Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

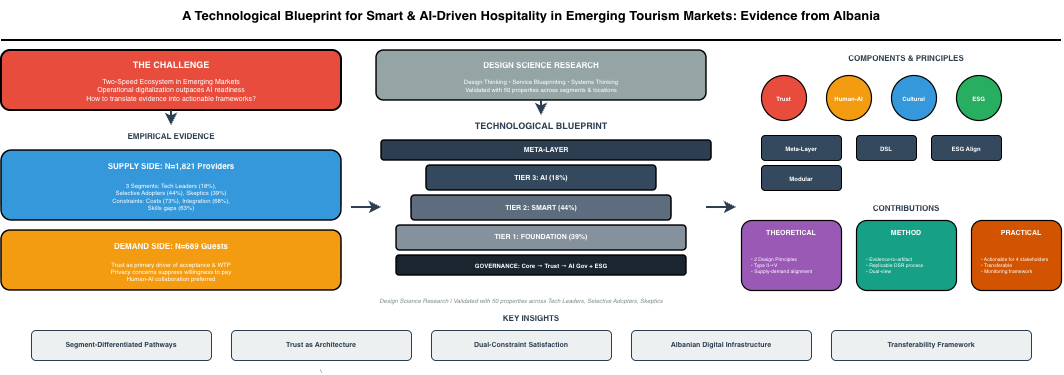

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Integrated TAM-TOE-DOI

2.2. Technology Adoption in Hospitality: Literature Synthesis

2.3. Empirical Evidence: Supply-Side Patterns

2.4. Empirical Evidence: Demand-Side Patterns

2.5. Design Requirements Synthesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design Science Research Framework

