1. Introduction

Language-conditioned autonomous agents have emerged as a promising paradigm for building flexible and general-purpose AI systems [

1,

2]. By representing goals, observations, and intermediate reasoning steps in natural language, these agents can leverage powerful language models [

3,

4,

5] to perform planning, tool use [

6,

7], and decision making across a wide range of tasks. This approach has enabled rapid progress in areas such as task automation, interactive assistants, and simulated autonomy [

8,

9]. Despite these advances, language-conditioned agents continue to struggle in tasks that require sustained interaction over long horizons. Empirical evidence shows that agents may begin tasks correctly, produce plausible reasoning chains, and yet fail in later stages due to inconsistencies between their internal beliefs and the actual environment [

10]. These failures are often attributed to hallucination [

11,

12,

13], limited context windows [

14,

15,

16], or insufficient reasoning depth [

17,

18].

In this paper, we argue that such explanations are incomplete. We introduce state drift as a distinct failure mode in language-conditioned autonomous agents, referring to the emergence and persistence of misalignment between an agent’s internal textual representation of state and the true environment state. Unlike isolated hallucinations or reasoning errors, state drift may remain undetected by the agent itself while progressively undermining long-horizon task execution. We present a systematic study of state drift in language-driven agents operating in controlled long-horizon tasks. Our results show that state drift emerges even under deterministic conditions and persists across different agent configurations. Importantly, we find that increasing context capacity alone does not reliably prevent state drift, indicating that this failure mode is not simply a consequence of limited memory or forgetting. These findings highlight state consistency as a critical and underexplored challenge in the design of language-conditioned autonomous systems.

1.1. Key Contributions

This work makes the following contributions:

We identify state drift as a distinct failure mode in language-conditioned autonomous agents, characterized by persistent misalignment between an agent’s internal textual state and the true environment state over long horizons.

We provide a formal problem formulation of state drift and introduce a simple, interpretable metric for measuring state misalignment over time.

Through controlled experiments in long-horizon, text-based environments, we empirically demonstrate that state drift can arise even when local reasoning steps remain coherent and logically valid.

We show that increasing context capacity alone does not mitigate state drift in deterministic settings, indicating that this failure mode is not simply a consequence of limited memory or forgetting.

1.2. Scope and Boundaries of This Study

The goal of this work is to identify and characterize state drift as a failure mode in language-conditioned autonomous agents, rather than to propose mitigation strategies. Accordingly, our experiments are conducted in controlled, text-based environments that allow direct access to ground-truth state and precise measurement of internal state misalignment. While this setting is intentionally simplified, it enables isolation of state drift dynamics without confounding factors such as perception noise or stochastic environment transitions.

We focus on deterministic task settings and a limited set of agent configurations to study state drift as a structural phenomenon. Our findings should therefore be interpreted as evidence of the existence and impact of state drift, rather than as an exhaustive evaluation across models, tasks, or domains. Investigating mitigation mechanisms, stochastic environments, and more complex agent architectures is left for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Language-Conditioned Autonomous Agents

Recent advances in large language models [

19,

20,

21] have enabled a new class of autonomous agents that use natural language as an internal medium for reasoning, planning, and decision making [

22]. These language-conditioned agents represent goals, observations, intermediate states, and action plans in textual form, allowing a single model to flexibly operate across diverse tasks. Prior work has demonstrated that such agents can perform multi-step reasoning [

23,

24,

25], tool use, and task decomposition without task-specific training, often by leveraging chain-of-thought reasoning and prompt-based control.

Despite their flexibility, language-conditioned agents remain fragile in long-horizon settings. Empirical studies have shown that while agents often perform well in short tasks, their performance degrades as task length increases [

26,

27]. This degradation has commonly been attributed to limitations in reasoning depth, context window size, or the accumulation of hallucinations. In contrast, our work focuses on a different aspect of agent failure: the ability to maintain an accurate and consistent internal representation of task state over time, independent of local reasoning correctness.

2.2. Memory, Belief, and State Representation in LLM-Based Agents

To address long-horizon challenges, many agent architectures incorporate explicit memory mechanisms [

28], such as external memory buffers, episodic recall systems, summarization modules, or retrieval-augmented generation [

29,

30,

31]. These approaches aim to preserve relevant information beyond the fixed context window of language models and enable agents to reason over extended interaction histories. Techniques including memory compression, hierarchical summarization, selective retrieval, and tool-based state storage have been proposed to manage growing volumes of interaction data.

While such methods improve scalability, they introduce challenges related to information loss and semantic distortion. Summarization and compression are inherently lossy processes, and small inaccuracies introduced during state updates may accumulate over time. Unlike classical agents that maintain structured belief states [

32] or probabilistic world models, language-conditioned agents rely on unstructured textual representations that lack explicit guarantees of consistency. Prior work has primarily evaluated memory systems based on task success, retrieval accuracy, or recall fidelity, without explicitly analyzing how an agent’s internal belief state diverges from the true environment state during long-horizon execution. Our work directly examines this divergence and frames it as a distinct failure mode.

2.3. Failure Modes in Autonomous and Interactive Agents

The reliability of autonomous agents has been studied through various lenses, including hallucination, error propagation, and compounding planning mistakes. Hallucination refers to the generation of incorrect or unsupported statements, while error propagation describes how early errors influence later decisions. Other work has analyzed brittleness in planning, tool misuse, and sensitivity to prompt variations [

33].

Although these studies provide valuable insights, they often treat failures as isolated events or focus on observable output errors. In contrast, state drift describes a gradual and often hidden process in which the agent’s internal belief state becomes increasingly misaligned with the environment, even when individual reasoning steps remain locally coherent. This distinction is particularly important for language-conditioned agents, where internal state is represented in natural language and may appear plausible and self-consistent despite being incorrect with respect to the external world.

2.4. Long-Horizon Reasoning, Context Limitations, and Partial Observability

Several lines of work have investigated the limitations of long-horizon reasoning in language models, including analyses of context window constraints, attention dilution, and retrieval noise. Expanding context windows and retrieval-augmented approaches have been proposed as solutions to long-horizon tasks, under the assumption that access to more information improves reasoning fidelity.

