1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder affecting approximately 1% of the global population, characterized by positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (social withdrawal, anhedonia), and cognitive deficits [

1]. Current diagnosis relies primarily on clinical interviews and behavioral observation, which can result in delayed diagnosis and treatment [

2]. The development of objective, quantitative biomarkers could potentially improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce time to intervention, and support development of precision psychiatry approaches.

Electroencephalography (EEG) has been investigated as a modality for psychiatric biomarker development due to its non-invasive nature, high temporal resolution, relatively low cost, and widespread availability [

3]. Schizophrenia patients exhibit documented EEG abnormalities including reduced alpha power, increased delta and theta activity, altered connectivity patterns, and disrupted neural oscillations [

4,

5]. These neurophysiological signatures suggest that EEG may contain information relevant for diagnostic classification and disease monitoring.

1.1. Machine Learning Approaches for Schizophrenia EEG Classification

Classical machine learning approaches for schizophrenia detection typically extract handcrafted features from EEG signals including spectral power in canonical frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma), connectivity metrics (coherence, phase lag index), and complexity measures (entropy, fractal dimension), followed by classification using algorithms such as Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, or logistic regression [

6]. These approaches benefit from interpretability and the incorporation of domain knowledge through feature engineering, but may miss complex patterns not captured by predefined features.

Deep learning approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have been applied to learn representations directly from raw or minimally processed EEG data [

7]. EEGNet [

8] is a compact CNN architecture specifically designed for EEG classification that employs depthwise and separable convolutions to learn spatial and temporal features with relatively few parameters, making it suitable for limited-data regimes common in clinical research. The architecture has demonstrated success across various EEG-based brain-computer interface tasks.

1.2. The Generalization Problem

Despite published studies reporting high classification accuracy for schizophrenia detection from EEG—often exceeding 80–90%—clinical translation remains challenging [

6]. A critical concern is the widespread reliance on internal validation (cross-validation within a single dataset) without testing on independent external datasets acquired under different conditions and at different sites. This practice may lead to substantial overestimation of real-world clinical performance due to site-specific features learned by classifiers.

Several factors may contribute to generalization difficulty in EEG-based classifiers:

Recording Equipment Heterogeneity: Different EEG systems introduce systematic differences in signal characteristics, including varying amplifier properties, electrode impedance specifications, input impedance characteristics, common-mode rejection ratios, and analog-to-digital conversion specifications. These hardware differences introduce systematic biases that classifiers may learn as spurious features.

Protocol Variations: Differences in recording conditions (eyes-open vs. eyes-closed, task vs. rest, recording duration, environmental noise levels, time of day, subject positioning) affect signal characteristics in ways that vary systematically across sites.

Population Differences: Variations in patient demographics, illness duration, symptom severity, medication status (type, dosage, polypharmacy), comorbidities, and other clinical factors across datasets influence EEG patterns in ways that may not reflect core disorder characteristics. If these clinical factors differ systematically between sites, classifiers may learn to discriminate based on these secondary characteristics rather than disease-relevant features.

Diagnostic Criteria and Assessment: Differences in how schizophrenia diagnosis was established (diagnostic instruments used, clinician training, threshold for diagnosis, inclusion/exclusion criteria) may lead to heterogeneity in the patient groups labeled as “schizophrenia” across datasets.

Preprocessing Inconsistencies: Different artifact rejection strategies, filtering approaches, and referencing schemes can alter signal properties and contribute to site-specific signatures that classifiers may exploit.

Domain adaptation techniques, such as Correlation Alignment (CORAL) [

9], have been proposed to address distribution shift between training and test domains by aligning statistical properties of features across datasets. However, their efficacy for EEG-based psychiatric classification across sites remains underexplored.

1.3. Study Objectives and Importance of Transparent Reporting

This study addresses the generalization problem through a rigorous comparison of deep learning (EEGNet) and classical machine learning (Random Forest) approaches for schizophrenia EEG classification, with particular emphasis on external validation using a completely independent dataset acquired under different conditions. Our objectives are:

Compare EEGNet and calibrated Random Forest performance under subject-level stratified cross-validation on the ASZED-153 training dataset.

Evaluate generalization to an independent external dataset (Kaggle Schizophrenia EEG) acquired at a different site with different equipment and protocols.

Quantify the domain shift between datasets using Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD).

Assess whether CORAL domain adaptation can improve external dataset performance.

Provide transparent reporting of generalization failures to inform realistic assessment of technology readiness.

Importance of this work: While our results demonstrate substantial generalization challenges, we believe transparent reporting of these findings is essential for the field. The scientific literature suffers from publication bias favoring positive results, which can mislead the community about the true state of technology readiness and delay identification of fundamental challenges. By documenting the substantial performance degradation observed when models encounter data from different acquisition sites, we contribute to a more realistic assessment of current EEG-based classification methods and highlight critical challenges that must be addressed before clinical deployment. Our findings underscore that cross-validation performance, while scientifically valid for algorithmic comparison, should not be interpreted as evidence of clinical readiness without rigorous external validation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. ASZED-153 Dataset (Training)

The African Schizophrenia EEG Dataset (ASZED-153) was used for model development and internal validation [

10]. This dataset, publicly available at Zenodo (

https://zenodo.org/records/14178398), contains 153 subjects comprising 76 schizophrenia patients and 77 healthy controls from African populations. EEG recordings were acquired with 16 channels positioned according to the international 10-20 system using European Data Format (EDF) with accompanying clinical metadata.

The dataset includes multiple recording conditions: resting state (eyes-open and eyes-closed), cognitive tasks, and auditory paradigms. For this study, we utilized resting-state recordings to maximize comparability with the external validation dataset. The ASZED-153 dataset represents an important contribution to increasing representation of African populations in neuropsychiatric research, addressing historical underrepresentation in EEG biomarker studies.

After preprocessing and quality control (described below), the ASZED-153 dataset yielded 13,449 2-second epochs from 153 unique subjects (77 controls, 76 patients), providing substantial data for model training while maintaining subject-level separation during cross-validation.

2.1.2. External Validation Dataset (Kaggle Schizophrenia EEG)

An independent external dataset was used exclusively for generalization testing, with no data from this source used during model development, hyperparameter selection, or any aspect of model training. This dataset, publicly available on Kaggle (

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kacharepramod/eeg-schizophrenia), contains EEG recordings from 84 adolescent subjects divided into two groups:

EEG data in this dataset are stored in custom .eea format and were collected at a different institution using different recording equipment, protocols, and potentially different diagnostic assessment procedures compared to ASZED-153. This creates a realistic and challenging scenario for evaluating cross-site generalization, as the differences encompass multiple factors that would be encountered in real-world clinical deployment across different healthcare systems.

After preprocessing, the external dataset yielded 2,436 2-second epochs from 84 unique subjects (39 controls, 45 patients), providing adequate sample size for robust evaluation of generalization performance.

2.2. Preprocessing Pipeline

A harmonized preprocessing pipeline was applied to both datasets to minimize preprocessing-related differences while respecting the distinct characteristics of each dataset. All preprocessing was implemented in Python using SciPy, NumPy, and MNE-Python libraries.

2.2.1. Channel Standardization

Both datasets were standardized to a common 16-channel 10-20 montage: Fp1, Fp2, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, T3, C3, Cz, C4, T4, T5, P3, Pz, P4. Channel names were normalized to account for variations in naming conventions across datasets (e.g., FP1 → Fp1, T7 → T3, P7 → T5). Recordings with fewer than 8 usable channels were excluded from analysis to ensure minimum data quality. When fewer than 16 channels were available, missing channels were zero-padded to maintain consistent input dimensionality.

