1. Introduction

Currently, the only effective way to control HIV infection is the simultaneous use of several drugs in an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen. The introduction of ART into clinical practice has increased the life expectancy and improved the quality of life of HIV-infected patients, as well as reduced the risk of infection transmission and the rate of its spread [

1,

2]. Increased availability and widespread use of antiretroviral drugs are contributing to the development and spread of HIV drug resistance. Mutations of HIV drug resistance to all ART drugs used in clinical practice are now known [

3]. Cross-resistance can also develop between drugs within the same class [

4]. The emergence of new drug-resistant HIV variants is due to the virus’s natural variability in the presence of antiretroviral drugs. Once acquired, drug resistance can be transmitted from patient to patient and observed in HIV-infected patients with no prior treatment experience. Among the factors contributing to the development of HIV resistance, the most important are the genetic and pharmacological barriers to resistance, as well as drug-drug interactions [

5].

The biological characteristics of HIV play a significant role in the formation and persistence of drug-resistant mutations [

6]. Non-polymorphic mutations are known to frequently reduce HIV fitness. In the presence of antiretroviral drugs, viruses with such mutations have an evolutionary advantage; however, discontinuation of treatment is often accompanied by their rapid disappearance and the return of the wild-type virus with higher replicative activity. A similar situation is often observed when a person is infected with a drug-resistant variant of HIV, where the original variant is replaced by the wild-type virus over the course of several months or years. Meanwhile, proviral DNA of variants with drug-resistant mutations can persist for quite a long time in latent T cells [

7]. It is impossible to detect the presence of such mutations by analyzing HIV RNA in blood plasma [

8]. After discontinuation of the ART drug to which HIV has developed drug resistance, a reservoir of resistant variants of the pathogen remains in the human body for a long time. Among patients with no ART experience, drug resistance to at least one antiretroviral drug is detected in 12.7% of cases. The average detection rate of drug resistance mutations in patients with ART failure reaches 60-80% of all samples tested.

Accessible, sensitive, and scalable technologies are needed to monitor the success of ART to eradicate HIV-1 infection. Currently used HIV-1 genotyping technologies are based on capillary sequencing. While these methods remain the gold standard for detecting clinically significant HIV drug resistance (DR) mutations, they are limited by high sequencing costs and low throughput. Capillary sequencing cannot detect mutations that are less abundant in the viral pool, also known as low-abundance drug-resistant variants [

9]. Whole-genome NGS is becoming an increasingly common method for identifying low-abundance drug-resistant variants and reducing sample costs through sample pooling and massively parallel sequencing. NGS is more sensitive because it can detect low-abundance DR variants and enables quantitative detection of DR mutations in HIV [

10]. As the number of new drugs for treating HIV-1 patients and widespread resistance increase, it is necessary to develop methods for genotyping HIV-1 with DR to detect resistance to new classes of drugs, such as capsid inhibitors, entry inhibitors, reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitors, nucleoside analogues, and Rev inhibitors. To determine mutations of resistance of HIV-1 to antiretroviral drugs, test systems based on the amplification of fragments of the HIV genome are mainly used. In laboratory practice, approaches are used that combine the amplification of fragments of the HIV genome with subsequent sequencing of the amplification products by the Illumina method. One of the few test systems registered for determining mutations of resistance of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) to antiretroviral drugs using NGS method is the Sentosa SQ HIV Genotyping Assay manufactured by Vela Diagnostics (USA). This system is based on Amplification of two regions of the HIV genome encoding the pro and int genes, as well as partially the rev gene. The resulting amplicons are then fragmented and used for library preparation and sequencing using Ion Torrent technology [

11,

12].

The aim of the study was to develop a reagent kit for identifying resistance mutations of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) to antiretroviral drugs using whole-genome sequencing and to test the developed kit in assessment of the prevalence of drug resistance of HIV-1 in adult patients with and without treatment experience in Russia in 2024–2025.

2. Materials and Methods

A non-interventional, observational, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza of the Russian Ministry of Health from January 2024 to September 2025.

2.1. Clinical Samples

A total of 1,888 clinical samples obtained from adult HIV-infected patients from 21 regions of 6 Federal Districts of the Russian Federation were studied. The majority of patients were of working age — the average median age was 42.08 years (36.69 – 47.95 years). The proportion of males was 60.86% (n=1149), females — 39.14% (n=739). The most common route of HIV transmission in the examined patients was sexual heterosexual infection (52.13%), less common was the parenteral route associated with the use of intravenous drugs (27.32%). Advanced stages of HIV infection (4A–4B) were observed in more than half of the patients. In 41.51% of cases (n=494), stage 3 HIV infection was indicated in the clinical diagnosis. In all examined samples (blood plasma) HIV-1 RNA was detected by RT-PCR. A viral load greater than 4 log10 copies/mL was observed in 90.37% of cases.

