Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Research

2.1. Functional Foods and Complex Health Claims: The Case of Low-GI

2.2. Labels as Signals under Information Asymmetry

2.3. Nutritional Context, Congruence, and Halo Effects

2.4. Consumer Heterogeneity: Health Orientation and Nutrition Knowledge as a “Decoder”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Administration and Participants

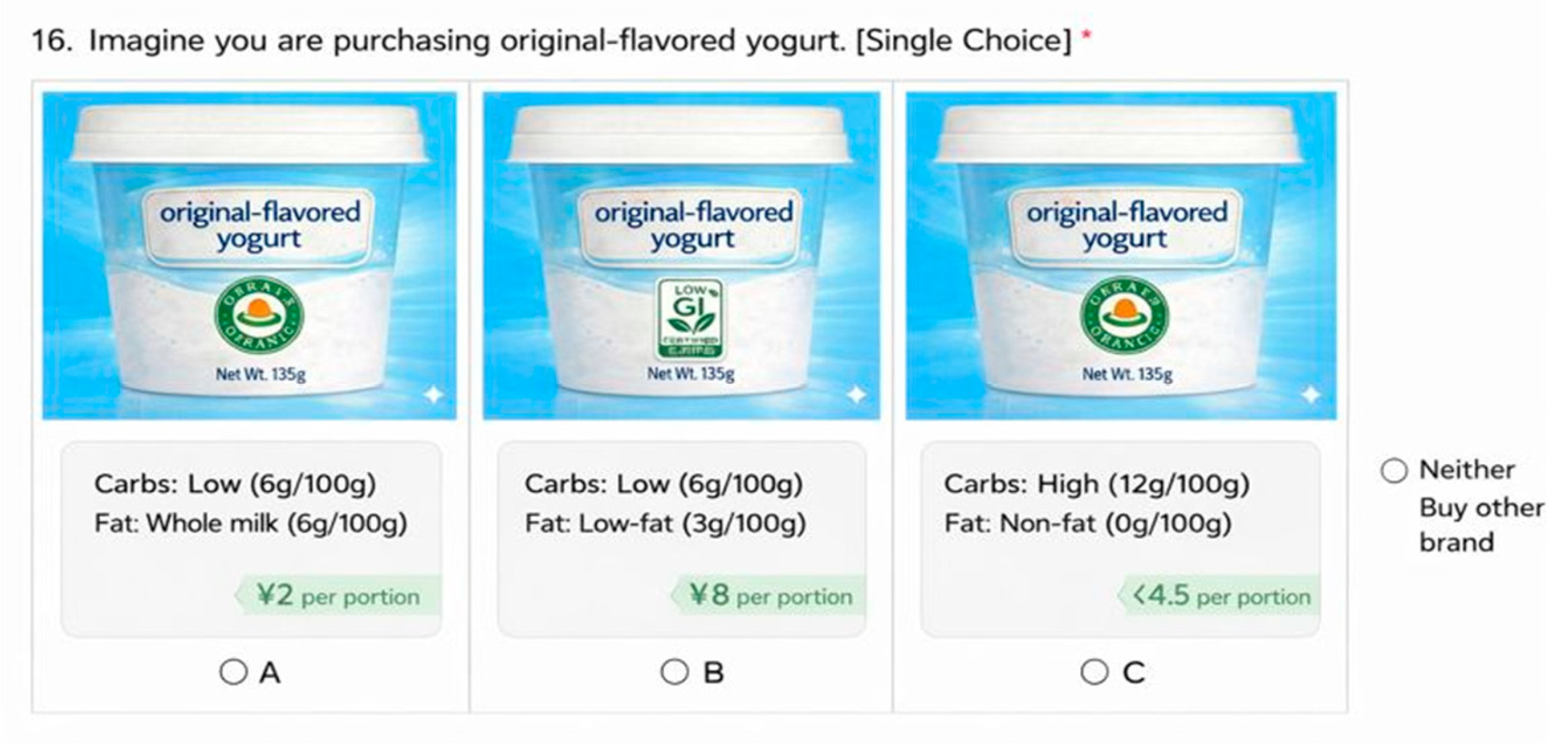

3.2. Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE): Attributes and Design