2.2.2. Signal Filtering

All EEG signals underwent the following filtering steps to remove artifacts and noise while preserving relevant neural oscillations:

Bandpass filtering: 0.5–45 Hz (4th order Butterworth filter, zero-phase implementation using filtfilt to avoid phase distortion)

Notch filtering: 50 Hz and 60 Hz (for power line noise removal, applied based on recording location)

Resampling: All signals resampled to 250 Hz using polyphase filtering with anti-aliasing to prevent artifacts

The 0.5–45 Hz bandpass encompasses all canonical EEG frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma) while removing DC drift and high-frequency noise.

2.2.3. Epoch Extraction and Artifact Rejection

Continuous EEG recordings were segmented into 2-second non-overlapping epochs (500 samples at 250 Hz). This epoch length balances temporal resolution with sufficient data for spectral analysis. Epochs with extreme amplitude values (exceeding ±100 V in any channel) were automatically rejected as likely artifacts (eye blinks, muscle activity, electrode displacement).

For the ASZED-153 dataset, we extracted epochs from resting-state segments only. For the external dataset, all available clean data were epoched. Additional visual inspection was performed on a random subset of epochs (10%) to verify artifact rejection efficacy and signal quality.

2.2.4. Normalization

Two normalization strategies were employed depending on the downstream model:

For EEGNet (deep learning): Raw epoch data were z-score normalized per channel to account for inter-channel amplitude differences. This normalization was computed independently for each epoch: , where and are computed from the specific epoch.

For Random Forest (classical ML): Spectral features were standardized using training set statistics (mean and standard deviation computed from training folds), with the same transformation applied to validation and test data to prevent information leakage.

2.3. Feature Extraction for Random Forest

For the Random Forest classifier, we extracted a comprehensive set of spectral, connectivity, and statistical features from each epoch, resulting in a 212-dimensional feature vector.

2.3.1. Spectral Band Power Features

Spectral band power features were extracted from each epoch using established frequency bands relevant to psychiatric disorders:

Delta (0.5–4 Hz): Associated with sleep and unconscious processes

Theta (4–8 Hz): Linked to drowsiness, meditation, and memory processes

Alpha (8–13 Hz): Dominant during relaxed wakefulness; often reduced in schizophrenia

Beta (13–30 Hz): Associated with active thinking and anxiety

Gamma (30–45 Hz): Related to cognitive processing and sensory binding

Power spectral density was estimated using Welch’s method with 50% overlapping windows (window length: 256 samples). Band power was computed by integrating the PSD over each frequency band using Simpson’s rule or trapezoidal integration. Features were log-transformed to approximate normal distributions: , where prevents numerical issues. This resulted in 80 spectral features (5 bands × 16 channels).

2.3.2. Coherence Features

Inter-hemispheric coherence was computed between symmetric electrode pairs to capture interhemispheric connectivity, which is often altered in schizophrenia. Coherence was computed using scipy.signal.coherence with the same parameters as spectral estimation. We computed coherence for 6 electrode pairs: (Fp1, Fp2), (F3, F4), (C3, C4), (T3, T4), (P3, P4), (O1, O2). For each pair, we extracted mean coherence within each of the 5 frequency bands, resulting in 30 coherence features (6 pairs × 5 bands).

2.3.3. Phase Lag Index (PLI)

Phase lag index was computed for the same 6 electrode pairs to measure phase synchronization while reducing sensitivity to volume conduction effects. PLI was estimated using the Hilbert transform to extract instantaneous phase: , where is the phase difference between electrode pairs. This yielded 6 PLI features.

2.3.4. Statistical Features

Time-domain statistical features were extracted per channel to capture signal characteristics not evident in spectral analysis:

Mean amplitude (normalized by standard deviation)

Standard deviation (normalized by absolute mean)

Skewness (asymmetry of amplitude distribution)

Kurtosis (tailedness of amplitude distribution)

Root-mean-square amplitude (normalized by standard deviation)

Peak-to-peak amplitude (range, normalized by standard deviation)

These resulted in 96 statistical features (6 features × 16 channels). Normalization of statistical features improved numerical stability and classifier performance.

All features were concatenated into a single 212-dimensional feature vector per epoch, with any NaN or infinite values replaced with zero.

2.4. Model Architectures

2.4.1. EEGNet Architecture

EEGNet was implemented in PyTorch following the architecture proposed by Lawhern et al. [

8]. The network consists of three main convolutional blocks designed to efficiently learn spatial and temporal features from multi-channel EEG data.

Block 1 - Temporal Convolution:

2D temporal convolution: 8 filters, kernel size (1, 64)

Batch normalization

Purpose: Learn temporal filters capturing frequency-specific patterns

Block 2 - Depthwise Spatial Convolution:

Depthwise 2D spatial convolution: kernel size (16, 1), depth multiplier D=2

Batch normalization

ELU (Exponential Linear Unit) activation

Average pooling (1, 4) for temporal downsampling

Dropout () for regularization

Purpose: Learn spatial filters specific to each temporal filter

Block 3 - Separable Convolution:

Separable 2D convolution: 16 filters, kernel size (1, 16)

Batch normalization

ELU activation

Average pooling (1, 8) for further temporal downsampling

Dropout () for regularization

Purpose: Learn higher-level temporal features

Classification Head:

Training Configuration:

Optimizer: Adam (, , weight decay )

Learning rate: 0.001 with ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler (factor=0.5, patience=5 epochs)

Loss function: Cross-entropy with class weights inversely proportional to class frequencies

Early stopping: Patience of 15 epochs based on validation loss

Maximum epochs: 100

Batch size: 32

Gradient clipping: Max norm = 1.0 to prevent exploding gradients

The model was implemented with approximately 2,800 trainable parameters, making it computationally efficient and suitable for limited data scenarios.

2.4.2. Random Forest with Isotonic Calibration

The Random Forest classifier was implemented using scikit-learn with the following hyperparameters selected through preliminary grid search:

Number of trees: 500 (increased from default for ensemble diversity)

Maximum depth: 15 (moderate depth to prevent overfitting)

Minimum samples per leaf: 2 (conservative to capture subtle patterns)

Class weights: Balanced (inversely proportional to class frequencies)

Maximum features: (default, for decorrelation)

Bootstrap: True (with replacement for training each tree)

Random state: 42 (fixed for reproducibility)

n_jobs: -1 (parallel processing using all CPU cores)

We applied isotonic regression calibration [

11] to improve probability reliability and reduce overconfidence in predictions. Calibration was performed using

CalibratedClassifierCV with 5-fold cross-validation on the training data, transforming uncalibrated Random Forest probability estimates into calibrated probabilities that better reflect true posterior probabilities.

2.5. Cross-Validation Strategy

Subject-level stratified 5-fold cross-validation was employed to ensure robust evaluation and prevent information leakage. This strategy is critical for EEG classification to avoid overoptimistic performance estimates.

Implementation: All epochs from a given subject were assigned to the same fold, ensuring that the model was evaluated on entirely unseen subjects in each iteration. This prevents the classifier from learning subject-specific patterns (e.g., individual alpha frequency, baseline amplitude characteristics) that would artificially inflate validation performance. Stratification ensured that class proportions were maintained approximately constant across folds.

