1. Introduction

Supply chain models indicate that during the next two decades, the demand for copper will exceed the total tonnage that has ever been mined throughout earth history. This supply deficit is exacerbated by reduced production from major mines in Chile, Peru and Indonesia, a situation that has been compounded by a dearth of discoveries and by a reduction in the size and grade of these deposits. These factors provide the rationale for exploration and discovery of new copper-rich systems, in geopolitically safe jurisdictions. Cu-Au bearing porphyry deposits are attractive exploration targets because, although they have low copper and gold grades, e.g., 0.5 to 1.5 wt% Cu and 0.1 to 1.5 g/t Au, they are high tonnage systems, ranging from 10

6 to 10

9 tonnes [

1,

2].

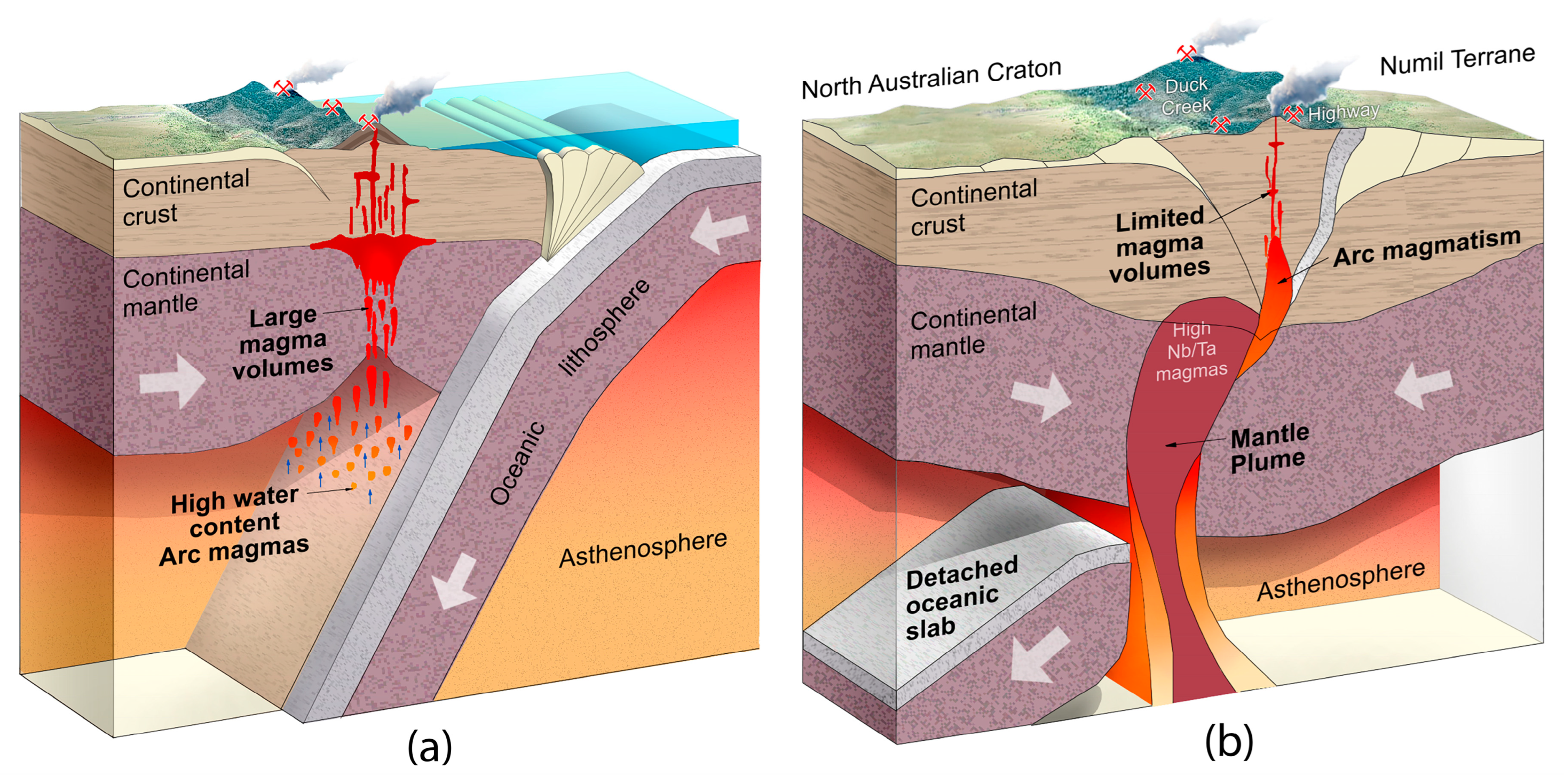

Porphyry deposits occur in continental crust above subduction zones, where oceanic slabs release volatiles during dehydration, metasomatizing the overlying mantle wedge, facilitating partial melting and forming water-rich, metal-bearing oxidized juvenile mafic to felsic magmas [

3,

4,

5]. However, Porphyry deposits also occur in post-subduction continental collision zones, associated with less hydrous magmas [

6,

7]. Metals are derived from several sources [

2,

8,

9,

10]. Copper is largely derived from hydrated subducted oceanic lithosphere and is introduced into the overlying mantle wedge by hydrous fluids. Metals are also derived from alkaline and tholeiitic plume magmas that enter the mantle wedge via slab tears, some of which may be “fossil” tears [

8,

10]. Porphyry systems containing a significant plume component are also generally enriched in Au and PGEs [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In water-rich sulphate bearing oxidized magmas that generate porphyry Cu-Au deposits [

17], sulphur controls the behaviour of Cu and other chalcophile elements, due to the high partition coefficients that exist between these elements in sulphides and silicate melts. Cu-rich sulphides in parental magmas are destroyed by oxidation increasing the chalcophile element concentration of the resulting sulphur-undersaturated magmas [

18]. In these sulphide undersaturated magmas Cu and Au both behave like incompatible elements [

17], enabling chalcophile element concentrations to increase in evolving sulphate-bearing magmas. Precipitation of metals in porphyry systems is finally driven by sulphate reduction, crystallization of magnetite, decreasing pH and degassing of oxidized gases [

23]. Elements liberated from sulphides by sulphate reduction are scavenged by aqueous fluids. These fluids transport metals to shallower depths, into epithermal systems above the porphyry stockwork mineralisation [

20]. Such epithermal vein and breccia precious metal-rich systems form from silica- and bicarbonate-rich hot springs at palaeo-depths of less than 1 km. [

21]. forming a distinctive array of textures, that are valuable exploration vectors [

22].

Porphyry deposits are mainly preserved in less eroded Phanerozoic upper crust at depths between 2–4 km [

23,

24]. However, a few examples of Precambrian porphyry-epithermal mineralisation have been reported. For example, in the Archaean (2.83–2.82 Ga) Kolmozero–Voronya greenstone belt in the Kola Peninsula [

25], in the Palaeo-to-Meso-Archean North Pilbara Terrane [

26] and in Neoarchean crust at Boddington in the Southwest Yilgarn craton [

27]. Porphyry mineralisation of Palaeoproterozoic age has also been described from the Tapajós Mineral Province in Amazonia, Brazil [

28] and the Great Bear magmatic zone in Canada [

29]. In fact, in the Great Bear magmatic zone, there is a continuum of deposits styles ranging between iron oxide coper gold IOCG mineralisation and arc-generated porphyry Cu-Au deposits [

30]. Temporally and spatially associated IOCG and porphyry mineralisation of Mesoproterozoic age also occurs in the Gawler Craton, South Australia [

31]. These provide a further example of the close spatial association between IOCG and porphyry deposits reported from Northern Chile [

32]. According to Sillitoe [

33] this close association could reflect variation in level of exposure, with IOCG magnetite-Cu-Au deposits occurring at depth and oxidized porphyry style hematite Cu-Au mineralisation forming at shallower crustal levels.

In this paper, we report the discovery of Mesoproterozoic post-collisional porphyry and epithermal mineralisation in the eastern segment of the Mount Isa Block. It is preserved in a zone of low strain in the core of the Mitakoodi anticline, approximately 25 km southwest of Cloncurry. The mineral system is hosted by a suite of post-tectonic intrusive lithologies, that include tholeiitic ferrogabbro, leuco-gabbronorite and anorthosite, as well as an alkalic suite that includes websterite, ultramafic lamprophyre, melilite-bearing gabbro, and monzodiorite. These units crop out as roof pendants that intrude Marraba Volcanic meta-basalt, meta-andesite, tuffaceous units. Occurring above the porphyry mineralization, at a higher palaeo-crustal level, are sheets of carbothermal lithologies and associated siliceous crackle breccias that preserve distinctive epithermal textures indicative of deposition from fumarolic CO2-rich fluids. The epithermal vein and breccia system has a strike length of > 20 km and is structurally controlled by axial plane shear zones of parasitic folds on the regional Mitakoodi anticline.

We review key lithogeochemical features of the Highway-Duck Creek mineral system using an extremely large petrological geochemical data base. Using pivotal geochemical vectors that facilitated the discovery, we present an alternative metallogenic model for the Cloncurry region that better accommodates the geodynamic model for the tectonic evolution of the eastern flank of the North Australian Craton. Given the coherence of the lithogeochemical data, this model may be applicable to other deposits in the region, particularly, to the so-called, “within craton IOCG deposits” that have recently been classified as “intracratonic copper-gold deposits” by Brauhart and Groves [

34].

The Mount Isa block, also referred to as the NWMP (

Figure 1), is spectacularly enriched in a wide range of metals, including the Tier 1 sediment-hosted Mount Isa copper deposit, and the Ernest Henry iron–oxide–copper–gold (IOCG) deposit [

35,

36]. However, since discovery of the Ernest Henry deposit more than 30 years ago, the region remains remarkably under explored and few significant new discoveries have been made. In view of the significant metal endowment of the province, this limited exploration success is an enigma. It may reflect the fact that current exploration models do not fully accommodate the possible existence of different mineral systems. Alternatively, it may simply reflect the fact that “barren” magnetic targets have been drilled rather than “fertile” non-magnetic hydrothermally altered targets.

2. Geological Background

Exploration in the in the Cloncurry segment of the NWMP has largely focused on the post-Isan Orogeny Cu-Au-Co-REE-Re-Mo-U IOCG, or iron sulphide-rich (ISCG) mineral systems. Metals are interpreted to have been derived either from a granitic source, such as the Williams-Naraku Batholith; [

37], or by mixing between magmatic fluids with basin brines [

38,

39,

40]. Fluid inclusion studies, and both stable and rare gas isotopes indicate that, although fluids largely display crustal isotopic signatures, there is a cryptic mantle signature [

41]. However, neither the granitic, or the brine source, accounts for the wide range of chalcophile (Ag, As, Bi, Cd, Cu, Hg, In, Pb, S, Sb, Se, Te, Tl, and Zn), siderophile (Co, Ni, Mo, W, Re, Os, Pt, Pd and Au) or lithophile (Sc, V, Cr, Y, Zr, Nb, REE, Th and U) abundances reported in these deposits. The multi-element association of Co-Ni-V-Sc-PGE with high Nb/Ta ratios reported in many Cloncurry deposits, is clearly inconsistent with derivation from a crustal granitic source and requires the involvement of an ultramafic/mafic mantle-plume component.

Such an alkaline ultramafic suite occurs at Mount Cobalt, ~90 km south of Cloncurry [

42]. These lithologies include olivine-bearing pyroxenites, with a superchondritic average Nb/Ta ratio of 25. As discussed later, elevated Nb/Ta ratios are clearly inconsistent with a crustal metal source, indicating Nb-Ta fractionation in either a mantle plume alkaline magmatic system [

43], in metasomatized continental lithospheric mantle [

44] or in deep arc eclogitic cumulates stored between 400 and 650 km in the transition zone [

45]. The Mount Cobalt lithologies are extremely enriched in Co 10 wt.%, Ni 3117 ppm, Sc 278 ppm, Au 5 ppm, Pd 8 ppb, Pt 3.7 ppb, and they have significant concentrations of heavy rare earth elements, Dy up to 315 ppm and Tb up to 90 ppm. Thus, these lithologies provide direct evidence of a viable ultramafic source that accounts for the anomalous highly siderophile elements (Co, Ni, Mo, W, Re, Os, Pt, Pd) and Au in Cloncurry district mineral systems.

Furthermore, Ca-rich pyroxenites, melilite-bearing gabbroic lithologies and ultramafic lamprophyres with elevated superchondritic Nb/Ta ratios, up to 202, with an average of 48.6 (SD 29), are also present at the Elaine Dorothy copper prospect, near Mary Kathleen uranium mine (

Figure 1). They define a significant and continuous depth interval between 232m and 871m. Mafic lithologies with superchondritic Nb/Ta ratios also present at Lawlor (

Figure 2), ~10 km northeast of Highway, where values range up to 390 an average of 54 (SD 81). These examples clearly provide additional evidence for the role of mafic alkaline magmatism in the area [

46].

