1. Introduction

For decades, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been the dominant indicator used to measure economic performance and social progress. Yet, the limitations of GDP as a proxy for development are now widely acknowledged. GDP captures the monetary value of production but remains blind to fundamental aspects of social well-being, environmental quality, institutional strength, and equity. Regions can grow while becoming more unequal, environmentally degraded, socially fragmented, or unsafe. This disconnect has become increasingly evident in advanced economies, where economic growth no longer guarantees improvements in quality of life, social cohesion, or sustainability.

In light of these constraints, new development frameworks have been developed. Among these, ISTAT’s Italian Benessere Equo e Sostenibile (BES) framework is one of the most innovative methods developed to measure well-being in its multidimensional form. BES takes into account factors like health, education, security, work, income, social relations, institutions, environment, innovation, and public services to offer an inclusive vision of true living conditions. However, despite its high conceptual complexity, its empirical implementation within economic analysis is relatively limited. One of the core questions that are yet to be fully answered is whether or not the different aspects of well-being as measured through BES are mere reflections of social realities or whether they are capable of shaping economic performance. This thesis tackles this question by focusing on the relationship between BES factors and GDP in Italy. Contrary to traditional analysis that focuses on GDP and well-being as two distinct or rival aspects, this thesis takes a structural approach to understand well-being as an input within production. Thus, its core question is as follows:

To what extent are the multidimensional aspects of well-being, as measured through its different aspects of Benessere, Equità, and Sostenibilità, able to influence economic performance in Italy, and to what extent can these relationships differ across territories?

This is an extremely pertinent question within an Italian setting that is marked by high levels of disparities in different aspects like income, health, security, public services, infrastructure, education, and environmental quality. Northern territories and self-governing regions are generally known to have high levels of GDP, as well as high levels of quality in terms of infrastructure and institutions, whereas southern territories are known to experience problems in terms of infrastructure, high crime rates, social capital, and environmental vulnerability. It is therefore necessary to establish whether or not these are mere co-variables to GDP or whether they are structurally responsible for it in order to make informed decisions about development.

The literature on regional growth and development can be broadly classified into three strands. The first strand deals with traditional factors such as capital accumulation, human capital, innovation, and agglomeration. The second strand deals with social and institutional factors such as crime, trust, governance, and inequality. The third strand deals with environment and climate change risks. While each of these strands provides important and useful results, they examine these aspects in a disconnected manner. What has been largely missing in the literature is an integrated framework combining these aspects of economic performance, social welfare, equity, and sustainability in a unified empirical model. Furthermore, few studies in the literature use BES per se, despite its richness and relevance in the Italian context. Most empirical studies based on BES use it in a descriptive manner, in terms of rankings and composite indices rather than their relationship with economic performance in a causative and structural manner. In addition, the traditional literature in econometrics has largely followed a linear or log-linear model, implying strong functional form restrictions and a lack of suitability in capturing nonlinear and threshold-based relationships and regional heterogeneities in regional systems. For example, the relationship between the economy and crime, public transportation, health, and environment awareness can be nonlinear in the sense that it depends on whether a region lies on the left or right side of certain development thresholds, and these aspects remain obscured in traditional regression analysis. This paper fills these research gaps in three basic ways. Firstly, the indicators of BES are conceived not as outcomes but as drivers of GDP, with well-being treated as an input into the production of regional income. The security, health, education, environmental, and social inclusion aspects of well-being are conceived here as productive assets that influence investment, labor, innovation, and competitiveness. Secondly, a new methodological approach is developed that brings together panel econometrics, regression analysis using machine learning, and clustering in a unified framework that allows the analysis to explore causal linkages in time and complex geographical patterns in a unified way. Finally, this research will carefully distinguish between the three-pillar structure of BES, Benessere (B), Equità (E), and Sostenibilità (S), in contrast to using a single indicator that summarizes all three, so that we can determine which aspects of well-being count the most for GDP. These regional economies are complex adaptive systems that involve feedback, complementarities, geographical spillovers, and non-linear dynamics. For instance, raising public transport by a marginal amount would have little effect in an unconnected rural region but would have a dramatic effect in an urban region plagued by congestion; and awareness of climate change would trigger innovation only in regions that have some research capacity already. Linear models cannot handle such dynamics. This research, therefore, uses machine learning models suited to each BES dimension. In Benessere, GDP is modeled using K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) to reflect similarities and differences in how health, safety, and services matter to different regions' income. In Equità, GDP is modeled using Boosting, which is good at detecting inequality thresholds and non-linear effects of inequality. In Sostenibilità, again in GDP, Boosting is used to model non-linear dynamics of environmental risk, awareness of climate change, and innovation. This is an original contribution since instead of trying to find “best” models, it recognizes that different socio-economic systems have different data-generating processes. But in addition to this, the analysis applies clustering to identify regional development paths. For Benessere and Equità, Hierarchical Clustering is used, and regions with similar values of GDP, health, safety, inclusion, and social capital are clustered. For Sostenibilità, regions are clustered using the Random Forest algorithm, and the complex relationship between environmental quality, innovation, and infrastructure is captured. The analysis identifies regions on virtuous paths, where economic, innovation, and sustainability outcomes feed each other, and others on paths of cumulative disadvantage, where low GDP, poor public services, and social vulnerability trap each other. The originality of this work consists in its comprehensive concept of development. Instead of focusing on whether there is a relationship between GDP and well-being, or on whether there is a connection between them, this work asks whether well-being generates GDP. Moreover, while other studies rely on a single statistical tool, this work relies on a variety of machine learning and clustering techniques, each one chosen according to the specific characteristics of the dimension of the BES being analyzed. In this manner, three main results are obtained. Firstly, there is empirical evidence that well-being, equity, and sustainability are not a luxury that only rich areas enjoy but are actually structural factors influencing economic performance. Secondly, there is evidence that there are multiple development regimes within the Italian regional system, contrary to a simple North-South dichotomy. Thirdly, there is evidence that machine learning techniques are not only predictive tools but a strong analytical instrument for economics, able to discover hidden patterns within socio-economic systems. By including GDP within the BES paradigm, this work presents a new vision on growth: growth not only as an autonomous economic process but as a process that naturally derives from a set of social, institutional, and environmental systems working well—or failing to work well together.

2. Literature Review

The current literature agrees on a key assertion: economic growth must be studied in relation to social welfare, institutions, and sustainability. This view is in line with the BES (BES) model and the sustainability-driven economic growth model presented in this study. Ahammed et al. (2025) have found that blue economy factors such as ocean resources, protection of the environment, and coastal innovations contribute substantially to economic growth in China, thus verifying the productive role of natural capital in relation to proper engagement with institutions and innovations. The same results are found in the studies of Berberoglu et al. (2024) and Chengliang et al. (2025), which found that environmental policies and sustainable use of resources are facilitators rather than inhibitors of economic performance. Additionally, Du et al. (2024) have found energy security to have an effect on economic growth, thus emphasizing the importance of infrastructure reliability in achieving sustainable economic growth. The importance of human welfare, as an input in economic production, is also adequately argued. Anauati et al. (2025) measure economic costs related to poor sleep habits, while Barbier and Mensah (2025) prove that environmental risks to health have harmful impacts on economic development and human welfare. The complex linkages between health, environment, and economic development are also clarified in Dar et al. (2025), which uses machine learning to model non-linear dynamics in these linkages. Akinlo and Okunlola (2025) also highlight the importance of institutions in these linkages, arguing that economic freedom improves human welfare but in environments that are high in political risk, and that it is necessary to have state capacity to measure human welfare properly. Grashof (2025), and also Crozet et al. (2024), also argue that to measure human welfare and regional economic performance, one must move beyond income to structural-compositional analysis. Moreover, the views from the historical school and the degrowth school offered by Buscemi (2025) and Chakori et al. (2026), respectively, refute the assumption that economic growth is a necessary condition for prosperity and suggest that economic stability can be attained through redistribution, resilience, and social cohesion. Gylfason and Nganou (2025) illustrate that the development of Mongolia can be fueled by the use of mineral resources in the development of human and social capital. However, the findings in Haroon and Hayyat (2025) suggest that the economic development in regions caused by mining is subject to environmental strain. The role of the environmental channel is evident in the fact that the primary role of critical minerals in the achievement of green growth is in the sustainable energy transition according to the findings in Hwang et al. (2024). Also, the findings in Insaidoo et al. (2025) show a significant decrease in the level of production in Africa caused by extreme weather conditions.

Lastly, the views in Infante-Amate et al. (2024) support the fact that the decoupling of well-being from emissions in the context of economic growth is a long-term reality. Le et al. (2024) suggest that the energy intensity of well-being increases in the absence of technological and institutional changes.

