1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, endogenous RNA molecules, usually 19–25 nucleotides long that play a key role in regulating gene expression [

1,

2,

3]. They act by incorporating into the RISC complex, which then binds to target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) at the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) through sequence complementarity, leading to gene silencing [

4]. The resulting interaction normally leads to the inhibition of the target mRNA [

5], although cases of translational activation have also been found in literature [

6]. In this way a single miRNA is able to regulate hundreds of gene transcripts, and, on a genome-wide scale, it is estimated that miRNAs are able to control expression of up to 60% of genes in the human genome [

7], affecting virtually every physiological process. Starting from the initial discoveries of lin-4 and let-7 [

8], the number of known miRNAs has increased rapidly in recent years, with the latest miRbase (Release 22.1) counting about 38,000 entries [

9], underlining the evolutionary conservation and functional significance of these regulators. Dysregulation of miRNAs is associated to the pathogenesis of numerous complex human diseases [

10], in particularly in cancer [

11], cardiovascular [

12], neurodegenerative [

13], and metabolic diseases [

14]. For these reasons, identifying specific miRNA–disease associations (MDAs) is a useful step for understand disease mechanisms and for developing novel therapeutic strategies [

15]. Limitations of experimental approaches (PCR and high-throughput sequencing), which are typically resource-intensive, expensive, and time-consuming on a large scale [

16], have motivated the development of computational methods to predict potential miRNA–disease associations (MDAs) [

17,

18].

Many approaches exploit the large amount of of public data available today (like HMDD V2.0/V3.0 [

19,

20], dbDEMC [

21], and miR2Disease [

22] rely on the widely accepted principle that functionally similar miRNAs are likely to be associated with diseases exhibiting similar phenotypes [

23,

24].

Early computational approaches, which inferred MDAs by leveraging known interactions between miRNAs and their target genes or between target genes and diseases, often suffered from the incompleteness and noise of current miRNA–target interaction datasets. This category includes models based on Random Walk over protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks [

25] and methods like miRPD [

26] that uses intermediate networks to identify functional links between miRNAs and diseases.

To overcome these limitations, similarity-based network models were developed [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], integrating miRNA functional and disease semantic or phenotypic similarities with known MDAs. Approaches like HDMP [

34], used local similarity metrics, which proved ineffective for diseases lacking any known associated miRNAs ("new diseases"). This led to the development of sophisticated global network methods, for example those employing the Random Walk with Restart (RWR) algorithm (RWRMDA [

35], MIDP/MIDPE [

36]). By traversing the entire network RWR, provides a global view of connectivity, significantly improving performance. More advanced approaches involved integrating Gaussian Interaction Profile (GIP) Kernel similarity with functional/semantic similarity. Examples in this categories include WBSMDA [

37] and HGIMDA [

38], allowed for the calculation of similarity for new entities (miRNA or diseases) without prior associations, marking a significant leap toward predicting associations for both new miRNAs and new diseases.

Modern Machine Learning (ML) techniques provided more powerful tools to approach MDA prediction [

39,

40,

41]. They range from supervised classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [

42] and Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) [

43] to semi-supervised methods. A critical challenge for supervised learning is the difficulty in accurately obtaining reliable negative MDA samples. Addressing this, semi-supervised models like RLSMDA (Regularized Least Squares [

44]) and Matrix Completion (MC) methods, such as MCMDA [

45] were proposed. MCMDA, for instance, is highly efficient, operating only on the known positive MDA matrix by leveraging the assumption that the underlying adjacence matrix is low-rank, thereby inherently avoiding the need for negative samples. The high predictive power of MC methods was demonstrated by MCMDA, which achieved high AUC (87.49%) and a strong confirmation rate (up to 90% of top 50 predictions for diseases like prostate neoplasms). More recently, ensemble learning approaches such as ELMDA [

46] have been proposed, which do not rely on known associations to calculate miRNA and disease similarities and use multi-classifier voting for prediction, achieving an average AUC of 92.29% on HMDD v2.0, confirming the potential of ensemble strategies in accurately predicting disease-associated miRNAs.

The continuous development of these models now involves various forms of Deep Learning and Network Embedding and Graph Attention Networks (GAT) [

47,

48,

49] to capture complex, non-linear relationships within the integrated biological data.

Despite advances in computational prediction of miRNA–disease associations, key challenges remain. In particular, integrating heterogeneous biological data and capturing complex, non-linear relationships across miRNAs, diseases, and associated patterns is still difficult. Furthermore, limitations in data completeness and the dynamic nature of biological networks constrain model generalizability. Graph-based approaches, especially those leveraging message passing on heterogeneous networks, offer a natural framework to address these issues by propagating information across nodes and edges of multiple types, effectively learning embeddings that encode functional and phenotypic similarities.

