Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

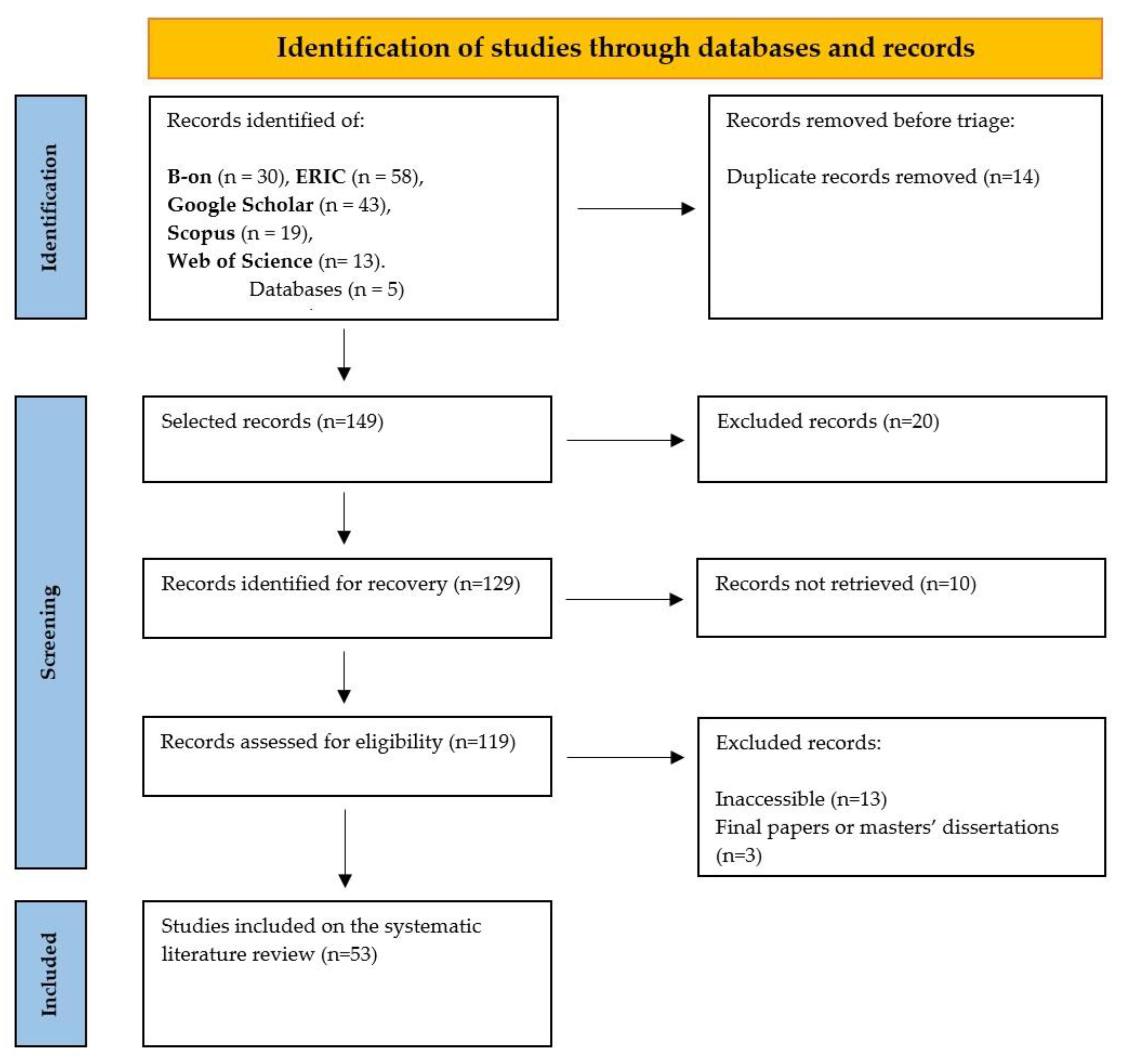

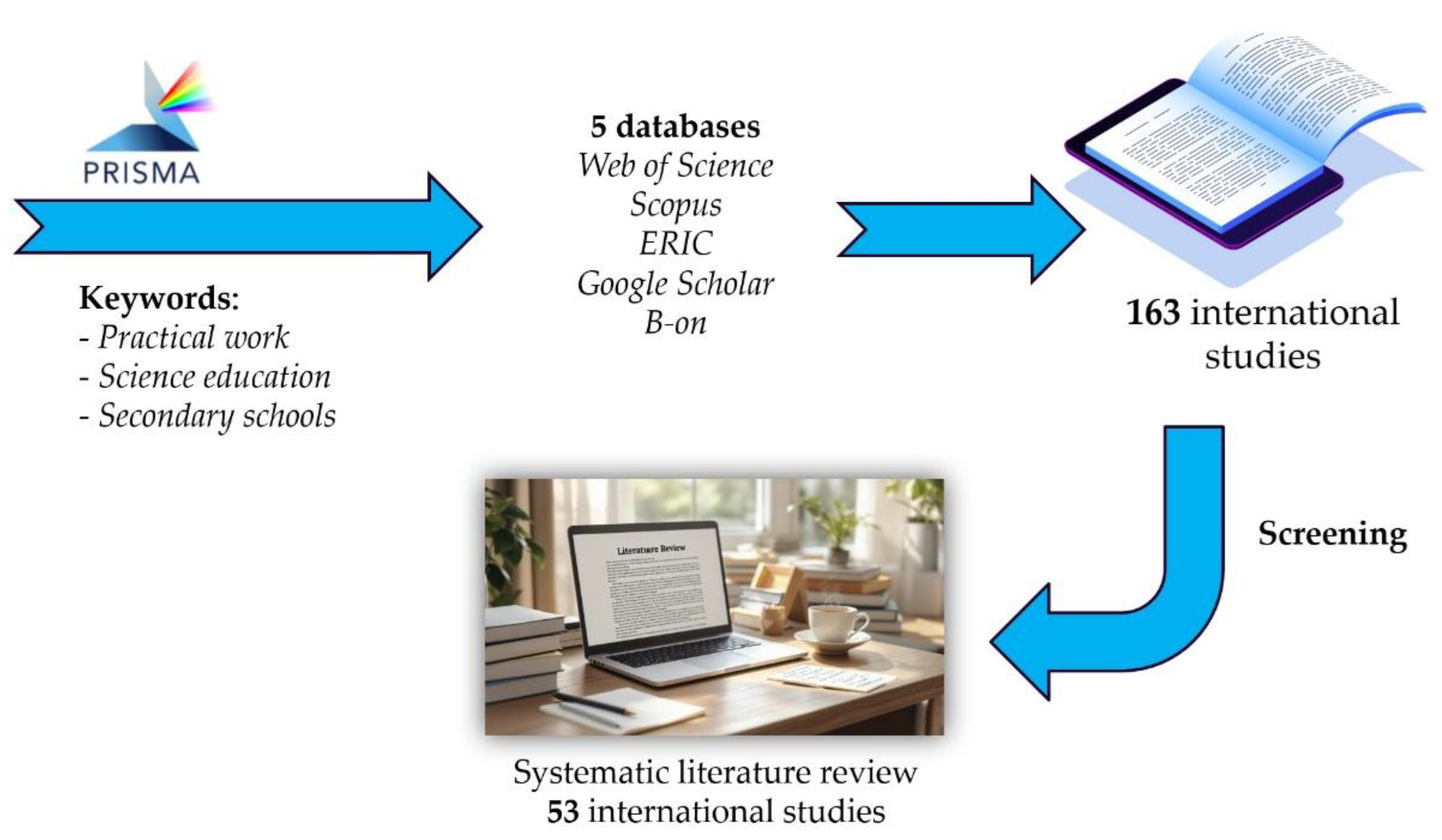

2.1. Systematic Literature Review on Practical Work

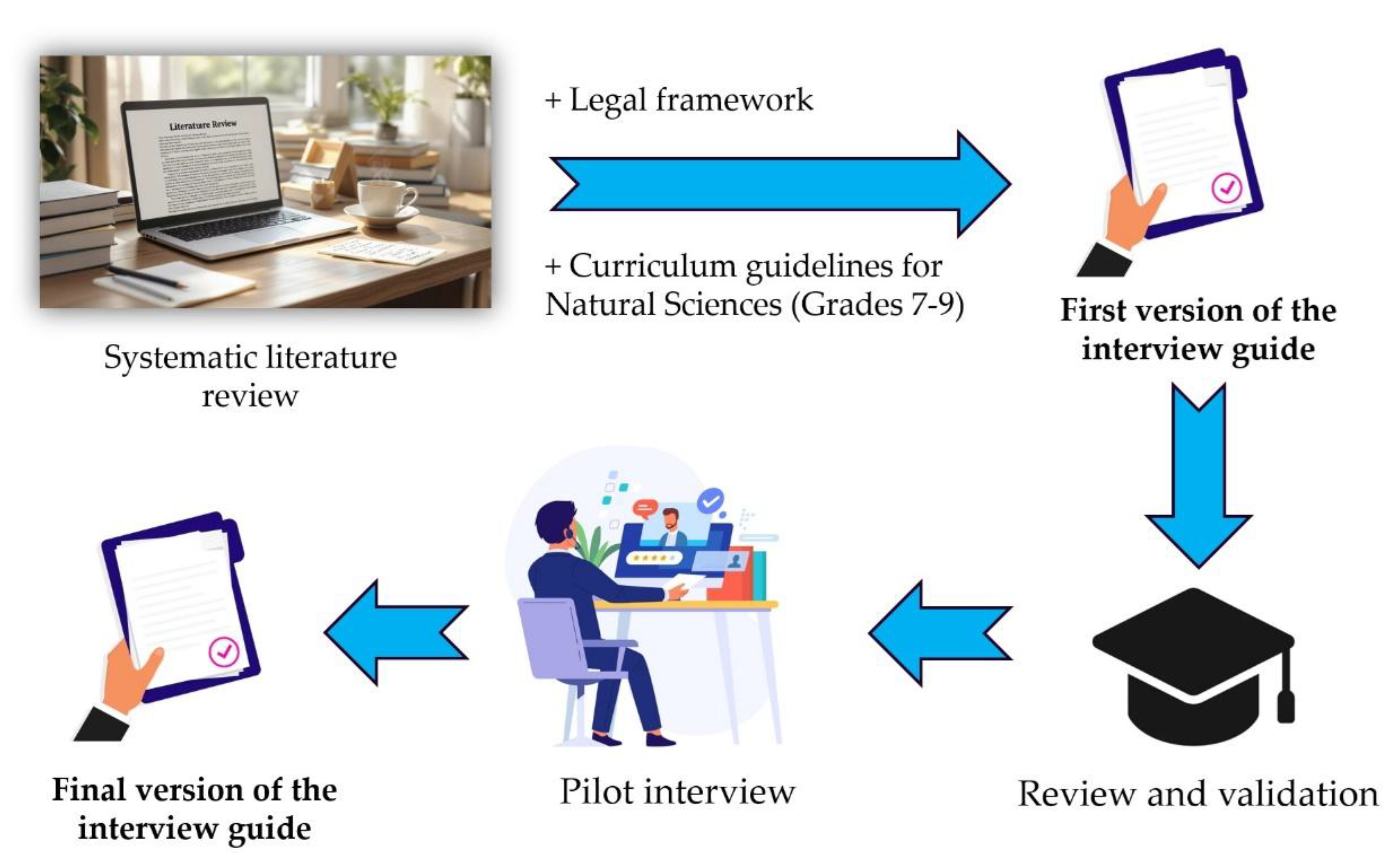

2.2. Design of the Interview Guide

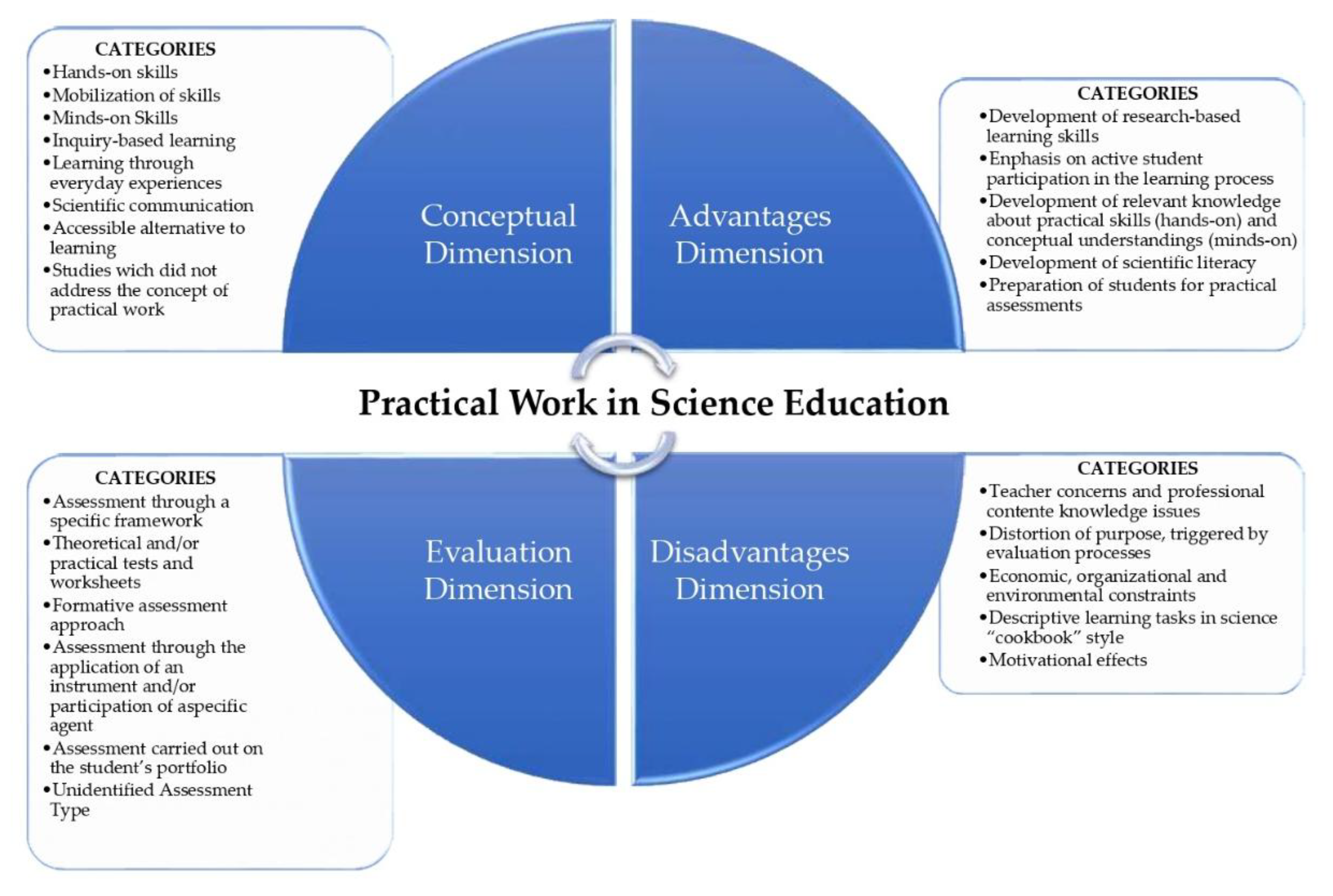

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EL | Essential Learnings |

| IPA | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PW | Practical Work |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SPECS | Student Profile at the End of Compulsory Schooling |

References

- Abrahams, I., & Reiss, M. (2012). Practical work: Its effectiveness in primary and secondary schools in England. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(8), 1035-55. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I., Reiss, M., & Sharpe, R. (2013). The assessment of practical work in school science. Studies in Science Education, 49(2), 209–51. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I., Reiss, M., & Sharpe, R. (2014). The impact of the ‘Getting Practical: Improving Practical Work in Science’ continuing professional development programme on teachers’ ideas and practice in science practical work. Research in Science and Technological Education, 32(3), 263-80. [CrossRef]

- Adamu, S., & Achufusi-Aka, N.N. (2020). Extent of integration of practical work in the teaching of chemistry by secondary schools teachers in Taraba State. UNIZIK Journal of STM Education, 3(2), 63-75. https://journals.unizik.edu.ng/index.php/jstme.

- Akuma, F., & Callaghan, R. (2019). Teaching practices linked to the implementation of inquiry-based practical work in certain science classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(1), 64-90. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J., & Enghag, M. (2017). The relation between students’ communicative moves during laboratory work in physics and outcomes of their actions. International Journal of Science Education, 39(2), 158–180. [CrossRef]

- Bohloko, M., Makatjane, T. J., George, M. J., & Mokuku, T. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of using youtube videos in teaching the chemistry of group i and vii elements in a high school in Lesotho. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 23(1), 75–85. [CrossRef]

- Bonito, J., Morgado, M., Silva, M., Figueira, D., Serrano, M., Mesquita, J., & Rebelo, H. (2014a). Metas Curriculares - Ensino Básico - Ciências Naturais, 5.º, 6.º, 7.º e 8.º anos. Ministério da Educação e Ciência. http://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ficheiros/eb_cn_metas_curriculares_5_6_7_8_ano_0.pdf.

- Bonito, J., Morgado, M., Silva, M., Figueira, D., Serrano, M., Mesquita, J., & Rebelo, H. (2014b). Metas Curriculares - Ensino Básico - Ciências Naturais 9.º ano. Ministério da Educação e Ciência. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ficheiros/metas_curriculares_ciencias_naturais_9_ano_0.pdf.

- Costa, F., Paz, A., Pereira, C., Cruz, E., Soromenho, G., & Viana, J. (2022). Relatório de avaliação da implementação das aprendizagens essenciais. Instituto de Educação da Universidade de Lisboa. http://www.dge.mec.pt/noticias/relatorio-de-avaliacao-da-implementacao-das-aprendizagens-essenciais.

- Anza, M., Bibiso, M., Mohammad, A., & Kuma, B. (2016). Assessment of factors influencing practical work in chemistry: A case of secondary schools in Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Education and Management Engineering, 6(6), 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Babalola, F. E., Lambourne, R. J., & Swithenby, S. J. (2020). The real aims that shape the teaching of practical physics in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(2), 259–278. [CrossRef]

- Danmole, B.T. (2012). Biology teachers’ views on practical work in senior secondary schools of South Western Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Davies, A., Fidler, D., & Gorbis, M. (2020). Future work skills 2020. In Future Work Skills 2020 Report (pp. 1–19). Institute for the Future for the University of Phoenix Research Institute. https://legacy.iftf.org/uploads/media/SR-1382A_UPRI_future_work_skills_sm.pdf.

- Dourado, L. (2001). Trabalho Prático, Trabalho Laboratorial, Trabalho de Campo e Trabalho Experimental no Ensino das Ciências – contributo para uma clarificação de termos. In A. Veríssimo, M. A. Pedrosa & R. Ribeiro (Coord.), Ensino Experimental das Ciências: (Re)pensar o Ensino das Ciências (pp. 13-18). Ministério da Educação – Departamento do Ensino Secundário.

- DGE. (2018a). Aprendizagens essenciais - Ciências Naturais. 7.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_7a_ff.pdf.

- DGE. (2018b). Aprendizagens essenciais – Ciências Naturais. 8.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_8a_ff.pdf.

- DGE. (2018c). Aprendizagens essenciais – Ciências Naturais. 9.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_9a_ff.pdf.

- di Fuccia, D., Witteck, T., Markic, S., & Eilks, I. (2012). Trends in practical work in german science education. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 8(1), 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Erduran, S., Masri, Y., Cullinane, A., & Ng, Y. (2020). Assessment of practical science in high stakes examinations: a qualitative analysis of high performing English-speaking countries. International Journal of Science Education, 42(9), 1544-1567. [CrossRef]

- Fadzil, H., & Saat, R. (2019). The development of a resource guıde in assessıng students’ scıence manıpulatıve skılls at secondary schools. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 16(2), 240-252. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S., & Morais, A. (2014). Conceptual demand of practical work in science curricula: a methodological approach. Research in Science Education, 44(1), 53-80. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K.M., & Wickman, P. O. (2013). Student engagement with artefacts and scientific ideas in a laboratory and a concept-mapping activity. International Journal of Science Education, 35(13), 2254-77. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. (2016). Making practical work work: using discussion to enhance pupils’ understanding of physics. Research in Science and Technological Education, 34(3), 290-306. [CrossRef]

- Hartman, A., & Squires, V. (2024). Bridging perspectives: utilizing interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to inform and enhance social interventions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, J., Rannikmäe, M., & Soobard, R. (2020). STEAM Education - A transdisciplinary teaching and learning approach. In B. Akpan & T. Kennedy (Eds.), Science Education in Theory and Practice: An introductory guide to learning theory (pp. 465–477). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Itzek-Greulich, H., & Vollmer, C. (2017). Emotional and motivational outcomes of lab work in the secondary intermediate track: the contribution of a science center outreach lab. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 54(1), 3-28. [CrossRef]

- Karpin, T., Juuti, K., & Lavonen, J. (2014). Learning to apply models of materials while explaining their properties. Research in Science and Technological Education, 32(3), 340-51. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D. (2013). The role of investigations in promoting inquiry-based science education in Ireland. Science Education International, 24(3), 282-305. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1022335.

- Kaufmann, J. (2004). L’entretién compréhensif. (4éme ed.). Armand Colin.

- Köksal, E. (2018). Self-efficacy beliefs of pre-service science teachers on fieldtrips. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 6(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Leite, L. (2001). Contributos para uma utilização mais fundamentada do trabalho laboratorial no ensino das ciências. In H.V. Caetano, & M.G. Santos (Orgs.), Cadernos Didáticos de Ciências 1 (pp. 79-97). Ministério da Educação – Departamento do Ensino Secundário.

- Lowe, D., Newcombe, P., & Stumpers, B. (2013). Evaluation of the use of remote laboratories for secondary school science education. Research in Science Education, 43(3), 1197-1219. [CrossRef]

- Malathi, S., & Rohini, R. (2017). Problems faced by the physical science teachers in doing practical work in higher secondary schools at Aranthangi educational district. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 6(1), 133-35. [CrossRef]

- Martins, G., et al. (2017). Perfil dos alunos à saída da escolaridade obrigatória. Direção-Geral da Educação, Ministério da Educação. https://dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Projeto_Autonomia_e_Flexibilidade/perfil_dos_alunos.pdf.

- Mamlok-Naaman, R., & Barnea, N. (2012). Laboratory activities in Israel. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Mkimbili, S. T., & Ødegaard, M. (2019). Student motivation in science subjects in Tanzania, including students’ voices. Research in Science Education, 49(6), 1835–1859. [CrossRef]

- Musasia, A., Abacha, O., & Biyoyo, M. (2012). Effect of practical work in physics on girls’ performance, attitude change and skills acquisition in the form two-form three secondary schools’. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(23), 151-166. http://ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_23_December_2012/18.pdf.

- Musasia, A., Ocholla, A., & Sakwa, T. (2016). Physics practical work and its influence on students’ academic achievement. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(28), 129-34. http://www.iiste.org.

- Oguoma, E., Jita, L., & Jita, T. (2019). Teachers’ concerns with the implementation of practical work in the physical sciences curriculum and assessment policy Statement in South Africa. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 23(1), 27-39. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H., & Bonito, J. (2023). Practical work in science education: a systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1151641. [CrossRef]

- Oyoo, S. (2012). Language in science classrooms: an analysis of physics teachers’ use of and beliefs about language. Research in Science Education, 42(5), 849-73. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., ... Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Phaeton, M., & Stears, M. (2017). Exploring the alignment of the intended and implemented curriculum through teachers’ interpretation: a case study of A-level biology practical work. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(3), 723-40. [CrossRef]

- Pols, C., Dekkers, P., & de Vries, M., (2021). What do they know? Investigating students’ ability to analyse experimental data in secondary physics education. International Journal of Science Education, 43(2), 274-97. [CrossRef]

- Portugal (2018a). Decreto-Lei no. 54/2018, 6 de julho. Establishes the framework for inclusive education. Diário da República, Lisboa, 6 jul. 2018. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/EEspecial/dl_54_2018.pdf.

- Portugal (2018b). Portaria n.º 223-A/2018, de 3 de agosto. Regulates the educational and training offerings in basic education. Diário da República, 1.ª série, n.º 149, 3 ago. 2018. https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/115886163/details/maximized.

- Portugal (2018c). Decreto-Lei n.o 55/2018, Diário da República n.o 129/2018, Série I de 06/07/2018 2928 (2018). https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/115652962.

- Preethlall, P. (2015). The relathionship between life sciences teacher’s knowledge and beliefs about science education and the teaching and learning of investigative practical work. [Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal]. http://hdl.handle.net/10413/14035.

- Ramnarain, U., & de Beer, J. (2013). Science students creating hybrid spaces when engaging in an expo investigation project. Research in Science Education, 43(1), 99-116. [CrossRef]

- Ruparanganda, F., Rwodzi, M., & Mukundu, C. (2013). Project approach as an alternative to regular laboratory practical work in the teaching and learning of biology in rural secondary schools in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Education and Information Studies, 3(1), 13-20. http://www.ripublication.com/ijeis.htm.

- Shana, Z., & Abulibdeh, E. S. (2020). Science practical work and its impact on students’ science achievement. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 10(2), 199–215. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R., & Abrahams, I. (2020). Secondary school students’ attitudes to practical work in biology, chemistry and physics in England. Research in Science and Technological Education, 38(1), 84-104. [CrossRef]

- Sani, B. (2014). Exploring Teachers’ Approaches to Science Practical Work in Lower Secondary Schools in Malaysia [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/8717.

- Šorgo, A., & Špernjak, A. (2012). Practical work in biology, chemistry and physics at lower secondary and general upper secondary schools in Slovenia. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Sund, P. (2016). Science teachers’ mission impossible?: a qualitative study of obstacles in assessing students’ practical abilities. International Journal of Science Education, 38(14), 2220–2238. [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, G., Lykknes, A., & Kvittingen, L. (2014). Small-scale chemistry for a hands-on approach to chemistry practical work in secondary schools: Experiences from Ethiopia. African Journal of Chemical Education, 4(3), 48–94. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Small-scale-chemistry-for-a-hands-on-approach-to-in-Tesfamariam-Lykknes/e76e4ee6a17e14c0d439fdeca13a4a4f586cdf8c.

- Toplis, R. (2012). Students’ views about secondary school science lessons: the role of practical work. Research in Science Education, 42(3), 531-49. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (2012). International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. https://www.uis.unesco.org/en/methods-and-tools/isced.

- Viswarajan, S. (2017). GCSE practical work in English secondary schools. Research in Teacher Education, 7(2), 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B., Chen, S., & Chen, B. (2019). An investigation of sources of science teachers’ practical knowledge of teaching with practical work. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(4), 723-38. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. (2018). The development, implementation, and evaluation of Labdog – a novel web-based laboratory response system for practical work in science education. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton] University of Southampton Institutional Repository. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/418168/.

- Wei, B., & Li, X. (2017). Exploring science teachers’ perceptions of experimentation: Implications for restructuring school practical work. International Journal of Science Education, 39(13), 1775-1794.

- Wei, B., & Liu, H. (2018). An experienced chemistry teacher’s practical knowledge of teaching with practical work: the PCK perspective. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 19(2), 452-62.

- Xu, L., & Clarke, D. (2012). Student difficulties in learning density: a distributed cognition perspective. Research in Science Education, 42(4), 769-89. [CrossRef]

| SLR Objectives | To obtain an overview of how PW is currently conceptualised and implemented in pre-university science education, according to students, teachers, and researchers. |

| Research question | What is the state of the art regarding PW in science education at the pre-university level? |

| Keywords | Practical work; science education; secondary schools |

| Inclusion criteria | Full-text open access documents; peer-reviewed studies; research focused on or examining how science is taught in pre-university educational institutions; documents written in English. |

| Exclusion criteria | Systematic literature reviews; undergraduate theses or final reports; master's dissertations; documents published prior to 2011. |

| Databases | Query options | Query criteria | Document count |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-on |

Limitators - Latest 10 years - Peer reviewed - Available from library - Full text available Expanders - Search whole article body - Search for equivalent topics |

“Practical work in science education” AND “secondary schools” | 30 |

| ERIC | - Latest 10 years - Peer reviewed |

“Practical work” AND “science education” AND “secondary schools” | 58 |

| Google Scholar | - Latest 10 years | Allintitle: “practical work” “science education” OR “secondary schools” | 43 |

| Scopus | - Latest 10 years | “Practical work” AND “science education” AND “secondary schools” | 19 |

| Web of Science | - Latest 10 years | “Practical work” AND “science education” AND “secondary schools” | 13 |

| Total | 163 |

| DIMENSIONS | SUBDIMENSIONS |

|---|---|

|

1. Conceptual dimension (7 items) |

1.1. Typology of practical work implementation (3 items) |

| 1.2. Mobilisation of skills (minds-on and hands-on approaches) (2 items) | |

| 1.3. Learning Through Everyday Experiences (1 item) | |

| 1.4. Transdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, and interdisciplinarity (1 item) | |

|

2. Limitations dimension (8 items) |

2.1. Limitations related to the suitability of spaces and organisational aspects (1 item) |

| 2.2. Teachers’ concerns and issues related to professional content knowledge (5 items) | |

| 2.3. Economic, organisational, and environmental constraints (1 item) | |

| 2.4. Motivational effects (1 item) | |

| 3. Advantages dimension Research-based skills development(3 items) | |

|

4. Evaluative dimension (9 items) |

4.1. Assessment tools and feedback (3 items) |

| 4.2. Assessment within a specific framework (4 items) | |

| 4.3. Theoretical and/or practical tests, worksheets, and assignments (1 item) | |

| 4.4. Assessment through instrument application and/or involvement of a specific agent (1 item) | |

|

5. Operationalisation dimension (5 items) |

5.1. Integration of digital technologies in practical work (2 items) |

| 5.2. Student performance (1 item) | |

| 5.3. Strategic options (2 items) | |

|

6. Textbook dimension General characteristics of the textbook (2 items) | |

|

7. Curricular dimension (4 items) |

7.1. Correlation between curriculum guidelines and the frequency of implementing practical tasks (1 item) |

| 7.2. Transition from Curriculum Goals to the Essential Learnings (3 items) | |

| Experts | Portuguese Public Universities | Number of Optimisation Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | University of Porto | 4 |

| P2 | University of Lisbon | 2 |

| P3 | University of Aveiro | 23 |

| P4 | University of Aveiro | 17 |

| P5 | University of Minho | 21 |

| DIMENSIONS | SUBDIMENSIONS |

|---|---|

|

1. Conceptual dimension (5 items) |

1.1. Typology of practical work implementation (3 items) |

| 1.2. Mobilisation of skills (minds-on and hands-on approaches) (1 item) | |

| 1.3. Learning Through Real-life Experiences (1 item) | |

|

2. Limitations dimension (6 items) |

2.1. Limitations to the implementation of practical work (4 items) |

| 2.2. Motivational effects (2 itens) | |

| 3. Advantages dimension: Research-based skills development(6 items) | |

|

4. Evaluative dimension (6 items) |

4.1. Assessment within a specific framework (3 items) |

| 4.2. Instruments and feedback (3 items) | |

|

5. Operationalisation dimension (9 items) |

5.1. Integration of digital technologies in practical work (3 itens) |

| 5.2. Student performance (4 items) | |

| 5.3. Strategic options (2 items) | |

| 6. Textbook dimension: General characteristics of the textbook(4 items) | |

|

7. Curricular dimension (8 items) |

7.1. Connection between curriculum guidelines and the frequency of implementing practical tasks (2 items) |

| 7.2. Transition from Curriculum Goals to the Essential Learnings (6 items) | |

| First version | Final Version | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Subdimensions | Items | Subdimensions | Items |

| Conceptual | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Limitations | 4 | 8 | 2 | 6 |

| Advantages | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Evaluative | 4 | 9 | 2 | 6 |

| Operationalization | 3 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| Textbook | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Curricular | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Total | 19 | 38 | 14 | 44 |

| D | Subdimension | Objectives | Questions | Criteria | Indicators | Authors/Regulations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Typology of Practical Work Implementation | - Characterise the concept of practical work (PW). - Characterise the types of skills promoted by the PW. - Unveil how PW enables the development of knowledge-based skills. |

1 - What do you understand by PW? 2 - What typologies of PW do you identify? Which do you most frequently apply in your teaching practice, and why? Please illustrate with a concrete example. 3 – In your opinion, do students acquire knowledge-based skills during the execution of PW? In what ways do they acquire these types of skills? |

- Definition. - Examples. - Typologies. - Knowledge-based skills (critical thinking, memorisation, concentration ability, self-motivation, understanding, and conceptual mastery). - Practical skills (handling materials and instruments, performing technical operations following appropriate methodology, developing fine motor skills, and transforming or creating products adapted to different contexts). |

- Time management. - Evidence of the relationship between the scope of Essential Learnings (EL) and the selected PW typology. - Implementation of field work - Implementation of experimental work - Implementation of laboratory work - PW involves the mobilisation of scientific knowledge in order to enable the understanding of the processes behind certain phenomena, aligned with a 'minds-on' approach that fosters critical thinking. - PW involves the mobilisation of scientific knowledge to enable the understanding of the processes behind certain phenomena, in line with a “minds-on” approach that promotes critical thinking. •Evidence of the development of knowledge-based competencies within the areas defined by the Student Profile at the End of Compulsory Schooling (SPECS): •Languages and texts •Information and communication. •Reasoning and problem-solving. •Critical and creative thinking. •Interpersonal relationships •Personal development and autonomy •Well-being, health, and environment •Aesthetic and artistic sensitivity •Scientific, technical, and technological knowledge •Body awareness and control |

(Martins et al., 2017) (DGE, 2018a) (DGE, 2018b) (DGE, 2018c) (Costa et al., 2022) (Dourado, 2001) (Leite, 2001) (Ferreira & Morais, 2014) (Erduran et al., 2020) (Fadzil & Saat, 2019) (Harrison, 2016) (Itzek-Greulich & Vollmer, 2017) (Karpin et al., 2014) (Oyoo, 2012) (Pols et al., 2021) (Ramnarain & de Beer, 2013) (Xu & Clarke, 2012) (Adamu & Achufusi-Aka, 2020) (Preethlall, 2015) (di Fuccia et al., 2012) (Malathi & Rohini, 2017) (Wilson, 2018) (A. M. Musasia et al., 2012) (Ruparanganda et al., 2013) (Viswarajan, 2017) (Mamlok-Naaman & Barnea, 2012) (Šorgo & Špernjak, 2012) |

| Mobilization of skills (minds-on and hands-on approaches) |

- To describe how students and the teacher engage in the development of inquiry-based PW. |

4 - Let us focus on inquiry-based learning, in which students lead their own investigative process and may even define the problem to be explored. Do you usually implement this type of practical work? Could you provide an example? |

- Identification/characterisation of inquiry-based PW. - Identifying how students develop inquiry-oriented questions. |

- Mobilising practical skills in material manipulation within investigative scientific processes. - Mobilising conceptual skills within investigative scientific processes. - PW involves strong engagement in the process of developing research questions and designing experimental procedures, aligned with the principles of Inquiry-Based Learning. |

(Oguoma et al., 2019) (Toplis, 2012) (Abrahams et al., 2014) (Abrahams et al., 2013) (Akuma & Callaghan, 2019) (Erduran et al., 2020) (Fadzil & Saat, 2019) (Hamza & Wickman, 2013) (Harrison, 2016) (Itzek-Greulich & Vollmer, 2017) (Köksal, 2018) (Karpin et al., 2014) (Kennedy, 2013) (Abrahams & Reiss, 2012) (Phaeton & Stears, 2017) (Ramnarain & de Beer, 2013) (Sharpe & Abrahams, 2020) (Wei et al., 2019) (Wei & Li, 2017) (Wei & Liu, 2018) (Adamu & Achufusi-Aka, 2020) (Preethlall, 2015) (Anza et al., 2016) (Danmole, 2012) (di Fuccia et al., 2012) (Malathi & Rohini, 2017) (Wilson, 2018) (A. M. Musasia et al., 2012) (Ruparanganda et al., 2013) (Viswarajan, 2017) (Lowe et al., 2013) (Mamlok-Naaman & Barnea, 2012) (Šorgo & Špernjak, 2012) |

|

| Learning Through Real-life Experiences | - Identifying the ways in which PW can support the resolution of real-life problems. |

5 – In your opinion, does the PW developed help identify ways to solve everyday problems? Please provide an example. |

- Evidence of the implementation of practical activities where PW contributes meaningfully to the resolution of real-life problems. | - Learning through everyday phenomena as a driver of student motivation and engagement, emerging from meaningful learning episodes drawn from selected experiences and contexts. | (A. Musasia et al., 2016) (Ramnarain & de Beer, 2013) (Wei & Li, 2017) (Xu & Clarke, 2012) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.