1. Introduction

Daily exposure to a wide range of xenobiotics, including pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and food additives, necessitates efficient biotransformation processes to prevent clinically relevant adverse effects. The main metabolic detoxification pathways are organized into Phase I (functionalization) and Phase II (conjugation), whose purpose is to increase the hydrophilicity of compounds and reduce their toxicity, thereby facilitating their elimination via bile or urine [

1]. During Phase I, the cytochrome P450 enzyme family constitutes the first line of defense against xenobiotics by introducing reactive functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amino groups through oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis reactions. In Phase II, the metabolites generated are conjugated with hydrophilic molecules through specific enzymes, including glucuronosyltransferases (glucuronic acid), sulfotransferases (sulfate), amino acid transferases, N-acetyltransferases (acetyl group), methyltransferases (methyl group), and glutathione S-transferases (glutathione), thereby increasing their solubility and promoting their excretion. Some xenobiotics may bypass Phase I and be directly metabolized by Phase II enzymes [

2], whereas others require only Phase I reactions for their elimination [

3].

Polymorphisms in genes encoding xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes can substantially alter enzymatic activity, with significant implications for chemical clearance, systemic exposure, and internal dose [

4]. This topic has been widely explored in pharmacological research, where genetic variability contributes to adverse drug reactions and explains interindividual variability in drug biotransformation and therapeutic outcomes [

5]. Among these enzymes, glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), particularly GST Mu 1 (

GSTM1) and GST theta 1 (

GSTT1), are of special relevance. Both genes harbor deletion variants (null genotypes) that can lead to a complete loss of enzymatic activity, with potentially significant clinical implications. In the literature, these variants have been primarily associated with various cancer types, as well as with therapeutic areas including neuropsychiatry, gastroenterology, respiratory diseases, gynecology, infectious diseases, and cardiology [

6]. Furthermore,

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes have been reported to contribute to variability in the safety and efficacy of drugs such as antiepileptics, immunosuppressants, chemotherapeutic agents, analgesics, and anti-infective agents [

2,

7].

The frequency of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes varies according to ethnicity and continental ancestry, suggesting population-related differences in susceptibility to clinical effects associated with these polymorphisms [

8]. However, the literature indicates a marked underrepresentation of non-European populations in studies of these genes, resulting in a knowledge gap that restricts progress toward more equitable and inclusive precision medicine [

6]. This challenge is further intensified by the possibility that certain variants or rare alleles may be restricted to specific ethnic groups and remain unidentified.

Studies investigating the frequency of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes in populations from the Americas remain limited, accounting for less than 1% of the articles included in a systematic review published in 2022 [

6]. In Peru, no previous studies have examined Andean populations, as existing research has been confined to coastal populations [

9,

10,

11,

12]. In this context, the aim of the present study was to determine the frequency of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes in Andean populations of Peru. Identifying these genotypes may contribute to public health decision-making by providing locally relevant evidence to support the implementation of more equitable and effective policies in rural and vulnerable populations.

2. Results

The distribution of GST genotype frequencies among Peruvian Andean individuals is summarized in

Table 1. In the overall cohort (n = 206),

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 deletions were observed in 49.51% and 25.24% of individuals, respectively. When genotype distributions were assessed by region, the frequency of the

GSTM1 null genotype was comparable between Cusco and Junín (46.43% vs. 56.08%,

p = 0.197). Similarly, no statistically significant differences were detected in the frequency of the

GSTT1 null genotype between the two regions (22.14% vs. 31.82%,

p = 0.139).

Analysis of the combined distribution of GST genotypes revealed that 11.65% of participants carried simultaneous null genotypes for both GSTM1 and GSTT1, whereas 63.11% exhibited at least one null genotype. When these patterns were examined by region, no statistically significant differences were observed between Cusco and Junín, either for the presence of both null genotypes (9.29% vs. 16.67%, p = 0.124) or for the presence of at least one null genotype (59.29% vs. 71.21%, p = 0.094).

Comparative analyses were conducted between the Peruvian Andean population included in this study and several reference populations (

Table 2). No statistically significant differences were observed in the frequencies of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes between our Andean cohort and the Peruvian coastal population.

