Introduction

The most critical areas for immune and metabolic developments are observed in human pregnancy and early neonatal development. During these two stages, the maternal and neonatal microbiomes undergo drastic changes. The dynamic shifts that occur in this period are linked to complications such as GDM, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia and preterm births (Gudnadottir et al., 2022). The vaginal microbiome has implications on obstetric outcomes. This is evident in lactobacillus dominated flora which provide protective effects whereas low-lactobacillus flora is associated with inflammation and preterm risks (Ahmed et al., 2025). Changes in the microbiome of mothers and newborns can have a variety of negative health effects, such as preterm birth, gestational diabetes mellitus, neonatal sepsis, and other issues.

Neonatal sepsis, chorioamnionitis, gestational diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and preterm birth (PTB) are among the leading cause of both maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortalities globally. Recent studies indicate PTB affects 10% of pregnancies worldwide with its effects spanning developmental delays and increased neonatal health conditions (Ahmed et al., 2025). Similarly, preterm and preeclampsia are the leading cause of death and affects 3-5% of pregnancies globally (Fox et al., 2020). However, neonatal sepsis remains the leading cause of deaths with higher incidences and prevalence in LMICs (Ahmed et al., 2025). Although these clinical manifestations have an immense outcome on neonatal and maternal health there are limited early identification for individuals at risk underscoring the need for urgent and improved predictive tools. Dysbiosis which refers to the depletion of commensal microorganisms and the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria affects pregnancy-related outcomes (Koren et al., 2013).

Microbiome signatures are quantifiable characteristics of microbiome that are associated with healthy or pathologic states (Panzer et al., 2023). Given the accessibility of microbial sampling through vaginal swabs, stool and saliva alongside microbiome profiling offers a new avenue for revolutionizing non-invasive biomarkers in clinical management. This narrative review synthesizes recent information on microbial signatures as biomarkers in maternal and neonatal health. Also, there is much emphasis on the diagnostic potential and integration with precision medicine and personalized care.

Maternal Microbiome and Neonatal Health

The normal flora of the gut is made of bacterial, fungal and viral species that are beneficial and resists the growth of pathogenic microbes (Davis et al., 2022). The maternal gut flora has been linked to the regulation of metabolic processes during pregnancy and influence both maternal and fetal health (Barrientos et al., 2024). Some studies have shown that gut microbiome composition impacts insulin sensitivity, energy metabolism, and inflammation as these processes maintains metabolic health during pregnancy (Enache et al., 2025). However, dysbiosis in the gut microbiome are associated with metabolic disorders such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), overweight and preeclampsia. These clinical conditions poses risk to maternal health and fetal development (Koren et al., 2013). Recent research indicates that a healthy gut microbiota during pregnancy enhances nutrition absorption by regulating inflammation and preserving glucose metabolism. However, insulin resistance and chronic inflammation which doubles as the two of the main risk factors for GDM have been connected to dysbiosis of the normal gut flora (Mora-Janiszewska et al., 2025). Similarly, pregnant women with a diverse and balanced gut microbiome are less likely to develop these metabolic complications (Singh et al., 2023).

The impact of the maternal microbiome extends to the development of the microbiome in infants. Neonates obtain their microbes from maternal and environmental sources. Also, the method of delivery influences the variation in the microbiome as vaginally born and C-section infants share similar microbes to their mother’s vagina and skin respectively (Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010). Additionally, studies indicate that C-section delivery mode is a risk factor for asthma due to the altered gut microbiome (Shao et al., 2019). The dysbiosis of the neonatal flora give room to environmental infections. This increases the risk blood stream infection, normally due to infections by species of Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus., Streptococcus and Enterococcus (Brooks et al., 2014)). Furthermore, similar strains of Streptocossus epidermidis have been found in the Midwestern region of the United States. This can be attributed to the NICU environment they immediately experience (Erickson et al., 2025).

Antibiotics which are used in the treatment of sepsis is implicated in the late onset of maturation in microbiota of neonates. This is attributed to the decrease of microbiome diversity and increased antibiotic resistant genes (Erickson et al., 2025). Other factors such as diet and medications are thought to enhance the effects whereas breastfeeding promoting protection from antibiotic-mediated depletion of Bacteroides in the infant gut (Azad et al., 2016). Similarly, this intervention is beneficial in maintaining the promoting a microbiome composition that supports healthy glucose metabolism and reduces metabolic diseases (Gupta et al., 2024). Also, certain probiotic strains could improve insulin sensitivity in pregnant women at risk of GDM. In addition, breastfeeding supports the maintenance of a microbiome profile that promotes heathy glucose metabolism and lowers the risk of metabolic disorders later in life (Ni et al., 2024)

Vaginal Microbiome and Pregnancy Health

This section deals with various complications that arise from dysbiosis in the maternal microbiome.

Preterm Birth and Miscarriage

A recent study in 2025 highlighted that the Lactobacillus iners during early pregnancy is linked with increased risk of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) (Cavanagh et al., 2025). However, vaginal normal flora of diverse microbiota that Lactobaccilus crispatus normally predominant appears to have an alternative adverse outcome (Pokharel et al., 2023). Unlike Lactobaccilus crispatus which normally maintains an acidogenic vaginal environment, Lactobaccilus iners is metabolically versatile yet less protective and coexist with a diverse Lactobaccilus-dominated environment (Nilsen, et al., 2017). Conversely Lactobaccilus crispatus dominated microbiota is generally associated with reproductive health and some studies suggests that excessive microbial homogeneity may exert context-dependent effects. This may influence immune tolerance and epithelial turnover in numerous ways that differ by host genetics and environmental factors (Armstrong et al., 2025).

Another study also reported that vaginal dysbiosis is strongly associated with spontaneous miscarriage. Findings from the study suggests that reductions in spontaneous Lactobacilllus species correspond with an overgrowth of potentially pathogenic taxa such as Gardnerella, Atopobium, and Prevotella (Pokharel et al., 2023). These microbial shifts were accompanied by elevated inflammatory mediators within the cervicovaginal fluid. Suggesting that local immune activation and disruption of microbial integrity may precipitate early pregnancy loss (Grewal et al., 2022). These findings indicate that vaginal microbial imbalance whether charaterised by dominance of Lactobaccilus iners or Lactobaccilus diversity can trigger inflammatory cascades. This supports the use of the vaginal microbiome /profiling as a potential early biomarker for predicting the risk of preterm births and miscarriages.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

Dysbiosis of vaginal and gut microbiota are known to influence systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, both of which are important risk factors for the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (Farhat et al., 2022; Gerede et al., 2024). GDM is a metabolic disorder among pregnant women with intense glucose intolerance build up in the cells. GDM has effects on both maternal and fetal health (Yao et al., 2025). In mothers, GDM amplifies insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress and predisposes them to pre-eclampsia and cesarian delivery. Neonates are exposed to the excess glucose from the mother and are predispose to fetal hyperinsulinemia and macrosomia (Su et al., 2025). In addition to the clinical outcomes of GDM, there are distinct microbial signatures that suggests a potential biomarker for diagnosis (Nakshine & Jogdand, 2023).

