Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

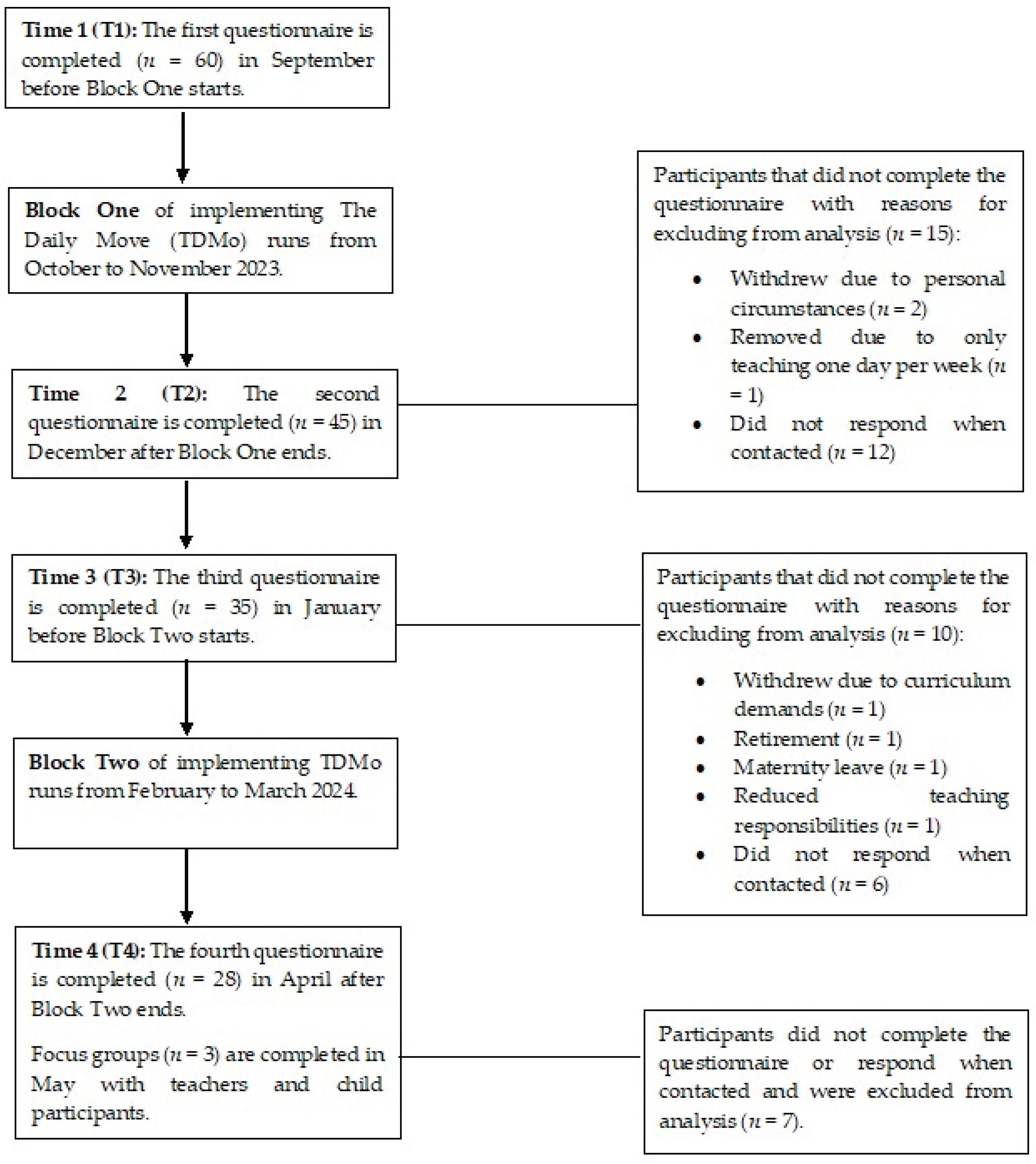

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. TDMo Implementation

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

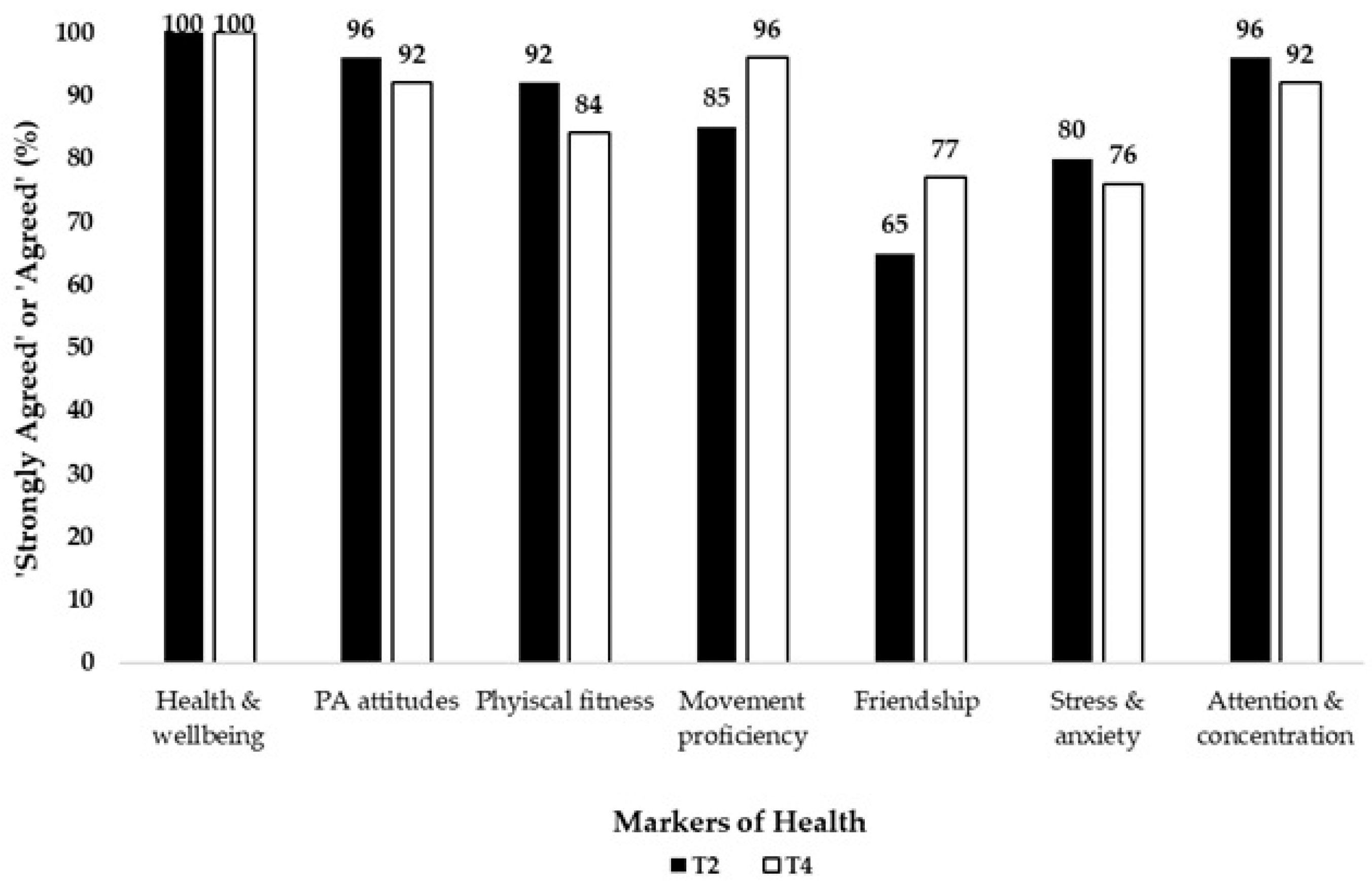

3.1. Effectiveness

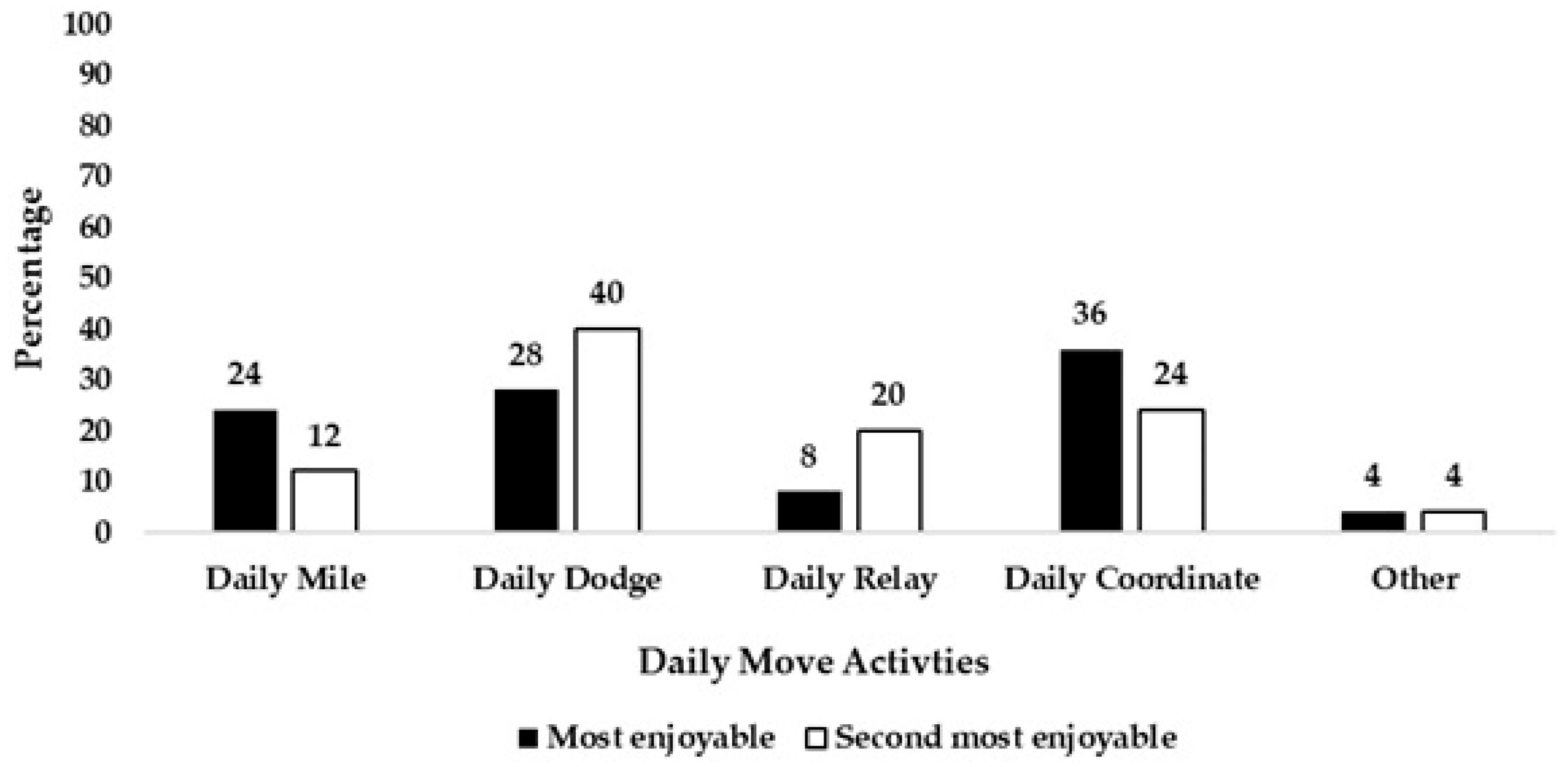

3.2. Adoption

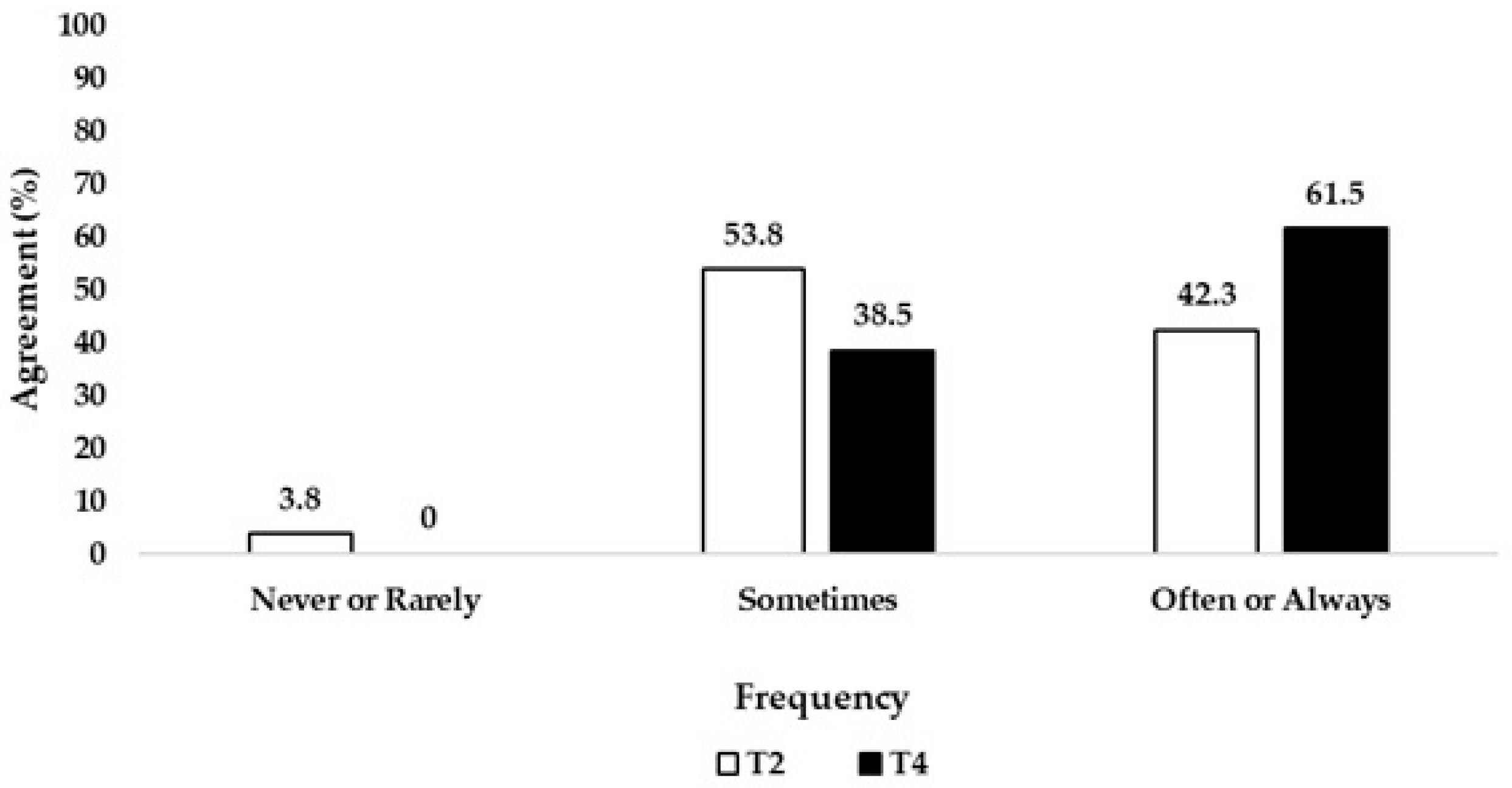

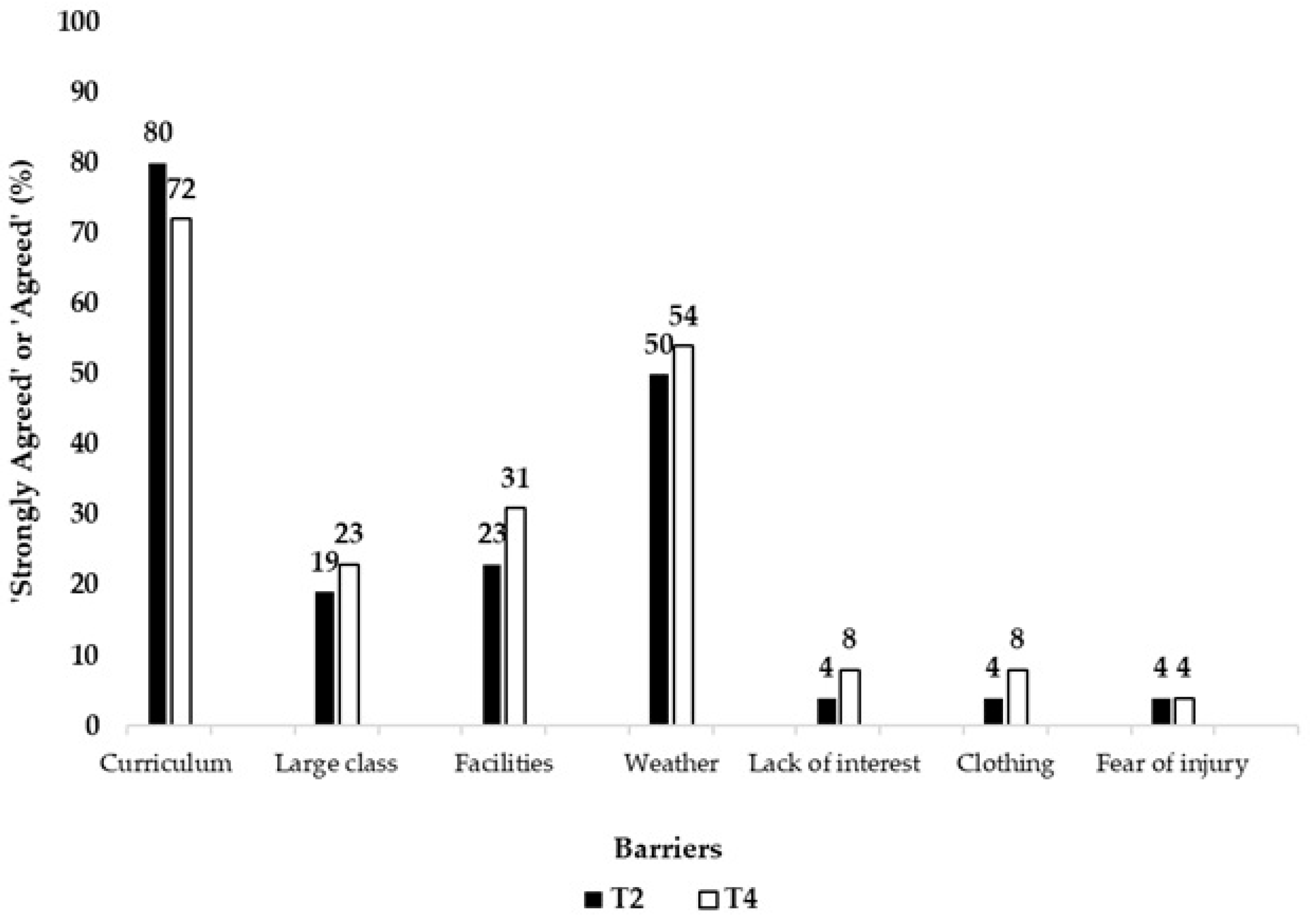

3.3. Implementation

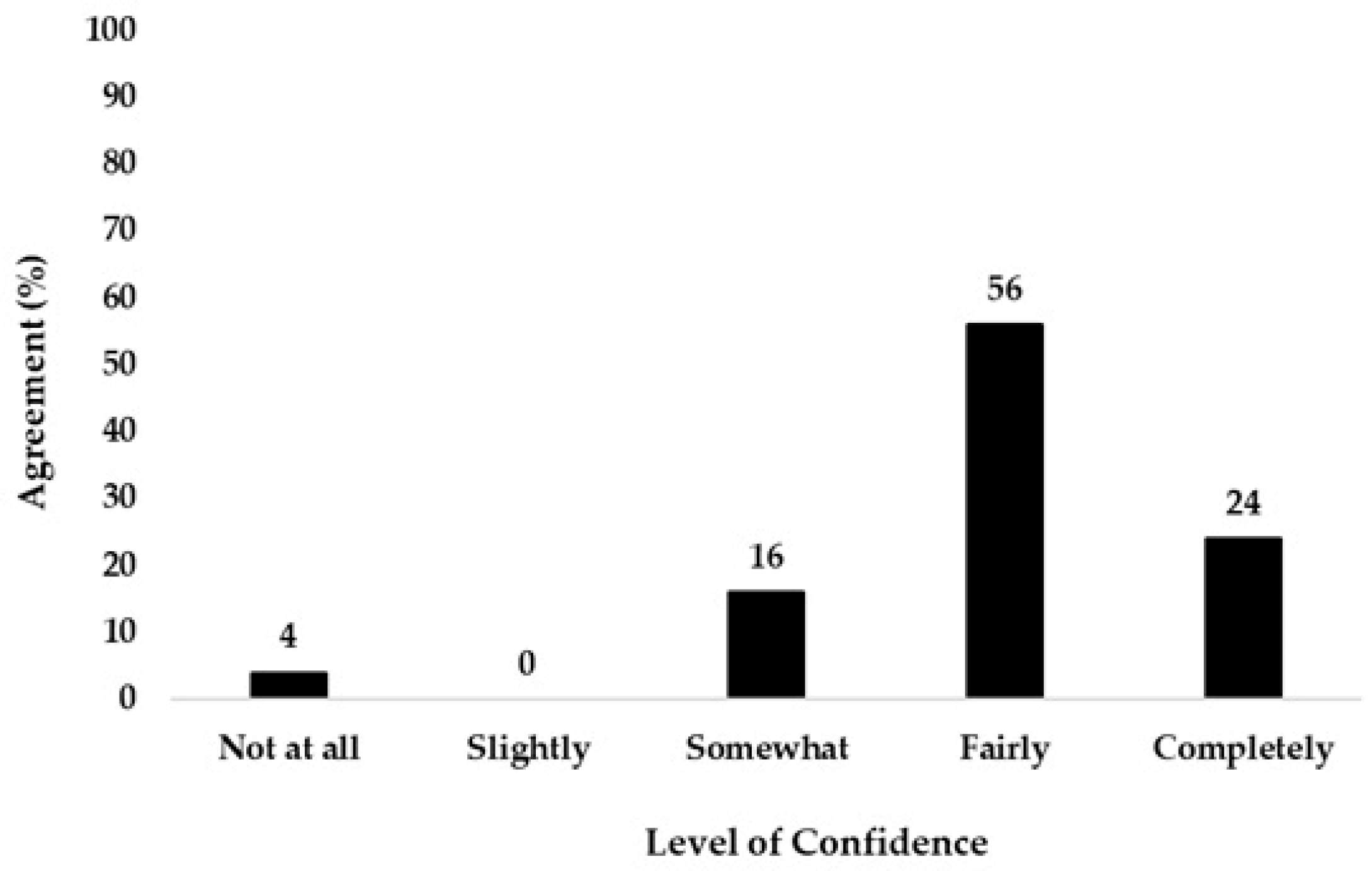

3.4. Maintenance

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TDM | The Daily Mile |

| TDMo | The Daily Move |

| PA | Physical activity |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| CRF | Cardiorespiratory fitness |

| FMS | Fundamental movement skills |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| T | Time |

References

- Hanna, L.; Burns, C.; O'Neill.; Bolger, L.E.; Coughlan, E. Comparing the impact of “The Daily Mile™” vs. a modified version on Irish primary school children's engagement and enjoyment in structured physical activity. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2025, 7, 1550028. [CrossRef]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Gorber, S.C.; Kho, M.E.; Sampson, M.; Tremblay, M.S. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41(6), S197-S239. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Department of Health (Ireland). Every Move Counts. National Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for Ireland; Health Service Executive: Dublin, Ireland, 2024.

- Woods, C.B.; NG, K.W.; Britton, U.; McCelland, J.; O’Keefe, B.; Sheikhi, A.; McFlynn, P.; Murphy, M.H.; Goss, H.; Behan, S.; Philpott, C.; Lester, D.; Adamakis, M.; Costa, J.; Coppinger, T.; Connolly, S.; Belton, S.; O’Brien, W. The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity Study 2022 (CSPPA 2022). Physical Activity for Health Research Centre, Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick: Limerick, Ireland; Sport Ireland and Healthy Ireland: Dublin, Ireland; Sport Northern Ireland: Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2023.

- Carlin, A.; Connolly, S.; Redpath, T.; Belton, S.; Coppinger, T.; Cunningham, C.; Donnelly, A.; Dowd, K.; Harrington, D.; Murtagh, E.; Ng, K.; O’Brien, W.; Rodriguez, L.; Woods, C.; McAvoy, H.; Murphy, M. Results from Ireland North and South’s 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents. JESF 2024, 22, 66-72. [CrossRef]

- Starting School. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/primary-and-post-primary-education/going-to-primary-school/starting-primary-school/#:~:text=Schools%20hours%20and%20days&text=Primary%20schools%20may%20reduce%20the,(commonly%20called%20first%20class) (accessed on 08th of January 2026).

- World Health Organisation. Promoting Physical Activity in the Education Sector; World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018.

- What is The Daily Mile? Available online: https://www.thedailymile.ie/the-daily-mile/about-the-daily-mile/ (accessed on 08th of January 2026).

- Global Community. Available online: https://www.thedailymile.ie/our-community/global-community/ (accessed on 08th of January 2026).

- Brustio, P.R.; Mulasso, A.; Lupo, C.; Massasso, A.; Rainoldi, A.; Boccia, G. The Daily Mile is able to improve cardiorespiratory fitness when practiced three times a week. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(6), 2095. [CrossRef]

- Chesham, R.A.; Booth, J.N.; Sweeney, E.L.; Ryde, G.C.; Gorely, T.; Brooks, N.E.; Moran, C.N. The Daily Mile makes primary school children more active, less sedentary and improves their fitness and body composition: a quasi-experimental pilot study. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 64. [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, M.; Slot-Heijs, J.J.; Prins, R.G.; Singh, A.S. The effect of The Daily Mile on primary school children’s aerobic fitness levels after 12 weeks: A controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(7), 2198. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072198.

- Dring, K.J.; Hatch, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Morris, J.G.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Cooper, S.B. Effect of 5-weeks participation in The Daily Mile on cognitive function, physical fitness, and body composition in children. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), 14309. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Dring, K.J.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Cooper, S.B. Activity patterns of primary school children during participation in The Daily Mile. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1), 7462. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, L.; Burns, C.; O’Neill, C.; Coughlan, E. Evaluating the perceived health-related effectiveness of ‘The Daily Mile’ initiative in Irish primary schools. Healthcare 2024, 12(13), 1284. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Milnes, L.J.; Mountain, G. How ‘The Daily Mile™ works in practice: A process evaluation in a UK primary school. J. Child Health Care 2019, 24(4), 544-559. [CrossRef]

- Arkesteyn, A.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Van Damme, T. Mental health outcomes of the Daily Mile in elementary school children: a single-arm pilot study. CAMH 2022, 27(4), 361-368. [CrossRef]

- Marchant, E.; Todd, C.; Stratton, G.; Brophy, S. The Daily Mile: Whole-school recommendations for implementation and sustainability. A mixed-methods study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(2), e0228149. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Dring, K.J.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Sarkar, M.; Morris, J.G.; Cooper, S.B. The Daily Mile™: Acute effects on children’s cognitive function and factors affecting their enjoyment. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 57, 102047. [CrossRef]

- Malden, S.; Doi, L. The Daily Mile: teachers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to the delivery of a school-based physical activity intervention. BMJ Open 2019, 9(3), e027169. [CrossRef]

- Scannell, J.; Murphy, F. ‘Maybe add something to it?’: building on The Daily Mile to enhance enjoyment and engagement. Education 2024, 52(8), 1527-1541. [CrossRef]

- Herlitz, L.; MacIntyre, H.; Osborn, T.; Bonell, C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, L.E.; Bolger, L.A.; O’Neill, C.; Coughlan, E.; O’Brien, W.; Lacey, S.; Burns, C. The effectiveness of two interventions on fundamental movement skill proficiency among a cohort of Irish primary school children. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2019, 7(2), 153-179. [CrossRef]

- Merrotsy, A.; McCarthy, A.L.; Flack, J.; Lacey, S.; Coppinger, T. Project Spraoi: a two-year longitudinal study on the effectiveness of a school-based nutrition and physical activity intervention on dietary intake, nutritional knowledge and markers of health of Irish schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22(13), 2489-2499. [CrossRef]

- O'Byrne, Y.; Dinneen, J.; Coppinger, T. Translating interventions from research to reality: insights from Project Spraoi, an Irish multicomponent school-based health-promotion Intervention. Ir. J. Educ. 2023, 46(1), 1-28. http://www.erc.ie/ije.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55(1), 68. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89(9), 1322-1327. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Harden, S.M.; Gaglio, B.; Rabin, B.; Smith, M.L.; Porter, G.C.; Ory, M.G.; Estabrooks, P.A. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 64. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Toussaint, H.M.; Van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E.A. Translating the PLAYgrounds program into practice: a process evaluation using the RE-AIM framework. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16(3), 211-216. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.; Rush, E.; Lacey, S.; Burns, C.; Coppinger, T. Project Spraoi: two year outcomes of a whole school physical activity and nutrition intervention using the RE-AIM framework. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2019, 38(2), 219-243. [CrossRef]

- Smedegaard, S.; Brondeel, R.; Christiansen, L.B.; Skovgaard, T. What happened in the ‘Move for Well-being in School’: a process evaluation of a cluster randomized physical activity intervention using the RE-AIM framework. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 159. [CrossRef]

- Golzar, J.; Noor, S.; Tajik, O. Convenience sampling. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2022, 1(2), 72-77. [CrossRef]

- Measures to address educational disadvantage. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/the-irish-education-system/measures-to-address-educational-disadvantage/ (accessed on 20th December 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3(2), 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, L.G.; Johnson, J. Interviewing young children: Explicating our practices and dilemmas. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15(6), 821-831. [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Vicedo, J.C.; Prieto-Ayuso, A.; Pérez, S. L.; Martínez-Martínez, J. Active breaks and cognitive performance in pupils: A systematic review. Apunts Educ. Fis. Esports 2021, 146, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.M.; Duncan, M.J.; Clark, C.C.; Eyre, E.L. Exploring the Acute Effects of the Daily Mile™ vs. Shuttle Runs on Children’s Cognitive and Affective Responses. Sports 2022, 10, 142. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.L.; Daly-Smith, A.; Archbold, V.S.; Wilkins, E.L.; McKenna, J. The Daily Mile™ initiative: Exploring physical activity and the acute effects on executive function and academic performance in primary school children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101583. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Almagro, B.J.; Tamayo-Fajardo, J.A.; Sáenz-López, P. Complementing the self-determination theory with the need for novelty: motivation and intention to be physically active in physical education students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1535. [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, B.D.; Jackson, B.; Beauchamp, M.R. The Effects of Variety and Novelty on Physical Activity and Healthy Nutritional Behaviors. In Advances in Motivation Science, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018; pp 169–202.

- Yli-Piipari, S.; Watt, A.; Jaakkola, T.; Liukkonen, J.; Nurmi, J.E. Relationships between physical education students’ motivational profiles, enjoyment, state anxiety, and self-reported physical activity. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2009, 8(3), 327-336. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3763276/.

- Turner, L.; Calvert, H.G.; Carlson, J.A. Supporting teachers’ implementation of classroom-based physical activity. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sport. Med. 2019, 4(17), 165-172. [CrossRef]

- Cassar, S.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Naylor, P.J.; Van Nassau, F.; Contardo Ayala, A.M.; Koorts, H. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 267-285. [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327-350. [CrossRef]

- Hanckel, B.; Ruta, D.; Scott, G.; Peacock, J.L.; Green, J. The Daily Mile as a public health intervention: a rapid ethnographic assessment of uptake and implementation in South London, UK. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.; Van Der Horst, K.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Kremers, S.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth–a review and update. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8(2), 129-154. [CrossRef]

- Belton, S.; Britton, Ú.; Murtagh, E.; Meegan, S.; Duff, C.; McGann, J. Ten years of ‘Flying the flag’: an overview and retrospective consideration of the active school flag physical activity initiative for Children—design, development & evaluation. Children 2020, 7(12), 300. [CrossRef]

- Active School: More Schools, More Active, More Often. Available online: https://activeschoolflag.ie/ (accessed on 22nd December 2025).

- Primary school enrollment figures. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/the-irish-education-system/measures-to-address-educational-disadvantage/ (accessed on 22nd December 2025).

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Classroom behaviour | ‘It just works out better for everyone in the classroom if they have a movement break, and if they don't, you know about it. Their concentration is gone, they just need to get up and move' (Teacher). |

| Engaging inactive children | ‘It is the only exercise that some children get all day. Some children go home and they're inside for the rest of the day. It was great to see children that don't get much exercise, getting some exercise every day' (Teacher). |

| ‘It is very helpful for children that don't really get to move around a lot' (Child). | |

| Leadership skills | ‘My class really enjoyed being the teacher. For example, one boy led a taekwondo lesson, and since they're only seven years old, it was brilliant to see. Others taught Irish dancing, or anything that they were a master of themselves. It really got everybody involved and they felt great about it’ (Teacher). |

| Developing positive habits | ‘It's lifelong learning that you're getting them in the habit of this, that you need to do this every day. And you know without realising it they're learning that' (Teacher). |

| Social skills | You’re socialising with people, and you're running around and you're playing and you're talking' (Child). |

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Prioritising physical activity | ‘A higher emphasis needs to be placed on academics, on The Department of Education, on those people who have the authority, or even school staff, to realise that you will get a bigger input from the children and get more benefits if we reverse the current focus or priorities, and realise that the provision of physical activity should be as much of a priority as other subjects in schools’. |

| TDMo leader | ‘I try to sell it to other teachers. When we were doing the run around Europe and we were going running around the school for 15 minutes, some teachers thought that it took too much time and did not want to do it that day. I recommended giving children something to do when they're on their walk or run, that involves practicing something in geography or practicing something in English’. |

| Theme | Quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoyable | ‘You get to move and run around before you go back inside. It's very fun because I like moving around’ (Child). | |

| Variety and novelty | ‘I prefer doing different things instead of doing something over and over. Doing the same thing gets boring because you already know what it feels like' (Child). | |

| Innovative teachers | ‘There's so much you can do within a square meter. I have these low windowsills in school, and if it's raining, I think of different things we can do on the windowsills. We step up and down off the windowsill, and we do tricep dips on the windowsill' (Teacher). | |

| Overcoming curriculum demands | ‘With regards to the curriculum, there is always time to go out to play and run, and the kids will always get a bigger benefit out of that than any lesson in the curriculum' (Teacher). | |

| Autonomy and choice | ‘I enjoy it because you can play your favourite sport. It is more enjoyable than someone else picking it for you’ (Child). | |

| Outdoor vs indoor delivery | ‘I like it outside because I can get more air when I’m out of breath. I think it is more enjoyable than doing it in the classroom’ (Child). | |

| ‘Delivering it inside is absolutely possible, and they love it. But in terms of clearing the air in the room, certainly, my class prefer to go outside’ (Teacher). |

| Themes | Quote |

|---|---|

| Multiple resources | ‘I love having so many resources and the opportunity for each child to have a ball. That's a dream - every child having a ball to use for whatever activity you're doing' (Teacher). |

| ‘Videos are really helpful when you're trying to teach the kids, because sometimes, when you're reading the instructions for a game off a document it can be difficult to understand’ (Teacher). | |

| Government support | 'I think the people making the decisions on funding lack an understanding of what schools really need on the ground. There's no thought for how to integrate physical activity into the daily routine as a basic necessity. It's health and safety first, with physical activity treated as a bonus' (Teacher). |

| Enduring impact | ‘I think we're in a pattern now of doing it. I think they love it. There are huge benefits from it, and I enjoy doing it with them. So, I think I'll just keep doing it. I’d like to continue doing with them’ (Teacher). |

| Result of ceasing participation | ‘I would feel disappointed and sad because I like doing it and its fun’ (Child). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).