When comparing our cohort with other populations across the American continent, the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype was comparable to those reported in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and northern Mexico; however, it was significantly higher than the frequencies observed in populations from Colombia and central Mexico. Regarding the GSTT1 null genotype, the frequencies observed in our population were comparable to those reported in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela, but were higher than those documented in Argentina, Chile, and Mexico.

When extending the comparison to populations from other continents, the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype in our cohort was similar to that reported in populations from Europe, North Africa, North–Central–East Asia, and the Middle East. In contrast, a higher frequency was observed compared with populations from Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Native American groups. For the GSTT1 null genotype, our cohort exhibited frequencies comparable to those described in Europe, North–South–Central Asia, and the Middle East, while showing lower frequencies than those reported in Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and East Asia, but higher frequencies relative to Native American populations.

3. Discussion

This study represents the first description of the frequencies of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes in Andean populations of Peru, addressing a critical knowledge gap regarding genetic variability associated with xenobiotic metabolism in rural and historically underrepresented Latin American populations. This contribution is particularly relevant for advancing precision medicine on a global scale, with an emphasis on equity and inclusion [

6]. Our results indicate that the distribution of null genotypes in the Andean population was relatively higher for

GSTM1 (49.51%) than for

GSTT1 (25.24%), a pattern consistent with that observed in the majority of previously reported populations (

Table 2).

The lack of significant differences in the frequencies of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes between Cusco (southeastern Andes) and Junín (central Andes) indicates a genetically homogeneous distribution of these polymorphisms among the high-Andean populations studied. This finding is consistent with previous evidence of strong genetic continuity across Peruvian high-Andean regions, as demonstrated by both targeted genetic polymorphism analyses [

13] and higher-resolution genomic studies [

14], reflecting the shared demographic history characteristic of these populations. Moreover, the high proportion of individuals carrying at least one null genotype (63.11%) suggests a potential population-level reduction in detoxification capacity, which may have clinically relevant implications in the context of frequent environmental and pharmacological exposures in rural settings [

2,

7,

15]. In this context, the elevated prevalence of null genotypes in the Andean population underscores the need to generate locally relevant evidence to guide public health strategies, environmental surveillance, and precision medicine approaches tailored to these communities. Moreover, this high prevalence highlights the importance of conducting association studies to evaluate the contribution of these genotypes to disease susceptibility, given the extensive evidence linking

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes to an increased risk of multiple pathologies, particularly cancer-related conditions [

6].

Comparisons with previously studied populations showed that the frequencies of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes in the Andean cohort were similar to those reported in Peruvian coastal populations, suggesting that despite geographical and sociohistorical differences, these polymorphisms do not exhibit marked population structure between these regions. This pattern contrasts with findings for other genetic markers, for which population structure has been observed according to the geographical regions of Peru [

16]. These results indicate that studies with broader population coverage are needed to determine whether the uniform distribution of these genotypes reflects intrinsic evolutionary patterns or more recent processes of population admixture.

At the continental level, the frequencies of the

GSTM1 null genotype in our Andean population were comparable to those reported in most South American countries and in northern Mexico. Likewise,

GSTT1 null genotype frequencies were consistent with the South American pattern described in countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela. Differences in

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotype frequencies between our Andean cohort and certain populations across the Americas may be attributable to latitudinal variation, as the frequency of the

GSTM1 null genotype increases with absolute latitude, whereas that of the

GSTT1 null genotype decreases [

8].

Comparatively, the frequencies reported in this study also fall within the range documented for populations from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, but differ from the prevalences reported in Sub-Saharan African and Native American populations. These patterns are consistent with the variability described in global reviews, which report wide ranges of deletion frequencies for both genes according to continental and ethnic origin [

6]. Collectively, these findings reinforce the notion that the distribution of

GSTM1 and

GSTT1 null genotypes is not determined solely by national-level geographic criteria, but rather instead a global pattern shaped by evolutionary history, migration, population admixture, and selective pressures.

