1. Introduction

Dry vegetable powders obtained from secondary raw materials (pomace of carrot, beetroot, pumpkin, and similar wastes) serve as natural additives for enriching food products with bioactive compounds such as antioxidants, vitamins, dietary fibers, and pigments. They effectively replace synthetic colorants, preservatives, and stabilizers, contributing to the creation of healthier and more environmentally friendly products [

1]. The global market for natural colorants and functional ingredients is growing at 8–10% annually [

2]. Powders from vegetable pomace are already successfully used in the EU and USA as substitutes for synthetic colorants (E124, E129, E160b) and antioxidants (E300–E321) [

3,

4]. This aligns with the principles of sustainable development by reducing food waste and enhancing the functionality of finished products.

Studies show that adding vegetable powders at dosages of 0.5–1% to yogurts increases total phenolic content (TPC) by up to 300% and extends shelf life due to antioxidant properties [

5]. In ice cream (0.2–0.5%), powders stabilize texture by preventing ice crystal formation [

6]. In juices (0.2–0.5%), they act as natural colorants, enriching the product with pigments such as betalains [

7]. In cocktails (0.3–0.6%), they stabilize emulsions and prevent phase separation [

8]. In teas (1–2%), they serve as flavor enhancers, intensifying taste [

9]. In bread (1–3%), powders slow down staling thanks to dietary fibers, prolonging freshness [

10]. For gluten-free bakery products (2–4%), they provide additional fiber to improve structure [

11]. In sausages (0.1–0.3%), powders inhibit lipid oxidation, extending shelf life [

12]. For vegan meat analogs (0.5–1%), they ensure natural color [

13]. In canned fish (0.1–0.3%), they prevent rancidity [

14]. Research results demonstrate that incorporating vegetable powders into food formulations extends shelf life, provides stable color, enhances flavor, stabilizes emulsions (preventing separation), and improves bioavailability. However, authors also note that higher dosages can impart bitterness to products [

15] or undesirable off-flavors [

16], affect texture by making it less uniform [

17], and increase viscosity [

18].

Studies confirm that the physicochemical properties of vegetable powders significantly influence the sensory, stabilizing, rheological, structural, organoleptic, and other characteristics of the final food product [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The most common methods for producing vegetable powders are vacuum-microwave drying and convective hot-air drying. However, each drying method, depending on the type of plant raw material and the intended use of the resulting powder, has its own advantages and disadvantages [

24]. Convective hot-air drying is one of the most widespread and cost-effective methods for producing powders from vegetable pomace. It yields powders with good dietary fiber content but often results in 20–50% losses of thermolabile antioxidants (carotenoids, betalains) due to high temperatures [

25]. Vacuum-microwave drying enables drying at low temperatures (40–60 °C), preserving antioxidants much better (retention up to 80–90%), as well as color and flavor. This method reduces drying time by 5–10 times and minimizes oxidation [

26,

27]. In recent years, ultrasound-assisted processing (ultrasound-assisted extraction, UAE) has been widely applied for extracting antioxidants from carrot, beetroot, and pumpkin pomace. It significantly increases the yield of bioactive compounds compared to traditional methods, thanks to cavitation that disrupts cell walls and enhances mass transfer. UAE minimizes oxidation at moderate power levels, improving stability in moist products (e.g., emulsions or yogurts) [

28]. Its selectivity helps reduce bitterness by limiting the extraction of bitter phenolic compounds [

29]. UAE of carotenoids (β-carotene, lutein, lycopene) from carrot pomace provides higher yields than conventional methods [

30]. However, excessive power, duration, or temperature (>60 °C) can generate free radicals (OH, H₂O₂), leading to oxidation, isomerization, or degradation of bioactives (e.g., carotenoids in carrot at >60% ethanol, betalains in beetroot at room temperature) [

31].

The aim of the present study was to determine the advantages and disadvantages of various drying methods, including combined ones, using pomace from carrot, beetroot, and pumpkin as examples. The research objective was to conduct a comparative analysis of the production of dry functional vegetable powders from carrot, beetroot, and pumpkin pomace using convective drying, ultrasound-assisted (combined) processing, and vacuum-microwave drying. The novelty of the study lies in establishing the relationships between drying parameters and methods applied to carrot, beetroot, and pumpkin pomace and the qualitative, rheological, organoleptic, and other characteristics of the resulting vegetable powders.

