Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

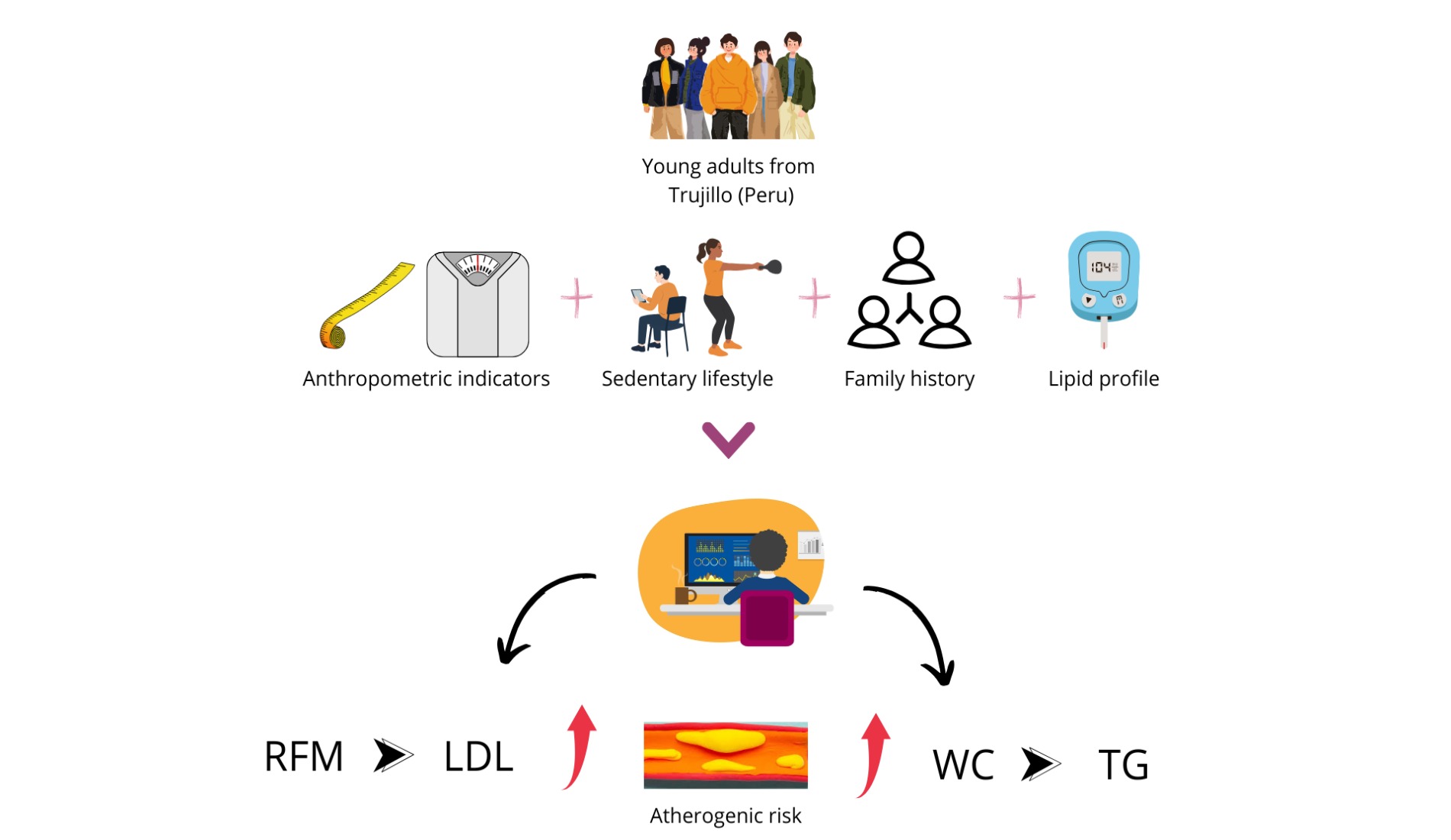

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Research

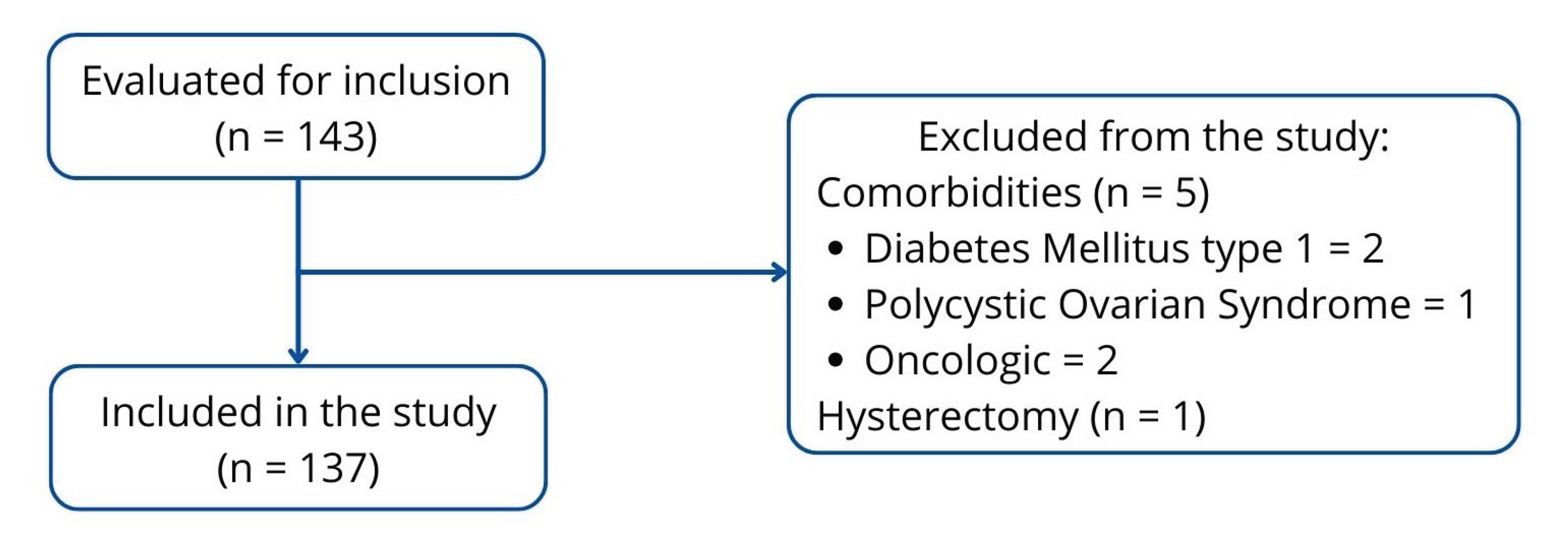

2.2. Population, Sample and Sampling

2.3. Assessment of Adiposity Indicators

2.3.1. Body Mass Index (BMI)

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Relationship Between Adiposity, Sedentary Lifestyle, and Family History with Cholesterol Changes

3.3. Relationship Between Adiposity, Sedentary Lifestyle and Family History with Changes in LDL-c Levels

3.4. Relationship Between Adiposity, Sedentary Lifestyle and Family History with Changes in HDL-c Levels

3.5. Relationship of Adiposity, Sedentary Lifestyle, and Family History with Variations in Triglyceride Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCA1 | ATP Binding Cassette A1 |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BRI | Body roundness index |

| CI | Conicity index |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DXA | X-ray absorptiometry |

| HDL-c | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-c | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MET | metabolic equivalent of task |

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| RFM | Relative fat mass |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| WHtR | Waist-to-height ratio |

