Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation for SLMs

1.2. The Paradigm Shift: From Scaling-Up to Scaling-Down

1.3. Defining the Spectrum: SLMs vs. LLMs

1.4. Contributions of this Survey

2. The SLM Landscape: A Modern Taxonomy

2.1. Axis 1: Categorization by Model Size

- Ultra-small (<100M parameters): Models like TinyBERT variants, suitable for highly constrained microcontroller environments.

- Small (100M–1B): Models like Llama 3.2 1B, balancing efficiency and baseline performance.

- Medium (1B–10B): The most common category for edge deployment, including Phi-4-mini (3.8B), Mistral 7B, and Gemma 2 9B.

- Large (10B–15B): Models like Phi-4 (14B) that overlap with LLMs but are optimized for efficiency.

2.2. Axis 2: Classification by Genesis

2.2.1. Knowledge Distillation

2.2.2. Trained-from-Scratch

2.3. Axis 3: Classification by Architecture

2.3.1. Dense Architectures

2.3.2. Sparse and Modular (MoE)

2.3.3. State Space and RNN-Inspired

2.4. Axis 4: Classification by Optimization Goal

2.4.1. Latency-Optimized

2.4.2. Memory-Optimized

2.4.3. Task-Specialized

2.5. Taxonomy Summary and Key Observations

3. Foundations of Small Language Models

3.1. Historical Evolution and Design Trade-Offs

3.2. The "Smart Data" Paradigm

-

“Textbooks Are All You Need”: The Phi Philosophy The Phi model series from Microsoft is a canonical example of the Smart Data paradigm in action. Their first paper, “Textbooks Are All You Need” [5], showed that a 1.3B parameter model (Phi-1) trained on a high-quality synthetic dataset of just 7 billion tokens could outperform models 10x its size on coding benchmarks. The follow-up, Phi-1.5, extended this to common sense reasoning [6], and Phi-2 and Phi-3 [26] further scaled this approach, achieving performance rivaling models like Mixtral 8x7B and GPT-3.5 with only 3.8B parameters. The core philosophy is that the quality and reasoning density of the training data are more important than its sheer volume or the model’s parameter count.Data Quality vs. Quantity: Revisiting Scaling Laws The success of SLMs trained on high-quality data forces a re-evaluation of the Chinchilla scaling laws. Although the original laws focused on the quantity of tokens, recent work suggests a more nuanced view where a “quality coefficient” should be considered [27]. A high-quality synthetic token might be worth 10, 100, or even 1,000 low-quality web tokens in terms of the learning it imparts. This implies that the path to better models may not be ever-larger datasets of raw text, but more sophisticated methods for generating and curating high-quality, targeted data. This fundamentally changes the economics of AI development, shifting value from raw data access to sophisticated data refinement techniques.

3.3. Dense Architectures

3.4. Sparse and Modular Architectures (MoE)

3.5. State Space and RNN-Inspired Models

-

Mamba Introduced as a state space model (SSM) in “Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces”, Mamba leverages selective state spaces to model sequences efficiently, offering linear time complexity compared to the quadratic complexity of transformers. It integrates SSM with MLP blocks, simplifying the architecture and enhancing hardware efficiency, achieving 5x faster inference than transformers. Mamba-3B outperforms transformers of similar size on the Pile benchmark, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in language, audio, and genomics, making it a viable alternative for SLMs in resource-constrained environments. Its ability to handle million-length sequences with linear scaling is particularly beneficial for tasks requiring long contexts, aligning with SLM deployment needs.RWKV The Receptance Weighted Key Value architecture, detailed in “RWKV: Reinventing RNNs for the Transformer Era”, combines RNNs and transformers, providing constant memory usage and inference speed, supporting infinite context length, and being 100% attention-free. RWKV models, such as RWKV-7 (Goose), are trained on multilingual data, offering better performance on tasks requiring long contexts, with versions up to 14 billion parameters showing scalability. Its sensitivity to prompt formatting necessitates careful design for SLM applications, but its efficiency makes it suitable for edge deployment, enhancing privacy, and reducing latency.

3.6. Compact Transformer Variants

-

MobileBERT MobileBERT is a thin version of BERT_LARGE with bottleneck structures, achieving 99.2% of BERT-base’s performance on GLUE with 4x fewer parameters (25M vs. 110M) and 5.5x faster inference on a Pixel 4 phone, with a latency of 62 ms. Its design balances self-attention and feedforward networks, making it ideal for resource-limited devices, aligning with SLM deployment goals.FNet Detailed in “FNet: Mixing Tokens with Fourier Transforms”, FNet replaces self-attention with unparameterized Fourier Transforms, achieving 92-97% of BERT’s accuracy on GLUE while training 80% faster on GPUs and 70% faster on TPUs at standard 512 input lengths. At longer sequences, it matches the accuracy of efficient transformers while outpacing them in speed, with a light-memory footprint, particularly efficient at smaller model sizes, outperforming transformer counterparts for fixed speed and accuracy budgets.TinyBERT Introduced in “TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for Natural Language Understanding”, TinyBERT is 7.5 times smaller and 9.4 times faster than the BERT base, maintaining 96. 8% performance through a two-stage distillation process in both the pretraining and task-specific learning stages. With 4 layers, it achieves competitive results on tasks like GLUE and SQuAD, suitable for applications requiring high accuracy with low resource usage, enhancing SLM deployability.