4. Discussion

The nutritional value and functional properties of vegetable powders obtained from pomace depend on the drying methods and process parameters, as well as on the type and characteristics of the raw material [

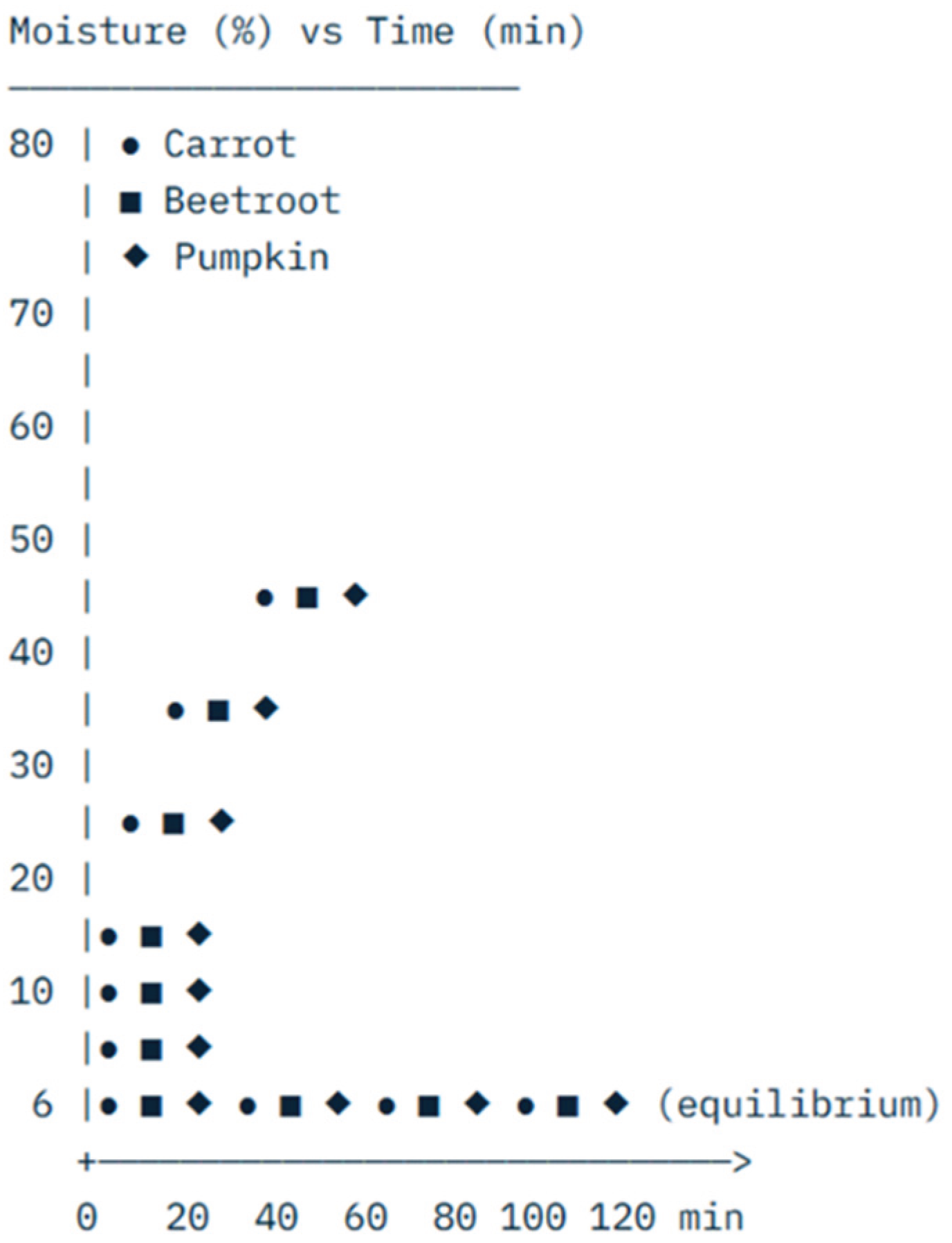

43]. For example, the vacuum-microwave drying (VMD) process proceeds faster for beetroot (reaching ~5% moisture by 90–100 minutes) due to lower bound moisture content, while it is slower for pumpkin due to its high starch content and initial moisture level.