3.3. Variable construction

3.4. Econometric Specification and Model Strategy

3.4.1. Random Utility Framework

3.4.2. Mixed Logit Estimation

3.4.3. Model Sequence

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. General Consumer Preferences: Baseline Results (Model 1)

4.3. Moderating Effects of Context and Individual Characteristics (Models 2 and 3)

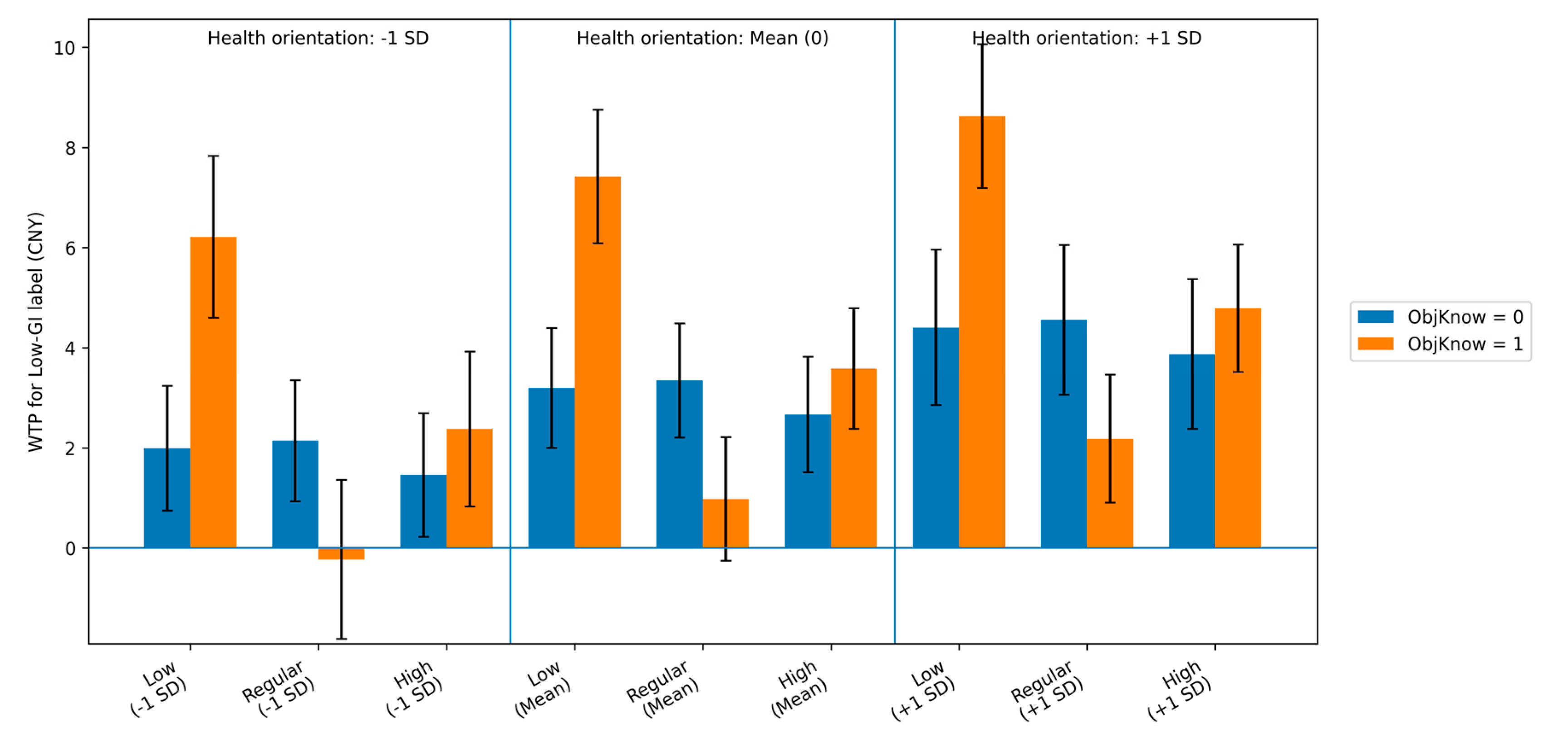

4.4. The "Decoder" Role of Knowledge

4.5. Willingness to Pay (WTP) Estimates and Economic Implications

5. Discussion

5.1. General Preference for Low-GI Labeling (Baseline Valuation)

5.2. The Role of Health Motivation

5.3. The Role of Nutritional Context and Knowledge

5.4. Implications for Industry and Policy

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOP | Front-of-pack |

| GI | Glycemic Index |

| WTP | Willingness to Pay |

| DCE | Discrete Choice Experiment |

| RUT | Random Utility Theory |

| MIXL | Mixed Logit |

| ASC | Alternative-Specific Constant |

| CNY | Chinese Yuan |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

Appendix A

References

- Augustin, L.S.A.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Willett, W.C.; Astrup, A.; Barclay, A.W.; Björck, I.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; Brighenti, F.; Buyken, A.E.; et al. Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load and Glycemic Response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2015, 25, 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Taylor, R.H.; Barker, H.; Fielden, H.; Baldwin, J.M.; Bowling, A.C.; Newman, H.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Goff, D.V. Glycemic Index of Foods: A Physiological Basis for Carbohydrate Exchange. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1981, 34, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachos, D.; Malisova, S.; Lindberg, F.A.; Karaniki, G. Glycemic Index (GI) or Glycemic Load (GL) and Dietary Interventions for Optimizing Postprandial Hyperglycemia in Patients with T2 Diabetes: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Teng, D.; Shi, X.; Qin, G.; Qin, Y.; Quan, H.; Shi, B.; Sun, H.; Ba, J.; Chen, B.; et al. Prevalence of Diabetes Recorded in Mainland China Using 2018 Diagnostic Criteria from the American Diabetes Association: National Cross Sectional Study. BMJ 2020, m997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, A.W.; Augustin, L.S.A.; Brighenti, F.; Delport, E.; Henry, C.J.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Usic, K.; Yuexin, Y.; Zurbau, A.; Wolever, T.M.S.; et al. Dietary Glycaemic Index Labelling: A Global Perspective. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H.L. The Glycemic Index Concept in Action. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 87, 244S–246S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, T.M. Yogurt Is a Low–Glycemic Index Food. The Journal of Nutrition 2017, 147, 1462S–1467S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bhargava, N.; O’Connor, A.; Gibney, E.R.; Feeney, E.L. Dairy Consumption in Adults in China: A Systematic Review. BMC Nutr 2023, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Russell, S.J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M. Front of Pack Nutritional Labelling Schemes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Recent Evidence Relating to Objectively Measured Consumption and Purchasing. J Human Nutrition Diet 2020, 33, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, I.; Sotgiu, F.; Aydinli, A.; Verlegh, P.W.J. Consumer Effects of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling: An Interdisciplinary Meta-Analysis. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabber, M. Complexities of Consumer Understanding of the Glycaemic Index Concept and Practical Guidelines for Incorporation in Diets. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005, 18, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.; Doxey, J.; Hammond, D. Nutrition Labels on Pre-Packaged Foods: A Systematic Review. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunert, K.G.; Wills, J.M.; Fernández-Celemín, L. Nutrition Knowledge, and Use and Understanding of Nutrition Information on Food Labels among Consumers in the UK. Appetite 2010, 55, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, V.H.; Hess, R.; Siegrist, M. Health Motivation and Product Design Determine Consumers’ Visual Attention to Nutrition Information on Food Products. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and Validity of a Revised Version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Neal, B.; Dixon, H.; Hughes, C.; Kelly, B.; Miller, C. Consumers’ Responses to Health Claims in the Context of Other on-Pack Nutrition Information: A Systematic Review. Nutrition Reviews 2017, 75, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancsar, E.; Louviere, J. Conducting Discrete Choice Experiments to Inform Healthcare Decision Making: A User??S Guide. PharmacoEconomics 2008, 26, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louviere, J.J.; Hensher, D.A.; Swait, J.D.; Adamowicz, W. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2000; ISBN 978-0-521-78830-4. [Google Scholar]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2001; ISBN 978-0-521-76655-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed, Z.; Sugino, H.; Sakai, Y.; Yagi, N. Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Mud Crabs in Southeast Asian Countries: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Foods 2021, 10, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Hartmann, M.; Langen, N. The Role of Trust in Explaining Food Choice: Combining Choice Experiment and Attribute Best–Worst Scaling. Foods 2020, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Menozzi, D.; Török, Á. Eliciting Egg Consumer Preferences for Organic Labels and Omega 3 Claims in Italy and Hungary. Foods 2020, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Verain, M.C.D.; Snoek, H.M. The Development of a Single-Item Food Choice Questionnaire. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 71, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. Journal of Management 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranove, D.; Jin, G.Z. Quality Disclosure and Certification: Theory and Practice. Journal of Economic Literature 2010, 48, 935–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenbach, L.H.; Slits, E.; Robinson, E.; Sacks, G. Systematic Review of the Impact of Nutrition Claims Related to Fat, Sugar and Energy Content on Food Choices and Energy Intake. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.S.; Cassady, D.L. The Effects of Nutrition Knowledge on Food Label Use. A Review of the Literature. Appetite 2015, 92, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.C.; Ynion, J.; Demont, M.; De Steur, H. Consumers’ Acceptance and Valuation of Healthier Rice: Implications for Promoting Healthy Diets in the Philippines. British Food Journal 2025, 127, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, O.Q.; Connor, M.; Demont, M.; Sander, B.O.; Nelson, K. How Do Rice Consumers Trade off Sustainability and Health Labels? Evidence from Vietnam. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1010161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Consumer Perception of Functional Foods: A Conjoint Analysis with Probiotics. Food Quality and Preference 2013, 28, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouns, F.; Bjorck, I.; Frayn, K.N.; Gibbs, A.L.; Lang, V.; Slama, G.; Wolever, T.M.S. Glycaemic Index Methodology. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Dumais, L.; Barber, J. Health Canada’s Evaluation of the Use of Glycemic Index Claims on Food Labels. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 98, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanelli, M.D.M.; Batista, L.D.; Martinez-Arroyo, A.; Mozaffarian, D.; Micha, R.; Rogero, M.M.; Fisberg, R.M.; Sarti, F.M. Pragmatic Carbohydrate Quality Metrics in Relation to Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Front-of-Pack Warning Labels in Grain Foods. Foods 2024, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, S.