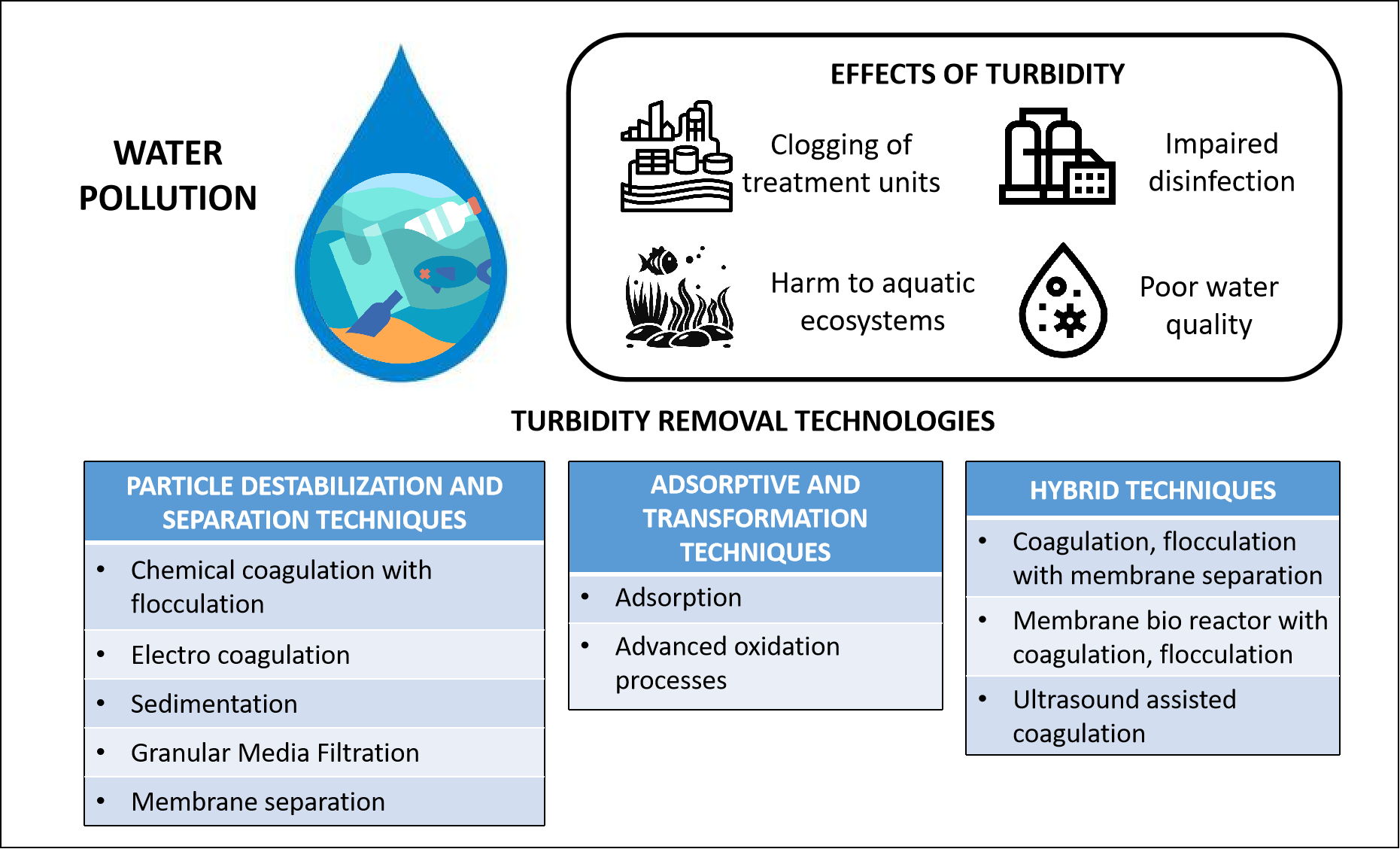

1. Introduction

Water pollution has become a defining environmental challenge at the global scale, demonstrably detrimental to human health, wildlife, and entire ecosystems [

1]. Consequently, the potability and utility of numerous global water resources that sustain human, animal, and plant life are experiencing accelerated degradation. A fundamental water quality metric is turbidity, which quantifies the deterioration of water clarity, mainly resulting from suspended constituents, notably clay, silt, organic matter, and various microorganisms. [

2]. These particulate materials can enter aquatic systems via point and non-point pollution sources such as wastewater discharge, agricultural runoff, storm water flows, and industrial effluents, possessing the capacity to either absorb or scatter incident light [

3,

4]. Thus, turbidity is determined by measuring the magnitude of light scattering produced when an electromagnetic beam is transmitted through water containing suspended matter. The extent of scattering of light is contingent upon the size, morphological characteristics, and chemical composition of the suspended particles, serving as an indicator of the water's relative clarity [

5].

Turbidity measurements are conventionally expressed in Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) [

6]. Increased water turbidity can give rise to multiple harmful consequences. Turbidity-inducing particles can impede disinfection operations in water and wastewater treatment systems by shielding pathogens entailing for higher chemical dosages thereby increasing the risk of harmful byproduct formation and also cause health risks to consumers [

7]. Should these particles remain unremoved, they can infiltrate water distribution networks across residential and industrial areas, facilitating the spread of waterborne diseases. Elevated turbidity levels can limit photosynthesis in aquatic eco systems reducing oxygen availability [

8]. During extreme weather conditions such as floods, there can be sudden spikes in turbidity which can overwhelm treatment plants even causing them to shutdown [

9]. Moreover, the discernible presence of opacity in potable water sources can precipitate consumer apprehension and foster skepticism concerning its safety and perceived quality.

Consequently, reducing water turbidity has become a primary goal in water and wastewater treatment. Achieving this objective ensures the supply of safe and visually acceptable drinking water, supports diverse industrial uses, and plays a critical role in protecting the environment. In order to provide safe drinking water to the consumer, various legislations have been introduced across the globe, specifying the maximum turbidity levels to be maintained. The table below (

Table 1) represents maximum admissible turbidity limits which can be seen in certain areas around the world.

There are various treatment techniques both conventional and modern, which are used to remove turbidity directly or indirectly. Conventional treatment methodologies adhere to established protocols, have been extensively investigated, and possess a long-standing history of widespread global application. Conversely, contemporary treatment techniques remain in a state of evolution, developing in tandem with ongoing technological advancements.

Existing reviews of turbidity removal tend to focus on individual technologies or consider conventional and emerging methods in isolation, limiting integrated understanding across treatment approaches. To address this gap, the present review introduces a mechanism-based framework for the classification of turbidity control techniques, encompassing both conventional and emerging methods. For each category, the underlying operational principles and governing mechanisms, turbidity removal efficiency ranges supported by case studies, as well as key merits and limitations, are critically examined.

Table 2 outlines the proposed classification framework and the turbidity control techniques discussed in this review. It should be noted that some treatment techniques are not primary turbidity removal processes, but rather downstream technologies; therefore, they are discussed primarily within the context of integrated hybrid treatment trains, where effective upstream pre treatment is essential to ensure sustainable turbidity control and membrane performance.

A critical parameter which governs the efficiency pf the techniques categorized in

Table 2 is the Zero Point Charge (ZPC). ZPC is the pH in which the net electrical charge of a surface of the particle is exactly zero. Turbidity inducing impurities such as clay, silt, natural organic matter, etc usually carry negative surface charges, naturally repelling each other which allows them to remain stable and suspended in water/ wastewater.

Table 3 summarizes the mechanism based category and the relevant role of the ZPC.

2. Particle Destabilization, Aggregation and Separation Techniques

2.1. Chemical Coagulation and Flocculation

Chemical coagulation with flocculation represent a prevalent physicochemical mechanism utilized within conventional water and wastewater treatment frameworks to destabilize and aggregate suspended colloids allowing the removal of the fine suspended particles. This technique mainly consists of two sequential steps.

1) Coagulation entails the rapid (flash) mixing of water with chemical coagulants, which serve to destabilize particles which are negatively charged, including silt, clay, and other turbidity-inducing constituents. Within conventional coagulant options, inorganic salts—including ferric sulfate, aluminum sulfate (alum), and ferric chloride—are frequently utilized, with their efficacy predominantly governed by water pH and coagulant dosage. The positively charged ions which are produced by the coagulant (e.g: Al

3+) neutralizes the electro repulsive forces between the colloidal matter allowing the formation of micro flocs [

15].

2) Following the coagulation stage, flocculation entails the gentle agitation of the medium to facilitate the collision and aggregation of micro-flocs into larger, more stable masses, thereby enhancing their removal via sedimentation and/or filtration. To optimize this mechanism, flocculants—predominantly organic polymers—are administered, which demonstrate high efficacy even at significantly reduced concentrations [

16].

The flash mixing stage of coagulation involves vigorous agitation over a very short period—usually less than one minute—requiring careful selection of appropriate motors and impellers to guarantee sufficient homogenization while circumventing mechanical constraints [

17]. Flocculation requires gentle agitation in order for the proper formation of larger flocs to occur. Apart from pH and coagulant dosage, other factors such as temperature, mixing condition and other ions present in the water may also affect the turbidity removal efficiency in this method [

18]. Therefore, as this process is sensitive to the pH levels in the water it requires constant adjusting of chemical dosages during the course of treatment. A study, which included the participation of one of the authors, was executed to evaluate the potential for mitigating costs stemming from the high price of commercial coagulants when comparing their efficacy with the locally available natural options. The results indicated that, while natural coagulants typically exhibit lower efficiency relative to their commercial counterparts, they demonstrated the capacity to achieve turbidity reduction levels of up to 82% [

19]. Another study which was conducted using different type of coagulants to remove turbidity revealed that this technique has the ability to remove turbidity from 77% to nearly 99% [

20]. This can lead to reduction in loading on downstream treatment units such as filtration. Although a well established method, coagulation with flocculation generates a considerable quantity of sludge containing metal salts, which is typically non regenerable and requires significant energy for dewatering and disposal.

Overall, chemical coagulation and flocculation remains a fundamental and highly effective method for turbidity reduction, though its performance is influenced by raw water characteristics, chemical and energy requirements and the need for appropriate sludge management.