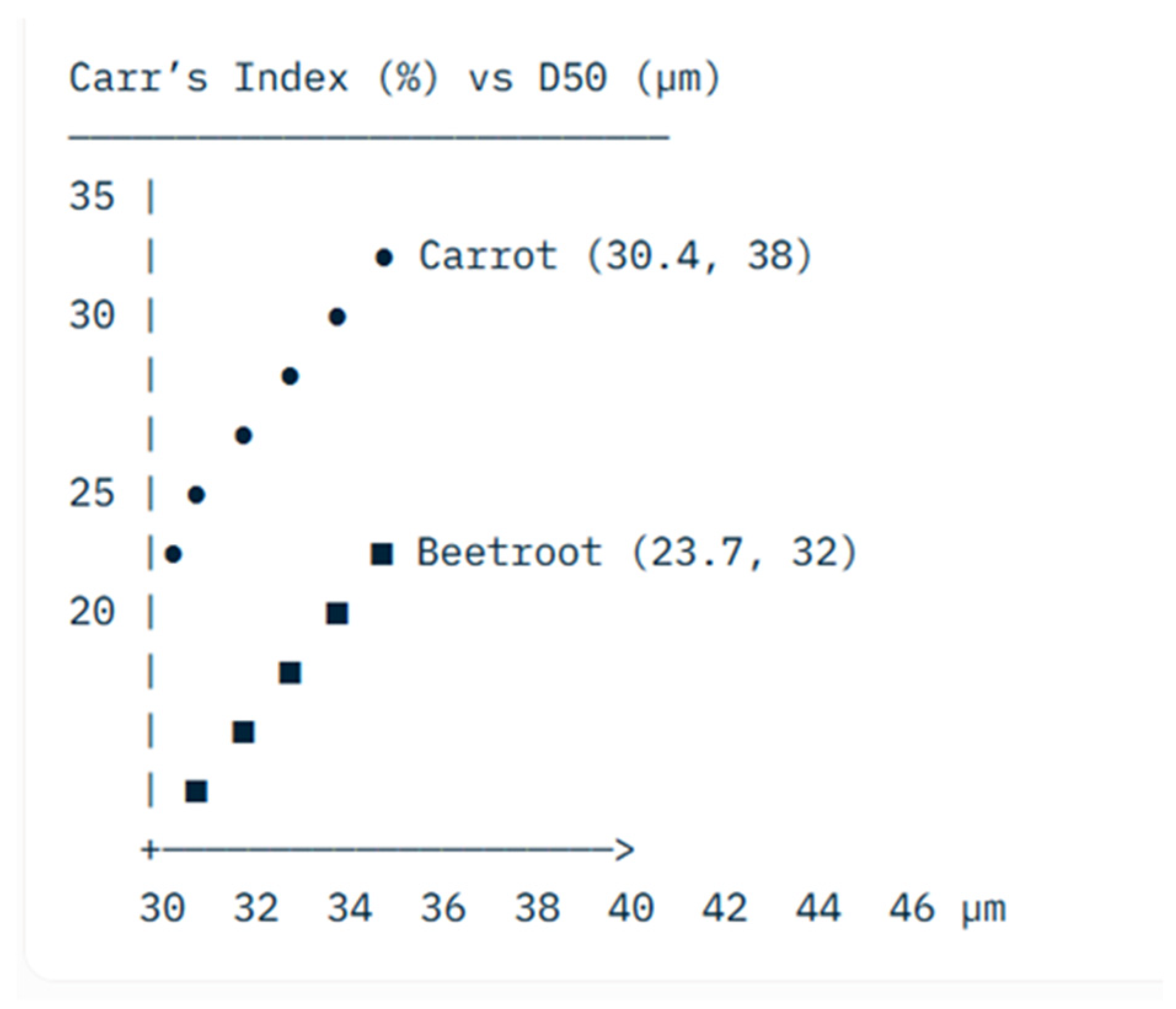

The granulometric composition and density characteristics of the vegetable powders indicate that particle properties significantly influence flowability, dispersibility, solubility, color, and sensory attributes [

42]. For instance, the high sphericity of beetroot particles ensures superior flowability (D50 < 35 µm + Span < 1.8), while the high porosity (>40%) of carrot particles provides excellent dispersibility and solubility. The type of pigment also contributes to color retention in beetroot powder [

44].