Such cryptic evidence for the role of plume magmatism within the eastern segment of the North Australian Craton, and the metal association of high-K calc alkaline hosted porphyry mineralisation in the eastern NWMP is consistent with the inferred geodynamic evolution of the region. The eastern segment of the North Australian Craton is interpreted to be an early Proterozoic convergent Andean margin that developed above a west dipping subduction zone [

47]. This interpretation was subsequently confirmed by reflection seismology, with the identification of a prominent west dipping feature, the Gidyea Suture, that extended below the Mount Isa Block that juxtaposed the outboard suspect Numil terrane with the North Australian Craton [

48,

49]. Thus, the Mesoproterozoic metallogenic endowment of the eastern NWMP, appears to reflect the geodynamic interplay between subduction zone magmatism, back arc basin rift magmatism, slab tear facilitated tholeiitic and alkaline plume magmatism, collisional orogenesis and finally crustal anatectic magmatism that produced the regionally widely distributed alkaline and peraluminous Williams Naraku Batholith intrusions.

The involvement of Mesoproterozoic intraplate tholeiitic and alkaline plume magmatism in the NWMP is consistent with the geodynamic model that explains the breakup of the Columbia supercontinent, when the Paleo-Australian components of Columbia, i.e., the Gawler, Curnamona and North Australian Cratons traversed an upwelling mantle plume [

50,

51]. The eastern margin of the North Australian Craton in the Cloncurry area is a collisional orogenic belt, comprising an accreted collage of subduction generated Palaeoproterozoic crust and telescoped back arc basins [

36,

52]. As collisional orogens are commonly underlain by slab tears [

53,

54], these tears provide a window for penetration by an upwelling plume into either the mantle wedge or the sub-continental lithospheric mantle. The slab tear window most likely accreted to the base of the sub-continental lithospheric mantle where it provided a conduit for ingress by upwelling plume magmas. Slab tears are a common feature of continent-continent collisional environments [

54]. Metals in Mesoproterozoic NWMP deposits are interpreted to have been derived from two sources; Cu from altered subducted oceanic crust that was transported via hydrous fluids into the mantle wedge, and Cu, Au and platinum group elements introduced into continental lithosphere by tholeiitic and alkalic plume [

55,

56].

2.1. The Highway - Duck Creek Mineral System

Epithermal Au-Te-W-REE mineralisation, and the underlying porphyry Cu-Au-Co-Ni-Sc system, discovered southwest of Cloncurry (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) is a greenfield discovery as there no evidence in the field to indicate any previous mining activity in the area. Although the area contains a myriad of historic supergene copper workings, it had been overlooked for modern exploration for almost 100 years. The discovery was made using p-XRF analyses that showed elevated tungsten (W) gold (Au) and yttrium (Y) in silica-rich breccia that exhibited epithermal quartz textures. The name “Highway” was coined to acknowledge the anomalously

high concentrations of

W,

Au and

Yin these breccias.

Figure 2.

Geological map of the Mitakoodi anticline showing locations of the Highway, Duck Creek and Lawler prospects.

Figure 2.

Geological map of the Mitakoodi anticline showing locations of the Highway, Duck Creek and Lawler prospects.

The silicic breccias and associated carbothermal veins, that contain elevated Au and tellurium Te have been traced for more than 20 km along the eastern limb of the Mitakoodi Anticline [

57,

58] (

Figure 2). They are interpreted to have crystallized from boiling silica and CO

2 - rich hydrothermal and carbothermal fluids at shallow crustal depths. These fluids accessed the axial plane shear zones of parasitic folds around the Mitakoodi anticline where they precipitated.

The Duck Creek porphyry system occurs at a deeper level of crustal exposure in the core of the Mitakoodi Anticline, west of the Highway epithermal mineralisation. Litho-geochemical data for drill core indicate that mineralisation occurs in a post-tectonic potassic suite that includes olivine websterite, pyroxenite, gabbro, leucogabbro, anorthosite and monzodiorite and monzonites. In view of the common association between potassic magmatism and large, high-grade Cu-Au porphyry deposits (Müller and Groves 2019), recognition of the involvement of post-tectonic potassic magmatism in the eastern NWMP has important implications for the resource potential of the Highway-Duck Creek discovery. The Highway-Duck Creek epithermal-porphyry mineralization post-dates the ~1650 Ma) thermotectonism in the Mount Isa Block.

The discovery was facilitated through application of a new exploration model for the Cloncurry region based on results reported by Collerson in [

42]. This model specifically addressed apparent deficiencies with the IOCG model that specifically focused on the role played by post-tectonic Williams Batholith granitoids, whose felsic compositions failed to explain the distinctive element association viz., Cu-Au-Ni-Co-Pt-Pd-Sc (±HREE+Y) and the superchondritic Nb/Ta recorded in the Highway-Duck Creek mineralisation. The model provided an alternative explanation for the spatial association and source of metals in iron-oxide-copper-gold (IOCG) and iron-sulphide-copper-gold (ISCG) mineralisation in the Cloncurry area cf., Skirrow [

59], that have recently been assigned to be members of a new clan of intracratonic ore deposits by Brauhart and Groves [

34]. By accommodating spatial and geochemical relationships of mineralisation, within a coherent narrative that is consistent with models for the geodynamic evolution of eastern margin of the North Australian Craton, the new model clearly provides a plausible exploration basis for future discoveries.

2.2. Geological Setting of the Mitakoodi Domain

The megascopic scale Mitakoodi anticline (

Figure 2) [

57,

58] and an associated west-verging thrust system, formed during the Isan Orogeny at ~ 1650 Ma [

57,

58,

60,

61]. The core of the Mitakoodi anticline is a region of low finite strain that preserves a varied sequence of Marraba Volcanic lithologies including the Bulonga Volcanics, the Cone Creek and the Timberoo Members. The Bulonga Volcanics are conformably overlain by interbedded mafic volcanics and fine clastic units of Marraba Volcanics and by a thick (up to 2000 m) succession of quartzo-feldspar arenite, termed the Mitakoodi Quartzite. The Mitakoodi Quartzite contains minor interbedded lenses of siltstone and metabasalt as well as a unit of thinly bedded tuff, near the top of the sequence.

The top of the quartzite contains a unit of porphyritic rhyolite which has been mapped for a strike length of >3 km. As rhyolite is a high viscosity magma, that forms lava domes, not extensive flows, the rhyolite sequence is possibly better interpreted as a pyroclastic ignimbrite sheet or tuff. A U-Pb SHRIMP zircon age of 1755 ± 4 Ma for the “rhyolite” [

58] is within error of the age of the felsic Bulonga volcanic unit dated by Neumann et al., [

62] in the core of the Mitakoodi anticline. The entire package of lithologies that crop out in the Mitakoodi Culmination represent a previously unrecognized intraplate suite, that was possibly deposited in a back-arc rift environment. Some mafic units are quite massive and most likely represent high-level ultramafic to mafic plutonic bodies.

The Mitakoodi Domain was subsequently intruded by phases of the Wimberu Granite member of the Eureka Supersuite of plutons within the Williams Batholith. The Wimberu Granite yields LA-ICP-MS zircon U/Pb ages of 1518 ± 4 and 1483 ± 4 Ma [

63]. This younger Williams - Naraku Batholith magmatism between ~1530 – 1490 Ma, resulted in the formation of a complex suite of granitoids ranging in composition from dioritic through monzonitic, syenitic to granitic compositions with A-type geochemical signatures. Highway lithologies intrude regionally extensive rhyodacitic and rhyolitic lithologies of the 1750±4 Ma Bulonga Volcanics [

62] in the core of the Mitakoodi anticlinorium (

Figure 2). This has been confirmed by laser ablation U- Pb geochronological data for xenotime and monazite from the Highway Breccia which yield ages of ~1530 Ma and ~1490 Ma respectively.

2.3. Field Relationships and Petrology

Highway system is characterised by dominantly mono-lithologic quartz crackle breccias containing angular clasts that are cemented in a metal-rich matrix (

Figure 3a-e). They contain chalcedonic siliceous vuggy veins, with characteristic epithermal textures, e.g., comb textured microcrystalline quartz, crustiform-colloform banded quartz and lattice textures (

Figure 3d & f). The distinctive epithermal lattice texture in

Figure 3f is interpreted to have formed by quartz replacing earlier deposited calcite in a hydrothermal system. Such textures are characteristic of low sulphidation, epithermal environments where boiling carbonate rich hydrothermal fluids culminated in the release of CO

2. Field and petrographic observations indicate that the breccias, the epithermal textured siliceous veins and the carbothermal veins and carbothermal lithologies (

Figure 3g) were deposited from carbonate-rich hot spring (travertine), some contain chalcedonic clasts (

Figure 3h).

In thin section, the epithermal lithologies exhibit very distinctive textures (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Examples include interlayered quartz comb texture in a carbonate matrix (

Figure 4a and

Figure 7b), a vein of epithermal quartz cutting propylitically altered gabbro (

Figure 4c & d), a fine grained siliceous brecciated unit cemented by veins of epithermal quartz (

Figure 4e and

Figure 7f), cross cutting carbothermal and siliceous epithermal veins that indicate the impact of several hydrothermal events in the area (

Figure 4g & h) and siliceous comb textures (

Figure 4i). Also shown is a reflected light is an image of a Highway epithermal lithology containing multiple grains of gold.

Photomicrographs of typical Highway carbonate- and quartz-bearing carbothermal lithologies are show in

Figure 5. Xenomorphic and idiomorphic grains of quartz typically exhibit slightly embayed grain boundaries that reflects effect of acid (HF?) corrosion (

Figure 5 a to d and 5 g, h & i). Some of the carbothermal units are tourmaline-bearing (

Figure 5 e & f) indicating that boron was an important component in the hydrothermal fluids.

Figure 3.

Highway Epithermal lithological variation (a to e & h) siliceous breccias showing embayed clasts of milky quartz, (f) rhombohedral carbonate pseudomorphed by epithermal silica, (g) carbothermal sinter and (h) embayed siliceous clast in a carbothermal matrix.

Figure 3.

Highway Epithermal lithological variation (a to e & h) siliceous breccias showing embayed clasts of milky quartz, (f) rhombohedral carbonate pseudomorphed by epithermal silica, (g) carbothermal sinter and (h) embayed siliceous clast in a carbothermal matrix.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of epithermal textures, (a & b) interlayered quartz comb texture in a carbonate matrix in plane and cross polarised light, (c & d) vein of epithermal quartz cutting gabbro that exhibits propylitic alteration in plane and cross polarised light, (e & f) fine grained siliceous brecciated unit cemented by veins of epithermal quartz in plane and cross polarised light, (g & h) carbothermal and siliceous epithermal veins showing evidence of several hydrothermal events in plane and cross polarised light,(i) classic epithermal siliceous comb textures in cross polarised light, (j) reflected light image showing grains of gold in Highway epithermal lithology.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of epithermal textures, (a & b) interlayered quartz comb texture in a carbonate matrix in plane and cross polarised light, (c & d) vein of epithermal quartz cutting gabbro that exhibits propylitic alteration in plane and cross polarised light, (e & f) fine grained siliceous brecciated unit cemented by veins of epithermal quartz in plane and cross polarised light, (g & h) carbothermal and siliceous epithermal veins showing evidence of several hydrothermal events in plane and cross polarised light,(i) classic epithermal siliceous comb textures in cross polarised light, (j) reflected light image showing grains of gold in Highway epithermal lithology.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of typical Highway epithermal lithologies in plane and cross polarised light, (a–d) and (g-i) carbothermal lithologies with xenomorphic and idiomorphic grains of quartz that show embayed grain boundaries caused by acid (HF?) corrosion, (e & f) tourmaline-bearing carbothermal lithology which shows the role of B in the fluid phase, (j) Back scattered electron image of Au and Bi tellurides in pyrite.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of typical Highway epithermal lithologies in plane and cross polarised light, (a–d) and (g-i) carbothermal lithologies with xenomorphic and idiomorphic grains of quartz that show embayed grain boundaries caused by acid (HF?) corrosion, (e & f) tourmaline-bearing carbothermal lithology which shows the role of B in the fluid phase, (j) Back scattered electron image of Au and Bi tellurides in pyrite.

Boron is a significant component of porphyry-related systems that also host epithermal deposits, and its occurrence is common vector indicating the presence of a deeper porphyry copper deposit.

Figure 5j shows a back scattered electron image pyrite containing inclusions of gold and bismuth telluride. Gold and bismuth tellurides are key components of some epithermal gold deposits, forming from hydrothermal fluids and often associated with alkaline or sub-alkaline magmatism [

64].

3.4. Duck Creek Mafic Intrusive Complex

Tholeiitic ferrogabbros, gabbronorites, leucogabbros and anorthosites are medium to fine grained, with intergranular to subophitic textures. A=bsence of deformational fabrics clearly indicates that the intrusions were emplace after thermotectonism in the NWMP (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of gabbro (a - d), leucogabbro (e & f) and anorthosite (g & h) from the tholeiitic ferro-mafic unit that intrudes the Bulonga Volcanics in plane and cross polarised light showing intergranular and sub-ophitic textures. These are clearly undeformed and are therefore interpreted to be post tectonic and therefore post-Isan orogeny.

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of gabbro (a - d), leucogabbro (e & f) and anorthosite (g & h) from the tholeiitic ferro-mafic unit that intrudes the Bulonga Volcanics in plane and cross polarised light showing intergranular and sub-ophitic textures. These are clearly undeformed and are therefore interpreted to be post tectonic and therefore post-Isan orogeny.