3.7. Attention Mechanisms

-

Multi-Head Attention (MHA) The self-attention mechanism is the heart of the transformer, but the original Multi-Head Attention (MHA) design, while powerful, is notoriously memory-intensive. During autoregressive generation (predicting one token at a time), the model must store the Key (K) and Value (V) vectors for all previously generated tokens in a Key-Value (KV) cache. As the sequence length grows, this cache can become a significant memory bottleneck.Multi-Query Attention (MQA) Proposed by Shazeer in 2019, MQA was a radical optimization that addressed the KV cache problem directly. Instead of each attention head having its own unique K and V projections, MQA uses a single, shared set of K and V projections across all query heads. This dramatically reduces the size of the KV cache by a factor equal to the number of heads, leading to substantial memory savings and faster inference, especially for long sequences.Grouped-Query Attention (GQA) GQA emerged as the pragmatic and now dominant compromise between MHA’s performance and MQA’s efficiency. Instead of having one K/V pair for all heads (MQA) or one for each head (MHA), GQA divides the query heads into several groups and assigns a shared K/V pair to each group. This approach interpolates between the two extremes, achieving performance nearly on par with MHA while retaining most of the speed and memory benefits of MQA.

3.8. Position Encoding Innovations (RoPE)

3.9. Normalization Techniques

4. Data Strategies and Training Paradigms

4.1. From Big Data to High-Quality Data

4.2. Synthetic Data Generation

- Synthetic Textbooks: As pioneered by Microsoft’s Phi models, this involves prompting a teacher model to generate “textbook-like” content that explains concepts clearly and logically. These data are dense with information and free of the noise found in the web data [6].

- Chain-of-Thought Data: To improve reasoning, SLMs are trained on examples in which a teacher model has externalized its step-by-step thinking process, known as a chain of thought [31].

- Code Generation: For coding tasks, synthetic data includes not just code snippets, but also explanations of code, tutorials and question-answer pairs about programming concepts [32].

- Mathematical Reasoning: Synthetic data for math involves generating problems and their detailed, step-by-step solutions, teaching the model the process of solving the problem, not just the final answer [33].

4.3. Data Curation Pipelines

- 1.

- Source Selection: Instead of indiscriminately scraping the web, SLM training starts with selecting high quality sources, such as filtered web pages (e.g. Common Crawl filtered by quality classifiers), academic papers (e.g. arXiv), books (e.g. Google Books), and code (e.g., GitHub) [34].

- 2.

- Heuristic Filtering: A series of rules are applied to clean the data, such as removing documents with little text, boilerplate content (e.g., sign in, terms of use), or skewed character distributions [35].

- 3.

- Quality Classification: More advanced pipelines train a dedicated classifier model to predict the quality of a document. For example, one might train a classifier to distinguish between a Wikipedia article and a low-quality forum post, and then use this classifier to filter the entire web corpus [4].

- 4.

- Deduplication: Removing duplicate or near-duplicate examples from the training data is critical. It prevents the model from wasting capacity on redundant information and has been shown to significantly improve performance [36]. This is done at multiple granularities, from document-level to sentence-level.

4.4. Filtering, Mixing, and Curriculum Learning

- AlpaGasus filtered Alpaca’s 52k instruction dataset using ChatGPT to retain a high-quality subset of 9k examples, improving instruction-following quality and reducing training cost [38].

- Orca adopted a multiphase curriculum involving ChatGPT-generated instructions, GPT-4 answers, and explanation-tuned examples to progressively build reasoning skills [39].

- C-RLFT employed reward-weighted loss scaling based on helpfulness scores, with source-specific tokens for domain conditioning [40].

- CoLoR-Filter used a 150M-parameter proxy model to score and retain the most useful 4

- Collider introduced dynamic token-level filtering during training by pruning tokens with low estimated utility, achieving a 22% speedup with negligible loss [41].

- AlpaGasus achieved performance parity with Alpaca while using only 17% of the original dataset.

- CoLoR-Filter retained greater than 95% of task performance while using only 4% of the training data.

- Collider reduced training compute by 22% through token sparsification.

- Li et al. [42] show that balancing diversity and quality outperforms quality-only filtering in instruction tuning.

- 1.

- Dynamic filtering and curriculum-aware mixing, where data selection evolves based on model loss, entropy, or confidence.

- 2.

- Hybrid filtering pipelines that combine low-cost proxy models with LLM-based ranking for scalable precision.

- 3.

- Explainable filtering and diagnostics to ensure transparency in data selection, especially in safety-critical or instruction-tuned models.

- 4.

- Cross-lingual filtering frameworks that support multilingual training without requiring language-specific tuning.

4.5. Continual Pretraining and Domain Adaptation

-

Continual Pretraining (CPT) Continual pretraining (CPT) refers to the practice of extending training on an existing base model using additional domain-specific or task-relevant data without resetting model weights. For SLMs, CPT helps leverage the benefits of foundation models while aligning them to resource-constrained settings or niche domains. Techniques such as learning rate warm restarts, regularization to avoid catastrophic forgetting, and domain-aware sampling are key to maintaining stability. CPT is especially useful in low-compute settings where full pretraining from scratch is infeasible, and it allows SLMs to remain updated with new data trends.Masking Techniques Advanced masking strategies significantly affect the learning dynamics of SLMs, especially under causal or autoregressive objectives. Beyond basic left-to-right masking, approaches such as span masking (used in T5), dynamic masking, and task-specific masks (e.g., in retrieval-augmented training) can guide the model toward improved generalization. Some lightweight models also explore non-contiguous masking patterns or compression-aware masking, balancing between token coverage and compute cost. For SLMs trained with limited data or steps, efficient masking contributes to better token utilization and task alignment.Optimization Tricks (e.g., early exit, dynamic sparsity) Several optimization strategies are employed to reduce computational overhead during training and inference. Early exit mechanisms allow intermediate layers to produce outputs when confidence thresholds are met, minimizing unnecessary forward passes. Dynamic sparsity techniques, such as lottery ticket pruning and magnitude-based weight masking, enable models to shed redundant parameters during training while preserving performance. In the SLM setting, these approaches help reduce both memory and compute footprints, facilitating deployment on low-resource hardware. Combining these techniques with quantization and distillation further enhances the efficiency of SLM.

