1. Introduction

Programming paradigms refer to fundamental conceptual frameworks that shape how computational problems are formulated and solved, extending beyond specific programming languages or syntactic rules [

1,

2]. In educational contexts, paradigms are best understood as instructional lenses that emphasize particular modes of reasoning rather than as essential properties of individual languages. As software systems have grown in complexity, diverse paradigms—such as imperative, object-oriented [

3], functional, and logic-based approaches—have emerged to support different modes of reasoning and problem decomposition. Rather than serving solely as implementation techniques, paradigms influence how programmers conceptualize problems, structure solutions, and reason about computation.

Previous studies have attempted to compare programming paradigms from conceptual and technical perspectives [

4,

5]; however, many of these studies remain centered on language structures or formal characteristics, offering limited insight into how learners actually experience paradigm-oriented instruction in practice. Empirical investigations into how learners perceive and experience paradigm-oriented instruction—particularly from a learner-centered and instructional perspective—remain relatively limited [

5]. In particular, novice and non-major learners often encounter cognitive difficulties arising from abstract concepts and paradigm-oriented instructional demands; however, systematic empirical analyses focusing on this population remain scarce, especially outside computer science–major curricula [

6,

7]. Against this background, Ewha Womans University has offered a Principles of Programming Languages (PLT) course for over two decades, targeting non-major students. The course is structured around four major instructional modules, each framed with paradigm-specific features—imperative-style programming emphasized through C, object-oriented design emphasized through Java, logic-based reasoning emphasized through Prolog, and functional-style constructs emphasized through Python—and is designed to support learners with little or no prior programming experience. As part of a government-supported Software-Centered University initiative, the program integrates interdisciplinary curricula such as X+SW and X++SW, providing an educational environment suitable for investigating effective instructional approaches for non-major learners.

Within this context, the present study aims to analyze recurring learning difficulties and error patterns observed among non-major learners when engaging with different programming paradigms. To this end, the study integrates learner survey data with large-scale question–answer data from Stack Overflow (SO). Because SO users are not identified as non–computer science students, these data are treated as a text-based proxy indicating recurring novice-level difficulties in public help-seeking contexts rather than as direct evidence of non-major learner experience [

8,

9]. Based on this analysis, the study seeks to derive pedagogical implications for designing effective programming education for non-major learners, using Stack Overflow data to triangulate recurring patterns rather than to validate survey-based perceptions. Specifically, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1. What major difficulties do non-major learners encounter when engaging with instructional modules framed around imperative, object-oriented, logic-based, and functional programming features?

RQ2. What types of conceptual and syntactic patterns are frequently observed in Stack Overflow Q&A data related to instructional contexts emphasizing these paradigm-oriented features?

RQ3. What implications do these findings offer for the design of instructional strategies for programming education targeting non-major learners?

3. Literature Review

Programming language paradigms have had a significant influence on computer education, programming language design, and software applications, extending across diverse domains such as system architecture, embedded programming, and parallel computing [

2,

3]. Recent programming education studies have increasingly adopted empirical and learner-centered approaches to derive practical implications within educational contexts, including survey-based analyses and case-oriented investigations [

13,

14]. Such approaches have been shown to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application, contributing to the development of intelligent tutoring systems, adaptive instructional design, and personalized learning tools. In particular, this study aims to propose effective programming education strategies for non-major learners by focusing on paradigm-specific learning difficulties.

Previous studies have examined programming paradigms from theoretical and technical perspectives, exploring how different approaches influence problem-solving processes and development practices. These studies have interpreted programming languages not merely as syntactic systems, but as instructional and representational media through which particular conceptual frameworks and problem-solving strategies are emphasized, and have visually analyzed paradigm-related differences through examples such as ABAP and BOPF. However, such research has largely focused on specific development environments or technical contexts, and thus has been limited in addressing learners’ cognitive characteristics or educational experiences. In response, the present study extends prior work by examining perceptions and learning experiences related to paradigm-oriented instruction among non-major learners, a population that has received comparatively less attention in prior programming education research.

Case studies have been widely used as an effective pedagogical approach to enhance learner understanding through real-world problem contexts [

5,

6,

15]. Prior research has demonstrated that case-based learning improves learners’ critical thinking and problem-solving abilities [

6]. In particular, studies in programming education have shown that analyzing the cognitive and affective characteristics of novice learners and identifying error patterns can inform instructional design and targeted pedagogical interventions. Furthermore, some studies have employed multi-institutional case analyses to investigate how learners conceptualize programming concepts.

More recently, studies utilizing online question-and-answer platforms such as Stack Overflow have gained attention [

8,

9,

16,

17]. These studies analyze code examples, explanations, and comment interactions to suggest that learning-related sense-making processes may occur not merely through information transmission but through social interaction and collaborative meaning-making. Comment analysis, in particular, has revealed mechanisms such as error correction, conceptual clarification, and alternative solution exploration, illustrating how publicly observable interactional traces can reflect learning-related reasoning processes. Additionally, some studies have pointed out that answers may become outdated over time, emphasizing the need for learners to critically evaluate information in context [

16,

17,

18].

Analyses of Stack Overflow data further reveal that accumulated questions and answers do not always reflect the latest technological developments, and that outdated or context-specific information may mislead learners. These findings highlight the importance of understanding programming knowledge as evolving rather than static, particularly when interpreting learner questions and misconceptions captured in large-scale Q&A data.

In addition, topic modeling studies have shown that developer discussions span a wide range of themes, including web technologies, mobile applications, programming languages, and development tools, and that these interests shift over time. Such analyses demonstrate that large-scale Q&A data can provide contextual indicators of prevalent topics, concerns, and recurring difficulties, which may inform programming education research and curriculum design.

Furthermore, recent studies have extended beyond traditional case-based approaches by incorporating problem-centered and interaction-driven learning strategies into programming education [

19,

20,

21]. For instance, interactive Q&A-based instruction has been shown to be associated with improvements in conceptual understanding and problem-solving abilities in specific instructional contexts, while step-by-step programming tasks contribute to reducing errors and improving learning efficiency [

19]. Integrating perspectives from the humanities has also been shown to strengthen computational thinking and conceptual understanding, and the use of deliberately designed errors has been found to improve learners’ debugging skills and cognitive flexibility [

20]. More recently, outcome-based education (OBE) models have been proposed to support competency-oriented programming education, demonstrating positive effects on learners’ practical problem-solving abilities.

Consistent with prior programming education research, this study explicitly interprets paradigm-related learning challenges as emerging through language-mediated instructional contexts, rather than as intrinsic properties of individual programming languages. Accordingly, all analyses in this study should be interpreted as reflecting paradigm-oriented instructional exposure mediated by specific languages, rather than intrinsic properties of the languages themselves.

In summary, while existing studies have primarily focused on educational designs for computer science majors, systematic investigations targeting non-major learners remain limited. This study addresses this gap by examining the cognitive characteristics and error patterns of non-major learners in the context of programming paradigm education. By integrating Stack Overflow data with survey-based evidence, the present research seeks to triangulate learner-reported perceptions with publicly observable patterns of novice-level difficulties, thereby providing empirically grounded insights into learners’ perceptions and learning processes.

4. Case Dataset and Implementation

This study adopts a mixed-method research design that integrates learner survey data with large-scale Stack Overflow (SO) question-and-answer data [

10,

13,

18]. Survey responses capture learners’ self-reported experiences and perceived difficulties, while SO data provide complementary evidence of recurring errors and help-seeking behavior in real programming contexts. By triangulating these two sources, the study aims to contextualize learner-reported perceptions with publicly observable patterns of novice-level difficulties, while mitigating some limitations inherent in relying on a single data source.

Although the PLT course has been offered for over two decades, the empirical analysis in this study is restricted to survey data collected within a single academic year and Stack Overflow posts from 2020 onward.

Long-term teaching experience is used solely to inform contextual interpretation of the findings, rather than as a longitudinal dataset contributing to the quantitative analyses. Therefore, potential confounding variables such as evolving pedagogy, student demographics, or language popularity trends do not directly affect the quantitative analyses presented.

In particular, the survey data was used to identify learners’ perceptions, learning strategies, and perceived difficulties, while the SO data were employed to analyze real-world programming errors and problem-solving behaviors. By integrating these two data sources, this study provides a complementary perspective on non-major learners’ programming experiences and offers empirically grounded indications of their learning processes.

Unlike prior studies that primarily focused on computer science majors, this study specifically targets non-major learners, thereby distinguishing itself from existing research. Non-major learners often differ from computer science majors in terms of prior knowledge, problem-solving strategies, and learning motivations, which may influence the design and effectiveness of programming education. Accordingly, this study aims to identify the unique challenges and error patterns encountered by non-major learners and to provide pedagogical implications tailored to their learning needs.