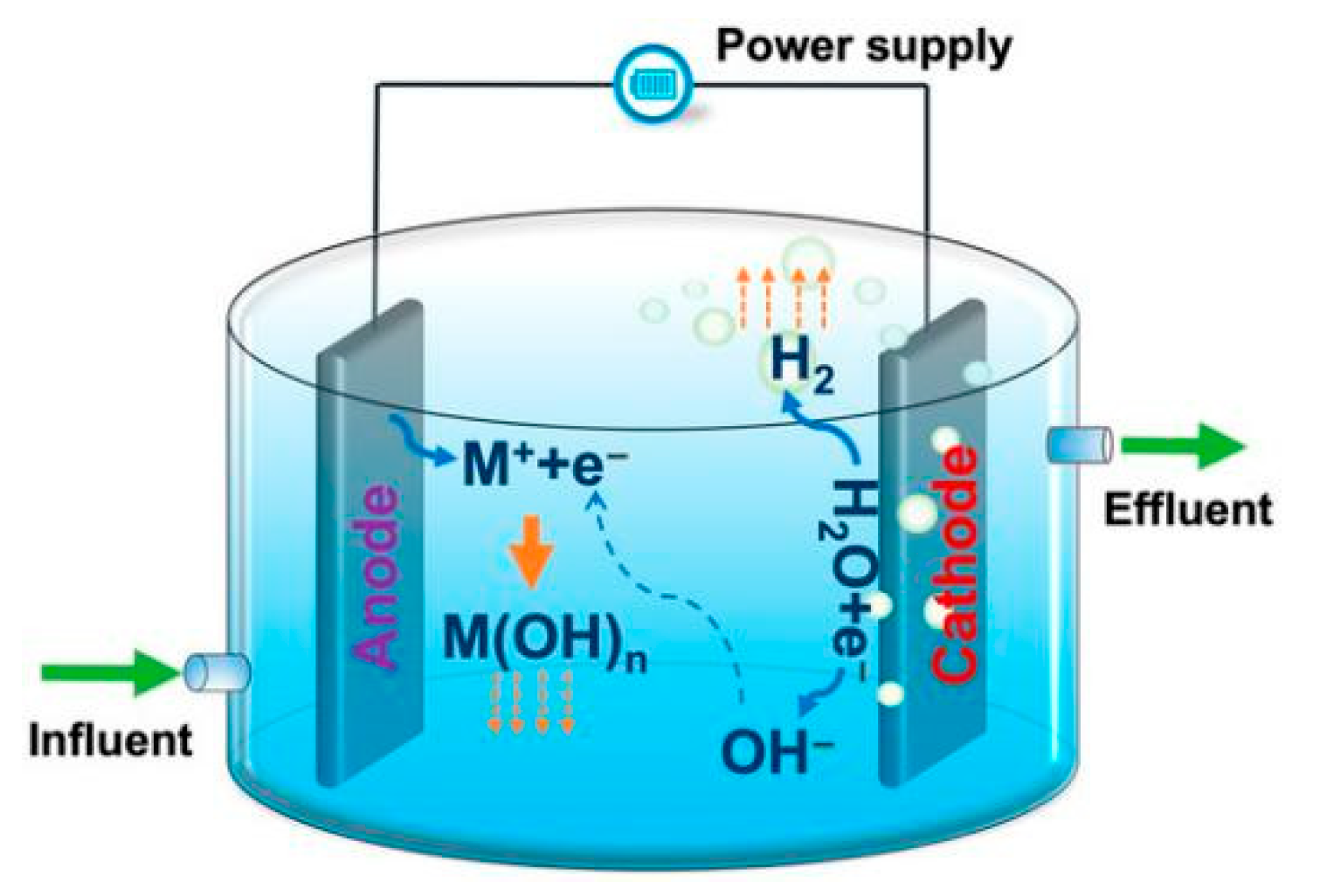

2.2. Electro Coagulation

Electrocoagulation (EC) is recognized as an advanced treatment option that replaces conventional coagulation and flocculation methodologies frequently employed in water and wastewater treatment. During electrochemical treatment, an imposed electric current induces the dissolution of sacrificial electrodes, generating metal ions such as iron or aluminum. In this process, the anode undergoes oxidative dissolution to release metal cations, while reduction at the cathode produces hydrogen gas along with hydroxide ions [

21].

Following their release, metal ions combine with hydroxide ions to generate metal hydroxides that serve as the dominant coagulating agents. Consistent with the mechanisms of chemical coagulation, this leads to the destabilization of colloidal particles and the subsequent formation of flocs. These aggregates are then effectively sequestered through flotation, sedimentation, or filtration [

22,

23]. The schematic representation in

Figure 1 elucidates the comprehensive electrocoagulation process utilizing generic metal (M) electrodes [

24].

Thus, the electrolysis process involves the following reactions [

24];

The sacrificial metal anode dissolves under the applied electric current, releasing metal cations into the aqueous phase (equation (1)):

At the cathode, water is reduced, producing hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions (which occurs simultaneously with the anode process) which is shown in equation (2):

Equations (3) and (4) depict the reactions between metal cations and hydroxide ions that lead to monomeric and polymeric species formation respectively:

The performance and operational efficiency of the electrocoagulation (EC) process are significantly influenced by a multitude of variables. The most critical parameters are the electrode material, the applied voltage/current that govern anodic dissolution, and the length of the electrolysis process. Generally, an increase in electrolysis time correlates with enhanced removal efficiencies. Furthermore, the initial aqueous pH serves as a critical determinant on the effectiveness of the the overall process. The inter-electrode distance also plays a vital role, influencing the electric field intensity and thereby affecting the overall efficiency of the EC process. Consequently, the optimization of these operational parameters is imperative for maximizing the removal of turbidity and associated contaminants [

25,

26,

27].

Electrocoagulation (EC) has garnered significant academic interest as a viable methodology for water and wastewater remediation, prompting extensive investigation into various water quality parameters—most notably turbidity, which has been frequently examined under diverse operational conditions. Rahmani (2008) documented that aluminum electrodes achieved a 93% turbidity reduction at 20 V with a 20-minute electrolysis duration, a performance that surpassed both iron and stainless steel variants [

28]. Furthermore, Kobaya et al. (2013) demonstrated that escalating current density facilitated an increase in turbidity removal efficiency from 56% to 98% within wastewater from potato chip manufacturing [

29]. In a comparable study, Zailani et al. (2017) highlighted current density as the most significant operational parameter in the EC-based treatment of leachate, while Shivayogimath et al. (2013) attained an approximate turbidity removal of 97% under optimized conditions, specifically at 9 V and pH 5.8 over a 35-minute electrolysis period [

27,

30]. Sadeddin et al. (2010) further established that through the optimization of current density and electrolysis duration, turbidity removal efficiencies exceeding 98% could be achieved in Reverse Osmosis feed water [

31]. In a study assessing EC for the treatment of produced water, an initial turbidity reduction from 160 NTU to 70 NTU (representing a 44% decrease) was observed, which subsequently exceeded 99% when integrated with centrifugation [

32]. Further, Behara et al. (2023) applied electrocoagulation for the treatment of oil-contaminated wastewater, utilizing both Box–Behnken and Central Composite Design RSM methodologies. Through optimization of pH, initial oil concentration, density of current, and electrolysis time, the Box–Behnken Design (BBD) and Central Composite Design (CCD) achieved removal efficiencies of 80% and 93%, respectively, under optimal conditions [

33]. Despite its proven efficacy, the application of EC in potable water treatment has largely been restricted to small-scale or mobile units, primarily due to operational challenges concerning electrode management and high energy requirements [

34].

In summary, electrocoagulation (EC) has undergone extensive investigation and exhibits substantial potential as a robust and efficacious methodology for turbidity remediation. Primary advantages of this technique include the in situ generation of coagulants and its versatile applicability across a diverse spectrum of aqueous matrices [

35,

36]. Furthermore, EC typically yields reduced sludge volumes (which are usually removed by sedimentation or flotation) relative to conventional chemical coagulation and flocculation processes. Nevertheless, the requirement for sludge disposal remains a persistent challenge and a notable disadvantage of the method [

37]. Additional constraints associated with the implementation of EC include elevated energy consumption, particularly in the treatment of high-conductivity water or during prolonged processing intervals [

38]. Furthermore, the progressive dissolution of electrodes and the development of surface scaling necessitate periodic component replacement, thereby increasing maintenance requirements [

39].

While laboratory-scale execution is comparatively uncomplicated, transitioning to industrial-scale applications may encounter significant technical and economical barriers. Thus additional research is necessary to facilitate dependable large-scale deployment, ensuring sustained operational stability and economical feasibility under variable practical conditions.

2.3. Sedimentation

Typically implemented after coagulation with flocculation, sedimentation is one of the most established and widely used techniques for separating turbidity-causing substances from water. This is not frequently used as a direct method to control turbidity.During this process, denser particles settle under gravity in a quiescent tank or basin, resulting in the accumulation of sludge at the base which will be removed by a suitable mechanism and disposed safely.

It has been found that when preceded by effective coagulation–flocculation, conventional sedimentation can achieve moderate to very high turbidity removal efficiencies ranging from 50% to 90%. However, these efficiencies depend heavily on operational parameters such as initial sludge concentration, hydraulic retention time, and inlet velocity. One example is a study conducted to evaluate the performance of a high-rate lab-scale sedimentation tank treating drinking water with an initial turbidity of 100 NTU. At a constant inlet velocity of 3 mm/s, turbidity removal was measured with and without settling plates, resulting in efficiencies of 71% and 56%, respectively. In the same tank with settling plates, when the influent velocity was increased, turbidity removal decreased from 85% to 71% [

40]. In another case, a modified settling tank with rotating biological disks used to treat polluted surface water at a hydraulic retention time of 2 hours achieved turbidity removal ranging from 68.5% to 78.8%. Yuan et al. (2025) reported similar removal rates for lightly polluted urban rivers with seasonally high turbidity, ranging from 64.07% to 90% [

41,

42]. In contrast, using sedimentation alone without coagulation and flocculation typically produces turbidity removal rates of less than 20% [

43].

