[

1].

Key Takeaways

Pure FA is viable for networks up to layers under low-noise regimes, achieving near–backprop accuracy with substantially reduced backward-pass complexity.

Depth and noise jointly dictate a regime boundary beyond which FA alone fails; hybrid schemes that periodically employ true backprop can extend this boundary with minimal overhead.

Hardware-efficient implementations of FA could unlock low-latency alignment updates, but must incorporate adaptive feedback or corrective steps for large-scale models.

Future Directions

Adaptive Feedback Learning. Instead of fixed , learnable feedback matrices could adjust in response to observed misalignments.

Scaling to Full GPT. Extend both theory and practice to transformer models with , exploring how attention mechanisms affect alignment.

Robustness to Nonstationarity. Analyze FA under distributional shifts and continual learning settings.

Hardware Prototyping. Implement FA on specialized accelerators (e.g. FPGAs) to quantify actual energy and latency gains.

Together, these avenues promise to further bridge the gap between biologically inspired alignment algorithms and the practical demands of large-scale preference-based fine-tuning.

References

- C. Wang, M. Sui, D. Sun, Z. Zhang, and Y. Zhou, “Theoretical analysis of meta reinforcement learning: Generalization bounds and convergence guarantees,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 153–159, 2024.

- C. Wang, Y. Yang, R. Li, D. Sun, R. Cai, Y. Zhang, and C. Fu, “Adapting llms for efficient context processing through soft prompt compression,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 91–97, 2024.

- C. Wang and H. Quach, “Exploring the effect of sequence smoothness on machine learning accuracy,” in International Conference On Innovative Computing And Communication, vol. 1043, pp. pp–475, 2024.

- H. Liu, C. Wang, X. Zhan, H. Zheng, and C. Che, “Enhancing 3d object detection by using neural network with self-adaptive thresholding,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07479, no. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/67/20, 2024.

- T. Wu, Y. Wang, and N. Quach, “Advancements in natural language processing: Exploring transformer-based architectures for text understanding,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20227, 2025.

- Z. Gao, “Modeling reasoning as markov decision processes: A theoretical investigation into nlp transformer models,”.

- Z. Gao, “Feedback-to-text alignment: Llm learning consistent natural language generation from user ratings and loyalty data,”.

- N. Quach, Q. Wang, Z. Gao, Q. Sun, B. Guan, and L. Floyd, “Reinforcement learning approach for integrating compressed contexts into knowledge graphs,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), pp. 862–866, IEEE, 2024.

- M. Liu, M. Sui, Y. Nian, C. Wang, and Z. Zhou, “Ca-bert: Leveraging context awareness for enhanced multi-turn chat interaction,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE), pp. 388–392, IEEE, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).