5. Model Optimization and Compression

5.1. Knowledge Distillation

5.1.1. The Distillation Process

5.1.2. Types of Knowledge Distillation

- Response-based KD: The student learns from the teacher’s final output logits.

- Feature-based KD: The student mimics intermediate representations or hidden activations.

- Relation-based KD: The student captures the relationships between different features or layers within the teacher.

5.2. Pruning Techniques

5.2.1. Types of Pruning

- Weight Pruning (Unstructured): Removes individual weights with small magnitudes, preserving the overall structure.

- Structured Pruning: Removes larger units such as entire neurons, attention heads, or layers for hardware-friendly speedups.

- Dynamic Pruning: Applies input-dependent masks during inference, enabling flexible sparsity without retraining.

5.3. Quantization and Weight-Sharing

5.3.1. Post-Training Quantization (PTQ)

- GPTQ [43]: Uses approximate second-order information to minimize quantization error layer-by-layer, achieving 3-4 bit quantization with minimal perplexity increase. GPTQ can quantize a 175B parameter model in approximately 4 GPU hours.

- SmoothQuant [46]: Migrates quantization difficulty from activations to weights by applying mathematically equivalent transformations, enabling efficient INT8 quantization of both weights and activations.

5.3.2. Quantization-Aware Training (QAT)

- Fake quantization: During training, weights and activations are quantized and immediately dequantized, introducing quantization noise while preserving gradient flow.

- Learnable parameters: Scale factors and zero-points can be learned jointly with model weights, optimizing the quantization scheme for each layer.

- Gradual precision reduction: Some approaches start with higher precision and progressively reduce bit-width during training for smoother convergence.

5.3.3. Weight-Sharing

| Technique | What it does | Sub-methods / Variants | Size Reduction | Accuracy / Perf Considerations | Computational Cost | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Distillation | Train a smaller student to mimic a larger teacher’s outputs/behaviors. | Traditional & sequence-level transfer (e.g., BabyLLaMA); multi-teacher; DistilBERT. | High (10×–100×) | Retains a high share of teacher quality; e.g., DistilBERT: 40% smaller, 60% faster, ∼97% of BERT NLU. | High | Create a capable SLM from an LLM; reduce inference cost while preserving quality. |

| Pruning | Remove unimportant parameters (weights/neurons/structures) to induce sparsity. | Unstructured (SparseGPT, Wanda); Structured (hardware-friendly); Adaptive structural (Adapt-Pruner). | Medium–High (50–90%) | Unstructured: high sparsity but hard to accelerate; Structured: direct speedups with larger accuracy hit; Adaptive: reported +1–7% accuracy gains. | Medium | Optimize an existing model to cut compute/memory while maintaining accuracy. |

| Quantization | Lower numerical precision of weights/activations to shrink memory and boost throughput. | PTQ, QAT; INT8, INT4/FP4/NF4 (QLoRA); GPTQ, AWQ. | Low–Medium (2×–8×); INT8 ≈ 2× | Minimal loss with QAT; PTQ can degrade on harder tasks; QLoRA (NF4) can match 16-bit fine-tuning quality. | Low–Med | Final deployment optimization; pair with PEFT for low-memory training/inference. |

| Architectural Optimization | Design inherently compact/efficient models instead of compressing a large one. | Lightweight (MobileBERT, TinyLLaMA); Streamlined attention (Mamba, RWKV, Hyena); NAS. | Varies (architecture-dependent) | Mamba: linear scaling, up to 5× higher throughput; Hyena: up to 100× faster than optimized attention at 64K sequence length. | High (R&D) | Build from scratch under strict latency/memory targets or to maximize throughput. |

| PEFT | Freeze base model; train small adapter parameters to adapt behavior efficiently. | LoRA, QLoRA (LoRA+quant, NF4), MiSS, DoRA, IA3, Prompt Tuning. | Adapter-only (base unchanged) | Often matches full fine-tuning; QLoRA enables fine-tuning a 65B model on a single 48GB GPU; MiSS is faster and more memory-efficient than LoRA. | Low | Domain/task adaptation under tight GPU memory; combine with quantization for efficiency. |

5.4. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT)

5.4.1. LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)

5.4.2. Adapters

5.4.3. BitFit

5.4.4. Prompt Tuning & Prefix Tuning

5.5. Inference Optimization Trade-offs: A Critical Analysis

5.5.1. The Latency-Accuracy Frontier

5.5.2. Memory-Accuracy Scaling Laws

- Superlinear resource scaling: Achieving each 10 percentage point gain in pass@1 accuracy on code generation tasks requires approximately 3–4× additional VRAM [50].

- Active parameter efficiency: IBM’s Granite 3.0 models demonstrate effective parameter utilization—the 1B model activates only 400M parameters at inference, while the 3B model activates 800M, minimizing latency while maintaining performance.

- Compression cliff: Research indicates that model compression exhibits graceful degradation up to a threshold, after which performance drops sharply. This cliff typically occurs when the student model falls below 10% of the teacher’s parameters [51].

5.5.3. Quantization vs. Pruning: Empirical Evidence

- Consistently outperforms pruning in preserving model fidelity, multilingual perplexity, and reasoning accuracy.

- AWQ (Activation-aware Weight Quantization) emerges as the recommended method for SLM compression.

- Maintains better generalization across diverse task types.