The fine grain size of these samples is interpreted to indicate that they represent the upper chilled margin of a much larger deeper intrusive complex. This is supported by the fact that they crop out as roof pendants within the Marraba Volcanics (

Figure 2). The intrusion contains lithologies that resembles lithologies in the plume generated Nain Plutonic Suite, Labrador, Canada [

65]. The lack of seismic anisotropy in the deep crust below the eastern margin of the North Australian Craton [

48,

49] shows the extensive nature of this mafic intrusive complex.

2.5. Alteration in the Highway - Duck Creek Mineral System

Marraba volcanics host lithologies, and members of the later ferrogabbro to monzogabbro suite all show the effect of penecontemporaneous pervasive alteration (

Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs in in plane and cross polarised light showing (a & b) phyllic alteration and (c – h) propylitic alteration.

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs in in plane and cross polarised light showing (a & b) phyllic alteration and (c – h) propylitic alteration.

The alteration assemblages overprint metamorphic microstructures in the Marraba volcanics and igneous textures in the ferrogabbro to monzogabbro suite. Typical alteration facies include:

(1) Phyllic alteration, is shown by the presence of white mica (sericite) and quartz together with chlorite, carbonate and tourmaline (

Figure 7a & b). This alteration is caused by hydrolysis due to interaction between high temperature, moderately acidic fluids with host protoliths. The presence of carbonate and tourmaline indicate that the hydrothermal fluids were CO

2 and boron bearing. Tourmaline is a common phase in both phyllic and propylitic alteration haloes associate with epithermal and porphyry Cu-Au mineral systems [

66]. Carbonate is also a common phase in phyllic alteration haloes and indicates that the alteration fluids have near neutral pH’s [

67].

(2) Propylitic alteration is shown by the presence of chlorite, epidote, carbonates (calcite), albite, and pyrite, often replacing original ferromagnesian minerals like biotite and amphibole (

Figure 7c to h). It is also a common feature along the margins of porphyry copper and associated epithermal precious metal deposits.

(3) Potassic alteration is shown by the presence of secondary biotite, K-feldspar (orthoclase), and sometimes muscovite or sericite. It forms by reaction between protoliths of different compositions with hot (420-500 °C) metal-rich fluids. Potassic alteration is commonly associated with sulphide mineralization, near the core of porphyry copper-gold systems.

3. Highway - Duck Creek Mineralisation

Figure 8 shows reflected light and back scattered electron images examples of pyrite and Au telluride (

Figure 8a), scheelite and wolframite (

Figure 8b, c and f), gold mineralisation (

Figure 8d & e) titanomagnetite and pyrite (

Figure 8g), titanomagnetite (

Figure 8h & i) in Highway epithermal lithologies.

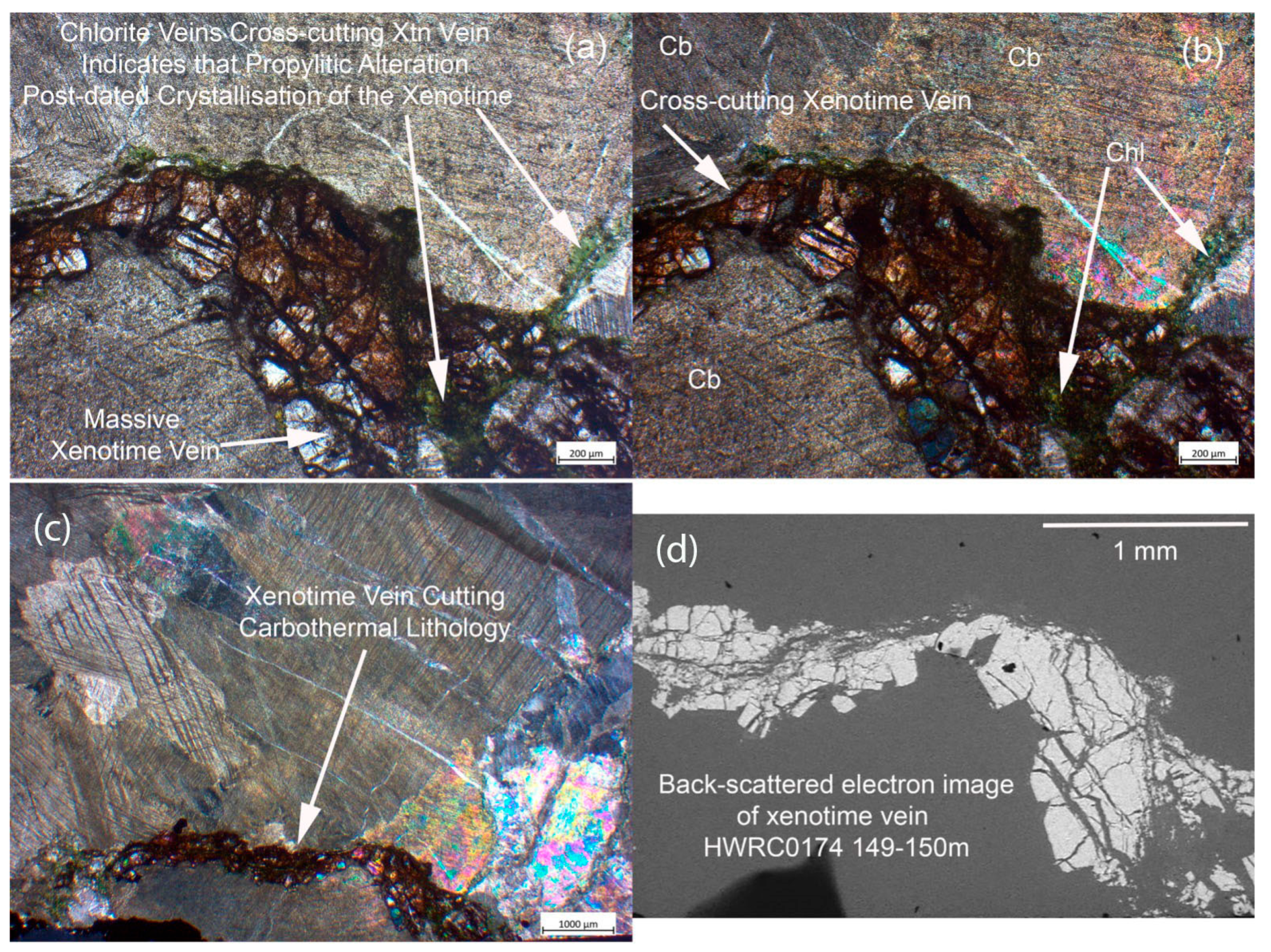

Rare earth elements in the Highway epithermal system occur in monazite and xenotime. As these phases occur in cross cutting veins (

Figure 9) this mineralisation was clearly of hydrothermal origin.

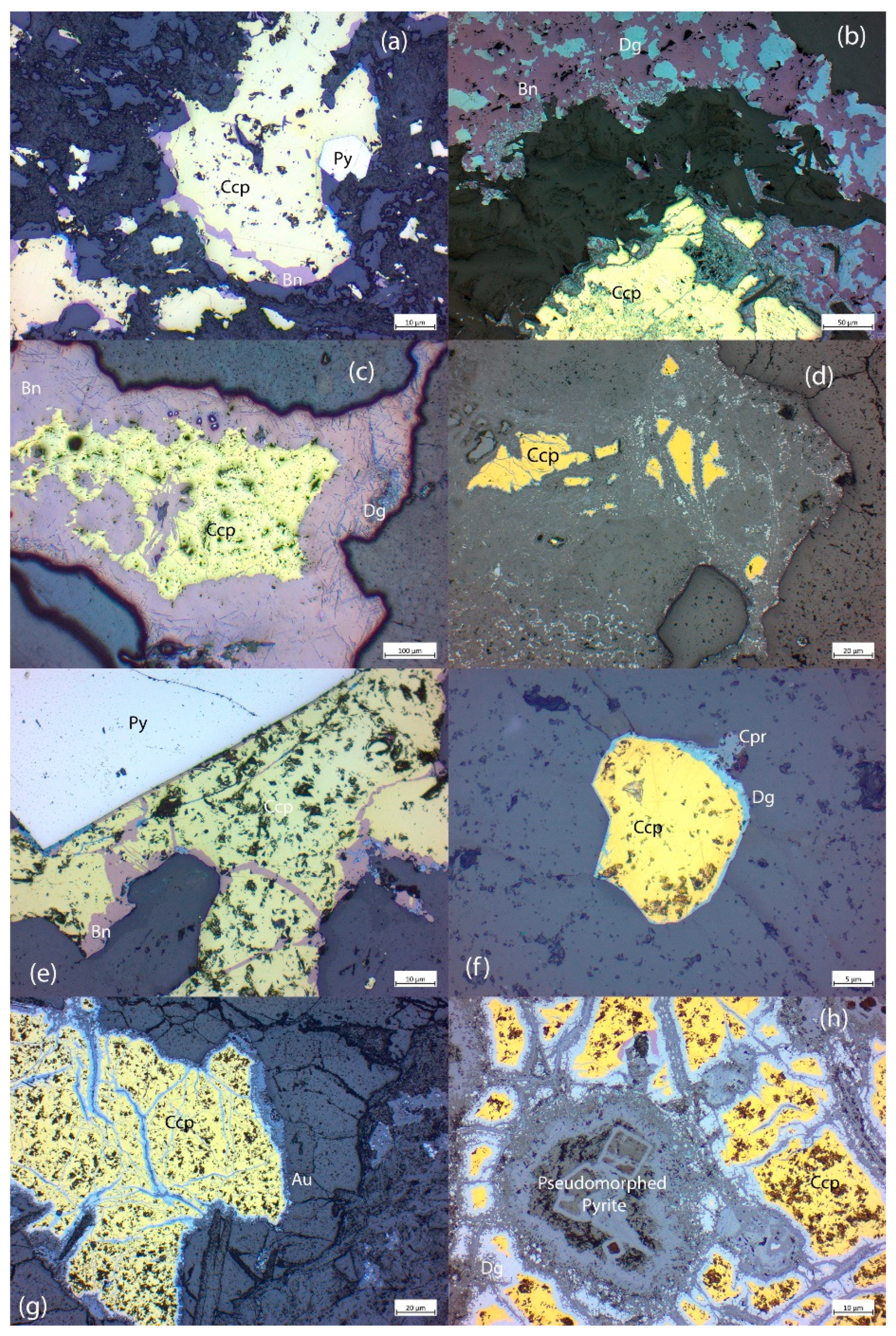

Textures and paragenetic relationships of Cu sulphides in the deeper Duck Creek mineral system are shown in

Figure 10. Samples are mainly from diamond drill core from the New Dollar deposit, which is located between Columbiad and Horseshoe (

Figure 11).

Sulphide paragenetic relationship show early formed crystallisation of euhedral pyrite and then subsequent crystallisation of chalcopyrite (

Figure 10a & e). In some samples the early formed pyrite is brecciated and cut by narrow veins of chalcopyrite. Chalcopyrite typically exhibits coronas of bornite which is interpreted to have formed by oxidation (

Figure 11b & c). Supergene alteration of chalcopyrite is shown by formation of digenite and covellite (

Figure 11d, f & g) (h) pyrite pseudomorphs surrounded by chalcopyrite with rims of digenite New Dollar (19m).

The presence of early euhedral pyrite and later chalcopyrite is a common paragenetic feature of many Cu-Au porphyry systems e.g., Cadia in N.S.W. The presence of early formed euhedral pyrite in porphyries is interpreted to indicate that it crystallised from a hydrothermal fluid [

68]. Bornite overgrowths on chalcopyrite are interpreted to have formed by hydrothermal alteration (

Figure 10b-h). Bornite shows the pervasive effect of supergene replacement by digenite, covellite and chalcocite. The presence of abundant interstitial chalcopyrite in the ferro-gabbroic to monzogabbroic suite indicates a close relationship to the porphyry mineralising event.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Samples from the Highway and Duck Creek were collected by KDC and by DW and geological staff employed by Transition Resources between 2018 and 2025.

4.2. Methods

The polished thin sections were prepared in the Queensland University of Technology lapidary facility. Petrographic studies were undertaken by KDC using a ZEISS Axio-scope 5 Polarizing Reflected/Transmitted Light Petrographic Microscope in the School of the Environment, at the University of Queensland. Mineral identifications were confirmed using a Hitachi TM3030 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) equipped with a Bruker Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) also in the School of the Environment at the University of Queensland.

Analytical data reported and discussed in this paper, were obtained using XRF, fusion ICPOES, fusion ICPMS and fire assay provided by Intertek, Perth and Townsville. Certified litho-geochemical standards were analysed with all sample submissions and a full QA/QC assessment for accuracy was undertaken.

The data includes representative major and trace element analyses of lithological groups identified in rock chip and drill core from the Highway epithermal system (

Table 1). These were selected from a data set of > 33,287 analyses of rock chips and both RC and DD drilling at Highway.