In this work, we propose a Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network that models miRNA-disease associations by leveraging a multi-node, multi-edge approach to integrate diverse sources of information. Our model employs message passing and node-specific linear transformations to generate embeddings, enabling accurate prediction of miRNA–disease associations while efficiently handling new entities and heterogeneous network structures. Comparison with existing methods from the literature demonstrates improved performance in terms of AUC ROC in the prediction of true miRNA-disease associations.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

Performance was primarily assessed using AUC-ROC, which is the standard evaluation metrics in MDA prediction due to the highly imbalanced nature of MDA datasets (< 3% of positive samples). For comparison with other approach, we additionally computed the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPR), Precision, Recall, and F1-score, defined as:

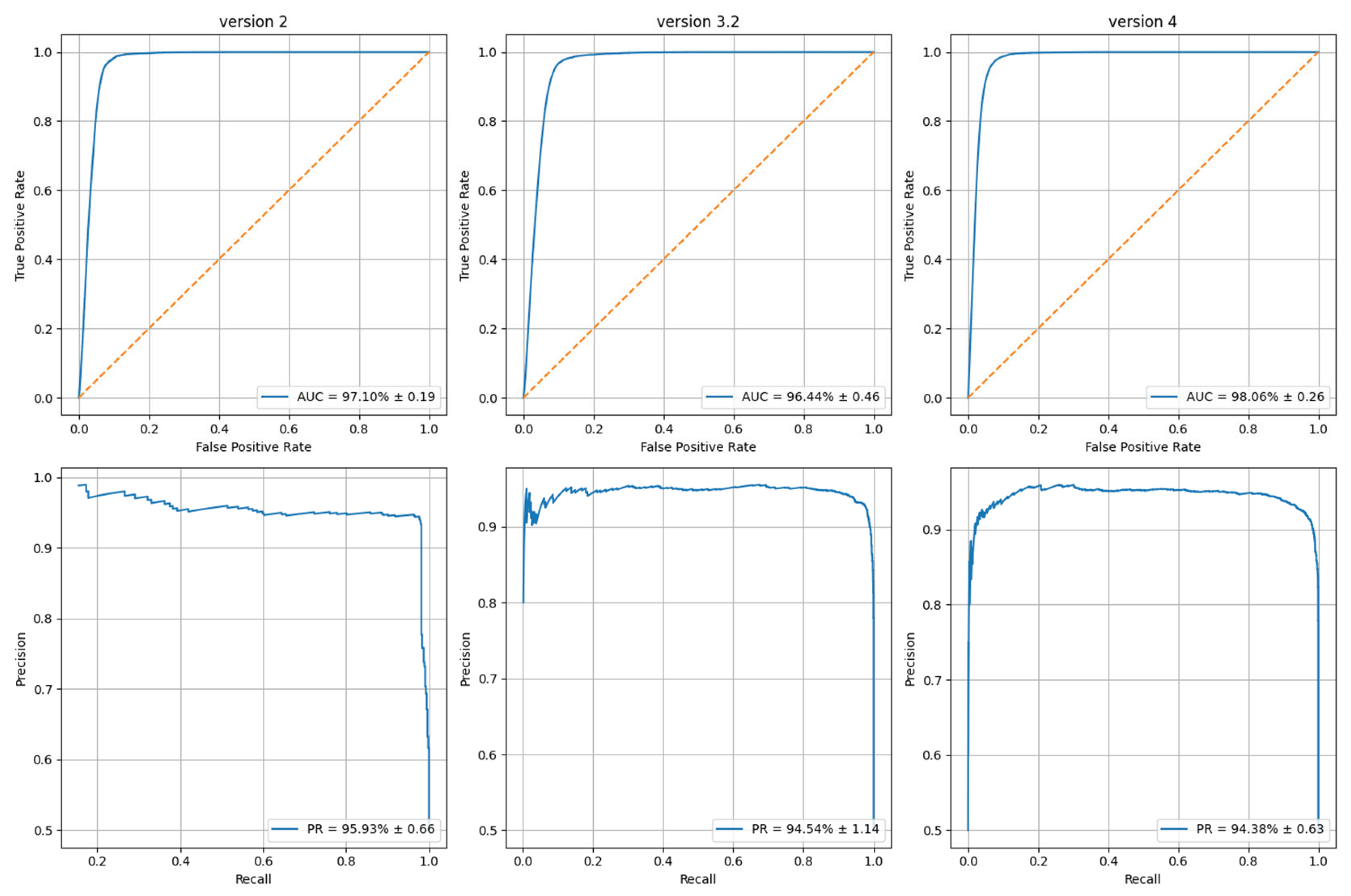

We first evaluated the proposed heterogeneous graph neural network on two benchmark datasets: HMDD v4.0, the most recent release, and HMDD v3.2 and v.2, widely used in prior computational studies, to facilitate direct comparison with the state of the art. All experiments were performed using the 10-fold cross-validation strategy described in

Section 2.3, with the entire evaluation repeated 10 times using different random partitions.

