1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with most cases being diagnosed at the metastatic stage. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis have revolutionized the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC), significantly improving durable responses and survival outcomes [

1]. In current clinical practice, ICIs are frequently administered in combination with chemotherapy, which, while enhancing therapeutic efficacy, also increases the complexity of toxicity management [

2,

3].

Adverse events (AEs) associated with chemo-immunotherapy include both the conventional toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapy, such as myelosuppression, nausea, fatigue, and neuropathy, and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) induced by ICIs. IrAEs arise from the overactivation of the immune system and can affect virtually any organ system, including the skin, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and endocrine glands [

2]. The incidence of irAEs varies widely, with up to 70% of patients experiencing some form of toxicity and severe irAEs (grades 3–5) occurring in 10–20% of cases [

3]. This dual mechanism of toxicity necessitates rigorous clinical vigilance because these complications often require treatment interruption, immunosuppressive therapy, or permanent discontinuation of ICIs, potentially compromising their therapeutic efficacy [

4].

Despite advances in understanding the mechanisms underlying irAEs, reliable predictive biomarkers remain elusive [

5,

6]. Current candidates, such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB), are used to guide treatment selection but do not reliably correlate with the risk of developing toxicity [

7]. Genetic polymorphisms in immune-related genes have emerged as promising predictors of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Variants in genes such as

CTLA-4,

PDCD1, and Interleukin-7 (IL-7) have been associated with autoimmune diseases, cancer susceptibility, and treatment-related toxicities [

4,

5,

8].

IL-7, a cytokine critical for T cell development and homeostasis, plays a central role in the regulation of immune responses [

9]. Previous studies have linked the IL7 pathway to autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes, in which it modulates T cell activity and cytokine production [

10,

11]. Notably, IL-7 signaling enhances T-cell survival, proliferation, and effector function, which are key mechanisms underlying ICI efficacy [

12]. However, dysregulated IL-7 signaling may also contribute to immune overactivation, potentially increasing the risk of irAEs [

13]. The

IL7 gene variant rs16906115, located in an intronic regulatory region, functions as a cis-eQTL that has been implicated in the modulation of IL-7 expression and immune function [

14].

Although this variant has recently been explored as a predictor of ICI-related toxicities, with studies reporting positive associations between melanoma, lung cancer and other solid tumors and irAE development [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], its role in aNSCLC requires further evaluation across diverse populations to validate its clinical significance. Genetic effect sizes may differ due to ethnic diversity, disease heterogeneity, and treatment context [

20].

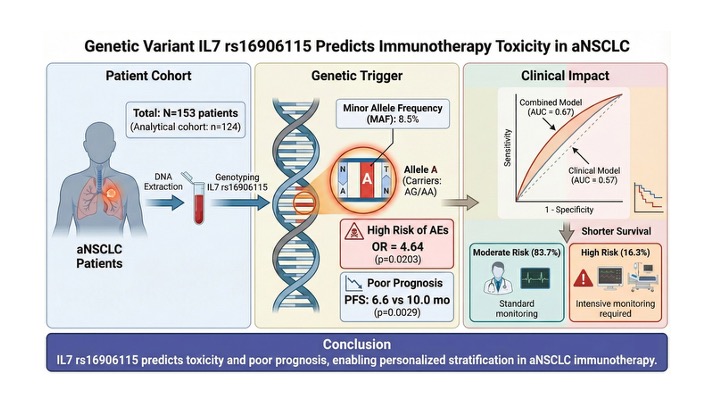

In this context, we investigated the association between the IL7 rs16906115 polymorphism and the development of AEs in a cohort of Spanish patients with aNSCLC treated with ICIs. We hypothesized that carriers of the minor A allele (AG/AA genotypes) are predisposed to an increased risk of AEs owing to enhanced IL-7-mediated immune activation. Furthermore, we explored the integration of this genetic variant into a clinical-genetic predictive model and evaluated its impact on survival outcomes to optimize patient stratification and monitoring in real-world clinical settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study involving 153 patients with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) between January 2018 and December 2023. The study was conducted at two tertiary care centers in Spain: Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital and Regional Hospital of Málaga. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histologically confirmed NSCLC, (2) advanced or metastatic disease (Stage IIIB–IV), (3) treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and (4) availability of high-quality genomic DNA (gDNA) samples. Exclusion criteria were prior immunotherapy, concomitant active autoimmune diseases, and incomplete clinical follow-up data. Although 153 patients were initially genotyped, the final analytical cohort for adverse event (AEs) association comprised 124 clinically informative patients. Twenty-nine patients were excluded from the primary outcome analysis due to missing or non-validated toxicity data.

