Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Reagents

2.2. HIV-1 Replication Assay

2.3. Quantitation of C1q, and CXCL9 in Culture Supernatants

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

2.5. Reactive Oxygen Species

2.6. Phagocytosis Assay

2.7. Autophagy Assay

2.8. Western Blotting

2.9. Construction of scRNA-Seq Libraries

2.10. Analysis of scRNA-Seq

2.11. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

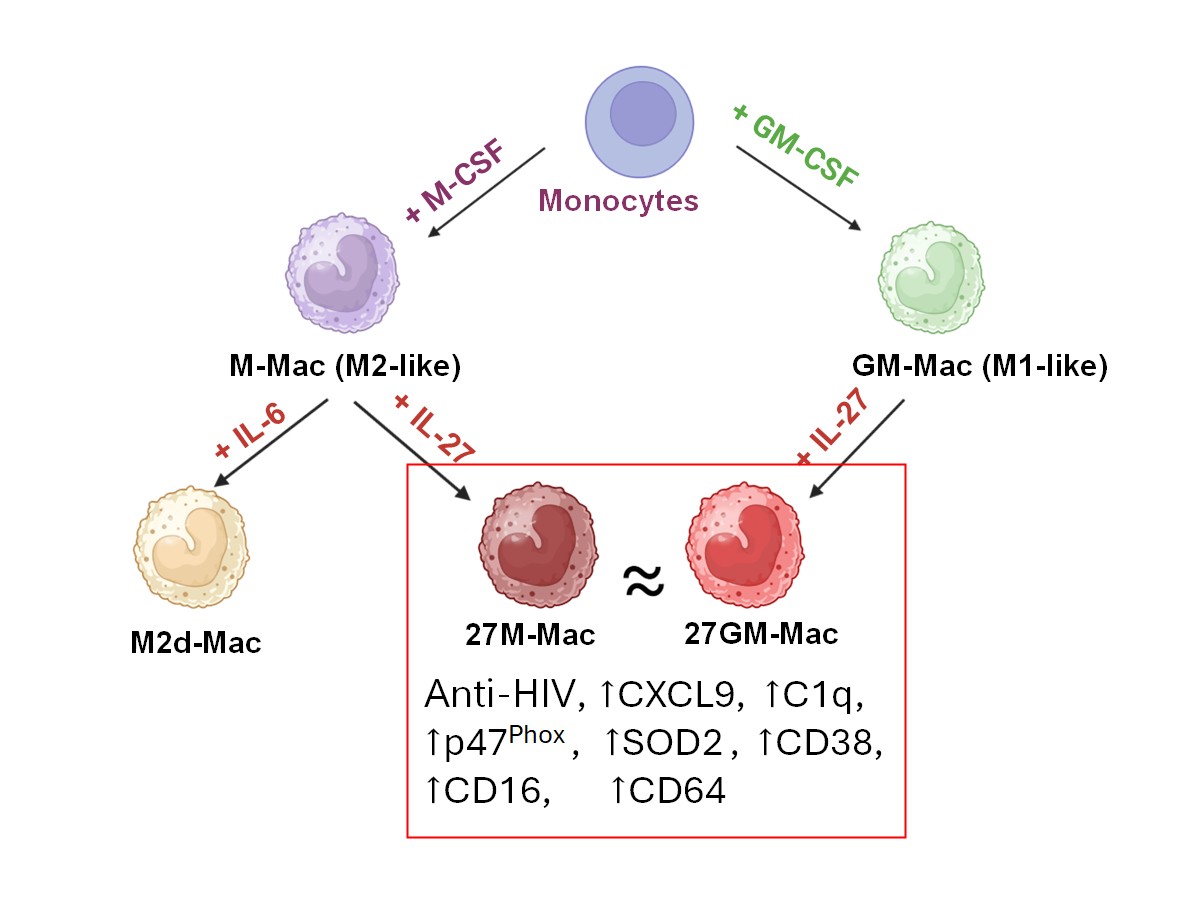

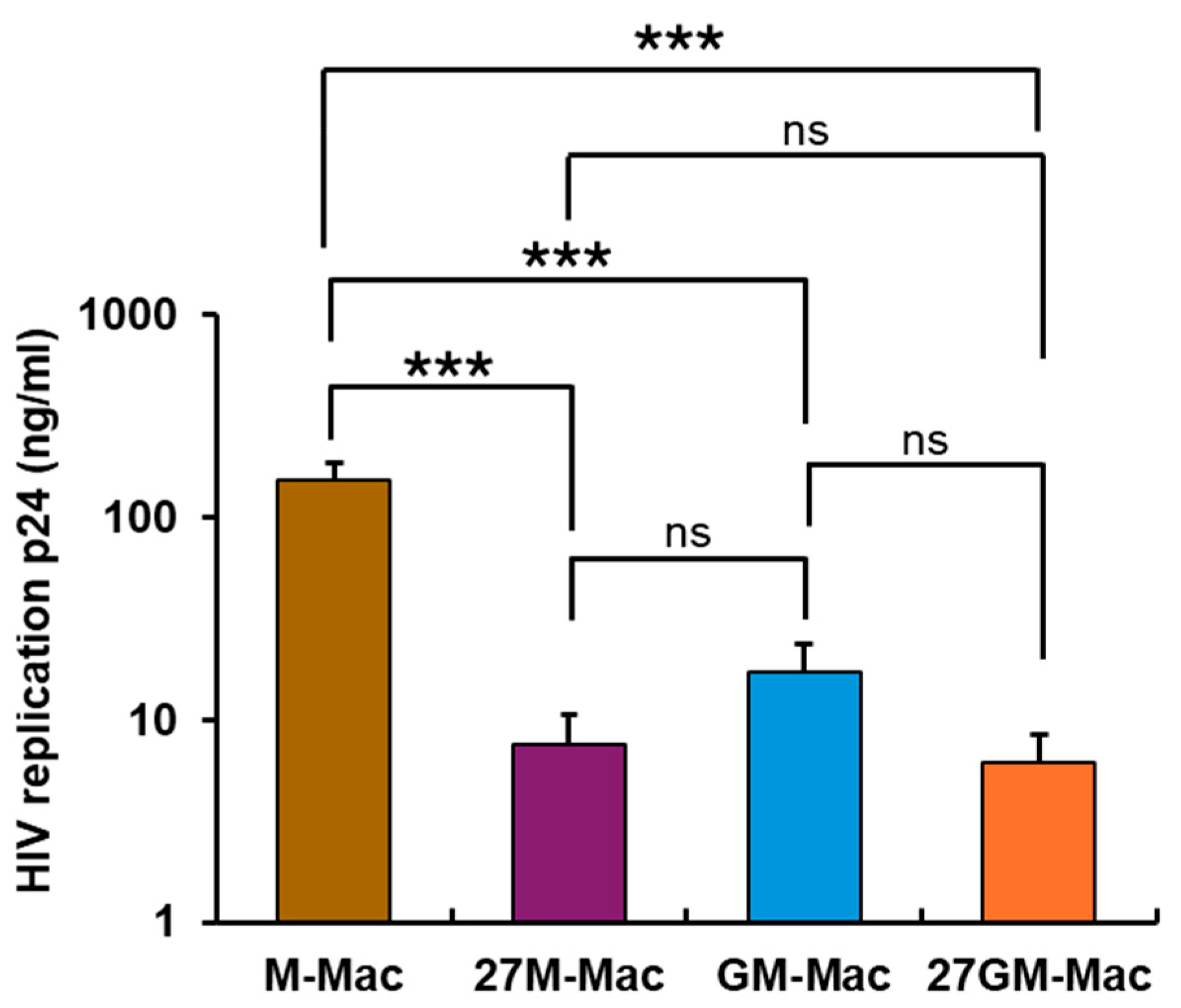