2.2. Extraction and Amplification

RNA extraction was performed from 200 ul of plasma using the Amplisens “Magno-Sorb” (Amplisens, Russia) and Ampriprime “MagnoPrime Ultra” (Nextbio, Russia) kits. Viral load in samples was determined using the AmpliPrime HIV kit (Nextbio, Russia).

2.3. Obtaining Consensus Sequences of the HIV-1 pol and env genes

Amplification of the HIV-1 pol and env genes was performed using the nested PCR principle. Each gene was covered by a single separate amplicon. For the first stage the BioMaster RT-PCR–Premium (2×) kit (Biolabmix, Russia) was used for reverse transcription and subsequent PCR in the same reaction with two pairs of HIV-specific outer primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The second round of nested PCR was performed with two pairs of inner HIV-specific primers using the BioMaster LR HS-PCR (2×) kit (Biolabmix).

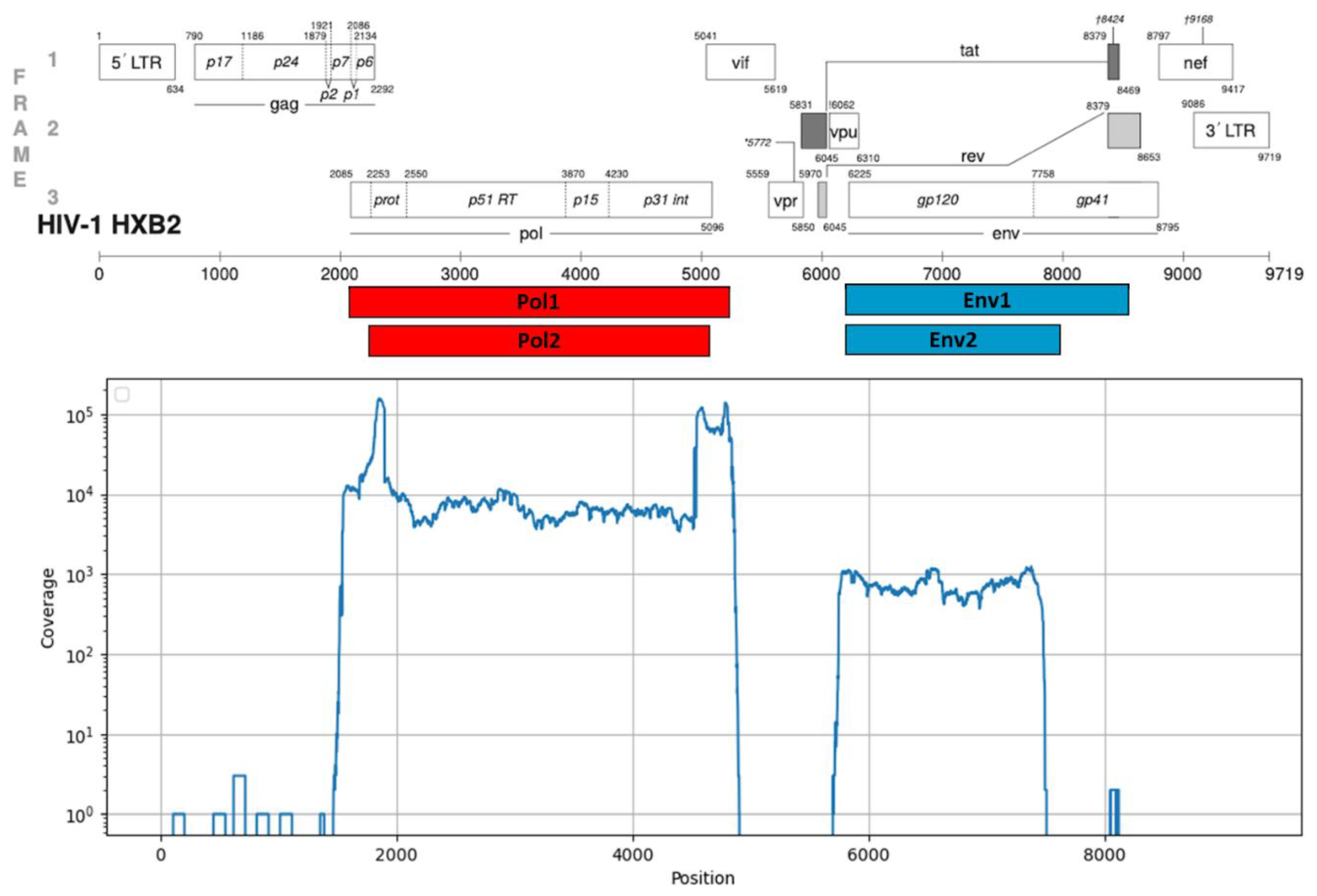

The resulting PCR products corresponded to genomic fragments with coordinates 2252-5075 and 6207-7952 (HIV-1 strain HXB2, GenBank #K03455). Positions of the amplicons in the HIV-1 reference genome are shown in

Figure 1. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Sequencing of the HIV-1 pol and env gene amplification products was performed by next-generation sequencing using MGI DNBSEQ-G400 and Illumina NextSeq 2000 instruments according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries for the MGI sequencing platform were prepared using the Fast PCR-FREE FS DNA Library Prep Set (MGI, China), and for the Illumina sequencing platform, using the Illumina DNA Prep kit (Illumina, USA). The resulting reads were quality trimmed using FastP software and consensus sequences were generated using a custom Python script combining de novo assembly using MEGAHIT and read mapping using BWA implementing the analysis principle of Shiver software[

13].