More than 17,915 rock chip, RC and diamond drill core samples from the Duck Creek area were also reviewed. Data reported in

Table 2 are average analyses of 1801 individual analyses from historic mines in the Duck Creek area. This data was obtained with support from a Queensland Department of Mines, through a Cooperative Exploration Initiative (CEI) grant to Transition Resources. Data from Mount Cobalt deposit are from Philpott [

69] and Collerson [

42]. Analyses of 1m composite samples from a 896 m long diamond core drilled by Chinalco at the Elaine Dorothy deposit near Mary Kathleen (MKED0036) are from Collerson [

46].

No generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) assistance was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Table 1.

Partial major element analyses for variably altered lithologies from the Highway epithermal system.

Table 1.

Partial major element analyses for variably altered lithologies from the Highway epithermal system.

| |

#1 |

#2 |

#3 |

#4 |

#5 |

#6 |

#7 |

#8 |

#9 |

#10 |

#11 |

#12 |

| Number of Analyses |

154 |

783 |

426 |

888 |

12 |

64 |

1045 |

722 |

47 |

435 |

15 |

163 |

| SiO2

|

51.71 |

52.86 |

53.49 |

50.51 |

59.84 |

58.37 |

60.69 |

61.91 |

57.35 |

58.02 |

73.87 |

70.66 |

| TiO2

|

0.40 |

0.81 |

0.64 |

1.55 |

0.47 |

0.67 |

0.59 |

0.49 |

0.44 |

0.23 |

0.30 |

0.26 |

| Al2O3

|

12.74 |

11.89 |

12.39 |

11.63 |

13.49 |

12.19 |

13.72 |

13.20 |

9.46 |

5.28 |

4.75 |

7.44 |

| Fe2O3

|

16.99 |

13.91 |

10.74 |

16.42 |

14.48 |

9.64 |

9.21 |

7.58 |

8.87 |

7.77 |

12.21 |

12.32 |

| MnO |

0.13 |

0.17 |

0.13 |

0.17 |

0.18 |

0.13 |

0.08 |

0.12 |

0.26 |

0.38 |

0.69 |

0.22 |

| MgO |

4.40 |

4.73 |

4.00 |

4.55 |

2.96 |

4.76 |

3.81 |

3.58 |

3.32 |

2.94 |

1.52 |

1.77 |

| CaO |

2.12 |

6.50 |

4.65 |

6.02 |

1.25 |

6.55 |

3.48 |

5.71 |

13.97 |

20.46 |

1.33 |

2.11 |

| Na2O |

1.01 |

1.62 |

1.40 |

2.01 |

0.84 |

1.28 |

2.24 |

2.10 |

0.94 |

0.40 |

0.65 |

0.33 |

| K2O |

2.23 |

2.27 |

2.37 |

1.38 |

3.18 |

3.25 |

3.01 |

2.15 |

2.24 |

1.37 |

1.56 |

1.73 |

| P2O5

|

0.27 |

0.24 |

0.19 |

0.26 |

0.31 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.16 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

| LOI |

8.00 |

5.00 |

10.00 |

5.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

| Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Li |

18.3 |

13.7 |

15.1 |

13.2 |

10.8 |

5.9 |

16.0 |

13.0 |

10.5 |

7.0 |

14.2 |

8.6 |

| Sc |

35 |

33 |

24 |

38 |

36 |

24 |

18 |

17 |

19 |

14 |

23 |

25 |

| V |

359 |

322 |

208 |

356 |

378 |

193 |

142 |

127 |

172 |

108 |

151 |

203 |

| Cr |

74 |

64 |

66 |

49 |

78 |

86 |

67 |

57 |

51 |

28 |

48 |

55 |

| Co |

126 |

73 |

57 |

78 |

75 |

40 |

34 |

28 |

60 |

237 |

229 |

170 |

| Ni |

55 |

47 |

42 |

41 |

50 |

48 |

42 |

37 |

37 |

38 |

44 |

43 |

| Cu |

53 |

94 |

73 |

413 |

30 |

39 |

35 |

29 |

34 |

86 |

38 |

22 |

| Zn |

26 |

21 |

28 |

37 |

22 |

26 |

25 |

12 |

31 |

12 |

10 |

21 |

| Ga |

22 |

21 |

19 |

22 |

26 |

19 |

20 |

20 |

16 |

11 |

9 |

14 |

| Ge |

1.33 |

1.27 |

1.44 |

0.73 |

1.14 |

3.88 |

1.74 |

1.28 |

1.63 |

0.85 |

1.30 |

1.17 |

| As |

4.8 |

5.6 |

3.8 |

7.0 |

2.9 |

4.0 |

2.7 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

6.5 |

7.3 |

4.7 |

| Se |

1.97 |

1.98 |

2.37 |

1.53 |

0.94 |

2.06 |

1.57 |

1.85 |

1.58 |

7.33 |

9.05 |

2.94 |

| Rb |

100 |

101 |

101 |

72 |

133 |

143 |

122 |

93 |

94 |

57 |

81 |

76 |

| Sr |

34 |

28 |

25 |

62 |

21 |

43 |

31 |

28 |

37 |

33 |

15 |

19 |

| Y |

47 |

38 |

35 |

50 |

46 |

32 |

31 |

29 |

35 |

72 |

244 |

112 |

| Zr |

168 |

170 |

201 |

161 |

185 |

174 |

214 |

224 |

160 |

109 |

65 |

112 |

| Nb |

13.3 |

15.0 |

12.9 |

11.7 |

13.5 |

11.6 |

13.9 |

13.9 |

12.6 |

12.1 |

5.8 |

12.7 |

| Mo |

2.25 |

4.19 |

3.01 |

2.73 |

3.83 |

3.26 |

2.69 |

3.13 |

3.09 |

13.07 |

5.31 |

4.63 |

| Ag |

0.22 |

0.17 |

0.29 |

0.32 |

0.07 |

0.45 |

0.35 |

0.15 |

0.37 |

0.45 |

0.34 |

0.28 |

| Sn |

3.91 |

4.13 |

3.92 |

2.87 |

6.57 |

3.13 |

4.00 |

4.34 |

3.92 |

4.35 |

2.13 |

4.59 |

| Sb |

0.96 |

0.53 |

1.66 |

0.73 |

0.76 |

5.32 |

1.50 |

0.70 |

3.40 |

0.83 |

0.53 |

0.58 |

| Te |

19.20 |

3.06 |

4.79 |

5.04 |

1.03 |

8.41 |

5.94 |

2.03 |

4.81 |

13.28 |

25.15 |

28.14 |

| Ba |

300 |

361 |

362 |

201 |

503 |

337 |

547 |

301 |

348 |

208 |

160 |

294 |

| La |

38.9 |

36.5 |

43.1 |

28.5 |

40.5 |

32.4 |

47.5 |

51.7 |

47.7 |

178.1 |

43.8 |

57.7 |

| Ce |

78.2 |

76.7 |

94.6 |

65.3 |

81.8 |

69.3 |

97.1 |

102.3 |

94.3 |

309.7 |

92.6 |

112.3 |

| Pr |

9.6 |

9.2 |

11.1 |

8.1 |

10.0 |

8.3 |

11.1 |

11.8 |

11.0 |

38.6 |

11.6 |

13.3 |

| Nd |

38.6 |

36.6 |

41.7 |

33.1 |

40.0 |

31.8 |

41.3 |

44.1 |

41.6 |

146.0 |

50.9 |

54.1 |

| Sm |

8.76 |

8.16 |

8.96 |

8.36 |

8.86 |

6.60 |

7.98 |

8.59 |

9.39 |

32.26 |

18.39 |

13.72 |

| Eu |

2.63 |

2.28 |

2.34 |

2.47 |

2.55 |

1.56 |

1.71 |

1.95 |

2.48 |

9.10 |

8.38 |

4.77 |

| Gd |

9.96 |

8.61 |

8.47 |

10.10 |

9.69 |

6.33 |

7.10 |

7.71 |

8.54 |

27.95 |

37.66 |

19.57 |

| Tb |

1.62 |

1.38 |

1.33 |

1.77 |

1.55 |

0.99 |

1.05 |

1.14 |

1.28 |

3.74 |

8.32 |

3.72 |

| Dy |

10.09 |

8.45 |

7.99 |

11.80 |

9.54 |

5.94 |

6.20 |

6.58 |

7.38 |

19.69 |

57.51 |

24.91 |

| Ho |

1.98 |

1.68 |

1.52 |

2.39 |

1.86 |

1.19 |

1.21 |

1.26 |

1.40 |

3.45 |

11.73 |

4.97 |

| Er |

5.50 |

4.64 |

4.24 |

6.50 |

5.35 |

3.40 |

3.44 |

3.48 |

3.83 |

8.92 |

30.50 |

13.29 |

| Tm |

0.78 |

0.65 |

0.59 |

0.90 |

0.79 |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.50 |

0.53 |

1.22 |

4.13 |

1.87 |

| Yb |

4.87 |

3.98 |

3.76 |

5.50 |

4.97 |

3.11 |

3.14 |

3.12 |

3.26 |

7.42 |

23.81 |

11.04 |

| Lu |

0.69 |

0.59 |

0.54 |

0.77 |

0.74 |

0.46 |

0.48 |

0.48 |

0.48 |

0.93 |

2.83 |

1.40 |

| Hf |

4.57 |

4.48 |

5.43 |

4.46 |

5.14 |

4.72 |

5.79 |

5.94 |

4.29 |

2.83 |

1.81 |

3.02 |

| Ta |

0.85 |

0.86 |

0.97 |

0.70 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

1.10 |

1.08 |

0.90 |

0.82 |

0.33 |

0.70 |

| W |

135 |

169 |

211 |

25 |

172 |

25 |

92 |

147 |

70 |

227 |

715 |

615 |

| Au g/t |

1.03 |

0.37 |

0.19 |

0.23 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

0.16 |

0.25 |

0.22 |

3.46 |

6.14 |

3.28 |

| Tl |

0.69 |

0.24 |

2.45 |

0.24 |

0.31 |

9.78 |

2.59 |

0.77 |

5.10 |

1.31 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

| Pb |

2.27 |

2.28 |

2.40 |

3.03 |

1.23 |

2.11 |

2.12 |

1.87 |

2.23 |

5.34 |

4.52 |

3.21 |

| Bi |

11.71 |

1.60 |

1.11 |

1.23 |

0.32 |

2.66 |

1.34 |

0.72 |

2.01 |

11.55 |

21.88 |

24.08 |

| Th |

6.79 |

6.33 |

12.35 |

5.37 |

7.78 |

17.26 |

15.99 |

14.99 |

11.68 |

5.99 |

4.72 |

5.24 |

| U |

4.46 |

3.94 |

4.74 |

2.12 |

5.90 |

8.31 |

6.07 |

5.81 |

6.42 |

10.37 |

7.06 |

5.17 |

| S wt% |

0.15 |

0.37 |

0.22 |

0.29 |

N.D. |

0.06 |

0.13 |

0.24 |

0.22 |

1.35 |

1.01 |

0.47 |

| Y/Ho |

23.88 |

22.91 |

22.82 |

20.78 |

24.96 |

26.69 |

25.30 |

22.75 |

24.98 |

20.89 |

20.79 |

22.50 |

| Zr/Hf |

36.84 |

38.08 |

36.98 |

36.08 |

35.92 |

36.93 |

36.90 |

37.79 |

37.20 |

38.59 |

35.83 |

37.06 |

| Nb/Ta |

15.69 |

17.38 |

13.30 |

16.79 |

13.93 |

12.22 |

12.57 |

12.93 |

13.99 |

14.63 |

17.44 |

18.18 |

| Nb/Y |

0.28 |

0.39 |

0.37 |

0.24 |

0.29 |

0.37 |

0.45 |

0.49 |

0.36 |

0.17 |

0.02 |

0.11 |

| La/Yb |

7.99 |

9.17 |

11.45 |

5.18 |

8.15 |

10.41 |

15.11 |

16.56 |

14.63 |

24.00 |

1.84 |

5.22 |

| Molar Cu/Au |

159 |

786 |

1198 |

5571 |

784 |

4051 |

680 |

357 |

475 |

77 |

19 |

21 |

Table 2.

Major Element Analyses and Trace Element Data for Lithologies from the Duck Creek Area with Comparative data from Mount Cobalt and Mary Kathleen.

Table 2.