Sedimentation is conventionally employed for the sequestration of suspended and settleable solids; however, its efficacy is limited regarding finer particulate matter, which resists gravity-driven settling and remains in suspension for protracted durations [

44,

45]. Remaining fine particulates are typically addressed through follow-up operations such as filtration and disinfection, which are routinely employed in large-scale water treatment and storage systems [

46]. While sedimentation facilitates water purification, the reduction of chemical concentrations, and the mitigation of turbidity at a comparatively low operational cost, the sedimentation rate remains a pivotal determinant of process efficiency. The settling rate depends on various physical factors, including particle size and shape, the solid-phase density, and the dynamic viscosity of the water [

47].

2.4. Granular Media Filtration

Although granular media filtration (GMF) was first introduced in 1854 at the Chelsea Water Works in London using sand as the filter medium, it was subsequently combined with disinfection as part of a multi-barrier approach for pathogen removal. This integrated treatment philosophy underpinned UK government regulation for public drinking water supplies and subsequently spread to Europe and the United States, where it has been practiced for more than a century and is now applied worldwide.

With advances in research and filter media development, GMF employing alternative media has become a core component of conventional drinking water treatment trains globally, including in the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, Australia, and France. It is routinely implemented as rapid sand filtration (RSF) following coagulation and sedimentation to remove suspended solids and reduce turbidity [

48]. Nearly 80 % of London’s public water supply is derived from surface water, mainly from the River Thames and the River Lee, with the remainder (~20 %) coming from groundwater sources. All surface-derived raw water is treated through GMF processes. To manage the ever-increasing water demand and address water quality challenges such as turbidity and emerging contaminants, Thames Water typically passes all surface-derived raw water first through RSFs and then through SSFs in series as part of its multi-stage surface water treatment process [

49].

Conventional water treatment processes primarily utilize two sand filtration approaches: rapid sand filtration (RSF) and slow sand filtration (SSF). These methodologies exhibit significant divergence regarding their fundamental operational principles, hydraulic loading rates, and maintenance protocols with regard to cleaning the filters. SSF function at substantially lower flow velocities and utilize a biologically active stratum, termed the schmutzdecke layer, which develops on the sand bed surface to facilitate decontamination [

50]. Notably, the application of pre treatment stages such as coagulation and flocculation is discouraged for the influent of slow sand filters; unsettled flocs may lead to the premature clogging of the sand interstices, thereby compromising overall filtration performance.

It is recommended that this method to be used for water with turbidity less than 5 NTU in order to prevent the clogging issues [

51]. Based on the authors’ operational experience, slow sand filters (SSFs) can tolerate raw water turbidities of up to approximately 25 NTU for periods of 2–3 weeks when operated at a filtration rate of 0.2 m/h. Slow sand filtration can demonstrate high turbidity removal efficiency, often exceeding 97%, depending on the characteristics and turbidity of the raw water [

52]. Fitriani et al., (2023) modified an SSF and examined the turbidity removal in an effort to achieve clean water in disaster areas in Indonesia and achieved an efficiency of 82% [

53]. Maintenance of these filters typically involves the draining of the supernatant water level in a sand filter bed and mechanical scraping of the upper sand layer. However, an innovative initiative by Thames Water (UK), in collaboration with several partner water companies and universities, has embarked on a novel approach to clean slow sand filter beds using underwater robotics without draining the supernatant water. The project, known as the SandSCAPE (Science and Novel Devices for Sustainable Cleaning and Productivity Enhancement) project, commenced following its funding award in May 2025 and is expected to be completed by October 2028 [

54].

Conversely, rapid sand filters (RSF) need pre treatment and are mostly used in conventional water treatment plants which is highly efficient in removing turbidity. This type of sand filters function by removing suspended particles are removed not only at the surface but progressively throughout the entire depth of the filter medium, operating at higher filtration rates, hence RSFs are sometimes referred to as deep bed filters [

55]. As such, these filters need to be cleaned by back washing [

56]. Additional improvements in rapid sand filter performance can be achieved by implementing capping. This process consists of introducing capping materials, such as anthracite coal, PVC granules, or fragmented bricks, into the upper few centimeters of the sand layer. In a pilot scale study, Anthracite coal has been found to be more efficient in removing turbidity [

57]. Studies show by utilizing RSFs, turbidity removal efficiencies ranging from nearly 95% to 99% with pre treatment [

58]. As an example, in a study done to find the effects of filtration velocity in conjunction with initial head loss in an RSF for ground water treatment, a turbidity remove efficiency of 95% was seen while in another study following sedimentation, RSFs has demonstrated a turbidity removal efficiency of 98% [

59,

60].

In both SSF and RSF methodologies, systems may utilize a singular media type (mono-media) or a stratified arrangement of diverse media, referred to as multimedia filters. This configuration incorporates successive layers of filtration media with reducing particle sizes in the direction of flow, each tailored to retain particular fractions of suspended matter [

61]. A typical example of this configuration is roughing filtration. In particular, Pebble Matrix Filtration (PMF) represents a specialized roughing filtration technique developed as a pre treatment step to reduce elevated turbidity ahead of SSF. The system is composed of a matrix of natural pebbles with an average diameter of approximately 50 mm, while the interstitial voids in the lower section are filled with finer media, typically sand with particle sizes below 1 mm. Empirical findings indicate that turbidity removal efficiency can exceed 95% when PMF is integrated as a pretreatment for SSF [

62]. Multimedia filters demonstrate efficacy across a wide spectrum of turbidity concentrations. Layer composition and arrangement may be strategically optimized to suit the particular attributes of the influent water [

44]. Frequently utilized media include gravel, charcoal, sand and anthracite coal. Extensive research has been conducted to compare the turbidity reduction performance of these materials. For instance, in a study by Nkwonta et al. (2010), the comparative effectiveness of gravel and charcoal was assessed, with results indicating that charcoal outperformed gravel. The superior efficacy can be largely ascribed to the increased higher surface area per unit mass (specific surface area) and porosity of charcoal relative to gravel, facilitating auxiliary processes such as adsorption [

63]. For sustained optimal performance, complete filter media replacement is typically recommended after a period of 4–5 years [

64]. Despite the growth of advanced membrane technologies, the development of novel filter media for granular media filtration remains of strong interest to water utilities and government water providers, driven by greater raw water variability, stricter regulatory requirements, operational cost pressures, and sustainability objectives [

65].

Notwithstanding the status of filtration as a well-established technology in water and wastewater treatment, significant potential exists for further research to enhance filtration rates, thereby facilitating more extensive global application of this methodology.

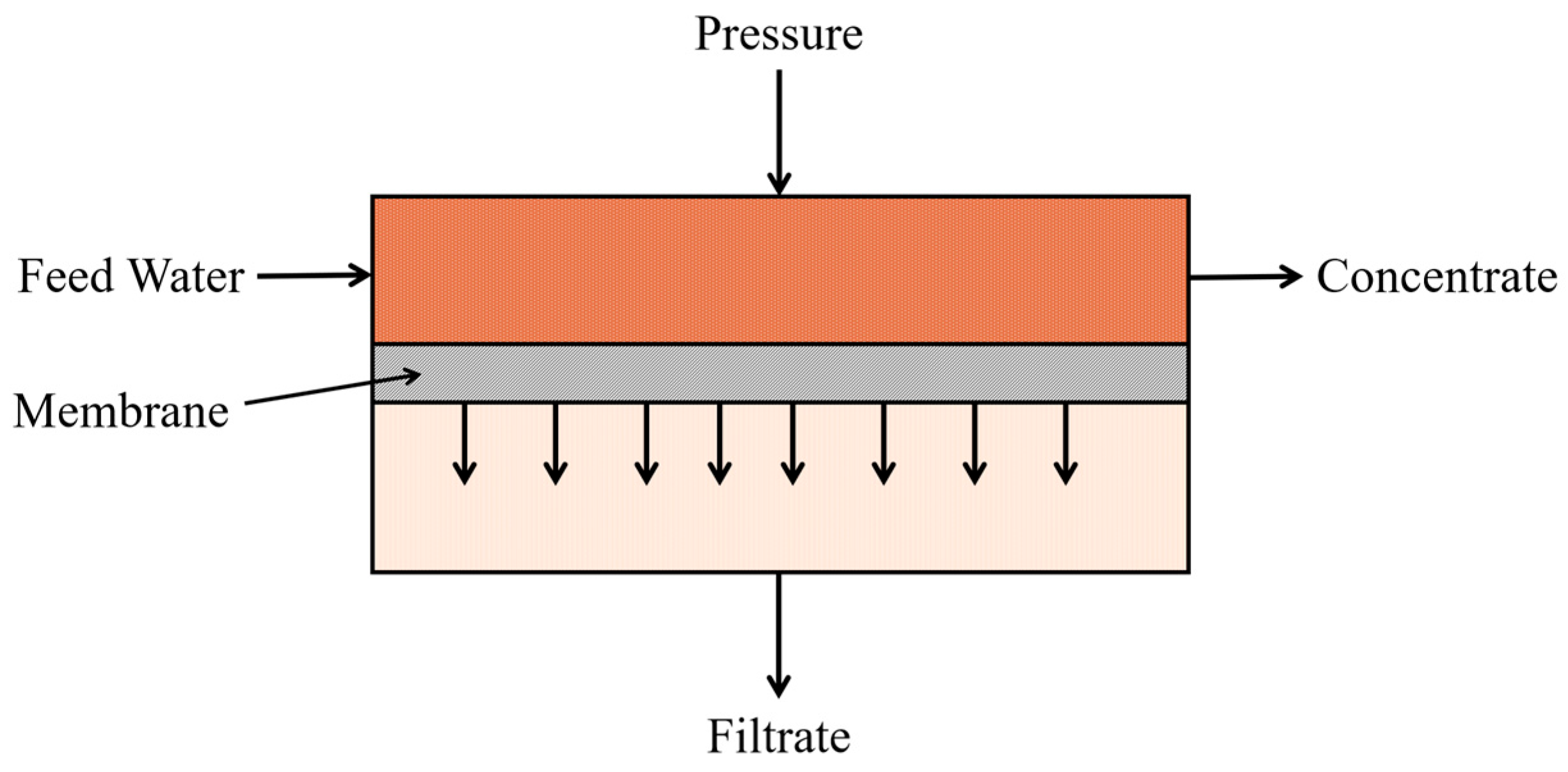

2.5. Membrane Separation Technologies

Membrane separation technology facilitates the segregation of constituents according to their the dimensions of the particulates and the trans membrane pressure applied. The membrane serves as a physical partition that separates the influent feed into permeate (filtered effluent) and the retentate (containing the concentrated, retained particles). In order to ensure efficacious filtration, the membrane features tailored pore sizes that selectively remove particles of particular dimensions. Pore diameters may range from 0.1 μm to several nm. Feed movement is primarily driven by the trans membrane pressure gradient, facilitating the passage of fine particles and contaminants from the high- to low-pressure regions [

66]. Critical design variables—including the material of the membrane composition, pore size, and module configuration (such as spiral wound, plate and frame, hollow fiber, or tubular)—must be meticulously engineered based on the physicochemical properties of the feed water. Such optimization is essential to maximize filtration efficacy while mitigating membrane fouling, which remains a predominant challenge in membrane-based separation [

67]. The fundamental process by which turbidity-causing matter is sequestered via the membrane is illustrated in

Figure 2.