3.2. Design Thinking Process

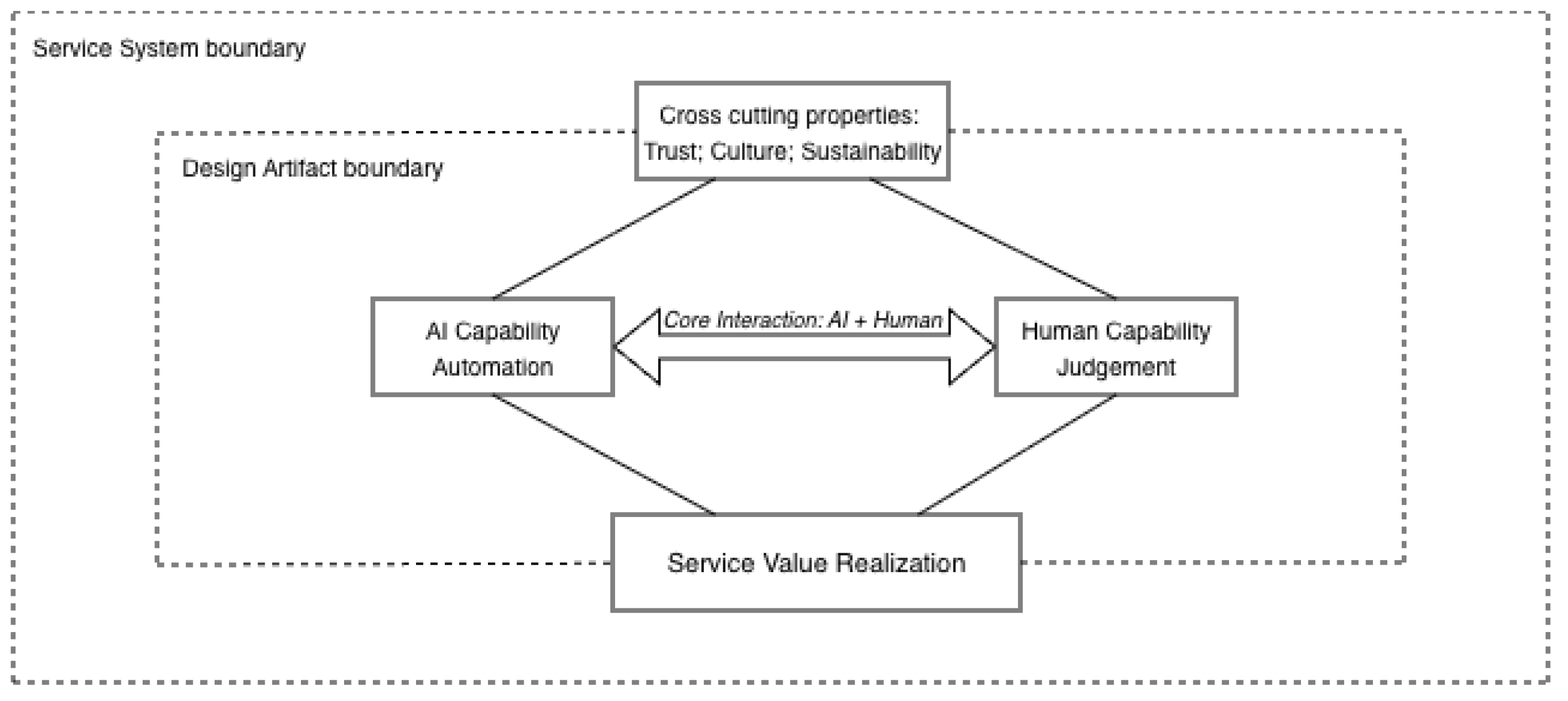

3.3. System Thinking Orientation

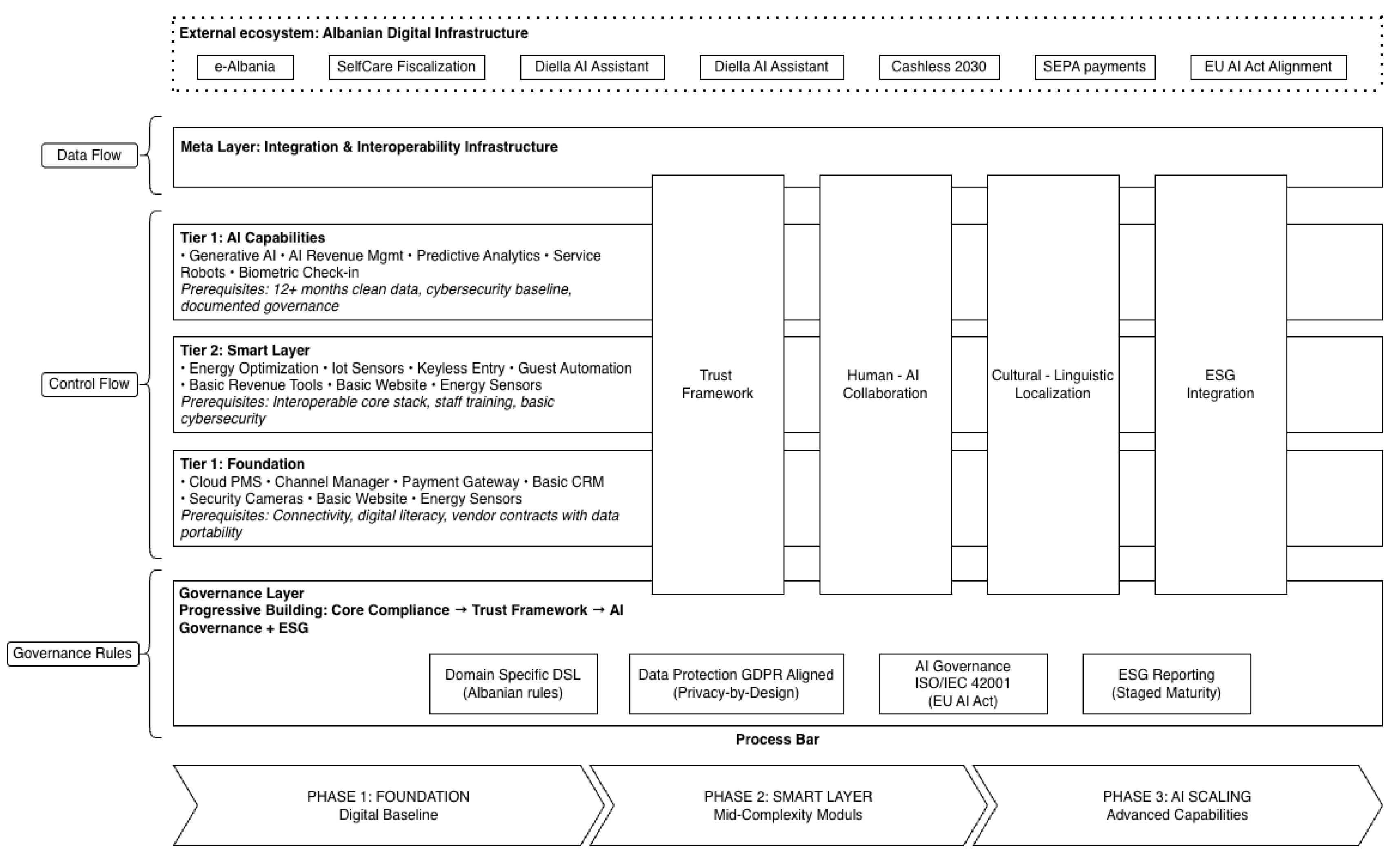

4. Results

4.1. Blueprint Architecture Principles

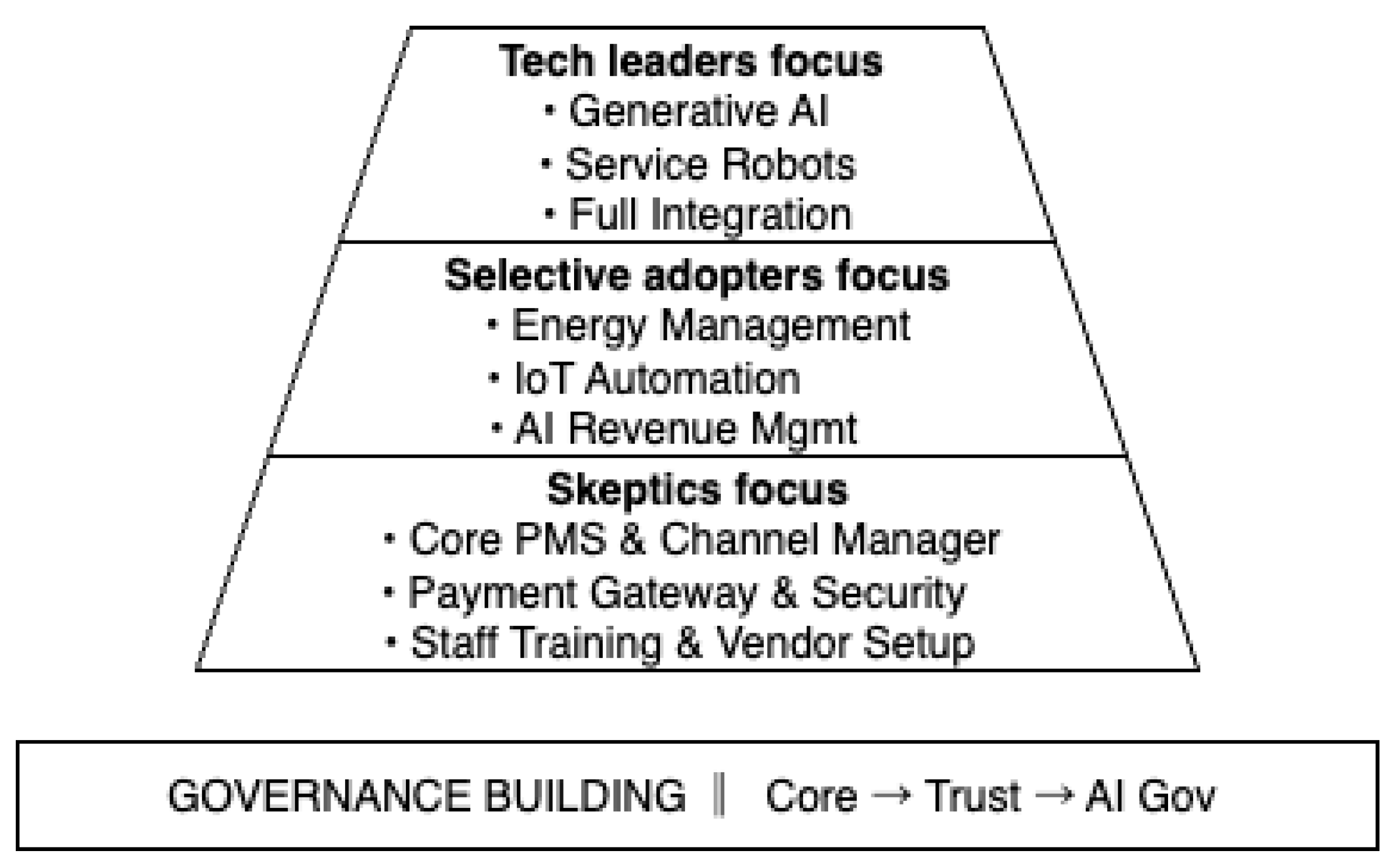

4.2. Segment-Differentiated Pathways

4.3. Cross-Cutting Components

4.4. Implementation Roadmap

4.5. Monitoring Framework

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Transferability and Limitations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| TAM | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| TOE | Technology-Organization-Environment |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovation |

| DSR | Design Science Research |

| AKSHI | National Agency for Information Society (Albania) |

| DSL | Domain-Specific Language |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| PMS | Property Management System |

