Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Methods

3. Association between MON and GON

4. Rationale for considering non-glaucomatous nerve damage: evidence from experimental studies.

5. Is myopia a risk factor for visual field progression?

6. Myopic deformations of the optic disc and its association with visual functions.

6.1. Optic disc morphology

6.1.1. Optic disc size

6.1.2. Effects of optic disc tilting on nerve damage

6.1.3. Ovality index

6.1.4. Torsion or rotation of the optic disc

6.1.5. Congenital anomalies, hypoplasia and high myopia

7. Elongation of papillomacular distance

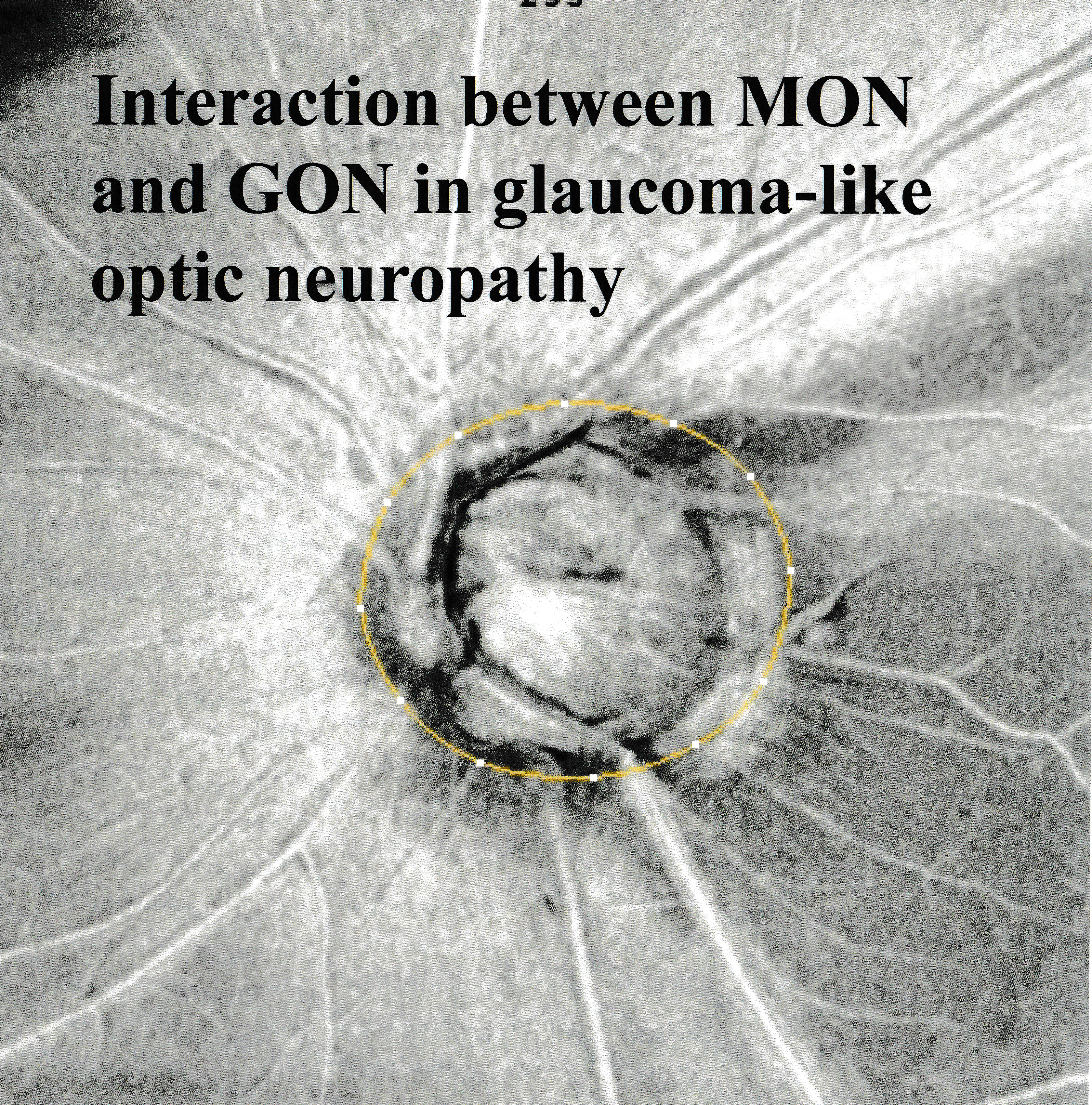

8. Abnormal lamina cribrosa (LC) and cup of the disc

8.1. Lamina cribrosa defects (LCDs)

8.2. Thin LC

8.3. Excavation and LC depth.

9. Parapapillary changes

9.1. Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO)

9.2. Intrachoroidal cavitation (ICC):

9.3. Parapapillary choroidal atrophy (PPA)

9.4. Parapapillary scleral ridge and abnormalities at the optic disc margin that may affect RNFLDs in myopic eyes.

10. Position of vascular trunk.

11.. Retinal nerve fiber layer in myopic eyes.

11.1. Cleavage of the retinal nerve fiber layer

11.2. Peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures (PHOMS)

12. Vascular anomaly and vulnerability of the retinal nerve fiber layer.

12.1. Microvasculature dropout (MvD)

12.2. Choroidal thickness

12.3 macular capillary density

13. Special type of VFD (central visual field defects) and associated factors.

14.. Differentiation of MON and GON

15. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MON | Myopic optic neuropathy |

| GON | Glaucomatous optic neuropathy |

| VF | Visual field |

| VFD | Visual field defect |

| BMO | Bruch’s membrane opening |

| POAG | Primary open angle glaucoma |

| OAG | Open angle glaucoma |

| NTG | Normal tension glaucoma |

| LC | Lamina cribrosa |

| LCD | Lamina cribrosa defect |

| ICC | Intrachoroidal cavitation |

| NFL | Nerve fiber layer |

| RNFLD | Retinal nerve fiber layer defect |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| MvD | Microvascular dropout |