We used StratifiedGroupKFold from scikit-learn, where groups correspond to subject IDs. This guarantees:

No subject appears in both training and validation sets within a fold

Each subject appears in exactly one validation fold

Class balance is preserved across folds

For each fold, we report per-fold metrics and compute mean and standard deviation across folds to assess variability and model stability.

2.6. Domain Adaptation: CORAL

Correlation Alignment (CORAL) [

9] was applied to address the distribution shift between the ASZED-153 training dataset and the external validation dataset. CORAL is a simple yet effective unsupervised domain adaptation technique that aligns the second-order statistics (covariance matrices) of source and target feature distributions.

Mathematical formulation:

where:

is the source feature matrix (ASZED-153 training data)

is the target feature matrix (external validation data)

is the source covariance matrix with regularization

is the target covariance matrix with regularization

is a small regularization term for numerical stability

This transformation adjusts the source features to have the same covariance structure as the target features while preserving the correlation structure within the source domain. The transformation is computed using eigendecomposition: and , where V and are eigenvector and eigenvalue matrices.

CORAL was applied only to the Random Forest pipeline (spectral/connectivity/statistical features) due to the difficulty of applying such transformations to the learned internal representations of deep neural networks without extensive architectural modifications or adversarial training approaches.

2.7. Domain Shift Quantification: Maximum Mean Discrepancy

Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) [

12] was used to quantify the magnitude of distribution shift between the ASZED-153 and external datasets. MMD is a kernel-based statistical test that measures the distance between two probability distributions

P and

Q in a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS):

where is a feature map induced by a kernel function , and denotes the norm in the RKHS .

Implementation details:

Kernel: Gaussian RBF kernel

Bandwidth: (median heuristic)

Dimensionality reduction: PCA to 100 components before MMD computation for computational efficiency

Sample size: Maximum 200 samples per dataset for tractable computation

MMD values greater than 0.05 typically indicate meaningful distributional differences. The empirical MMD estimate is computed as:

We report both the original MMD (between ASZED-153 and external data) and post-CORAL MMD to quantify the effectiveness of domain adaptation.

2.8. Pilot Hardware Exploration: BioAmp EXG Pill

As a preliminary hardware feasibility exploration, we conducted pilot testing with the BioAmp EXG Pill (Upside Down Labs, India) paired with an ESP32 microcontroller for low-cost, portable EEG acquisition. The BioAmp EXG Pill is a compact analog-front-end (AFE) biopotential signal acquisition board designed for EMG, ECG, EOG, and EEG recording.

Hardware specifications:

Board dimensions: 25.4 mm × 10.0 mm

Input channels: 1 differential channel (IN+, IN-, REF)

Gain: Configurable (default: high gain for EEG)

Bandwidth: Configurable bandpass filter

Interface: Analog output compatible with standard ADCs

Cost: Approximately $15 USD per unit

Pilot configuration:

Microcontroller: ESP32 (Espressif Systems)

Sampling rate: 256 Hz (14-bit ADC)

Electrode placement: Fp1 (IN+), Fp2 (IN-), ear reference (REF)

Recording format: European Data Format (EDF)

Software: Custom Python script for visualization and EDF export

We successfully recorded single-channel EEG data, visualized brain activity in real-time, and saved recordings in standard EDF format compatible with clinical EEG analysis software. Signal quality was adequate for observing dominant alpha rhythm and basic waveform morphology. However, classification performance was not evaluated as our models were trained on 16-channel data.

Scalability considerations: Our approach could theoretically scale to 16 BioAmp EXG Pill units (one per channel) for full 16-channel compatibility with our trained models. This would enable a complete low-cost EEG acquisition system ($240 for 16 channels, compared to $10,000–$50,000 for clinical-grade systems) suitable for resource-constrained settings. However, funding constraints limited this pilot to single-channel demonstration. The pilot establishes proof-of-concept for future development of affordable, open-source EEG systems for psychiatric research in low- and middle-income countries.

2.9. Evaluation Metrics

The following metrics were computed to provide comprehensive assessment of model performance:

Accuracy: Proportion of correct predictions:

AUC-ROC: Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve, measuring discrimination ability across all classification thresholds

Sensitivity (Recall): True positive rate: (proportion of schizophrenia patients correctly identified)

Specificity: True negative rate: (proportion of healthy controls correctly identified)

Balanced Accuracy: Average of sensitivity and specificity: (accounts for class imbalance)

Brier Score: Mean squared error between predicted probabilities and true binary labels: , measuring calibration quality (lower is better)

Expected Calibration Error (ECE): Average absolute difference between predicted probability and observed accuracy within 10 equally-spaced probability bins, providing another measure of calibration

Confusion matrices were computed for each model and condition to provide detailed breakdown of classification errors.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Performance differences between EEGNet and Random Forest during internal cross-validation were assessed using paired t-tests on fold-level metrics. Effect sizes were quantified using Cohen’s d to assess practical significance beyond statistical significance. Statistical significance threshold was set at .

For external validation, we computed 95% confidence intervals using bootstrapping with 1000 iterations to quantify uncertainty in performance estimates. All statistical analyses were performed using SciPy and statsmodels Python libraries.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the two datasets after preprocessing and quality control.

Both datasets showed approximate class balance (ratio near 1.0), reducing concerns that observed performance differences are driven by class imbalance artifacts. The ASZED-153 dataset provided substantially more epochs per subject, reflecting longer recording durations in the original protocol.

3.2. Internal Cross-Validation Performance

Table 2 presents the internal 5-fold cross-validation results on the ASZED-153 dataset, representing the performance that would be expected when models are evaluated on data from the same distribution as the training set.

EEGNet outperformed Random Forest on most metrics during internal cross-validation. The accuracy difference of 3.9 percentage points was statistically significant (, paired t-test across folds, Cohen’s , indicating a large effect size). EEGNet achieved higher sensitivity (better identification of schizophrenia patients) while Random Forest showed slightly higher specificity (better identification of healthy controls).

Both models demonstrated moderate discrimination ability (AUC: 0.78–0.81), consistent with the challenging nature of EEG-based psychiatric classification and the heterogeneity inherent in schizophrenia. The relatively modest standard deviations across folds (3.6–4.0% for accuracy) indicate reasonable stability, though some variability is expected given the relatively small dataset size and subject-level cross-validation.

3.3. Per-Fold Analysis

Table 3 presents detailed per-fold accuracy for both models, demonstrating consistency of results across folds and revealing fold-specific variations.

EEGNet outperformed or matched Random Forest in 4 out of 5 folds, with the exception of Fold 1 where performance was nearly identical. The performance variation across folds (range: 64.5–75.5% for EEGNet; 62.3–72.0% for Random Forest) reflects inherent heterogeneity in the data and subject-specific factors. Fold 4 showed lowest performance for both models, potentially indicating a subset of subjects with atypical EEG patterns or more ambiguous clinical presentations.

3.4. External Dataset Generalization

Table 4 presents performance on the independent external dataset (Kaggle Schizophrenia EEG), revealing substantial generalization challenges for both approaches.

Both models exhibited severe performance degradation on the external dataset:

EEGNet: Accuracy dropped from 70.7% (internal CV) to 54.6% (external), representing a generalization gap of 16.1 percentage points. AUC declined from 0.814 to 0.529 (essentially chance level for binary classification). Notably, EEGNet developed extreme bias toward predicting schizophrenia (sensitivity 87.5%, specificity 16.6%), correctly identifying most patients but misclassifying most controls.

