Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Security-Integrated Software Development

1.2. Rise of Vulnerability-Driven Software Failures

1.3. Need for Automated Quality Assurance in CI/CD Pipelines

2. Literature Survey

| Aspect | Static Code Analysis | Dynamic Code Analysis |

| Timing of Analysis | Performed without code execution | Performed during runtime execution |

| Scope | Examines entire codebase structure | Focuses on executed code paths and runtime behavior |

| Types of Issues Detected | Syntax errors, security vulnerabilities, coding standards violations | Memory leaks, performance bottlenecks, runtime errors |

| Automation | Highly automated with tools scanning source code | Partial automation; requires runtime monitoring |

| Resource Requirements | Lower computational overhead | Higher resource consumption due to execution |

| Early Feedback to Developers | Provides early identification of issues | Finds issues observable only during execution |

| Limitations | Cannot detect runtime-specific issues | Limited to tested execution paths |

3. Overview of Code Analysis Techniques

3.1. Definition and Objectives

3.2. Differences Between Static and Dynamic Analysis

3.3. Role in Secure SDLC and DevSecOps Practices

4. Static Code Analysis for Early Vulnerability Detection

4.1. Source Code Parsing and Semantic Inspection

4.2. Rule-Based and Pattern-Based Vulnerability Identification

4.3. Preventing OWASP Top 10 & Logic Flaws via SAST

4.4. Integrating SCA (Software Composition Analysis) for Dependency Risks

5. Dynamic Code Analysis for Runtime Security Validation

5.1. Execution-Level Monitoring and Behavior Profiling

5.2. DAST Approaches for Web, Mobile, and Cloud Workloads