2.2. Clinical Data and Adverse Event Assessment

Clinical and demographic data were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical records. The variables included age, sex, smoking status, histological subtype, PD-L1 expression, ECOG performance status, treatment regimens (ICI monotherapy vs. chemo-immunotherapy), and treatment response. Adverse events were systematically evaluated and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Both immune-related AEs (irAEs) and conventional toxicities were recorded. To ensure consistency and reduce bias, all AEs were reviewed by two independent investigators blinded to the genotyping results. Toxicity was stratified into low-grade (grades 0–2) and high-grade (grades 3–5) for the severity analysis.

2.3. DNA Extraction and IL7 rs16906115 Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples using the QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. IL7rs16906115 genotyping was performed using the TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on a QuantStudio 12 Flex Real-Time PCR System. Automated allele calling was performed using the QuantStudio Analysis Software v1.5.2. To ensure analytical validity, 10% of the samples were genotyped in duplicate, to achieve 100% agreement.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was assessed using a chi-square test to ensure that the population was in genetic equilibrium. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population, and associations between genotypes/alleles and AEs were evaluated using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated using logistic regression analysis. We evaluated three genetic models: additive, dominant, and recessive models. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify potential confounding factors. This model was adjusted for age, sex, and treatment modality (ICI monotherapy vs. chemo-immunotherapy) to ensure the independent predictive value of the genetic variant. A predictive risk model was developed by integrating the IL7 rs16906115 A allele count with clinical variables, including sex, histology, PD-L1 expression, and ECOG status. The predictive performance was evaluated using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) from the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R v4.2.1.

2.5. Survival Analysis

Exploratory survival analyses were conducted to evaluate the prognostic impact of IL7rs16906115 polymorphism. Overall Survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of immunotherapy to death from any cause. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation to radiological progression or death. Patients without adverse events were censored at the last follow-up visit. Given the low frequency of the homozygous risk genotype (n=2), survival comparisons were performed using a dominant genetic model, grouping carriers of the risk allele (AG/AA) versus noncarriers (GG). Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided and considered statistically significant.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Málaga Ethical Committee (reference number 04/02/2022). All participants provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 153 patients with aNSCLC treated with ICIs were included in the initial study population.

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the clinical characteristics of the analytical cohort of 124 patients with complete follow-up, stratified by AE status (71 with AEs and 53 without AEs). The median age of the cohort was 64 years old. Males comprised 66.7% of the total population, with a balanced distribution between the AE (74.6%) and non-AE groups (75.5% each). Adenocarcinoma was the most common histological subtype (54.9% of cases). PD-L1 positivity (≥1%) was observed in 83.7% of the cohort, with similar rates between toxicity strata. Pembrolizumab was the most commonly administered ICI (65.4%), followed by Atezolizumab (13.7%) and Nivolumab (6.5%).

3.2. IL7 rs16906115 Genotype Distribution and Association with Adverse Events

IL7 rs16906115 polymorphism was genotyped in all 153 patients, following the distribution of GG (n=129, 84.3%), AG (n=22, 14.4%), and AA (n=2, 1.3%). The minor allele frequency (MAF) of the A allele was 8.5%, which is consistent with the estimates for the European population. The genotype distribution was in Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (χ2 = 0.12, p = 0.73).