However, recent evidence suggests that increasing context alone does not guarantee improved performance and may even degrade reasoning quality in some settings. Our work complements these findings by showing that long-horizon failures can arise even when relevant information is present in the agent’s context. Specifically, we demonstrate that misalignment between internal textual state and environment state can accumulate under partial observability and unobserved environment transitions, independently of context size. This highlights the need for mechanisms that explicitly verify and maintain state consistency, rather than relying solely on increased memory or retrieval.

2.5. Positioning of This Work

Prior research on language-conditioned autonomous agents has largely emphasized reasoning capability, memory capacity, and context management as primary determinants of long-horizon performance. We argue that these factors do not fully explain observed failures in autonomous agents. By introducing and empirically analyzing state drift, we identify a failure mode that is orthogonal to reasoning correctness, memory size, and retrieval fidelity. Our work complements existing studies by shifting the focus from how agents reason to how accurately they maintain and update their internal representations of the world over time.

3. Problem Formulation: State Drift in Language-Conditioned Agents

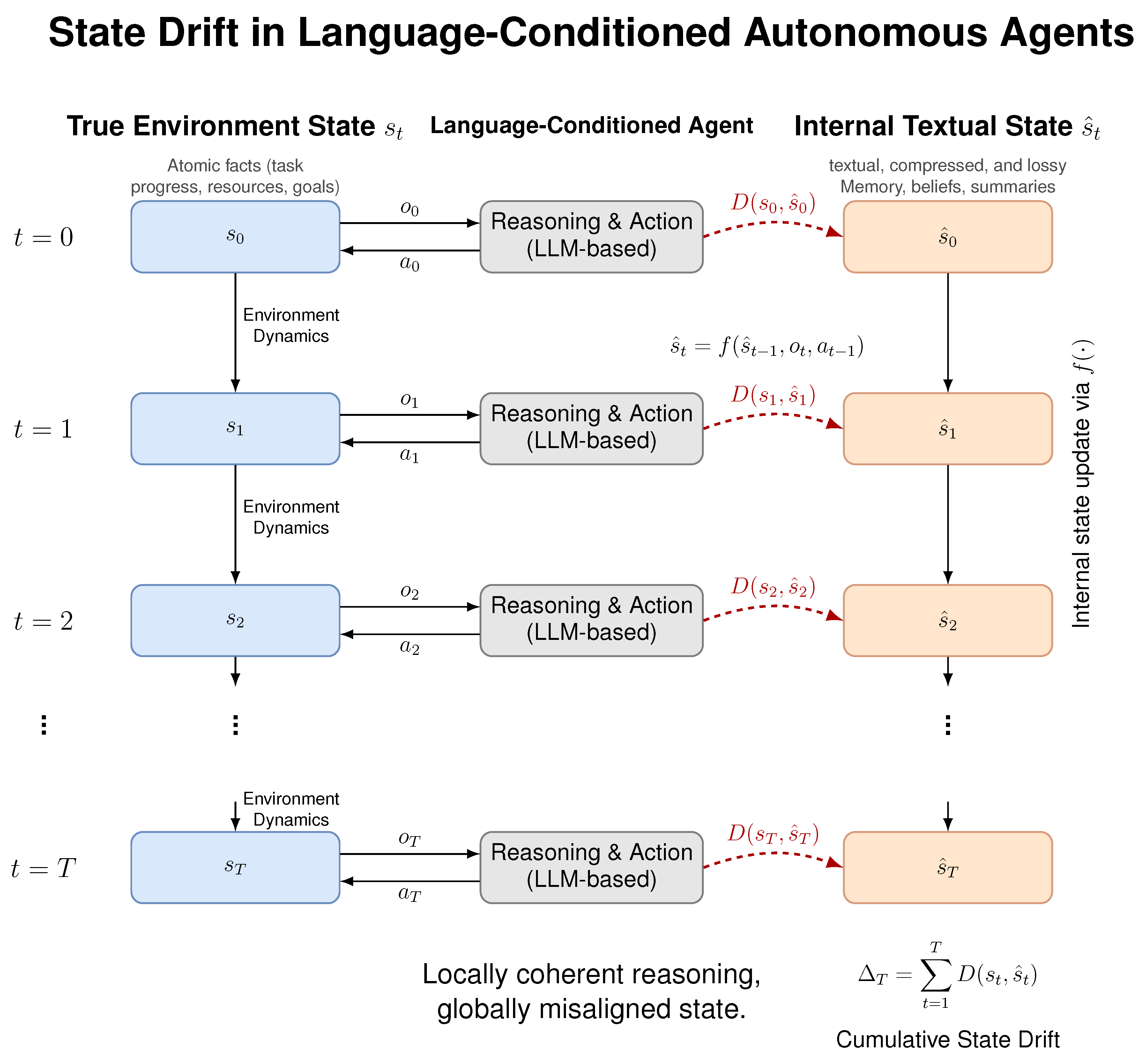

We consider a language-conditioned autonomous agent interacting sequentially with an environment over a finite horizon of T steps. At each time step , the environment occupies a true state , which evolves according to environment dynamics that may be partially observable to the agent. The agent receives an observation , maintains an internal representation of state, and selects an action .

Unlike classical agents that maintain structured belief states, language-conditioned agents represent internal state primarily in natural language. This internal state may include textual summaries of past observations, inferred beliefs about the environment, intermediate goals, and tool outputs. We denote the agent’s internal textual state at time t as , which is intended to approximate relevant aspects of the true environment state .

Figure 1.

The environment maintains a true state (left), while the agent maintains an internal textual state (right) used for reasoning and action selection. Although the agent’s reasoning remains locally coherent at each step, incremental state updates introduce small inconsistencies that accumulate over time. The resulting divergence, quantified by and cumulative drift , leads to long-horizon failure.

Figure 1.

The environment maintains a true state (left), while the agent maintains an internal textual state (right) used for reasoning and action selection. Although the agent’s reasoning remains locally coherent at each step, incremental state updates introduce small inconsistencies that accumulate over time. The resulting divergence, quantified by and cumulative drift , leads to long-horizon failure.

