10. Calculation of the Construction Period Based on the Volume Eroded at Each Point

Points of analysis in the G1 pyramid of Akhet Khufu

At analysis point no. 1 on the Pyramid of Khufu, I calculated the relative erosion of the surface characterised by pronounced roughness and pitting-type erosion by estimating the volume of the eroded recesses. This was done by taking measurements at closely spaced points, some of which had been exposed to erosive agents since the time of construction, and others that were exposed only after the removal of the limestone facing blocks.

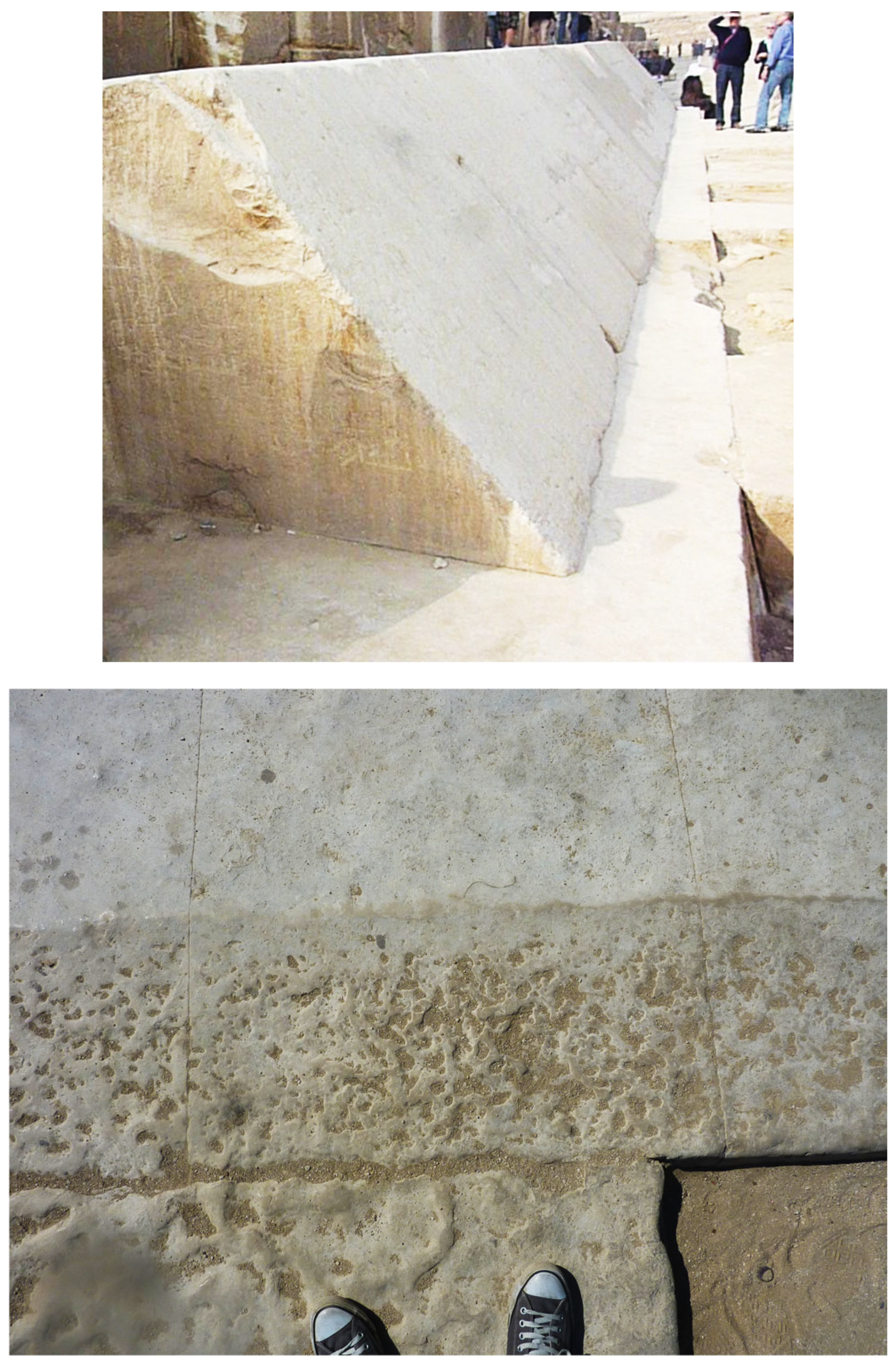

Figure 8 and 9.

Figure 8. Detail of the Pyramid of Khufu at point 1. On the left are the only remaining limestone cladding blocks, and on the right is the clear difference in erosion between the lower part (which has been exposed since the pyramid was built) and the upper part (which has only been exposed to erosive agents for 675 years).