The association between

IL7 rs16906115 and AEs was assessed in 124 patients with clinical information (

Table 2). The AG genotype was significantly more frequent in the AEs group than in the non-AEs group (18.3% vs. 5.7%; OR = 3.03, 95% CI: 0.88–10.3, p = 0.037). Conversely, the GG genotype conferred a protective effect (OR 0.28 [95% CI 0.08–0.94]; P = 0.015). At the allele level, the minor A allele was significantly associated with a 3.71-fold increased risk of AEs (12.0% vs. 2.8%, P = 0.0081). This association remained consistent across treatment modalities and was observed in both ICI monotherapy (OR = 3.58, p = 0.045) and chemoimmunotherapy (OR = 3.59, p = 0.044) subgroups.

3.3. Genetic Models and Multivariable Analysis

Given the rarity of the homozygous variant (n=2), dominant coding was adopted to preserve the statistical power. Although this approach identified a significant risk group, additive effects could not be excluded and formal model discrimination was not feasible. Multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex confirmed that patients carrying the A allele (AG/AA) had a significantly higher risk of developing AEs (OR = 4.64, 95%CI: 1.5–17.24, P = 0.0203) (

Table 2, bottom row).

3.4. Association with Clinical Subgroups and Outcomes

No significant associations were observed between IL7rs16906115 genotypes and baseline clinical features such as PD-L1 expression, histological subtype, or sex. However, significant differences were observed in survival outcomes, as detailed below.

Table 3.

Association of IL7 Genotype with Clinical Outcomes. Impact of risk alleles on toxicity severity and survival metrics.

Table 3.

Association of IL7 Genotype with Clinical Outcomes. Impact of risk alleles on toxicity severity and survival metrics.

| Clinical Feature |

Non-Carriers (GG) |

Risk Carriers (AG/AA) |

P-value |

| Toxicity Severity, n (%) |

n=106 |

n=18 |

|

| Low Grade (1-2) |

89 (84.0%) |

16 (88.9%) |

0.86 |

| High Grade (3-5) |

17 (16.0%) |

2 (11.1%) |

|

| Survival Outcomes, median (months) |

n=96 |

n=19 |

|

| Progression-Free Survival (PFS) |

10.0 (8.2 –11.9) |

6.6 (4.4 – 8.8) |

0.0029 |

| Overall Survival (OS) |

13.0 (9.6–17.6) |

8.3 (4.2–NR) |

0.03 |

3.5. Predictive Scoring Model for AE Risk

A predictive model integrating the

IL7 genotype and key clinical features was developed to stratify the AE risk. Most patients were stratified into the moderate-risk group (n=106, 83.7%), with a predicted probability of AEs between 30% and 70%. Fourteen patients (16.3%) were identified as high-risk (>70% probability), necessitating intensive monitoring (

Table 4). The combined clinical-genetic model achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.67. Numerically, the predictive capacity was improved compared with the clinical-only model (AUC = 0.67 vs. 0.57), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 1). These findings highlight the superior predictive capacity of pharmacogenetic data integration for clinical stratification.

3.6. Association of IL7 Genotype with Survival Outcomes

We further investigated whether the IL7 variant, in addition to predicting toxicity, was correlated with the clinical efficacy. In the survival analysis, the patients were stratified into risk allele carriers (genotypes AG and AA, n=20) and protective homozygotes (genotype GG, n=96).

As shown in

Figure 2, carriers of the A allele exhibited significantly poorer outcomes than those of the GG group. The median Progression-Free Survival (PFS) was significantly shorter in the risk group (6.6 months; 95% CI: 4.4– 8.8) than in the protective group (10.0 months; 95% CI: 8.2–11.9) (log-rank p=0.0029).

Regarding Overall Survival (OS), the analysis also revealed a statistically significant difference (log-rank p = 0.03). The risk group showed a median OS of 8.3 months (95% CI: 4.2–NR), whereas the protective group had a median OS of 13.0 months (95% CI: 9.6–17.6 months). These findings indicate that the IL7 rs16906115 A allele serves not only as a predictor of toxicity but also as a marker of poor prognosis, associated with both earlier progression and reduced overall survival.

