1. Introduction

Albania has seen very rapid development along the coast during the last ten years due to improved infrastructure, increased tourism arrivals, and international recognition (INSTAT, 2023; UNWTO and AIDA, 2024). As Albania is transforming, Vlora has also emerged among the most dynamic markets for properties within the country, given the demand from a diverse mix of locals, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo and European visitors (Housing Europe Observatory, 2025; UN-Habitat, 2024).

On the other hand, the prospect of accession to the European Union (EU) has also reinforced the expectation of institutional and economic stability and hence property value growth (European Commission, 2024; World Bank, 2023). This higher expectation has affected the increase of the demand pressure, especially in coastal real estate markets, indirectly contributing to higher affordability constraints for the locals and raising questions about the ongoing dynamics of speculation (Housing Europe Observatory, 2023; Bellona EU, 2024). Literature already explores tourist-related housing pressures (Gurran et al., 2017), cycles of speculation related to transition economies (Hirt et al., 2007), and macroeconomic consequences related to EU enlargement (Čulig, 2011). Nevertheless, there is a lack of focus on individual psychology processes underlying real estate choices related to EU accession expectations. Due to real estate markets’ main features (illiquidity, information asymmetries, and long investment horizons), we note a presence of heuristic-driven judgment under uncertainty in these market typology (Case & Shiller, 2003; Glaeser & Nathanson, 2017).

Behavioral finance research confirms that in real estate markets, investors use cognitive and social heuristics such as anchoring, overconfidence, and herding (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Barberis & Thaler, 2003), thus, potentially intensifying the demand and as a consequence, putting higher price pressures especially in the emerging markets.

In the wake of growing pressures regarding affordability, mounting speculative interest, and a growing sense of fatigue over EU enlargement timetables, it is timely and relevant to explore the implications of EU-accession optimism and investment behavior in real estate. The EU-accession optimism mechanism is a sentiment-driven process that serves as a stimulus for EU-accession investment behavior.

This research applies Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling to analyze the effects of optimism, anchoring, overconfidence, herding, and investment intention in a real estate environment that has experienced swift development and changes in institutional settings. The research applies a survey conducted in Vlora, in Albania, of the opinions of 462 individuals including local residents, Albanian diaspora communities, Albanians of Kosovo and visitors from Europe. We approach expectation formation instead of outcomes in transactions.

1.1. Research Gap

Despite a lot of research on housing cycles, tourism-induced urban change, and EU enlargement, there are quite important research gaps. First, existing research normally analyzes either tourist development and accession to the EU as two conventional macroeconomic factors, neglecting their combination being adopted and channeled into a decision-making process on the basis of heuristics. Second, applications of behavioral theories related to real estate investment in candidate countries of the EU are rather scarce and opposed to a great background of uncertainty and asymmetric information of this kind of environment. Third, existing studies rarely compare local and non-local investor groups, despite their diverse sets of information backgrounds, emotional connection, and reference frames.

A definition of the EU accession process as an exogenous macroeconomic factor is the prevalent approach within the discipline of real estate. A rapidly growing coastal market like Vlora offers an opportune environment to examine this shortcoming given the associated exposure to tourism and heterogeneity of demand coupled with high convergence expectations.

We believe this is the first study that models the sentiment of EU accessions as a behavioral driver rather than using it as an external macroeconomic control on property investment decisions.

1.2. Study Objective and Contribution

This research proposes and verifies a behaviorally driven finance model in which optimism about EU access has a role as a sentiment factor influencing anchoring, overconfidence, and herding on real estate investment choices. Our research uses data acquired from 462 respondents for four groups of investors. To analyze the model, we employed the PLS SEM technique.

This research adds the following to the existing knowledge:

Demonstrating the significance of EU-accession expectations, usually examined at the macro-level, to micro-level financial valuations and investment decisions;

Analyzing quantitatively the importance of anchoring, overconfidence, and herding in a real asset-setting.

Documenting systematic behavioral heterogeneity among local residents, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo, and European visitors.

This work helps develop an understanding of the role of sentiment and the use of heuristics in real estate activities in candidate countries in the EU.

1.3. Theoretic Contribution

This paper contributes to behavioral finance in four dimensions. First, it extends behavioral theory to real assets by demonstrating that anchoring, overconfidence, and herding significantly impact valuation and investment intentions in coastal housing markets, which are subject to information frictions. Second, it embeds macro-level political narratives- EU-accession expectations- into micro-level behavioral mechanisms and demonstrates the ways in which institutional optimism serves as a heuristic trigger. Third, it conceptualizes behavioral heterogeneity across groups, and it shows that locals, diaspora members, Kosovo Albanians, and European visitors display distinct bias intensities that are related to informational proximity and emotional attachment. Fourth, it provides a novel empirical setting with Vlora, where convergence narratives, uncertainty, and rapid development come together to produce sentiment-driven investment behavior.

These contributions together help increase the understanding of how macro narratives and micro-level heuristics jointly shape decision-making in emerging real estate markets.

2. Literature Review/Research Background

2.1. Behavioral Finance Foundations

Behavioral finance contests the ideas of perfectly rational investors by evidence indicating that people make use of heuristics to create biased judgments (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Barberis & Thaler, 2003). Real estate markets, due to their infrequency of trade, illiquidity, and non-transparency, make them even more susceptible to these errors (Case & Shiller, 2003). Consequently, anchoring, overconfidence, herding, and extrapolative forecasts have been found to have a big role in these markets (Glaeser & Nathanson, 2017; Barberis et al., 2018).

2.2. Key Behavioral Biases in Real Estate Decision-Making

Anchoring

Real estate investors often make use of external reference prices, such as those in Greece or Croatia, in the assessment of properties within the Vlora region, resulting in the impression of undervaluation (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974; Case & Shiller, 2003). In the emerging and EU candidate countries, the lack of transparency as well as the dispersal of data within the markets increase the problem of anchoring, as investors rely on more readily recognizable external benchmarks.

Confidence.

Overconfident investors place too much emphasis on the accuracy of predicting price movements or the timing of accession into the EU, and place too little emphasis on the potential risks of unfavorable outcomes. Overconfidence can create an exaggerated degree of confidence, hasten the speed of decision-making, and increase the tendency to invest when faced with uncertainty (Glaser & Weber, 2007).

Herding

Herding occurs when investors follow others’ actions rather than their own independent analysis. In the Vlora case, the diaspora communities, the observed constructing activities, and peer transactions are considered distinct and obvious social signals that reinforce collective enthusiasm and can possibly drive speculative processes (Banerjee, 1992; Shiller, 2014).

Confirmation Bias and Extrapolation.

They selectively process information to verify their beliefs of high returns, and they extrapolate the current price advances in the future as well. This enhances the robustness of the investment decisions made on the basis of expectations in rapidly growing real estate markets, as mentioned in Shiller (2014) as well as Glaeser & Nathanson (2017).

While confirmation bias and extrapolation are very relevant behavioral aspects of real estate markets, they are not explicitly conceptualized in this paper in order to maintain simplicity and avoid conceptual redundancy between optimism and formalized price expectations.