Across all repetitions on HMDD v4.0, the presented model achieved an average AUC-ROC of ~98% and an AUPR of ~95%, demonstrating strong discriminative capability also in the presence of class imbalance. Similar results were obtained on HMDD v3.2, where the AUC-ROC reached ~97–98% and the AUPR remained consistently above 94%.

Figure 5 reports the mean ROC and PR curves aggregated over all replications. The narrow confidence bands observed in both curves indicate high stability across validation folds and independent experiments.

3.2. Comparison with Existing Methods

To position the presented approach to current computational models, we compared it against several representative methods evaluated on HMDD v2. We first considered four widely used and powerful machine learning methods that are known to be able to handle complex features, but still constrained to vectorized feature representations: Support Vector Machine (SVM), a margin-based classifier effective in high-dimensional settings; the Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT), a sequential ensemble of decision trees using boosting to reduce errors; Random Forest (RF), an ensemble of decision trees; and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), a regularized boosting method offering strong predictive performance.

Traditional machine learning methods remain highly effective for structured biological prediction tasks, especially when relying on engineered similarity features or association profiles. Nevertheless, their inherent tabular representation of featues, inder their ability to capture heterogeneous, multi-relational graph structures. This limits their capacity to exploit the full topology of miRNA–disease–gene–pattern networks—an aspect naturally handled by graph neural architectures.

Next, we included in the comparison six more specialized tools: MDA-CF [

54], which leverages weighted hypergraph-based generalized matrix factorization to integrate multi-omics features of microbes and drugs, effectively predicting novel microbe-drug associations; TCRWMDA [

55], employing hypergraph-based logistic matrix factorization to capture higher-order relationships between metabolites and diseases, enabling accurate identification of disease-related metabolites; WBSMDA [

47], an attention-aware multi-view graph convolutional network combined with hypergraph learning to model miRNA–disease associations by integrating multiple similarity networks and fusing node information from diverse perspectives; ABMDA [

56], which explores miRNA-mediated mechanisms underlying disease progression and drug resistance, providing experimentally informed predictions of functional miRNA-disease links; ICFMDA [

57], a computational framework exploiting functional similarity and network inference to uncover potential miRNA–disease interactions; and ELMDA [

46], an ensemble learning approach that does not rely on known associations to calculate miRNA and disease similarities, combining multiple classifiers via voting to robustly predict disease-related miRNAs across diverse validation settings.

Compared to the most competitive methods—MDA-CF (AUC 92.58%) and ELMDA (AUC 92.29)—our heterogeneous graph-based approach improves performance by a substantial margin, highlighting the benefits of: Integrating heterogeneous biological relationships (miRNA–miRNA, disease–gene, miRNA–pattern, pattern–disease), Using message-passing to propagate functional signals across the network, and learning embedding representations directly from multiple node and edge types, rather than depending on pre-defined similarity kernels. These results indicate that the proposed model captures non-linear relationships more effectively than similarity-based or feature-engineering-based models.

Table 2 reports the performance metrics of the methods compared in this study, including AUC and AUPR and when available Precision, Recall and F1-score.