3.1. Agent State Update

At each time step, the agent updates its internal state based on prior internal state, new observations, and previous actions. We abstract this update process as

where

represents the agent’s state update mechanism, typically implemented via a language model conditioned on textual context and memory. Importantly, this update process is lossy:

is a compressed and abstracted representation of

, rather than a complete encoding.

3.2. Language-Conditioned Internal State

In language-conditioned agents, is expressed in natural language rather than a structured symbolic or probabilistic form. As a result, is subject to ambiguity, semantic compression, and imprecision. While such representations enable flexible reasoning and generalization, they also introduce the possibility of misalignment between the agent’s internal beliefs and the true environment state, particularly under partial observability and delayed feedback.

We emphasize that may remain locally coherent and internally consistent from the agent’s perspective, even when it no longer accurately reflects . This distinction is central to the failure mode we study.

3.3. Definition of State Drift

We define

state drift as the emergence and persistence of divergence between the true environment state

and the agent’s internal textual state

over time. To formalize this notion, we introduce a discrepancy function

which measures the degree of misalignment between the environment state and the agent’s internal representation. In practice,

may be instantiated using fact-level mismatches, semantic similarity measures, or task-specific state comparisons.

State drift occurs when exhibits sustained non-zero values or persistent misalignment over time, even when the agent’s local reasoning steps remain logically coherent.

3.4. Cumulative Drift

To capture the long-horizon nature of this phenomenon, we define cumulative state drift as

This quantity reflects the total misalignment accumulated during an episode and provides a scalar summary of long-horizon state inconsistency.

3.5. Distinction from Related Failure Modes

State drift is distinct from several commonly discussed failure modes in language-conditioned agents. Unlike hallucination, which refers to the generation of incorrect statements at a given time step, state drift is a gradual process that may not be immediately observable. Unlike planning or reasoning errors, state drift can occur even when individual reasoning steps are locally valid. Finally, state drift is not solely a consequence of limited context length; increasing context capacity alone does not, in general, prevent its emergence or persistence.

This formulation isolates state drift as a structural limitation of language-conditioned autonomy, motivating empirical investigation into its prevalence and impact on long-horizon agent behaviour.

4. Experimental Setup

The goal of our experiments is to empirically investigate the emergence and impact of state drift in language-conditioned autonomous agents operating over long horizons. We design controlled environments in which the true environment state is observable to the experimenter, allowing direct comparison with the agent’s internal textual state representation.

4.1. Task Environments

We evaluate agents in two text-based, long-horizon task environments designed to induce partial observability, delayed dependencies, and persistent state tracking.

Task 1: Sequential Task Execution.

The first environment requires the agent to complete a sequence of interdependent subtasks in a fixed order (e.g., data collection, preprocessing, and analysis). The environment state includes atomic facts describing task progress and completion status. Certain state changes are not explicitly restated to the agent at every step, requiring the agent to accurately maintain internal beliefs about task state over time.

Task 2: Resource Management Task.

The second environment introduces hidden resource availability constraints. In this setting, the agent must reason about whether required resources remain available in order to complete the task. Crucially, resource availability may change independently of the agent’s actions and is not always directly observable, creating opportunities for persistent belief misalignment.

At each time step t, the environment maintains a ground-truth state composed of a set of atomic facts (e.g., task progress, resource availability, goal status). The agent receives a partial textual observation derived from , performs reasoning based on its internal state, and outputs an action that may modify the environment state. This design enables precise measurement of state drift by comparing the agent’s internal textual representation with the known ground-truth state at each step.

4.2. Language-Conditioned Agent

The agent follows a standard language-conditioned autonomy loop. At each time step, the agent maintains an internal textual state , which summarizes relevant past observations, inferred beliefs, and intermediate goals. This internal state is incrementally updated and used as context for subsequent reasoning and action selection.

Conceptually, the agent architecture consists of:

an instruction-tuned language model responsible for reasoning and decision making,

a textual memory or scratchpad that stores the internal state,

an action selection mechanism that maps language outputs to discrete environment actions.

We treat the language model as a black box and do not rely on model-specific internals. All experiments are conducted using deterministic decoding to isolate state drift effects from sampling variability.

Model Instantiation:

In our experiments, the language-conditioned agent is instantiated using an instruction-tuned large language model. Specifically, we use the google/gemma-2b-it model for all reported results. The model is used in inference-only mode with deterministic decoding, and no task-specific fine-tuning is performed. This setup allows us to isolate state drift dynamics from stochastic generation effects or training artifacts.

4.3. Agent Variants

To isolate the effect of context capacity, we evaluate two agent variants:

- 1.

Baseline Agent: An agent with a fixed-size internal textual state that is incrementally updated at each time step.

- 2.

Extended-Context Agent: An agent with increased context capacity, allowing a larger portion of prior internal state to be retained across time steps.

Both agents use identical reasoning prompts and action selection mechanisms; they differ only in the amount of contextual information retained.

4.4. Measuring State Drift

At each time step, we extract the agent’s internal textual state and compare it to the true environment state . The environment state is represented as a set of atomic facts, while the internal textual state is converted into a comparable fact set using simple rule-based extraction.

We compute the fact-level drift metric

defined in

Section 3, which measures the proportion of environment facts that are missing or incorrect in the agent’s internal representation. This metric allows us to track the evolution of state drift over time and to relate cumulative drift to task outcomes.

4.5. Evaluation Protocol

For each task, agents are run until task completion or failure. We record:

the state drift metric at each time step,

cumulative drift over the episode,

task success or failure,

qualitative logs of intermediate reasoning steps.

All experiments are conducted using fixed prompts and deterministic settings to reduce variability and isolate state drift effects. Each agent configuration is evaluated across both task environments and multiple time steps, enabling controlled analysis of drift dynamics under different long-horizon conditions.

5. Results

We present empirical results demonstrating the emergence and impact of state drift in language-conditioned autonomous agents operating over long horizons. Our analysis focuses on three questions: (1) whether state drift accumulates over time, (2) whether drift occurs independently of local reasoning coherence, and (3) whether increasing context capacity mitigates drift.

5.1. State Drift Accumulates Over Time

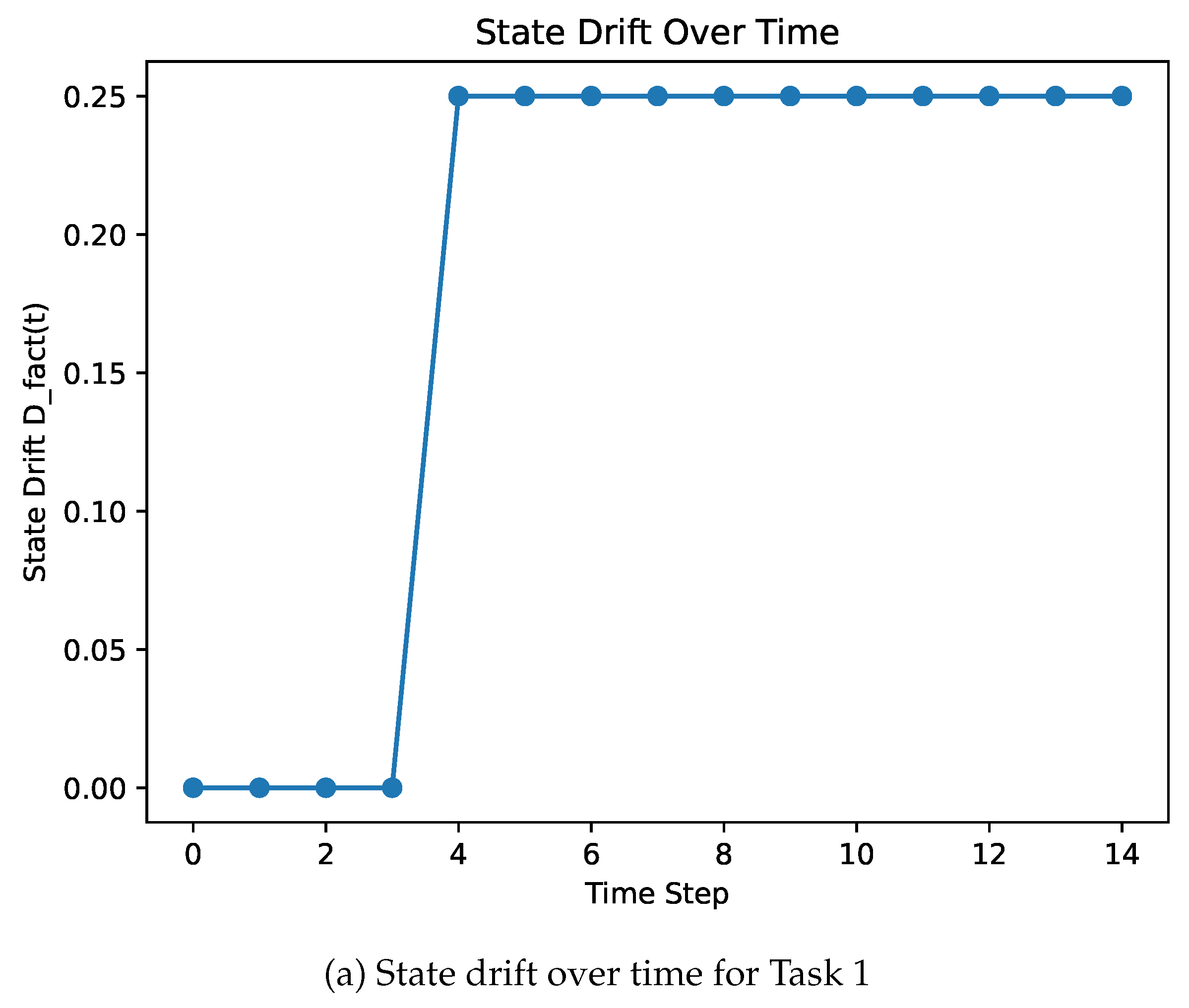

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the fact-level drift metric

as a function of time for representative task instances. Across both tasks, we observe the emergence and persistence of state drift as the episode progresses. In early stages of each task, the agent’s internal textual state closely matches the true environment state. As interactions accumulate, discrepancies emerge and persist, reflecting increasing misalignment between internal belief and environment state.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the fact-level state drift metric over time for representative task instances. In both tasks, state drift emerges early and persists throughout the episode, illustrating the cumulative nature of misalignment between the agent’s internal textual state and the true environment state.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the fact-level state drift metric over time for representative task instances. In both tasks, state drift emerges early and persists throughout the episode, illustrating the cumulative nature of misalignment between the agent’s internal textual state and the true environment state.

Notably, drift increases gradually rather than abruptly, suggesting that failures do not arise from isolated errors but from the accumulation of persistent misalignment over time. In both tasks, task failure is observed only after sustained state drift has developed, highlighting the close relationship between long-horizon reliability and the agent’s ability to maintain an accurate internal representation of environment state.

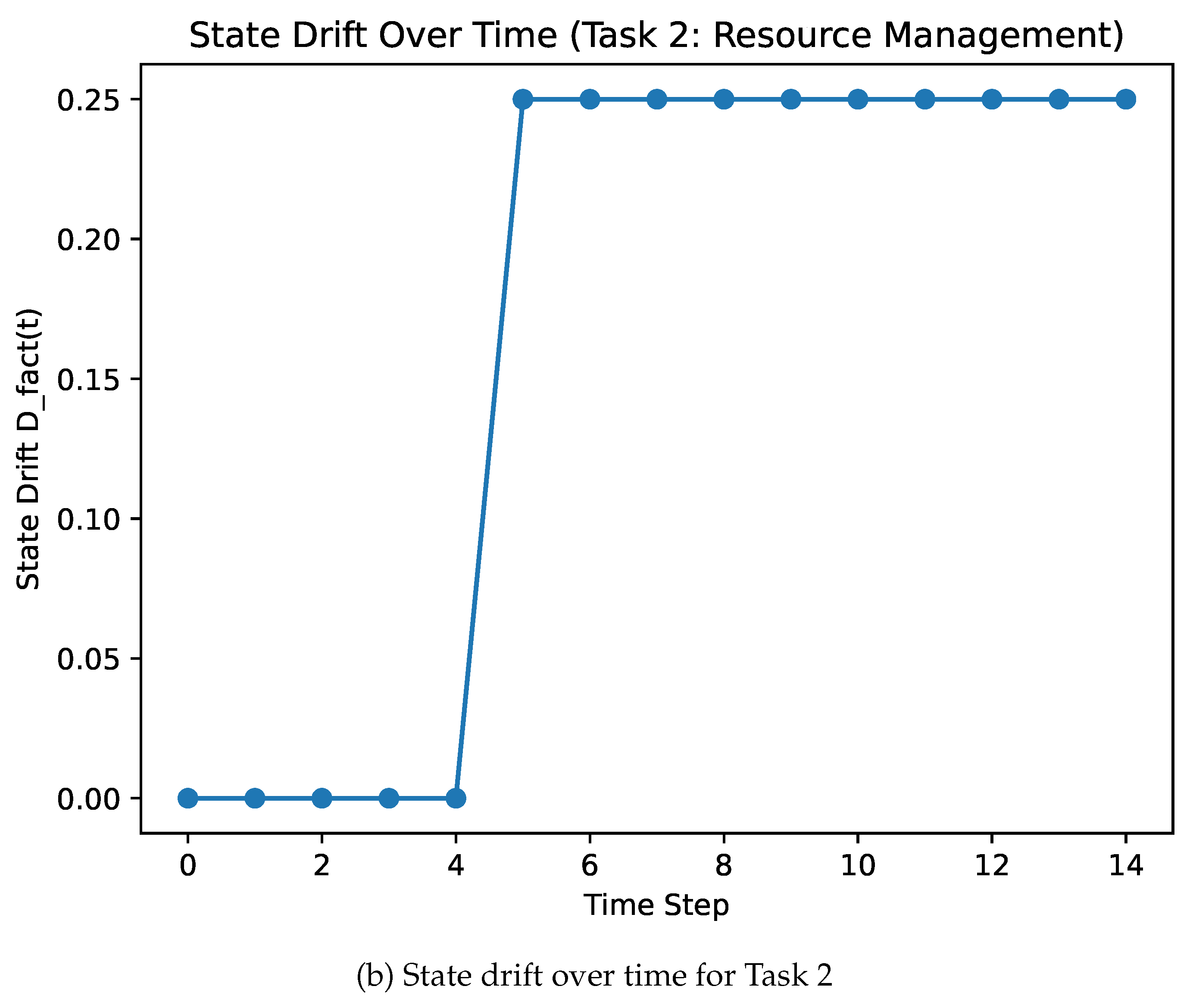

5.2. Reasoning Coherence vs. State Alignment

To distinguish state drift from reasoning failure, we analyze the agent’s intermediate reasoning traces alongside state alignment metrics. Qualitative inspection of reasoning logs reveals that the agent continues to produce logically coherent and contextually appropriate reasoning steps even as state drift develops.

Figure 3 illustrates this decoupling by comparing a proxy measure of reasoning coherence measured via the length of generated reasoning traces—with the state drift metric over time. Across both tasks, reasoning trace length remains relatively stable, while state alignment progressively degrades. This indicates that state drift is not simply a consequence of poor or inconsistent reasoning, but instead reflects a breakdown in the agent’s ability to maintain an accurate internal representation of the environment.

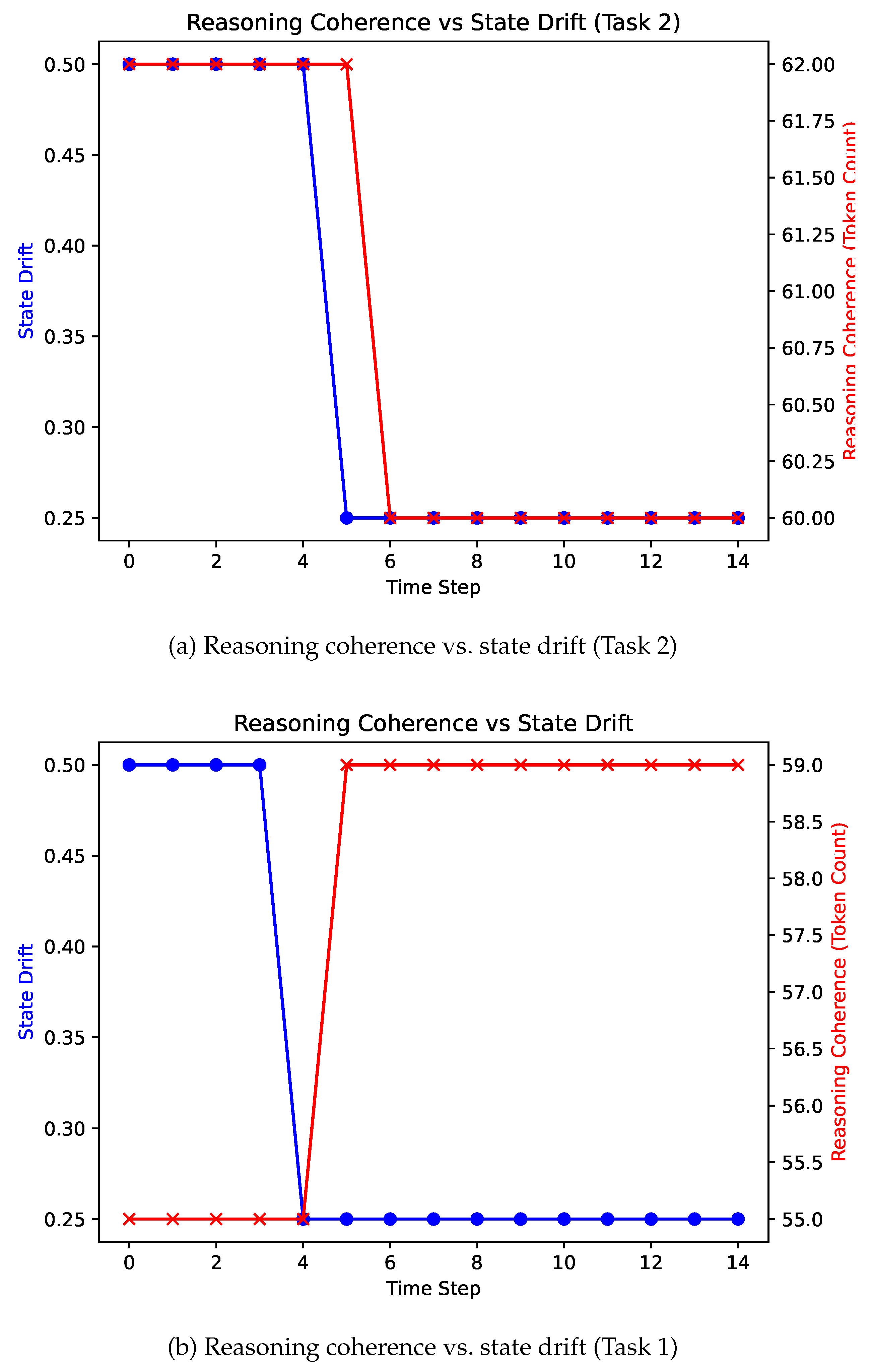

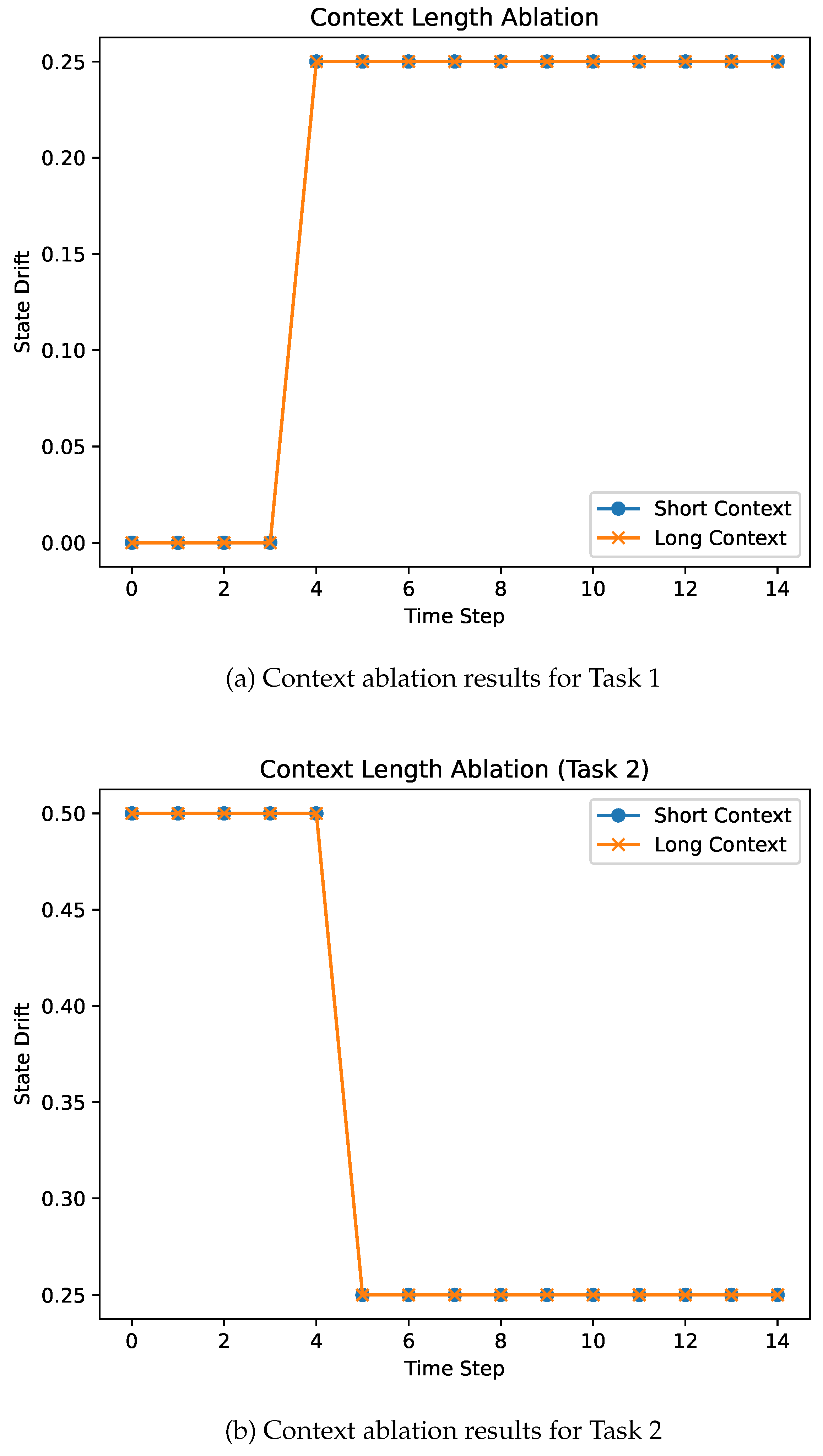

5.3. Effect of Context Capacity

A common hypothesis is that increasing context length or memory capacity should alleviate long-horizon failures by preserving more information over time. To test this assumption, we compare a baseline agent with an extended-context variant that retains a larger internal textual state. As shown in

Figure 4, increasing context capacity does not mitigate state drift in either task. Both agents exhibit near-identical drift trajectories, with drift emerging at the same time and persisting throughout the episode. This indicates that state drift in our setup is not caused by memory truncation or insufficient context, but rather by persistent belief misalignment arising from unobserved environment changes.