References

- Godolja, M.; Tavanxhiu, T.; Sevrani, K. Strategic Readiness for AI and Smart Technology Adoption in Emerging Hospitality Markets: A Tri-Lens Assessment of Barriers, Benefits, and Segments in Albania. Tourism and Hospitality 2025, 6, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godolja, M.; Muka, R.; Tavanxhiu, T.; Sevrani, K. Guest Acceptance of Smart and AI-Enabled Hotel Services in an Emerging Market: Evidence from Albania. Tourism and Hospitality 2026, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhu, J.; Lee, S.; Zhou, D.; Song, W.; Ying, T. Digital Transformation in the Hospitality Industry: A Bibliometric Review from 2000 to 2023. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2024, 120, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T. The Digital Revolution in the Travel and Tourism Industry. Information Technology & Tourism 2019, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, S.; Yang, Y.; Zia, N.U.; Shah, M.H. Big Data Management Capabilities in the Hospitality Sector: Service Innovation and Customer Generated Online Quality Ratings. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 121, 106777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xue, T.; Yang, B.; Ma, B. A Digital Transformation Approach in Hospitality and Tourism Research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2023, 35, 2944–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.M.; Yu, B.T.W. Artificial Intelligence Research in Tourism and Hospitality Journals: Trends, Emerging Themes, and the Rise of Generative AI. Tourism and Hospitality 2025, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru; True), T.; Line, N.; Mody, M.; Hanks, L.; Abbott, J.; Acikgoz, F.; Assaf, A.; Bakir, S.; Berbekova, A.; Bilgihan, A.; et al. Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry: Developing a Framework for Future Research. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2025, 49, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J.; William Secin, E.; O’Connor, P.; Buhalis, D. Artificial Intelligence’s Impact on Hospitality and Tourism Marketing: Exploring Key Themes and Addressing Challenges. Current Issues in Tourism 2024, 27, 2345–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, J. From AI to Digital Transformation: The AI Readiness Framework. Business Horizons 2022, 65, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 Laying down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence and Amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act) (Text with EEA Relevance). 2024.

- Kim, B.-J.; Jeong, S.; Cho, B.-K.; Chung, J.-B. AI Governance in the Context of the EU AI Act. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 144126–144142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, J.; Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence and the European Union AI Act: On the Conflation of Trustworthiness and Acceptability of Risk. Regulation & Governance 2024, 18, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldemeyer, L.; Jede, A.; Teuteberg, F. Investigation of Artificial Intelligence in SMEs: A Systematic Review of the State of the Art and the Main Implementation Challenges. Management Review Quarterly 2024, 75, 1185–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahidi, F.; Kaluvilla, B.B.; Mulla, T. Embracing the New Era: Artificial Intelligence and Its Multifaceted Impact on the Hospitality Industry. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2024, 10, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Fan, S.; Zhang, K. Does Digital Transformation Exacerbate or Mitigate Maturity Mismatch in Hospitality and Tourism Firms? International Journal of Hospitality Management 2024, 123, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital Transformation: A Review, Synthesis and Opportunities for Future Research. Management Review Quarterly 2020, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Imgrund, F.; Janiesch, C.; Winkelmann, A. Strategy Archetypes for Digital Transformation: Defining Meta Objectives Using Business Process Management. Information & Management 2020, 57, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. Journal of Business Research 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satka, E.; Zendeli, F.; Kosta, E. Digital Services in Albania. European Journal of Development Studies 2023, 3, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinoimeri, D. The Impact of E-Governance Technologies on Public Service Delivery: Insights from e-Albania. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management 2025, 10, 653–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signing of Partnership Agreement with Messe Berlin. Available online: https://www.itb.com/en/itb-360°/newsroom/albania-is-the-host-country-of-itb-2025.html (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Ramosacaj, M.; Kushta, E. A Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Tourism on Economic Growth in Albania. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics. [CrossRef]

- Papp-Váry, Á.F.; Kadiu, A.; Szabó, Z. UNLOCKING SUSTAINABLE TOURISM THROUGH REGIONAL COLLABORATION: OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALBANIA AND THE WESTERN BALKANS. GTG 2025, 60, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liça, D.; Gashi, S. Attractiveness of Albania for Foreign Firms: An Analysis of Opportunities and Challenges. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research and Development 2024, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashi, S.; Qosja, E.; Liça, D. Hotels Industry: An Analysis of Business Approaches and Strategies. [CrossRef]

- Gjika, I.; Pano, N. Effects of ICT in Albanian Tourism Business. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, V.; Sinoimeri, D. Digital Transformation of Public Services in Albania: Evaluating the Impact of the e-Albania Platform. WSEAS Transactions on Information Science and Applications. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence, Real Politics: What Albania’s AI Minister Means for EU Accession | European Union Institute for Security Studies. Available online: https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/commentary/artificial-intelligence-real-politics-what-albanias-ai-minister-means-eu?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- EPC-Tirana. Available online: https://epctiranasummit.al/digital-revolution?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Diella. Albanian Government Council of Ministers.

- Kibirige, K.S.; Wandabwa, J. Enhancing Access to Service Delivery through Information Transparency: A RAG Based AI-Powered Conversational Chatbot for Algorithmic Transparency and Regulatory Compliance in Digital Governance. International Journal of Computational Science and Engineering Research 2025, 14, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savveli, I.; Rigou, M.; Balaskas, S. From E-Government to AI E-Government: A Systematic Review of Citizen Attitudes. Informatics 2025, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadani, L.; Doko, F. Exploring RAG Solutions for a Specific Language: Albanian. European Journal of Information Technologies and Computer Science 2025, 5, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, E.; Mulla, G.; Vukatana, K. A Proposed Mobile Bill Payment Business Solution Based on the New Fiscalization Process in Albania. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimaj: 60% of Payments in Albania to Be Digital by 2030 | Albanian Telegraphic Agency. Available online: https://en.ata.gov.al/2025/12/04/ibrahimaj-60-of-payments-in-albania-to-be-digital-by-2030/ (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Albania Joins SEPA: Sending Money to and from Albania Just Got Cheaper and Faster | EEAS. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/albania/albania-joins-sepa-sending-money-and-albania-just-got-cheaper-and-faster_en (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Jantoń-Drozdowska, E.; Mikołajewicz-Woźniak, A. The Impact of the Distributed Ledger Technology on the Single Euro Payments Area Development. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 2017, 12, 519?535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chan, C.-S. A Systematic Literature Review on Payment Methods in Hospitality and Tourism. Information Technology & Tourism 2025, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawira, M.F.A.; Susanto, E.; Goeltom, A.D.L.; Furqon, C. Developing Cashless Tourism from a Tourist Perspective: The Role of TAM and AMO Theory. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 2022, 13, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryyev, G.; Spyridou, A.; Yeh, S.; Lo, C.-C. Factors of Digital Payment Adoption in Hospitality Businesses: A Conceptual Approach. European Journal of Tourism Research 2021, 29, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. Journal of Management Information Systems Available online. Vol 24, No 3, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240302. (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Julies, B.; Zuva, T. A Review on TAM and TOE Framework Progression and How These Models Integrate. Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal 2021, 6, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zin, R.M. Unraveling the Dynamics of User Acceptance on the Internet of Things: A Systematic Literature Review on the Theories and Elements of Acceptance and Adoption. Journal of Electrical Systems 2024, 20, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjondronegoro, D.; Yuwono, E.; Richards, B.; Green, D.; Hatakka, S. Responsible AI Implementation: A Human-Centered Framework for Accelerating the Innovation Process 2022.

- Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Zhou, B.; Liu, J. Artificial Intelligence Applications and Corporate ESG Performance. International Review of Economics & Finance 2025, 104, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Zobi, M.A.; Alomair, M. Artificial Intelligence, ESG Governance, and Green Innovation Efficiency in Emerging Economies. Economies 2025, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Jung, T.; Koo, I. AI-Led ESG, ESG-Led AI: A Strategic Convergence for Sustainable Transformation. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveland, J.; Tornatzky, L.G. Technological Innovation as a Process; 1990; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition ed; Simon and Schuster, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdali, S.A.; Pileggi, S.F. A Research Framework to Identify Determinants for Smart Technology Adoption in Rural Regions. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, M.; Mudgal, R.K. Applications of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference System Modeling and Advancement in Research Trends (SMART), November 2019; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, P.E.; Thatcher, J.B.; Chudoba, K.M.; Marett, K. Post-Acceptance Intentions and Behaviors: An Empirical Investigation of Information Technology Use and Innovation. Available online: https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx? [CrossRef]

- Julies, B.; Zuva, T. A Review on TAM and TOE Framework Progression and How These Models Integrate. Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal 2021, 6, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 3. ed.; Free Press [u.a.]: New York, NY, 1983; ISBN 978-0-02-926650-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.; Bang, Y. Understanding Continuance Intention of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): TOE, TAM, and IS Success Model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Heo, S.; Han, S.; Shin, Y.; Roh, Y. Acceptance Model of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Based Technologies in Construction Firms: Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in Combination with the Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) Framework. Buildings 2022, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doborjeh, Z.; Hemmington, N.; Doborjeh, M.; Kasabov, N. Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Methods and Applications in Hospitality and Tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2021, 34, 1154–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart Hospitality—Interconnectivity and Interoperability towards an Ecosystem. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Dutt, C.S.; Chathoth, P.; Daghfous, A.; Khan, M.S. The Adoption of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the Hotel Industry: Prospects and Challenges. Electronic Markets 2020, 31, 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Cui, Q.; Lan, T. Artificial Intelligence in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Széchenyi István; Erdős, F.; Thinakaran, R.; Firuza, B.; Koloszár, L. THE RISE OF AI IN TOURISM - A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW. GTG 2025, 60, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Lin, K.J.; Ye, H.; Fong, D.K.C. Artificial Intelligence Research in Hospitality: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Directions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2023, 36, 2049–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Chelaru, M.; Czakon, W. Adoption and Performance Outcome of Digitalization in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Review of Managerial Science 2024, 19, 2011–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, A.N.; Choong, Y.O.; Low, M.P.; Ismail, N.H.; Choong, C.K. Building Tourism SMEs’ Business Resilience through Adaptive Capability, Supply Chain Collaboration and Strategic Human Resource. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2024, 32, e12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, N.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Marzi, G.; Michopoulou, E. The Complexity of Decision-Making Processes and IoT Adoption in Accommodation SMEs. Journal of Business Research 2021, 131, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaculčíková, Z.; Ramkissoon, H.; Dey, S.K. Circular Intentions, Minimal Actions: The Psychology of Doing Less in Hospitality – An Integrative Review. Acta Psychologica 2025, 259, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Contreras, R.; Álvarez, M.J.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M.; Rodriguez-Ferradas, M.I.; Morer-Camo, P. Towards the Implementation of the Smart Circular Economy for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework of Barriers and Drivers in the Hospitality Sector. Sustainable Development 2025, 33, 8923–8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanchian, M.; Taherdoost, H. Barriers and Enablers of AI Adoption in Human Resource Management: A Critical Analysis of Organizational and Technological Factors. Information 2025, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Kayande, U.; Srivastava, R.K. What’s Different About Emerging Markets, and What Does It Mean for Theory and Practice? Customer Needs and Solutions 2015, 2, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xing, X.; Duan, Y.; Cohen, J.; Mou, J. Will Artificial Intelligence Replace Human Customer Service? The Impact of Communication Quality and Privacy Risks on Adoption Intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 66, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Zhang, T.; Lin, Z. (CJ); Peng, Q. Hotel AI Service: Are Employees Still Needed? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 55, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M. Engaging and Retaining Customers with AI and Employee Service. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 56, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence Misuse and Concern for Information Privacy: New Construct Validation and Future Directions - Menard - 2025 - Information Systems Journal - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/isj.12544. (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Asif, N.H.; Mahmud, M.; Rahman, M.W.; Islam, M.B. The Trust Paradox in AI-Driven Customer Support: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Human vs. AI Trust. American Journal of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence 2025, 1, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willingness-to-Pay for Robot-Delivered Tourism and Hospitality Services – an Exploratory Study. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.; Hazel, S. Towards Interculturally Adaptive Conversational AI. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, A.M.; Galindo-Pérez-de-Azpillaga, L.; Foronda-Robles, C. The Flow of Digital Transition: The Challenges of Technological Solutions for Hotels. Social Indicators Research 2025, 178, 1323–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Smith, S.; Ricci, P.; Bujisic, M. Hotel Guest Preferences of In-Room Technology Amenities. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 2016, 7, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zave, P.; Jackson, M. Four Dark Corners of Requirements Engineering. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 1997, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S. What Is a Framework? Understanding Their Purpose, Value, Development and Use. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2023, 13, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.; R, A.; March, S.; T, S.; Park; Park, J.; Ram. Sudha Design Science in Information Systems Research. Management Information Systems Quarterly 2004, 28, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckler, C.; Mauer, R.; vom Brocke, J.; Hanisch, M.; Schrage, S.; Terzidis, O.; Weißenberger, B.E. Design Science Across Disciplines: Building Bridges for Advancing Impactful Business Research. Schmalenbach Business Review 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender-Salazar, R. Design Thinking as an Effective Method for Problem-Setting and Needfinding for Entrepreneurial Teams Addressing Wicked Problems. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2023, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Earthscan: London, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-726-7. [Google Scholar]

- March, S.T.; Smith, G.F. Design and Natural Science Research on Information Technology. Decision Support Systems 1995, 15, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S. The Nature of Theory in Information Systems1. MIS Quarterly 2006, 30, 611–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Writing My next Design Science Research Master-Piece: But How Do I Make a Theoretical Contribution to DSR? ECIS 2015 Completed Research Papers 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distinguishing and Contrasting Two Strategies for Design Science Research: European Journal of Information Systems. No 1 - Get Access Available online. Vol 24. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1057/ejis.2013.35. (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Baskerville, R.; Baiyere, A.; Gregor, S.; Hevner, A.; Rossi, M. Design Science Research Contributions: Finding a Balance between Artifact and Theory. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, J.; Pries-Heje, J.; Baskerville, R. FEDS: A Framework for Evaluation in Design Science Research. European Journal of Information Systems 2016, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.R.; Parsons, J.; Brendel, A.B.; Lukyanenko, R.; Tiefenbeck, V.; Tremblay, M.C.; vom Brocke, J. Transparency in Design Science Research. Decision Support Systems 2024, 182, 114236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, F.; Jakeman, A.J.; Elsawah, S.; Guillaume, J.H.A. Bridging Practice and Science in Socio-Environmental Systems Research and Modelling: A Design Science Approach. Ecological Modelling 2024, 492, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtka, J. Perspective: Linking Design Thinking with Innovation Outcomes through Cognitive Bias Reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2015, 32, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlgren, L.; Rauth, I.; Elmquist, M. Framing Design Thinking: The Concept in Idea and Enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management 2016, 25, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, P.; Wilner, S.J.S.; Bhatti, S.H.; Mura, M.; Beverland, M.B. Doing Design Thinking: Conceptual Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2019, 36, 124–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.; Miller, S.E.; Sochacka, N.W. A Model of Empathy in Engineering as a Core Skill, Practice Orientation, and Professional Way of Being. Journal of Engineering Education 2017, 106, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson-Sköldberg, U.; Woodilla, J.; Çetinkaya, M. Design Thinking: Past, Present and Possible Futures. Creativity and Innovation Management 2013, 22, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorst, K. The Core of ‘Design Thinking’ and Its Application. Design Studies 2011, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winby, S.; Mohrman, S.A. Digital Sociotechnical System Design. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 2018, 54, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A. Multiple Perspectives: Concept, Applications, and User Guidelines. Systems practice 1989, 2, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.W. Overview of Complex System Design 2025.

