1. Introduction

Developing renewable energies has become a common strategy and effort across worldwide countries since it became fundamental to reverse the global change [1]. Wind of the oldest and most developed sources of renewable energy, [2,3] with an increase in production exceeding 20% annually over the last decade [4]. Fitting with the current environmental issue, wind facilities generate a low environmental impact by reducing environmental pollution and water consumption [5]. Despite environmental benefits, no energy source is fully ‘biodiversity-neutral’ and wind farms are no an exception.

Three major impacts arise with the development of this kind of facilities: noise pollution [6], visual impact on the landscape, and effects on wildlife. Bats and birds are the most impacted taxa because, as flying animals, they are more prone to collide with the turbine rotor [7,8,9,10,11]. The bird population has undergone a substantial decline in the last century, mainly due to anthropogenic activities like illegal shooting [12] or accidents with man-made structures such as power lines [13,14,15], buildings [16] or road networks [17]. This is the reason of the increasing concern about wind farms impact on birds [18,19,20] and bats [21,22,23,24], particularly on bird of prey populations [7,25]. Studies have identified a complex interaction between site-species-season factors emphasizing the raptor susceptibility to collide with wind turbines [7,8,26,27]. And as long-lived species with low reproduction rates and delayed maturation, raptors are sensitive to any individual removal likely to affect the population viability [28].

In addition to the threat of collision with rotor blades, wind farms can trigger a displacement effect on birds (functional habitat loss) leading to a low density of birds in the vicinity of wind energy facilities. Avoidance potentially decreases collision risk but, at the same time, would reduce substantially habitat availability for the specie. A lower breeding success in a White-tailed Sea eagle population was found [29] in those pairs breeding near the turbines resulting in a decrease of the population growth. The displacement phenomenon happens at two scales, distinguished in macro- and meso-displacement. Macro-displacement is characterised by the avoidance of the entire wind farm and may result in a loss of suitable habitat or change in migratory paths leading to a decrease of energy stock and fitness [30,31]. Meso-displacements, described as the avoidance of individual turbines, may trigger changes in flight behaviour and loss of local resources [30]. The avoidance through wariness of turbines has been detected in several raptors’ species [25,32,33]. Alike collision, displacement patterns could be driven by the interaction of site-species-season factors [25,32,34]. However, inconsistent instances of avoidance phenomenon have been shown questioning the real functional loss of habitat [35,36].

Being the fifth country in wind energy production, Spain has a high density of wind farms [4]. At the same time, Spain is also known for its rich bird of prey populations, hosting the largest population of the Spanish imperial eagle Aquila adalberti, among others. Extremely threatened in the 90’s and considered as one of the rarest bird of prey in the world, only 150 pairs were remaining when a recovery program starts including a massive retrofit of dangerous power poles and reintroduction projects [35,36].

Thanks to this and additional actions, the population is currently growing in the Iberian Peninsula with around 1,000 pairs in 2023 (Spanish Imperial Eagle Working Group, unpublished data). Nevertheless, this large raptor is still considered the most threatened in Europe [37]. As the population expands, there are strong concerns about the negative effects of wind farms on the recovery of the species. One of the most used dispersal areas of juvenile Spanish imperial eagles, the Cadiz province in southern Spain, is at the same time one of the areas with higher density of wind farms in the Iberian Peninsula.

Autonomous governments are responsible of environmental impact assessment evaluation. On the mandatory environmental impact assessment, in Spain, the existence or not of previous locations of radio tagged eagles over the area is currently used as critical criterion to adopt a decision on viability of new installations, been negative in case any single location is over the proposed area, because the environmental administration considers that, due to avoidance behaviour, the eagles are going to abandoned the area if a wind farm is build there. These previous studies did not evaluate 3-dimensional use of space around wind turbines (e.g., by including elevation/altitude of GPS relocations), but rather the 2-dimensional landscape surface around turbines (regardless of vertical space). For these reasons, we decide to analyze if we can demonstrate avoidance behavior in young eagles using the 2-D information.

Furthermore, an attempt to identify the key conservation areas for the Spanish imperial eagle across the Iberian Peninsula has been recently conducted, evaluating the potential impact of renewable energy facilities on the species and the infrastructure exclusion and development areas established under Directive (EU) 2023/2413 on the promotion of renewable energy. Again, the 2-D information was used for this purpose [38].