2.3. Sentiment, Expectations, and Real Estate in Emerging and EU-Candidate Markets

The real estate markets in the emerging and candidate economies are influenced by the expectations of institutional convergence, economic upgrading, and price capitalization (IMF, 2022; EBRD, 2015; European Commission, 2024). Findings within Croatia, Bulgaria, and Romania illustrate that the expected accession to the EU may trigger the inflow of speculations even prior to economic upgrading (Čulig, 2011; Hirt et al., 2007). Very few studies focus on the micro-level behavioral-based mechanisms to channel the story into investment choices.

The optimism of EU-accession can trigger anchoring, overconfidence, and herding with respect to stability, investment, and price. However, despite the relevance, no literature has examined these processes in emerging markets in coastal regions. This paper closes these research gaps by unifying the theories of sentiment, heuristics, and cross-group heterogeneity in order to discuss these processes within the Vlora property market.

3. Behavioral Finance Framework and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Behavioral Finance Framework

The empirical model identifies optimism about the EU as the focal exogenous sentiment metric. The above metric is modelled as a latent construct that represents investors’ expectations with respect to Albania's likely accession to the EU and overall economic development. Consistent with the theoretical premises of behavioral finance, the above optimism is postulated to influence real estate investment both directly and through a set of cognitive and social heuristics (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Barberis & Thaler, 2003).

While Harman’s single-factor test indicates that common method bias does not present a serious threat to the current investigation, future studies may further enhance the strength of their casual claims and findings by using survey and financial data related to the real estate market.

In the validated model, optimism affects price expectations directly, capturing the process of EU-accession stories driving higher perceived future property values.

Optimism also affects investment intention through its direct influence on purchase intention, speed of decision, and perceived market attractiveness.

Moreover, optimistic affect affects investment intention through the anchoring mechanism as a mediator and overconfidence and herding as moderators.

Below are the descriptions of the aforementioned mechanisms as specified and tested for in the empirical model.

3.1.1. Anchoring (Mediator)

Anchoring is posited as a mediator between optimism and investment intention. Greater optimism about the EU is modelled as strengthening the tendency to compare Vlora properties on the basis of reference points established through the.price levels of Greece, Croatia, Italy, and Western Europe.

"Discount" is generated through these reference points and this enhances WP and investment intention. In the structural model, this is represented through the paths optimism → anchoring → investment intention, where anchoring conveys the influence of optimism on investment decisions.

3.1.2. Overconfidence (Moderator)

Overconfidence is defined as a moderator on the relationship between optimism and investment intention. Overconfident investors who are optimistic in their beliefs feel they know more about the future of the markets or the timing of EU accession than other people.

Consequently, they tend to underestimate risk, overestimate their forecasting accuracy, and translate optimism into fast and intense investment desires. Empirical evidence uses an interaction between optimism and overconfidence, whereby the optimistic-effect on investment intention is stronger for those with higher overconfidence levels.

3.1.3. Herding (Moderator)

Additionally, herding is considered to moderate the optimism–investment relationship. For investors who are highly sensitive to social information, such as disapora advice and observable construction fervors, optimistic stories about joining the EU would be easily translated into tangible investment choices. In the empirical analysis, herding is interacted with optimism, such that optimism has a greater influence on investment intentions among those with higher levels of herding behavior.

"Price expectations" capture the respondents' beliefs about the future course of property prices in Vlora. While EU-related optimism is related to a more general sentiment about institutional catching-up and economic prospects, "price expectations" focus on a more specific belief about the future value of real estate.

In line with the views implicit in the extrapolative-expectations approaches, it can be hypothesized that the more optimistic individuals, the more their expectations of asset price growth strengthen. Following this, the structural model demonstrates that the direct relationship holds from the EU-related optimism to the expectation of asset price growth.

Being an overlapping result of optimism, price expectations are not modeled as mediators, since the overall aim of the research is not focused on studying the process of forming expectations but rather analyzing the formation of expectations per se. Adding feedback loops between price expectations and investment intention would enhance endogeneity. Furthermore, this would add complexity without adding explanatory power within the context of the analysis. Rather, price expectations can be seen as an additional result of sentiment, like investment intention.

3.1.4. Conceptual Logic of the Empirical Model

The framework of behavioral finance, as applied to the PLS-SEM analysis, is organized as shown below:

Optimism, better known as the sentiment factor, can be defined as the exogenous latent

Price Expectations and Investment Intentions are endogenous constructs of the PO outcomes. Optimism affects both of them directly (H1–H2).

The mediating role of anchoring between optimism and investment intention (H3) is supported by the sequence: Optimism → Anchoring → Investment Intentions.

Overconfidence and Herding significantly interact with the relationship between investment and optimism to predict investment intention as proposed in H4 and H5.

Multi-group analysis (MGA) evaluates the relative strength of these paths for locals, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo, and Europeans (H6).

3.2. Hypothesis Development

Based on the framework developed in behavioral finance and existing literature on sentiment, heuristics, and real estate decision-making, several hypotheses are developed for empirical analysis as follows:

H1: EU-accession optimism positively influences price expectations

Greater optimism about the prospective accession of Albania into the EU would lead to a positive impact on the expected property price in Vlora.

H2 : Optimism about EU accession has a positive effect on investment intention.

Greater optimism regarding accession can thus be projected to enhance the willingness to buy property and perceived market attractiveness.

H3 : Anchoring mediates the relation between optimism and investment intention.

Optimism will lead to increased usage of external reference prices (Greece, Croatia, Italy), which will further result in higher investment intentions since there will be a “discount” on Vlora property values.

H4 : Overconfidence amplifies (moderates) the relationship between optimism and investment intention.

The influence of optimism on investment intention is then hypothesized to be more pronounced among the overconfident respondents, who tends to overestimate their capacity to forecast developments vis-à-vis the EU.

H5 : Herding amplifies (moderates) the relationship between optimism and investment intention.

The positive effect of optimism in investment intentions is expected to be reinforced in those respondents who display high levels of herding behavior.

H6 : Behavioral pathways vary widely among investor groups.

The linkages amongst optimism, anchoring, overconfidence, herding, investment expectations, and investment intentions are anticipated to differ amongst local residents, Albanian diaspora, Albanians of Kosovo and European visitors, because of variations in informational proximity, emotional attachment, and reference market exposure.

3.3. Behavioral Model Specification

The behavioral model tested puts EU-related optimism as the main exogenous sentiment construct in real estate investment decision-making. We assume that optimism shapes investment behavior directly as well as indirectly by activating key cognitive and social heuristics.

Optimism directly influences price expectations, reflecting how sentiment related to EU accession is conveyed as higher perceived future property values. Optimism as well, has a direct effect on investment intention, which reflects how investment sentiment influences perceived increases. Finally, anchoring functions as a mediator, transferring a part of th effect of optimism towards investment intention.

Besides, the impact of optimism on investment intention is conditionally strengthened by overconfidence and herding. These behavioral biases act as moderating mechanisms that amplify sentiment-driven investment behavior. The final endogenous outcome of the model, is represented by investment intention.

This proposed behavioral framework is examined empirically using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). This enables the simultaneous estimation of direct, mediating, and moderating effects. In addition, we use multi-group analysis (MGA) to assess whether the strength of these behavioral relationships varies across local residents, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo, and European visitors.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

The survey design was done in such a way that it allows to collect psychological perceptions, market expectations, and investment choices in a single-point measurement. The design that fits this research, which has to do with market expectation rather than market performance, is cross-sectional. It is appropriate to note that cross-sectional samples are generally considered appropriate in studies in the field of behavioral finance, especially when dealing with issues of sentiment, heuristics, and market expectations. Such samples fit perfectly in an environment where investment choices depend more on future rather than ex post performances.

4.2. Sampling and Participants

A purposive, non-probability sampling method was employed to select participants who were actively engaged or had exposure to the coastal real estate market within Vlora. The final result is that the overall dataset contains 462 valid participants who belong to four different investor groups based on their investment behavior:

Local Residents

Diaspora Albanians

Albanians of Kosovo

European Visitors

These groups are chosen based on systematic variability in their informational proximity, emotional closeness to Albania, use of reference pricing, and knowledge of the market. Variability in these is crucial in examining the behavioral dispersion and testing Hypothesis 6.

All participants were required to be at least 18 years of age and to either own/ recently have bought, or be considering to invest in real estate within the coastal area of Vlora region.

Timing of sampling and external validity

Data collection occurred during the period when non-local investor groups, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo, as well as European visitors, are mostly present in Vlora (May 1- September 30). This contributes to improving both the external validity of the study, as the responses given capture natural market exposure, rather than being conditioned by an artificially created context, as well as the internal validity. For the rest of the study, the participants mainly came from local residents.

The period chosen corresponds to the peak arrival of foreign visitors, during which both first-time and returning visitors become familiar with Vlora and start to actively explore real estate investment opportunities through property agencies and direct interactions with local residents. These periods are ideal for capturing investment intentions and not evaluation perceptions.

4.3. Data Collection Procedure

The survey was carried out from May to September 2025, capturing genuine investor behaviour during the peak of tourism and of the property search period. The study used distribution channels such as real estate agencies, the promenade at the town waterfront, tourist sites, social groups in the diaspora, and real estate forums.

The survey was answered voluntarily and anonymously. The respondents consented and stated that this research adhered to the standard for academic research as well as data protection. Prior to analysis, the responses were checked for consistency and integrity.

4.4. Measures and Instrumentation

All the constructs were measured using multi-item Likert scaling adapted from established behavioral finance and real estate psychology studies. The constructs measured were:

EU accession expectations and optimism driven by expectations (sentiment)

Anchoring bias (mediator)

Overconfidence (moderator)

Herding (moderator)

Investment intention and willingness to pay (outcome variable

Control variables

To make the discussion of psychological implications more concrete, this study tested a series of variables related to demographics (age, gender, education level, and income), financial literacy, risk tolerance levels, as well as familiarity with the Vlora real estate market. Risk tolerance levels and market familiarity are presented descriptively to address individual group behavioral variation but are excluded from being a PLS-SEM construct since this study is specifically interested in distilling pure behavioral processes derived from real market sentiment rather than clouding models with overlapping constructs related to psychology studied herein.

Internal consistency, construct validity, and discriminant validity were evaluated as a precursor to hypothesis testing on common behavioral finance validation rules.

4.5. Data Analysis Strategy

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 29 and SmartPLS 4, following a structured sequence:

Cleaning and descriptive statistics;

Analysis of measurement reliability and validity, Cronbach’s alpha value (α ≥ 0.70), composite reliability value (CR ≥ 0.70), Average Variance Extracted value (AVE ≥ 0.50), and HTMT value < 0.85;

Estimation of direct effects (H1-H2);

Mediation analysis of anchoring bias (H3);

Moderation analysis for overconfidence and herding (H4-H5);

Multi-group analysis (MGA) across investor segments (H6)

PLS-SEM offers specific advantages to the present investigation, namely its predictive focus, flexibility to deal with interaction terms, and robustness to non-normal data, which are frequently encountered problems when dealing with survey data describing behavioral phenomena. Primarily, the point here is to explain the variation in the investment intention, rather than to achieve the optimal fit to the data. Furthermore, the present investigation takes advantage of the multi-group analysis facilitated by the use of PLS, namely the direct analysis of both mediating and moderating influences.

Boot-strapping using 5,000 resampling was used to check the significance of the paths and robustness of the models. Variance inflation factors (VIF < 3.3) also ensured there were no multicollinearity problems. Checking for potential common method variance, the single-factor test proposed by Harman was used. Analysis of the unrotated solution revealed that no single factor explained more than 40% of the total variance, implying that this form of bias is unlikely to emerge and affect the findings.

The expectations for prices are modeled as a parallel process with EU-related optimism, as it would not make sense to model expectations as a mediating variable because this would make the expectations a middle variable and, as said, add more complexity to this model. The intentions for investment would be more than sufficiently explained as a proposed behavioral context.

As predicted by the theory of behavioral finance, sentiment is modelled as a cognitive-affective antecedent of investment intention. As such, any optimism concerning the EU is considered to be an exogenous determinant of investment decision, as opposed to an inverse consequence of investment intention.

4.6. Pilot Testing

Before its widespread use in data-gathering, the instrument was pilot-tested on 30 respondents from all four types of investors. Some changes were introduced in terms of clarity, wording, and minimizing misunderstandings. Internal reliability in pilot testing showed satisfying results in terms of data consistency as denoted by Cronbach’s Alpha values higher than 0.70.

4.7. Ethical Considerations

It followed the ethical guidelines provided by the University of Vlora as well as EU’s GDPR guidelines. It was an anonymous process, and consent was asked from all respondents. Moreover, the data was encrypted for research purposes only.

4.8. Robustness Checks

Several robustness checks were performed in order to evaluate the sensitivity and reliability of the structural model relationships. Firstly, multicollinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factors, which all proved to be less than the suggested value (VIF < 3.3). Secondly, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was used for evaluating overall model stability, and it was successfully supported by consistent standard error and significance tests for all significant primary paths in the structural model. Moreover, alternative model specifications were tested for robustness by including control variables; and there was no impact on the significance and direction of all significant primary paths among KSAs and HR outcomes. Lastly, global model fit criteria were inspected as SRMR < 0.08 and NFI > 0.90.

All these validation tests demonstrate that the results are robust and that the proposed framework is valid.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Results and Behavioral Constructs

Table 1 shows the average score of the constructs for the four groups of respondents: European visitors, diaspora Albanians, Albanians of Kosovo, and locals, measured through 1-7 scales, where higher scores indicate more agreement or higher levels of behavior.

Decision speed is also described descriptively as an ancillary behavioral measure and is not analyzed structurally, as the research focuses more on the formation of investment intent as opposed to the timing thereof. Moreover, risk tolerance and market familiarity are also described as descriptive control variables to provide perspective on the divergent behaviors between different groups of investors.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents (N = 462).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents (N = 462).

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Age |

18–29 |

108 |

23.4% |

| |

30–44 |

182 |

39.4% |

| |

45–59 |

124 |

26.8% |

| |

60+ |

48 |

10.4% |

| Gender |

Female |

214 |

46.3% |

| |

Male |

248 |

53.7% |

| Education Level |

Secondary |

92 |

19.9% |

| |

Bachelor’s |

198 |

42.9% |

| |

Master’s |

128 |

27.7% |

| |

Doctorate |

44 |

9.5% |

| Monthly Income (Self-Reported) |

< €1,000 |

102 |

22.1% |

| |

€1,000–€2,000 |

168 |

36.4% |

| |

€2,001–€3,500 |

124 |

26.8% |

| |

> €3,500 |

68 |

14.7% |

| Property Ownership Status |

Owns property in Albania |

196 |

42.4% |

| |

Has purchased property in Vlora in last 5 years |

82 |

17.7% |

| |

Actively considering buying |

184 |

39.8% |

| Market Familiarity |

Low familiarity |

172 |

37.2% |

| |

Moderate familiarity |

156 |

33.8% |

| |

High familiarity |

134 |

29.0% |

| Investor Group |

Local residents |

115 |

24.9% |

| |

Diaspora Albanians |

132 |

28.6% |

| |

Albanians of Kosovo |

128 |

27.7% |

| |

European visitors |

87 |

18.8% |

Descriptive outcomes indicate strong variations in behavior and attitudes among different investor groups. Anchoring effects are evident among diaspora Albanians and European visitors; these are influenced by common usage of external price comparisons from higher-priced European properties. Overall, investment intention corresponds to levels of EU-related optimism; however, diaspora Albanians record the strongest intent levels, suggesting that stronger economic abilities help drive optimisms into concrete investment choices. Kosovo Albanians record high levels of investment intention, although these are slightly lower than in diaspora Albanians, suggesting that stronger optimisms are underpinned by stronger budget limitations. European visitors record high levels of investment intention due to comparative price perception; however, low market familiarity moderates immediacy. Speed in decision-making stands higher among diaspora participants than European visitors and Kosovo Albanians; however, local residents always record the lowest decision speed due to budget limitations and stronger familiarity with local conditions.

Taken together, these descriptive findings suggest systematically more pronounced sentiment and heuristic-related characteristics among non-local investors relative to local residents. European visitors show a remarkably low degree of market familiarity, measured at 1.0, which denotes a lack of understanding regarding local prices, regulations, and unwritten rules. Their investment interest is thus more influenced by reference prices from outside than by local market knowledge.

Contextual Interpretation of Group Differences

The Albanian coastal property market can be seen as an arena where various groups of investors interact and influence the market in ways that are meaningful and, in part, similar. Domestic Albanians are also not a uniform group, and although many have limited budgets and are therefore constrained in their participation in the market as it grows in price, the more capital-intensive group is still active and opportunistic at times.

Albanian investors in Kosovo are geographically and culturally close to Albania and are often influenced by Albanian media and tourism packages, reflecting high awareness and high investment readiness based on emotional and patriotic drivers despite variability in economic capability. Diaspora groups have even higher non-economic drivers influenced by factors of nostalgia, physical remove from local constraints on a day-by-day basis, and familiarity with more formalized European investment sectors, leading to a strategic view of Albanian property holdings and high belief in transferability of knowledge.

European visitors are also diverse in their approach to Albanian property, where many of them resort to the approach of comparative valuation and convergence theory in carrying out their valuation of local prices, challenged by information distance for local rules and local habits. The promotion of Albanian tourism, combined with the worldwide travel agencies, further complicates this issue by considering it a new, yet to be explored destination in the long run.

Interacting forces like these help maintain housing demand along various channels of affordability, emotional influences, and optimal expectations, leading to pressures on housing prices despite local fundamentals suggesting corrections based on incomes.

5.2. Composite Behavioral Indices

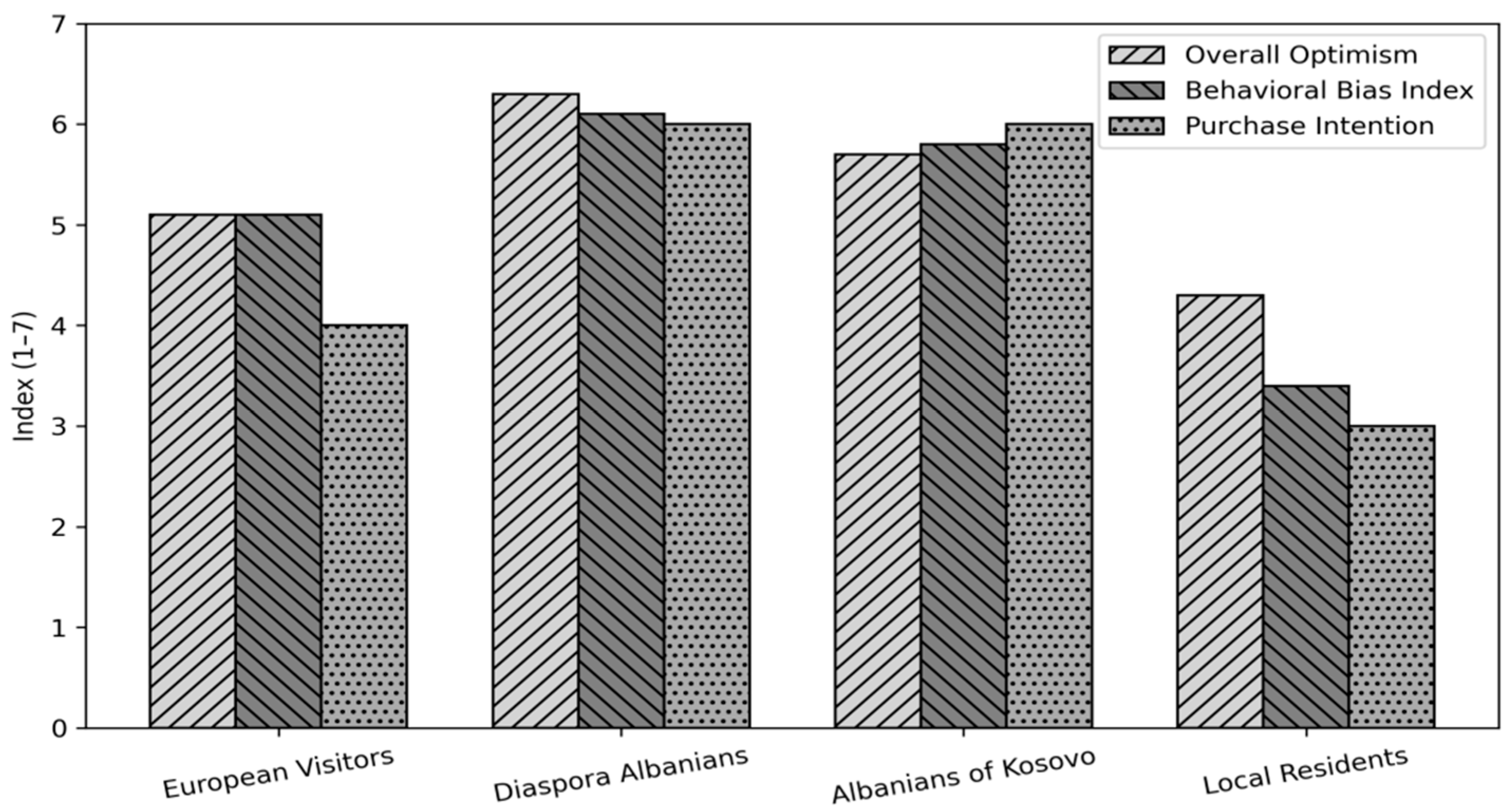

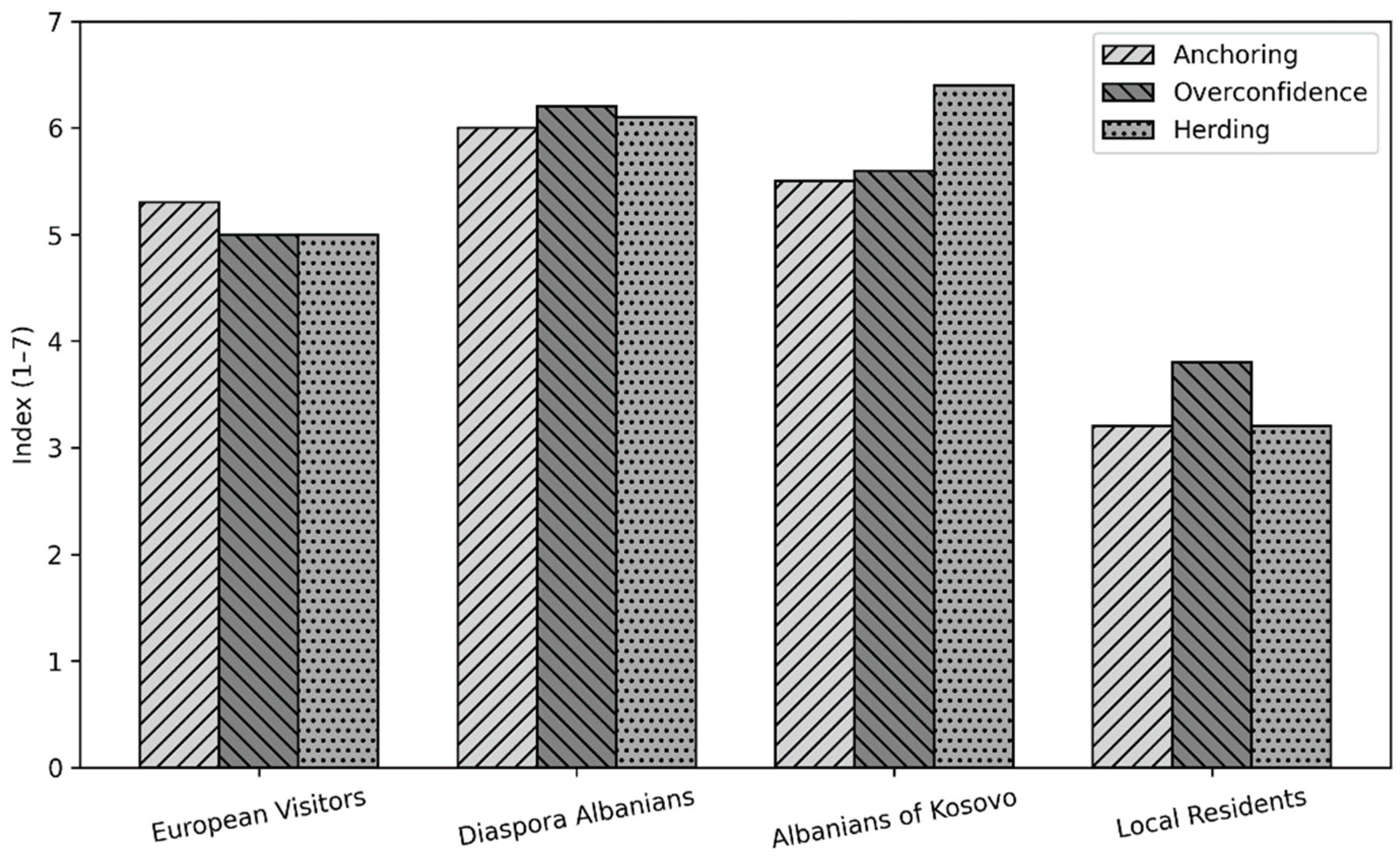

We, therefore, constructed two composite indices to capture the wider patterns of sentiment and behavioral bias across the groups of investors. The Optimism Index incorporates EU-related expectations, while the Behavioral Bias Index sums up anchoring, overconfidence, and herding traits.

Optimism Index (EU-related expectations): Diaspora 6.3 > Kosovo Albanians 5.7 > European visitors 5.1 > Locals 4.3

Behavioural Bias Index = Anchoring + Overconfidence + Herding: Diaspora overseas 6.1 > Kosovo Albanians 5.8 > European visitors 5.1 > Locals 3.4

Interpretation.

Non-resident respondents-especially diaspora and Kosovo Albanians-report systematically higher optimism and stronger reliance on behavioral biases compared to local residents. This pattern reflects the differences in informational distance, emotional attachment, and exposure to external reference narratives and is in line with the hypothesis that sentiment-driven mechanisms disproportionately shape non-local real estate investment behavior.

5.3. Hypothesis Testing Summary

The results strongly support the theoretical framework of behavioral finance. All six hypotheses have been confirmed. EU-related optimism significantly enhances both price expectation and investment intention (H1–H2). Anchoring partially mediates the effect of optimism on investment intention (H3), while overconfidence and herding significantly strengthen such a relationship through moderation (H4–H5). Multi-group analysis further points out statistically significant differences in behavioral pathways across investor categories (H6).

5.4. Significance of the Structural Model and the Path Coefficients

Structural equation modeling by means of SmartPLS 4 confirms the robustness of the estimated behavioral model. Standardized path coefficients reveal the existence of statistically significant relationships among latent constructs, in full support of the hypothesized structural framework.

Key standardized effects are summarized below.

Optimism → Investment Intention: EU-related optimism exerts a positive and statistically significant effect on investment intention, β = 0.42, p < 0.001. This means that stronger convergence-related sentiment is associated with a higher willingness to invest in the Vlora real estate market.

Optimism → Price expectations: Optimism also significantly positively influences price expectations, with β = 0.37, p < 0.01, which would confirm that narratives about EU accession translate into higher anticipated future property values.

Overconfidence (moderation): The interaction of optimism and overconfidence is positive and statistically significant: β = 0.28, p < 0.05. This suggests that the effect of optimism on investment intention is stronger for those respondents who are overconfident.

Herding (moderation): The interaction term of optimism and herding is positive and significant as well (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), which implies that social influence mechanisms amplify investment behavior driven by optimism.

Bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples confirms that all estimated paths are stable. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF < 3.3) show that the structural model does not present multicollinearity issues.

5.5. Hypothesis Testing Results

Table 3.

Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing.

Table 3.

Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing.

| Hypothesis |

Relationship Tested |

β-Coefficient |

t-Statistic |

p-Value |

Result |

| H1 |

Optimism → Price Expectations |

0.37 |

3.45 |

0.001 |

Supported |

| H2 |

Optimism → Investment Intention |

0.42 |

4.12 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| H3 |

Anchoring (Mediation) |

0.31 |

2.80 |

0.005 |

Supported |

| H4 |

Overconfidence (Moderation) |

0.28 |

2.25 |

0.024 |

Supported |

| H5 |

Herding (Moderation) |

0.33 |

2.60 |

0.009 |

Supported |

| H6 |

Group Differences (MGA) |

— |

— |

— |

Supported |

5.6. Summary of Figures

The foolowing figures and table summarize the empirical findings:

Figure 2 shows distinct group-level patterns in optimism and behavioral biases. The diaspora and Kosovo Albanian respondents exhibit the highest levels of EU-related optimism and bias intensity, while European visitors show pronounced anchoring but more moderate overconfidence. The local residents consistently score the lowest in all dimensions and show continuous exposure to the local market constraints.

Figure 3 below shows that there is a pronounced and consistent gradient across investor groups, such that the higher the level of optimism, the greater the intensity of behavioral bias and subsequently the stronger purchase intentions. Diaspora and Kosovo Albanian respondents cluster at the upper end of all three indices, with European visitors occupying an intermediate position and local residents consistently scoring the lowest. This visually confirms the results of the structural model, which identified that non-local investor behavior is disproportionately influenced by sentiment-driven mechanisms.

As

Table 4 shows, optimism about EU accession enhances both price expectations and investment intention, whereas the relationship is mediated by anchoring, and overconfidence and herding strengthen (moderate) the optimism–investment link.

6. Discussion

This research shows that Albania's prospect of joining the EU is an effective macro-level story that investors absorb and process in terms of sentiment rather than reflected in economic fundamentals. The impact of this sentiment is manifested in real estate investment choices via specific behavioral processes.

These results show that EU accession optimism is a primary expectation-forming rather than an expectation-confirmation process. Expectation formers do not base their responses on actual current income growth or market fundamentals but construct convergence stories to conform to future prices and market appeal. This is consistent with models of extrapolation of expectations in behavioral finance theories where beliefs of future change influence forward-looking beliefs rather than current fundamental data (Barberis & Thaler, 2003; Greenwood & Shleifer, 2014).

Although European visitors and Kosovo Albanians display comparable levels of investment intention and decision speed, the underlying behavioral mechanisms differ substantially. European visitors are primarily driven by strong anchoring and comparative price valuation, whereas Kosovo Albanians’ investment behavior is more strongly shaped by herding effects and social influence. This distinction highlights that similar investment outcomes may arise from fundamentally different behavioral pathways.

In the view of narrative economics, political and institutional narratives like the prospect of accession to the EU can be considered as contagious narratives which coordinate beliefs of different market participants (Shiller, 2014). In particular, in the real estate market where illiquidity, information asymmetry, and transparency are less observable, narratives can play a significant role in affecting perceived payoffs and quasi-legitimating positive expectations.

Anchoring appears as an essential behavioral channel through which attitudes about market sentiment are converted into judgments on valuation. Indeed, investors often compare property prices in Vlora in relation to benchmark levels within the Mediterranean region, specifically Greece and Croatia. Cross-market comparisons engender the view of a "discount" on market valuation, elevating the readiness-to-pay index even beyond the fundamentals in Albania. Rather than being recourse-driven, this external form of anchoring is activated on the expectation front rather than objective fundamentals, thereby introducing reference-driven theories within a convergence-oriented market environment.

The exaggeration of optimism via overconfidence and herding is further exemplary in the translation of sentiment to more extreme and rapid investment choices. Overconfidence diminishes risk perceptions and enhances investment speed, as more optimistic market participants hasten investment choices without considering the opposing possibilities (Glaser & Weber, 2007). Herding, in contrast, translates individual sentiment via social processes such as diaspora networks and construction projects, and these social processes promote imitation and collective optimism (Banerjee, 1992; Shiller, 2014).

Behavioral responses also differ between investor cohorts. Non- locals/ foreigners, (diaspora Albanians, Kosovo Albanians, and European visitors), demonstrate higher optimism, reference price expectations, and herding behavior compared with locals. A lack of informational overlap with local constraints, coupled with emotional ties and exposure to foreign market references, enhances vulnerability to sentiment-driven choices. Locals, on the other hand, show more prudent behavior, implying a greater degree of coordination with income constraints, housing affordability, and market realities.

These trends collectively can be viewed as evidencing early-stage speculative trends where demands are maintained by optimism and social contagion despite a lack of corresponding development in fundamentals (Kindleberger & Aliber, 2011). Such an environment may lead to a delay of correction by narrative expectations.

The real estate market in coastal cities within EU candidate countries could therefore be more susceptible to shocks driven by expectations. With convergence stories combined with anchoring and herding, market demand driven by sentiment may intensify price movements in those fast-developing cities. These results further emphasize that real estate markets within emerging as well as EU candidate countries are no exception to the principles of behavioral finance. Indeed, sentiment, anchoring, overconfidence, and herding work systematically within these real estate markets.

7. Policy Implications

From a behavioral and socio-economic standpoint, there are pronounced heterogeneities across the investor groups regarding housing market dynamics in coastal EU-candidate contexts. Systematic variation occurs among local residents, diaspora investors, Kosovo Albanians, and foreign buyers in information access, emotional attachment, and reference framing.

Consequently, demand reacts asymmetrically to price increases: affordability constraints steepen local participation, while sentiment-driven demand from non-local investors often remains resilient. This absence of symmetry helps explain continuous price growth beyond levels justified by local income fundamentals.

These findings suggest that optimism, anchoring, overconfidence, and herding lie at the very center of the determination of real estate in EU-candidate coastal markets. In turn, policy responses should address not only structural conditions, but also expectation-driven behavior. Four policy priorities emerge.

7.1. Enhancing Market Transparency

The strong anchoring among non-local investors reflects very limited access to reliable transaction data and the reliance on external benchmarking. A certified property-price register, available to the public and in a format commensurate with EU standards, would have reduced asymmetry in information. This would also serve to better anchor valuations in local fundamentals.

7.2. How to Enhance Investor Education and Raise Awareness on Behavioral Biases

Overconfidence and herding provide evidence of risk understatement and misplaced trust in social cues. Targeted investor-information programs, aimed above all at diaspora and foreign purchasers, need to underscore realistic rental yields, price-to-income ratios, and historical volatility. Such programs should go on to clearly point out common behavioral biases.

7.3. Preserving Affordability of Housing for Locals

Sentiment-driven demand by investors from outside the local area can lead to wider affordability gaps. Municipal authorities should incorporate price-to-income and price-to-rent indicators into zoning and development decisions. First-time homebuyer scheme support and increasing affordable rental supply go a long way in mitigating displacement risks. These measures aim to mitigate the unintended distributional effects of demand driven by sentiment rather than to regulate investment activity itself.

7.4. Stabilizing the Market Using Macroprudential Tools

Targeted macroprudential measures are hence in order, since heuristic-driven optimism can amplify demand cycles. Differentiated taxation for short-term resales, restrictions on speculative purchases, and enhanced source-of-funds verification could reduce volatility without discouraging productive long-term investment.

8. Limitations

The integration of behavioral insights into housing governance can inform discussions on transparency and housing affordability in the context of sentiment-driven real estate demand along EU-candidate coasts. It is in these contexts that optimism-driven narratives together with institutional transition greatly interact toward the shaping of real estate demand.

First, the application of a cross-sectional design means that sentiment, biases, and investment intentions can only be captured at one point in time. It cannot offer any insight into how using optimism or heuristic, might change along with shifts in macroeconomic conditions, EU-accession progress, or real estate cycles. It is in this respect that longitudinal research would be beneficial for assessing changes over time in these behavioral mechanisms. Although the cross-sectional design precludes any interpretation of causality in the strict econometric sense, the analysis is based on an explicit development of behavioral-finance theory, which states that sentiment and heuristic use precede investment intentions by construction. Apart from these suggestions, the analysis also does not account for a number of exogenous shocks-ssuch as EU negotiation dynamics, geopolitical tensions, or abrupt deteriorations in regional security conditions-that may independently result in changes in investor sentiment and expectations unrelated to fundamental conditions of the underlying market.

Second, the analysis is based on a sample drawn from Vlora, a developing coastal market shaped by tourism growth and convergence narratives. Although theoretically enriching, this context reduces generalizability to inland cities or more mature urban markets. A set of comparative studies across various Albanian cities or across Western Balkan and EU candidate coastal markets would verify whether similar behavioral patterns emerge elsewhere.

Third, it relies on self-reported survey data only, which may be vulnerable to social desirability, recall bias, or stated rather than revealed preferences. Use of validated scales and anonymity is helpful in countering any potential bias; however, future research should incorporate any administrative or transaction data such as purchase data, time to transaction, and leverage ratios to test if any of the behavioral processes found in this research result in any additional actual market outcomes.

These results are not definitive and indicate a number of areas for further analysis. Panel studies might examine the effect of news about accession to the EU or economic disturbances on the development of the intensity of bias and sentiment. Experimental methods, like information provision or vignette analysis, might investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between narratives, reference prices, and biases, and their ultimate influence on WTP and asset values. Lastly, the use of this framework to other candidate or highly developed regions along the EU’s coastline, including Montenegro, pre-accession Croatia, and selected Greek islands, would enable the drawing of comparative conclusions related to the institutional and tourism-related influence on the interrelation between sentiment, heuristics, and real estate investments.

9. Conclusions

This paper offers a behavioral finance analysis and empirical testing of the expectations-driven optimism towards accession to the European Union and its interaction with real estate investment decisions, especially in the case of Vlora, a coastal touristic town in Albania. The findings confirm that optimism influences to a large extent the core mechanisms related to behavioral finance: anchoring, overconfidence, and herding, and that the Albanian diaspora and the residents of Kosovo are much more susceptible to this, while the Vlora natives are much more cautious.

The results confirm the importance of using behavioral knowledge in the study of real estate market dynamics in emerging economies. In a setting where the cycles of optimism and expectations are particularly apparent, the projections of speculative forces can contribute toward a continued acceleration of prices, potentially aggravating affordability pressures for locals. As the Albanian economy moves ahead on its way toward integration into the European Union, the need to know and respond appropriately to this reality becomes particularly relevant.

Through the integration of EU-accession sentiment into a behavioral finance approach, this analysis links macro-level stories of convergence with micro-level investment in real assets.

Appendix A. Measurement Items and Scales

All latent constructs are measured using multi-item statements on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree, unless indicated otherwise. Items were adapted from behavioral finance and real estate psychology literature and adapted to the context of Vlora and Albania as an EU-candidate country.

Appendix A.1. EU-Accession Optimism (OPT)

"This construct represents forward-looking optimism with respect to Albania's potential accession to the EU and its economic implications."

OPT1: “I think that Albania will accede to the European Union in the coming years.”

OPT2: The accession of the EU into Albanian society would bring about great

OPT3: Membership in the EU will bring additional foreign investment to Albania.

OPT4: EU accession will provide improved long-term prospects for the coastal towns of Albania, like Vlora.

Appendix A.2. Anchoring (ANC)

Anchoring refers to how respondents use reference prices established in other markets when assessing Vlora properties.

ANC1: When I analyze real estate prices in Vlora, I conduct comparative analyses in neighboring countries like Greece or Croatia.

ANC2: Often, I think about the “cheapness” of Vlora in comparison to other Mediterranean locales.

ANC3: Price information from foreign markets helps me assess if property in Vlora costs little or much.

ANC4: My idea of a reasonable value for Vlora is deeply affected by the price of comparable flats abroad.

Appendix A.3. Overconfidence (OVC)

Overconfidence reflects the exaggeration of one's private information, judgment, and forecasting capabilities.

OVC1: “I am certain that I can accurately forecast how properties will be valued in Vlora in the years to come.”

OVC2: I feel I have more knowledge about the Vlora market for properties than the vast majority of the other purchasers.

OVC3: I value my personal judgment on property investment in Vlora more than that of professionals.

OVC4: I rarely feel the need to double-check my investment choices related to real estate investment.

Appendix A.4. Herding (HER)

Herding represents a measure of how strongly survey participants' answers can be influenced by others' behavior and opinions.

HER1: Recognizing that other people are also purchasing property in Vlora increases my inclination toward investing in Vlora.

HER2: Having my friends and family invest in Vlora increases my likelihood of investing.

HER3: I listen carefully to what people in my social network, including diaspora communities on social media sites, are saying about purchase in Vlora.

HER4: Seeing construction and new projects underway in Vlora encourages me to think about buying real estate.

Appendix A.5. Investment Intention (INT)

The measure for investment intention includes the constructs: intention to buy, action readiness, and attractiveness of making investments in Vlora.

INT1: In fact, I am seriously considering purchasing property in Vlora in the near future.

INT2: If I had the funds available, I would be prepared to buy an asset located within Vlora.

INT3: Investing in real estate properties in Vlora is an attractive investment for me.

INT4: I would certainly advise people to invest in Vlora properties.

Appendix A.6. Price Expectations (PEX)

Price expectations reflect beliefs about the dynamics of property prices in Vlora.

PEX1: I expect property prices in Vlora to increase over the next 3-5 years.

PHX2: Real estate investment in Vlora will prove more profitable in the future rather than now.

P.EX3: Not much chance that prices will decline in Vlora in the near term. (reverse-coded as necessary)

PEX4: Acquiring property in Vlora, presently, is likely to yield capital gains in the future.

Appendix A.7. Decision Speed Index (DSI)

The decision speed index reflects the speed within which the respondent is ready to arrive at the purchase decision after identifying the appropriate property.

Measured using a categorical item recoded into an ordinal index:

Higher scores represent more effective decision-making.

Appendix A.8. Risk Tolerance (RISK)

"Risk tolerance is one’s willingness to assume the associated risks that come when investing financially in real estate."

RISK1: I can assume financial risks if there is a possibility of gaining higher returns.

RISK2: I feel comfortable including investment instruments whose value may fluctuate.

RISK3: I like safe investments, even if they pay lower returns._ (reverse coded)

RISK4: Short-term risks of loss of property value can be accepted in view of likely long-term gains.

Appendix A.9. Market Familiarity (FAM)

The variable for market familiarity gauges the level of the respondents’ awareness of the Vlora real estate property market.

FAM1: I am quite informed about real estate prices in Vlora.

FAM2: I often read about news or information related to real estate development in Vlora.

FAM3: I visited real estate agencies or looked at properties in Vlora.

FAM4: On the whole, I believe I am acquainted with the Vlora property

Appendix A.10. Control Variables

Control variables were assessed as follows:

Age: Continuous (in years) or age groups.

Gender: Categorical (male, female, other orprefer no answer

Education: Categorical (secondary, bachelor’s,

Monthly income: Categorical (for example: <€1,

Financial literacy: Self-rated on a scale from 1 to 7 in terms of “How would you rate your financial knowledge?”

Appendix B. Executive Policy

Housing Market Pressures in Albanian Coastal EU-Candidate Cities: An Empirical Study

B.ILIADA

Context

The residential markets in coastal areas of candidate countries for EU membership have been seeing steady price appreciation that exceeds local fundamentals. Analysing data from Albania, house demand in those countries is found to be influenced by different segments of actors such as residents, buyers from Kosovo Albanians, diasporas, and foreign investors, who have different goals, information structures, and reaction functions.

Key Problem

Key

Housing demand is affected asymmetrically by the prices of houses. Although the affordability of the population forces this segment of the community to withdraw as prices increase, the sentiment-driven demand does not cease. Internal heterogeneities in the community of the local population, including the existence of sufficiently funded investors, reduce the natural ability of prices to self-correct. As a result, housing prices can appreciably surpass the income fundamentals of the region.

Main Drivers Identified

Demand is driven higher during price rises due to behavioral characteristics (optimism, anchoring, herding, and overconfidence).

Tourism promotion and the discourse on EU accession represent the coastal regions as new markets, highlighting their long-term prospects, thereby translating tourist interest into residential interest.

Inadequate access to capital for different investment groups leads to a presumed average income level being lower than real demand for housing in successful areas such as the coastal regions.

Policy Priorities

Create a public and official record of property prices and provide frequent public price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios consistent with EU statistical standards. Such a move can minimize the problem of asymmetry of information and cut over-reliance upon foreign standards, and align expectations with market fundamentals.

- 2.

Enhance Investor Information and Behavioral Awareness

It’s necessary to implement standardized pre-sale disclosure information regarding seasonality, yield, infrastructure, and regional regulatory patterns. Targeted information initiatives, especially for the diaspora and foreign-buyer segments, might focus on typical behavioral biases like anchoring, extrapolation, and herding-related prices distortions.

- 3.

Protect Housing Affordability for Local Residents

Affordability thresholds should be integrated with land use regulation, first-time buyer programs should be facilitated specifically for high-pressure markets, and existing rental housing should be expanded on a long-term basis. Such strategies are a critical start towards countering displacement pressures and maintaining a cohesive fabric of a rapidly developing coastal city like San Diego.

Policy Message

The housing market in coastal EU-candidate cities fails to self-correct. In view of the diversity of housing demand, increased transparency, and the management of expectation-driven behaviors, it is vital to ensure housing affordability, financial stability, and compliance with EU requirements in real estate management.

References

- Banerjee, A. V. A simple model of herd behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics 1992, 107(3), 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.; Thaler, R. Constantinides, G. M., Harris, M., Stulz, R. M., Eds.; A survey of behavioral finance. In Handbook of the Economics of Finance; Elsevier, 2003; Vol. 1B, pp. 1053–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.; Greenwood, R.; Jin, L.; Shleifer, A. Extrapolation and bubbles. Journal of Financial Economics 2018, 129(2), 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellona, EU. Housing in Europe: Outlining the Problem. 2024. Available online: https://eu.bellona.org/2024/02/20/housing-in-europe-outlining-the-problem/.

- Case, K. E.; Shiller, R. J.

Is there a bubble in the housing market?

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2003, 2003(2), 299–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čulig, L. Housing Trends in Croatia. Croatian Economic Survey. 2011. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/69067.

- EBRD. Transition Report 2015–16: Rebalancing Finance. 2015. Available online: https://tr-ebrd.com/tr15-16/en/index.html.

- European Commission. Albania 2024 Report – EU Enlargement. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52024SC0690.

- Eurostat. Housing in Europe – 2024 Edition. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/housing-2024.

- Glaeser, E. L.; Nathanson, C. G. An extrapolative model of house price dynamics. Journal of Financial Economics 2017, 126(1), 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Shleifer, A. Expectations of returns and expected returns. Review of Financial Studies 2014, 27(3), 714–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Phibbs, P. When tourists move in: How should urban planners respond to Airbnb? Journal of the American Planning Association 2017, 83(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S.; Kovachev, B.; Stanilov, K. Residential development in Sofia. In The Post-Socialist City. 2007. Available online: https://content.e-bookshelf.de/media/reading/L-4284-460fb63bf0.pdf.

- Housing Europe Observatory. The state of housing in the EU 2025: Trends in a nutshell. Housing Europe. 2025. Available online: https://www.stateofhousing.eu/The_State_of_Housing_in_Europe_2023.pdf.

- Housing Europe Observatory. The State of Housing in the EU 2025 – Trends in a Nutshell. 2025. Available online: https://www.housingeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/the_state_of_housing_in_the_eu_2025_trends-in-a-nutshell_digital.pdf.

- Housing Europe Observatory. The State of Housing in Europe 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.housingeurope.eu/resource-186/the-state-of-housing-in-europe-2024.

- IMF. Regional Economic Outlook: Europe. 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/EU.

- INSTAT. Tourism in Figures 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/12919/tourism-in-figures-2022.pdf.

- INSTAT. Movements of Citizens – March 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/en/themes/industry-trade-and-services/tourism-statistics/publications/2024/movements-of-citizens-march-2024/.

- INSTAT. Survey on Tourism: Holiday and Trips 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/toqjngvk/survey-on-tourism-holiday-and-trips_2024.pdf.

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindleberger, C. P.; Aliber, R. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, 6th ed.; 2011; Available online: https://archive.org/details/maniaspanicscras0000kind.

- Ministry of Tourism and Environment. National Tourism Strategy 2019–2023. 2019. Available online: https://turizmi.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/National-Tourism-Strategy-2019-2023-EN.pdf.

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/serials/oecd-tourism-trends-and-policies_g1ghbe02.html.

- Sidenros, J. Housing in the EU: Commodification Dynamics. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipe-berlin.org/fileadmin/institut-ipe/Dokumente/Working_Papers/Sidenros_WP_249_Final.pdf.

- Shiller, R. Speculative Asset Prices (Nobel Prize Lecture). 2014. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/shiller-lecture.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/publications.

- UNWTO; AIDA. Tourism Doing Business: Investing in Albania. 2024. Available online: https://aida.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/tourism-doing-business-investing-in-albania.pdf.

- World Bank. Western Balkans Regular Economic Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eca/publication/western-balkans-regular-economic-report.

- World Bank. International Tourism, Number of Arrivals – Albania. 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=AL.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).