1. Introduction

Despite the availability of antiretroviral agents with trial efficacies approaching or exceeding 99%, HIV prevention following exposure remains constrained by the biological dynamics of infection establishment [

1,

2]. Prevention is often discussed as a matter of coverage, adherence, or early treatment, implicitly assuming that post-exposure intervention remains feasible at all times following contact. A formal evaluation of this assumption requires specifying what prevention means in mathematical terms. Previous work has shown that HIV transmission and progression models are often highly sensitive to uncertain biological parameters, underscoring the difficulty of drawing robust conclusions from long-horizon simulations without strong constraints on initial conditions and system dynamics [

3].

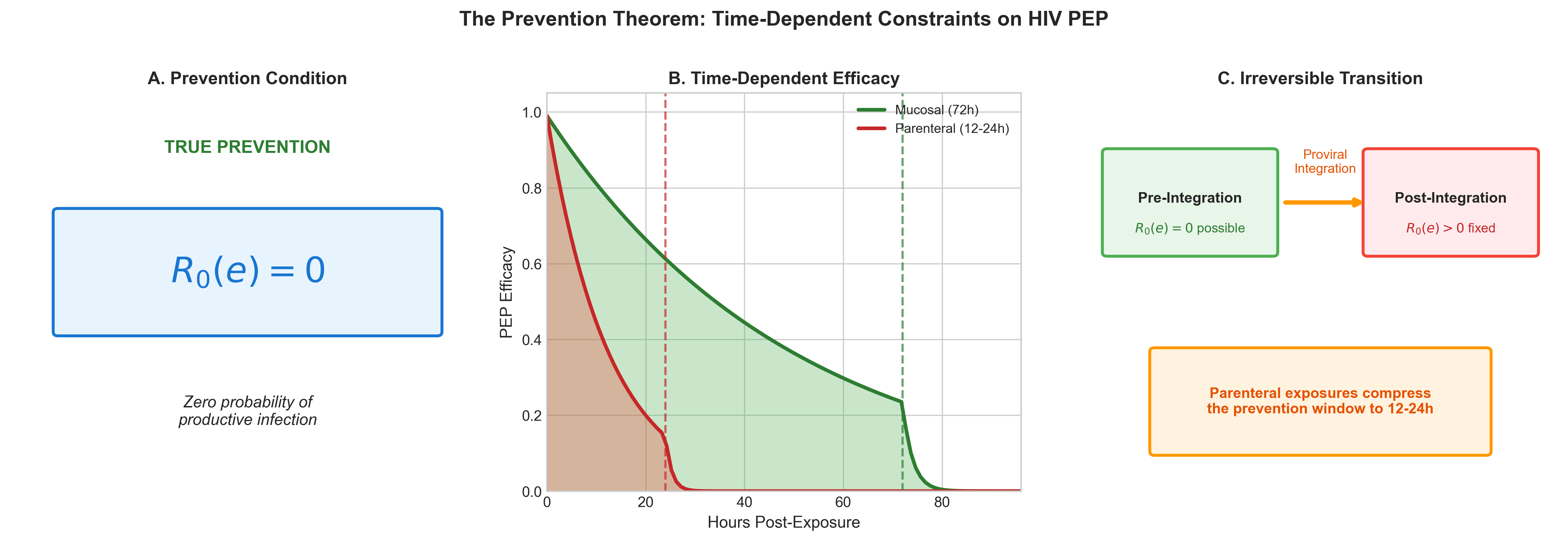

We define prevention for a specific viral exposure e as the condition R₀(e) = 0, corresponding to zero probability that the exposure establishes a productive, transmissible infection. Any state satisfying R₀(e) > 0 admits non-zero onward transmission and therefore cannot be considered complete prevention. Within this formulation, pre-exposure prophylaxis enforces R₀(e) = 0 by rendering the host non-susceptible prior to contact, whereas post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) attempts to enforce R₀(e) = 0 after contact but before infection establishment becomes irreversible.

Crucially, PEP operates as a time-dependent operator acting on within-host establishment dynamics, racing against irreversible biological processes including proviral integration and latent reservoir seeding. Once these processes are complete, the system undergoes a phase transition to an irreducible infection state in which R₀(e) > 0 is permanently fixed, independent of subsequent therapeutic intervention [

4,

5,

6]. This formulation applies to any pathogen in which irreversible genomic integration or long-lived latent reservoirs fix infection status beyond a critical temporal threshold.

In the sections that follow, we formalize this constraint through the Prevention Theorem and its corollaries, derive the finite temporal window during which PEP can enforce prevention, and illustrate the consequences of violating this boundary condition using the structural context of injection drug use as an applied example.

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework: The Prevention Theorem

We define the state of true prevention for a specific viral exposure e as the condition where the basic reproductive number for that exposure, R₀(e), is exactly zero.