Random Forest: Accuracy dropped from 66.8% to 45.4% (generalization gap: 21.4 percentage points). AUC of 0.424 indicates performance below chance level, suggesting systematic misclassification. Random Forest showed more balanced predictions than EEGNet but still far below acceptable clinical performance.

RF + CORAL: Domain adaptation provided marginal improvement (1.2 percentage points accuracy increase, AUC improvement from 0.424 to 0.470). CORAL dramatically altered the classifier’s decision boundary, flipping from high sensitivity (60.2%) to high specificity (79.2%), but overall discrimination remained poor. This suggests that simple covariance alignment is insufficient to address the complex domain shift between these datasets.

The external performance approaching or below chance level (50% accuracy, 0.50 AUC for balanced binary classification) indicates that both models learned features specific to the ASZED-153 dataset rather than generalizable signatures of schizophrenia.

3.5. Generalization Gap Analysis

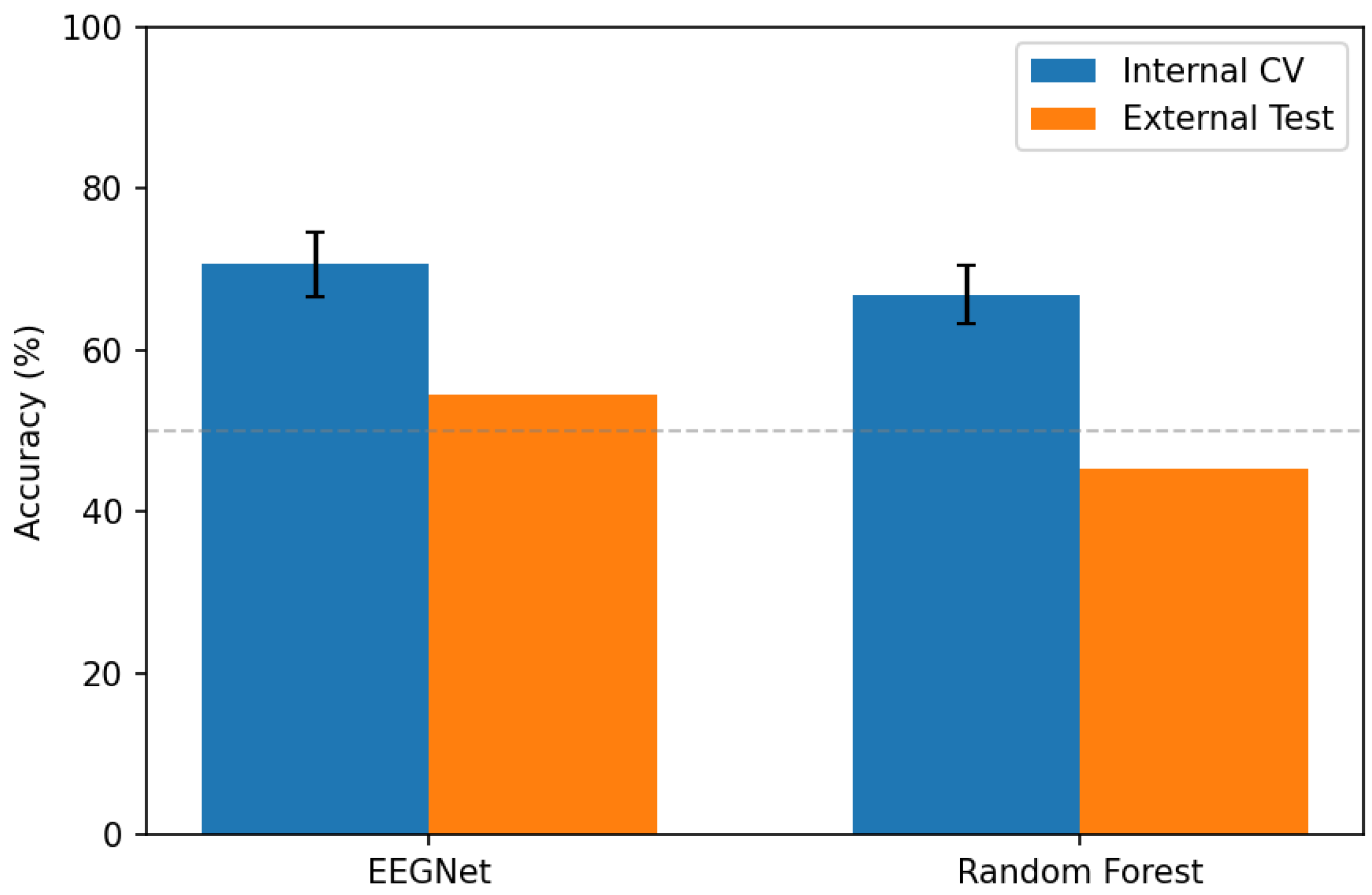

Figure 1 illustrates the dramatic performance degradation from internal validation to external testing, visualizing the generalization gap.

The generalization gap far exceeded the internal cross-validation standard deviation for both models:

This indicates that cross-validation variance substantially underestimates the uncertainty associated with deployment on new data sources. The fold-to-fold variability observed during cross-validation (4%) captures subject heterogeneity within a single dataset but fails to capture the much larger variability introduced by changing acquisition sites, equipment, and protocols.

3.6. Domain Shift Analysis

MMD analysis quantitatively confirmed substantial distribution shift between the ASZED-153 and external datasets:

The original MMD value of 0.0914 is well above the threshold of 0.05 typically indicating meaningful distributional differences, providing quantitative confirmation of the domain shift suspected from the performance degradation. This value is computed on PCA-reduced spectral features and represents the distance between dataset distributions in a high-dimensional feature space.

CORAL reduced MMD by only 7.8%, and this modest reduction in distribution distance did not translate to substantial performance improvement (1.2 percentage points). This suggests that: (1) the domain shift involves higher-order distributional differences beyond second-order statistics (covariance), (2) concept shift (different feature-label relationships across datasets) may be present, or (3) the magnitude of shift is too large for simple alignment techniques to overcome.