Overall, our findings provide the first evidence on the distribution of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes in Andean populations of Peru, helping to address a critical genetic information gap in historically underrepresented groups. Although this study was limited by a moderate sample size and the inclusion of only two Andean regions, these constraints do not compromise the validity of the initial genetic characterization or the consistency of the observed patterns. The absence of functional enzymatic assays or gene expression analyses represents a limitation; however, deletion polymorphisms in GSTM1 and GSTT1 are well-established loss-of-function variants. Rather than detracting from the significance of the study, these limitations highlight the need for future research incorporating larger and more geographically diverse populations, genome-wide approaches, and integrated gene–environment analyses. Such efforts will be essential to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the functional and clinical implications of these polymorphisms and to support the development of public health interventions and precision medicine strategies tailored to the genetic and environmental context of high-Andean communities.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

A cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes among individuals. Participants were recruited from six localities in the Cusco and Junín regions, comprising a total of 206 individuals selected through regional health centers and local community outreach. Individuals with known chronic liver disease or prior chemotherapy were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from each subject before the study. This study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Universidad Continental of Peru (N°047-2024-CIEI-UC) and follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

4.2. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Peripheral blood samples (3 mL) were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes and stored at -80 °C until processing. Genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocols. DNA purity and concentration were evaluated using a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and DNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

