1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic liver disease closely associated with metabolic dysfunction, with a global prevalence of approximately 25% [

1], making it the most common chronic liver disease worldwide [

2]. In recent years, the terminology for NAFLD has been updated to metabolically dysregulated-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to reflect its association with metabolic disorders [

3,

4]. The NAFLD spectrum ranges from simple fatty liver to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which can progress to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma [

5,

6]. Notably, NAFLD not only increases the risk of liver-related diseases but is also associated with cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and certain extrahepatic cancers [

7]. Consequently, NAFLD has emerged as a major global health issue, imposing a significant socioeconomic burden [

3].

In NAFLD, excessive lipid accumulation within hepatocytes leads to lipotoxicity, which disrupts endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis and triggers ER stress. This stress, through sustained activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), causes dysregulation of hepatic lipid metabolism and exacerbates hepatic fat accumulation [

8]. ER stress activates pro-inflammatory signaling and apoptotic pathways through the UPR pathway, suppresses the expression of antioxidant enzymes, and exacerbates hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress [

9,

10]. The protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) signaling pathway is one of the three core pathways of the UPR. In NAFLD, excessive lipid accumulation activates PERK, leading to phosphorylation of its downstream signaling molecule eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α) and subsequent upregulation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) expression. Studies indicate that inhibiting the PERK pathway not only reduces ER stress but also modulates lipid metabolism, alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress [

11,

12,

13], thereby multidimensionally interfering with the pathological progression of NAFLD.

Currently, approved drugs for NAFLD are limited, necessitating a deeper understanding of disease mechanisms to develop effective therapies. The development of Mazdutide offers a potential new option in this field [

14]. Mazdutide is a dual glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucagon (GCG) receptor agonist. Activation of the GLP-1 receptor promotes insulin secretion, inhibits glucagon release, and increases satiety, whereas activation of the GCG receptor enhances energy expenditure and lipolysis [

15,

16]. Beyond weight management for obesity and type 2 diabetes, Mazdutide is being evaluated for MASLD [

14]. This study aims to preliminarily elucidate the therapeutic effects and potential mechanisms of Mazdutide on NAFLD through in vivo and in vitro experiments, thereby providing an experimental foundation and theoretical basis for the clinical application of Mazdutide and similar drugs in treating NAFLD.

2. Results

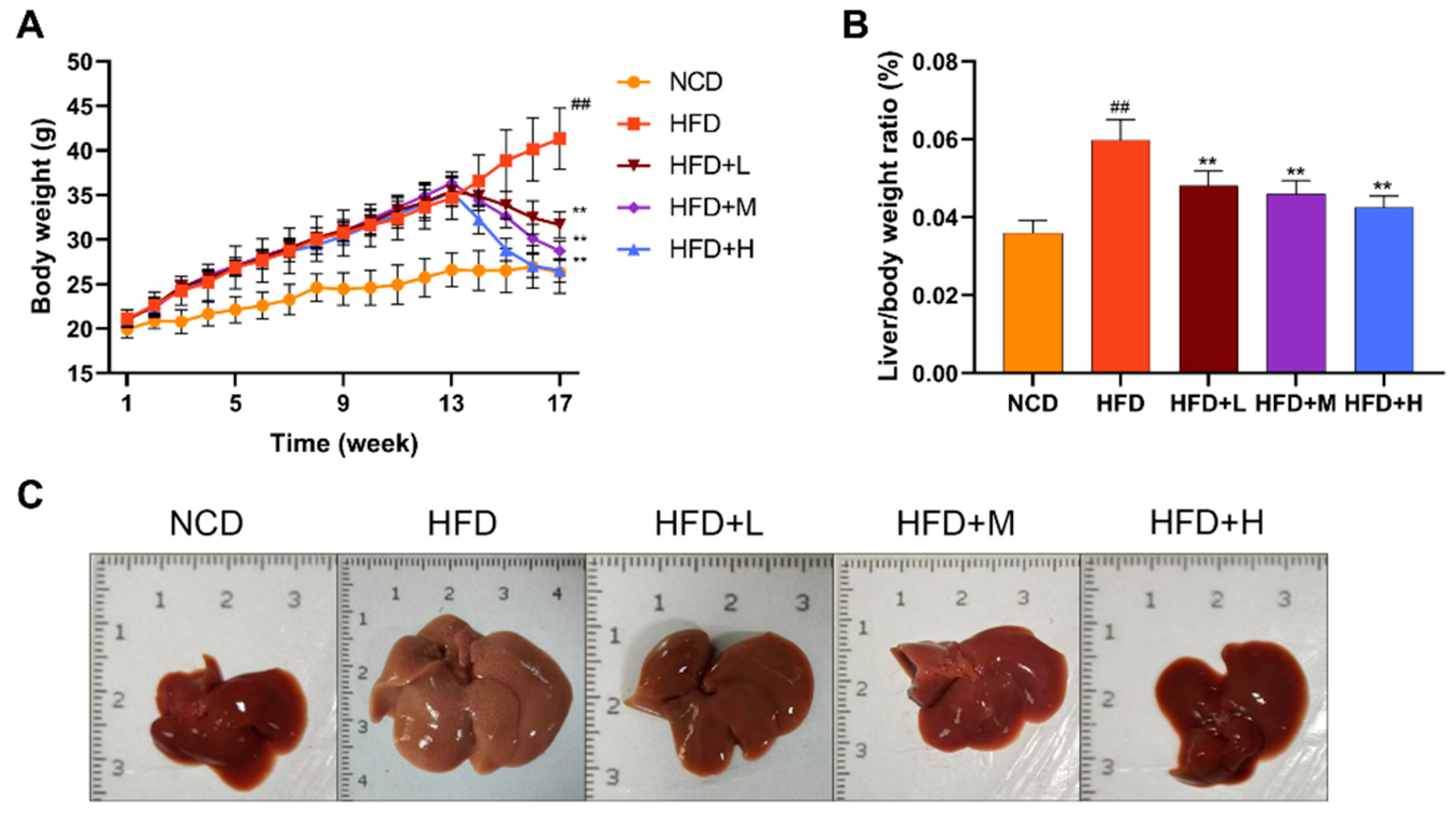

2.1. Effects of Mazdutide on Body Weight, Liver-to-Body Weight Ratio, and Liver Morphology in NAFLD Mice

The effects of Mazdutide on NAFLD progression were assessed by monitoring weekly body weight, terminal liver-to-body weight ratio, and liver morphology. After a 1-week acclimation, initial body weights were comparable across all groups. After 17 weeks, mice in the high-fat diet (HFD) group showed a significant increase in body weight compared to the normal chow diet (NCD) group. Conversely, treatment with low, medium, or high doses of Mazdutide (HFD+L/M/H) significantly attenuated this HFD-induced weight gain (

Figure 1A). Consistently, the liver-to-body weight ratio was markedly elevated in the HFD group but was significantly reduced by Mazdutide treatment at all doses (

Figure 1B). Macroscopically, livers from the NCD group displayed a normal deep-red color and texture. In stark contrast, HFD-fed mice developed pale yellow, enlarged, and friable livers with a granular surface, indicative of severe steatosis. Mazdutide treatment improved these gross morphological alterations (

Figure 1C).