In this study, we investigated the response of dispersing juvenile of the Spanish imperial eagle to wind power facilities at both wind farm and turbine level. The analyses only involve data starting from the first of October of each juvenile, as we were only interested in the independent dispersal period of the juveniles, which starts around the age of 5 months [39]. Using high resolution GPS-tracking data, we applied two different approaches to determine any avoidance behaviour of juvenile eagles during their dispersal period. First, we looked for a broader potential avoidance at the wind farm scale (macro-displacement), using an experimental design based on density comparison between wind farms and control areas. We conducted a habitat selection analysis trying to find any influence of wind farms among the explanatory variables. Second, to get a finer insight of the phenomenon around turbines (meso-displacement), we compared density of GPS-tracking locations and random locations at five different intervals of 200 m around turbines, totalling 1 Km. We hypothesize a lower density of eagles at wind farms areas over control areas under a phenomenon of wind farm avoidance from juvenile eagles. Similarly, we expect lower density in the vicinity of the turbines, confirming the avoidance behaviour and a possible threshold effect [40].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Species

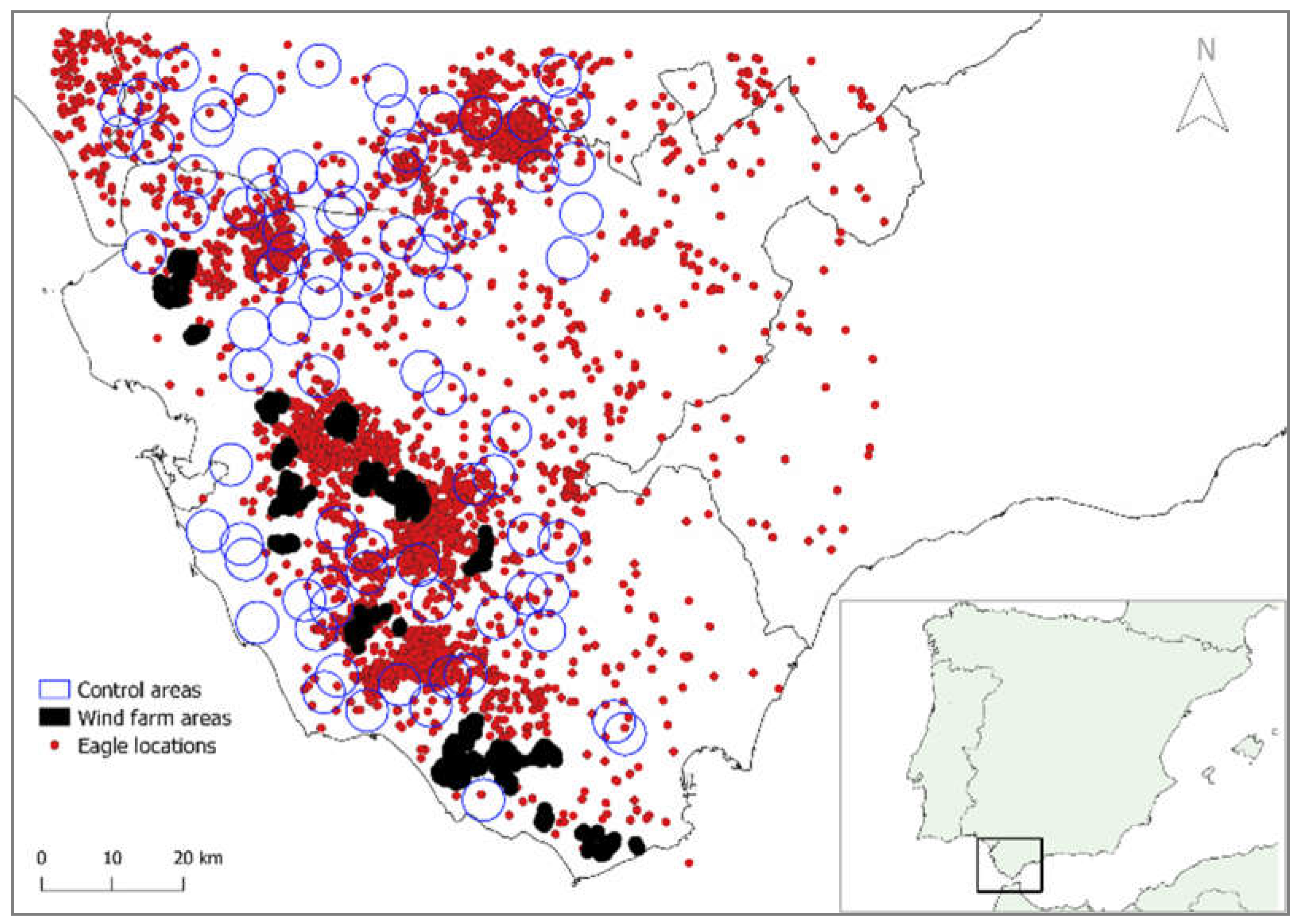

The study took place in the province of Cadiz in the southwest Spain (36°21'34"N, 5°52'45"W) with 59 wind farms conforming 13 aggregations (

Figure 1). The area is characterized by a mosaic of habitat types like scrublands, grasslands, and irrigated and non- irrigated fields [41], in a low mountain range (300 m approx.) with a dry-humid Mediterranean climate. It is also close to the Strait of Gibraltar, a very important pass where many bird species concentrate during their migration between Europe and Africa.