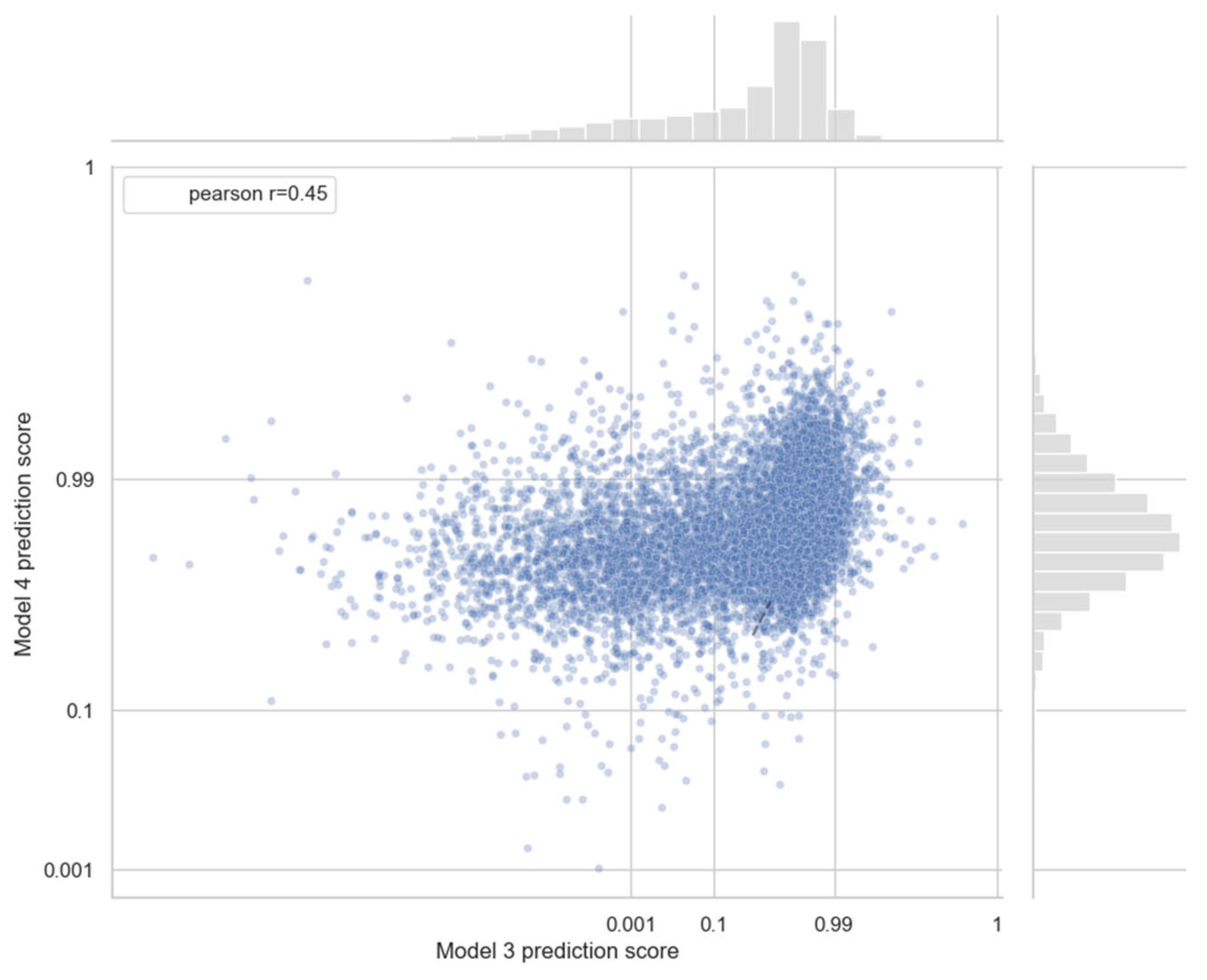

3.3. Analysis of Newly Predicted Associations

In order to evaluate the ability of our models to predict novel miRNA–disease associations, we performed a comparative analysis using two graph neural models trained on two different versions of the HMDD dataset: Model 3 was trained on HMDD v3.2, containing only the associations known at that time, whereas Model 4 was trained on the more comprehensive HMDD v4.0, which includes additional associations reported after v3.2. Both models were then applied to predict association scores for all new miRNA–disease pairs, those not previously observed by Model 3. Since Model 3 is built on a smaller knowledge base, we expect it to perform less accurately. The Pearson correlation between the prediction scores of the two models, shows a moderate correlation across all pairs (r ≈ 0.45), indicating that Model 3 is partially able to anticipate novel associations present in version 4 (

Figure 6). Moreover, the AUCROC for Model 3 considering only the previously unseen positive associations was 89%, indicating that the model successfully discriminates the majority of novel miRNA–disease links, further supporting its ability to anticipate associations absent from the training dataset.