2.4. Analysis of Consensus Sequences of the HIV-1 Pol Gene

The nucleotide sequences of the

pol gene encoding HIV-1 protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase were analyzed using the local Docker based installation of Stanford University HIVdb database (version 9.7) (

https://github.com/hivdb/sierra) [

14] for the subtyping and the presence of resistance mutations with the determination of predicted levels of drug resistance to antiretroviral drugs in accordance with the WHO recommendations - the list of surveillance drug resistance mutations (SDRM, Surveillance drug resistance mutations) from 2009 [

15], and the list of surveillance mutations of drug resistance to HIV-1 integrase inhibitors from 2019 [

16]. Predicted HIV-1 resistance rates were determined for 26 antiretroviral drugs, including protease inhibitors (PIs): Atazanavir (ATV), Lopinavir (LPV), Darunavir (DRV), Fosamprenavir (FPV), Nelfinavir (NFV), Saquinavir (SQV), Tipranavir (TPV), Indinavir (IDV), NRTIs: Lamivudine (3TC), Abacavir (ABC), Stavudine (D4T), Didanosine (DDI), Emtricitabine (FTC), Tenofovir (TDF), Zidovudine (AZT), NNRTIs: Doravirine (DOR), Efavirenz (EFV), Etravirine (ETR), Rilpivirine (RPV), Nevirapine (NVP), Dapivirine (DPV), and INSTIs: Bictegravir (BIC), Dolutegravir (DTG), Cabotegravir (CAB), Elvitegravir (EVG), Raltegravir (RAL). Potentially low-level drug resistance was considered as the absence of HIV-1 resistance to the drug.

All sequences included in the study met the validation criteria for three regions encoding protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase. Nucleotide sequences containing unsequenced regions corresponding to the positions of known drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase were not included in the study. Furthermore, sequences containing more than 2 stop codons + insertions/deletions + highly ambiguous nucleotides in the protease-encoding sequence, more than 4 in the reverse transcriptase sequence, and more than 3 in the integrase sequence were not included. The maximum allowed number of APOBEC3G/F amino acid substitutions in protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase was 2, 3, and 3 substitutions, and the maximum allowed number of highly uncommon mutations was 8, 15, and 10 mutations, respectively.

2.5. Analysis of Consensus Sequences of the HIV-1 Env Gene and CXCR4 Cell Tropism Prediction

The obtained consensus nucleotide sequences of the

env gene encoding HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 were used for analysis of amino acid sequence of HIV-1 gp120 V3 loop which is a major determinant of HIV’s cell tropism, dictating whether the virus primarily infects T cells (binding to CXCR4 co-receptor) or macrophages (binding to CCR5 coreceptor). Previous benchmarks [

17] demonstrated that machine learning based methods of HIV-1 cell tropism prediction for A and C subtypes do not overperform similar empiric rules. So, a custom Python script implementing a set of empiric rules was developed [

18,

19,

20]. Briefly, the amino acid sequence of gp120 V3 loop was extracted from the output file of Sierra, and checked according to classification rules in Raynard et al [

19].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were cleaned, formalized, and analyzed using the R software environment (version 4.5.1, June 13, 2025). The median (Me) was used as a measure of central tendency to describe quantitative indicators, and the lower (LQ) and upper (HQ) quartiles were calculated as measures of data variability. Group nominal indicators are presented as feature frequencies in absolute (Abs., units) and relative (%) values. To assess differences between samples for nominal features, contingency tables were created and the Pearson chi-square test or two-tailed Fisher’s exact test were calculated. The Holm method was used to adjust for multiple hypothesis testing. The significance level was set at α ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Testing of the NGS Protocol for HIV-1 Pol and Env Genes

1888 samples with viral load in plasma starting from 3 log10 copies/mL were studied. 1521 samples were tested with primers for both

pol and

env genes and 367 samples were tested only with primers for

pol gene. 1888 (100%) sequences suitable for further analysis were obtained in total for

pol gene. 936 (61%) sequences suitable for further analysis were obtained in total for

env gene. PCR products corresponding to genomic fragments of

pol gene have coordinates 2252-5075 and of

env gene 6207-7952. Median coverage of

pol gene was about 5000 and

env gene - 700. Typical coverage distribution for a sample with both genes sequences is shown in

Figure 1.

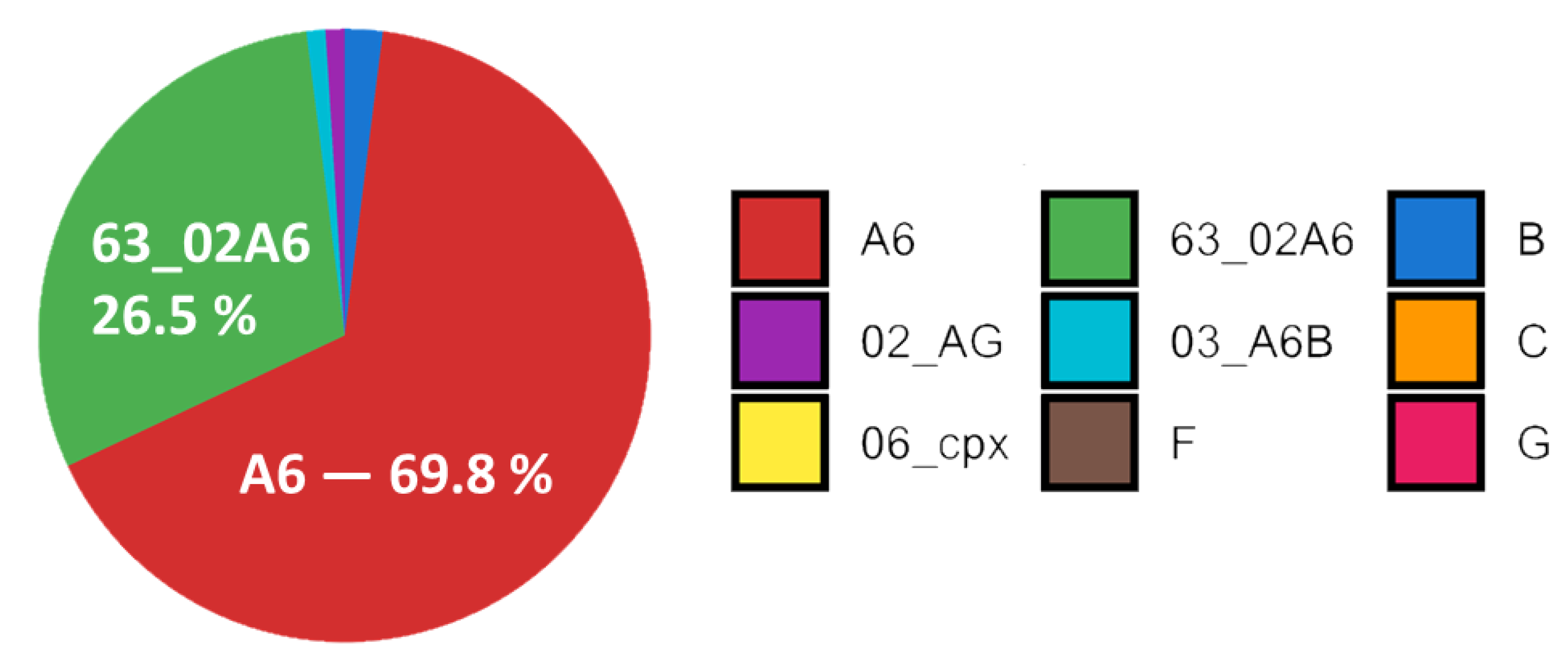

3.2. Subtyping of HIV-1 Viruses

Subtyping of HIV-1 showed the prevalence of A6 subtype (69.8% of all subtyped samples). Recombinant form 63_02A6 was the second prevalent with 26.5%. Subtypes and recombinants B (1.9%), 02_AG (0.9%) and 03_A6B (0.5%) were also found.

Subtypes C, 06_cpx, F and G represented about 0.1% of studied samples each. Subtype distribution is shown in

Figure 2.

The geographic distribution of HIV-1 subtypes across Russia was heterogeneous. A6 subtype dominated in European, Eastern Siberian and Far Eastern regions. Recombinant 63_02A6 dominated in Western Siberian region. The distribution of HIV-1 subtypes from analyzed samples is shown in

Figure 3.

3.3. Analysis of Drug Resistance Mutations

In the HIV-1 protease sequence, drug-resistance mutations were observed extremely rarely, among which the most common were M46I, K43T, and L33F (

Table 1). The surveillance mutation M46I is known to increase the catalytic activity of the protease and is associated with reduced susceptibility to ATV and LPV. In turn, the K43T and L33F substitutions are non-polymorphic accessory mutations also associated with drug resistance to ATV, LPV, and DRV. In isolated cases, surveillance mutations such as I54S/M, F53L, I47V, I54V, and M46L were observed in HIV-1 protease, primarily in patients with ART experience. The F53L mutation is a non-polymorphic accessory mutation that, in combination with others, leads to reduced susceptibility of HIV-1 to ATV. In turn, non-polymorphic mutations I54M and I54S are associated with a decrease in the susceptibility of the virus to LPV, ATV and DRV, and I54S is found predominantly in viruses with multidrug resistance to PI.

