1. Introduction

In 2008, Euromoney observed that “one of the puzzles of Islamic finance is how Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation, has been so utterly left behind in its development” (Wright, 2008). This comment remains strikingly relevant, particularly with respect to Islamic mutual funds (IMFs), a segment that has expanded rapidly at the global level over the past years with Assets under Management (AUM) growing by more than 300 percent between 2012 and 2022 (CIBAFI, 2022). Despite this growth, Indonesia accounts for only around 3% of the global Islamic fund industry’s AUM (Euromoney, 2022). A comparison of AUM distribution across major Muslim-majority markets further underscores Indonesia’s potential: its share remains far below those of Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, even though Indonesia has a larger population of Muslims and a higher Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (

Table 1).

In Malaysia, the net asset value of IMFs rose from RM 9.76 billion in 2004 to RM 127 billion (approximately $30 billion) in 2025 (Securities Commission, 2025). This remarkable growth is closely linked to Malaysia’s strategic initiatives to position itself as a global hub for Islamic capital markets, supported by a national agenda aimed at achieving full parity between Islamic and conventional finance by 2030. To support this goal, the government introduced several incentives, including the “Islamic First” policy, which prioritizes Islamic products over conventional ones for new customers of Investment Management Companies (IMCs) and banks. Additionally, the government introduced several liberalization measures, including allowing IMFs to invest up to 100% of their assets overseas, easing shareholding restrictions to permit full foreign ownership of IMCs, and enhancing access to institutional financing, such as start-up capital from the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) (Jamaludin, 2012).

In Saudi Arabia, IMFs were introduced in the late 1990s following the success of several fund launches in Malaysia and the United States. Subsequently, Saudi Arabia has become one of the largest markets for these funds (Benjelloun & Abdullah, 2009). The IMF segment is primarily dominated by IMCs affiliated with commercial banks, which were the early entrants in the market. The top five players control over 80% of the market share in the mutual funds space (Sackor, 2018). Unlike Malaysia, where equity-based funds dominate, Saudi Arabia’s IMF segment is primarily driven by money market funds. However, like Malaysia, the growth has been substantial, with Shariah-compliant AUM increasing from $12 billion in 2013 (Sandwick, 2013) to $32.2 billion in 2023 (Argaam, 2023).

In Indonesia, the IMF segment was launched in 1996 (Khorana et al., 2005) with 25 funds and a total AUM of $297.3 million. Since then, the segment has experienced significant growth. Key regulatory developments began in 2001 when Dewan Syariah Nasional – Majelis Ulama Indonesia (the Indonesian Islamic institution responsible for formulating Shariah guidelines and fatwas, also known as DSN-MUI) issued Fatwa No. 20, providing guidelines for the implementation of investments in Shariah-compliant mutual funds. Today, the IMF segment is regulated by the Financial Services Authority (OJK), specifically the Directorate of Sharia Capital Markets. The segment saw substantial growth in 2016, when the government allowed IMCs to invest up to 100% of their funds’ assets in offshore Shariah-compliant securities. This regulatory change resulted in a near doubling of AUM, from IDR 15 trillion in 2016 to IDR 28 trillion (approximately $1.7 billion) in 2017 (Indrakusuma, 2020). Currently, the total AUM of IMFs is around $3.4 billion (Abdul Malik, 2025) and over 100 IMCs are licensed by the OJK, though only about 30 offer IMFs. Among these, the top ten IMCs control more than 50% of IMFs’ AUM (Abdul Malik, 2025). Despite this growth, IMFs still face several challenges, including limited Islamic financial literacy, insufficient product knowledge (Yusfiarto et al., 2023; Masrizal et al., 2024), and an inconsistent legal framework for issuing Shariah-compliant securities which limits the number of issuances and the associated market (Euromoney, 2022).

This study investigates the factors playing a role in the development and growth of IMFs in Indonesia. It explores the barriers that hinder investor participation in IMFs as well as the catalysts that could enhance their adoption. A qualitative research approach is employed, primarily through interviews with executives from IMCs and regulatory bodies. IMC executives maintain frequent interactions with investors and possess a deep understanding of their needs and concerns. Similarly, regulators work closely with IMCs and issuers and are well-positioned to identify the challenges IMCs face in developing and marketing IMFs to potential investors and the barriers that constrain the issuance of Shariah-compliant securities.

This study aims to generate actionable recommendations that support IMCs in strengthening their strategic decision-making, particularly with respect to fund design, distribution, and marketing. By improving these functions, the research seeks to assist IMCs in broadening their investor base and increasing their AUM. Beyond supporting IMCs, the findings also inform recommendations for policymakers, regulators, and financial advisors in areas such as regulatory harmonization, enhanced market access, improved Islamic financial literacy, tax-related considerations, and addressing the concerns of corporate securities issuers. Ultimately, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by offering a deeper understanding of the factors that shape the development and growth of IMFs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Previous Studies

In the past two decades, numerous studies examined IMFs, focusing on three primary areas: funds’ design, performance, and the factors that influence their adoption. Regarding funds’ design, Indonesian IMFs are regulated by National Sharia Council, which mandates that these funds must operate in accordance with Islamic Shariah principles. Reza (2024) identified three key principles essential for managing IMFs: (i) investments must be restricted to Shariah-compliant securities as defined by capital market laws; (ii) a cleansing process must be implemented to remove any income that does not align with Shariah principles; and (iii) a Shariah Supervisory Board must be established to oversee the fund’s compliance with Shariah guidelines.

Due to the requirement to invest exclusively in Shariah-compliant securities and the relatively limited pool of eligible assets, Islamic funds often exhibit greater similarity in their investment strategies compared with their conventional counterparts (Uddin et al., 2019). Such constraints may limit potential returns, given that some prohibited sectors, such as tobacco and gambling, have historically generated strong performance (Han & Onishchenko, 2022; Blitz & Swinkels, 2023).

In terms of performance, academic debates on the performance of IMFs relatively to conventional funds remain mixed. Some studies suggested that IMFs often underperform conventional peers due to sectoral exclusions and limited diversification (Bashir & Wan Nawang, 2011; Hassan et al., 2020; Mansor et al., 2020). However, multiple studies show that IMFs display lower correlation with broader market movements (Arif et al., 2022) and exhibit higher relative performance during periods of financial turmoil such as the 2008 global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic owing to their focus on low-debt, high-liquidity companies (Lesser & Walkshäusl, 2018; Mansor et al., 2019; Mirza et al., 2022; Ishak et al., 2022). This resilience is commonly attributed to the relative outperformance of sukuk and Shariah-compliant equities over conventional fixed-income and equity instruments during episodes of financial stress (Hasan et al., 2022; Chowdhury et al., 2022). Additionally, some other studies have reported no significant differences in performance between Islamic and conventional funds (Boo et al., 2017; Reddy et al., 2017), highlighting the ongoing debate and suggesting that IMF performance may depend on market conditions and fund characteristics.

In terms of IMFs adoption, the literature consistently identifies Islamic financial literacy as a key influencing factor. This one can be defined as the level of knowledge, awareness, and skill an individual has to be able to understand the fundamentals of Islamic financial information and services and make appropriate Islamic financing decisions (Antara et al., 2016). It plays a positive and significant role in IMFs adoption (Yusuff et al., 2017; Aziz & Kassim, 2021; Amin et al., 2022). Additionally, Investor’s religiosity which can be defined as a belief in the presence of God and obedience of the rules defined by God (McDaniel & Burnett, 1990) is another significant adoption factor (Mahdzan et al., 2017; Yusuff et al., 2017; Hasnat et al., 2024). Finally, funds’ performance is found to be a significant factor in multiple studies (Bakar et al., 2015; Mohammed Kamil et al., 2018; Nurul ‘Izzati, 2019; Atta & Marzuki, 2019; Aziz & Kassim, 2021).

In the Indonesian context, Pradana (2022) attributes the slow adoption of IMFs to several factors, including limited public knowledge and trust, lack of government support, and regulatory challenges surrounding Islamic investments. Although Iswanaji (2018) focused on the broader Islamic financial sector rather than IMFs, it identified three key impediments: the absence of favorable government policies and regulations, a shortage of qualified human resources, and a lack of awareness about Islamic finance, even within the Muslim community. Yusfiarto et al. (2023) found that Islamic financial literacy is relatively low in Indonesia, and that financial knowledge positively influence the intention to invest in Islamic capital market instruments. Al Fathan and Arundina (2019) highlighted supply limitations in the sukuk market, noting that this issue hampers the development of Islamic banking. Furthermore, Purbaningrum et al. (2024) found mixed public perceptions regarding Indonesia’s Islamic capital market, with many questioning whether products labeled as “Shariah-compliant” truly adhere to Halal and Shariah principles. They emphasized the need for clearer policies that distinguish Shariah-compliant investments from conventional ones, alongside the importance of enhancing public literacy regarding Shariah-compliant financial products.

