Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Group Characteristics

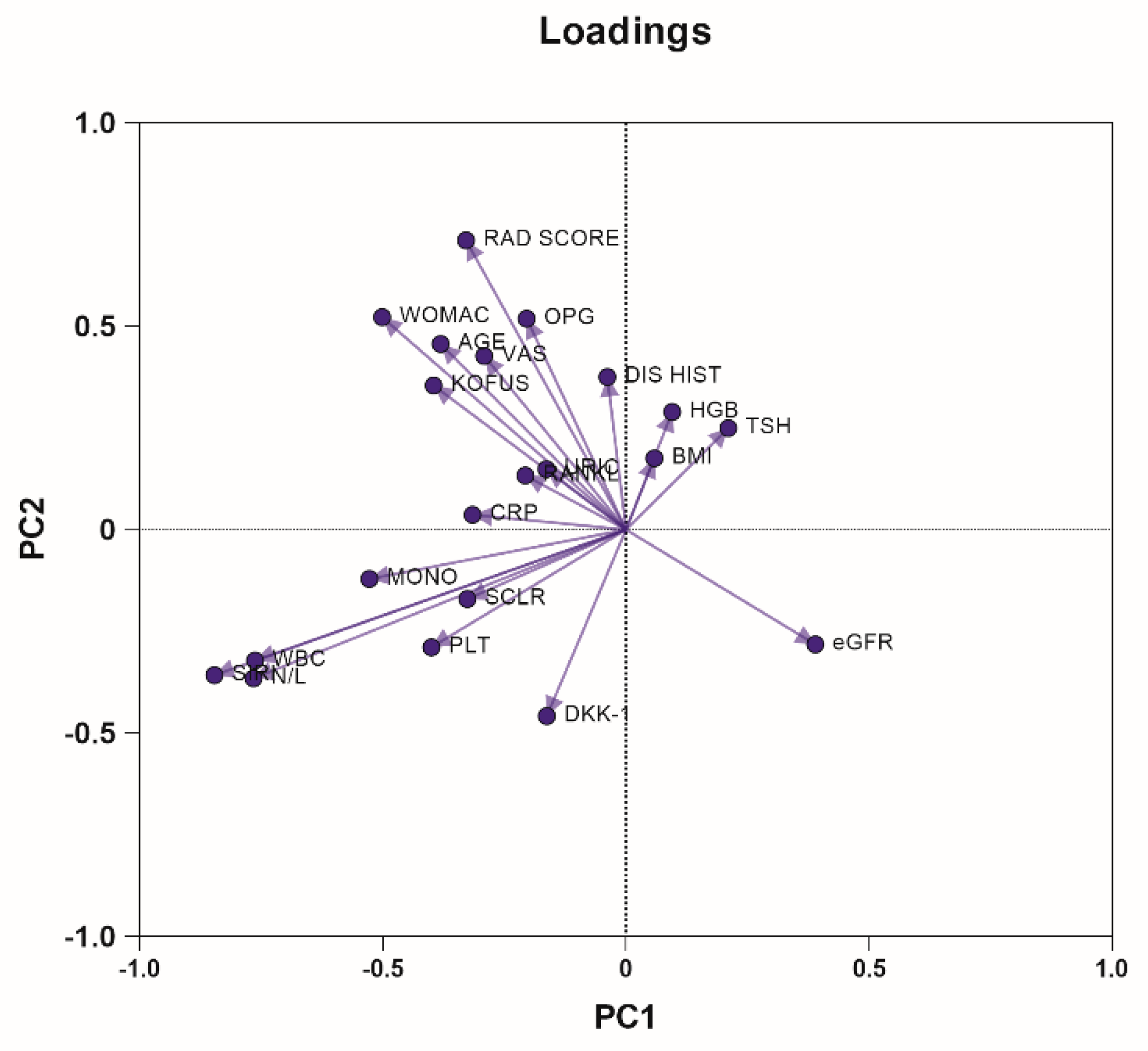

2.2. Principal Component Analysis

2.3. Correlations of the K-L, WOMAC, and KOFUS Scores

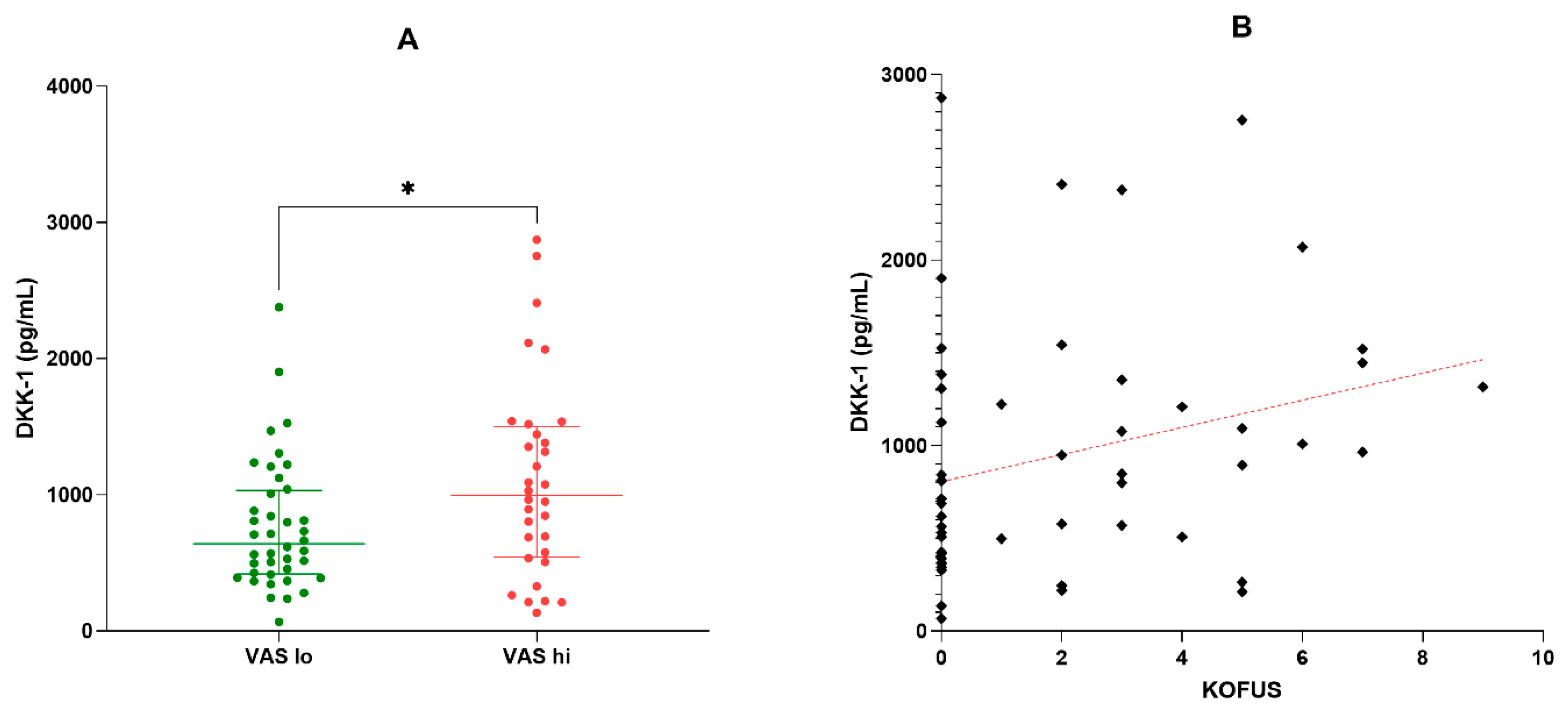

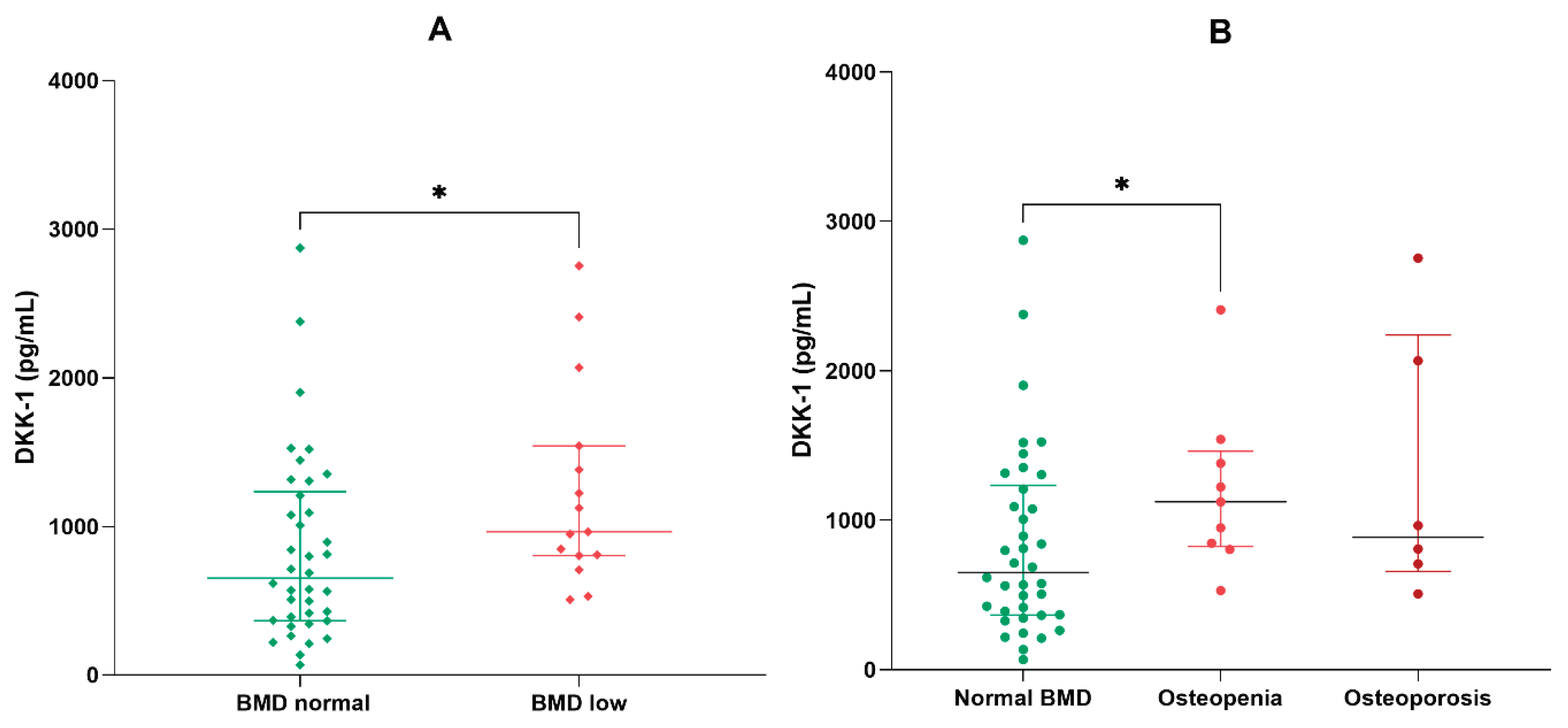

2.4. Analysis of DKK-1 in the Non-Obese and Low Bone Mineral Density Subgroups

3.5. Simple and Multiple Linear Regression

3. Discussion

3.1. Correlations of Radiological Grade, Pain and Low Osteoarthritis Flare-up Scores

3.2. The Influence of an Altered Body Mass Index on Osteoarthritis Pathways

3.3. The Influence of Underlying Altered Bone Metabolism on Markers of Osteoarthritis

3.4. Serum DKK-1 Changes and Comparisons with Other Clinical Research Findings

3.5. Osteoprotegerin and RANKL

3.6. Serum Sclerostin

3.7. Relevance of the Study

3.8. Interactions and Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Patient Cohort

4.2. Laboratory Testing

4.3. Determination of Disease Activity Biomarkers

4.4. Radiographic Examination

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAMTS | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin motifs |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| DKK-1 | Dickkopf-related protein 1 |

| DMOADs | Disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| KOFUS | Knee Osteoarthritis Flare-up score |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand |

| SOST | Sclerostin |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| WOMAC score | Western Ontario and McMaster University score |

References

- Leszczynski, P.; Lisinski, P.; Kwiatkowska, B.; Blicharski, T.; Drobnik, J.; Pawlak-Bus, K. Clinical expert statement on osteoarthritis: diagnosis and therapeutic choices. REUMATOLOGIA 2025, 63(2), 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, M.; Dasa, V.; Spitzer, A. Knee osteoarthritis: disease burden, available treatments, and emerging options. THERAPEUTIC ADVANCES IN MUSCULOSKELETAL DISEASE 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeser, R.; Goldring, S.; Scanzello, C.; Goldring, M. Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ. ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATISM 2012, 64(6), 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H; Siwiec, RM. Knee Osteoarthritis; Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dieppe, P. Inflammation in Osteoarthritis. RHEUMATOLOGY AND REHABILITATION 1978, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huskisson, E.; Dieppe, P.; Tucker, A.; Cannell, L. Another look at osteoarthritis. ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES 1979, 38(5), 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, L.; Aigner, T. Articular cartilage and changes in arthritis—An introduction: Cell biology of osteoarthritis. ARTHRITIS RESEARCH 2001, 3(2), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, T; Ryu, J; Saito, S; Sakamoto, A. Effects of growth factors and cytokines on proteoglycan and collagen synthesis by chondrocytes in guinea pigs with spontaneous osteoarthritis. MODERN RHEUMATOLOGY 2000, 10(1), 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, A.; Hui, W.; Cawston, T.; Richards, C. Adenoviral gene transfer of interleukin-1 in combination with oncostatin M induces significant joint damage in a murine model. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PATHOLOGY 2003, 162(6), 1975–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.; Grol, M.; Ruan, M.; Dawson, B.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, M.; Song, I.; Jayaram, P.; Cela, R.; Gannon, F.; et al. Combinatorial Prg4 and Il-1ra Gene Therapy Protects Against Hyperalgesia and Cartilage Degeneration in Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis. HUMAN GENE THERAPY 2019, 30(2), 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Triantafillou, S.; Parker, A.; Youssef, P.; Coleman, M. Synovial membrane inflammation and cytokine production in patients with early osteoarthritis. JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY 1997, 24(2), 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange-Brokaar, B.; Ioan-Facsinay, A.; van Osch, G.; Zuurmond, A.; Schoones, J.; Toes, R.; Huizinga, T.; Kloppenburg, M. Synovial inflammation, immune cells and their cytokines in osteoarthritis: a review. OSTEOARTHRITIS AND CARTILAGE 2012, 20(12), 1484–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhou, X.; Scherr, T.; Yang, Y.; Price, C.; Wang, L. Elevated cross-talk between subchondral bone and cartilage in osteoarthritic joints. BONE 2012, 51(2), 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werdyani, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, G.; Furey, A.; Randell, E.; Rahman, P.; Zhai, G. Endotypes of primary osteoarthritis identified by plasma metabolomics analysis. RHEUMATOLOGY 2021, 60(6), 2735–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, F.; Widera, P.; Mobasheri, A.; Blair, J.; Struglics, A.; Uebelhoer, M.; Henrotin, Y.; Marijnissen, A.; Kloppenburg, M.; Blanco, F.; et al. Osteoarthritis endotype discovery via clustering of biochemical marker data. ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES 2022, 81(5), 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, A.; Mazzorana, M.; Vacher, J.; Jurdic, P. Osteoimmunology: an integrated vision of immune and bone systems. M S-MEDECINE SCIENCES 2009, 25(3), 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y; Zhang, L; Xiong, Q. Bench-to-bedside strategies for osteoporotic fracture: From osteoimmunology to mechanosensation. BONE RESEARCH 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Akagi, M.; Tsukamoto, I.; Hashimoto, K.; Morishita, T.; Ito, T.; Goto, K. RANKL-mediated osteoclastic subchondral bone loss at a very early stage precedes subsequent cartilage degeneration and uncoupled bone remodeling in a mouse knee osteoarthritis model. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC SURGERY AND RESEARCH 2025, 20(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco, G.; Marzano, E.; Mastrostefano, A.; Pitocco, D.; Castilho, R.; Zambelli, R.; Mascio, A.; Greco, T.; Cinelli, V.; Comisi, C.; et al. The Pathogenetic Role of RANK/RANKL/OPG Signaling in Osteoarthritis and Related Targeted Therapies. BIOMEDICINES 2024, 12(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhu, S.; Lei, G. T Cells in Osteoarthritis: Alterations and Beyond. FRONTIERS IN IMMUNOLOGY 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, R.; Blom, A.; Nelissen, R.; Broekhuis, D.; van der Kraan, P.; Meulenbelt, I.; van den Bosch, M.; Ramos, Y. Mechanical stress and inflammation have opposite effects on Wnt signaling in human chondrocytes. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH 2024, 42(2), 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Chu, Q.; Shi, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, L. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances. SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION AND TARGETED THERAPY 2025, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, G.; Wen, C.; Jia, X.; Li, Y.; Crane, J.; Mears, S.; Askin, F.; Frassica, F.; Chang, W.; Yao, J.; et al. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling in mesenchymal stem cells of subchondral bone attenuates osteoarthritis. NATURE MEDICINE 2013, 19(6), 704–+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarfi, W.; Yunus, M.; Hamid, A.; Maarof, M.; Rani, R. Breaking Down Osteoarthritis: Exploring Inflammatory and Mechanical Signaling Pathways. LIFE-BASEL 2025, 15(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyatake, K.; Kumagai, K.; Imai, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Inaba, Y. Sclerostin inhibits interleukin-1β-induced late stage chondrogenic differentiation through downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Dao, J.; Kasaci, N.; Friedman, A.; Noll, L.; Goker-Alpan, O. Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, sclerostin and DKK-1, correlate with pain and bone pathology in patients with Gaucher disease. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xing, L.; Tian, F. Wnt signaling: a promising target for osteoarthritis therapy. CELL COMMUNICATION AND SIGNALING 2019, 17(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, B.; Vajda, E.; Nagy, E. Regulatory Effects and Interactions of the Wnt and OPG-RANKL-RANK Signaling at the Bone-Cartilage Interface in Osteoarthritis. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR SCIENCES 2019, 20(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.; Miller, R.; Malfait, A. The Genesis of Pain in Osteoarthritis: Inflammation as a Mediator of Osteoarthritis Pain. CLINICS IN GERIATRIC MEDICINE 2022, 38(2), 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumaran, A.; Deveza, L.; Atukorala, I.; Hunter, D. Assessment of Pain in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. JOURNAL OF PERSONALIZED MEDICINE 2023, 13(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.; Dubouis, L.; Mangin, M.; Hunter, D.; March, L.; Hawker, G.; Guillemin, F. Defining Flare in Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee: A Systematic Literature Review—OMERACT Virtual Special Interest Group. JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY 2017, 44(12), 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, M.; Hilliquin, P.; Rozenberg, S.; Valat, J.; Vignon, E.; Coste, P.; Savarieau, B.; Allaert, F. Validation of the KOFUS (Knee Osteoarthritis Flare-Ups Score). JOINT BONE SPINE 2009, 76(3), 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, E; Ogollah, R; Peat, G. Acute flare-ups ’in patients with, or at high risk of, knee osteoarthritis: a daily diary study with case-crossover analysis. OSTEOARTHRITIS CARTILAGE 2019, 27(8), 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieh, B.; El-Mesallamy, H.; Kassem, D. Beyond mechanical loading: The metabolic contribution of obesity in osteoarthritis unveils novel therapeutic targets. HELIYON 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, U.; Varughese, I.; Sun, A.; Wu, X.; Crawford, R.; Prasadam, I. Obesity, Inflammation, and Immune System in Osteoarthritis. FRONTIERS IN IMMUNOLOGY 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Berenbaum, F.; Mobasheri, A. Obesity-induced fibrosis in osteoarthritis: Pathogenesis, consequences and novel therapeutic opportunities. OSTEOARTHRITIS AND CARTILAGE OPEN 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Raynor, W.; Werner, T.; Baker, J.; Alavi, A.; Revheim, M. 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF PET/CT Global Assessment of Large Joint Inflammation and Bone Turnover in Rheumatoid Arthritis. DIAGNOSTICS 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, A.; Neve, A.; Macchiarola, A.; Gaudio, A.; Marucci, A.; Cantatore, F. RANKL/OPG Ratio and DKK-1 Expression in Primary Osteoblastic Cultures from Osteoarthritic and Osteoporotic Subjects. JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY 2013, 40(5), 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck-Brentano, T.; Bouaziz, W.; Marty, C.; Geoffroy, V.; Hay, E.; Cohen-Solal, M. Dkk-1-Mediated Inhibition of Wnt Signaling in Bone Ameliorates Osteoarthritis in Mice. ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY 2014, 66(11), 3028–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, D.; Viapiana, O.; Fracassi, E.; Idolazzi, L.; Dartizio, C.; Povino, M.; Adami, S.; Rossini, M. Sclerostin and DKK1 in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis Treated with Denosumab. JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH 2012, 27(11), 2259–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Murray, D.; Hurson, C.; O’Brien, J.; Doran, P.; O’Byrne, J. The Role of Dkk1 in Bone Mass Regulation: Correlating Serum Dkk1 Expression with Bone Mineral Density. JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH 2011, 29, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Xu, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Shuai, B.; Zhu, X.; Li, C.; Ma, C.; Lv, L. Association of Serum Dkk-1 Levels with β-catenin in Patients with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. JOURNAL OF HUAZHONG UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY-MEDICAL SCIENCES 2015, 35, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, A.; Labib, A.; Haseeb, A.; Abd-Elaziz, A. Correlation of Circulating Dickkopf-1 Level with Sonographic Findings and Radiographic Grading in Primary Knee Osteoarthritis. JOURNAL OF MEDICAL ULTRASOUND 2025, 33(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honsawek, S.; Tanavalee, A.; Yuktanandana, P.; Ngarmukos, S.; Saetan, N.; Tantavisut, S. Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1) in plasma and synovial fluid is inversely correlated with radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis patients. BMC MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Abdel-Monem, S.; Elbarashy, A.; Elhussieny, H.; Elsayed, R. Study of serum and synovial fluid Dickkopf-1 levels in patients with primary osteoarthritis of the knee joint in correlation with disease activity and severity. EGYPTIAN RHEUMATOLOGY AND REHABILITATION 2020, 47(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; Behiry, E. DECREASED SYNOVIAL LEVELS OF DICKKOPF-1 ARE ASSOCIATED WITH RADIOLOGICAL PROGRESSION IN KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS PATIENTS. ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES 2018, 77, 1146–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Wang, C.; Lu, W.; Xu, Z.; Shi, D.; Chen, D.; Teng, H.; Jiang, Q. Serum levels of the bone turnover markers dickkopf-1, osteoprotegerin, and TNF-α in knee osteoarthritis patients. CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY 2017, 36(10), 2351–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, B.; Xing, L.; Chen, D. Osteoprotegerin, the bone protector, is a surprising target for β-catenin signaling. CELL METABOLISM 2005, 2(6), 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilichou, A.; Papassotiriou, I.; Michalakakou, K.; Fessatou, S.; Fandridis, E.; Papachristou, G.; Terpos, E. High levels of synovial fluid osteoprotegenin (OPG) and increased serum ratio of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) to OPG correlate with disease severity in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. CLINICAL BIOCHEMISTRY 2008, 41(9), 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystufkova, O.; Niederlova, J.; Senolt, V.; Hladikova, M.; Ruzickova, S.; Vencovsky, J. OPG and RANKL in serum and synovial fluids of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and spondylarthropathy. 2003, 5, S31–S31. [Google Scholar]

- Quaresma, T.; de Almeida, S.; da Silva, T.; Louzada-Junior, P.; de Oliveira, R. Comparative study of the synovial levels of RANKL and OPG in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and osteoarthritis. ADVANCES IN RHEUMATOLOGY 2023, 63(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csifo, E.; Katona, T.; Arseni, J.; Nagy, E.; Gergely, I.; Nagy, Ö. Correlation of Serum and Synovial Osteocalcin, Osteoprotegerin and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha with the Disease Severity Score in Knee Osteoarthritis. ACTA MEDICA MARISIENSIS 2014, 60(3), 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E. E.; Varga-Fekete, T.; Puskas, A.; Kelemen, P.; Brassai, Z.; Szekeres-Csiki, K.; Gombos, T.; Csanyi, M. C.; Harsfalvi, J. High circulating osteoprotegerin levels are associated with non-zero blood groups. BMC CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugisaki, R.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Sasa, K.; Kaneko, K.; Tanaka, M.; Itose, M.; Inoue, S.; Baba, K.; Shirota, T.; et al. Possible involvement of elastase in enhanced osteoclast differentiation by neutrophils through degradation of osteoprotegerin. BONE 2020, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E. Elastase mediated-degradation of osteoprotegerin: Possible pitfalls and functional relevance. BONE 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, W.; Funck-Brentano, T.; Lin, H.; Marty, C.; Hay, E.; Cohen-Solal, M. LACK OF SCLEROSTIN PROMOTES OSTEOARTHRITIS BY ACTIVATING CANONICAL AND NON-CANONICAL WNT PATHWAYS. OSTEOARTHRITIS AND CARTILAGE 2014, 22, S340–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Christiansen, B.; Murugesh, D.; Sebastian, A.; Hum, N.; Collette, N.; Hatsell, S.; Economides, A.; Blanchette, C.; Loots, G. SOST/Sclerostin Improves Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis and Inhibits MMP2/3 Expression After Injury. JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH 2018, 33(6), 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldin, A.B.; Mohamed, E.S.; El Zahraa; Hassan, F. The role of sclerostin in knee osteoarthritis and its relation to disease progression. EGYPTIAN JOURNAL OF INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019, 31, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J-C.; Sornay-Rendu, E.; Borel, O.; Bertholon, C.; Garnero, P.; Chapurlat, R. Serum sclerostin is not associated with knee osteoarthritis prevalence and progression of Kellgren-Lawrence score in women: the OFELY study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2014, 22, S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halupczok-Zyla, J.; Jawiarczyk-Przybylowska, A.; Bolanowski, M. Sclerostin and OPG/RANK-L system take part in bone remodeling in patients with acromegaly. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yan, Y. Beyond Bone Loss: A Biology Perspective on Osteoporosis Pathogenesis, Multi-Omics Approaches, and Interconnected Mechanisms. BIOMEDICINES 2025, 13(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, Y.; Kennedy, S.; Swearingen, C.; Tambiah, J. The Novel, Intra-articular CLK/DYRK1A Inhibitor Lorecivivint (LOR; SM04690), Which Modulates the Wnt Pathway, Improved Responder Outcomes in Subjects with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Post Hoc Analysis from a Phase 2b Trial. ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY 2019, 71. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | All cases (n=72) | BMI<30 (n=53) | BMI≥30 (n=19) | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 68 (63-75) | 68 (62-75) | 68 (63-75) | 0.829 |

| Gender (f/m) | 62 (86.1) / 10 (13.9) | 44 (83) / 9 (17) | 18 (94.4)/ 1 (5.6) | 0.272 |

| History, symptoms, and comorbidities | ||||

| Disease history (years) | 7 (3-15) | 7 (3-11) | 10 (5-15) | 0.120 |

| Crepitus (y/n) | 50 (69.4) / 22 (30.6) | 34 (64.2) / 19 (35.8) | 16 (84.2) /3 (15.8) | 0.148 |

| Sensibility (y/n) | 27 (37.5) / 45 (62.5) | 17 (32.1) / 36 (67.9) | 10 (52.6) / 9 (47.4) | 0.166 |

| Hyperemia (y/n) | 62 (86.1) / 10 (13.9) | 45 (84.9) / 8 (15.1) | 17 (89.5)/ 2 (10.5) | 1.000 |

| Swelling (y/n) | 7 (9.7) / 65 (90.3) | 5 (9.4) / 48 (90.6) | 2 (10.5) /17 (89.5) | 0.988 |

| Bony prominences (y/n) | 17 (23.6) / 55 (76.4) | 12 (22.6) / 41 (77.4) | 5 (35.5)/ 14 (64.5) | 0.759 |

| Mobility impairment (y/n) | 39 (54.2) / 33 (45.8) | 26 (49) / 27 (51) | 13 (68.4) / 6 (31.6) | 0.184 |

| Coxalgia (y/n) | 6 (8.3) / 67 (91.7) | 3 (5.6) / 50 (94.4) | 3 (15.8) /16 (84.2) | 0.183 |

| Dysplasia (y/n) | 5 (6.9) / 67 (93.1) | 5 (9.4) / 48 (90.6) | 0 (0) /19 (100) | 0.316 |

| Limping (y/n) | 23 (31.9) / 49 (68.1) | 15 (28.3) / 38 (71.7) | 8 (42.1) /11 (57.9) | 0.389 |

| Trauma in history (y/n) | 6 (8.3) / 67 (91.7) | 4 (7.5) / 49 (92.5) | 2 (10.5) /17 (89.5) | 0.647 |

| Heart failure (y/n) | 58 (80.5) / 14 (19.5) | 41 (77.5) / 12 (22.5) | 17 (89.5) /2 (10.5) | 0.714 |

| Hypertension (y/n) | 57 (79.2) / 15 (20.8) | 41 (77.5) / 12 (22.5) | 16 (84.2) /3 (15.8) | 0.744 |

| Diabetes (y/n) | 17 (23.6) / 55 (76.4) | 13 (24.5) / 38 (75.5) | 4 (23.5) /17 (76.5) | 0.761 |

| Hypothyroidism (y/n) | 13 (18) / 59 (82) | 9 (17) / 44 (83) | 4 (21)/ 15 (79) | 0.692 |

| Dyslipidemia (y/n) | 28 (38.8) / 54 (61.2) | 18 (33.9) / 35 (66.1) | 10 (52.6) / 9 (47.4) | 0.152 |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis (y/n) | 12(16.6)/9(12.5)/51(70.9) | 9(16.9)/6(11.3)/38(71.8) | 3(15.7)/3(15.7)/13(68.6) | 0.600 |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Body mass index | 25.7 (24-30.1) | 24.5 (23.7-26.6) | 31 (30.4-31.6) | <0.001 |

| Kellgren-Lawrence score | 2.35 ± 0.08 | 2.30 ± 0.09 | 2.50 ± 0.14 | 0.328 |

| WOMAC | 25.6 ± 1.27 | 25.5 ± 1.42 | 26.2 ± 2.83 | 0.761 |

| VAS | 4.41 ± 0.17 | 4.51 ± 0.20 | 4.16 ± 0.31 | 0.274 |

| KOFUS flare-ups | 1.94 ± 0.30 | 2.02 ± 0.34 | 1.73 ± 0.65 | 0.518 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 3.2 (1.8-5.2) | 3.2 (1.6-4.8) | 3.8 (2.8-7.1) | 0.064 |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 6.4 (5.6-7.3) | 6.3 (5.6-7.2) | 7.1 (5.7-7.8) | 0.561 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 (13-14.4) | 13.6 (12.9-14.4) | 13.8 (13.4-14.4) | 0.627 |

| N/L ratio | 1.9 (1.4-2.4) | 1.9 (1.3-2.3) | 1.9 (1.4-2.4) | 0.638 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 400 (330-510) | 395 (330-500) | 450 (300-560) | 0.793 |

| SIRI | 705 (519-1188) | 6898 (533-880) | 945 (466-1398) | 0.498 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 4.9 (4.3-5.7) | 4.8 (4.4-5.8) | 5.5 (4.2-5.6) | 0.558 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 82.9 ± 2.1 | 80.0 ± 2.5 | 80.9 ± 3.9 | 0.963 |

| Cholesterol, total (mg/dL) | 204 ± 6 | 197 ± 7 | 222 ± 11 | 0.197 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 147 ± 9 | 147 ± 11 | 143 ± 14 | 0.711 |

| TSH (µUI/mL) | 1.9 (1.2-3.3) | 1.9 (1.2-3.1) | 2.0 (1.5-3.4) | 0.724 |

| DKK-1 (pg/mL) | 802 (467-1234) | 808 (497-1306) | 693 (456-1207) | 0.667 |

| Sclerostin (pg/mL) | 104 (59-526) | 115 (59-535) | 76 (55-328) | 0.713 |

| OPG (pg/mL) | 3344 (2599-4654) | 2904 (2222-4073) | 3669 (2698-5156) | 0.462 |

| RANKL (pg/mL) | 61 (43-368) | 58 (41-428) | 61 (43-244) | 0.830 |

| Medication | ||||

| Topical creams and gels | 68 (94.4) / 4 (5.6) | 49 (92.4) / 4 (7.6) | 19 (100) / 0 (0) | 0.221 |

| Analgesics | 42 (58.3) / 30 (41.7) | 32 (67.9) / 21 (32.1) | 10 (52.6) / 9 (47.4) | 0.559 |

| NSAIDs, p.o. | 51 (70.8) / 21 (29.2) | 37 (69.8) / 16 (30.2) | 14 (73.6) / 5 (26.4) | 0.751 |

| Chondroprotectors, p.o. | 39 (54.2) / 33 (45.8) | 29 (54.7) / 24 (45.3) | 10 (52.6) / 9 (47.4) | 0.876 |

| Corticosteroids, local infiltrations | 19 (26.4) / 53 (73.6) | 13 (24.5) / 40 (75.5) | 6 (31.6) / 13 (68.4) | 0.552 |

| PC summary | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 3.62 | 2.70 | 2.11 | 1.85 |

| Proportion of variance | 17.24% | 12.87% | 10.07% | 8.81% |

| Cumulative proportion of variance | 17.24% | 30.12% | 40.19% | 48.99% |

| VAS | KOFUS | WOMAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Spearman R | p-level | Spearman R | p-level | Spearman R | p-level |

| Age | 0.123 | 0.302 | 0.233 | 0.048 | 0.297 | 0.011 |

| Disease history | 0.082 | 0.491 | 0.025 | 0.834 | 0.278 | 0.018 |

| Body mass index | 0.071 | 0.550 | -0.026 | 0.826 | 0.111 | 0.353 |

| WOMAC | 0.651 | <0.001 | 0.534 | <0.001 | - | - |

| K-L score | 0.430 | <0.001 | 0.303 | 0.009 | 0.539 | <0.001 |

| VAS | - | - | 0.597 | <0.001 | 0.623 | <0.001 |

| KOFUS | 0.597 | <0.001 | - | - | 0.534 | <0.001 |

| WBC | 0.134 | 0.303 | 0.087 | 0.507 | 0.082 | 0.529 |

| N/L ratio | 0.023 | 0.855 | -0.048 | 0.714 | 0.085 | 0.514 |

| Monocytes | 0.097 | 0.454 | -0.034 | 0.794 | 0.101 | 0.438 |

| SIRI | 0.099 | 0.445 | -0.042 | 0.746 | 0.147 | 0.257 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.224 | 0.081 | 0.034 | 0.794 | 0.053 | 0.680 |

| eGFR | 0.010 | 0.937 | -0.087 | 0.504 | -0.089 | 0.489 |

| Platelets | 0.163 | 0.210 | -0.026 | 0.840 | 0.229 | 0.075 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.139 | 0.242 | -0.017 | 0.885 | 0.203 | 0.087 |

| TSH | -0.214 | 0.102 | 0.036 | 0.787 | 0.101 | 0.445 |

| Uric acid | 0.016 | 0.901 | -0.042 | 0.750 | -0.114 | 0.385 |

| DKK-1 | 0.166 | 0.191 | 0.236 | 0.046 | 0.147 | 0.2154 |

| Sclerostin | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.102 | 0.394 | -0.093 | 0.434 |

| OPG | 0.003 | 0.977 | 0.040 | 0.740 | 0.100 | 0.402 |

| RANKL | 0.083 | 0.750 | 0.004 | 0.971 | 0.059 | 0.621 |

| OPG/RANKL | 0.071 | 0.550 | 0.065 | 0.588 | 0.023 | 0.844 |

| Variable | Estimate | 95% CI | t | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -3.500 | -7.204 to 0.204 | 1.90 | 0.063 |

| Body mass index | 0.060 | -0.061 to 0.181 | 0.99 | 0.322 |

| Bone mineral density | 0.256 | -0.708 to 1.220 | 0.53 | 0.596 |

| Kellgren-Lawrence score | 1.311 | 0.413 to 2.209 | 2.94 | 0.005 |

| sDKK-1 | 0.001 | 4.413e-007 to 0.002 | 2.01 | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).