Well-being and life satisfaction positively affect economic performance, supported by the research of Hussien et al. (2025) and Iuga et al. (2025) in terms of health spending, which is a result of environmental quality and income, as found in the study of Islam and Baida (2025). These researches emphasize the need for social investment, which is not a cost but a driver for economic growth. Institutions and finances play a similarly crucial role in achieving sustainable growth, with Kunawotor et al. (2025) relating the role of the state’s size and quality of institutions in the performance of welfare in Africa and Martynenko et al. (2025) proving that fiscal decentralization increases sustainability in a region. The importance of digitalization in European economic growth is highlighted in the research of Lobonț et al. (2025) and Mashaqbeh (2025) in terms of the stabilizing effects of remittances in Jordan. In a collective manner, these researches reaffirm the need for alternative and post-growth theories that relate development, equity, and sustainability, supported by Lauer et al. (2025) and Levy (2025) in their research. The causal relationship between culture and economic and social performance in Europe is examined in the research of Mažeikaitė (2025) and indicates that values, norms, and trust influence economic performance in a productive manner, in accordance with the BES view that social capital and civic engagement play a decisive role in economic performance in a region. Territorial and geographical determinants also influence economic performance. According to Mikheeva (2025), geo-strategic location affects regional development in Russia, while Tan et al. (2025) indicate that tourism is a factor in human development and economic income in the ASEAN countries. Public engagement affects the economic performance of the region (Tleuberdinova et al., 2025), indicating that development is contingent upon public engagement in economic activities. Well-being and demographic determinants are also of great significance; hence, Mohamed et al. (2025) indicate a positive feedback loop between life expectancy and per capita GDP in Somalia, while Munawaroh et al. (2025) indicate that aging populations have significant macroeconomic impacts in Indonesia. These findings are supported by the views of Warner et al. (2025) who propose that an aging population requires a paradigm shift in the theory of growth economics, labor economics, and regional policy; this marks the beginning of the BES transition from quantity to quality of life. Distributional and multidimensional methods extend this paradigm. Natanael (2025) finds that commodity diversification improves equality and human development, and Okogun & Hiwatari (2024) define poverty as a multidimensional concept, especially in terms of women and children. Rijpma et al. (2025) find historical support for the superiority of composite development metrics in long-run development analysis compared with GDP. Sustainability and technology development are integral to these dynamics. Tian et al. (2024) find that social trade-offs accompany private mining sector investments in rural communities, and Tiwari et al. (2024) find mutual benefits of fintech and green finance. Utouh & Kitole (2025) emphasize the large social opportunity costs of massive infrastructure development. Wu et al. (2025) find that energy corporations' entry into countries with low environmental performance faces challenges in terms of legitimacy, hindering long-run development, and illustrate how institutional and environmental vulnerabilities impede economic performance. This confirms the BES hypothesis about the importance of environmental and institutional structure in economic performance, rather than considering them as externalities. Labor dynamics in the labor market and social stability are also important in energy transitions. Xolmurotov et al. (2025) demonstrate that an increase in the use of renewable energy sources decreases unemployment in Uzbekistan, implying that a green transition ensures inclusive growth. Zéman et al. (2025) further widen this focus to be global in coverage and demonstrate that material consumption behavior and energy structure are important in determining various dimensions of social and economic welfare outcomes. The human factor also plays an important role in transitions in any economy. Zhou et al. (2025) demonstrate that human capital and happiness are important in determining migration and economic growth in China and that labor mobility and productivity are subject to social and educational factors. Life expectancy and environmental sustainability are also important in BRICS countries in achieving inclusive growth in transitions, as asserted by Yeboah et al. in 2024, who further argue that the quality of growth is more important than the quantity of growth in transitions. See

Table 1.

3. Methodology

The link between economic growth and well-being is, in itself, complex, multifaceted, and regionally specific. Social inclusion, environmental sustainability, innovation, public service, and trust in institutions do not affect GDP in a straightforward or cumulative fashion, but rather through complex interlinkages, feedback effects, thresholds, and cumulative processes. For this reason, this research employs a comprehensive research methodology that brings together panel econometrics, regression analysis using machine learning, and clustering analysis, which can support both causal analysis and the detection of underlying structural patterns. Specifically, panel econometric analysis will be used in this research for initial analysis, aiming to detect the typical dynamic link between GDP and the set of BES indicators. The need for this initial analysis stems from the fact that region-specific features, such as geographical, developmental, and institutional characteristics, tend to be constant and not easily observable, but still tend to significantly influence economic performance. The fixed effects model and the random effects model will be estimated in this research in order to account for these region-specific features and filter out the influence of changes in well-being for each region. The underlying question this research seeks to address is: "Can a better health, security, environmental, and social situation in a region be translated into increased economic growth, measured through higher GDP values, in the long run?" However, linear panel regression models imply very strong form constraints on the function and assume linearity in the effects of, for example, crime reduction, the promotion of renewable energy sources, and education on the dependent variable for all regions and levels of development. In reality, this linearity and homogeneity of effect do not exist in nonlinear and threshold phenomena in the regions’ systems. Hence, panel regression models are extended with machine learning algorithms. Machine learning algorithms are particularly well-suited to the detection of complex nonlinear interdependencies and relations common to socio-economic systems like the regions’ systems. In contrast to linear panel regression models that imply a strict form on the function to estimate and assume linearity in the effects of the variables on the dependent variable for all regions and levels of development, machine learning algorithms do not imply any structure on the function and instead allow the structure to emerge from the data itself on the interdependencies between the various dimensions of well-being and the GDP variable. The choice of the machine learning algorithms for the various dimensions of well-being depends on the algorithms’ forecast accuracy for the GDP variable for the regions’ systems. In the Benessere (B) dimension of well-being, the K-Nearest Neighbors machine learning algorithm will be applied due to its sensitivity to local similarities among the regions and the assumption that regions with similar social and health characteristics follow the same growth path for the GDP variable. In the Equità (E) and the Sostenibilità (S) well-being dimension of the regions’ systems, the This is an essential step, as well-being does not have a smooth and proportional impact on GDP, as, for instance, small increases in social inclusion might have a limited effect in developed areas but a strong effect in other areas. Machine learning makes it easier to detect these relationships. Regression analysis explains how well-being influences GDP, and the other part of the analysis, clustering, explains how regions are grouped in specific regimes of development. This is an essential part of the analysis since Italy has not one but many models of growth. Hierarchical clustering is employed on the Benessere and Equità dimensions since these variables are associated with deeply embedded social and institutional settings that develop in a very gradual and nested territorial way. However, for the Sostenibilità dimension, Random Forest Clustering is employed since the nonlinear relationships between environmental and innovation variables are very complex and result in specific sustainability and growth patterns, not easily detectable through other methods, like distance metrics. By combining panel econometrics, machine learning, and clustering, the analysis can go from simple correlations to a deeper interpretation of the results. Panel models detect causality in a temporal framework, while machine learning and clustering detect nonlinear and heterogeneous relationships and the presence of territorial regimes, respectively. This comprehensive approach is therefore crucial for comprehending how the BES dimensions not only measure social outcomes but are, in essence, prime drivers of Italian regional GDP performance.

Figure 1.

The Engine of Growth: How Well-Being, Equity, and Sustainability Drive Italy’s Regional Economy. This figure summarizes the BES-based analytical framework, showing how well-being, equity, and sustainability jointly shape regional GDP in Italy. Machine-learning and clustering results highlight nonlinear interactions and distinct territorial development regimes driven by mobility, social inclusion, innovation, and environmental quality.

Figure 1.

The Engine of Growth: How Well-Being, Equity, and Sustainability Drive Italy’s Regional Economy. This figure summarizes the BES-based analytical framework, showing how well-being, equity, and sustainability jointly shape regional GDP in Italy. Machine-learning and clustering results highlight nonlinear interactions and distinct territorial development regimes driven by mobility, social inclusion, innovation, and environmental quality.

4. From Quality of Life to Economic Output: The Benessere–GDP Nexus

This research focuses on the role of the B-Benessere (Well-being) component in the ISTAT-BES approach in influencing the GDP in Italy from 2012 to 2023. While recognizing the fact that economic development is inextricably linked with the determinants of well-being, the research considers personal security, the availability of basic services and health care as fundamental drivers of the quality of life that in turn affect aggregate economic performance. For a territory with a high degree of heterogeneity in Italy, the differences in the regions' well-being drivers are the source of disparities in economic performance. The research uses a panel data approach in 21 regions in Italy and defines GDP as a function of the crime rate, the availability of public transport services, and the density of the number of medical doctors. The primary research question is whether improvements in the regions' well-being are correlated with increases in the regions' economic output. With the inclusion of the GDP-Benessere variables in the research model, the research defines the drivers of the well-being in terms of the social outcomes of economic development. The research proposes an integrated approach to economic development in line with the BES approach. According to the research approach, economic performance and the quality of life are intertwined in a way that is not contradictory but mutually reinforcing. See

Table 2.

Specifically we have estimated the following equation:

where i=21 and t=2012-2023.