2.2. Gap in Previous Studies

Although a substantial body of literature examines IMFs and their adoption in Malaysia, research on IMFs in Indonesia remains fragmented and characterized by several notable gaps. First, the majority of existing studies in the Indonesian context have primarily focused either on fund performance and performance-related determinants (Robiyanto et al., 2019; Pratama et al., 2021; Rahman & Qoyum, 2022; Adnan, 2023) or on the role of IMFs in supporting national economic development (Al Fathan & Arundina, 2019; Rofik et al., 2025). In contrast, limited scholarly attention has been devoted to understanding the factors that influence the mass adoption of IMFs among Indonesian investors.

Second, while prior research has examined the effects of individual determinants - such as Islamic financial literacy, market access, funds’ returns, and market depth - there is a lack of qualitative studies that simultaneously involve multiple stakeholder groups, including IMCs and regulators. Moreover, few studies adopt a unified or systemic analytical framework capable of capturing the interactions among these factors and explaining how they collectively shape IMF adoption dynamics.

Third, IMFs in Indonesia remain at an early stage of market development and are increasingly exposed to competition from alternative Shariah-compliant investment instruments. These include government retail sukuk, Islamic crowdfunding platforms, and Islamic exchange-traded funds (i-ETFs) listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (such as the Premier ETF Syariah JII) as well as from emerging asset classes such as cryptocurrencies. This evolving competitive landscape further underscores the need for research that examines adoption barriers and competitive positioning within Indonesia’s broader Islamic investment ecosystem.

The objectives of this study are threefold. First, the study seeks to identify the key barriers that hinder the widespread adoption of IMFs from both the supply side - namely, the availability, depth, and competitiveness of IMF offerings - and the demand side, which relates to investors’ awareness, consideration, and uptake of these products. In addition, the study explores how these supply- and demand-side barriers interact and reinforce one another, thereby constraining the segment below its true potential and limiting its capacity to play a significant role in corporate financing and the implementation of government-led development initiatives.

Second, the study investigates the catalysts that may be leveraged to stimulate the growth of the IMF segment, disrupt the self-reinforcing loops created by existing barriers, and enhance the contribution of IMFs to the broader development of the Indonesian economy.

Third, the study aims to formulate practical recommendations for IMCs to guide the development, management, and marketing of IMFs. In parallel, it seeks to provide policy-relevant recommendations for regulators and policymakers aimed at strengthening the IMF ecosystem and unlocking its full economic potential.

3. Theoretical Framework

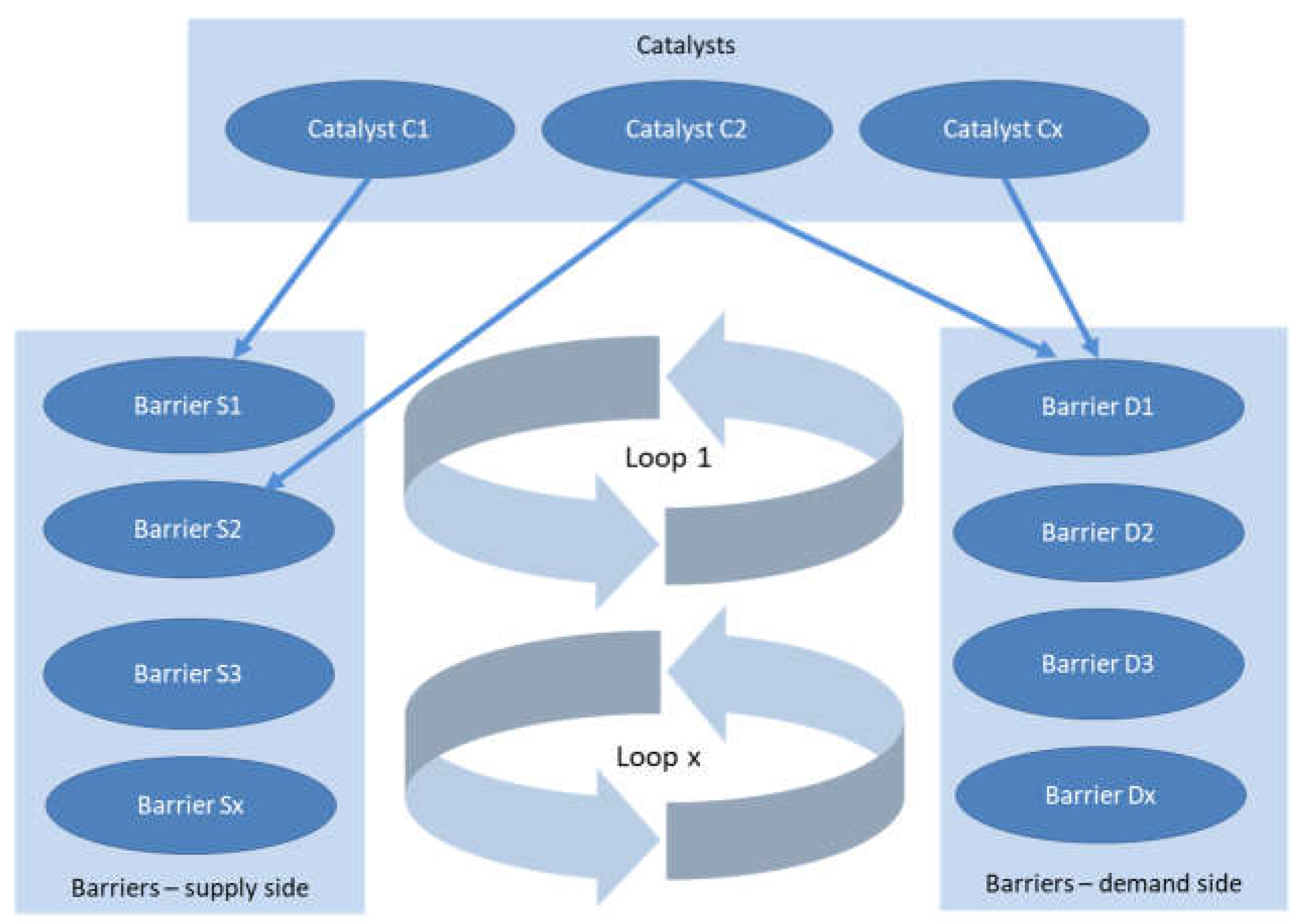

The proposed theoretical framework, grounded in system dynamics theory, posits that the relative underdevelopment of the IMF segment in Indonesia results from the interaction of interdependent factors rather than from isolated influences. It reflects a structural equilibrium of underdevelopment, in which supply-side constraints and demand-side barriers operate as mutually reinforcing mechanisms. Such systemic interactions are consistent with prior research in financial market development, which emphasizes that persistent underdevelopment often arises from reinforcing feedback loops rather than single-point failures (Merton & Bodie, 2005; Mlambo, 2024).

By systematically identifying adoption barriers on both the supply side and the demand side, alongside the catalysts that facilitate adoption and the key relationships among these factors, the framework enables the identification of vicious feedback loops through which impediments reinforce one another. Similar dynamics have been documented in Islamic finance, where limited product depth, weak distribution channels, low financial literacy, and conservative risk perceptions jointly constrain and prevent the sector from reaching the economies of scale necessary to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance product competitiveness - factors that are critical for escaping a persistent growth gap (Beck et al., 2013). At the same time, the framework allows for the identification of virtuous feedback loops, whereby catalysts - such as improved product innovation, enhanced investor awareness, regulatory support, and stronger

Shariah governance - can mitigate existing constraints and unlock growth momentum. The proposed theoretical framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

By anchoring the study’s empirical findings within this systemic perspective, the research moves beyond a descriptive enumeration of obstacles and instead offers a coherent, integrative lens through which the Indonesian IMF landscape can be understood as an integrated and interdependent system. This approach aligns with calls in the Islamic finance literature for holistic, ecosystem-based reforms rather than piecemeal interventions (Qudah et al., 2023). Consequently, the framework serves as a strategic guide for policymakers and industry stakeholders, suggesting that sustained growth can only be achieved through coordinated efforts that simultaneously enhance supply-side market depth and expand demand-side reach.

