Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Paravalvular leak (PVL) remains a clinically important complication after surgical or transcatheter valve implantation, presenting predominantly with heart failure (HF) and/or high-shear hemolysis. While redo surgery can be definitive, contemporary candidates frequently carry prohibitive operative risk, positioning transcatheter PVL closure as a key therapeutic alternative. However, available outcome data are largely derived from observational series and registries with heterogeneity in PVL mechanisms, prosthesis types, imaging protocols, and endpoint definitions. Standardized frameworks—such as those proposed by the PVL Academic Research Consortium—support harmonized PVL grading and clinically meaningful composite endpoints that integrate imaging/hemodynamic results with patient-centered outcomes. Across datasets, the most consistent determinant of benefit is residual PVL severity: procedural efficacy is most commonly defined as achieving ≤mild residual regurgitation without prosthetic leaflet interference, device embolization, or major complications. This review provides a step-by-step, phenotype-driven approach to transcatheter PVL closure, emphasizing multimodality imaging (TEE and cardiac CT, with adjunct CMR and PET when appropriate), access and support planning tailored to valve position, and morphology-matched device selection—often requiring modular multi-device strategies for elongated crescentic channels, particularly in hemolysis-predominant presentations. We also synthesize evidence on complications and bailout management, with a focus on preventable high-severity events (leaflet impingement, embolization, stroke/air, vascular injury, tamponade) and standardized pre-release safety checks. Collectively, contemporary practice supports high implant success in experienced programs, with clinical improvement tightly coupled to procedural endpoint quality and careful Heart Team selection.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology

2.1. Structural Substrate

2.1.1. Surgical Prostheses

2.1.2. Transcatheter Valves (TAVI)

2.2. Fluid Mechanics

2.3. Chamber-Specific Hemodynamic Consequences

2.3.1. Mitral PVL

2.3.2. Aortic PVL

2.3.3. Tricuspid and Pulmonary PVL

2.4. Hemolysis

2.5. Infection and Inflammation

2.6. Integrative Pathophysiology

3. Severity Assessment

3.1. Mitral PVL

3.2. Aortic PVL

3.3. Multimodality Imaging

3.3.1. Cardiac CT

3.3.2. CMR

3.3.3. Angiography

4. Procedural Endpoints for PVL Closure

4.1. Technical Success

4.2. Procedural Success

4.3. Clinical Success

- HF phenotype: improvement by ≥1 NYHA class, improved functional capacity, and/or reduction in HF hospitalizations;

- Hemolysis phenotype: improvement in hemolysis markers and, critically, freedom from transfusion/erythropoietin dependence, when hemolysis is the dominant indication.

| Predominant clinical phenotype | Practical severity anchors (pre-procedure) | Minimum imaging endpoints to report | Target residual PVL (pragmatic) | Clinical success endpoint(s) |

| Heart failure–predominant PVL (mitral) | Symptoms (NYHA); pulmonary venous congestion; LA dilation/V-wave; supportive Doppler signs (e.g., pulmonary venous systolic blunting/reversal when interpretable) | 2D/3D TEE mapping (location, circumferential extent, number of jets); pre/post mean mitral gradient; residual PVL grade at exit + predischarge | ≤ mild–moderate (5-class) or ≤ mild (3-class), and no clinically relevant iatrogenic mitral stenosis | ≥1 NYHA class improvement; fewer HF admissions; QoL improvement |

| Heart failure–predominant PVL (aortic / post-TAVI) | Dyspnea/low output; LV volume load; supportive Doppler (diastolic flow reversal) | Echo integrative grade (include circumferential extent); angiography/hemodynamics if used; residual PVL at exit + predischarge | Preferably ≤ mild–moderate; consider hemodynamic optimization during procedure (esp. post-TAVI) | HF rehospitalization reduction; QoL; survival (longer-term) |

| Hemolysis-predominant PVL (any position; often mechanical) | Hemoglobin trend; LDH↑; haptoglobin↓; indirect bilirubin↑; transfusion/EPO requirement | Precise jet localization (often 3D TEE); document elimination of high-velocity residual micro-jet | As close to none/trace as achievable (hemolysis is “micro-jet sensitive”) | Transfusion independence; improvement/normalization trend of hemolysis labs |

| Mixed HF + hemolysis | Combined anchors above | Full integrative imaging set + labs | Aim for lowest achievable residual grade without prosthesis compromise | NYHA improvement and hemolysis improvement/transfusion-free |

5. Devices for Transcatheter PVL Closure

5.1. Dedicated PVL Occluders

5.1.1. Occlutech Paravalvular Leak Device (PLD)

- Rectangular PLD: best suited for elongated/crescentic defects where sealing is required along an arc;

- Square PLD: useful for more compact defects;

5.1.2. Amplatzer Vascular Plug (AVP)

5.2. Ductal, Septal, and VSD Occluders

5.2.1. Amplatzer Duct Occluder (ADO) and ADO II

5.2.2. Muscular VSD Occluders and ASD Occluders

5.3. Coils and Adjunctive “Micro-Jet” Solutions

5.4. Multi-Device Strategies and Device Combinations

| Device / platform | Typical PVL morphology where it fits best | Key advantages | Key limitations / cautions |

| Occlutech PLD (square/rectangular; waist/twist) | Crescentic/elliptical PVL; irregular channels (mitral & aortic) | Purpose-built geometry; PET patches; markers; retrievable/repositionable | Requires careful sizing to avoid leaflet interaction; availability varies by region |

| Amplatzer Valvular Plug III / oblong PVL plug concept | Elliptical/crescentic PVL; multi-orifice channels | Oblong geometry; broad size range; widely used in PVL practice; under formal evaluation (PARADIGM) | Leaflet interference remains a risk; sometimes multiple devices needed |

| AVP II | More tubular/round PVL channels | Familiar platform; effective occlusion in suitable geometries | Less conformable for crescentic PVL; can interact with leaflets if protruding |

| AVP IV (low profile) | Small channels; post-TAVI PVL where crossability is limiting | Low-profile deliverability; common in post-TAVI PVL closure practice | Not ideal for large crescentic defects; may require multiple devices |

| ADO / ADO II | Short tunnel-like PVL; selective mitral/tricuspid PVL cases | Disc-based stability; can be useful when “duct-like” anatomy exists | Off-label in PVL; embolization/interference risk if landing zone is marginal |

| Muscular VSD / ASD occluders | Large defects with adequate landing zone | Large discs/waist options | Higher interference risk; not designed for PVL geometry |