Major Element Analyses and Trace Element Data for Lithologies from the Duck Creek Area with Comparative data from Mount Cobalt and Mary Kathleen.

| |

Columbiad |

Comet |

Dulce |

Easter Gift. |

Eva |

Forget-Me-Not |

Hideaway |

Horseshoe |

| No. Analyses |

n=130 |

n=44 |

n=61 |

n=4 |

n=13 |

n=157 |

n=66 |

n=481 |

| SIO2

|

62.96 |

64.16 |

59.16 |

69.09 |

63.87 |

62.90 |

63.20 |

62.27 |

| TiO2

|

0.90 |

1.48 |

0.74 |

0.68 |

0.43 |

0.64 |

1.24 |

0.93 |

| Al2O3

|

10.33 |

10.30 |

12.55 |

10.94 |

6.96 |

10.84 |

9.42 |

10.56 |

| Fe2O3

|

16.39 |

15.58 |

15.60 |

11.51 |

20.51 |

15.05 |

18.65 |

15.34 |

| MnO |

0.09 |

0.32 |

0.13 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

| MgO |

4.76 |

2.30 |

5.83 |

3.78 |

3.43 |

6.11 |

2.32 |

5.45 |

| CaO |

1.46 |

3.28 |

2.86 |

0.43 |

3.31 |

1.49 |

2.75 |

2.60 |

| Na2O |

2.14 |

1.28 |

2.03 |

2.52 |

0.74 |

1.74 |

1.07 |

1.83 |

| K2O |

0.79 |

1.16 |

1.00 |

0.84 |

0.57 |

1.05 |

1.13 |

0.78 |

| P2O5

|

0.18 |

0.14 |

0.10 |

0.12 |

0.08 |

0.11 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

| SUM |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Fe/(Fe+Mg) |

0.63 |

0.77 |

0.57 |

0.61 |

0.75 |

0.55 |

0.80 |

0.59 |

| Na2O+K2O |

2.93 |

2.44 |

3.03 |

3.36 |

1.30 |

2.79 |

2.20 |

2.61 |

| Trace Elements ppm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Li |

10.8 |

10.6 |

17.6 |

13.1 |

10.1 |

21.0 |

10.1 |

16.3 |

| Be |

1.65 |

1.26 |

0.94 |

0.85 |

0.66 |

1.10 |

1.00 |

1.05 |

| Sc |

21 |

30 |

25 |

19 |

18 |

24 |

24 |

26 |

| V |

224 |

329 |

216 |

213 |

274 |

215 |

352 |

244 |

| Cr |

52 |

54 |

92 |

43 |

70 |

81 |

68 |

55 |

| Co |

208 |

97 |

159 |

100 |

204 |

114 |

59 |

164 |

| Ni |

64 |

46 |

93 |

45 |

108 |

85 |

102 |

67 |

| Cu |

704 |

2544 |

5789 |

11596 |

19414 |

4645 |

1727 |

6382 |

| Cu wt.% |

0.07 |

0.25 |

0.58 |

1.16 |

1.94 |

0.46 |

0.17 |

0.64 |

| Zn |

28 |

27 |

37 |

22 |

29 |

36 |

41 |

34 |

| Ga |

20 |

15 |

22 |

14 |

14 |

21 |

15 |

19 |

| Rb |

37 |

50 |

47 |

31 |

26 |

74 |

54 |

30 |

| Sr |

30 |

58 |

50 |

16 |

24 |

36 |

60 |

40 |

| Y |

23 |

29 |

19 |

36 |

14 |

15 |

23 |

20 |

| Zr |

103 |

120 |

103 |

126 |

35 |

68 |

102 |

85 |

| Nb |

7.0 |

8.2 |

6.5 |

4.4 |

1.8 |

4.4 |

8.1 |

5.5 |

| Mo |

1.99 |

0.64 |

2.96 |

0.45 |

1.38 |

1.56 |

1.11 |

2.89 |

| Pd |

2.92 |

3.24 |

7.05 |

2.83 |

20.93 |

6.42 |

7.42 |

8.89 |

| Ag |

0.15 |

0.34 |

0.35 |

0.33 |

0.98 |

0.44 |

0.90 |

0.40 |

| Sn |

1.81 |

1.84 |

1.43 |

1.80 |

2.46 |

1.71 |

1.71 |

1.74 |

| Sb |

26.3 |

0.63 |

0.37 |

0.40 |

0.50 |

0.43 |

2.39 |

0.38 |

| Cs |

1.45 |

1.52 |

1.46 |

0.79 |

1.05 |

2.76 |

1.28 |

1.23 |

| Ba |

176 |

283 |

239 |

118 |

179 |

217 |

191 |

177 |

| La |

19.5 |

20.2 |

19.9 |

13.2 |

6.2 |

10.7 |

16.6 |

14.2 |

| Ce |

39.2 |

46.2 |

41.7 |

27.3 |

13.0 |

22.1 |

36.0 |

30.1 |

| Pr |

4.6 |

5.2 |

5.0 |

3.6 |

1.8 |

2.7 |

4.3 |

3.7 |

| Nd |

18.3 |

21.5 |

19.6 |

15.6 |

7.7 |

11.1 |

17.4 |

15.3 |

| Sm |

4.02 |

5.00 |

4.05 |

4.41 |

1.95 |

2.56 |

4.08 |

3.50 |

| Eu |

1.03 |

1.46 |

0.90 |

1.15 |

0.48 |

0.62 |

1.08 |

0.83 |

| Gd |

4.26 |

5.55 |

3.82 |

5.50 |

2.20 |

2.71 |

4.31 |

3.65 |

| Tb |

0.70 |

0.85 |

0.57 |

0.91 |

0.36 |

0.44 |

0.68 |

0.59 |

| Dy |

4.30 |

5.43 |

3.62 |

6.11 |

2.40 |

2.90 |

4.33 |

3.82 |

| Ho |

0.87 |

1.11 |

0.72 |

1.27 |

0.51 |

0.60 |

0.88 |

0.78 |

| Er |

2.55 |

3.57 |

2.13 |

4.15 |

1.64 |

1.78 |

2.66 |

2.29 |

| Tm |

0.36 |

0.52 |

0.31 |

0.63 |

0.24 |

0.27 |

0.38 |

0.34 |

| Yb |

2.30 |

3.47 |

2.04 |

4.25 |

1.59 |

1.65 |

2.45 |

2.09 |

| Lu |

0.34 |

0.56 |

0.31 |

0.66 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.37 |

0.33 |

| Hf |

3.03 |

3.18 |

2.83 |

3.42 |

0.95 |

1.98 |

2.77 |

2.55 |

| Ta |

0.53 |

0.60 |

0.48 |

0.34 |

0.12 |

0.32 |

0.59 |

0.42 |

| W |

3.31 |

12.78 |

1.91 |

4.38 |

5.30 |

3.52 |

1.69 |

3.83 |

| Pt |

3.66 |

3.44 |

6.14 |

1.40 |

12.68 |

6.46 |

3.94 |

7.41 |

| Au ppm |

0.02 |

0.12 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

2.36 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

| Tl |

0.16 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

0.10 |

0.12 |

0.29 |

0.24 |

0.13 |

| Pb |

4.12 |

4.24 |

2.16 |

19.33 |

8.24 |

1.85 |

40.20 |

2.02 |

| Bi |

0.85 |

1.00 |

1.19 |

0.41 |

3.85 |

1.33 |

4.19 |

0.68 |

| Th |

5.49 |

6.14 |

6.66 |

5.89 |

1.10 |

3.39 |

5.53 |

3.62 |

| U |

2.27 |

1.97 |

2.13 |

4.56 |

3.44 |

2.37 |

1.55 |

1.99 |

| TREE ppm |

102 |

121 |

105 |

89 |

40 |

60 |

96 |

81 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| logAg/Au |

0.91 |

0.46 |

0.98 |

0.90 |

-0.38 |

0.78 |

1.12 |

0.82 |

| Molar Cu/Au |

122967 |

66077 |

495563 |

866068 |

25471 |

195163 |

78261 |

326323 |

| Y/Ho |

26.29 |

26.48 |

26.65 |

28.42 |

27.87 |

25.52 |

26.09 |

25.35 |

| Zr/Hf |

33.90 |

37.63 |

36.46 |

36.87 |

36.44 |

34.48 |

36.73 |

33.53 |

| Nb/Ta |

13.41 |

13.84 |

13.50 |

13.02 |

14.52 |

13.84 |

13.62 |

13.12 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nb/Y |

0.31 |

0.28 |

0.34 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.29 |

0.35 |

0.28 |

| Nb+Y |

29.95 |

37.70 |

25.59 |

40.46 |

16.09 |

19.84 |

31.12 |

25.26 |

Table 2.

Major Element Analyses and Trace Element Data for Lithologies from the Duck Creek Area with Comparative data from Mount Cobalt and Mary Kathleen (Continued).

Table 2.

Major Element Analyses and Trace Element Data for Lithologies from the Duck Creek Area with Comparative data from Mount Cobalt and Mary Kathleen (Continued).

| |

Junction |

Micawber |

Mountain Maid |

New Dollar |

Ready Rhino |

Success |

Mount

Cobalt |

Mary

Kathleen* |

| Elements wt% |

n=52 |

n=67 |

n=216 |

n=168 |

n=145 |

n=196 |

n=3 |

n=640 |

| SIO2

|

55.62 |

60.80 |

64.04 |

61.79 |

61.31 |

65.01 |

46.33 |

46.74 |

| TiO2

|

0.94 |

0.64 |

1.06 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

1.18 |

1.51 |

4.78 |

| Al2O3

|

14.01 |

12.44 |

9.94 |

10.80 |

11.61 |

10.08 |

13.45 |

0.18 |

| Fe2O3

|

15.37 |

13.91 |

15.53 |

15.70 |

14.38 |

16.98 |

17.74 |

19.02 |

| MnO |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

0.11 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.32 |

| MgO |

6.50 |

5.66 |

4.28 |

6.08 |

6.69 |

3.21 |

9.20 |

3.99 |

| CaO |

3.07 |

2.65 |

1.85 |

1.69 |

2.04 |

1.34 |

5.05 |

23.65 |

| Na2O |

3.00 |

2.30 |

1.71 |

1.43 |

1.53 |

0.98 |

1.88 |

0.65 |

| K2O |

1.20 |

1.38 |

1.29 |

1.43 |

1.33 |

0.93 |

4.55 |

0.26 |

| P2O5

|

0.17 |

0.11 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

0.15 |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.42 |

| SUM |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Fe/(Fe+Mg) |

0.54 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.73 |

0.49 |

0.85 |

| Na2O+K2O |

4.21 |

3.68 |

3.00 |

2.86 |

2.86 |

1.92 |

4.68 |

0.90 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Li |

19.7 |

17.2 |

14.3 |

25.9 |

29.1 |

15.7 |

26.7 |

6.89 |

| Be |

1.48 |

1.10 |

1.63 |

1.18 |

1.25 |

1.31 |

|

1.71 |

| Sc |

32 |

26 |

23 |

29 |

31 |

27 |

52 |

3.34 |

| V |

250 |

201 |

246 |

263 |

265 |

329 |

573 |

79.71 |

| Cr |

75 |

63 |

54 |

74 |

66 |

66 |

113 |

9.18 |

| Co |

60 |

124 |

156 |

80 |

76 |

208 |

148 |

104 |

| Ni |

67 |

101 |

62 |

70 |

80 |

67 |

147 |

203 |

| Cu |

187 |

2197 |

2932 |

4796 |

2774 |

4820 |

184 |

2039 |

| Cu wt.% |

0.02 |

0.22 |

0.29 |

0.48 |

0.28 |

0.48 |

0.02 |

0.20 |

| Zn |

42 |

38 |

33 |

32 |

38 |

25 |

34 |

23.44 |

| Ga |

22 |

21 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

17 |

36 |

15.45 |

| Rb |

55 |

79 |

73 |

65 |

61 |

43 |

423 |

11.16 |

| Sr |

69 |

51 |

39 |

29 |

48 |

33 |

59 |

18.90 |

| Y |

25 |

18 |

25 |

18 |

22 |

23 |

32 |

38.78 |

| Zr |

125 |

97 |

117 |

75 |

85 |

118 |

84 |

46.29 |

| Nb |

8.2 |

6.0 |

8.1 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

7.2 |

7.7 |

9.70 |

| Mo |

1.51 |

1.45 |

2.07 |

1.29 |

1.33 |

0.92 |

1.50 |

1.83 |

| Pd |

9.13 |

7.24 |

2.79 |

7.07 |

8.22 |

4.44 |

1.80 |

|

| Ag |

0.18 |

0.16 |

0.32 |

0.29 |

0.28 |

0.42 |

1.67 |

0.11 |

| Sn |

2.12 |

1.40 |

1.82 |

1.33 |

1.43 |

2.39 |

0.08 |

45.72 |

| Sb |

0.57 |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.40 |

0.48 |

0.53 |

0.43 |

0.33 |

| Cs |

2.89 |

4.06 |

2.66 |

3.39 |

2.68 |

1.18 |

13.78 |

0.36 |

| Ba |

293 |

292 |

217 |

189 |

234 |

200 |

461 |

52.6 |

| La |

34.1 |

17.5 |

20.4 |

13.6 |

14.2 |

22.9 |

152.6 |

159.5 |

| Ce |

66.6 |

36.4 |

43.1 |

27.4 |

29.4 |

46.0 |

270.4 |

303.3 |

| Pr |

7.7 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

3.3 |

3.7 |

5.5 |

30.9 |

29.5 |

| Nd |

29.7 |

17.4 |

20.8 |

13.7 |

15.4 |

21.9 |

119.4 |

101.24 |

| Sm |

5.85 |

3.71 |

4.58 |

3.18 |

3.67 |

4.83 |

25.89 |

16.39 |

| Eu |

1.63 |

0.82 |

1.16 |

0.82 |

0.94 |

1.35 |

2.65 |

3.49 |

| Gd |

5.38 |

3.68 |

4.80 |

3.44 |

3.97 |

4.78 |

19.38 |

11.69 |

| Tb |

0.79 |

0.55 |

0.79 |

0.55 |

0.63 |

0.73 |

2.22 |

1.48 |

| Dy |

4.83 |

3.47 |

4.79 |

3.50 |

4.07 |

4.51 |

9.58 |

7.28 |

| Ho |

0.95 |

0.68 |

0.97 |

0.71 |

0.82 |

0.89 |

1.44 |

1.28 |

| Er |

2.75 |

2.04 |

2.84 |

2.10 |

2.43 |

2.62 |

3.35 |

3.22 |

| Tm |

0.40 |

0.29 |

0.41 |

0.30 |

0.34 |

0.37 |

0.43 |

0.43 |

| Yb |

2.54 |

1.95 |

2.63 |

1.93 |

2.24 |

2.46 |

2.39 |

2.59 |

| Lu |

0.38 |

0.31 |

0.39 |

0.29 |

0.34 |

0.37 |

0.31 |

0.39 |

| Hf |

3.47 |

2.68 |

3.25 |

2.13 |

2.37 |

3.20 |

2.30 |

1.09 |

| Ta |

0.61 |

0.45 |

0.58 |

0.31 |

0.36 |

0.54 |

0.23 |

0.26 |

| W |

3.34 |

2.04 |

3.27 |

3.58 |

4.26 |

3.10 |

1.00 |

13.76 |

| Pt |

8.43 |

5.52 |

2.76 |

6.66 |

7.52 |

3.97 |

1.50 |

|

| Au ppm |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.15 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