Figure 8 and 9.

Figure 8. Detail of the Pyramid of Khufu at point 1. On the left are the only remaining limestone cladding blocks, and on the right is the clear difference in erosion between the lower part (which has been exposed since the pyramid was built) and the upper part (which has only been exposed to erosive agents for 675 years).

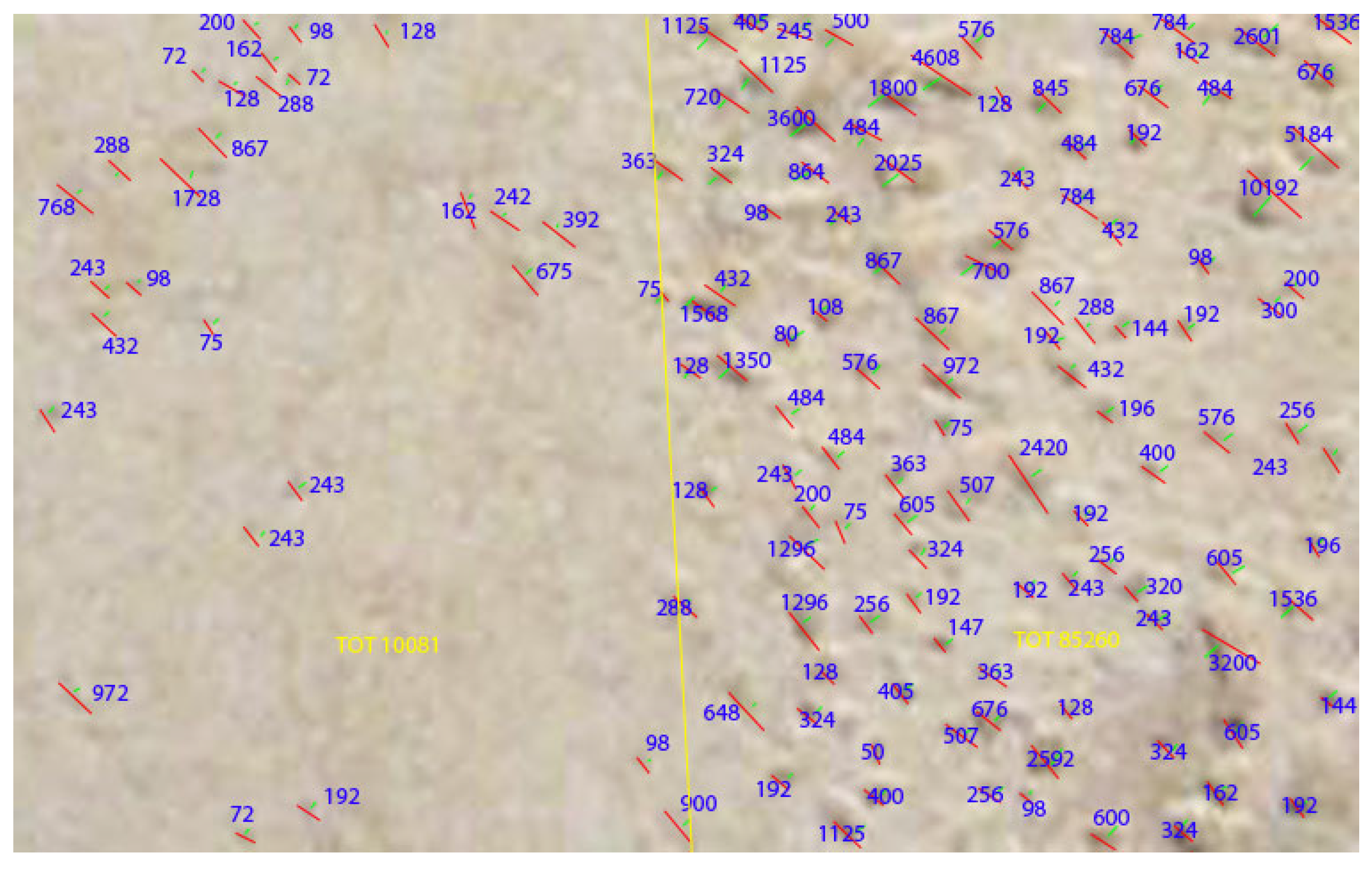

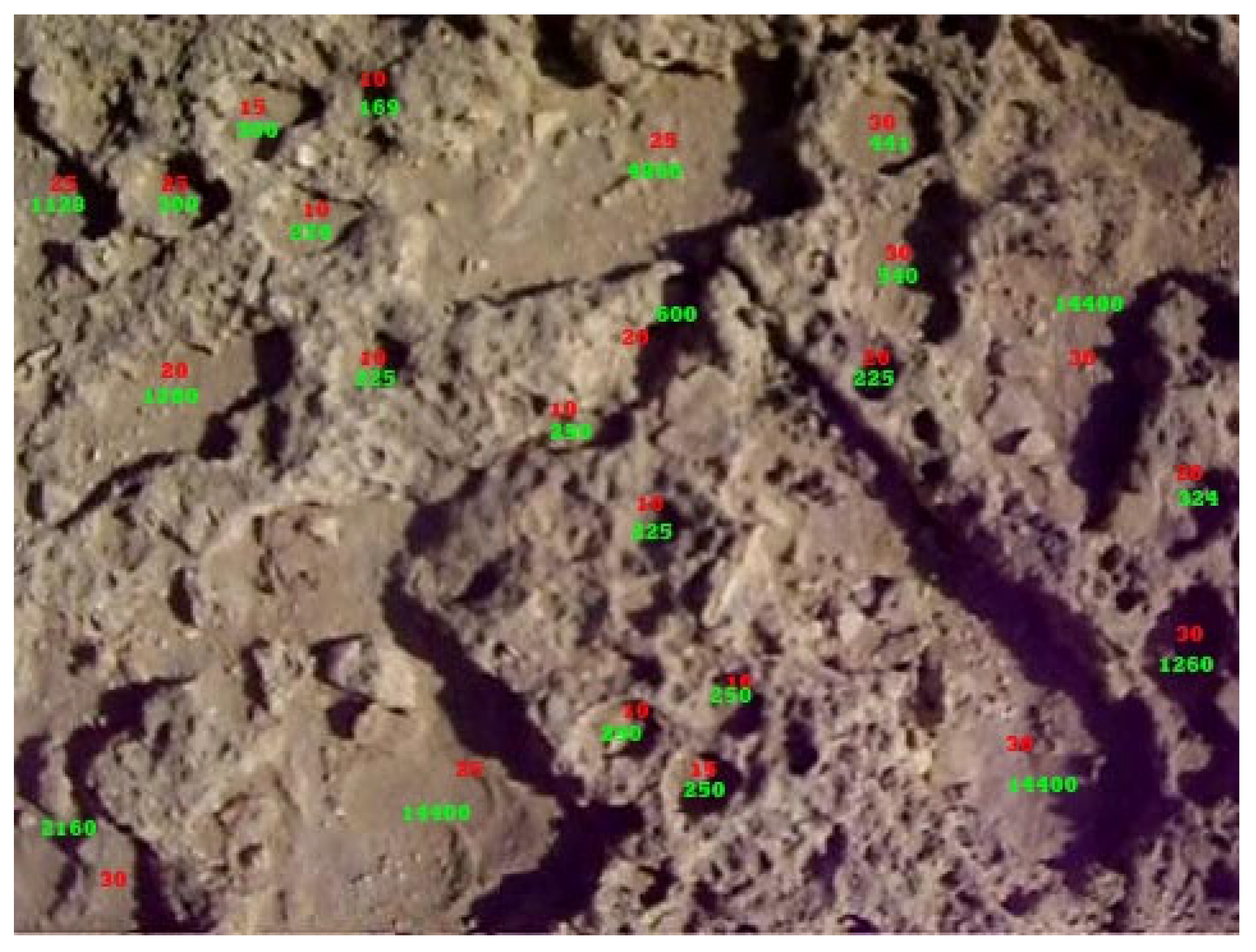

Figure 10.

Calculation of erosion (volume of holes) at point 1: on the left, the part of the limestone paving exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years; on the right, the part exposed since the time of construction.

Figure 10.

Calculation of erosion (volume of holes) at point 1: on the left, the part of the limestone paving exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years; on the right, the part exposed since the time of construction.

In this image, I calculated the volume, expressed in mm3, of each erosion cavity, and then the total volume of eroded rock at point 1. The right-hand side has been exposed to erosive agents since the beginning of construction, while the left-hand side has been exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years.