5.3. Vulnerability Exploit Simulation and Fuzz Testing

5.4. Memory Corruption, Leakage, and Runtime Integrity Checks

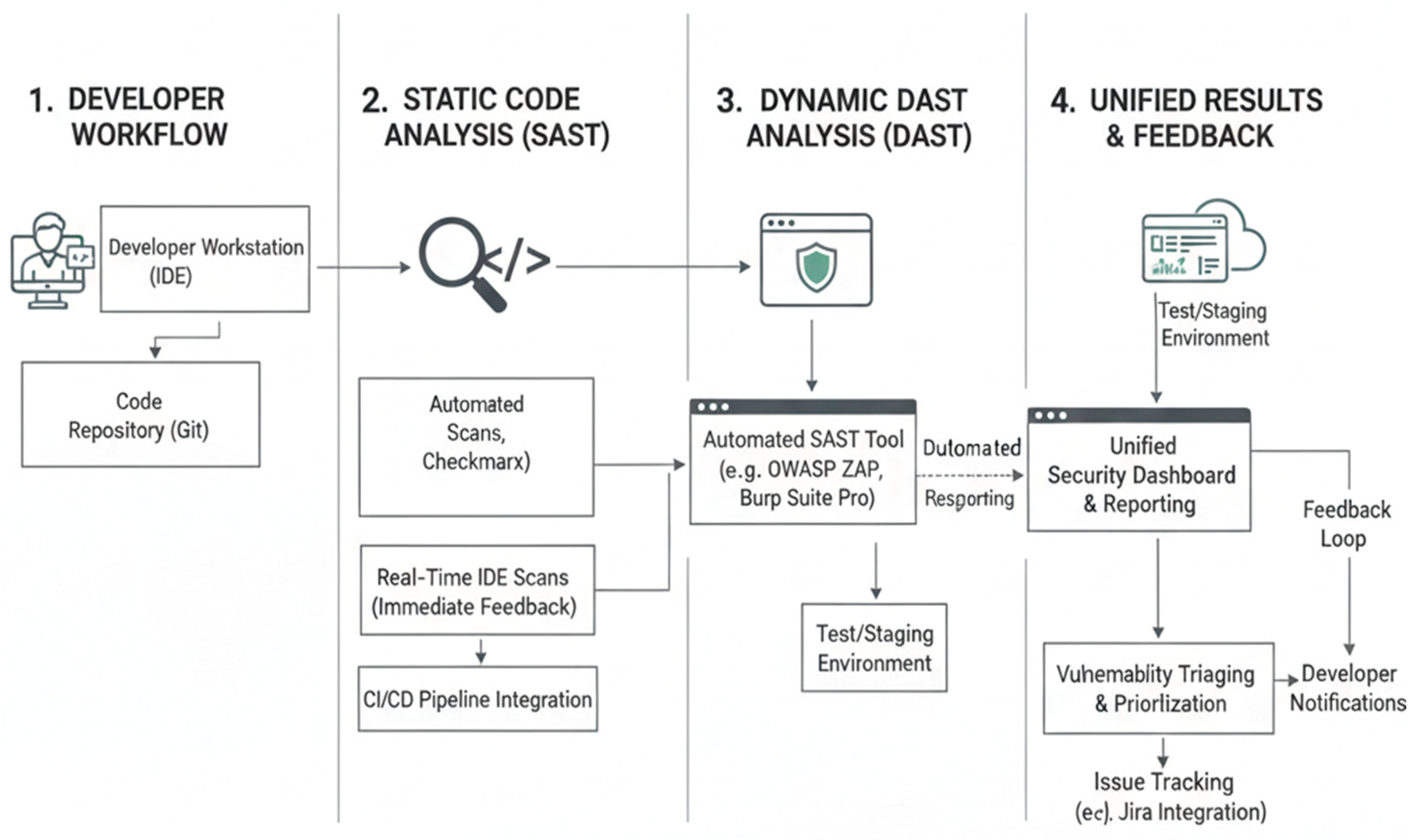

6. Automated Security Toolchains in Development Environments

6.1. Integration in IDEs (VS Code, IntelliJ, Eclipse)

6.2. Secure CI/CD Pipeline Automation (Jenkins, GitLab, GitHub Actions)

6.3. Policy-Driven Security Gates and Build Breakers

6.4. Version Control Integration and Pre-Commit Hooks

7. Frameworks and Tools Supporting Static & Dynamic Analysis

7.1. SAST Tools

7.2. DAST Tools

7.3. Hybrid Testing Systems and AI-Driven Scanning Tools

8. Use Cases and Case Studies

8.1. Enterprise CI Pipeline Security Integration

8.2. Secure Software Release Workflow in Cloud-Native Apps

8.3. Application Security in IoT and Embedded Systems

9. Quality Assurance and Performance Benefits

9.1. Reduction in Defect Density and Technical Debt

9.2. Improved Code Maintainability and Review Efficiency

9.3. Faster Release Cycles Through Early-Fix Initiatives

10. Challenges and Limitations

10.1. False Positives, False Negatives, and Tool Noise

10.2. Performance Overheads and Build Delays

10.3. Limited Support for Proprietary Frameworks and Legacy Systems

Conclusion and Future Enhancements

References

- Jayalakshmi, N., & Sakthivel, K. (2024, December). A Hybrid Approach for Automated GUI Testing Using Quasi-Oppositional Genetic Sparrow Search Algorithm. In 2024 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Sharma, A., Gurram, N. T., Rawal, R., Mamidi, P. L., & Gupta, A. S. G. (2025). Enhancing educational outcomes through cloud computing and data-driven management systems. Vascular and Endovascular Review, 8(11s), 429-435.

- Tatikonda, R., Thatikonda, R., Potluri, S. M., Thota, R., Kalluri, V. S., & Bhuvanesh, A. (2025, May). Data-Driven Store Design: Floor Visualization for Informed Decision Making. In 2025 International Conference in Advances in Power, Signal, and Information Technology (APSIT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Rajgopal, P. R. (2025). Secure Enterprise Browser-A Strategic Imperative for Modern Enterprises. International Journal of Computer Applications, 187(33), 53-66. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P. (2025). Sustainable manufacturing 4.0: Tracking carbon footprint in SAP digital manufacturing with IoT sensor networks. Frontiers in Emerging Computer Science and Information Technology, 2(09), 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, Z. (2025). Development of a simulator to mimic VMware vCloud Director (VCD) API calls for cloud orchestration testing. International Journal of Computational and Experimental Science and Engineering, 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., & Rajgopal, P. R. (2025). Cybersecurity platformization: Transforming enterprise security in an AI-driven, threat-evolving digital landscape. International Journal of Computer Applications, 186(80), 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Rajgopal, P. R. (2025). MDR service design: Building profitable 24/7 threat coverage for SMBs. International Journal of Applied Mathematics, 38(2s), 1114-1137. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Naveen, S., JR, M. D., Sukla, B., Choudhary, M. P., & Gupta, M. J. (2025). Emotional Intelligence And Spiritual Awareness: A Management-Based Framework To Enhance Well-Being In High-Stressed Surgical Environments. Vascular and Endovascular Review, 8(10s), 53-62.

- Atheeq, C., Sultana, R., Sabahath, S. A., & Mohammed, M. A. K. (2024). Advancing IoT Cybersecurity: adaptive threat identification with deep learning in Cyber-physical systems. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research, 14(2), 13559-13566. [CrossRef]

- Ainapure, B., Kulkarni, S., & Janarthanan, M. (2025, December). Performance Comparison of GAN-Augmented and Traditional CNN Models for Spinal Cord Tumor Detection. In Sustainable Global Societies Initiative (Vol. 1, No. 1). Vibrasphere Technologies.

- Ainapure, B., Kulkarni, S., & Chakkaravarthy, M. (2025). TriDx: a unified GAN-CNN-GenAI framework for accurate and accessible spinal metastases diagnosis. Engineering Research Express, 7(4), 045241. [CrossRef]

- Shanmuganathan, C., & Raviraj, P. (2011, September). A comparative analysis of demand assignment multiple access protocols for wireless ATM networks. In International Conference on Computational Science, Engineering and Information Technology (pp. 523-533). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Mulla, R., Potharaju, S., Tambe, S. N., Joshi, S., Kale, K., Bandishti, P., & Patre, R. (2025). Predicting Player Churn in the Gaming Industry: A Machine Learning Framework for Enhanced Retention Strategies. Journal of Current Science and Technology, 15(2), 103-103. [CrossRef]

- Shinkar, A. R., Joshi, D., Praveen, R. V. S., Rajesh, Y., & Singh, D. (2024, December). Intelligent solar energy harvesting and management in IoT nodes using deep self-organizing maps. In 2024 International Conference on Emerging Research in Computational Science (ICERCS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Ainapure, B., & Appasani, B. (2025). Machine Learning Algorithms and Sustainable AI-Driven IoT Systems: Paving the Way toward Environmental Stewardship. In Leveraging Artificial Intelligence in Cloud, Edge, Fog and Mobile Computing (pp. 217-234). Auerbach Publications.

- Raja, M. W., & Nirmala, D. K. (2016). Agile development methods for online training courses web application development. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN, 0973-4562.

- Vikram, V., & Soundararajan, A. S. (2021). Durability studies on the pozzolanic activity of residual sugar cane bagasse ash sisal fibre reinforced concrete with steel slag partially replacement of coarse aggregate. Caribb. J. Sci, 53, 326-344.

- Sayyed, Z. (2025). Application level scalable leader selection algorithm for distributed systems. International Journal of Computational and Experimental Science and Engineering, 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, S. V., Kumar, R., & Chow, S. (2023). U.S. Patent No. 11,727,327. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Siddiqui, A., Chand, K., & Shahi, N. C. (2021). Effect of process parameters on extraction of pectin from sweet lime peels. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series A, 102(2), 469-478. [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, S., Joshi, S. S., Sharma, S., Radhakrishnan, M., Krishna, K. M., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Additive manufacturing of FeCrAl alloys for nuclear applications-A focused review. Nuclear Materials and Energy, 40, 101702. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P. (2025). Global MES Rollout Strategies: Overcoming Localization Challenges in Multi-Country Deployments. Emerging Frontiers Library for The American Journal of Applied Sciences, 7(07), 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Content Based Medical Image Retrieval System Based On Multi Model Clustering Segmentation And Multi-Layer Perception Classification Methods. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(7).

- Kumar, N., Kurkute, S. L., Kalpana, V., Karuppannan, A., Praveen, R. V. S., & Mishra, S. (2024, August). Modelling and Evaluation of Li-ion Battery Performance Based on the Electric Vehicle Tiled Tests using Kalman Filter-GBDT Approach. In 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Algorithms for Computational Intelligence Systems (IACIS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Saravanan, V., Sumalatha, A., Reddy, D. N., Ahamed, B. S., & Udayakumar, K. (2024, October). Exploring Decentralized Identity Verification Systems Using Blockchain Technology: Opportunities and Challenges. In 2024 5th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Akat, G. B. (2022). OPTICAL AND ELECTRICAL STUDY OF SODIUM ZINC PHOSPHATE GLASS. MATERIAL SCIENCE, 21(05).

- Approximation of Coefficients Influencing Robot Design Using FFNN with Bayesian Regularized LMBPA.

- Naveen, S., & Sharma, P. (2025). Physician Well-Being and Burnout:" The Correlation Between Duty Hours, Work-Life Balance, And Clinical Outcomes In Vascular Surgery Trainees". Vascular and Endovascular Review, 8(6s), 389-395. [CrossRef]

- Rajgopal, P. R. (2025). SOC Talent Multiplication: AI Copilots as Force Multipliers in Short-Staffed Teams. International Journal of Computer Applications, 187(48), 46-62. [CrossRef]

- Atmakuri, A., Sahoo, A., Mohapatra, Y., Pallavi, M., Padhi, S., & Kiran, G. M. (2025). Securecloud: Enhancing protection with MFA and adaptive access cloud. In Advances in Electrical and Computer Technologies (pp. 147-152). CRC Press.

- Sharma, N., Gurram, N. T., Siddiqui, M. S., Soorya, D. A. M., Jindal, S., & Kalita, J. P. (2025). Hybrid Work Leadership: Balancing Productivity and Employee Well-being. Vascular and Endovascular Review, 8(11s), 417-424.

- Mahesh, K., & Balaji, D. P. (2022). A Study on Impact of Tamil Nadu Premier League Before and After in Tamil Nadu. International Journal of Physical Education Sports Management and Yogic Sciences, 12(1), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R., Ahmed, N., & Sattar, S. A. (2018). HADOOP based image compression and amassed approach for lossless images. Biomedical Research, 29(8), 1532-1542.

- Venkiteela, P. (2024). Strategic API modernization using Apigee X for enterprise transformation. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management.

- Kumar, J. D. S. (2015). Investigation on secondary memory management in wireless sensor network. Int J Comput Eng Res Trends, 2(6), 387-391.

- Lopez, S., Sarada, V., Praveen, R. V. S., Pandey, A., Khuntia, M., & Haralayya, D. B. (2024). Artificial intelligence challenges and role for sustainable education in india: Problems and prospects. Sandeep Lopez, Vani Sarada, RVS Praveen, Anita Pandey, Monalisa Khuntia, Bhadrappa Haralayya (2024) Artificial Intelligence Challenges and Role for Sustainable Education in India: Problems and Prospects. Library Progress International, 44(3), 18261-18271.

- Joshi, S., & Kumar, A. (2020). Multimodal biometrics system design using score level fusion approach. Int. J. Emerg. Technol, 11(3), 1005-1014.

- Thota, R., Potluri, S. M., Kaki, B., & Abbas, H. M. (2025, June). Financial Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers with Temporal Fusion Transformer for Predicting Financial Market Trends. In 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Knowledge Extraction (ICICKE) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Dachawar, M., Ainapure, B., Tong, V., & Hegde, M. (2025, August). The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence Enhanced Enterprise Resource Planning in Higher Education: A Comprehensive Meta-Data Analysis. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS) (pp. 1574-1582). IEEE.

- ROBERTS, T. U., Polleri, A., Kumar, R., Chacko, R. J., Stanesby, J., & Yordy, K. (2022). U.S. Patent No. 11,321,614. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Kumar, J., Radhakrishnan, M., Palaniappan, S., Krishna, K. M., Biswas, K., Srinivasan, S. G., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Cr content dependent lattice distortion and solid solution strengthening in additively manufactured CoFeNiCrx complex concentrated alloys–a first principles approach. Materials Today Communications, 40, 109485. [CrossRef]

- Parasar, D., & Rathod, V. R. (2017). Particle swarm optimisation K-means clustering segmentation of foetus ultrasound image. International Journal of Signal and Imaging Systems Engineering, 10(1-2), 95-103.

- Venkiteela, P. (2025). Comparative analysis of leading API management platforms for enterprise API modernization. International Journal of Computer Applications. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R., Bilfagih, S. M., & Sabahath, S. A. (2021). A Novel Machine Learning system to control Denial-of-Services Attacks. Design Engineering, 3676-3683.

- Praveen, R. V. S., Hemavathi, U., Sathya, R., Siddiq, A. A., Sanjay, M. G., & Gowdish, S. (2024, October). AI Powered Plant Identification and Plant Disease Classification System. In 2024 4th International Conference on Sustainable Expert Systems (ICSES) (pp. 1610-1616). IEEE.

- Appaji, I., & Raviraj, P. (2020, February). Vehicular Monitoring Using RFID. In International Conference on Automation, Signal Processing, Instrumentation and Control (pp. 341-350). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Nimma, D., Rao, P. L., Ramesh, J. V. N., Dahan, F., Reddy, D. N., Selvakumar, V., ... & Jangir, P. (2025). Reinforcement Learning-Based Integrated Risk Aware Dynamic Treatment Strategy for Consumer-Centric Next-Gen Healthcare. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M. W. (2024). Artificial intelligence-based healthcare data analysis using multi-perceptron neural network (MPNN) based on optimal feature selection. SN Computer Science, 5(8), 1034. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D., Mani, S., Sinha, V. S., Ananthanarayanan, R., Srivastava, B., Dhoolia, P., & Chowdhury, P. (2010, July). AHA: Asset harvester assistant. In 2010 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (pp. 425-432). IEEE.

- Patil, P. R., Parasar, D., & Charhate, S. (2024). Wrapper-based feature selection and optimization-enabled hybrid deep learning framework for stock market prediction. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, 23(01), 475-500. [CrossRef]

- Zahir, S. (2025). Custom Email Template Creation Using Mustache for Scalable Communication. International journal of signal processing, embedded systems and VLSI design, 5(01), 35-61. [CrossRef]

- Naveen, S., Sharma, P., Veena, A., & Ramaprabha, D. (2025). Digital HR Tools and AI Integration for Corporate Management: Transforming Employee Experience. In Corporate Management in the Digital Age (pp. 69-100). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

- Satheesh, N., & Sakthivel, K. (2024, December). A Novel Machine Learning-Enhanced Swarm Intelligence Algorithm for Cost-Effective Cloud Load Balancing. In 2024 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Radhakrishnan, M., Sharma, S., Palaniappan, S., Pantawane, M. V., Banerjee, R., Joshi, S. S., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Influence of thermal conductivity on evolution of grain morphology during laser-based directed energy deposition of CoCrxFeNi high entropy alloys. Additive Manufacturing, 92, 104387. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A. K., Prusty, S., Swain, A. K., & Jayasingh, S. K. (2025). Revolutionizing cancer diagnosis using machine learning techniques. In Intelligent Computing Techniques and Applications (pp. 47-52). CRC Press.

- Praveen, R. V. S. (2024). Data Engineering for Modern Applications. Addition Publishing House.

- Nimavat, K. K., & Kumar, R. (2025). U.S. Patent No. 12,260,303. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Sahoo, P. A. K., Aparna, R. A., Dehury, P. K., & Antaryami, E. (2024). Computational techniques for cancer detection and risk evaluation. Industrial Engineering, 53(3), 50-58.

- Gurram, N. T., Narender, M., Bhardwaj, S., & Kalita, J. P. (2025). A Hybrid Framework for Smart Educational Governance Using AI, Blockchain, and Data-Driven Management Systems. Advances in Consumer Research, 2(5).

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Multi Model Clustering Segmentation and Intensive Pragmatic Blossoms (Ipb) Classification Method based Medical Image Retrieval System. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(3), 7841-7852.

- Juneja, M., & Juneja, P. (2025). The Rise of The Tech-Business Translator in The Age Of AI. International Research Journal of Advanced Engineering and Technology, 2(06), 05-15.

- Jadhav, Y., Patil, V., & Parasar, D. (2020, February). Machine learning approach to classify birds on the basis of their sound. In 2020 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT) (pp. 69-73). IEEE.

- Suman, P., Parasar, D., & Rathod, V. R. (2015, December). Seeded region growing segmentation on ultrasound image using particle swarm optimization. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Akat, G. B. (2021). EFFECT OF ATOMIC NUMBER AND MASS ATTENUATION COEFFICIENT IN Ni-Mn FERRITE SYSTEM. MATERIAL SCIENCE, 20(06).

- Boopathy, D., & Balaji, P. (2023). Effect of different plyometric training volume on selected motor fitness components and performance enhancement of soccer players. Ovidius University Annals, Series Physical Education and Sport/Science, Movement and Health, 23(2), 146-154.

- Venkiteela, P. (2025). Real-Time Identity Federation: Replacing File-Based Sync with Okta APIs for GDPR-Compliant. European Journal of Information Technologies and Computer Science, 5(5), 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S., & Kumar, A. (2011). Correlation Filter based on Fingerprint Verification System. In International Conference on VLSI, Communication and Instrumentation (pp. 19-22).

- Ganeshan, M. K., & Vethirajan, C. (2021). Trends and future of human resource management in the 21st century. Review of Management, Accounting, and Business Studies, 2(1), 17-21. [CrossRef]

- Samal, D. A., Sharma, P., Naveen, S., Kumar, K., Kotehal, P. U., & Thirulogasundaram, V. P. (2024). Exploring the role of HR analytics in enhancing talent acquisition strategies. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, 23(3), 612-618. [CrossRef]

- Kamatchi, S., Preethi, S., Kumar, K. S., Reddy, D. N., & Karthick, S. (2025, May). Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm Optimised Convolutional Neural Networks for Improved Pancreatic Cancer Detection. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Gupta, I. A. K. Blockchain-Based Supply Chain Optimization For Eco-Entrepreneurs: Enhancing Transparency And Carbon Footprint Accountability. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 11(17s), 2025.

- Praveen, R. V. S., Hundekari, S., Parida, P., Mittal, T., Sehgal, A., & Bhavana, M. (2025, February). Autonomous Vehicle Navigation Systems: Machine Learning for Real-Time Traffic Prediction. In 2025 International Conference on Computational, Communication and Information Technology (ICCCIT) (pp. 809-813). IEEE.

- Mohammed Nabi Anwarbasha, G. T., Chakrabarti, A., Bahrami, A., Venkatesan, V., Vikram, A. S. V., Subramanian, J., & Mahesh, V. (2023). Efficient finite element approach to four-variable power-law functionally graded plates. Buildings, 13(10), 2577. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, M. (2025). Mentr: A Modular, On Demand Mentorship Platform for Personalized Learning and Guidance. The American Journal of Engineering and Technology, 7(06), 144-152. [CrossRef]

- Polleri, A., Kumar, R., Bron, M. M., Chen, G., Agrawal, S., & Buchheim, R. S. (2022). U.S. Patent Application No. 17/303,918.

- Sayyed, Z. (2025). Optimizing Callback Service Architecture for High-Throughput Applications. International journal of data science and machine learning, 5(01), 257-279. [CrossRef]

- Vidyabharathi, D., Mohanraj, V., Kumar, J. S., & Suresh, Y. (2023). Achieving generalization of deep learning models in a quick way by adapting T-HTR learning rate scheduler. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 27(3), 1335-1353. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, M., Sharma, S., Palaniappan, S., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Evolution of microstructures in laser additive manufactured HT-9 ferritic martensitic steel. Materials Characterization, 218, 114551. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P. (2025). GENERATIVE AI FOR MES OPTIMIZATION LLM-DRIVEN DIGITAL MANUFACTURING CONFIGURATION RECOMMENDATION. International Journal of Applied Mathematics, 38(7s), 875-890. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, G., Chand, K., Azaz Ahmad Azad, Z. R., & Nazir, S. (2020). Optimization of Finger Millet and Carrot Pomace based fiber enriched biscuits using response surface methodology. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 57(12), 4613-4626. [CrossRef]

- Akat, G. B., & Magare, B. K. (2022). Mixed Ligand Complex Formation of Copper (II) with Some Amino Acids and Metoprolol. Asian Journal of Organic & Medicinal Chemistry.

- Thota, R., Potluri, S. M., Alzaidy, A. H. S., & Bhuvaneshwari, P. (2025, June). Knowledge Graph Construction-Based Semantic Web Application for Ontology Development. In 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Knowledge Extraction (ICICKE) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- RAJA, M. W., PUSHPAVALLI, D. M., BALAMURUGAN, D. M., & SARANYA, K. (2025). ENHANCED MED-CHAIN SECURITY FOR PROTECTING DIABETIC HEALTHCARE DATA IN DECENTRALIZED HEALTHCARE ENVIRONMENT BASED ON ADVANCED CRYPTO AUTHENTICATION POLICY. TPM–Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 32(S4 (2025): Posted 17 July), 241-255.

- Venkiteela, P. (2025). A Vendor-Agnostic Multi-Cloud Integration Framework Using Boomi and SAP BTP. Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences, 4(12), 1-14.

- Akat, G. B. (2023). Structural Analysis of Ni1-xZnxFe2O4 Ferrite System. MATERIAL SCIENCE, 22(05).

- Sivakumar, S., Prakash, R., Srividhya, S., & Vikram, A. V. (2023). A novel analytical evaluation of the laboratory-measured mechanical properties of lightweight concrete. Structural engineering and mechanics: An international journal, 87(3), 221-229.

- Inbaraj, R., John, Y. M., Murugan, K., & Vijayalakshmi, V. (2025). Enhancing medical image classification with cross-dimensional transfer learning using deep learning. 1, 10(4), 389.

- Chand, K., Singh, A., & Kulshrestha, M. (2012). Jaggery quality effected by hilly climatic conditions. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 11(1), 172-176.

- ROBERTS, T. U., Polleri, A., Kumar, R., Chacko, R. J., Stanesby, J., & Yordy, K. (2023). U.S. Patent No. 11,775,843. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Reddy, D. N., Venkateswararao, P., Vani, M. S., Pranathi, V., & Patil, A. (2025). HybridPPI: A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (IJEEI), 13(2).

- Balakumar, B., & Raviraj, P. (2015). Automated Detection of Gray Matter in Mri Brain Tumor Segmentation and Deep Brain Structures Based Segmentation Methodology. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 23(6), 1023-1029.

- Praveen, R. V. S., Raju, A., Anjana, P., & Shibi, B. (2024, October). IoT and ML for Real-Time Vehicle Accident Detection Using Adaptive Random Forest. In 2024 Global Conference on Communications and Information Technologies (GCCIT) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).