Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Construction and Validation of DNA Vaccines

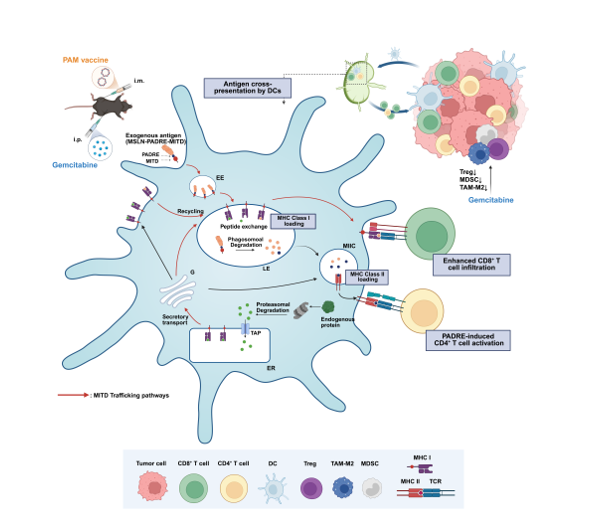

2.2. The Incorporation of MITD Significantly Enhances the Immunogenicity of DNA Vaccines

2.3. PADRE-MITD Exhibits Superior Antitumor Efficacy Compared with P2P16-MITD in a Murine Pancreatic Cancer Model

2.4. PAM Induces Relatively Weaker Immunosuppression in Tumor Microenvironment

2.5. Combination Therapy with Gem Elevated the Antitumor Efficacy of PAM

2.6. PAM Combined with Gemcitabine Further Reduces Immunosuppression in Tumor Microenvironment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Cell Lines