3.7. ROC Curve Analysis

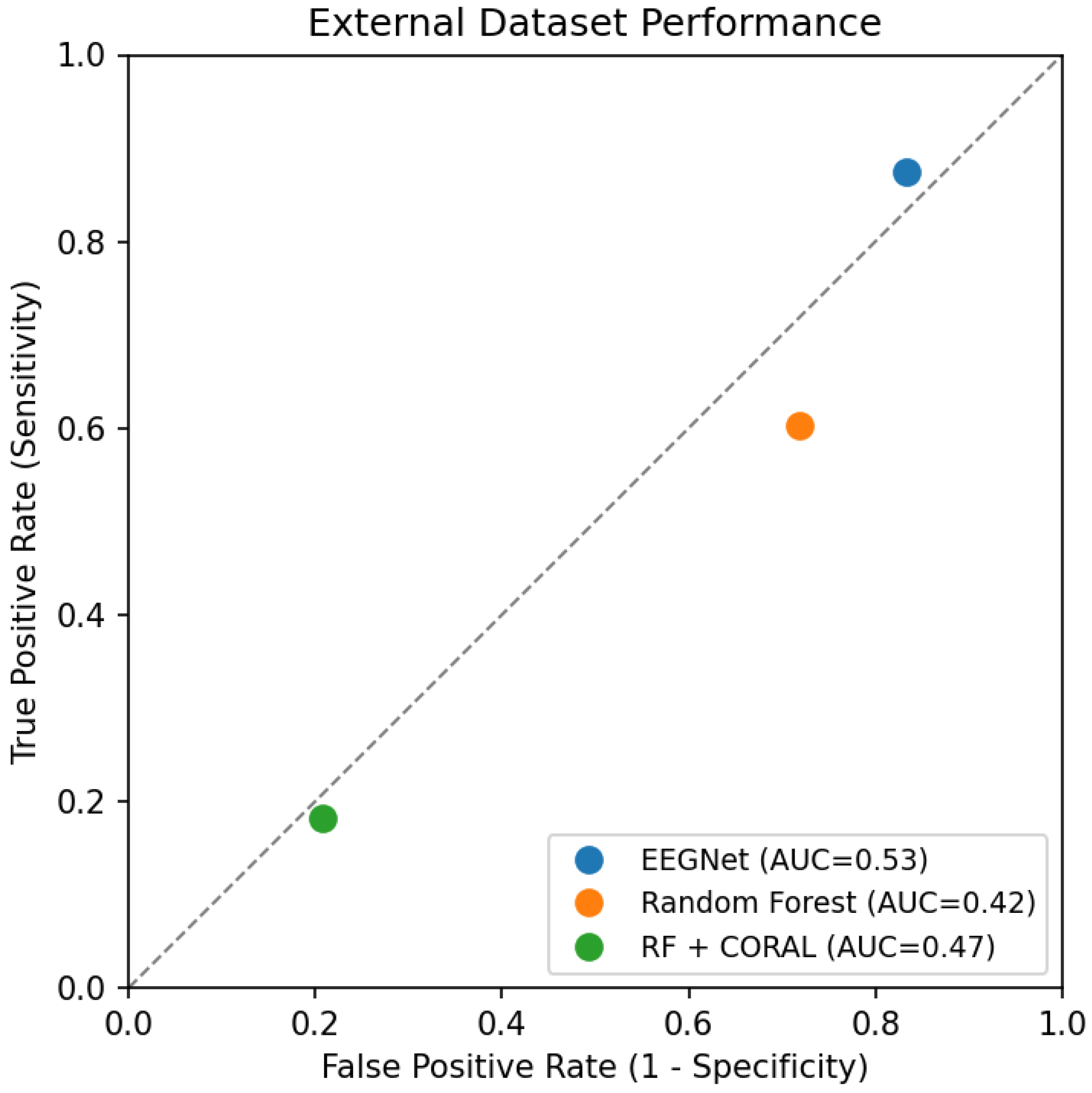

Figure 2 presents ROC curves for external evaluation, visualizing the severe discrimination degradation and comparing all three approaches.

The external ROC curves are dramatically degraded compared to internal validation (not shown, but AUCs of 0.78–0.81). All curves approach or cross the diagonal reference line, indicating discrimination ability near or below random guessing. The single-point representations show the extreme trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity:

EEGNet prioritizes sensitivity (87.5%) at the cost of specificity (16.6%)

Random Forest shows moderate sensitivity (60.2%) and poor specificity (28.2%)

CORAL flips the trade-off, achieving reasonable specificity (79.2%) but very low sensitivity (18.2%)

None of these operating points would be clinically acceptable, as they either miss most patients (CORAL) or incorrectly label most healthy individuals as patients (EEGNet), both with serious clinical and ethical consequences.

3.8. Calibration Analysis

Probability calibration quality degraded substantially on the external dataset, indicating that models not only misclassify but also express unreliable confidence levels:

EEGNet: Brier score increased from 0.213 (internal) to 0.350 (external), and ECE increased from approximately 0.15 (estimated from internal folds) to 0.205

Random Forest: Brier score increased from 0.211 to 0.261, and ECE increased from approximately 0.19 to 0.266

These increases indicate that predicted probabilities became unreliable on external data, with models expressing confidence levels (predicted probabilities) that do not align with actual classification accuracy. This calibration failure is particularly problematic for clinical deployment, where probability estimates would inform clinical decision-making and risk assessment. A miscalibrated model may express high confidence in incorrect predictions, leading clinicians to trust erroneous classifications.

3.9. Feature Importance Analysis

Table 5 presents the top 10 most important features for the Random Forest classifier, providing insight into which EEG characteristics drove classification decisions during training.

Alpha band power in posterior regions (parietal and occipital electrodes: Pz, O1, O2, P3, P4) dominated feature importance, with the top 5 features accounting for substantial discriminative power. This is consistent with the extensive literature documenting alpha rhythm abnormalities in schizophrenia [

4], including reduced alpha power, altered alpha peak frequency, and disrupted alpha-band connectivity.

However, the failure of these well-established features to generalize suggests several possible explanations: (1) alpha power differences between groups may not be consistent across datasets due to differences in patient populations, medication status, or clinical heterogeneity, (2) the classifier may have learned dataset-specific confounds correlated with alpha power in the ASZED-153 training data (e.g., specific recording equipment characteristics, systematic differences in electrode impedance), or (3) the alpha abnormalities may be subtle and easily obscured by differences in recording conditions and preprocessing.

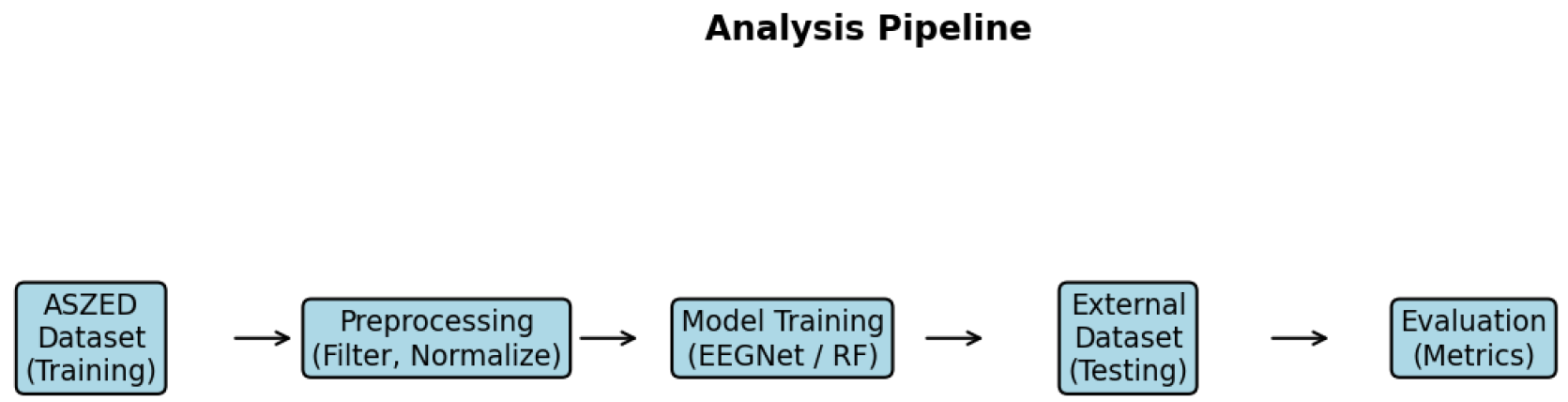

3.10. Analysis Pipeline

Figure 3 provides a visual overview of the complete analysis pipeline from data acquisition through evaluation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

This study compared EEGNet and Random Forest for schizophrenia EEG classification with rigorous external validation on an independent dataset acquired under different conditions. Key findings include:

EEGNet outperformed Random Forest during internal cross-validation on ASZED-153 (70.7% vs. 66.8% accuracy, , Cohen’s ), demonstrating that deep learning can achieve superior within-dataset performance for EEG-based psychiatric classification.