In the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase sequence, the most common NRTI drug resistance mutations were M184V/I and K65R (

Table 3). These surveillance mutations, individually and in combination, are the most common NRTI mutations arising in patients treated with first-line ART. The M184V and M184I mutations reduce HIV-1 susceptibility to 3TC/FTC by more than 200-fold, reduce susceptibility to ABC by 3-fold, and, conversely, increase viral susceptibility to AZT and TDF. In turn, the K65R mutation is accompanied by a decrease in HIV-1 susceptibility to 3TC, FTC, TDF, and ABC. The frequently occurring non-polymorphic amino acid substitution A62V and the polymorphic S68G are likely adaptation mutations and correct the viral replication deficiency associated with the K65R substitution and the Q151M and T69 insertions. The S68G substitution is known to be associated with TDF use, while the A62V mutation is predominantly found in A6 subtype viruses, which are widespread in the Russian Federation. The most common NNRTI drug resistance mutations were K103N, V90I, E138A, G190S, K101E, and Y181C (

Table 2). The surveillance mutation K103N is one of the most frequently transmitted non-polymorphic mutations conferring resistance to ART drugs. This amino acid substitution significantly reduces HIV-1 susceptibility to NVP and EFV but does not reduce susceptibility to RPV, ETR, or DOR. The E138A polymorphic mutation is associated with reduced HIV-1 susceptibility to ETR, while the G190S and Y188L non-polymorphic mutations are associated with a marked reduction in susceptibility to NVP and EFV. The surveillance non-polymorphic mutation K101E is frequently found in combination with other NNRTI resistance mutations and reduces susceptibility to NVP by 3-10 times and to EFV, ETR, and RPV by approximately 2-fold. The additional polymorphic mutation V90I does not significantly reduce viral susceptibility to any NNRTI drug, but is frequently detected in patients receiving RPV and less frequently in patients receiving NVP and EFV. A comparative analysis of the frequencies of drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase revealed that the vast majority of observed amino acid substitutions were associated with ART. Meanwhile, the S68G and E138A mutations were equally common among both treatment-naive and ART-treated patients. Surveillance mutations of resistance to NRTIs - K65R, M184V/I and NNRTIs - G190S, K101E and Y181C were practically not found among HIV-infected patients without ART experience.

Table 2.

The most common drug resistance mutations in the amino acid sequence of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase.

Table 2.

The most common drug resistance mutations in the amino acid sequence of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase.

| Mutation |

Total

(n = 1888)

Abs. / % |

ART Experience (n = 1466) |

No (n = 411)

Abs. / % |

Yes (n = 1055)

Abs. / % |

p |

| A62V |

506 / 26,80 |

64 / 15,57 |

334 / 31,66 |

< 0,001 |

| M184V1* |

234 / 12,39 |

6 / 1,46 |

210 / 19,91 |

< 0,001 |

| K103N1

|

206 / 10,91 |

28 / 6,81 |

149 / 14,12 |

0,013 |

| S68G |

176 / 9,32 |

32 / 7,79 |

114 / 10,81 |

1,000 |

| V90I |

162 / 8,58 |

20 / 4,87 |

115 / 10,90 |

0,037 |

| E138A |

158 / 8,37 |

31 / 7,54 |

91 / 8,63 |

1,000 |

| G190S1

|

135 / 7,15 |

7 / 1,70 |

116 / 11,00 |

< 0,001 |

| K65R1

|

114 / 6,04 |

0 / 0,00 |

105 / 9,95 |

< 0,001 |

| V106I |

113 / 5,99 |

9 / 2,19 |

93 / 8,82 |

0,001 |

| K101E1

|

108 / 5,72 |

5 / 1,22 |

95 / 9,00 |

< 0,001 |

| Y181C1

|

87 / 4,61 |

2 / 0,49 |

76 / 7,20 |

< 0,001 |

| M184I1

|

58 / 3,07 |

1 / 0,24 |

54 / 5,12 |

< 0,001 |

| H221Y |

46 / 2,44 |

1 / 0,24 |

41 / 3,89 |

0,002 |

| V179E |

42 / 2,22 |

4 / 0,97 |

29 / 2,75 |

1,000 |

| E138K |

36 / 1,91 |

0 / 0,00 |

31 / 2,94 |

0,004 |

| P225H1

|

34 / 1,80 |

1 / 0,24 |

31 / 2,94 |

0,037 |

| Y115F1

|

31 / 1,64 |

0 / 0,00 |

28 / 2,65 |

0,012 |

| D67N1

|

29 / 1,54 |

2 / 0,49 |

26 / 2,46 |

0,675 |

| Y318F |

28 / 1,48 |

0 / 0,00 |

26 / 2,46 |

0,019 |

The most common combinations of surveillance drug resistance mutations were combinations of two or three amino acid substitutions in the reverse transcriptase sequence. Sequences obtained from patients without ART experience very rarely contained more than one surveillance resistance mutation. In isolated cases, combinations such as G190S + K101E (0.73%, n = 3), G190S + M184V (0.73%, n = 3), K101E + M184V (0.73%, n = 3) and G190S + K101E + M184V (0.73%, n = 3) were observed. In contrast, among HIV-infected patients with ART experience, combinations of two or more surveillance mutations in reverse transcriptase were observed significantly more frequently: G190S + K101E (5.78%, n=61), G190S + M184V (5.40%, n=57), K65R + M184V (5.40%, n=57), K103N + M184V (5.21%, n=55), G190S + Y181C (5.21%, n=55) and G190S + K65R (5.40%, n=57). The most common combinations of three surveillance mutations in the group of patients with ART experience were G190S + K65R + Y181C (3.51%, n=37), G190S + K101E + Y181C (3.51%, n=37), G190S + K101E + M184V (3.32%, n=35) and G190S + K101E + K65R (3.13%, n=33).

3.4. Cell Receptor Tropism Prediction

The analysis of amino acid sequences of HIV-1 gp120 V3 loop predicted for 936 HIV-1 in our study showed that 886 viruses had no signs of possible CXCR4 tropism. 50 samples were classified as having possible CXCR4 tropism by at least one empirical rule. Different rules predicted possible CXCR4 coreceptor tropism in different samples. The results of prediction are shown in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of CXCR4 co-receptor tropism prediction using empirical rules.

Table 3.

Results of CXCR4 co-receptor tropism prediction using empirical rules.

| Rule |

Number of positive samples (proportion from the total number of samples) |

|

| A net charge rule of ≥+5 and total number of charged amino acids in V3-loop of ≥ 8 |

23 (2.5%) |

|

| Loss of the N-linked glycosylation site in V3-loop and a net charge of ≥+4 |

11 (1.2%) |

|

| R or K at position 11 and/or K at position 25 of V3-loop (11/25 rule) |

10 (1.1%) |

|

| R at position 25 of V3-loop and a net charge of ≥+5 |

5 (0.5%) |

|

Spontaneous emergence of CXCR4 co-receptor tropism along the course of HIV infection is described in literature [

21]. More than a half of analysed samples were collected from patients with late stages of HIV infection but the proportion of possible CXCR4 co-receptor tropism was significantly lower.

4. Discussion

Monitoring the emergence and patterns of antiretroviral drug resistance is crucial for the success and sustainability of treatment programs. The developed NGS-based protocol allows performing the analysis of a large number of samples in a shorter period of time and at a lower cost per sample compared to Sanger sequencing based protocols, contributing for strengthening the capacity of surveillance on HIV-1 ART resistance and cell co-receptor tropism [

9,

10].

A large-scale study was conducted to assess the prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance and multidrug resistance mutations to four classes of antiretroviral drugs simultaneously in two groups of patients, depending on their ART experience. Taking into account the constant dynamics of HIV-1 drug resistance, including that associated with the emergence of new viral variants in circulation and changes in first-line ART regimens, our data allow us to update and significantly expand the existing knowledge in this area. The results of our study are consistent with the results of studies by other authors [

22,

23,

24] and indicate a high prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance to NNRTI and NRTI drugs among patients with ART experience. The most frequently encountered surveillance mutations of drug resistance were amino acid substitutions in the reverse transcriptase sequence: M184V and K103N, with the latter being quite common among patients without ART experience. High levels of HIV-1 resistance to the most commonly used NNRTI (EFV) and NRTI (3TC, ABC) drugs in ART regimens were frequently observed. Among patients without ART experience, the highest levels of drug resistance were observed to NNRTI drugs (EFV, NVP, RPV), which indicates the possible consolidation of the corresponding resistance mutations in the reverse transcriptase sequence in the viral population, including additional adaptation mutations such as A62V, S68G and E138A.

Analysis of the sequences of three HIV-1 pol gene fragments encoding protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase simultaneously allowed us to estimate the prevalence of HIV-1 multidrug resistance to different classes of antiretroviral drugs, including combinations of individual SDRM surveillance mutations. Combinations of two or three amino acid substitutions were identified that are the most common combinations of surveillance mutations among patients with ART experience (G190S + K101E, G190S + M184V, K65R + M184V, K103N + M184V, G190S + K65R + Y181C, G190S + K101E + Y181C, and G190S + K101E + M184V). It is noteworthy that these combinations contain substitutions associated with the development of drug resistance to two classes of antiretroviral drugs simultaneously: NRTIs and NNRTIs. The most common combination of HIV-1 multidrug resistance to different classes of ART was NRTI + NNRTI resistance. Combinations of HIV-1 drug resistance to NRTIs + INSTIs, NNRTIs + INSTIs, and NRTIs + NNRTIs + INSTIs were observed significantly less frequently among treatment-experienced patients.