- Advantages diminish on complex knowledge and reasoning tasks (e.g., OpenBookQA).

- Reveals a disconnect between compression fidelity metrics (perplexity) and downstream task performance.

- Trends observed in LLMs (e.g., Wanda’s competitive performance to SparseGPT) do not generalize to SLMs.

5.5.4. Energy-Accuracy Trade-offs on Edge Devices

| Model Profile | Energy Consumption | Accuracy | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama 3.2 (optimized) | Medium | High | Balanced applications |

| TinyLlama | Low | Moderate | Battery-constrained IoT |

| Phi-3 Mini | High | High | Accuracy-critical tasks |

5.5.5. Hardware-Aware Optimization

5.5.6. The Compression-Robustness Tension

- Calibration sensitivity: Compressed models exhibit heightened sensitivity to calibration data selection. Suboptimal calibration can amplify capability degradation beyond what compression alone would cause [56].

- Error accumulation: Aggressive pruning or quantization can trigger abrupt underfitting, manifesting as sudden capability collapse rather than gradual degradation.

- Task-specific fragility: Models may retain benchmark performance while failing on distribution-shifted inputs, necessitating extensive robustness testing post-compression.

6. Applications and Deployment Strategies

6.1. On-Device Intelligence: The Edge Computing Revolution

6.2. Industry Use Cases

6.2.1. Healthcare

6.2.2. Finance

6.2.3. Retail and Manufacturing

| Industry | Use Case | Description | Key Benefits | Example SLMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Clinical Decision Support | Analyzes patient data to suggest diagnoses, treatment plans, and potential drug interactions. | Improved Accuracy, Enhanced Patient Privacy, Faster Diagnosis | BioMistral, Med-PaLM |

| Administrative Automation | Automates routine administrative tasks like scheduling appointments, managing patient records, and generating reports. | Increased Efficiency, Significant Cost Reduction, Reduced Human Error | General SLMs (fine-tuned) | |

| Drug Discovery | Scans vast amounts of scientific literature and molecular databases to identify potential drug targets, accelerate compound discovery, and predict efficacy. | Accelerated Research Speed, Lower Development Costs, Higher Success Rates | BioGPT | |

| Finance | Invoice Processing | Extracts and verifies data from financial documents, such as invoices, receipts, and purchase orders, for automated entry. | Improved Efficiency, Enhanced Accuracy, Reduced Manual Effort | Custom SLMs (financial) |

| Fraud Prevention | Analyzes real-time transaction patterns and historical data to detect and flag suspicious activities indicative of fraud. | Low Latency Detection, Stronger Security, Reduced Financial Loss | Custom SLMs (anomaly) | |

| Risk Assessment | Evaluates loan applications, credit scores, and market data to assess financial risk and make informed lending decisions. | Increased Speed, Greater Consistency, Objective Evaluation | Custom SLMs (credit) | |

| Retail | Personal Assistant | Provides personalized product recommendations, answers customer queries, and assists with shopping decisions based on user preferences. | Enhanced Personalization, Improved Customer Privacy, Increased Sales | Llama 4 Scout, Phi-4-mini |

| Predictive Maintenance | Analyzes sensor data from machinery and equipment to predict potential failures, scheduling maintenance proactively to prevent downtime. | Maximized Uptime, Reduced Operational Costs, Extended Equipment Lifespan | Custom SLMs (IoT) | |

| Supply Chain Optimization | Predicts demand fluctuations, optimizes inventory levels, and streamlines logistics for efficient supply chain management. | Greater Efficiency, Optimized Inventory, Reduced Waste | General SLMs (ERP) |

6.3. Cascaded and Hybrid SLM–LLM Systems

6.4. Empirical Case Studies

6.4.1. Healthcare: On-Device Clinical Reasoning

6.4.2. Finance: Real-Time Processing

6.4.3. Edge Computing Benchmarks

| Platform | Best Model | Tok/s | Power | Acc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi 4 | TinyLlama 1.1B | 4.2 | 3.8W | 58.3% |

| Jetson Orin | Phi-3-mini 3.8B | 28.7 | 15.2W | 72.1% |

| iPhone 14 Pro | Phi-4-mini (4-bit) | 12.4 | 2.1W | 68.9% |

| M2 MacBook | Llama 3.2 3B | 45.3 | 8.7W | 71.4% |

6.4.4. Lessons Learned

7. Trustworthiness, Safety, and Governance

7.1. The Responsible AI Framework for SLMs

7.2. Ethical Dilemmas in Compact Models

7.3. Mitigation Strategies

7.4. Open Research Challenges

8. Evaluation and Benchmarking

8.1. Key Benchmarks and Metrics

8.2. General Capabilities

8.3. Instruction-Following

8.4. Specialized Skills

8.5. Conversational Prowess

9. Limitations and Open Research Challenges

9.1. Performance–Size Tradeoff

9.2. Evaluation Gaps

9.3. Data Bias and Fairness

9.4. Security and Privacy

9.5. Deployment Risks

9.6. Sustainable and Responsible SLM Optimization

9.7. Hallucination and Factual Accuracy

9.8. Limitations of This Survey

10. Conclusion and Future Outlook

10.1. Synthesizing the State of SLMs

10.2. From SLMs to TRMs:

- Parameter efficiency through iteration. TRM demonstrates that generalization on structured reasoning tasks (e.g., ARC-AGI, Sudoku, or Maze benchmarks) can be achieved via repeated refinement rather than massive parameter scaling [71]. This mirrors a growing recognition that scaling inference depth may offer similar or greater benefits than scaling width, particularly for reasoning and algorithmic tasks [72].

