1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-assisted radio transmission is an effective solution for emergency situations in post-disaster scenarios such as collapse of communications and computing infrastructure due to military operations or natural disasters (e.g., wildfires, floods, and earthquakes) [

1]. Such life-saving technique is vital in establishing the required urgent basic Uplink (UL)/ Downlink (DL) wireless connections, and more importantly in the provisioning of multi-access edge computing (MEC) capability. UAV typically hover above disturbed and affected zone to provide the required radio communications and MEC services [

2,

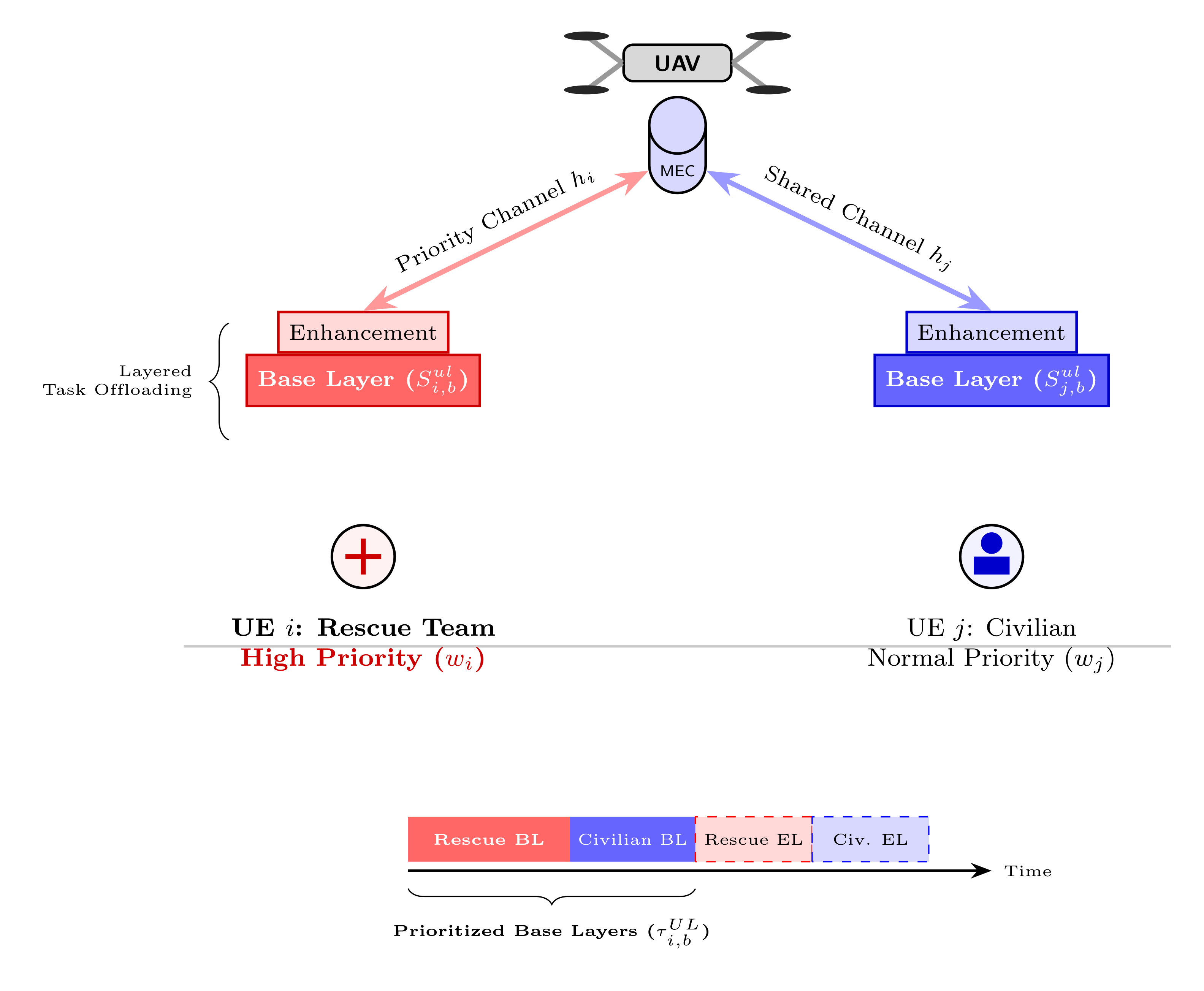

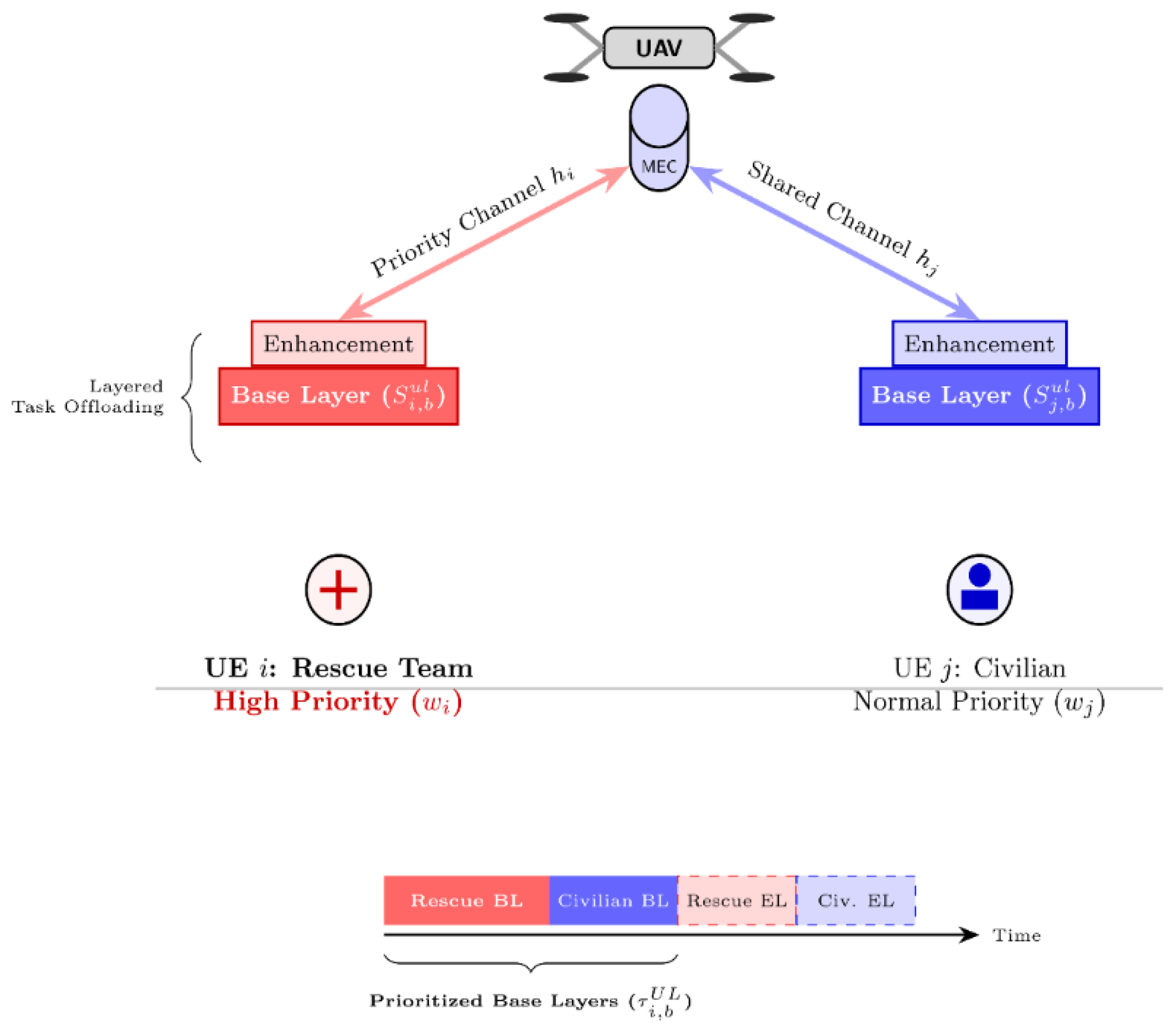

3]. Upon establishing the radio connection, each ground user offloads a computational task to the nearby UAV using time division multiple access (TDMA). The result of execution is then sent to the user after the UAV has processed the task (see

Figure 1).

Unlike standard MEC servers, UAV has limited on-board power and processing resources [

4], make it challenging to support all user tasks simultaneously and reliably. Additionally, all users will compete for the shared wireless communication resources (e.g., power or spectrum), but, not all of them face an exact level of emergency situations [

5]. For example, a rescue team needs image analysis and processing to quickly locate victims (high priority), while another, e.g., second respondent may need less critical processing (low priority), i.e.,

inter-user priority. In addition to that, per-user (or

intra-user) priority is also required since mobile application typically comprises both base layer (BL) representing critical data and enhancement layers (EL) which are optional as depicted graphically in

Figure 1. This two-layers paradigm is the core of the proposed layered offloading scheme as discussed in the upcoming sections.

Several existing systems treat tasks as indivisible units, neglecting the importance of prioritizing essential task components under resource constraints in a post-disaster scenario [

1]. Therefore, this research addresses the problem of reliably offloading layered tasks—comprising critical and optional parts—over UAV-assisted wireless networks while prioritizing user scheduling over shared wireless network. The proposed scheme, entitled “Reliable Layered Transmission (RLT)”, has two novel features:

(i) divide task’s data into multiple layers with different priorities, where base layer is the most critical (e.g., location or low-resolution image of a survivor) while the other enhancement layers are optional;

(ii) assign different weights for various user (inter-user priority) e.g., for rescue teams or emergency users. It also optimizes the total offloading latency by performing joint communication and computation resource allocation to ensure reliable transmission and processing of the most critical task layers of prioritized users.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Related works are highlighted in

Section 2. Channel model and UL/DL communications and computation models are all presented in

Section 3, while the optimization problem formulation is discussed in

Section 4. In

Section 5, the solution analysis is introduced through three lemmas. After that,

Section 6 discusses the obtained results to show the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm compared to several baseline algorithms, and finally the conclusion for this paper is given in

Section 7.

2. Related Works

The last few years have witnessed the development of MEC-enabled UAV network as a new technology to enhances computational processes, reduces delay, and supports the application of real-time services in volatile and highly mobile wireless networks. Studies [

6,

7] have improved task offloading, computed task efficiency and energy consumption in UAV networks. However, their work did not focus on task priorities.

While studies [

2,

8] have focused on resource allocation and task offloading in UAV using joint optimization although, their work does not support real-time and is not scalable. Although the study [