| pMvD | Parapapillary microvascular dropout |

| PPA | Parapapillary choroidal atrophy |

| ONH | Optic nerve head |

| PHOMS | Peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

References

- Chihara, E.; Tanihara, H. Parameters associated with papillomacular bundle defects in glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992, 230, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Hangai, M.; Morooka, S.; Takayama, K.; Nakano, N.; Nukada, M.; Ikeda, H.O.; Akagi, T.; Yoshimura, N. Retinal nerve fiber layer defects in highly myopic eyes with early glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012, 53, 6472–6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayama, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Araie, M.; Ishida, K.; Akira, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kitazawa, Y.; Funaki, S.; Shirakashi, M.; Abe, H.; et al. Myopia and advanced-stage open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.G.; Shin, Y.I.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, K.H.; Jeoung, J.W. Long-Term Follow-Up of Myopic Glaucoma: Progression Rates and Associated Factors. J Glaucoma 2024, 33, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E.; Sawada, A. Atypical nerve fiber layer defects in high myopes with high-tension glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990, 108, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, C.K.; Jung, K.I. Characteristics of progressive temporal visual field defects in patients with myopia. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Xiong, R.; Liu, R.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, S.; He, M.; Wang, W. Long-Term Prediction and Risk Factors for Incident Visual Field Defect in Nonpathologic High Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024, 65, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, X.; Wang, P.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Classification of Visual Field Abnormalities in Highly Myopic Eyes without Pathologic Change. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.R.; Hendrickson, A. Effect of intraocular pressure on rapid axoplasmic transport in monkey optic nerve. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974, 13, 771–783. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, H.A.; Hohman, R.M.; Addicks, E.M.; Massof, R.W.; Green, W.R. Morphologic changes in the lamina cribrosa correlated with neural loss in open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983, 95, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakugawa, M.; Chihara, E. Blockage at two points of axonal transport in glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985, 223, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, E.; Honda, Y. Analysis of orthograde fast axonal transport and nonaxonal transport along the optic pathway of albino rabbits during increased and decreased intraocular pressure. Exp Eye Res. 1981, 32, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunt-Milam, A.H.; Dennis, M.B., Jr.; Bensinger, R.E. Optic nerve head axonal transport in rabbits with hereditary glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 1987, 44, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Song, Y.; Kong, K.; Wang, P.; Lin, F.; Gao, X.; Wang, Z.; Jin, L.; Chen, M.; Lam, D.S.C.; et al. Optic Nerve Head Abnormalities in Nonpathologic High Myopia and the Relationship With Visual Field. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2023, 12, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Panda-Jonas, S. Clinical and histological aspects of the anatomy of myopia, myopic macular degeneration and myopia-associated optic neuropathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2025, 109, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.X. Prevalence and Cause of Loss of Visual Acuity and Visual Field in Highly Myopic Eyes: The Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Dong, L.; Panda-Jonas, S. High Myopia and Glaucoma-Like Optic Neuropathy. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2020, 9, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, A.; Kreidl, K.O.; Lombardi, L.; Sakamoto, D.K.; Singh, K. Nonprogressive glaucomatous cupping and visual field abnormalities in young Chinese males. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Bikbov, M.M.; Kazakbaeva, G.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Nangia, V.; Milea, D.; Lamirel, C.; Jonas, R.A.; Panda-Jonas, S. Glaucomatous, Glaucoma-Like, and Non-Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy in High Myopia: The Two-Continent Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025, 66, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Jung, Y.; Park, C.K. Vertical disc tilt and features of the optic nerve head anatomy are related to visual field defect in myopic eyes. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Yan, Y.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, W.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Wang, Y.X. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in association with gamma zone width and disc-fovea distance. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.; Hourihan, F.; Sandbach, J.; Wang, J.J. The relationship between glaucoma and myopia: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1999, 106, 2010–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, R.; Scheetz, J.; Xiao, O.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Guo, X.; Jong, M.; Sankaridurg, P.; et al. Distribution of intraocular pressure and related risk factors in a highly myopic Chinese population: an observational, cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Optom. 2021, 104, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Patel, D.; Prajapati, V.; Patil, M.S.; Singhal, D. A Study on the Association Between Myopia and Elevated Intraocular Pressure Conducted at a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Gujarat, India. Cureus 2022, 14, e28128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Gusek, G.C.; Naumann, G.O. Optic disk morphometry in high myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988, 226, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mi, B.; Li, H.; Du, B.; Liu, L.; Xing, X.; Lam, A.K.; To, C.H.; Wei, R. Thinning of the Lamina Cribrosa and Deep Layer Microvascular Dropout in Patients With Open Angle Glaucoma and High Myopia. J Glaucoma 2023, 32, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Dou, R.; Wang, Y. Comparison of Corneal Biomechanics Between Low and High Myopic Eyes-A Meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019, 207, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Aung, T.; Bourne, R.R.; Bron, A.M.; Ritch, R.; Panda-Jonas, S. Glaucoma. Lancet 2017, 390, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grødum, K.; Heijl, A.; Bengtsson, B. Refractive error and glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001, 79, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Nirmalan, P.K.; Krishnadas, R.; Thulasiraj, R.D.; Tielsch, J.M.; Katz, J.; Friedman, D.S.; Robin, A.L. Glaucoma in a rural population of southern India: the Aravind comprehensive eye survey. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Iwase, A.; Araie, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Abe, H.; Shirato, S.; Kuwayama, Y.; Mishima, H.K.; Shimizu, H.; Tomita, G.; et al. Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma in a Japanese population: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casson, R.J.; Gupta, A.; Newland, H.S.; McGovern, S.; Muecke, J.; Selva, D.; Aung, T. Risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma in a Burmese population: the Meiktila Eye Study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007, 35, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jonas, J.B. High myopia and glaucoma susceptibility the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, S.A.; Wong, T.Y.; Tay, W.T.; Foster, P.J.; Saw, S.M.; Aung, T. Refractive error, axial dimensions, and primary open-angle glaucoma: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, D.I.; Edussuriya, K.; Sennanayake, S.; Senaratne, T.; Selva, D.; Casson, R.J. Prevalence of and risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma in central Sri Lanka: the Kandy eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010, 17, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.B.; Friedman, D.S.