| Tl |

0.23 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.19 |

0.23 |

0.18 |

0.92 |

0.05 |

| Pb |

1.92 |

1.96 |

2.19 |

2.42 |

2.13 |

4.26 |

|

9.80 |

| Bi |

0.25 |

0.58 |

3.94 |

1.26 |

0.93 |

2.16 |

0.06 |

2.81 |

| Th |

8.03 |

6.52 |

5.79 |

2.37 |

3.75 |

6.02 |

1.22 |

55.81 |

| U |

2.43 |

2.23 |

2.57 |

2.06 |

1.93 |

2.17 |

0.86 |

17.95 |

| TREE ppm |

164 |

93 |

113 |

75 |

82 |

119 |

641 |

642 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| logAg/Au |

1.62 |

0.74 |

1.06 |

0.94 |

1.06 |

0.45 |

2.44 |

0.41 |

| Molar Cu/Au |

133087 |

230183 |

333822 |

438564 |

345827 |

99015 |

94882 |

143049 |

| Y/Ho |

26.19 |

26.69 |

26.36 |

25.83 |

26.45 |

25.89 |

22.03 |

30.39 |

| Zr/Hf |

36.14 |

36.17 |

36.06 |

35.38 |

36.09 |

36.87 |

36.52 |

42.38 |

| Nb/Ta |

13.30 |

13.52 |

14.01 |

14.08 |

14.38 |

13.38 |

32.86 |

37.20 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nb/Y |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.32 |

0.24 |

0.24 |

0.31 |

0.24 |

0.25 |

| Nb+Y |

33.09 |

24.30 |

33.57 |

22.69 |

26.90 |

30.21 |

39.47 |

48.48 |

5. Results

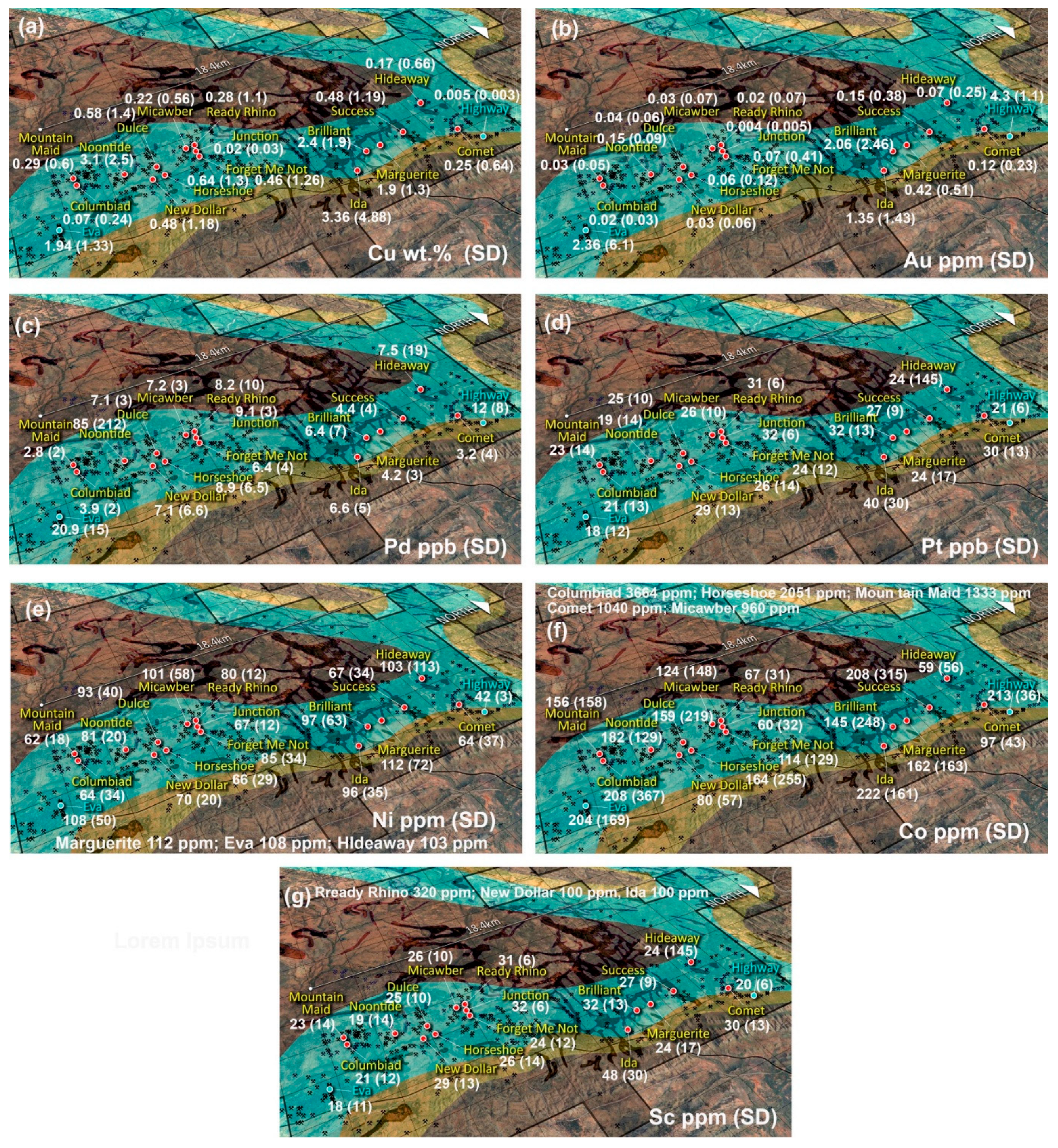

Figure 11 shows the areal extent and Cu, Au, Pd, Pt, Ni, Co and Sc anomalism in different deposits listed in

Table 2, from in Highway-Duck Creek area. As this elemental anomalism extends for a strike length of more than 18.4 km, it is clear that a very large mineral system lies west and at depth below the Highway epithermal domain.

The region is currently under active resource definition by Transition Resources. The Highway epithermal mineralisation exhibits significant concentrations of precious and critical metals (

Table 1) e.g., Au intersections of up to 11m @ 9.58 g/t, 7m @ 9.02 g/t Au and 2m @ 41.2 g/t Au. The system is also heavy rare earth element rich with up to 157 ppm Dy

2O

3 and 23 ppm Tb

4O

7. Other key critical elements in the Highway system include WO

3 and Sc

2O

3 that range up to 1793 ppm and 64 ppm respectively.

The current global gold resource for the extreme northern segment of the Highway epithermal corridor Highway a depth of 125m is 1.2 Mt @ 3.1 g/t Au and 1600 ppm WO3, plus significant HREEs, Co and Sc. Although limited resource drilling has been undertaken in the Duck Creek porphyry system, assays from a small segment of the exploration target indicate an inferred JORC resource of 5.44Mt @ 1.45% Cu, 0.11 g/t Au and 158 ppm Co. The current global resource for Duck Creek porphyry is estimated to contain 6.5 Mt @1.57%, Cu 0.12 g/t Au.