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Plausibility and Mechanistic Insight

The biological link between the

IL7 rs16906115 polymorphism and ICI induced toxicity is rooted in the fundamental role of this cytokine in T-cell homeostasis. This variant, located in an intronic regulatory region, functions as a cis-eQTL that modulates IL-7 expression [

15,

16]. Carriers of the minor A allele exhibit increased

IL7 transcription, which is essential for the survival, proliferation, and effector functions of CD8+ T cells. Although this immune amplification is key to ICI efficacy, it appears to lower the threshold of immune overactivation. Our findings suggest that the A allele acts as a genetic "trigger" for AEs independent of the treatment modality (monotherapy vs. chemo-immunotherapy). Notably, the significant association observed in the ICI monotherapy subgroup (OR = 3.58) reinforces that this effect is driven by immune-mediated mechanisms rather than by non-specific chemotherapy toxicity.

Typically, the occurrence of irAEs is often correlated with an improved tumor response in patients treated with ICIs, which is interpreted as a sign of robust immune activation. However, our study revealed a dual detrimental effect of the IL7 rs16906115 A allele. Carriers of this variant not only experienced higher rates of toxicity but also demonstrated significantly shorter Progression-Free Survival (6.6 vs. 10.0 months, p=0.0029). This finding challenges the conventional paradigm in this genetic context. We hypothesized that the constitutive overexpression of IL-7 in A-allele carriers may lead to a dysregulated pro-inflammatory immune milieu rather than an effective anti-tumor response. Excessive IL-7 signaling could promote the exhaustion of CD8+ T-cells or the activation of lower-affinity T-cell clones, which cause tissue damage (toxicity) without effectively clearing the tumor. Thus, the rs16906115 variant has emerged as a biomarker of unfavorable prognosis, identifying a subgroup of patients at risk of both severe adverse events and early disease progression.

4.2. Comparison with Prior Studies and Population Specificity

The association between the

IL7 rs16906115 A allele and irAEs was first established in melanoma patients by Taylor et al. (2018) and Groha et al. (2022) [

15,

16]. Our results corroborate these findings in aNSCLC, showing a significant independent association with an adjusted Odds Ratio of 4.64 (95% CI: 1.50–17.2, p = 0.0203). The minor allele frequency (MAF) in our Spanish cohort was 8.5%, which is slightly lower than the frequencies reported in Northern European populations (~12–15%) but consistent with Mediterranean estimates from the 1000 Genomes Project [

21]. This underscores the importance of population-specific validation for clinical implementation, as the effect sizes and genetic backgrounds may vary across ancestries.

4.3. Clinical Utility and Predictive Performance

A critical finding of our study was the development of an integrated clinical-genetic risk model. Although the clinical model alone achieved an AUC of 0.57, the addition of the IL7 genotype increased the predictive performance to an AUC of 0.67. Although moderate, this performance is superior to clinical stratification alone and highlights the potential of using a single SNP to identify high-risk patients with aNSCLC. In our cohort, this model successfully stratified 16.3% of patients into a "high-risk" group, warranting intensive monitoring.

Regarding severity, to ensure data robustness, adverse events were systematically evaluated and graded according to the CTCAE v5.0 and reviewed by two independent investigators blinded to the genotyping results. Based on this, no significant association was observed between

IL7 genotype and toxicity grade (

Table 3). However, severity analyses pooled immune- and chemotherapy-related toxicities, suggesting that irAE-specific severity effects require stratified evaluations in future studies.

Finally, the association was analyzed using a dominant genetic model. Given the low frequency of homozygous risk carriers (n=2), this coding was primarily chosen to maximize the statistical power. We acknowledge that model discrimination between dominant and additive inheritance was limited by this rarity; thus, the inference of a dominant pattern should be considered provisional pending validation in larger cohorts."