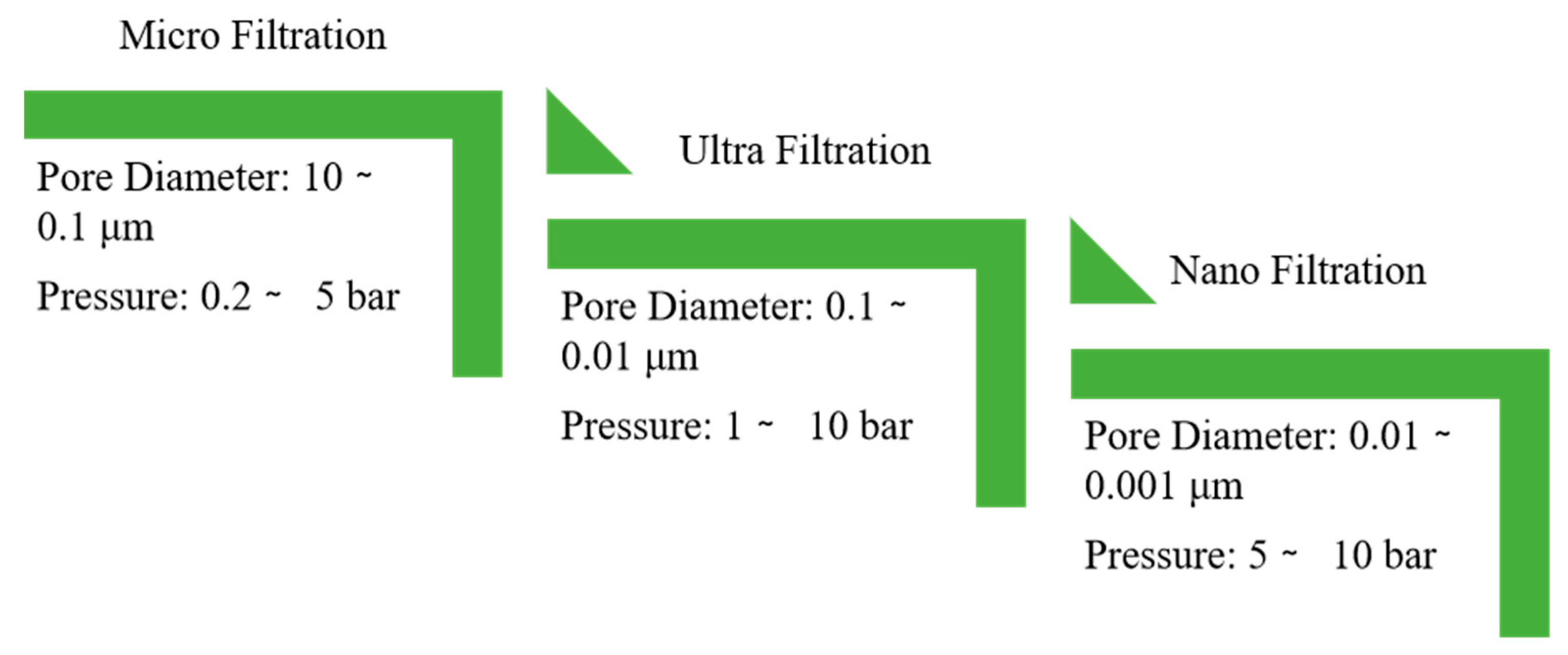

Membrane filtration technologies for the efficacious remediation of turbidity are broadly classified into microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), and nanofiltration (NF). The classification of these techniques is fundamentally based on their selective separation capabilities. The nominal pore diameters and the corresponding operational pressure requirements characteristic of each membrane category are systematically presented in

Figure 3.

Membrane filtration demonstrates particular efficacy in the treatment of aqueous matrices characterized by low turbidity concentrations. Conversely, when treating influent with elevated turbidity levels, the implementation of rigorous pre treatment protocols—such as coagulation-flocculation and sedimentation—is imperative to sustain membrane operational efficiency and ensure long-term performance stability. Furthermore, these membrane processes are frequently deployed as a pre treatment barrier in reverse osmosis (RO) desalination facilities, where they serve to mitigate turbidity and safeguard the RO membrane integrity from premature degradation.

2.5.1. Micro-Filtration (MF)

Microfiltration (MF), a conventional methodology for turbidity reduction, utilizes membranes characterized by pore diameters spanning 0.1 to 10 μm and functions under low-pressure conditions [

68]. These membranes facilitate the sequestration of suspended solids, colloidal substances, and additional turbidity-inducing constituents, operating analogously to conventional coarse filtration systems. Typically, MF membranes are fabricated from various materials, including high-density polyethylene (HDPE), glass fiber-reinforced plastic, polypropylene, polycarbonate, and ceramics. From these, membranes manufactures using cermaics exhibit superior turbidity removal efficiency coupled with exceptional chemical resistance, thermal resilience, and robust mechanical stability [

69,

70].

Microfiltration membranes are capable of removing turbidity with efficiencies reaching over 99%. A study used microfiltration membranes (Polypropylene - 1 µm and ceramic - 0.5 µm) to remove turbidity from Tigris river water. While the ceramic membranes achieved up to 99.5% turbidity removal in which turbidity was removed from 65 NTU to 0.86 NTU, the polypropylene membrane was less efficient, reducing turbidity to 2.7 NTU [

71]. In another such study, hybrid ceramic membrane were used to treat surface water containing high dissolved organic matter where the turbidity was reduced from an average initial value of 35 NTU to less than 0.02 NTU [

72]. The membrane has additionally been applied to sugar industry wastewater, where it achieved a turbidity removal efficiency of 98.26% [

73].

Several investigations have evaluated turbidity removal as a pre-treatment for reverse osmosis (RO) membranes in desalination plants.

Table 4 summarizes the turbidity removal efficiencies of modified microfiltration membranes designed to enhance performance in desalination pre treatment and some other types of wastewater.

To increase the turbidity removal efficiency of microfiltration, pre treatment such as coagulation or direct filtration can be done. For example, Meng et al. (2019) found that in-situ coagulation prior to microfiltration reduced turbidity to 1.03 NTU, which was further lowered to 0.2 NTU by the microfiltration membrane, resulting in an overall turbidity removal efficiency of 99% [

80]. When a cloth media filter was used prior to membrane filtration, the membrane effluent achieved a turbidity of 0.04 NTU [

81]. Thus, it can be seen that using microfiltration, with or without pre-treatment, provides promising turbidity removal efficiencies in water treatment.

2.5.2. Ultrafiltration (UF)

Ultrafiltration (UF) represents a conventional membrane-based purification methodology utilizing pore diameters in the range of 0.001 - 0.1 μm, rendering it a highly efficacious technique for potable water treatment. This process facilitates the selective passage of water, inorganic salts, and other low-molecular-weight solutes, while concurrently sequestering suspended solids, colloidal matter, and pathogenic microorganisms [

82]. In the context of turbidity remediation, UF exhibits superior removal efficiency, yielding an effluent of consistent and reproducible quality. Typically, UF membranes are fabricated from polymeric substrates such as polysulfone (PS) and polyethersulfone (PES). These materials are characterized by advantageous physicochemical properties, including robust mechanical integrity, chemical resilience, and thermal resilience, which collectivley contribute to optimized water treatment efficiency.

Similar to MF, UF too is used directly, as a pre-treatment for RO membranes or can be used after pre treatment, having turbidity removal efficiencies up to 99%. The following table (

Table 5) summarizes several research done with respect to these aspects.

According to studies using UF membranes, higher turbidity removal efficiencies are achieved when these membranes are applied to water that has already undergone pre-treatment processes such as coagulation, adsorption, etc.

2.5.3. Nanofiltration (NF)

As a technical advancement in membrane separation, the integration of nanotechnology has facilitated an innovative approach to turbidity remediation through the development of nanofiltration (NF) membranes. These membranes are characterized by extremely reduced pore diameters, typically on the order of 1 nm. As a pressure-driven membrane process, NF resembles other membrane techniques, yet it functions at lower pressures and relies on a mechanism of charge-based repulsion. This mechanism confers selective permeability, permitting for the passage of monovalent ions while primarily retaining multivalent species. Consequently, NF membranes exhibit significant efficacy in the selective separation and sequestration of solutes within diverse process streams [

88]. They are applicable to the treatment of groundwater, surface water, and wastewater sources, effectively mitigating turbidity, microbial pathogens, hardness, and various other impurities [

89].

In contrast to UF and MF membranes, NF membranes are predominantly employed following pre-treatment for turbidity removal and are seldom used either as a standalone process or as an initial pre-treatment step. For instance, a case study treating high-turbidity storm water utilized coagulation–sedimentation as a pre-treatment before NF membranes, followed by RO, producing drinking water that met acceptable quality standards [

90]. Additionally, to reduce fouling of NF membranes, chemical coagulation has been applied in certain studies, achieving overall turbidity removal efficiencies of up to 95% [

91]. In another study, Sherhan and Bashir (2016) applied NF membranes to feed water previously treated via UF, resulting in an overall turbidity removal efficiency exceeding 95% [

92].