5.1. Metallogenic Affinity

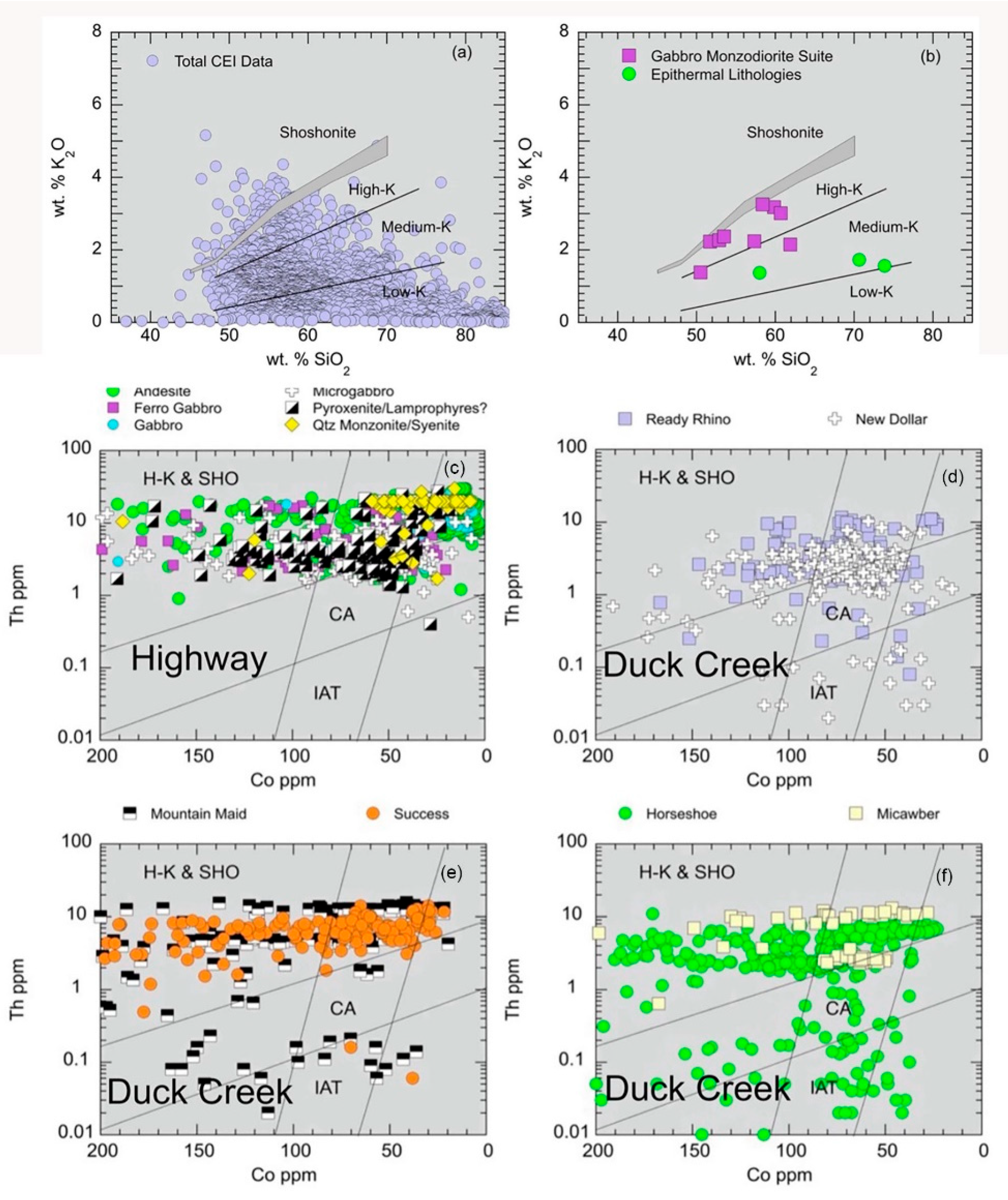

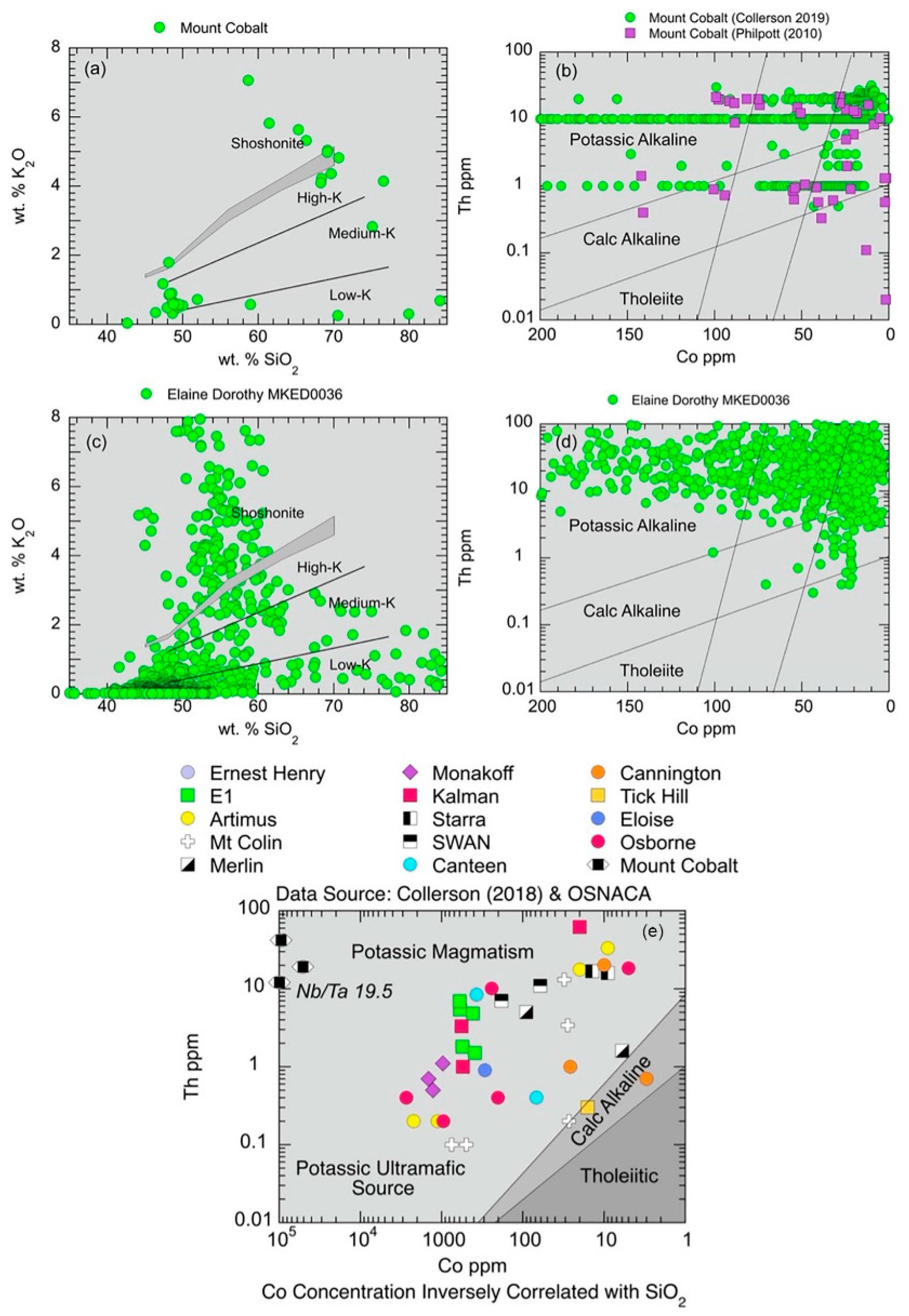

5.1.1. K2O-SiO2 and Th-Co Discrimination Plots

CEI data for the Duck Creek deposits and the mean compositions of the Highway lithologies are plotted in the K

2O and SiO

2 discrimination projection of Peccerillo and Taylor [

70] to understand the petrological affinity of the igneous source responsible for the formation of the Highway-Duck Creek mineral system. The Duck Creek data show a broad range of compositions extending from shoshonite to low K calc alkaline (

Figure 12a).

The mean data for the different Highway lithology assemblages in

Figure 12b, is more coherent and falls within the field from high K to medium K. The spectrum of variation shown by K

2O is interpreted to largely be caused by loss of K

2O during the phyllic and propylitic alteration event that permeated the system following crystallisation of the primary igneous lithologies [

72]. In addition, as these lithologies show phyllic or propylitic alteration, it is likely that all have either lost or gained Si.

To circumvent the effect of loss or gain of K during post-crystallisation alteration, Hastie et al. [

73] suggested using Th as a proxy for K and Co as a proxy for Si and proposed a discrimination projection that was more robust to alteration.

Figure 12c to f shows Th and Co data for Highway and Duck Creek lithologies. They indicate that the dominant metal source at Highway and Duck Creek was an alkaline (high K) igneous suit [42,45,69,82e, although samples from some Duck Creek deposits, e.g., Ready Rhino, New Dollar, Mountain Maid, and Horseshoe, exhibit a secondary calc alkaline to tholeiitic petrologic vector.

These divergent trends are interpreted to indicate the presence two petrological/mineralising systems in the Duck Creek area. First, a subduction related porphyry mineralising event with a magmatic arc source, that formed during subduction and back arc extension. This was followed by a second metallogenic event, after collision and closure of an ocean basin east of the North Australian Craton. It is likely that a palaeo-slab tear was accreted to North Australian Craton lithosphere at this time thereby providing a window that facilitated the ingress of a plume magmas into the mantle wedge and subcontinental lithosphere. The post-tectonic tholeiitic to alkaline suite thus provided the metal source for formation of a later porphyry system with high-level epithermal carapace. In this regard, the identification of a potassic magmatic source has significant implications for the metal endowment, because some of the largest porphyry systems are hosted by K-rich magmas [

74]. As continental collision zone porphyry deposits are typically hosted by potassic and ultrapotassic magmas [

7,

54,

75] evidence for presence of such a magmatic source for the Highway Duck Creek system provides additional support for the continental collision zone porphyry model.

Identification of a potassic magmatic source for the Highway - Duck Creek mineral system also has important regional implications. For example, this potassic signature is also seen at Mount Cobalt (

Figure 13 a & b) and at the Elaine Dorothy deposit near Mary Kathleen (

Figure 13 c & d). This signature is also prominent in many of the “IOCG” deposits in the Cloncurry area (

Figure 13e).

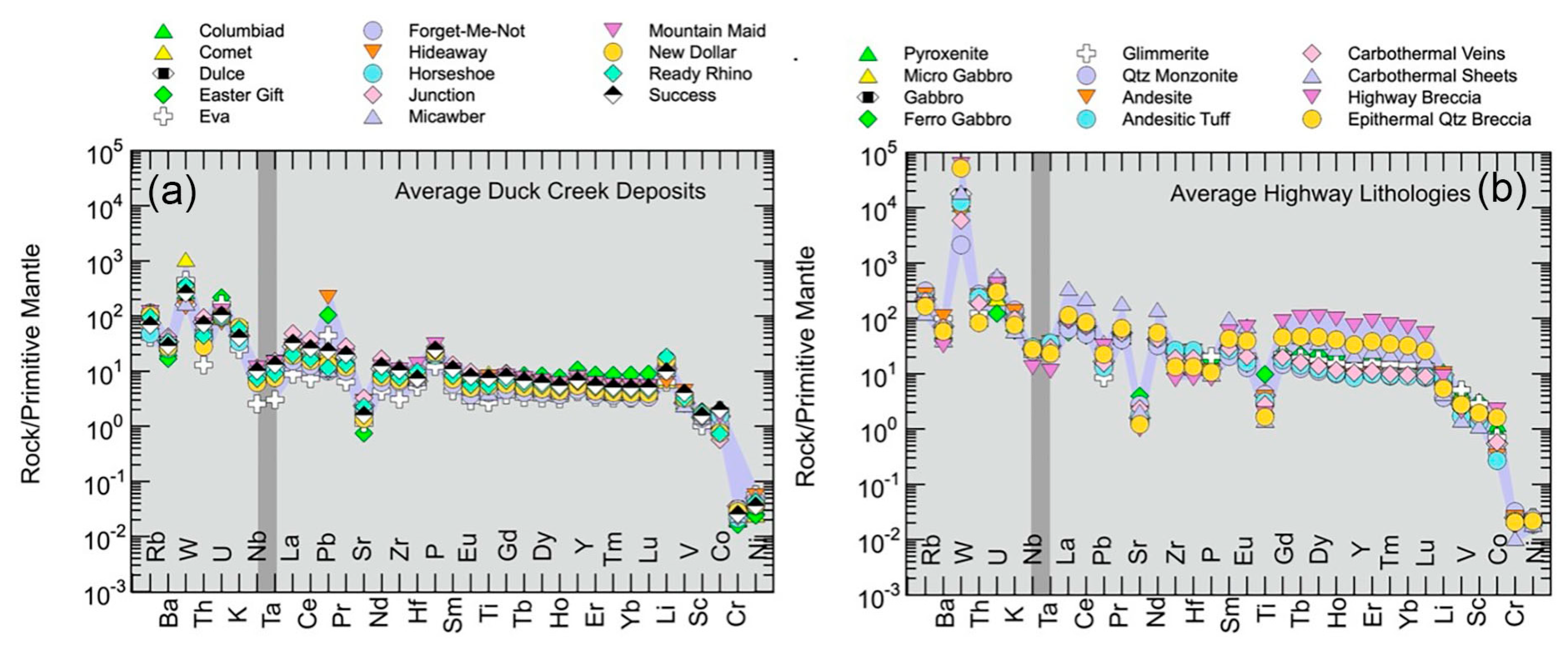

5.1.2. Multi-element Geochemical Variation

Primitive mantle-normalized multi-element plots, where elements are arranged in order of increasing compatibility are an effective way to compare geochemical data for different protoliths. The primitive mantle values used for element normalization are either from McDonough and Sun [

76] or Lyubetskaya and Korenaga [

77]. Analyses of the Duck Creek deposits and the different Highway lithologies are compared in

Figure 14a and b. The two systems exhibit broadly uniform shaped patterns, with positive spikes in W, U, Pb, P and Li and negative spikes in Ba, Th, Nb, Ta and Sr. The pronounced depletion in Sr is a common feature seen at both Duck Creek and at Highway. It could reflect the fact that early fractionation of a Ca-Sr component (possibly a carbonatite) has occurred during evolution of the source magma. Alternatively, the widespread Sr depletion seen at Highway and Duck Creek could be alteration induced [

78,

79,

80]. Highway also shows a pronounced negative Ti spike, which is absent at Duck Creek suggests the fractionation of a Ti-bearing mineral into the gabbro – monzogabbro intrusion that underlies the Mitakoodi anticline.

In addition to the significant level of W enrichment seen in all Highway lithologies, they are also significantly enriched (50 to 100x PM levels) in the rare earth elements (REEs). These include the high value heavy rare earth elements, Dysprosium (Dy) and Terbium (Tb) that are hosted by xenotime and monazite. For example, average compositions are 8.32 ppm Tb and 57.51 ppm Dy breccia (n= 15), 3.74 ppm Tb and 19.69 ppm Dy carbothermal (n=435) l and 3.72 ppm Tb and 24.91 ppm Dy epithermal quartz breccia (n=163). These lithologies are also significantly enriched in Au, averaging 6.14 g/t (breccia), 3.46g/t (carbothermal sheets) and 3.28 g/t (quartz breccia).

Although, the level of W enrichment in all Highway lithologies is significantly greater than at Duck Creek, the overall similarity in pattern, with relatively consistent immobile-incompatible element ratios, results in parallel profiles at Duck Creek and Highway. This supports the model that they are related systems and that the metals in the Highway epithermal system were delivered by fluids derived from the deeper Duck Creek system.

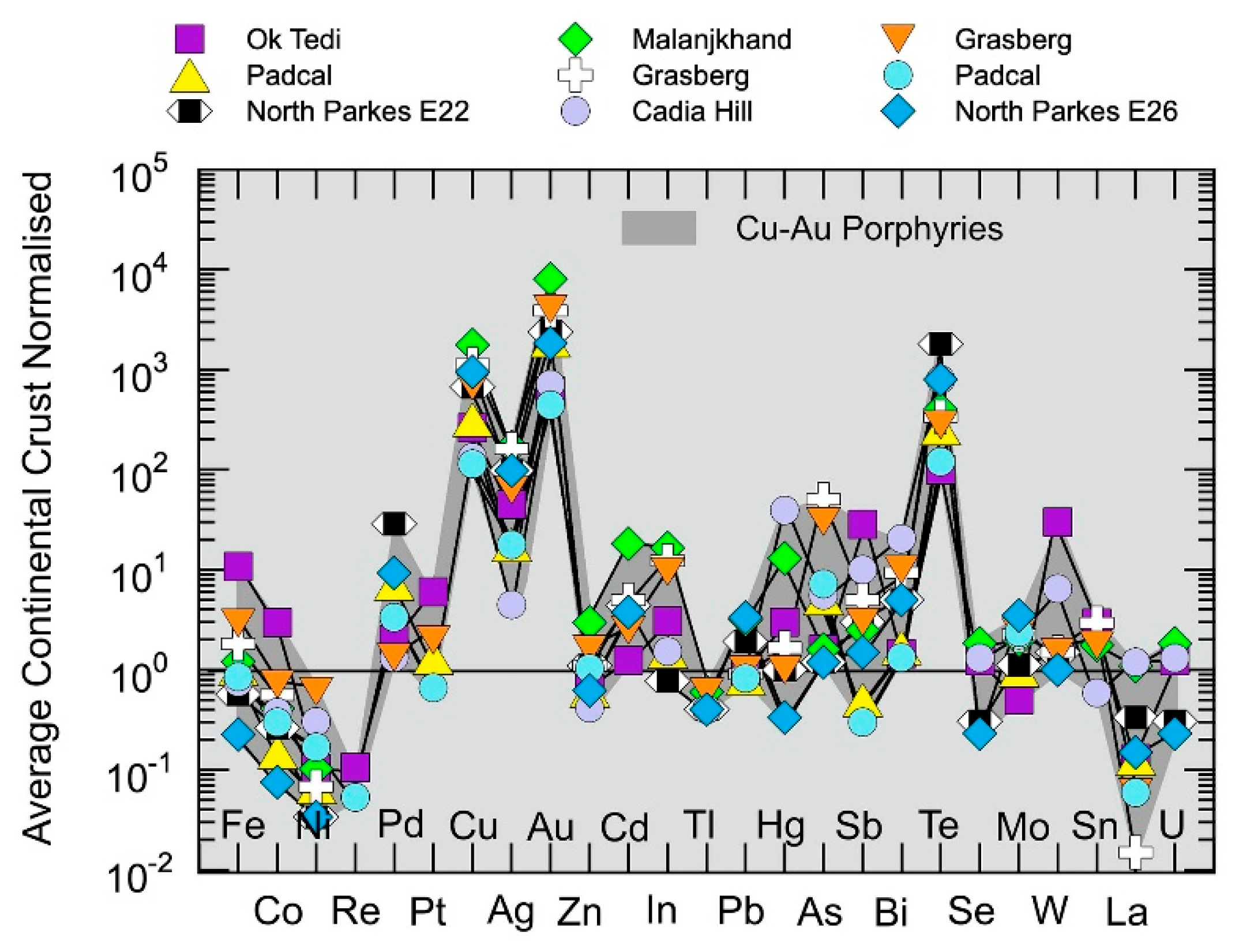

5.1.3. Multi-element Geochemical Variation

To discriminate between different mineral deposit styles, with specific reference to the IOCG class of deposit, Brauhart and Groves [