The gut microbiota of 61 pregnant women in their first and fourth trimesters was shown to differ significantly between the healthy and GDM individuals in this prospective research. Esherichia-shigella and klebsiella which are pathogenic were mostly relatively more abundant than beneficial than Bifidobacterium and Faecalibacterium (Yao et al., 2025). The variation in microbial diversity was thought to result from underlying metabolic dysregulation and inflammatory processes that disrupt normal microbial diversity and homeostasis (Tian et al., 2024; Turjeman et al., 2021). Furthermore, functional analysis revealed that, GDM-associated microbiota has shown to enhance carbohydrate metabolism pathways and protein synthesis related functions and transport. These observations are likely to increase GDM development during pregnancy (Gupta et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024; Mora-Janiszewska et al., 2025). These findings suggest a gut microbial composition during early pregnancy and could serves as a valuable diagnostic biomarker for GDM.

Chorioamnionitis and Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM)

The vaginal microbiome in maintaining the uterine sterility also prevent the growth pathogenic microbes. The disruption of this microbial stable environment has been complicated in PROM and chorioamnionitis. Srivastava and Kumar reported that Lactobacillus iners, Gardnella vaginalis, and Provotella bivia were found in women experiencing PROM. However, Lactobacillus gasseri and lactobacillus crispatus were more prevalent in the healthy controls suggesting specific microbial profiles predispose individuals to certain complications (Srivastava & Kumar, 2024). An observational study was designed to evaluate the vaginal microbiota changes in preterm mothers following antibiotic therapy. The study's findings showed that a broad spectrum antibiotic treatment was effective in getting rid of a number of harmful species, including Group B streptococcus and Gardnerella vaginalis (Pokharel et al., 2023). However, subsequent analyses revealed dysbiosis after treatment. This indicates that microbiomes are not fully restored after treatment and increases susceptibility to recurrent infections such as chorioamnionitis and PROM (Kamath et al., 2023).

Placental Microbiome

The concept of the human placenta microbiome is no more a speculation due to the advancements in sequencing technologies. Previous 16s rRNA gene analysis has reported low biomass microbiome with Lactobacillus, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus as the dominant bacteria found in term infants. The suggestion was that these bacteria are responsible for shaping the post-natal immune development (Aagaard et al., 2016). Subsequent studies correlated microbial signals with preterm birth, preeclampsia and neonatal sepsis. Hence, deviations from a normal placental profile might serve as an early warning biomarker (Doyle et al., 2017). However, advances in high-sensitive sequencing and rigorous contamination control have prompted a critical reassessment of these findings.

Recent studies reanalysed 15 publicly available placental 16S data sets with bioinformatic pipelines and stringent contaminant removal. The study reported “core taxa” largely disappeared when controls were applied indicating that most microbial reads originated from environment al or reagent contamination rather than a true placental niche. A culture-based and metagenomic studies reinforced this conclusion since viable colonies rarely recovered from aseptically collected term placentas. (Kuperman et al., 2019; Panzer et al., 2023).

Consensus therefore now lies along methodological rather than biological explanation for most placental microbial signals. Evidence suggests that the majority of sequences reflect contamination from delivery rooms, reagents rather than a stable resident microbiota. Similar conclusion was made by a study using low-biomass-sensitive protocols conclude that most placental 16S signals are delivery-room contamination, reagent DNA or maternal blood filtered by the inter-villous space (de Goffau et al., 2019). Nonetheless, targeted analyzes of placentas affected by chorioamnionitis biopsies continue to find Ureaplasma, Fusobacterium and Mycoplasma by sequencing and quantitative PCR, arguing that pathogenic invasion, rather than commensal colonization, is responsible for positive signals (Chen et al., 2013; Sweeney et al., 2016). This may suggest that microbial invasion pathological states rather commensal colonization is the driver of placental microbial signatures.

Breast-Milk Microbiome

The breast milk microbiome is reproducible, dynamic and modifiable making it a promising target for precision medicine in neonatology. A study using culture-independent samples across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas identified core microbiota such as staphylococcus, streptococcus, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Cutibacterium representing 80% of reads in colostrum and mature milk (Dombrowska-Pali et al., 2024). Cell counts ranging from 10³–10⁶ CFU m/L deliver approximately 10⁷–10⁸ live bacteria to the infant gut daily (Boix-Amorós et al., 2016). Cross-cohort analysis reveals indicate that both infant and maternal factors play key roles in shaping this microbial population.

Vaginally delivered mother's milk contains higher Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides richness, but cesarean-section milk contains skin flora Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium enrichment (Hermansson et al., 2019). Lactation phase has a more restrictive filter: colostrum is dominated by facultative aerobes (Weissella, Leuconostoc) tolerant of oxygen tension within the mammary duct, while mature milk harbors obligate anaerobes (Veillonella, Prevotella) consistent with retrograde inoculation from the neonates mouth (Biagi et al., 2018) . Geographical and nutritional conditions also modulate the signal; rural Ethiopian milk contains certain Rhizobium spp., whereas Spanish milk is abundant with Cutibacterium and Pseudomonas (Kumar et al., 2016; Lackey et al., 2019).

Simultaneous sequencing of maternal feces, milk and infant stool suggests that 25–30 % of gut strains in infants are shared in breast milk, but identical strains occur on areolar skin as well as on oral swabs, rendering source attribution difficult (Pannaraj et al., 2019). Longitudinal monitoring of strain by shotgun metagenomics demonstrates that the majority of milk-transmitted Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus isolates transiently colonize, with detectable persistence explained by human-milk oligosaccharide (HMO) ingestion patterns (Duranti et al., 2017). From a biomarker perspective, these findings render into actionable measures. As low Bifidobacterium: Staphylococcus ratios in day-3 milk are prognostic for pre-term gut colonization delay and is associated with later necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) risk (Morrow et al., 2013). In contrast to this study, increased Lactobacillus gasseri and B. breve burdens are associated with reduced atopic eczema at 12 months (Hermansson et al., 2019). Importantly, the milk is open to intervention: probiotic supplementation during late gestation or early lactation preferentially increases cognate strains in milk and reduces mastitis incidence, demonstrating a clear pipeline from microbial read-out to therapeutic modulation (Lackey et al., 2019). Together, these patterns underscore the prognostic potential of early milk-derived microbial signatures in anticipating both gastrointestinal and immunological outcomes in infancy.

Neonatal Microbiome and Early-Life Outcomes

This section deals with the early life complications that arises from dysbiosis in the neonatal microbiome.

Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

The association between early neonatal gut microbial composition and subsequent neurodevelopmental has attracted interest among preterm populations. Several human cohort studies have identified associations between abundances of Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium and improved neurodevelopmental performance of standardized tests such as Bayley Scale (Acuña et al., 2021). Experimental studies involving animals has provided evidence that microbial signals are involved in microglial development and myelination. High quality clinical studies has also shown that broad spectrum antibiotics administered for neonates interference with microglial and overall central nervous system development (Erny et al., 2015). This suggests that specific colonization patterns favor cognitive and motor trajectories. The specific taxa contribute to neurodevelopment through multiple pathways such as short-chain fatty acids and the maturation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Conversely, an overrepresentation of facultative anaerobes and reduced microbial diversity in the first weeks of life is linked to poorer cognitive and motor outcomes (Beghetti et al., 2022). This gives the idea that microbial perturbations may significantly have enduring neurological consequences.