Both approaches exhibited severe generalization difficulty on the external Kaggle dataset (EEGNet: 54.6%, Random Forest: 45.4%), with performance degrading to near or below chance level. These results represent generalization gaps of 16–21 percentage points.

CORAL domain adaptation provided marginal improvement (1.2 percentage points for Random Forest, AUC improvement from 0.424 to 0.470) but did not approach internal validation performance levels or achieve clinically acceptable discrimination.

MMD analysis quantitatively confirmed substantial domain shift between datasets (MMD = 0.0914, well above the 0.05 threshold for meaningful difference).

The generalization gap far exceeded internal cross-validation variance (4–6× larger), indicating that CV-based performance estimates are overly optimistic and do not predict external performance.

Both models showed severe miscalibration on external data, with probability estimates becoming unreliable (ECE increased from ∼0.15–0.19 to 0.21–0.27).

4.2. Interpretation of Generalization Results

The severe performance degradation from internal validation to external testing—16.1 percentage points for EEGNet and 21.4 percentage points for Random Forest—represents a critical finding with important implications for the field.

4.2.1. Architecture Comparison: Deep Learning vs. Classical Machine Learning

Both EEGNet (deep learning) and Random Forest (classical machine learning) showed comparable generalization difficulty, with performance degrading to near-chance levels on external data. This pattern suggests that the fundamental challenge relates to dataset heterogeneity and the learning of site-specific features rather than the choice of learning algorithm or architectural paradigm (deep learning vs. classical ML).

The similarity of generalization failure across both approaches implies that solutions will require addressing data collection, harmonization, and study design rather than purely algorithmic innovation. While EEGNet demonstrated superior within-dataset performance, this advantage completely disappeared when models encountered data from a different acquisition site. This finding challenges the notion that deep learning’s ability to learn hierarchical representations automatically confers better generalization in the presence of domain shift.

4.2.2. Potential Sources of Domain Shift

The observed MMD value (0.0914) quantitatively confirms substantial distributional differences between the ASZED-153 and Kaggle datasets. Multiple factors likely contribute to this domain shift:

Recording Equipment Differences: ASZED-153 and Kaggle datasets were acquired with different EEG systems, introducing systematic hardware-related differences. Different amplifier characteristics, electrode types (passive vs. active), input impedance specifications, common-mode rejection ratios, and analog-to-digital conversion properties create systematic biases in recorded signals. Classifiers may learn these hardware signatures as “features” that correlate with class labels in the training data but do not generalize to different hardware.

Protocol and Environmental Variations: Differences in recording protocols (exact instructions to subjects, level of supervision, duration, number of recordings per subject), environmental factors (ambient noise levels, time of day, room lighting), and subject state (alertness, anxiety level, caffeine consumption) affect EEG characteristics systematically across sites. Resting-state recordings are particularly sensitive to subject state and environmental factors.

Population and Clinical Heterogeneity: ASZED-153 includes adult African populations, while the Kaggle dataset contains adolescent subjects of unspecified ethnicity. Age-related differences in EEG patterns (adolescents show different spectral characteristics than adults), demographic factors, cultural differences in response to experimental procedures, and differences in illness characteristics (age of onset, symptom severity, duration) introduce systematic variations. Additionally, medication status (type, dosage, polypharmacy, compliance) is unknown for both datasets but likely differs systematically.

Diagnostic Assessment Heterogeneity: Differences in how schizophrenia diagnosis was established (specific diagnostic criteria used, diagnostic instruments, clinician training and experience, threshold for diagnosis, inclusion/exclusion criteria) may lead to heterogeneity in patient groups across datasets. The Kaggle dataset includes “adolescents exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia,” which may include prodromal cases, first-episode psychosis, or attenuated psychosis syndrome—populations with potentially different EEG characteristics than chronic schizophrenia patients.

Artifact and Noise Characteristics: Different recording environments and subject populations produce different types and levels of artifacts. Muscle artifacts, eye movements, and electrode artifacts may have different statistical properties across datasets, and classifiers trained with one artifact profile may fail when encountering different artifact patterns.

4.2.3. Implications for the Field

These findings have several critical implications for EEG-based psychiatric classification research:

External Validation is Essential: Internal cross-validation alone, while scientifically valid for algorithmic comparison and model selection, does not provide adequate evidence of real-world generalization or clinical readiness. Studies reporting high accuracy based solely on internal validation should be interpreted cautiously regarding clinical applicability. The field should establish standards requiring external validation on multiple independent datasets before claims of clinical utility are advanced.

Publication of Generalization Failures: The field benefits from transparent reporting of generalization failures and negative results. Publication bias favoring positive results creates an unrealistic impression of technology readiness, delays identification of fundamental challenges, and may lead to premature clinical deployment attempts. Our findings join a growing body of work documenting cross-dataset generalization challenges in medical AI.

Multi-Site Training Data May Be Necessary: Single-site training data may be fundamentally insufficient for developing clinically deployable classifiers. Successful translation likely requires multi-site training to learn features that generalize across acquisition conditions rather than site-specific patterns. This necessitates large-scale collaborative efforts and data-sharing initiatives, which face substantial logistical, regulatory, and financial challenges.

Rethinking Performance Benchmarks: The community should reconsider how classifier performance is evaluated and reported. Reporting only internal CV performance without external validation provides an incomplete and potentially misleading picture. We recommend that papers report both internal CV performance (for within-dataset comparisons) and external validation performance (for generalization assessment), clearly distinguishing between these two evaluation modes.

4.3. Limitations of Domain Adaptation

CORAL domain adaptation provided limited benefit in our experiments (1.2 percentage point accuracy improvement, AUC improvement of 0.046), far short of closing the generalization gap. Several factors may explain this limited efficacy:

Limited Statistical Alignment: CORAL aligns only second-order statistics (covariance matrices). Higher-order distributional differences (skewness, kurtosis, multimodal structures) and complex nonlinear relationships remain unaddressed. If the domain shift involves these higher-order patterns, second-order alignment is insufficient.

Potential Concept Shift: If the feature-label relationship differs between datasets (e.g., if alpha power has different diagnostic significance across sites due to population differences or if different EEG features are relevant in different populations), covariance alignment cannot resolve this mismatch. CORAL assumes that class-conditional distributions differ between domains but the underlying discriminative structure is preserved—an assumption that may not hold for psychiatric EEG classification across diverse populations.

Magnitude of Shift: The large MMD value (0.0914) and dramatic performance degradation suggest a domain shift too severe for simple alignment techniques. CORAL reduced MMD by only 7.8%, indicating that most of the distributional difference remains after alignment.

Feature Relevance: If the important features for classification differ between datasets (e.g., different frequency bands or channels carry diagnostic information), aligning feature distributions will not help if the model is attending to the wrong features for the target domain.

These limitations suggest that more sophisticated domain adaptation approaches may be needed, including deep domain adaptation methods (domain-adversarial neural networks, maximum mean discrepancy networks), test-time adaptation, or meta-learning approaches that explicitly optimize for cross-domain generalization.