3.1. Antiviral Effect

3.1.1. Comparison of Anti-HIV Activity

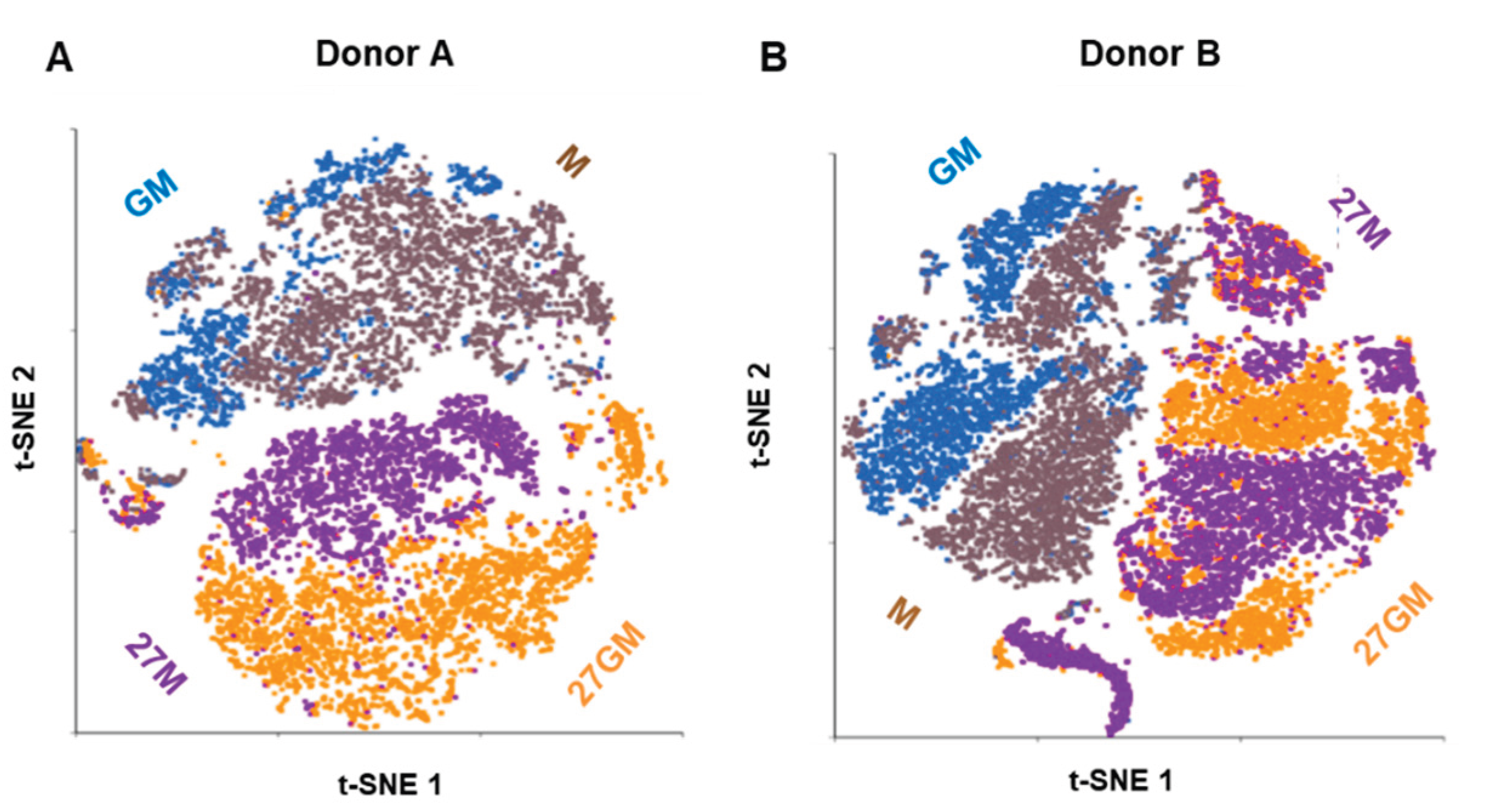

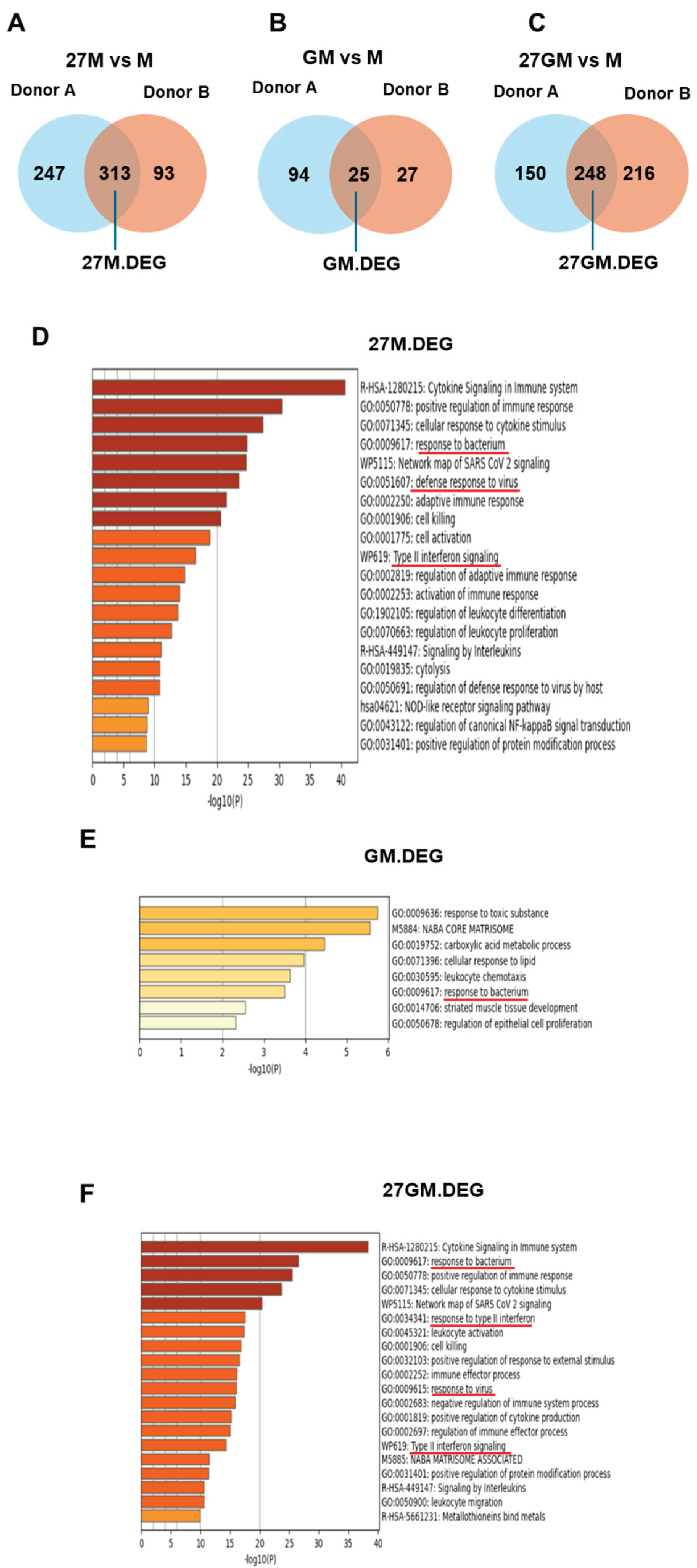

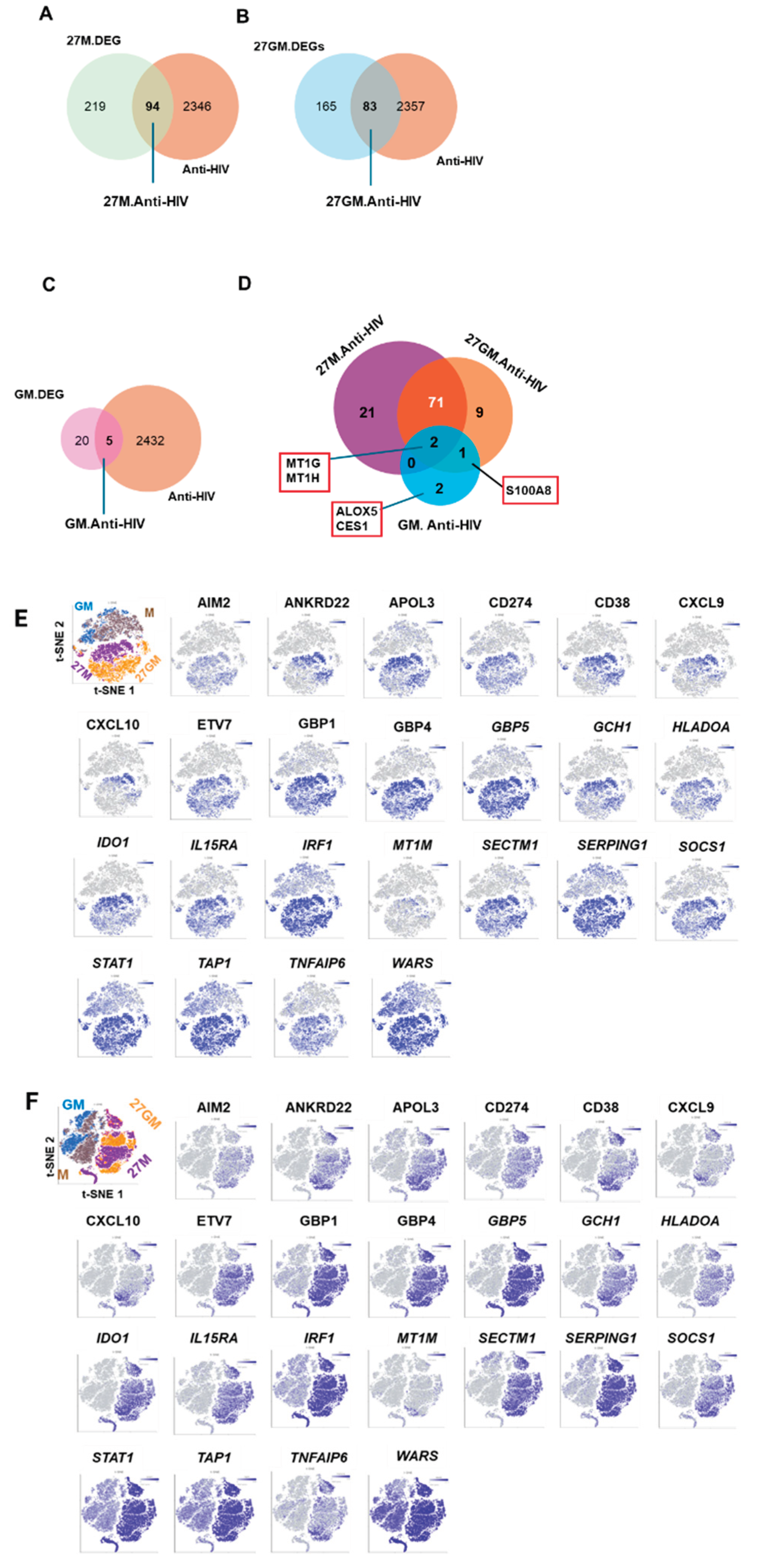

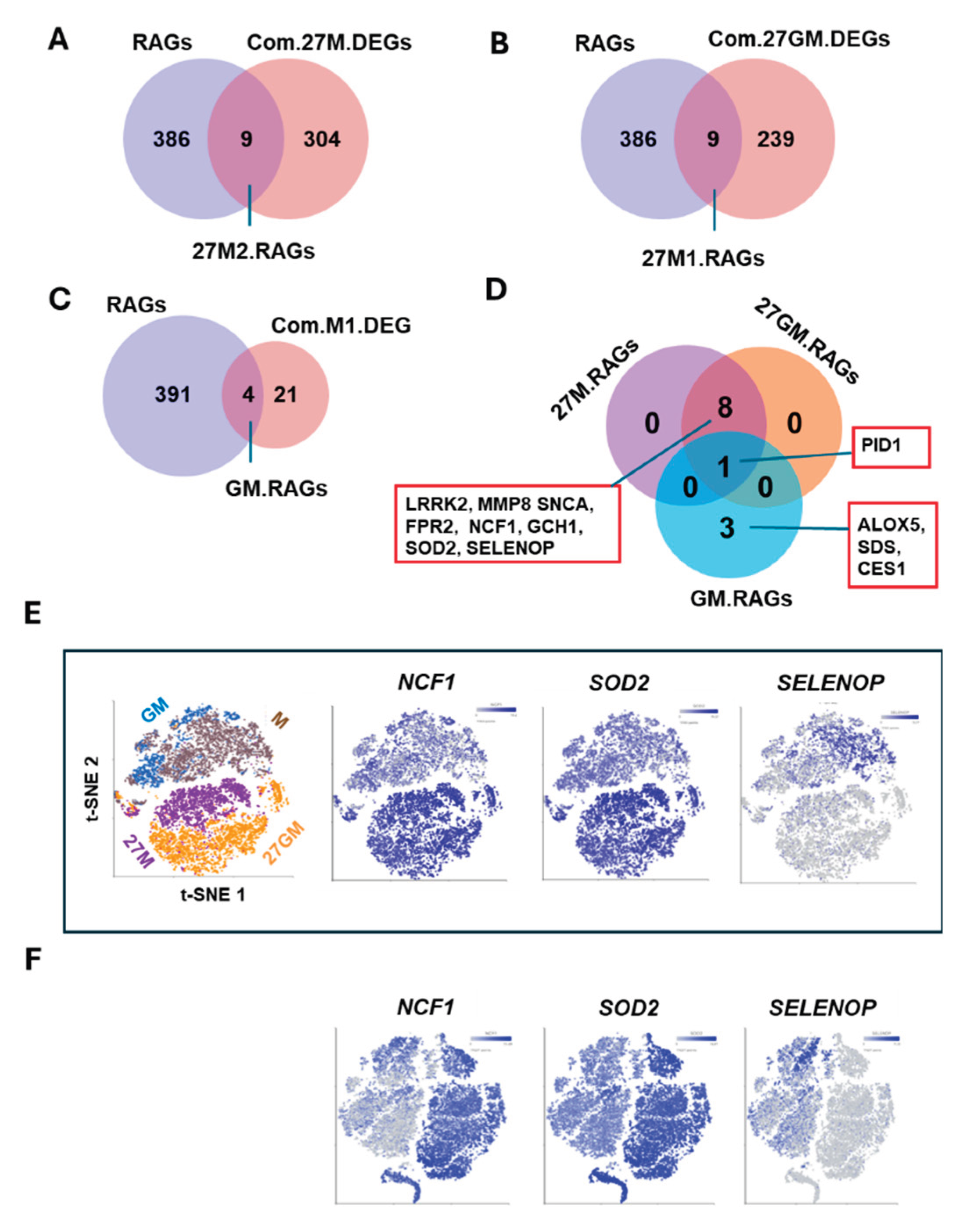

3.1.2. Comparison of Gene Expression Among Four Cell Types

3.1.3. Potential Mechanisms Underlying Anti-HIV Activity

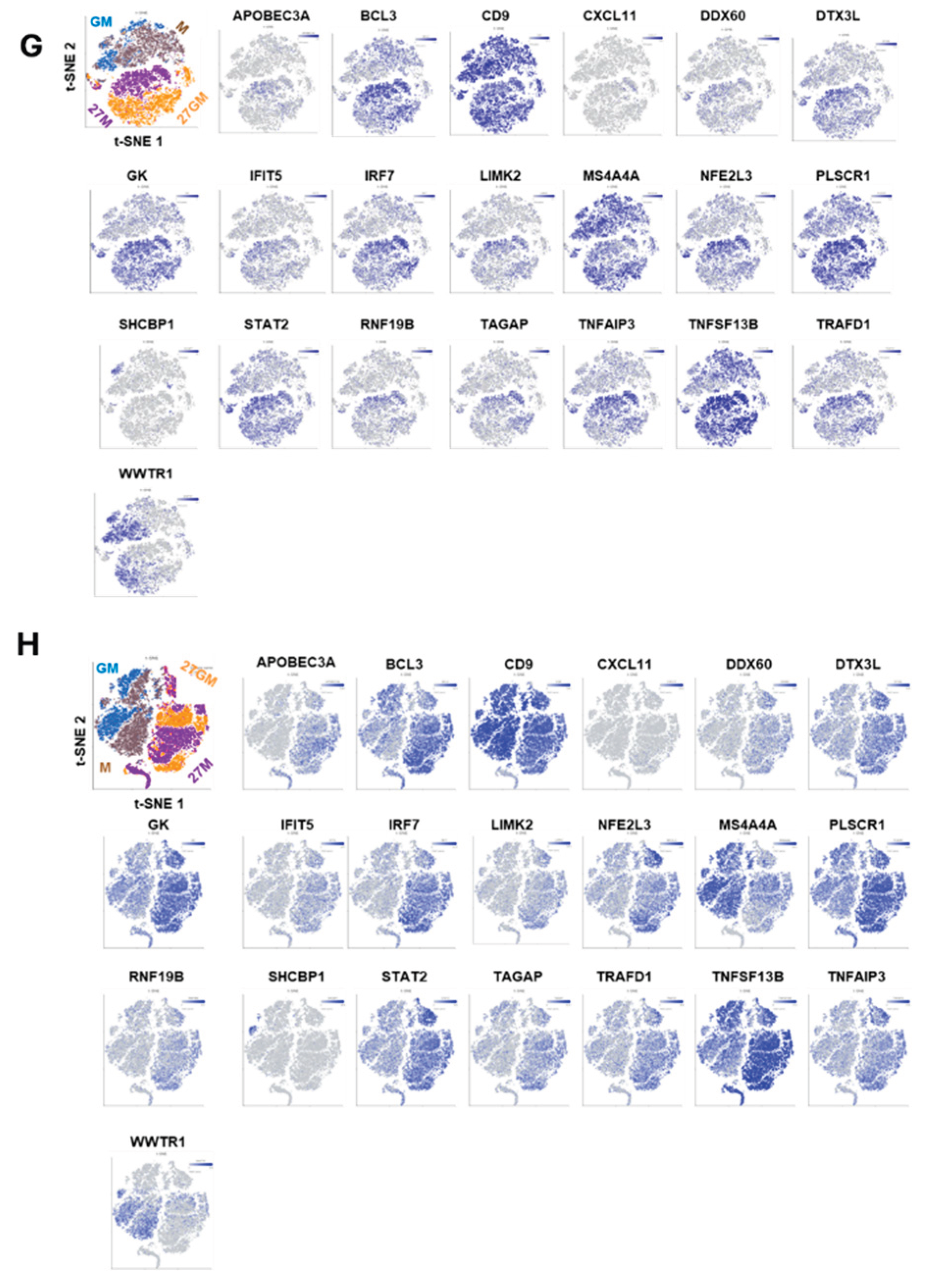

3.2. CD38 Expression and CXCL9 and C1q Production

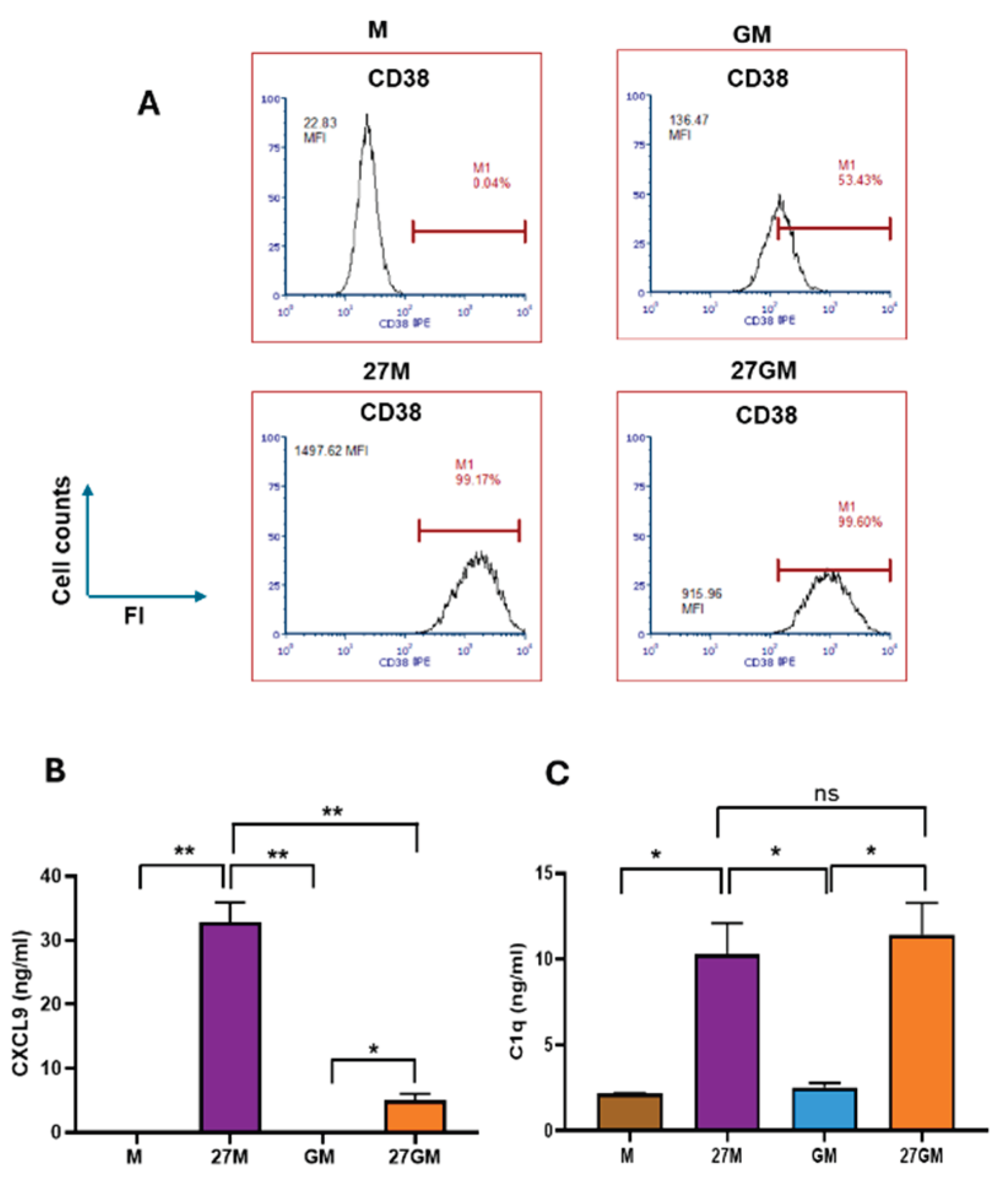