Calculation of the construction period based on the volume of eroded recesses at Point 1 (Khufu)

Total volume of eroded recesses in the continuously exposed section: 85,260 mm³

Total volume of eroded recesses exposed since 675 years B.P.: 10,081 mm³

Estimated construction date: 85,260 × 675 / 10,081 = 5,708 years B.P. [

6]

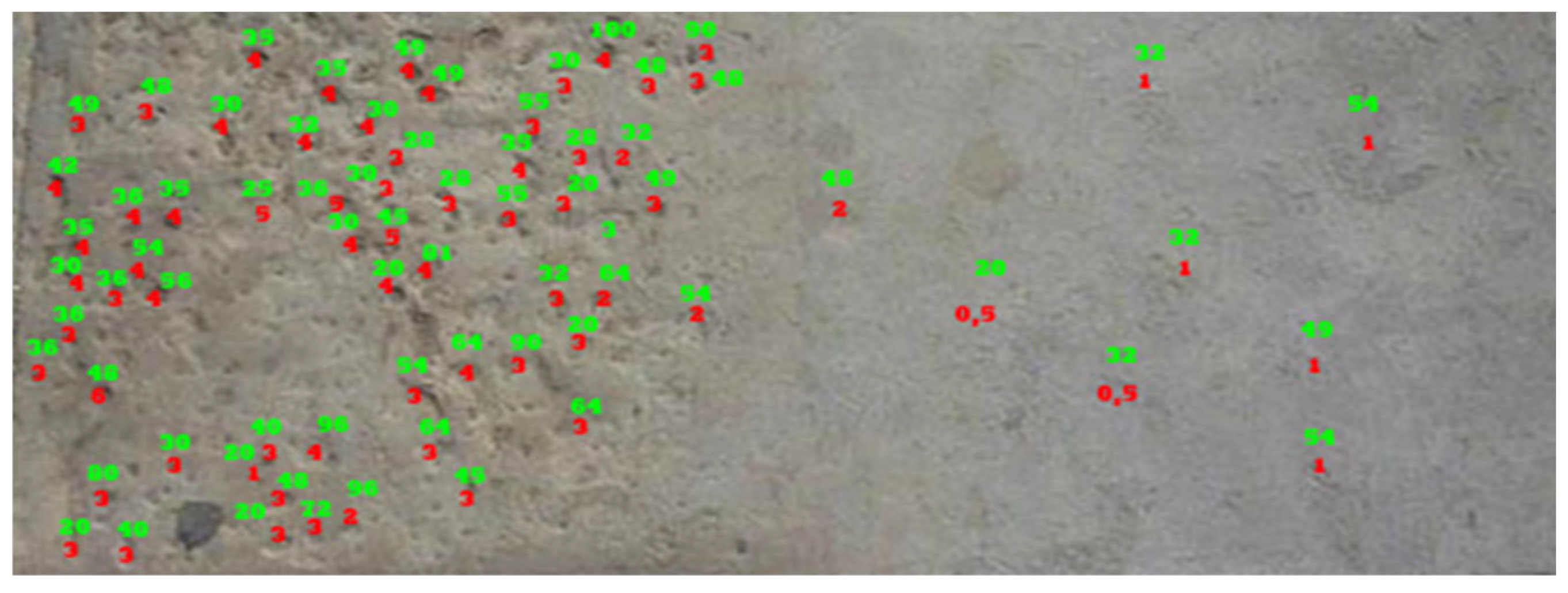

Figure 11.

Calculation of erosion (volume of holes) in point 2: on the right, the part of the limestone pavement exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years; on the left, the part exposed since the time of construction.

Figure 11.

Calculation of erosion (volume of holes) in point 2: on the right, the part of the limestone pavement exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years; on the left, the part exposed since the time of construction.

In this image, the area (highlighted in green) and the depth (highlighted in red) of each recess were calculated and expressed in square millimetres and millimetres, respectively. The total volume of eroded rock at analysis point 2 was then determined. The left-hand side corresponds to the surface that has been exposed to erosive agents since the time of construction, whereas the right-hand side represents the surface that has been exposed to erosive agents for approximately 675 years.

Calculation of construction period based on volume of eroded recesses, point 2 Khufu

Total volume of eroded recesses in exposed part: 9,124 mm3

Total volume of eroded recesses in exposed part 675 years B.P.: 343 mm3

Date of construction: 9,124 x 675 / 343 = 17,955 years B.P.

At point 3, I measured the average erosion of the pyramid paving immediately outside the area formerly covered by the removed casing blocks, and compared it with the average erosion of the paving that lay beneath the removed cladding.

Figure 12 and 13.

Wear of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 3.

Figure 12 and 13.

Wear of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 3.

Figure 14.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks in point 3, highlighted in the red rectangle.

Figure 14.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks in point 3, highlighted in the red rectangle.

A few metres apart, points 3, 4 and 5 show uniform erosion with a smooth or undulating appearance. For these points, I considered the average decrease in thickness, noting wear or erosion of the part of the pavement immediately outside the paving blocks, varying from approximately 15 mm to approximately 45 mm.