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design may have introduced a selection bias. Second, the relatively small sample size (N=153, with n=124 in the analytical cohort) and low frequency of the homozygous risk genotype (n=2) limited our statistical power to detect recessive effects. Third, we did not perform functional assays such as measuring serum IL-7 levels, which would have provided direct evidence for the proposed mechanism. Future research should explore the integration of rs16906115 into polygenic risk scores (incorporating variants in

CTLA4or

PDCD1) and multi-omics models. Large-scale prospective studies are required to validate survival findings and determine whether genotype-informed management can reduce the incidence of severe toxicity without compromising antitumor efficacy. Finally, regarding the predictive model, while the integration of the

IL7 genotype improved the AUC compared with clinical features alone, this difference was not statistically significant. Due to sample size constraints and the single-center retrospective design, we could not perform formal external validation or robust calibration analyses. Therefore, the risk stratification proposed in

Figure 1a should be interpreted as exploratory risk stratification. Future multicenter studies are required to validate the model's discrimination ability in independent cohorts before clinical implementation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study validated the IL7 rs16906115 polymorphism as a significant pharmacogenetic predictor of adverse events in Spanish patients with advanced NSCLC treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The identification of the minor A allele as a risk factor, independent of treatment modality, represents a clinically actionable advance that enables pre-therapeutic risk stratification. Furthermore, the association of this variant with shorter progression-free survival suggests its potential utility as a prognostic biomarker. Integrating this genetic marker into routine clinical workflows using our combined clinical-genetic model could optimize patient safety by permitting tailored toxicity monitoring and informing personalized management strategies in the era of precision immuno-oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.-D. and J.O.; Methodology, A.G.-H. G.P.-L, B.MG.; Formal Analysis, A.G.-H,G.P.-L and JO.; Investigation and Data Curation, A.R.-D., E.P.-R., and J.O.; Resources, A.R.-D., I.B., E.P.-R., and J.C.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.P.-L., F.V.P., J.O., and A.G.-H.; Writing—Review and Editing, all authors; Supervision, J.O. and A.R.-D.; Project Administration, J.O.; Funding Acquisition, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Consejería de Conocimiento, Investigación y Universidad, Junta de Andalucía, grant number PAIDI P21-01002. J.O. holds a “Nicolas Monardes” research contract from the Andalusian Regional Ministry of Health (grant number C1-0003-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Málaga (date of approval: 04/02/2022).Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Paperpal and Google Gemini to improve the language readability, grammatical correctness, and sentence structure. The tool was used to refine the clarity of the Introduction and Discussion sections. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge Laura Figueroa for her technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| AEs |

Adverse Events |

| aNSCLC |

Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CTCAE |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| eQTL |

Expression Quantitative Trait Locus |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| ICIs |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| IL-7 |

Interleukin-7 |

| irAEs |

Immune-related Adverse Events |

| MAF |

Minor Allele Frequency |

| NSCLC |

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| OS |

Overall Survival |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

References

- Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, K.L.; Baas, P.; Crinò, L.; Eberhardt, W.E.E.; Poddubskaya, E.; Antonia, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Vokes, E.E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 373, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, Activity, and Immune Correlates of Anti–PD-1 Antibody in Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, B.; Mian, F.; Franchini, F.; Au-Yeung, G.; IJzerman, M. Cancer and Treatment Specific Incidence Rates of Immune-Related Adverse Events Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Br J Cancer 2025, 132, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti, B.; Genova, C.; De Giglio, A.; Bassanelli, M.; Dal Bello, M.G.; Metro, G.; Brambilla, M.; Baglivo, S.; Grossi, F.; Chiari, R. Impact of Immune-Related Adverse Events on Survival in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Nivolumab: Long-Term Outcomes from a Multi-Institutional Analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019, 145, 479–485. [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Pluzanski, A.; Lee, J.S.; Otterson, G.A.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Minenza, E.; Linardou, H.; Burgers, S.; Salman, P.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [CrossRef]

- Queirolo, P.; Dozin, B.; Morabito, A.; Banelli, B.; Piccioli, P.; Fava, C.; Leo, C.; Carosio, R.; Laurent, S.; Fontana, V.; et al. Association of CTLA-4 Gene Variants with Response to Therapy and Long-Term Survival in Metastatic Melanoma Patients Treated with Ipilimumab: An Italian Melanoma Intergroup Study. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 386. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Hammer, C.; Carroll, J.; Di Nucci, F.; Acosta, S.L.; Maiya, V.; Bhangale, T.; Hunkapiller, J.; Mellman, I.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Genetic Variation Associated with Thyroid Autoimmunity Shapes the Systemic Immune Response to PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3355. [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, V.; Berman, D.; Chasalow, S.D.; Wang, L.; Tsuchihashi, Z.; Hu, B.; Panting, L.; Jure-Kunkel, M.; Ji, R.-R. Gene Expression Profiling of Whole Blood in Ipilimumab-Treated Patients for Identification of Potential Biomarkers of Immune-Related Gastrointestinal Adverse Events. J Transl Med 2013, 11, 75. [CrossRef]