- Task-specific inductive bias. While many SLMs aim for generality across language, coding, and multimodal reasoning [12,17], TRM is explicitly specialized for recursive, symbolic, and rule-based reasoning. This specialization demonstrates how model structure can outperform size when inductive biases align closely with task structure.

- Hybrid and modular systems. Future work may explore combining the lightweight transformer efficiency of SLMs with recursive refinement modules like TRM, yielding architectures that can dynamically adapt between fast general processing and deep iterative reasoning. Such modular hybridization could form the basis for more capable yet efficient reasoning-centric AI systems [12,29].

10.3. Future Directions: The Path to Ubiquitous, Specialized AI

Appendix A. List of Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| Model Types & Architectures | |

| AGI | Artificial General Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FFN | Feed-Forward Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MoE | Mixture of Experts |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NLU | Natural Language Understanding |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SLM | Small Language Model |

| SSM | State Space Model |

| Attention & Position Encoding | |

| GQA | Grouped-Query Attention |

| KV | Key-Value (cache) |

| MHA | Multi-Head Attention |

| MQA | Multi-Query Attention |

| RoPE | Rotary Position Embeddings |

| Training & Optimization Techniques | |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| DPO | Direct Preference Optimization |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

| KD | Knowledge Distillation |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| PEFT | Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning |

| PTQ | Post-Training Quantization |

| QAT | Quantization-Aware Training |

| QLoRA | Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| RLHF | Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback |

| SFT | Supervised Fine-Tuning |

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| Normalization & Regularization | |

| LayerNorm | Layer Normalization |

| RMSNorm | Root Mean Square Normalization |

| Benchmarks & Evaluation | |

| ARC | AI2 Reasoning Challenge |

| BBH | BIG-Bench Hard |

| GLUE | General Language Understanding Evaluation |

| GSM8K | Grade School Math 8K |

| MMLU | Massive Multitask Language Understanding |

| SQuAD | Stanford Question Answering Dataset |

| Hardware & Deployment | |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| FLOP | Floating Point Operation |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit |

| Data & Privacy | |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| PII | Personally Identifiable Information |

References

- Hosseini, Mohammad-Parsa; Lu, Senbao; Kamaraj, Kavin; Slowikowski, Alexander; Venkatesh, Haygreev C. Deep learning architectures. In Deep Learning: Concepts and Architectures; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. pages 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, John. The great divergence in ai: Scaling up vs. scaling down. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, Hugo; Lavril, Thibaut; Izacard, Gautier; Martinet, Xavier; Lachaux, Marie-Anne; Lacroix, Timothée; Rozière, Baptiste; Goyal, Naman; Hambro, Eric; Azhar, Faisal; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023a, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, Hugo; Martin, Louis; Stone, Kevin; Albert, Peter; Almahairi, Amjad; Babaei, Yasmine; Batta, Nikolay; Bhargava, Prajwal; Bhosale, Shruti; Bikel, Daniel M; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023b, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekar, Suriya; Olli, Sarthak; Salimb, Adil; Shah, Shital; Singh, Harkirat; Wang, Xin; Bubeck, Sébastien; Eldan, Ronen; Kalai, Adam Tauman; Lee, Yin Tat; et al. Textbooks are all you need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.11644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Yuan-Fang; Eldan, Ronen; Bubeck, Sébastien; Gunasekar, Suriya; Zeng, Yinpeng; Wang, Xin; Shah, Shital; Singh, Harkirat; Salim, Adil; Olli, Sarthak; et al. Textbooks are all you need ii: phi-1.5 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Google DeepMind Gemma Team Gemma: Open models from google deepmind. Google AI Blog. 2024. Available online: https://deepmind.google/technologies/gemma/.

- Jiang, Albert Q; Sablayrolles, Alexandre; Mensch, Arthur; Bamford, Chris; Bui, Devendra; Blechschmidt, François; Kilian, Joan; Lacroix, Timothée; Lacoste, Ludovic; Maillard, Pierre-Emmanuel; et al. Mistral 7b. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Jinze; Bai, Shuai; Cao, Yunfei; Chang, Xu; Chen, Jia; Chen, Kai; Chen, Kun; Chen, Peng; Cheng, Hao; Cui, Hao; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Mingjie; Diao, Shizhe; Lu, Ximing; Hu, Jian; Dong, Xin; Choi, Yejin; Kautz, Jan; Dong, Yi. Prorl: Prolonged reinforcement learning expands reasoning boundaries in large language models. arXiv. 2025a. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.24864.

- Subramanian, Shreyas; Elango, Vikram; Gungor, Mecit. Small language models (slms) can still pack a punch: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.06899. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xue; Gunasekar, Saurabh; Wang, Yuchen; Lu, Ximing; Singh, Amanpreet; Carreira, Joao; Kautz, Jan; Zoph, Barret; Dong, Yi. Phi-4-reasoning: A 14-billion-parameter reasoning model. arXiv. 2025a. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.21318.

- Google DeepMind. Gemma 3 technical report. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.19786.

- Touvron, Hugo; et al. Llama 3.3: Efficient large language models. Meta AI Blog. 2024. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-3-3/.

- Yang, An; Zhang, Baichuan; Bai, Bin; Hui, Binyuan; Zheng, Bo; Yu, Bowen. Qwen3 technical report Trained on 36T tokens, 119 languages, hybrid thinking modes. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09388.

- DeepSeek, AI. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning Distilled models 1.5B–70B with strong reasoning capabilities. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12948.

- Nguyen, Thanh; Lee, Han; Chandra, Rahul; Patel, Devansh; Song, Jihwan. Small language models: A survey of efficiency, architecture, and applications. arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.01356.

- Schreiner, Maximilian. Gpt-4 architecture, infrastructure, training dataset, costs, vision, moe. THE DECODER. 2024. Available online: https://the-decoder.com/gpt-4-architecture-datasets-costs-and-more-leaked/.