A total of 49 survey items were designed to assess learners’ retrospectively reported experiences and perceived difficulties associated with different stages of the Programming Language Theory (PLT) course. The survey consisted of six main categories:(1) Demographic information and programming background (major, academic year, prior programming experience, and preferred programming languages);(2) Learning difficulties (self-reported perceived difficulties encountered during programming learning and paradigm-specific instructional challenges);(3) Learning effectiveness and satisfaction (perceived effectiveness of instruction, difficulty levels, and overall satisfaction);(4) Paradigm efficiency and applicability (educational effectiveness and applicability of each programming paradigm);(5) Problem-solving strategies (approaches used to resolve programming errors);(6) Future learning directions (recommended paradigms for beginners and preferred learning sequences).

This structured survey design enables a comprehensive analysis of the learning challenges and cognitive characteristics experienced by non-major learners and provides a solid empirical foundation for developing effective instructional strategies in programming education.

Although Stack Overflow users represent diverse backgrounds, prior research suggests that questions involving syntax errors, debugging, and fundamental constructs predominantly reflect novice-level learning challenges. In this study, Stack Overflow data are therefore treated as a text-based proxy for early-stage programming difficulties, rather than as direct representations of non-major learners [

7,

11].

4.1. Case Data Collection and Survey Design

This case study investigated paradigm-specific learning difficulties experienced by non-major novice learners by integrating insights from educational data mining and survey-based analysis. This study conducted a structured survey with 49 questions to analyze the experiences of non-major novice learners before and after taking a PLT course.

4.1.1. Survey Questionnaires

A structured survey was conducted with 64 non-major novice learners to capture their experiences with programming paradigms. Survey items were informed by recurring themes observed in SO questions and answers. Additional insights were drawn from communities such as Reddit (r/learnprogramming and r/programming), Quora, and programming forums (e.g., Python Forum, Java Programming Forums, C Programming, and SWI Prolog).

Survey items derived from online forums were systematically filtered through a two-stage process: (1) content mapping to predefined constructs (syntax understanding, conceptual understanding, debugging strategies), and (2) expert review by two instructors with over ten years of programming education experience.

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values ranging from

0.78 to 0.84 across constructs, indicating acceptable internal consistency for exploratory educational research [

22,

23,

24]. Construct validity was further supported through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with varimax rotation.

These resources informed the analysis of common learner difficulties, debugging errors, and syntax issues faced by non-major novice learners. Research studies, including further guided the design of survey items [

22,

23,

24]. The survey captured insights into learner experiences with programming paradigms, perceived difficulty levels, debugging skills, and the potential for future studies and applications.

Table 2 below shows some questionnaires.

4.1.2. Supplementary Data

To analyze the challenges faced by non-major learners, this study utilized SO, one of the most widely used programming Q&A platforms. Unlike structured classroom discussions, SO provides a publicly observable record of help-seeking and problem-reporting behaviors, enabling a data-driven exploration of frequently reported obstacles encountered in programming practice. The platform’s vast, community-driven dataset enables an evidence-based investigation of the most frequent obstacles encountered by learners, offering a complementary perspective to traditional educational assessments. Additionally, SO serves as an informal learning environment wherein students seek guidance beyond formal instruction and reflect on their self-directed problem-solving behaviors. By integrating these insights with survey responses, we aim to develop a comprehensive understanding of programming paradigm education for non-major learners, contributing to the refinement of curriculum design and instructional methodologies.

As of September 21, 2021, posts tagged with “C,” “Java,” “Prolog,” and “Python” were collected using Python’s BeautifulSoup library. To ensure a balanced representation of the different programming paradigms, 3,000 posts per paradigm were retrieved, totaling 12,000 posts. Web crawling techniques were used to automate the data extraction process by applying predefined filtering criteria to remove duplicates, irrelevant discussions, and incomplete entries. Only questions with accepted answers, a minimum of three upvotes, and from 2020 onwards were retained to maintain dataset quality and relevance to contemporary educational challenges. The preprocessing steps included removing noise, normalizing text using lemmatization and stop word removal, and employing Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) for topic modeling to categorize questions according to programming paradigms. This ensured that the dataset effectively captured non-major learners’ real-world programming difficulties. Supplementary materials can be downloaded at:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1h9wEq0jksN1OMAWPS9G7EqOL5UTclFmB?usp=sharing.

To capture semantic relationships among programming-related terms, a Word2Vec model was trained using the skip-gram architecture with a vector dimensionality of 100, a context window size of 5, and a minimum word frequency threshold of 1. Negative sampling with k = 5was applied, and the model was trained for 20 epochsto ensure stable convergence [

25]. For document-level semantic representation, a Doc2Vec (Distributed Memory) model was employed with an embedding size of 100, a window size of 5, and 20 training epochs.

Table 3 summarizes the total word count and average number of words per article for each programming language. Notably, Prolog’s concise syntax results in shorter question–answer texts, which may influence observed textual characteristics and should not be interpreted as intrinsic paradigm simplicity.

where M=3,000 for all languages included in the analysis.

To address the brevity of Prolog Q&A texts, subword-level tokenization and lemmatization were applied prior to embedding training. Additionally, embeddings were trained separately for each programming language rather than using a shared corpus. As a result, embedding coordinates are not directly comparable across languages and are interpreted only within language-specific analytical contexts.

Embedding stability was assessed by measuring intra-language cosine similarity variance, which remained below 0.15 across random initializations, indicating within-language stability of semantic representations, despite shorter text length.

4.2. Case Survey Results for Learning Analytics

The survey included 64 non-major undergraduate participants who were enrolled in interdisciplinary programs, comprising learners who focused on syntax and debugging. The survey comprised 49 items to investigate the various aspects of learning challenges. The key areas of focus included the following:

Syntax Understanding: Assessing the perceived difficulty of learning programming constructs. Example Question: “How often do you encounter syntax-related challenges in [specific language]?”.

Debugging Skills: Measuring the ability to locate and resolve errors in code. Example Question: “Rate your debugging proficiency in [specific language] on a scale of 1 to 5.”

Conceptual Understanding: Evaluating learners’ comprehension of paradigm-specific concepts. Example Question: “Which paradigm-specific feature (e.g., recursion, polymorphism) is the most challenging for you?”

The survey results indicated that participants frequently reported debugging and syntax-related difficulties, which were broadly consistent with recurring themes observed in the SO data.

5. Survey Results

This section synthesizes the survey findings. Throughout the Results section, findings are interpreted with attention to language-specific manifestations of paradigm-oriented instruction, acknowledging that observed patterns emerge within a particular instructional and analytical context. Comparisons across languages therefore reflect differences in how paradigmatic concepts are encountered, practiced, and problematized by learners within the given educational context.

By explicitly distinguishing paradigms as theoretical constructs from languages as pedagogical vehicles, this study offers an empirically grounded description of how different paradigmatic styles, when instantiated through concrete languages and course designs, are encountered by novice learners.

5.1. Basic Programming Experience

A total of 64 students participated in the survey. Among them, only 3 students (4.69%) were computer science majors, while the remaining 61 students (95.31%) came from non-computer science disciplines. Given that the primary target of this study is non-major learners, the survey results regarding prior programming experience, preferred programming languages, and programming languages actually used were analyzed (

Table 4).

The survey results showed that Python was the most preferred programming language (53 students, 82.81%), suggesting that it is commonly perceived as accessible by non-major novice learners within the surveyed cohort. In contrast, Java (3 students, 4.69%) and C (4 students, 6.25%) exhibited low preference rates, which may be associated with learners’ perceptions of structural complexity and initial learning burden. No respondents selected Prolog as a preferred language (0 indicating that the limited application scope and inference-based characteristics of logic programming may be perceived as challenging entry points by non-major learners.

In terms of academic year distribution, most participants were third-year (25 students, 39.06%) and fourth-year students (26 students, 40.63%), together accounting for approximately 79.69% of the sample. Although the participants were relatively advanced in terms of academic standing, their actual programming experience was limited. Specifically, 28 students (43.76%) reported having less than one year of programming experience, including 9 students (14.06%) who reported having no prior experience at all. Additionally, 16 students (25.00%) reported less than six months of experience, while 10 students (15.63%) reported between six months and one year of experience, indicating that a substantial proportion of participants remained at a novice level.

These survey findings are broadly consistent with patterns reported in prior studies and public Q&A data, though they do not imply direct correspondence between individual learners and online posts. Indeed, analysis of Stack Overflow data also revealed that novice programmers frequently ask questions related to syntax errors and fundamental concepts [

7]. Therefore, the survey results highlight the importance of programming language selection and entry-stage instructional design for non-major learners and should be interpreted in conjunction with the Stack Overflow analysis presented in subsequent sections.