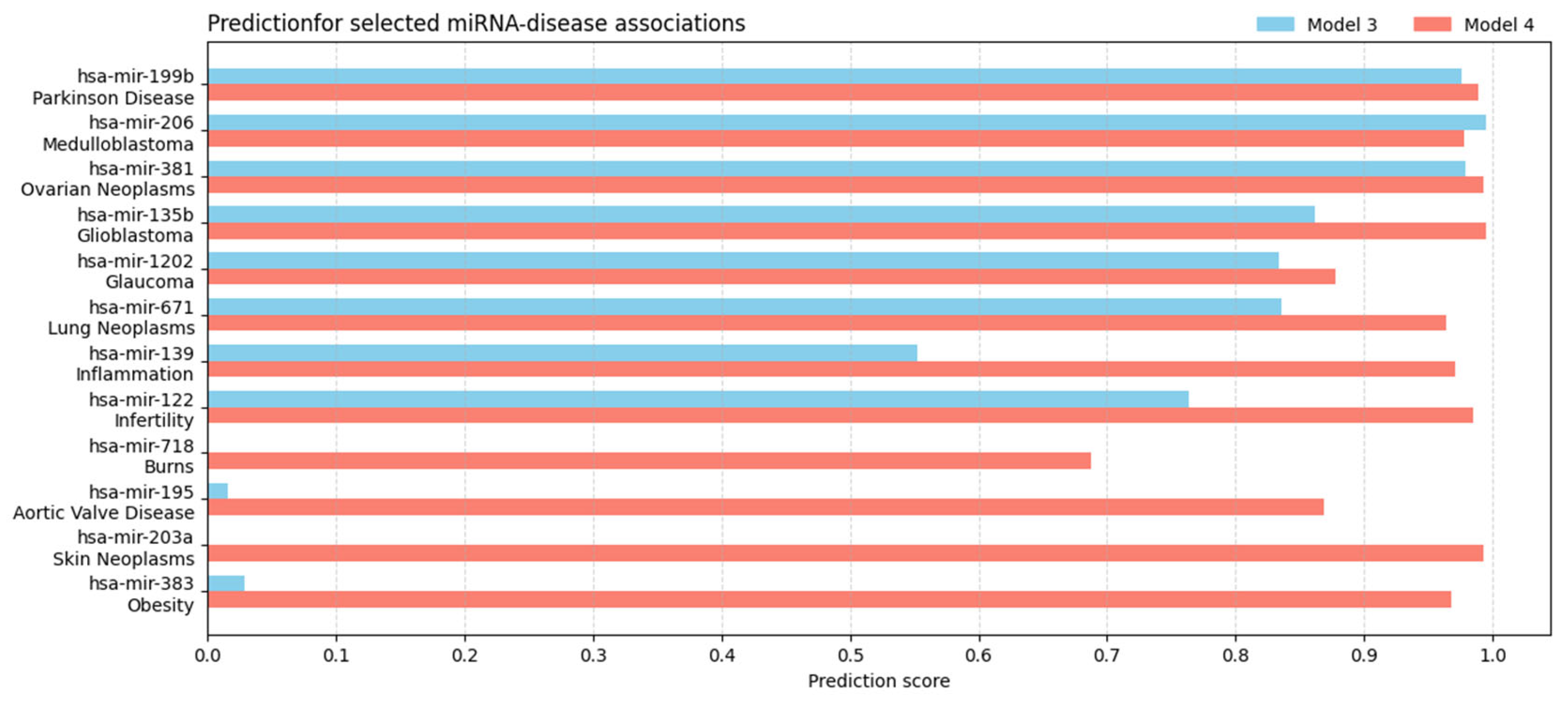

To further analyze these differences, we examined a subset of representative positive associations and visualized the corresponding prediction scores from both models (

Figure 7). Beyond simply contrasting the two score distributions, several patterns emerge: in many cases Model 4 assigns consistently higher confidence, reflecting the additional knowledge introduced in HMDD v4.0, while a number of pairs show near-identical scores, indicating that Model 3 successfully anticipates future annotations. Conversely, a few outliers (~15%) exhibit substantial divergence (aboslute score difference more than 0.5) between the two models, suggesting either overgeneralization by Model 3 or revised evidence incorporated in the updated dataset.

3.4. Ablation Analysis

Our heterogeneous graph neural network integrates multiple node types and relation-specific message passing to learn latent embeddings for miRNAs, diseases, genes, and sequence patterns. While the network is trained using the full set of edges, we observed that the model’s performance remains largely stable even when certain edge types are removed or perturbed. This indicates that the learned node embeddings capture significant information from node features themselves, and that the graph structure primarily provides additional contextual information rather than being strictly necessary for high predictive performance. Consequently, the predictive accuracy of miRNA–disease associations is robust with respect to partial or noisy graph information.

On the other hand we observe a different picture when the graph is perturbed before training. Specifically, ablating certain edge types prior to model training leads to significant drops in predictive performance, highlighting the importance of relational information during embedding learning. The quantitative effects of these pre-training ablations are reported in

Table 3, showing that edge information is crucial for guiding the model to capture biologically meaningful associations.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we presented a heterogeneous graph neural network framework for predicting miRNA–disease associations, leveraging the rich relational structure inherent in biological networks. Biological entities such as miRNAs, genes, diseases, and sequence motifs are naturally represented as nodes in a graph, with interactions forming edges of multiple types. Traditional machine learning approaches, which rely on tabular representations of features, often struggle to fully capture these complex, high-order relationships. In contrast, graph-based models excel at encoding both local and global structural patterns, allowing the integration of multiple types of biological information—ranging from sequence-derived features to gene–disease associations—within a unified latent space. This capability enables the model to infer indirect associations, identify hidden patterns, and generalize to previously unseen nodes with high accuracy.

Message-passing mechanisms within the network allow for effective propagation and aggregation of information, ensuring that the contribution of neighboring nodes is weighted according to their relevance, while attention-based layers enhance interpretability and robustness. Our experiments demonstrated that the model consistently achieves high predictive performance across multiple HMDD datasets, with narrow confidence intervals, confirming stability and reproducibility. Ablation and perturbation studies further highlighted the model’s sensitivity to network structure and its robustness to small levels of noise, underscoring the importance of accurately modeling heterogeneous interactions.

Despite these promising results, several limitations remain. While the model integrates diverse sources of biological information, the construction of the graph relies on pre-defined similarity measures and curated associations, which may overlook emerging or context-specific relationships. Future work could explore alternative strategies for graph construction, incorporating additional biological knowledge such as miRNA–target gene interactions, expression profiles across tissues or conditions, and temporal dynamics of disease progression. Moreover, integrating multi-omics data or environmental factors could enrich node features and edge relationships, improving prediction accuracy and providing deeper mechanistic insights. Advances in graph neural network architectures, including more sophisticated message-passing schemes or hierarchical graph representations, also offer avenues for performance enhancement and better interpretability.

Overall, this study confirms the strength of graph-based learning for miRNA–disease association prediction, demonstrating that modeling biological entities and their relationships as a heterogeneous network allows for accurate, robust, and generalizable inference. The proposed framework not only achieves state-of-the-art performance compared with existing methods, but also provides a flexible and extensible approach for future investigations, supporting the discovery of novel associations and facilitating hypothesis generation in translational research.

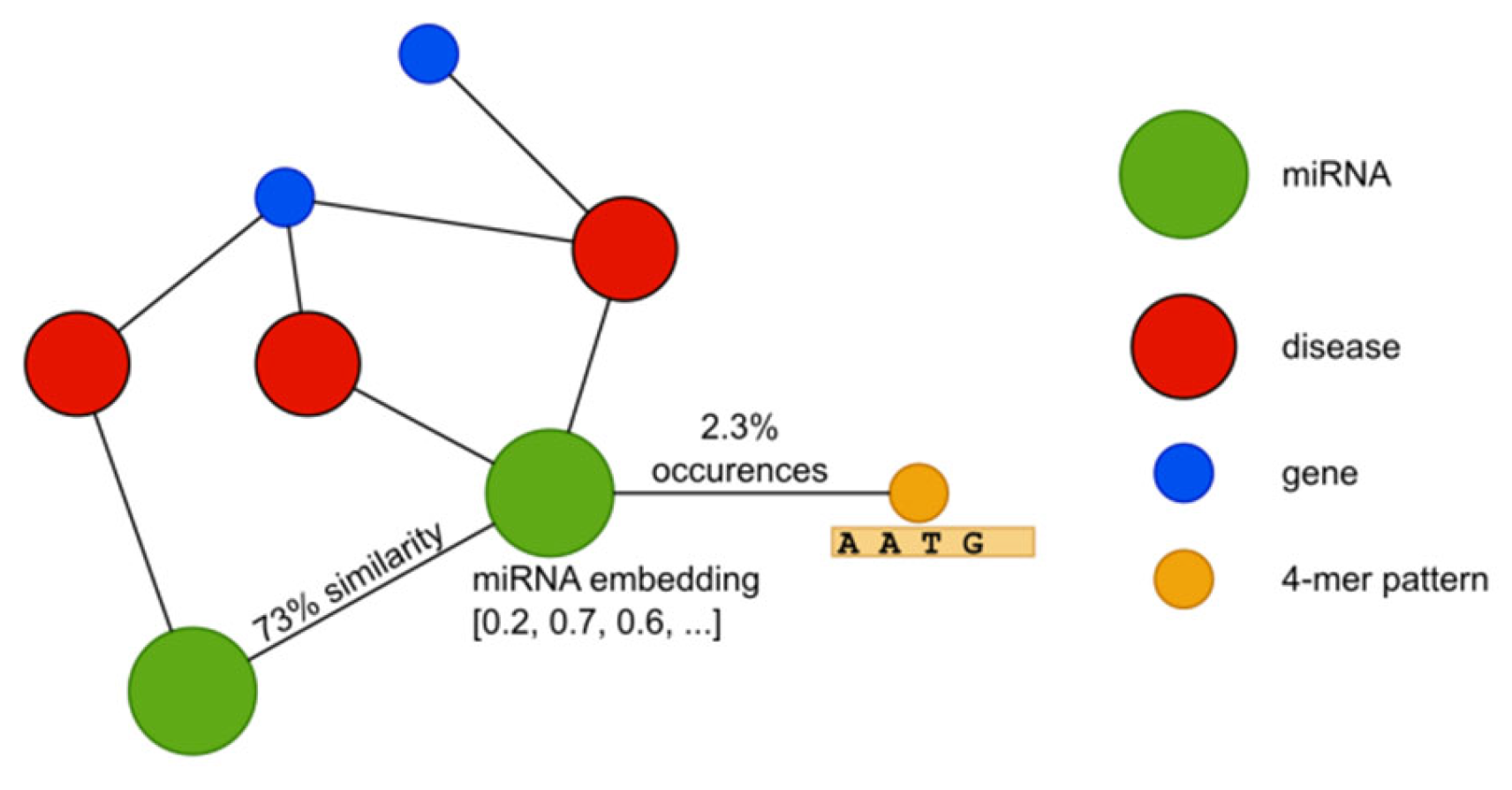

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of a portion of the heterogeneous biological network. Nodes correspond to miRNAs, diseases, genes, and sequence-derived patterns, while edges represent miRNA–disease associations, disease–gene links, sequence similarity, and motif-derived connections. Node colors indicate entity type, and edge colors indicate relationship type.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of a portion of the heterogeneous biological network. Nodes correspond to miRNAs, diseases, genes, and sequence-derived patterns, while edges represent miRNA–disease associations, disease–gene links, sequence similarity, and motif-derived connections. Node colors indicate entity type, and edge colors indicate relationship type.

Figure 2.

Network representation of a selected miRNA and its associations. The central green node represents the target miRNA. Red nodes indicate diseases associated with the miRNA, while blue nodes correspond to genes linked to those diseases. Orange nodes represent sequence patterns connected to the miRN.- Edges indicate relationships between nodes: miRNA–disease, disease–gene, miRNA–pattern and miRNA–miRNA,.

Figure 2.

Network representation of a selected miRNA and its associations. The central green node represents the target miRNA. Red nodes indicate diseases associated with the miRNA, while blue nodes correspond to genes linked to those diseases. Orange nodes represent sequence patterns connected to the miRN.- Edges indicate relationships between nodes: miRNA–disease, disease–gene, miRNA–pattern and miRNA–miRNA,.

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams showing the overlap of miRNAs (left) and diseases (right) across three versions of the HMDD database (v2, v3, and v4). The diagrams illustrate the number of shared and unique elements in each dataset version.

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams showing the overlap of miRNAs (left) and diseases (right) across three versions of the HMDD database (v2, v3, and v4). The diagrams illustrate the number of shared and unique elements in each dataset version.

Figure 4.

Overview of the heterogeneous graph neural network architecture used for miRNA–disease association prediction. The model integrates four node types (miRNAs, diseases, genes, and sequence patterns) connected through multiple biologically meaningful edge types. For each relation, a dedicated transformation matrix enables relation-specific message passing across the graph. Node embeddings are updated layer by layer through aggregation of messages from typed neighbors, followed by non-linear activation. After L message-passing layers, the learned embeddings of miRNAs and diseases are combined through a dot-product decoder to generate association scores.

Figure 4.

Overview of the heterogeneous graph neural network architecture used for miRNA–disease association prediction. The model integrates four node types (miRNAs, diseases, genes, and sequence patterns) connected through multiple biologically meaningful edge types. For each relation, a dedicated transformation matrix enables relation-specific message passing across the graph. Node embeddings are updated layer by layer through aggregation of messages from typed neighbors, followed by non-linear activation. After L message-passing layers, the learned embeddings of miRNAs and diseases are combined through a dot-product decoder to generate association scores.

Figure 5.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision–Recall (PR) curves obtained for the three evaluation datasets (HMDD v3.2, HMDD v4.0 and the combined heterogeneous dataset). Each curve represents the mean performance aggregated over all 10×10 replicated experiments, while the shaded regions denote the corresponding confidence bands. The tight variability observed across replications indicates the high stability of the model. The legend reports, for each dataset, the average AUC and AUPR (± their variance), confirming consistently strong predictive accuracy across all evaluation settings.

Figure 5.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision–Recall (PR) curves obtained for the three evaluation datasets (HMDD v3.2, HMDD v4.0 and the combined heterogeneous dataset). Each curve represents the mean performance aggregated over all 10×10 replicated experiments, while the shaded regions denote the corresponding confidence bands. The tight variability observed across replications indicates the high stability of the model. The legend reports, for each dataset, the average AUC and AUPR (± their variance), confirming consistently strong predictive accuracy across all evaluation settings.

Figure 6.

Comparison of prediction scores from Model 3 and Model 4 for selected miRNA–disease associations. Each point represents a miRNA–disease pair included in the analysis. The x-axis shows the prediction scores from Model 3, trained on HMDD v3.2, and the y-axis shows scores from Model 4, trained on the more complete HMDD v4.0 dataset. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.45) is reported in the legend, indicating moderate agreement between the two models while also revealing differences in predictions for novel associations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of prediction scores from Model 3 and Model 4 for selected miRNA–disease associations. Each point represents a miRNA–disease pair included in the analysis. The x-axis shows the prediction scores from Model 3, trained on HMDD v3.2, and the y-axis shows scores from Model 4, trained on the more complete HMDD v4.0 dataset. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.45) is reported in the legend, indicating moderate agreement between the two models while also revealing differences in predictions for novel associations.

Figure 7.

Bar plot comparing the prediction scores of Model 3 (trained on HMDD v3.2) and Model 4 (trained on HMDD v4.0) for a selected subset of positive miRNA–disease associations. Each row represents a single miRNA–disease pair, with the left bar indicating the score from Model 3 (blue) and the right bar the score from Model 4 (red). This visualization highlights both cases where Model 3 anticipates associations later reported in HMDD v4.0 and cases where the two models diverge, illustrating the models’ predictive behavior across heterogeneous scenarios.

Figure 7.

Bar plot comparing the prediction scores of Model 3 (trained on HMDD v3.2) and Model 4 (trained on HMDD v4.0) for a selected subset of positive miRNA–disease associations. Each row represents a single miRNA–disease pair, with the left bar indicating the score from Model 3 (blue) and the right bar the score from Model 4 (red). This visualization highlights both cases where Model 3 anticipates associations later reported in HMDD v4.0 and cases where the two models diverge, illustrating the models’ predictive behavior across heterogeneous scenarios.

Table 1.

Summary of the graph size for the three HMDD dataset versions. For each version, the number of miRNAs, diseases, genes, patterns, and the total number of edges in each relationship type are reported. Edge density is expressed as the percentage of observed associations over all possible associations.

Table 1.

Summary of the graph size for the three HMDD dataset versions. For each version, the number of miRNAs, diseases, genes, patterns, and the total number of edges in each relationship type are reported. Edge density is expressed as the percentage of observed associations over all possible associations.

| |

version 2 |

version 3.2 |

version 4 |

| nodes |

|

|

|

| miRNAs |

548 |

917 |

1183 |

| diseases |

383 |

853 |

2114 |

| genes |

6356 |

6356 |

6356 |

| patterns (4-mers) |

256 |

256 |

256 |

| |

|

|

|

| edges |

|

|

|

| miRNA–disease |

6331

(3.02%) |

15161

(1.94%) |

24074

(0.96%) |

miRNA–miRNA

similarity |

58814

(19.58%) |

133958

(15.93%) |

209186

(14.95%) |

disease–gene

|

11977

0.49%) |

13683

(0.25%) |

18617

(0.14%) |

miRNA–pattern

|

36602

(24.27%) |

58695

(25.0%) |

73515

(26.09%) |

| |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Comparison of different Machine Learning approaches proposed in literature reported from [

46]. The proposed approach (P.A. in the table) has been reported for all the three versions of the dataset. All other methods are evaluated on version 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of different Machine Learning approaches proposed in literature reported from [

46]. The proposed approach (P.A. in the table) has been reported for all the three versions of the dataset. All other methods are evaluated on version 2.

| Method |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

AUCROC |

AUPR |

| SVM |

83.69 ± 0.85 |

83.71 ± 1.43 |

83.70 ± 0.75 |

90.91 ± 0.31 |

90.57 ± 0.36 |

| GBDT |

83.69 ± 1.07 |

84.90 ± 0.57 |

84.29 ± 0.54 |

91.72 ± 0.34 |

91.38 ± 0.39 |

| RF |

84.24 ± 1.08 |

83.54 ± 1.31 |

83.88 ± 0.91 |

91.41 ± 0.49 |

91.23 ± 0.47 |

| XGBoost |

84.71 ± 0.90 |

84.86 ± 0.99 |

84.78 ± 0.76 |

91.91 ± 0.39 |

91.65 ± 0.45 |

| ELMDA |

84.85 ± 1.39 |

85.36 ± 1.01 |

85.10 ± 0.94 |

92.29 ± 0.35 |

92.17 ± 0.31 |

| MDA-CF |

- |

- |

- |

92.58 |

- |

| TCRWMDA |

- |

- |

- |

92.09 |

- |

| WBSMDA |

- |

- |

- |

81.85 |

- |

| ABMDA |

- |

- |

- |

90.45 |

- |

| ICFMDA |

N.A. |

N.A. |

N.A. |

90.23 |

N.A. |

| P.A. v2 |

92.02 ± 0.90 |

96.19 ± 0.90 |

94.06 ± 0.63 |

97.10 ± 0.19 |

95.93 ± 0.66 |

| P.A. v3 |

91.49 ± 1.09 |

94.79 ± 1.02 |

93.11 ± 0.92 |

96.44 ± 0.46 |

94.54 ± 1.14 |

| P.A. v4 |

94.94 ± 0.57 |

90.56 ± 1.79 |

92.70 ± 1.01 |

98.06 ± 0.26 |

94.38 ± 0.63 |

Table 3.

Comparison of different Machine Learning approaches proposed in literature reported from [

46]. The proposed approach (P.A. in the table) has been reported for all the three versions of the dataset. All other methods are evaluated on version 2.

Table 3.

Comparison of different Machine Learning approaches proposed in literature reported from [

46]. The proposed approach (P.A. in the table) has been reported for all the three versions of the dataset. All other methods are evaluated on version 2.

| Dropped edge |

Decrease AUC |

| miRNA–miRNA similarity |

5.4 % |

| disease–gene |

11.2 % |

| miRNA–pattern |

3.4 % |