Calculation of construction period with point 3 Khufu consumption

Average erosion over 675 years B.P.: average 1 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 3 cm = 30 mm

Construction date: 675 x 30 / 1 = 20,250 years B.P.

Calculation of construction period with point 4 Khufu consumption

Average erosion over 675 years B.P.: average 1 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 1.5 cm = 15 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 15 / 1 = 10,125 years B.P.

Calculation of construction period with point 5 Khufu consumption

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: average 1 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 4.5 cm = 45 mm

Construction date: 675 x 45 / 1 = 30,375 years B.P.

The procedure described above, together with the corresponding calculations, was applied to each of the twelve analysed points on the Pyramid of Khufu, with each point yielding different yet mutually compatible results. The arithmetic mean of these twelve values represents the most probable estimate for the age of the Pyramid of Khufu.

Figure 15.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the paving blocks at point 6, highlighted in the red oval.

Figure 15.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the paving blocks at point 6, highlighted in the red oval.

Figure 16.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 6, highlighted in the red rectangle.

Figure 16.

Wear on the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 6, highlighted in the red rectangle.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 6 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 11 cm = 110 mm

Construction date: 675 x 110 / 2.5 = 29,700 years B.P.

Figure 17 and 18.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 7.

Figure 17 and 18.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 7.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 7 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 10 cm = 100 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 100 / 2.5 = 27,000 years B.P.

Figure 19.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 8.

Figure 19.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 8.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 8 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 17 cm = 170 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 170 / 2.5 = 45,900 years B.P.

Figure 20.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 9.

Figure 20.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 9.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 9 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 20 cm = 200 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 200 / 2.5 = 54,000 years B.P.

Figure 21.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 10.

Figure 21.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 10.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 10 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: average 1 mm

Average erosion from the beginning: 2 cm = 20 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 20 / 1 = 13,500 years B.P.

Figure 22.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 11.

Figure 22.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 11.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 11 Khufu

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1–5 mm, average 3 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 10 cm = 100 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 100 / 3 = 22,500 years B.P.

Figure 23.

The difference in erosion at point 12 between the right side (which has been exposed since the pyramid was built) and the left side.

Figure 23.

The difference in erosion at point 12 between the right side (which has been exposed since the pyramid was built) and the left side.

Figure 24.

Calculation of erosion (recess volume) at point 12.

Figure 24.

Calculation of erosion (recess volume) at point 12.

Calculation of construction period based on volume of eroded recesses at point 12 Khufu

Total volume of eroded recesses in exposed part: 13,072 mm3

Total volume of eroded recesses in exposed part 675 years B.P.: 396 mm3

Date of construction: 13,072 x 675 / 396 = 22,281 years B.P.

Arithmetic mean m of the 12 values calculated for the G1 pyramid of Akhet Khufu

m = (5,708 + 17,955 + 20,250 + 10,125 + 30,375 + 29,700 + 27,000 + 45,900 + 54,000 + 13,500 +

22,500 + 22,281) / 12 = 24,941 years B.P. = 22,941 B.C.