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, X.; Sun, L.P.; Guo, L.X.; Tao, Q.S.; Chang, D.S.; Wang, N.L. Prevalence of primary open angle glaucoma in a rural adult Chinese population: the Handan eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011, 52, 8250–8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.W.; de Vries, M.M.; Junoy Montolio, F.G.; Jansonius, N.M. Myopia as a risk factor for open-angle glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1989–1994.e1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Singh, K.; Lin, S.C. Association between myopia and glaucoma in the United States population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013, 54, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leske, M.C.; Nemesure, B.; He, Q.; Wu, S.Y.; Fielding Hejtmancik, J.; Hennis, A. Patterns of open-angle glaucoma in the Barbados Family Study. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Budde, W.M. Optic nerve damage in highly myopic eyes with chronic open-angle glaucoma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005, 15, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrone, C.; Mancino, R.; Ricci, F.; Cerulli, A.; Culasso, F.; Nucci, C. The 12-year incidence of glaucoma and glaucoma-related visual field loss in Italy: the Ponza eye study. J Glaucoma 2012, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Burkemper, B.; Pardeshi, A.A.; Apolo, G.; Richter, G.; Jiang, X.; Torres, M.; McKean-Cowdin, R.; Varma, R.; Xu, B.Y. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Roles of Myopia and Ocular Biometrics as Risk Factors for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023, 64, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Yoshida, T.; Sugisawa, K.; Yoshimoto, S.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Interplay Between γ-Zone Peripapillary Atrophy and Optic Disc Parameters in Central Visual Field Impairment in Highly Myopic Eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025, 66, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiravarnsirikul, A.; Belghith, A.; Rezapour, J.; Micheletti, E.; Nishida, T.; Moghimi, S.; Suh, M.H.; Jonas, J.B.; Walker, E.; Christopher, M.; et al. Relationship of 24-2C Central Visual Field Damage to Juxtapapillary Choriocapillaris Dropout in Glaucoma Eyes With or Without Axial Myopia. J Glaucoma 2025, 34, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, K.; Han, J.C.; Kee, C. Different glaucoma progression rates by age groups in young myopic glaucoma patients. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Han, S.H.; Park, D.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Kee, C. Clinical Course and Risk Factors for Visual Field Progression in Normal-Tension Glaucoma With Myopia Without Glaucoma Medications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020, 209, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shin, Y.I.; Huh, M.G.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H. Rate of Progression Among Different Age Groups in Glaucoma With High Myopia: A 10-Year Follow-Up Cohort Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025, 276, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasty, U.; Harris, A.; Siesky, B.; Rowe, L.W.; Verticchio Vercellin, A.C.; Mathew, S.; Pasquale, L.R. Optic disc haemorrhage and primary open-angle glaucoma: a clinical review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, G.; Andreanos, D.; Liokis, N.; Papakonstantinou, D.; Vergados, J.; Theodossiadis, G. Risk factors in ocular hypertension. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997, 7, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Jin, J.J.; Ha, A.; Song, C.H.; Park, S.H.; Kang, K.H.; Lee, J.; Huh, M.G.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H.; et al. SMOTE-Enhanced Explainable Artificial Intelligence Model for Predicting Visual Field Progression in Myopic Normal Tension Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2025, 34, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernest, P.J.; Schouten, J.S.; Beckers, H.J.; Hendrikse, F.; Prins, M.H.; Webers, C.A. An evidence-based review of prognostic factors for glaucomatous visual field progression. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, H.A.; Enger, C.; Katz, J.; Sommer, A.; Scott, R.; Gilbert, D. Risk factors for the development of glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994, 112, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.L.; Hong, K.E.; Park, C.K. Impact of Age and Myopia on the Rate of Visual Field Progression in Glaucoma Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czudowska, M.A.; Ramdas, W.D.; Wolfs, R.C.; Hofman, A.; De Jong, P.T.; Vingerling, J.R.; Jansonius, N.M. Incidence of glaucomatous visual field loss: a ten-year follow-up from the Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.T.; Almeida, I.; Sassaki, A.M.; Juncal, V.R.; Ushida, M.; Lopes, F.S.; Alhadeff, P.; Ritch, R.; Prata, T.S. Factors associated with the presence of parafoveal scotoma in glaucomatous eyes with optic disc hemorrhages. Eye (Lond) 2018, 32, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Zhou, N.; Yoshimoto, S.; Sugisawa, K.; Ohno, M.; Yasuda, S.; Shiotani, Y.; Teramatsu, R.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Efficacy of Filtration Surgery and Risk Factors for Central Visual Field Deterioration in Highly Myopic Eyes With Open Angle Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2025, 34, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Jonas, S.B.; Panda-Jonas, S. Myopia and Other Refractive Error and Their Relationships to Glaucoma Screening. J Glaucoma 2024, 33, S45–s48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.B.; Da Chen, S.; Song, Y.H.; Wang, W.; Jin, L.; Liu, B.Q.; Liu, Y.H.; Chen, M.L.; Gao, K.; Friedman, D.S.; et al. Effect of medically lowering intraocular pressure in glaucoma suspects with high myopia (GSHM study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Chen, R.I.; Lin, S.C. Myopia and glaucoma: sorting out the difference. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015, 26, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, B.R.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H. Glaucoma Detection Ability of Macular Ganglion Cell-Inner Plexiform Layer Thickness in Myopic Preperimetric Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 8306–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makashova, N.V.; Eliseeva, E.G. Relationship of changes in visual functions and optic disk in patients with glaucoma concurrent with myopia. Vestn Oftalmol. 2007, 123, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.T.; Singh, K. Myopia and glaucoma: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013, 24, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Yoo, B.W.; Jeoung, J.W.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, H.J.; Park, K.H. Glaucoma-Diagnostic Ability of Ganglion Cell-Inner Plexiform Layer Thickness Difference Across Temporal Raphe in Highly Myopic Eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016, 57, 5856–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.; Belliveau, A.C.; Sharpe, G.P.; Shuba, L.M.; Chauhan, B.C.; Nicolela, M.T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Optical Coherence Tomography and Scanning Laser Tomography for Identifying Glaucoma in Myopic Eyes. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.L.; Kumar, A.U.; Bonala, S.R.; Yogesh, K.; Lakshmi, B. Repeatability of Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Measurements in High Myopia. J Glaucoma 2016, 25, e526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Park, K.H. Diagnostic Accuracy of Three-Dimensional Neuroretinal Rim Thickness for Differentiation of Myopic Glaucoma From Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018, 59, 3655–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowd, C.; Belghith, A.; Rezapour, J.; Christopher, M.; Jonas, J.B.; Hyman, L.; Fazio, M.A.; Weinreb, R.N.; Zangwill, L.M. Multimodal Deep Learning Classifier for Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Diagnosis Using Wide-Field Optic Nerve Head Cube Scans in Eyes With and Without High Myopia. J Glaucoma 2023, 32, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.P.H.; Radke, N.V.; Chan, P.P.; Tham, C.C.; Lam, D.S.C. Standardization of High Myopia Optic Nerve Head Abnormalities May Help Diagnose Glaucoma in High Myopia. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2023, 12, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Lin, P.W.; Wu, P.C. The Prevalence of Optical Coherence Tomography Artifacts in High Myopia and its Influence on Glaucoma Diagnosis. J Glaucoma 2023, 32, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.T.; Tran, M.; Singh, K.; Chang, R.