The panel dataset estimates how regional GDP correlates with the first four main factors of well-being identified in the ISTAT-BES method: security, measured by rates of home burglary and robbery; access to collective services, measured by access to public transport; and healthcare, measured by the density of medical doctors. In a BES perspective, GDP is conceptualized not only as an end but also as an economic outcome that corresponds to the quality of social, institutional, and environmental factors. In this respect, this study tries to assess whether there is a structurally significant link between well-being and economic performance for Italian regions from 2012 to 2023. The Hausman test confirms that there is no correlation between unobserved regional variables and explanatory variables, suggesting that a fixed effect estimation is appropriate. This is not surprising, given that crime rates, healthcare systems, and transport networks are all affected by regional factors such as governance quality, path dependence, and social capital in Italy. As a consequence, fixed effect estimation is appropriate since it allows identification of how variations in well-being affect regional economic performance. The test on group intercepts additionally confirms that there is significant inter-regional variation. This has important methodological implications, especially from a BES perspective. In fact, well-being is a territorial concept since there are significant inter-regional variations not only with respect to income but also with respect to institutions, security, healthcare systems, and access to services. Omitting this structural characteristic would produce biased estimates on how GDP relates to BES indicators. The results show a significant, large, and negative impact of both crime variables, the burglary rate and robbery rate, on the regional GDP. This result indicates that there is a systematic association between high levels of crime and poor economic performance. In the BES framework, security is shown to be both a social asset and a productive input, since it increases transaction costs, deters investments, reduces tourist inflows, erodes trust, and leads to expenditures on defensive activities. The result also indicates that violent or visible crimes have more significant effects, considering the effects of robbery, which directly influence the perception of safety required in economic activities. The coefficient of public transport supply is positively significant, indicating that areas that have more developed and efficient public transport networks are likely to have higher GDP. This is consistent with the BES model, as it recognizes the significance of mobility in guaranteeing equal accessibility to opportunities and improving productivity in urban areas. Efficient public transport systems address issues of inequality and link workers to jobs, as well as address congestion and environmental issues. This makes transport infrastructure expenditure a crucial factor in economic development rather than just public expenditure. The density of medical doctors is found to have a significant positive influence on GDP. In fact, it is one of the most significant variables in the model. The importance of health in the production function is evident in the fact that regions with access to good health care have healthier workers, a reduced number of absent working days, a stable population, and attractiveness for households and enterprises. According to the BES approach, health is both a product and a determinant of development. The fixed effect model also proves to have high levels of explanation. The within R-squared value indicates that about half of the variance in GDP over time in each region can be explained by crime, healthcare, and transport. This indicates that economic growth in Italian regions is affected not only by macro-level factors but also by the dynamics of well-being. Tests for heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-section dependency are confirmed in both models, which is to be expected in panel data that is subject to common shocks (such as financial crises or pandemics like COVID-19), as well as high interregional economic interdependencies. However, instead of being an issue, these are also characteristics that are representative of the Italian regional system. Notably, in both models, the coefficients are also strongly significant despite these characteristics, which again strengthens the robustness of the finding. In conclusion, it is clear that in Italy, GDP is systematically and strongly connected to well-being. Economic performance is improved when crime is reduced, healthcare is improved, and transport is expanded. Conversely, reduction in these areas is also associated with improved economic performance. This finding strongly supports the ISTAT-BES paradigm, which argues that economic development and social development are interrelated. Improving economic performance through collective actions seems to also improve well-being, which in turn improves regional GDP.

Table 3.

4.1. Modeling the Benessere–GDP Nexus with Machine Learning: Evidence from KNN

The comparative analysis of the seven models, based on the use of normalized performance metrics, shows that K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) represents the best model in terms of explanation and prediction of regional GDP based on BES indicators. First, KNN has the highest value of R² (1.000), implying that it explains the largest possible variation in GDP among the competing models. In regional economic models, GDP depends on complex, nonlinear, and regionally varying processes; a model capable of explaining a larger variation in GDP has a higher chance of representing the underlying economic reality. Although Random Forest has a high value of R², KNN moderately outperforms it with smaller prediction errors. Second, KNN has a stable performance on all error metrics. With a normalized value of MSE (0.994), RMSE (0.679), and MAE (0.773), KNN’s prediction values are both small and stable. Stability in performance is important since models with high values of R² and low values of error metrics might describe the data structure well but with large prediction errors. KNN avoids this weakness since it provides high values of explanation power and low values of prediction error. In addition, its MAPE (0.786) value shows low percentage errors, implying a high level of accuracy in GDP prediction in both absolute and percentage terms. Third, in relation to other parametric models such as Linear and Regularized Linear Regression models, KNN has a higher capacity to describe the nonlinear relationship between BES dimensions and GDP in regions. In regional economies, performance depends on threshold effects, clustering, and local interactions (coexistence of high GDP, high services, and high urban density). KNN has a higher capacity to describe these effects since it depends on local information rather than a global functional relationship. Finally, in relation to other tree-based models such as Decision Trees and Random Forest models, KNN has a higher balance in performance. While Decision Trees provide high performance in MAPE but low performance in R² values, the latter provides high performance in R² values but with high prediction errors. See

Table 4.

The feature-importance results obtained from the KNN model provide a clear and robust picture of how the B–Benessere (well-being) component of the BES framework is structurally linked to regional GDP in the Italian regions and in the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano. In KNN, feature importance is measured through mean dropout loss, which captures how much the predictive accuracy of the model deteriorates when a given variable is removed. Because KNN is a non-parametric and locally adaptive algorithm, these importance scores reflect how strongly each BES dimension contributes to explaining the observed spatial and socioeconomic patterns in GDP. The dominant role of Public Transport Supply (PTS), with a mean dropout loss of about 8.2406E+04, indicates that mobility infrastructure is the single most important well-being driver of regional GDP in the KNN model. This result is particularly meaningful in a KNN framework because it implies that regions with similar levels of public transport provision also cluster together in terms of economic performance. Public Transport Satisfaction (PTS2) ranks second, showing that the quality of mobility services is almost as important as their quantity for shaping local economic outcomes. Security and health emerge as the next fundamental pillars. Home Burglary Rate (HBR) has a very large dropout loss, indicating that safety is a key dimension of economic proximity in the data: regions with similar crime levels tend to display similar GDP patterns. Medical Doctors Density (MDD), Disability-Free Life Expectancy (DFLE) and Healthy Life Expectancy at Birth (HLEB) also rank highly, confirming that human capital in its health dimension is central to regional economic productivity. In a KNN setting, this means that regions with comparable health conditions are grouped together in terms of economic performance. Finally, digitalization and social participation complete the picture. Regular Internet Users (RIU) and Household Digital Access (HDA) show that digital inclusion is a crucial economic driver, while Out-of-Home Cultural Participation (OHCP) and Civic and Political Participation (CPP) highlight the importance of social capital. Overall, the KNN-based analysis shows that GDP in Italy is closely tied to the multidimensional structure of well-being captured by the BES, with mobility, health, security and social connectivity acting as the main channels through which regional prosperity is shaped. See

Table 5.

These outcomes provide a nuanced and policy-informed explanation of the impact of the B-Benessere component of the BES approach on the simulated GDP for the Italian regions and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano using a KNN algorithm. Under this approach, the “Base” of some 86,441 represents the baseline GDP simulated without BES data in the model, while the final “Predicted” GDP for each case is calculated by modifying the baseline using the contribution of the individual well-being indicators. That all five cases show predicted values well below the baseline indicates the systematically depressing impact of structural well-being deficits on economic performance. Across all five cases, the most strongly negative impacts are found for Public Transport Supply (PTS) and Home Burglary Rate (HBR). By itself, PTS depresses predicted GDP values by between -17,000 and -33,000 units, indicating that a lack of mobility infrastructure is a strong drag on economic potential. This finding acquires particular significance in the context of a KNN model, since it indicates that a lack of adequate mobility infrastructure groups together in a systematic way and is associated with systematically lower GDP outcomes. Similarly, a high level of home burglaries has a large and negative impact, reflecting the economic costs of insecurity in the form of lower investment, tourism, and trust. Health and human capital factors are also of central concern. Healthy Life Expectancy at Birth (HLEB) and Disability-Free Life Expectancy (DFLE) have large and sometimes offsetting impacts; in some cases, the latter has a positive impact, suggesting that a healthy population can offset other weaknesses in economic performance, while in others a lack of good health has a strongly depressing impact on GDP. Digital inclusion as measured by the number of Regular Internet Users (RIU) and Household Digital Access (HDA) has mixed but often large impacts, supporting the idea that connectivity is a critical determinant of economic inclusion and productivity. Civic and cultural participation as measured by Overall Health Care Performance (OHCP) and Civic Participation Performance (CPP) have important impacts that are sometimes positive and sometimes negative, reflecting the complex ways in which social capital interacts with economic structure in local contexts. Finally, Medical Doctors Density (MDD) and Public Transport Satisfaction (PTS2) qualify the impact of the other factors. According to the analysis carried out using the KNN-based BES, the Italian GDP is not influenced by a single dimension of well-being but is instead influenced by a combination of the dimensions of mobility, security, health, digital access, and social participation, and this is increased through geographical closeness. See

Table 6.

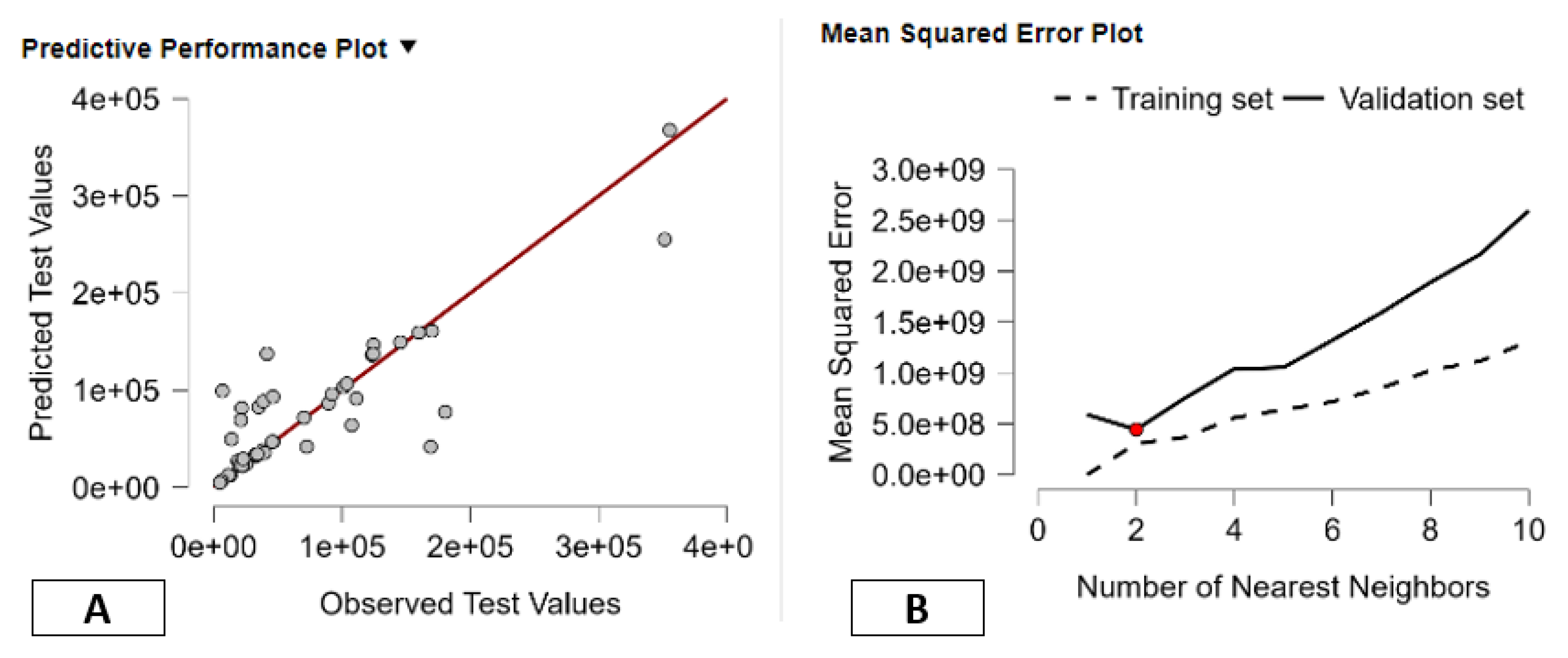

The figure provides a very informative graphical assessment of the performance of a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression algorithm used in the prediction of the GDP in the Italian regions and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano based on BES well-being measures. Panel A of the figure provides the performance plot where the observed values are shown on the horizontal axis and the predicted values are shown on the vertical axis. The red diagonal line represents perfect predictions. All the observations are very close to the diagonal line, especially in the low to medium GDP regions. This is an indication that the KNN algorithm is very effective in identifying the underlying data structure. However, the observations are more spread out in the higher GDP regions. This can be attributed to the algorithm's tendency to slightly underestimate or overestimate the income of the richer regions due to the lack of close neighbors among the top observations. This is typical of the KNN algorithm that uses local averaging. If the top observations have few close neighbors, the predictions are not as accurate. In panel B, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) is plotted for both the training data (dashed line) and the validation data (solid line) for a given number of nearest neighbors (k). The red circle indicates the optimal value for k, which is about k=2. At this point, the error on the validation data is minimized, which means a good trade-off is achieved between bias and variance. When k is small, there is a lot of flexibility in the model, which can be prone to overfitting; for larger values of k, the model is smoothed and can be prone to underfitting, which is reflected in the increasing error on the validation data. The growing difference in error between the training and validation data for larger values of k further illustrates how too much averaging over regions with large differences leads to a deterioration in predictive performance. Taken together, these two panels show that the KNN algorithm is effective in identifying the nonlinear and regionally heterogeneous relationship between GDP and the BES B-Benessere indices. This result for optimal k supports the idea that regional GDP is best explained by very local patterns of similarity, and that well-being and economic performance in Italy are heavily influenced by regionally and socio-economically local groups of regions.

Figure 2.

KNN Predictive Performance and Model Selection for GDP Based on BES Well-Being Indicators. Note: Panel A shows observed versus predicted GDP for the KNN model, while Panel B reports training and validation MSE across k values. The optimal k minimizes validation error, indicating that GDP is best explained by local, nonlinear relationships between well-being and economic performance.

Figure 2.

KNN Predictive Performance and Model Selection for GDP Based on BES Well-Being Indicators. Note: Panel A shows observed versus predicted GDP for the KNN model, while Panel B reports training and validation MSE across k values. The optimal k minimizes validation error, indicating that GDP is best explained by local, nonlinear relationships between well-being and economic performance.

4.2. Territorial Patterns of Benessere and Economic Performance in Italy

The normalized data set compares six different clustering methods using seven different measures that focus on different aspects of clustering quality: compactness (Maximum diameter), separation (Minimum separation), internal consistency (Pearson’s γ and Dunn’s index), informational homogeneity (Entropy), inter-cluster variance (Calinski & Harabasz), and equality in cluster size (HHI). Since each measure is scaled to ensure that larger values are associated with improved performance, it is possible to make meaningful comparisons. On this basis, Hierarchical Clustering is shown to be the best-performing method. It scores highest (1.000) on four major structural criteria: Maximum diameter, Minimum separation, Pearson’s γ, and Dunn’s index. This suggests that it provides compact, well-separated, and internally consistent clusters, which is an ideal combination for modeling complex socio-economic relationships like that between GDP and BES well-being domains. Hierarchical Clustering also scores highest on HHI (1.000), which suggests that it provides an excellent balance between cluster size and that there are no large clusters dominating others. Although it scores highest on Calinski & Harabasz index (1.000), which indicates excellent global separation in terms of variance explained, it also scores poorly on balance (HHI), separation, consistency, and entropy, which are less stable and less informative. Although it scores high on balance (HHI), it also scores poorly on excellence in terms of structural criteria. Density-based clustering is less excellent in terms of entropy, but it scores poorly on compactness and discriminative ability. On balance between geometric quality, structural consistency, and equality in cluster size, Hierarchical Clustering is found to score highest and is therefore considered to be the best method to investigate GDP and well-being in Italian regions and self-governing provinces. See

Table 7.

The outcomes obtained through hierarchical clustering show nine different regional profiles, defined on the basis of GDP and the BES "B-Benessere" factors, reported in standardized units (z-scores). Positive scores show performance above the country average, while negative scores show below-average performance. By jointly considering the table, it is possible to better understand how prosperity and well-being interact and develop in Italy's regions and autonomous provinces. Clusters 3 and 4 are the least developed, showing very low GDP scores of –1.31 and –1.26, respectively, and very low scores for healthy life expectancy (HLEB), disability-free life expectancy (DFLE), civic participation (CPP), and public transport (PTS). These clusters describe regions caught in a low development-low well-being trap, in which economic vulnerability is associated with low health performance, low social capital, and limited infrastructure. Cluster 6, on the other hand, represents the most successful and vibrant society with high GDP of 0.944 and equally outstanding civic engagement of 1.936 CPP, low crime of 1.981 HBR, high medical density of 1.820 MDD, and high public transport satisfaction of 2.335 PTS2. This cluster indicates that it represents advanced areas where economic development and other dimensions of sophistication such as institutions, healthcare, and society reinforce each other in a self-sustaining manner. Cluster 5 also represents similar characteristics but to a slightly lower extent in economic performance with high GDP of 0.411 and equally outstanding performance in public safety of 2.127 HBR, civic engagement of 1.169 CPP, and digital access of 1.446 HDA. In particular, Cluster 9 is interesting because of its combination of a very high DFLE (3.443) and a large supply of public transport (PTS = 3.240) with a strong GDP (0.481). This pattern points to a growth path with a significant contribution to economic success from physical health and mobility infrastructures. Cluster 7 represents a balanced, moderately successful pattern: The GDP is positive (0.666), and all well-being variables are close to zero or slightly positive. Lastly, the patterns shown by clusters 1, 2, and 8 are more heterogeneous. For instance, Cluster 2 shows high GDP (0.552) and density for medical facilities and personnel (1.280), but low digital access (HDA= -1.105) and cultural participation (OHCP= -0.637), indicating that development in the region is unbalanced. Cluster 8, on the other hand, shows high indicators for health and infrastructure development (DFLE= 1.294, PTS= 1.634) and moderate GDP (0.400), indicating that well-being can precede economic performance. In general, from the hierarchical clustering analysis, there is a strong yet diverse correlation between GDP and multidimensional well-being, as some clusters depict virtuous circles of growth and social quality, while others are marked by accumulated disadvantages. See

Table 8.