4. Research Methodology

This study adopts an interpretivist approach to ensure the credibility of the results. This qualitative method is usually chosen to explore the experiences and behaviors of individuals in specific conditions or situations (Woods & Trexler, 2001). The study sample comprises 21 experienced participants, which is considered sufficient for obtaining meaningful insights in a study of this nature (Malterud et al., 2015). Participants were selected based on two criteria. They were required to have a minimum of two years of professional experience working either for an IMC or within a government organization directly involved in the IMF ecosystem (e.g., a financial regulatory body), and due to their roles, they must be familiar with the challenges faced by IMCs when launching, managing, and marketing new IMF funds. It should be noted that investors, who are major stakeholders in the IMF ecosystem, were not directly included in this study. However, several interviewees held marketing or client-facing positions within IMCs and were therefore closely familiar with investors’ needs, preferences, and concerns, which they routinely address as part of their professional responsibilities. As a result, these participants were able to articulate and convey investors’ perspectives during the interviews.

Furthermore, the literature identifies four primary qualitative data collection methods: in-depth interviews, participation in the setting, direct observation, and document review (Marshall & Rossman, 2011). For this study, the in-depth interview method was selected. Specifically, semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives from Indonesian IMCs, regulators, and policymakers. The main interview questions are outlined in

Appendix A. Each interview session lasted approximately 30 minutes, with additional time allotted at the end of each session to allow participants to provide further comments or insights if desired.

Initially, we contacted via email 25 representatives from IMCs and 25 representatives from regulators and policymakers, including the OJK, Bursa Efek Indonesia (Indonesia Stock Exchange, also known as BEI), the central bank of Indonesia, and the Ministry of Finance, with the goal of conducting a total of 30 interviews. This approach proved effective in engaging IMC representatives, who were forthcoming in providing insights and recommendations on strategies to develop the segment. In contrast, regulators and policymakers were initially hesitant to participate, despite assurances of confidentiality. Consequently, follow-up phone calls and emails were necessary to secure a sufficient number of interviews. Ultimately, the study conducted 13 interviews with IMC representatives and 8 with regulators, policymakers and other stakeholders.

To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the IMF segment, we have selected IMCs from diverse categories and backgrounds. The sample includes IMCs that are offering IMFs as well as some that did not offer IMFs at all. It also includes IMCs that are associated with banks and use the banks’ networks for distribution (e.g. PT Panin Asset Management) as well as IMCs that distribute their funds independently (e.g. PT Phillip Asset Management). It also includes IMCs that are associated with foreign fund providers (e.g. PT Maybank Asset Management) as well as purely local providers (e.g. PT Surya Timur Alam Raya Asset Management). Finally, we have considered both large IMCs (e.g., PT Eastspring Investments Indonesia) and small ones (e.g. PT Shinoken Asset Management). This allowed us to have different IMC profiles represented in the study and capture a large spectrum of views and insights about the challenges faced by the IMF segment. Finally, interviews were conducted with a range of representatives, including asset managers, general managers, and marketing managers. As for regulators and policy makers, we have considered representatives from OJK, the finance ministry, and the central bank of Indonesia.

To ensure privacy, participants were assured anonymity and are referred to by pseudonyms in this paper. Thus, the names used are not real and do not correspond to the participants’ real identities. The participants from IMCs and from regulators and policymakers are listed in

Appendix B.

We manually transcribed and analyzed interview data using a thematic approach based on Braun and Clarke (2014) and Guest et al. (2011). The analysis process followed six stages: (i) familiarizing with data through exploration and organization, (ii) generating initial codes by carefully labeling quotes, (iii) developing and reviewing themes and sub-themes to identify patterns, (iv) scrutinizing themes for alignment with research objectives, (v) refining themes to capture their essence, and (vi) reporting the analysis to produce the findings based on the analytical narratives of the data extracts. This process led to the identification of 14 factors impacting IMFs development - 10 impediments and 4 catalysts - which were supported by direct quotes from participants. The impediments include a limited selection of eligible securities, sukuk constraints, liquidity of Islamic securities, funds’ returns, investors’ religiosity, Islamic financial literacy, product awareness, a developing regulatory environment, tax constraints, and access limitations. The catalysts are a young and large population, innovation potential, protective regulations, and government support.

5. Impediment to IMF Development in Indonesia

In this section, we examine the challenges hindering the growth of IMFs and the difficulties faced by IMCs in developing and marketing these funds to potential investors. A key finding indicates that this underdevelopment extends beyond the IMF segment to the broader Indonesian mutual fund industry. The total AUM of mutual funds in Indonesia amounted to approximately $35 billion in 2023 (Goh, 2022), representing less than 6% of third-party deposits in the banking sector, which totaled around $541 billion in 2024 (IDIC, 2024). This contrast underscores a significant opportunity to redirect a portion of Indonesian savings from short-term banking products toward mutual funds - particularly IMFs - which could, in turn, support the country’s long-term economic growth. This observation is further reflected in investor participation. Out of a population of approximately 280 million, only 13.7 million people have invested in mutual funds (KSEI, 2024). This observation is also confirmed by some interviewees such as Mr. Sukarno who noted that mutual funds - whether conventional or Islamic - generally experience low demand among potential investors. Similarly, Mr. Arief emphasized that the mutual fund industry as a whole remains underdeveloped in Indonesia. The identified barriers to the growth and mass adoption of IMFs are summarized below:

5.1. Limited Selection of Eligible Securities

A key factor affecting the growth and adoption of IMFs in Indonesia is the limited availability of eligible underlying securities for investment, which constrains portfolio diversification and may reduce the attractiveness of these funds to potential investors seeking Shariah-compliant investments.

A comparison with Malaysia highlights the magnitude of this constraint. Both the Securities Commission Malaysia and the OJK regularly publish lists of Shariah-compliant equities. Malaysia’s most recent list comprises approximately 850 Shariah-compliant stocks, whereas Indonesia’s list includes around 685 stocks, despite Indonesia applying relatively less stringent screening criteria. More importantly, Indonesia’s Shariah-compliant universe is characterized by a relative scarcity of large-capitalization firms, which further narrows the investable set for IMFs and limits their capacity to construct diversified portfolios with sufficient liquidity and scale.

The disparity is even more pronounced in the sukuk market. Malaysia’s Bond and Sukuk Information Platform (BIX Malaysia) reports hundreds of corporate and government sukuk issuances annually, with a total value ranging between USD 60 and 80 billion. In contrast, OJK statistics indicate that Indonesia records only around 40 to 60 sukuk issuances per year, with a total value ranging between USD 13 and 17 billion depending on the years.

This challenge was highlighted by several participants in the study. For example, Mr. Basuki noted that, unlike other countries such as China - where multiple sectors, including construction, are well represented on the stock exchange - Indonesia’s IDX Composite, the main stock market index, is heavily dominated by the financial and banking sector. However, since most banks are not managed in accordance with Shariah principles and charge Riba (interest), they are excluded from the pool of securities that IMFs can invest in. Mr. Prabowo also highlighted this issue, stating:

“The biggest contributors to the Indonesia stock market index are often conventional financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, financial holdings) which typically are not Shariah-compliant. Since this sector has shown consistent returns, many investors gravitate toward financial and banking stocks or funds tracking them and avoid Islamic funds which exclude financial institutions in their investment strategies.”

Mr. Subianto echoed this concern in the fixed-income space, adding the supply of sukuk represents only a small fraction of the total bond issuances by both corporations and the government. This observation underscores the market, legal, and financial constraints preventing Indonesian corporations from issuing sukuk. These findings are consistent with previous research, such as Endri et al. (2022) and Mawardi et al. (2022) who found that the limited issuance of Islamic securities by Indonesian corporations is primarily due to the higher costs and the associated regulatory limitations (Hidayat, 2024).

5.2. Sukuk Constraints

A significant difference between Malaysia and Indonesia lies in the composition of corporate fixed-income issuances. In Malaysia, most corporate bond issuances are sukuk (80%), whereas in Indonesia, conventional bonds dominate (90%). Furthermore, in absolute terms, corporate sukuk issuances in Indonesia ($2.1 billion) are a fraction of those in Malaysia ($142 billion) (FitchRatings, 2021). Additionally, in Indonesia, the majority of sukuk issuances are from the government, totaling approximately $18 billion (DJPPR, 2024). The primary reason for this disparity stems from differences in legal jurisdictions between the two countries. Malaysia operates under a common law system, which recognizes the concept of trust and beneficial interest, key elements in the structure of Shariah contracts. In contrast, Indonesia follows a civil law system, which does not distinguish between legal and beneficial ownership, limiting the flexibility needed for Shariah-compliant transactions.