This condition implies that the probability of the exposure establishing a productive, transmissible infection is zero [

7,

8]. Interventions are classified by their ability to enforce this condition. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) enforces R₀(e) = 0 by rendering the host non-susceptible prior to contact. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) attempts to enforce R₀(e) = 0 by extinguishing the virus after contact but before the infection becomes self-sustaining.

2.2. Closed-Form Prevention Solution

Let R(t) denote the total number of infected cells resulting from a single exposure event at time t. The system admits exactly one closed-form prevention solution:

If no infected cells exist at the initial condition, no infected cells can arise at any future time. For any initial condition satisfying R(0) > 0, no post-exposure or therapeutic intervention can mathematically guarantee R(t) = 0; all such interventions act only on the subsequent trajectory of R(t) and not on its initial condition [

9].

2.3. Infection Establishment Dynamics

We model within-host establishment dynamics following a single exposure event using logistic formulations for reservoir seeding, Pseed(t), and proviral integration, Pint(t) [

4]. These functions describe the cumulative probability that irreversible biological transitions have occurred by time t.

2.4. Master Equation for Time-Dependent Prevention

The efficacy of post-exposure intervention is time-dependent. We define the reproductive number as a function of intervention timing:

with the efficacy function defined as:

Here, εmax represents efficacy prior to seeding, εmid represents efficacy during the seeding window, and εmin represents efficacy after integration is established (typically zero for prevention purposes).

Because EPEP(t) depends on cumulative probabilities of irreversible biological transitions, once integration is established, this operator, EPEP(t) → 0 and R₀(e, t), admits a hard temporal cutoff once established [

10].

Corollary 1 (PEP Window Corollary): Post-exposure prophylaxis can enforce the prevention condition R₀(e) = 0 if and only if initiated within a finite biological window t < tcrit prior to irreversible proviral integration. Beyond this critical threshold, all reachable system states satisfy R₀(e) > 0 and are irreducible by post-exposure intervention or any therapeutic option currently available.

3. Results

3.1. Visualization of the Theorem

Figure 1 illustrates the four core components of the Prevention Theorem. Panel A shows the timeline of infection establishment, with reservoir seeding preceding proviral integration. Panel B demonstrates the time-dependent efficacy function EPEP(t), which decays monotonically toward zero as irreversible transitions accumulate. Panel C visualizes the phase transition into the irreducible infection state, where the probability of infection approaches certainty. Panel D summarizes the mathematical formalism.

3.2. Finite Prevention Window for Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Model parameterization indicates that the window for enforcing R₀(e) = 0 extends to approximately 72 hours for mucosal exposures, constrained by local immune bottlenecks [

10]. However, for parenteral exposures (e.g., injection), this window is compressed to roughly 12–24 hours due to the bypass of early mucosal barriers and rapid systemic dissemination [

11]. This 'left-shift' of the critical window significantly reduces the timeframe for effective intervention.

Figure 2 demonstrates the quantitative compression of the prevention window between mucosal and parenteral exposures. The parenteral route (red dashed line) shows a precipitous decline in prevention efficacy within the first 24 hours, whereas the mucosal route (blue solid line) maintains higher efficacy through 72 hours. This differential is driven by the distinct immunological bottlenecks encountered in each tissue compartment.

3.3. Irreducible Infection State

Proviral integration represents a thermodynamically irreversible transformation of the host genome. Once integrated, viral DNA persists for the lifetime of the cell and is propagated to all daughter cells during division, producing clonal expansion independent of ongoing viral replication [

5].

No biologically realizable inverse transformation exists that restores the pre-integration genomic state. Consequently, once integration occurs, the condition R₀(e) = 0 is mathematically unattainable [

12,

13].

3.4. Reservoir Stratification

Long-lived viral reservoirs persist in specific cellular compartments, including naïve T-cells, central memory T-cells (TCM), stem cell-like memory T-cells (TSCM), and microglial cells [

5,

14]. These compartments are characterized by self-renewal capacity and longevity, allowing viral persistence independent of viral replication [

15].

3.5. Applied Example: Structural Infeasibility Under Access Delays

Comparison of the derived biological windows against empirically observed access delays in high-risk populations (e.g., people who inject drugs) reveals a fundamental mismatch. Surveillance data indicates that while 85% of sexual exposure cases present to Emergency Departments within 72 hours, structural delays for injection-related exposures consistently exceed the compressed 24-hour parenteral window [

16,

17].

For this population, the cycle time required to navigate arrest, withdrawal, and housing instability (Tstruct) almost invariably exceeds the biological cycle time (Tbio). Consequently, the condition R₀(e) = 0 is biologically unreachable before access is even attempted. In these scenarios, failure is not a probabilistic outcome of drug efficacy or adherence, but a deterministic result of timing constraints.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

Prevention is fundamentally an existence problem: does a state R₀(e) = 0 exist and is it reachable? Our analysis shows that PEP failure often represents a boundary violation rather than adherence failure; late intervention cannot alter the initial condition R(0) > 0 once it has been established [

9].