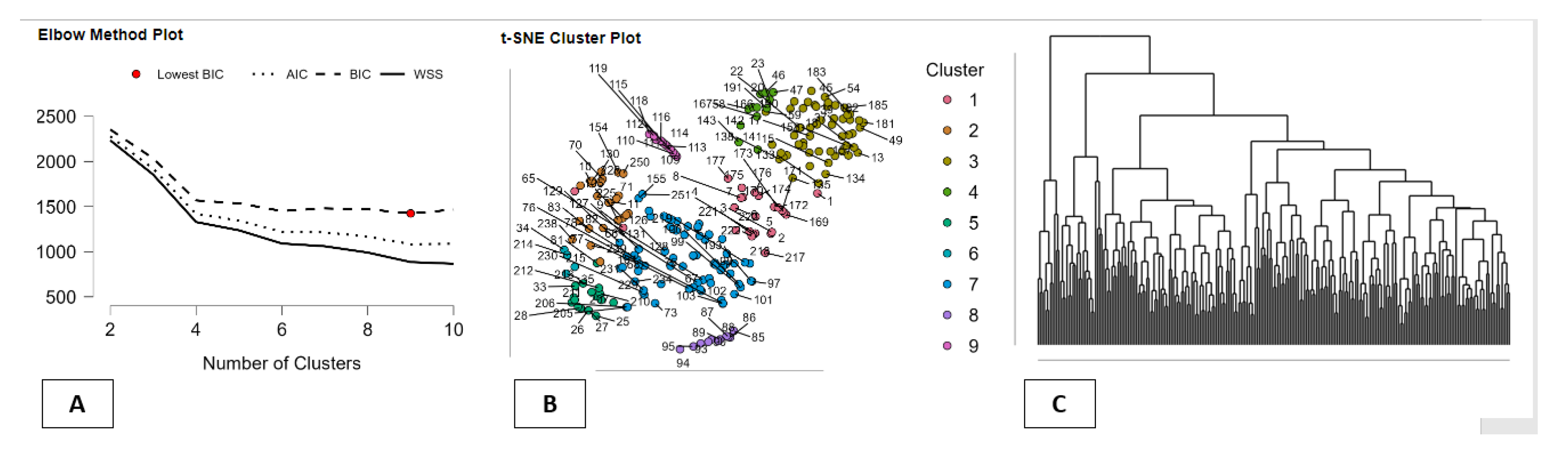

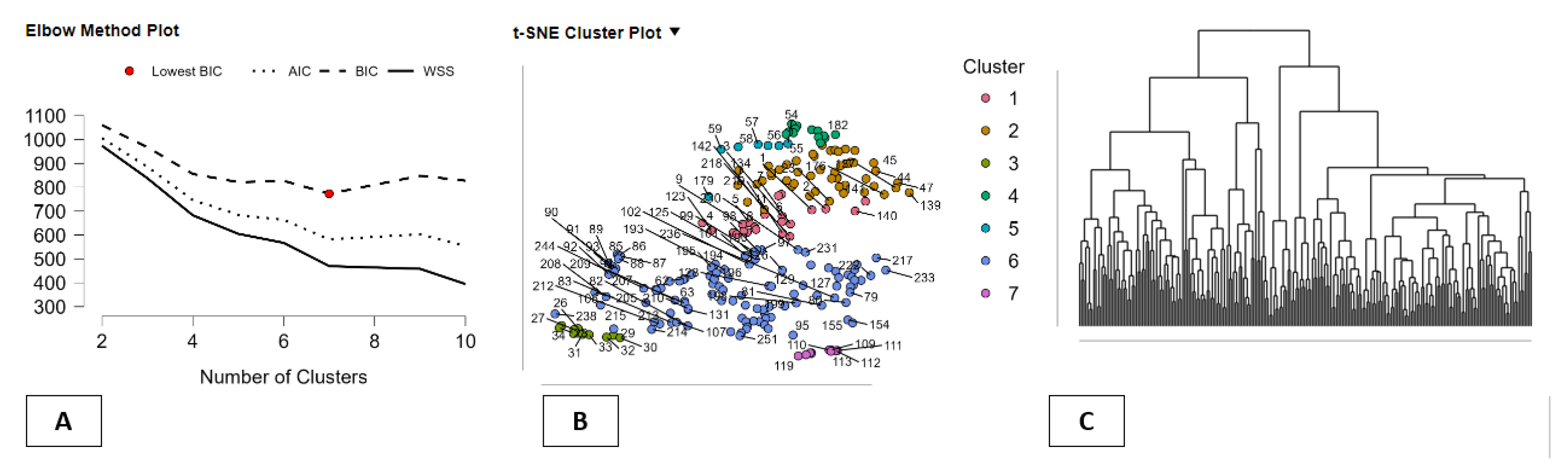

The figure provides a complete and integrated view of the Hierarchical Clustering method applied to Italian regions and autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano in the BES–GDP analysis framework. It combines statistical goodness of fit, geographical visualization, and hierarchical structure in a single tool for interpretation. In Panel A (Elbow Method Plot), three model selection measures are shown: WSS (within-clusters sum of squares), AIC, and BIC. In all cases, the values decrease significantly when the number of clusters increases from 2 through 4-5, and then gradually level off, while the BIC, with its stricter penalty for complexity, has a minimum (marked with a red dot) at nine clusters. This indicates that a nine-cluster solution represents the best compromise between fit and simplicity, thereby justifying the use of nine region-specific profiles. In Panel B (t-SNE Cluster Plot), a non-linear two-dimensional representation of Italian regions using the entire set of BES indicators and GDP values is provided. The nine clusters seem clearly distinguishable and compact, thereby confirming that the hierarchical method has identified truly distinct socioeconomic regimes, not just artificial partitions. Regions that share geographical proximity in terms of quality of life, infrastructure, and economic performance are grouped together, while dissimilar regions are clearly distant. In Panel C (dendrogram view), the full hierarchical structure of the data is shown. The long branches separating the principal groups imply a high level of dissimilarity between the macro-clusters, while shorter branches inside groups imply high levels of homogeneity for regions in the same cluster. The dendrogram shows that Italian regions can be categorized into a small number of strongly differing patterns of development, rather than a continuous gradient. The three panels together clearly demonstrate that hierarchical clustering analysis is a method particularly effective in describing the complex and heterogeneous relationship between GDP and the BES framework for measuring quality of life, and that nine region-specific and economically valid territorial patterns can be identified.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical Clustering of Italian Regions in the BES–GDP Framework. Note: Panel A selects the optimal number of clusters using WSS, AIC, and BIC; Panel B visualizes nine socioeconomic clusters via t-SNE; Panel C shows the hierarchical dendrogram. Together, they confirm the presence of distinct BES–GDP development regimes across Italian regions and autonomous provinces.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical Clustering of Italian Regions in the BES–GDP Framework. Note: Panel A selects the optimal number of clusters using WSS, AIC, and BIC; Panel B visualizes nine socioeconomic clusters via t-SNE; Panel C shows the hierarchical dendrogram. Together, they confirm the presence of distinct BES–GDP development regimes across Italian regions and autonomous provinces.

5. Equity, Inclusion and Regional Growth: Evidence from Italian Panel Data

This section analyzes the relationship between regional GDP and the E-Equo dimension of the ISTAT-BES framework, which captures how inclusive and balanced economic development is across territories and social groups. Using panel data for the 20 Italian regions and the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano over the period 2012–2023, GDP is modeled as a function of youth exclusion from employment and education, disposable income per capita, and difficulties in accessing essential services. The aim is to test whether the equity-related conditions of regional economies are systematically linked to their economic performance, and to assess whether growth in Italy has been accompanied by improvements in social inclusion and access to opportunities. See

Table 9.

Specifically we have estimated the following equation:

where i=21 and t=2012-2023

The estimated panel data model focuses on the association between regional GDP and the three main factors underlying the E-Equo dimension, which refers to the youth exclusion from employment and education (YNEE), the gross disposable income per capita (GDIPC), and the difficulties in accessing basic services (SAD) in the context of the ISTAT BES. The study covers 20 Italian regions, together with the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano, during the period 2012-2023. In the context of the BES, the E-Equo dimension captures the degree of inclusiveness, balance, and ability to offer equal opportunities in the process of economic development, which refers to various levels of society. From an econometric point of view, the Hausman test fails to reject the null hypothesis of consistency for the RE estimator; this means that the unobservable regional effects are not significantly correlated with the regressors. This result is consistent with the idea that, as far as the E-Equo variables are concerned, regional disparities in youth exclusion rates, income levels, and service accessibility are not just the result of fixed regional structures but are themselves changing in a manner sufficiently decoupled from the underlying regional heterogeneity modeled by the panel data structure. At the same time, the strongly significant Breusch-Pagan test confirms the presence of significant unit-specific variances, thereby justifying the use of the panel data approach as an alternative to the pooled regression analysis. Additionally, the very strong rejection of the null hypothesis of equal intercepts further emphasizes the significant heterogeneity among the Italian regions and autonomous provinces. This is consistent with the BES approach that assumes the presence of significant regional variations in equity and inclusion as a result of the underlying institutional differences in the regional labor markets, welfare arrangements, and social cohesion. The panel data approach is therefore capable of capturing these regional variations while emphasizing the regional variations in the dynamics of the equity-related variables as determinants of economic outcomes. The results of the regression show a complex and, in some ways, unexpected picture of the link between equity and growth. The coefficient on disposable income per capita is positive and highly statistically significant, confirming a core hypothesis of the E-Equo dimension: regions with stronger purchasing power are those that have stronger GDP. This link is driven by both demand and supply factors. Higher disposable income leads to stronger demand, and it is a source of investment in education, health, and housing, which, in turn, boosts productivity and growth. Income distribution is thus not only a social byproduct of growth but a cause of economic growth. The variable for youth who are neither in employment, education, nor training (NEET) has a positive and significant coefficient in the regression. At first sight, this appears to contradict standard assumptions, as higher levels of NEET are generally expected to be correlated with lower labor market performance and lower-growth trajectories in the long term. However, in the context of the regional fix and time period considered, this result likely corresponds to cyclical and structural characteristics of regional economies in Italy. In various advanced regions, especially in the Northern part of Italy, it is possible to find high levels of regional GDP together with high levels of NEET because of extended education systems, late entry into the labor market, and family networks that support young individuals in staying out of employment until better opportunities arise in other locations. In this sense, the indicator for NEET could capture aspects of social buffer mechanisms rather than strictly economic marginalization. Additionally, it appears that short-term performance of regional GDP is not constrained by youth exclusion in any significant manner, although there could be potentially adverse consequences for sustainability and social cohesion in the long term. The coefficient on SAD is also positive and significant, suggesting that a greater proportion of the population in a given region with difficulty in accessing basic services is associated with a higher GDP. Like the NEET variable, this finding should not be construed as a sign that exclusion is a driver of economic growth. Rather, it simply represents the fact that the regions with higher GDP have large cities, complex urban systems, and high population density. Consequently, the congestion externality in these regions causes housing costs to increase. As a result, access difficulties are experienced despite the high overall income. The finding that SAD is positively correlated with GDP simply represents the fact that economic growth, especially in regions with large cities, creates obstacles in the form of access difficulties. This finding is entirely in line with the BES definition of equity as a multidimensional concept that is not simply a function of income. The large value of R-squared means that changes over time in income distribution, youth inclusion, and service accessibility account for a large part of the variation in GDP per region, suggesting a close link between changes in equity-related circumstances and regional economic developments. Italy’s economy has experienced a dynamic environment over the last ten years, being affected not only by macroeconomic considerations or foreign demand but also by endogenous social and distribution dynamics affecting aggregate household behavior, labor supply, and regional market characteristics. The diagnostic tests indicate that there are issues of heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence, all of which are a reflection of a complex and highly interlinked system at work in Italy’s regional structure. Italy’s regions face shared shocks (sovereign debt crisis, COVID-19 crisis, national policy changes) and are interlinked via migration, trade, and financial flows. However, the robustness and statistical significance of the coefficients clearly suggest that the correlations in this case are not spurious but rather a result of structural interlinkages between equity and economic performance. In a broad sense, the findings of this analysis offer valuable insights into the E-Equo aspect of the BES model. They clearly confirm that a high level of disposable income is a strong stimulus for economic growth in the region, thereby highlighting once again the pivotal role of income distribution in maintaining economic activity. At the same time, however, the positive correlations between economic growth and both youth exclusion and service access difficulties clearly indicate that economic growth in Italy has regularly occurred in tandem with, and in some cases because of, exclusion and access barriers. The simultaneous presence of high income and exclusion/access barriers clearly supports the relevance of the BES model, which argues that economic development in general cannot and should not be judged exclusively in terms of aggregate economic output. In terms of policy implications, this analysis clearly suggests that a more inclusive labor market and better access to basic services not only constitute a question of social justice but also a crucial element in a new, balanced, and sustainable model of economic development. See

Table 10.

5.1. Social Equity and Growth: Evidence from a Boosting Model

In terms of the normalized metrics, it can be seen that the best overall algorithm is indeed Boosting. The primary reason for this is its overall superior performance on the basic error metrics, namely MSE, RMSE, and MAE/MAD, on which it obtains the highest possible value (1.000) on each of these metrics. In other words, these metrics provide a measure of the average difference between the model’s prediction and the actual value of GDP in terms of the sum of the squares of the differences, the square root of the average of the squares of the differences, and the average absolute value of the differences, respectively. In other words, a high performance on these metrics would imply a model’s superior accuracy and its ability to avoid large deviations (highlighted in MSE/RMSE), in addition to its accuracy in its average prediction value. In addition, it can also be seen from these results that the best model also has the highest value on the normalized R² (1.000), indicating that it has the largest possible explanation of the total variation in GDP among the models, implying a high goodness-of-fit in terms of explained variation in the model’s prediction on GDP among the models under consideration. For a model attempting to model the differences in GDP among regions related to BES well-being indicators, it would be important to ensure a high goodness-of-fit in terms of explained variation in GDP among regions since it would enable a higher level of confidence in its inferences about the relationship between the model’s prediction and the GDP values among regions. On the other hand, it can also be seen from these results that although Random Forest and KNN models also perform well on MSE (scaled) and RMSE, they do not do so well on MAE/MAD and, in particular, on the normalized R² value. In addition, it can also be seen from these results that although the best model on MAPE (1.000), it performs poorly on MAE/MAD and MSE, an aspect that would be important since MAPE would be influenced by small denominators in regions with small GDP values, implying a high level of percentage error in its prediction on GDP among regions with small GDP values. In addition, it can also be seen from these results that the performance of the decision tree and SVM models would be poor on nearly all metrics under consideration. See

Table 11.

These results describe the feature importance pattern of the Boosting Regression model analyzing the correlation between GDP and the E–Equo (E-Equo) part of the BES (Benessere Equo e Sostenibile) system for Italian regions and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano. The method used for feature importance evaluation is permutation importance, where the average dropout loss (measured in RMSE) represents the loss of model performance due to the random permutation of the variable; the highest values represent the most important variables for the explanation of the GDP value. The variable GPO (General Population Outcome) appears to be the most important driver with relative importance 6.05e+05 and the highest value of the average dropout loss of 7.82e+11. This implies that the overall social and population factors represent the most powerful equity-related driver of the GDP of the regions. Those with better general social outcomes systematically correspond to the wealthiest regions, and there appears to be an extremely tight link between equity and economic performance. The second most influential predictor is GDIPC (GDP per capita), with a relative influence measure of 2.24e+05 and a dropout loss measure of 7.53e+11. This not only proves the consistency of the model but also emphasizes that per-capita income is an important explanatory variable in determining overall GDP regardless of equity variables. PRR (Poverty Risk Rate) is expected to play a significant part with a relatively high influence measure of 1.12e+05 and a mean dropout loss measure of 7.43e+11. This not only establishes that poverty has a direct effect on regional economic performance but also establishes that higher poverty rates are associated with lower GDP. YNEE (Young people Not in Education, Employment, or Training), although relatively less influential (5.89e+03; 7.42e+11), still plays its part in explaining the variation in GDP, symbolizing how the non-use of human resources affects the future GDP. On the other hand, variables like LMNP, MEGR, and SHD have a relative influence of 0.00e+00, with equal loss of dropouts (7.39e+11). Under the boosting technique, it is understood that when GPO, GDIPC, PRR, and YNEE are considered, these variables do not add any further predictive power for GDP. Indeed, the results show that the broad social results and poverty factors are the main channels through which the GDP is defined, thus confirming the strong structural relation between prosperity and social equity in the BES framework. See

Table 12.

The results obtained in the above table correspond to the Additive Explanations produced by the application of the Boosting Regression model to the E-Equity (E-Equo) component of BES, in an attempt to explain and predict GDP in Italian regions and in the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano. The Base value represents the average GDP expected in the absence of any of the explanatory variables; then, each indicator changes this Base value in an upward or downward direction to finally obtain the expected GDP in each region (Case). In the five cases, the expected GDP ranges from 6.18 × 10¹¹ to 7.30 × 10¹¹, thus clearly showing territorial disparities. These are mainly produced by YNEE, PRR, and GPO, whereas LMNP, MEGR, and SHD are kept constant at 0, thus indicating that in this model and database, they do not add any explanatory power to GDP. The YNEE indicator adds an 8.25 × 10⁷ constant and positive effect in all five cases, thus indicating that in the model learned by the boosting algorithm, YNEE is positively linked to slightly higher values of expected GDP. This may be related to the tendency of larger or more complex regions to have higher GDP and higher numbers of NEET youth. PRR adds a very strong and stable positive effect of 1.28 × 10⁹ in all five cases, thus indicating that it is one of the most important equity-related indicators in determining GDP values. This result clearly reveals an important structural aspect of Italian regional economies: it is possible to have high GDP values and high social inequality at the same time. GPO, on its turn, exerts a negative effect in all five cases, and its values range as low as -1.18 × 10⁴ in some of them. This indicator is one of the main determinants of regional differences and clearly indicates that in regions where conditions in this dimension of equity are worse, it is expected that GDP will decrease in comparison to the Base values. GDIPC finally exerts a small but negative effect and may be considered as an adjustment factor rather than as one of its main determinants. Overall, the boosting model shows that the E-Equity domain of the BES approach affects the GDP via a very limited number of extremely important variables that describe the deep structural relationships between economic performance and territorial inequality. See

Table 13.