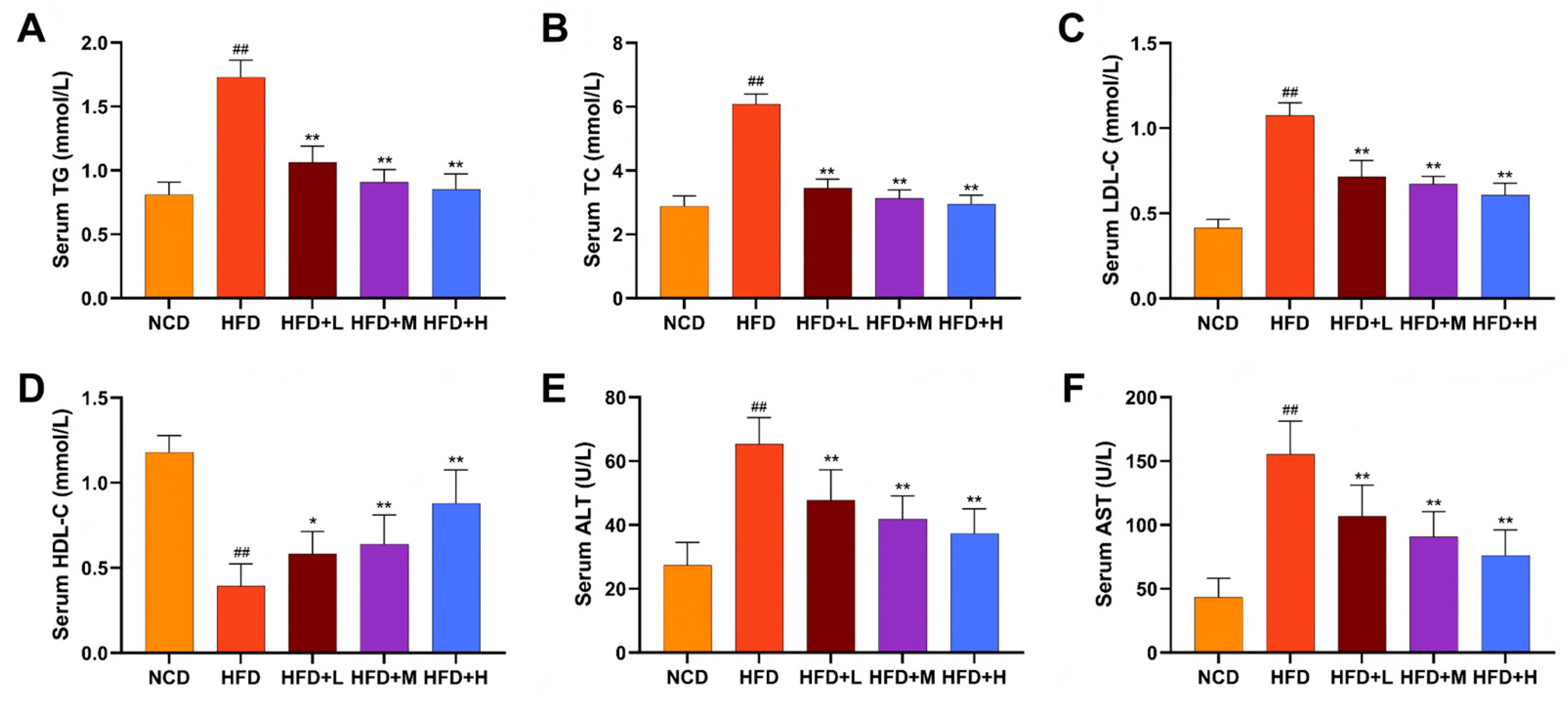

2.2. Effects of Mazdutide on Serum Lipids and Liver Enzymes in NAFLD Mice

Mazdutide's effects on lipid metabolism and hepatoprotection were evaluated by measuring serum lipid profiles and liver enzyme activities. The HFD group displayed a dyslipidemic profile, characterized by significantly elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), alongside reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), compared to the NCD group. The HFD+L/M/H group significantly reversed these HFD-induced alterations, lowering TC, TG, and LDL-C and increasing HDL-C relative to the HFD group (

Figure 2A-D). Consistently, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were markedly increased in the HFD group compared to the NCD group, indicating hepatic injury. Mazdutide treatment at all doses significantly attenuated this increase in both ALT and AST levels (

Figure 2E, F).