The Spanish imperial eagle is a large, territorial and tree-nesting raptor of the Iberian Peninsula. While having a life span of 22 years approximately, its maturity is reach at 4-5 years and in optimal and stable condition, this species has an annual productivity of 0.75 chicks per pair [39]. The reproduction lasts from February to October with a hatching period in April-May. Nestlings start to fly at 60–85 days old but they disperse only between 125-160 days old, at the beginning of October. During this interval, the juveniles are not yet independent; they gradually explore areas and their flying skills while being fed by the adults [38]. The dispersal period is characterised by long-range exploratory movements and the rotatory use of temporary settlement areas with frequent returns to the natal area [38]. Juvenile eagles select preferably open-habitats with dispersed Quercus spp, low level of human disturbance and high prey density (e.g. European rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus) as dispersal areas [39].

2.2. Data Collection

From 2015 to 2019, a total of 48 nestling imperial Spanish eagles (24 males, 24 females) were equipped with GPS-GSM transmitters at 40 to 70 days old. Solar-powered transmitters from Microwave, Ecotone and E-obs companies were used and attached to birds with a Teflon harness with a breast-rupture point. The total weight of tag plus harness did not exceed a maximum of 3% of young total body mass at fledging [41]. Sex and age were determined by means of morphometric measurements and confirmed by molecular analysis using blood samples [38]). Transmitters were programmed to record GPS coordinates every 30- or 60-minutes during day time. The monitoring period ended up with a database of 83,358 spatial points at 25th of May 2020, date of the last record. The analyses only involve data starting from the first of October of each juvenile, as we were only interested in the independent dispersal period of the juveniles, which starts around the age of 5 months. In addition, only one record per day and individual (at 12 am) was kept to avoid spatial autocorrelation between locations. At noon, we expect that eagles are not resting and express diurnal activities related to dispersal behaviour, being a time where the soaring flight are common. The final analysis comprised 4, 894 spatial data from 37 individuals after filtering out all non-flight sections.

2.3. Macro-Displacement

We identified and georeferenced 831 turbines locations in the Cadiz province, belonging to 59 wind farms, using public datasets provided by Red Eléctrica de España [43]. At the broad wind farm level, facilities areas were delimited by adding a 1 km–buffer zone around turbines to account for any influence of turbine occurrence on the immediate surrounding. We set a 1 km buffer based on previous studies on the distance at which the influence of wind facilities continues to cause disturbance and displacement to raptors [29]. It resulted in 13 distinct wind turbines aggregation areas, with a mean surface of 28 km2 (± 6.38). For comparison purposes we used 82 control areas with the same mean surface of the actual wind farm areas, and randomly located within the known dispersal area of the species in the Cadiz province. In each area, the relative density of locations was assessed and categorized as wind farm (WF) or control (C) levels of treatment.

