1. Introduction

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) that causes Mpox, a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus, is an enveloped double stranded DNA virus endemic in multiple African countries [

1]. In 2022, it attracted global attention due to widespread outbreak in non-endemic regions. Mpox typically presents itself as a febrile disease associated with skin and/or mucosal rash, with a broad spectrum of clinical severity [

2].

The genomic linear DNA is approximately 197 kilobase (kb) characterized by central conserved region flanked by roughly 6.4 kb inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). The core proteins are involved in transcription, replication and assembly while the ITRs are thought to be involved in pathogenesis and host range[

3]. MPXV is genetically classified into clade I and clade II. Clade I formerly known as the Congo Basin clade, associated with severe clinical symptoms and substantial mortality (4-11%), is endemic to central Africa, notably the Democratic Republic of Congo. Clade II, previously known as the West African clade, associated with mild clinical presentations and lower mortality (4%), was geographically confined until the global circulation of 2022 [

4].

The emergence of the clade II B.1 lineage in 2022 expanded global circulation, with multiple countries reporting Mpox case for the first time, warranting the declaration of Mpox a public health emergency of continental security and international concern by the Africa CDC and WHO, respectively [

5,

6].

Since 2022, 172,510 laboratory-confirmed cases have been detected in 141 countries, with 141 associated deaths. Regionally, in 2025, multiple west African countries have registered a surge in case. Sierra Leone reported 5,442 by October 26 despite none in 2024. Guinea, a neighbouring country to Mali, went from 2 cases in 2024 to 1,169 cases by November 9, 2025. Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire, both of which neighbour Mali, also reported cases, with Senegal confirming circulation of both clade Ib and clade IIb [

7]. In Mali, all suspected cases tested negative (by real-time PCR) until November 14, 2025, when the index case was confirmed. Genomic characterization and rapid data sharing are crucial in tracking viral evolution, transmission dynamics and informing public health decisions. We describe the clinical, molecular, and phylogeographic features of the index Mpox case in Mali.

2. Case Description

2.1. Location

Kourémalé, situated 125 km from Bamako, is a border community with Guinea where socioeconomic activities are dominated by artisanal gold mining.

2.2. Clinical Presentation

On November 14, 2025, a 35-year-old male from Burkina Faso working in artisanal gold mining and frequently traveling between Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea presented to a district health center in Kourémalé, at the Mali–Guinea border, with fever and a vesiculopustular rash that began on October 31, 2025. Lesions were mainly located on the face and genital region. Initially diagnosed with dermatosis and treated with topical antiseptics, he was later evaluated through the national telemedicine program because of persistent fever. A clinical diagnosis of Mpox was made, and acyclovir with supportive care was initiated, resulting in favorable clinical improvement before transfer to the infectious diseases department of CHU du Point G.

2.3. Epidemiological investigation

Investigators identified 5 direct contacts (including the nurse and a neighbour) and 43 indirect contacts. A swab was collected from the nurse. Contact tracing is underway to identify and isolate all contacts and risk communication and community engagement strategies are being implemented to help communities understand the Mpox risks, adopt preventive measures, and support the overall outbreak response.

2.4. Molecular Diagnosis, Genomic Characterization and Transmission Dynamic

All laboratory’ activities were performed in biosafety level 2 while strictly adhering to biosafety and biosecurity measures. Blood and swab samples collected on November 14 were subjected to DNA extraction using Qiagen DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Mpox detection performed by real-time PCR with LightMix® Modular Monkeypox on LightCycler 480 II (Roche, Berlin, Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions. The library was prepared with NextGenPCR™ MPXV Sequencing Library Prep (NextGenPCR, The Netherlands) as previously described [

8]

. The library containing the index specimen in duplicate and a negative control was barcoded with the Rapid Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (Oxford Nanopore Technology, Oxford, UK), loaded onto a MinION MK1C running Miniknow v25.05.12, and sequenced for approximately 5 hours. High-accuracy basecalling was performed with Dorado v7.9.8.

After sequencing, adapters were removed with porechop v0.2.4 and reads were quality-filtered with fastp v1.0.1. The resulting reads were aligned to MPXV reference genome (NC_063383.1) with minimap2 2.30-r1287, and consensus sequences were generated with samtools v1.22. Clade and lineage assignments were obtained using Nextclade v3.18.0 [

9,

10].