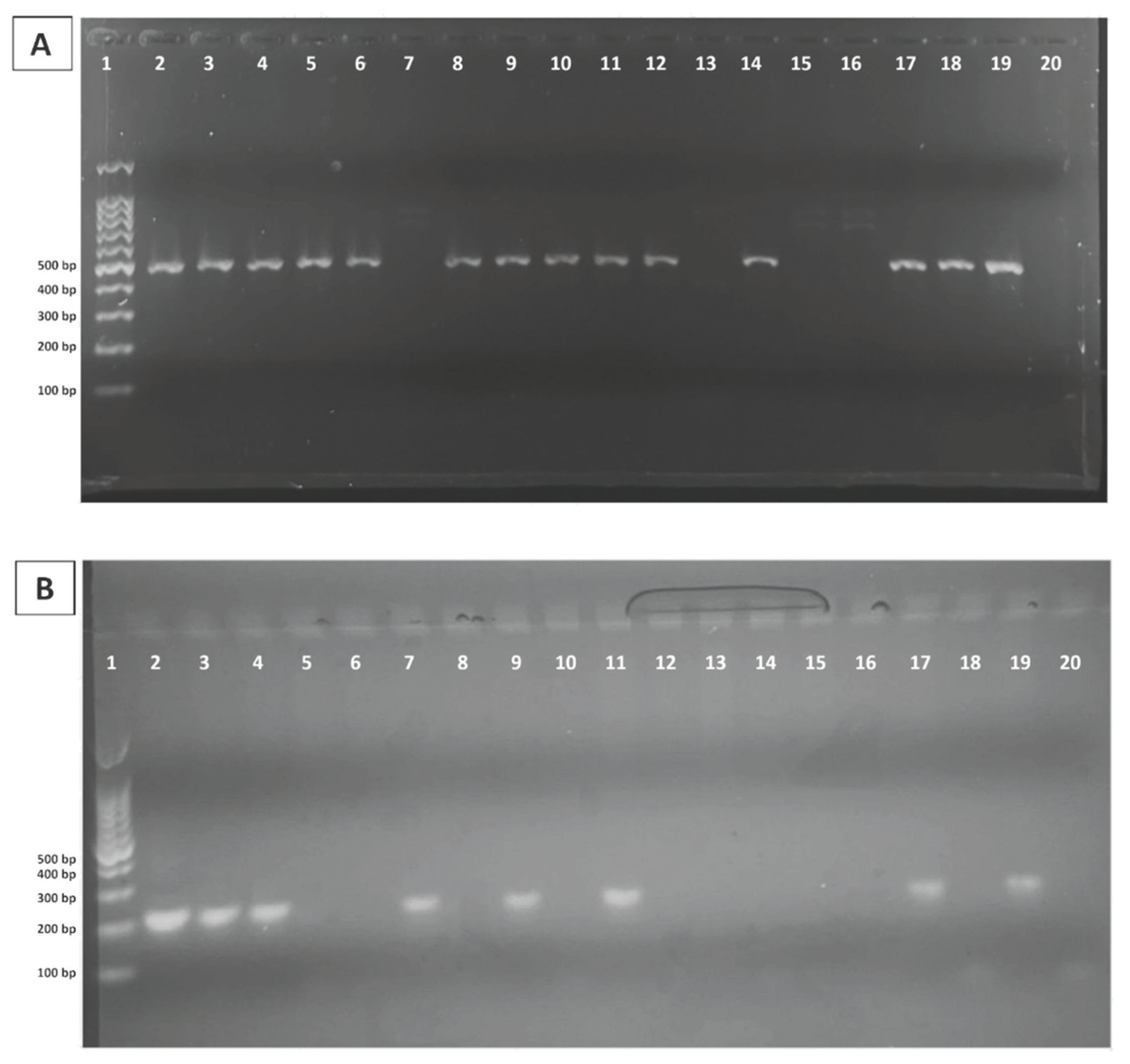

4.3. Genotyping Analysis

The selected genomic DNA regions for the analysis of each gene included

GSTT1 and

GSTM1 genes. These regions were amplified by PCR using the Platinum™ Taq DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and the following primers: 5’-GAACTCCCTGAAAAGCTAAAGC-3’ and 5’-GTTGGGCTCAAATATACGGTGG-3’ for the

GSTM1 gene and the specific primers 5 ’-TTCCTTACTGGTCCTCACATCTC-3’ and 5’-TCACCGGATCATGGCCAGCA-3’ for the

GSTT1 gene [

12]. Each PCR reaction consisted of 100 ng of genomic DNA and 0.2 µM of each primer in a final volume of 50 µL, including 45 µL of Platinum™ PCR SuperMix. Amplified products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel prepared in 1X TAE buffer and stained with GelRed

® (Biotium, CA, USA). Amplicons of approximately 215 bp for

GSTM1 and 480 bp for

GSTT1 confirmed the presence of the corresponding genes, consistent with present genotypes, whereas the absence of amplification indicated null genotypes associated with homozygous deletions (

Figure 1). An internal amplification control was included to avoid false-negative results due to PCR failure.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Chi-square test was used, or when necessary, the Fisher exact test to check the differences in genotype frequencies. Given the descriptive and exploratory nature of this molecular epidemiological study, no multivariate modeling was performed. Data analysis was performed using Stata v15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) considering a statistical significance of p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first characterization of GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotype frequencies in Andean populations of Peru, revealing a high prevalence of variants associated with reduced detoxification capacity and a homogeneous distribution of these polymorphisms between Cusco and Junín. In historically underrepresented high-altitude populations, these results provide a crucial population-specific genetic baseline for xenobiotic metabolism. Future functional research, gene–environment interaction analysis, and the creation of precision medicine and public health policies suited to the genetic and environmental context of Andean communities are all supported by this work, which fills a large gap in global pharmacogenetic data.

Author Contributions

Study design: L.J.-V. and M.G.-P. Performed the experiments: M.G.-P., C.C.-S., Z.C.-D. and M.M.-R. Analyzed the data: M.G.-P., R.E.-L., S.J.S. and L.J.-V. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was funded by the Universidad Continental under the institutional funding framework established by Resolution No. 4412-2024-R/UC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Universidad Continental of Peru (N°047-2024-CIEI-UC).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of local health authorities and participants in Cusco and Junin, Peru.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hodges, R. E.; Minich, D. M. Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. J. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 2015, 760689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettoury, S.; Louati, S.; Saad, I.; Bentayebi, K.; Zarrik, O.; Bourkadi, J. E.; Belyamani, L.; Daali, Y.; Eljaoudi, R. Association of GST Polymorphism with Adverse Drug Reactions: An Analysis across Multiple Drug Categories. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2025, 21(2), 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, A. Z.; Park, S. B.; Kocz, R. Drug Elimination. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547662/.