Standard deviation

σ = 13,962

Z score: (x - m) / σ

| -1,37 |

-0,50 |

-0,33 |

-1,06 |

0,38 |

0,34 |

0,14 |

1,50 |

2,08 |

-0,81 |

-0,17 |

-0,19 |

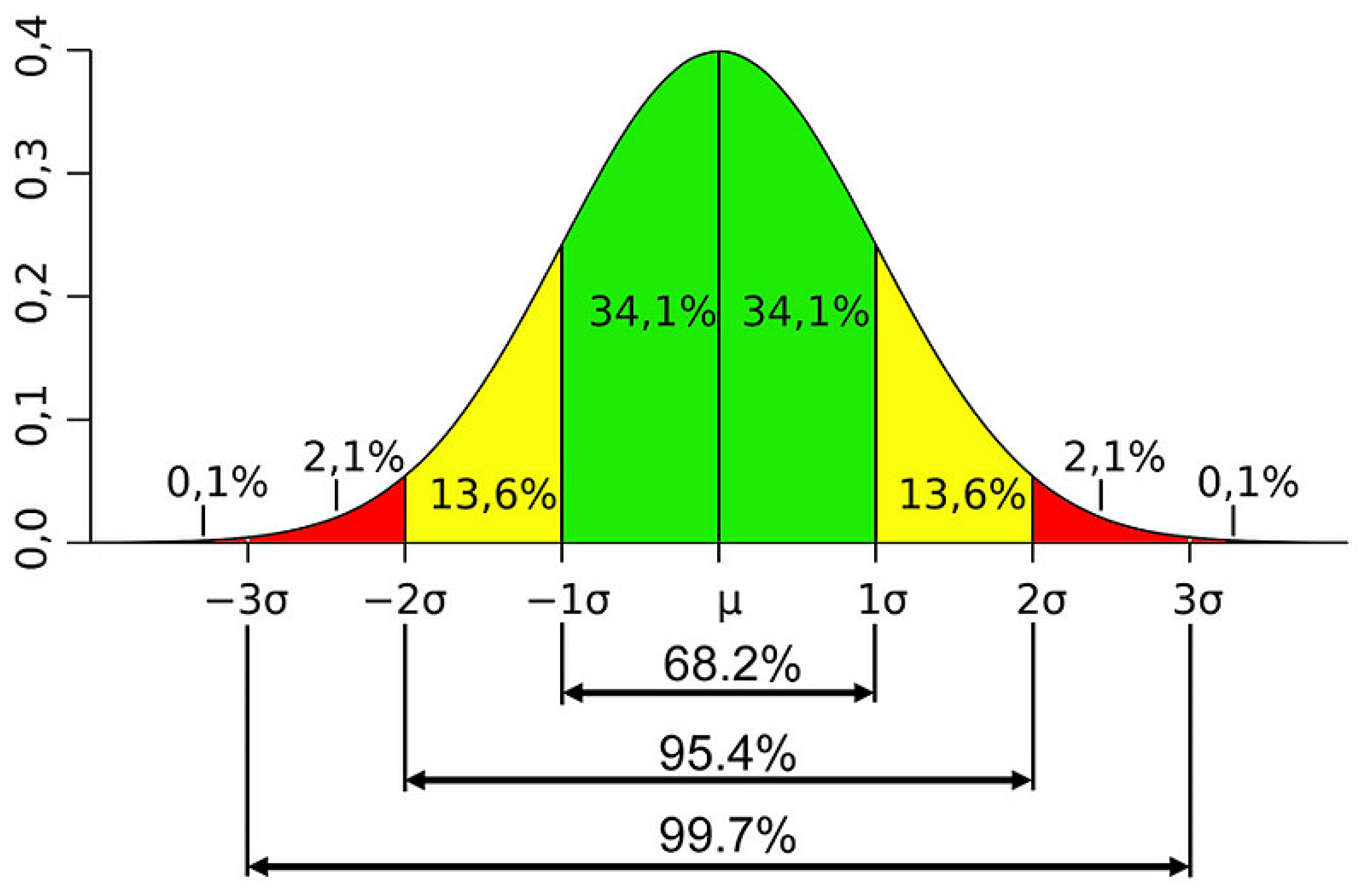

Figure 25.

Gaussian curve showing the 68.2% probability that the value will fall within plus or minus one standard deviation [

3].

Figure 25.

Gaussian curve showing the 68.2% probability that the value will fall within plus or minus one standard deviation [

3].

Therefore, regarding the dating of the G1 pyramid of Akhet Khufu calculated based on REM, I have a 68.2% probability that it is between (m - σ) and (m + σ), i.e. (24,941 - 13,962) and (24,941 + 13,962).

There is a 68.2% probability that the construction period of the G1 pyramid of Akhet Khufu is between 10,979 and 38,903 years B.P., with an average of 24,941 years B.P.

68.2% probability that the G1 pyramid of Akhet Khufu was built between 8,954 B.C. and 36,878 B.C., with an average of 22,916 B.C.

Points analysed in the G1b pyramid of Meritites I

Figure 26.

The pyramid G1b of Queen Meritites I, with the points where I measured the relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 26.

The pyramid G1b of Queen Meritites I, with the points where I measured the relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 27.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 13.

Figure 27.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 13.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 13 Meritites I

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 2.5 cm = 25 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 25 / 2.5 = 6,750 years B.P.

Figure 28.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 14.

Figure 28.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 14.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 14 Meritites I

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion from the beginning: 1.5 cm = 15 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 15 / 2.5 = 4,050 years B.P.

Arithmetic mean m of the 2 values calculated for the pyramid G1b of Meritites I

μ = (6,750 + 4,050) / 2 = 5,400 years B.P. = 3,375 B.C.

Points analysed in the G1c pyramid of Henutsen

Figure 29.

The G1c pyramid of Queen Henutsen, with the points where I measured relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 29.

The G1c pyramid of Queen Henutsen, with the points where I measured relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 30.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 15.

Figure 30.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 15.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 15 Henutsen

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 2–4 mm, average 3.0 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 2.5 cm = 25 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 25 / 3.0 = 5,625 years B.P.