Therefore, it can be seen that by utilizing these types of membranes, either directly or with pre-treatment, higher turbidity removal efficiencies can be achieved along with consistent water quality. In cases where water has very low turbidity levels, these membranes can be used without pre-treatment. They also require less land area compared to sand filters in conventional treatment plants and can provide very high water quality, which is sometimes necessary for certain industrial processes. These membranes are particularly useful in areas with limited space and, due to their flexible nature, are feasible in regions with increasing population demand. The main disadvantage of membrane use is fouling, which increases operational costs to maintain the necessary filtration flux. To mitigate fouling, membranes require chemical cleaning and monitoring, adding to operational expenses. For membranes such as UF and MF, frequent backwashing may also be necessary, depending on feed water quality and flux. But, this backwash water (especially if there is a high volume) may require its own secondary treatment either for further reuse or disposal. Overall, the use of these membranes is generally not affordable due to high capital, operation, and maintenance costs [

93].

While membrane filtration represents an established paradigm in water treatment, the escalating complexity of modern pollutants necessitates the continuous evolution of this technology. Current research and development are focused on enhancing performance efficiency, optimizing energy consumption, and elevating permeate quality. Furthermore, advancements in operational sustainability—specifically regarding the innovation of novel membrane materials and module architectures—are essential to mitigate inherent limitations, such as fouling and periodic replacement [

67]. Consequently, membrane technology remains a dynamic and versatile methodology, continually adapting to address a broad spectrum of contaminants that contribute to turbidity within contemporary water and wastewater treatment infrastructures.

3. Adsorptive and Transformation Techniques:

3.1. Adsorption

Adsorption is fundamentally categorized as a conventional and robust methodology for the remediation of water and wastewater. This process involves the removal of solute species (adsorbates) from the aqueous phase, which subsequently attach to the inter facial surface of a solid adsorbent. The constituents can be immobilized via physical interactions, such as van der Waals forces, or via the formation of chemical bonds at the adsorbent surface [

90]. Commonly utilized adsorbent materials comprise activated carbon, silica, zeolites and alumina, among others [

95]. In operational practice, the adsorbent media is typically configured within a fixed-bed reactor or a packed column. As the process progresses, contaminants accumulate within the media, giving rise to an adsorption front, commonly known as the Mass Transfer Zone (MTZ). This region denotes the specific volume of the bed where active adsorption occurs. As the upstream media reaches its maximum capacity or saturation point, the MTZ migrates longitudinally through the column until the concentration of the adsorbate in the effluent begins to rise. With prolonged use, contaminants start to emerge in the treated effluent, indicating that the adsorbent is nearing the end of its effective capacity [

96]. The adsorption process is dependent on several important variables, namely contact time, pH, temperature, initial adsorbate concentration and adsorbent dosage [

97]. As a polishing stage in tertiary treatment, adsorption is applied after coagulation (and flocculation) and filtration, efficiently removing contaminants that secondary treatment methods cannot adequately address [

98].

Recent advancements in adsorbent materials, specifically the integration of nanotechnology, have led to the development of nano-adsorbents that exhibit significantly enhanced turbidity removal efficiencies compared to conventional alternatives. As a result, a diverse range of nano-adsorbent classes has been established, such as carbon-based nanomaterials, metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, zeolites, nanocomposites, and bio-adsorbents [

99].

Table 6 provides a summary of representative nano-adsorbents along with their principal characteristics.

Both conventional and nano-adsorbents demonstrate turbidity removal efficiencies exceeding 98%. Several case studies supporting these high removal efficiencies for each adsorbent type are summarized in

Table 7.

Adsorption offers several advantages as a turbidity removal method. In addition to achieving high removal efficiencies, it operates effectively over a broad pH range and is relatively easy to manage. Both fixed-bed adsorbent columns and batch reactors are straightforward to design, and the process can be readily scaled for applications ranging from small systems to large municipal or industrial facilities. Integrating nanotechnology into water treatment and wastewater treatment further enhances performance by reducing spatial footprint—which is particularly advantageous or point-of-use or decentralized applications—and providing significantly higher surface areas. Further, the adsorbent media can be reused by regeneration through thermal reactivation or chemical leaching. Despite its high turbidity removal capability, adsorption is not ideal as a stand-alone method for treating water with very high turbidity levels. It can also remove both contaminants and beneficial constituents due to its limited selectivity. Additionally, the adsorbent material may require periodic replacement or regeneration during operation [

113]. The long-term sustainability of these adsorbents is limited by surface poisoning; the permanent sequestration of specific organic ligands results in a cumulative loss of available surface area and functional site density, even after regeneration. Overall, adsorption’s strengths and limitations highlight its role as a complementary treatment step, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of multi-stage water and wastewater treatment processes.

3.2. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOP)

Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) is a category of novel transformation technologies that, while not primarily utilized for direct turbidity reduction, are implemented as tertiary treatment stages or as pre treatment for specific aqueous matrices. Central to these methods is the generation of hydroxyl (•OH) radicals, which rank among the most potent oxidizing agents documented [

114]. Hydroxyl radicals effectively break down various components responsible for turbidity, such as suspended solids, colloids, NOM, and complex micro pollutants [

115,

116,

117]. Upon generation, hydroxyl radicals react non-selectively with the pollutants, facilitating their breakdown and ultimately converting into non toxic mineralized products comprising of carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic salts. Production of hydroxyl radicals involves primary oxidants such as ozone (O

3) , hydrogen peroxide, and molecular oxygen, typically in conjunction with energy sources (UV radiation) or catalytic materials (Titanium dioxide - TiO₂, Cerium oxide - CeO₂) [

118]. Various AOP configurations have been investigated for their efficacy in turbidity remediation, most notably photocatalysis, UV/H₂O₂ systems, and Fenton-based reactions.

3.2.1. Photocatalysis

This methodology utilizes photocatalitic semi conductors, such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃), to degrade or remove pollutants from water matrices.When photons with sufficient energy strike the surface of these semiconductors, electron–hole pairs are generated. These charge carriers migrate to the photocatalyst surface, interacting with water molecules and dissolved oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). The generated ROS trigger redox reactions that degrade organic pollutants, inactivate microbial pathogens, and decompose complex contaminants, including those contributing to turbidity [

119,

120].

Photocatalysis has demonstrated turbidity removal efficiencies ranging from 71% to over 95% across diverse water sources. A study on biologically treated wastewater utilizing TiO₂ reported a peak turbidity removal of 71.6% under natural solar exposure at a 60 mg/L catalyst dosage whereas lower catalyst concentrations resulted in diminished performance [

121]. Another investigation involving municipal wastewater achieved 95.17% turbidity reduction under optimized reaction intervals and catalyst loading conditions, with UV irradiation exhibiting superior performance relative to visible light [

122]. Furthermore, solar photocatalytic reactors employed as a pretreatment stage for membrane fouling mitigation attained removal efficiencies near 95% through the synergistic application of UV light and TiO₂ [

123]. A comparative assessment of photocatalysts—comprising TiO₂, CuSO₄, ZnSO₄, and CuS —yielded turbidity removal efficiencies of 78.6% for TiO₂ and 79% for ZnSO₄. While CuSO₄ exhibited negligible performance, CuS achieved 73.4% and 90.03% removal in synthetic and raw wastewater, respectively [

124]. The efficacy of photocatalysis has been further augmented by the integration of nano technology. Nanomaterials manifest unique physicochemical properties compared to their bulk counterparts driven by quantum effects and significantly expanded surface areas, which enhance their electrical, mechanical, magnetic, chemical, and optical properties [

125]. Research indicates that nanocatalysts amplify oxidation potential by facilitating the efficient generation of surface-generated reactive oxidants, thereby accelerating the breakdown of waterborne pollutants [

126].

3.2.2. UV/Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

In the UV/H₂O₂ process, a homogeneous Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) in which ultraviolet irradiation promotes the dissociation of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), producing highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH), as expressed in Equation (5):

Hydrogen peroxide necessitates externally induced activation to promote the efficacious production of •OH radicals. UV photons supply sufficient energy to initiate the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. Photolytic kinetics are largely dictated by the intensity of ultraviolet radiation, and the quantum yield of hydrogen peroxide decomposition at 254 nm is estimated to be around 0.5. The effectiveness of the process depends on operational conditions such as organic and inorganic loading, solution transmittance, pH, temperature, and hydrogen peroxide concentration. An excessive concentration of H₂O₂ may exert a scavenging effect on the generated radicals, thereby attenuating oxidation rates. Conversely, a sub-optimal dosage restricts the formation of hydroxyl radicals, leading to a reduction in global process efficiency [

127,

128,

129].

The UV/H₂O₂ system is well established as an efficient approach for the oxidative removal of dissolved organic compounds, such as natural organic matter (NOM) and biofilm-derived materials, while also achieving effective microbial disinfection. Consequently, it serves as an indirect yet efficacious methodology for turbidity reduction. This process mitigates the concentration of turbidity causing pollutants fragmenting fine colloidal particles and organic constituents that frequently elude conventional sedimentation or filtration stages [

130]. Furthermore, specific turbidity-inducing particles that either obstruct coagulation processes or penetrate filtration units are efficiently remediated via this AOP technique [

131]. Although UV/H₂O₂ is seldom utilized as an independent treatment step, it can augment downstream operations such as coagulation, filtration, etc by degrading residual pollutants into low-molecular-weight, compounds exhibiting reduced light-scattering characteristics thereby enhancing overall water clarity and turbidity remediation.