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. Glaucoma and Myopia: Diagnostic Challenges. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Jia, J.; Shi, R.; Liu, Y.; Shu, Q.; Lu, F.; Ge, T.; He, Y. Progress in clinical characteristics of high myopia with primary open-angle glaucoma. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2024, 40, 4923–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezapour, J.; Walker, E.; Belghith, A.; Bowd, C.; Fazio, M.A.; Jiravarnsirikul, A.; Hyman, L.; Jonas, J.B.; Weinreb, R.N.; Zangwill, L.M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Optic Nerve Head and Macula OCT Parameters for Detecting Glaucoma in Eyes With and Without High Axial Myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024, 266, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Kong, K.; Li, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, P.; Song, Y.; Lin, F.; Lin, T.P.H.; Zangwill, L.M.; et al. Optic neuropathy in high myopia: Glaucoma or high myopia or both? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2024, 99, 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, M.; Hu, L.; Han, W.; Zuo, C.; Li, Z.; Xiao, H.; Huang, S.; et al. Detecting Glaucoma in Highly Myopic Eyes From Fundus Photographs Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025, 53, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiravarnsirikul, A.; Belghith, A.; Rezapour, J.; Bowd, C.; Moghimi, S.; Jonas, J.B.; Christopher, M.; Fazio, M.A.; Yang, H.; Burgoyne, C.F.; et al. Evaluating glaucoma in myopic eyes: Challenges and opportunities. Surv Ophthalmol. 2025, 70, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Sung, K.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.M. Implications of Optic Disc Tilt in the Progression of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 6925–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Araie, M.; Shibata, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Iwata, T.; Yoshitomi, T. Optic Disc Margin Anatomic Features in Myopic Eyes with Glaucoma with Spectral-Domain OCT. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.C.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.X.; Jonas, J.B. Parapapillary gamma zone associated with increased peripapillary scleral bowing: the Beijing Eye Study 2011. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023, 107, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Xu, J.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.X. Prevalence and associations of parapapillary scleral ridges: the Beijing Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2025, 109, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Yonekawa, Y.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Cohen, S.Y.; Rowland, C.; Pulido, J.S. RIDGE-SHAPED PERIPAPILLA. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2024, 18, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, I.C.; Shimada, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Nagaoka, N.; Moriyama, M.; Yoshida, T.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Comparison of Clinical Features in Highly Myopic Eyes with and without a Dome-Shaped Macula. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1591–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, F.; Ten, W.; Jin, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ke, B. In vivo assessment of regional scleral stiffness by shear wave elastography and its association with choroid and retinal nerve fiber layer characteristics in high myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzin, A.A.; Varma, R.; Reddy, H.S.; Torres, M.; Azen, S.P. Ocular biometry and open-angle glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, B.; Qiu, M.; Lin, S.C. Myopia and glaucoma in the South Korean population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013, 54, 6570–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyo-Berríos, N.I.; Blustein, J.N. Primary-open glaucoma and myopia: a narrative review. Wmj 2007, 106, 85–89, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.J.; Lu, P.; Zhang, W.F.; Lu, J.H. High myopia as a risk factor in primary open angle glaucoma. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012, 5, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, L.; Rashima, A.; Panday, M.; Choudhari, N.S.; Ramesh, S.V.; Lokapavani, V.; Boddupalli, S.D.; Sunil, G.T.; George, R. Predictors for incidence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a South Indian population: the Chennai eye disease incidence study. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.W.; Lan, Y.W.; Hsieh, J.W. The Optic Nerve Head in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Eyes With High Myopia: Characteristics and Association With Visual Field Defects. J Glaucoma 2016, 25, e569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, J.; Goldberg, I.; Graham, S.L. Analysis of risk factors that may be associated with progression from ocular hypertension to primary open angle glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002, 30, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E.; Liu, X.; Dong, J.; Takashima, Y.; Akimoto, M.; Hangai, M.; Kuriyama, S.; Tanihara, H.; Hosoda, M.; Tsukahara, S. Severe myopia as a risk factor for progressive visual field loss in primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 1997, 211, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.A.; Shih, Y.F.; Lin, L.L.; Huang, J.Y.; Wang, T.H. Association between high myopia and progression of visual field loss in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008, 107, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, A.; Mahalingam, K.; Selvan, H.; Gupta, P.; Pandey, S.; Somarajan, B.I.; Gupta, V. Myopia and glaucoma progression among patients with juvenile onset open angle glaucoma: A retrospective follow up study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2021, 41, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Ahn, E.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Ha, A.; Kim, Y.K.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H. Impact of myopia on the association of long-term intraocular pressure fluctuation with the rate of progression in normal-tension glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaoka, R.; Sakata, R.; Yoshitomi, T.; Iwase, A.; Matsumoto, C.; Higashide, T.; Shirakashi, M.; Aihara, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Araie, M. Differences in Factors Associated With Glaucoma Progression With Lower Normal Intraocular Pressure in Superior and Inferior Halves of the Optic Nerve Head. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2023, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Kong, K.; Lin, F.; Zhou, F.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, Z.; Xiaokaiti, D.; Jin, L.; Chen, M.; et al. Longitudinal Changes of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer and Ganglion Cell-Inner Plexiform Layer in Highly Myopic Glaucoma: A 3-Year Cohort Study. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Chuang, L.H.; Lai, C.C.; Liu, C.F.; Yang, J.W.; Chen, H.S.L. Longitudinal changes in optical coherence tomography angiography characteristics in normal-tension glaucoma with or without high myopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, e762–e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.G.; Jeong, Y.; Shin, Y.I.; Kim, Y.K.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H. Assessing Glaucoma Severity and Progression in Individuals with Asymmetric Axial Length: An Intrapatient Comparative Study. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ning, K.; He, M.; Huang, W.; Wang, W. Myopia and Rate of Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Diabetic Patients Without Retinopathy: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Curr Eye Res. 2024, 49, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.W.; Song, J.S.; Kee, C. Influence of the extent of myopia on the progression of normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araie, M.; Shirato, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Matsumoto, C.; Kitazawa, Y.; Ohashi, Y. Risk factors for progression of normal-tension glaucoma under β-blocker monotherapy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 90, e337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springelkamp, H.; Wolfs, R.C.; Ramdas, W.D.; Hofman, A.; Vingerling, J.R.; Klaver, C.C.; Jansonius, N.M. Incidence of glaucomatous visual field loss after two decades of follow-up: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.R.