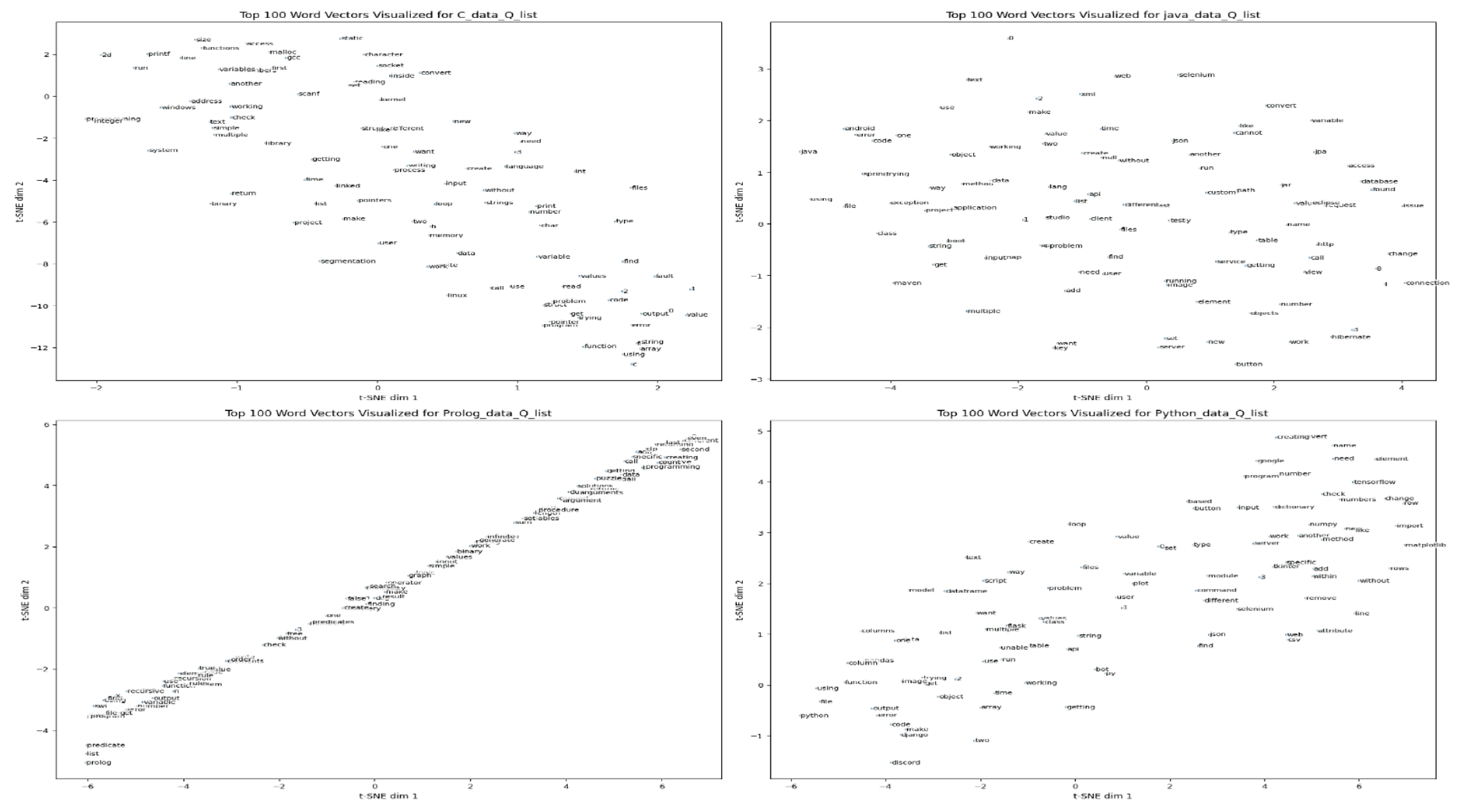

To examine the relationship between self-reported learning difficulties and real-world programming challenges, the survey responses were compared with Stack Overflow (SO) question trends. As shown in the Word2Vec visualization in

Figure 1, embeddings were trained using the

Skip-gram with Negative Sampling (SGNS) architecture. The Skip-gram model optimizes the likelihood of predicting surrounding context words given a target word. Formally, for a sequence of tokens

, the objective is to maximize:

where

denotes the context window size (set to

5 in this study), and

is the total number of tokens in the corpus. The conditional probability

is modeled using word embeddings for input (target) and output (context) words. To reduce the computational cost of the full softmax over the vocabulary,

negative sampling was employed.

Python—which exhibited the highest preference in the survey—also showed a dense distribution of algorithm- and problem-solving-related keywords on Stack Overflow, including algorithm, data, list, dict, loop, function, pandas, numpy, model, and learning. In addition, debugging- and error-related keywords such as error, exception, index, type, value, bug, and traceback were also observed.

This keyword distribution indicates that Python-related questions primarily focus on data processing and data structures, while questions related to memory or system-level errors are relatively less frequent. This pattern may reflect a comparatively lower entry barrier for non-major learners in algorithm-centered tasks, rather than an inherent property of the language.

In contrast, C programming exhibited a visual concentration of procedural and algorithmic keywords such as loop, for, while, function, array, sort, structure, logic, implementation, and calculation, along with debugging-related keywords associated with memory management and runtime errors, including pointer, memory, address, segmentation, error, malloc, and crash. This distribution provides qualitative indications that low-level memory management and pointer usage in C are associated with reported difficulties.

As shown in

Table 5, lexical diversity was highest for Python and Prolog, followed by Java and C, while word counts were highest for C, followed by Java, Python, and Prolog. In terms of lexical diversity [

22,

24], Python and Prolog exhibited similarly high values, whereas C showed the lowest value, possibly due to the frequent use of procedural structures and repetitive expressions. Conversely, C and Java demonstrated the highest word counts, while Prolog showed substantially fewer words, reflecting shorter and more concise question-and-answer texts compared to Python, Java, and C.

In this study, identical tokenization procedures based on raw tokens were applied to the question and answer texts for Python, Java, C, and Prolog. Therefore, the lower word count observed for Prolog cannot be attributed to preprocessing or analytical differences, but rather to language-specific expressive conventions and usage patterns associated with declarative programming in this dataset. Prolog questions and answers tend to be shorter and more compact due to their reliance on logic-centered expressions such as rules, queries, and predicates. These linguistic characteristics provide contextual constraints for interpreting text-based indicators associated with logic-based programming, discussed in later sections.

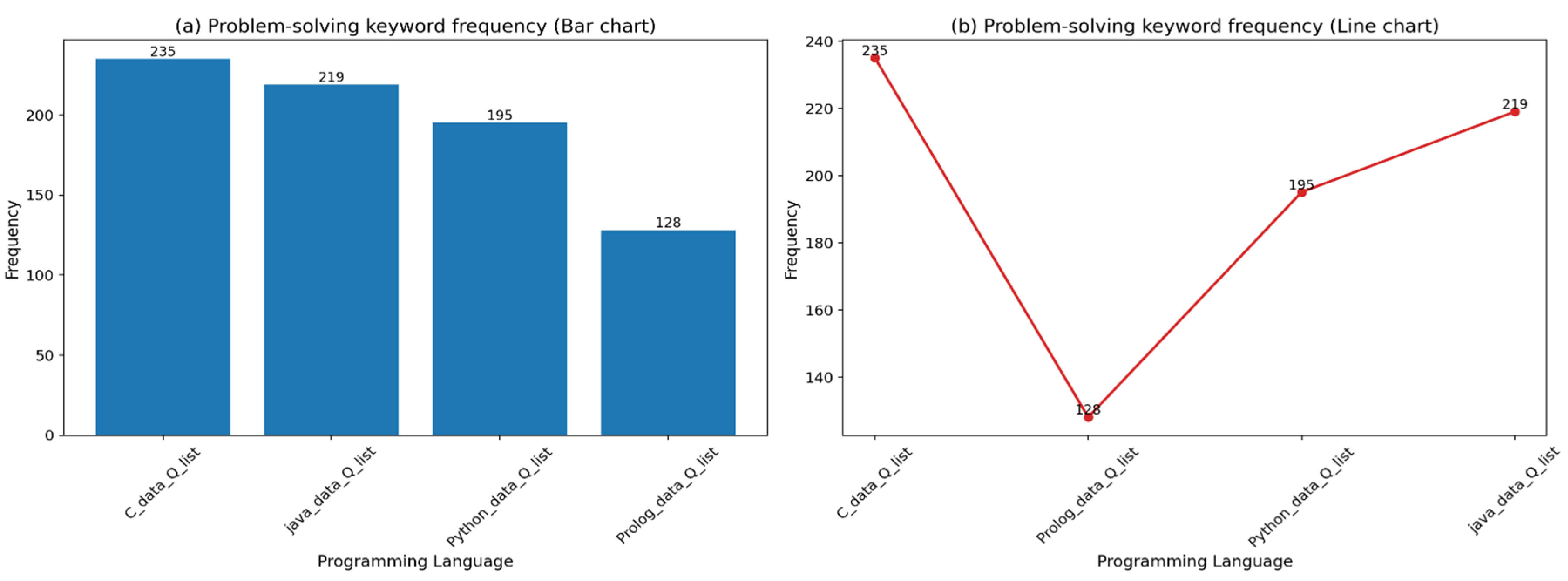

Figure 2 compares the number of questions containing problem-solving keywords across programming languages. The results show that C and Java exhibited relatively higher numbers of problem-solving keyword–based questions, while Prolog showed comparatively lower values. This indicates that the distribution of problem types expressed through questions varies by programming language and reflects differences in syntactic and expressive characteristics across languages.