2.4. Meso-Displacement

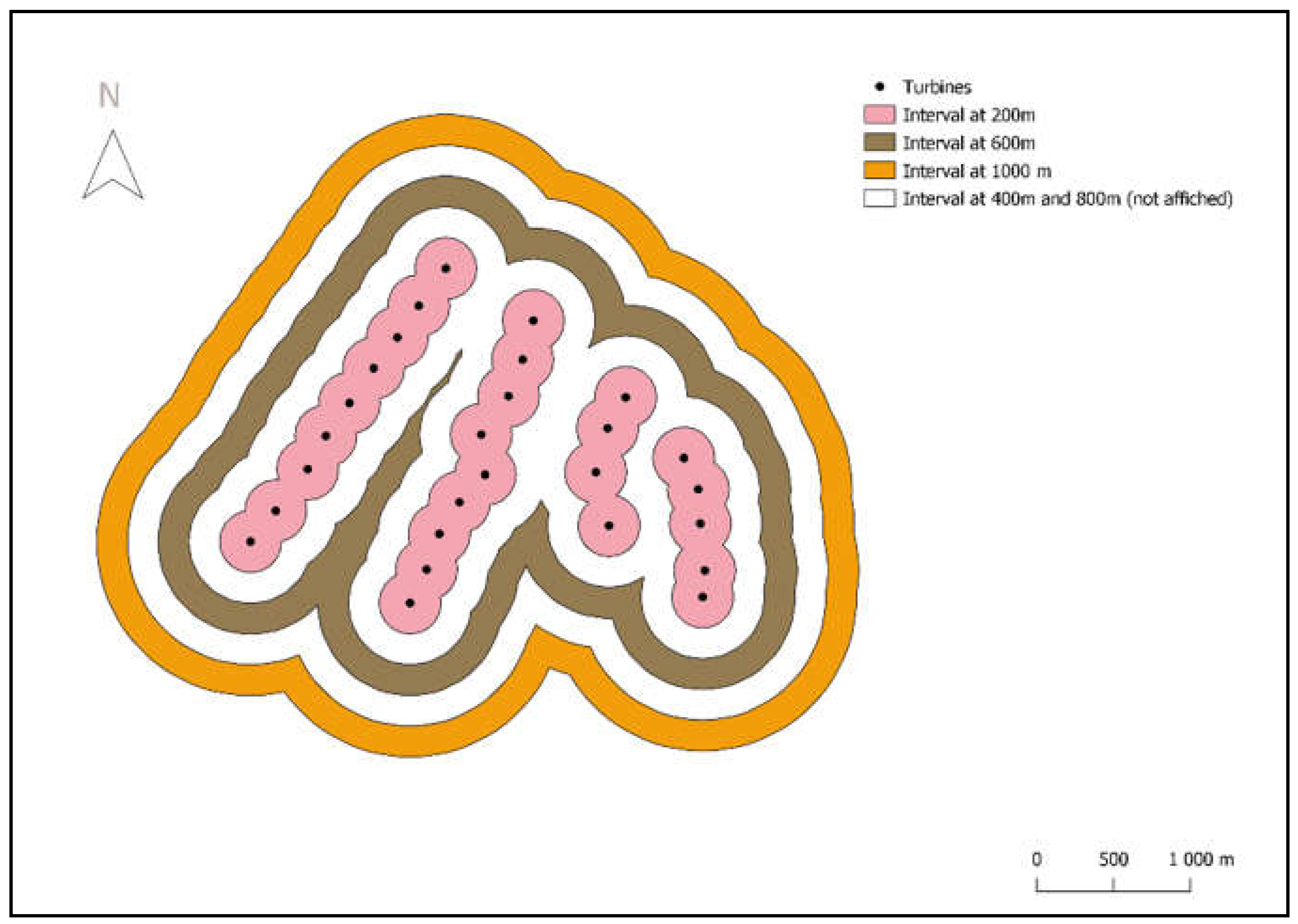

The analysis at turbine scale was based on the comparison between the densities of eagle locations assessed at five different concentric intervals of 200 m wide around each individual turbine up to a distance of 1 km. Under a non-avoidance scenario, we expect a constant density value and hence no differences of density across distance intervals.

As the occurrence of young dispersers could be related to habitat type, human activity and topography [44], we controlled for these factors in both macro and meso analysis. Using the Corine Land Cover 2018 vectorial dataset [46], we grouped landscape categories into nine habitat types, though only five of them were used according to their biological relevance: forest, non-irrigated field, grassland, shrubland, and irrigated field. The percentage of these five habitat types was determined for each WF and C zone. At turbine level, this percentage was calculated for each 200-m wide buffer interval in the 13 wind farms. In both models, the human activity was derived from the night light intensity recorded by the Earth Observation Group, since it is considered as a strong proxy for human activity and potential disturbances [47]. We used the average night light recorded from 2015 to 2020 from the Global Nighttime Light Map “VIIRS Nighttime Light (VNL) V2” [46]. Concerning the topography, we used a raster map of slopes (5x5 km) provided by the CMAyOT to calculate the mean slope per areas and intervals [37]. The software QGIS (v 3.16.7) was used to elaborate spatial data sets of locations and predictors.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We applied Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) to check for macro-displacement at wind farm scale. We used density of locations within the 1 km-buffer areas as the response variable after log-transformation due to the right-skewed data distribution in order to apply a normal distribution. The factor treatment comparing actual wind farms (WF) versus control random areas (C) was included as the predictor of interest in the models together with the percentage of each five main habitat categories, mean slope, and night-light intensity as a proxy of human activity.

For meso-displacement we applied Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to look for avoidance behaviour at turbine level. Density of locations within each concentric 200-m distance interval from turbines (up to 1 km) in wind farm areas was the response variable, whereas the radial interval (i.e. from 0-200 m to 800-1000 m) was the main fixed predictor of interest together with the five habitat types, mean slope and night-light intensity, as in the previous GLMs for macro-displacement. GLMMs included wind farm identity, turbine identity and bird identity as random effects.

Predictor variables were previously standardized in order to allow for direct variable comparison, and assumptions of heteroscedasticity, variable independence and collinearity were also tested in all cases using R (v. 4.1.1.; R Core Team). For all analyses, we built an initial set of models with all the possible combinations of predictors and performed a subsequent model selection by using the Akaike Information Criterion adjusted for small sample size (AICc). We selected models with a difference of AICc (∆AICc) lower than two in relation to the most plausible model with the lowest AIC. Then, we performed model-averaging on the subset of selected models to obtain averaged coefficients, standard errors (SE) and confidence intervals (CI), accounting for model uncertainty. Analyses were performed using the packages lme4 and MuMin in R (v. 4.1.1.). Significance level was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Macro-Displacement

At the wind farm scale, the average density of locations of juvenile Spanish imperial eagles during their dispersal period in the province of Cadiz was 5.17 ± 1.74 loc/km2 in wind farm areas versus 4.6 ± 0.75 loc/km

2 in random control areas. Contrary to expectations, density is higher in wind farm area but these slight differences were not supported by the analysis, so the relative use of areas close to wind farms (i.e. 1 km radius buffer) was comparable to the expected use under a random distribution of areas (

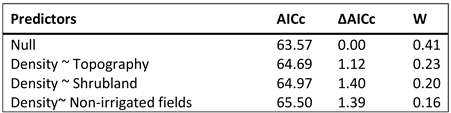

Table 1;

Figure 1). This result points to a non-avoidance behaviour of young eagles at least at the macro-scale of wind farms. In relation to environmental covariates, only night-light intensity and non-irrigated fields were supported in the model selection (

Table 2). Juvenile eagles tended to avoid areas highly illuminated at night and thus with higher human activity, whereas they preferred non-irrigated traditional crops (e.g. cereal crops) probably with higher prey density.

3.2. Meso-Displacement

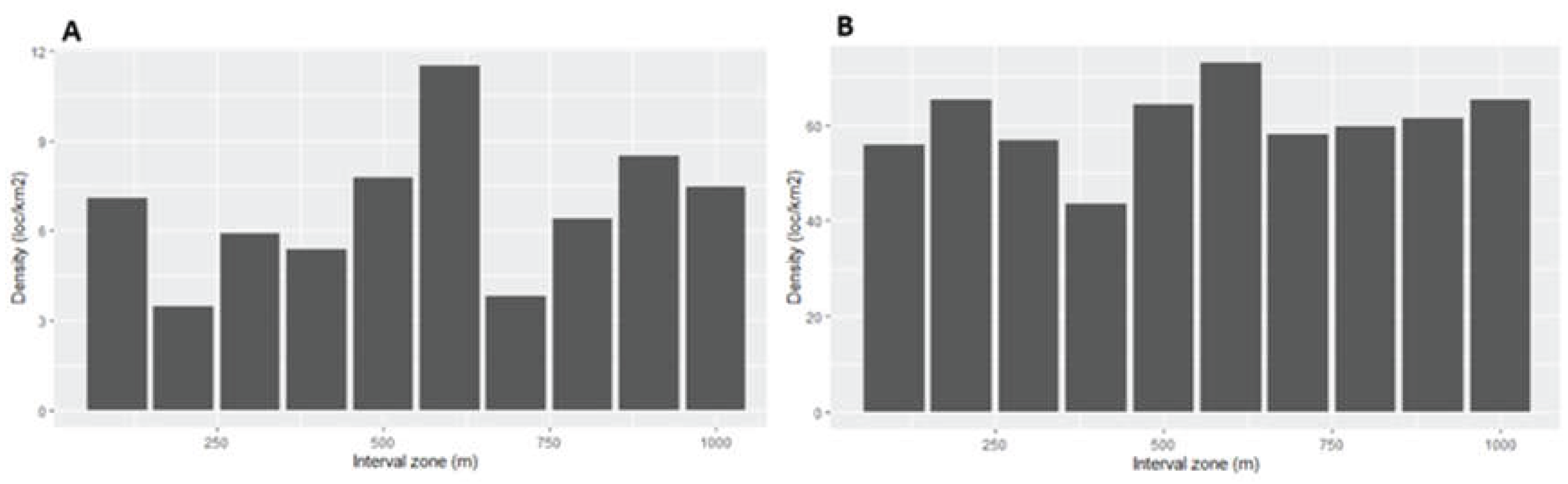

Due to the configuration of wind farms with multiple nearby turbines, the areas around individual turbines tend to overlap with distance and the increasing surface levels off at a certain distance threshold (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Differences in density of eagle locations within the five 200-m wide intervals (i.e. from the turbine up to 1 km) were not supported by the model selection (