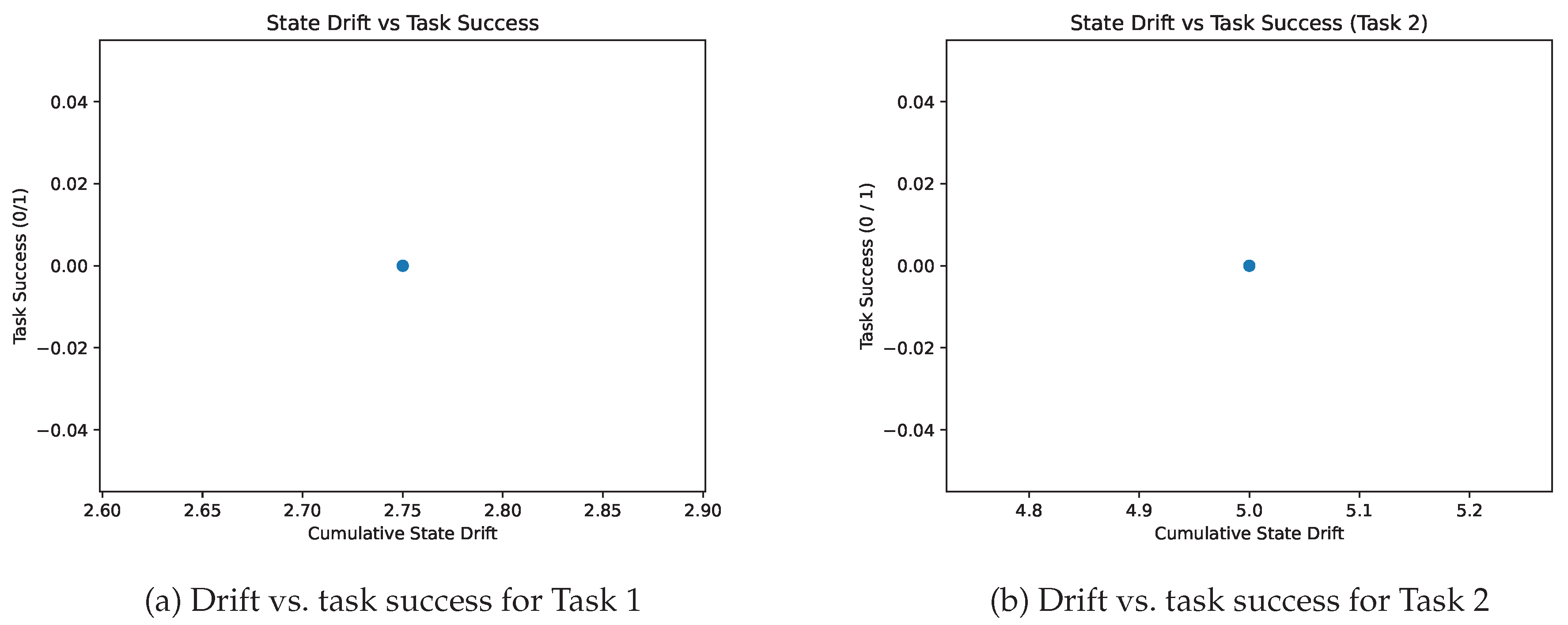

5.4. Relationship Between Drift and Task Success

Finally, we examine the relationship between cumulative state drift and task outcomes.

Figure 5 plots task success against cumulative drift

. In both evaluated tasks, we observe that episodes accumulating persistent state drift consistently fail to complete the task. While task success does not vary within our deterministic experimental setup, this result demonstrates that sustained state drift is sufficient to induce task failure. Importantly, these failures often occur despite locally coherent reasoning and seemingly correct action selection, supporting the interpretation of state drift as a distinct failure mode that undermines long-horizon autonomy independently of reasoning quality.

5.5. Summary of Findings

Across all experiments, we find that (i) state drift emerges and persists over long-horizon interactions, (ii) drift can occur even when local reasoning remains coherent, and (iii) increasing context capacity alone does not eliminate drift. Together, these results provide empirical evidence that state drift is a fundamental challenge for language-conditioned autonomous agents and must be addressed explicitly to enable reliable long-horizon behaviour.

6. Analysis and Discussion

The results in

Section 5 demonstrate that state drift emerges consistently in language-conditioned autonomous agents and is sufficient to induce long-horizon task failure. In this section, we analyze why state drift arises, why it persists despite increased context capacity, and what this implies for the design of reliable autonomous agents.

6.1. Sources of State Drift

Our experiments suggest that state drift is not caused by a single failure event, but rather by the accumulation of small inconsistencies during state updates. In language-conditioned agents, internal state is represented as natural language text, which is inherently ambiguous and lossy. Each update to the internal state involves abstraction, summarization, or reinterpretation of prior information, introducing opportunities for semantic distortion.

Several factors contribute to this process. First, partial observability means that agents must infer unobserved aspects of the environment, and these inferences may become outdated as the environment evolves. Second, delayed feedback prevents immediate correction of incorrect beliefs, allowing misalignment to persist across multiple steps. Third, memory compression and summarization, while necessary for scalability, discard information that may later become relevant. Individually, these effects may be minor, but over long horizons they compound into substantial state drift.

6.2. Why Reasoning Remains Coherent

A key finding of our study is that state drift can occur even when local reasoning steps remain logically coherent. This apparent contradiction arises because reasoning coherence is evaluated relative to the agent’s internal state, not the true environment state. As long as the internal state is self-consistent, the agent can produce plausible and logically valid reasoning chains, even if those chains are grounded in incorrect or incomplete beliefs.

This observation highlights an important limitation of evaluating agent behavior solely based on reasoning traces or language outputs. An agent may appear competent and rational while operating on a progressively distorted representation of the world. State drift therefore represents a failure of grounding rather than a failure of inference, and cannot be reliably detected through reasoning quality alone.

6.3. Limits of Context Scaling

Increasing context length or memory capacity is often proposed as a solution to long-horizon failures in language-conditioned agents. Our results show that increasing context capacity alone does not mitigate state drift in deterministic settings. In both evaluated tasks, agents with extended context exhibit drift trajectories that are indistinguishable from those of baseline agents, with drift emerging at the same time and persisting throughout the episode.

Even with larger context windows, agents must still compress, prioritize, and reinterpret information to maintain a usable internal state. These processes introduce structural biases that can lead to persistent misalignment. As a result, increasing context capacity does not fundamentally address the mechanisms that produce state drift.

6.4. State Drift as a Structural Limitation

Taken together, these findings indicate that state drift is a structural limitation of language-conditioned autonomy. Unlike errors that can be addressed through improved reasoning procedures or increased memory capacity, state drift arises from the interaction between language-based representation, partial observability, and long-horizon execution. This suggests that mitigating state drift will require explicit mechanisms for state verification, grounding, and correction, rather than relying solely on improved reasoning or increased context.

Importantly, state drift is not unique to a particular agent architecture or task. The abstraction level of language representations makes similar failure modes likely to arise across a wide range of language-conditioned systems. Recognizing state drift as a distinct phenomenon is therefore a necessary step toward building more reliable autonomous agents.

6.5. Implications for Agent Design

Our analysis has several implications for the design of future language-conditioned agents. First, internal state representations should be treated as hypotheses about the environment that require periodic validation, rather than as authoritative records. Second, memory mechanisms should prioritize state consistency in addition to information retention. Finally, evaluation protocols for autonomous agents should include measures of state alignment over time, rather than focusing exclusively on task success or reasoning quality.

These considerations suggest a shift in emphasis from purely improving reasoning capabilities to explicitly managing the relationship between internal representations and external reality. Addressing state drift may therefore be essential for enabling robust long-horizon autonomy in language-conditioned systems.

7. Limitations and Future Work

This work represents an initial investigation into state drift in language-conditioned autonomous agents, and several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our experiments are conducted in controlled, text-based environments that allow direct access to ground-truth state. While this setting is necessary for isolating and measuring state drift, it does not capture the full complexity of real-world environments, where state may be noisy, continuous, or only partially observable to the experimenter.

Second, our analysis focuses on a limited set of agent configurations and task types. Although consistent drift behavior is observed across the evaluated settings, broader validation across diverse environments, interaction modalities, and agent architectures is required to assess the generality of these findings. In particular, embodied agents and multi-agent settings may exhibit additional forms of state drift not captured in this study.

Third, the proposed drift metric relies on fact-level comparisons between internal textual state and environment state. While this approach provides interpretability and experimental control, it may not capture more subtle forms of semantic misalignment. Future work could explore richer semantic representations, learned alignment measures, or hybrid symbolic–semantic metrics to better characterize drift in complex tasks.

Finally, this work does not propose or evaluate explicit mitigation strategies for state drift. The primary goal is to identify and characterize the phenomenon rather than to resolve it. Developing mechanisms for state verification, correction, and grounding such as explicit consistency checks or environment-aware memory updates remains an important direction for future research.

8. Conclusions

Language-conditioned autonomous agents have demonstrated impressive reasoning and planning capabilities, yet their reliability in long-horizon tasks remains limited. In this work, we identify state drift as a fundamental failure mode in such agents, characterized by the divergence between an agent’s internal textual state and the true environment state over time. Through controlled experiments, we show that state drift emerges and persists even when local reasoning steps remain coherent and despite increased context capacity.

Our findings suggest that long-horizon failures in language-conditioned agents cannot be fully explained by reasoning errors, hallucinations, or context limitations alone. Instead, they point to a structural challenge arising from the use of natural language as an internal state representation. By formally defining state drift and empirically isolating its effects, this work highlights state consistency as a first-class concern in the design and evaluation of autonomous agents.

We hope that this study encourages further research into mechanisms for maintaining alignment between internal representations and external reality, and contributes to the development of more reliable language-conditioned autonomous systems capable of sustained interaction over long horizons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.S.; methodology, S.K.S.; software, S.K.S.; validation, S.K.S.; formal analysis, S.K.S.; investigation, S.K.S.; resources, S.K.S.; data curation, S.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.S.; writing—review and editing, S.K.S.; visualization, S.K.S.; supervision, S.K.S.; project administration, S.K.S. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals and therefore did not require ethical review or approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants, human data, or identifiable personal information, and therefore informed consent was not required.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author declares that no specific funding, technical assistance, or external support was received for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yao, S.; Rao, R.; Hausknecht, M.; Narasimhan, K. Keep CALM and Explore: Language Models for Action Generation in Text-based Games. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2020; pp. 8736–8754. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.03629. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, Vol. 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. Technical report. OpenAI, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Dessi, R.; Raileanu, M.; Lomeli, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Cancedda, N.; Scialom, T. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023; Vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Gonzalez, J.E. Gorilla: Large Language Model Connected with Massive APIs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.15334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, Vol. 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Schärli, N.; Hou, L.; Wei, J.; Scales, N.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Cui, C.; Bousquet, O.; Le, Q.; et al. Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Hu, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; et al. AgentBench: Evaluating LLMs as Agents. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A Survey of Hallucination in Large Foundation Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2309.05922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.05232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.F.; Zhang, T.; Liang, P.; Smith, N.A.; Saxena, A. Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2024, 12, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, B.; Chen, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Carin, L.; et al. LongLoRA: Efficient Fine-tuning of Long-Context Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, A.; Xu, K.; Zhu, J.; Hou, L.; Zhou, A.; Wang, J.; et al. LongBench: A Bilingual, Multitask Benchmark for Long Context Understanding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.14508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.M.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; et al. Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.W.; Hou, L.; Longpre, S.; Zoph, B.; Tay, Y.; Fedus, W.; Li, E.; Wang, X.; Dehghani, M.; Brahma, S.; et al. Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, Vol. 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation, 2023. arXiv [cs.AI]. arXiv:2308.08155.

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023; Vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Madaan, A.; Zhou, S.; Alon, U.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Program-Aided Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023; pp. 10765–10799. [Google Scholar]

- An, C.; Bai, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Lyu, A.; Zhu, J.; Hou, L.; Zhou, A.; Wang, J.; et al. Long Context Question Answering via Supervised Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Radev, D.; Neubig, G. LongEval: Guidelines for Human Evaluation of Faithfulness in Long-form Summarization. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; pp. 1610–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, C.; Fang, V.; Gao, K.; Martinez, J.D.; Austin, J.; Singh, S.K.; Longpre, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Moritz, W.; et al. MemGPT: Towards LLMs as Operating Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.08560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, Vol. 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M.W. Retrieval Augmented Language Model Pre-training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2020; pp. 3929–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Izacard, G.; Lewis, P.; Lomeli, M.; Hosseini, L.; Petroni, F.; Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Joulin, A.; Riedel, S.; Grave, E. Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelbling, L.P.; Littman, M.L.; Cassandra, A.R. Planning and Acting in Partially Observable Stochastic Domains. Artificial Intelligence 1998, 101, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Unifying Large Language Models and Knowledge Graphs: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.08302. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).