References

- Jerez, C.; Irribarren, J.; Diaz, F.; Kusanovic, J.; Araya, B. Mecanismos fisiopatológicos de la dislipidemia. NOVA 2023, 21, 11–29. Available online: https://hemeroteca.unad.edu.co/index.php/nova/article/view/6882/6081 (accessed on 6 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Carrero, C.; Navarro, E.; Lastre, G.; Oróstegui, M.; González, G.; Sucerquia, A.; Sierra, L. Dislipidemia como factor de riesgo cardiovascular: uso de probióticos en la terapéutica nutricional. AVFT 2020, 39, 127–139. Available online: https://www.revistaavft.com/images/revistas/2020/avft_1_2020/22_dislipidemia.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Ministerio de Salud (MINSA). Vigilancia de la situación del sobrepeso, obesidad y sus determinantes en el marco del observatorio de nutrición y estudio del sobrepeso y obesidad . In Informe Técnico 2023; Instituto Nacional de Salud/Centro Nacional de Alimentación, Nutrición y Vida Saludable: Lima, Peru, 2013; pp. 211–13. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto, M.L.; Abdo-Francis, M.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Balcázar-Hernández, L.; Borrayo-Sánchez, G.; Castro-Narro, G.E.; Chávez-Negrete, A.; Díaz-Aragón, A.; Enciso-Muñoz, J.M.; Fernández-Barros, C.; et al. Dislipidemia: recomendaciones para el diagnóstico y tratamiento en el primer nivel de contacto médico. Gac. Med. Mex. 2024, 160, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.E. Asociación entre indicadores antropométricos y dislipidemia en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes de la ciudad de Caracas. ALAN 2021, 71, 85–93. Available online: https://www.alanrevista.org/ediciones/2021/2/art-1/ (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Dong, J.; Ni, Y.Q.; Chu, X.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, G.X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.B.; Yan, Y.X. Association between the abdominal obesity anthropometric indicators and metabolic disorders in a Chinese population. Public Health 2016, 131, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M.; Ameer, F.; Munir, R.; Rashid, R.; Farooq, N.; Hasnain, S.; Zaidi, N. Anthropometric and metabolic indices in assessment of type and severity of dyslipidemia. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2017, 36, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobo, O.; Leiba, R.; Avizohar, O.; Karban, A. Relative fat mass is a better predictor of dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome than body mass index. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 8, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutkienė, S.; Petrulionienė, Ž.; Laucevičius, A.; Petrylaitė, M.; Maskeliūnaitė, D.; Puronaitė, R.; Kovaitė, M.; Kalibaitaitė, I.; Rinkūnienė, E.; Dženkevičiūtė, V.; et al. Severe dyslipidemia and concomitant risk factors in the middle-aged Lithuanian adults: a cross-sectional cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H.; Oh, Y.H. Sedentary lifestyle: overview of updated evidence of potential health risks. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2020, 41, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, J.; Neglia, C.; Díaz, J.; Yupari, I. Modelos predictivos del riesgo aterogénico en ciudadanos de Trujillo (Perú) basados en factores asociados. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4138. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/23/4138 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Rod, N.H.; Davies, M.; de Vries, T.R.; Kreshpaj, B.; Drews, H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Elsenburg, L.K. Young adulthood: a transitional period with lifelong implications for health and wellbeing. BMC Glob. Public Health 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, S. Psicología del Desarrollo Humano II, 2nd ed.; Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa: Sinaloa, México, 2018; pp. 19–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, G.; et al. Association of anthropometric and obesity indices with abnormal blood lipid levels in young and middle-aged adults. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Reyes, A.; Vidal, Á.; Moreno-Ortega, A.; Cámara-Martos, F.; Moreno-Rojas, R. Waist Circumference as a Preventive Tool of Atherogenic Dyslipidemia and Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Risk in Young Adults Males: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud (MINSA). Guía Técnica para la valoración nutricional antropométrica de la persona adulta . Ministerio de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud; Lima, Peru, 2013; pp. 13–16. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/382688/Gu%C3%ADa_t%C3%A9cnica_para_la_valoraci%C3%B3n_nutricional_antropom%C3%A9trica_de_la_persona_adulta20191011-25586-13mvsvf.pdf?v=1605196582.

- Vinueza, A.; Tapia, E.; Tapia, G.; Nicolade, T.; Carpio, T. Estado nutricional de los adultos ecuatorianos y su distribución según sus características sociodemográficas. Estudio transversal. Nutr. Hosp. 2023, 40, 102–108. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112023000100014 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Woolcott, O.; Bergman, R. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage: a cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, p. 10980. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-29362-1 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Vallejo, S.; Sánchez, J.; Paz, W.; Guamán, W.; Montaluisa, F.; Correa, F.; Vásquez, M. Índice de redondez corporal como indicador antropométrico para identificar riesgo de síndrome metabólico en médicos del hospital San Francisco del IESS, en la ciudad de Quito. Rev. Fac. Cien. Med. (Quito) 2018, 43, 116–224. Available online: https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2022/03/1361297/doi-131.PDF (accessed on 22 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Raya, E.; Molina, G.; Romero, M.; Álvarez, C.; Hernández, A.; Molina, R. Comparación de índices antropométricos, clásicos y nuevos, para el cribado de síndrome metabólico en población adulta laboral. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2020, 94, 1–13. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11582906/pdf/1135-5727-resp-94-e202006042.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Carrera, Y. Cuestionario Internacional de actividad física (IPAQ). Rev. Enfermería Trab. 2017, 7, 49–54. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5920688 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Asociación Médica Mundial. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM—Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. Adoptada por la 18ª Asamblea Médica Mundial, Helsinki, Finlandia, junio 1964. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Liu, L.Y.; Aimaiti, X.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Zhi, X.Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Yin, X.; et al. Epidemic trends of dyslipidemia in young adults: a real-world study including more than 20,000 samples. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M. Impacto del ejercicio físico en la dislipidemia diabética. Rev. Soc. Argent. Diabetes 2019, 52, 86–93. Available online: https://revistasad.com/index.php/diabetes/article/view/122/106 (accessed on 29 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Imierska, M.; Kurianiuk, A.; Błachnio-Zabielska, A. The influence of physical activity on the bioactive lipids metabolism in obesity-induced muscle insulin resistance. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, R.; Monda, V.; Nigro, E.; Messina, A.; Di Maio, G.; Giuliano, M.T.; Orrù, S.; Imperlini, E.; Calcagno, G.; Mosca, L. The important role of adiponectin and orexin-A, two key proteins improving healthy status: focus on physical activity. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirabdollahian, F.; Haghighatdoost, F. Anthropometric indicators of adiposity related to body weight and body shape as cardiometabolic risk predictors in British young adults: superiority of waist-to-height ratio. J. Obes. 2018, 2018, 8370304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederos-Torres, C.V.; Díaz-Burke, Y.; Muñoz-Almaguer, M.L.; García-Zapién, A.G.; Uvalle-Navarro, R.L.; González-Sandoval, C.E. Triglyceride/high-density cholesterol ratio as a predictor of cardiometabolic risk in young population. J. Med. Life 2024, 17, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkwana, M.R.; Monyeki, K.D.; Lebelo, S.L. Body roundness index, a body shape index, conicity index, and their association with nutritional status and cardiovascular risk factors in South African rural young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, R.; Nyrienda, M.; Rodgers, L.; Asiki, G.; Banda, L.; Shields, B.; Hattersley, A.; Crampin, A.; Newton, R.; Jones, A. Associations between low HDL, sex and cardiovascular risk markers are substantially different in sub-Saharan Africa and the UK: analysis of four population studies. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, O.; Shahraki, M.; Shahraki, T. Obesity indices in relation to lipid abnormalities among medical university students in Zahedan, South-East of Iran. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samamalee, K.; Champa, J.; Rasika, P. Screening of serum cholesterol level amongst Sri Lankan women in relation to waist-height ratio (WHtR), waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), waist-hip ratio (WHR), and waist-thigh ratio (WTR): a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Adv. Multidisc. Res. Stud. 2024, 4, 304–308. Available online: https://www.multiresearchjournal.com/admin/uploads/archives/archive-1726844928.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Rai, T.; Rai, B.; Pakkala, P.; Mathur, N.; Sujith, N.; Orru, G. A formal analysis of anthropometric parameters for effective forecasting of dyslipidemia in healthy young adults. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 308–319. Available online: https://journaljpri.com/index.php/JPRI/article/view/3435 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, D.; Bas, M.; Cakir, N.; Hajhamidiasl, L. Predicción del síndrome metabólico mediante el índice de adiposidad visceral, el índice de redondez corporal, el índice de adiposidad disfuncional, el índice de producto de acumulación lipídica y el índice de forma corporal en adultos. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112022000600012 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Lebech, S.; Rasmussen, N.; Vestergaard, P.; Hejlesen, O. Is predicted body-composition and relative fat mass an alternative to body-mass index and waist circumference for disease risk estimation? Clin. Nutr. 2022, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, H.; Kirkpatrick, C.; Maki, K.; Toth, P.; Morgan, R.; Tondt, J.; Christensen, S.M.; Dixon, D.; Jacobson, T.A. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association. Obes. Pillars 2024, 10, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zderic, T.W.; Hamilton, M.T. Physical inactivity amplifies the sensitivity of skeletal muscle to the lipid-induced downregulation of lipoprotein lipase activity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Tepylo, K.; Eny, K.; Cahill, L.; Sohemy, A. Comparación del índice de masa corporal y la circunferencia de la cintura como predictores de la salud cardiometabólica en una población de adultos jóvenes canadienses. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2010, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, M.; Bustos, P.; Amigo, H.; Silva, C.; Rona, R. Is waist circumference a better predictor of blood pressure, insulin resistance and blood lipids than body mass index in young Chilean adults? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, E.; Homs, J.; Boadas-Vaello, P. Physiological changes and pathological pain associated with sedentary lifestyle-induced body systems fat accumulation and their modulation by physical exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khawaja, T.; Nied, M.; Wilgor, A.; Neeland, I.J. Impact of visceral and hepatic fat on cardiometabolic health. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagaró, N.M.; Zamora, L. Análisis estadístico implicativo versus regresión logística binaria para el estudio de la causalidad en salud. Multimed. 2019, 23, pp. 1416–1440. Available online: https://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1028-48182019000601416 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

| Baseline characteristics | Men (n = 41) |

Women (n = 96) |

Mann Whitney U-test Significance (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.39 ± 7.49 | 32.23 ± 6.90 | 0.088 |

| Adiposity indicators | |||

| Waist circumference (m) | 0.94 ± 0.12 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | 0.001 |

| Relative fat mass (%) | 27.31 ± 4.43 | 39.33 ± 4.72 | < 0.001 |

| Conicity index | 1.28 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| Body roundness index | 4.48 ± 1.37 | 4.55 ± 1.67 | 0.767 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.01 ± 4.47 | 27.90 ± 5.23 | 0.637 |

| Lipid profile | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 166.44 ± 45.75 | 172.95 ± 39.40 | 0.215 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.39 ± 36.36 | 102.74 ± 33.60 | 0.803 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 38.90 ± 16.45 | 47.42 ± 15.82 | 0.005 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 122.41 ± 59.64 | 122.61 ± 69.40 | 0.659 |

| Physical activity | |||

| METs | 1205.36 ± 1138.25 | 845.35 ± 986.19 | 0.048 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | |||

| Sitting time (h) | 5.37 ± 2.82 | 5.45 ± 2.75 | 0.951 |

| Sedentary lifestyle (%) | 43.9 | 57.3 | 0.150 |

| Bivariate Analysis for Total Cholesterol | |||

| Indicator | Cholesterol < 200 mg/dL f (%) | Cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL f (%) | Significance (p) |

| Gender | 0.612 | ||

| Female | 71 (68.9) | 25 (73.5) | |

| Male | 32 (31.1) | 9 (26.5) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||

| BMI Thin | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.763 |

| BMI Normal | 32 (31.1) | 8 (23.5) | 0.402 |

| BMI Overweight | 45 (43.7) | 16 (47.1) | 0.732 |

| BMI Obesity | 25 (24.3) | 10 (29.4) | 0.551 |

| Waist circumference | 0.092 | ||

| No risk | 44 (42.7) | 9 (26.5) | |

| At risk | 59 (57.3) | 25 (73.5) | |

| Relative fat mass | 0.183 | ||

| Normal | 15 (14.6) | 2 (5.9) | |

| Obesity | 88 (85.4) | 32 (94.1) | |

| Body roundness index | 0.088 | ||

| No risk | 34 (33.0) | 6 (17.6) | |

| At risk | 69 (67.0) | 28 (82.4) | |

| Conicity index | 0.389 | ||

| No risk | 45 (43.7) | 12 (35.3) | |

| At risk | 58 (56.3) | 22 (64.7) | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 0.726 | ||

| No | 49 (47.6) | 15 (44.1) | |

| Yes | 54 (52.4) | 19 (55.9) | |

| Family History | 0.067 | ||

| No family history | 15 (14.6) | 1 (2.9) | |

| With family history | 88 (85.4) | 33 (97.1) | |

| Bivariate analysis for LDL-c | Binary Logistic Regression Model* | |||

| Indicator | LDL-c < 100 mg/dL f (%) | LDL-c ≥ 100 mg/dL f (%) | Significance | Significance (p), odds ratio (OR), and confidence interval (CI) at 95% |

| Gender | 0.113 | |||

| Female | 42 (63.6) | 54 (76.1) | ||

| Male | 24 (36.4) | 17 (23.9) | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||

| BMI Thin | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.215 | |

| BMI Normal | 24 (36.4) | 16 (22.5) | 0.075 | |

| BMI Overweight | 26 (39.4) | 35 (49.3) | 0.244 | |

| BMI Obesity | 15 (22.7) | 20 (28.2) | 0.466 | |

| Waist circumference | 0.023 | |||

| No risk | 32 (48.5) | 21 (29.6) | ||

| At risk | 34 (51.5) | 50 (70.4) | ||

| Relative fat mass | 0.013 | p: 0.019 (OR = 4.108; IC 95%: 1.266 – 13.332) | ||

| Normal | 13 (19.7) | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Obesity | 53 (80.3) | 67 (94.4) | ||

| Body roundness index | 0.031 | |||

| No risk | 25 (37.9) | 15 (21.1) | ||

| At risk | 41 (62.1) | 56 (78.9) | ||

| Conicity index | 0.378 | |||

| No risk | 30 (45.5) | 27 (38.0) | ||

| At risk | 36 (54.5) | 44 (62.0) | ||

| Sedentary lifestyle | 0.278 | |||

| No | 34 (51.5) | 30 (42.3) | ||

| Yes | 32 (48.5) | 41 (57.7) | ||

| Family History | 0.222 | |||

| No family history | 10 (15.2) | 6 (8.5) | ||

| With family history | 56 (84.8) | 65 (91.5) | ||

| Bivariate analysis for HDL-c | |||

| Indicator | Normal HDL-c f (%) | Low HDL-c f (%) | Significance |

| Gender | 0.958 | ||

| Female | 37 (69.8) | 59 (70.2) | |

| Male | 16 (30.2) | 25 (29.8) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||

| BMI Thin | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.181 |

| BMI Normal | 18 (34.0) | 22 (26.2) | 0.330 |

| BMI Overweight | 25 (47.2) | 36 (42.9) | 0.621 |

| BMI Obesity | 9 (17.0) | 26 (31.0) | 0.068 |

| Waist circumference | 0.105 | ||

| No risk | 25 (47.2) | 28 (33.3) | |

| At risk | 28 (52.8) | 56 (66.7) | |

| Relative fat mass | 0.197 | ||

| Normal | 9 (17.0) | 8 (9.5) | |

| Obesity | 44 (83.0) | 76 (90.5) | |

| Body roundness index | 0.174 | ||

| No risk | 19 (35.8) | 21 (25.0) | |

| At risk | 34 (64.2) | 63 (75.0) | |

| Conicity index | 0.985 | ||

| No risk | 22 (41.5) | 35 (41.7) | |

| At risk | 31 (58.5) | 49 (58.3) | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 0.790 | ||

| No | 24 (45.3) | 40 (47.6) | |

| Yes | 29 (54.7) | 44 (52.4) | |

| Family History | 0.232 | ||

| No family history | 4 (7.5) | 12 (14.3) | |

| With family history | 49 (92.5) | 72 (85.7) | |

| Bivariate analysis for [Triglycerides] | Binary Logistic Regression Model* | |||

| Indicator | TG < 150 mg/dL f (%) |

TG ≥ 150 mg/dL f (%) |

Significance | Significance (p), odds ratio (OR), and confidence interval (CI) at 95% |

| Gender | 0.799 | |||

| Female | 73 (69.5) | 23 (71.9) | ||

| Male | 32 (30.5) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||

| BMI Thin | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.019 | |

| BMI Normal | 37 (35.2) | 3 (9.4) | 0.005 | |

| BMI Overweight | 45 (42.9) | 16 (50.0) | 0.477 | |

| BMI Obesity | 22 (21.0) | 13 (40.6) | 0.025 | |

| Waist circumference | 0.001 | p: 0.001 (OR = 6.125; IC 95%: 2.007 – 18.690) | ||

| No risk | 49 (46.7) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| At risk | 56 (53.3) | 28 (87.5) | ||

| Relative fat mass | 0.069 | |||

| Normal | 16 (15.2) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Obesity | 89 (84.8) | 31 (96.9) | ||

| Body roundness index | 0.005 | |||

| No risk | 37 (35.2) | 3 (9.4) | ||

| At risk | 68 (64.8) | 29 (90.6) | ||

| Conicity index | 0.175 | |||

| No risk | 47 (44.8) | 10 (31.3) | ||

| At risk | 58 (55.2) | 22 (68.8) | ||

| Sedentary lifestyle | 0.045 | |||

| No | 54 (51.4) | 10 (31.3) | ||

| Yes | 51 (48.6) | 22 (68.8) | ||

| Family History | 0.643 | |||

| No family history | 13 (12.4) | 3 (9.4) | ||

| With family history | 92 (87.6) | 29 (90.6) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).