Table 3; Figure 4). Therefore, young eagles did not show avoidance behaviour at meso-scale and displayed an occupation pattern similar across intervals of distance from turbines in the study area, even after accounting for environmental predictors of habitat occupation. Likewise, none of the predictors of habitat, human activity or topography was either supported (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis at the macro-scale, we found that juvenile Spanish Imperial Eagles do not avoid wind farm areas. Preference or lack of attraction to specific habitats is more likely to explain the dispersal pattern of juveniles at this level. At meso-scale, we found no support to an avoidance behaviour. Traditional avoidance studies used distance, namely the distance from eagle’s locations to the closest wind turbine, typically inside a 1 km radius [25,32,40]. When some avoidance behaviour occurs, then a decrease in frequency of locations close to the turbine is expected, otherwise a homogeneous distribution of distances to turbines is typically assumed [33]. However, the number of locations of tagged eagles is a function of the surface considered and not of the distance. The shape of the expected frequency of locations with distance will follow a strong initial increase followed by a plateau, mimicking a spurious avoidance effect

In order to avoid this artefact and to account for the increasing surface with distance, we used density of locations per area (i.e. total 1 km buffer or 200-m wide intervals) instead of distance. Under no avoidance behaviour, the expected random distribution of densities would fit a constant value, whereas with an avoidance phenomenon a true decreasing density in nearby distance intervals would be expected.

Following results, young Spanish imperial eagles give no sign of avoidance neither at wind farm scale nor at turbine scale. From a conservational point of view, this a positive outcome for this threatened species. Indeed, this means that wind farms in Cadiz region do not represent a hindrance to the recovery and expansion of this species population, which is already well underway [37]. The cohabitation between the Spanish eagle species and wind infrastructures seems possible, provided that regulations for the construction and operation of wind farms are properly enforced [7,8,11] and that conservation efforts devote to eagles continue. Indeed, wind farm development policies combined with recommended and implemented mitigation measures, seems to be effective in the conservation of this and other species [11]. Other human-induced threaten factors are much more relevant for non-settled juvenile dispersers, especially electrocution on pylons of distribution power lines [15]. Although the extensive correction of dangerous pylons in the last decades has notably reduced the associated mortality risk [36], making it a good example of effort and way forward to follow. Hence, the importance of these regulations and actions in the current population increase should not be overlooked or neglected under the pretext of a successful recovery, especially because only one mortality event due to collision against wind turbine have been recorded. While few, this event should not be minimised, especially on a sensitive population and species like the Spanish imperial eagle.

5. Conclusion

When some avoidance behaviour occurs, then a decrease in frequency of locations close to the turbine is expected, otherwise a homogeneous distribution of distances to turbines is typically assumed [25,32,33,40]. Traditional avoidance studies used distance, namely the distance from eagle’s locations to the closest wind turbine, typically inside a 1 km radius [25,32,40]. When some avoidance behaviour occurs, then a decrease in frequency of locations close to the turbine is expected, otherwise a homogeneous distribution of distances to turbines is typically assumed [33]. However, the number of locations of tagged eagles is a function of the surface considered, and not of the distance. If we use distances to the turbines, a spurious increase is expected, causes surface is increasing according, including more and more locations and showing a decrease of locations when closing to the turbine. The shape of the expected frequency of locations with distance will follow a strong initial increase followed by a plateau, mimicking a spurious avoidance effect. A substantial proportion of the literature shown this weakness [29,32,33,50].

The reason why some birds avoid wind turbines is still unclear. The fact that birds are displaced far beyond the areas occupied by the physical infrastructure of wind-power plants could be a consequence of neophobia, as turbines do not belong to their natural environment, but it could also be a consequence of earlier negative experiences, such as birds being caught in the airflow around turbines, or even witnessing fatalities of conspecifics [33,50]. The avoidance of turbines varies considerably among soaring species, their life stage and their annual cycle; thus, the range of influence of wind turbines found in some studies is not necessary replicable in other contexts.

One interesting conclusion is that, on the mandatory environmental impact assessment, the existence or not of previous locations of radio tagged eagles over the area is currently used as critical criterion to adopt a decision on viability of new installations, been negative in case any single location is over the proposed area, because the environmental administration considers that the eagles are going to abandoned the area if a wind farm is build there. Nevertheless, as we have demonstrated, there is no scientific evidence for this criterion but the opposite. We believe these findings are relevant to future research on displacement effects of human infrastructures but also for the correct interpretation of past research, based on unadjusted distances from turbines, instead of density of locations. The study of avoidance behaviours is an ongoing topic and therefore these methodological details can help to better understand this phenomenon and to improve conservation and management decisions, especially for species sensitive to the presence of wind farms and other threatening infrastructures in their habitats.