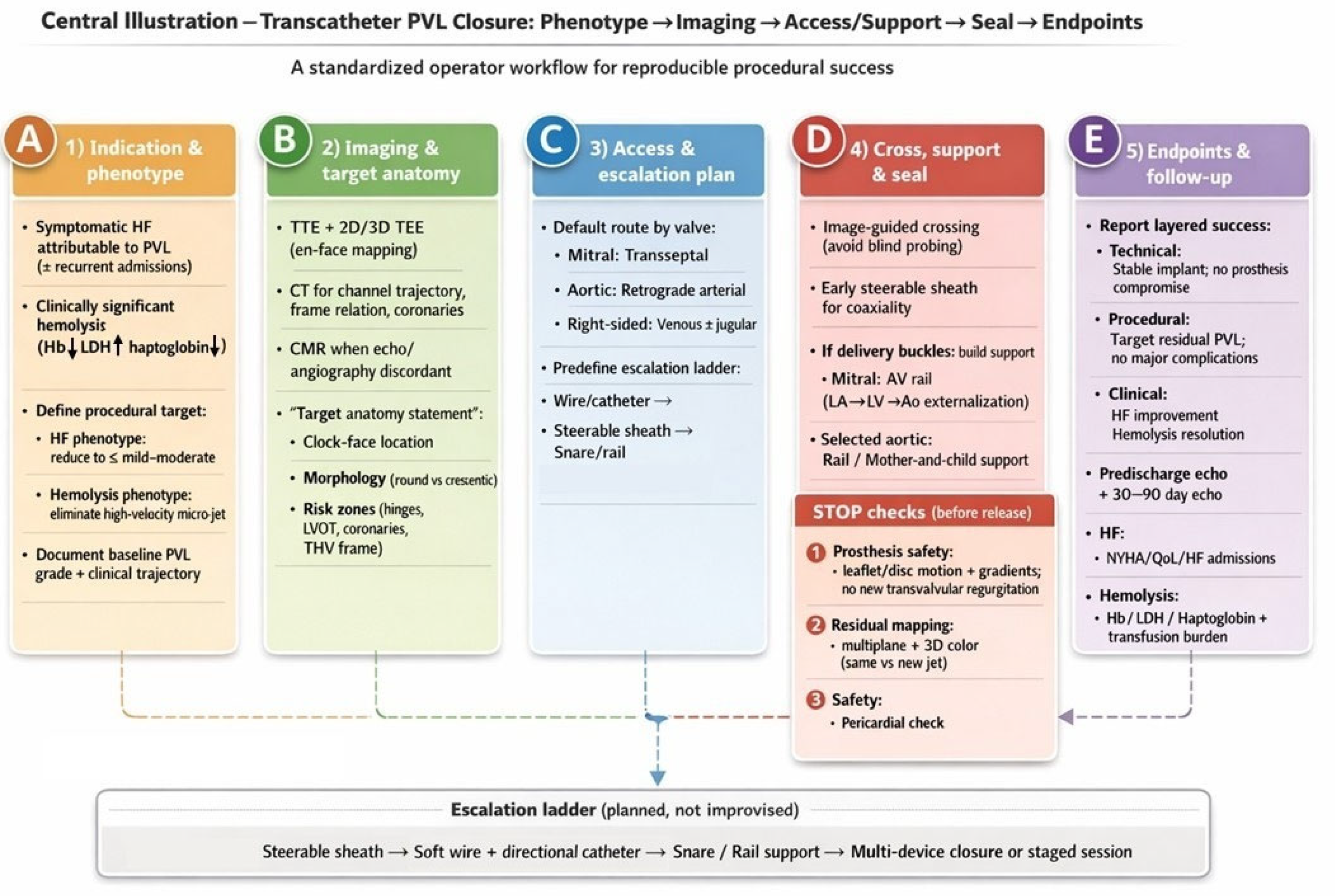

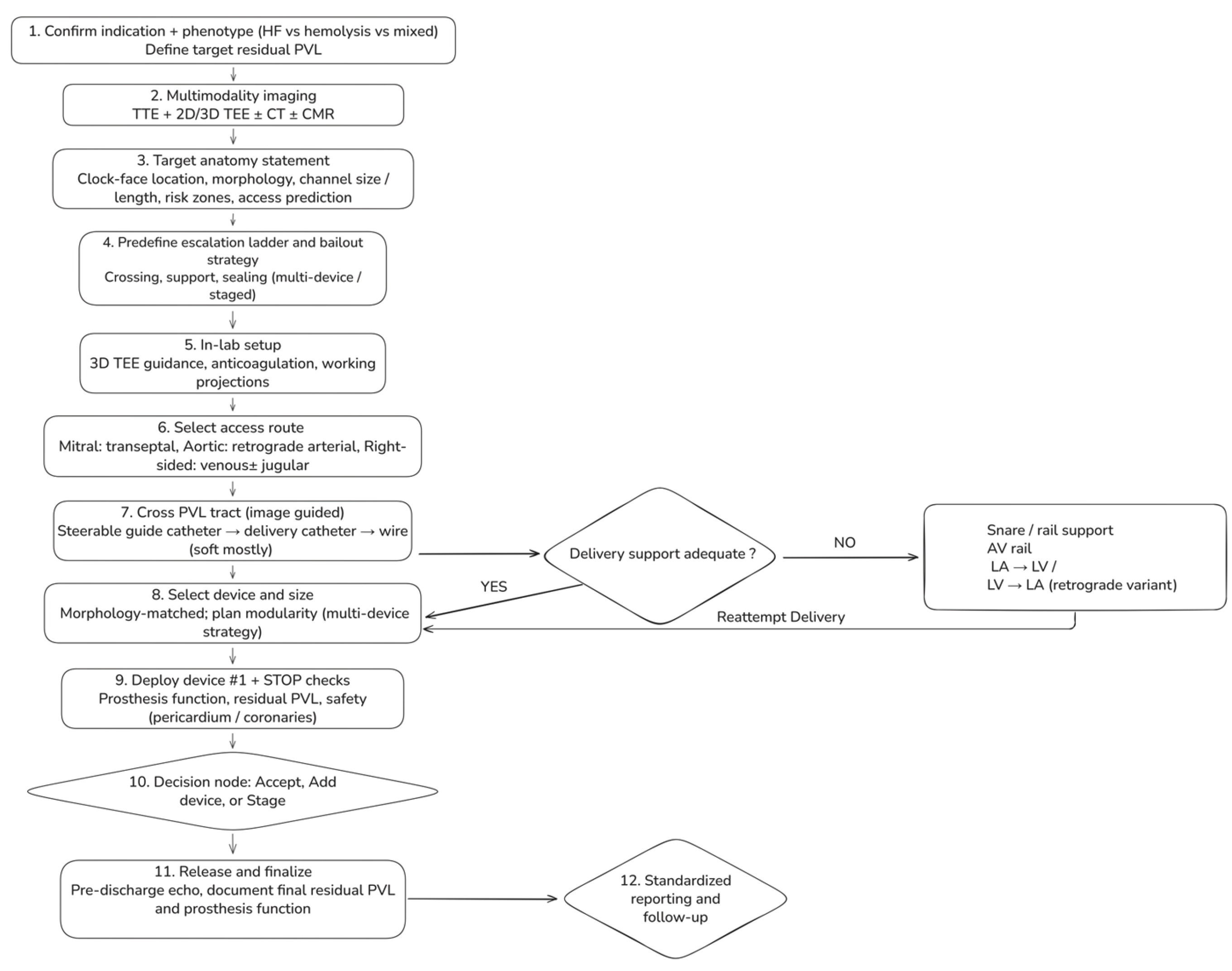

6. Step-By-Step Workflow For Transcatheter PVL Closure

6.1. Step 1 — Confirm Indication And Define A Phenotype-Driven Procedural Target (Pre-Procedure clinic/Heart Team)

6.2. Step 2 — Multimodality Imaging Briefing: A One-Page “Target Anatomy Statement” (TEE + CT ± CMR)

- Valve position and prosthesis type (mechanical/bioprosthetic/transcatheter; ViV/ViR, if applicable).