Furthermore, Indonesian corporate issuers predominantly rely on Mudaraba and Ijara contracts, both approved by the National Sharia Board, with a stronger preference for Ijara. This contract is favored because it involves the use of tangible assets or projects as underlying collateral. However, this can pose challenges for firms seeking to raise funds for new ventures, as the necessary assets may not be readily available or, in some cases, may not even exist yet. In contrast, Malaysian corporations tend to favor Murabaha, whose popularity stems from its straightforward implementation and the fact that issuers are not required to use existing assets, making it a more accessible option for financing. The above issues were echoed by Mr. Subianto as follows:

“There are structural problems with issuance of all Shariah-compliance instruments and especially sukuk. The structuring of these ones is a cumbersome process. Moreover, Shariah prevents contracts based on tawarruq or bay al inah. It is for these reasons that outstanding corporate sukuk are a fraction of the total corporate bonds. Corporations have no incentives to issue sukuk.”

It is noteworthy that these challenges are comparatively less pronounced in the case of government-issued sukuk. In 2008, the Indonesian government passed a law allowing sukuk to be issued through a government-owned entity, Perusahaan Penerbit SBSN (Sovereign Sukuk Issuing Company). This legislative framework has facilitated sukuk issuances by the government, mitigating some of the asset-related challenges faced by corporate issuers. However, government sukuk are mainly used to finance the budget deficit and have little impact on projects financing and associated economic growth (Al Fathan & Arundina, 2019).

5.3. Liquidity of Islamic Securities

Several interviewees, particularly those from IMCs, identified the liquidity of the underlying securities in which IMFs invest as a major constraint on the development and growth of the segment. These securities largely consist of sukuk and stocks issued by small- and medium-sized companies, both of which tend to exhibit limited market liquidity. This observation is corroborated by IDX Digital Statistics (IDX, 2025), which indicate that liquidity among the 685 Shariah-compliant stocks is highly uneven. Approximately 30-40% of these securities frequently record zero or negligible trading volumes (below IDR 5 million per day), thereby failing to meet the minimum liquidity thresholds required for institutional participation. A similar pattern is observed in the sukuk market, where between 60-75% of corporate sukuk and 20-30% of government sukuk are classified as dormant, as they do not register any trades in a typical month. By comparison, less than 10% of conventional treasury bonds are considered dormant (IDX, 2025).

Liquidity pressures become especially pronounced during periods of market volatility, when heightened investor demand to purchase or redeem units places additional strain on IMCs. Because most IMFs are structured as open-end funds and are heavily invested in low-liquidity instruments, IMCs may struggle to acquire or liquidate positions at fair prices when processing subscriptions or redemptions. Furthermore, even when liquidity is available, wider bid-ask spreads in these markets erodes fund performance. Mr. Iskandar articulated this concern as follows:

“Since IMFs invest in low-liquidity assets (e.g., small capitalizations, sukuk, or money market instruments), fund managers may struggle to find enough liquidity in the market to buy or sell these assets in response to investor demand. This situation makes it challenging for fund managers to execute transactions without impacting the price or performance of the fund, particularly during volatile market conditions.”

These liquidity challenges, combined with the additional costs associated with ensuring Shariah compliance, reduce the incentives for IMCs to design and launch new IMFs, particularly in the context of relatively modest investor demand.

Previous research provides several explanations for the liquidity constraints outlined above. Duqi and Al-Tamimi (2019) observe that the low liquidity of Islamic securities, such as sukuk, is partly driven by investors’ preference to hold these instruments as long-term investments, avoiding short-term speculation and frequent trading. Liquidity is also constrained by the limited availability of market-making activities in Islamic capital markets, largely due to restrictions on short selling. Likewise, Ulusoy and Ela (2018) note that not all sukuk are tradable on secondary markets, as their tradability depends on conditions imposed by respective Shariah supervisory bodies. These structural features collectively restrict the liquidity profile of sukuk and other Shariah-compliant securities.

5.4. Funds’ Returns

Nearly all interviewees identified fund returns as a key factor influencing the mass adoption of IMFs. Indeed, like all investors, Indonesian Muslims seek returns that align with their financial goals, including generating income to support future endeavors such as purchasing real estate, funding children’s education, retirement, and facilitating religious pilgrimage. Mr. Basuki highlighted that “by mutual fund standards - whether index or general funds - Shariah-compliant funds tend to underperform. This is largely due to the nature of the underlying securities, such as Shariah-compliant stocks and sukuk, which have historically delivered lower returns.” Similarly, Mr. Subianto added the following: “At the end of the day, investment performance is the key factor attracting capital flows. Islamic funds, particularly equity funds, have historically lagged their conventional counterparts in terms of performance.” Ms. Kirana pointed to the nature of stocks used in conventional and IMFs, stating:

“While the general index of the stock exchange is predominately financial stocks, the Shariah index is largely concentrated in commodities and telecommunications. Although commodities stocks can generate high returns on par with financials, they tend to be very cyclical and depend on commodities prices on the international markets. As for telecommunications stocks, they tend to have lower returns due to competition and infrastructure investments. So globally, the Shariah index is structurally underperforming the general index. Moreover, Indonesian investors tend to prioritize historical fund performance rather than evaluating the underlying investment strategies.”

These observations are also confirmed by Ms. Ratih, Mr. Bakti, and Mr. Djuanda as well as by empirical evidence. For instance, Sulaiman and Maesarach (2025) report that IMFs underperformed conventional equity mutual funds over the 2020–2024 period.

These findings are also coherent with previous literature about the positive relationship between fund performance and flows and how previous performance is considered by investors when selecting funds to invest in (Galloppo et al. 2024; Vidal et al., 2025). They are also consistent with previous studies showing that IMFs generally underperform their conventional counterparts (Hassan et al., 2020; Mansor et al., 2020; Elfakhani, 2024). However, it should be noted that other studies have reported no significant performance difference between IMFs and conventional funds (Boo et al., 2017; Reddy et al., 2017).

The poor returns are further exacerbated by the high management fees charged by IMCs, which vary across fund classes and IMCs and range from 150 to 275 basis points. These relatively high fee levels can be attributed to the limited scale at which many IMCs operate, as well as the additional costs associated with maintaining Shariah compliance. These findings are consistent with previous research, such as Fikri & Yahya (2019) who observed that Islamic mutual funds often charge high fees.

5.5. Investors’ Religiosity

Several interviewees highlighted an observation that extends beyond IMFs to the broad Islamic capital markets, relating to cultural and behavioral characteristics in Indonesia. They noted that, compared with countries such as Saudi Arabia, Indonesian Muslim investors tend to adopt a more moderate approach to the interpretation and application of Shariah principles in their financial decisions. This moderate orientation is supported by empirical evidence; for example, a 2023 Pew Research survey indicates that only 64% of Muslims in Indonesia support the use of Shariah as national law, compared with 86% in Malaysia (Pew Research, 2023). This orientation influences how investors balance Shariah considerations with financial factors such as returns and risk. Mr. Arief summarized this point as follows:

“the majority of Muslims in Indonesia (especially in Java) follows Nadhatul Ulama[1] teachings that somewhat blend Shariah principles and traditional beliefs that are more pluralistic from the start. Due to these differences, I don’t see how Islamic mutual funds or any Islamic financial products could gain traction in the foreseeable future.”

Mr. Akbar also echoed this perspective while Ms. Mawar observed that many Indonesian investors adopt a largely secular investment mindset, placing greater emphasis on expected returns than on strict adherence to Shariah principles. Consequently, positioning a mutual fund solely based on its Islamic features may not substantially enhance its appeal to the broader retail market. Similarly, Ms. Nabila noted that while Shariah compliance is valued by certain investor segments, it is not the primary consideration for most prospective investors. She added that “launching and developing IMFs is not always a strategic priority for IMCs, as the level of demand for strictly Islamic investment products varies across the population.” Mr. Subianto reinforced this view by highlighting that competitive returns remain the dominant factor driving investor consideration. In his assessment, strong performance is essential for capturing the attention of Indonesian investors, regardless of whether the product is conventional or Shariah-compliant. Mr. Sukarno offered a similar perspective, noting:

“Shariah funds are considered new in Indonesia vs. the conventional ones which were introduced in the 1990s. There was also no significant difference in performance between conventional and Shariah-compliant funds. The current investors are usually “old” investors who do not think Shariah principal will make a material difference as long as the returns are quite similar.”

The above observations are consistent with findings from prior research that highlight the influence of investor religiosity on financial decision-making. For example, Al-Salem and Mostafa (2019) showed that religiosity shapes preferences toward Shariah-compliant investments and identified three distinct investor segments: enthusiasts, laggards, and rejectors. Similarly, Zainudin et al. (2019) and Lestari et al. (2021) demonstrated that religiosity moderates investment attitudes, with notable differences between moderately religious and highly devout individuals in terms of risk propensity and investment choices. These insights also align with other studies examining religiosity in the context of IMFs (Yusuff et al., 2020; Sumiati et al., 2021; Che Hassan et al., 2024), and in the general context of Islamic finance (Alzadjal et al., 2022; Gunardi et al., 2022).

5.6. Islamic Financial Literacy

Islamic financial literacy refers to the knowledge, skills, and awareness of financial concepts, products, and services that enable individuals to make informed financial decisions in accordance with the principles and rules of Islamic law (Sari et al., 2022). Several participants in the study expressed concerns regarding the overall level of Islamic financial literacy and the limited product knowledge among potential investors. As noted by Mr. Prabowo, Indonesian investors generally exhibit a preference for tangible or “real” assets, such as precious metals, land, and property, over financial instruments. When they do engage in financial asset investment, they tend to favor fixed-term deposits rather than mutual funds, whether Islamic or conventional. This behavior appears to be driven by limited knowledge and understanding of variable price investments. Mr. Zahid echoed this sentiment, adding, “Although Indonesia has one of the largest Muslim populations in the world, this advantage is undermined by a limited Islamic financial literacy. This challenge is partly attributable to the country’s education system, which contributes only modestly to the development of Islamic financial literacy among students” Similarly, Mr. Iskandar highlighted limited Islamic financial literacy as a significant challenge, stating:

“Many potential Indonesian investors, especially those who are young or new to investing, lack an understanding of Shariah investment principles. Without sufficient understanding of how Islamic mutual funds work, many investors opt for more familiar and less complicated investment products, such as bank fixed deposits.”

These findings are corroborated by the National Financial Literacy Survey conducted by OJK, which reported that only a small proportion of the population possesses the knowledge and skills necessary to manage finances in accordance with Islamic principles, as reflected by an Islamic financial literacy index of just 9.1%. This stands in stark contrast to the overall financial literacy index, which reached 49.6% (Shofa, 2023). They are also consistent with past research such as Yusfiarto et al. (2023) who found that increasing Islamic financial literacy has a significant positive effect - either directly or indirectly - on investment intentions in the Islamic capital market in Indonesia, and Mutamimah and Sueztianingrum (2021) who found that financial literacy has a positive influence on IMFs investment in Indonesia. Other studies (Yusuff et al., 2017; Aziz & Kassim, 2021; Amin et al., 2022) also identified Islamic financial literacy as a significant factor influencing the adoption of IMFs. In the broader context of conventional mutual funds, a growing body of research similarly demonstrates a positive relationship between financial literacy and participation in mutual funds and other financial products (Khan et al., 2020; Nicolescu et al., 2021; Oehler et al. 2024; Abreu et al., 2025).

5.7. Product Awareness

Participants in the study highlighted the limited awareness of IMFs among potential investors and its role in constraining their adoption. For example, Mr. Hatta noted that many Muslims in Indonesia are unfamiliar with IMFs or perceive them as sophisticated, exclusive investment products intended primarily for high-net-worth Muslims. This perception persists despite various initiatives by the regulator aimed at promoting Islamic mutual funds as accessible investment vehicles suitable for the broader public. Moreover, the majority of Indonesian Muslims exhibit a conservative risk profile, favoring low-risk financial products such as Mudharabah deposits in Islamic banks, which reached approximately $15 billion in 2020 (Umam et al., 2021) or tangible assets such as real estate, land, and gold. Similarly, Mr. Bacharuddin confirmed that “the limited market share of IMFs is fundamentally linked to both low public awareness and insufficient governmental support” while Mr. Zahid attributed the lower adoption of IMFs to the poor awareness by saying: “IMFs are not large enough to get the attention of potential investors. More than 90% of the total assets under management are probably conventional funds. This is an estimate based on the fact that there are no Shariah-compliant fund in the top 10 mutual funds.”

These statements are corroborated by previous research which indicate that product awareness is a significant factor in the adoption of Islamic financial instruments. For example, both Sudarsono et al. (2021) and Purwanto (2022) found product information and awareness to be a significant variable in Muslim’s adoption of Islamic financial products and services in Indonesia. Similarly, Bakar et al. (2015) found that the limited knowledge as a reason holding back investors from participating in variable-price Islamic investment trusts.

5.8. A Developing Regulatory Environment

Most interviewees commended the regulators for implementing a regulatory framework designed to protect investors. They noted that the overall regulatory environment is sufficiently mature in terms of investor protection with several regulations issued by both OJK and BEI to safeguard investors’ interests. However, they also noted ongoing ambiguity regarding the criteria used to classify a security as either Shariah-compliant or conventional. For example, Ms. Mawar explained that, for a company’s stock to qualify as Shariah-compliant, the OJK applies a threshold whereby interest-based debt must not exceed 45% of total assets (IDX, 2017), whereas the commonly applied international benchmark is 33%. She emphasized that if the stricter 33% ratio were used, the number of Shariah-compliant stocks in Indonesia would be significantly limited.

Ms. Kirana echoed this observation and noted that the criteria used to classify securities as Shariah-compliant or conventional remain an area that would benefit from greater clarity and consistency. She acknowledged that the OJK has been proactive in refining these standards; however, the frequent changes to the criteria may create uncertainties for market participants seeking stable and transparent screening guidelines. In addition, she pointed out that institutional investors such as insurance companies are subject to detailed reporting obligations, requiring them to disclose their mutual fund holdings on a security-by-security basis. While these requirements demonstrate the regulator’s strong commitment to oversight and transparency, they may also create operational disincentives for institutional investors, who may find it more convenient to invest directly in individual securities rather than through mutual funds.

It is important to note that several prior studies have also highlighted areas within the Indonesian regulatory framework that present opportunities for further refinement. For example, Pradana (2022) observed the inadequate regulations of Islamic investments are a factor contributing to the slow development of IMFs. Khasanah et al. (2024) identified areas of misalignment among the Sharia Economic Law Compilation (KHES), regulations issued by the OJK, and fatwas issued by the DSN-MUI. Such discrepancies can create uncertainty and variations in implementation, suggesting the need for enhanced harmonization to strengthen legal clarity for the issuance of Shariah-compliant financial instruments. Moreover, Syazali et al. (2024) found that investor protection in relation to insider trading in Indonesia’s capital market could be further improved, noting that the existing Capital Market Law does not comprehensively address all the dimensions of this issue.

5.9. Tax Constraints

Taxes related to IMFs and to underlying securities were raised as another concern that is impacting the returns of IMFs and hindering their development. Mr. Banyu focused on sukuk and mentioned that:

“To support the wider adoption of sukuk instruments, and by extension, the growth of sukuk-based IMFs, it is crucial to establish tax neutrality between sukuk and conventional bonds. Unlike conventional debt instruments, sukuk structures typically require multiple transfers of underlying assets between the originator and investors. Under the current interpretation of Indonesia’s 2009 Value Added Tax (VAT) Law, each transfer can trigger VAT liabilities. In the absence of dedicated tax provisions for sukuk, this mechanism creates additional transaction costs for issuers and reduces the relative attractiveness of sukuk for corporate financing. Enhancing tax clarity and ensuring parity with conventional bonds would therefore provide stronger incentives for issuers, ultimately supporting the development and expansion of IMFs.”

Focusing specifically on Islamic mutual funds, Mr. Iskandar noted that their attractiveness could be strengthened through the introduction of fiscal incentives, such as reduced tax rates or exemptions on income generated from investments in IMFs. Such measures may encourage more investors to consider IMFs. Ms. Mawar noted that IMFs incur additional costs compared with conventional funds, including expenses related to Shariah-compliance audits. To ensure a more level playing field, she suggested that the government consider introducing tax incentives that would make the launch and management of these funds more attractive to providers.

These findings are in line with past literature about the taxation of Islamic financial products. For example, in the case of sukuk, Hassan and Majid (2022) found that unlike Malaysian regime which goes beyond imposing tax neutrality and provides vast tax incentives to the sukuk issuer, the SPV, and the investor, Indonesian regime, on the other hand, provides specific incentives only to domestic and foreign investors. Additionally, Kasri et al. (2020) found that one of the main challenges for the development of Islamic pension funds in Indonesia was related to the double taxation of retail investors.

5.10. Access Limitations

Several interviewees pointed out the challenges related to fund distribution, noting that some IMCs lack the necessary channels to reach the broader public. For instance, Ms. Indah highlighted that “in some areas of the country, people don’t have easy access to Islamic investments, especially outside of big cities.” Mr. Iskandar also emphasized that “the segment has room for improvement in terms of distribution and accessibility for retail investors,” and recommended that “IMCs utilize the distribution networks of Islamic banks to market IMFs.” Mr. Sukarno raised concerns about the onboarding process for new investors, stating, “Onboarding and KYC for new investors are too complicated and do not align with the target market, which mainly consists of young, mass-market individuals with low Islamic financial literacy.” Mr. Prabowo echoed this sentiment, noting that regulatory limitations on retail investors, particularly the stringent OJK guidelines, hinder their ability to engage freely in the market. These barriers may ultimately discourage broader participation and limit the growth of the segment.

These observations are corroborated by OJK statistics which shows that Indonesia has an Islamic financial inclusion index of only 12.1 percent (Shofa, 2023). In other words, only one out of ten Indonesians can access useful and affordable Shariah-compliant financial services and products. This is a stark contrast to the overall financial inclusion index, which reached 85.1 per cent.

These observations are further supported by evidence from the broader mutual fund literature. For example, Yogo et al. (2025) document a positive relationship between access and participation, while Katwala and Sadhwani (2024) show that fintech platforms play a critical role in facilitating the distribution and adoption of mutual funds. In the context of IMFs, prior studies similarly find that greater financial inclusion is associated with higher IMF participation (Mutamimah & Sueztianingrum, 2021; Mutamimah et al., 2023). Moreover, Asmara and Abubakar (2019) demonstrate that Islamic financial inclusion can be substantially enhanced through the provision of IMFs via digital platforms. This pattern is increasingly evident in Indonesia, where a growing number of fintech platforms actively market investment products - particularly to younger investors - through extensive social media promotion. Notably, major digital marketplaces such as Bukalapak and Tokopedia have also begun offering IMFs to their users.

6. Catalysts for IMFs Development in Indonesia

Although the challenges discussed in the previous section indicate that the business environment may not be fully supportive of the growth of IMFs in Indonesia. Our interviews reveal that the Indonesian context presents a distinctive set of catalysts that, if effectively leveraged, could significantly accelerate the development of this segment. These include a young and large population, innovation potential, protective regulations, and government support that can foster growth and innovation.

6.1. A Young and Large Population

Unlike other Muslim-majority countries such as Malaysia (with a population of 34.1 million) and Saudi Arabia (37 million), Indonesia represents the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, with a population of approximately 277.5 million, 87% of whom identify as Muslim. Notably, more than half of this population is under the age of 30, offering a substantial demographic advantage in terms of Islamic financial inclusion and long-term market potential. This potential is further underscored by the pronounced imbalance in asset ownership across age groups. Investors aged 60 and above - representing only 2.96% of the total investor population - hold approximately $50 billion in securities. In contrast, investors aged 30 and below, who constitute 54.92% of the investor base, collectively own just $2.4 billion in securities (KSEI, 2024).

Three key dynamics underpin this catalyst. First, the older population, which is heavily invested in mutual funds, has moved beyond the wealth accumulation phase and is now drawing from its savings for retirement, supporting children, and other needs. In contrast, the younger population is just beginning to invest. Mr. Subianto confirmed that a positive shift is occurring, with the number of young investors in IMFs on the rise. This growth is driven by the increasing availability of online investment platforms, improvements in Islamic financial literacy, as well as the lowering of minimal initial investments to 10,000 IDR (less than $1) for some funds allowing aspiring young investors including these with low income to access IMFs. Mr. Subianto added that “young people are starting to see investment as part of their lifestyle”. Mr. Banyu mentioned that “the young generation is familiar with technology including mobile applications and can be easily converted into IMF investors.” Similarly, other participants emphasized the importance of leveraging technology with the young generation to boost awareness and improve Islamic financial literacy. Mr. Prabowo highlighted that “technology and digital platforms should be used to engage the younger demographic, offer literacy programs, and run marketing campaigns.” He also suggested that collaborating closely with Islamic banks could help alleviate apprehension among potential investors who are still unfamiliar with IMFs.

However, there is a second dynamic at play as participants shared differing opinions regarding the investment behavior of this demographic, suggesting the presence of multiple segments within the younger population. For instance, Mr. Banyu noted that “young investors typically begin with low-risk financial products, such as money market and sukuk funds, before gradually transitioning to higher-risk investments like equity funds.” In contrast, Mr. Prabowo observed that “younger generations tend to adopt a more aggressive investment approach, seeking higher returns through newer avenues like cryptocurrencies. This trend could potentially shift their focus away from mutual funds in general, and IMFs in particular, even though the latter aligns with their faith.” He pointed out that, while there are approximately 14 million mutual fund investors in Indonesia, the number of cryptocurrency investors has recently surpassed 22 million, illustrating the growing appeal of digital assets among the younger demographic.

A third dynamic is Indonesia’s sustained economic growth, which has supported the expansion of the middle class and, consequently, the accumulation of household wealth. This growing socio-economic segment represents a promising and increasingly significant market for IMFs.

In conclusion, the ongoing demographic and economic shifts - toward a younger, more diverse, and increasingly affluent population - present a significant and urgent opportunity for IMCs to expand their market presence and accelerate the adoption of IMFs. This urgency is further amplified by the emergence of alternative investment avenues, such as Islamic crowdfunding and digital assets, which have the potential to draw prospective investors away from traditional IMFs.

6.2. Innovation Potential

Participants in the study, particularly those from IMCs, highlighted the significant potential for innovation within the IMF segment. They emphasized that there remains considerable opportunity to design and implement new strategies for both the development and marketing of these funds to retail investors. For instance, Mr. Reza noted that certain IMFs invest in overseas markets. These funds benefit from lower inflation rates abroad, offer competitive returns, and demonstrate substantial growth potential. However, Mr. Sukarno noted that the minimum initial investment for these funds is $10,000, which is significantly higher than what typical investors can afford. Furthermore, Muhammad Irsyad mentioned that the regulator does not allow mixed funds where part of a fund AUM is invested locally and the other part in offshore securities. These funds, if approved, could attract investors with their diversification (both in terms of sectors and geography). Ms. Mentari focused on distribution aspects and mentioned that although the onboarding and KYC procedures for new investors can be stringent, there is significant potential for partnerships between IMCs and Islamic banks. She highlighted that Indonesia’s largest Islamic bank (Bank Syariah Indonesia) is launching a new mobile app, which could be leveraged by IMCs to expand the retail investor segment and increase access to IMFs. A similar point was made by Mr. Prabowo, who suggested that IMCs could tap into a large retail market by entering into distribution agreements with Islamic banks or with conventional banks having Islamic branches. Mr. Iskandar emphasized that accessibility to IMFs could be significantly improved by collaborating with digital platforms. By leveraging these distribution networks, IMCs could effectively market their funds to a broader audience.

These findings align with previous research, such as Gharbi (2025) and Najwa et al. (2024), who identified the significant role of financial technology and digital platforms in the adoption and development of Islamic financial products. They are also consistent with Rahabi et al. (2021), who highlighted the impact of technological innovation - such as enhanced online user experiences - on the growth of online mutual fund investments. Similarly, Achsien and Purnamasari (2016) found strong potential in using online crowdfunding to support the development of Islamic finance, including IMFs.

6.3. Protective Regulations

Interviewees had differing views on the regulations in terms of investors’ protection. IMC representatives felt that the regulations were stringent, while representatives from the regulator and other policy makers argued that current regulations were sufficient. One case that was cited by both groups was related to Minna Padi Investama (Minna Padi). This one highlighted both the decisive actions taken by OJK to protect investors and the need for improvements in the regulatory oversight process. Ms. Mawar summarized this case as follows:

In 2019, Minna Padi, an IMC listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange, was found to have violated multiple provisions of OJK Regulation No. 39/POJK.04/2014. As a result, it was ordered to close six mutual funds (letter number S-1422/PM.21/2019 dated November 21, 2019), including an IMF (Amanah Saham Syariah). The dissolution of these funds led to significant losses for over 4,000 investors, as Minna Padi only refunded 20-30% of customer funds, while 30 - 40% were returned in the form of shares. Most of these shares were illiquid, leading to a total loss of IDR 4.8 trillion.”

Mr. Iskandar summarized the regulatory situation in Indonesia as follow:

“The regulatory framework for the Islamic mutual fund segment in Indonesia is quite mature in some respects, particularly in terms of investor protection and maintaining compliance with Shariah principles. However, the segment still has room for innovation, both in terms of the products offered and in terms of distribution and accessibility to retail investors. The Indonesian government has provided sufficient support through policies that facilitate the development of Islamic financial markets, but challenges related to support for innovation in the sector, education, and access still need to be addressed.”

Mr. Bagus and Ms. Indah noted that the regulatory framework is evolving, with the OJK actively engaging in multiple working groups with IMCs to ensure that regulations both encourage innovation and safeguard investors. She added, however, that regulatory decisions are not driven solely by investor protection; broader national economic interests are also taken into consideration. For instance, IMCs are prohibited from offering conventional offshore funds (although Islamic offshore funds are permitted) in order to prevent Indonesian capital from flowing abroad. While such regulations support national economic priorities, they simultaneously limit the range of investment options available to investors.

These findings align with previous research, which also reports mixed views on the effectiveness of protective regulations. Wardani and Basri (2020), for instance, for instance, praised the OJK’s effectiveness on the enforcement side - particularly its decisive actions in shutting down investment companies with potential fraud risks - but found that it has not been fully effective in its preventive measures, as fraudulent investment schemes continue to emerge and financial literacy and inclusion remain low in Indonesia. Conversely, Rizky et al. (2024) argue that the OJK’s regulatory enforcement contributes positively to creating a more structured and secure investment environment for investors.

6.4. Government Support

Participants noted that one way the government could support IMFs is by making direct investments in these funds through related financial institutions, such as the Hajj (pilgrimage) fund. Such direct investments would help stimulate demand and provide a strong incentive for issuers to offer more Shariah-compliant securities. For example, the Hajj Fund Management Agency (BPKH), established in 2017, could play a pivotal role in supporting the IMF segment by investing a portion of its funds directly into existing IMFs or by providing seed capital for the launch of new funds. The Hajj Fund currently manages assets of approximately $9.8 billion, representing a substantial potential source of capital to stimulate both demand and market development (Sipahutar et al., 2024), however most of these funds are invested in government sukuk (50%) and time deposits (30%) with only 6% of the AUM invested in IMFs and corporate sukuk (Hulwati et al., 2023). Another way, in which the government can support this segment is by stimulating the supply side by having these related financial institutions investing directly in Shariah-compliant stocks and corporate sukuks. This will encourage issuers to offer more Shariah compliant securities and expand the investment universe available to IMFs, thereby increasing their overall attractiveness. In addition, by establishing a more mature and robust regulatory framework, the government could strengthen investor trust and confidence, ultimately fostering greater participation in IMFs. Finally, Ms. Indah mentioned Komite Nasional Ekonomi dan Keuangan Syariah (National Committee for Islamic Economy and Finance), commonly known as the KNEKS, which was established by the government in 2020 with the aim of developing and promoting the Islamic economy, and the Islamic financial sector including IMFs.

These findings are consistent with previous studies, such as Pradana (2022), who identified a positive relationship between government support and the development of IMFs in Indonesia. Najeeb and Vejzagic (2013) found that a key factor contributing to the development of Malaysia’s Islamic capital markets is the strong and consistent political support for the industry from the country’s highest leadership.

7. Discussion

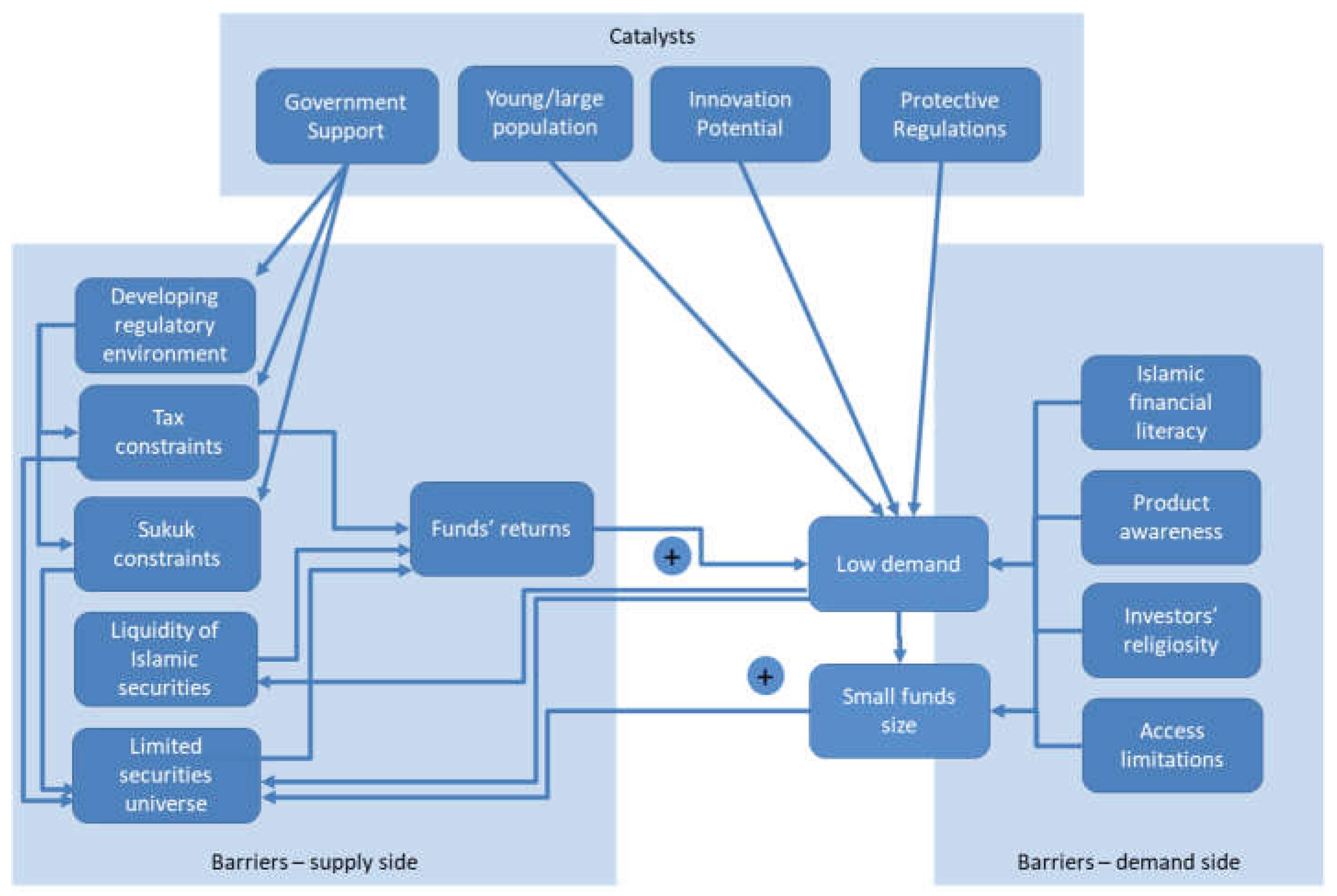

This section presents an analysis of the main findings related to the barriers and catalysts influencing the development and growth of IMFs in Indonesia. A key insight from the interviews is that, although Muslim investors in Indonesia consider IMFs, most fall into a moderate investor category, meaning they weigh risk-adjusted returns alongside Shariah compliance when making investment decisions. However, IMCs face significant challenges in simultaneously meeting these dual imperatives due to two implied factors, namely, the small size of IMF funds and the low demand for these funds. These two factors interconnect the identified barriers and allow these ones to act on each other into two re-enforcing and vicious loops that collectively impede the sustainable development and expansion of IMFs in Indonesia.

The first loop can be called the performance loop. It is summarized as follows: because of high compliance costs (audit, screening, etc.), low liquidity of the underlying securities and the associated higher trading costs, and other tax constraints, IMFs net returns are impacted and are lower when compared with conventional funds. This, in turn, reduces investor demand, which leads to limited fund scale, lower liquidity of underlying securities and higher management fees. The low liquidity and higher management fees close the loop as they impact the funds’ net returns.

The second reinforcing loop, referred to as the issuance loop, arises from the constraints associated with sukuk issuance, including the procedural and structural complexities faced by corporate issuers. These constraints increase issuance costs and burden, leading to reluctance among corporations to offer Shariah-compliant securities. As a result, the investable universe available to IMFs remains limited, constraining portfolio diversification and resulting in narrow fund strategies, subdued investor demand, and persistently small fund sizes. In turn, small fund size weakens demand for Shariah-compliant securities, thereby reinforcing issuers’ reluctance to issue sukuk and closing the loop.

These loops as well as the interconnections between barriers and catalysts are illustrated in

Figure 2.

The systemic framework shows that the low liquidity of Islamic securities and limited securities universe play a key role in creating the two reinforcing loops. To decouple these vicious cycles and unlock associated traps, it is recommended that the government play a more proactive role in facilitating the development of corporate sukuk. One potential measure would be to introduce legislation enabling private issuers to adopt the same beneficial ownership framework currently used for government sukuk, thereby reducing issuance barriers and encouraging greater market participation. Furthermore, because of the limited pool of eligible securities, IMFs offer only modest differentiation, resulting in a narrow set of choices for investors. Although some funds focus on equities or sukuk, the market lacks broader sectoral diversification, such as exposure to real estate, commodities, or other alternative asset classes. Offshore Islamic funds are permitted, but their high minimum investment thresholds make them inaccessible to most retail investors. To address this, IMCs could expand their product lineup by introducing balanced or thematic funds and lowering minimum investment requirements to broaden participation.