Author Contributions

M.F., and V.M. conceived the ideas and designed methodology; A.A., R.M. and R.B. collected and analysed the data; A.A. and M.F. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our research has been evaluated and ap-proved by The Ethical Committee of the Spanish Council for Scientific Research, which is the oversight authority for such matters in Spain (registration number 20/12/2017/173). The project also was authorized by the Andalusia environmental administration (i.e., Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Junta de Andalucía), which has granted the appropriate licenses for handling and tagging the nestlings. Procedures used in this study comply with the current laws, guidelines and regulations for working on the Doñana National Park. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Data Availability Statement

Databases will be available in Digital CSIC repository

https://doi.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, X.; Wei, Z.; Ji, Q.; Wang, C.; Gao, G. Global renewable energy development: Influencing factors, trend predictions and countermeasures. Resour. Policy 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.L.; Kaushik, S.C.; Kothari, S. Role of renewable energy sources in environmental protection: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.S.; Bilal, M.; Sohail, H.M.; Liu, B.; Chen, W.; Iqbal, H.M. Impacts of renewable energy atlas: Reaping the benefits of renewables and biodiversity threats. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 22113–22124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.R.; Rezk, H.; Mustafa, R.J.; Al-Dhaifallah, M. Evaluating the Environmental Impacts and Energy Performance of a Wind Farm System Utilizing the Life-Cycle Assessment Method: A Practical Case Study. Energies 2019, 12, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Abdelaziz, E.; Demirbas, A.; Hossain, M.; Mekhilef, S. A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2262–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neal, R.D.; Hellweg, R.D.; Lampeter, R.M. Low frequency noise and infrasound from wind turbines. Noise Control. Eng. J. 2011, 59, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, M.; Janss, G.F.E.; Whitfield, D.P.; Ferrer, M. Collision fatality of raptors in wind farms does not depend on raptor abundance. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 45, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; de Lucas, M.; Janss, G.F.E.; Casado, E.; Muñoz, A.R.; Bechard, M.J.; Calabuig, C.P. Weak relationship between risk assessment studies and recorded mortality in wind farms. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 49, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxter, C.B.; Buchanan, G.M.; Carr, J.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Newbold, T.; Green, R.E.; Tobias, J.A.; Foden, W.B.; O'Brien, S.; Pearce-Higgins, J.W. Bird and bat species' global vulnerability to collision mortality at wind farms revealed through a trait-based assessment. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20170829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.S.; Mahdi, A.J.; Bilal, M.; Sohail, H.M.; Ali, N.; Iqbal, H.M. Environmental impact and pollution-related challenges of renewable wind energy paradigm – A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 683, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Alloing, A.; Baumbush, R.; Morandini, V. Significant decline of Griffon Vulture collision mortality in wind farms during 13-year of a selective turbine stopping protocol. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmori, A. Endangered bird mortality by gunshots: still a current problem. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, J.; Bevanger, K.; Barrientos, R.; Dwyer, J.; Marques, A.; Martins, R.; Shaw, J.; Silva, J.; Moreira, F. Bird collisions with power lines: State of the art and priority areas for research. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 222, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; De La Riva, M.; Castroviejo, J. Electrocution of raptors on power lines in south western Spain. J. Field Ornithol. 1991, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, M. Birds and Power Lines: From Conflict to the Solution; Migres Foundation: Seville, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, S. R.; Will, T.; Loss, S. S.; Marra, P. P. Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. Condor 2014, 116, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociolek, A.V.; Clevenger, A.P.; Clair, C.C.S.; Proppe, D.S. Effects of Road Networks on Bird Populations. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orloff, S.; Flannery, A. Wind Turbine Effects on Avian Activity, Habitat Use, and Mortality in Altamont Pass and Solano Country Wind Resource Areas: 1989-1991; Final Report. In Biosystems Analysis; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, R.G.; Dieter, C.D.; Higgins, K.F.; Usgaard, R.E. Bird Flight Characteristics Near Wind Turbines in Minnesota. Am. Midl. Nat. 1998, 139, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, W.P.; Johnson, G.D.; Strickland, M.D.; Young, D.P.; Jr Sernja, K.J.; Good, R.E. Avian collisions with wind turbines: a summary of existing studies and comparisons to other sources of avian collision mortality in the United States; Western EcoSystems Technology Inc. National Wind Coordinating Committee Resource Document, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cyan, P.M. Wind turbines as landscape impediments to the migratory connectivity of bats. EnvLaw 2011, 41, 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Camina, Á. Bat Fatalities at Wind Farms in Northern Spain — Lessons to be Learned. Acta Chiropterologica 2012, 14, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Hayes, M. Bats Killed in Large Numbers at United States Wind Energy Facilities. BioScience 2013, 63, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.S. Comparing bird and bat fatality-rate estimates among North American wind-energy projects. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2013, 37, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, A.H.; Anderson, D.; Benn, S.; Taylor, J.; Tingay, R.; Weston, E.D.; Whitfield, D.P. Responses of GPS-Tagged Territorial Golden Eagles Aquila chrysaetos to Wind Turbines in Scotland. Diversity 2023, 15, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzner, T.; Brandes, D.; A Miller, T.; Lanzone, M.; Maisonneuve, C.; A Tremblay, J.; Mulvihill, R.S.; Merovich, G.T. Topography drives migratory flight altitude of golden eagles: implications for on-shore wind energy development. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, E.; Bulling, L.; Köppel, J. Consolidating the State of Knowledge: A Synoptical Review of Wind Energy’s Wildlife Effects. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 300–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, W.G.; Wiens, J.D.; Law, P.R.; Fuller, M.R.; Hunt, T.L.; E Driscoll, D.; E Jackman, R. Quantifying the demographic cost of human-related mortality to a raptor population. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0172232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, E.L.; Bevanger, K.; Nygård, T.; Røskaft, E.; Stokke, B.G. Reduced breeding success in white-tailed eagles at Smøla windfarm, western Norway, is caused by mortality and displacement. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 145, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.F. A unifying framework for the underlying mechanisms of avian avoidance of wind turbines. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 190, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodale, M.W.; Milman, A.; Griffin, C.R. Assessing the cumulative adverse effects of offshore wind energy development on seabird foraging guilds along the East Coast of the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 074018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, A.H.; Anderson, D.; Benn, S.; Dennis, R.; Geary, M.; Weston, E.; Whitfield, D.P. Non-territorial GPS-tagged golden eagles Aquila chrysaetos at two Scottish wind farms: Avoidance influenced by preferred habitat distribution, wind speed and blade motion status. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0254159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.D.; Ferraz, R.; Muñoz, A.-R.; Onrubia, A.; Wikelski, M. Black kites of different age and sex show similar avoidance responses to wind turbines during migration. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.L.; Muir, S.C. Behavior and turbine avoidance rates of eagles at two wind farms in Tasmania, Australia. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2013, 37, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pliego, J.; de Lucas, M.; Muñoz, A.-R.; Ferrer, M. Effects of wind farms on Montagu's harrier ( Circus pygargus ) in southern Spain. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therkildsen, O.R.; Balsby, T.J.; Kjeldsen, J.P.; Nielsen, R.D.; Bladt, J.; Fox, A.D. Changes in flight paths of large-bodied birds after construction of large terrestrial wind turbines. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, P.; Ferrer, M.; Madero, A.; Casado, E.; McGrady, M. Solving Man-Induced Large-Scale Conservation Problems: The Spanish Imperial Eagle and Power Lines. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e17196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Mateos, R.; Tobajas, J.; Oria, J.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Margalida, A. Integrating conservation priorities into spatial planning for renewable energy development: The case of the Spanish imperial eagle. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel, R.; Ferrer, M.; Casado, E.; Madero, A.; Calabuig, C.P. Settlement and Successful Breeding of Reintroduced Spanish Imperial EaglesAquila adalbertiin the Province of Cadiz (Spain). Ardeola 2011, 58, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMAyOT. Mapa de Pendientes de Andalucía, 2013 (5x5m). Available online: https://descargasrediam.cica.es/repo/s/RUR?path=%2F01_CARACTERIZACION_TERRITORIO%2F07_BASES_REF_ELEV (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Ferrer, M. The Spanish Imperial Eagle; Editorial Lynx: Barcelona, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, A.T.; Santos, C.D.; Hanssen, F.; Muñoz, A.R.; Onrubia, A.; Wikelski, M.; Moreira, F.; Palmeirim, J.M.; Silva, J.P. Wind turbines cause functional habitat loss for migratory soaring birds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2020, 89, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel, R.; Balbontín, J.; Calabuig, C.P.; Morlanes, V.; Ferrer, M. Does translocation affect short-term survival in a long-lived species, the Spanish imperial eagle? Anim. Conserv. 2021, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenward, R. E. Radio Tracking and Animal Populations; Academic Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- REE Mapa de instalaciones eólicas nacionales. 2019. Available online: www.esios.ree.es/es/mapas-de-interes/mapa-instalaciones-eolicas.

- Ferrer, M.; Harte, M. Habitat Selection by Immature Spanish Imperial Eagles During the Dispersal Period. J. Appl. Ecol. 1997, 34, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Corine Land Cover. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover/clc2018.

- Mellander, C.; Lobo, J.; Stolarick, K.; Matheson, Z. Night-Time Light Data: A Good Proxy Measure for Economic Activity? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvidge, C.D.; Zhizhin, M.; Ghosh, T.; Hsu, F.-C.; Taneja, J. Annual Time Series of Global VIIRS Nighttime Lights Derived from Monthly Averages: 2012 to 2019. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.D.; Ferraz, R.; Muñoz, A.-R.; Onrubia, A.; Wikelski, M. Black kites of different age and sex show similar avoidance responses to wind turbines during migration. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).