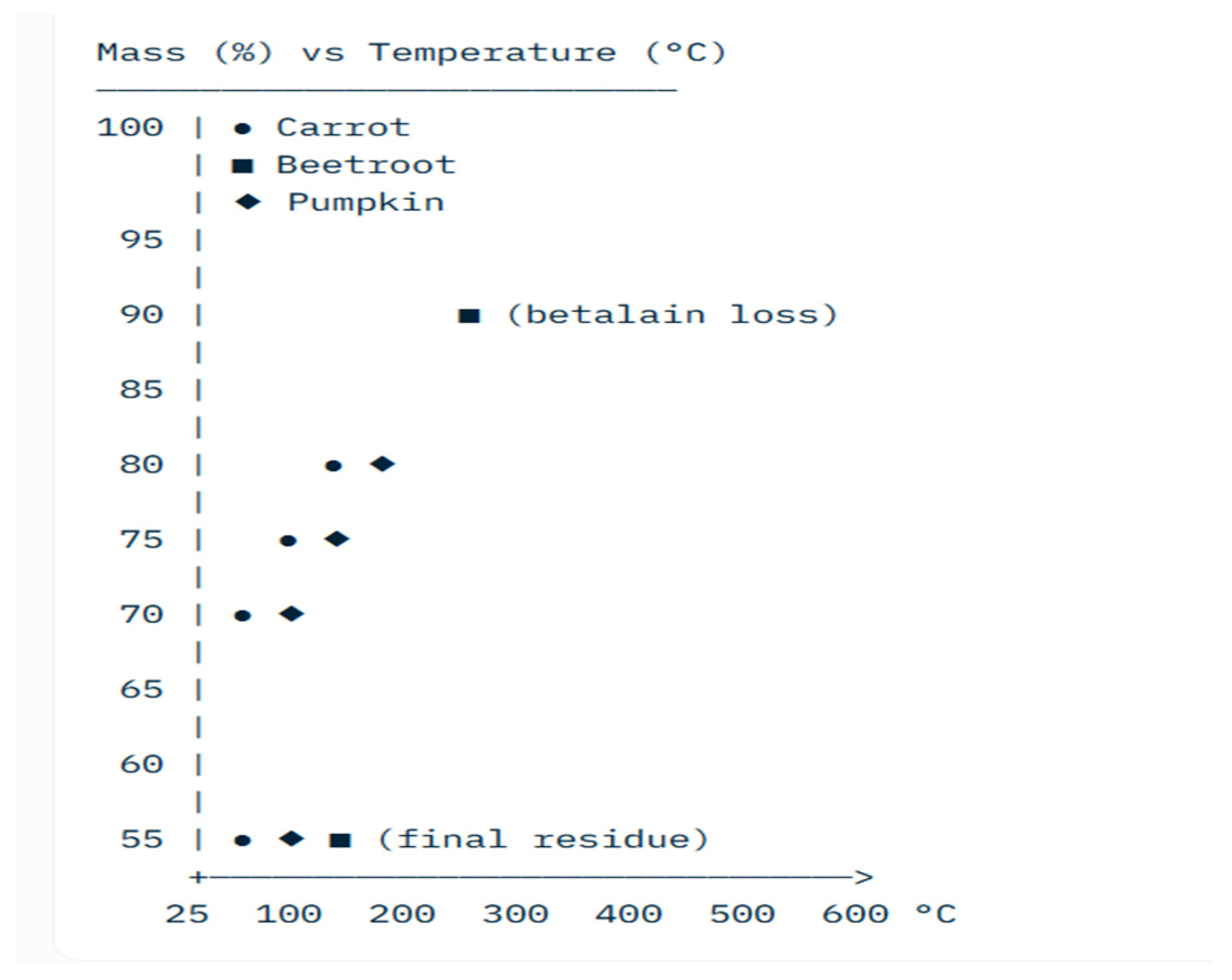

Thermal analysis of the vegetable powders demonstrated good thermostability up to approximately 200–250 °C, with mass loss not exceeding 10–12%. The main decomposition stage occurred above 300 °C, which is typical for fiber-rich plant materials. Therefore, these powders can be safely used in food technologies without significant degradation at temperatures up to 200 °C [

45].

The combination of ultrasound pretreatment with vacuum-microwave drying enabled rapid moisture reduction in the first 20–30 minutes and safe moisture levels (<8–10%) were achieved within 60–90 minutes. Equilibrium moisture content was reached in approximately 2 hours, while thermal stress on thermolabile compounds was minimized due to the reduced boiling point of water under vacuum [

46]. Analysis of the obtained results allowed optimization of vacuum-microwave drying parameters (

Table 7).

Recommended optimization parameters: Carrot: medium power (400 W) for maximum β-carotene retention (85%) with reasonable drying time (20–25 min); Beetroot: low vacuum (5–10 kPa) and power of 300 W to minimize betalain oxidation, achieving up to 90% retention; Pumpkin: low power (200 W) is optimal for preserving vitamins (95%) and reducing drying time to 10–15 min [

47].