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Back, S.; Lee, K.S.; Kook, M.S. Is Myopic Optic Disc Appearance a Risk Factor for Rapid Progression in Medically Treated Glaucomatous Eyes With Confirmed Visual Field Progression? J Glaucoma 2016, 25, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.H.; Cheng, C.Y.; Liu, C.J. Risk factors for predicting visual field progression in Chinese patients with primary open-angle glaucoma: A retrospective study. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015, 78, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, T.; Yoshikawa, K.; Mizoue, S.; Nanno, M.; Kimura, T.; Suzumura, H.; Umeda, Y.; Shiraga, F. Relationship between visual field progression and baseline refraction in primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, T.; Fukuchi, T.; Togano, T.; Sakaue, Y.; Seki, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ueda, J. Rate of progression of total, upper, and lower visual field defects in patients with open-angle glaucoma and high myopia. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2016, 60, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Qian, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Meng, F. Axial Myopia Is Associated with Visual Field Prognosis of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Sung, K.R.; Han, S.; Na, J.H. Effect of myopia on the progression of primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hao, J.; Du, Y.; Cao, K.; Lin, C.; Sun, R.; Xie, Y.; Wang, N. The Association between Myopia and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic Res. 2022, 65, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, M.M.; Iakupova, E.M.; Gilmanshin, T.R.; Bikbova, G.M.; Kazakbaeva, G.M.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Gilemzianova, L.I.; Jonas, J.B. Prevalence and Associations of Nonglaucomatous Optic Nerve Atrophy in High Myopia: The Ural Eye and Medical Study. Ophthalmology 2023, 130, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Gusek, G.C.; Guggenmoos-Holzmann, I.; Naumann, G.O. Variability of the real dimensions of normal human optic discs. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988, 226, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E.; Chihara, K. Covariation of optic disc measurements and ocular parameters in the healthy eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994, 232, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.S.; Ritch, R.; Shin, D.H.; Wan, J.Y.; Chi, T. Age-related decline of disc rim area in visually normal subjects. Ophthalmology 1992, 99, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprioli, J.; Miller, J.M. Optic disc rim area is related to disc size in normal subjects. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987, 105, 1683–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Q.S.; Xu, L.; Jonas, J.B. Tilted optic discs: The Beijing Eye Study. Eye (Lond) 2008, 22, 728–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How, A.C.; Tan, G.S.; Chan, Y.H.; Wong, T.T.; Seah, S.K.; Foster, P.J.; Aung, T. Population prevalence of tilted and torted optic discs among an adult Chinese population in Singapore: the Tanjong Pagar Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Yoo, C.; Kim, Y.Y. Myopic optic disc tilt and the characteristics of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma 2012, 21, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y.; Park, H.Y.; Park, C.K. The effect of myopic optic disc tilt on measurement of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography parameters. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kook, M.S. Patterns of Damage in Young Myopic Glaucomatous-appearing Patients With Different Optic Disc Tilt Direction. J Glaucoma 2017, 26, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Han, J.C.; Kee, C. The Effects of Optic Nerve Head Tilt on Visual Field Defects in Myopic Normal Tension Glaucoma: The Intereye Comparison Study. J Glaucoma 2019, 28, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Sung, K.R.; Park, J.; Yoon, J.Y.; Shin, J.W. Sub-classification of myopic glaucomatous eyes according to optic disc and peripapillary features. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.W.; Chang, S.Y.; Sun, F.J.; Hsieh, J.W. Different Disc Characteristics Associated With High Myopia and the Location of Glaucomatous Damage in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and Normal-Tension Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2019, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, I.; Altan, C.; Yalcinkaya, G.; Tellioglu, A.; Yilmaz, E.; Alagoz, N.; Taskapili, M. Optic disc tilt and rotation effects on positions of superotemporal and inferotemporal retinal nerve fibre layer peaks in myopic Caucasians. Clin Exp Optom. 2023, 106, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kee, C. Visual Field Progression Pattern Associated With Optic Disc Tilt Morphology in Myopic Open-Angle Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016, 169, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.B.; Kee, C. The Characteristics of Deep Optic Nerve Head Morphology in Myopic Normal Tension Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017, 58, 2695–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hong, E.; Lee, E.J. Optic Disc Morphology and Paracentral Scotoma in Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma and Myopia. J Clin Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.S.; Heo, H.; Ji, Y.S.; Park, S.W. Predicting the risk of parafoveal scotoma in myopic normal tension glaucoma: role of optic disc tilt and rotation. Eye (Lond) 2017, 31, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Sung, K.R.; Park, J.M.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kang, S.Y.; Park, S.B.; Koo, H.J. Optic disc and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer characteristics associated with glaucomatous optic disc in young myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017, 255, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, Y.; Hangai, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Yoshitomi, T. Association of Myopic Deformation of Optic Disc with Visual Field Progression in Paired Eyes with Open-Angle Glaucoma. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cao, K.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fan, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, N. Intereye Comparison of Focal Lamina Cribrosa Defect in Normal-Tension Glaucoma Patients with Asymmetric Visual Field Loss. Ophthalmic Res. 2021, 64, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Sung, K.R.; Park, J.M. Myopic glaucomatous eyes with or without optic disc shape alteration: a longitudinal study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, B.R.; Park, K.H.; Jeoung, J.W. Optic Disc Tilt and Glaucoma Progression in Myopic Glaucoma: A Longitudinal Match-Pair Case-Control Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019, 60, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, T.W. Lamina cribrosa configuration in tilted optic discs with different tilt axes: a new hypothesis regarding optic disc tilt and torsion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 2958–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, E.; Seah, S.K.; Chan, S.P.; Lim, A.T.; Chew, S.J.; Foster, P.J.; Aung, T. Optic disk ovality as an index of tilt and its relationship to myopia and perimetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005, 139, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.S.; Li, J.; Wang, J.D.; Xiong, Y.; Cao, K.; Hou, S.M.; Yusufu, M.; Wang, K.J.; Li, M.; Mao, Y.Y.; et al. The association of myopia progression with the morphological changes of optic disc and β-peripapillary atrophy in primary school students. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Kam, K.W.; Young, A.L.; Ip, P.; Zhang, W.; Tham, C.C.; Chen, L.J.; et al. Association of Optic Nerve Head Metrics and Parapapillary Gamma Zone With Myopia Onset and Progression in Children: The Hong Kong Children Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025, 66, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara E., T.S. Positive correlation between rotation of the optic disc and location of glaucomatous scotomata; Kugler Publications Amsterdam/New York, 1992; pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.Y.; Lee, K.; Park, C.K. Optic disc torsion direction predicts the location of glaucomatous damage in normal-tension glaucoma patients with myopia. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.R.; Kook, M.S. Optic disc torsion presenting as unilateral glaucomatous-appearing visual field defect in young myopic Korean eyes. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Lee, K.I.; Lee, K.; Shin, H.Y.; Park, C.K. Torsion of the optic nerve head is a prominent feature of normal-tension glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014, 56, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Kook, M.S. Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Damage in Young Myopic Eyes With Optic Disc Torsion and Glaucomatous Hemifield Defect. J Glaucoma 2017, 26, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Choi, S.I.; Choi, J.A.; Park, C.K. Disc Torsion and Vertical Disc Tilt Are Related to Subfoveal Scleral Thickness in Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients With Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 4927–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.S.; Kang, Y.S.; Heo, H.; Park, S.W. Optic Disc Rotation as a Clue for Predicting Visual Field Progression in Myopic Normal-Tension Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, P.N.; Hung, C.H.; Chen, Y.C. Implications of optic disc rotation in the visual field progression of myopic open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.H.; Ross, E.A. Axial myopia in eyes with optic nerve hypoplasia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992, 230, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohguro, H.; Ohguro, I.; Tsuruta, M.; Katai, M.; Tanaka, S. Clinical distinction between nasal optic disc hypoplasia (NOH) and glaucoma with NOH-like temporal visual field defects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010, 4, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Frantz, K.A.; Roberts, D.K. Association of refractive error with optic nerve hypoplasia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2015, 35, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple, D.J.; Rabb, M.F.; Walsh, P.M. Congenital anomalies of the optic disc. Surv Ophthalmol. 1982, 27, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K.; Moriyama, M.; Shimada, N.; Nagaoka, N.; Ishibashi, T.; Tokoro, T.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Analyses of shape of eyes and structure of optic nerves in eyes with tilted disc syndrome by swept-source optical coherence tomography and three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. Eye (Lond) 2013, 27, 1233–1241; quiz 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, H.; Duan, J.; Xi, R.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chai, S. Association between myopia and relative peripheral refraction in children with monocular Tilted disc syndrome. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, R.A.; Wang, Y.X.; Yang, H.; Li, J.J.; Xu, L.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Jonas, J.B. Optic Disc-Fovea Distance, Axial Length and Parapapillary Zones. The Beijing Eye Study 2011. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0138701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Panda-Jonas, S. Myopia: Histology, clinical features, and potential implications for the etiology of axial elongation. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023, 96, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.W.; Chong, C.; Sharma, S.; Phang, L.C.; Lor, S.; Hoang, Q.V.; Girard, M.; Cheng, C.Y.; Schmetterer, L.; Jonas, J.B.; et al. Independent Effects of Axial Length and Intraocular Pressure on the Highly Myopic Optic Nerve Head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025, 66, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno-Matsui, K.; Akiba, M.; Moriyama, M.; Shimada, N.; Ishibashi, T.; Tokoro, T.; Spaide, R.F. Acquired optic nerve and peripapillary pits in pathologic myopia. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Akagi, T.; Hangai, M.; Takayama, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Suda, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yamada, H.; Nakanishi, H.; Unoki, N.; et al. Lamina cribrosa defects and optic disc morphology in primary open angle glaucoma with high myopia. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, S.; Kim, Y.W.; Lim, H.B.; Park, K.H.; Jeoung, J.W. Effects of Beta-zone Peripapillary Atrophy and Focal Lamina Cribrosa Defects on Peripapillary Vessel Parameters in Young Myopic Eyes. J Glaucoma 2021, 30, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochida, S.; Yoshida, T.; Nomura, T.; Hatake, R.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Association between peripheral visual field defects and focal lamina cribrosa defects in highly myopic eyes. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Cho, S.H.; Sohn, D.Y.; Kee, C. The Characteristics of Lamina Cribrosa Defects in Myopic Eyes With and Without Open-Angle Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016, 57, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Araie, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Yoshitomi, T. Multiple Temporal Lamina Cribrosa Defects in Myopic Eyes with Glaucoma and Their Association with Visual Field Defects. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, A.; Ikuno, Y.; Asai, T.; Usui, S.; Nishida, K. Defects of the Lamina Cribrosa in High Myopia and Glaucoma. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0137909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Araie, M.; Kasuga, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Iwata, T.; Murata, K.; Yoshitomi, T. Focal Lamina Cribrosa Defect in Myopic Eyes With Nonprogressive Glaucomatous Visual Field Defect. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018, 190, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Berenshtein, E.; Holbach, L. Lamina cribrosa thickness and spatial relationships between intraocular space and cerebrospinal fluid space in highly myopic eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004, 45, 2660–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Dong, L.; Guo, Y.; Panda-Jonas, S. Advances in myopia research anatomical findings in highly myopic eyes. Eye Vis (Lond) 2020, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Kutscher, J.N.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Hayreh, S.S. Lamina cribrosa thickness correlated with posterior scleral thickness and axial length in monkeys. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 94, e693–e696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Dichtl, A. Optic disc morphology in myopic primary open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997, 235, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.C.; Hahn, I.K.; Sung, K.R.; Yoon, J.Y.; Jeong, D.; Chung, H.S. Lamina cribrosa depth according to the level of axial length in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 2247–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.Y.; Noh, H.; Kee, C.; Han, J.C. Topographic Relationships among Deep Optic Nerve Head Parameters in Patients with Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. J Clin Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Xue, C.C.; Jonas, J.B.; Wang, Y.X. Lamina Cribrosa Configurations in Highly Myopic and Non-Highly Myopic Eyes: The Beijing Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024, 65, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Hangai, M.; Murata, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Yoshitomi, T. Lamina Cribrosa Depth Variation Measured by Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Within and Between Four Glaucomatous Optic Disc Phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 5777–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Kambayashi, M.; Araie, M.; Murata, H.; Enomoto, N.; Kikawa, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Higashide, T.; Miki, A.; Iwase, A.; et al. Deep Optic Nerve Head Structures Associated With Increasing Axial Length in Healthy Myopic Eyes of Moderate Axial Length. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023, 249, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Panda-Jonas, S. Optic Nerve Head Histopathology in High Axial Myopia. J Glaucoma 2017, 26, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Chen, Q.; Xu, X.; Lv, H.; Du, Y.; Wang, L.; Yin, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zou, H.; He, J.; et al. Morphological Characteristics of the Optic Nerve Head and Choroidal Thickness in High Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020, 61, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Foo, L.L.; Hu, Z.; Pan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Saw, S.M.; Hoang, Q.V.; Lan, W. Bruch's Membrane Opening Changes in Eyes With Myopic Macular Degeneration: AIER-SERI Adult High Myopia Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024, 65, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Wang, L.; Hong, J.; Sun, X. Eight Years and Beyond Longitudinal Changes of Peripapillary Structures on OCT in Adult Myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024, 264, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Wei, W.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Jonas, J.B. Size and Shape of Bruch's Membrane Opening in Relationship to Axial Length, Gamma Zone, and Macular Bruch's Membrane Defects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019, 60, 2591–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezapour, J.; Bowd, C.; Dohleman, J.; Belghith, A.; Proudfoot, J.A.; Christopher, M.; Hyman, L.; Jonas, J.B.; Fazio, M.A.; Weinreb, R.N.; et al. The influence of axial myopia on optic disc characteristics of glaucoma eyes. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.M. How is eyeball growth associated with optic nerve head shape and glaucoma? The Lamina cribrosa/Bruch's membrane opening offset theory. Exp Eye Res. 2024, 245, 109975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toranzo, J.; Cohen, S.Y.; Erginay, A.; Gaudric, A. Peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation in myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005, 140, 731–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F.; Akiba, M.; Ohno-Matsui, K. Evaluation of peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation with swept source and enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Retina 2012, 32, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Luo, N.; Ye, L.; Cheng, L.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, H.; Huang, J. Peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation in myopic eyes with open-angle glaucoma: association with myopic fundus changes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Aoki, S.; Shirato, S.; Sakata, R.; Honjo, M.; Aihara, M.; Saito, H. Visual Field of Eyes with Peripapillary Intrachoroidal Cavitation and Its Association with Deep Optic Nerve Head Structural Changes. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2025, 8, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Jonas, J.B. Optic nerve head anatomy in myopia and glaucoma, including parapapillary zones alpha, beta, gamma and delta: Histology and clinical features. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021, 83, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Wei, W.B.; Xu, L.; Jonas, J.B. Parapapillary Beta Zone and Gamma Zone in a Healthy Population: The Beijing Eye Study 2011. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018, 59, 3320–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Jonas, J.B.; Huang, H.; Wang, M.; Sun, X. Microstructure of parapapillary atrophy: beta zone and gamma zone. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013, 54, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.S.; Heo, H.; Park, S.W. Microstructure of Parapapillary Atrophy Is Associated With Parapapillary Microvasculature in Myopic Eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018, 192, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.Y.; Shin, D.Y.; Jeon, S.J.; Park, C.K. Association Between Parapapillary Choroidal Vessel Density Measured With Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and Future Visual Field Progression in Patients With Glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; De Moraes, C.G.; Prata, T.S.; Tello, C.; Ritch, R.; Liebmann, J.M. Beta-Zone parapapillary atrophy and the velocity of glaucoma progression. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.H.; Zangwill, L.M.; Manalastas, P.I.C.; Belghith, A.; Yarmohammadi, A.; Akagi, T.; Diniz-Filho, A.; Saunders, L.; Weinreb, R.N. Deep-Layer Microvasculature Dropout by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and Microstructure of Parapapillary Atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018, 59, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, Y.Y.; Xu, L.; Wei, W.B.; Jonas, R.A. Parapapillary Gamma Zone and Axial Elongation-Associated Optic Disc Rotation: The Beijing Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016, 57, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E.; Honda, Y. Preservation of nerve fiber layer by retinal vessels in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1992, 99, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Choung, H.K.; Kim, M.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.H. Positional Change of Optic Nerve Head Vasculature during Axial Elongation as Evidence of Lamina Cribrosa Shifting: Boramae Myopia Cohort Study Report 2. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Fernández, M.C. Shape of the neuroretinal rim and position of the central retinal vessels in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994, 78, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E.; Chihara, K. Apparent cleavage of the retinal nerve fiber layer in asymptomatic eyes with high myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992, 230, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, E. Myopic Cleavage of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Assessed by Split-Spectrum Amplitude-Decorrelation Angiography Optical Coherence Tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, e152143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Wy, S.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, E.J. Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Defect Associated With Progressive Myopia. J Glaucoma 2023, 32, e103–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Kim, Y.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Sohn, Y.H. Characteristics of eyes with inner retinal cleavage. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraoka, Y.; Tsujikawa, A.; Hata, M.; Yamashiro, K.; Ellabban, A.A.; Takahashi, A.; Nakanishi, H.; Ooto, S.; Tanabe, T.; Yoshimura, N. Paravascular inner retinal defect associated with high myopia or epiretinal membrane. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, I.J.; Park, K.A.; Oh, S.Y. Association between myopia and peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures in children. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon-Chapman, J.; Estrela, T.; Heidary, G.; Gise, R. Prevalence, time course, and visual impact of peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures (PHOMS) in pediatric patients with optic nerve pathologies. J aapos 2024, 28, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M.; Seray, S.; Amoroso, F.; Madar, C.; Souied, E.H. Peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures and the retinal nerve fiber layer thinning. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2024, 34, Np126–np130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalej, R.; Bouassida, M.; Picard, H.; Clermont, C.V.; Hage, R. Are Peripapillary Hyperreflective Ovoid Mass-like Structures with an Elevated Optic Disc Still a Diagnosis Dilemma? Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Hu, R.; Liu, Q.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Yi, Z.; Yuan, J.; Shao, Y.; Shen, M.; Zheng, H.; et al. Enlarged Blind Spot Linked to Gamma Zone and Peripapillary Hyperreflective Ovoid Mass-Like Structures in Non-Pathological Highly Myopic Eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025, 66, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, L.; Rehan, S.; West, J.; Watts, P. Is the presence of peripapillary hyperreflective ovoid mass-like structures (PHOMS) in children related to the optic disc area, scleral canal diameter and refractive status? Eye (Lond) 2025, 39, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, J.; Mozaffarieh, M. What is the present pathogenetic concept of glaucomatous optic neuropathy? Surv Ophthalmol. 2007, 52 Suppl 2, S162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Aizawa, N.; Chiba, N.; Omodaka, K.; Nakamura, M.; Otomo, T.; Yokokura, S.; Fuse, N.; Nakazawa, T. Significant correlations between optic nerve head microcirculation and visual field defects and nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma patients with myopic glaucomatous disk. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, T.; Iida, Y.; Nakanishi, H.; Terada, N.; Morooka, S.; Yamada, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Yokota, S.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshimura, N. Microvascular Density in Glaucomatous Eyes With Hemifield Visual Field Defects: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016, 168, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, E.; Dimitrova, G.; Amano, H.; Chihara, T. Discriminatory Power of Superficial Vessel Density and Prelaminar Vascular Flow Index in Eyes With Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension and Normal Eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017, 58, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.W.; Kwon, J.; Lee, J.; Kook, M.S. Relationship between vessel density and visual field sensitivity in glaucomatous eyes with high myopia. Br J Ophthalmol 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, T.W. Evaluation of Parapapillary Choroidal Microvasculature Dropout and Progressive Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thinning in Patients With Glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, R.; Ochiai, S.; Akagi, T.; Miyamoto, D.; Sakaue, Y.; Iikawa, R.; Fukuchi, T. Parapapillary choroidal microvasculature dropout in eyes with primary open-angle glaucoma. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 20601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Song, J.E.; Hwang, H.S.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.W. Choroidal Microvasculature Dropout in the Absence of Parapapillary Atrophy in POAG. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023, 64, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.S.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.W. Influence of choroidal microvasculature dropout on progressive retinal nerve fibre layer thinning in primary open-angle glaucoma: comparison of parapapillary β-zones and γ-zones. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, K.; Nishida, T.; Moghimi, S.; Micheletti, E.; Du, K.; Weinreb, R.N. Relationship of Choroidal Microvasculature Dropout and Beta Zone Parapapillary Area With Visual Field Changes in Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024, 257, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuba-Sulluchuco, F.; Mendez-Hernandez, C. Relationship Between Parapapillary Microvasculature Dropout and Visual Field Defect in Glaucoma: A Cross-Sectional OCTA Analysis. J Clin Med. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwan, Y.; Chansangpetch, S.; Fard, M.A.; Pooprasert, P.; Chalardsakul, K.; Threetong, T.; Tipparut, S.; Saaensupho, T.; Tantraworasin, A.; Hojati, S.; et al. Association of myopia and parapapillary choroidal microvascular density in primary open-angle glaucoma. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0317881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.M.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.W. Evaluation of Peripapillary Choroidal Microvasculature to Detect Glaucomatous Damage in Eyes With High Myopia. J Glaucoma 2020, 29, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.L.; Jeon, S.J.; Park, C.K. Features of the Choroidal Microvasculature in Peripapillary Atrophy Are Associated With Visual Field Damage in Myopic Patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018, 192, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, K.; Cheng, D.; Wang, Y.; Ni, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, S.; Lin, S.; Tao, A.; Shao, Y.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of optic disc microvasculature dropout for detecting glaucoma in eyes with high myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2025, 109, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Xie, J.; Shi, Y.; Li, M.; Ye, L.; Chen, Q.; Lv, H.; Yin, Y.; Zou, H.; He, J.; et al. Morphological characteristics of the optic nerve head and impacts on longitudinal change in macular choroidal thickness during myopia progression. Acta Ophthalmologica 2022, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Qiu, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chen, M.; Song, Y.; Xiong, J.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Macular and submacular choroidal microvasculature in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and high myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023, 107, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Choi, J.; Shin, J.W.; Lee, J.; Kook, M.S. Alterations of the Foveal Avascular Zone Measured by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Glaucoma Patients With Central Visual Field Defects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017, 58, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Kanno, J.; Weinreb, R.N.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Mine, I.; Ishii, H.; Ibuki, H.; Shinoda, K. OCT angiography measured changes in the foveal avascular zone area after glaucoma surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araie, M.; Arai, M.; Koseki, N.; Suzuki, Y. Influence of myopic refraction on visual field defects in normal tension and primary open angle glaucoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakata, R.; Aihara, M.; Murata, H.; Mayama, C.; Tomidokoro, A.; Iwase, A.; Araie, M. Contributing factors for progression of visual field loss in normal-tension glaucoma patients with medical treatment. J Glaucoma 2013, 22, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Li, L.; Zhong, H.; Wei, T.; Yuan, Y.S.; Li, Y. Changes to central visual fields in cases of severe myopia in a Chinese population. Ann Palliat Med. 2020, 9, 2616–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.J.; Park, H.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, E.K.; Park, C.K. Association of Scleral Deformation Around the Optic Nerve Head With Central Visual Function in Normal-Tension Glaucoma and Myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020, 217, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.G.; Shin, Y.I.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Jeoung, J.W.; Park, K.H. Papillomacular bundle defect (PMBD) in glaucoma patients with high myopia: frequency and risk factors. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 21958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, S.; Ikuno, Y.; Asai, T.; Kikawa, T.; Akiba, M.; Miki, A.; Matsushita, K.; Kawasaki, R.; Nishida, K. Effect of peripapillary tilt direction and magnitude on central visual field defects in primary open-angle glaucoma with high myopia. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2020, 64, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ye, L.; Luo, N.; Cheng, L.; Xiang, Y.; Han, Y.; Huang, J. Relationships of Paracentral Scotoma With Structural and Vascular Parameters in Highly Myopic Eyes With Early Open-angle Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, K.; Miyake, M.; Akagi, T.; Ikeda, H.O.; Kameda, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Numa, S.; Tsujikawa, A. Exploration of the cutoff values of axial length that is susceptible to develop advanced primary open angle glaucoma in patients aged less than 50 years. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, J.; Lee, J. Optic Nerve Head Curvature Flattening Is Associated with Central Visual Field Scotoma. J Clin Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.E.; Kim, S.A.; Shin, D.Y.; Park, C.K.; Park, H.L. Ocular and Hemodynamic Factors Contributing to the Central Visual Function in Glaucoma Patients With Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022, 63, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Park, C.K.; Park, H.L. Factors Affecting Visual Acuity and Central Visual Function in Glaucoma Patients With Myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023, 253, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, E.; El-Nimri, N.; Nishida, T.; Moghimi, S.; Rezapour, J.; Fazio, M.A.; Suh, M.H.; Bowd, C.; Belghith, A.; Christopher, M.; et al. Central visual field damage in glaucoma eyes with choroidal microvasculature dropout with and without high axial myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MON | GON | |

| Dependence on IOP | Less dependent on IOP [18] | Apparent IOP dependent |

| Speed of progression | Slow [18] | Fast |

| VF Progression associated with age | Progress mainly before age 50 and tends not to progress after 50 [45,46,47]. | Older age is a risk factor for progression [48,49,51] |

| Association with myopia | High [109] | Moderate |

| Pattern of visual field defects | Atypical patterns, enlarged blind spot, central visual field defects [7] | Bjerrum scotoma, nasal step, paracentral scotoma, and diffuse loss |

| Papillo-macular bundle length | Long [15] | Variable |

| Deformation of disc | γ-zone commonly present [7,109] | Variable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).