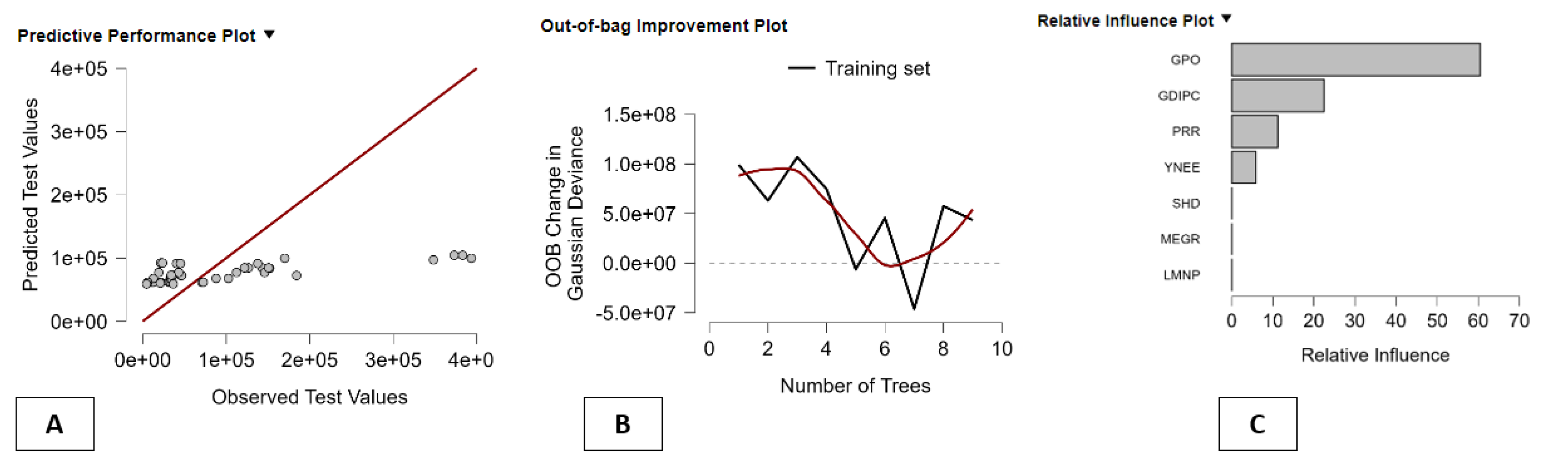

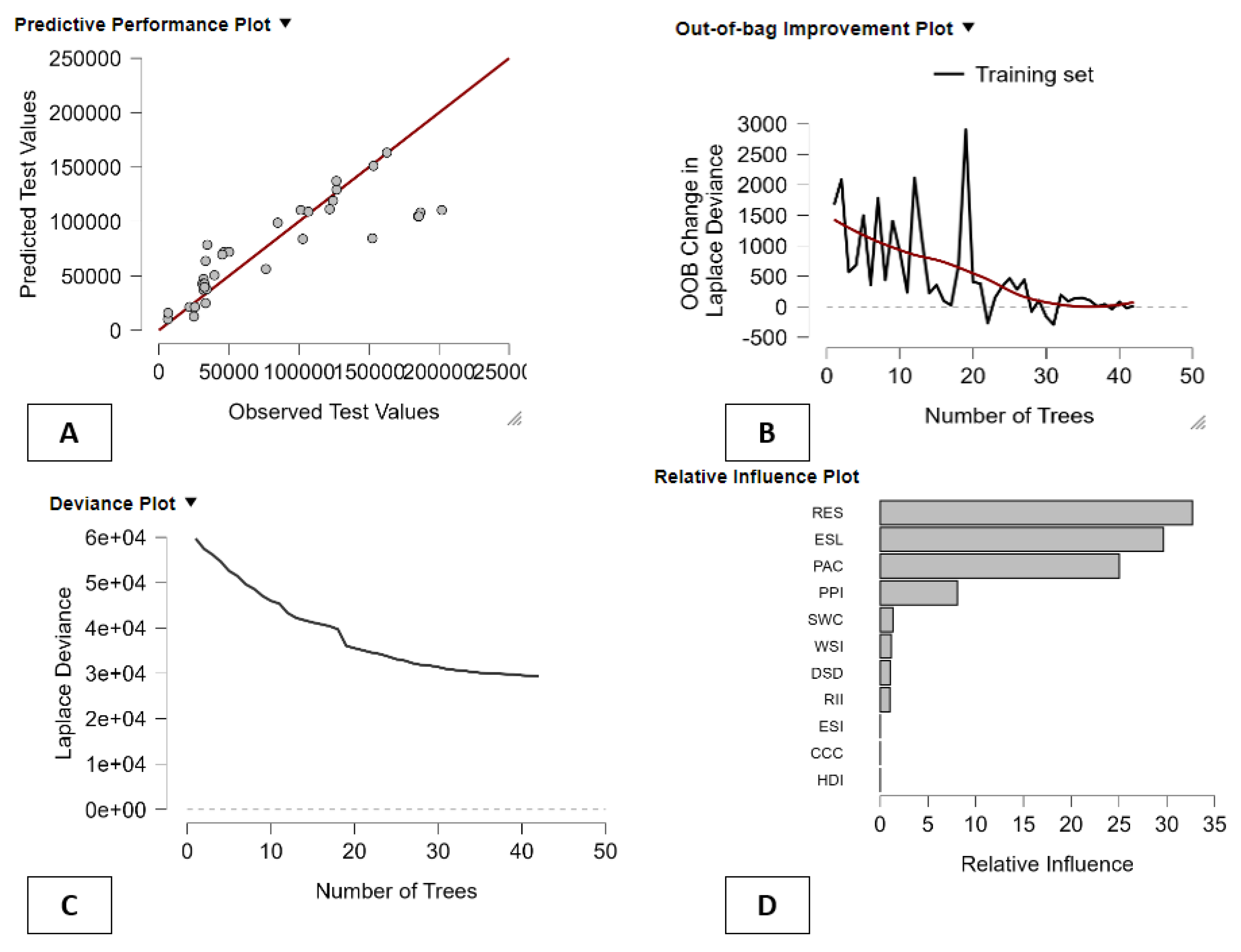

The figure provides a very informative graphical representation of how the boosting regression algorithm performs when used on the E-Equity component of BES in relation to GDP. Panel A plots the data points of the observed values of GDP on one axis and their predictions on another axis, and the red line represents perfect prediction. Most data points are seen to be close to it, especially in the lower to middle range of values of GDP, and it can thus be said that it captures a large amount of systematic variation in regional GDP. A certain amount of spread is seen, especially in higher values of observed data points, and it can thus be said that regions that are extremely rich are more difficult to predict accurately, which is in line with what would be expected of boosting regressions. Panel B illustrates the evolution of the model’s predictive accuracy with the number of trees added to the boosting model. The y-axis indicates the change in Gaussian deviance on the out-of-bag observations and therefore estimates the generalization accuracy of the model. At the beginning of the learning process, the model’s improvement (measured by the positive change in Gaussian deviance) is very strong, which means that the early trees contain valuable information. After 5 to 7 trees, the graph flattens and even becomes negative at a point, which means that beyond that point, the trees start to overfit the data and do not improve the model’s out-of-sample accuracy anymore. This result confirms that the model with the best performance on this particular data set has a relatively small size due to the limited sample size and the strong signal of the few important variables. Panel C provides the ranking of the E-Equity indicators based on their relative importance in the prediction of the GDP. GPO is the most important source of explanatory power, followed by GDIPC and PRR. YNEE is the next most important indicator, while SHD, MEGR, and LMNP are relatively inconsequential. These results indicate that the Italian regional GDP is mainly driven by a subset of social and distributional equity indicators, where GPO is the main channel transmitting the message from the E-Equity dimension to economic performance. Overall, the figure above illustrates the power of the boosting model: simplicity and strength.

Figure 3.

Boosting Regression Performance and Feature Importance for the E–Equo–GDP Relationship. Panel A shows observed versus predicted GDP, Panel B reports out-of-bag improvement as trees are added, and Panel C displays relative feature importance. Together, they indicate that a small boosting model driven by key equity variables—especially social outcomes and income—provides strong predictive accuracy for regional GDP.

Figure 3.

Boosting Regression Performance and Feature Importance for the E–Equo–GDP Relationship. Panel A shows observed versus predicted GDP, Panel B reports out-of-bag improvement as trees are added, and Panel C displays relative feature importance. Together, they indicate that a small boosting model driven by key equity variables—especially social outcomes and income—provides strong predictive accuracy for regional GDP.

5.2. How Clustering Reveals the Structure of the E-Equo–GDP Relationship

The normalized results provide an effective and multi-dimensional comparison of the five clustering algorithms based on seven different complementary criteria of clustering quality. Since all criteria are scaled to ensure that larger values represent better performance, it is possible to make a coherent comparison of clustering quality based on this table. Hierarchical clustering is revealed to be the best-performing clustering algorithm in general because it obtains the highest score of 1.000 on four of the most structurally informative criteria of clustering quality: maximum diameter (after inversion), minimum separation, Pearson γ index, Dunn index, and entropy index. This set of criteria is particularly informative because it indicates that there are compact clusters when maximum diameter is high, well-separated clusters when minimum separation is high, high similarity between clustering and distance matrices when Pearson γ index is high and close to 1, well-balanced compactness and separation when Dunn index is 1, and that there is no over-fragmentation of observations in regular and well-structured clusters when entropy index is 1.000. K-Means has optimal performance exclusively on the Calinski-Harabasz index (1.000) and moderate performance on Pearson’s gamma (0.574) and HHI (0.537), but performs abysmally on minimum separation (0.000) and reports poor performance on the Dunn index and entropy values. This result indicates that, although K-Means produces dense clusters, it fails to ensure a proper level of separation among them. In Model-Based Clustering, optimal performance is obtained on HHI (1.000), reflecting the best possible balance among the sizes of the resultant clusters, but weak performance on entropy (0.000) and moderate performance on geometric and relational indices is observed. This result shows that statistical balance has been obtained at the cost of clarity in the resultant structure. In Random Forest Clustering, intermediate values on almost all indices are obtained, and it performs sub-optimally in all aspects, reflecting its stable performance rather than optimal results in clustering analysis. In Fuzzy C-Means, the performance is the weakest among all methods and reports zero performance on both geometric and separation indices, suggesting poorly defined and overlapping clusters. To sum up, Hierarchical clustering is clearly the best algorithm since it outperforms in the most important measures of clustering quality: compactness, separation, and structural properties, and thus represents the most reliable way of discovering meaningful groups in data. See

Table 14.