- Sterman, J. System Dynamics Modeling: Tools for Learning in a Complex World. In Engineering Management Review; IEEE, 2002; Volume 43, pp. 42–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.D. Systems Thinking for Information Systems Development. Systems practice 1995, 8, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingens, B.; Miehé, L.; Gassmann, O. The Ecosystem Blueprint: How Firms Shape the Design of an Ecosystem According to the Surrounding Conditions. Long Range Planning 2021, 54, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraj, A.H.A.; Hasanein, A.M.; Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Elziny, M.N. Redefining the Digital Frontier: Digital Leadership, AI, and Innovation Driving Next-Generation Tourism and Hospitality. Administrative Sciences 2025, 15, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadan, A.; Dabiri, A. Factors Influencing Human Trust in Intelligent Built Environment Systems. AI and Ethics 2025, 5, 5841–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective. Wiley. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Systems+Thinking%2C+Systems+Practice%3A+Includes+a+30-Year+Retrospective-p-9780471986065 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Gorton, I.; Teja Rayavarapu, V. Foundations of Scalable Software Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C), March 2022; pp. 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan, V.; Anand, S.; Kunti, K. Shared Data Services: An Architectural Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS’05), July 2005; p. 690. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna, C.; Yetgin, H.; Mohorčič, M. Smart Infrastructures: Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Lifecycle Automation. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2023, 17, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems of Systems Thinking | Springer Nature Link (Formerly SpringerLink). Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-00114-8_44 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Birukou, A.; D’Andrea, V.; Leymann, F.; Serafinski, J.; Silveira, P.; Strauch, S.; Tluczek, M. An Integrated Solution for Runtime Compliance Governance in SOA. [PubMed]

- Caracciolo, A.E.F. On the Evaluation of a DSL for Architectural Consistency Checking. [CrossRef]

- Bosak, K.; McCool, S.F. Tourism and Sustainability: Transforming Global Value Chains to Networks; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kusiak, A. Integrated Product and Process Design: A Modularity Perspective. Journal of Engineering Design 2002, 13, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ostwald, M.J.; Gu, N. Design Thinking and the Digital Ecosystem; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maciaszek, L.A. An Architectural Style for Trustworthy Adaptive Service Based Applications.

- Ngo, V.M. Balancing AI Transparency: Trust, Certainty, and Adoption. Information Development 2025, 02666669251346124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V.; Chadha, K.K. Culturally Responsive AI Chatbots: From Framework to Field Evidence. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2025, 6, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censi, R.; Campana, P.; Bellini, F.; Schettino, F.; De Pucchio, C. AI-Driven Process Mining for ESG Risk Assessment in Sustainable Management. Buildings 2025, 15, 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, N.; Wattiau, I.; Akoka, J. Artifact Evaluation in Information Systems Design Science Research ? A Holistic View. Proceedings - Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, C.; Martinez, A. Enhancing Reliability Through Effective System Monitoring. Science and Technology 2024, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Katragadda, V. Measuring ROI of AI Implementations in Customer Support: A Data-Driven Approach. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) ISSN:3006-4023 2024, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D.; Borenstein, J.; Biddle, J.; Laas, K. AI Ethics in the Public, Private, and NGO Sectors: A Review of a Global Document Collection. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 2021, 2, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deri, M.; Ari Ragavan, N. Digital Future of the Global Hospitality Industry and Hospitality Education: Review of Related Literature. Asia-Pacific Journal of Futures in Education and Society 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evidence Pattern | Design Requirement |

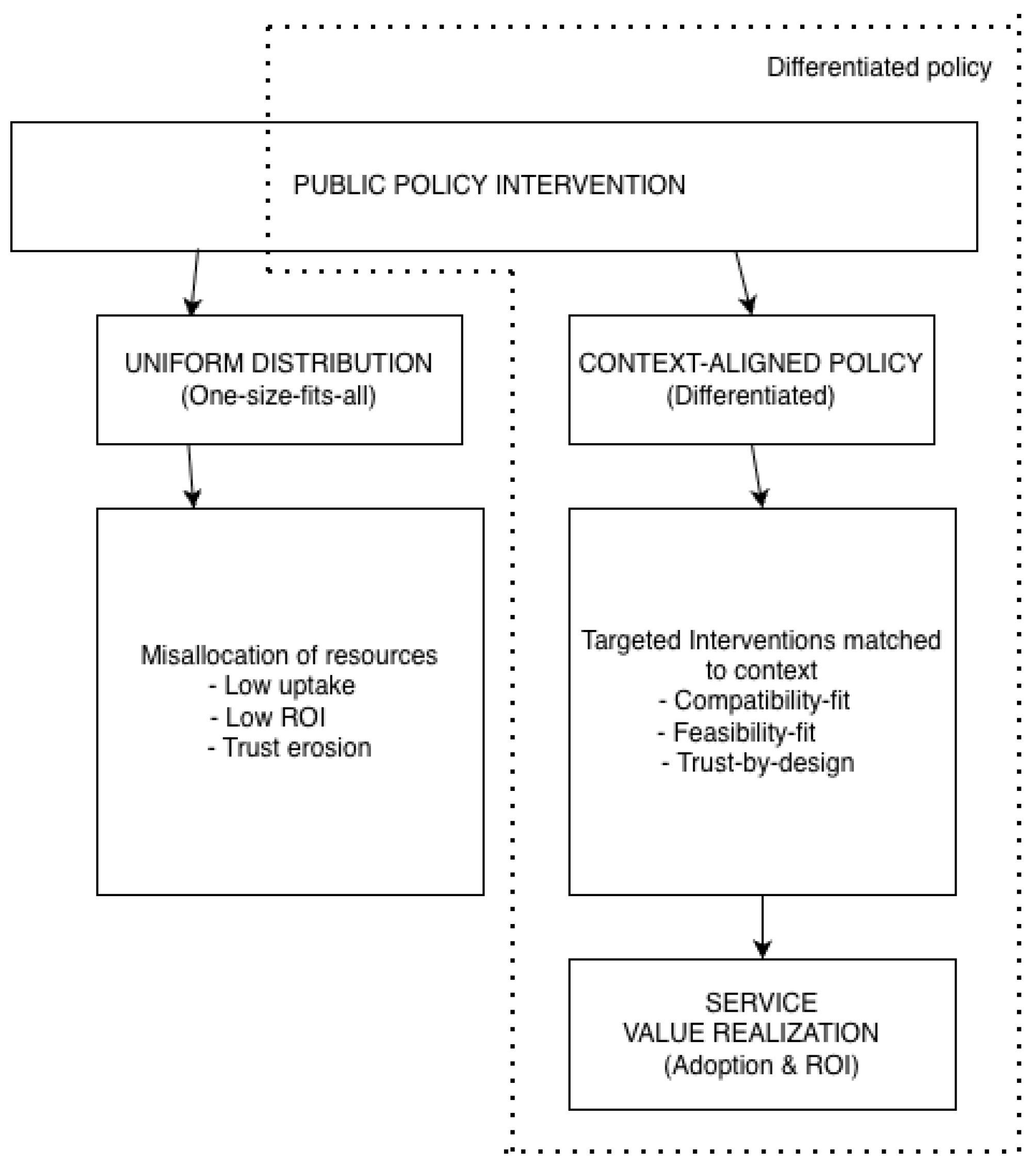

| Provider segmentation: Tech Leaders (18%), Selective (44%), Skeptics (39%) | Differentiated implementation pathways |

| Dominant barriers: Costs (73%), Integration (68%), Skills (63%) | Modular, incremental architecture |

| Two-speed adoption: Core (37-51%) vs. AI (9%) | Staged progression: Core → Smart → AI |

| Regional context > property size | Ecosystem-sensitive recommendations |

| Evidence Pattern | Design Requirement |

| Trust drives acceptance and WTP | Trust-by-design architectural layer |

| Privacy concerns suppress WTP | Transparency framework, opt-in controls |

| Preference for collaboration over replacement | Hybrid human-AI service models |

| Cultural-linguistic fit matters | Albanian localization requirement |

| Depersonalization moderated by trust | Human escalation pathways, visible agency |

| Phase | Activity | Evidence Input | Output |

| Problem Identification | Define problem space | Session 2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background | Problem statement |

| Solution Objectives | Specify requirements | Subsection 2.5. Design requirements Synthesis | Objective specifications |

| Design & Development | Construct artifact | Design Thinking process | Blueprint prototype |

| Demonstration | Present prototype | Stakeholder presentations | Refined design |

| Evaluation | Validate utility | Feedback gathering from properties | Validated blueprint |

| Communication | Document artifact | This paper | Publish the framework |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.