4.4. Comparison with Literature

Our internal cross-validation results (70.7% for EEGNet, 66.8% for Random Forest) are consistent with reported accuracies of 70–85% in EEG-based schizophrenia classification studies [

6]. Many published studies report similar or higher accuracy using various methods (support vector machines, deep learning architectures, ensemble methods) on single datasets.

However, the vast majority of published studies rely exclusively on internal validation without external testing on independent datasets acquired under different conditions. This makes direct comparison of generalization performance difficult or impossible. To our knowledge, very few studies have systematically evaluated cross-dataset generalization for schizophrenia EEG classification, though similar challenges have been documented in other EEG-based classification tasks (seizure detection, sleep staging, emotion recognition).

The consistency of our internal validation results with the published literature, combined with severe external generalization failure, raises the hypothesis that many published high-accuracy results may similarly fail to generalize to new sites and populations. This hypothesis warrants systematic investigation through large-scale replication studies with external validation, potentially organized through collaborative initiatives or competitions with held-out external test sets.

4.5. Toward Improved Generalization

Several promising directions may improve cross-dataset generalization for EEG-based psychiatric classification:

4.5.1. Multi-Site Training Data and Federated Learning

Training on data pooled from multiple recording sites, protocols, equipment types, and populations may help models learn features that are consistent across acquisition conditions rather than site-specific artifacts. Exposure to diverse data during training may improve robustness through implicit regularization and force models to learn invariant features.

Federated learning approaches [

13] could enable multi-site model development while preserving data privacy and navigating regulatory constraints. In federated learning, models are trained locally at each site, and only model updates (not raw data) are shared and aggregated. This approach could address privacy concerns while enabling collaborative model development.

4.5.2. Data Harmonization and Standardization

The field would benefit from standardized data collection and sharing protocols including:

Standardized recording protocols (electrode montages, recording duration, instructions to subjects, environmental conditions)

Comprehensive metadata reporting (equipment specifications, software versions, electrode types, impedance levels, medication status, illness characteristics)

Standardized preprocessing pipelines with open-source implementations and detailed documentation

Quality control metrics and standardized artifact rejection criteria

Common data formats and naming conventions

Initiatives like BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) for EEG could facilitate data sharing and harmonization efforts.

4.5.3. Domain-Invariant and Meta-Learning Approaches

Advanced machine learning techniques specifically designed for domain shift may offer improvements:

Domain-adversarial neural networks [

14]: Train networks to learn features that are predictive of diagnosis but uninformative about data source (site), explicitly optimizing for domain invariance

Invariant risk minimization (IRM): Identify features with stable predictive relationships across multiple environments (datasets), focusing on causal rather than correlational features

Meta-learning (learning to learn): Train models on multiple datasets/domains with the explicit objective of rapid adaptation to new domains with limited data

Test-time adaptation: Adjust model parameters at test time using unlabeled target domain data to adapt to distributional shift without requiring target labels

These approaches require more complex training procedures and larger, more diverse datasets but may offer paths toward robust cross-site generalization.

4.5.4. Physiologically-Informed and Hybrid Approaches

Rather than relying purely on data-driven learning, incorporating established neuroscience knowledge may improve robustness:

Focus on features with known physiological interpretations and documented relevance to schizophrenia pathophysiology

Use biophysical models to generate “synthetic” training data covering diverse acquisition conditions

Hybrid approaches combining data-driven feature learning with neuroscience-informed priors

Incorporate known invariances (e.g., certain spectral ratios may be more robust than absolute power)

However, our feature importance analysis suggests that even established features (alpha power) failed to generalize, indicating that this approach alone may be insufficient without addressing the underlying data heterogeneity.

4.5.5. Low-Cost Hardware for Accessible EEG Acquisition

Our pilot exploration with the BioAmp EXG Pill demonstrates the feasibility of low-cost, open-source EEG acquisition. Scaling this approach to 16 channels would enable a complete EEG system for approximately $300 (16 BioAmp units + ESP32 + accessories), compared to $10,000–$50,000 for clinical-grade systems.

Potential benefits:

Enables large-scale data collection in resource-constrained settings (low- and middle-income countries, rural areas, community mental health settings)

Increases diversity of training data through broader geographical and demographic sampling

Facilitates home-based or ambulatory EEG recording for longitudinal monitoring

Reduces barriers to EEG research in underrepresented populations

Challenges and future work:

Signal quality validation: Systematic comparison with clinical-grade systems needed

Standardization: Developing standardized acquisition protocols for low-cost hardware

Regulatory pathway: Understanding regulatory requirements for clinical use

Generalization across hardware types: Whether models trained on clinical-grade EEG generalize to low-cost systems (and vice versa) requires investigation

Future work should systematically evaluate classification performance using low-cost hardware and investigate whether diversity in recording equipment during training (mixing low-cost and clinical-grade data) improves hardware-invariant feature learning.

4.6. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting results:

Limited Dataset Diversity: Our study utilized two datasets from specific research groups and regions. Generalization to other datasets, populations, geographic regions, and clinical settings cannot be assumed. Evaluation on additional external datasets representing diverse populations, ages, illness stages, and recording conditions would strengthen conclusions about the generality of our findings.

Residual Preprocessing Differences: Despite our efforts to apply harmonized preprocessing, we cannot fully exclude residual preprocessing-related differences between datasets. Ideal evaluation would use data collected with identical protocols and equipment, or use raw unprocessed data with all preprocessing performed in-house.

Limited Architectural Diversity: We compared one deep learning architecture (EEGNet) against one classical approach (Random Forest with isotonic calibration). Other architectures (recurrent neural networks, transformers, more complex CNNs, other ensemble methods) might demonstrate different generalization characteristics. However, we hypothesize similar challenges would emerge given that the fundamental issue is dataset heterogeneity rather than architecture choice.

Single External Dataset: Generalization was evaluated on one external dataset. Evaluation on multiple independent external datasets from diverse sources would provide more robust assessment of generalization capability and help identify which factors most impact cross-site performance.

Incomplete Clinical Metadata: Limited availability of detailed clinical metadata (medication specifics, symptom profiles, illness duration, functional status) for both datasets restricted our ability to investigate whether clinical heterogeneity contributes to generalization failure. Rich clinical phenotyping would enable more nuanced analysis of generalization across different patient subgroups.

Resting-State Focus: We utilized only resting-state EEG data. Task-based paradigms (cognitive tasks, auditory oddball, emotional face processing) or event-related potential approaches might offer different generalization characteristics, as task-evoked responses may be more stereotyped across individuals and sites.

Binary Classification: We focused on binary classification (schizophrenia vs. healthy controls). Real-world clinical deployment would require discrimination from other psychiatric and neurological conditions (bipolar disorder, depression, epilepsy), which presents additional challenges.

4.7. Recommendations for Future Research

Based on our findings and the current state of the field, we recommend:

Mandatory External Validation: Journals and conferences should require external validation on at least one independent dataset for studies claiming clinical utility or readiness of EEG-based diagnostic classifiers. Reporting standards should clearly distinguish between internal CV performance (for methodological comparison) and external validation performance (for generalization assessment).

Multi-Site Consortia: Establish multi-site research consortia with standardized protocols for EEG data collection, quality control, and phenotypic characterization in psychiatric populations. Such consortia could create benchmark datasets with held-out external test sets for fair comparison of methods.