-R.S.; McMahon, A.T.; Neale, E.P. A Cross-Sectional Audit of Nutrition and Health Claims on Dairy Yoghurts in Supermarkets of the Illawarra Region of New South Wales, Australia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, M.R.; Karni, E. Free Competition and the Optimal Amount of Fraud. The Journal of Law and Economics 1973, 16, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, J.A.; Mojduszka, E.M. Using Informational Labeling to Influence the Market for Quality in Food Products. American J Agri Economics 1996, 78, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonroy, O.; Constantatos, C. On the Economics of Labels: How Their Introduction Affects the Functioning of Markets and the Welfare of All Participants. American J Agri Economics 2015, 97, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trijp, H.C.M.; Van Der Lans, I.A. Consumer Perceptions of Nutrition and Health Claims. Appetite 2007, 48, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; Bucher, T.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Egan, B.; Collins, C.E.; Dean, M. The Impact of Nutrition and Health Claims on Consumer Perceptions and Portion Size Selection: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey. Nutrients 2018, 10, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. A Systematic Review, and Meta-Analyses, of the Impact of Health-Related Claims on Dietary Choices. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.; Levy, A.S.; Derby, B.M. The Impact of Health Claims on Consumer Search and Product Evaluation Outcomes: Results from FDA Experimental Data. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 1999, 18, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, G.T.; Hastak, M.; Mitra, A.; Ringold, D.J. Can Consumers Interpret Nutrition Information in the Presence of a Health Claim? A Laboratory Investigation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 1996, 15, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Garretson, J.A.; Burton, S. Effects of Nutrition Facts Panel Values, Nutrition Claims, and Health Claims on Consumer Attitudes, Perceptions of Disease-Related Risks, and Trust. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 2000, 19, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bix, L.; Sundar, R.P.; Bello, N.M.; Peltier, C.; Weatherspoon, L.J.; Becker, M.W. To See or Not to See: Do Front of Pack Nutrition Labels Affect Attention to Overall Nutrition Information? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialkova, S.; Van Trijp, H. What Determines Consumer Attention to Nutrition Labels? Food Quality and Preference 2010, 21, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta-Bergman, M.J. Health Attitudes, Health Cognitions, and Health Behaviors among Internet Health Information Seekers: Population-Based Survey. J Med Internet Res 2004, 6, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The Role of Health Consciousness, Food Safety Concern and Ethical Identity on Attitudes and Intentions towards Organic Food. Int J Consumer Studies 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. J CONSUM RES 1987, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetin, J.; Caputo, V.; Demartini, E.; Conner, M.; Perugini, M. Organic Food Labels Bias Food Healthiness Perceptions: Estimating Healthiness Equivalence Using a Discrete Choice Experiment. Appetite 2022, 172, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dando, R. Impact of Common Food Labels on Consumer Liking in Vanilla Yogurt. Foods 2019, 8, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Rossiter, J.R. The Predictive Validity of Multiple-Item versus Single-Item Measures of the Same Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 2007, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A. Response Strategies for Coping with the Cognitive Demands of Attitude Measures in Surveys. Applied Cognitive Psychology 1991, 5, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.B.; Landry, M.; Olson, J.; Velliquette, A.M.; Burton, S.; Andrews, J.C. The Effects of Nutrition Package Claims, Nutrition Facts Panels, and Motivation to Process Nutrition Information on Consumer Product Evaluations. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 1997, 16, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Levels | Unit / description |