Figure 31.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 16.

Figure 31.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 16.

Calculation of construction period using point 16 Henutsen consumption

Average erosion over 675 years B.P.: 1–3 mm, average 2 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 2 cm = 20 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 20 / 2 = 6,750 years B.P.

Arithmetic mean m of the two values calculated for Henutsen’s pyramid G1c

μ = (5.625 + 6.750) / 2 = 6,187 years B.P. = 4,162 B.C.

Points analysed in the in the G2 pyramid of Khafra

Figure 32.

The G2 pyramid of Khafra, with the points where I measured relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 32.

The G2 pyramid of Khafra, with the points where I measured relative erosion marked in red. (picture from Googleearth).

Figure 33.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 17.

Figure 33.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 17.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 17 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 3 mm, average 2 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 3.5 cm = 35 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 35 / 2 = 11,812 years B.P.

Figure 34.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 18.

Figure 34.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 18.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 18 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 3 mm, average 2 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 10 cm = 100 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 100 / 2 = 33,750 years B.P.

Figure 35.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 19.

Figure 35.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 19.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 19 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1–2 mm, average 1.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 2 cm = 20 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 20 / 1.5 = 9,000 years B.P.

Figure 36.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the paving blocks at point 20.

Figure 36.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the paving blocks at point 20.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 20 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 4 mm, average 2.5 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 12 cm = 120 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 120 / 2.5 = 32,400 years B.P.

Figure 37.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 21.

Figure 37.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 21.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 21 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 2–4 mm, average 3 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 18 cm = 180 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 180 / 3 = 40,500 years B.P.

Figure 38.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 22.

Figure 38.

Wear or erosion of the paving immediately outside the cladding blocks at point 22.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 22 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1–3 mm, average 2 mm

Average erosion since the beginning: 3 cm = 30 mm

Construction date: 675 x 30 / 2 = 10,125 years B.P.