- Lu, Zhichun; Li, Xiang; Cai, Daoping. Small language models: Survey, measurements, and insights. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.15790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Will. Openai’s ceo says the age of giant ai models is already over Industry estimates suggest GPT-4 training costs exceeded $100 million. WIRED. 2023. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/openai-ceo-sam-altman-the-age-of-giant-ai-models-is-already-over/.

- Gu, Albert; Dao, Tri. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv. 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.00752.

- Jiao, Xiaoqi; Yin, Yichun; Shang, Lifeng; Jiang, Xin; Chen, Xiao; Li, Linlin; Wang, Fang; Liu, Qun. Tinybert: Distilling bert for natural language understanding. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics EMNLP 2020; 2020; pp. pages 4163–4174. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, Victor; Debut, Lysandre; Chaumond, Julien; Wolf, Thomas. Distilbert, a distilled version of bert: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Google DeepMind Team. Gemma: Open models based on gemini research and technology. arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.08295.

- Abdelfattah, Marah; et al. Phi-3.5-moe technical report: Towards efficient mixture-of-experts language models. Microsoft Research Technical Report, 2024a. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfattah, Mohamed; Lu, Ximing; Gunasekar, Saurabh; Singh, Amanpreet; Carreira, Joao; Dong, Yi. Phi-3: Scaling data quality for small language models. arXiv. 2024b. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.14219.

- Zhou, Han; Zhang, Bowen; Feng, Minheng; Du, Kun; Wang, Yanan; Zhang, Dongdong; Yang, Wei; Li, Qijun; Wang, Zhizheng. Data scaling laws in diffusion models. arXiv 2024a, arXiv:2403.04543. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, Jesse; Sap, Maarten; Marasović, Ana; Agnew, William; Ilharco, Gabriel; Groeneveld, Dirk; Mitchell, Margaret; Gardner, Matt. Documenting large webtext corpora: A case study on the colossal clean crawled corpus. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Hendrickx, Iris, Moschitti, Alessandro, Punyakanok, Vil, Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. pages 1286–1305. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2021.emnlp-main.98. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Ying; Zhang, Haoyu; He, Xin; Li, Yichong; Ren, Xiaojun. Data quality trumps quantity: Revisiting scaling laws for language model pretraining. arXiv. 2024b. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.13982.

- Bai, Jinxing; Zhang, Renjie; Wang, Xiaoyu; Chen, Jing; Gao, Fei; Chen, Yang; Qian, Weizhi. Qwen2: Scaling open language models with efficient training and reasoning. arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.10671.

- Wei, Jason; Tay, Yi; Bommasani, Rishi; Ritter, Kevin; Ma, Collins; Zoph, Kevin; Le, Quoc V; Chi, Ed H. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Long; Yang, Rui; Liu, Jianing; Zhang, Tianyu; Shen, Shuai; Han, Sheng; Yin, Xiangru; Fu, Zhuo; Xu, Xiao; Yan, Zhiying; et al. Starcoder2: Data meets code. arXiv 2024a, arXiv:2402.04018. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, Howard; Lee, Shiyuan; Chen, Kevin; Ouyang, Luyang; Wu, David; Shi, Xin; Peng, Hengfei; Xu, Long; Wang, Haining; Hao, Yifeng; et al. Let’s verify step by step. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10981. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Leo; Biderman, Stella; Black, Sid; Brown, Laurence; Foster, Chris; Golding, Daniel; Hoopes, Jeffrey; Kaplan, Kyle; McKenney, Shane; Muennighoff, Samuel; et al. The pile: An 800gb dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2101.00027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, Jack W; Borgeaud, Simon; Hoffmann, Jordan; Cai, Francis; Parisotto, Sebastian; Ring, John; Young, Karen; Rutherford, George; Cassassa, Aidan; Griffiths, Trevor; et al. Scaling language models: Methods, analysis of training and inference, and implications for large language models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.11446. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Katherine; Mu, Daphne; Raghunathan, Aditi; Liang, Percy; Hashimoto, Tatsunori. Deduplicating training data makes language models better. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, Volume 1, pages 5777–5792. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Jordan; Borgeaud, Simon; Mensch, Arthur; Buchatskaya, Elena; Cai, Francis; Ring, John; Parisotto, Sebastian; Thomson, Laura; Gulcehre, Kaan; Ravuri, Augustin; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Lichang; Li, Shiyang; Yan, Jun; Wang, Hai; Gunaratna, Kalpa; Yadav, Vikas; Tang, Zheng; Srinivasan, Vijay; Zhou, Tianyi; Huang, Heng; Jin, Hongxia. Alpagasus: Training a better alpaca model with fewer data. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, Subhabrata; Shen, Jiangjiang; Ma, Xiang; Dong, Yingxia; Zhang, Hao; Singh, Amandeep; Li, Ya-Ping; Wang, Zhizheng; Zhang, Tengyu; Chen, Xinyun; et al. Orca: Progressive learning from complex explanation traces of gpt-4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Wei-Lun; Li, Zhilin; Lin, Xingyu; Sheng, Ziyuan; Zeng, Zixuan; Wu, Hao; Li, Shoufa; Li, Jianbo; Xie, Zheng; Wu, Mengnan; et al. Openchat: Advancing open-source language models with mixed-quality data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.11235. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Collider: Dynamic token-level data filtering for efficient language model training. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11292. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xinyang; Lee, Hyunkyung; He, Ruochen; Lyu, Qiaozhu; Choi, Eunsol. The perils of data selection: Exploring the trade-off between data quality and diversity in instruction tuning. arXiv 2024b, arXiv:2402.18919. [Google Scholar]

- Frantar, Elias; Ashkboos, Saleh; Hoefler, Torsten; Alistarh, Dan. Gptq: Accurate post-training quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.17323. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Ji; Tang, Jiaming; Tang, Haotian; Yang, Shang; Dang, Xingyu; Han, Song. Awq: Activation-aware weight quantization for llm compression and acceleration. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2024, 6, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yuxuan; Kurz, Sebastian; Zhao, Wei. Revisiting pruning vs quantization for small language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2025;Systematic evaluation across 6 SLMs, 7 languages, 7 tasks; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2025.findings-emnlp.645/.