34] proposed the use of multielement plots normalised to average crustal abundance [

81]. This projection highlights the granitophile La and U enrichments seen in both IOCG and some porphyry systems (

Figure 15).

The projection also highlights the enrichment in ‘ultramafic’ suite of elements, such as the transition elements (Co-Ni) and the platinum group metals (Pd-Pt). In these plots, the presence of spikes in these elements in a mineral system geochemical profile, indicates the role of a mantle continental collision zone porphyry system rather than a crustal component in the metallogenic process.

The principal focus of the Brauhart and Groves [

34] publication was to compare chemical variability of Australian intracratonic deposits, classified as IOCG and ISCG systems. However, in some locations, e.g., Chile [

32] and the Gawler [

31] Cu-Au porphyry deposits occur close to IOCG systems. Cu-Au porphyry deposits also occur in cratonic settings [

7] especially, in collisional cratonic environments, like the eastern margin of the North Australian Craton [

52]. Thus, to provide, a more representative platform for comparing between IOCG and Cu-Au porphyry systems, crustal abundance multi-element normalised plots for representative Cu-Au porphyry deposits, using data from the OSNACA database [

82] are shown, in

Figure 15. Porphyry systems exhibit a downward trend from Fe to Ni, but they also show positive spikes in Pd, Cu, Au, Te and W.

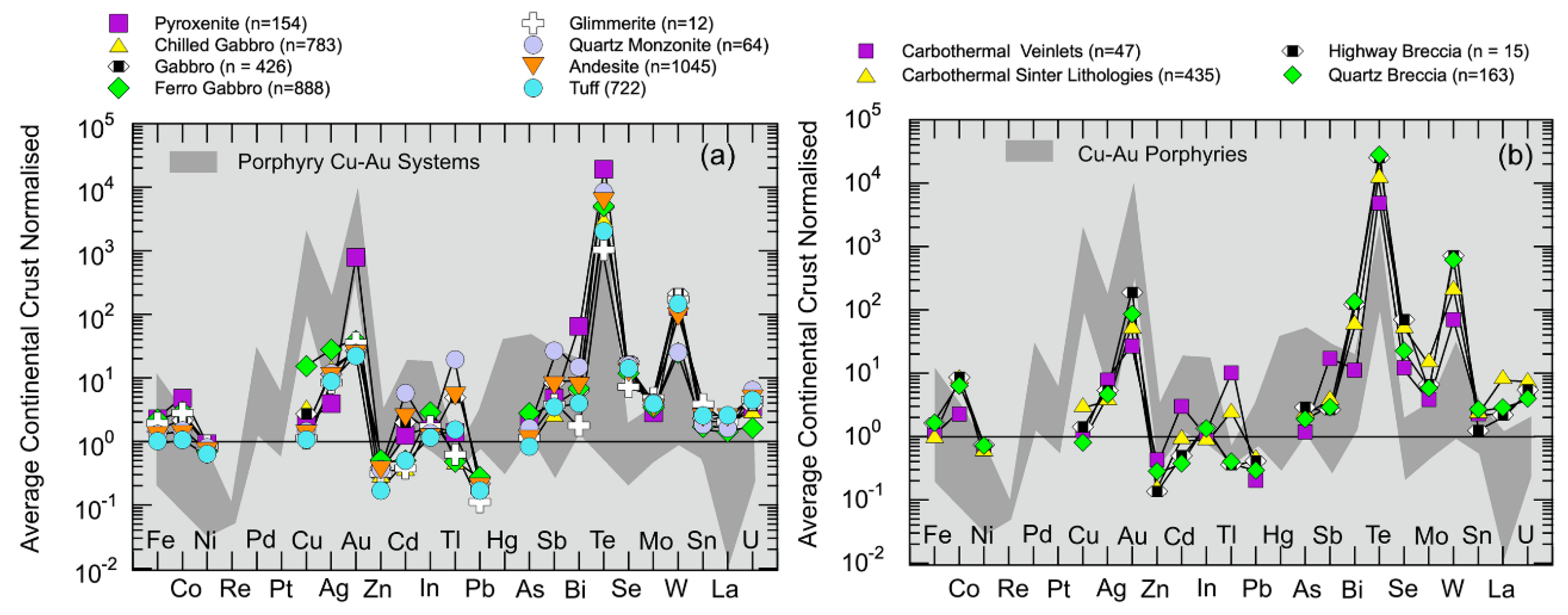

Crust normalised data for the Highway mineral system lithologies are shown in

Figure 16 a & b. The Highway patterns are remarkably similar, to the Cu-Au porphyry field with prominent spikes in Au, Te and W. It is also enriched in Co, La and U, relative to Cu-Au porphyries that are hosted by K-rich igneous lithologies. The depletion at Highway reflects the fact that Cu has largely been sequestered by sulphide precipitation into the underlying Duck Creek porphyry system. Such depletion in Cu is a typical feature of epithermal mineralisation above porphyry systems [

83].

Crustal abundance multi-element normalised plots for several Duck Creek deposits, i.e., Success, Mountain Maid, Horseshoe, Dulce, Eva, Furnace, Glory Hole, Comet and Daisey are shown in

Figure 17.

Samples exhibit topologies that either resemble porphyries with a downward trend from Fe to Ni and the positive spikes in Cu, Au, Te and W, or they resemble the Highway sub-pattern with positive spikes in Co as well as in Cu, Au, Te and W. For example, samples from Success (a & b), Mountain Maid (c & d), Horseshoe (e & f), Dulce (g & h) as well as at Eva, Furnace, Glory Hole, Comet and Daisy (i & j). The presence of these different patterns suggests the possible involvement of two metal sources in the metallogenic evolution of the Duck Creek system, viz., a subduction generated component, generating patterns like the porphyry field, and an ultramafic to mafic component most likely associated with the post-tectonic tholeiitic to alkalic plume component.

5.1.4. Metal Source Constraints from Te Cu Ni Systematics

Post- subduction geodynamic settings are characterised by significant mantle-to-crust fluxes of metals and volatiles. Te is a tracer of this flux, and of the magmatic and hydrothermal processes that drive the flux. Post-subduction magmato-hydrothermal systems are Te enriched, and it exhibits both incompatible and chalcophile behaviour. At magmatic temperatures (> 1000 °C), Te has chalcophile behaviour like Au, Cu and the PGEs. Thus, at magmatic temperatures, Te enters sulphide melts, which fractionate and forming Pt–Pd-telluride melts at ~900 °C and then Pt–Pd-telluride minerals at <400 °C [

84]. However, under hydrothermal conditions, at ~300 °C Te is mobilised as chloride complexes [

85], as polytellurides in S- and CO

2-rich fluids [

86] and as telluride–bismuthide melts [

87]. Thus, Te is an ideal tracer of both magmatic and hydrothermal processes providing important information regarding mantle-to-crust fluxes of metals showing spatial and genetic links between deep magmatic Ni–Cu–PGE–Au–Te mineral systems and shallower, alkali-enriched porphyry–epithermal Cu–Au-(PGE-Te) deposits [

83].

As a result of this behaviour, Holwell et al., [

83] demonstrated that Ni, Cu and Te systematics are effective vectors to resolve petrogenetic process and metallogenic sources.

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 show Cu, Ni and Te systematics for representative samples from Highway and from several Duck Creek deposits. These figures also show compositional fields of porphyry, epithermal, carbonatite, magmatic Cu-Ni-PGE and IOCG mineralisation.

Figure 18 a & b shows the compositional variability of individual Highway lithologies in Cu-Te and Ni-Te space. They lie within the epithermal field and in Cu-Te space within the Cu-Au porphyry field. Analyses of diamond drill hole samples from Duck Creek at a depth of >100m (

Figure 18 c & d) show an even more prominent compositional difference between the volatile dominated Highway system and sulphide dominated Duck Creek systems.

Figure 18 e & f show data for NWMP deposits that are classified as IOCG systems [

82].

The projection also highlights the enrichment in ‘ultramafic’ suite of elements, such as the transition elements (Co-Ni) and the platinum group metals (Pd-Pt). In these plots, the presence of spikes in these elements in a mineral system geochemical profile, indicates the role of a mantle-derived rather than a crustal component in the metallogenic process.

The principal focus of the Brauhart and Groves [

34] publication was to compare chemical variability of Australian intracratonic deposits, classified as IOCG and ISCG systems. However, in some locations, e.g., Chile [

32] and the Gawler [

31] Cu-Au porphyry deposits occur close to IOCG systems. Cu-Au porphyry deposits also occur in cratonic settings [

7] especially, in collisional cratonic environments, like the eastern margin of the North Australian Craton [

52]. Thus, to provide, a more representative platform for comparing between IOCG and Cu-Au porphyry systems, crustal abundance multi-element normalised plots for representative Cu-Au porphyry deposits, using data from the OSNACA database [

82] are shown, is shown in

Figure 15. Porphyry systems exhibit a downward trend from Fe to Ni. But they also show positive spikes in Pd, Cu, Au, Te and W.

Covariation between Ni/Te and Cu/Te (

Figure 19) showing a clear discrimination between epithermal and porphyry systems, with the Te-rich Highway lithologies plotting in the epithermal field along a Cu/Ni ratio vector of ~1 and Success, Hideaway, Chinaman and Eva showing the effect of Cu enrichment and plotting within the porphyry field.

5.1.5. Chalcophile Element and Highly Siderophile Element Systematics

Chalcophile element fertility or the chalcophile metal abundance and the availability of sulphur during source magma evolution, is a critical factor required to enable the formation of porphyry Cu ± Au deposits. Some mineralized porphyry systems are known to contain hydrothermal Pd and Pt [

14], showing that hydrothermal fluids can mobilize Pd and Pt and in rare cases, porphyry Cu deposits can contain up to 2400 ppb Pd (e.g., Skouries Cu porphyries, Greece; [

13]). Park et al., [

88] have shown that the platinum group elements (PGEs) can be used as a tracer for chalcophile element fertility during magma evolution

Recent studies on PG) geochemistry of subvolcanic rocks associated with porphyry Cu ± Au deposits [

89,

90,

91] have suggested that the relative timing of fluid and sulfide saturation plays an important role in the formation of porphyry Cu ± Au deposits. The PGEs are used in preference to Cu and Au for two reasons. First, their partition coefficients in immiscible sulfide melts are one to two orders of magnitude higher than those of Cu and Au respectively [

92]. Second, because they are appreciably less affected by alteration than Cu and Au, they are more likely to preserve original igneous geochemistry [

93,

94]. The relative abundances of Cu and Pd porphyry systems are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21.

Figure 20 shows covariation between Cu against Pd in several major porphyries Cu and Au-Cu deposits. Although Cu varies by several orders-of-magnitude in Bingham Canyon and Cadia Hill it does not correlate with increase in Pd as might be expected if Pd was an important component in the hydrothermal fluid. This indicates that the abundance of Pd is controlled by the chemistry of the porphyry host magma.

Samples from the Duck Creek system all plot with the Cu-Au porphyry field In

Figure 20b. Many of these are significantly enriched in Pd, in fact, several have similar Pd contents to the PGE rich Skouries Cu-Au (Pt, Pd, Te) porphyry [

87].

This is also shown in

Figure 21, which compares Pd with Cu/Pd and Pd/MgO with Pd/Pt ratios.