Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. The Central Thesis: From Quantum Paradox to Cognitive Principle

2. Interference as a Cognitive State

- States Permitting Interference: Sleep, imagination, and insight are characterized by a heightened tolerance for interference. During sleep, sensory gating reduces “which-path” information, allowing for the hyper-associative recombination of memory traces (Lewis, Knoblich, & Poe, 2018; Tononi & Cirelli, 2014). Imagination and mind-wandering, supported by the default mode network, involve holding present reality and counterfactual possibilities in mind simultaneously (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Raichle, 2015). Insight involves a relaxation of top-down constraints, allowing interference between remote concepts before a sudden, new solution localizes (Jung-Beeman et al., 2004).

- States Suppressing Interference: Effective waking action demands the suppression of interference. Goal-directed wakefulness requires localization onto a single model of the world for sensorimotor control (Milner & Goodale, 2008; Cisek & Kalaska, 2010). Focused attention acts as a cognitive “which-path” detector, selectively amplifying sensory evidence for one hypothesis and forcing rapid localization (Feldman & Friston, 2010; Meng & Tong, 2004). Neuromodulators like norepinephrine sharpen this competition (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005).

| Cognitive Phenomenon (Ze Framework) | Quantum Analogue (Double-Slit) | Primary Neural/Physiological Correlate |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Interference (Ambiguity, contemplation, dreaming) | Wave-like behavior (Superposition through both slits, interference pattern) | Co-activation of competing neural assemblies; Default Mode Network activity; High entropy states. |

| “Which-Path” Information (Sensory fixation, action commitment, social feedback) | Path measurement (Detector at slit, recording which path is taken) | Increased precision-weighting of prediction errors; Norepinephrine-mediated gain; Gamma-band synchronization for binding. |

| Cognitive Localization (Perceptual decision, categorical choice, narrative stabilization) | Particle-like behavior (Collapse to a single localized point on detector) | Winner-take-all inhibitory competition; Synchronization of winning neural coalition; Suppression of rival representations. |

| Sleep as Cognitive Eraser (Synaptic downscaling, memory recombination) | Quantum eraser experiment (Retroactive erasure of path information restores interference) | Thalamic sensory gating; Reduced noradrenergic tone; Slow-wave oscillations (SWS); Theta-gamma coupling in REM. |

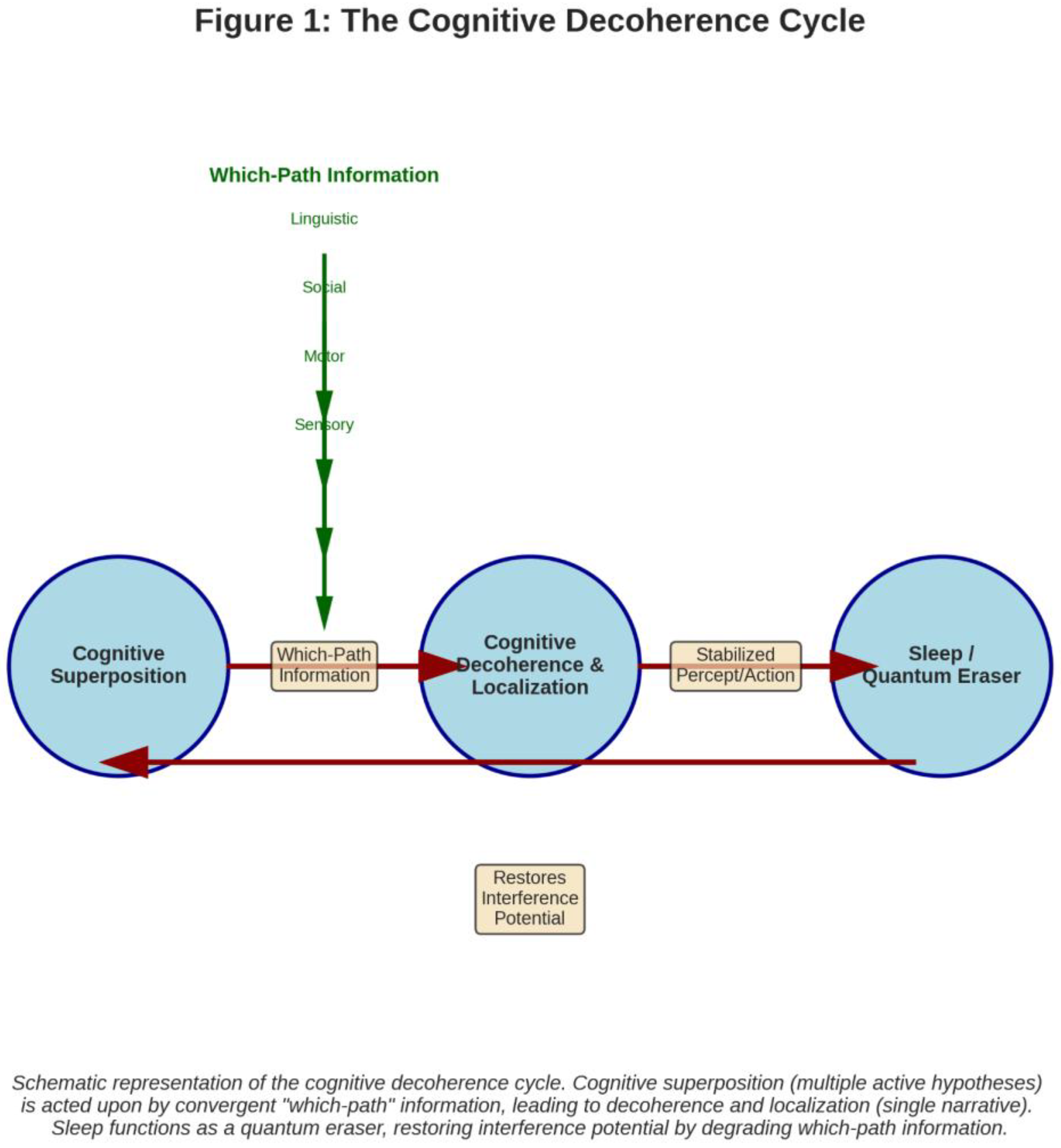

3. “Which-Path” Information and Cognitive Decoherence

- Sensory Fixation & Binding: Focused perception provides high-precision data, anchoring interpretation. Gamma-band synchronization may mediate this binding (Engel & Singer, 2001).

- Linguistic Labeling: Attaching a verbal label commits the system to a categorical schema, suppressing alternatives (Herz & von Clef, 2001).

- Social Feedback: Confirmation or disagreement from others provides direct Bayesian evidence, often overriding personal interpretations (Zaki, Schirmer, & Mitchell, 2011).

- Goal-Directed Action: A motor commitment is the ultimate which-path measurement. The proprioceptive feedback uniquely validates the associated generative model (Cisek & Kalaska, 2010; Friston et al., 2016).

4. Sleep as a Cognitive Quantum Eraser

- Sensory Disconnection: Thalamic gating attenuates external evidence (McCormick & Bal, 1997).

- Neuromodulatory Reversal: Norepinephrine and serotonin drop during SWS, lowering precision-weighting. Cholinergic dominance in REM promotes hyper-association (Pace-Schott & Hobson, 2002; Hobson & Friston, 2012).

- Slow-Wave Oscillations (SWS): Orchestrate the reactivation and recombination of memory traces, not simple replay (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Lewis & Durrant, 2011).

- REM Sleep (Theta-Gamma Coupling): Creates an ideal environment for associative linking of memories, emotions, and concepts (Walker & van der Helm, 2009).

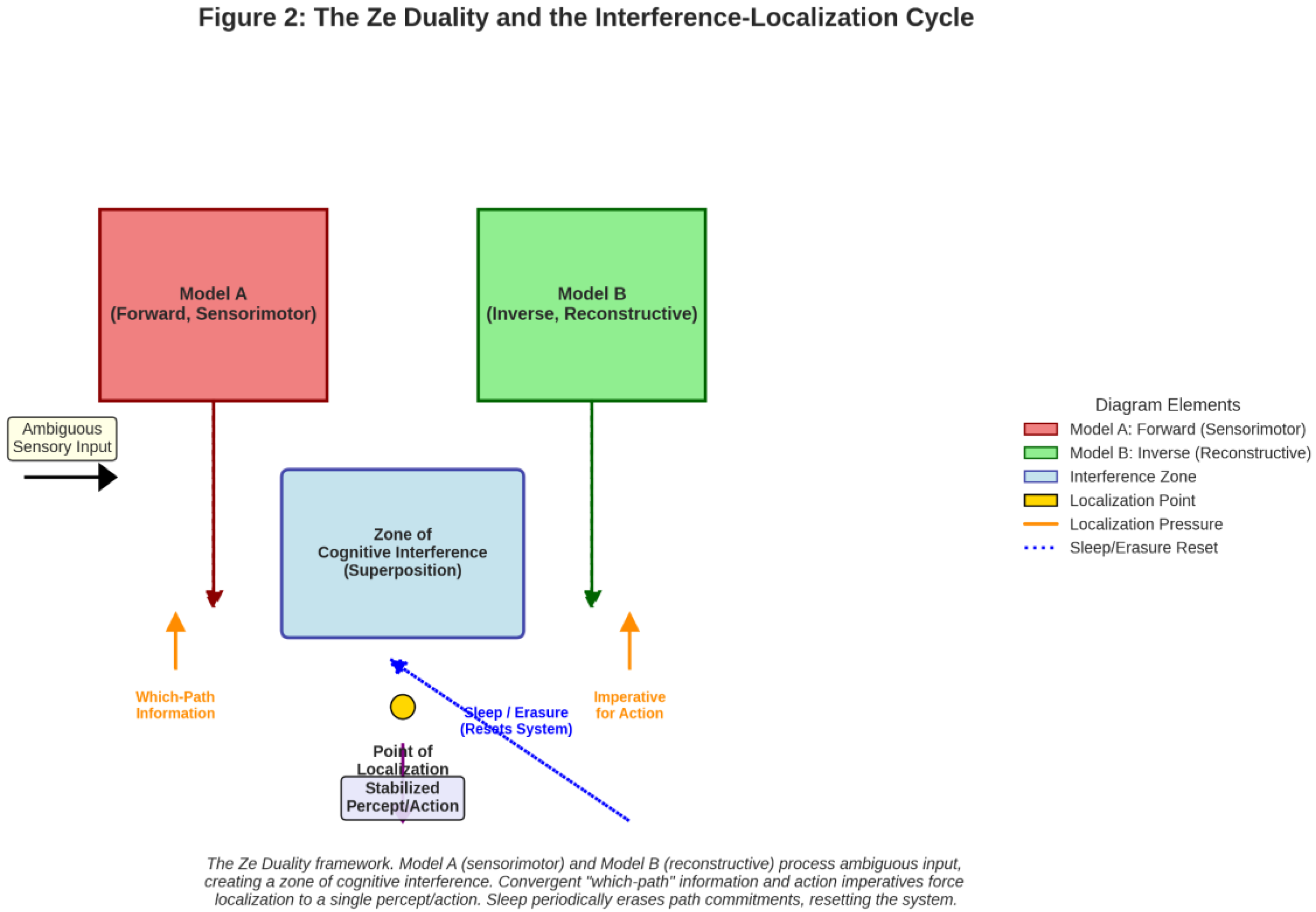

5. Two Generative Models: The Ze Duality

- Model A (Forward, Sensorimotor): Pragmatic, causal, and prospective. It predicts sensory consequences of actions to minimize surprise through movement (Friston et al., 2016). Associated with dorsal visual streams, frontoparietal networks, and the cerebellum (Milner & Goodale, 2008; Wolpert, Miall, & Kawato, 1998). It demands localization for action and dominates during focused tasks (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005).

- Model B (Inverse, Reconstructive): Reflective, diagnostic, and often retrospective. It infers the causes of data to build coherent narratives about the past, others’ minds, and counterfactuals (Hassabis & Maguire, 2009). Associated with the Default Mode Network (DMN), ventral visual stream, and hippocampus (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Raichle, 2015). It tolerates ambiguity and parallel interpretations.

| Characteristic | Model A: Forward (Sensorimotor) | Model B: Inverse (Reconstructive) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | Predict consequences of action; minimize prediction error through movement. | Infer causes of sensory data; construct explanatory narratives. |

| Temporal Focus | Prospective (“What will happen if I do that?”) | Retrospective/Counterfactual (“What caused this? What if?”) |

| Primary Demand | Localization. Requires a single, unambiguous model for effective action. | Tolerates Interference. Can hold multiple interpretations in parallel. |

| Neuroanatomical Correlates | Dorsal visual stream, frontoparietal action networks, cerebellum, basal ganglia. | Default Mode Network (mPFC, PCC, angular gyrus), ventral visual stream, hippocampus. |

| Dominant States | Focused task engagement, threat response, skilled performance. | Mind-wandering, reminiscence, social reasoning, creative brainstorming. |

| Dysfunctional Extremes | Perseveration/Compulsion: Pathological, rigid action loops (e.g., OCD rituals). | Psychosis/Dissociation: Uncontrolled narrative generation detached from sensory evidence. |

6. Localization as a Forced Process

- The free energy difference (ΔF) between models exceeds a stability threshold, creating an unsustainable gradient (Friston & Kiebel, 2009).

- The environment provides unambiguous sensory support, selectively lowering the free energy of one model (Feldman & Friston, 2010).

- The imperative for action generates proprioceptive predictions that can only be fulfilled by one model, forcing a collapse to avoid catastrophic prediction error (Cisek & Kalaska, 2010; Friston et al., 2016).

7. Structural Isomorphism: Molecules and the Brain

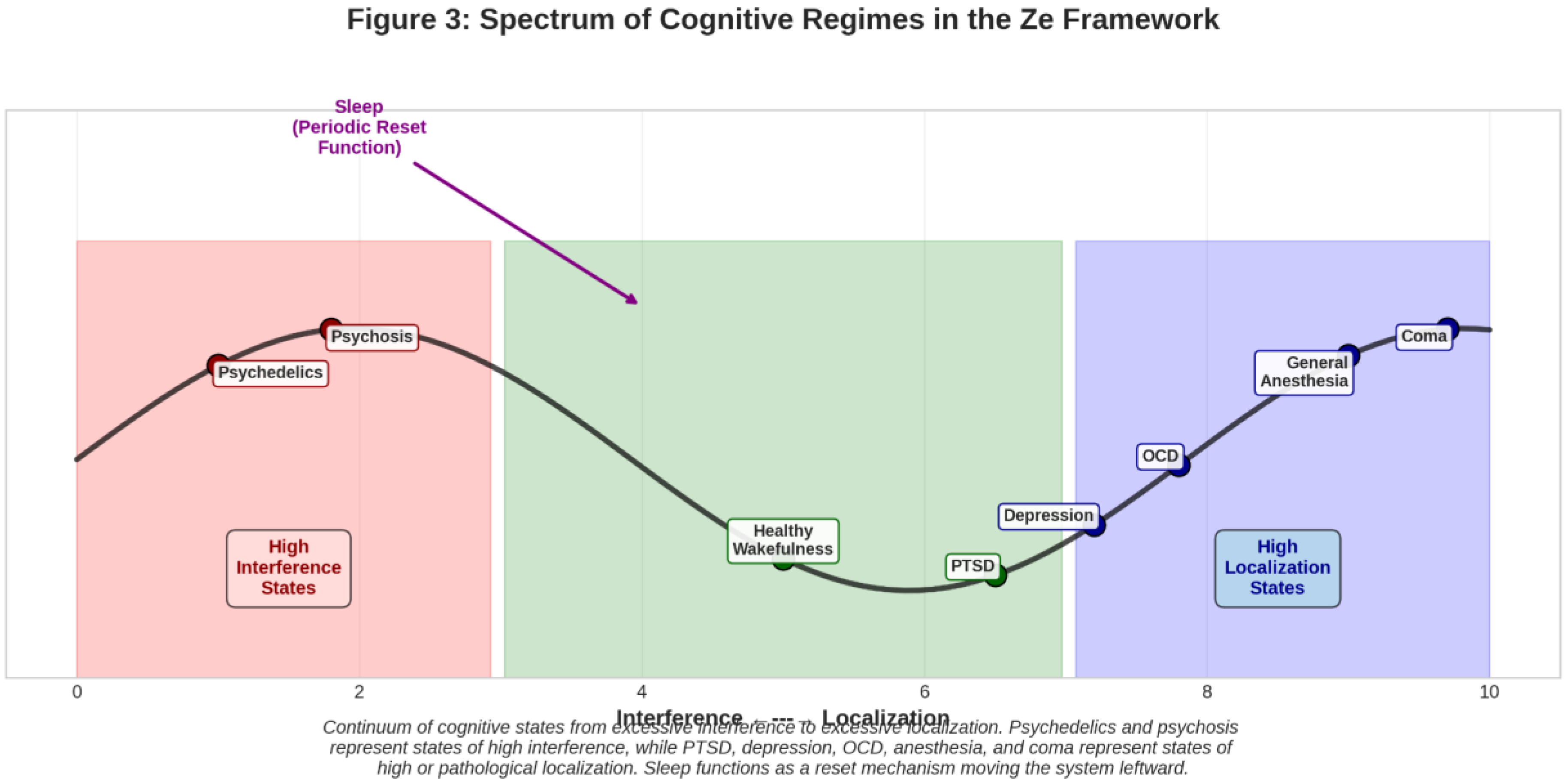

8. Psychopathology: Dysregulation of the Which-Path/Eraser Cycle

-

Excessive Interference (Failed Which-Path Generation):

- ○

- Psychosis: Abnormally weak precision on sensory evidence (failing which-path information) allows Model B’s narratives to operate in uncontrolled interference, leading to hallucinations and delusions (Sterzer et al., 2018; Corlett et al., 2019; Fletcher & Frith, 2009).

- ○

- Dissociation: A failure to integrate which-path information into a coherent self-model, leading to fragmented consciousness (Lanius, Vermetten, & Pain, 2010).

-

Excessive Localization (Failed Erasure):

- ○

- PTSD: A traumatic memory forms an ultra-strong which-path record. Failed sleep-dependent erasure/integration leaves it hyper-localized and intrusive (Brewin, 2015; Tononi & Cirelli, 2014).

- ○

- Depression: Hyper-localization onto a negative narrative (Model B), compounded by poor sleep (reduced erasure), creates cognitive rigidity (Roiser, Elliott, & Sahakian, 2012; Riemann, Krone, Wulff, & Nissen, 2020).

- ○

- OCD: An intrusive thought (interference) is met with a compulsive action—a maladaptive, self-generated which-path measurement to force temporary, fragile localization (Robbins, Vaghi, & Banca, 2019).

9. Altered States of Consciousness as Ze Regimes

- Coma: A global suppression of both models, halting active inference. The apparatus is powered down (Laureys, 2005; Alkire, Hudetz, & Tononi, 2008).

- General Anesthesia: Induces a widespread, artificial localization without interpretation. It disrupts network integration, creating a uniform, low-complexity state that precludes coherent interference (Brown, Lydic, & Schiff, 2010; Pal et al., 2020).

- Psychedelics (e.g., psilocybin, LSD): Attenuate which-path information (reducing precision of high-level priors), thereby amplifying interference. This is evidenced by DMN disintegration, increased entropy, and global connectivity (Carhart-Harris et al., 2012, 2014; Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019).

10. Against Copenhagen: Locality Without an Observer

11. Conclusions: The Brain as an Interferometric Inference Engine

- Interference is the norm: The default is a superposition of hypotheses.

- Localization is a forced event: Driven by free energy gradients, environmental evidence, and action imperative.

- Sleep is the essential eraser: Periodically resetting path commitments to restore flexibility.

References

- Alkire, M. T.; Hudetz, A. G.; Tononi, G. Consciousness and anesthesia. Science 2008, 322(5903), 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, M.; Nairz, O.; Vos-Andreae, J.; Keller, C.; van der Zouw, G.; Zeilinger, A. Wave–particle duality of C60 molecules. Nature 1999, 401(6754), 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2005, 28, 403–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botvinick, M. M.; Cohen, J. D.; Carter, C. S. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2004, 8(12), 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C. R. Re-experiencing traumatic events in PTSD: new avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2015, 6(1), 27180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E. N.; Lydic, R.; Schiff, N. D. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363(27), 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruza, P. D.; Wang, Z.; Busemeyer, J. R. Quantum cognition: a new theoretical approach to psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2015, 19(7), 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, R. L.; Carroll, D. C. Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2007, 11(2), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Friston, K. J. REBUS and the anarchic brain: toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews 2019, 71(3), 316–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Erritzoe, D.; Williams, T.; Stone, J. M.; Reed, L. J.; Colasanti, A.; Nutt, D. J. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109(6), 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Leech, R.; Hellyer, P. J.; Shanahan, M.; Feilding, A.; Tagliazucchi, E.; Nutt, D. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2014, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisek, P.; Kalaska, J. F. Neural mechanisms for interacting with a world full of action choices. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2010, 33, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2013, 36(3), 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, P. R.; Horga, G.; Fletcher, P. C.; Alderson-Day, B.; Schmack, K.; Powers, A. R. Hallucinations and strong priors. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019, 23(2), 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehaene, S.; Naccache, L. Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition 2001, 79(1–2), 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Changeux, J. P.; Naccache, L.; Sackur, J.; Sergent, C. Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: a testable taxonomy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2006, 10(5), 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekelmann, S.; Born, J. The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11(2), 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A. K.; Singer, W. Temporal binding and the neural correlates of sensory awareness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2001, 5(1), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, H.; Friston, K. J. Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2010, 4, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, P. C.; Frith, C. D. Perceiving is believing: a Bayesian approach to explaining the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2009, 10(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2009, 13(7), 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11(2), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Life as we know it. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2013, 10(86), 20130475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Kiebel, S. Predictive coding under the free-energy principle. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 364(1521), 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K.; Daunizeau, J.; Kilner, J.; Kiebel, S. J. Action and behavior: a free-energy formulation. Biological Cybernetics 2010, 102(3), 227–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; FitzGerald, T.; Rigoli, F.; Schwartenbeck, P.; Pezzulo, G. Active inference: a process theory. Neural Computation 2016, 29(1), 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. J.; Stephan, K. E.; Montague, R.; Dolan, R. J. Computational psychiatry: the brain as a phantastic organ. The Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1(2), 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackermüller, L.; Hornberger, K.; Brezger, B.; Zeilinger, A.; Arndt, M. Decoherence of matter waves by thermal emission of radiation. Nature 2004, 427(6976), 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggard, P. Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2008, 9(12), 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassabis, D.; Maguire, E. A. The construction system of the brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 364(1521), 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisenberg, W. Physics and philosophy: The revolution in modern science; Harper & Row, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R. S.; von Clef, J. The influence of verbal labeling on the perception of odors: Evidence for olfactory illusions? Perception 2001, 30(3), 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, J. A.; Friston, K. J. Waking and dreaming consciousness: Neurobiological and functional considerations. Progress in Neurobiology 2012, 98(1), 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohwy, J. The self-evidencing brain. Noûs 2016, 50(2), 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research 2022, Vol. 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Beeman, M.; Bowden, E. M.; Haberman, J.; Frymiare, J. L.; Arambel-Liu, S.; Greenblatt, R.; Kounios, J. Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. PLoS Biology 2004, 2(4), e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, D. C.; Pouget, A. The Bayesian brain: the role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. Trends in Neurosciences 2004, 27(12), 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanius, R. A.; Vermetten, E.; Pain, C. (Eds.) The impact of early life trauma on health and disease: The hidden epidemic; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laureys, S. The neural correlate of (un)awareness: lessons from the vegetative state. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2005, 9(12), 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. A.; Durrant, S. J. Overlapping memory replay during sleep builds cognitive schemata. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2011, 15(8), 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. A.; Knoblich, G.; Poe, G. How memory replay in sleep boosts creative problem-solving. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2018, 22(6), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libet, B.; Gleason, C. A.; Wright, E. W.; Pearl, D. K. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). Brain 1983, 106(3), 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, D. A.; Bal, T. Sleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanisms. Annual Review of Neuroscience 1997, 20, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Tong, F. Can attention selectively bias bistable perception? Differences between binocular rivalry and ambiguous figures. Journal of Vision 2004, 4(7), 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A. D.; Goodale, M. A. Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46(3), 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, V.; Jaspar, M.; Meyer, C.; Kussé, C.; Chellappa, S. L.; Degueldre, C.; Phillips, C. Local modulation of human brain responses by circadian rhythmicity and sleep debt. Science 2016, 353(6300), 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace-Schott, E. F.; Hobson, J. A. The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2002, 3(8), 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Li, D.; Dean, J. G.; Brito, M. A.; Liu, T.; Fryzel, A. M.; Mashour, G. A. Level of consciousness is dissociable from electroencephalographic measures of cortical connectivity, slow oscillations, and complexity. Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 40(3), 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichle, M. E. The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2015, 38, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, D.; Krone, L. B.; Wulff, K.; Nissen, C. Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45(1), 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, T. W.; Vaghi, M. M.; Banca, P. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Puzzles and Prospects. Neuron 2019, 102(1), 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roiser, J. P.; Elliott, R.; Sahakian, B. J. Cognitive mechanisms of treatment in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37(1), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, C. S.; Brass, M.; Heinze, H. J.; Haynes, J. D. Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience 2008, 11(5), 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzer, P.; Adams, R. A.; Fletcher, P.; Frith, C.; Lawrie, S. M.; Muckli, L.; Corlett, P. R. The predictive coding account of psychosis. Biological Psychiatry 2018, 84(9), 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkemaladze, J. Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells? Molecular Biology Reports 2023, 50(3), 2751–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkemaladze, J. Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol 2024, 14, 1324446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tkemaladze, J. Old Centrioles Make Old Bodies. Annals of Rejuvenation Science 2026, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. Visions of the Future. Longevity Horizon 2026, 2(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).