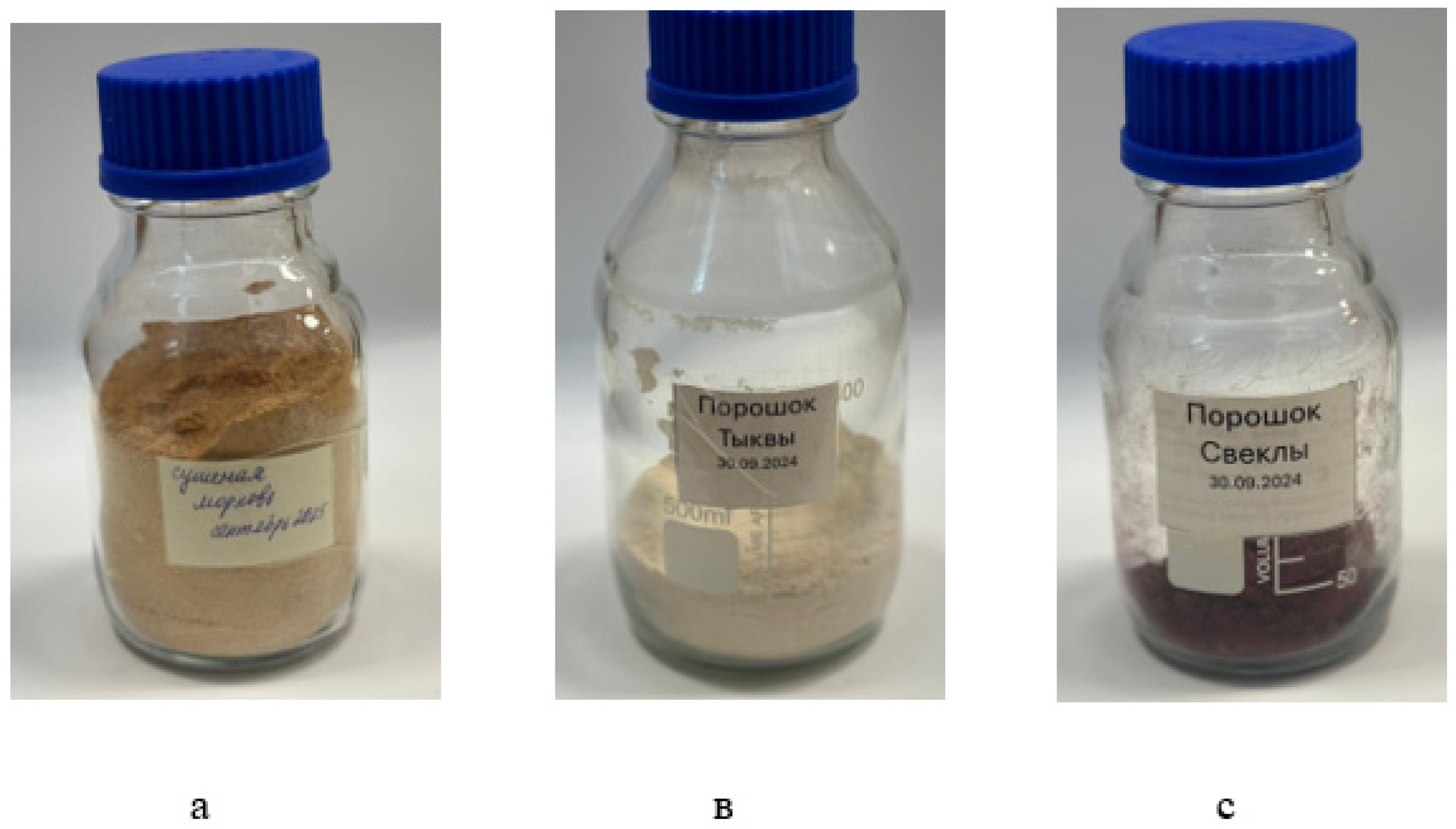

Figure 4 presents the powders obtained by the vacuum-microwave drying method.

Convective drying without preliminary ultrasound pretreatment produces powders with poorer technological properties (lower flowability, reduced solubility, coarser texture) and significantly lower content of bioactive compounds (especially carotenoids and betalains). Ultrasound pretreatment noticeably improves the quality of the final product when followed by convective drying [

42].