Public Benchmark Datasets: Develop standardized, multi-site benchmark datasets with comprehensive metadata, rigorous quality control, and held-out test sets for evaluating cross-site generalization of psychiatric EEG classifiers. These benchmarks would enable fair comparison of methods and track progress over time.

Transparency in Negative Results: Strongly encourage publication of studies demonstrating generalization failures and negative results. These contributions provide realistic assessment of current technology readiness, identify fundamental challenges requiring solutions, and prevent wasteful duplication of failed approaches.

Shift Focus to Robustness: Redirect research emphasis from maximizing single-dataset accuracy to developing methods that maintain reasonable performance across diverse acquisition conditions. Generalization robustness, not peak performance, should be the primary metric for clinical translation.

Investigate Failure Modes: Systematic investigation of which factors most impact generalization (equipment type, protocol differences, population characteristics, clinical heterogeneity) through carefully controlled experiments varying one factor at a time.

Develop Generalization Metrics: Establish standardized metrics for quantifying and reporting generalization performance, such as average performance across multiple external datasets, worst-case performance across datasets, or generalization gap (internal - external performance).

5. Conclusions

Both EEGNet and Random Forest demonstrated severe generalization difficulty when applied to an external schizophrenia EEG dataset acquired under different conditions, with performance degrading to near or below chance levels despite achieving reasonable internal cross-validation performance on ASZED-153. The generalization gap of approximately 16–21 percentage points—far exceeding internal cross-validation variance—indicates that current EEG-based classification methods do not readily transfer across datasets collected under different conditions, equipment, and protocols.

Key implications include:

External validation is essential and non-negotiable: Internal cross-validation, while scientifically valid for methodological comparisons, does not provide adequate evidence of clinical utility or real-world applicability. Studies relying solely on internal validation should be interpreted cautiously regarding readiness for clinical deployment.

Architectural sophistication alone is insufficient: The similarity of generalization failure between deep learning (EEGNet) and classical machine learning (Random Forest) suggests that the challenge lies primarily in dataset heterogeneity and site-specific feature learning rather than algorithmic limitations. Solutions will require addressing data collection, harmonization, and study design.

Current methods are not deployment-ready: Performance approaching chance level on external data definitively indicates that existing approaches require substantial development before clinical deployment is appropriate. Claims of clinical readiness should require rigorous multi-site external validation.

Multi-site training is likely necessary: Single-site training data may be fundamentally inadequate for developing robust, generalizable classifiers suitable for clinical use across diverse healthcare settings. Large-scale collaborative efforts are needed.

Transparent reporting of negative results is valuable: This work contributes to realistic assessment of technology readiness by transparently documenting generalization failures. Such contributions, though reporting negative findings, provide essential scientific value by identifying fundamental challenges and preventing premature clinical deployment attempts.

This research explores computational methods for EEG pattern analysis in controlled research settings and has not been validated for clinical diagnostic use. Future research should prioritize developing approaches that demonstrably generalize across recording conditions, populations, and sites through multi-site training data, standardized acquisition protocols, domain-invariant learning techniques, and rigorous multi-site external validation. Until such robust methods are developed and validated across diverse independent datasets representing real-world clinical diversity, claims of clinical readiness should be advanced with appropriate scientific caution.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted using two publicly available and de-identified EEG datasets. All data collection for the original datasets was performed in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines and with informed consent from all participants or their legal guardians. As this study involved only secondary analysis of fully anonymized, publicly available data with no possibility of re-identification, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4) for research involving existing de-identified data. Both datasets were collected with appropriate ethical approval from their originating institutions, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. All data were de-identified prior to our access, and no protected health information (PHI) or personally identifiable information (PII) was available to the research team.

Data Availability Statement: ASZED-153 Dataset (Training)

The African Schizophrenia EEG Dataset (ASZED-153) used for model training and internal validation is publicly available at Zenodo:

https://zenodo.org/records/14178398. This dataset contains 153 raw 16-channel EEG recordings from 76 schizophrenia patients and 77 healthy controls across multiple tasks (resting state, cognitive, auditory), aimed at increasing representation of African populations in schizophrenia research.

External Validation Dataset (Testing): The Kaggle EEG Schizophrenia dataset by kacharepramod, used for external validation, is publicly available at:

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kacharepramod/eeg-schizophrenia. This dataset contains EEG recordings from 84 subjects (39 healthy adolescents and 45 adolescents exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia) and is designed for machine learning research on distinguishing these groups.

Code Availability: All preprocessing scripts, model implementations, and analysis code used in this study are publicly available at GitHub:

https://github.com/sameekshya1999/-Schizophrenia-Detection-from-EEG/. The repository includes complete documentation to facilitate replication of our methods and support reproducibility in EEG-based psychiatric biomarker research.

Processed Data: Due to the large size of preprocessed EEG data, processed datasets are not publicly deposited. However, we provide complete methodological details in the Materials and Methods section to enable reproduction of our preprocessing pipeline from the original publicly available datasets.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Dr. Liqiang Zhang (Indiana University South Bend) for valuable guidance and insightful discussions throughout this research, particularly regarding the low-cost hardware exploration. We thank the original data collectors and contributors of the ASZED-153 dataset and the Kaggle Schizophrenia EEG dataset for making their data publicly available for research purposes. We acknowledge the importance of open data sharing for advancing reproducible science in computational psychiatry.

References

- Tandon, R., Nasrallah, H.A., Keshavan, M.S. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4. Clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophrenia Research, 110(1-3):1–23, 2009.

- Marshall, M., Lewis, S., Lockwood, A., Drake, R., Jones, P., Croudace, T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9):975–983, 2005.

- Boutros, N.N., Arfken, C., Galderisi, S., Warrick, J., Pratt, G., Iacono, W. The status of spectral EEG abnormality as a diagnostic test for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 99(1-3):225–237, 2008.

- Newson, J.J., Thiagarajan, T.C. EEG frequency bands in psychiatric disorders: a review of resting state studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12:521, 2019.

- Uhlhaas, P.J., Singer, W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2):100–113, 2010.

- Santos-Mayo, L., San-Jose-Revuelta, L.M., Arribas, J.I. A computer-aided diagnosis system with EEG based on the P3b wave during an auditory odd-ball task in schizophrenia. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 64(2):395–407, 2020.

- Craik, A., He, Y., Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: a review. Journal of Neural Engineering, 16(3):031001, 2019.

- Lawhern, V.J., Solon, A.J., Waytowich, N.R., Gordon, S.M., Hung, C.P., Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering, 15(5):056013, 2018.

- Sun, B., Feng, J., Saenko, K. Return of frustratingly easy domain adaptation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 30(1), 2016.

- ASZED-153: African Schizophrenia EEG Dataset. Zenodo, 2024. https://zenodo.org/records/14178398.

- Niculescu-Mizil, A., Caruana, R. Predicting good probabilities with supervised learning. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 625–632, 2005.

- Gretton, A., Borgwardt, K.M., Rasch, M.J., Schölkopf, B., Smola, A. A kernel two-sample test. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 13:723–773, 2012.

- Rieke, N., Hancox, J., Li, W., Milletari, F., Roth, H.R., Albarqouni, S., et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1):119, 2020.

- Ganin, Y., Ustinova, E., Ajakan, H., Germain, P., Larochelle, H., Laviolette, F., Marchand, M., Lempitsky, V. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 17(1):2096–2030, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).