9] have developed a user-density-based framework for real-time offloading model using UAV networks but Dedicated to the sporting event only, not for general use.

[

10] introduced an architecture designed using deep reinforcement learning (DRL) for joint computation offloading and resource allocation in multi-user MEC systems in an attempt to reduce a weighted sum of delay and energy cost. While their algorithm is appropriate for dynamic workload adaptation, their assumption involves ground MEC end points as static systems and does not facilitate adaptation in dynamic systems that could be applicable in UAV communication systems. In similar vein, [

11] examined optimal power and time allocation schemes in orthogonal and NOMA/NOMA-assisted multiple access communication in MEC systems. The theoretical derivation in this study presumes major reductions in energy cost, which is, only applicable in small systems whose communication channel is static.

Some research surveys have also provided a comprehensive overview of the communication systems of MEC and UAVs separately in the past. [

12] the study discussed multi-access computing (MEC) architectures, and offloading methods, emphasizing the importance of reducing access time and conserving energy, although it is still a conceptual study and lacks UAV integration. In contrast, the review conducted [

13] included an analysis of FANET networks that addressed the networking difficulties specific to FANET networks, including those related to multi-drone communication, routing protocols, and mobility management, although it lacked any form of edge computing or computation offloading.

According to [

14,

15] the combined studies have shifted the focus of MCC design from single-user and uplink-only resource usage to comprehensive allocation and scheduling but not support UAV. While previous study [

16] developed framework to improve energy and security of offloading for UAV systems suffer from weak performance in disaster covering and [

17] developed framework to enhance reliability in MCC over fading channel using superposition coding but not compatible with the UAVs.

[

18] addressed an offloading model for various IoT tasks using logic-based Benders decomposition for task offloading in dynamic scenarios. Although this method nearly achieves optimal task latencies in offloading strategies, centralized processing complexity makes this work less suitable in highly dynamic or mobile networks like UAV communication networks. In contrast to research related to MECs, a comprehensive review of UAVs for photogrammetry and 3D mapping tasks was conducted by [

19], focusing on fixed-wing UAVs in civil missions and fails to consider real-time processing.

Moreover, the study [

20] improve reliability using federated learning in multi-UAVs enable-wireless network at the same time, suffer from convergence is delayed, requiring high computational capabilities. While [

21] used deep RL to optimize UAV’s path based on user location to reduce delay ignoring the importance of prioritizing tasks.

This paper fills the gap of prioritization of critical data and also optimal allocation of radio and processing resources due to limited resources on UAVs by answering the following two questions:

- (a)

How to reliably prioritize tasks offloading in post disaster-scenario via UAV-based MEC networks?

- (b)

How to efficiently allocate both radio and processing resources in such network to achieve optimal utility, namely minimizing the sum of total end-to-end offloading latency?

3. System Model

Suppose a single UAV is flying over a disaster zone at location

and acting as an aerial MEC server. The UAV establishes both uplink and downlink wireless links via TDMA. There are a total of

ground users deployed in the area, where the

user is located at location

For clearer presentation, channel model is presented in

Section 3.1 while

Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 are dedicated to the UL/DL communication and MEC computation models, respectively.