Participants also highlighted the issue of double taxation affecting certain sukuk structures, which reduces returns, undermines their attractiveness, and discourages issuance. These effects contribute to both the performance and issuance loops identified in the framework. To address this constraint, participants recommended legislative reforms to eliminate double taxation and ensure regulatory parity between sukuk and conventional bonds. Some further suggested the introduction of targeted tax incentives for Shariah-compliant funds as a means of stimulating investment and supporting market development.

On the investor side, the study identified the generally moderate religious orientation of potential investors as a factor limiting interest in IMFs. It also identifies two key factors contributing to the low interest among potential investors. These are the limited product awareness and Islamic financial literacy, as many potential investors are either unaware of Shariah-compliant funds or have misconceptions about their structure and benefits. Together, these factors reduce demand for IMFs and limit funds’ size, thereby reinforcing the two feedback loops identified above. To address limited Islamic financial literacy, several interviewees recommended closer collaboration between policymakers, educational institutions, and IMCs to enhance public understanding of Islamic finance. They emphasized the importance of integrating Islamic investment education into school and university curricula, thereby introducing Shariah-compliant investment concepts at an earlier stage. In addition, respondents suggested that the OJK, in cooperation with Islamic banks such as Bank Syariah Indonesia and relevant non-governmental organizations, intensify public awareness campaigns on Islamic finance and its underlying principles. Finally, some policymakers underscored the complementary roles of ulemas (Islamic scholars) and marketing brand ambassadors in promoting Shariah-compliant investing and strengthening trust among potential investors.

The study also identified access infrastructure as a significant concern which impacts demand. This challenge is compounded by the geographic extent and island nature of the country, as well as the limited availability of digital platforms and the continued reliance on traditional banking channels. These factors hinder accessibility, particularly for the young, tech-savvy population in rural areas. However, it is worth noting that digital platforms like Bareksa and Bibit, which provide access to IMFs, have seen significant growth and are particularly appealing to the younger generation.

Furthermore, the study identified several regulatory limitations that need to be addressed by decision-makers. While Indonesia’s OJK regulates Islamic finance, the associated regulatory framework may lack clarity or consistency, resulting in overlaps with conventional regulations. Additionally, participants highlighted the challenges faced by some private corporations in structuring certain types of sukuk due to legal complexities on one hand, and the evolving criteria for Shariah compliance on the other. This inconsistency undermines the trust of some potential investors, making them skeptical about the authenticity of Shariah compliance. Furthermore, culturally, Indonesians tend to favor tangible assets, such as precious metals and property, over financial instruments like IMFs.

On the other hand, interviewees praised Indonesia’s investor protection laws. For example, the mandatory oversight by the National Sharia Board (DSN-MUI) ensures compliance, which in turn boosts investor confidence in the authenticity of IMFs. They also commended OJK’s regulations and enforcement actions. These regulations are further supported by government-backed educational programs and awareness campaigns, such as KEJAR (National Strategy for Financial Inclusion), which encourage underserved populations to engage with formal financial organizations, including IMCs. These initiatives act as catalysts for enhancing product knowledge and Islamic financial literacy, further promoting the adoption of IMFs. Finally, the study identifies government support as a key catalyst for the growth of the IMF segment. This includes the issuance of sovereign sukuk and green sukuk providing high-quality, Shariah-compliant assets in which IMFs can invest.

At a broader level, interviewees highlighted several demographic and macroeconomic factors expected to shape the long-term adoption of Islamic mutual funds. They emphasized the country’s large, youthful population, with 50% of Indonesians under the age of 30, many of whom are at the stage of investing and building wealth. Additionally, Indonesia’s status as home to the world’s largest Muslim population creates a natural demand for Shariah-compliant financial products that align with Islamic principles, such as the prohibition of Riba (interest), Gharar (uncertainty), and investments in unethical sectors like alcohol, tobacco, and gambling. Other major trends include a rising middle class with increasing disposable income, steady economic growth, stable inflation, and the emergence of Halal industries, such as palm oil and mining, which provide investment opportunities for IMFs.

It worth noting that at the international level, some countries such as Malaysia and Saudi Arabia have overcome growth traps in IMF ecosystems, while several others - including Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Pakistan- still face barriers that hinder IMF development and more broadly Islamic finance. Many of these barriers are shared across markets and mirror those identified in this study, including limited depth of the Shariah-compliant investable universe, low secondary-market liquidity, limited financial literacy, high fees, regulatory frictions, inconsistent Shariah standards, and competition from alternative Shariah-compliant instruments (Hassan et al., 2020; Saleem et al. 2021; Elfakhani, 2024; Sagiyeva et al. 2025).

Each country also exhibits context-specific constraints. In Turkey, high inflation encourages investment in inflation-linked government bonds, foreign exchange deposits, and gold, reducing IMF appeal (Sui et al., 2020). In Kazakhstan, underdeveloped institutions and shallow capital markets limit IMF growth (Shirazi et al., 2022), while in Pakistan, high-yield, low-risk government Islamic instruments crowd out demand for IMFs (Bibi et Mazhar., 2019). Taken together, these findings suggest that although Indonesia shares several structural challenges with other emerging Islamic finance markets, effective policy responses must prioritize improving market liquidity, broadening the Shariah-compliant investable universe, and strengthening awareness, Islamic financial literacy, product knowledge, and access.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Implications

The study reveals that the IMF segment in Indonesia faces notable challenges on both the supply and demand sides. On the supply side, key constraints include a limited pool of eligible investment securities, both in equities and sukuk, as well as low liquidity in these instruments. Additionally, IMFs frequently deliver lower returns compared to their conventional counterparts, which in turn diminishes their appeal to potential investors. The segment also contends with restricted distribution channels, tax constraints, and a dynamic regulatory environment, which adds complexity to fund management and compliance. On the demand side, challenges stem from a substantial segment of moderate investors who balance Shariah compliance with risk-adjusted returns, as well as from limited awareness and relatively low financial literacy regarding Islamic finance principles. Addressing these barriers presents an opportunity to expand investor participation and foster the sustained growth and development of Indonesia’s Islamic mutual fund segment.

The study also identified several key enablers that, if effectively leveraged, could drive the growth of IMFs in Indonesia. These include robust investor protections, government support, a growing economy, and a burgeoning middle class. Additionally, the emergence of a young, tech-savvy population with an interest in innovative financial products aligned with their religious values represents a substantial opportunity for the growth of the IMF segment. Together, these IMF enablers foster the financing of Shariah-compliant businesses, contribute to the broader economic development, and support the advancement of the Muslim community.

Globally, the study reveals that IMF ecosystem is trapped into underdevelopment state due to self-reinforcing barriers both on the supply and the demand sides. As a result, IMFs have yet to fulfill their potential as long-term investment vehicles within diversified Shariah-compliant portfolios, nor as effective financing instruments for local corporations and government projects. Addressing the challenges facing the segment requires coordinated efforts from policymakers, regulators, and IMCs. Key priorities include streamlining and harmonizing regulations, introducing tax incentives, expanding sukuk issuance, developing innovative fund structures, improving accessibility and distribution through technology, and strengthening public awareness and Islamic financial literacy. Collectively, these measures would support the growth of IMFs in Indonesia and could position the country as a global hub for Islamic finance.

Finally, several of the recommendations outlined above had demonstrated considerable effectiveness in neighboring Malaysia. This country’s model and experience could be adapted to the Indonesian context to accelerate the development of the IMF segment, better meet the needs of Muslim investors, and simultaneously support the financing needs of local companies and the government.

8.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting its findings and practical implications. The first limitation relates to the stakeholders included in the study. While this research considered IMCs, policymakers, and regulators, it did not include investors - either retail or institutional. As the holders of IMF units, investors would provide valuable insights and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of market dynamics within the IMF segment. However, it should be noted that several interviewees from IMCs maintain direct contact with investors - particularly those serving in marketing or client-facing roles - and are therefore well informed about their customers’ concerns, preferences, and investment needs. Additionally, the study did not consider issuers, such as corporations, to confirm the reasons behind the limited issuance of Shariah-compliant securities. Future studies should include these stakeholders to better understand their concerns and the challenges they face.

Furthermore, although our study identified an important set of factors that play a role in the adoption and growth of IMFs in Indonesia, this was done through a qualitative approach and future quantitative studies with a larger sample of participants should confirm the significance and the relevance of the identified factors through appropriate adoption models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT).

Additionally, our study has uncovered the presence of competing products such as Islamic exchange traded funds and Islamic crowdfunding investments. Some of these products are particularly attractive to the younger generation as they require lower initial investments and have lower fees. Future research could investigate the potential growth of these products and spillover effects from traditional IMFs.