3.2.3. Fenton Processes

Fenton processes are AOP techniques that uses hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) with iron ions (Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺) to produce highly reactive hydroxyl (•OH) and hydroperoxyl (•O₂H) radicals. The general reactions for the Fenton process are as below (8,9):

As delineated by the aforementioned equations, Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions facilitate the generation of hydroxyl radicals through interaction with hydrogen peroxide. Typically, Fe²⁺ serves as the predominant catalytic species in this process and possesses the capacity to yield Fe

3+; however, the reduction of Fe

3+ back to Fe²⁺ proceeds at a significantly lower kinetic rate [

132,

133]. As such, pH should be rigorously regulated within a range of approximately 2.8 to 3.0, a condition in which both iron species maintain stability and catalytic activity [

134]. Furthermore, the maintenance of an optimized Fe/H₂O₂ proportions are imperative, since exceeding the ideal dosage of either reagent can lower the overall reaction efficiency. The dominant reaction mechanisms are systematically presented by Equations 10-14:

Numerous investigations have evaluated the application of the Fenton process, although its utilization as an isolated methodology specifically for turbidity remediation remains infrequent. In their 2020 study, João et al. investigated the ultrasound enhanced Fenton process applied to swine wastewater, focusing on how pH, contact time, and H₂O₂ dosage influence the reduction of color, turbidity, COD, and BOD₅. Under an optimized pH of 3 and an H

2O

2 dosage of 90mg/L, turbidity removal efficiency was 98.2% [

135]. A separate investigation integrated the Fenton process with ferric chloride-based coagulation–flocculation to effectively treat stabilized landfill leachate, resulting in complete turbidity removal [

136]. This synergistic configuration was similarly implemented for textile industry effluent, where turbidity, color, and COD were assessed at two pH values; 6.0 and 7.0. Following treatment, turbidity decreased to 0.8 NTU and 0.94 NTU, respectively, signifying a highly successful removal outcome [

137]. Furthermore, a research by Zaman et al. (2024), focusing exclusively on Fenton reactions, evaluated the reduction of turbidity, COD, BOD₅ and Total Organic Carbon (TOC) from pharmaceutical wastewater. Following pH adjustment to 7.0, a 99.55% turbidity removal was achieved, highlighting the significant efficiency of the Fenton process, whether used as a standalone treatment or alongside conventional approaches [

138].

Integration of electrochemical methods has further advanced the Fenton process, giving rise to the Electro-Fenton (EF) process. The process involves in situ formation of H₂O₂ through two-electron oxygen reduction at the cathode, coupled with simultaneous Fe²⁺ regeneration from Fe³⁺, thereby preserving catalytic activity [

139]. Numerous studies indicate that this approach effectively facilitates turbidity remediation. For instance, application of the Electro-Fenton process to effluent generated by coconut processing industries resulted in turbidity removal efficiencies of approximately 85% [

140]. Furthermore, application to aquaculture wastewater resulted in a reduction of approximately 88.7% [

141]. Collectively, these findings validate Electro-Fenton processes as robust and prospective methodologies for the mitigation of turbidity across diverse water and wastewater matrices.

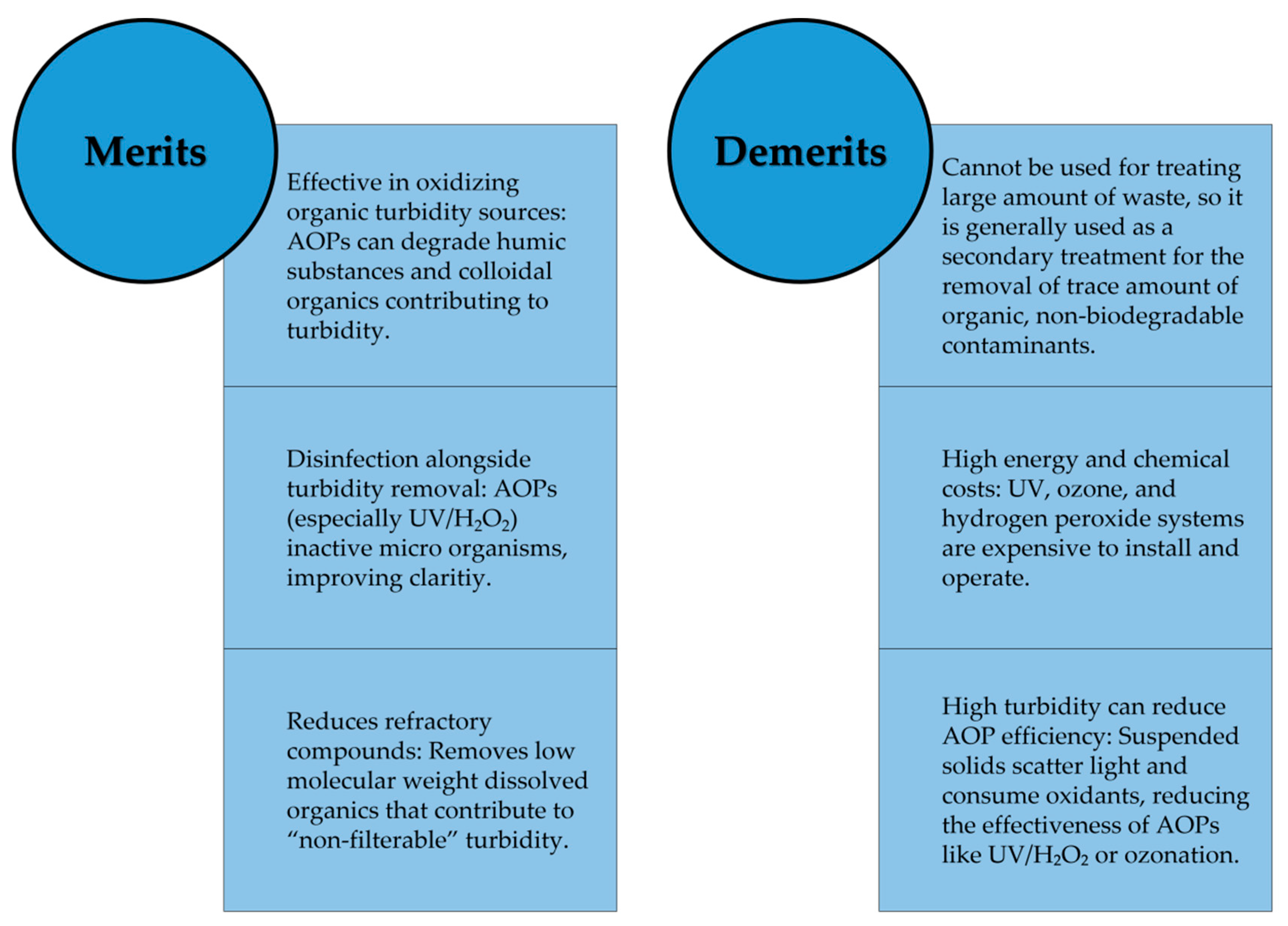

There are several merits and drawbacks of using AOPs for turbidity removal as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The catalysts which are theoretically not consumed can be recovered via filtration to be reused. But these may suffer from deactivation due to surface masking by mineral scales or oxidation of the catalyst surface it self, necessitating aggressive chemcial washing. While Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) exhibit significant potential for turbidity remediation across diverse aqueous matrices, the prevailing body of research remains primarily localized to controlled laboratory settings. Comprehensive large scale implementations amid variable operational conditions continue to be sparse and atypical. Furthermore, the potential for full-scale application of AOP infrastructures for the treatment of influent streams characterized by elevated turbidity—especially in economically and infra structurally constrained regions—has not been rigorously explored. A significant proportion of current literature prioritizes the degradation of organic matter, with turbidity reduction frequently regarded as an ancillary objective. Consequently, targeted investigations focusing specifically on the sequestration of turbidity-inducing constituents are imperative. Currently, the field lacks uniform, standardized testing protocols for the analysis of AOP performance relative to turbidity removal. The establishment of such standardized frameworks is essential to ensure consistency in evaluation and facilitate meaningful comparative analysis across divergent studies.

4. Hybrid and Assisted Techniques

To attain enhanced turbidity removal performance, the adoption of hybrid and assisted treatment configurations has emerged as a promising technological pathway. Such methodologies are based on the integrated application of multiple treatment processes arranged into one consolidated system. The precise architecture and sequential arrangement of the integrated units are dictated by the physicochemical characteristics of the influent, defined treatment goals and the specific operational constraints associated with each constituent component. Within such hybrid frameworks, individual processes are often engineered to target discrete contaminants, thereby providing a complementary enhancement of overall system performance. Typically, hybrid treatment approaches synthesize physical, chemical, and biological modalities to optimize treatment efficacy. Nevertheless, rigorous evaluation of systematic optimization of each process unit is required, since multiple operational variables exert a significant influence on the aggregate treatment efficiency. Some hybrid technologies that have been extensively investigated and implemented include:

Coagulation (with Flocculation) and Membrane Filtration

Membrane Bioreactor (MBR)and Coagulation

Ultrasound-Assisted Coagulation

4.1. Coagulation (with Flocculation) + Membrane Filtration

While coagulant application in water treatment demonstrates high efficacy, for the removal of numerous contaminants, it may not consistently yield effluent of the requisite quality as a standalone intervention [

147]. This inherent limitation necessitates the integration of coagulation with supplementary methodologies, such as membrane filtration, to optimize treatment performance.

In practice, turbidity-focused hybrid systems often combine coagulation–flocculation as a pre treatment step prior to membrane filtration. As an example, this integrated approach was employed in the elimination of protozoan parasites from surface water in the Pirapó River basin in Brazil. Although turbidity reduction was not the primary focus, the study achieved turbidity removal efficiencies exceeding 90% using microfiltration in combination with Moringa oleifera as a natural coagulant [

147]. Similarly, the application of this methodology to wood-processing wastewater, using nanofiltration, achieved a remarkable turbidity removal efficiency of 99.7% [

148]. Investigations into surface water treatment in Malaysia that employed ultrafiltration as a pre-treatment step prior to coagulation achieved a turbidity removal efficiency which exceeded 99% [

149]. Furthermore, integration of ferric chloride (FeCl₃) in a coagulation–flocculation and membrane filtration hybrid system led to a 99.7% reduction in turbidity for soap-industry effluent [

150].

4.2. Coagulation with Membrane Bio Reactor Technique

The sequential integration of coagulation and a membrane bioreactor (MBR) is recognized as a highly effective strategy for turbidity removal. Initially, suspended solids are destabilized during the coagulation step, promoting the formation of larger flocs in the subsequent flocculation stage, which are then effectively separated. The supernatant obtained after clarification is fed into the MBR system, which combines biological treatment—primarily via the activated sludge process—with membrane-based separation. The membrane unit, typically consisting of microfiltration or ultrafiltration modules, functions as a robust physical barrier, efficiently separating treated permeate from biomass and residual particulates [

151,

152]. A schematic of the MBR configuration is presented in

Figure 5.

The implementation of coagulation as a pre treatment stage facilitates the removal of macro-particulates that would otherwise exacerbate membrane fouling within downstream units. Saeedika et al. (2025) studied this hybrid configuration aimed at improving the sequestration of chromium and nutrients from tannery wastewater, using turbidity as a primary water quality metric. Following the initial coagulation stage, approximately 90% turbidity reduction was observed. Subsequent treatment via a membrane bioreactor (MBR) further refined the effluent quality, ultimately attaining turbidity removal efficiencies of 99.8% [

153]. In a separate case, the methodology was demonstrated to be effective for dairy wastewater remediation. Under an optimized operational regime with a polyaluminium chloride (PACl) dosage of 900 mg/L at pH 7.5, turbidity removal reached 98.85% in this application [

154].

4.3. Ultrasound Assisted Coagulation

As the name implies, this methodology leverages the synergy between conventional coagulation and ultrasonic irradiation to improve turbidity removal. This process exploits both ultrasound-induced mechanical and sonochemical phenomena—specifically acoustic cavitation— in order to enhance the kinetics of coagulation with flocculation. Ultrasound facilitates the formation of cavitation bubbles that undergo violent collapse, generating localized extreme temperatures and pressures [

155,

156]. This phenomenon assists in the fragmentation of larger aggregates into much smaller and reactive species, which promotes particle interactions and strengthens the coagulation process. Essentially, the application of ultrasound intensifies the interfacial interactions between chemical coagulants and suspended particulates, facilitating more effective destabilization and aggregation.

Numerous investigations have evaluated this hybrid configuration. For example, Zhang et al. (2006) utilized this technique for the sequestration of algal cells from aqueous media, achieving notable turbidity reductions between 85% and 93%, depending on the applied polyaluminium chloride (PACl) dosage (PACl) [

157]. Another study investigated the removal of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa and the subsequent control of disinfection byproducts after chlorination. Compared with conventional coagulation, the ultrasound-assisted approach significantly improved turbidity removal, increasing from a baseline of 51% to between 87% and 96% [

158].

Hybrid technologies offer superior turbidity removal efficiencies by integrating modalities such as coagulation and membrane filtration, ensuring the comprehensive sequestration of suspended solids and colloidal matter. These configurations significantly augment membrane longevity, as pre treatment stages—including conventional coagulation or electrocoagulation (EC)—mitigate membrane fouling and extend operational life cycles. Furthermore, the synergy between integrated methods can reduce chemical consumption and energy requirements by attenuating the necessary dosages or operational demands of individual units. Such configurations also provide enhanced stability in effluent quality, as hybrid systems effectively buffer fluctuations in raw water characteristics more robustly than standalone processes. Conversely, these systems entail higher capital and operational expenditures due to the proliferation of process units and control systems, which escalate installation, operation, and maintenance costs. The inherent operational complexity necessitates highly skilled personnel and precise system integration, while the overall physical footprint is expanded to accommodate multiple stages. Additionally, when coagulation or electrocoagulation is utilized, the generation of chemical sludge necessitates specialized handling and disposal protocols.

Despite these inherent constraints, integrated approaches remain highly applicable across a various water matrices. Through synergistic coupling of the constituent processes, these hybrid methodologies have achieve enhanced turbidity remediation and superior cumulative treatment performance relative to standalone techniques. Nonetheless, meticulous selection is required, as certain combinations may become cost-prohibitive; consequently, it is essential to identify configurations that optimize removal performance while maintaining economic viability.

5. Comparative Overview of Turbidity Removal Technology

To provide a clear comparison of these techniques, the following table (

Table 8) summarizes key performance indicators across multiple turbidity removal approaches, including removal efficiency, chemical requirements and scalability.

Based on the comparative analysis, turbidity removal efficiencies differ substantially among the examined treatment techniques, and no single method is universally optimal. Conventional processes—including coagulation–flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, and membrane separation—remain widely applied in water and wastewater treatment. However, methods such as adsorption, hybrid systems, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) often provide higher turbidity removal and improved effluent quality. Therefore, selecting an appropriate treatment strategy requires careful consideration of site conditions, influent characteristics, and performance objectives to achieve the desired turbidity reduction.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Turbidity persists as a multifaceted and recalcitrant challenge in the provision of potable and sustainable water. While fundamental methodologies—specifically coagulation-flocculation, filtration, adsorption, and membrane separation—form the foundation of modern treatment systems, they are increasingly hindered by operational constraints, including chemical sludge generation, membrane fouling, intensive maintenance requirements, and limited resilience to extreme turbidity fluctuations. Emerging technologies—such as Nanofiltration, EC, AOPs, and hybrid configurations—achieve high removal performance and broader applicability. However, their widespread adoption is currently constrained by scalability issues, elevated operational expenditures, and a lack of extensive longitudinal validation in field environments.

The existing body of literature suggests that a single-unit operation is insufficient to comprehensively mitigate turbidity in isolation. Consequently, future paradigms should favor the synthesis of multifaceted treatment trains, integrating established techniques with innovative technologies to maximize aggregate process efficiency. While certain integrated frameworks have been deployed, intensified research is required to circumvent the inherent limitations of conventional methodologies. Furthermore, treatment infrastructures must be engineered for adaptability, capable of modulating performance in response to seasonal variability and sudden increases in turbidity often triggered by climate-driven events. Sustainability and equitable access remain central, requiring that advanced water treatment approaches focus on energy efficiency, economic feasibility, and operational practicality, especially in settings most affected by high turbidity.

The subsequent phase of research and innovation in turbidity management should be directed toward several strategic priorities. With the development of smart, adaptive control systems—smart, AI-driven control systems integrated with real-time turbidity measurement can enhance coagulant dosing precision, lower energy requirements, and control fouling kinetics. Additionally, the adoption of sustainable alternatives, including bio-based coagulants, green nanoparticles, and recoverable adsorbents, marks an important trajectory for advancing the field. In rural and climate-vulnerable regions, the advancement of decentralized, mobile, and cost-effective solutions powered by renewable energy is essential. Finally, the execution of pilot-scale investigations in authentic environmental contexts is imperative, particularly for emerging methodologies, to substantiate their scalability, safety, and operational reliability.

In summary, turbidity remediation is transitioning into a transformative phase characterized by integration, intelligence, and sustainability. By embedding traditional approaches within flexible, technologically advanced systems, future water treatment infrastructures can achieve robust, economically viable, and equitable water provision, effectively mitigating the impacts of environmental stressors and demographic expansion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; methodology (literature search and screening), S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; validation, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera.; writing—review and editing, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; visualization (figures/tables), S.M.S.N Sumanasekera.; supervision, J.R. Rajapakse.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used “Grammarly” for the purpose of improving the language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NTU |

Nephelometric Turbidity Units |

| UV |

Ultra Violet |

| CSG |

Coal Seam Gas |

| PMF |

Pebble Matrix Filtration |

| RO |

Reverse Osmosis |

| NF |

Nano Filtration |

| UF |

Ultra Filtration |

| MF |

Micro Filtration |

| CNT |

Carbon Nano Tubes |

| AOP |

Advanced Oxidation Process |

| EC |

Electro Coagulation |

| GMF |

Granular Media Filtration |

References

- Bhadarka, M.; Vaghela, D.T.; Kamleshbhai, B.P.; Sikotariya, H.; Verma, P. Water Pollution: Impacts on Environment. ResearchGate. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383021412_Water_Pollution_Impacts_on_Environment.

- Anderson, C.W. Turbidity. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Book 9, Chapter A6.7. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Shi, B.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lv, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Laboratory Experiments to Assess the Effect of Chlorella on Turbidity Estimation. Water. 2022, 14, p. 3184. [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, J.U. Turbidity. ScienceDirect. 2009. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123706263000752.

- Voichick, N.; Topping, D.J.; Griffiths, R.E. Technical note: False low turbidity readings from optical probes during high suspended-sediment concentrations. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2018, 22(3), 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haule, K.; Kubacka, M.; Toczek, H.; Lednicka, B.; Pranszke, B.; Freda, W. Correlation between Turbidity and Inherent Optical Properties as an Initial Recognition for Backscattering Coefficient Estimation. Water. 2024, 16, p. 594. [CrossRef]

- LeChevallier, M.W.; Evans, T.M.; Seidler, R.J. Effect of turbidity on chlorination efficiency and bacterial persistence in drinking water. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1981, 42(1), 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies-Colley, R.J.; Smith, D.G. TURBIDITY SUSPENDED SEDIMENT, AND WATER CLARITY: A REVIEW. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2001, 37(5), 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeChevallier, M.W.; Au, K.-K. Water treatment and pathogen control: Process efficiency in extreme events; American Water Works Association Research Foundation: Denver, CO, 2004; Available online: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/LeChevallier-2004-Water.pdf.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Guidance Manual for Compliance with the Surface Water Treatment Rules: Turbidity Provisions, EPA 815-R-20-004. U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, 2020. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/documents/swtr_turbidity_gm_final_508.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Water quality and health: Review of turbidity – Information for regulators and water suppliers, WHO Reference Number WHO/FWC/WSH/17.01, Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-WSH-17.0.

- European Union (2020) Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Official Journal of the European Union L 435. p. pp. 1-62. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020L2184.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian Drinking Water Guidelines: Australian Drinking Water Guidelines Paper 6 National Water Quality Management Strategy (Version 4.0), Canberra: NHMRC / NRMMC. 2011. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-drinking-water-guidelines.

- Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. 2019) National Environmental (Ambient Water Quality) Regulations, No. 01 of 2019, Gazette Extraordinary No. 2148/20; Department of Government Printing: Colombo, 5 November 2019; Available online: http://203.115.26.10/ACT/2148-20_E.pdf.

- Malik, Q.H. Performance of alum and assorted coagulants in turbidity removal of muddy water. Applied Water Science 2018, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Robinson, J.; Chong, M.F. A review on application of flocculants in wastewater treatment. Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 2014, 92, pp. 489–508. [CrossRef]

- Lmipumps.com. Coagulation and Flocculation in Water Treatment. 2018. Available online: https://www.lmipumps.com/en/technologies/coagulation-and-flocculation-in-water-treatment/ (accessed on 14/06/2025).