3.3. Macrophage Marker Expression

3.4. ROS-Inducing Activity

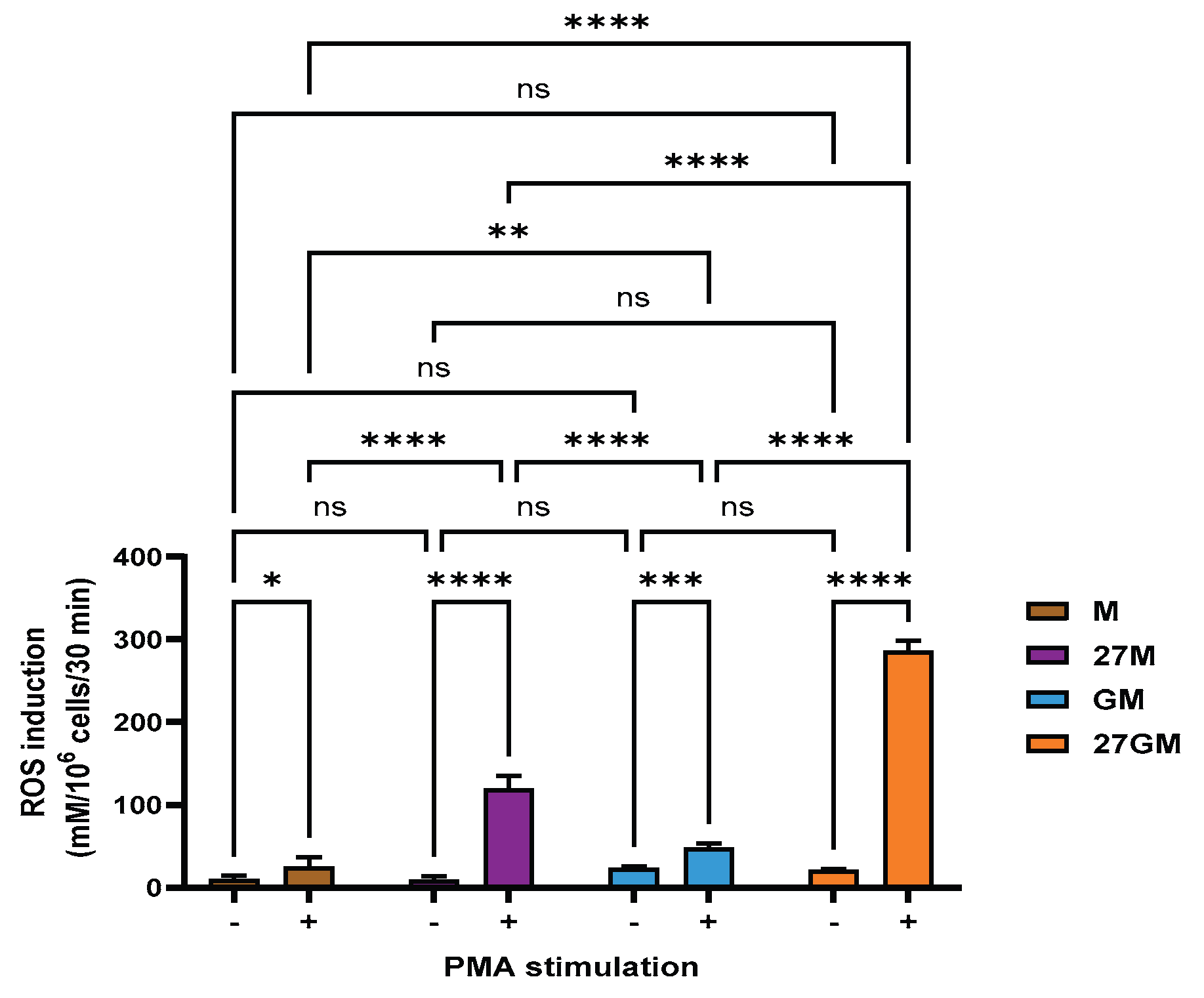

3.4.1. Comparison of ROS-Inducing Activity

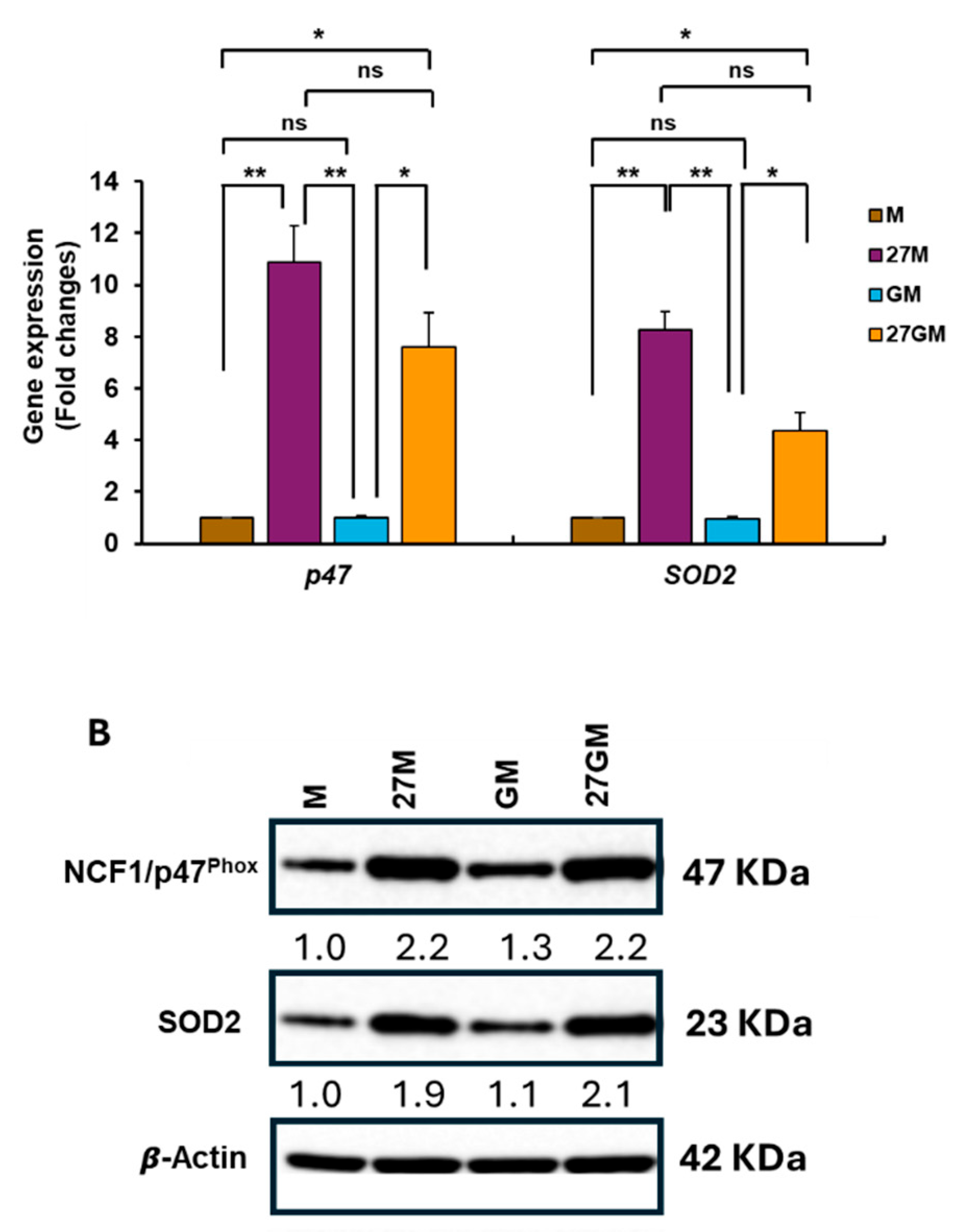

3.4.2. Mechanisms Underlying Enhanced ROS Production

3.5. Phagocytosis Activity

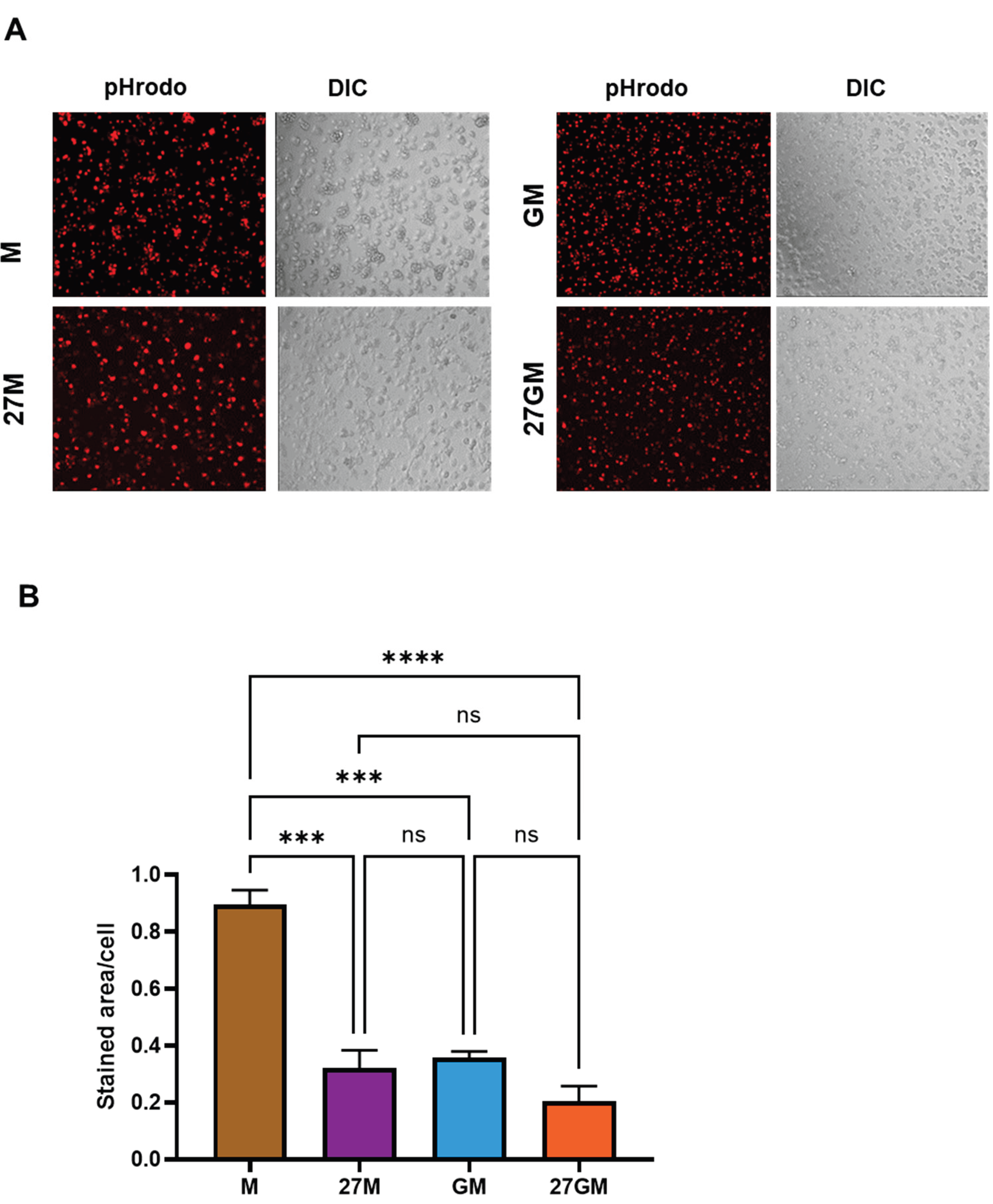

3.5.1. Comparison of Phagocytic Activity

3.5.2. Potential Mechanisms Regulating Phagocytosis

3.6. Autophagy Induction

3.6.1. Comparison of Autophagy-Inducing Activity

3.6.2. Potential Mechanism Underlying Autophagy Regulation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATGs | autophagy-related genes |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| DYSF | dysferlin |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| FPR2 | formyl peptide receptor 2 |

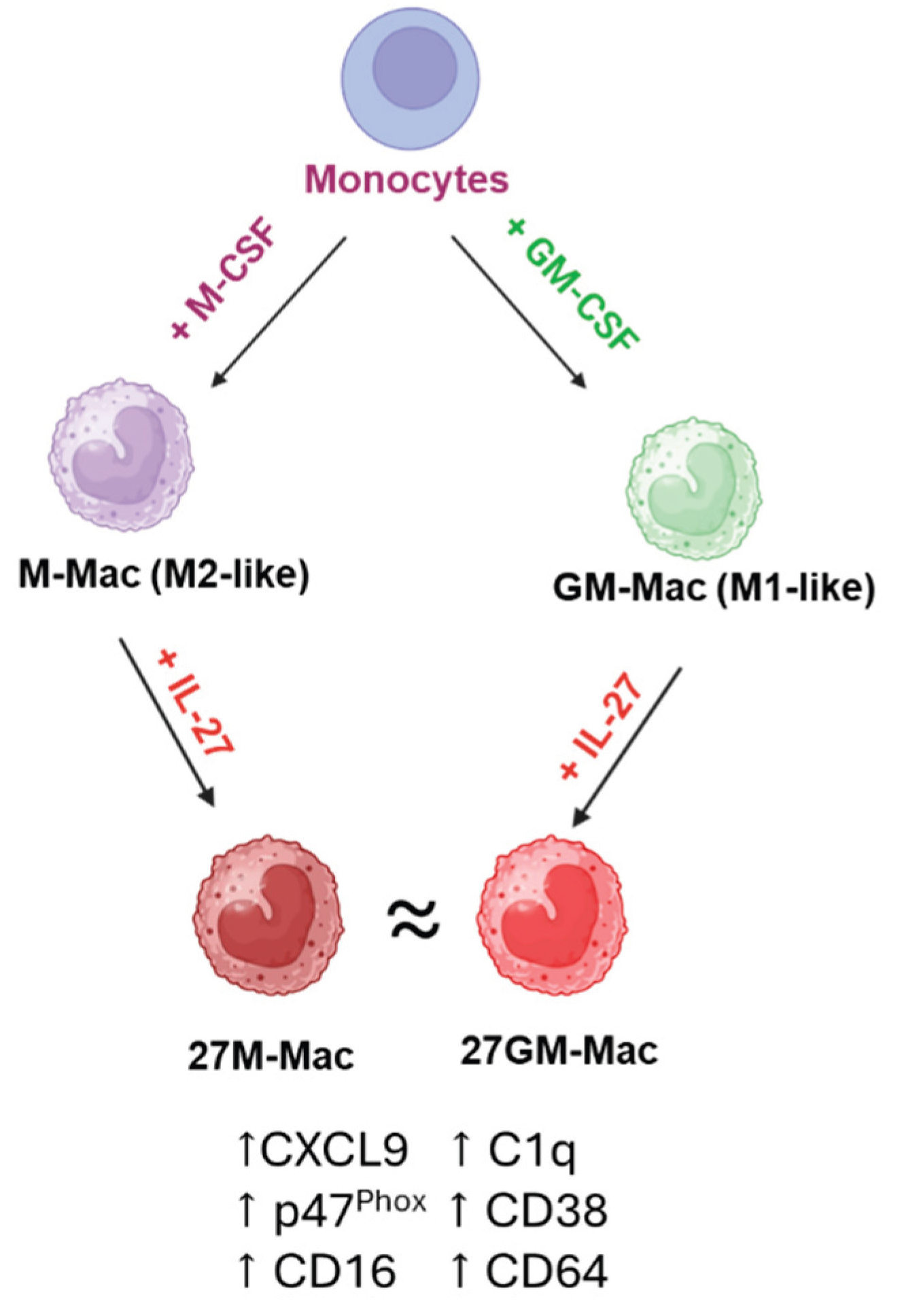

| GM-Mac | GM-CSF-induced macrophages |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| GCH1 | GTP cyclohydrolase 1 |

| AB-Mac | human AB serum-induced macrophages |

| IFN-g | IFN |

| IL-27R | IL-27 receptor |

| 27GM-Mac | IL-27-polarized GM-Mac |

| 27M-Mac | IL-27-polarized M-Mac |

| FcγRs | immunoglobulin G Fc receptors |

| IFN | interferon |

| ISGs | interferon-stimulated genes |

| IL-27 | Interleukin 27 |

| LRRK2 | leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| MMP8 | matrix metalloproteinase 8 |

| M-Mac | M-CSF-induced macrophages |

| MDMs | monocyte-derived macrophages |

| MOI | multiplicity of infection |

| NCF1 | neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 |

| PBMCs) | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PMA) | phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| PID1 | phosphotyrosine interaction domain containing 1 |

| QC | quality control |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative RT-PCR |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation assay |

| RAB7B | Ras-related protein B |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SELENOP | selenoprotein P |