- PVL location using a standardized clock-face (mitral surgeon’s view; aortic short-axis orientation).

- Morphology: round vs crescentic/elliptical; single channel with multiple exits vs multiple discrete channels; estimated channel length, maximum width, and circumferential extent.

- Risk zones: proximity to mechanical hinges, coronary ostia (aortic), LVOT relevance (mitral), and THV frame constraints (post-TAVI).

- Access prediction: anticipated approach (transseptal vs retrograde) and likelihood of needing a rail strategy.

6.3. Step 3 — Predefine an “Escalation Ladder” (Avoid Improvisation Mid-Case)

- Crossing (steerable sheath → catheter → wire → alternative access)

- Support (long sheath/mother-and-child → snare-assisted redirection → arteriovenous rail)

- Sealing (single device → multiple devices → staged closure)

6.4. Step 4 — Room Setup and Intraprocedural Imaging Workflow

6.5. Step 5 — Access Strategy (Default and Bailout)

- Mitral PVL (default: transseptal): Select puncture height and posterior/anterior orientation to optimize catheter coaxiality toward the intended clock-face region. Posterior–inferior puncture often improves reach for posterior leaks; a more superior puncture may improve alignment for anterior leaks, while an overly anterior puncture can promote extreme angulation, prolapse, and early need for rail rescue.

- Aortic PVL (default: retrograde arterial): Select working projections that “open” the prosthesis and profile the suspected PVL location; when available, CT-derived angulation can reduce trial-and-error. Coronary protection should be considered selectively when anatomy is borderline.

- Right-sided PVL: Venous access; jugular access often improves coaxiality for tricuspid targets depending on defect location and RA geometry.

6.6. Step 6 — Cross the PVL Tract (Image-Guided, Not “Search-and-Probe”)

6.7. Step 7 — Create support and Apply “Rail Physics” (Snaring + Arteriovenous Rail)

- Mitral PVL AV rail (veno–arterial externalization; high-yield rescue): cross PVL from LA → LV, advance into the aorta, snare and externalize via arterial access, then advance the delivery sheath across the tract on stable rail support. This converts unstable pushing into controlled tracking and reduces repeated prolapse.

- Retrograde variant: in selected anatomies, cross retrogradely from LV → LA and snare/externalize via venous access to establish an AV rail; use snaring also to redirect trajectory and straighten tortuosity before sheath advancement.

6.8. Step 8 — Device selection and Sizing (Morphology-Matched, with Planned Modularity)

6.9. Step 9 — Deployment and Mandatory “Stop Checks” Before Release

- Prosthesis function: no mechanical leaflet/disc restriction; no new transvalvular regurgitation; no clinically relevant gradient rise.

- Residual PVL mapping: multiplane color + 3D color; determine whether residual jets represent remnant vs new channel.

- Safety: pericardial assessment after extensive manipulation; coronary compromise evaluation in aortic/root-adjacent cases when relevant.

6.10. Step 10 — Decision Node: Accept vs Add Device vs Stage

6.11. Step 11 — Post-Procedure Assessment And Standardized Reporting

7. Valve-Specific Strategy and Operator Pearls

7.1. Mitral PVL

- Standardize clock-face mapping (surgeon’s view) between imager and operator before any wire crosses.

- If you “need a stiffer wire,” pause: most failures are geometry/support failures—change projection, use steerability, or build a rail instead of escalating stiffness blindly.

- In hemolysis phenotype, do not accept a small, high-velocity residual jet even if global grade looks mild; this is a common reason for “procedural success but clinical failure.”

7.2. Aortic PVL

- Treat any new transvalvular regurgitation or prosthetic gradient rise as a device–prosthesis interaction problem: recapture immediately.

- When angiographic grade and echo grade disagree, use hemodynamic adjuncts and consider CMR for definitive regurgitant quantification at follow-up if clinical course is discordant.

7.3. Post-TAVI PVR

- Consider invasive hemodynamics as adjuncts, recognizing that vasopressors, pacing, and compliance can confound interpretation.

- Residual “mild–moderate” (5-class) is not benign in frail, low-reserve patients; aim for reduction to mild or less when safely achievable.

7.4. Tricuspid PVL

- When stability is uncertain, prefer devices with favorable anchoring geometry and confirm stability across respiratory cycles before release.

- Maintain snare readiness; right-sided embolization pathways can be rapid.

7.5. Pulmonary PVL

- Pre-procedure CT is particularly helpful to understand conduit angulation and landing zones when echocardiography is limited.

- Because pulmonary circuits are low pressure, aggressive oversizing to “force seal” can paradoxically destabilize the system and increase embolization risk; prioritize conformability and stability.

7.6. Universal “Operator Pearls” That Transcend Valve Position

| Valve position / scenario | Default access | Key imaging guidance | Escalate early when… | Device strategy tendency | Unique hazards / hard-stops |

| Mitral PVL (surgical MVR / ViV / ViR) | Transseptal | 3D TEE en-face mapping ± CT for tract trajectory & transseptal planning | Repeated prolapse/non-coaxiality → steerable sheath; delivery-system buckling → AV rail | Crescentic common → oblong/rectangular or multi-device; hemolysis → “micro-jet elimination” | Mechanical hinge interference = immediate recapture |

| Aortic PVL (surgical AVR) | Retrograde arterial | TTE/TEE integrative + angiography; CT if redo/root complexity | Poor support → long sheath/mother-and-child; multiple jets → reassess for multi-channel anatomy | Often focal; single device more common | Coronary proximity/root anatomy; new transvalvular regurgitation or gradient rise = recapture |

| Post-TAVI PVR | Retrograde arterial (usually) | VARC-3-aligned grading; CT for angles/track; hemodynamics as adjunct | Cannot cross with standard catheter → low-profile strategy (AVP IV class) | Crossability dictates choice; aim reduction to mild or less | Frame interaction; multi-jet eccentricity; discordant grading common |

| Tricuspid PVL | Venous; consider jugular | TEE/ICE depending on windows | Instability/embolization concern → stability testing + snare readiness | Often single device; avoid oversizing | Embolization risk; confirm stability across respiration |

| Pulmonary PVL / RVOT | Venous | CT helpful for conduit geometry | Reach/support limitations → long sheaths/rail concepts | Stability-focused | Low-pressure circuit → confirm anchoring; embolization preparedness |

| Technical challenge | Recommended approach | Rationale |

| Cannot engage/cross the PVL channel | Switch fluoroscopic projection; use 3D TEE en-face localization; escalate early to a steerable sheath | Minimizes blind probing; improves coaxial alignment with the paravalvular gutter |

| Wire repeatedly prolapses | Add a microcatheter for support; use a short-tip hydrophilic wire; reduce LV/LA loop | Improves tip control; preserves tract access; reduces traumatic force transmission |

| Delivery system buckles / cannot advance sheath | Build an AV rail (mitral) or selective rail strategy; consider long sheath/mother-and-child support | Converts unstable pushing into controlled tracking; stabilizes coaxial delivery |

| Clinically relevant residual jet persists | Prefer a second device (or staged modular sealing) rather than extreme oversizing of a single device | Crescentic/multi-orifice channels seal better with modular closure and lower interference risk |

| Any mechanical leaflet/disc interaction | Immediate recapture; downsize and/or reposition; change geometry strategy | Prosthesis safety is non-negotiable; subtle restriction can be catastrophic |