4.2. Biological Proof of Concept: CCR5-Δ32

The only known 'cure' scenarios involve CCR5-Δ32 transplantation, which effectively eliminates the susceptibility term in the transmission equation [

13]:

This intervention functions as a system replacement rather than a reversal of the infection state, reinforcing the irreversibility of the integrated provirus in susceptible hosts.

4.3. Implications for Epidemic Control

Reactive interventions cannot achieve epidemic control when biological establishment precedes access. Prevention architectures must therefore be evaluated against biological feasibility constraints, not solely pharmacological efficacy [

18].

5. Future Work

Future analyses will explore stochastic population dynamics and network-level avoidance collapse resulting from these constraints. The specific impact of architectural failure on population-level incidence is explicitly deferred to subsequent analysis.

Data Sharing

All model code, simulation outputs, and analysis scripts are available at https://github.com/Nyx-Dynamics/Prevention-Theorem. All model inputs derive from published literature or synthetic populations; no individual-level data were used.

Declaration of Interests

The author reports prior employment with Gilead Sciences, Inc. from January 2020 through November 2024 and prior ownership of company stock, which was fully divested in December 2024. Gilead Sciences, Inc. had no role in the conception, design, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this study, and provided no funding, data, materials, or input into any aspect of the work. The author is the owner of Nyx Dynamics, LLC, a consulting company providing advisory and fractional leadership services in healthcare, technology, and complex systems. This research was conducted independently, released as open-source work, and was not produced as part of, or in support of, any paid consulting engagement. No other competing interests are declared.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study did not involve human participants, human biological samples, or the collection of identifiable private information. All analyses were conducted using publicly available, aggregate data from published literature and guidelines. As such, institutional review board (IRB) approval and informed consent were not required.

Acknowledgments

Communities. The author thanks the HIV prevention research community whose published work informed model parameterization, and the people who inject drugs (PWID) community advocates whose testimony informed characterization of structural barriers.

Use of Artificial Intelligence and Assistive Technologies

The author acknowledges the use of artificial intelligence–assisted tools during manuscript preparation. Computational analyses were conducted using Python with open-source packages including NumPy, Pandas, SciPy, Matplotlib, and Seaborn. Large language models (Anthropic Claude and OpenAI ChatGPT) were used to support literature search and improve readability of the manuscript. JetBrains Junie was used for code correction, and Zotero AI was used for reference management. Manuscript preparation was conducted using the Overleaf LaTeX platform. All AI tools were used as assistive technologies only. The author retains full responsibility for study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, and all conclusions presented.

References

- Grant, R. M. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363(27), 2587–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P. L. Emtricitabine–tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Science Translational Medicine 2012, 4(151), 151ra125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blower, S. M.; Dowlatabadi, H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: An HIV model as an example. International Statistical Review 1994, 62(2), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A. J.; Rowland-Jones, S. L. The immune response to HIV. Immunity 2010, 33(4), 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, L. Al-Harthi, HIV infection of non-classical cells in the brain. Retrovirology 2023, 20(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliciano, J. D.; Siliciano, R. F. Enhanced culture assay for detection and quantitation of latently infected, resting CD4+ T-cells. Methods in Molecular Biology 2015, 1354, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, D.; Hay, G. Mathematical modelling of the spread of HIV/AIDS amongst injecting drug users. IMA Journal of Mathematics Applied in Medicine and Biology 1997, 14(1), 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Greenhalgh, D.; Mao, X. A Stochastic Differential Equation Model for the Spread of HIV amongst People Who Inject Drugs. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine 2016, 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant. Evidence for Early Central Nervous System Involvement in the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Annals of Internal Medicine 1987, 107(6), 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, M. R. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV – CDC recommendations, United States, 2025. MMWR Recomm Rep 2025, 74(1), 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathdee, S. A. Preventing HIV outbreaks among people who inject drugs in the United States: plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. AIDS 2020, 34(14), 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. R.; Castillejo, A. Long-term follow-up of the London patient—the second adult to be cured of HIV-1 infection. Lancet HIV 2019, 6(12), e821–e829. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, G. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell-derived grafted dendritic cells. New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 360(7), 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. M. Neuroinflammation in HIV: The role of translocator protein. Journal of Neurovirology 2020, 26(6), 768–786. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth. Very early initiation of antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV infection is associated with normalized levels of immune activation markers in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018, 220(2), 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.; Walley, A. Y.; Bazzi, A. R. Stuck in the window with you: HIV exposure prophylaxis in the highest risk people who inject drugs. Substance Abuse 2019, 40(4), 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baugher, R. Are we ending the HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs? Key findings from 19 US cities. AIDS 2025, 39(12), 1813–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palella, F. J. J. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 338(13), 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).