4.2. Vaccine Construction

4.3. Protein Purification

4.4. In Vivo Immune Strategies

4.5. Preparation of Single-Cell Suspension

4.6. IFN-γ ELISpot Assays

4.7. Cell Staining and Flow Cytometry

4.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rojas, L.A.; et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 618(7963), 144-+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71(3), 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Yazdian-Robati, R.; Behravan, J. HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Immunotherapy: A Focus on Vaccine Development. Archivum Immunologiae Et Therapiae Experimentalis 2020, 68(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiter, S.; et al. Increased antigen presentation efficiency by coupling antigens to MHC class I trafficking signals. Journal of Immunology 2008, 180(1), 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewdell, J.W. Not such a dismal science: the economics of protein synthesis, folding, degradation and antigen processing. Trends in Cell Biology 2001, 11(7), 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewdell, J.W.; Reits, E.; Neefjes, J. Making sense of mass destruction: Quantitating MHC class I antigen presentation. Nature Reviews Immunology 2003, 3(12), 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. MHCI trafficking signal-based mRNA vaccines strengthening immune protection against RNA viruses. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2025, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizée, G.; et al. Control of dendritic cell cross-presentation by the major histocompatibility complex class I cytoplasmic domain. Nature Immunology 2003, 4(11), 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizée, G.; Basha, G.; Jefferies, W.A. Tails of wonder: endocytic-sorting motifs key for exogenous antigen presentation. Trends Immunol 2005, 26(3), 141–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blander, J.M. Different routes of MHC-I delivery to phagosomes and their consequences to CD8 T cell immunity. Seminars in Immunology 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; et al. MHC class I trafficking signal improves induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte using artificial antigen presenting cells. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, G.; et al. MHC Class I Endosomal and Lysosomal Trafficking Coincides with Exogenous Antigen Loading in Dendritic Cells. Plos One 2008, 3(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengjel, J.; et al. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102(22), 7922–7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm-Okita, B.M.; et al. Epitope repertoire of human CD4+ T cells on tetanus toxin: identification of immunodominant sequence segments. The Journal of infectious diseases 1997, 175(2), 382–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, R.; et al. Epitope repertoire of human CD4+ lines propagated with tetanus toxoid or with synthetic tetanus toxin sequences. Journal of autoimmunity 1996, 9(1), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature 2020, 585(7823), 107+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; et al. The optimization of helper T lymphocyte (HTL) function in vaccine development. Immunologic Research 1998, 18(2), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.; et al. Development of high potency universal DR-restricted helper epitopes by modification of high affinity DR-blocking peptides. Immunity 1994, 1(9), 751–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, M.; et al. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nature Reviews Cancer 2021, 21(6), 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Bera, T.; Pastan, I. Mesothelin: A new target for immunotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2004, 10(12), 3937–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Ho, M. Mesothelin targeted cancer immunotherapy. European Journal of Cancer 2008, 44(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.C.; et al. Mesothelin-specific cell-based vaccine generates antigen-specific immunity and potent antitumor effects by combining with IL-12 immunomodulator. Gene Therapy 2016, 23(1), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; et al. Anti-mesothelin CAR-T immunotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 2023, 72(2), 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, N.L.; et al. An anti-mesothelin targeting antibody drug conjugate induces pyroptosis and ignites antitumor immunity in mouse models of cancer. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2023, 11(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, R.E.; Jansen, K. Turning the corner on therapeutic cancer vaccines. Npj Vaccines 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahm, C.D.; Colluru, V.T.; McNeel, D.G. DNA vaccines for prostate cancer. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017, 174, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; et al. MSLN induced EMT, cancer stem cell traits and chemotherapy resistance of pancreatic cancer cells. Heliyon 2024, 10(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; et al. Mesothelin regulates growth and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through p53-dependent and -independent signal pathway. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2012, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Jiang, A. Dendritic Cells and CD8 T Cell Immunity in Tumor Microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; et al. The XCL1-Mediated DNA Vaccine Targeting Type 1 Conventional Dendritic Cells Combined with Gemcitabine and Anti-PD1 Antibody Induces Potent Antitumor Immunity in a Mouse Lung Cancer Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, M.; et al. OMTX705, a Novel FAP-Targeting ADC Demonstrates Activity in Chemotherapy and Pembrolizumab-Resistant Solid Tumor Models. Clinical Cancer Research 2020, 26(13), 3420–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.M.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of sibrotuzumab in patients with advanced or metastatic fibroblast activation protein-positive cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2003, 9(5), 1639–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.L.; et al. Fast DNA Vaccination Strategy Elicits a Stronger Immune Response Dependent on CD8+CD11c+ Cell Accumulation. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, N.R.; et al. p53-Reactive T Cells Are Associated with Clinical Benefit in Patients with Platinum-Resistant Epithelial Ovarian Cancer After Treatment with a p53 Vaccine and Gemcitabine Chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 24(6), 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natu, J.; Nagaraju, G.P. Gemcitabine effects on tumor microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Special focus on resistance mechanisms and metronomic therapies. Cancer Letters 2023, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B.L.; Takabe, K. Biology of Mesothelin and Clinical Implications: A Review of Existing Literature. World Journal of Oncology 2023, 14(5), 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avula, L.R.; et al. Mesothelin Enhances Tumor Vascularity in Newly Forming Pancreatic Peritoneal Metastases. Molecular Cancer Research 2020, 18(2), 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, F.K.; et al. DNA fusion vaccines enter the clinic. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 2011, 60(8), 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeli, P.; et al. DNA vaccines against GPRC5D synergize with PD-1 blockade to treat multiple myeloma. Npj Vaccines 2024, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrends, T.; et al. CD4+ T Cell Help Confers a Cytotoxic T Cell Effector Program Including Coinhibitory Receptor Downregulation and Increased Tissue Invasiveness. Immunity 2017, 47(5), 848+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.P.; et al. Differences in Tumor Microenvironment Dictate T Helper Lineage Polarization and Response to Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cell 2019, 179(5), 1177+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.S.; El-Sukkari, D.; Villadangos, J.A. Dendritic cells constitutively present self antigens in their immature state in vivo and regulate antigen presentation by controlling the rates of MHC class II synthesis and endocytosis. Blood 2004, 103(6), 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, P.A.; Furuta, K. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nature Reviews Immunology 2015, 15(4), 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.K.; et al. Gemcitabine directly inhibits myeloid derived suppressor cells in BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 mammary carcinoma and augments expansion of T cells from tumor-bearing mice. International Immunopharmacology 2009, 9(7-8), 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, E.; et al. Gemcitabine reduces MDSCs, tregs and TGFβ-1 while restoring the teff/treg ratio in patients with pancreatic cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevchenko, I.; et al. Low-dose gemcitabine depletes regulatory T cells and improves survival in the orthotopic Panc02 model of pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Cancer 2013, 133(1), 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).