| scRNA-Seq | single-cell RNA sequencing |

| SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2 |

| SNCA | synuclein alpha |

| t-SNE | t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor β |

| WB | Western blotting |

References

- Pflanz, S.; Timans, J.C.; Cheung, J.; Rosales, R.; Kanzler, H.; Gilbert, J.; Hibbert, L.; Churakova, T.; Travis, M.; Vaisberg, E.; et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. Immunity 2002, 16, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflanz, S.; Hibbert, L.; Mattson, J.; Rosales, R.; Vaisberg, E.; Bazan, J.F.; Phillips, J.H.; McClanahan, T.K.; de Waal Malefyt, R.; Kastelein, R.A. WSX-1 and glycoprotein 130 constitute a signal-transducing receptor for IL-27. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2225–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aioi, A.; Imamichi, T. IL-27 regulates cytokine production as a double-edged sword in keratinocytes. Trends Immunother. 2022, 6, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakruddin, J.M.; Lempicki, R.A.; Gorelick, R.J.; Yang, J.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Garcia-Pineres, A.J.; Pinto, L.A.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T. Noninfectious papilloma virus-like particles inhibit HIV-1 replication: implications for immune control of HIV-1 infection by IL-27. Blood 2007, 109, 1841–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowrirajan, B.; Saito, Y.; Poudyal, D.; Chen, Q.; Sui, H.; DeRavin, S.S.; Imamichi, H.; Sato, T.; Kuhns, D.B.; Noguchi, N.; et al. Interleukin-27 Enhances the Potential of Reactive Oxygen Species Generation from Monocyte-derived Macrophages and Dendritic cells by Induction of p47(phox). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, H.; Wiesinger, M.Y.; Nordhoff, C.; Schoenherr, C.; Haan, C.; Ludwig, S.; Weiskirchen, R.; Kato, N.; Heinrich, P.C.; Haan, S. Interleukin-27 displays interferon-gamma-like functions in human hepatoma cells and hepatocytes. Hepatology 2009, 50, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.C.; Zhang, X.; Katsounas, A.; Bharucha, J.P.; Kottilil, S.; Imamichi, T. Interleukin-27, an anti-HIV-1 cytokine, inhibits replication of hepatitis C virus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010, 30, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ting, S.M.; Liu, C.H.; Sun, G.; Kruzel, M.; Roy-O'Reilly, M.; Aronowski, J. Neutrophil polarization by IL-27 as a therapeutic target for intracerebral hemorrhage. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.O.H.; Silver, J.S.; Hunter, C.A. Chapter 1 - The Immunobiology of IL-27. In Advances in Immunology; Alt, F.W., Ed.; Academic Press, 2012; Vol. 115, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Imamichi, T.; Yang, J.; Huang, D.W.; Brann, T.W.; Fullmer, B.A.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Lempicki, R.A.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C. IL-27, a novel anti-HIV cytokine, activates multiple interferon-inducible genes in macrophages. Aids 2008, 22, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Swaminathan, S.; Yang, D.; Dai, L.; Sui, H.; Yang, J.; Hornung, R.L.; Wang, Y.; Huang da, W.; Hu, X.; et al. Interleukin-27 is a potent inhibitor of cis HIV-1 replication in monocyte-derived dendritic cells via a type I interferon-independent pathway. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Lidie, K.B.; Chen, Q.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Zheng, X.; Huang, D.; Yang, J.; Lempicki, R.A.; Rehman, T.; Dewar, R.L. IL-27 inhibits HIV-1 infection in human macrophages by down-regulating host factor SPTBN1 during monocyte to macrophage differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, C.; Yu, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, Q.; Bai, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, K.; et al. IL-27, a cytokine, and IFN-λ1, a type III IFN, are coordinated to regulate virus replication through type I IFN. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.; Xiao, Q.; Song, H.; Ma, F.; Xu, F.; Peng, D.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Niu, J.; Gao, P.; et al. Type I IFN augments IL-27-dependent TRIM25 expression to inhibit HBV replication. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Trout, R.; Spector, S.A. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells Inhibit Cytomegalovirus Inflammation through Interleukin-27 and B7-H4. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lou, C.; Liu, P. Interleukin-27 ameliorates coxsackievirus-B3-induced viral myocarditis by inhibiting Th17 cells. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Zhang, H.; Hai, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Interleukin-27 inhibits vaccine-enhanced pulmonary disease following respiratory syncytial virus infection by regulating cellular memory responses. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4505–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Hernández-Sarmiento, L.J.; Tamayo-Molina, Y.S.; Velilla-Hernández, P.A.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27, like interferons, activates JAK-STAT signaling and promotes pro-inflammatory and antiviral states that interfere with dengue and chikungunya viruses replication in human macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1385473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Fernandez, G.J.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27 as an inducer of antiviral response against chikungunya virus infection in human macrophages. Cell Immunol. 2021, 367, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwock, J.T.; Handfield, C.; Suwanpradid, J.; Hoang, P.; McFadden, M.J.; Labagnara, K.F.; Floyd, L.; Shannon, J.; Uppala, R.; Sarkar, M.K. IL-27 signaling activates skin cells to induce innate antiviral proteins and protects against Zika virus infection. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sarmiento, L.J.; Tamayo-Molina, Y.; Valdés-López, J.F.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27, Similar to Interferons, Modulates Gene Expression of Tripartite Motif (TRIM) Family Members and Interferes with Mayaro Virus Replication in Human Macrophages. Viruses 2024, 16, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobova, Z.R.; Arsentieva, N.A.; Santoni, A.; Totolian, A.A. Role of IL-27 in COVID-19: A Thin Line between Protection and Disease Promotion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Antiviral response and immunopathogenesis of interleukin 27 in COVID-19. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwell-Wild, T.; Vázquez, N.; Jin, W.; Rangel, Z.; Munson, P.J.; Wahl, S.M. Interleukin-27 inhibition of HIV-1 involves an intermediate induction of type I interferon. Blood 2009, 114, 1864–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzzo, C.; Jung, M.; Graveline, A.; Banfield, B.W.; Gee, K. IL-27 increases BST-2 expression in human monocytes and T cells independently of type I IFN. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.; Dai, L.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T. Evaluating the potential of IL-27 as a novel therapeutic agent in HIV-1 infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamichi, T.; Bai, X.-F.; Robinson, C.; Gee, K. IL-27 in health and disease; Frontiers Media SA, 2023; Vol. 14, p. 1191228. [Google Scholar]