3.1. Channel Model

Consider a general model for composite UAV channel with power gain defined by:

where is the path loss – based distance (linear scale), refer to shadowing (linear scale), and refer to channel coefficient under a small-scale rician fading model. The PL itself is given by

where

refer to the path loss exponent (2 for LoS, >2 for NLoS) [

22],

is the distance between UAV and user

(meter), and

refer to a reference distance (1 meter). The shadowing components reads

is the standard deviation of shadowing (dB), and points to zero-mean gaussian random variable (dB). Finally, small-scale fading has the mathematical formulation as

is the LOS part, is the imaginary unit, points to real part of multipath, and indicates imaginary part of multi-path with

, where is the rician factor

The rician factor in linear scale is given by: The real and imaginary parts of multipath are modelled as Gaussian random variable with normal distribution as indicated in (6)

3.2. Communications/Computation Model

Considering the task offloading of ground user in a UAV-assisted mobile edge computing system. Each user has an input task size (bits) sent to UAV via UL connection and similarly bits of data encoding the result of execution sent in DL. Each offloaded bit utilizes computational load of (CPU cycles) where denotes the computational complexity measured in CPU cycles/bit.

3.2.1. UL Communication Model

Moreover, also consider a practical scenario where the mobile applications can be partitioned into base layer (BL) and enhancement layer (EL). In this method, the BL gives the minimum quality of service that is guaranteed to all critical users to receive an essential quality of service (e.g., a certain minimal data rate, reliability, emergency messages or low-resolution video). The EL, on the other side, provides superfluous service quality, which can be opportunistically granted to the users based on residual resource availability above and beyond the base layer utilization. A hierarchical prioritization is obtained as the base layer serves the critical users and by dividing rest of resources among them and the enhancement layer, guarantees basic service while providing best possible overall user experience.

The total number of offloaded bit sent in UL consist of sum of both BL and EL input task size as:

where the represent the number of transmitted bits during the BL offloading and represent the number of offloading bits during the EL.

The achievable uplink rate (in bps) for sending to UAV is given by:

where

is the UL transmission bandwidth allocated for BL task,

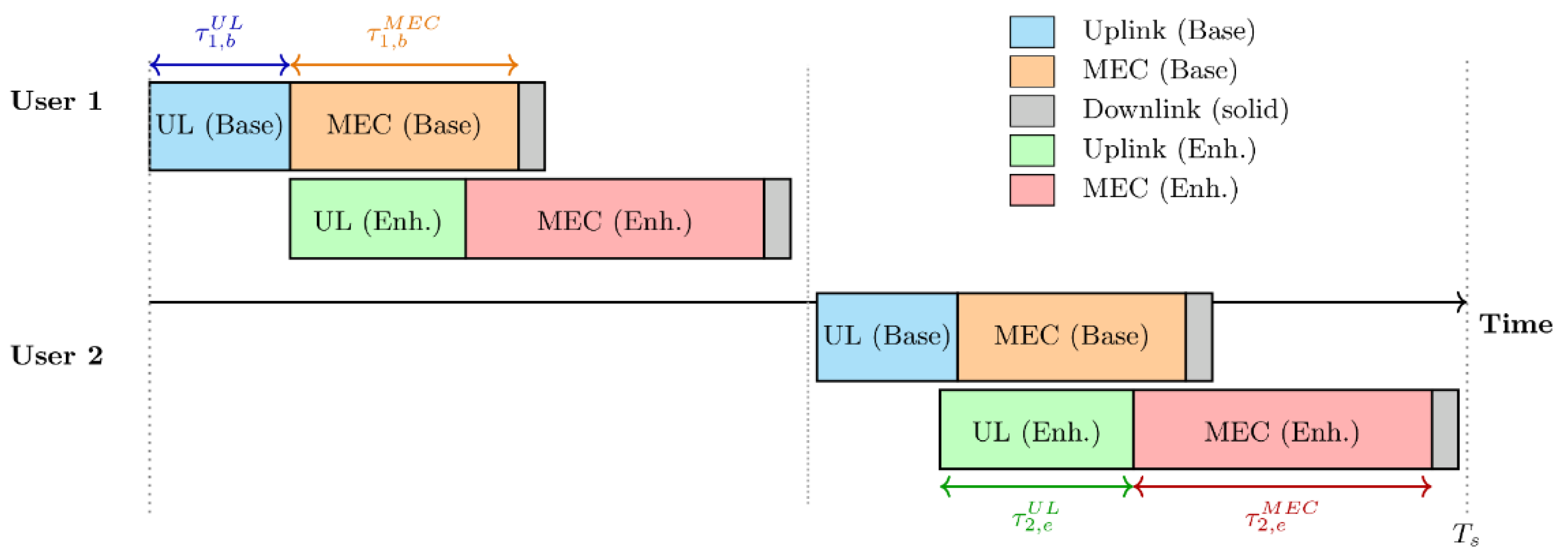

represent fraction of UL TDMA frame allocated to prioritize BL task transmission (unitless) as depicted in

Figure 2,

refer to the nosie power density (Watt / HZ),

points to UL channel gain, and

is the BL transmit power of the user device (Watt).

Similarly, the rate (in bps) needed for sending in the UL direction reads:

where represent fraction of UL TDMA frame allocated to prioritize EL task transmission (unitless), is the UL transmission bandwidth allocated for EL, and is the transmit power of the user device during EL offloading (Watt).

The UL time (Seconds) for task uploading reads:

which depends on total input task size (in Bits), transmit power (watt) and total UL transmission rate.

3.2.2. UAV Computation Model

The computation time (Seconds) required to execute the offloaded task of user at UAV MEC server is given by:

which is depend on input task size , computation complexity (CPU cycles / bit), Fmax is the CPU frequency of UAV processor (cycles / sec.), while is a fraction of CPU frequency allocated to the users with constraints (unitless), ,

3.2.3. DL Communication Model

Similar to UL, the downlink rate (in bps) needed to send the output bits, encoding the results of execution from UAV to user is mathematically stated as:

where transmission bandwidth of UAV is the DL bandwidth, refer to the fraction of DL TDMA frame allocated to task downloading (unitless), nosie power density (Watt / HZ) and DL channel gain.

Hence, the DL transmission time (Seconds) is:

which is function of output task size (number of downloading bits) and DL transmission rate in bps, given in (12).

Finally, the total offloading time for each task is given as:

4. Problem Formulation

The goal of this section is to formulate a priority-aware joint communication and computation resource allocation under UAV-enabled offloading. The objective is to reduce the total weighted sum offloading delay for critical users under power and resource constraints. Mathematically stated as in P.1:

S.t:

(C.1) (C.2) (C.3) (C.4) (C.5) (C.6) (C.7)