However, preterm infant longitudinal cohort studies has shown that broad spectrum antibiotics administered during infancy result in regiment-specific interference with developing microbiota and promotes antimicrobial resistance (Reyman et al., 2022). These shifts delay microbial maturation and enriches gut resistome fosters early multidrug resistance that may persist throughout the infancy. Notwithstanding longitudinal cohort studies involving preterm infants with Baylee-II neurodevelopment at 24 months after for extreme neonatal morbidities and other detectable morbidities indicates that the dysbiosis alone is insufficient to cause detectable cognitive impairment absent of additional stressors such as systematic inflammation, hypoxic ischemia, injuries or severe neonatal complications (Deianova et al., 2023).

Allergic and Atopic Diseases

The role of early-life microbiota in shaping risk for allergic and atopic disease is one of the most robust areas of microbiome-phenotype research. Some longitudinal studies using human subjects and multi-omics analyses have linked early microbiome changes to later atopic outcomes (Hoskinson et al., 2023) Neonatal and infant investigations have reported that lower Bifidobacterium species such as B. longum and B. breve is associated with increased risk of atopic dermatitis and other allergic phenotypes (Uchil et al., 2014). These taxa are among the earliest commensals that colonize the gut and are relevant in immune tolerance with the polysaccharides that modulate dendritic and regulatory T-cells. This depletion led to skewed immune depletion Th2 immune polarization and exaggerated inflammatory responses to dietary and environmental antigens (D’Auria et al., 2020). Notwithstanding, higher representation of S. aureus on the infant microbiome is linked to atopic dermatitis development (Lebon et al., 2009). Similar shotgun metagenomic and functional profiling further indicate that dysbiosis microbiome alters metabolic activities. This is evident in the reduced capacity to produce vitamins and short fatty-acids as well as disruptions in the pathways for the biosynthesis of folate and biotin (Das et al., 2019) . This further suggests that functional alterations in microbial metabolism could be just as useful as taxonomic differences alone in predicting risk. Epidemiological evidence indicates that early gut composition to food allergy risk. Low Bacteroides and a high Enterobacteriacae/Bacteroidaceae ratio during pregnancy are at a greater odds of pea nut sensitization by age three (adjusted OR~2.8) (Tun et al., 2021).

Early postnatal microbiome changes including Bacteroides and Akkermansia are linked to increased risk of developing a clinical food allergy. This was demonstrated in a study using fiber-deficient mice to test for Akkermansia mucinphila, which suggests that diet-microbiome interactions and microbiota composition have a causal role in regulating allergy reactions. Food allergy symptoms were shown to be exacerbated when A. muciniphila in the microbiome and fiber loss led to greater anti-commensal IgE coating and innate type-2 immune responses (Parrish et al., 2023). Collectively these responses underscore that the microbiome has influence in the development of allergic phenotypes in humans.

Malnutrition

The relationship between neonatal microbiome composition and malnutrition has been studied most rigorously in LMICs, where stunting and environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) are prevalent. Children with severe acute malnutrition in Malawi showed an immature gut microbiota compared to healthy control (Subramanian et al., 2014). When the immature microbiota was transplanted into germ-free mice, they recapitulated aspects of the of the growth failure phenotype, providing cause-to-effect relation for microbiota-mediated growth impairment. Similarly, Blanton et al. (2016) found that microbiota immaturity is highly correlated with growth failure, and that supplementing with microbiota-directed complementary foods (MDCFs) can restore microbial and metabolic maturity to a certain degree, which increases weight gain in malnourished children. Additionally, a randomized controlled trial in Bangladesh to show that MDCFs designed to promote the growth of beneficial taxa like Roseburia spp. and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii resulted in increased growth markers and better weight gain in children (Gehrig et al., 2019). According to the results, certain microbial taxa that produce butyrate are essential for maintaining gut integrity and nutritional absorption. Stunted children generally displayed an overrepresentation of Enterobacteriaceae and an underrepresentation of Faecalibacterium, which are markers of persistent inflammatory status (Stanislawski et al., 2021).

However, a South Asian cohort study by Vonaesch et al. (2018), studied those recurrent diarrheal infections significantly affect the variation and composition of the microbiome (Vonaesch et al., 2018). This indicates that dysbiosis is most likely a secondary effect rather than the cause of infection and malnutrition. This interpretation highlights how microbial ecology, malnutrition, and enteric infection interact. Recent research has confirmed that the developmental pathway of the gut microbiome from neonatal to adult-like state is a more accurate indicator of growth and nutrition than any single time-point characterization (Blanton et al., 2016; Gehrig et al., 2019). With the development of precision, microbiota-directed feeding regimens and biomarkers of microbial maturity to identify infants at risk, the discovery has fueled the new paradigm of microbiome-guided nutritional therapies.

Gut Microbiome and Sepsis Risk in Neonates

Consistent with emerging evidence on microbiota-pathogen dynamics, a study conducted by Iqba et al. (2024) in India found that Klebsiella and Pneumoniae were the pathogens in preterm neonates with bloodstream infections. The study indicated that the pathogenic profiles coincided with profound alterations in the gut microbiota, suggesting that intestinal colonization may be opportunistic. The alteration of the microbiota was strongly associated with this observation suggesting the pathogenic colonization may precede and contribute to BSI (Iqbal et al., 2025). Additionally, Ma et al (2024) investigated the gut microbiota of preterm infants with late-onset sepsis and pneumonia and found a decreased microbiota activity and overabundance of Escherichia/shigella, Streptococcus and Enterococcus. Meanwhile beneficial taxa such as Bacteroides and Akkermansia were underrepresented. Notably, the abundance of Escherichia/Shigella was predictive of late-onset sepsis risk, with an area under the curve of 0.773, highlighting it as a potential biomarker for sepsis (Ma et al., 2024). This moderate but promising discriminative performance indicates that early microbial profiling could serve as a non-invasive ability to distinguish between infants who will develop sepsis and those who will not.

Culture Negative Sepsis and Microbial Shifts

Culture negative sepsis is a condition where patients display signs and symptoms consistent with sepsis without identifiable pathogens in blood cultures, leading to different clinical characteristics and outcomes compared to culture-positive sepsis. This condition remains diagnostically challenging and often results in delayed results and treatment strategies (Klingenberg et al., 2018). Hanna et al. (2025) conducted a study involving preterm neonates with culturable sepsis, Culture negative, and asymptomatic controls. The outcome of this study indicated the alpha and beta variation of the microbiome showed no significant difference between the culture-negative sepsis and control groups. This finding suggests that subtle microbial community shifts rather than overt pathogen growth and may contribute to systemic inflammation responses in the absence of detectable bloodstream pathogens. There was a significant abundance of specific bacterial and fungal genera in stool and skin samples of the culture-negative sepsis compared to the control. These findings highlight that alteration in the microbial shifts, even in the absence of detectable pathogens play a role in the pathogenesis of the culture negative sepsis as a result of a potential translocation of microbial metabolites, cell-wall components or low-biomass microbial fragments undetectable by standard diagnostics (Stewart et al., 2017). The identification of specific microbial shifts in culture-negative sepsis cases suggests that microbiome profiling could serve as a diagnostic tool where conventional methods fail which can potentially guide earlier and more targeted interventions.

Urinary Tract Infections (UTI)

Despite the pediatric urinary microbiome thought as sterile, recent studies have shown microbial community (Kelly et al., 2024). UTI’s have been linked with early-life dysbiosis of the gut microbiome (Levanova et al., 2021). A study by Heida et al. (2021) observed that the initial four weeks of neonatal life undergoes an intense gut microbiome transition mostly from a Staphylococci dominated microbiome to Enterobacteriaceae dominated. This shift is an indicative of microbial immaturity and contributes to an increased susceptibility to pathogenic infections. Similar studies suggests that children with UTI exhibit distinct gut microbiome characterized by pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, and Enterobacter species (Srivastava et al., 2025). However, control populations show greater abundance of commensal genera such as Bacteroides, lactobacillus, and Pervetolla. This suggests a protective barrier against uropathogen colonization by forming stable biofilms and adhering mucosal surfaces (Levanova et al., 2021; A. Srivastava et al., 2025). However, the control populations of the study showed colonies of Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Prevotella. This suggests that healthy gut colonization provides a protective barrier against uropathogen establishment. Despite these findings, the causal relationship between gut dysbiosis and UTI onset remain incompletely understood. Some studies suggest that gut alterations are more likely transient and precede infection episodes rather than being consistently present at baseline (Srivastava et al., 2025).

Furthermore, the urobiome of females demonstrated greater diversity, with numerous species considerably more prevalent in females when compared to males. From this study, the urobiome consists of including those from the genera Anaerococcus, Prevotella, and Schaalia. Urobiome diversity increases with age, significantly in males. Also, comparison of children with a history of 3+ UTIs infection history has a diverse urobiome (Kelly et al., 2024). According to a study that used 16S rRNA sequencing to compare the control and experimental groups, the dominant uropathogens were Lactobacillus and Prevotella in the control groups and Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the experimental groups. According to the same study, there was no significant difference in urobiome alpha diversity between infants born vaginally and those born via cesarean section, nor was diversity impacted by previous exposure to antibiotics (Reasoner et al., 2023). These results confirm that a significant cause of pediatric infections is dysbiosis characterized by the proliferation of Proteobacteria and the loss of commensals like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. Although the gut and urine microbiomes of newborns are still poorly understood, new research indicates that they may be predictive of infection risk. The development of microbiome-based indicators and prompt therapies to prevent future (Srivastava et al., 2025).

Emerging evidence indicates that certain microbial community alterations across maternal and neonatal body surfaces are uniformly associated with perinatal adverse outcomes.

Table 1 shows model microbial taxa and their presumed mechanistic associations with key pregnancy and neonatal diseases. The patterns suggest that the protective genera such as

Lactobacillus crispatus,

Bifidobacterium,

Faecalibacterium, and

Akkermansia are often decreased under pathological conditions, while pathobiont enrichment by

Gardnerella,

Prevotella,

Escherichia–

Shigella, and

Enterobacteriaceae signifies increased disease risk. Combined, these taxa represent the potential biomarker candidates for predictive diagnostics and mechanistic studies in maternal–neonatal health.

Integration of Omics for Precision Medicine

The integration of multi-omics data has emerged as cornerstone of precision medicine with its fields ranging from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and microbiomics. This is due to the synthesis of data from across diverse biological layers and can lead to more accurate diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutic strategies. The recent advancements have highlighted the transforming power of multi-omics in clinical cases. For instances, a study by Abdelaziz et.al (2024) provided a multi-omics analysis pipeline, emphasizing the relevance of integrating data from different omics technologies using computational methods. The approach has been integrated in to survival analysis, cancer classification and biomarker identification. Similarly, a review by Archarya & Mukhopadhyay (2024) focused on the integration in precision data in precision oncology. The outcome of this was to emphasize the machine-learning integration of distinct omics datasets provides a powerful framework for clinical application and informing personalized treatment.

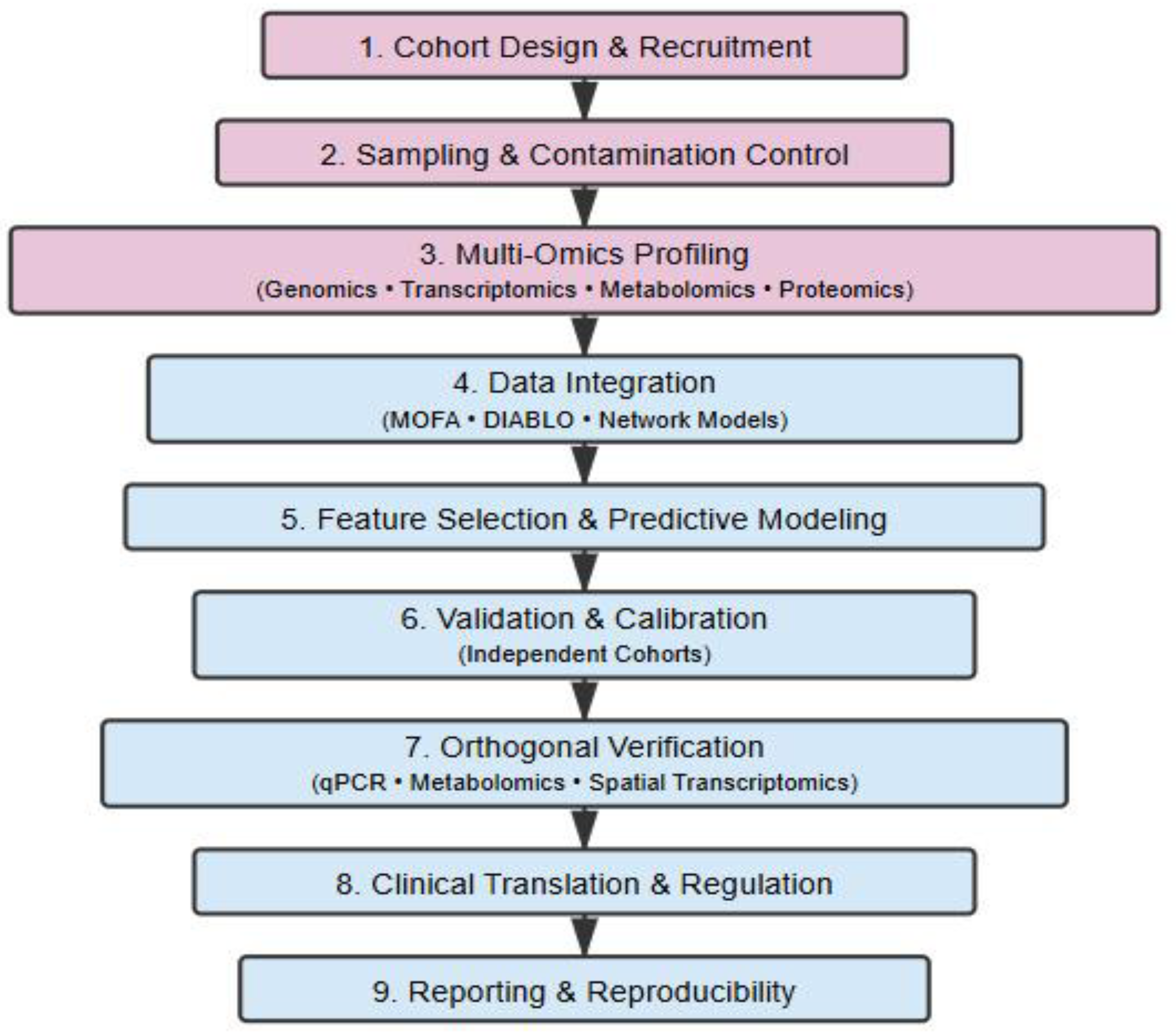

Diagnostic Pathway

The development of an actionable microbiome signature for maternal and neonatal outcome requires an open end to-end diagnostic pathway to deployable and validated models. The following pathway integrates current advances in multi-omics design, data management and translational science. For the strongest data basis, prospective, well-phenotyped pregnant cohorts with longitudinal sampling from the first trimester through early infancy are used. Bias is reduced when endpoints, such as spontaneous preterm birth, preeclampsia, or newborn infection, are defined prior to participation. It is essential to standardize sampling locations, timing, and storage conditions because even minor pre-analytic variations might cause microbial and metabolic signals to be distorted (Boudar et al., 2022).

Placental and amniotic tissue is extremely low biomass and easily swamped by reagent or environmental contaminant. To curb this negative and process controls with study samples and prevalence-based filtering is essential to discriminate genuine biological signals from artifacts (Kuperman et al., 2019; Panzer et al., 2023).

Additionally, high resolution needs to combine 16S and shotgun metagenomics, meta-transcriptomics and host derived proteomics. This integration must be done across layers to synchronize collection timepoints and harmonized aliquoting and comparability is maintained by normalization and batch corrections (Sherwani et al, 2025).

The modelling frameworks such as DIABLO, MOFA/MOFA+, or network-based latent factor models jointly capture a modality-specific variation between the different omics layers which will improve predictive performance. The inclusion of statistical analysis with immunological or metabolic pathways enhances interpretation (Singh et al, 2019)

Again, model training, validation, and calibration of predictive models must be internally and externally done in independent cohorts and varied settings. Tests such as the Nested cross-validation and reporting of discrimination (AUC), calibration (Brier score), and decision-analytic metrics ensure clinical rigor (Tarca et al., 2021).

Candidate biomarkers must be verified in independent assays e.g., metabolite quantitation, targeted qPCR, or spatial transcriptomics to provide mechanistic link between microbe, metabolite, and host response (Bautista et al., 2025).

Open reporting of pipelines, parameter settings, and raw data deposition following STROBE-metagenomics or MIxS guidelines enables reproducibility and meta-analysis (Boudar et al., 2022).

To visualize the sequential steps linking microbiome research to clinical application,

Figure 1 illustrates the diagnostic pathway for multi-omics biomarker development in maternal and neonatal health.

Clinical Applications and Challenges

Multi-omics is an integrative approach that incorporates transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics, phenomics, genomics and epigenomics into examining diseases. The integration of microbiome data with other omics, such as proteome, inflammatory mediators, and the metabolome to address the gap in understanding the functional interactions between bacteria and humans (Neu & Stewart, 2025). Multi-omics studies in neonates are particularly important due to the complex of human development. While traditional microbiome studies provide insights into microbial relative abundance and diversity. The large data sets involved generated require complex analysis and interpretation, especially metagenomics. The integration of multi omics data sets while maintaining biological context is a significant hurdle that has to be addressed for robust and reproducible findings (Neu & Stewart, 2025).

The integration of multi-omics is driven by the new technologies such as the Next generational sequencing and highly advanced microbial sequencing. These novel technologies make it possible to explore the host-microbiome interactions at various omics levels. These technologies are necessary to understand the complex interactions between gut microbiota and the host’s physiological status (Lu et al., 2025). For instance, studies that utilized multi-omics approach has shown that the gut microbiota is altered in when the host is diseased (Huang et al., 2024). Similarly, metagenomics and metabolomics has shown that the gut microbiota is able to metabolize drugs (Jarmusch et al., 2020). Transcriptome analyses have shown the gut microbiota can influence host gene expression (Richards et al., 2019).

Challenges in Clinical Translation

Neonatal microbiome studies are particularly complex due to the dynamic nature. Factors such as the antibiotic exposure, feeding practices, mode of delivery and environmental exposures significantly influence microbial colonization and development (Neu & Stewart, 2025). These shifts pose significant challenge in establishing stable biomarkers for clinical implications. As such some studies indicate that the microbial colonization patterns differ from those in full-term infants affecting health outcomes. Furthermore, the influence of maternal factors on the neonatal microbiome remains an area requiring further inspection.

Studies also generate vast amount of data that needs requiring bioinformatics and statistical analysis (Abdelaziz et al., 2024). Neonatal microbiome studies generate vast amount of high-dimensional data, including DNA sequence, metabolomics and transcriptomics. Additionally, the integration of multi-omics adds another layer of complexity which necessitates the development of robust computational frameworks.

There are challenges in designing the adequately powered clinical trials and ensuring reproducibility of findings. Moreover, the rapid developmental changes in neonates require careful planning of study design and measure outcomes. This will ensure adequate sample sizes and statistical power to detect meaningful associations between microbiome profiles and physiological statuses.

There are also regulatory hurdles and the standardization of methodologies for microbiome analysis in diagnostic testing (FDA, 2018). This is due to the microbiome-based diagnostic regulatory environment is continually developing. The FDA has recently rolled-back certain regulations on lab-developed test in the United States. In Europe, the lack of clear guidance on regulation of microbiome testing services has led to uncertainty regarding their intended use and regulatory classification. In addition, the absence of standardized methods for sample collection, processing, and analysis also leads to variability in study results.

Conclusions

Within a decade, maternal and neonatal microbiome has evolved from descriptive to predictive models. As demonstrated through this mini review, the perinatal microbiome plays a critical review role in immune regulation, metabolic health and the development of pregnancy-related outcomes, such as preterm birth, preeclampsia and neonatal sepsis. Microbial imbalances have been implicated in adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes indicating the microbiome-based biomarkers in early diagnosis.

Integration of microbiome signatures as prognostic biomarkers for neonatal and maternal health is a promising future prospect in precision medicine. As depicted in this review, the perinatal microbiome plays a core role in immune regulation, metabolic health, and complication development during pregnancy, such as preterm birth, preeclampsia, and neonatal sepsis. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, has been implicated in several adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, underlining the potential of microbiome-based biomarkers to improve early detection and personalized treatment. Despite this, challenges persist, including the dynamic nature of the neonatal microbiome, the complexity of information arising from multi-omics profiling, and the need for highly powered clinical studies for reproducibility and validation. Furthermore, the effect of maternal influences on the neonatal microbiome is still to be investigated, and regulatory challenges are a major hurdle to the translational applications of microbiome-based diagnostics. Despite these challenges, the growing evidence base and improvements in microbiome profiling technologies suggest that the incorporation of microbiome signatures into clinical practice has the potential to revolutionize maternal and neonatal health care into more individualized and efficient approaches to health care.

Author Contributions

Philip Boakye Bonsu, Conceptualization, writing–original draft, Writing, Project administration; Kwadwo Fosu, Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Supervision; Samuel Badu Nyarko, Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Supervision.

Funding

No external funding was obtained for this project.

References

- Azad, M.B.; Konya, T.; Persaud, R.R.; Guttman, D.S.; Chari, R.S.; Field, C.J.; Sears, M.R.; Mandhane, P.J.; Turvey, S.E.; Subbarao, P.; Becker, A.B.; Scott, J.A.; Kozyrskyj, A.L. Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2016, 123, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.C.; Castagna, V.P.; Sela, DA..; Hillard, M.A.; Lindberg, S.; Mantis, N.J.; Seppo, A.E.; Järvinen, K.M. Gut microbiome and breast-feeding: implications for early immune development. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 150, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Forster, S.C.; Tsaliki, E.; Vervier, K.; Strang, A.; Simpson, N.; Kumar, N.; Stares, M.D.; Rodger, A.; Brocklehurst, P.; Field, N.; Lawley, T.D. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature 2019, 574, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.; Firek, B.A.; Miller, C.S.; Sharon, I.; Thomas, B.C.; Baker, R.; Morowitz, M.J.; Banfield, J.F. Microbes in the neonatal intensive care unit resemble those found in the gut of premature infants. Microbiome 2 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, K.; Ma, J.; Antony, K. M.; Ganu, R.; Petrosino, J.; Versalovic, J. The Placenta Harbors a Unique Microbiome. HHS Public Access 2016, 6(237), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, E. H.; Ismail, R.; Mabrouk, M. S.; Amin, E. Multi-omics data integration and analysis pipeline for precision medicine: Systematic review. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2024, 113, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Mukhopadhyay, A. A comprehensive review of machine learning techniques for multi-omics data integration: Challenges and applications in precision oncology. Briefings in Functional Genomics 2024, 23(5), 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, I.; Cerdó, T.; Ruiz, A.; Torres-espínola, F. J.; López-moreno, A.; Aguilera, M.; Suárez, A.; Campoy, C. Infant gut microbiota associated with fine motor skills. Nutrients 2021, 13(5), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Fatima, F.; Farooq, H. A.; Ahmed, U.; Fatima, F.; Farooq, H. A. Maternal and child health DYSBIOSIS AS A GLOBAL HEALTH CHALLENGE 2025, 93(8), 1–8.

- Barrientos, G.; Ronchi, F.; Conrad, M. L. Nutrition during pregnancy: Influence on the gut microbiome and fetal development. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2024, 91(1), e13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, E.; Aceti, A.; Quercia, S.; Beghetti, I.; Rampelli, S.; Turroni, S.; Soverini, M.; Zambrini, A. V.; Faldella, G.; Candela, M.; Corvaglia, L.; Brigidi, P. Microbial Community Dynamics in Mother’s Milk and Infants Mouth and Gut in Moderately Preterm Infants 2018, 9(October), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Blanton, L. V.; Charbonneau, M. R.; Salih, T.; Barratt, M. J.; Venkatesh, S.; Ilkaveya, O.; Subramanian, S.; Manary, M. J.; Trehan, I.; Jorgensen, J. M.; Fan, Y.; Henrissat, B.; Leyn, S. A.; Rodionov, D. A.; Osterman, A. L. Kenneth M. Maleta Christopher B. Newgard3, 4, 5, 6, Per Ashorn11, 16, Kathryn G. Dewey10, and Jeffrey Gordon1, 2, & 1Center Gut bacteria that rescue growth impairments transmitted by immature microbiota from undernourished children. HHS Public Access 2016, 351(6275), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Amorós, A.; Collado, M. C.; Mira, A. Relationship between milk microbiota, bacterial load, macronutrients, and human cells during lactation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7(APR), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, M.; Amabebe, E.; Kulkarni, N. S.; Papageorgiou, M. D.; Walker, H.; Wyles, M. D.; Anumba, D. O. Vaginal host immune-microbiome-metabolite interactions associated with spontaneous preterm birth in a predominantly white cohort. Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2025, 11(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. diao; Ke, C. W.; Deng, X.; Jiang, S.; Liang, W.; Ke, B. X.; Li, B.; Tan, H.; Liu, M. Brucellosis in Guangdong Province, people’s republic of China, 2005-2010. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2013, 19(5), 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Babaei, P.; Nielsen, J. Metagenomic analysis of microbe-mediated vitamin metabolism in the human gut microbiome. BMC Genomics 2019, 20(1), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, E.; Peroni, D. G.; Sartorio, M. U. A.; Verduci, E.; Zuccotti, G. V.; Venter, C. The Role of Diet Diversity and Diet Indices on Allergy Outcomes. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2020, 8(September), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goffau, M. C.; Lager, S.; Sovio, U.; Gaccioli, F.; Cook, E.; Peacock, S. J.; Parkhill, J.; Charnock-Jones, D. S.; Smith, G. C. S. Author Correction: Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential pathogens (Nature, (2019), 572, 7769, (329-334), 10.1038/s41586-019-1451-5). Nature 2019, 574(7778), E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deianova, N.; de Boer, N. K.; Aoulad Ahajan, H.; Verbeek, C.; Aarnoudse-Moens, C. S. H.; Leemhuis, A. G.; van Weissenbruch, M. M.; van Kaam, A. H.; Vijbrief, D. C.; Hulzebos, C. V.; Giezen, A.; Cossey, V.; de Boode, W. P.; de Jonge, W. J.; Benninga, M. A.; Niemarkt, H. J.; de Meij, T. G. J. Duration of Neonatal Antibiotic Exposure in Preterm Infants in Association with Health and Developmental Outcomes in Early Childhood. Antibiotics 2023, 12(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowska-Pali, A.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Chrustek, A.; Olszewska-Słonina, D.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E.; Socha, M. W. Human Milk Microbiome-A Review of Scientific Reports. Nutrients 2024, 16(10), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, R. M.; Harris, K.; Kamiza, S.; Harjunmaa, U.; Ashorn, U.; Nkhoma, M.; Dewey, K. G.; Maleta, K.; Ashorn, P.; Klein, N. Bacterial communities found in placental tissues are associated with severe chorioamnionitis and adverse birth outcomes; 2017; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Duranti, S.; Lugli, G. A.; Mancabelli, L.; Armanini, F.; Turroni, F.; James, K.; Ferretti, P.; Gorfer, V.; Ferrario, C.; Milani, C.; Mangifesta, M.; Anzalone, R.; Zolfo, M.; Viappiani, A.; Pasolli, E.; Bariletti, I.; Canto, R.; Clementi, R.; Cologna, M.; Ventura, M. Maternal inheritance of bifidobacterial communities and bifidophages in infants through vertical transmission; 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, R.-M.; Roşu, O. A.; Profir, M.; Pavelescu, L. A.; Creţoiu, S. M.; Gaspar, B. S. Correlations Between Gut Microbiota Composition, Medical Nutrition Therapy, and Insulin Resistance in Pregnancy—A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(3), 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; De Angelis, A. L. H.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; Schwierzeck, V.; Utermöhlen, O.; Chun, E.; Garrett, W. S.; Mccoy, K. D.; Diefenbach, A.; Staeheli, P.; Stecher, B.; Amit, I.; Prinz, M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nature Neuroscience 2015, 18(7), 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, S.; Hemmatabadi, M.; Ejtahed, H. S.; Shirzad, N.; Larijani, B. Microbiome alterations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and their offspring: A systematic review. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13(December), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs). Blueprint for Breakthroughs—Charting the Course for Precision Medicine 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R.; Kitt, J.; Leeson, P.; Aye, C. Y. L.; Lewandowski, A. J. Preeclampsia: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Management, and the Cardiovascular Impact on the Offspring. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 8(10), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrig, J. L.; Venkatesh, S.; Chang, H.; Hibberd, M. C.; Kung, V. L.; Cheng, J.; Chen, R. Y.; Subramanian, S.; Cowardin, C. A.; Meier, M. F.; Donnell, D. O.; Talcott, M.; Spears, L. D.; Semenkovich, C. F.; Henrissat, B.; Giannone, R. J.; Hettich, R. L.; Ilkayeva, O.; Muehlbauer, M.; Gordon, J. I. Effects of microbiota-directed foods in gnotobiotic animals and undernourished children 2019, 139. [CrossRef]

- Gerede, A.; Nikolettos, K.; Vavoulidis, E.; Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Petousis, S.; Giourga, M.; Fotinopoulos, P.; Salagianni, M.; Stavros, S.; Dinas, K.; Nikolettos, N.; Domali, E. Vaginal Microbiome and Pregnancy Complications: A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudnadottir, U.; Debelius, J. W.; Du, J.; Hugerth, L. W.; Danielsson, H.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; Fransson, E.; Brusselaers, N. The vaginal microbiome and the risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Chan, S. Y.; Toh, R.; Low, J. M.; Ming, I.; Liu, Z.; Lim, S. L.; Lee, L. Y.; Swarup, S. Gestational diabetes - related gut microbiome dysbiosis is not influenced by different Asian ethnicities and dietary interventions: A pilot study. Scientific Reports 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Huang, S.; Ross, M.; Reyes, A.; Perera, D.; Surathu, A.; Javornik Cregeen, S.; Hagan, J.; Pammi, M. Microbiome Signatures and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Culture-Negative Neonatal Sepsis. Applied Microbiology 2025, 5(3), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, F. H.; Kooi, E. M. W.; Wagner, J.; Nguyen, T.; Hulscher, J. B. F.; Van Zoonen, A. G. J. F.; Bos, A. F.; Harmsen, H. J. M.; De Goffau, M. C. Weight shapes the intestinal microbiome in preterm infants: Results of a prospective observational study; 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansson, H.; Kumar, H.; Collado, M. C.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E.; Rautava, S. Breast milk microbiota is shaped by mode of delivery and intrapartum antibiotic exposure. Frontiers in Nutrition 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskinson, C.; Dai, D. L. Y.; Del Bel, K. L.; Becker, A. B.; Moraes, T. J.; Mandhane, P. J.; Finlay, B. B.; Simons, E.; Kozyrskyj, A. L.; Azad, M. B.; Subbarao, P.; Petersen, C.; Turvey, S. E. Delayed gut microbiota maturation in the first year of life is a hallmark of pediatric allergic disease. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Liang, X.; Bao, H.; Ma, G.; Tang, X.; Luo, H.; Xiao, X. Multi-omics analysis reveals the associations between altered gut microbiota, metabolites, and cytokines during pregnancy. mSystems 2024, 9(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.; Siva, N.; Shenoy, P. A.; Lewis, L. E. S.; Purkayastha, J.; Eshwara, V. K. Gut Pathogen Colonization: A Risk Factor to Bloodstream Infections in Preterm Neonates Admitted in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit-A Prospective Cohort Study. Neonatology 2025, 122(2), 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmusch, A. K.; Vrbanac, A.; Momper, J. D.; Ma, J. D.; Alhaja, M.; Liyanage, M.; Knight, R.; Dorrestein, P. C.; Tsunoda, S. M. Enhanced Characterization of Drug Metabolism and the Influence of the Intestinal Microbiome: A Pharmacokinetic, Microbiome, and Untargeted Metabolomics Study. Clinical and Translational Science 2020, 13(5), 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, S.; Hammad Altaq, H.; Abdo, T. Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: What Have We Learned in the Last Two Decades? Microorganisms 2023, 11(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. S.; Dahl, E. M.; Jeries, L. M.; Sysoeva, T. A.; Karstens, L. Characterization of pediatric urinary microbiome at species-level resolution indicates variation due to sex, age, and urologic history. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2024, 20(5), 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, C.; Kornelisse, R. F.; Buonocore, G.; Maier, R. F.; Stocker, M. Culture-Negative Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis—At the Crossroad Between Efficient Sepsis Care and Antimicrobial Stewardship. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2018, 6, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, O.; Goodrich, J. K.; Cullender, T. C.; Spor, A.; Laitinen, K.; Bäckhed, H. K.; Gonzalez, A.; Werner, J. J.; Angenent, L. T.; Knight, R.; Bäckhed, F.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S.; Ley, R. E. During pregnancy 2013, 150(3), 470–480. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; du Toit, E.; Kulkarni, A.; Aakko, J.; Linderborg, K. M.; Zhang, Y.; Nicol, M. P.; Isolauri, E.; Yang, B.; Collado, M. C.; Salminen, S. Distinct patterns in human milk microbiota and fatty acid profiles across specific geographic locations. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7(OCT). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuperman, A.; Zimmerman, A.; Hamadia, S.; Ziv, O.; Gurevich, V.; Fichtman, B.; Gavert, N.; Straussman, R.; Rechnitzer, H.; Barzilay, M.; Shvalb, S.; Bornstein, J.; Ben-Shachar, I.; Yagel, S.; Haviv, I.; Koren, O. Deep microbial analysis of multiple placentas shows no evidence for a placental microbiome. BJOG 2019, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, K. A.; Williams, J. E.; Meehan, C. L.; Zachek, J. A.; Benda, E. D.; Price, W. J.; Foster, J. A.; Sellen, D. W.; Kamau-Mbuthia, E. W.; Kamundia, E. W.; Mbugua, S.; Moore, S. E.; Prentice, A. M.; D. G., K; Kvist, L. J.; Otoo, G. E.; García-Carral, C.; Jiménez, E.; Ruiz, L.; McGuire, M. K. What’s normal? Microbiomes in human milk and infant feces are related to each other but vary geographically: The inspire study. Frontiers in Nutrition 2019, 6(April). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebon, A.; Labout, J. A. M.; Verbrugh, H. A.; Jaddoe, V. W. V.; Hofman, A.; van Wamel, W. J. B.; van Belkum, A.; Moll, H. A. Role of Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization in Atopic Dermatitis in Infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009, 163(4), 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levanova, L. A.; Markovskaya, A. A.; Otdushkina, Y. L.; Zakharova, Yu. V. Gut microbiota and urinary tract infections in children. Fundamental and Clinical Medicine 2021, 6(2), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, B.; Luo, J.; He, C.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Fan, K. L.; Fang, B.; Wan, C. Multi-omics decodes host-specific and environmental microbiome interactions in sepsis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Dong, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Deng, F.; Chen, J.; Lin, B.; Khan, B. A.; Liu, W.; Hou, K. Relationship between gut microbiota and the pathogenesis of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review; 2024; Volume May, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Janiszewska, O.; Bialic, K.; Faryniak, A.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D. A Review of Modulation of Gut Microbiota to Mitigate Gestational Diabetes: Implications for Maternal and Child Health. MSM 2025, 31(e948897), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, A. L.; Lagomarcino, A. J.; Schibler, K. R.; Taft, D. H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, B.; Altaye, M.; Wagner, M.; Gevers, D.; Ward, D. V.; Kennedy, M. A.; Huttenhower, C.; Newburg, D. S. Early microbial and metabolomic signatures predict later onset of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Microbiome 2013, 1(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakshine, V. S.; Jogdand, S. D. A Comprehensive Review of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Impacts on Maternal Health, Fetal Development, Childhood Outcomes, and Long-Term Treatment Strategies. Cureus 2023, 15(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, J.; Stewart, C. J. Neonatal microbiome in the multiomics era: Development and its impact on long-term health. Pediatric Research 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, D.; Tan, J.; Macia, L.; Nanan, R. Breastfeeding is associated with enhanced intestinal gluconeogenesis in infants. BMC Medicine 2024, 22(1), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannaraj, P. S.; Li, F.; Cerini, C.; Bender, J. M.; Yang, S.; Rollie, A.; Adisetiyo, H.; Zabih, S.; Lincez, P. J.; Bittinger, K.; Bailey, A.; Bushman, F. D.; Sleasman, J. W.; Aldrovandi, G. M. Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome 2019, 90095(7), 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Panzer, J. J.; Romero, R.; Greenberg, J. M.; Winters, A. D.; Galaz, J.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Theis, K. R. Is there a placental microbiota? A critical review and re-analysis of published placental microbiota datasets. BMC Microbiology 2023, 23(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.; Boudaud, M.; Grant, E. T.; Willieme, S.; Neumann, M.; Wolter, M.; Craig, S. Z.; De Sciscio, A.; Cosma, A.; Hunewald, O.; Ollert, M.; Desai, M. S. Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates food allergy in fibre-deprived mice. Nature Microbiology 2023, 8(10), 1863–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, P.; Dhakal, S.; Dozois, C. M. The Diversity of Escherichia coli Pathotypes and Vaccination Strategies against This Versatile Bacterial Pathogen. Microorganisms 2023, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reasoner, S. A.; Flores, V.; Van Horn, G.; Morales, G.; Peard, L. M.; Abelson, B.; Manuel, C.; Lee, J.; Baker, B.; Williams, T.; Schmitz, J. E.; Clayton, D. B.; Hadjifrangiskou, M. Survey of the infant male urobiome and genomic analysis of Actinotignum spp. Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2023, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyman, M.; van Houten, M. A.; Watson, R. L.; Chu, M. L. J. N.; Arp, K.; de Waal, W. J.; Schiering, I.; Plötz, F. B.; Willems, R. J. L.; van Schaik, W.; Sanders, E. A. M.; Bogaert, D. Effects of early-life antibiotics on the developing infant gut microbiome and resistome: A randomized trial. Nature Communications 2022, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A. L.; Muehlbauer, A. L.; Alazizi, A.; Burns, M. B.; Findley, A.; Messina, F.; Gould, T. J.; Cascardo, C.; Pique-Regi, R.; Blekhman, R.; Luca, F. Gut Microbiota Has a Widespread and Modifiable Effect on Host Gene Regulation. mSystems 2019, 4(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Elhaj, D. A. I.; Ibrahim, I.; Abdullahi, H.; Al Khodor, S. Maternal microbiota and gestational diabetes: Impact on infant health. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Shete, O.; Gulia, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Ghosh, T. S.; Ahuja, V.; Anand, S. Role of Gut and Urinary Microbiome in Children with Urinary Tract Infections: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Kumar, R. Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules; 2024; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Tang, D.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Xiong, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Zeng, S.; Wei, S. The impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on maternal-fetal pregnancy outcomes and fetal growth: A multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2025, 13(May), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Huq, S.; Yatsunenko, T.; Haque, R.; Alam, M. A.; Benezra, A.; Destefano, J.; Meier, M. F.; Muegge, B. D.; Barratt, M. J.; Vanarendonk, L. G.; Zhang, Q.; Province, A.; Petri, W. A.; Ahmed, T.; Gordon, J. I. Persistent Gut Microbiota Immaturity in Malnourished Bangladeshi Children. HHS Public Access 2014, 510(7505), 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, E. L.; Kallapur, S. G.; Gisslen, T.; Lambers, D. S.; Chougnet, C. A.; Stephenson, S.; Jobe, A. H.; Knox, C. L. Placental Infection With Ureaplasma species Is Associated With Histologic Chorioamnionitis and Adverse Outcomes in Moderately Preterm and Late-Preterm Infants. 213 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yao, G.; Jin, J.; Zhang, T.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Intestinal flora and pregnancy complications: Current insights and future prospects. iMeta 2024, 3(2), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tun, H. M.; Peng, Y.; Chen, B.; Konya, T. B.; Morales-Lizcano, N. P.; Chari, R.; Field, C. J.; Guttman, D. S.; Becker, A. B.; Mandhane, P. J.; Moraes, T. J.; Sears, M. R.; Turvey, S. E.; Subbarao, P.; Simons, E.; Scott, J. A.; Kozyrskyj, A. L. Ethnicity Associations With Food Sensitization Are Mediated by Gut Microbiota Development in the First Year of Life. Gastroenterology 2021, 161(1), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turjeman, S.; Collado, M. C.; Koren, O. ScienceDirect The gut microbiome in pregnancy and pregnancy complications. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research 2021, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchil, R. R.; Kohli, Gur. sinGh; KateKhaye, V. M.; SwaMi, onKaR c. Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2014, 8(7), 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonaesch, P.; Morien, E.; Andrianonimiadana, L.; Sanke, H.; Mbecko, J. R.; Huus, K. E.; Naharimanananirina, T.; Gondje, B. P.; Nigatoloum, S. N.; Vondo, S. S.; Kaleb Kandou, J. E.; Randremanana, R.; Rakotondrainipiana, M.; Mazel, F.; Djorie, S. G.; Gody, J. C.; Finlay, B. B.; Rubbo, P. A.; Parfrey, L. W.; Sansonetti, P. J. Stunted childhood growth is associated with decompartmentalization of the gastrointestinal tract and overgrowth of oropharyngeal taxa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2018, 115(36), E8489–E8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wen, R.; Huang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, K.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, W.; Ou, D.; Bai, H. Gut microbiota composition in early pregnancy as a diagnostic tool for gestational diabetes mellitus. Microbiology Spectrum 2025, 13(8), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).