- Xiao, Guangxuan; Lin, Ji; Seznec, Mickael; Wu, Hao; Demouth, Julien; Han, Song. Smoothquant: Accurate and efficient post-training quantization for large language models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023; pp. 38087–38099. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; et al. Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Zhenzhong; Chen, Mingda; Goodman, Sebastian; Gimpel, Kevin; Sharma, Piyush; Soricut, Radu. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhe; Liu, Ming; Zhang, Tao. Quantization for reasoning models: An empirical study. Proceedings of COLM 2025, 2025; Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.04823.

- Label Your Data. Slm vs llm: Accuracy, latency, cost trade-offs 2025. Label Your Data Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://labelyourdata.com/articles/llm-fine-tuning/slm-vs-llm.

- Zhang, Wei; Chen, Li; Wang, Xiaomi; et al. Demystifying small language models for edge deployment. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2025). Association for Computational Linguistics Comprehensive edge deployment study from Beijing University, Cambridge, 2025; Xiaomi, Flower Labs. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2025.acl-long.718.pdf.

- RichMediaGAI. Slmquant: Benchmarking small language model quantization for practical deployment Empirical validation of LLM quantization transfer to SLMs. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2511.13023.

- Martinez, Carlos; Lee, Sung-Ho; Patel, Raj. Sustainable llm inference for edge ai: Evaluating quantized llms for energy efficiency, output accuracy, and inference latency quantized LLMs on Raspberry Pi 4 across 5 datasets. In ACM Transactions on Internet of Things; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Research. Advances to low-bit quantization enable llms on edge devices LUT Tensor Core achieving 6.93x speedup. Microsoft Research Blog. 2025. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/advances-to-low-bit-quantization-enable-llms-on-edge-devices/.

- Liu, Yang; Zhang, Hao; Chen, Wei. Inference performance evaluation for llms on edge devices with a novel benchmarking framework and metric Introduces MBU metric for edge LLM inference. arXiv. 2025b. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.11269.

- Chen, Yuchen; Li, Wei; Zhang, Ming. Preserving llm capabilities through calibration data curation: From analysis to optimization Impact of calibration data on compressed model capabilities. arXiv. 2025a. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.10618.

- Kim, Jongwoo; Park, Seonghyun; Lee, Donghyun. Recover-lora: Data-free accuracy recovery of degraded language models. Proceedings of EMNLP 2025 Industry Track. Association for Computational Linguistics LoRA-based recovery for compressed SLMs, 2025; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2025.emnlp-industry.164.pdf.

- Labrak, Yanis; Bazoge, Adrien; Morin, Emmanuel; Gourraud, Pierre-Antoine; Rouvier, Mickaël; Dufour, Richard. Biomistral: A collection of open-source pretrained large language models for medical domains. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10373. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, Karan; Azizi, Shekoofeh; Tu, Tao; Mahdavi, S. Sara; Wei, Jason; Chung, Hyung Won; Scales, Nathan; Tanwani, Ajay; Cole-Lewis, Heather; Pfohl, Stephen; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Renqian; Sun, Linfeng; Xia, Yingce; Qin, Tao; Zhang, Sheng; Poon, Hoifung; Liu, Tie-Yan. Biogpt: Generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23(6), bbac409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhiyuan; Touvron, Hugo; Wightman, Ross; Lavril, Thibaut; Scialom, Thomas; Joulin, Armand; LeCun, Yann. Llama 4: Advancing open-weight large language models. arXiv. 2025b. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.11825.

- Thompson, Sarah; Gupta, Raj; Williams, David. Medicine on the edge: Comparative performance analysis of on-device llms for clinical reasoning. ResearchGate. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388963697.

- Chen, Hao; Patel, Ankit; Lee, Sung. Small language models in financial services: A deployment study Fine-tuned Mistral 7B for financial document processing. arXiv 2025c. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Albert Q.; Lambert, Nathan; Bekman, Stas; Von Platen, Patrick; Wolf, Thomas; Rush, Alexander M. Mistral next: Enhancing efficiency and reasoning in compact language models. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.09092.

- Face, Hugging. Open llm leaderboard. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/spaces/open-llm-leaderboard/open_llm_leaderboard.

- Zheng, L.; et al. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrycks, D.; et al. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbe, K.; et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wenxuan; Zheng, Fangyu; Chen, Jing; Wang, Haotian; Sun, Yulong; Wang, Bin; Yang, Xiaoxia. Transmamba: Flexibly switching between transformer and mamba. arXiv. 2025b. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.24067.

- Jolicoeur-Martineau, Alex; Gontier, Nicolas; Ben Allal, Loubna; von Werra, Leandro; Wolf, Thomas. Tiny recursive models (trm): Recursive reasoning with small language models. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.04871.

- Belcak, Peter; Heinrich, Greg; Diao, Shizhe; Fu, Yonggan; Dong, Xin; Lin, Yingyan; Molchanov, Pavlo. Small language models are the future of agentic ai. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.02153.

| Model | Size | Genesis | Architecture | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TinyBERT [22] | Ultra-small | Distilled | Dense | Latency |

| DistilBERT [23] | Small | Distilled | Dense | Memory |

| Llama 3.2 1B [14] | Small | From-Scratch | Dense | Latency |

| Phi-4-mini 3.8B [12] | Medium | From-Scratch | Dense | Task-Specialized |

| Mistral 7B [8] | Medium | From-Scratch | Dense | Latency |

| Gemma 2 9B [24] | Medium | From-Scratch | Dense | Task-Specialized |

| Mamba-3B [21] | Medium | From-Scratch | SSM | Latency |

| Phi-3.5-MoE [25] | Large | From-Scratch | Sparse/MoE | Memory |

| Phi-4 14B [12] | Large | From-Scratch | Dense | Task-Specialized |

| DeepSeek-R1-7B [16] | Medium | Distilled | Dense | Task-Specialized |

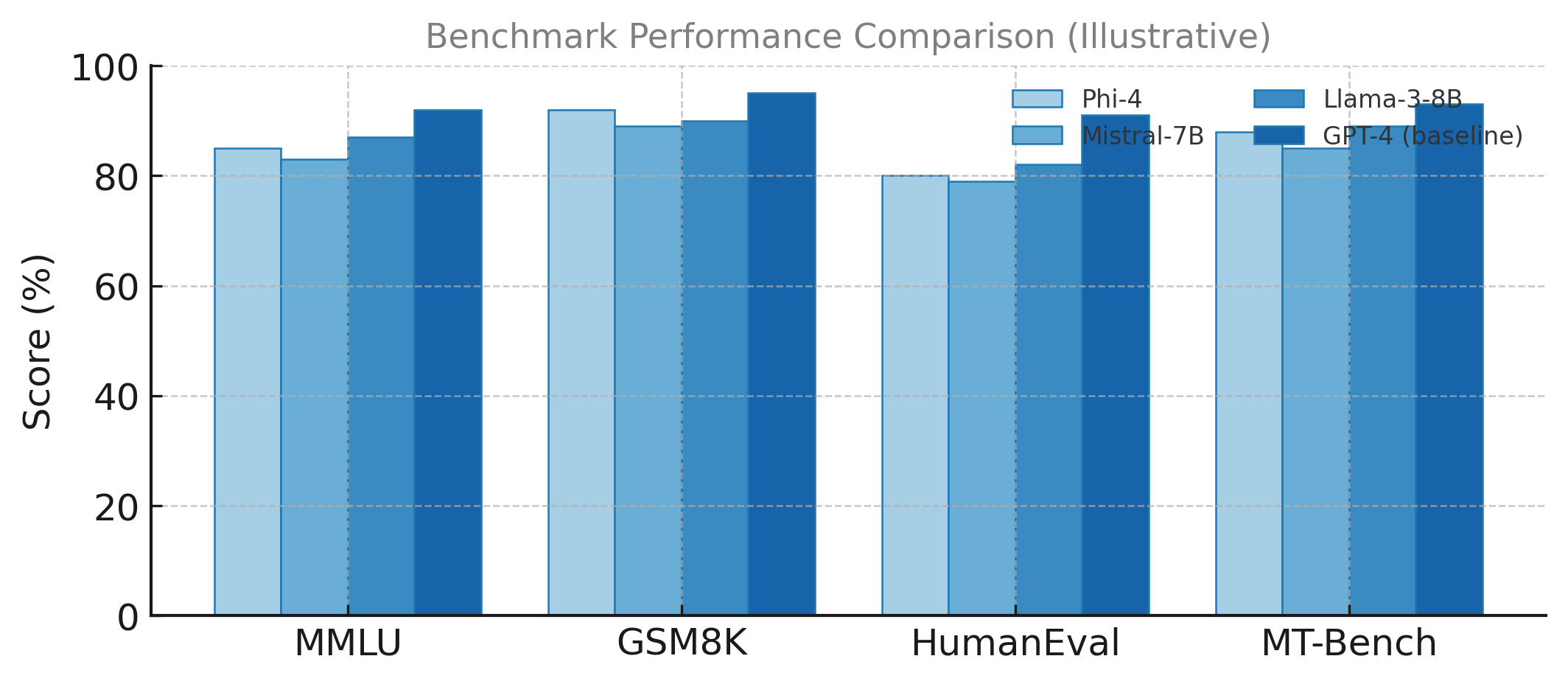

| Model | Parameters | MMLU | GSM8K | HumanEval | MT-Bench |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLMs | |||||

| Phi-4-reasoning-plus | 14B | 84.8 | 93.1 | 84.7 | 9.1 |

| Phi-4-mini-flash-reasoning | 3.8B | 70.5 | 85.2 | 60.3 | 8.5 |

| Llama 4 Scout | 17B | 82.3 | 88.4 | 75.6 | 9.0 |

| Gemma 3n | 3B | 76.8 | 82.7 | 55.9 | 8.7 |

| Qwen3 | N/A | 84.5 | 90.2 | 82.1 | 9.0 |

| Magistral Medium | N/A | 81.2 | 87.6 | 78.4 | 8.8 |

| Devstral Small 1.1 | N/A | 68.9 | 76.3 | 85.3 | 7.9 |

| LLMs | |||||

| Llama 3.1 405B | 405B | 86.6 | 95.1 | 80.5 | 8.99 |

| GPT-4o | ∼1.8T (MoE) | 88.7 | 92.95 | 90.2 | 9.32 |

| Mixtral 8x7B | 46.7B/12.9B | 70.6 | 74.4 | 40.2 | 8.30 |

| GPT-3.5 | 175B | 70.0 | 57.1 | 48.1 | 8.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).