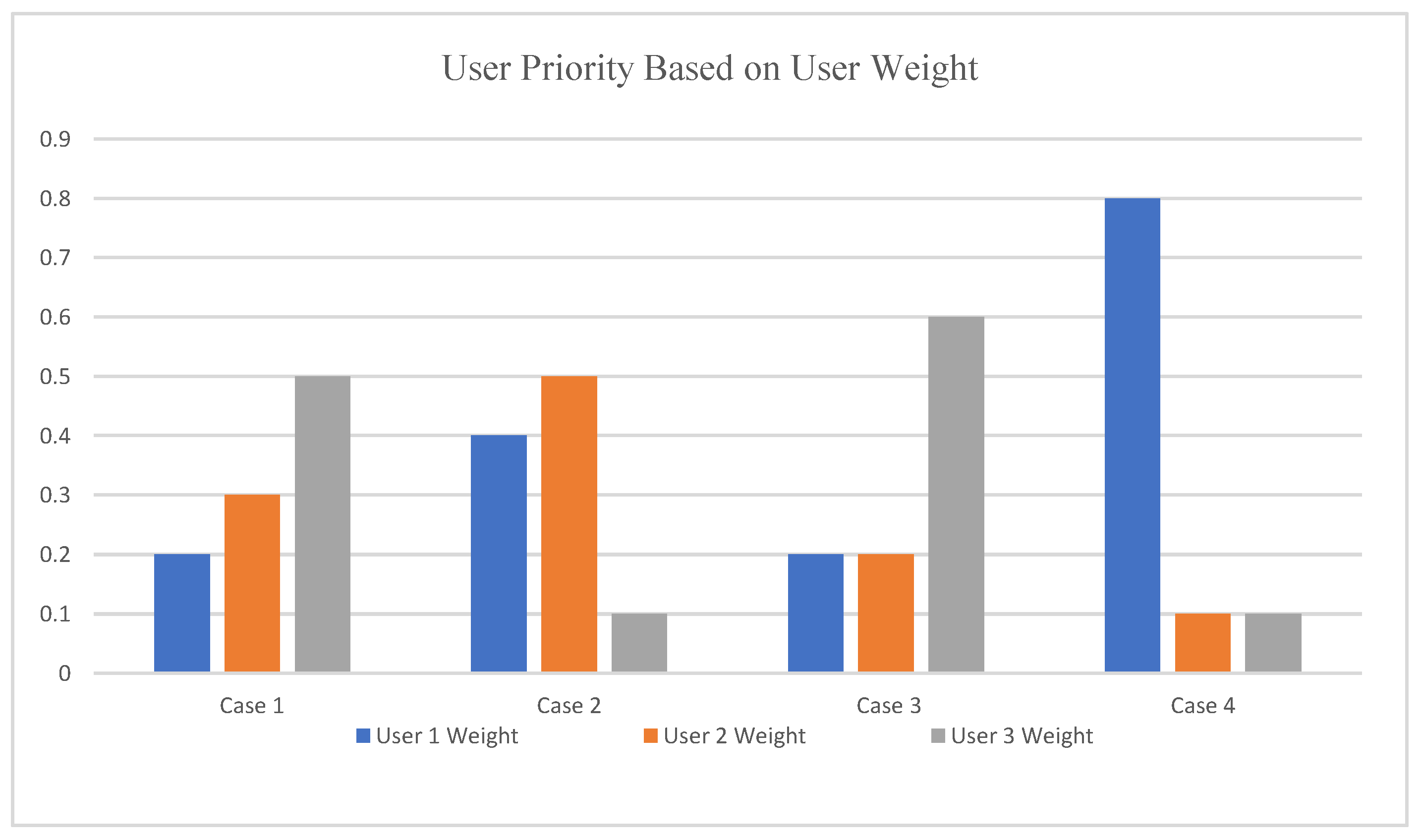

reveals two types of priorities: the first is priority between users based on user weights, while the second is the intra-user priority based on layered transmission (BL and EL).

Constraints (C.1) ensures that BL rate is greater than or equal to the given minimum rate for priority assurance; (C.2) gives per user layered transmission; (C.3) to ensures the BL task is fully uploaded and executed before EL for

user in post-disaster scenario as it clear in

Figure 1 (b); (

C.4) indicates the power of the both BL / EL are greater than or equal to zero ; (C.5) ensures the power of the BL and EL are smaller than or equal to total uplink power; (C.6) refers to a fraction of CPU frequency allocated to the

users with constraints is smaller than or equal to the CPU frequency of UAV processor; and (C.7) indicates that the UAV power for

users is smaller than or equal to the maximum download power.

Note that intra-user priority is enforced via (C.1)-(C.3) while inter-user priority is embedded in the objective function.

5. Solution Analysis

The presence of the time allocation variables

together with the logarithmic rate functions (8), (9) and (12) renders the optimization problem (

P.1) as non-convex due to the coupling of variables in the objective function. Such problems are known to be NP-hard in general and hence obtaining its global optimal solution is computationally infeasible [

23]. Accordingly, in this section, we will recast the problem into convex one using the following series of transformations in Lemma 1 to Lemma 4. In what follows, we drop additional subscripts and make the dependence on variables implicit for mathematical simplicity.

Lemma 1.

Perspective and Epigraph Reformulation

Let The function:

is jointly concave in for .

Proof. Since

is concave and non-decreasing in

, its perspective

is concave by the perspective transformation property of concave functions [

23]. Hence,

is concave.

With Epigraph reformulation, the uplink latency constraint (10) can be equivalently written as:

where is an auxiliary variable such that . This is non-convex because it multiplies the variable with a concave function . To resolve this, we define a reciprocal variable and rewrite the constraint (16) as:

Lemma 2

.The constraint in (17) is convex in

Since

is concave, the right-hand side is concave. The left-hand side

is affine. The set

is convex because the sublevel set of a concave function is convex [

23].

Using the above transformations, (P.1) can be equivalently written as:

(P.2)

Note that Problem (P.2) is convex because all constraints are affine or convex and the objective is a sum of convex functions. Accordingly, the optimal solution is of (P.2) can be obtained using Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) principles as detailed in the following.

The Lagrangian of (P.2) is:

The stationarity conditions are obtained by taking the derivative of Lagrangian w.r.t to variables as:

Similarly, we obtain for the remaining variables (technical details are omitted due to space limitation)

Substituting back into computational constraint yields:

From the power stationarity condition, the optimal power allocation follows a water-filling structure:

These KKT conditions ensure that the resource constraints are active when optimal. The complementary slackness reads

The convexified problem (P.2) ensures the existence of a globally optimal solution due to convexity of objective and constraints as well as satisfaction of the KKT conditions. Accordingly, the problem admits analytical solutions for the transmit power (in both uplink and downlink despite the fact that downlink calculations are omitted due to space limitation) and CPU frequency allocations as formulated in (20) and (21), respectively. The time allocation, on the other side, is obtained by solving convex subproblem as detailed in . This does not have closed-form expression due to coupling of time variable across users. Nevertheless, global optimality is also guaranteed by the convexity of the subproblem which is solvable in polynomial time via typical convex optimization techniques (like interior-point method). As a closing remark, it is worth to mention that analytical solutions for power and CPU allocations along with the convexity of time allocation subproblem enable computationally-efficient and practical on-board implementation of the proposed algorithm for real-time UAV-assisted MEC scenarios.

|

Algorithm 1 Layered Priority-Aware Offloading and Optimal Resource Allocation for UAV-enabled MEC Network |

1: Input: Channel gains , parameters

2: Initialize dual variables

3: repeat

4: CPU update:

5: Power update:

6: Time allocation: Solve convex subproblem for with constraint

7: Dual update:

and similarly for.

8: until Convergence of objective function.9: Output: Optimal |

6. Results and Discussion

To validate and assess the performance of the proposed scheme under a dynamic composite wireless channel of a UAV-assisted MEC system, we consider simulation of 10 mobile users. The proposed priority-aware resource allocation is compared to three baseline schemes: the enhancement first, equal allocation, and no priority under the same network conditions. Where in the

“Enhancement first” EL layer is offloaded first, while in

“Equal allocation” the power and processing resources are equally allocated among all users; and in

“no priority” scheme, as the name suggests, no prioritization is applied and the whole computation task is offloaded at once. The simulation parameters are listed in

Table 1.