When interpreted together with the survey results, the trends observed in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, underscoring the importance of instructional designs that are sensitive to paradigm-related differences in learner experience. In particular, the low familiarity with Prolog (4.69%) and its absence as a preferred language suggest the need for more structured learning pathways for logic programming concepts. Accordingly, an instructional design approach that introduces relatively accessible languages at the entry stage and gradually expands toward more abstract paradigms may represent a viable educational strategy.

5.2. Learning Difficulty and Understanding by Programming Paradigm

Table 6 reports text-based difficulty scores derived from Stack Overflow question texts for each programming language, along with their corresponding average difficulty values. The difficulty metric is designed as a proxy for textual complexity rather than a direct measurement of learners’ perceived difficulty. For each question

, three surface-level textual features were extracted:

To ensure comparability across different programming languages and corpora, each feature was normalized using

min–max normalization within the language-specific question set

:

where

.

The final difficulty score for each question was computed as a

weighted linear combination of the normalized features. This score was designed to approximate surface-level textual complexity associated with question expressions, rather than conceptual or cognitive difficulty. Importantly, this metric does not measure learners’ subjective perceptions of difficulty or conceptual understanding collected through surveys [

26]. Rather, it aims to compare patterns of textual expression across language-specific corpora, using identical computational criteria.

Each question’s complexity score was computed as a weighted sum of the overall string length, the number of words per question, and the average word length. This calculation method was uniformly applied to all question texts to reflect differences in textual description and expression.

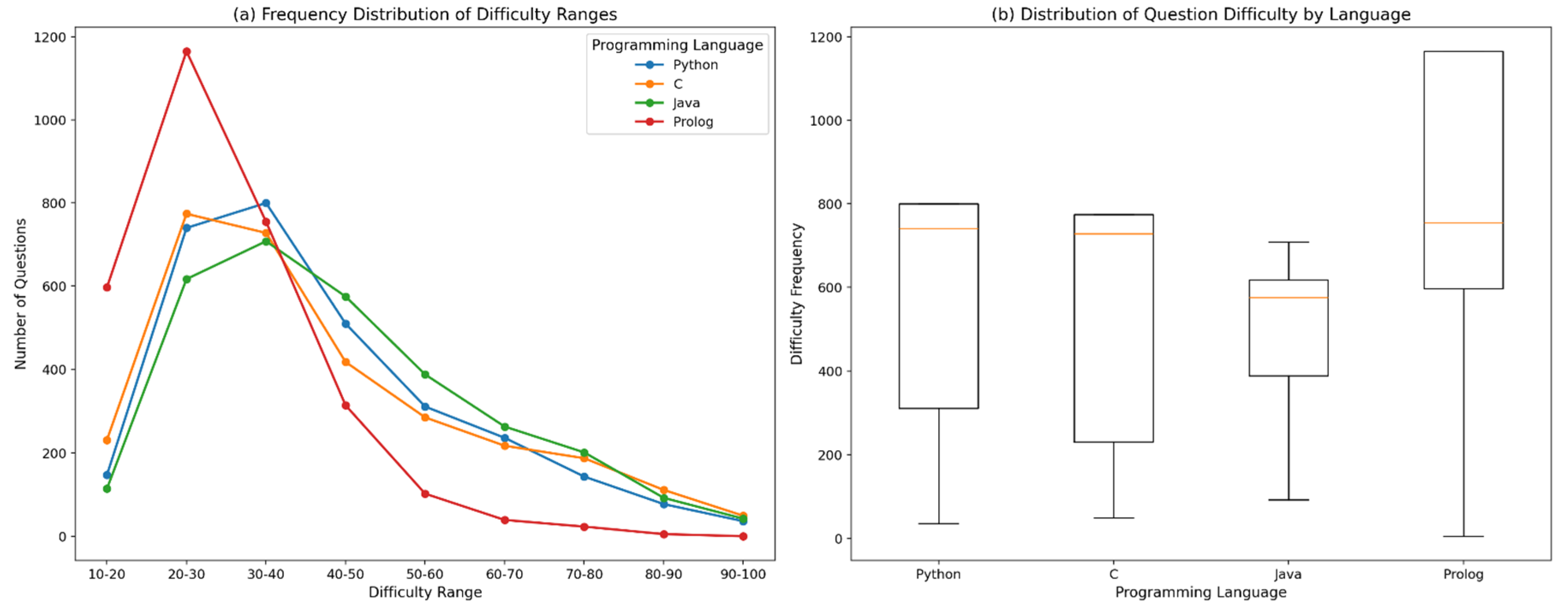

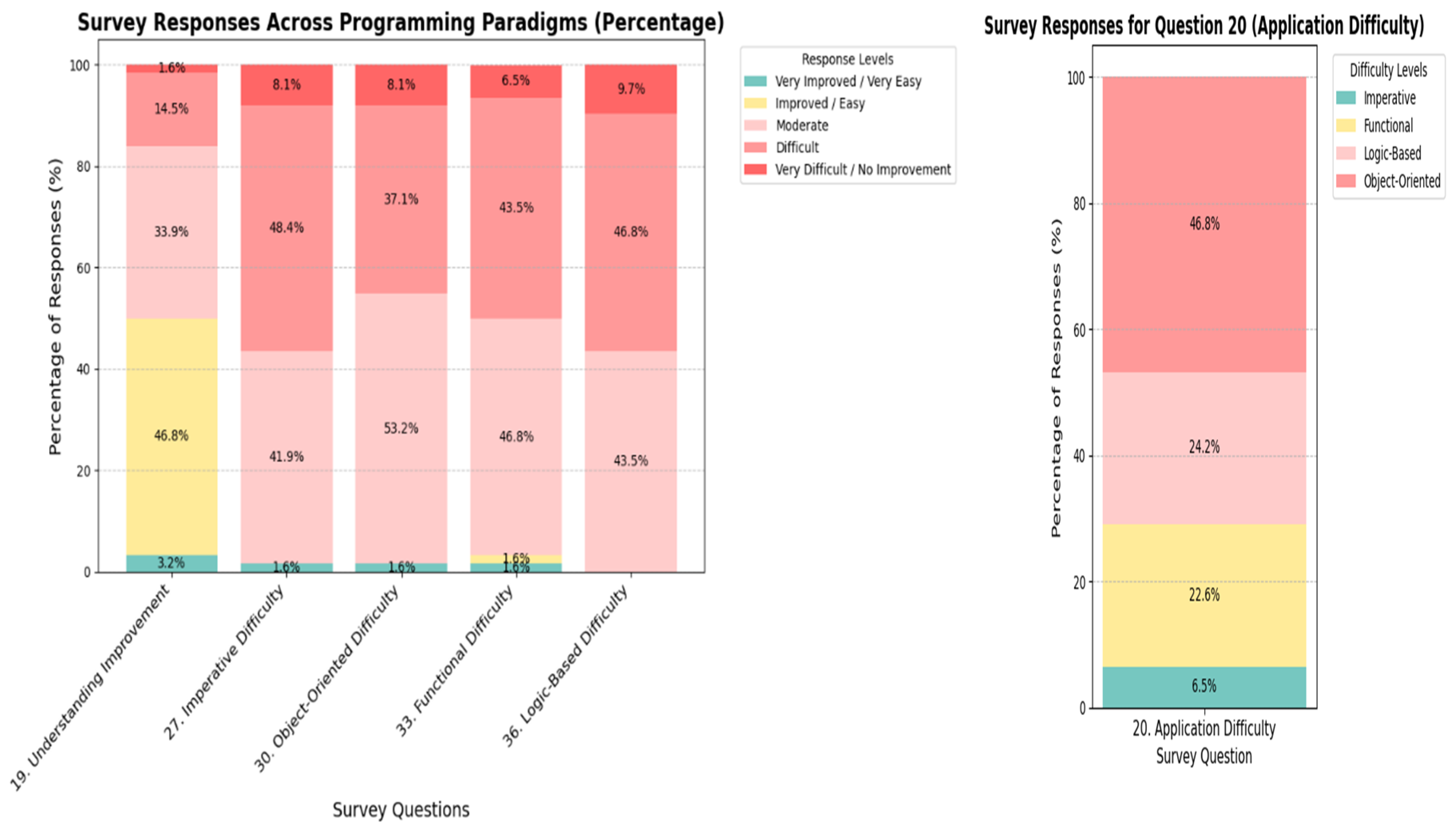

Survey results indicated that the imperative paradigm (Q27: “How would you rate the overall difficulty of imperative programming?”) was perceived as having a moderate level of difficulty (41.9%), while the object-oriented paradigm (Q30: “How would you rate the overall difficulty of object-oriented programming?”) received higher difficulty ratings.

Figure 3 visualizes the distribution of these text-based difficulty scores by discretizing them into ten-point intervals (10–20, 20–30, …, 90–100). For each interval, the number of questions whose difficulty scores fall within the corresponding range was counted:

The final interval

was defined to include both boundary values to ensure complete coverage of the score range. The aggregated frequency counts across intervals were used to generate the histogram-style visualization in

Figure 3.