- Exall, K. Coagulation and Flocculation. Water Encyclopedia. 2004, pp. 424–429. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.N.; Rajapakse, J.; Millar, G.; Dawes, L. Performance analysis of chemical and natural coagulants for turbidity removal of river water in coastal areas of Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 1st AISD International Multidisciplinary Conference: International Multidisciplinary Conference on Sustainable Development (IMCSD) 2016; Kabir, S.M.Z., Hasan, M.Z., Eds.; Australian Institute for Sustainable Development (AISD): Australia, 2016; pp. 172–182. Available online: https://scholar.google.com.au/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=UCssR4oAAAAJ&citation_for_view=UCssR4oAAAAJ:9yKSN-GCB0IC.

- Ladislas, N. Turbidity Removal efficiency of different inorganic coagulants during water treatment - A review. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, [online] 2016, 50(2), 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Fagnekar, N.A. REMOVAL OF TURBIDITY USING ELECTROCOAGULATION. International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology 2015, 04(06), 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tech, G.W. Electrocoagulation: The Future of Water Treatment Technology - Genesis Water Technologies. Genesis Water Technologies. 2024. Available online: https://genesiswatertech.com/blog-post/electrocoagulation-the-future-of-water-treatment-technology/.

- Electrocoagulation Water Treatment - VentilAQUA. Available online: https://ventilaqua.com/chemical-treatment/electrocoagulation-water-treatment/ (accessed on 19/06/2025).

- Mao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cotterill, S. Examining Current and Future Applications of Electrocoagulation in Wastewater Treatment. Water. 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Makwana, A.R. Factors Influencing Electrocoagulation Treatment of UASB Reactor Effluent. Water science and technology library. 2018, pp. 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Ebba, M.; Asaithambi, P.; Alemayehu, E. Investigation on operating parameters and cost using an electrocoagulation process for wastewater treatment. Applied Water Science 2021, 11(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, L.W.M.; Zin, N.S.M. Application of Electrocoagulation In Various Wastewater And Leachate Treatment-A Review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2018, 140, p. 012052. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A. Removal of water turbidity by the electrocoagulation method. PubMed. 2008, 8, pp. 18–24. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235366690_Removal_of_water_turbidity_by_the_electrocoagulation_method.

- Kobya, M.; Hiz, H.; Senturk, E.; Aydiner, C.; Demirbas, E. Treatment of potato chips manufacturing wastewater by electrocoagulation. Desalination. 2006, 190, pp. 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Shivayogimath, C.B. TREATMENT OF SOLID WASTE LEACHATE BY ELECTROCOAGULATION TECHNOLOGY. International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology 2013, 02(13), 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeddin, K.; Naser, A.; Firas, A. Removal of turbidity and suspended solids by electro-coagulation to improve feed water quality of reverse osmosis plant. Desalination. 2011, 268, pp. 204–207. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajmi, F.; Al-Marri, M.; Almomani, F. Electrocoagulation Process as an Efficient Method for the Treatment of Produced Water Treatment for Possible Recycling and Reuse. Water Avaiblable at. 2024, 17(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, U.S.; Poddar, S.; Byun, H.-S. Electrocoagulation treatment of wastewater collected from Haldia industrial region: Performance evaluation and comparison of process optimization. Water Research. 2025, 268, p. 122716. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, R.; Jay, R.; Waterman, P.; Millar, G.; Sumanaweera, S. Emerging water treatment technologies for decentralised systems: An overview of selected systems suited for application in towns and settlements in remote and very remote regions of Australia and vulnerable and lagging rural regions in Sri Lanka. In Sustainable Economic Growth for Regional Australia (SEGRA) Conference 2014 Proceedings; Charters, K., Ed.; SEGRA: Australia, 2014; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mellifiq. Electrocoagulation Technology for Superior Water Treatment. 2025. Available online: https://mellifiq.com/en/electrocoagulation-technology/.

- Electrocoagulation. [online] Racoman.com. Available online: https://www.racoman.com/blog/electrocoagulation-wastewater-treatment-explained (accessed on 19/06/2025).

- Mollah, M.Y.; Schennach, R.; Parga, J.R.; Cocke, D.L. Electrocoagulation (EC)--science and applications. Journal of Hazardous Materials, [online] 2001, 84(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, T.K.C.; Nguyen, P.L.; Phung, T.V.B. Recent progress in highly effective electrocoagulation-coupled systems for advanced wastewater treatment. iScience. 2025, 28, p. 111965. [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.; Pham, A.L.-T. Mitigating Electrode Fouling in Electrocoagulation by Means of Polarity Reversal: The Effects of Electrode Type, Current Density, and Polarity Reversal Frequency. Water Research. 2021, 197, p. 117074. [CrossRef]

- Vesga-Rodríguez, C.P.; Donado-Garzón, L.D.; Weber-Shirk, M. Evaluation of high rate sedimentation lab-scale tank performance in drinking water treatment. Revista Facultad de Ingeniería Universidad de Antioquia. 2019, online] (90), pp. 9–15. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/430/43065097002/.

- Wang, W.; Li, C.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Wei, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Y. Removal Performances of Turbidity, Organics, and NH4+-N in a Modified Settling Tank with Rotating Biological Discs Used for Enhancing Drinking Water Purification. Water. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, S.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Innovative adaptation of coagulation-sedimentation-filtration process in lightly polluted urban rivers with seasonal high turbidity. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, T.; Ordóñez, R.; Abfertiawan, M.; Hasan, F.; Rizqi Meutia, R.; Al Fadhli, R. 7 7 Settling Characteristics and Treatment Settling Characteristics and Treatment Strategies for Open-Cast Coal Mine Strategies for Open-Cast Coal Mine Water in South Sumatra, Indonesia Water in South Sumatra, Indonesia. n.d. Available online: https://www.imwa.info/docs/imwa_2025/IMWA2025_Abfertiawan_7.pdf.

- Forestier, J.-P. How to Eliminate Turbidity in Well Water for Clear and Healthy Water? Diproclean.com. 2024. Available online: https://www.diproclean.com/en/solutions-impurities-water-house-xsl-537_538_545.html (accessed on 15/06/2025).

- Www.htt.io. Htt.io. 2024. Available online: https://www.htt.io/learning-center/understanding-sedimentation-water-treatment (accessed on 15/06/2025).

- BOQU. How to Reduce Turbidity in Water: Solutions and Technologies. Boquinstrument.com. 2024. Available online: https://www.boquinstrument.com/a-how-to-reduce-turbidity-in-water-solutions-and-technologies.html (accessed on 15/06/2025).

- www.etch2o.com. What is Sedimentation in Wastewater Treatment? - Etch2o. 2023. Available online: https://www.etch2o.com/what-is-sedimentation-in-wastewater-treatment/ (accessed on 15/06/2025).

- Burke, M.; Wells, E.; Larison, C.; Rao, G.; Bentley, M.J.; Linden, Y.S.; Smeets, P.; DeFrance, J.; Brown, J.; Linden, K.G. Systematic Review of Microorganism Removal Performance by Physiochemical Water Treatment Technologies. Environmental Science & Technology. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Thames Water (2024) Introduction and Background: Section 1 – Water Resources Management Plan 2024 (WRMP24), October 2024. Available online: https://www.thameswater.co.uk/media-library/5nmpjafr/intro-and-background.pdf (accessed on 01/01/2026).

- Guchi, E. Review on Slow Sand Filtration in Removing Microbial Contamination and Particles from Drinking Water. American Journal of Food and Nutrition, [online] 2015, 3(2), 47–55. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275097978_Review_on_Slow_Sand_Filtration_in_Removing_Microbial_Contamination_and_Particles_from_Drinking_Water_Ephrem_Guchi_1.

- Abdiyev, K.; Azat, S.; Kuldeyev, E.; Ybyraiymkul, D.; Kabdrakhmanova, S.; Berndtsson, R.; Khalkhabai, B.; Kabdrakhmanova, A.; Sultakhan, S. Review of Slow Sand Filtration for Raw Water Treatment with Potential Application in Less-Developed Countries. Water 2023, 15(11), 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiyo, J.K.; Dasika, S.; Jafvert, C.T. Slow Sand Filters for the 21st Century: A Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, [online] Available at. 2023, 20(2), 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, N.; Wahyudianto, F.E.; Salsabila, N.F.; Mohamed, R.R.; Kurniawan, S.B. Performance of Modified Slow Sand Filter to Reduce Turbidity, Total Suspended Solids, and Iron in River Water as Water Treatment in Disaster Areas. Journal of Ecological Engineering Available at. 2023, 24(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thames Water. sandSCAPE (Science and Novel Devices for Sustainable Cleaning and Productivity Enhancement) project. 2025. Available online: https://www.thameswater.co.uk/about-us/innovation/sandscape-project (accessed on 01/01/2026).

- Sparks, T.; Chase, G. Solid–Liquid Filtration; Elsevier eBooks, 2016; pp. 199–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, F.; Velten, S.; Egli, T.; Juhna, T. Biotreatment of Drinking Water. Comprehensive Biotechnology. 2011, pp. 517–530. [CrossRef]

- Tamakhu, G.; Amatya, I.M. Turbidity removal by rapid sand filter using anthracite coal as capping media. Journal of Innovations in Engineering Education 2021, 4(1), 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshr, S.; Moustafa, M.; Fayed, M.; Aly, S. Evaluation of water consumption in rapid sand filters backwashed under varied physical conditions. Alexandria Engineering Journal Available at. 2023, 64, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Harun, M.H. “Rapid-Slow Sand Filtration for Groundwater Treatment: Effect of Filtration Velocity and Initial Head Loss”. International Journal of Integrated Engineering 2022, 14(1), 276–286. Available online: https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/ijie/article/view/6683. [CrossRef]

- Yogafanny, E. Rapid Lava Sand Filtration for Decentralized Produced Water Treatment System in Old Oil Well Wonocolo. Journal of the Civil Engineering Forum Available at. 2019, 5(2), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, K.; Negm, M.; Abdelrazik, M.; Wahb, E. The Use of Roughing Filters in Water Purification. Scientific Journal of October 6 University 2014, 2(1), 50–58. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333683287_The_Use_of_Roughing_Filters_in_Water_Purification. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, J.P.; Fenner, R.A. Evaluation of Alternative Media for Pebble Matrix Filtration Using Clay Balls and Recycled Crushed Glass. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2011, 137(6), 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]