For transmission dynamic studies, all MPXV genomes collected between January 1 and November 22, 2025 on NCBI were downloaded and filtered for a genome length ≥195 kb and aligned with MAFFT. Phylodynamic analysis was performed using Augur toolkit v31.3.0 [

11]

. The build was visualized on Auspice v2.67 [

12].

3. Results

To decipher molecular epidemiology of the Mpox case, genomic sequencing was performed. A genome of length 197,122 bp was obtained with 99.8% coverage with an average depth of 1284.4x. The strain named Mpx-1-11-14-25-NPHI-ml belonged to clade IIb G.1 lineage, with 85 mutations relative to NC_063383.1.

The Mali genome (Mpx-1-11-14-25-NPHI-ml; BioProject PRJNA1367904) exhibited several distinguishing features relative to the closest contemporaneous Sierra Leone strains. These included five unique nucleotide substitutions (C75602A, C84548T, C134460T, C152336T, and C174267T), two homoplastic substitutions (G2591A and C194619T), and three non-synonymous substitutions affecting OPG002 (S54F), OPG096 (D6N), and OPG002_dup (S54F). C22L also known as J2L or OPG002 located in the inverted terminal repeat encodes Cytokine response-modifying protein B (CrmB) which act as soluble decoy receptor for tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [

13]. In addition, three short gaps totaling 4 bp were detected. The mutation spectrum was dominated by C→T and G→A transitions, consistent with host apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3) associated mutational signatures.

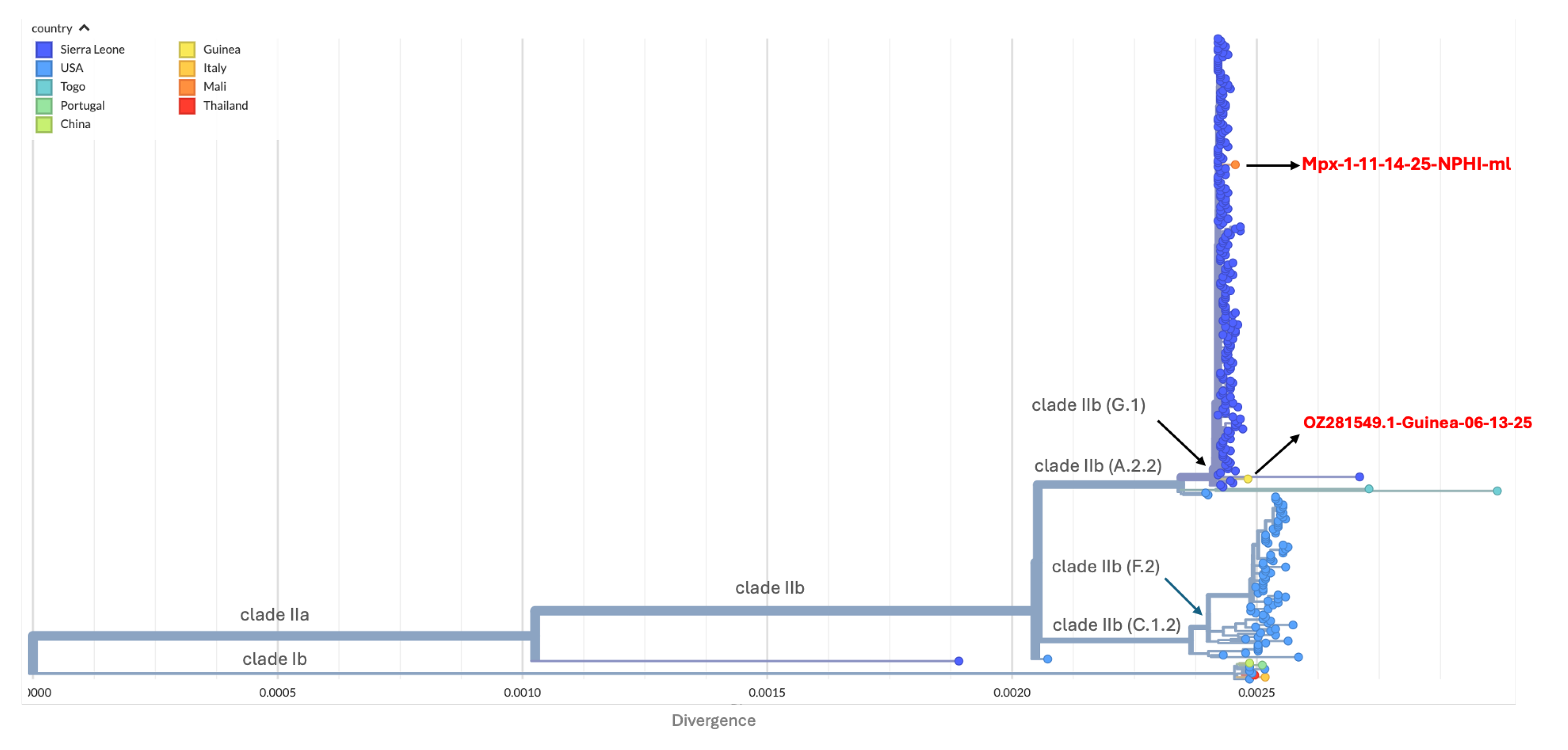

Phylogenetically, Mpx-1-11-14-25-NPHI-ml clustered within the clade IIb G.1 lineage and branched from the Sierra Leone clusters detected in May 2025, showing close genetic relatedness to the limited sequences available from Guinea (

Figure 1).

Both the Malian and Guinean strain closely related to strain responsible of outbreak in Sierra Leone in May 2025.

Spatiotemporal reconstruction (

Figure 2) suggests that the A.2.2 lineage may have been introduced into Sierra Leone from the USA, as previously reported [

11], before giving rise to the G.1 lineage that later circulated in both Guinea and Sierra Leone.

Deme diameter is proportional to the number of cases coloured by collection date

4. Discussion

The genomic characterization of the Mpx-1-11-14-25-NPHI-ml strain provides critical insight into the ongoing diversification of clade IIb, lineage G1 within western Africa. With a high depth assembly (1284.4x) and 99.8% coverage, this genome represents a robust reference for monitoring the molecular epidemiology of Mpox in Mali.

The mutation profile of the index strain, consisting of 85 mutations relative to the reference NC_063383.1 is characterized by a high frequency of C→T and G→A transitions consistent with host-mediated viral editing enzymes. The dominance of these transitions aligns with the evolutionary trajectory observed globally since 2022 multi-country outbreak, confirming that MPXV continues to undergo accelerated evolution driven by human host immune system rather than standard viral polymerase errors [

14].

While the strain is phylogenetically linked to comptemporaneous Sierra Leone strains, the presence of five unique mutations (C75602A, C84548T, C134460T, C152336T, and C174267T) and two homoplastic mutations (G2591A and C194619T) suggest independent evolutionary pressure. Interestingly, the strain detected in Guinea in June 2025, also linked to Sierra Leone. Given the epidemiological link with Guinea and the low sequencing coverage (2/1,169), we cannot fully rule out the possibility of importation from Guinea [

7]. The identification of non-synonymous substitutions in specific open reading frame warrants further investigation. In fact, S54F substitution in OPG002 and its duplicate OPG002_dup is of particular interest as it is situated in the ITR and act as TNF-decoy receptor to the host immune response [

13]. On the other hand, OPG096 is well conserved in the gene in the Orthopoxvirus genus. In the Vaccina virus, OPG096 is homologous to A12L. It is involved in the proteolytic processing of major core proteins. The D6N (aspartic acid to asparagine) mutation is in the N-terminus of the protein. While it is a conservative mutation (both are amino acid are polar), mutations in the core structural proteins such as OPG092 could potentially impact the efficiency of virion assembly.

5. Conclusions

Genomic data confirmed the first human Mpox case in Mali, highlighting the value of the telemedicine program in extending health coverage and improving surveillance sensitivity. Timely sharing of genomic data enabled reconstruction of spatiotemporal transmission patterns, revealing multi-country transmission fuelling the emergence of new lineages. The analysis confirms the presence of an evolving G.1 lineage in Mali, characterized by distinct features and a strong APOBEC3 mutational signature. The unique non-synonymous mutation in immune modulating (OPG002) and structural (OPG096) proteins highlight the necessity of ongoing functional studies to determine if these substitutions correlate with altered virulence and transmissibility. Integration of the national telemedicine into epidemiological surveillance, active cross-border surveillance, risk communication and genomic characterization are essential in controlling viral spread and burden. Sustaining genomic capacity remains essential for tracking viral evolution and informing timely public health interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. S1: Nexstrain build in json format : S1_Mali_Mpox-index-case.json. S2: accession number and associated metadata used for phylogenetic and transmission dynamic: S2_auspice_final_filtered_metadata.tsv

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Y.K., O.K. and M.A.; methodology, O.K., K.D., E.C., M.S.S.; validation, M.A., B.D., M.M.D. and I.G.; formal analysis, N.Y.K., M.M.D. and H.O.; investigation, M.A., M.A.B. and K.M.K; data curation, N.Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Y.K., M.A and M.A.B; writing—review and editing, H.O., DWW., M.M.D. and I.G; visualization, N.YK,; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research receives no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was done as part public health and genomic surveillance and as such the ethics committee approval was waived by the Institutional committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient informed consent was obtained.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence reads archive are available under the bioproject accession PRJNA1367904.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the ministry of health, FHI 360 and the Africa Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) through its Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative (Africa PGI), for supporting epidemiological and genomic surveillance activities allowing timely detection and characterization of the index case. We acknowledge all data providers for releasing MPXV sequences and metadata via the NCBI virus platform. The sequences and metadata used for phylogenetic analysis and transmission dynamic are listed in Supplementary file S2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

APOBEC3

CDC

CrmB

|

Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3

Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention

Cytokine response-modifying protein B

|

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FHI |

Family health interational |

| INSP |

Institut national de santé publique |

IPD

ITR |

Institut Pasteur de Dakar

Inverted terminal repeat |

| MAFFT |

Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform |

| MPXV |

Monkeypox virus |

| NCBI |

National center for biotechnology information |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

PGI

TNF |

Pathogen genomics initiative

Tumor necrosis factor |

| WHO |

World health organization |

References

- Van Dijck, C.; Hoff, N.A.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Low, N.; Cevik, M.; Rimoin, A.W.; Kindrachuk, J.; Liesenborghs, L. Emergence of Mpox in the Post-Smallpox Era—a Narrative Review on Mpox Epidemiology. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2023, 29, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzón, S.; Varona, S.; Negredo, A.; Vidal-Freire, S.; Patiño-Galindo, J.A.; Ferressini-Gerpe, N.; Zaballos, A.; Orviz, E.; Ayerdi, O.; Muñoz-Gómez, A.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Genomic Accordion Strategies. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakaniaki, E.H.; Kacita, C.; Kinganda-Lusamaki, E.; O’Toole, Á.; Wawina-Bokalanga, T.; Mukadi-Bamuleka, D.; Amuri-Aziza, A.; Malyamungu-Bubala, N.; Mweshi-Kumbana, F.; Mutimbwa-Mambo, L.; et al. Sustained Human Outbreak of a New MPXV Clade I Lineage in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2791–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AfricaCDC Africa CDC Declares Mpox A Public Health Emergency of Continental Security; Mobilizing Resources Across the Continent. Available online: https://africacdc.org/news-item/africa-cdc-declares-mpox-a-public-health-emergency-of-continental-security-mobilizing-resources-across-the-continent/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General Declares Mpox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern.

- World Health Organization Global Mpox Trends. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Matthijs, W.; M., J.; Anton, van den O. Monkeypox Virus Whole Genome Sequencing Using Combination of NextGenPCR and Oxford Nanopore V.1. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/monkeypox-virus-whole-genome-sequencing-using-comb-n2bvj6155lk5/v1 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddleston, J.; Hadfield, J.; Sibley, T.R.; Lee, J.; Fay, K.; Ilcisin, M.; Harkins, E.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A.; Hodcroft, E.B. Augur: A Bioinformatics Toolkit for Phylogenetic Analyses of Human Pathogens. Journal of open source software 2021, 6, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.K.O.; Sandi, J.D.; Omah, I.F.; Faye, M.; Parker, E.; Brock-Fisher, T.; Gigante, C.M.; Folorunso, V.; Kamara, M.S.; Williams, A.J.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology Uncovers the Origin of the Mpox Epidemic in Sierra Leone. medRxiv 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelman, J.; Johnston, S.; Mulembakani, P.; Kisalu, N.; Lee, M.; Koroleva, G.; McCarthy, S.; Gestole, M.; Wolfe, N.; Fair, J.; et al. Genomic Variability of Monkeypox Virus among Humans, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerging Infectious Disease journal 2014, 20, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Srivastava, U.; Gupta, S.; Rustagi, S.; Rudayni, H.A.; Kashyap, V.K.; Kumar, S. Mpox 2022 to 2025 Update: A Comprehensive Review on Its Complications, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Viruses 2025, 17, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).