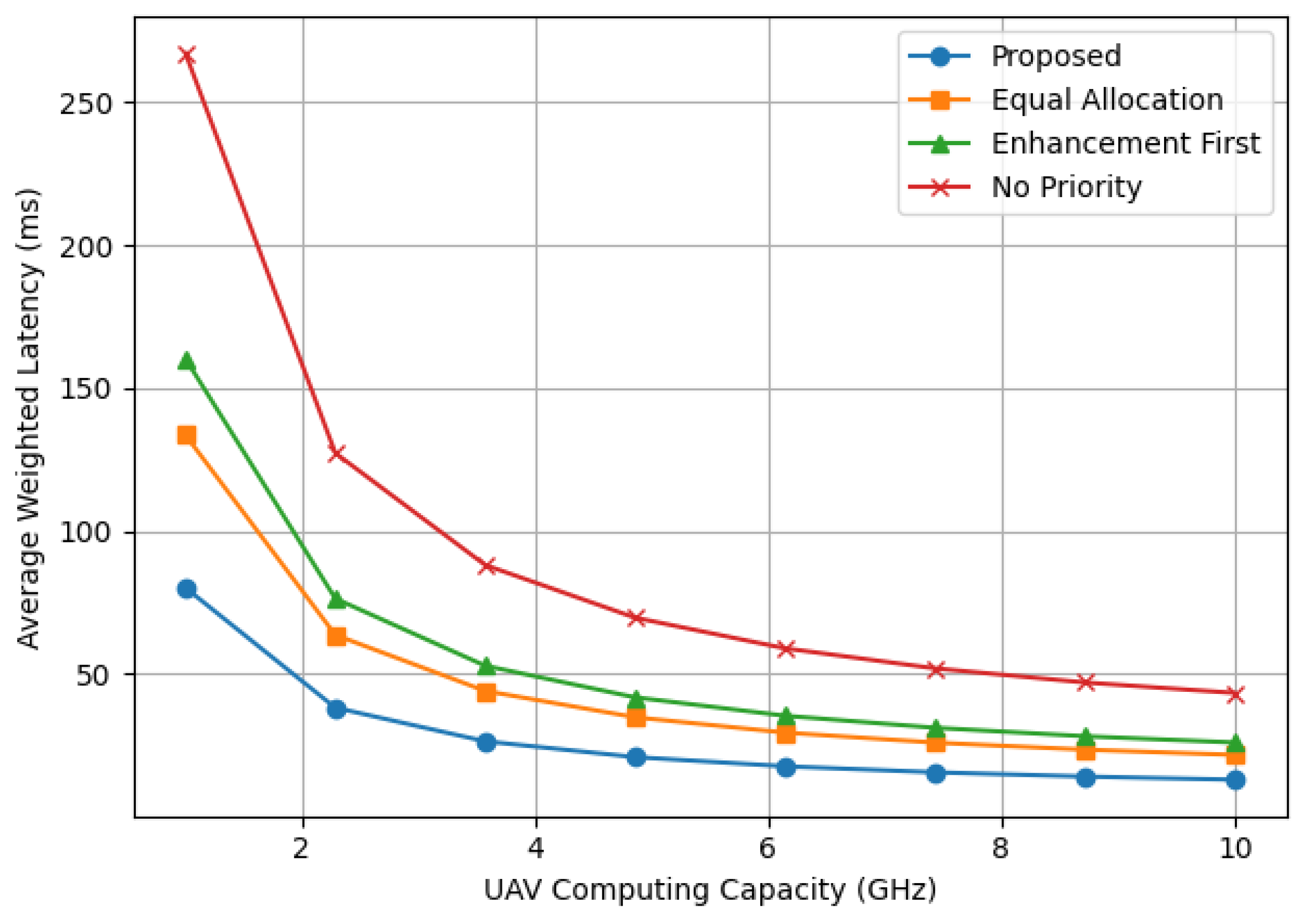

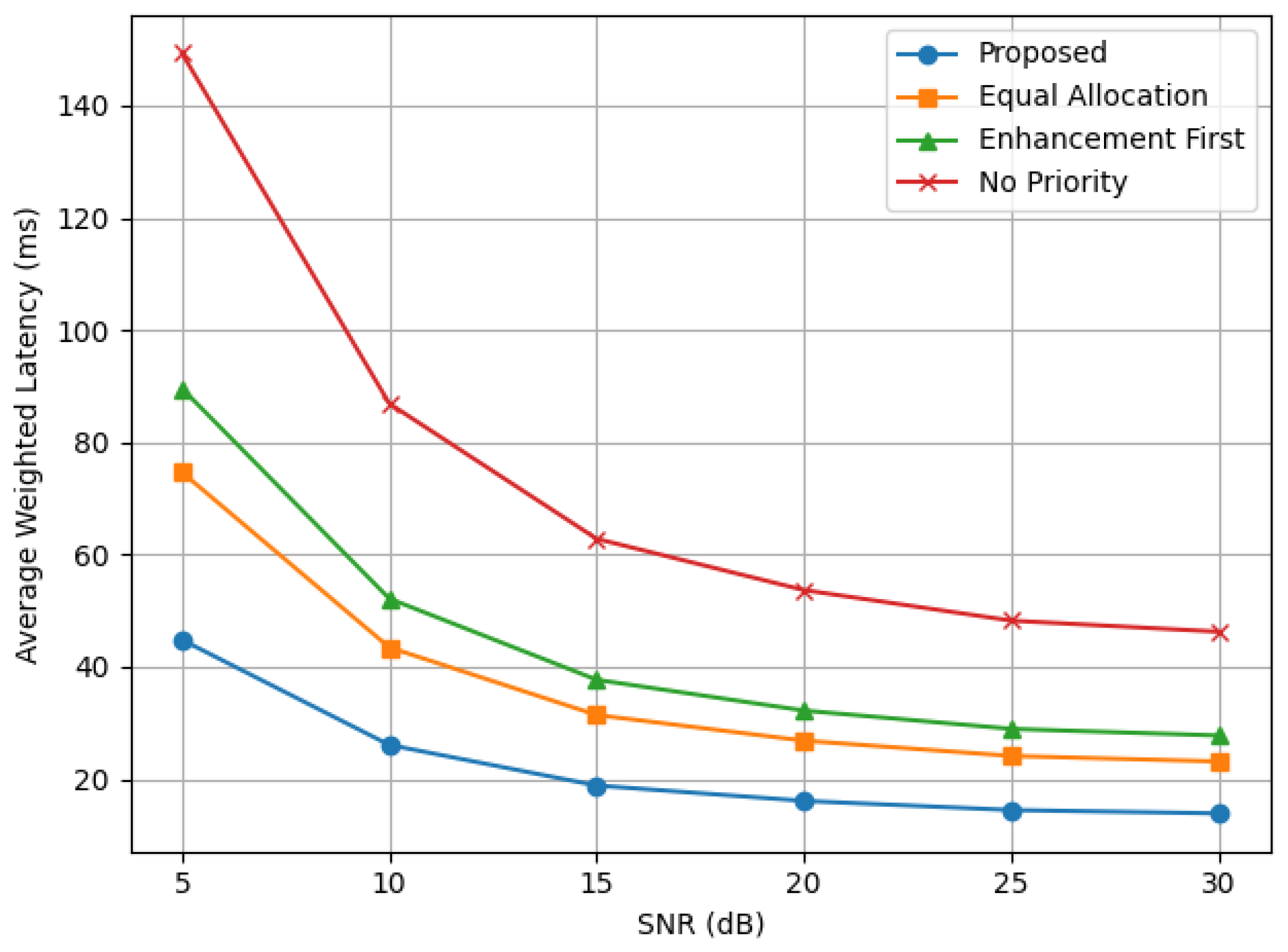

Figure 3 demonstrate the weighted overall latency across all users versus SNR for each of the three resource allocation schemes compare with proposed algorithm. At a signal-to-noise ratio of 5 dB, the proposed algorithm achieves considerable latency reductions vs the baseline algorithms (39.99% reduction vs Equal Allocation, 49.99% reduction vs Enhancement First, and 69.99% reduction vs No Priority). These reductions in latency are attributed to the jointed optimization of radio and computing resources in the proposed algorithm, reducing the overall latency through dynamic adaptation of resources allocation to the MEC according to user priority and channel quality.

Besides reliability, the efficiency of the proposed priority-aware offloading scheme is confirmed by the fact that it achieves the lowest latency across all SNR values as is clear from the results in

Table 2.

As a function of processing capacity of UAV (we plot again the total weighted offloading latency. It is obvious that for all schemes, the total latency decreased gradually as the UAV’s computing capacity increased from 1 GHz to 10 GHz. With the increasing computing capacity of UAV, transmission time is not the only factor contributing to latency; channel randomness also affects it.