This range-based analysis highlights how question complexity is distributed within and across programming paradigms, revealing differences in the concentration of low-, mid-, and high-complexity questions. As such,

Figure 3 provides an intuitive overview of paradigm-specific textual difficulty patterns that complement the average difficulty values reported in

Table 6.

Meanwhile, survey results revealed distinct perceptions of learning difficulty across paradigms. For the logic-based paradigm (Prolog; Q36), 9.7% of participants responded “very difficult,” suggesting that declarative syntax and inference-centered problem-solving may impose a high cognitive burden on learners.

For the imperative paradigm (C; Q27), debugging tasks closely associated with low-level system operations—such as pointer manipulation and memory management—emerged as major challenges. This finding is qualitatively consistent with procedural-operation-centered themes observed in the clustering analysis.

The object-oriented paradigm (Q30) showed that 37.1% of respondents rated it as “difficult,” while 53.2% rated it as “moderate,” indicating that object-oriented programming requires a balance between conceptual understanding and practical application.

For the functional paradigm (Q33), responses of “difficult” (43.5%) and “moderate” (46.8%) were relatively evenly distributed, suggesting the need for step-by-step instructional strategies that allow learners to gradually adapt to functional programming concepts.

In

Table 7, multiple document clustering techniques were applied sequentially to question-and-answer texts. First, TF-IDF vectorization was used to transform text data into numerical representations, followed by K-means clustering to identify the basic structure of document clusters. The Elbow method was employed to determine an appropriate number of clusters. Subsequently, hierarchical document clustering and multidimensional scaling (MDS) were used to visually examine inter-cluster relationships and distribution patterns.

To extract keywords that play a central role in cluster interpretation, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was applied to identify top keywords with high probability values within each cluster. These keywords were then used to qualitatively interpret paradigm-specific characteristics.

The results showed that Python prominently featured keywords such as “list,” “file,” and “pandas,” indicating a data manipulation–centered usage pattern and suggesting applicability in data science and analytics contexts. C was characterized by keywords such as “function,” “pointer,” and “array,” reflecting the cognitive burden associated with low-level system operations in imperative programming. Java exhibited keywords such as “class,” “error,” and “type,” highlighting object-oriented design principles and structured, modular programming approaches. Prolog was dominated by keywords such as “engine,” “complexity,” and “unifying,” revealing declarative programming characteristics centered on logic-based problem solving and advanced inference.

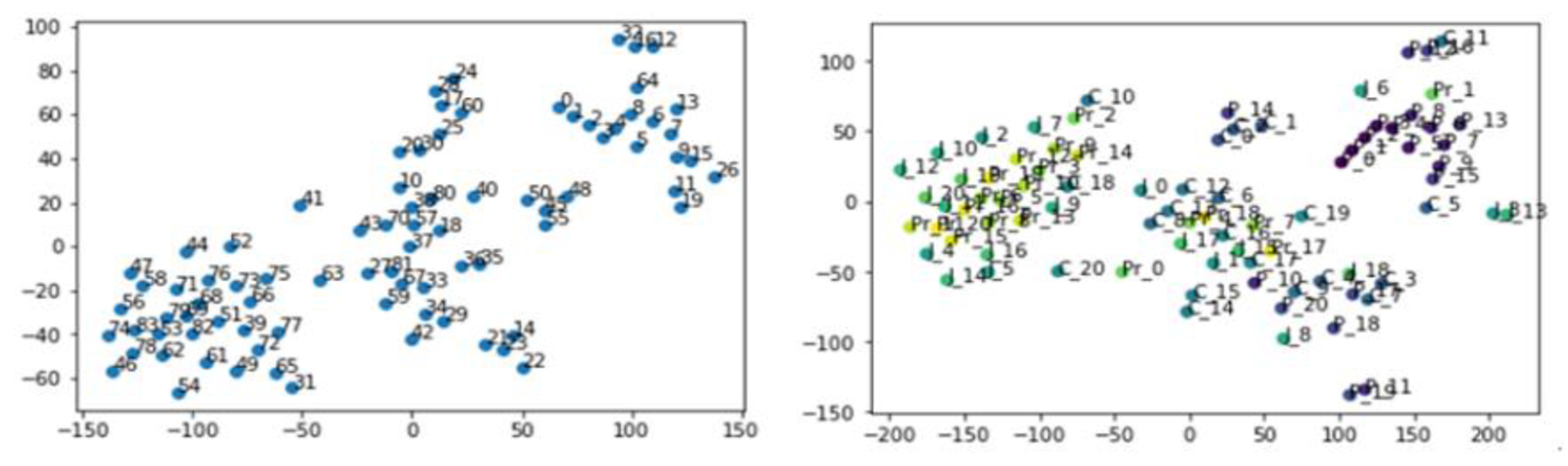

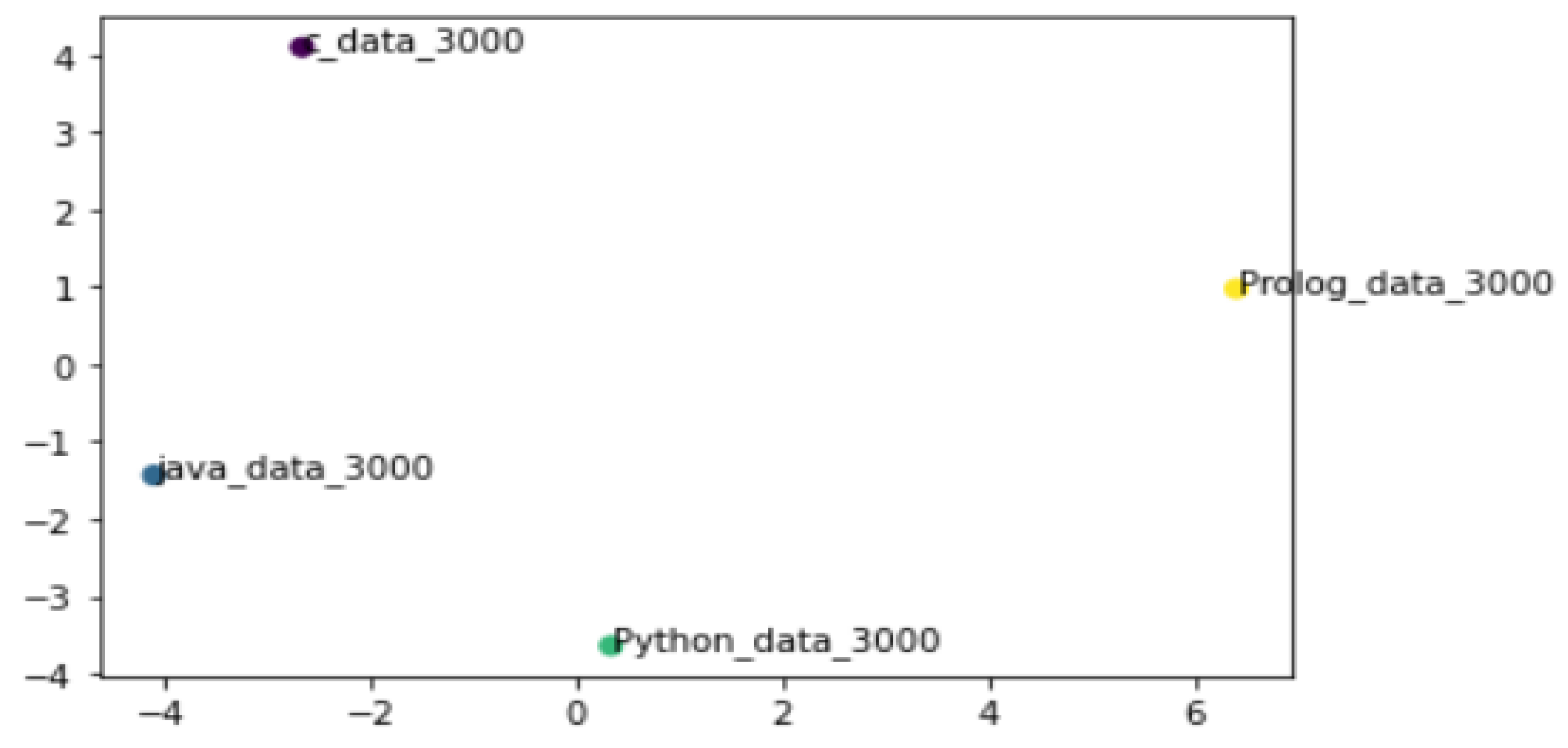

Figure 4 visualizes the relationships among clusters by applying Doc2Vec embeddings to the 21 document clusters derived for each programming language in

Table 7. Specifically, a total of 84 clusters extracted from the four languages were projected into a two-dimensional space, complementing the preceding clustering analysis.

Text clustering was performed using TF–IDF vectorization (maximum features = 200,000, max_df = 0.8, min_df = 0.2, ngram range = 1–3) followed by K-means clustering. The optimal number of clusters (k = 21) was determined using the Elbow method over a cluster range of k = 1–21and validated by silhouette scores (average silhouette coefficient = 0.41), balancing interpretability and intra-cluster coherence.

The visualization revealed that clusters related to C tended to be spatially adjacent, particularly those associated with imperative tasks such as pointer usage and memory operations. This pattern can be qualitatively interpreted as consistent with the debugging-centered learning difficulties reported in the survey (Q27). In addition, Python-related clusters associated with data manipulation and processing appeared relatively cohesive, aligning with the high accessibility reported for Python in the survey results.

Overall, these cluster distributions visually demonstrate that learning focus and reported difficulty patterns differ across paradigm-oriented instructional contexts, highlighting the need for differentiated instructional strategies [

2,

26,

27]. Imperative paradigms require foundational scaffolding through step-by-step guidance and repeated practice on low-level concepts such as pointers and memory allocation. Logic-based paradigms necessitate the integration of example-driven explanations and problem-solving activities to support abstract inference processes. Object-oriented paradigms benefit from reinforcing connections between theory and practice through real-world cases and modular assignments that emphasize structural design principles.

In summary, differentiated teaching strategies are essential. For object-oriented programming, step-by-step guidance and practical examples can reduce perceived difficulty. Logic-based paradigms require scaffolding and real-world examples. Imperative and functional paradigms should focus on building foundational competencies at moderate difficulty levels before gradually introducing advanced concepts.

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Learning Effectiveness

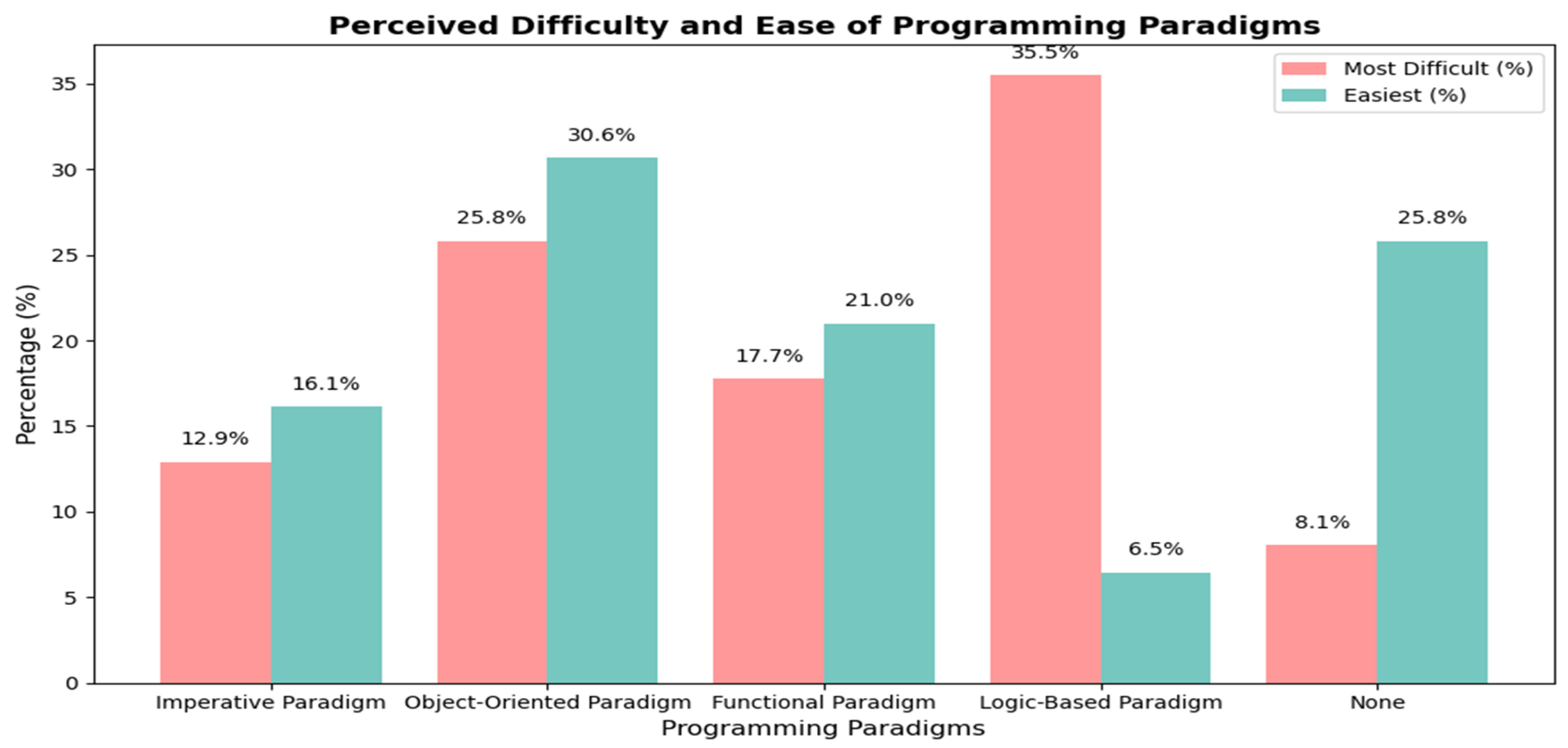

Figure 5 presents survey results based on learners’ subjective perceptions, illustrating differences in perceived difficulty and accessibility across programming paradigms. From the perspective of non-major learners, the logic-based paradigm was perceived as the most difficult (35.5% selected “most difficult”), which may be attributed to the cognitive burden imposed by logical reasoning and declarative syntax. In contrast, the object-oriented paradigm was perceived as the easiest (30.6% selected “easiest”), potentially reflecting its structural clarity and familiarity through practical application experiences. Functional and imperative paradigms were generally perceived as having a moderate level of difficulty. Additionally, 25.8% of respondents reported that no particular paradigm was especially difficult or easy, suggesting that individual prior experience and background may influence learners’ perceptions.

In contrast to the analysis based on learners’ subjective perceptions,

Figure 6 provides an illustrative visualization of relative semantic patterns observed in Doc2Vec embeddings of Stack Overflow question–answer texts, interpreted within language-specific embedding spaces rather than as metric distances across programming languages.

The observed semantic and difficulty-profile similarity between Python and Java should not be interpreted as evidence that Python functions as an object-oriented language in this study. Rather, this convergence reflects a

shared layer of instructional and cognitive demands experienced by learners across the two languages [

10,

12].

Although Python was taught primarily through functional-style constructs, both Python and Java assignments required learners to engage with abstraction, modular decomposition, and multi-step problem structuring. These shared demands give rise to comparable patterns in question formulation, help-seeking behavior, and perceived difficulty, which are captured by the corpus-derived metrics.

From an educational perspective, the Python–Java similarity therefore indicates that learner-facing challenges can converge across languages despite differing paradigmatic emphases, particularly when tasks impose similar levels of conceptual coordination and problem decomposition. This finding underscores the importance of instructional design in shaping learning difficulty, beyond paradigm labels alone.

By comparison, Prolog appeared semantically separated from the other languages, a result that can be can be interpreted as consistent with its declarative orientation and inference-centered instructional emphasis. This tendency is qualitatively consistent with the cognitive burden reported in the learner survey.

Overall, these findings highlight the need for curriculum design that takes into account the alignment between learners’ needs and the inherent characteristics of different programming paradigms.

5.4. Educational Implications of Keyword Analysis

The keyword analysis (

Section 5.6) reveals paradigm-specific problem-solving challenges faced by non-major novice learners, which closely align with the survey results.

Algorithm-oriented questions in Python (Q20): Python exhibits a high frequency of algorithm-related keywords (

Figure 1), suggesting strong associations with data science and machine learning contexts. In the survey, Python was evaluated as having a moderate level of difficulty, with learners reporting advantages in readability and flexibility. The Word2Vec analysis in

Figure 1 further highlights data-processing-oriented keywords such as

“tensorflow” and

“pandas”, reinforcing Python’s relevance to applied problem-solving tasks.

Perceived application difficulty across paradigms (Q20): Object-oriented programming (OOP) was reported as the most difficult paradigm to apply in practice (46.8%), followed by logic-based (24.2%) and functional paradigms (22.6%). In contrast, the imperative paradigm was perceived as foundational, with the lowest reported application difficulty (6.5%).

Debugging challenges in C (Q27): Keywords such as

“pointer” and

“malloc” indicate a high frequency of debugging-related questions in C (

Table 7,

Figure 1). This reflects the complexity of low-level memory management as a major barrier for novice learners. Consistently, the survey (Q27) showed that 48.4% of respondents rated imperative programming as “difficult,” while 41.9% evaluated it as “moderate.”

Figure 2 further illustrates that C has a higher proportion of problem-solving questions.

Logical reasoning challenges in Prolog (Q36): Prolog focuses on logical inference and declarative programming (

Figure 1), as evidenced by keywords such as

“predicate” and

“unification.” In the survey (Q36), 9.7% of respondents rated Prolog as “very difficult,” the highest among all paradigms. Moreover,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 indicate that Prolog questions are more logic-oriented rather than centered on explicit problem-solving tasks.