8. Special Scenarios

8.1. Active or Recent Infective Endocarditis and Perivalvular Extension (Abscess, Pseudoaneurysm, Fistula)

8.2. Large Circumferential Dehiscence and The “Rocking Prosthesis” Problem

8.3. Multiple Leaks, Crescent-Shaped Channels, and Multi-Orifice Exits

8.4. Mechanical Prostheses (Mitral/Aortic)

8.5. PVL in the Setting of Failed Bioprostheses Requiring Transcatheter Valve Therapy (Valve-In-Valve/Valve-In-Ring/TMVR)

8.6. When Transseptal Is Hostile: Transapical and Alternative Access (And when to Consider Them Early)

8.7. “Do not Confuse the Lesion”: Transvalvular Regurgitation, Leaflet Perforation, And Mixed Mechanisms

| Special scenario | Why it is different (pathophysiology/anatomy) | Best-practice strategy (what we do) | Red flags / when not to proceed | Imaging focus (must document) |

| Active infective endocarditis (IE) | Ongoing tissue destruction and unstable borders → device instability, recurrent dehiscence, embolic risk | Defer transcatheter PVL closure; Heart Team and guideline-directed IE management; consider catheter-based therapy only as exceptional palliative option after infection control | Persistent bacteremia/fever; uncontrolled infection; perivalvular extension (abscess, pseudoaneurysm, fistula) → usually surgical indication | TEE for dehiscence/abscess; CT/FDG-PET as indicated; document stability and absence of active infection signs |

| Healed/treated IE with pseudoaneurysm or fistula | Lesion behaves as tract communication rather than “simple PVL”; high-pressure gradients and complex geometry | Treat as structural tract closure; define entry/exit; consider staged/modular closure; prolonged follow-up | Uncertain infection status; fragile expanding pseudoaneurysm; inadequate landing zone | TEE + CT to delineate tract, neck, relation to coronaries/valve; document absence of active IE |

| Large circumferential dehiscence / “rocking” prosthesis | Primary issue is valve instability, not a discrete channel; plugs may not stabilize and may embolize | Generally surgical evaluation first; if prohibitive risk and selected anatomy, consider exceptional percutaneous modular strategy with strict stop criteria | Extensive dehiscence (e.g., >⅓ circumference), severe rocking, unstable borders → high failure/embolization risk | 3D TEE to quantify dehiscence extent and motion; CT for annular integrity; document stability after each device before release |

| Multiple PVLs / crescentic channel with multi-orifice exits | “One hole” concept fails; multiple jets may share a single tract; incomplete sealing common | Plan multi-device strategy; deploy first device to scaffold stable segment, then remap with 3D color and close residual exits | Oversizing one device causing hinge interference; accepting residual high-velocity micro-jet in hemolysis phenotype | 3D TEE en-face mapping and post-device residual mapping; CT for channel length/trajectory when complex |

| Hemolysis-dominant PVL (often mechanical valves) | Clinical failure can occur despite “mild” residual if micro-jet persists (high-shear physiology) | Endpoint = elimination of high-velocity residual jet; low threshold for second device if safe; track hemolysis labs and transfusion burden | Residual high-velocity jet; any leaflet restriction; inability to achieve stable seal | 3D TEE for precise micro-jet localization; standardized hemolysis labs pre/post; consider CMR in discordant cases |

| Mechanical prosthesis (mitral/aortic) | Catastrophic failure mode = disc/leaflet restriction | “Release discipline”: if any interference → immediate recapture; prefer lower-profile/morphology-matched modular closure | Any change in leaflet excursion/gradient; new transvalvular regurgitation → stop and revise | Continuous leaflet motion assessment + gradients during positioning; map PVL vs transvalvular jets |

| Post-TAVI PVL (PVR) | Multi-jet eccentric PVR; frame/calcification constraints; crossability often limiting | Optimize mechanism first (post-dilation/ViV if indicated); low-profile crossing strategy; aim reduction to mild or less | Predominantly transvalvular AR (leaflet dysfunction); unstable malposition requiring ViV; inability to cross safely | VARC-aligned grading; CT for trajectory/frame relation/coronaries; echo + hemodynamics as adjunct |

| Combined therapy (TMVR/ViV/ViR ± PVL closure) | Transcatheter valve can change PVL geometry; mixed mechanisms common | Unified CT-centric planning; decide staged vs same-session strategy; reassess PVL after valve therapy before committing to plugs | LVOT risk dominates strategy; uncertain landing zone; inability to maintain prosthesis function with added devices | CT for TMVR planning + PVL relation to frame; 3D TEE for residual mapping after valve implantation |

| Hostile transseptal route / alternative access needed | Septal closure device, thick septum, unfavorable LA geometry, extreme PVL trajectory | Define triggers for access change; consider transapical in selected mitral PVLs; consider alternative arterial access for aortic PVL | Excessive wire stiffness escalation; repeated uncontrolled prolapse; access trauma | CT/TEE to justify access choice and ensure coaxiality; document apical/vascular safety plan |

| Mixed mechanism regurgitation (PVL + transvalvular AR/MR, leaflet perforation, etc.) | Plugging PVL alone may not correct hemodynamics; can delay definitive therapy | Mandatory mechanism confirmation checkpoint; treat dominant mechanism first | Predominant transvalvular regurgitation; perforation/fistula not amenable to safe occlusion | ASE-guided differentiation PVL vs transvalvular; multimodality when discordant |

9. Outcome Evidence

10. Complications and Bailout Management in Transcatheter PVL Closure

10.1. How Often Do Major Complications Occur?

- Most commonly due to device protrusion into the prosthetic orifice, unfavorable orientation within an oblique/crescentic track, or deployment too atrial/ventricular relative to the sewing ring.

- Risk is particularly high in mechanical valves and in anatomies where the PVL channel courses near a hinge point. Leaflet restriction—particularly if intermittent—may precipitate abrupt hemodynamic deterioration, acute pulmonary edema, severe hemolysis, and/or cardiogenic shock. Accordingly, leaflet interaction should be considered a high-severity, preventable complication and should be explicitly surveilled and reported in procedural safety datasets [1].