- Fry, T.J.; Mackall, C.L. Interleukin-7: From Bench to Clinic. Blood 2002, 99, 3892–3904. [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.A.; Walker, N.M.; Cooper, J.D.; Smyth, D.J.; Downes, K.; Plagnol, V.; Bailey, R.; Nejentsev, S.; Field, S.F.; Payne, F.; et al. Robust Associations of Four New Chromosome Regions from Genome-Wide Analyses of Type 1 Diabetes. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 857–864. [CrossRef]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium; Hafler, D.A.; Compston, A.; Sawcer, S.; Lander, E.S.; Daly, M.J.; De Jager, P.L.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Gabriel, S.B.; Mirel, D.B.; et al. Risk Alleles for Multiple Sclerosis Identified by a Genomewide Study. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 851–862. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, R.; Durum, S.K. Interleukin-7 Receptor Expression: Intelligent Design. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7, 144–154. [CrossRef]

- Lundström, W.; Highfill, S.; Walsh, S.T.R.; Beq, S.; Morse, E.; Kockum, I.; Alfredsson, L.; Olsson, T.; Hillert, J.; Mackall, C.L. Soluble IL7Rα Potentiates IL-7 Bioactivity and Promotes Autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E1761-1770. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S.G.; Schmidt, S.; Seth, P.; Oksenberg, J.R.; Hart, J.; Prokop, A.; Caillier, S.J.; Ban, M.; Goris, A.; Barcellos, L.F.; et al. Interleukin 7 Receptor Alpha Chain (IL7R) Shows Allelic and Functional Association with Multiple Sclerosis. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 1083–1091. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Watson, R.A.; Tong, O.; Ye, W.; Nassiri, I.; Gilchrist, J.J.; de los Aires, A.V.; Sharma, P.K.; Koturan, S.; Cooper, R.A.; et al. IL7 Genetic Variation and Toxicity to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Patients with Melanoma. Nat Med 2022, 28, 2592–2600. [CrossRef]

- Groha, S.; Alaiwi, S.A.; Xu, W.; Naranbhai, V.; Nassar, A.H.; Bakouny, Z.; El Zarif, T.; Saliby, R.M.; Wan, G.; Rajeh, A.; et al. Germline Variants Associated with Toxicity to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Nat Med 2022, 28, 2584–2591. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Kondo, Y.; Itobayashi, E.; Uehara, M.; Hiraoka, A.; Kudo, M.; Kakizaki, S.; Kagawa, T.; Miuma, S.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Evaluation of the Associations of Interlukin-7 Genetic Variants with Toxicity and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Replication Study of a Japanese Population, Based on the Findings of a European Genome-Wide Association Study. Hepatology Research n/a. [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.; Mehrabad, E.M.; Labaki, C.; Saliby, R.M.; Semaan, K.; Eid, M.; Machaalani, M.; Chehade, R.E.H.; Nawfal, R.; Sun, M.; et al. 22 Association of a Germline Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) in the Interleukin-7 (IL7) Gene with Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs). Oncologist 2024, 29, S1–S2. [CrossRef]

- Takada, H.; Osawa, L.; Komiyama, Y.; Muraoka, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Sato, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Takano, S.; Maekawa, S.; et al. Interleukin-7 Risk Allele, Lymphocyte Counts, and Autoantibodies for Prediction of Risk of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Receiving Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab Therapy for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncology 2024, 103, 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Haratani, K.; Hayashi, H.; Chiba, Y.; Kudo, K.; Yonesaka, K.; Kato, R.; Kaneda, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Takeda, M.; et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events With Nivolumab Efficacy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 374–378. [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |