Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Temporal coupling and queue awareness, achieved through a time-evolving model that tracks each vehicle across successive time slots, preserving internal states such as queue content and retransmission history. This allows the resource allocation process to account for the outcome of previous transmissions, ensuring a temporally consistent and fair system behavior;

- Realistic traffic modeling, by incorporating heterogeneous data generation patterns, including periodic event-driven transmissions and probabilistic schemes where new packets are generated as soon as the transmission queue is emptied. This enables the framework to reflect both sporadic and continuous communication behaviors typical of Vehicle-To-Everything (V2X) applications [27].

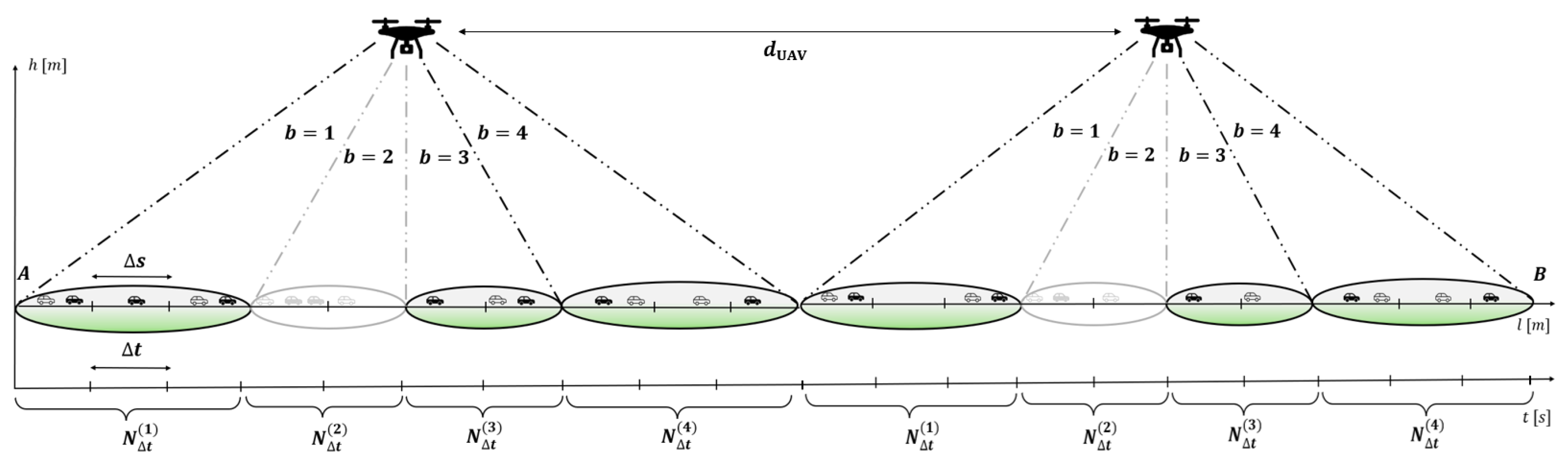

3. System Model

3.1. Reference Scenario and Application

3.2. Beamforming and Path Loss Model

4. The Radio Resource Assignment Process

| Symbol | Description | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of serving UAVs | Number of available beams | ||

| Number of RF chains | RRA interval duration | ||

| k | Time interval index | Total traversal time intervals | |

| ℓ | Beam index | Travel time from A to B | |

| Spatial segments in beam ℓ | TDMA frames in beam ℓ | ||

| v | Vehicle speed | U | Maximum servable vehicles per RRA interval |

| Beam traversal intervals | Minimum discretized road segment length | ||

| M | Maximum number of vehicles per segment () | Vehicle length | |

| Probability of a vehicle in slot | Vehicle density | ||

| Average vehicles per segment () | Packet generation probability at interval k | ||

| Minimum packet generation probability | Maximum packet generation probability | ||

| T | Period between consecutive packet generation events | CAVs with queued packet | |

| CAVs without queued packet | Accessing CAVs | ||

| Successful CAVs | Failed CAVs | ||

| Average CAVs with queued packet | Average CAVs without queued packet | ||

| Average accessing CAVs | Average successful CAVs | ||

| Average failed CAVs | Probability of having a queued packet | ||

| Probability of newly generated packet | Connection probability | ||

| Activation probability | Blocking probability | ||

| SNR threshold | Average SNR in the ℓth beam | ||

| Mean of average SNR in beam ℓ | Standard deviation of average SNR in beam ℓ | ||

| Average success probability | Success probability | ||

| Network throughput | Average user throughput |

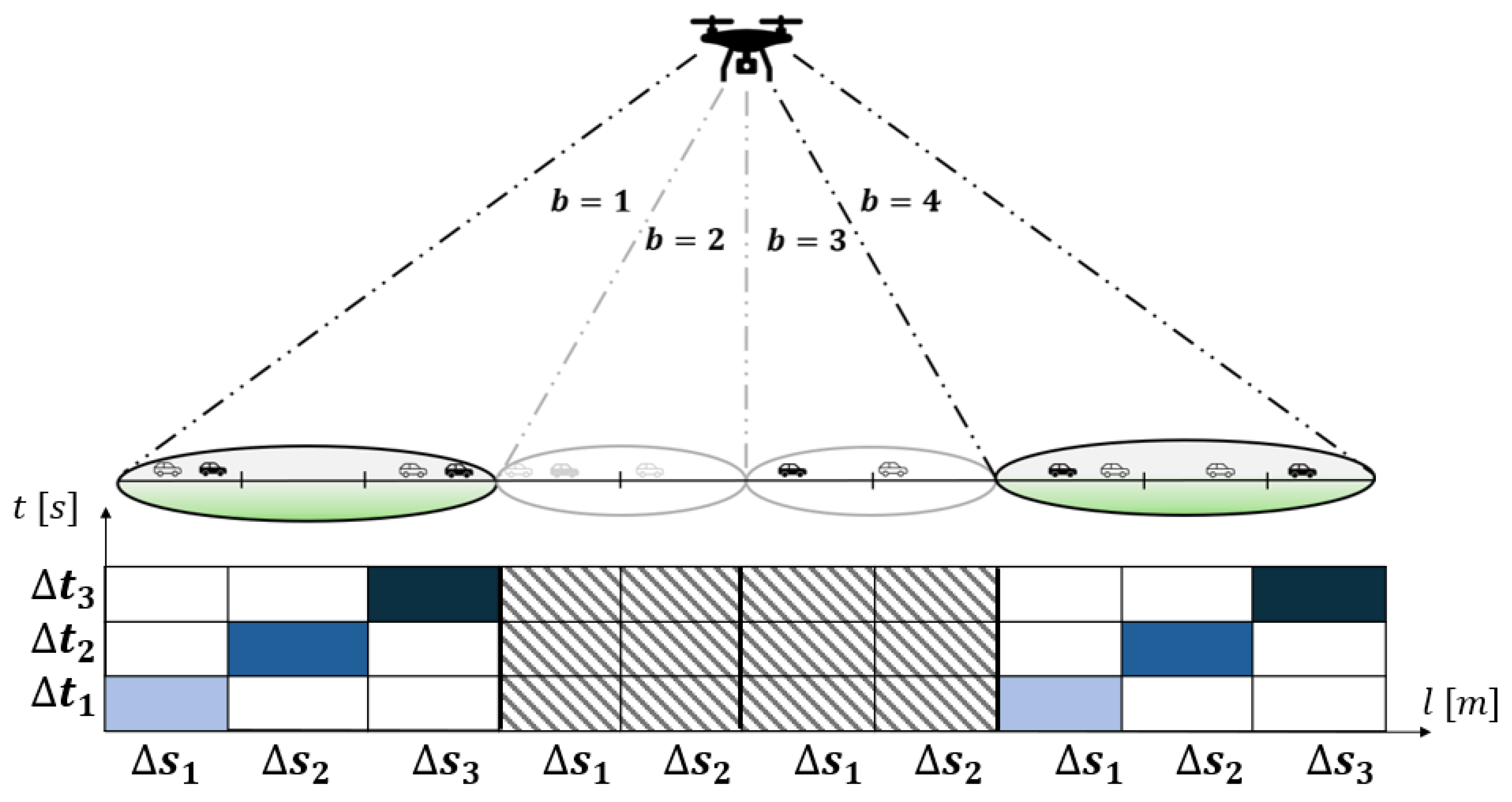

5. Traffic Model: Mobility and Data Generation

5.1. Notation

5.2. CAVs Mobility and Distribution

5.3. Data Generation Model

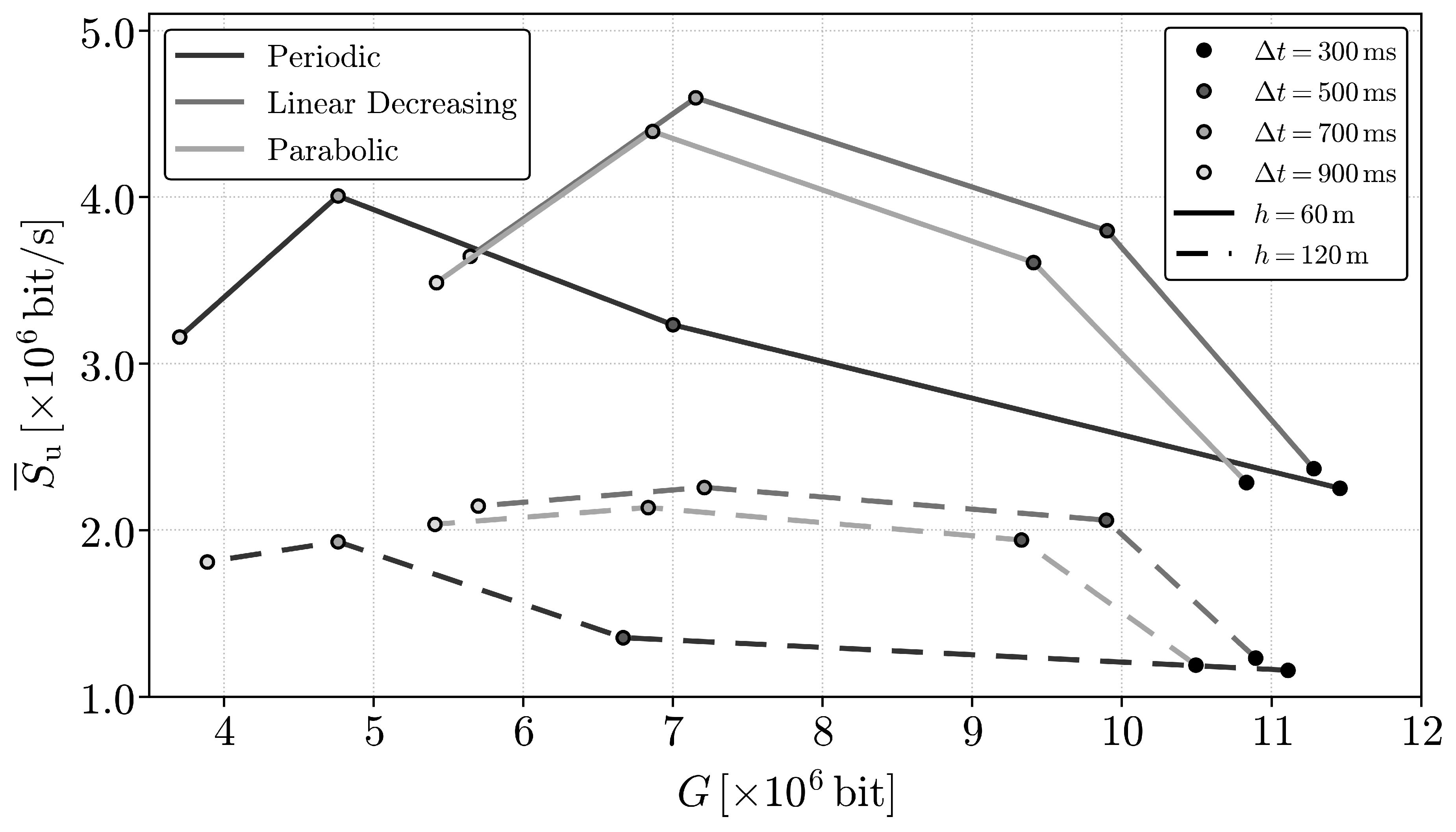

5.3.1. Probabilistic Traffic Model

- Parabolic traffic pattern. In this scenario, each CAV entering the system at point A is assumed to have an initial queued packet with probability . As the vehicle traverses the road segment and successfully transmits its queued packet, the probability of generating a new packet increases progressively, reaching a maximum value, , at the midpoint of the segment (i.e., when ). Thereafter, the packet generation probability decreases, reverting to by the time the vehicle reaches point B (i.e., at ). The expression governing is then given bywhere .

- Linear decreasing traffic pattern. In this case, vehicles entering the system have a queued packet with probability . As they progress along the road, the probability of generating a new packet (once their queue is cleared) decreases linearly, reaching by the time they arrive at point B. The function governing this evolution is given bywith .

5.3.2. Periodic Traffic Model

6. Mathematical Model Overview

6.1. Notation

- : the number of CAVs with a data packet queued for transmission. This condition occurs when (i) a new packet is generated following a successful transmission1, or (ii) a previous transmission has failed and the same packet must be retransmitted. Conversely, denotes the number of CAVs without a packet in the queue;

- : the number of CAVs attempting to access resources, i.e., vehicles that (i) have a packet in the queue, (ii) are connected to the UAV, (iii) are located within an active beam, and (iv) occupy a segment during a frame k that is activated according to the TDMA procedure outlined in Section 4;

- : the number of CAVs that successfully receive resources to transmit their data;

- : the number of CAVs that did not succeed in receiving resources to transmit their data.

- : probability that a CAV has a packet in the queue, which occurs if (i) a new packet has been generated after a successful transmission (we denote this probability ), or (ii) a previous packet remains in the queue because the last transmission attempt failed;

- : connection probability, that is the probability that a CAV is connected to the UAV, that is it has an SNR above the threshold;

- : activation probability, that is the probability that a CAV is (i) within an active beam and (ii) located in a road segment during a frame k that is active according to the TDMA procedure;

- : blocking probability, that is the probability that a CAV does not have RUs assigned in a given .

6.2. Connection Probability

6.3. Activation Probability

6.4. Blocking Probability

6.5. Target Performance Metrics

6.5.1. Success Probability

6.5.2. Average Success Probability

6.5.3. Average User Throughput

6.5.4. Network Throughput

7. Mathematical Model Under Ideal Conditions

7.1. Probabilistic Traffic Model

7.1.1. Deriving

7.1.2. Deriving

7.2. Periodic Traffic Model

7.2.1. Deriving

7.2.2. Deriving

8. Modeling in Realistic Conditions

- For , the average number of vehicles attempting to access resources, accounting for the queue status, the CAV connection, and both beam and time slot activation, is given bywith . Similarly, .

-

For , we first show the specific cases for and to illustrate the underlying logic, and then generalize the derivation ∀ℓ>1.When , the expression of the average number of CAVs attempting to access resources is given bywith k. Equation (37) is expressed as the sum of two contributions corresponding to distinct scenarios that may occur during the traversal of the preceding beam (): (i) if < and beam 1 is not included in the active set, or if <, then the average number of vehicles attempting to access resources in beam 2 during the kth interval is equal to the average number of vehicles that entering the system with a queued packet and that were not served while traversing beam 1 with probability ; (ii) if beam 1 is active and >, then the vehicles contending for resources in beam 2 are those that, over the intervals , attempted to transmit their UL packets with probability . Similarly, .

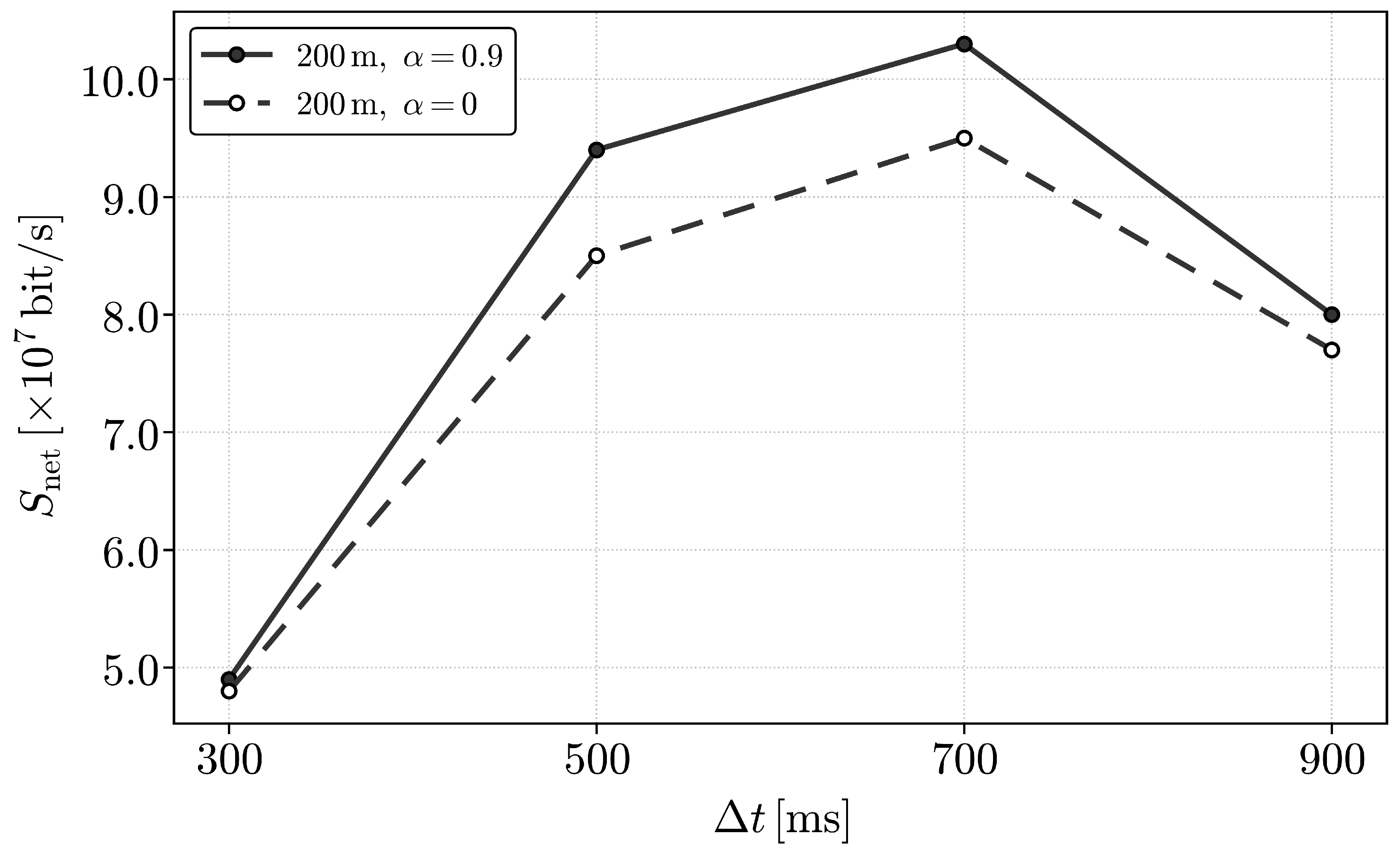

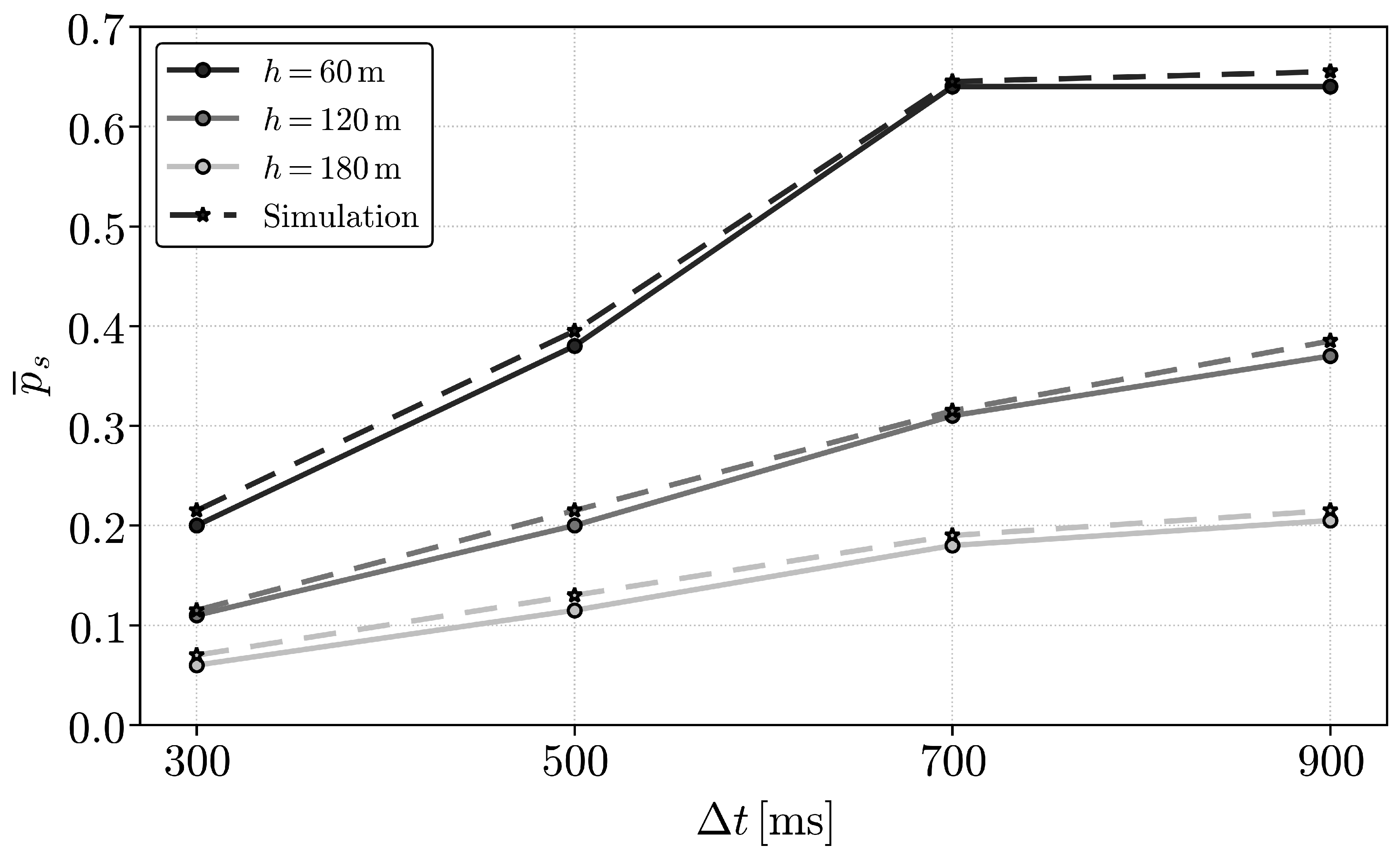

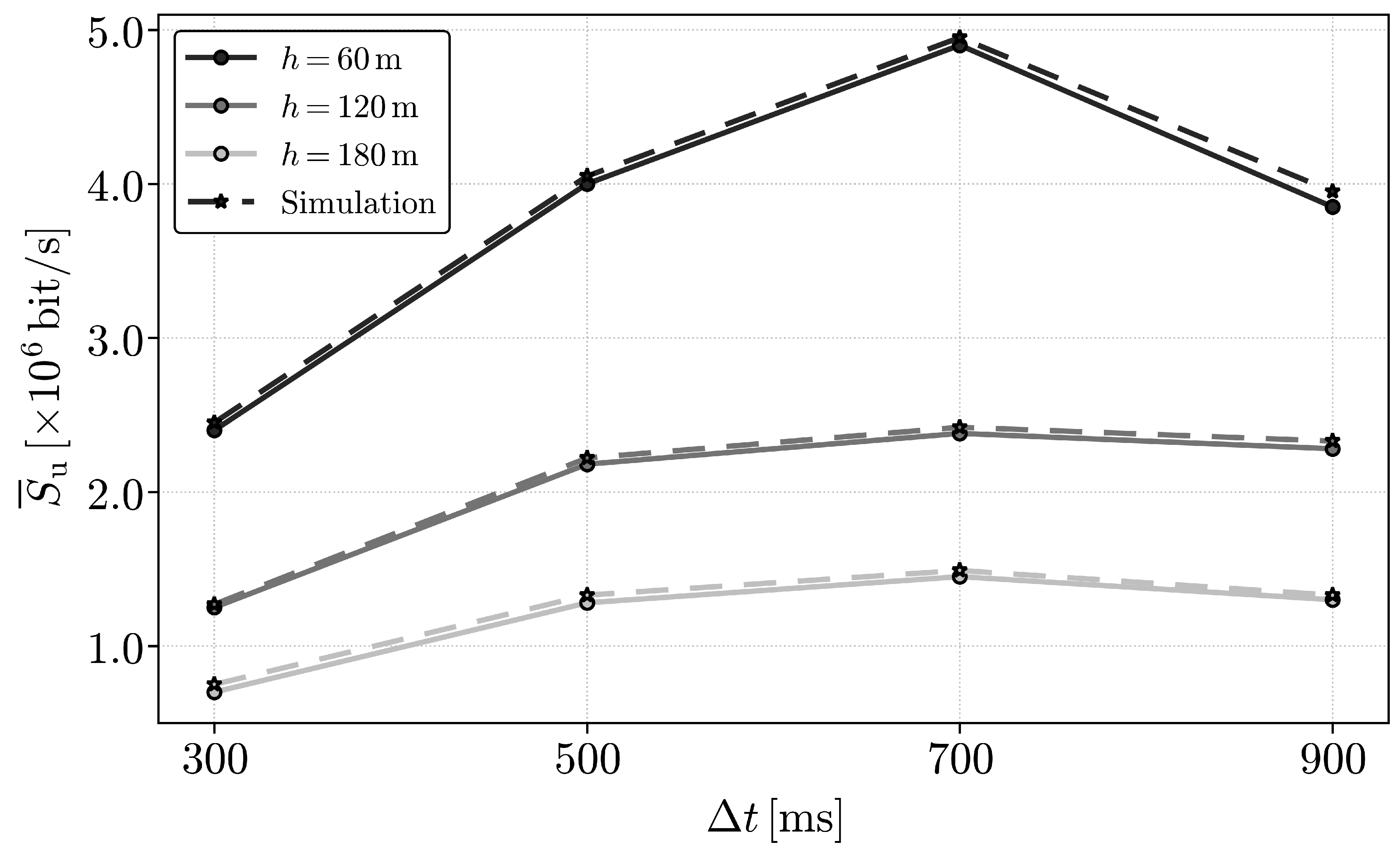

9. Numerical Results

10. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Channel Model and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Appendix B. Heuristic Beam Activation Optimization

Appendix B.1. Analysis of

Appendix B.2. ILP Formulation

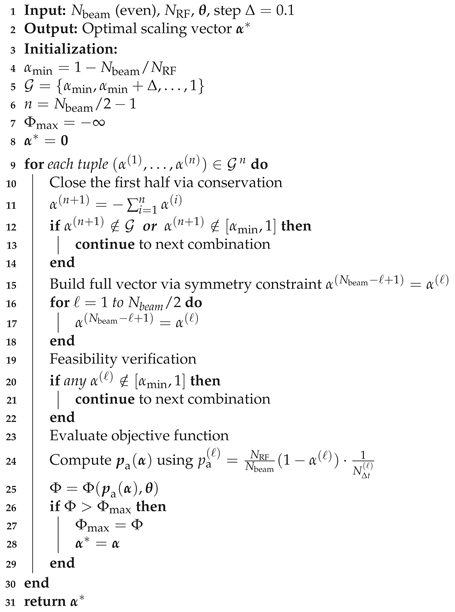

| Algorithm 1: Heuristic Beam Activation Optimization |

|

- 1.

- Exploit symmetry and conservation constraints to reduce the search space from to independent variables.

- 2.

- Enumerate all feasible combinations over a discrete grid for computational tractability.

- 3.

- For each independent variable combination, compute the dependent variable using conservation and reconstruct the full vector via symmetry.

- 4.

- Verify that all computed variables satisfy the bound constraints before evaluation.

- 5.

- Assess the objective function for all feasible configurations and select the optimal solution.

References

- 6G Flagship. 6G Research Verticals, 2024. Accessed on 3 January 2026.

- Liu, J.; Peng, S.; Tong, X. Non-Terrestrial Networks in 6G on Standardization, Key Technologies and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), 2025, pp. 222–226. [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, L.; Ferretti, D.; Buratti, C.; Marini, R. Joint Trajectory Design and Radio Resource Management for UAV-Aided Vehicular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 74, 847–860. [CrossRef]

- Study on New Radio (NR) to Support Non-Terrestrial Networks (Release 15). 3GPP Technical Report TR 38.811 V15.4.0, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), 2020. Available at: https://www.3gpp.org/ftp/Specs/archive/38_series/38.811/38811-f40.zip.

- Dong, K.; Mizmizi, M.; Tagliaferri, D.; Spagnolini, U. Vehicular Blockage Modelling and Performance Analysis for mmWave V2V Communications. In Proceedings of the ICC 2022 - IEEE International Conference on Communications, 2022, pp. 3604–3609. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Su, Z.; Xu, Q.; Ying, B. Edge Computing and UAV Swarm Cooperative Task Offloading in Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), 2022, pp. 955–960. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Du, P.; Gou, H.; Zhang, G. NOMA-MEC Based Task Offloading Algorithm in UAV-Assisted IoV Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Computing, Communication, Perception and Quantum Technology (CCPQT), 2024, pp. 190–194. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, D.; Saber, T. Assessing Potential of UAV-Based Increase in Urban Disasters Communication on Traffic Congestion Mitigation. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster Management (ICT-DM), 2024, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, H.; Huo, J.; Sun, C.; Hao, S.; Zhen, L. Temporal Data Dissemination in UAV-Assisted VANETs Through Time-Varying Graphs. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 14835–14846. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Rothenberg, C.E.; Obraczka, K.; Barakat, C.; Turletti, T. Harnessing UAVs for Fair 5G Bandwidth Allocation in Vehicular Communication via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2021, 18, 4063–4074. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Ghazizadeh, R. Stackelberg Game-Based Deployment Design and Radio Resource Allocation in Coordinated UAVs-Assisted Vehicular Communication Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 1196–1210. [CrossRef]

- Conserva, F.; Verdone, R. Analytical Description of Access Probability and RRA Strategy for UAV-Aided Vehicular Applications. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Micro Aerial Vehicle Networks, Systems, and Applications, New York, NY, USA, 2023; DroNet ’23, p. 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Niu, Y.; Wu, H.; Ai, B.; He, R.; Wang, N.; Chen, S. Joint Optimization of Relay Selection and Transmission Scheduling for UAV-Aided mmWave Vehicular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 6322–6334. [CrossRef]

- Guhagarkar, A.; Sivalingam, T.; Bhatia, V.; Rajatheva, N.; Latva-Aho, M. Reinforcement Learning-Based Optimization of Relay Selection and Transmission Scheduling for UAV-Aided mmWave Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ahmad, A.; Wakeel, A.; Kaleem, Z.; Rashid, B.; Khalid, W. Efficient UAVs Deployment and Resource Allocation in UAV-Relay Assisted Public Safety Networks for Video Transmission. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 4561–4574. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ma, S.; Yang, S.; Zhang, B.; Gao, A. Hierarchical Matching Algorithm for Relay Selection in MEC-Aided Ultra-Dense UAV Networks. Drones 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, G.; Han, G.; Peng, Z. Resource Management with Blockchain for Delay-Sensitive Transmission in UAV-assisted Vehicular Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), 2024, pp. 506–510. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Muhammad, F.; Shafiq, Z.; Irfan, M.; Rahman, S.; Mursal, S.N.F.; Nowakowski, G.; Zharikov, E. Line-of-Sight-Based Coordinated Channel Resource Allocation Management in UAV-Assisted Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 25245–25253. [CrossRef]

- Gai, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Yuan, D. Information Freshness-Oriented Trajectory Planning and Resource Allocation for UAV-assisted Vehicular Networks. China Communications 2023, 20, 244–262. [CrossRef]

- Conserva, F.; Linsalata, F.; Mizmizi, M.; Magarini, M.; Spagnolini, U.; Verdone, R.; Buratti, C. A Thorough Analysis of Radio Resource Assignment for UAV-Enhanced Vehicular Sidelink Communications. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024 - IEEE International Conference on Communications, 2024, pp. 4341–4346. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Du, J.; Zhu, X. Mobility-Aware Task Offloading and Resource Allocation in UAV-Assisted Vehicular Edge Computing Networks. Drones 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yoshii, K.; Shimamoto, S.; Ho, T.D. Optimizing mmWave UAV Networks: Mobility-Aware Deployment and Resource Allocation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 100th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Fall), 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Peer, M.; Bohara, V.A.; Srivastava, A.; Ghatak, G. User Mobility-Aware UAV-BS Placement Update With Optimal Resource Allocation. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2022, 3, 1853–1866. [CrossRef]

- Orikumhi, I.; Bae, J.; Kim, S. Mobility-Aware Resource Allocation in UAV-Assisted ISAC Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), 2023, pp. 1042–1044. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.T.; Nguyen, C.T.; Li, P.; Pham, A.T. Joint Uplink and Downlink Resource Allocation for UAV-enabled MEC Networks under User Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), 2022, pp. 1059–1064. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, D. UAV-Assisted Wireless Networks: Mobility and Service Oriented Power Allocation and Trajectory Design. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 17373–17383. [CrossRef]

- ETSI EN 302 637-2 V1.3.2. Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS); Vehicular Communications; Basic Set of Applications; Part 2: Specification of Cooperative Awareness Basic Service, 2014.

- 3GPP. Enhancement of 3GPP Support for V2X Scenarios; Stage 1 (Release 18). TS 22.186 V18.0.1, 2024.

- Mignardi, S.; Ferretti, D.; Marini, R.; Conserva, F.; Bartoletti, S.; Verdone, R.; Buratti, C. Optimizing Beam Selection and Resource Allocation in UAV-Aided Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), 2022, pp. 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, L.L.; Hanzo, L. DFT-Based Beamforming Weight-Vector Codebook Design for Spatially Correlated Channels in the Unitary Precoding Aided Multiuser Downlink. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Communications, 2010, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Malkawi, W.; Sawalmeh, A.; Almutiry, M.; Alenezi, A. Modeling Ground-to-Air Path Loss for Millimeter Wave UAV Networks, 2021, [arXiv:cs.IT/2101.12024].

- 3GPP. NR; NR and NG-RAN Overall Description; Stage 2 (Release 18). TS 38.300 V18.4.0, 2024.

- Morandi, F.; Linsalata, F.; Brambilla, M.; Mizmizi, M.; Magarini, M.; Spagnolini, U. A Probabilistic Codebook Technique for Fast Initial Access in 6G Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Communication Systems; John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

- Dahlman, E.; Parkvall, S.; Skold, J. 5G NR: The Next Generation Wireless Access Technology, 1st ed.; Academic Press, Inc.: USA, 2018.

- Dong, K.; Mizmizi, M.; Tagliaferri, D.; Spagnolini, U. Vehicular Blockage Modelling and Performance Analysis for mmWave V2V Communications. In Proceedings of the ICC 2022 - IEEE International Conference on Communications, 2022, pp. 3604–3609. [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, S.; Masini, B.M.; Martinez, V.; Sarris, I.; Bazzi, A. Impact of the Generation Interval on the Performance of Sidelink C-V2X Autonomous Mode. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 35121–35135. [CrossRef]

- ETSI. Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS); Vehicular Communications; Basic Set of Applications; Part 2: Specification of Cooperative Awareness Basic Service. Technical Report ETSI EN 302 637-2 V1.4.1, ETSI, 2019. Published April 2019.

- Linsalata, F.; Mura, S.; Mizmizi, M.; Magarini, M.; Wang, P.; Khormuji, M.N.; Perotti, A.; Spagnolini, U. LoS-Map Construction for Proactive Relay of Opportunity Selection in 6G V2X Systems. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 3864–3878. [CrossRef]

- Kleinrock, L. Queueing Systems, Vol. I: Theory; Wiley, New York, 1975.

- Peyhardi, J. On Quasi Polya Thinning Operator. Brazilian Journal of Probability and Statistics 2023. In press, . [CrossRef]

- Mizmizi, M.; Tagliaferri, D.; Badini, D.; Mazzucco, C.; Spagnolini, U. Channel Estimation for 6G V2X Hybrid Systems Using Multi-Vehicular Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 95775–95790. [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Francesca Conserva received the B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in Telecommunications Engineering and the Ph.D. degree in Electronics, Telecommunications, and Information Technologies Engineering from the University of Bologna. Her doctoral research focused on the design of mobility-aware radio resource management algorithms for UAV-aided vehicular networks and on AI-based predictive frameworks for RAN optimization using network KPIs in beyond-5G networks. She is currently a Researcher at WiLab (CNIT), where her research interests include Network Digital Twin technologies, UAV-assisted networks, and AI-driven RAN optimization. |

|

Chiara Buratti received the Ph.D. degree in Electronics, Information Technologies, and Telecommunications Engineering from the University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, in 2009. She is currently an Associate Professor with the University of Bologna. She has coauthored approximately 120 scientific papers. Her research interests include the Internet of Things, with emphasis on MAC and routing protocols, and three-dimensional networks. She was the recipient of the 2012 Intel Early Career Faculty Honor Program Award and the 2010 National GTTI Best Ph.D. Thesis Award. She was the main proponent of the COST Action CA20120 (INTERACT) and is currently its Vice-Chair and Grant Holder. |

| 1 | A unit-size queue is assumed; a new packet is generated only when the queue is empty. |

| Parameter | Notation | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of UAVs | 2 | |

| CAV’s antenna elements | 4 | |

| UAV’s antenna elements | 5 | |

| CAV’s transmitting power | 23 dBm | |

| CAV’s speed | v | 33.3 m/s |

| Vehicle’s average length | 5 m | |

| Noise power | -101 dBm | |

| Excess path loss offset | A | 84.64 dB |

| Path loss exponent | 1.55 | |

| Log-normal shadowing variance | 4 | |

| Vehicle density | 80 cars/km | |

| SNR threshold | 13 dB | |

| Carrier frequency | 28 GHz | |

| Bandwidth available per beam | B | 30 MHz |

| PRBs per channel | 10 | |

| Subcarriers per channel | 12 | |

| Subcarrier spacing | 120 KHz | |

| Demand | D | 10 Mbit |

| Slot duration | 125 s | |

| Max. packet generation probability | 0.9 | |

| Min. packet generation probability | 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).