- Avoid reliance on a single imaging plane: confirm leaflet excursion using multiple fluoroscopic projections and, for mitral PVL, immediate 3D TEE en-face assessment after partial and full deployment—prior to release.

- Prefer conformable/oblong occluder platforms for crescentic defects to minimize protrusion; avoid “oversizing for sealing” when it increases risk of orifice intrusion.

- In borderline cases, confirm hemodynamic and mechanical stability under physiologic stress (e.g., respiratory variation, pacing-induced tachycardia, and/or transient afterload augmentation) while the device remains attached, with the overarching principle of demonstrating stability and safety before release.

- Immediate recapture is the default strategy. If leaflet restriction resolves with repositioning, redeploy; if persistent, abort deployment and reassess device type, orientation strategy, and/or access route.

10.2.2. Acute or Delayed Device Embolization

-

Inadequate device purchase within the track (often due to undersizing), deployment in a short/irregular channel without stable anchoring, strong regurgitant forces, or release prior to definitive stability confirmation.

- Treat crescentic PVLs as modular sealing lesions: multiple smaller devices often provide more reliable anchoring than a single oversized device and may reduce protrusion risk.

- Perform a gentle stability (“tug”) assessment and confirm position in multiple imaging planes prior to release.

- Establish a predefined retrieval plan (including availability of snare systems and operator familiarity) before device release in cases with marginal anchoring.

- If attached: recapture and reposition/resize.

- If embolized: percutaneous retrieval with a snare when feasible; if retrieval is unsafe or risks major embolic injury or valve trauma, urgent surgical management may be required, emphasizing the need for Heart Team readiness in high-risk anatomies.

10.2.3. Stroke, systemic embolism, and air/thrombus events

- Thromboembolism related to wires/catheters, prosthetic surfaces, or device thrombosis (particularly if anticoagulation is interrupted).

- Air embolism during exchanges, device preparation, or inadequate flushing/de-airing.

-

Debris embolization when crossing calcified shelves or manipulating within a TAVI frame.

- Meticulous de-airing and continuous pressurized flushing of long sheaths and microcatheters; incorporate as a checklist item.

- Maintain adequate intraprocedural anticoagulation (center-specific ACT targets vary; the key principle is avoidance of subtherapeutic drift), and minimize dwell time of large-bore systems in low-flow chambers.

- Consider cerebral embolic protection selectively in high-risk anatomies (e.g., complex aortic/post-TAVI manipulation), acknowledging that evidence remains evolving.

- Immediate neurological assessment and activation of institutional stroke pathways. Avoid procedural escalation to chase residual PVL in the setting of an evolving neurological event unless hemodynamic instability mandates urgent action.

10.2.4. Access-site and vascular complications

- Large venous sheaths (transseptal mitral PVL), arterial access (retrograde aortic PVL), repeated exchanges, anticoagulation, and prolonged procedure duration.

- Ultrasound-guided access; consider percutaneous closure/preclose strategies for large-bore femoral access when appropriate.

- Avoid unnecessary sheath upsizing; use microcatheter-first crossing strategies to preserve the tract and reduce vascular trauma.

- Immediate angiography for suspected arterial injury; covered stent vs surgical repair guided by lesion type and hemodynamic stability. Reverse anticoagulation only when bleeding risk clearly outweighs device/valve thrombosis risk..

10.2.5. Cardiac structural injury: perforation, tamponade, and coronary complications

10.2.5.1. Pericardial effusion / tamponade

- Wire perforation (left atrium, left ventricle, aortic root), aggressive sheath advancement, or apical access injury. These events are included in prespecified adverse event frameworks and remain clinically relevant even in experienced centers [81].

- Enforce “soft-to-stiff” discipline: use hydrophilic crossing wires only as long as necessary, then exchange for controlled support wires once a stable track is established.

- Avoid deep sheath seating until rail stability and catheter course are unequivocally confirmed.

- Maintain pericardiocentesis readiness; adopt a low threshold for surgical escalation when bleeding persists, or hemodynamic compromise is ongoing.

10.2.5.2 Coronary dissection/ischemia

10.2.6. Conduction Disturbances and Arrhythmias

10.2.7. Hemolysis Persistence or Worsening After Closure

| Complication category | Typical mechanism(s) | Early warning sign(s) during the case | Prevention (operator habits) | Immediate bailout |

| Prosthetic leaflet impingement / prosthesis dysfunction | Device protrusion; unfavorable orientation; oversizing; hinge-point proximity | New gradient, hypotension, loss of leaflet excursion on fluoroscopy/TEE | Multi-view leaflet check before release; conformable devices; avoid “oversize to seal” | Recapture immediately; reposition/resize; abort if persistent |

| Device embolization (acute) | Undersizing; short/irregular channel; release without stability testing | Sudden loss of device position; hemodynamic change; new regurgitation | Tug test; confirm waist purchase; be liberal with multi-device strategies | Snare retrieval if safe; surgical escalation if not retrievable |

| Stroke / systemic embolism / air embolism | Thrombus/air; debris mobilization | Neuro deficit; sudden desaturation; coronary/cerebral signs | De-airing checklist; continuous flush; adequate ACT | Activate stroke pathway; stabilize; consider urgent imaging/intervention |

| Vascular/access complication | Large-bore sheath trauma; anticoagulation; prolonged procedure | Groin swelling, hypotension; falling Hb | Ultrasound guidance; preclose; minimize sheath upsizing | Angio/US diagnosis; covered stent/closure; transfuse as needed |

| Tamponade / perforation | Wire/sheath perforation; apical injury | Hypotension; echo effusion; rising pericardial pressure signs | Soft-to-stiff discipline; controlled sheath advancement | Pericardiocentesis; reverse anticoag selectively; surgery if ongoing bleed |

| Coronary dissection/ischemia (rare) | Catheter trauma in root/coronary ostia | ST changes; hypotension; angiographic injury | Gentle catheter work; avoid aggressive manipulation in root | Coronary wiring/stenting; surgical standby |

| Conduction disturbance | Septal tissue interaction; adjacent device pressure | New AV block; bradycardia | Avoid bulky protrusion near septum; monitor continuously | Temporary pacing; permanent device if persistent |

| Hemolysis persists/worsens | Residual high-velocity jet through small gap | Rising LDH; falling Hb; ongoing transfusion needs | Plan for multi-device sealing; target low residual grade in hemolysis cases | Re-intervene if anatomically feasible; reassess mechanism (jet, device position) |

11. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ACT | Activated clotting time |

| ADO | Amplatzer Duct Occluder |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AR | Aortic regurgitation |

| ARC | Academic Research Consortium |

| ASD | Atrial septal defect |

| ASE | American Society of Echocardiography |

| AV | Arteriovenous (e.g., AV rail) |

| AVP | Amplatzer Vascular Plug |

| AVR | Aortic valve replacement |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CHF | Congestive heart failure |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CW | Continuous-wave (Doppler) |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FFPP | European multicenter PVL registry (Feasibility, First-in-human, and Prospective PVL registry) |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HOLE | Spanish HOLE PVL registry |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICE | Intracardiac echocardiography |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IE | Infective endocarditis |

| JACC | Journal of the American College of Cardiology |

| KCCQ | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| LA | Left atrium |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| LVOT | Left ventricular outflow tract |

| MAC | Mitral annular calcification |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MLHFQ | Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire |

| MR | Mitral regurgitation |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association (functional class) |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PARADIGM | Multicenter PVL outcomes study (trial acronym) |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PISA | Proximal isovelocity surface area |

| EROA | Effective regurgitant orifice area |

| PLD | Occlutech Paravalvular Leak Device |

| PLUGinTAVI | International registry of post-TAVI PVL closure (PLUGinTAVI) |

| PVL | Paravalvular leak |

| PVR | Paravalvular regurgitation |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RA | Right atrium |

| RF | Regurgitant fraction |

| RV | Right ventricle |

| RVOT | Right ventricular outflow tract |

| SI | Surgical intervention |

| STOP | Standardized pre-release safety checklist (“STOP checks”) |

| TAVI | Transcatheter aortic valve implantation |

| TEE | Transesophageal echocardiography |

| THV | Transcatheter heart valve |

| TI | Transcatheter intervention |

| TMVR | Transcatheter mitral valve replacement |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiography |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| VARC-3 | Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 |

| VC | Vena contracta |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

References

- Cruz-Gonzalez, I.; Antunez-Muiños, P.; Lopez-Tejero, S.; Sanchez, P.L. Mitral Paravalvular Leak: Clinical Implications, Diagnosis and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Sandoval, J.; Unzue, L.; Hernández-Antolín, R.; Almería, C.; Macaya, C. Paravalvular leaks: Mechanisms, diagnosis and management. EuroIntervention 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouli, M.; Farooq, A.; Go, R.S.; Balla, S.; Berzingi, C. Cardiac prostheses-related hemolytic anemia. Clin. Cardiol. 2019, 42, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.J.; Hong, G.-R.; Han, K.; Im, D.J.; Chang, S.; Hong, Y.J.; et al. Assessment of Mitral Paravalvular Leakage After Mitral Valve Replacement Using Cardiac Computed Tomography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e004153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, M.; Ferrarese, S.; Cantore, C.; Massimi, G.; Facetti, S.; Mantovani, V.; et al. Early Aortic Paravalvular Leak After Conventional Cardiac Valve Surgery: A Single-Center Experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 109, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.N.; Orlov, O.I.; Orlov, C.P.; Buckley, M.; Sicouri, S.; Takebe, M.; et al. Incidence, Natural History, and Factors Associated With Paravalvular Leak Following Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Innov. (Phila) 2019, 14, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhout, I.; Mazine, A.; Ghoneim, A.; Millàn, X.; El-Hamamsy, I.; Pellerin, M.; et al. Long-term results after surgical treatment of paravalvular leak in the aortic and mitral position. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 151, 1260–1266.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoni, M.; Franzen, D.; Vogt, P.; Seifert, B.; Jenni, R.; Künzli, A.; et al. Paravalvular leakage after mitral valve replacement: Improved long-term survival with aggressive surgery? Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2000, 17, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.B.; Ahn, H. Paravalvular Leak After Mitral Valve Replacement: 20-Year Follow-Up. Ann Thorac Surg 2015, 100, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Umanzor, E.; Nogic, J.; Cepas-Guillén, P.; Hascoet, S.; Pysz, P.; Baz, J.A.; et al. Percutaneous paravalvular leak closure after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: The international PLUGinTAVI Registry. EuroIntervention 2023, 19, e442–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsalis, P.C.; Konorza, T.F.M.; Al-Rashid, F.; Plicht, B.; Riebisch, M.; Wendt, D.; et al. Incidence, outcome and correlates of residual paravalvular aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation and importance of haemodynamic assessment. EuroIntervention 2013, 8, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlawi, B.; Bedeir, K. Overcoming the transcatheter aortic valve replacement Achilles heel: Paravalvular leak. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 9, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, M.P.; Jacquemyn, X.; Van den Eynde, J.; Tasoudis, P.; Erten, O.; Sicouri, S.; et al. Impact of Paravalvular Leak on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Meta-Analysis of Kaplan-Meier-derived Individual Patient Data. Struct. Heart 2023, 7, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleid, M.F.; Cabalka, A.K.; Malouf, J.F.; Sanon, S.; Hagler, D.J.; Rihal, CS. Techniques and Outcomes for the Treatment of Paravalvular Leak. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, e001945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliger, C.; Eiros, R.; Isasti, G.; Einhorn, B.; Jelnin, V.; Cohen, H.; et al. Review of surgical prosthetic paravalvular leaks: Diagnosis and catheter-based closure. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 34, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürsoy, M.O.; Güner, A.; Kalçık, M.; Bayam, E.; Özkan, M. A comprehensive review of the diagnosis and management of mitral paravalvular leakage. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2020, 24, 350–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, C.E.; Hahn, R.T.; Berrebi, A.; Borer, J.S.; Cutlip, D.E.; Fontana, G.; et al. Clinical Trial Principles and Endpoint Definitions for Paravalvular Leaks in Surgical Prosthesis. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1224–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollari, F.; Dell'Aquila, A.M.; Söhn, C.; Marianowicz, J.; Wiehofsky, P.; Schwab, J.; et al. Risk factors for paravalvular leak after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 157, 1406–1415.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinning, J.-M.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Chin, D.; Hammerstingl, C.; Ghanem, A.; Bence, J.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Paravalvular Aortic Regurgitation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wely, M.; Rooijakkers, M.; Stens, N.; El Messaoudi, S.; Somers, T.; van Garsse, L.; et al. Paravalvular regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: Incidence, quantification, and prognostic impact. Eur. Heart J. - Imaging Methods Pract. 2024, 2, qyae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Wojtas, K.; Orciuch, W.; Jędrzejek, M.; Smolka, G.; Wojakowski, W.; et al. Potential Applications of Computational Fluid Dynamics for Predicting Hemolysis in Mitral Paravalvular Leaks. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtas, K.; Kozłowski, M.; Orciuch, W.; Makowski, Ł. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Mitral Paravalvular Leaks in Human Heart. Materials 2021, 14, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannata, A.; Cantoni, S.; Sciortino, A.; Bruschi, G.; Russo, CF. Mechanical Hemolysis Complicating Transcatheter Interventions for Valvular Heart Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigioni, M.; Daniele, C.; D'Avenio, G.; Barbaro, V. A discussion on the threshold limit for hemolysis related to Reynolds shear stress. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrzejczak, K.; Antonowicz, A.; Makowski, Ł.; Orciuch, W.; Wojtas, K.; Kozłowski, M. Computational fluid dynamics validated by micro particle image velocimetry to estimate the risk of hemolysis in arteries with atherosclerotic lesions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 196, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascoët, S.; Smolka, G.; Blanchard, D.; Kloëckner, M.; Brochet, E.; Bouisset, F.; et al. Predictors of Clinical Success After Transcatheter Paravalvular Leak Closure: An International Prospective Multicenter Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, e012193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberka, M.; Malczewska, M.; Pysz, P.; Kozłowski, M.; Wojakowski, W.; Smolka, G. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and transesophageal echocardiography in patients with prosthetic valve paravalvular leaks: Towards an accurate quantification and stratification. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2021, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, P.; Pibarot, P.; Chambers, J.; Edvardsen, T.; Delgado, V.; Dulgheru, R.; et al. Recommendations for the imaging assessment of prosthetic heart valves: A report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Chinese Society of Echocardiography, the Inter-American Society of Echocardiography, and the Brazilian Department of Cardiovascular Imaging†. Eur. Heart J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 589–590. [Google Scholar]