| Low-GI label | Absent; Present | Front-of-pack label shown as an icon. In the questionnaire, the items were presented as follows: Prior to the DCE, respondents were shown the Low-GI logo and informed that it denotes a Low-GI label; no additional information about health benefits was provided. |

| Carbohydrate content | Low; Regular; High | Values per 100 g of yogurt (auxiliary numeric information). |

| Fat content | Skim; Low-fat; Whole-fat | Values per 100 g of yogurt (auxiliary numeric information). |

| Organic label | Absent; Present | Certification label shown as an icon. In the questionnaire, the items were presented as follows: Before the DCE began, we showed respondents this image and informed them that it represents an Organic label. |

| Price | 2; 4.5; 8 | CNY per 135 g serving. |

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

| Gender | Male | 456 | 50.110 |

| Female | 454 | 49.890 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 267 | 29.341 |

| 26–35 | 197 | 21.648 | |

| 36–45 | 191 | 20.989 | |

| 46–55 | 185 | 20.330 | |

| 56–65 | 29 | 3.187 | |

| > 65 | 41 | 4.505 | |

| Education | Middle school or below | 147 | 16.154 |

| High school / Vocational school | 276 | 30.330 | |

| Associate degree | 254 | 27.912 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 180 | 19.780 | |

| Master’s degree | 24 | 2.637 | |

| Doctoral degree | 13 | 1.429 | |

| Other / Prefer not to say | 16 | 1.758 | |

| Residence | Tier-1 city | 140 | 15.385 |

| New Tier-1 city | 134 | 14.725 | |

| Tier-2 city | 155 | 17.033 | |

| Tier-3 or below / County-level | 164 | 18.022 | |

| Town / Rural area | 162 | 17.802 | |

| Other regions | 155 | 17.033 | |

| Monthly Income (CNY) | < 5,000 | 488 | 53.626 |

| 5,000–9,999 | 235 | 25.824 | |

| 10,000–19,999 | 93 | 10.220 | |

| 20,000–29,999 | 34 | 3.736 | |

| 30,000–49,999 | 34 | 3.736 | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 13 | 1.429 | |

| Prefer not to say | 13 | 1.429 | |

| Purchase Frequency (past month) |

Never | 105 | 11.538 |

| Once | 250 | 27.473 | |

| 2–3 times | 471 | 51.758 | |

| ≥ 4 times | 84 | 9.231 | |

| Objective Low-GI knowledge | Selected the scientifically correct definition: a more gradual blood glucose rise given the same carbohydrate intake (ObjKnow=1) | 423 | 46.484 |

| Interpreted Low-GI as having lower carbohydrate or sugar content | 256 | 28.132 | |

| Interpreted Low-GI as involving less carbohydrate or sugar absorption by the body | 182 | 20.000 | |

| Reported not knowing the definition | 49 | 5.385 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Opt-out behavior | Opt-out rate | 0.074 | 0.134 |

| Health orientation | Index score | 4.201 | 1.510 |

| ObjKnow=1 | ObjKnow=1 (correct definition) | 0.465 | 0.499 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Panel A. Mean coefficients | |||

| ASC_buy | 1.859*** (0.051) |

1.907*** (0.054) |

1.900*** (0.054) |

| Price | -0.094*** (0.004) |

-0.094*** (0.005) |

-0.094*** (0.005) |

| Low-GI label | 0.331*** (0.028) |

0.192*** (0.050) |

0.313*** (0.053) |

| Organic label | 0.152*** (0.024) |

0.150*** (0.024) |

0.150*** (0.024) |

| Fat: skim | -0.193*** (0.026) |

-0.199*** (0.026) |

-0.202*** (0.026) |

| Fat: whole | -0.324*** (0.027) |

-0.327*** (0.027) |

-0.330*** (0.027) |

| Carb: low | 0.175*** (0.034) |

0.035 (0.044) |

0.030 (0.043) |

| Carb: high | -0.034 (0.033) |

-0.074* (0.045) |

-0.081* (0.044) |

| Low-GI × Carb: low | — | 0.271*** (0.058) |

-0.014 (0.070) |

| Low-GI × Carb: high | — | 0.068 (0.058) |

-0.064 (0.070) |

| Low-GI × Health orientation | — | 0.075*** (0.023) |

0.075*** (0.023) |

| Low-GI × Objective knowledge | — | 0.063 (0.059) |

-0.222*** (0.075) |

| ObjKnow × Low-GI × Carb: low | — | — | 0.617*** (0.086) |

| ObjKnow × Low-GI × Carb: high | — | — | 0.307*** (0.085) |

| Panel B. Standard deviations of random parameters | |||

| SD: Low-GI label | 0.181*** (0.032) |

0.056 (0.045) |

0.066 (0.044) |

| SD: Fat skim | 0.194*** (0.034) |

0.205*** (0.034) |

0.199*** (0.035) |

| SD: Fat whole | 0.208*** (0.035) |

0.195*** (0.036) |

0.185*** (0.037) |

| SD: Organic | 0.265*** (0.028) |

0.257*** (0.029) |

0.256*** (0.029) |

| SD: Carb low | 0.561*** (0.038) |

0.550*** (0.038) |

0.473*** (0.040) |

| SD: Carb high | 0.507*** (0.038) |

0.495*** (0.038) |

0.446*** (0.039) |

| Model fit statistics | |||

| Respondents | 910 | 910 | 910 |

| Choice tasks | 10,920 | 10,920 | 10,920 |

| Observations | 43,680 | 43,680 | 43,680 |

| Log likelihood | -13,539.629 | -13,519.872 | -13,494.501 |

| AIC | 27137.26 | 27105.74 | 27059.00 |

| BIC | 27389.11 | 27392.34 | 27362.96 |

| Carbohydrate context | ObjKnow = 0 WTP (SE) [95% CI] |

ObjKnow = 1 WTP (SE) [95% CI] |

| Health orientation = -1 SD | ||

| Regular | 2.140*** (0.619) [0.927, 3.353] |

-0.233 (0.810) [-1.821, 1.356] |

| Low carb | 1.991*** (0.637) [0.742, 3.240] |

6.212*** (0.825) [4.596, 7.829] |

| High carb | 1.459** (0.630) [0.225, 2.694] |

2.373*** (0.788) [0.827, 3.918] |

| Health orientation = Mean (0, centered) | ||

| Regular | 3.346*** (0.583) [2.204, 4.487] |

0.973 (0.630) [-0.262, 2.209] |

| Low carb | 3.197*** (0.610) [2.001, 4.393] |

7.418*** (0.682) [6.082, 8.754] |

| High carb | 2.665*** (0.589) [1.511, 3.819] |

3.579*** (0.616) [2.372, 4.785] |

| Health orientation = +1 SD | ||

| Regular | 4.552*** (0.763) [3.056, 6.048] |

2.179*** (0.652) [0.902, 3.457] |

| Low carb | 4.403*** (0.791) [2.852, 5.954] |

8.624*** (0.732) [7.189, 10.059] |

| High carb | 3.871*** (0.764) [2.375, 5.368] |

4.785*** (0.651) [3.509, 6.060] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).