- Ginsberg, G.; Guyton, K.; Johns, D.; Schimek, J.; Angle, K.; Sonawane, B. Genetic Polymorphism in Metabolism and Host Defense Enzymes: Implications for Human Health Risk Assessment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40(7), 575–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Álvarez, L.; Cordero-Ramos, J.; Calleja-Hernández, M. Á. [Artículo Traducido] Exploración Del Impacto de La Farmacogenética En La Medicina Personalizada: Una Revisión Sistemática. Farm. Hosp. 2024, 48(6), T299–T309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, G.; Pita-Oliveira, M.; Bertagnolli, L. S.; Torres-Loureiro, S.; Scudeler, M. M.; Cirino, H. S.; Chaves, M. L.; Miwa, B.; Rodrigues-Soares, F. Worldwide Systematic Review of GSTM1 and GSTT1 Null Genotypes by Continent, Ethnicity, and Therapeutic Area. OMICS 2022, 26(10), 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugrahaningsih, D. A. A.; Wihadmadyatami, H.; Widyarini, S.; Wijayaningsih, R. A. A Review of the GSTM1 Null Genotype Modifies the Association between Air Pollutant Exposure and Health Problems. Int. J. Genomics 2023, 2023, 4961487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, M.; Ishida, T. Distributions of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 Null Genotypes Worldwide Are Characterized by Latitudinal Clines. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16(1), 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A. T.; Saravia-Bartra, M.; Malpartida-Palomino, R.; Cárdenas-Guerrero, C. C.; García, J. A.; Bendezú, M. R.; Chávez, H.; Laos-Anchante, D.; Palomino-Jhong, J. J.; Molina-Cabrera, A.; Cuba-Garcia, P.; Melgar-Merino, E. J.; Vega-Ramos, N.; Surco-Laos, F.; Yarasca-Carlos, P. E.; Varela, N.; Quiñones, L. A.; Cáceres-Lillo, D. D.; Zavaleta, A. I.; Pineda-Pérez, M. CYP1A1 and GSTM1 genes associated with the risk of developing colorectal cancer: a case-control study in the Lima region of Peru. Farmatsiia (Sofia) 2025, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A. T.; Salazar-Granara, A.; Varela, N.; Quiñones, L. A.; Li-Amenero, C.; Bendezú, M. R.; García, J. A.; Surco-Laos, F.; Chávez, H.; Palomino-Jhong, J. J.; Laos-Anchante, D.; Melgar-Merino, E. J.; Cuba-García, P. A.; Bonifaz-Hernández, M.; Almeida-Galindo, J. S.; Pineda-Pérez, M.; Bolarte-Arteaga, M.; Pariona-Llanos, R. Prevalence of GSTM1*0 and CYP1A1*2A (rs4646903) variants in the central Peruvian coastal population: Pilot Study of predictive genetic biomarkers for 4P medicine. Farmatsiia (Sofia) 2025, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A. T.; Muñoz, A. M.; Bartra, M. S.; Valderrama-Wong, M.; González, D.; Quiñones, L. A.; Varela, N.; Bendezú, M. R.; García, J. A.; Loja-Herrera, B. Frequency of CYP1A1*2A polymorphisms and deletion of the GSMT1 gene in a Peruvian mestizo population. Farmatsiia (Sofia) 2021, 68(4), 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Valverde, L.; Levano, K. S.; Tarazona, D. D.; Vasquez-Dominguez, A.; Toledo-Nauto, A.; Capristano, S.; Sanchez, C.; Tarazona-Santos, E.; Ugarte-Gil, C.; Guio, H. GSTT1/GSTM1 Genotype and Anti-Tuberculosis Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Peruvian Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(19), 11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabana, G. S.; Lewis, C. M., Jr.; Tito, R. Y.; Covey, R. A.; Cáceres, A. M.; Cruz, A. F. D. L.; Durand, D.; Housman, G.; Hulsey, B. I.; Iannacone, G. C.; López, P. W.; Martínez, R.; Medina, Á.; Dávila, O. O.; Pinto, K. P. O.; Santillán, S. I. P.; Domínguez, P. R.; Rubel, M.; Smith, H. F.; Smith, S. E.; Massa, V. R. de C.; Lizárraga, B.; Stone, A. C. Population Genetic Structure of Traditional Populations in the Peruvian Central Andes and Implications for South American Population History. Hum. Biol. 2014, 86(3), 