- Lerakis, S.; Hayek, S.; Arepalli, C.D.; Thourani, V.; Babaliaros, V. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance for Paravalvular Leaks in Post-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circulation 2014, 129, e430–e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, W.A.; Jone, P.N.; Chamsi-Pasha, M.A.; Chen, T.; Collins, K.A.; Desai, M.Y.; et al. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Prosthetic Valve Function With Cardiovascular Imaging: A Report From the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration With the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2024, 37, 2–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Généreux, P.; Piazza, N.; Alu Maria, C.; Nazif, T.; Hahn Rebecca, T.; et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. JACC 2021, 77, 2717–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P.; Hahn, R.T.; Weissman, N.J.; Monaghan, M.J. Assessment of Paravalvular Regurgitation Following TAVR: A Proposal of Unifying Grading Scheme. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biner, S.; Kar, S.; Siegel, R.J.; Rafique, A.; Shiota, T. Value of Color Doppler Three-Dimensional Transesophageal Echocardiography in the Percutaneous Closure of Mitral Prosthesis Paravalvular Leak. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafoor, S.; Steinberg, D.H.; Franke, J.; Bertog, S.C.; Vaskelyte, L.; Hofmann, I.; et al. Tools and Techniques - Clinical: Paravalvular leak closure. EuroIntervention 2014, 9, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanous, E.J.; Mukku, R.B.; Dave, P.; Aksoy, O.; Yang, E.H.; Benharash, P.; et al. Paravalvular Leak Assessment: Challenges in Assessing Severity and Interventional Approaches. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.; Tully, P.J.; Bennetts, J.; Sinhal, A.; Bradbrook, C.; Penhall, A.L.; et al. Quantitative assessment of paravalvular regurgitation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 17. [CrossRef]

- Frick, M.; Meyer, C.G.; Kirschfink, A.; Altiok, E.; Lehrke, M.; Brehmer, K.; et al. Evaluation of aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Aortic root angiography in comparison to cardiac magnetic resonance. EuroIntervention 2016, 11, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.B.; Orwat, S.; Hayek, S.S.; Larose, É.; Babaliaros, V.; Dahou, A.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance to Evaluate Aortic Regurgitation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghani, M.; Tateishi, H.; Spitzer, E.; Tijssen, J.G.; de Winter, R.J.; Soliman, O.I.I.; et al. Echocardiographic and angiographic assessment of paravalvular regurgitation after TAVI: Optimizing inter-technique reproducibility. Eur. Heart J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kawashima, H.; Mylotte, D.; Rosseel, L.; Gao, C.; Aben, J.P.; et al. Quantitative Angiographic Assessment of Aortic Regurgitation After Transcatheter Implantation of the Venus A-valve: Comparison with Other Self-Expanding Valves and Impact of a Learning Curve in a Single Chinese Center. Glob. Heart 2021, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Abdelghani, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; Holy Erik, W.; Merten, C.; Zachow, D.; et al. A Novel Angiographic Quantification of Aortic Regurgitation After TAVR Provides an Accurate Estimation of Regurgitation Fraction Derived From Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Recalde, A.; Moreno, R.; Galeote, G.; Jimenez-Valero, S.; Calvo, L.; Sevillano, J.H.; et al. Immediate and mid-term clinical course after percutaneous closure of paravalvular leakage. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 67, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.I.; Braga, P.; Rodrigues, A.; Santos, L.; Melica, B.; Ribeiro, J.; et al. Percutaneous closure of periprosthetic paravalvular leaks: A viable alternative to surgery? Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2017, 36, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burriesci, G.; Peruzzo, P.; Susin, F.M.; Tarantini, G.; Colli, A. In vitro hemodynamic testing of Amplatzer plugs for paravalvular leak occlusion after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol 2016, 203, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis, V.J.; Swaans, M.J.; Post, M.C.; Heijmen, R.H.; de Kroon, T.L.; ten Berg, J.M. Open Transapical Approach to Transcatheter Paravalvular Leakage Closure. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 7, 611–620. [CrossRef]

- Onorato, E.M.; Muratori, M.; Smolka, G.; Malczewska, M.; Zorinas, A.; Zakarkaite, D.; et al. Midterm procedural and clinical outcomes of percutaneous paravalvular leak closure with the Occlutech Paravalvular Leak Device. EuroIntervention 2020, 15, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, G.; Pysz, P.; Kozłowski, M.; Jasiński, M.; Gocoł, R.; Roleder, T.; et al. Transcatheter closure of paravalvular leaks using a paravalvular leak device - a prospective Polish registry. Postep. Kardiol. Interwencyjnej 2016, 12, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Onorato, E.M.; Alamanni, F.; Muratori, M.; Smolka, G.; Wojakowski, W.; Pysz, P.; et al. Safety, Efficacy and Long-Term Outcomes of Patients Treated with the Occlutech Paravalvular Leak Device for Significant Paravalvular Regurgitation. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gonzalez, I.; Rama-Merchan, J.C.; Arribas-Jimenez, A.; Rodriguez-Collado, J.; Martin-Moreiras, J.; Cascon-Bueno, M.; et al. Paravalvular leak closure with the Amplatzer Vascular Plug III device: Immediate and short-term results. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 67, 608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Hascoët, S.; Smolka, G.; Kilic, T.; Ibrahim, R.; Onorato, E.-M.; Calvert, P.A.; et al. Procedural Tools and Technics for Transcatheter Paravalvular Leak Closure: Lessons from a Decade of Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percutaneous closure of paravalvular aortic leaks with the Amplatzer Vascular Plug III ®, late clinical follow-up. EuroIntervention 8(Q).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Prospective M, Single-Arm Study to Evaluate the Safety and Effectiveness of the Amplatzer Valvular Plug III in Patients With Paravalvular Leak (PARADIGM). NCT04489823. Updated Month Day, Year. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04489823.