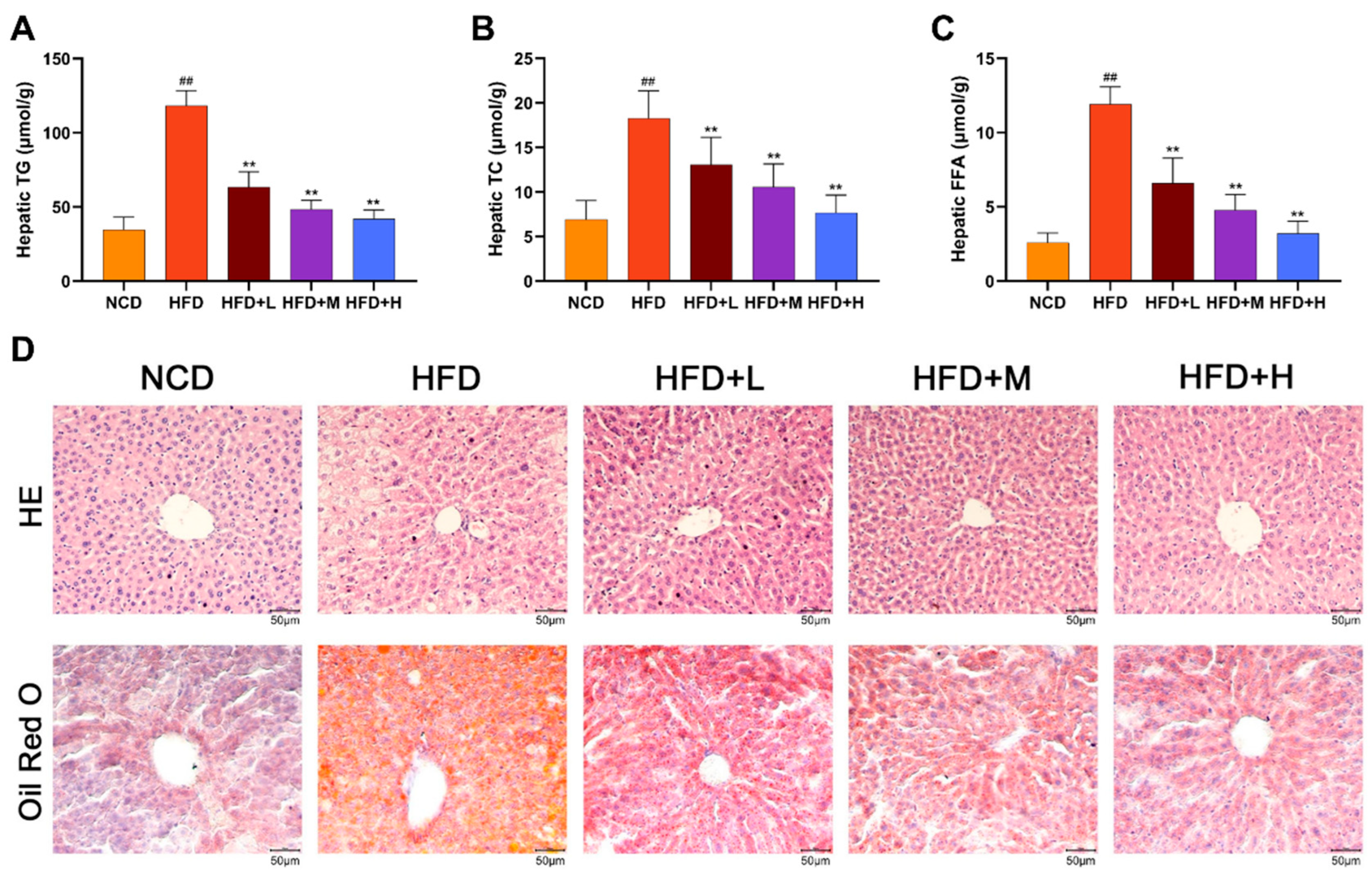

2.3. Mazdutide Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Pathological Injury in NAFLD Mice

Hepatic lipid accumulation and histopathology were assessed. Liver tissue levels of TG, TC, and free fatty acid (FFA) were significantly higher in the HFD group than in the NCD group. These lipid levels were reduced in the HFD+L/M/H group (

Figure 3A-C). Histological analysis by Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining showed normal liver architecture in the NCD group. The HFD group exhibited hepatocyte ballooning, disarray, macrovesicular steatosis (vacuolation), inflammatory infiltration, and focal necrosis. These pathological features were markedly alleviated by Mazdutide treatment, with the HFD+H showing near-normal histology. Consistently, Oil Red O staining revealed minimal lipid droplets in NCD livers, whereas HFD livers displayed extensive, dense staining indicative of severe steatosis. Mazdutide treatment significantly reduced the area and intensity of lipid droplet staining (

Figure 3D).

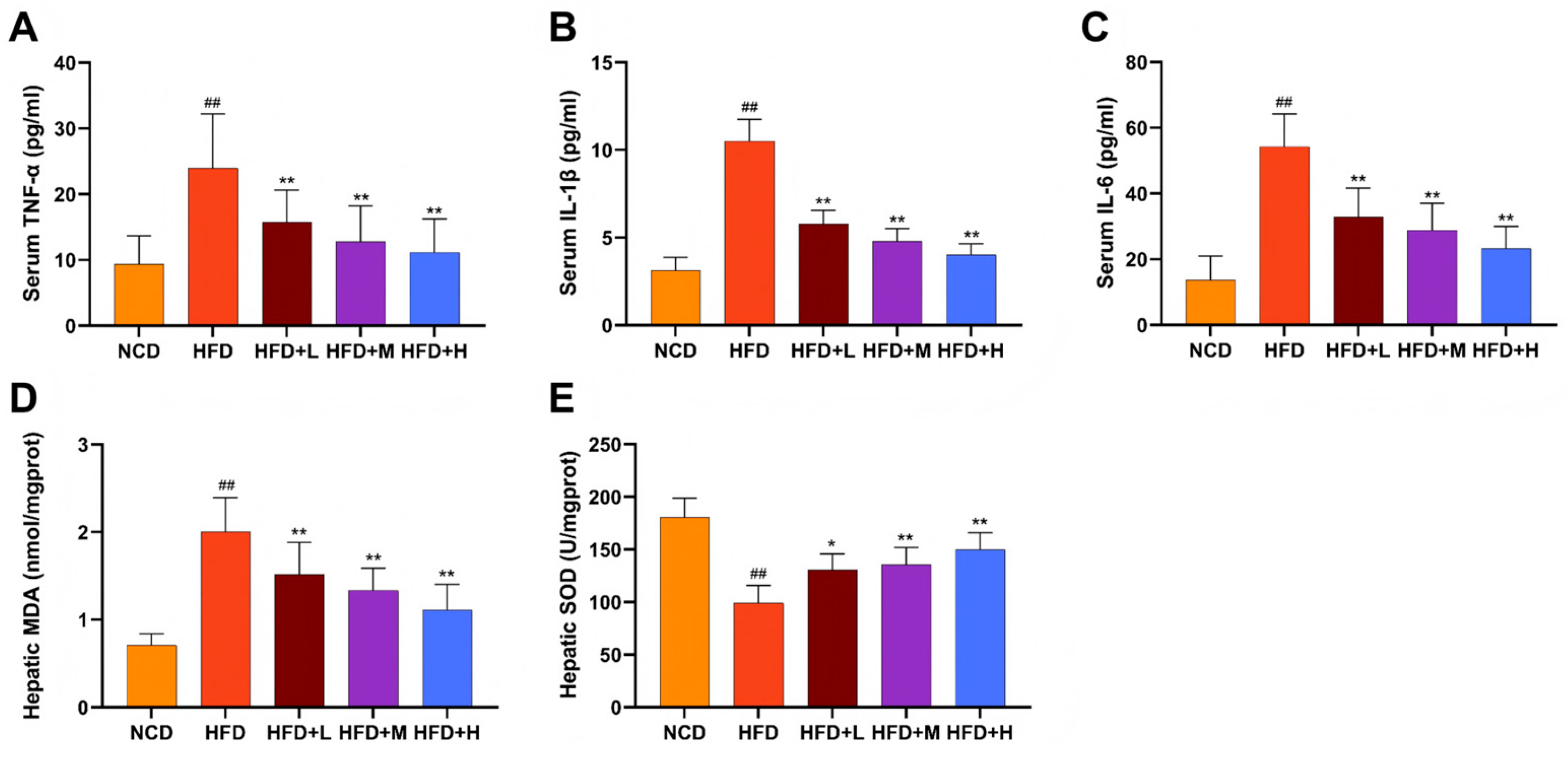

2.4. Mazdutide Alleviates Systemic Inflammation and Hepatic Oxidative Stress in NAFLD Mice

Serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) were significantly elevated in the HFD group compared to the NCD group. Mazdutide treatment significantly reduced the levels of all three cytokines (

Figure 4A-C). Consistently, hepatic oxidative stress was markedly induced by HFD, as evidenced by increased malondialdehyde (MDA) content and decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Mazdutide administration reversed these alterations, significantly lowering MDA levels and enhancing SOD activity compared to the HFD group (

Figure 4D, E).

2.5. Mazdutide Suppresses ER Stress via the PERK Pathway in NAFLD Mouse Liver Tissue

To assess ER stress, we analyzed key markers by immunohistochemistry and Western blot. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positive staining for GRP78 and CHOP in the HFD group, which was visibly attenuated in all Mazdutide-treated groups compared to the HFD group (

Figure 5A). Western blot analysis confirmed these findings. Protein levels of the ER chaperone GRP78 were significantly elevated in the HFD group compared to the NCD group. Furthermore, key components of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP branch were markedly activated in the HFD group, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation levels of PERK (p-PERK/PERK ratio) and eIF2α (p-eIF2α/eIF2α ratio), along with upregulated protein expression of ATF4 and its downstream target CHOP. Mazdutide treatment reversed these HFD-induced increases, significantly reducing the phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α and downregulating the protein levels of GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP compared to the HFD group (

Figure 5B, C).