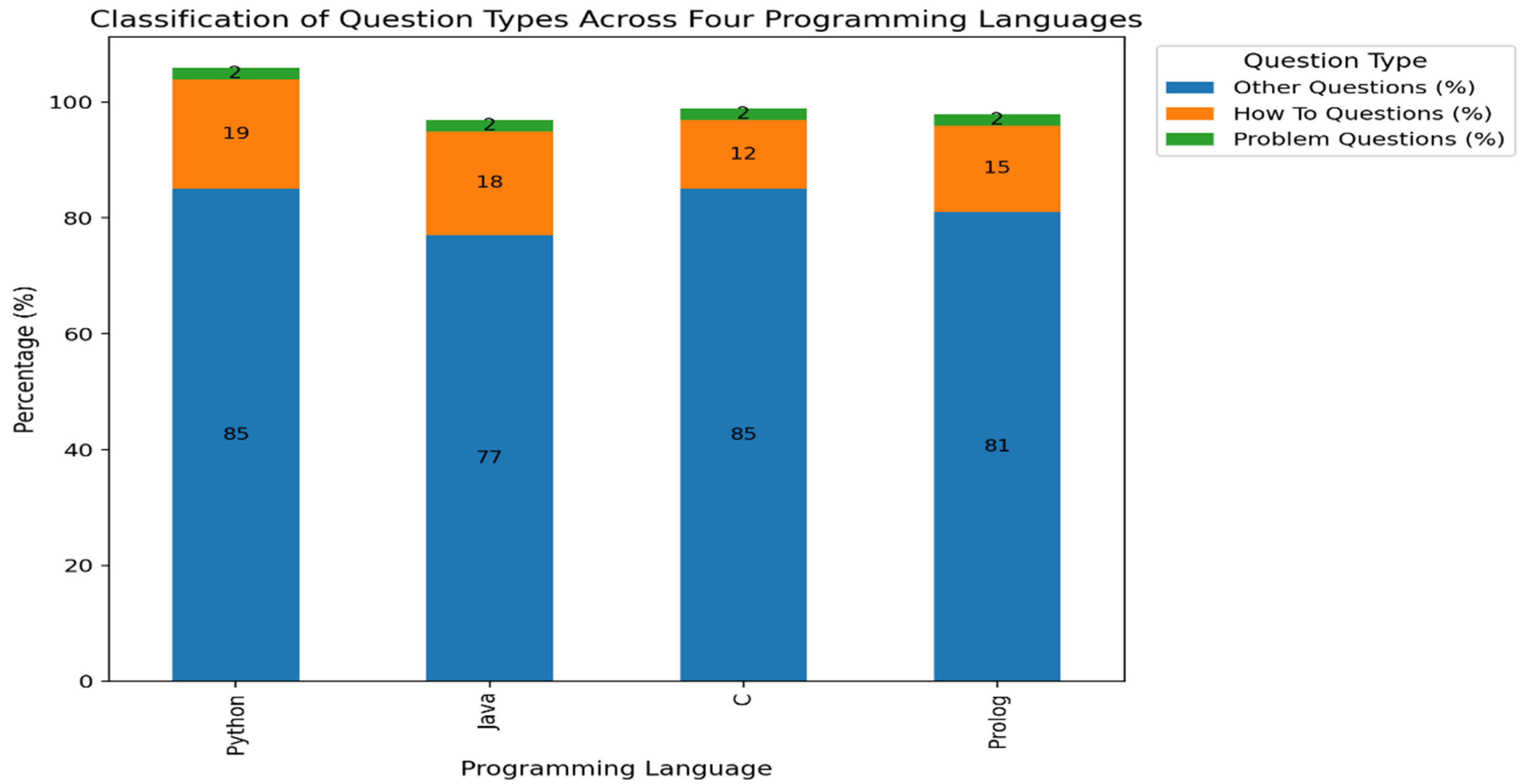

Figure 2 visualizes the distribution of problem-solving keywords across Python, C, Java, and Prolog, highlighting that C emphasizes debugging and error resolution, while Prolog places greater emphasis on logical inference tasks.

Figure 7 presents a comparison of question types—

Problem,

How-To, and

Other—based solely on Stack Overflow question data across the four programming languages. Question classification was conducted using an automated rule-based approach. Questions containing explicit problem-indicating expressions such as

“problem” were categorized as

Problem questions, while those including procedural request expressions such as

“how to” were classified as

How-To questions. All remaining questions, including conceptual explanations, error context descriptions, and general inquiries, were categorized as

Other. The same criteria were applied consistently across all languages.

The analysis shows that Other questions accounted for the largest proportion across all four languages, indicating that Stack Overflow questions frequently involve contextual explanations or conceptual inquiries rather than explicitly stated problems. How-To questions were relatively more prevalent in Python and Java, reflecting the high frequency of early-stage learning questions that require procedural guidance. In contrast, the proportion of Problem questions was consistently low across all languages, which may be attributed to the limited explicit use of the term “problem” in question formulations.

These question type distributions partially align with the survey findings. In the learners’ subjective perception survey, the object-oriented paradigm was perceived as the most difficult in terms of practical application (Q20, 46.8%). The imperative paradigm also showed a high proportion of respondents rating it as “difficult” or above (Q27, 56.5%), while the logic-based paradigm exhibited the highest perceived cognitive burden (Q36, “difficult/very difficult” at 56.4%). Together with the relatively higher proportion of How-To questions in Prolog, these findings suggest that non-major learners require more procedural explanations and usage guidance in logic-based languages than direct problem-solving support.

Figure 8 compares learning challenges across programming paradigms based on learners’ subjective survey responses. The results indicate paradigm-specific differences in perceived cognitive load and learning difficulty, offering important implications for curriculum design. For example, Python is perceived as relatively accessible in algorithm-centered problem-solving contexts, suggesting strong potential for integration with real-world problem-solving activities. In contrast, C presents a high cognitive burden due to low-level concepts such as pointer usage and debugging, while Prolog’s emphasis on logical inference and declarative thinking highlights the need for structured, step-by-step learning support.

By leveraging large-scale public Q&A data from Stack Overflow alongside over 20 years of instructional experience, this study complements prior research on programming paradigm education. Whereas previous studies (e.g., [

22,

24]) have relied on relatively small controlled samples, this study integrates community-generated data with comprehensive survey results, enabling a broader empirical examination of paradigm-specific syntactic and cognitive challenges.

In this study, keyword frequency is not interpreted as a direct measure of learning difficulty [

26]. Rather, recurrent terms (e.g.,

pointer,

malloc) are treated as indicators of

cognitive attention density, reflecting recurring points of reported difficulty or uncertainty where users seek external assistance.

This interpretation aligns with cognitive load theory, which suggests that concepts requiring frequent external clarification often impose higher intrinsic or extraneous cognitive load. Accordingly, keyword frequency is triangulated with survey responses and clustering results, ensuring that educational implications are derived from convergent evidence rather than isolated lexical counts.

5.5. Mapping Survey Results and Stack Overflow Insights

By mapping learners’ subjective survey responses to patterns observed in large-scale public Q&A data from Stack Overflow, this study identified overlapping learning difficulties and paradigm-specific characteristics [

8,

28].

Imperative Paradigm (C): In the survey (Q28), learners identified memory management (30.65%) and control-flow debugging (19.35%) as the most challenging aspects. Correspondingly, Stack Overflow data showed a high frequency of questions related to variable handling, memory allocation, and pointer-related errors. This alignment suggests that memory management remains a persistent challenge for both novice learners and broader programming communities.

Object-Oriented Paradigm (Java): Survey results (Q31) indicated that encapsulation and information hiding (32.26%), as well as understanding class–object relationships (19.35%), were major sources of difficulty. These findings correspond with Stack Overflow trends in which issues related to inheritance and encapsulation were prominently discussed, highlighting that structural understanding of object-oriented concepts imposes a significant cognitive load on learners.

Functional Paradigm (Python): In the survey (Q34), recursion (25.81%) and higher-order functions (17.74%) were frequently reported as difficult topics. This is consistent with Stack Overflow patterns, where recursion logic and lambda functions are repeatedly discussed in Python-related questions. Such convergence indicates the need for gradual scaffolding when teaching functional programming concepts.

Logic Paradigm (Prolog): Survey responses (Q37) identified recursive rule debugging (20.97%) and query optimization (25.81%) as major obstacles. Similarly, Stack Overflow data frequently featured questions related to backtracking and logical inference. These findings suggest that visualization of inference processes and enhanced debugging support can play a critical role in reducing cognitive burden in logic-based programming.

In this study, a misconception is operationally defined as a recurrent, semantically coherent cluster of questions that consistently reflect incorrect assumptions or flawed mental models, rather than isolated errors or task-specific difficulties.

Clusters were labeled as misconceptions only when (a) the same erroneous reasoning pattern appeared across multiple independent questions, (b) survey data indicated corresponding conceptual confusion, and (c) expert review confirmed the presence of a stable misunderstanding rather than a context-specific implementation issue.