- Sagar, P.; Pavithran, S.; Rajendran, M.; Sivakumar, K. Single center experience of transcatheter closure of mitral and aortic Paravalvular leaks using the new rechristened rectangular Amplatzer PVL plug. Indian. Heart J. 2022, 74, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyisoy, A.; Kursaklioglu, H.; Celik, T.; Baysan, O.; Celik, M. Percutaneous closure of a tricuspid paravalvular leak with an Amplatzer duct occluder II via antegrade approach. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2011, 22, e7–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursaklioglu, H.; Barcin, C.; Iyisoy, A.; Baysan, O.; Celik, T.; Kose, S. Percutaneous closure of mitral paravalvular leak via retrograde approach: With use of the Amplatzer duct occluder II and without a wire loop. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2010, 37, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa, M. Percutaneous closure of prosthetic paravalvular leaks – Should it be considered the first therapeutic option? Rev. Port. De Cardiol. (Engl. Ed. ) 2017, 36, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gonzalez, I.; Rama-Merchan, J.C.; Rodríguez-Collado, J.; Martín-Moreiras, J.; Diego-Nieto, A.; Barreiro-Pérez, M.; et al. Transcatheter closure of paravalvular leaks: State of the art. Neth. Heart J. 2017, 25, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.; Basmadjian, A.; Ibrahim, R. Transcatheter Prosthetic Paravalvular Leak Closure. Cardiovasc. Med. 2012, 15, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; de Waha, S.; Bonaros, N.; Brida, M.; Burri, H. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis: Developed by the task force on the management of endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maskari, S.; Panduranga, P.; Al-Farqani, A.; Thomas, E.; Velliath, J. Percutaneous closure of complex paravalvular aortic root pseudoaneurysm and aorta-cavitary fistulas. Indian. Heart J. 2014, 66, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Khan, J.N.; Hildick-Smith, D.; Been, M. Percutaneous device closure of a large complex aortic root pseudoaneurysm. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorato, E.M.; Vercellino, M.; Masoero, G.; Monizzi, G.; Sanchez, F.; Muratori, M.; et al. Catheter-based Closure of a Post-infective Aortic Paravalvular Pseudoaneurysm Fistula With Severe Regurgitation After Two Valve Replacement Surgeries: A Case Report. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 693732. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, F.E., Iii; Iturbe, J.M.; Lerakis, S.; Kamioka, N.; Babaliaros, V.C.; Clements, S.D. Percutaneous Closure of Paravalvular Leak from a Rocking Mitral Valve in a 74-Year-Old Man at High Surgical Risk. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2020, 47, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihal Charanjit, S.; Sorajja, P.; Booker Jeffrey, D.; Hagler Donald, J.; Cabalka, A. l.l.i.s.o.n K. Principles of Percutaneous Paravalvular Leak Closure. JACC: Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 5, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beneduce, A.; Ancona, M.B.; Russo, F.; Ferri, L.A.; Bellini, B.; Vella, C.; et al. Transcatheter Mitral Paravalvular Leak Closure Using Arteriovenous Rail Across Aortic Bileaflet Mechanical Prosthesis: Multimodality Imaging Approach. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, e014267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asami, M.; Pilgrim, T.; Windecker, S.; Praz, F. Case report of simultaneous transcatheter mitral valve-in-valve implantation and percutaneous closure of two paravalvular leaks. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2019, 3, ytz123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, E.; Unzué, L.; Almería, C.; Cruz, I.; Nombela, L.; Jiménez-Quevedo, P. Combined Percutaneous Mitral Valve Implantation and Paravalvular Leak Closure in a High-risk Patient With Severe Mitral Regurgitation. Rev. Española De Cardiol. (Engl. Ed. ) 2015, 68, 1053–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; Kaple, R.K.; Mehta, H.H.; Singh, P.; Bapat, V.N. Current state of transcatheter mitral valve implantation in bioprosthetic mitral valve and in mitral ring as a treatment approach for failed mitral prosthesis. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 10, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sayan, E.; Chen, T.; Khalique, O.K. Multimodality Cardiac Imaging for Procedural Planning and Guidance of Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement and Mitral Paravalvular Leak Closure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurent, G.; Galli, E.; Le Breton, H.; Auffret, V. Percutaneous closure of paravalvular leak after transcatheter valve implantation in mitral annular calcification. EuroIntervention 2020, 15, 1518–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, M.; Yuksel, U.C. Percutaneous transapical closure of paravalvular leak in bioprosthetic mitral valve without radio-opaque indicators. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, J.M.; Rosenberg, J.; Lang, R.M.; Shah, A.P. Transapical Access for Percutaneous Mitral Paravalvular Leak Repair. Struct. Heart 2017, 1, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Lv, J.-H.; Hu, H.-B.; Xie, R.-G.; Jin, Q.; et al. Transbrachial Access for Transcatheter Closure of Paravalvular Leak Following Prosthetic Valve Replacement. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang Qi, X.; Panama, G.; Salam Mohammad, S.; Siddiqi, Z.; Srivastava, S.; Qintar, M. Transcatheter Repair of Mitral Valve Leaflet Perforation Using Occluder Plug. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouli, M.; Zack, C.J.; Sarraf, M.; Eleid, M.F.; Cabalka, A.K.; Reeder, G.S.; et al. Successful Percutaneous Mitral Paravalvular Leak Closure Is Associated With Improved Midterm Survival. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, X.; Skaf, S.; Joseph, L.; Ruiz, C.; García, E.; Smolka, G.; et al. Transcatheter reduction of paravalvular leaks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2015, 31, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belahnech, Y.; Aguasca, G.M.; García Del Blanco, B.; Ródenas-Alesina, E.; González Alujas, T.; Gutiérrez García-Moreno, L.; et al. Impact of a Successful Percutaneous Mitral Paravalvular Leak Closure on Long-term Major Clinical Outcomes. Can. J. Cardiol. 2024, 40, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busu, T.; Alqahtani, F.; Badhwar, V.; Cook, C.C.; Rihal, C.S.; Alkhouli, M. Meta-analysis Comparing Transcatheter and Surgical Treatments of Paravalvular Leaks. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.; At Condado, J.F.; Kamioka, N.; Dong, A.; Ritter, A.; Lerakis, S.; et al. Outcomes After Paravalvular Leak Closure: Transcatheter Versus Surgical Approaches. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 500–507. [CrossRef]

- Improta, R.; Di Pietro, G.; Odeh, Y.; Morena, A.; Saade, W.; D'Ascenzo, F.; et al. Transcatheter or surgical treatment of paravalvular leaks: A meta-analysis of 13 studies and 2003 patients. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2025, 56, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, E.; Arzamendi, D.; Jimenez-Quevedo, P.; Sarnago, F.; Martí, G.; Sanchez-Recalde, A.; et al. Outcomes and predictors of success and complications for paravalvular leak closure: An analysis of the SpanisH real-wOrld paravalvular LEaks closure (HOLE) registry. EuroIntervention 2017, 12, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, P.A.; Northridge, D.B.; Malik, I.S.; Shapiro, L.; Ludman, P.; Qureshi, S.A.; et al. Percutaneous Device Closure of Paravalvular Leak: Combined Experience From the United Kingdom and Ireland. Circulation 2016, 134, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).