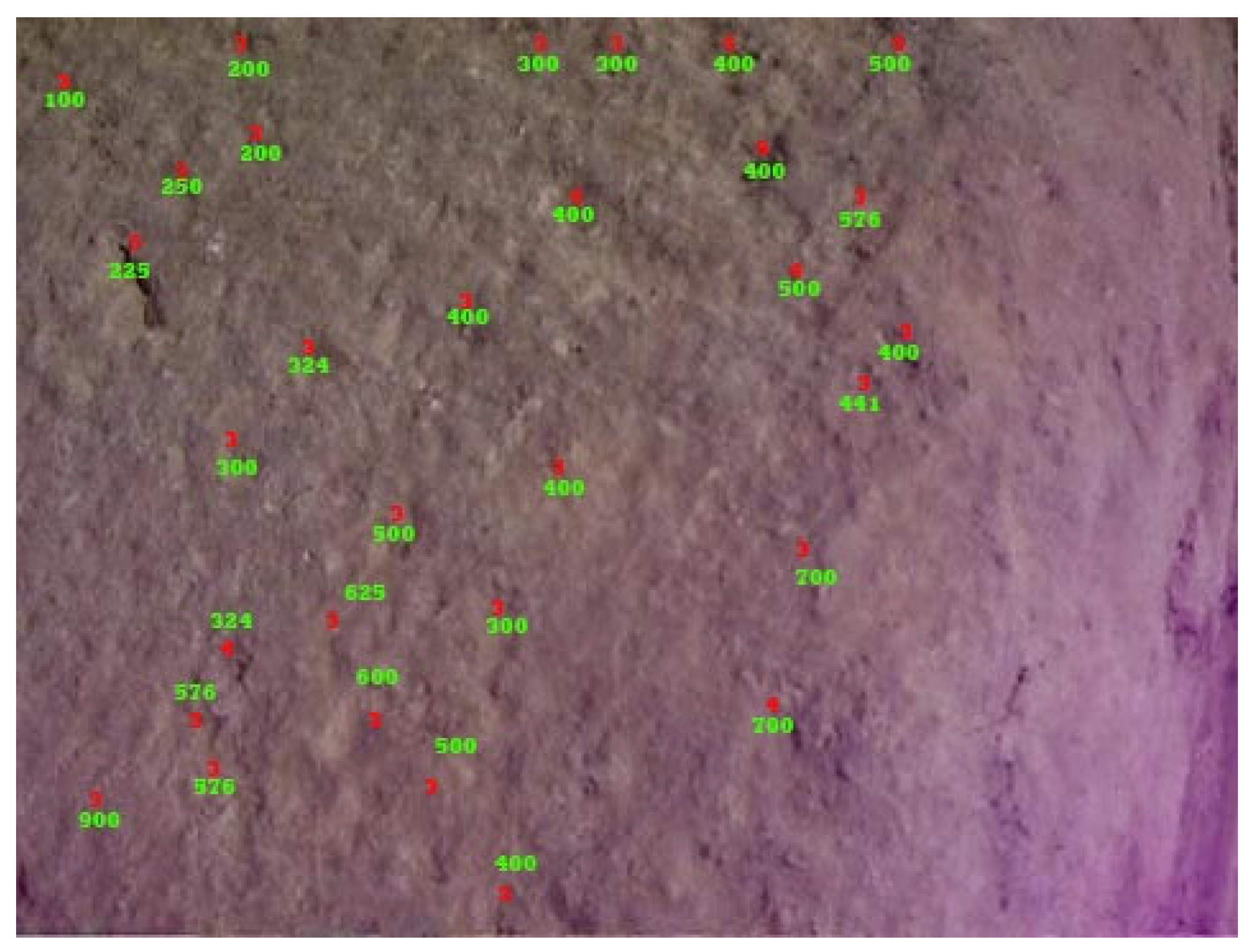

Figure 39.

Erosion of the pavement of the Khafra quarry, at point 23. The area of the eroded cavities is shown in green and their average depth in red, in order to calculate their volume.

Figure 39.

Erosion of the pavement of the Khafra quarry, at point 23. The area of the eroded cavities is shown in green and their average depth in red, in order to calculate their volume.

Figure 40.

Erosion of the base of the pyramid of Khafra carved into the rock, which was once covered by facing blocks, at point 23. The area of the eroded cavities is shown in green and their average depth in red, in order to calculate their volume.

Figure 40.

Erosion of the base of the pyramid of Khafra carved into the rock, which was once covered by facing blocks, at point 23. The area of the eroded cavities is shown in green and their average depth in red, in order to calculate their volume.

Calculation of construction period based on the volume of eroded cavities at point 23 Khafra

Total volume of eroded cavities in the exposed part: 1,584,850 mm³

Total volume of eroded recesses in the uncovered part 675 years B.P.: 43,701 mm3

Date of construction: 1,584,850 x 675 / 43,701 = 24,479 years B.P.

Figure 41.

Erosion of the pavement at the Khafra quarry, at point 24.

Figure 41.

Erosion of the pavement at the Khafra quarry, at point 24.

Figure 42.

Erosion of the base of the pyramid of Khafra carved into the rock, which was once covered by cladding blocks, at point 24.

Figure 42.

Erosion of the base of the pyramid of Khafra carved into the rock, which was once covered by cladding blocks, at point 24.

Calculation of construction period based on volume of eroded recesses at point 24 Khafra

Total volume of eroded recesses in exposed section: 1,273,320 mm³

Total volume of eroded recesses in the uncovered part 675 years B.P.: 39,430 mm3

Date of construction: 1,273,320 x 675 / 39,430 = 21,797 years B.P.

Figure 43.

Wear or erosion of the pavement immediately outside the paving blocks at point 25.

Figure 43.

Wear or erosion of the pavement immediately outside the paving blocks at point 25.

Calculation of construction period with consumption point 25 Khafra

Average erosion from 675 years B.P.: 1 – 3 mm, average 2 mm

Average erosion from the beginning: 4 cm = 40 mm

Date of construction: 675 x 40 / 2 = 13,500 years B.P.

Arithmetic mean μ of the 9 values calculated for the G2 pyramid of Khafra

μ = (11.812 + 33.750 + 9.000 + 32.400 + 40.500 + 10.125 + 24.479 + 21.797 + 13.500) / 9 = 21.929

years B.P. = 19.904 B.C.

Standard deviation

σ = 11.623

Z score: (x - μ) / σ

-0,87 1,01 -1,11 0,90 1,59 -1,01 0,21 -0,011 -0,72

Figure 44.

Gaussian curve showing the 68.2% probability that the value will fall within plus or minus one standard deviation [

3].

Figure 44.

Gaussian curve showing the 68.2% probability that the value will fall within plus or minus one standard deviation [

3].

Therefore, regarding the dating of Khafra’s pyramid G2 calculated on the basis of REM, I have a 68.2% probability that it lies between (μ - σ) and (μ + σ), i.e. (21,929 - 11,623) and (21,929 + 11,623).

68.2% probability that the pyramid G2 of Khafra was built between 10,306 and 33,552 years B.P., with an average of 21,929 years B.P.

68.2% probability that the G2 pyramid of Khafra was built between 8,281 B.C. and 31,527 B.C., with an average of 19,904 B.C.