2.6. Mazdutide Downregulates Hepatic Inflammation and Lipogenesis in a Mouse Model of NAFLD

Hepatic expression of key inflammatory and lipogenic proteins was assessed by Western blot (

Figure 6). Compared to the NCD group, the HFD group showed a significant increase in the ratio of phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa-B p65 (p-NF-κB p65) to total NF-κB p65 (p-NF-κB p65/NF-κB p65) and the protein level of TNF-α, indicating activation of the NF-κB pathway. Concurrently, the expression of lipogenic transcription factors—sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ)—was also significantly elevated in the HFD group. Treatment with Mazdutide significantly reversed these HFD-induced changes. Compared to the HFD group, the p-NF-κB p65/NF-κB p65 ratio and the expression levels of TNF-α, SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ were all significantly downregulated in the liver.

2.7. Mazdutide Reduces Lipid Accumulation in an NAFLD Cell Model and Informs Concentration Selection

An in vitro NAFLD model was established in Alpha Mouse Liver-12 (AML-12) cells using 1 mM FFA (FFA group), with a medium-only group serving as the control (Cont). Cells were co-treated with 1 mM FFA and varying concentrations of Mazdutide (5nM–1μM). Compared to the Cont group, intracellular TG levels were significantly increased by FFA, but were markedly reduced by Mazdutide at concentrations ranging from 5 nM to 200 nM (

Figure 7A), with the most pronounced reductions observed at 10, 20, and 50 nM. Similarly, Oil Red O staining demonstrated that lipid droplet accumulation induced by FFA was visibly diminished by Mazdutide at 5 nM to 200 nM (

Figure 7B), most notably at 10, 20, and 50 nM. The 50 nM treatment restored cell morphology most closely to that of the Cont group. Based on these results, 10 nM (low), 20 nM (medium), and 50 nM (high) Mazdutide were selected for subsequent experiments.

2.8. Mazdutide Mitigates Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in NAFLD Cells

Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers were quantified in the NAFLD cell model. Compared to the Cont group, the FFA group exhibited significantly elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, alongside decreased SOD activity and increased MDA content. These FFA-induced alterations were significantly reversed by co-treatment with low-dose Mazdutide (Maz-L), medium-dose Mazdutide (Maz-M), high-dose Mazdutide (Maz-H), or ER stress inhibitor 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) (

Figure 8).

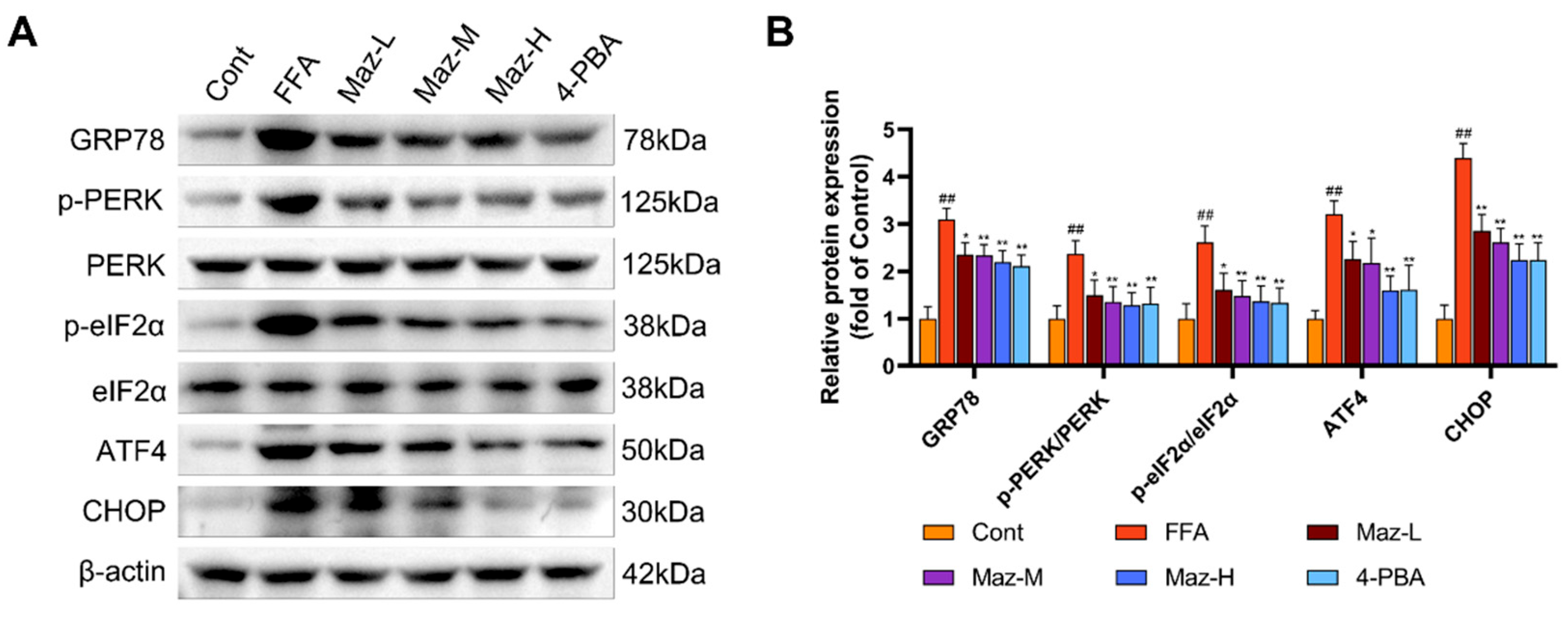

2.9. Mazdutide Inhibits the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP Pathway in NAFLD Cells

Western blot analysis of key ER stress markers demonstrated that FFA challenge robustly activated the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway in hepatocytes. This activation was evidenced by a significant upregulation of GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP, alongside increased phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α, relative to the Cont group. Notably, co-treatment with Mazdutide (at low, medium, or high doses) or the chemical chaperone 4-PBA effectively mitigated this stress response, with all intervention groups exhibiting markedly attenuated expression of these proteins compared to the FFA model group (

Figure 9).