5.6. Syntactic and Semantic Similarities Across Paradigms

Vector representation analysis based on cosine similarity revealed both semantic overlap and divergence among programming paradigms. By vectorizing question and answer texts, high semantic similarity was observed for several language pairs. C–Java (similarity = 0.97): These two languages share an imperative-based structure, with Java’s object-oriented features extending procedural control flow. This overlap suggests the presence of transferable knowledge for learners, which is qualitatively consistent with survey results (Q29, Q31) indicating that concepts such as variable initialization and class–object relationships were perceived as relatively accessible. Python–Java (similarity = 0.97): Both languages emphasize object-oriented principles, including encapsulation and inheritance. This corresponds to survey findings (Q31) in which learners perceived object-oriented concepts as presenting a “moderate level of challenge,” suggesting that shared conceptual structures may facilitate learning transfer across these languages. Prolog–C/Java (similarity = 0.91): Although Prolog’s declarative paradigm exhibited partial semantic overlap with the algorithmic and procedural expressions of C and Java, survey responses (Q37) reported high cognitive demands related to logical inference and recursive rule debugging. This indicates that logic-based paradigms require fundamentally different modes of reasoning despite surface-level semantic similarities.

5.7. Educational Implications

An analysis of learners’ subjective perception surveys (Q39, Q40) indicates that learners relied heavily on online resources (83.87%) and error message interpretation (61.29%) to overcome paradigm-specific difficulties. This finding suggests the need to explicitly integrate error message interpretation skills and debugging strategies into the curriculum.

Based on these results, the educational implications for paradigm-specific curriculum design are as follows.

• Functional Programming (Python, Q34, Q35)

In functional programming learning, the most difficult elements were understanding recursive functions (25.81%) and pipeline-based data processing (e.g., map, filter) (24.19%), while difficulties in understanding and using higher-order functions (17.74%) were also frequently reported (Q34). This reflects the fact that the functional paradigm requires learners to move beyond loop-centered procedural thinking toward abstract data flows and function composition. In contrast, function definition and invocation were identified as the easiest elements (Q35, 64.52%), indicating continuity between Python-based functional learning and prior imperative or procedural programming experience. Accordingly, functional programming education should emphasize gradual scaffolding centered on recursion and higher-order functions rather than focusing solely on syntactic entry points. Leveraging Python’s intuitive syntax and immediate feedback also makes it suitable for placement at the introductory stage of the curriculum.

• Object-Oriented Programming (Java, Q31)

In object-oriented programming learning, encapsulation and information hiding (32.26%) were identified as the most difficult elements, followed by understanding class–object relationships (19.35%) and managing interactions and dependencies among objects (16.13%) (Q31). These results suggest that the object-oriented paradigm demands structural reasoning and design-oriented thinking rather than mastery of isolated syntactic constructs. Consequently, a concept-centered instructional approach combined with gradual progression using visual models such as UML diagrams is likely to be effective in object-oriented programming education.

• Logic Programming (Prolog, Q37)

In logic programming learning, the most challenging aspects were handling and optimizing queries with complex conditions (25.81%), writing and debugging recursive rules (20.97%), and understanding backtracking and inference processes (14.52%) (Q37). These findings reflect the inherent difficulty learners face in intuitively tracing execution flow when programming relies on automated inference mechanisms rather than explicit control structures. Therefore, logic programming education requires scaffolding strategies and instructional tools that enable learners to visualize or step through inference processes.

• Imperative Programming (C, Q28, Q29)

In imperative programming learning, the most difficult element was variable and memory management (30.65%), followed by debugging program control flow (19.35%) and resolving low-level memory-related errors (16.13%) (Q28). These results indicate that the need to simultaneously track execution flow and memory states imposes substantial cognitive load on novice learners. In contrast, variable declaration and initialization (43.55%) and basic input/output handling (37.10%) were perceived as relatively easy elements (Q29). Based on these findings, imperative programming education should incorporate step-by-step tutorials on low-level abstractions and memory management to reduce the gap between novice and advanced learners.

Taken together with the syntactic and semantic similarity analysis (

Section 5.6), these survey findings suggest that effective programming curricula should reflect real learner difficulties observed on open learning platforms such as Stack Overflow. Such curricula can be further supported through adaptive assessment mechanisms and personalized learning systems.

5.8. Key Findings from Surveys and SO Analysis

The results of the learners’ subjective perception surveys, together with large-scale publicly available Q&A data from Stack Overflow, reveal clear strengths and challenges across different programming paradigms. According to the survey results, the object-oriented programming (OOP) paradigm was perceived as the most accessible paradigm (30.65%, Q42) and was also the most highly recommended paradigm for non-major learners (40.32%, Q43). Python was likewise preferred as an introductory language due to its intuitive syntax and immediate feedback mechanisms, a tendency that is also reflected in Stack Overflow question patterns.

In contrast, Prolog was perceived as the most difficult paradigm because of its abstract syntax and inference-based approach (9.7% selected “very difficult,” Q36), and it received the lowest recommendation rate (11.29%, Q43). These findings these findings suggest that logic-based paradigms may impose higher perceived cognitive demands and may require additional scaffolding when introduced to novice learners.

In addition, a majority of survey respondents expressed a positive attitude toward a paradigm-based learning approach (62.90%, Q47) and preferred a staged learning sequence progressing from imperative to object-oriented, logic-based, and functional paradigms (Q49). This preference indicates that an instructional approach that first establishes foundational programming thinking and then gradually transitions to more abstract paradigms may be effective.

Based on the integration of survey findings and Stack Overflow analysis, this study derives the following educational recommendations.First, Python is appropriate as an introductory language for novice learners.Second, programming education may benefit from a staged structure that progresses from imperative to object-oriented, logic-based, and functional paradigms.Third, logic-based paradigms such as Prolog should be positioned within advanced courses that emphasize reasoning and problem-solving.Fourth, interactive learning tools, such as AI-based classifiers, can be utilized to diagnose learners’ difficulties and provide targeted instructional support [

29,

30].

6. Conclusion

This study investigated programming paradigm education for non-computer science majors by integrating learners’ subjective perception survey results with large-scale public Q&A data from Stack Overflow. The findings indicate that Python, as instantiated in the instructional context examined in this study, is perceived by non-major learners as suitable for introductory programming due to its relatively low entry barrier, although difficulties frequently emerge during debugging tasks. Java, in the instructional settings analyzed, requires additional pedagogical scaffolding to support learners’ understanding of object-oriented design principles. C is associated with substantial learning challenges related to low-level concepts such as memory management, while Prolog, due to its inference-centered declarative paradigm, tends to impose higher cognitive demands and may be more suitable for learners with prior programming experience. Consistent with these results, the survey revealed that object-oriented paradigms were perceived as relatively more accessible, whereas logic-based paradigms were associated with the highest perceived difficulty among non-major learners.

Through this analysis, the study provides empirical evidence suggesting that different programming paradigms are associated with distinct patterns of cognitive and practical learning challenges among novice, non-major learners. By triangulating large-scale analyses of public Stack Overflow Q&A data with reflective insights drawn from over 20 years of teaching experience in the Programming Languages Theory (PLT) course at Ewha Womans University, this study highlights the need for paradigm-sensitive instructional strategies grounded in learner-facing difficulties. The PLT course, designed for both computer science majors and non-majors enrolled in interdisciplinary programs such as X+SW and X++SW, serves as a representative example of how foundational programming education can be delivered effectively regardless of students’ academic backgrounds.

Beyond immediate classroom applications, the findings offer important implications for educational policy and curriculum development. The proposed paradigm-based learning framework may be adaptable to university-level education and potentially extendable to online courses, coding bootcamps, and secondary education programs, subject to contextual and curricular differences.

Future research should incorporate a broader range of programming languages and instructional contexts, and more explicitly examine how paradigm-oriented instruction interacts with cognitive load, prior knowledge, and task design in shaping skill acquisition. In addition, more sophisticated analytical approaches leveraging large-scale learning data may enable the expansion of personalized learning support systems and adaptive instructional strategies. We also plan to provide analytical outputs of this study, directly informing adaptive learning systems, and by enabling the construction of a paradigm-aware learner diagnostic model. Specifically, cluster labels, keyword salience scores, and paradigm-specific error profiles can serve as features in a supervised classifier (e.g., Random Forest) to predict learner difficulty states. Such a model could potentially recommend targeted instructional interventions, example sets, or debugging scaffolds based on detected learner profiles, serving as a foundation for future adaptive learning systems.

Overall, this study, through the integration of survey data and large-scale public Q&A analysis, provides convergent evidence that learning patterns and cognitive demands vary across programming paradigms as experienced by non-major learners. It underscores the need for a structured, progressive, and adaptive approach to programming education tailored to non-major learners. By elucidating paradigm-specific learning challenges faced by novice, non-major learners, this work contributes to the development of evidence-informed practices that can support more intentional and adaptive programming curriculum design.