From the hierarchical clustering analysis, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the relationship that exists between the E-Equo dimension and GDP for Italian regions and autonomous provinces. For all the variables, positive values point towards above-average performance, while negative values point towards below-average performance. Clusters 3 and 7 are the most distinguished groups, as they are the strongest in terms of economic performance. Cluster 3 has the highest GDP value of 1.784 and very high GPO values of 2.115, indicating high poverty alleviation and high social protection, despite low performance in PRR and labor market indicators. Cluster 3 represents wealthy regions with high redistributive capability but low inclusion dynamics. Cluster 7 is even more distinctive, as it has high GDP values of 1.180 along with very high GDIPC values of 3.402 and GPO values of 1.698, indicating that the regions have very high disposable income and high equity, but low performance in PRR, LMNP, and MEGR, indicating structural weaknesses in labor market participation. On the other hand, Clusters 2, 4, and 5 represent structurally weak areas. Of these, Cluster 4 is the most challenging area with very low GDP (-1.571) and very high social distress factors such as PRR (2.058), MEGR (1.811), and SHD (2.276), in addition to extremely low YNEE (-2.176). Cluster 5 also represents similar challenging areas with similar high PRR (1.262), similar low YNEE (-2.145), and marginally better GPO. Cluster 1 represents moderately weak areas with low GDP and limited social protection, whereas Cluster 6 represents areas that are intermediately weak with slightly above average GDP and YNEE of 0.540 but weaker labor market performance. In general, the results from the hierarchical clustering emphasize a strong polarization: on one side, a few territories with high GDP and a privileged social status, and on the other, a large number of territories with a weak economy, an excluded labor market, and a high risk of poverty. The analysis points out the strong territorial inequalities in the E-Equo-GDP relationship in Italy. See

Table 15.

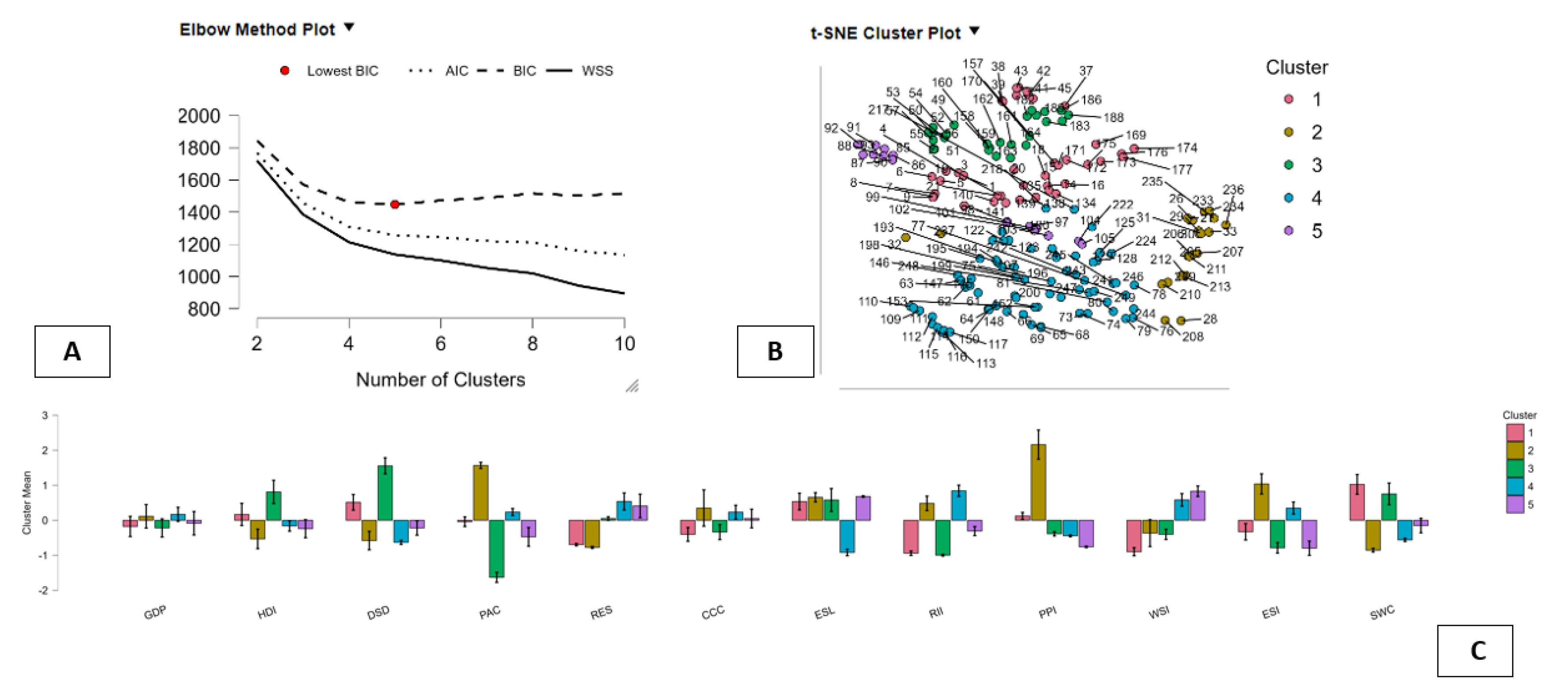

The figure provides an integrated visual assessment of the hierarchical clustering process performed on the dataset through the incorporation of three different tools for model assessment: Elbow Method plot (A), cluster map of t-SNE results (B), and dendrogram plot (C). Taken together, these three subplots of the figure collectively form a robust set of evidence in support of the presence of seven clusters in the data and help to facilitate understanding of both the model fit and interpretation of clustering results. Subplot A of the figure displays an Elbow Method plot where three different model selection criteria are plotted against cluster number: WSS, AIC, and BIC criteria. It is observed that for each of the criteria, there is a sharp decrease in values when passing from two to approximately six or seven clusters, beyond which there is no significant further improvement in model fit. Most notably in this regard is that BIC reaches its lowest point at approximately seven clusters (marked with red dot), clearly signifying that it is the most reduced model that still has the ability to account for variability in the data. This further indicates that it is at seven clusters that there is an optimal tradeoff between model fit and model complexity. Subplot B of the figure displays a two-dimensional representation of the data obtained by applying t-SNE to it, where different colors are used to represent different clusters of the data. The different clusters are relatively well separated with no significant overlap between them, especially for clusters 2, 4, 5, and 6. This further indicates that it is indeed true that the hierarchical clustering algorithm has been able to identify statistically different groups of data that are also geometrically coherent in their multivariate space representation. The elongated nature of different groups further indicates that there are gradients in different groups, but their boundaries are still well defined. Subplot C of the figure displays a representation of the hierarchy of clustering in the form of a dendrogram plot where heights of different branches represent significant differences between different groups of data, especially at higher levels of hierarchy. The cutting point for seven clusters in this plot indicates that it is at this point that there are well-defined branches of larger size rather than cutting up homogeneous groups of data at random points.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical Clustering Diagnostics and Seven-Cluster Solution for BES–GDP Profiles. Note: Panel A identifies seven clusters through the BIC minimum, Panel B shows their separation in t-SNE space, and Panel C confirms distinct hierarchical branches, indicating well-defined territorial regimes linking BES indicators to GDP.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical Clustering Diagnostics and Seven-Cluster Solution for BES–GDP Profiles. Note: Panel A identifies seven clusters through the BIC minimum, Panel B shows their separation in t-SNE space, and Panel C confirms distinct hierarchical branches, indicating well-defined territorial regimes linking BES indicators to GDP.

6. GDP and the Sustainability Dimension of the BES Framework

Economic development and environmental sustainability are being increasingly linked, especially within the Italian Benessere Equo e Sostenibile (BES) approach, where environmental conditions and people's awareness about environmental hazards are included, in addition to GDP. The relationship between three important aspects of environmental sustainability, namely the Heatwave Duration Index, Climate Change Concern, and Biodiversity Loss Concern, and the GDP within the Italian regions and the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano, during the period 2012-2023, will be explored in this study by estimating a panel data model that links economic output with both environmental stress and environmental awareness. The question that would be answered by this study would be if environmental pressures and concerns are by-products of economic development or if they are deeply rooted within the process of economic development. See

Table 16.

Specifically, we have estimated the following equation:

where i=21 and t=2012-2023