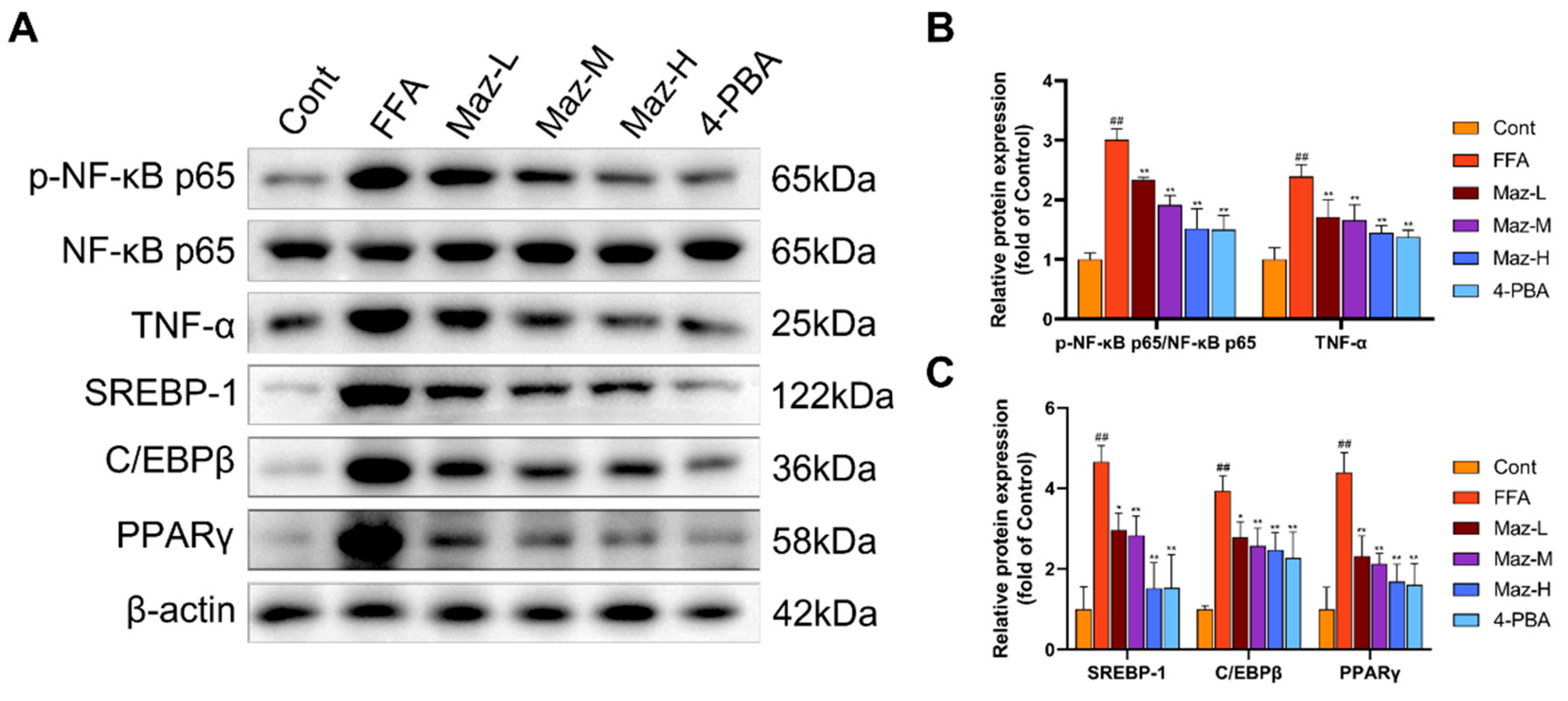

2.10. Mazdutide Reduces the Expression of Inflammation and Lipid Metabolism-Related Proteins in NAFLD Cells

Western blot analysis revealed that FFA treatment simultaneously activated pro-inflammatory and lipogenic pathways in hepatocytes. Specifically, it significantly enhanced NF-κB pathway activity, evidenced by an increased p-NF-κB p65/NF-κB p65 ratio, and upregulated the expression of the downstream cytokine TNF-α and the key lipogenic regulators SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ, compared to the Cont group. Importantly, co-administration of Mazdutide (at low, medium, or high doses) or the ER stress inhibitor 4-PBA effectively countered these changes, significantly attenuating NF-κB activation and reducing the expression of TNF-α, SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ (

Figure 10).

3. Discussion

NAFLD, recently reclassified as MASLD, represents the most prevalent chronic liver disorder globally, posing a significant public health burden. The current lack of targeted pharmacotherapies underscores an urgent need for effective and safe intervention strategies. Mazdutide, a dual GLP-1 and GCG receptor agonist, has shown efficacy in weight reduction and glycemic control. However, its therapeutic potential and precise molecular mechanisms in NAFLD/MASLD remain insufficiently defined [

14]. This study utilized an HFD-induced murine NAFLD model to replicate common unhealthy dietary patterns. Concurrently, an in vitro NAFLD model was established by treating AML-12 cells with FFA at a final concentration of 1 mM, composed of oleic acid (OA) and palmitic acid (PA) in a 2:1 molar ratio, mimicking the imbalanced fatty acid milieu observed in patients. We systematically evaluated the therapeutic effects of Mazdutide on NAFLD and explored its underlying mechanisms, thereby providing preclinical evidence to support its clinical translation.

Our findings demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy of Mazdutide against NAFLD at both organismal and cellular levels. NAFLD progression typically involves hepatic lipid accumulation, hepatocyte injury, and impaired liver function, frequently accompanied by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress—a spectrum of pathologies recapitulated in our models [

17]. HFD-fed mice exhibited significant amelioration of dyslipidemia and liver function abnormalities in both hepatic tissue and serum following a 4-week Mazdutide treatment regimen. Histopathological analysis further revealed that Mazdutide markedly reduced hepatic steatosis, lipid droplet deposition, and inflammatory cell infiltration [

18,

19]. Consistent results were obtained in vitro: Mazdutide co-treatment significantly decreased MDA levels, elevated SOD activity, and reduced the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in FFA-induced hepatocytes. Collectively, these data indicate that Mazdutide enhances hepatic antioxidant capacity, mitigates lipid peroxidation damage, and suppresses systemic and local inflammatory responses associated with NAFLD [

20,

21].

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is intricately linked to ER stress. Evidence suggests that excessive hepatic lipid accumulation disrupts ER homeostasis, leading to aberrant activation of the UPR [

22,

23]. The ER, a central organelle for protein folding, lipid transfer, and calcium storage, responds to dysfunction by upregulating the stress sensor GRP78, subsequently activating downstream pathways such as PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP [

8]. In investigating Mazdutide's mechanism of action, we found that it significantly downregulated the expression of GRP78 and key components of the PERK branch in both liver tissues and hepatocytes. This suppressive effect mirrored that of the chemical ER stress inhibitor 4-PBA, indicating that Mazdutide alleviates hepatic ER stress by restraining overactivation of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP axis, thereby contributing to NAFLD improvement.

Chronic ER stress is known to propel NAFLD progression by driving lipid synthesis and inflammation [

24]. SREBP-1, a master transcriptional regulator of lipogenesis, promotes hepatic lipid accumulation primarily by activating downstream lipogenic enzymes [

25,

26]. ER stress indirectly modulates SREBP-1 maturation and nuclear translocation through the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP axis [

27,

28]. C/EBPβ occupies a central node in hepatic lipid accumulation and metabolic dysregulation, directly regulating lipogenic genes, mediating inflammatory responses, and facilitating intercellular communication [

29,

30]. Under ER stress conditions, the enhanced chromatin-binding capacity of C/EBPβ may exacerbate lipid metabolic disturbances [

31]. PPARγ is a key regulator of lipid storage and glucose metabolism; its hepatic upregulation is strongly associated with steatosis [

32,

33]. Activation of the PERK pathway under nutrient excess promotes PPARγ nuclear translocation and the expression of its target genes [

34,

35]. Thus, PERK serves as a critical nexus linking ER stress to lipid metabolism by influencing the activity of SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ [

36]. Furthermore, ER stress can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway via PERK [

37], and NF-κB activation may establish a vicious cycle that perpetuates both metabolic dysfunction and ER stress [

38,

39]. In the present study, Mazdutide significantly downregulated the lipogenic transcription factors SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ, reduced the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and the expression of TNF-α protein, thereby decreasing de novo lipogenesis and alleviating hepatic inflammation. This coordinated downregulation, comparable to the effect of 4-PBA, demonstrates that Mazdutide improves lipid metabolism and counters chronic inflammation by mitigating ER stress, ultimately retarding NAFLD progression.

In summary, our study elucidates that Mazdutide exerts multifaceted protective effects against NAFLD. It effectively alleviates hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Mechanistically, we found that Mazdutide suppresses excessive ER stress by inhibiting the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway, thereby inhibiting its associated lipogenesis and inflammation. These findings position Mazdutide as a promising therapeutic candidate targeting the integrated pathogenic network of ER stress in NAFLD.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Mazdutide acetate was purchased from Abmole Bioscience Inc. (Houston, TX, USA). TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, ALT, AST, MDA, and SOD assay kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The FFA assay kit was purchased from Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Mouse TNF-α, mouse IL-1β, and mouse IL-6 ELISA kits were purchased from Jonln Bio (Shanghai, China). Oleic acid (OA), fatty acid- free and IgG-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), and BCA protein concentration assay kits were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Palmitic acid (PA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 4-PBA was purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Primary antibodies for GRP78, ATF4, CHOP, and β-actin were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc (Wuhan, China). Antibodies for SREBP-1, C/EBPβ, and PPARγ were purchased from ZEN-BIOSCIENCE Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Antibodies for eIF2α and p-eIF2α(Ser51) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies for PERK, p-PERK(T892), NF-κBp65, p-NF-κBp65(Ser536), and TNF-α were purchased from Wanlei Life Sciences (Shenyang) Co., Ltd. (Shenyang, China). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

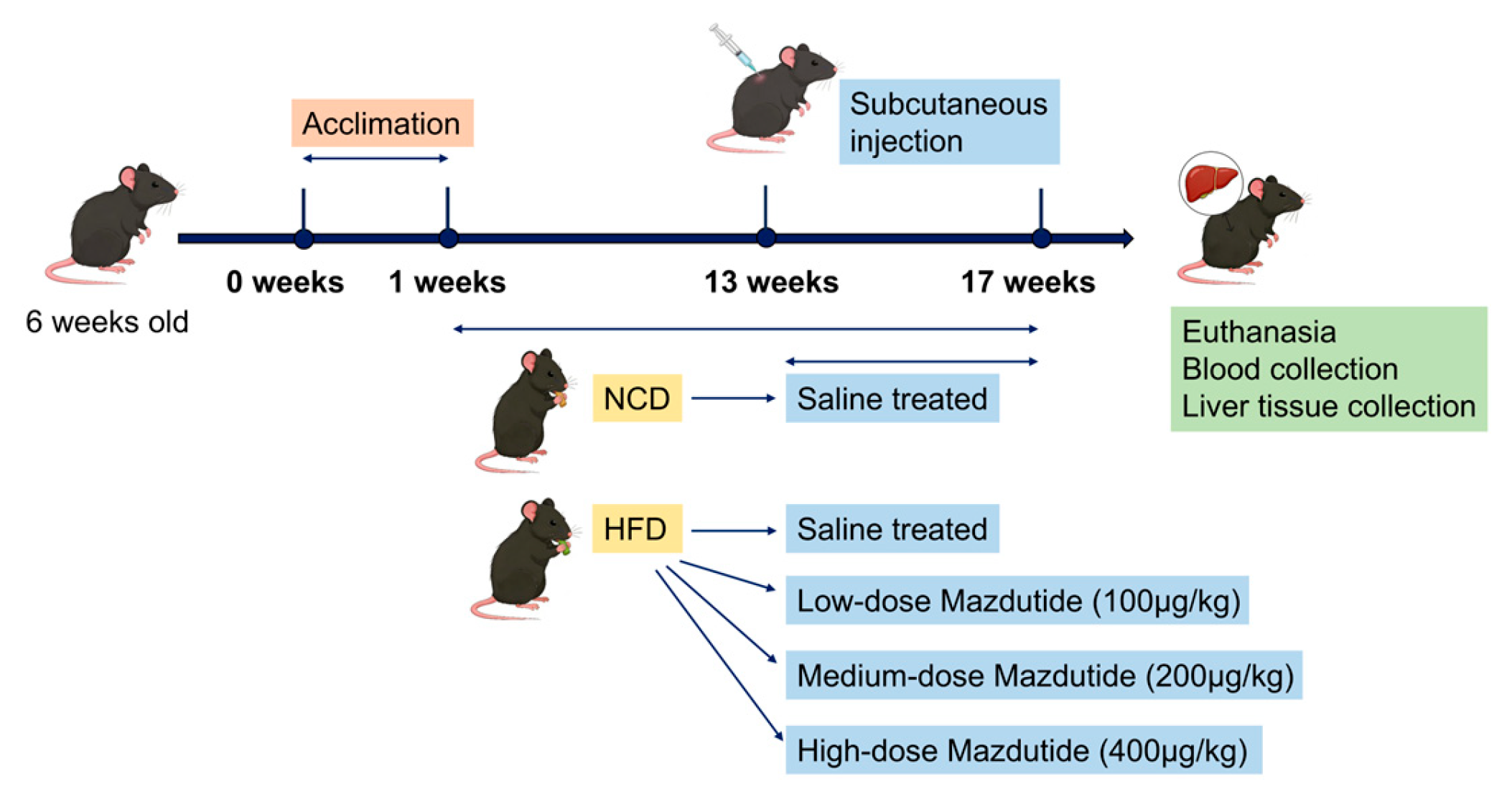

4.2. Animals and Treatment

Six-week-old male C57BL/6J mice [

40,

41] were purchased from Henan Skobes Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Anyang, China) and housed in a constant temperature (22±2°C) and humidity (40-60%) environment under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Mice had free access to chow and drinking water. Mice were randomly divided into five groups (n=15 per group). Following a 1-week acclimation, the normal chow diet (NCD) group and the high-fat diet (HFD, #D12492) group were established [

40,

41]. After 12 weeks, Mazdutide was administered subcutaneously every 3 days for 4 weeks to three HFD-fed groups: the high-fat diet low-dose group (HFD+L, 100 μg/kg), the high-fat diet medium-dose group (HFD+M, 200 μg/kg), and the high-fat diet high-dose group (HFD+H, 400 μg/kg) [

42]. The NCD and HFD groups received equivalent volumes of saline. At the end of the treatment, all mice were euthanized for the collection of blood and liver samples. A schematic diagram of the animal experiment design was drawn (

Figure 11).

4.3. Preparation of FFA

PA and OA were individually dissolved in sodium hydroxide (NAOH) solution at a molar ratio of 1:1 (fatty acid:NaOH). Solubilization was facilitated by incubation in a 70 °C water bath, followed by dilution of each fatty acid into 10% fatty acid-free and IgG-free BSA solution. The resultant PA and OA stock solutions were sterile-filtered through 0.22 μm membranes, aliquoted, and stored at -80 °C in the dark. For experimental use, the working FFA solution was freshly prepared by mixing PA and OA stocks at a molar ratio of 1:2 [

43].

4.4. Cell Culture and Grouping

AML-12 cell line, an immortalized and non-transformed hepatocyte line, was purchased from Zhongqiaoxinzhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). AML-12 cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, insulin-transferrin-selenium mixture, 0.1 mM dexamethasone, penicillin, and streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO₂. TG content was measured after co-treating AML-12 cells with varying Mazdutide concentrations (5 nM–1 μM) and 1 mM FFA for 24 hours. Lipid droplet formation was visualized via Oil Red O staining. The optimal Mazdutide concentrations for improving lipid accumulation—10 nM, 20 nM, and 50 nM—were selected as low, medium, and high doses, respectively. AML-12 cells were divided into six experimental groups: the control (Cont) group, treated with medium alone; the FFA group, to establish a high-fat model via treatment with 1 mM free fatty acids; three Mazdutide intervention groups co-treated with 1 mM FFA and low- (10 nM), medium- (20 nM), or high-dose (50 nM) Mazdutide, designated as Maz-L, Maz-M, and Maz-H, respectively; and the 4-PBA group, co-treated with 1 mM FFA and 1 mM 4-PBA.

4.5. Biochemical Parameter Detection

Serum levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, ALT, and AST were measured using commercially available biochemical assay kits according to the manufacturers' instructions. The levels of TG, TC, FFA, MDA, and SOD in 10% mouse liver tissue homogenate were detected according to the kit manufacturer's instructions. Similarly, the levels of TG, MDA, and SOD in AML-12 cell lysate were detected according to the kit manufacturer's instructions.

4.6. Inflammatory Cytokine Assay

Inflammatory markers in mouse serum and AML-12 cell culture supernatants, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, were detected using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.7. HE Staining

Liver tissues from corresponding sites in each group of mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, then routinely processed and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned at 5 μm thickness using a rotary microtome. For HE staining, the sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Subsequently, the sections were stained with hematoxylin for 10 min, differentiated in 1% acid ethanol for 30 s, and blued in running water for 10 min. This was followed by eosin staining for 5 min. Finally, the stained sections were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, mounted with a neutral resin, and examined under an upright transmitted light microscope (Olympus BX41) for morphological assessment.

4.8. Oil Red O Staining

4.8.1. Tissue Staining

Mouse liver tissues from corresponding sites were embedded in O.C.T. compound, cryopreserved at -80°C, and sectioned at 10 μm using a cryostat. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and washing, sections were stained with freshly filtered Oil Red O working solution (3:2 stock:water) for 20 min in the dark. Sections were then differentiated in 60% isopropanol, rinsed, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Following bluing in water, sections were mounted with glycerol-gelatin medium and examined by the Olympus BX41 microscope. Lipid droplets within hepatocytes were identified as orange-red deposits.

4.8.2. Cell Staining

AML-12 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Upon reaching 60-70% confluence, the cells were co-treated with an FFA solution and various concentrations of Mazdutide for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and then stained using the same Oil Red O staining protocol as described for tissue sections (

Section 4.8.1). Finally, the stained cells were washed, and images were acquired using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer 3) in bright-field mode.

4.9. Immunohistochemical Staining

Paraffin-embedded mouse liver sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3% H₂O₂ and nonspecific sites with 5% BSA, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against GRP78 or CHOP (1:500). Following incubation with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200), immunoreactivity was visualized using a DAB kit. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Sections were then dehydrated, cleared, mounted, and examined under an upright light microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE E100). Positive expression was identified by yellow-brown cytoplasmic or nuclear granules.

4.10. Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from liver tissues and hepatocytes using RIPA buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Concentrations were determined by BCA assay. Equal protein amounts were denatured, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in TBST, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Following TBST washes, bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Data from ≥3 independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD. Multiple group comparisons used one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. p < 0.05 was statistically significant. Western blot band intensities were quantified via ImageJ densitometry and normalized to β-actin.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our findings indicate that Mazdutide significantly ameliorates HFD- and FFA-induced NAFLD by suppressing ER stress (via the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP axis) and its associated lipid metabolism (SREBP-1/C/EBPβ/PPARγ) and inflammatory (NF-κB/TNF-α) pathways. This finding provides new experimental evidence for the molecular mechanism by which Mazdutide ameliorates NAFLD.

Author Contributions

L.G.: conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization. L.D.: resources, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. X.Z.: methodology, software, validation, investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170606).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the national standard Guidelines for Ethical Review of Laboratory Animal Welfare (GB/T 35892-2018) of China. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Animal Laboratory of Henan University of Science and Technology (2025061303) on 5 March 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to the College of Basic Medicine and Forensic Medicine at Henan University of Science and Technology for their support with instruments and equipment. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used DeepSeek-V3.2 for the purposes of polishing the language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAFLD |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| MASLD |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

| UPR |

Unfolded protein response |

| PERK |

Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| eIF2α |

Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha |

| ATF4 |

Activating transcription factor 4 |

| CHOP |

C/EBP homologous protein |

| GLP-1 |

Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GCG |

Glucagon |

| HFD |

High-fat diet |

| NCD |

Normal chow diet |

| TC |

Total cholesterol |

| TG |

Triglycerides |

| LDL-C |

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-C |

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| ALT |

Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| FFA |

Free fatty acid |

| HE |

Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| SOD |

Superoxide dismutase |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| SREBP-1 |

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 |

| C/EBPβ |

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta |

| PPARγ |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| AML-12 |

Alpha Mouse Liver-12 |

| 4-PBA |

4-phenylbutyric acid |

References

- Drummer, C., IV; Saaoud, F.; Jhala, N.C.; Cueto, R.; Sun, Y.; Xu, K.; Shao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Shen, H.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Wu, S.; Snyder, N.W.; Hu, W.; Zhuo, J.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, X. Caspase-11 promotes high-fat diet-induced NAFLD by increasing glycolysis, OXPHOS, and pyroptosis in macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkseven, S.; Turato, C.; Villano, G.; Ruvoletto, M.; Guido, M.; Bolognesi, M.; Pontisso, P.; Di Pascoli, M. Low-Dose Acetylsalicylic Acid and Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Mitoquinone Attenuate Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Mice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Fan, J.G.; Francque, S.M. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2024, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Han, E.; Lee, H.W.; Park, C.Y.; Chung, C.H.; Lee, D.H.; Cho, E.H.; Rhee, E.J.; Yu, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Bae, J.C.; Park, J.H.; Choi, K.M.; Kim, K.S.; Seo, M.H.; Lee, M.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, W.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Choi, Y.K.; Lee, Y.H.; Hwang, Y.C.; Lyu, Y.S.; Lee, B.W.; Cha, B.S. Fatty Liver Research Group of the Korean Diabetes Association. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review and Position Statement of the Fatty Liver Research Group of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Mehal, W.Z.; Ouyang, X. RNA modifications in the progression of liver diseases: from fatty liver to cancer. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 2105–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiseler, M.; Schwabe, R.; Hampe, J.; Kubes, P.; Heikenwälder, M.; Tacke, F. Immune mechanisms linking metabolic injury to inflammation and fibrosis in fatty liver disease - novel insights into cellular communication circuits. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1136–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikat, R.; Nguyen, M.H. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and non-liver comorbidities. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, s86–s102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, M.; Kim, J.Y. Endoplasmic reticulum stress at the forefront of fatty liver diseases and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in innate immune cells - a significant contribution to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 951406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; An, L.; Liu, Y.; Qu, H.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Yin, Y.; Ma, Q. Vitamin E Mitigates Apoptosis in Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Inhibiting Zearalenone-Induced Activation of the PERK/eIF-2α/ATF4/Chop Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 28390–28399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Hua, Q.; Pei, S.; Yue, Z.; Liang, H.; Zhang, H. Preventive Effect of Apple Polyphenol Extract on High-Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis in Mice through Alleviating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3172–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wei, Y.; Yu, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, S.; Zhao, L.; Ding, L.; Cheng, J.; Feng, H. Erythritol Improves Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Activating Nrf2 Antioxidant Capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13080–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Fang, F.; Shi, S.; Jiang, X.; Dong, Y.; Li, X. Microglia-derived IL-1β promoted neuronal apoptosis through ER stress-mediated signaling pathway PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP upon arsenic exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Mazdutide: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Bai, J.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, H. Mazdutide, a dual agonist targeting GLP-1R and GCGR, mitigates diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction: mechanistic insights from multi-omics analysis. EBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, G.W. Shared mechanistic pathways of glucagon signalling: Unlocking its potential for treating obesity, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, and other cardio-kidney-metabolic conditions. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 6869–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, L.; Dudley, K.; Xiao, L.; Huang, G.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Chen, C.; Crawford, R.; Xiao, Y. Three-Dimensional Dynamic Cell Models for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Progression. BME Front. 2025, 6, 0181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Cho, Y.; Son, S.M.; Hur, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Oh, H.; Lee, H.Y.; Jung, S.; Park, S.; Kim, I.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, C.S. Activin E is a new guardian protecting against hepatic steatosis via inhibiting lipolysis in white adipose tissue. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Yang, K.; Shen, Z.; Jia, K.; Liu, P.; Pan, M.; Sun, C. ER stress-induced adipocytes secrete-aldo-keto reductase 1B7-containing exosomes that cause nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 163, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhan, B.; Wang, Z.; Feng, H. Total Extract of Folium Rhododendri Daurici alleviate MASLD by regulating PPAR and TNF signaling pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2026, 358, 120955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Polyzos, S.A. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Ren, Z.; Cai, N.; Ai, H.; Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shuai, X.; He, X.; Shi, G.; Chen, Y. Secreted MUP1 that reduced under ER stress attenuates ER stress induced insulin resistance through suppressing protein synthesis in hepatocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 187, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Xiao, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhao, F. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic avenues. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, B.; Meng, M.; Zhao, W.; Wang, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Xiong, X.; Bian, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Hu, C.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y. FOXA3 induction under endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ding, C.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Yu, C.; Peng, C.; Feng, X.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, W.; Lu, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J.; Zheng, S. ACSL4 reprograms fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma via c-Myc/SREBP1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2021, 502, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, H. Lipogenesis and MASLD: re-thinking the role of SREBPs. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Zhang, X.; Dai, X.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, J.; Yuan, F. The SDF-1α/MTDH axis inhibits ferroptosis and promotes the formation of anti-VEGF-resistant choroidal neovascularization by facilitating the nuclear translocation of SREBP1. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2025, 41, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.K.; Jo, S.H.; Lee, E.S.; Ha, K.B.; Park, N.W.; Kong, D.H.; Park, S.I.; Park, J.S.; Chung, C.H. DWN12088, A Prolyl-tRNA Synthetase Inhibitor, Alleviates Hepatic Injury in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Baek, J.H.; Lee, J.; Sivaraman, A.; Lee, K.; Chun, K.H. Deubiquitinase USP1 enhances CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) stability and accelerates adipogenesis and lipid accumulation. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonfeld, M.; Nataraj, K.; Weinman, S.; Tikhanovich, I. C/EBPβ transcription factor promotes alcohol-induced liver fibrosis in males via HDL remodeling. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, G.; Schonfeld, M.; Saleh, S.; Parrish, M.; Barmanova, M.; Weinman, S.A.; Tikhanovich, I. Sepsis-induced endothelial dysfunction drives acute-on-chronic liver failure through Angiopoietin-2-HGF-C/EBPβ pathway. Hepatology 2023, 78, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Jia, T.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.; Huang, P. Short term exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics in mice evokes self-regulation of glycolipid metabolism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Chen, C.; Zhao, W. Soybean soluble polysaccharide prevents obesity in high-fat diet-induced rats via lipid metabolism regulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 3057–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Shen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Monroig, Ó.; Zhu, T.; Sun, P.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, M. Fucoidan alleviates hepatic lipid deposition by modulating the Perk-Eif2α-Atf4 axis via Sirt1 activation in Acanthopagrus schlegelii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.S. Organophosphorus pesticides exert estrogen receptor agonistic effect determined using Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PBTG455, and induce estrogen receptor-dependent adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 283, 117090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: bridging inflammation and obesity-associated adipose tissue. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1381227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, D.Y.; Xu, Q.Y.; He, Y.; Zheng, X.Q.; Yang, T.C.; Lin, Y. Treponema pallidum protein Tp47 induced prostaglandin E2 to inhibit the phagocytosis in human macrophages. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heida, A.; Gruben, N.; Catrysse, L.; Koehorst, M.; Koster, M.; Kloosterhuis, N.J.; Gerding, A.; Havinga, R.; Bloks, V.W.; Bongiovanni, L.; Wolters, J.C.; van Dijk, T.; van Loo, G.; de Bruin, A.; Kuipers, F.; Koonen, D.P.Y.; van de Sluis, B. The hepatocyte IKK: NF-κB axis promotes liver steatosis by stimulating de novo lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 54, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Shi, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S. The role of inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity-related cognitive impairment. Life Sci. 2019, 233, 116707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Wang, H.; Pan, X.; Little, P.J.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): pathomechanisms and pharmacotherapies. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5681–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster-Martínez, I.; Català-Senent, J.F.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Roig, F.J.; Esplugues, J.V.; Apostolova, N.; García-García, F.; Blas-García, A. Integrated transcriptomic landscape of the effect of anti-steatotic treatments in high-fat diet mouse models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Pathol. 2024, 262, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W.; Bai, J.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, H. Mazdutide, a dual agonist targeting GLP-1R and GCGR, mitigates diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction: mechanistic insights from multi-omics analysis. EBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Tian, Y.; Huang, J.; Deng, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gao, L.; Xie, Q.; Yu, Q. Metformin Alleviates Liver Metabolic Dysfunction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome by Activating the Ethe1/Keap1/PINK1 Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 3505–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).