The most frequently observed surveillance mutations conferring drug resistance were amino acid substitutions in the reverse transcriptase sequence - M184V and K103N - with the latter being quite common among patients inexperienced with ART. High levels of HIV-1 resistance were frequently observed in the most commonly used NNRTIs (EFV) and NRTIs (3TC, ABC) in ART regimens, which may be explained by targeted viral selection in the patient’s body under drug pressure. Among patients inexperienced with ART, the highest levels of drug resistance were observed to NNRTIs (EFV, NVP, RPV), suggesting the possible persistence of the corresponding resistance mutations in the reverse transcriptase sequence, including additional adaptation mutations such as A62V, S68G, and E138A, within the viral population.

Despite the higher proportion of samples collected from patients with advanced stages of HIV-1 infection, viruses with signs of possible CXCR4 tropism were extremely rare. In our study CXCR4-tropism was predicted using five separate empirical rules resulting in 5 independent sets of possible CXCR4-tropic viruses. Different studies showed various levels of reliability and correctness of genotypic methods predicting CXCR4-tropism, depending on the HIV-1 subtype [

17,

25]. The previously used predictive algorithms were developed mostly for HIV-1 of subtype B, while in our study this subtype is observed only in 1.9% of cases. So there remains a need to further investigate and develop better predictive algorithms, especially for multiple non-B HIV-1 subtypes circulating outside of Western Europe and USA [

26].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.M., A.K. and D.L.; methodology, A.F.; software, A.F., A.M., N.Y. and V.T.; validation, A.M., V.E. and N.Y.; PCR and sequencing, K.K., A.I. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.E., A.M., A.F., M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.K., V.E., M.P., A.F.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, A.K., A.I.M., D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Ministry of Health within the framework of State assignment TVKQ-2024-0009 “Development of Whole-genome-sequencing based reagent kit for detecting mutations associated with HIV-1 resistance to antiretroviral drugs”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Protocol No. 216 of 03/18/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of Regional Centers for AIDS Prevention and Control in 21 regions of the Russian Federation for providing specimens and metadata.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDRM |

Surveillance Drug Resistance Mutations |

| ART |

Anti-Retroviral Therapy |

| PIs |

Protease inhibitors |

| NRTIs |

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| NNRTIs |

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| INSTIs |

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors |

References

- Keller SC, Yehia BR, Eberhart MG, Brady KA. Accuracy of definitions for linkage to care in persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Aug 15;63(5):622-30. PMID: 23614992; PMCID: PMC3796149. [CrossRef]

- Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, Burchell AN, Cohen M, Gebo KA, Gill MJ, Justice A, Kirk G, Klein MB, Korthuis PT, Martin J, Napravnik S, Rourke SB, Sterling TR, Silverberg MJ, Deeks S, Jacobson LP, Bosch RJ, Kitahata MM, Goedert JJ, Moore R, Gange SJ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 18;8(12):e81355. PMID: 24367482; PMCID: PMC 3867319. [CrossRef]

- Wensing AM, Calvez V, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Charpentier C, Günthard HF, Paredes R, Shafer RW, Richman DD. 2022 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top Antivir Med. 2022 Oct;30(4):559-574. PMID: 36375130; PMCID: PMC9681141.

- Puertas MC, Ploumidis G, Ploumidis M, Fumero E, Clotet B, Walworth CM, Petropoulos CJ, Martinez-Picado J. Pan-resistant HIV-1 emergence in the era of integrase strand-transfer inhibitors: a case report. Lancet Microbe. 2020 Jul;1(3):e130-e135. Epub 2020 Jun 11. PMID: 35544263. [CrossRef]

- King JR, Wynn H, Brundage R, Acosta EP. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of protease inhibitor therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(5):291-310. PMID: 15080763. [CrossRef]

- Larder B. Mechanisms of HIV-1 drug resistance. AIDS. 2001;15 Suppl 5:S27-34. PMID: 11816171. [CrossRef]

- Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997 Nov 14;278(5341):1295-300. PMID: 9360927. [CrossRef]

- Bruner KM, Wang Z, Simonetti FR, Bender AM, Kwon KJ, Sengupta S, Fray EJ, Beg SA, Antar AAR, Jenike KM, Bertagnolli LN, Capoferri AA, Kufera JT, Timmons A, Nobles C, Gregg J, Wada N, Ho YC, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Deeks SG, Bushman FD, Siliciano JD, Laird GM, Siliciano RF. A quantitative approach for measuring the reservoir of latent HIV-1 proviruses. Nature. 2019 Feb;566(7742):120-125. Epub 2019 Jan 30. PMID: 30700913; PMCID: PMC6447073. [CrossRef]