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, V.; Alvim, I.; Mendes, M.; Silva-Carvalho, C.; Soares-Souza, G. B.; Leal, T. P.; Furlan, V.; Scliar, M. O.; Zamudio, R.; Zolini, C.; Araújo, G. S.; Luizon, M. R.; Padilla, C.; Cáceres, O.; Levano, K.; Sánchez, C.; Trujillo, O.; Flores-Villanueva, P. O.; Dean, M.; Fuselli, S.; Machado, M.; Romero, P. E.; Tassi, F.; Yeager, M.; O’Connor, T. D.; Gilman, R. H.; Tarazona-Santos, E.; Guio, H. The Genetic Structure and Adaptation of Andean Highlanders and Amazonians Are Influenced by the Interplay between Geography and Culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117(51), 32557–32565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad-Hussein, A.; Shahy, E. M.; Ibrahim, K. S.; Mahdy-Abdallah, H.; Taha, M. M.; Abdel-Shafy, E. A.; Shaban, E. E. Influence of GSTM1, T1 Genes Polymorphisms on Oxidative Stress and Liver Enzymes in Rural and Urban Pesticides-Exposed Workers. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77(10), 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, V.; Caceres, O.; Sanchez, C.; Padilla, C.; Veliz-Otani, D.; Mendes, M.; Silva-Carvalho, C.; Alvim, I.; Maron, B. A.; Gouveia, M. H.; Peruvian Genome Project Consortium; Tarazona-Santos, E.; Guio, H.; O’Connor, T. D. Peruvian Population Genomics: Unraveling the Genetic Landscape and Admixture Dynamics of Urban Populations. bioRxivorg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weich, N.; Roisman, A.; Cerliani, B.; Aráoz, H. V.; Chertkoff, L.; Richard, S. M.; Slavutsky, I.; Larripa, I. B.; Fundia, A. F. Gene Polymorphism Profiles of Drug-Metabolising Enzymes GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 in an Argentinian Population. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2017, 44(4), 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón Cuenca, J.; Tirado, N.; Barral, J.; Ali, I.; Levi, M.; Stenius, U.; Berglund, M.; Dreij, K. Increased Levels of Genotoxic Damage in a Bolivian Agricultural Population Exposed to Mixtures of Pesticides. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695(133942), 133942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattás, G. J. F.; Kato, M.; Soares-Vieira, J. A.; Siraque, M. S.; Kohler, P.; Gomes, L.; Rego, M. A. V.; Bydlowski, S. P. Ethnicity and Glutathione S-Transferase (GSTM1/GSTT1) Polymorphisms in a Brazilian Population. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2004, 37(4), 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, C. A.; Quiñones, L. A.; Catalán, J.; Cáceres, D. D.; Fullá, J. A.; Roco, A. M. Impact of CYP1A1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 Polymorphisms in Overall and Specific Prostate Cancer Survival. Urol. Oncol. 2014, 32(3), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Molina, E.; Santacoloma, M.; Arango, L.; Camargo, M. Gastric Cancer and Detoxifying Genes in a Colombian Population. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 2010, 25(3), 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- de Mendonça, E.; Salazar Alcalá, E.; Fernández-Mestre, M. Papel de Las Variantes GSTM1, GSTT1 y MnSOD En El Desarrollo de Enfermedad de Alzheimer de Aparición Tardía y Su Relación Con El Alelo 4 de APOE. Neurologia 2016, 31(8), 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Cano, L. E.; Córdova, E. J.; Orozco, L.; Martínez-Hernández, A.; Cid, M.; Leal-Berumen, I.; Licón-Trillo, A.; Lechuga-Valles, R.; González-Ponce, M.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Moreno-Brito, V. GSTT1 and GSTM1 Null Variants in Mestizo and Amerindian Populations from Northwestern Mexico and a Literature Review. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2017, 40(4), 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Morales, R.; Castro-Hernández, C.; Gonsebatt, M. E.; Rubio, J. Polymorphism of CYP1A1*2C, GSTM1*0, and GSTT1*0 in a Mexican Mestizo Population: A Similitude Analysis. Hum. Biol. 2008, 80(4), 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).