- Imamichi, T.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Goswami, S.; Marquez, M.; Kariyawasam, U.; Sharma, H.N.; Wiscovitch-Russo, R.; Li, X.; Aioi, A.; et al. Interleukin-27-polarized HIV-resistant M2 macrophages are a novel subtype of macrophages that express distinct antiviral gene profiles in individual cells: implication for the antiviral effect via different mechanisms in the individual cell-dependent manner. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1550699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverdure, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Thomas, T.; Sato, T.; Nagashima, K.; Imamichi, T. Interleukin-27 promotes autophagy in human serum-induced primary macrophages via an mTOR- and LC3-independent pathway. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helps, T.; Baker, C.; Wilson, H.M.; Arthur, S.; Murray, G.I.; McLean, M.H. Characterising interleukin-27 (IL-27) responses in human blood derived macrophage cells. Cytokine 2026, 198, 157097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Martinez, F.O. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010, 32, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hume, D.A. Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unanue, E.R. Antigen-presenting function of the macrophage. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1984, 2, 395–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay Forman, H.; Torres, M. Redox signaling in macrophages. Mol. Asp. Med. 2001, 22, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.E. Cellular signaling in macrophage migration and chemotaxis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 68, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.E.; Pollard, J.W. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, K. Multiple roles of macrophage in skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2021, 104, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Higashimura, Y. Heme oxygenase-1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 564, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinetti-Gbaguidi, G.; Colin, S.; Staels, B. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.V.; Markin, A.M.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. The role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Changes in transcriptome of macrophages in atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackaman, C.; Yeoh, T.L.; Acuil, M.L.; Gardner, J.K.; Nelson, D.J. Murine mesothelioma induces locally-proliferating IL-10(+)TNF-α(+)CD206(-)CX3CR1(+) M3 macrophages that can be selectively depleted by chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1173299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalish, S.; Lyamina, S.; Manukhina, E.; Malyshev, Y.; Raetskaya, A.; Malyshev, I. M3 Macrophages Stop Division of Tumor Cells In Vitro and Extend Survival of Mice with Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic. Res. 2017, 23, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; Rice, C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 2011, 472, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshev, I.; Malyshev, Y. Current Concept and Update of the Macrophage Plasticity Concept: Intracellular Mechanisms of Reprogramming and M3 Macrophage "Switch" Phenotype. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 341308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitta, K.; Hummitzsch, L.; Lichte, F.; Fändrich, F.; Steinfath, M.; Eimer, C.; Kapahnke, S.; Buerger, M.; Hess, K.; Rusch, M.; et al. Effects of temporal IFNγ exposure on macrophage phenotype and secretory profile: exploring GMP-Compliant production of a novel subtype of regulatory macrophages (Mreg(IFNγ0)) for potential cell therapeutic applications. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Cao, P.; Sun, Z.; Wang, W. The characteristics of regulatory macrophages and their roles in transplantation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Galán, L.; Olleros, M.L.; Vesin, D.; Garcia, I. Much More than M1 and M2 Macrophages, There are also CD169(+) and TCR(+) Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S.; Locati, M.; Mantovani, A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7303–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleetwood, A.J.; Lawrence, T.; Hamilton, J.A.; Cook, A.D. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and macrophage CSF-dependent macrophage phenotypes display differences in cytokine profiles and transcription factor activities: implications for CSF blockade in inflammation. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 5245–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trus, E.; Basta, S.; Gee, K. Who’s in charge here? Macrophage colony stimulating factor and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor: Competing factors in macrophage polarization. Cytokine 2020, 127, 154939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, E.; Smyth, T.; Cobos-Uribe, C.; Immormino, R.; Rebuli, M.E.; Moran, T.; Alexis, N.E.; Jaspers, I. Expanded characterization of in vitro polarized M0, M1, and M2 human monocyte-derived macrophages: Bioenergetic and secreted mediator profiles. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0279037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; Dong, H.L.; Tai, L.; Gao, X.M. Lactoferrin-Containing Immunocomplexes Drive the Conversion of Human Macrophages from M2- into M1-like Phenotype. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.X.; Ou, D.L.; Hsieh, M.J.; Hsieh, C.C. Synergistic Effect of Repolarization of M2 to M1 Macrophages Induced by Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Combined with Lactate Oxidase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyarthi, A.; Khan, N.; Agnihotri, T.; Negi, S.; Das, D.K.; Aqdas, M.; Chatterjee, D.; Colegio, O.R.; Tewari, M.K.; Agrewala, J.N. TLR-3 Stimulation Skews M2 Macrophages to M1 Through IFN-αβ Signaling and Restricts Tumor Progression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J. Macrophage polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.H.; Jin, L. Macrophage Polarization in Physiological and Pathological Pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.-H.; Jin, L. Macrophage polarization in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Schmidt, S.V.; Sander, J.; Draffehn, A.; Krebs, W.; Quester, I.; De Nardo, D.; Gohel, T.D.; Emde, M.; Schmidleithner, L.; et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity 2014, 40, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarique, A.A.; Logan, J.; Thomas, E.; Holt, P.G.; Sly, P.D.; Fantino, E. Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 53, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrich, K.S.; Speen, A.M.; Ghio, A.J.; Bromberg, P.A.; Samet, J.M.; Alexis, N.E. Macrophages from the upper and lower human respiratory tract are metabolically distinct. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L752–l764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ni, H.; Lan, L.; Wei, X.; Xiang, R.; Wang, Y. Fra-1 protooncogene regulates IL-6 expression in macrophages and promotes the generation of M2d macrophages. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Smith, W.; Hao, D.; He, B.; Kong, L. M1 and M2 macrophage polarization and potentially therapeutic naturally occurring compounds. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 70, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, C.J.; Leibovich, S.J. Regulation of Macrophage Polarization and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2012, 1, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.; Riboldi, E.; Ippolito, A.; Sica, A. Molecular and epigenetic basis of macrophage polarized activation. Proceedings of Seminars in immunology; pp. 237–248.

- Wang, N.; Liang, H.; Zen, K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage M1–M2 polarization balance. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamichi, T.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Goswami, S.; Marquez, M.; Kariyawasam, U.; Sharma, H.N.; Wiscovitch-Russo, R.; Li, X.; Aioi, A. Interleukin-27-polarized HIV-resistant M2 macrophages are a novel subtype of macrophages that express distinct antiviral gene profiles in individual cells: implication for the antiviral effect via different mechanisms in the individual cell-dependent manner. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1550699. [Google Scholar]

- Theodore, T.S.; Englund, G.; Buckler-White, A.; Buckler, C.E.; Martin, M.A.; Peden, K.W. Construction and characterization of a stable full-length macrophage-tropic HIV type 1 molecular clone that directs the production of high titers of progeny virions. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1996, 12, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamichi, T.; Chen, Q.; Sowrirajan, B.; Yang, J.; Laverdure, S.; Marquez, M.; Mele, A.R.; Watkins, C.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Higgins, J.; et al. Interleukin-27-induced HIV-resistant dendritic cells suppress reveres transcription following virus entry in an SPTBN1, autophagy, and YB-1 independent manner. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0287829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rőszer, T. Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 816460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.S.; Hultquist, J.F.; Evans, D.T. The restriction factors of human immunodeficiency virus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 40875–40883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bime, C.; Zhou, T.; Wang, T.; Slepian, M.J.; Garcia, J.G.; Hecker, L. Reactive oxygen species-associated molecular signature predicts survival in patients with sepsis. Pulm. Circ. 2016, 6, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chang, G.; Wan, R.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Bai, H.; Wang, J. Discovery of a novel ROS-based signature for predicting prognosis and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 2691–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, K.; Wu, Z.; Mai, Y.; Dai, Y.; Hong, K.; Guo, Y. Identification of a novel reactive oxygen species (ROS)-related genes model combined with RT-qPCR experiments for prognosis and immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1074900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; He, J.; Xu, Q.; Xie, M.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, Q.; Xiang, M. Dual role of PID1 in regulating apoptosis induced by distinct anticancer-agents through AKT/Raf-1-dependent pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, V.; Moulakakis, C.; Stamme, C. Pulmonary surfactant protein A enhances endolysosomal trafficking in alveolar macrophages through regulation of Rab7. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 2397–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, Y.; Mizoguchi, I.; Furusawa, J.; Hasegawa, H.; Ohashi, M.; Xu, M.; Owaki, T.; Yoshimoto, T. Interleukin-27 Exerts Its Antitumor Effects by Promoting Differentiation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells to M1 Macrophages. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Wang, L.; Kuang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Q.; He, M.; Fan, J. IL-27 aggravates acute hepatic injury by promoting macrophage M1 polarization to induce Caspase-11 mediated Pyroptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cytokine 2025, 188, 156881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumoorthy, N.; Manisenthil Kumar, K.T.; Shyam Sundar, A.; Panayappan, L.; Chatterjee, M. Metallothionein: an overview. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstrom, P.A.; Murray, J.; Folks, T.M.; Diamond, A.M. Antioxidant defenses influence HIV-1 replication and associated cytopathic effects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998, 24, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Greenwell-Wild, T.; Nares, S.; Jin, W.; Lei, K.J.; Rangel, Z.G.; Munson, P.J.; Wahl, S.M. Myeloid differentiation and susceptibility to HIV-1 are linked to APOBEC3 expression. Blood 2007, 110, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.W.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Hsu, C.L.; Lin, E.; Zhang, N.; Guo, J.; Forbush, K.A.; Bevan, M.J. The extracellular matrix protein mindin is a pattern-recognition molecule for microbial pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Li, Q.; Yang, X.M.; Fang, F.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.H.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Nie, H.Z.; Zhang, X.L.; et al. SPON2 Promotes M1-like Macrophage Recruitment and Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis by Distinct Integrin-Rho GTPase-Hippo Pathways. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2305–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DEGs 1 | |||||

| Donor | Cell types | M | 27M | GM | 27GM |

| A | M | - | - | - | - |

| 27M | 560 | - | - | - | |

| GM | 119 | 755 | - | - | |

| 27GM | 398 | 219 | 264 | - | |

| B | M | - | - | - | - |

| 27M | 406 | - | - | - | |

| GM | 52 | 454 | - | - | |

| 27GM | 464 | 30 | 369 | - | |

| Phenotypes | M-Mac | 27M-Mac | GM-Mac | 27GM-Mac |

| HIV replication | ++++ | + | + | + |

| ROS induction ** | + | ++ | + | +++ |

| Phagocytosis | +++ | + | + | + |

| Autophagy | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Expression of | ||||

| CD38 | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| CD80 | + | + | + | + |

| CD86 | + | + | + | + |

| CD163 | + | + | + | + |

| CD206 | + | + | + | + |

| CD209 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD16 | +/- | + | +/- | ++ |

| CD32 | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| CD64 | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| Secretion of § | ||||

| CXCL9 | +/- | ++ | + | + |

| C1q | +/- | + | - | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).