- Manyana S, Gounder L, Pillay M, Manasa J, Naidoo K, Chimukangara B. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Genotyping in Resource Limited Settings: Current and Future Perspectives in Sequencing Technologies. Viruses. 2021 Jun 11;13(6):1125. PMID: 34208165; PMCID: PMC8230827. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Ríos S, Parkin N, Swanstrom R, Paredes R, Shafer R, Ji H, Kantor R. Next-Generation Sequencing for HIV Drug Resistance Testing: Laboratory, Clinical, and Implementation Considerations. Viruses. 2020 Jun 5;12(6):617. PMID: 32516949; PMCID: PMC7354449. [CrossRef]

- Weber J, Volkova I, Sahoo MK, Tzou PL, Shafer RW, Pinsky BA. Prospective Evaluation of the Vela Diagnostics Next-Generation Sequencing Platform for HIV-1 Genotypic Resistance Testing. J Mol Diagn. 2019 Nov;21(6):961-970. Epub 2019 Aug 2. PMID: 31382033; PMCID: PMC7152740. [CrossRef]

- Raymond S, Nicot F, Abravanel F, Minier L, Carcenac R, Lefebvre C, Harter A, Martin-Blondel G, Delobel P, Izopet J. Performance evaluation of the Vela Dx Sentosa next-generation sequencing system for HIV-1 DNA genotypic resistance. J Clin Virol. 2020 Jan; 122:104229. Epub 2019 Nov 26. PMID: 31809945. [CrossRef]

- Wymant C. et al. Easy and accurate reconstruction of whole HIV genomes from short-read sequence data with shiver. Virus evolution. 2018 May; 4 (1). pp.vey007.. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/hivdb/sierra.

- Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. (2009) Drug Resistance Mutations for Surveillance of Transmitted HIV-1 Drug-Resistance: 2009 Update. PLoS ONE 4(3): e4724. [CrossRef]

- Bailey AJ, Rhee SY, Shafer RW. Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor Resistance in Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor-Naive Persons. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021 Oct;37(10):736-743. Epub 2021 Apr 15. PMID: 33683148; PMCID: PMC8665799. [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, M., Cashin, K., Budeus, B. et al. Genotypic Prediction of Co-receptor Tropism of HIV-1 Subtypes A and C. Sci Rep 6, 24883 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Esbjörnsson, J., Månsson, F., Martínez-Arias, W. et al. Frequent CXCR4 tropism of HIV-1 subtype A and CRF02_AG during late-stage disease - indication of an evolving epidemic in West Africa. Retrovirology 7, 23 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Raymond, Stéphaniea; Delobel, Pierrea; Mavigner, Mauda; Cazabat, Michellea; Souyris, Corinnea; Sandres-Sauné, Karinea; Cuzin, Lised; Marchou, Brunob; Massip, Patriceb; Izopet, Jacquesa. Correlation between genotypic predictions based on V3 sequences and phenotypic determination of HIV-1 tropism. AIDS 22(14):p F11-F16, September 12, 2008. |. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://hivfrenchresistance.org/hiv-french-resistance-hiv-tropism/.

- Sede MM, Moretti FA, Laufer NL, Jones LR, Quarleri JF (2014) HIV-1 Tropism Dynamics and Phylogenetic Analysis from Longitudinal Ultra-Deep Sequencing Data of CCR5- and CXCR4-Using Variants. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102857. [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, A.; Kireev, D.; Lapovok, I.; Shlykova, A.; Lopatukhin, A.; Pokrovskaya, A.; Bobkova, M.; Antonova, A.; Kuznetsova, A.; Ozhmegova, E.; et al. HIV-1 Drug Resistance among Treatment-Naïve Patients in Russia: Analysis of the National Database, 2006–2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 991. [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko A.A., Kireev D.E., Lopatukhin A.E., Murzakova A.V., Lapovok I.A., Ladnaya N.N., Pokrovsky V.V. Prevalence And Structure Of Hiv-1 Drug Resistance Among Treatment Naïve Patients Since The Introduction Of Antiretroviral Therapy In The Russian Federation. HIV Infection and Immunosuppressive Disorders. 2019;11(2):75-83. (In Russ.) . [CrossRef]

- Lapovok I. et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations among ART-naïve patients in Russia from 2005 to 2015. 14th European Meeting on HIV & Hepatitis, Rome, Italy. 2016. pp. 25-27.

- Singh A, Sunpath H, Green TN, Padayachi N, Hiramen K, Lie Y, Anton ED, Murphy R, Reeves JD, Kuritzkes DR, Ndung’u T. Drug resistance and viral tropism in HIV-1 subtype C-infected patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: implications for future treatment options. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Nov 1;58(3):233-40. PMID: 21709569; PMCID: PMC3196677. [CrossRef]

- Williams A, Menon S, Crowe M, Agarwal N, Biccler J, Bbosa N, Ssemwanga D, Adungo F, Moecklinghoff C, Macartney M, Oriol-Mathieu V. Geographic and Population Distributions of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 Circulating Subtypes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis (2010-2021). J Infect Dis. 2023 Nov 28;228(11):1583-1591. PMID: 37592824; PMCID: PMC10681860. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).