At a low computing capacity of 1 GHz, the proposed algorithm shows a latency reduction compared to the baseline algorithms (40% reduction vs Equal Allocation, 50% reduction vs Enhancement First, and 70% reduction vs No Priority) as is evident from the results in

Table 3.

Figure 4.

Latency vs UAV Computing Capacity for Priority-Aware MEC Offloading.

Figure 4.

Latency vs UAV Computing Capacity for Priority-Aware MEC Offloading.

Overall, the results confirm that the proposed priority-based framework offer better performance against resource scarcity with edge computing capability. This underscores its suitability for latency-critical applications in mobile edge computing networks assisted by UAVs as well as guaranteed reliability for BL execution.

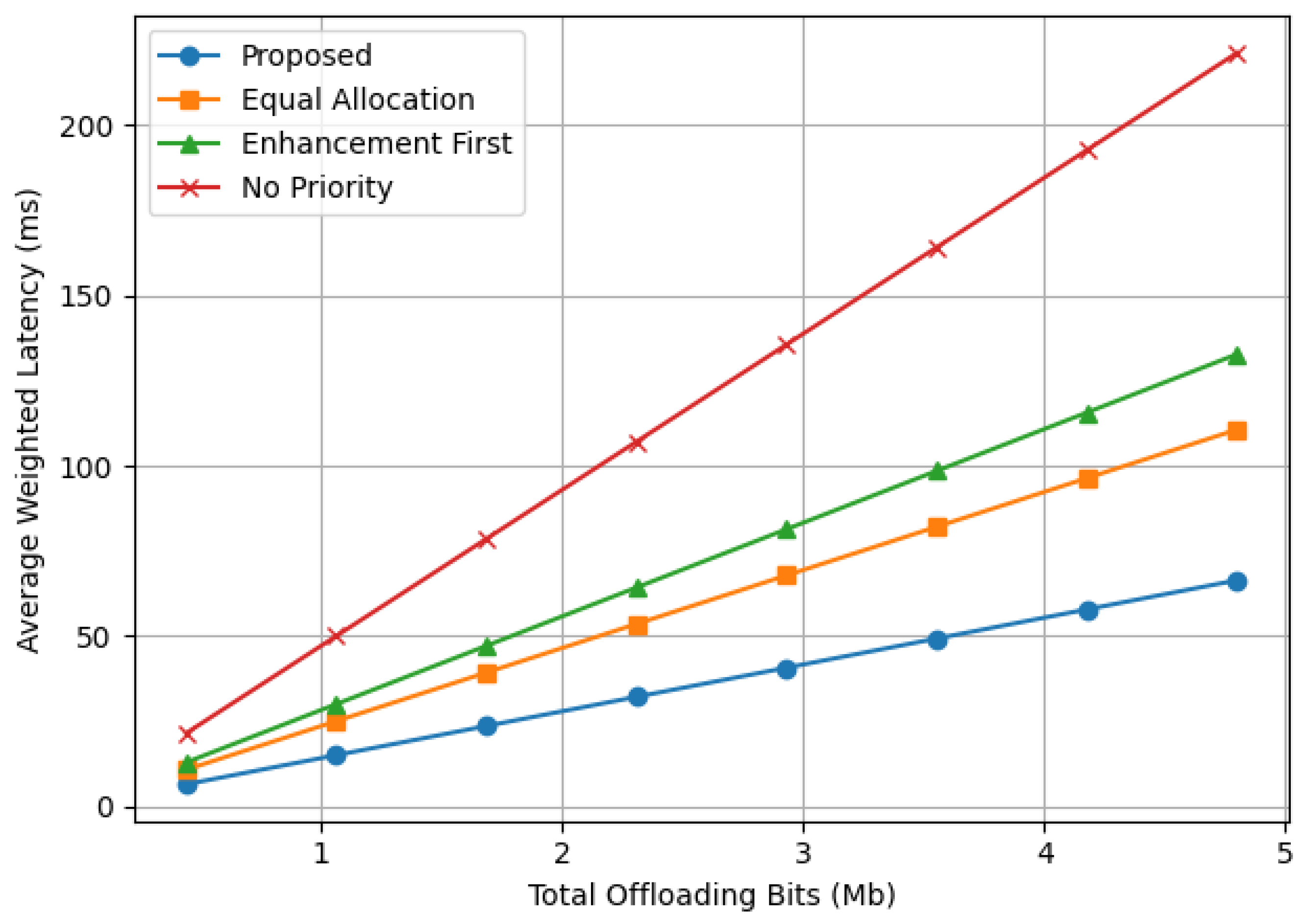

Figure 5 illustrates the variation in total latency as a function of the total input data size (measured in Mbits) for different data offloading algorithms. In all algorithms, latency increases almost with data size. For moderate task sizes, such as 2.93 Mb, the proposed algorithm reduces the total latency by approximately 57.14% compared to average baseline algorithms.

As the total bit size increases to 4.80 Mb, the latency becomes even more pronounced, with the proposed method maintaining, on average, a reduction still of approximately 57.14% compared to conventional average baseline algorithms as is clear from the results in

Table 4.

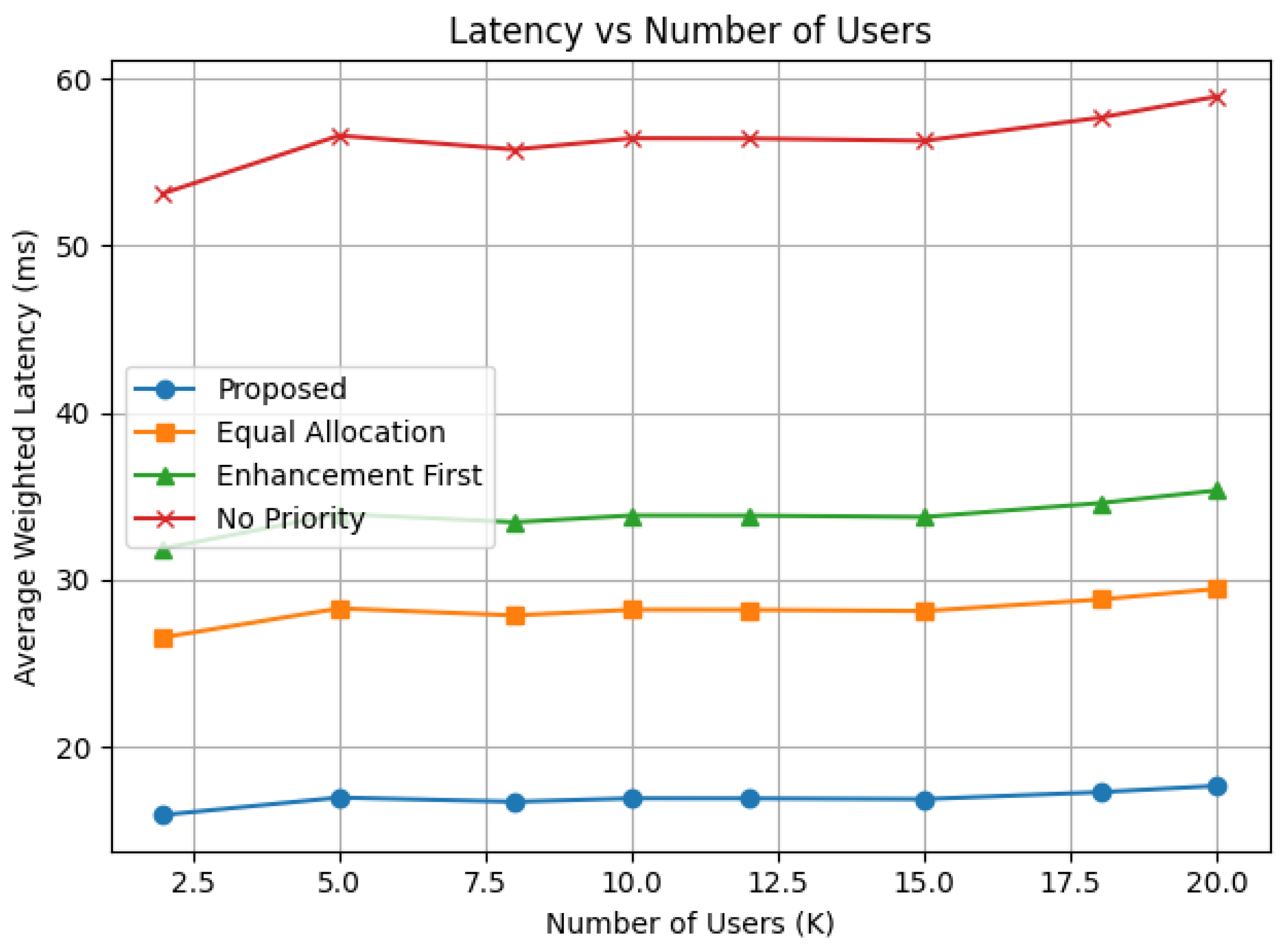

Figure 6 shows that the total latency increases with the number of users for all the resource allocation schemes, as they share the UAV’s computing resources and limited bandwidth and channel resources in both uplink and downlink.

With any given number of users (2-20), the proposed system offers significantly latency reduction than other average baseline schemes. For 10 users, the proposed algorithm reduces the total latency by approximately 57.132% compared to average baseline algorithms by prioritizing user resource allocation and minimizing offloading time as is evident from the results in

Table 5.

Figure 7 illustrates the latency behavior of the proposed algorithm across different user weighting scenarios in a three-users MEC system as reported in

Table 6. This figure shows that the proposed algorithm clearly highlights latency differences between users and weighted states, users with higher weights correspond to higher priority and consistently lower latency, while the latency of less important users increases slightly. This reflects the intelligent optimization behavior of the proposed model.

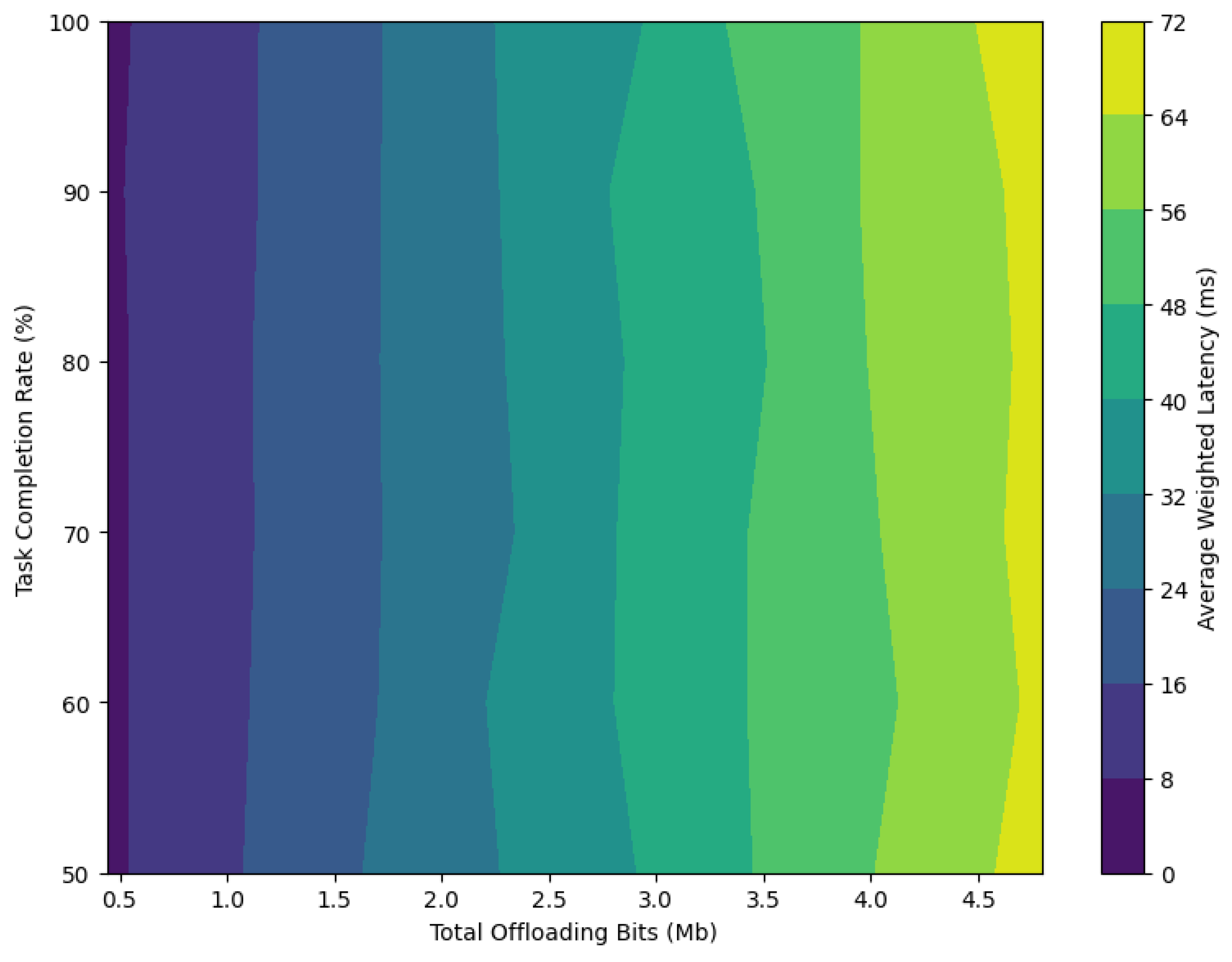

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of offloading bits size on average weighted latency (ms) and task completion rate (%) in a composite fading channel. It is clear from figure of the proposed approach, as the number of bits allocated for offloading increases, the average weighted latency gradually rises due to the continuous increase in the workload on communications and computing. Simultaneously, the task completion rate gradually decreases. This indicates that the system maintains a smooth balance between weighted latency and task completion rate metrics.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we study a UAV-assisted mobile edge computing (MEC) system for disaster relief, where a UAV provides computation and communication services to multiple ground users. Each user task is partitioned into a base layer (critical for reliability) and an enhancement layer (optional for improved quality). We formulate a joint optimization problem of communication and computation resources to minimize the weighted sum latency across all users while guaranteeing base-layer priority through minimum rate constraints. The problem is shown to be non-convex in its native form. After appropriate transformations, we recast the problem into convex and then derive the optimal solution using KKT conditions and obtain a water-filling-like closed form for power and processing capacity allocation. The numerical results reflect that priority-aware joint resource allocation scheme outperforms several baseline scheme. At a signal-to-noise ratio of 5 dB, the proposed algorithm achieves relative latency reductions vs the baseline algorithms (39.99% reduction vs Equal Allocation, 49.99% reduction vs Enhancement First, and 69.99% reduction vs No Priority).

For future directions of this endeavor, it can be expanded to achieve cooperation between multiple UAVs and incorporate more advanced prioritization techniques like NOMA-enabled offloading or superposition coding.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to the conceptualization, implementation, analysis, and writing of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Abbreviations.

| Symbol |

Description |

|

The number of offloading bits during the BL, and EL |

|

The time expression for task uploading and downloading |

|

Computation time, total offloading time |

|

The achievable uplink rate for sending , to UAV |

|

DL rate from UAV to MU |

|

The number of downloading bits |

|

a fraction of CPU frequency allocated to the users with constraints |

| MU |

Mobile user |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| Fmax

|

The CPU frequency of UAV processor |

|

Refer to the fraction of DL TDMA frame allocated to task downloading (unitless) |

|

Represent fraction of UL TDMA frame allocated to prioritize BL, EL task transmission (unitless) |

|

Maximum UL power, Maximum DL power |

|

UL transmission bandwidth allocated for BL, EL task |

|

The BL, EL transmit power of the user device (Watt) |

References

- Kalinagac, O.; Gür, G.; Alagöz, F. Prioritization Based Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted Edge Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Simeone, O.; Kang, J. Mobile Edge Computing via a UAV-Mounted Cloudlet: Optimization of Bit Allocation and Path Planning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 67, 2049–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Tan, L. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Computation Offloading in UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. Drones 2023, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.-H.; Bhargava, B. A Survey of Computation Offloading for Mobile Systems. Mob. Networks Appl. 2012, 18, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, Z.; He, S.; Guo, K.; Wu, Q. Hierarchical Task Offloading for UAV-Assisted Vehicular Edge Computing via Deep Reinforcement Learning. 2025 International Conference on Future Communications and Networks (FCN), LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SerbiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Dehkordi, M.F.; Jabbari, B. Efficient and Sustainable Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted MEC Systems via Meta Deep Reinforcement Learning. ICC 2025 - IEEE International Conference on Communications, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, CanadaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1353–1358.

- Xiao, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Wong, K.-K.; Yang, K. Energy-Efficient STAR-RIS Enhanced UAV-Enabled MEC Networks With Bi-Directional Task Offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025, 24, 3258–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, X.; Bu, Z. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Computation Offloading and Resource Allocation in Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2022-Spring); LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, FinlandDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

- Peng, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D. Efficient dynamic task offloading and resource allocation in UAV-assisted MEC for large sport event. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Gao, H.; Lv, T.; Lu, Y. Deep reinforcement learning based computation offloading and resource allocation for MEC. 2018 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Ding, Z.; Xu, J.; Dobre, O.A.; Poor, H.V. Joint Power and Time Allocation for NOMA–MEC Offloading. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 6207–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, P.; Becvar, Z.; I. Member; I. Member. “Mobile Edge Computing: A Survey on Architecture and Computation Offloading”.

- Gupta, L.; Jain, R.; Vaszkun, G. Survey of Important Issues in UAV Communication Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 1123–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shuwaili, A.N.; Bagheri, A.; Simeone, O. Joint uplink/downlink and offloading optimization for mobile cloud computing with limited backhaul. 2016 Annual Conference on Information Science and Systems (CISS), LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 424–429.

- Al-Shuwaili, A.; Simeone, O.; Bagheri, A.; Scutari, G. Joint Uplink/Downlink Optimization for Backhaul-Limited Mobile Cloud Computing With User Scheduling. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. over Networks 2017, 3, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Hanzo, L. Energy-Efficient Computation Offloading for Secure UAV-Edge-Computing Systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 6074–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.M.; Simeone, O.; Sahin, O.; Popovski, P. Ultra-reliable cloud mobile computing with service composition and superposition coding. 2016 Annual Conference on Information Science and Systems (CISS); LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 442–447.

- Alameddine, H.A.; Sharafeddine, S.; Sebbah, S.; Ayoubi, S.; Assi, C. Dynamic Task Offloading and Scheduling for Low-Latency IoT Services in Multi-Access Edge Computing. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2019, 37, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. UAV for 3D mapping applications: a review. Appl. Geomat. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, Z.; Lam, K.-Y.; Sun, S.; Xiao, L. Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning for UAV-Enabled Networks: Learning-Based Joint Scheduling and Resource Management. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 3144–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shi, L.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Shu, F.S. Path Planning for UAV-Mounted Mobile Edge Computing With Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 5723–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T. S. Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice Second Edition.

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex optimization; Cambridge university press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.H.; Letaief, K.B. Power-Delay Tradeoff in Multi-User Mobile-Edge Computing Systems. GLOBECOM 2016 - 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |