1. Introduction

Internal combustion engines (ICEs) remain as one of the most widely used technologies for mobility and emergency electricity generation worldwide. Despite the growing shift in investment and policy towards electric mobility [

1], the global fleet of ICE vehicles is still immense, and several projections even suggest that their production will continue for the upcoming decades [

2,

3,

4]. In this scenario, improving the efficiency and sustainability of ICEs remains essential to meeting global mobility demand.

Among the key systems in ICEs, lubrication processes play a fundamental role in controlling friction and wear, mainly. There are previous studies that highlighted the enormous amounts of energy losses, economic costs, and pollutant emissions directly related to friction and wear, as tribological phenomena, in ICE [

5,

6]. Therefore, even small improvements in lubrication management can provoke significant economic and environmental impacts.

Conventional ICEs lubrication operates within two limiting regimes, hydrodynamic and boundary lubrication. In the first one, surfaces are separated preventing direct contact and ensuring protection. In the second one, boundary lubrication provides the last line of defense against friction and wear. This regime is governed by complex physicochemical and mechanical interactions that lead to the formation of a protective solid film between surfaces [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This interaction establishes a dual game: mechanical operating variables are determined by ICEs performance, in contrast, chemical variables are highly influenced through lubricant formulation and periodic replacement.

In batch lubrication systems, selecting the optimal lubricant formulation and determining the most efficient replacement intervals is challenging, even when guided by manufacturer recommendations. Furthermore, the economics of lubricant use are not only defined by the purchase cost, but also by the rate of consumption, the supply strategy, and the excess of lubricant precursors required to maintain adequate protection [

11,

12].

This work addresses this gap by analyzing the economics of lubricant consumption in ICEs lubrication systems from a phenomenological perspective. Two supply strategies, discrete batch lubricant make-up and continuous lubricant make-up, are specifically compared, emphasizing the rate of lubricant make-up and the excess of lubricant precursors required to ensure reliable boundary lubrication, rather than direct monetary costs.

2. Methodology

A mathematical model describing lubricant depletion, under batch and continuous supply conditions, is established as the basis for the subsequent economic comparison, following the physical phenomena taking place on the shearing surfaces, the moving and the static ones, as described below.

2.1. The physical system

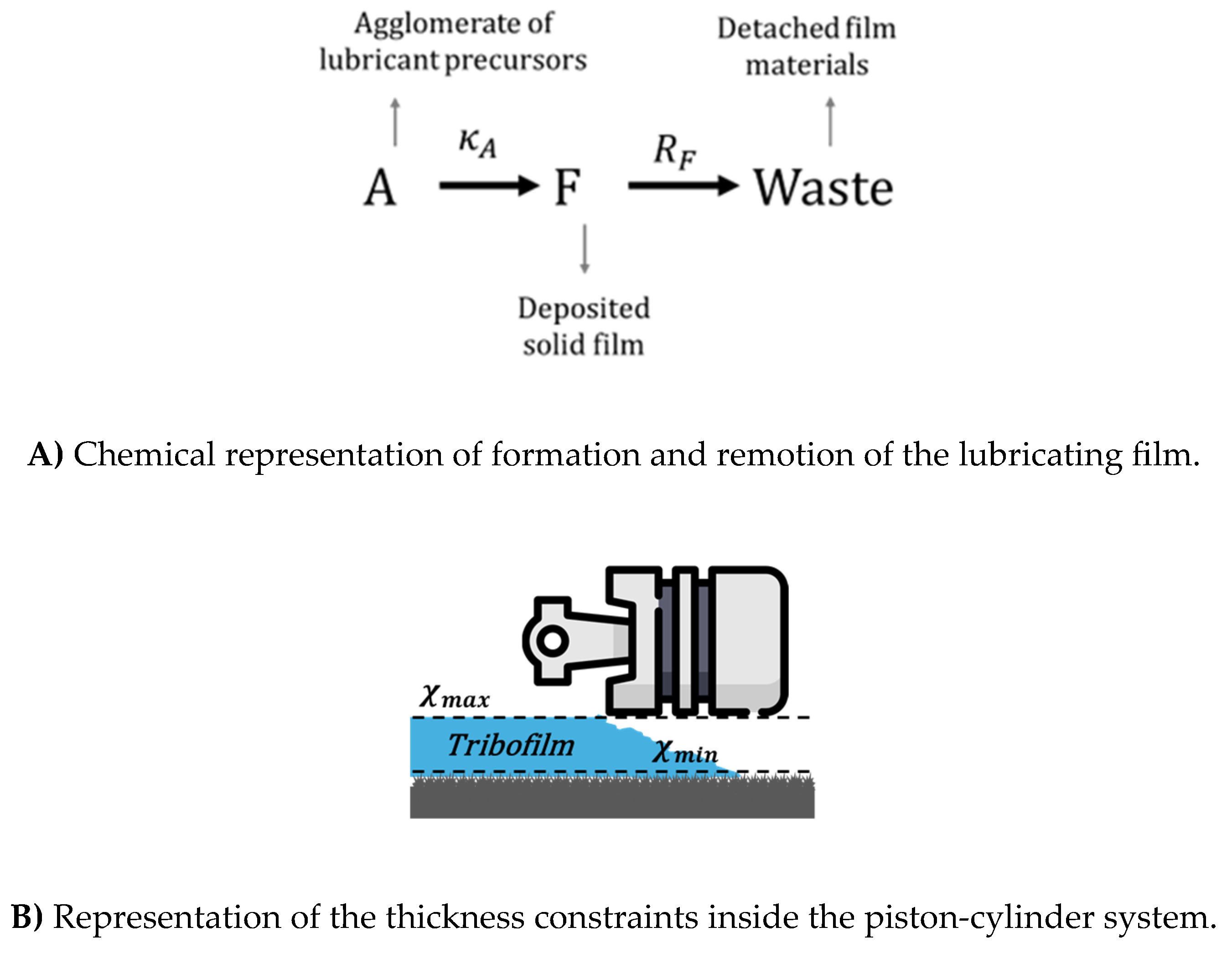

Firstly, liquid lubricants bring molecules of lubricant precursors inside the piston-cylinder system (

Figure 1-A). The variety of additives contained in the lubricant formula [

8,

13,

14,

15] is conceived as the agglomerate ‘A’, which adsorbs on both surfaces [

8,

9]. Secondly, deposited molecules chemically react to form a solid film, called ‘F’, which is microstructurally modified by mechanical contacts [

8,

9]. If the strength over this film is large enough, then it is detached from the surfaces and, simultaneously, it is renovated by chemical reactions [

9,

16]. It is assumed that detached film materials (waste) cannot regenerate the film [

9,

16]. A kinetic representation of formation and removal of the lubricating film is described ahead. As consequence of the competition between formation and removal of the lubricant film inside ICEs, some amount of film is accumulated between the surfaces. This film thickness is constrained between two practical limits; the minimum thickness (

Xmin) required to avoid direct contact of the surface roughness, and the maximum thickness (

Xmax) of separation between the shearing surfaces [

11], (

Figure 1-B).

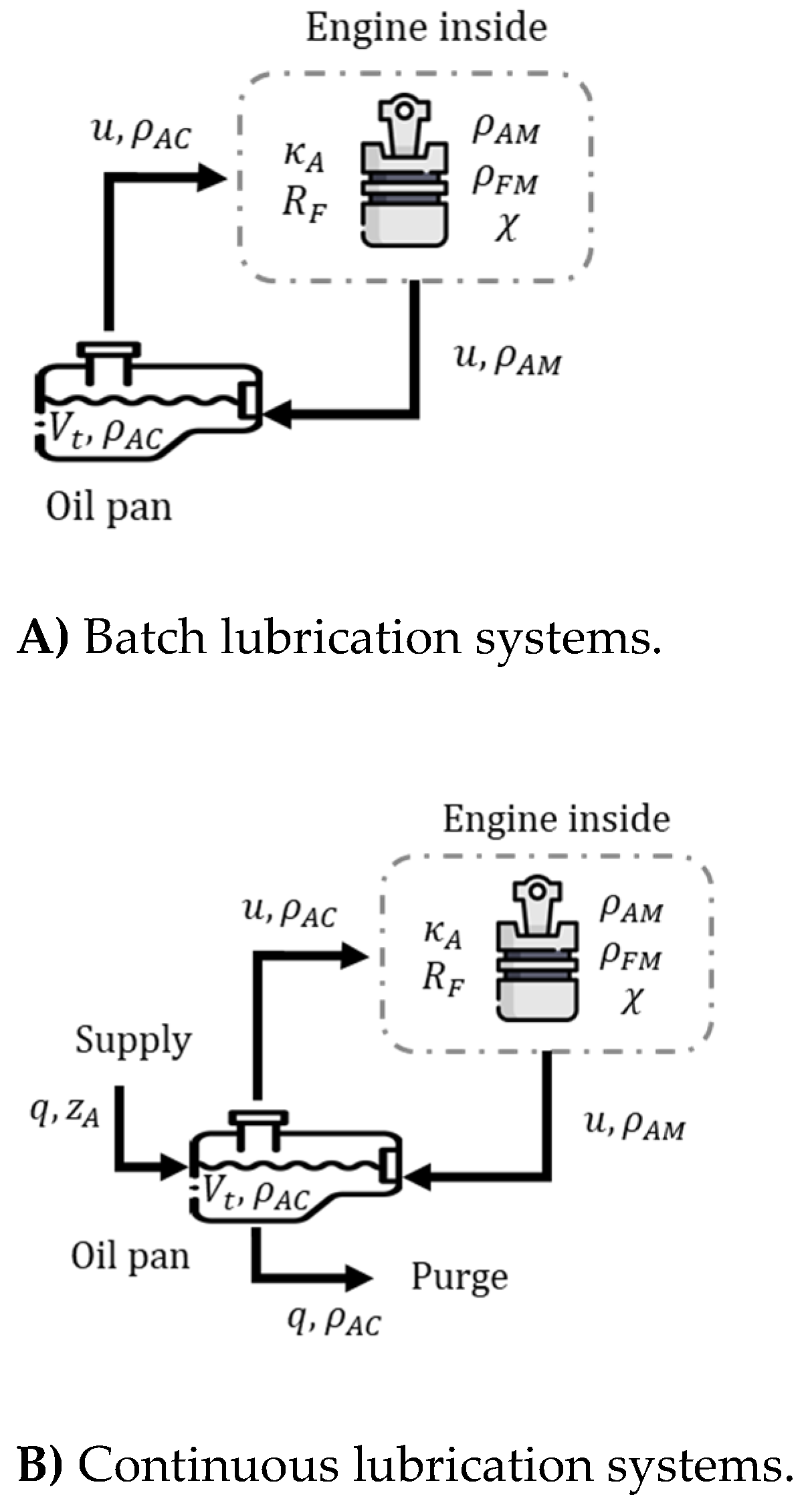

Commonly, batch lubrication systems for ICEs store a volume of working lubricant in a vessel called ‘oil pan’. Then, a lubricant flow is filtered, circulated through the engine, and then returns to the oil pan (

Figure 2A). This recirculation gradually depletes the lubricant’s properties and defines its service lifetime. In contrast, continuous lubrication systems also circulate lubricant flows between the oil pan and the engine inside. However, in this strategy, a fresh lubricant flow is supplied while a corresponding purge is discharged from the oil pan preventing the total depletion of the lubricant precursors (

Figure 2B).

The mathematical model describing the variation in lubricant precursors available for film renewal is based on mass balances that quantify the accumulation, input, output, generation, and consumption of each precursor substance or agglomerate in the oil sump and engine interior [

9,

11]. The model formulation for both supply strategies, batch and continuous, analyzed in this article is presented below.

2.2. Reserve of lubricant precursors in the oil pan

Following the mathematical model developed in previous scientific reports [

9,

11], the reserve of precursors

A in the oil pan is described by a mass balance equation. For batch supply, it is expressed by Equation (1A), and for continuous supply by Equation (1B).

Here, is the control volume within the oil pan; is the partial density of precursors A inside the oil pan; is the partial density of precursors A inside the engine; u is the volumetric flow rate between the oil pan and the engine interior; q is the volumetric flow rate of fresh lubricant and of purge; and is the concentration of precursors A in the fresh lubricant. The only difference between the mathematical models describing batch and continuous lubrication strategies lies in Equations (1A-1B). All other mass balances and constraints and initial conditions apply to both conditions.

2.3. Concentration of lubricant precursors inside the engine

The concentration of precursor

A inside of the engine is obtained from a mass balance over the volume of lubricant flowing through the engine (Equation 2).

Here, is the control volume of the engine; is the partial density of precursors A inside the engine; and is the kinetic constant of the reaction of A inside the engine.

2.4. Deposited lubricating film inside the engine

The amount of lubricant film deposited inside the engine is obtained from a dynamic mass balance of the agglomerate

F over the volume of lubricant flowing through (Equation 3).

The growth (σ) and removal (ς) constraints are defined by (Equations 4, 5), respectively.

Here, is the partial density of lubricant film inside the engine; σ is a growing constrain; ς is a removal constraint; and is the removal base rate.

The growing and removal constraints were defined, previously, by [

11],: σ becomes zero once the maximum film thickness

is reached, deactivating further accumulation of

F beyond the separation between shearing surfaces (Equation 4); Conversely, ς is the ratio between the film thickness

χ and the minimum thickness required to avoid the direct surface-to-surface contact. This ratio accounts for the slowing down effect on film removal caused by surface roughness interactions when

(Equation 5)

2.5. Thickness of the lubricating film

Following the mathematical relationship between the film mass

F and the film thickness, it requires distributing the film volume over the contact surface [

9,

11]. Generally, this distribution of film volume is not uniform due to the surface asperities of the metallic substrate. The total film volume

is estimated by (Equation 7) by integrating its derivative with respect to the variation in film thickness

χ (Equation 6). Simultaneously, the definition of the film mass

is generated (Equation 8).

Here, is the actual density of the deposited film, and is the internal surface of the engine.

Combining Equations (5)–(8), an analytical solution for film thickness as a function of the film accumulated (Equation (9)) is obtained.

Here,

is the partial density of film required to cover the surface asperities up to

, setting the minimum operational thickness. An alternative derivation of (Equations 5-8), by definite integration, yields

as a function of

,

,

, and

(Equation 10).

2.6. Lifetime of each lubricant fill

In the batch supply strategy, each lubricant volume protects the engine only for a limited operating period, denoted as τ (Equation 11). This interval ends when the film thickness decreases up to the critical thickness

. Beyond this point, surface asperity interactions intensify, leading to wear and damage [

11].

2.7. Critical supplying rate of lubricant for the batch system

The total lubricant volume consumed per batch

corresponds to the sum of the engine control volume (

) and the oil pan control volume (

) (Equation 12). By combining (Equations 11, 12), the critical supplying rate (

) during an operation period

can be estimated for the batch supply strategy (Equation 13).

2.8. Critical supplying rate of lubricant for the continuous system

For the continuous supply strategy, the critical make-up rate required to maintain the film thickness above

is determined when the accumulation terms in the mass balance equations (Equations 1–3) vanish (Equation 14). These conditions indicate that the film formation and depletion rates are equivalent, a state referred to as the equilibrium film.

The critical partial densities of precursors

A in the oil pan (

) and within the engine (

), together with the minimum lubricant make-up rate (

), required to form the equilibrium film that maintains the film thickness above

(for σ=ς =1), are obtained by combining (Equations 1–3 and 14) into an algebraic system (Equations 14A–C).

After straightforward algebraic manipulation, the model for the critical supplying rate yields the following expressions for the system at critical conditions, depending solely on the parameters

,

,

, and

, (Equations 15–17).

Since in the continuous supply strategy, (Equations 15–17) are independent of operating time, the precursor concentration can be maintained indefinitely. In contrast, under the batch strategy, is reached instantaneously, only once, at the end of the operating period.

2.9. Excess of lubricant precursors in lubrication systems

Once the equilibrium film condition has been established, real lubrication systems rarely operate exactly at this point. During practical operation, the precursor concentration in the oil pan () fluctuates due to cycles of lubricant replenishment and consumption. These deviations from the equilibrium concentration within the engine () represent the “excess” of lubricant precursors temporarily available beyond the critical requirement for sustaining the film thickness.

To quantify this deviation, the instantaneous excess concentration can be defined as (

). Over the total operating period

of actual time, the accumulated or average deviation provides a measure of how much the system operates above the equilibrium demand. This allows defining a dimensionless “excess ratio” (Equation 18) by normalizing the time-averaged deviation with respect to the maximum possible concentration difference

.

Here, is the excess in consumed lubricant precursors; is the time step; and is the total operating time. This expression provides a dimensionless indicator of how efficiently the lubricant precursors are utilized relative to the equilibrium condition.

2.10. Feasibility limit of actual lubrication

In (Equation 17), an implicit constraint of the continuous lubrication strategy emerges; if the value in the denominator becomes null or negative, the minimum make-up rate turns infinite or negative. Therefore, the continuous strategy is feasible only for certain values of

and

. This condition (Equation 19) defines the range for the parameter values that ensure physically meaningful make-up rates.

In contrast, the batch strategy does not yield an explicit analytical restriction for the supply rates. However, parametric exploration of and , shows that the same condition (Equation 19) also governs the feasibility of batch lubrication systems. The demonstration of this affirmation is presented in the results section.

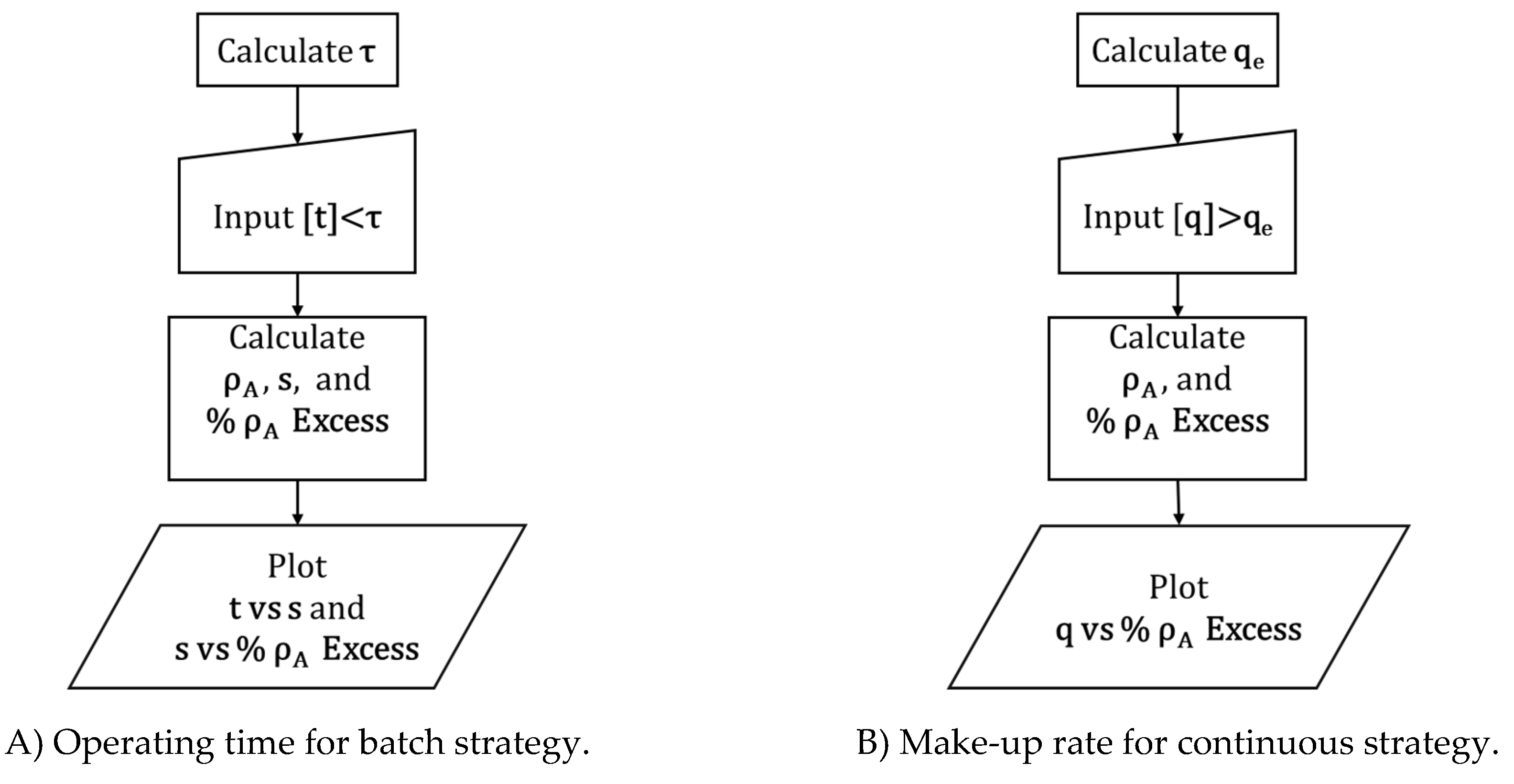

2.11. Supercritical conditions of lubrication systems

Any non-critical operating condition can be analyzed by reducing the operation time for the batch strategy; and by increasing make-up rate for the continuous strategy. In both cases, the comparation criteria are the supplying rates and versus the excess of lubricant .

Two algorithms are proposed to obtain the supply rates versus the excess of lubricant. The computational solution allows the user to observe two lubrication strategies: (

Figure 3A) Behavior of the batch system if operation time is reduced, and (

Figure 3B) behavior of the continuous system if lubricant make-up rate is increased.

2.12. Simulations design

Firstly, a detailed analysis of

,

,

, and

for base cases of both strategies, batch and continuous, calculated for

,

. The lubricant exhibits the properties:

and

. Parameters in

Table 1, and (Equations 1-10) are simulated to compare both ICE lubrication strategies

After the analysis of the base cases, a study on the sensibility of the critical supply rates and to variation on and is developed. This time, the target is to observe how the variation on kinetic parameters modifies the critical supply rates of lubricant for both lubrication strategies (Equations 13 and 16). The parameters’ space considered for the analysis was defined as and .

The final study of this work is dedicated to observing the behavior of the two lubrication strategies when the supply rates are supercritical, or larger than the minimum lubricant make-up required to sustain film thickness at suitable levels. This analysis is carried out by implementing the computation procedures indicated in (

Figure 3) and conditions of the base cases (

Table 1). The two sets of values are used to calculate the supply rates (Equation 13), and the corresponding consumed excess of lubricant

(Equation 17) are given in

Table 2.

3. Results

The data analyzed in this work were computed by solving, numerically, the mass balances given by (Equations 1-18). The complete numeric solution was programed in a student’s version of MATLAB™.

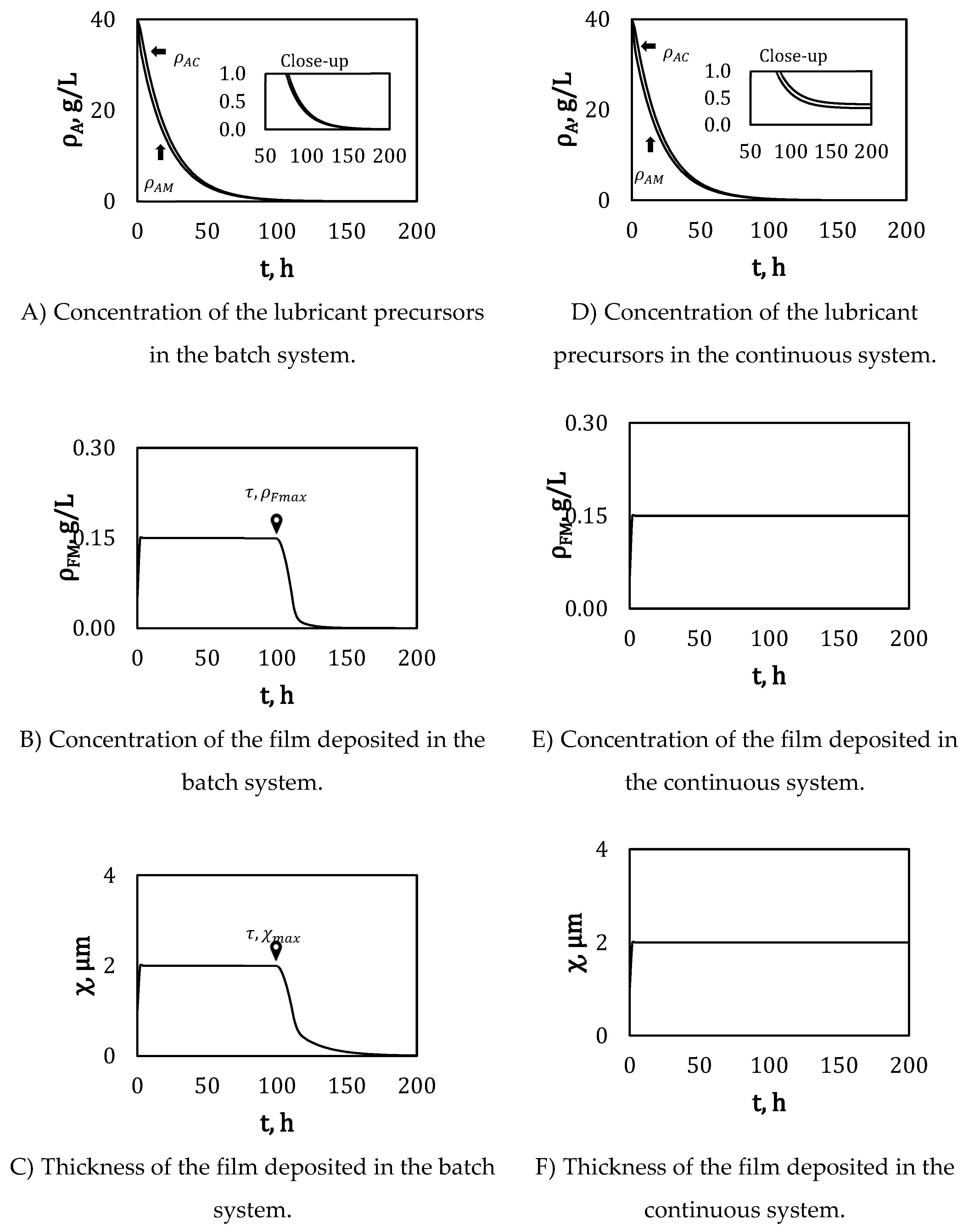

3.1. The behavior of the base cases for both lubrication strategies

For the batch strategy, the reserve of lubricant precursors within the oil pan and inside the engine decreases as the operation time increases (

Figure 4A). At the beginning of the simulation, both partial densities,

and

, exhibit the same value

. However, the concentration of lubricant precursors tends toward zero by the end of the simulation (200 h). During the initial simulated hours, a gap appears between the precursor concentrations in the oil pan and inside the engine, but a close-up of both profiles shows their convergence toward zero in the final hours of the simulation (

Figure 4A).

The partial density of the lubricating film accumulated inside the engine increases rapidly up to approximately 0.15 g/L and remains stable until 100 h of simulation (

Figure 4B). This period corresponds to the limited operating time

for the base case. After this

, the accumulated film progressively decreases to zero by the end of the simulation (

Figure 4B). Similarly, the film thickness remains stable at

only during the limited operating time

, after which it gradually decreases to zero (

Figure 4C).

For the continuous strategy, the reserve of lubricant precursors within the oil pan and inside the engine also decreases as the operation time increases (

Figure 4D). At the beginning of the simulation, both partial densities,

and

, exhibit the same initial value

. However, the concentrations of lubricant precursors tend toward stable partial densities by the end of the simulation. During the initial hours, a gap appears between the precursor concentrations in the oil pan and inside the engine, but a close-up of both profiles shows their convergence toward approximately

and

for the final simulated hours (

Figure 4D).

For the continuous strategy, the partial density of the lubricating film accumulated inside the engine increases rapidly up to approximately 0.15 g/L and remains stable until the end of the simulation (

Figure 4E). Similarly, the film thickness remains constant at

throughout the entire simulation period (

Figure 4F).

In the batch strategy, the lubricant—comprising both, plus , must be completely replaced every 100 h of operation time to maintain the film thickness at appropriate levels. Conversely, the continuous strategy does not require replacement of the total lubricant volume in the system; instead, it sustains a constant lubricant flow to preserve the film thickness within the desired range. Despite these operational differences, both strategies can fulfill the lubrication requirements.

3.2. Comparison of the lubricant consumption for both strategies at the base case

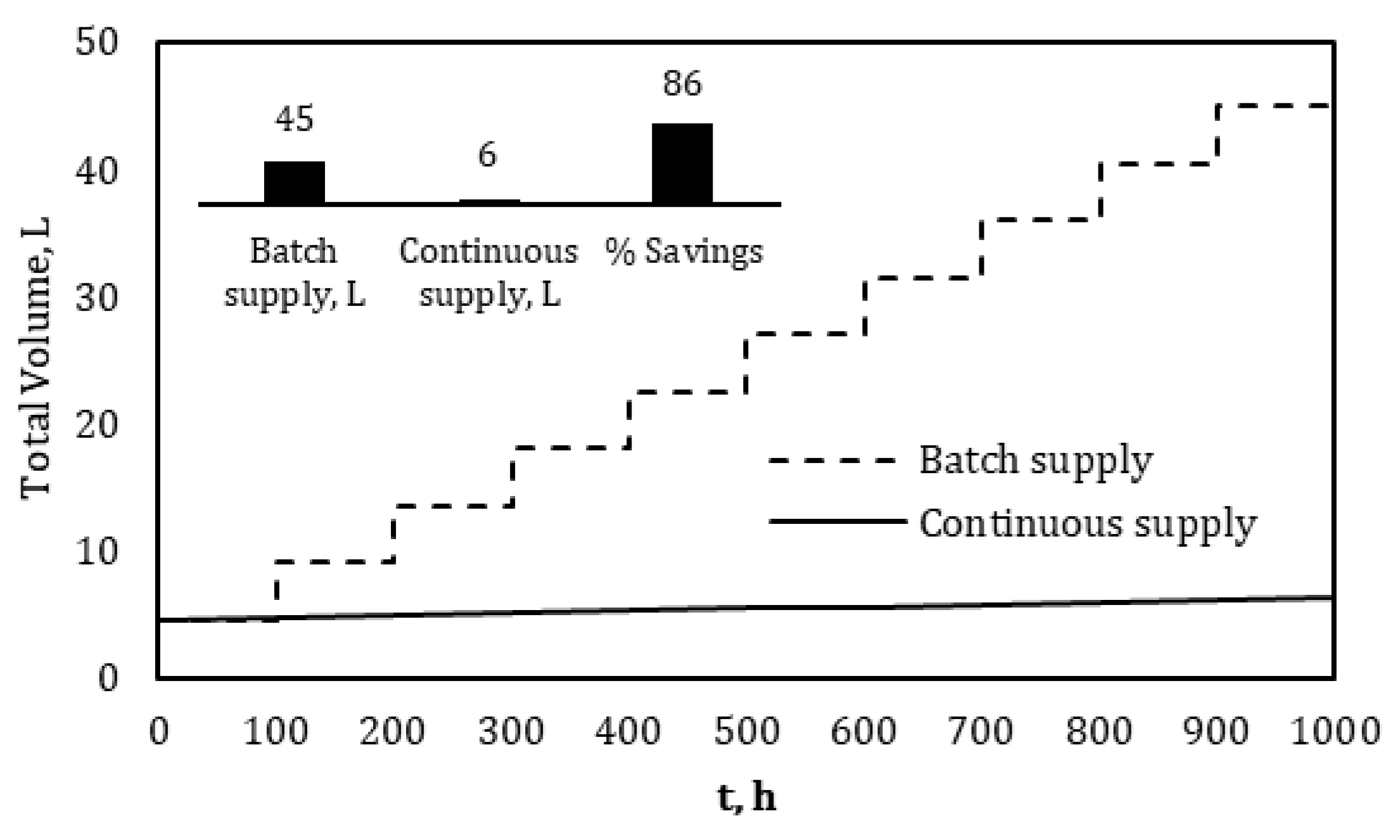

The batch and continuous lubrication strategies consume different lubricant volumes over comparable operation times.

Figure 5 illustrates the total lubricant consumption during 1000 h of operation. In the batch strategy, the entire lubricant volume is replaced every 100 h, increasing by 4.5 L per interval. Consequently, the consumption profile exhibits a step-like shape, reaching a total volume of 45 L by the end of the operation period.

In contrast, using the continuous strategy, the oil pan is initially filled with 4.5 L of lubricant, and a continuous make-up flow of is maintained throughout the operation. Thus, the consumption profile follows a linear trend, reaching approximately 6 L at the end of the 1000 h period. Overall, the continuous lubrication strategy reduces lubricant consumption by about 86% compared with the batch strategy.

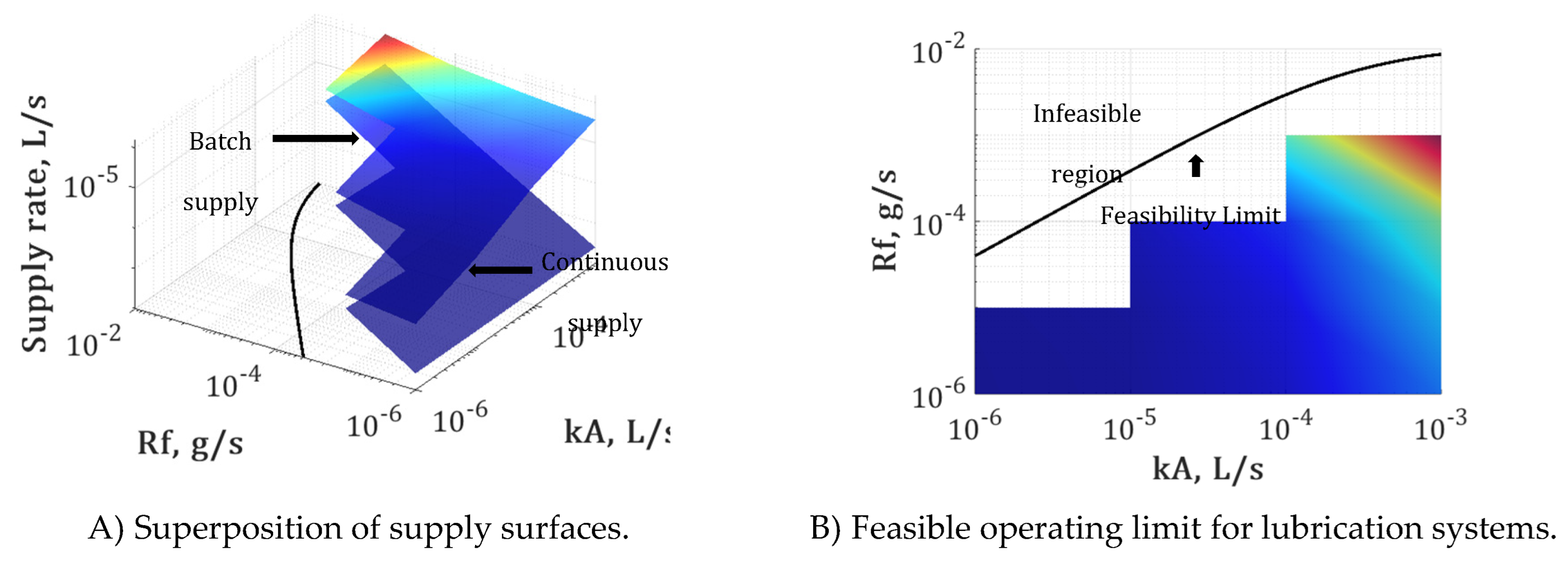

3.3. Study on the sensibility of the two lubrication strategies

The sensitivity analysis generated two lubricant supply surfaces (

Figure 6A), both bounded by the feasibility limit defined in (Equation 18). The surface corresponding to the continuous supply strategy consistently lies below that of the batch strategy. In both cases, the supply rate increases with the removal rate

and the kinetic parameter

; however, the influence of

is less notorious than that of

(

Figure 6A). Non-positive lubricant supply rates were obtained for the kinetic parameter pairs (

and

) of

,

, and

. These points are located within the infeasible region (

Figure 6B), beyond the operational limit established by (Equation 18).

For the continuous lubrication strategy, the (Equation 18) restricts the range of and into combinations all ones which provide positive supply rates. In contrast, in the batch lubrication strategy, infinite supply rates appear when the operating period approaches zero (Equation 13).

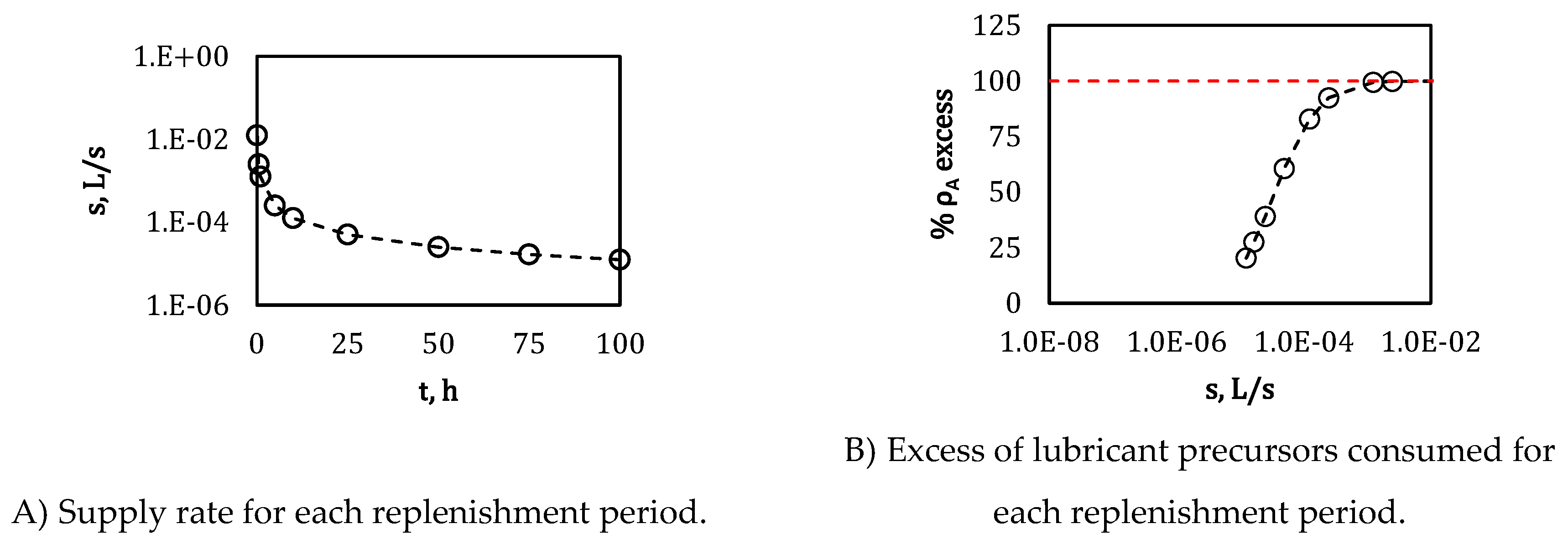

3.4. Supercritical operation of the batch supply lubrication strategy

The supercritical supply rates (

) calculated for operating periods shorter than

exhibit a hyperbolic increasing trend, tending toward infinity as time approaches zero (

Figure 7A). Similarly, the trajectory of the excess lubricant precursors consumed under supercritical conditions follows a hyperbolic increase; however, in this case, the profile is horizontally bound, asymptotically approaching 100% excess as the supply rate (

) increases (

Figure 7A). The minimum excess of lubricant precursors corresponds to 20%, which represents the critical condition for

(

Figure 7A).

3.5. Supercritical operation of the continuous supply lubrication strategy

For the continuous strategy, the trajectories of the excess of lubricant precursors consumed under supercritical conditions also follow a hyperbolic increase. The profile is horizontally bound, asymptotically approaching 100% excess as the supply rate (

) increases (

Figure 8). The minimum excess of lubricant precursors approximates 0%, which represents the critical condition at

(

Figure 8).

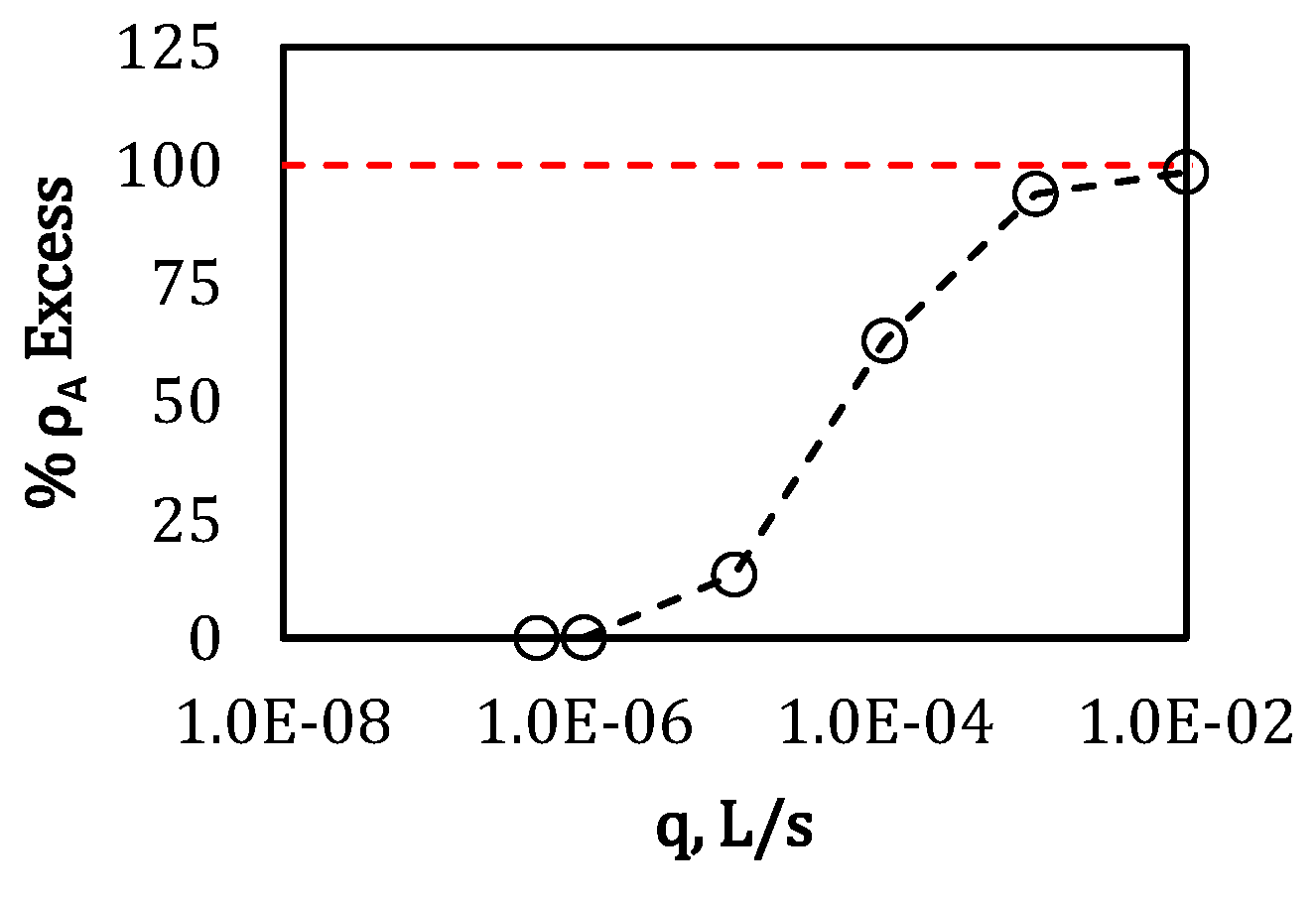

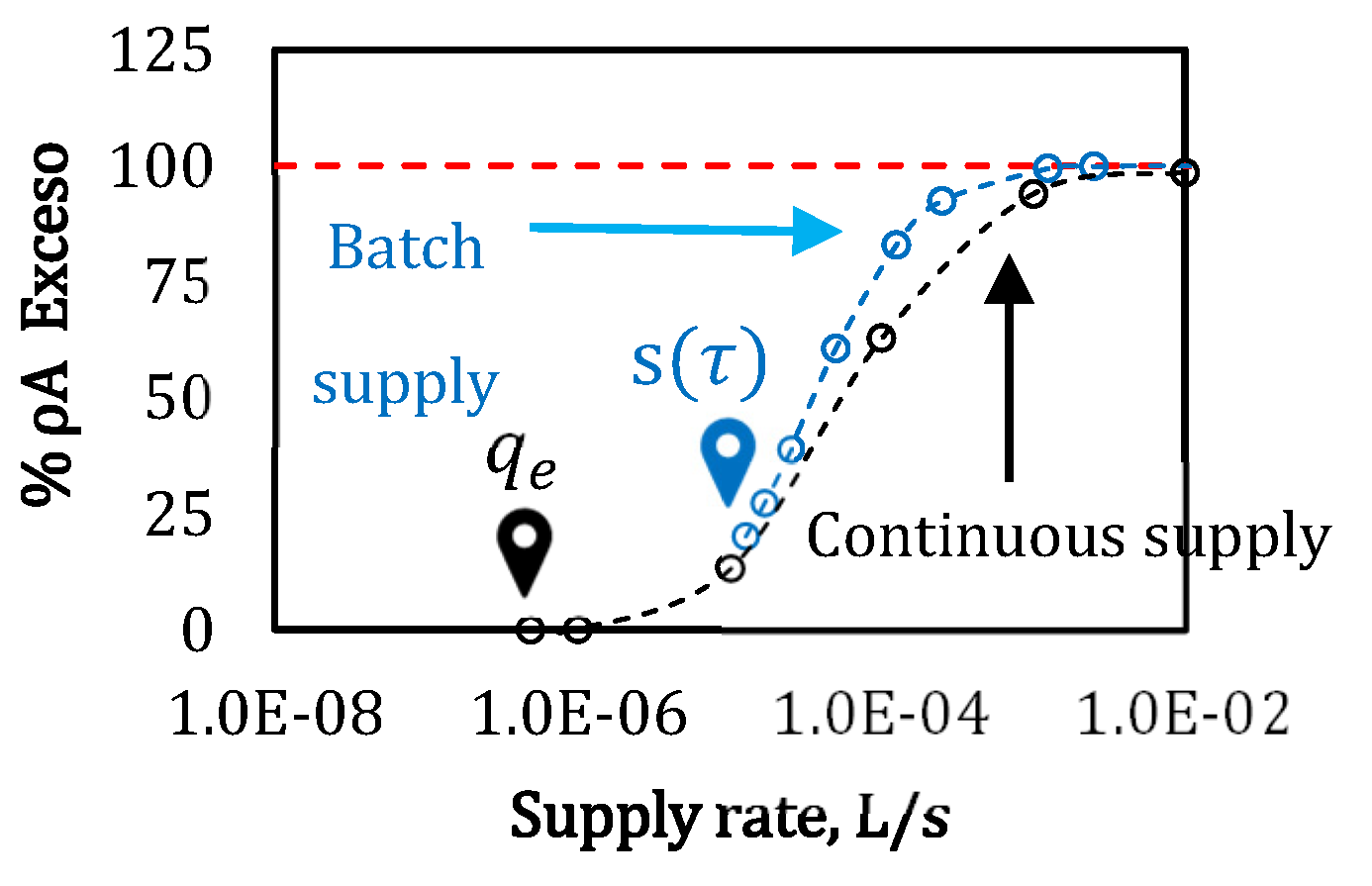

3.6. Comparison of lubricant economy for supercritical conditions

By comparing the minimum excess of lubricant precursors consumed in the batch (20%) and continuous (0%) strategies, it is evident that, under critical conditions, the batch strategy consumes more lubricant precursors than the continuous strategy (

Figure 9).

Moreover, the minimum lubricant consumption occurs at different supply rates:

for batch lubrication and

for continuous lubrication. Therefore, the continuous strategy enables the lubrication system to operate at supply rates significantly lower than those required by the batch strategy (

Figure 9).

For equivalent supply rates (

and

), the calculated values for

for the batch strategy consistently follow a trend located above that of the continuous strategy. This behavior indicates that, even when both systems operate at the same supply rate, the batch strategy inherently requires more lubricant precursors to maintain the lubrication conditions. In other words, the batch lubrication system is less efficient in precursor utilization than the continuous system (

Figure 9).

4. Discussion

4.1. Technical comparison of the base cases

The results obtained for both base cases (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) clearly highlight the operational and economic differences between the batch and continuous lubrication strategies. In the batch system, lubricant replacement occurs in discrete intervals, which guarantees a complete renewal of the lubricant properties after each cycle but leads to substantial precursor consumption and periodic loss of film stability. In contrast, the continuous system maintains the lubricant properties through a steady inflow of fresh oil and simultaneous discharge of degraded lubricant, achieving a more uniform film thickness and significantly lower total consumption.

Quantitatively, the continuous strategy reduced lubricant consumption by approximately 86% compared to the batch strategy during 1000 h of operation (

Figure 5). This improvement stems from the ability of the continuous system to sustain steady-state concentrations of lubricant precursors, while the batch system experiences complete depletion at the end of each operating period. Thus, the continuous strategy demonstrates higher efficiency and film stability, whereas the batch strategy remains simpler to operate but less efficient in precursor utilization.

The steady-state behavior observed for the continuous lubrication strategy is consistent with previous tribological studies reporting improved film stability under controlled and continuous supply conditions, particularly in boundary and elastohydrodynamic contacts [

10,

13,

14,

17,

18]. However, most of these studies primarily focus on friction coefficients or film thickness evolution, without explicitly accounting for lubricant precursor depletion or excess consumption. In this context, the present model extends existing approaches by incorporating an explicit mass balance of lubricant precursors, enabling a direct comparison of lubrication strategies from both economic and material-efficiency perspectives.

4.2. Influence of the kinetic constant and film removal rate

The sensitivity analysis (

Figure 6) showed that both the kinetic constant (

) and the film removal rate (

) exert a direct influence on the lubricant supply rates of both strategies. Increasing

enhances the regeneration of the lubricating film, thereby lowering the required make-up rate when

is moderate. However, excessive values of

may accelerate precursor depletion without proportional gains in tribofilm durability, thereby diminishing overall lubrication efficiency, as also suggested by model-based studies on additive consumption [

17,

19,

20].

Conversely, an increase in provokes higher supply requirements due to the accelerated detachment of the lubricating film. The combined effect of these parameters defines the feasible operation region described by (Equation 18). Within this region, the continuous strategy always exhibits lower supply demands than the batch system. To improve efficiency, the system design should aim to minimize —for example, by optimizing surface topography or reducing mechanical shear—and to select lubricants with kinetic constants balanced to sustain steady film renewal avoiding overconsumption of precursors.

Trends associating higher film removal rates with increased lubricant demand have also been reported in experimental studies addressing additive depletion and tribofilm wear under severe contact conditions [

14,

15,

20,

21]. However, these studies generally provide qualitative assessments of film loss without explicitly linking removal kinetics to lubricant supply requirements. In this regard, the present sensitivity analysis offers a quantitative framework that connects film removal mechanisms with lubricant consumption, enabling a more systematic comparison of lubrication strategies.

4.3. Expected effects of varying additional system parameters

Although the present study focused primarily on

and

, other system parameters can also influence lubrication performance. Increasing the concentration of active precursors in the fresh lubricant (

) would extend the period of effective film protection but could also increase viscosity and alter flow distribution in the oil circuit, potentially affecting additive transport and degradation pathways [

19,

20].

Similarly, modifying the lubricant exchange rate between the oil pan and the engine interior may provide a means to fine-tune the balance between regeneration and removal of the lubricating film. Higher exchange rates could accelerate precursor homogenization and improve the responsiveness of the system to degradation, while lower rates would favor lower overall consumption. These aspects represent promising directions for future optimization of lubricant formulations and circulation design, as previously discussed in recent lubrication modeling and system-level analyses [

12,

21].

Finally, recent advances in smart lubrication systems and adaptive oil management indicate that continuous supply strategies can be dynamically optimized in real time by adjusting make-up rates according to operating conditions and lubricant health indicators [

12]. Within this context, the present mass-balance framework provides a quantitative theoretical basis for such adaptive control strategies, linking lubricant chemistry, tribofilm evolution, and supply management [

18,

21].

4.4. Practical applicability of each lubrication strategy

Each lubrication strategy presents advantages under specific operational contexts. The batch system is suitable for conventional engines where lubricant replacement intervals are already established, and maintenance accessibility is straightforward. Its simplicity and robustness make it the appropriate choice for small- to medium-scale systems or laboratory setups. The continuous system, on the other hand, is better suited to long-duration or high-performance applications—such as heavy-duty engines, turbines, or closed-loop systems—where lubricant degradation must be minimized, and operational interruptions are undesirable.

Beyond these operational considerations, the choice between both strategies involves a trade-off of control complexity, material efficiency, and maintenance logistics. The findings presented here demonstrate that continuous lubrication systems can significantly reduce lubricant consumption and precursor waste, contributing to both economic and environmental sustainability.

From an economic perspective, this material efficiency translates directly into lower operational costs and reduced waste-management requirements. For instance, considering the base cases comparison (

Figure 5), the continuous strategy could save up to 86% of the lubricant volume otherwise required by the batch strategy. Assuming similar lubricant unit costs, this difference implies not only monetary savings but also reduced logistics associated with lubricant storage, handling, and disposal. Additionally, maintaining stable film thickness reduces the frequency of maintenance interventions and engine downtime, further enhancing the cost-effectiveness of the continuous lubrication strategy. These benefits align with global assessments identifying friction and lubrication losses as major contributors to energy consumption and operating costs in mechanical systems [

22].

It is worth noting that, although batch lubrication remains the dominant practice in commercial internal combustion engines due to its simplicity and well-established maintenance protocols, continuous lubrication concepts have already been explored in heavy-duty machinery, marine engines, and closed-loop industrial systems [

11,

12]. In this context, the present results provide quantitative support for extending continuous lubrication strategies to internal combustion engine applications, particularly under long-duration or high-demand operating conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the economics of batch and continuous lubricant supply strategies in internal combustion engines. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

The batch strategy is simpler to implement but less efficient in precursor utilization.

The continuous strategy provides higher efficiency and improved film stability due to its steady state operation.

Excessive increases in the kinetic constant or the film removal rate

negatively affect the lubricant supply rate requirements of both strategies.

Continuous lubrication systems can substantially reduce lubricant consumption and precursor waste, contributing to both economic and environmental sustainability; however, their application must be limited to appropriate operating conditions.

Future research should extend the present modeling framework toward experimental validation under controlled laboratory and operating conditions, as well as exploring the influence of precursor depletion on the lubricant’s long-term physicochemical stability.

Author Contributions

SD-G.; Conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, project administration, MP-L.; methodology, resources, AL-V.; validation, resources, MA-EM.; validation, resources, supervision, RM-Y.; Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data were generated as shown in the manuscript, references were used as described in the Discussion section.

Acknowledgments

Authors greatly thanks the economic support by the grant 20315 from the “Sistema Nacional de Investigadores e Investigadoras (SEHICTI)” and the kind accompaniment by the project 20.20 from the “CIC-UMSNH”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A |

agglomerate of additives contained in the lubricant formula. |

| F |

deposited molecules forming the solid film. |

|

internal surface of the engine. |

| χ |

thickness of the film. |

| Xmax |

maximum thickness of separation between the shearing surfaces. |

| Xmin |

minimum thickness required to avoid direct contact of the surface roughness. |

|

control volume within the oil pan. |

|

control volume of the engine. |

|

sum of the engine control volume and the oil pan control volume. |

| u |

volumetric flow rate between the oil pan and the engine interior |

| q |

volumetric flow rate of fresh lubricant and of purge. |

|

. |

|

minimum lubricant make-up rate required to form the equilibrium film. |

|

concentration of precursors A in the fresh lubricant. |

|

partial density of precursors A inside the engine. |

|

partial density of precursors A inside the oil pan. |

|

amount of lubricant film deposited inside the engine. |

|

critical partial densities of precursors A within the engine. |

|

critical partial densities of precursors A in the oil pan. |

|

actual density of the deposited film |

|

. |

|

film mass. |

|

kinetic constant of the reaction of A inside the engine. |

|

removal base rate. |

| σ |

growing constrain |

| ς |

ratio between the film thickness χ and the minimum thickness required to avoid direct surface-to-surface contact. |

| τ |

limited operating period in the batch supply strategy. |

|

excess in consumed lubricant precursors. |

|

time step. |

References

- Neuhausen, J.B.; Riedl, J.-H.; Ploetz, W.; Müller, M.; Popp, P.; Langenmayr, S.; Faltenbacher, F.; Gruschwitz, T. European Fleet Electrification: From Electric Vehicle Sales to a Complete Fleet Transition; Strategy&, PwC and Fraunhofer ISI: Munich, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://www.isi.fraunhofer.de.

- Business Research Insights. Internal Combustion Engine Market: Global Analysis by 2035; Business Research Insights: Pune, India, 2024. Available online: https://www.businessresearchinsights.com/market-reports/internal-combustion-engine-market-119484.

- Fortune Business Insights. Internal Combustion Engine Market Size, Share and Industry Report, 2023–2032; Fortune Business Insights: Pune, India, 2023. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/internal-combustion-engine-market-112866.

- Mordor Intelligence. Global Internal Combustion Engines Market: Size and Share Analysis (2024–2029); Mordor Intelligence: Hyderabad, India, 2024. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/global-internal-combustion-engines-market.

- Holmberg, K.; Andersson, P.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction in passenger cars. Tribol. Int. 2012, 47, 221–234. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Erdemir, A. Influence of tribology on global energy consumption, costs and emissions. Friction 2017, 5, 263–284. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, J.; Cayer-Barrioz, J.; Mazuyer, D. Transition between mixed lubrication and elastohydrodynamic lubrication with randomly rough surfaces. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 64, 33. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Béjar-Gómez, L.; Huirache-Acuña, R.; Lara-Romero, J.; Maya-Yescas, R. Delumping strategy to infer lubrication reaction pathways in internal combustion engines. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2020, 18, 20190043. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Aguilar-Ramírez, C.E.; Béjar-Gómez, L.; Maya-Yescas, R. Mass balance of the tribofilm in lubricated systems. Tribol. Int. 2021, 155, 106757. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Q.J.; Chung, Y.W.; Berkebile, S. Lubrication–contact interface conditions and novel mixed/boundary lubrication modeling methodology. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 142. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Béjar-Gómez, L.; López-Velázquez, A.; Maya-Yescas, R.; Nápoles-Rivera, F. Maximizing lubricant life for internal combustion engines. Processes 2022, 10, 2070. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Maya-Yescas, R.; Béjar-Gómez, L. Reduction of lubricant life in lubrication systems for internal combustion engines due to high lubricant supply rates. Mater. Lett. 2022, 313, 131785. [CrossRef]

- Dawczyk, J.; Morgan, N.; Russo, J.; Spikes, H. Film thickness and friction of ZDDP tribofilms. Tribol. Lett. 2019, 67, 50. [CrossRef]

- Khaemba, D.N.; Jarnias, F.; Thiebaut, B.; Neville, A.; Morina, A. The role of surface roughness and slide–roll ratio on the decomposition of MoDTC in tribological contacts. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 085302. [CrossRef]

- Liñeira del Río, J.M.; Guimarey, M.J.G.; Prado, J.I.; Lugo, L.; López, E.R.; Comuñas, M.J.P. Improving the tribological performance of a biodegradable lubricant by adding graphene nanoplatelets as additives. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 345, 117797. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Béjar-Gómez, L.; Maya-Yescas, R.; Lara-Romero, J.; Castro-Cedeño, B.; Espinosa-Medina, M.A. Friction coefficient dynamics of tribological coatings from engine lubricants: Analysis and interpretation. Coatings 2023, 13, 1753. [CrossRef]

- Spikes, H. The behaviour of lubricants in elastohydrodynamic contacts. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 469–489.

- Taylor, L.J.; Spikes, H.A. Friction-enhancing properties of ZDDP antiwear additive. Tribol. Trans. 2003, 46, 303–309. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Spikes, H.; Jensen, R.K. Modelling additive depletion in lubricated contacts. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 164–177.

- Minami, I. Molecular science of lubricant additives. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8723–8730. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.M.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Z. The nature and origin of tribochemistry. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 56, 1–12.

- Kajdas, C.; Kulczycki, A.; Wilusz, E. Monitoring lubricant condition and tribofilm evolution in boundary lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2015, 82, 195–204.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).