1. Introduction

1.1. The Dark Matter Problem

The dark matter problem stands as one of the most profound puzzles in contemporary physics. Beginning with Fritz Zwicky’s observations of the Coma Cluster in 1933 [

1], evidence has accumulated across multiple independent channels that the gravitational dynamics of cosmic structures cannot be explained by visible baryonic matter alone. Galaxy rotation curves [

2,

3], gravitational lensing [

4,

5], the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies [

6], baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) [

7], and large-scale structure formation [

8] all point toward an additional gravitational source comprising approximately 27% of the cosmic energy density.

The standard CDM cosmological model interprets this “missing mass” as cold dark matter (CDM)—a hypothetical non-baryonic particle species that interacts gravitationally but remains essentially invisible to electromagnetic detection. Despite its remarkable phenomenological success, the CDM paradigm faces significant challenges:

- (i)

Non-detection: Decades of direct detection experiments [

9,

10,

11] have failed to identify dark matter particles, pushing constraints into increasingly fine-tuned parameter regions.

- (ii)

Small-scale tensions: The “core-cusp problem” [

12], “missing satellites” [

13], and “too-big-to-fail” [

14] problems reveal discrepancies between CDM N-body simulations and observed galactic structures.

- (iii)

Empirical regularities: The baryonic Tully-Fisher relation [

15,

16] and the radial acceleration relation [

17] exhibit tight correlations between baryonic and dynamical properties that appear fine-tuned in the CDM framework but emerge naturally in modified gravity scenarios.

- (iv)

tension: Recent weak lensing surveys [

18,

19] find systematically lower structure growth than predicted by Planck CMB parameters within

CDM, suggesting possible modifications to gravitational physics.

These challenges motivate exploring alternatives where the gravitational response itself is modified rather than postulating new particle species.

1.2. Modified Gravity Approaches

Modified gravity theories attempt to explain dark matter phenomenology through alterations to gravitational dynamics. The most influential framework is Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), introduced by Milgrom [

20], Milgrom [

21], which posits that the gravitational acceleration deviates from Newtonian behavior below a characteristic scale

m/s

2. MOND successfully predicts galaxy rotation curves [

22,

23] and naturally explains the baryonic Tully-Fisher relation, but struggles with cluster dynamics [

24] and lacks a fully satisfactory relativistic completion [

25,

26].

Nonlocal modifications of gravity represent another promising avenue. Deser Woodard [

27] introduced cosmological models with terms

, where

denotes the retarded Green’s function of the d’Alembertian. These corrections arise naturally from quantum loop effects and can drive late-time cosmic acceleration [

28]. Maggiore Mancarella [

29], Belgacem et al. [

30] developed the “RR” and “RT” nonlocal models, demonstrating compatibility with cosmological observations [

31].

Recent work by Deffayet Woodard [

32] presents a nonlocal realization of MOND that interpolates between cosmological and galactic regimes using a single framework, reproducing CMB, BAO, and structure formation while also addressing rotation curves. This demonstrates that nonlocal gravity can potentially unify phenomena typically attributed to dark matter across vastly different scales.

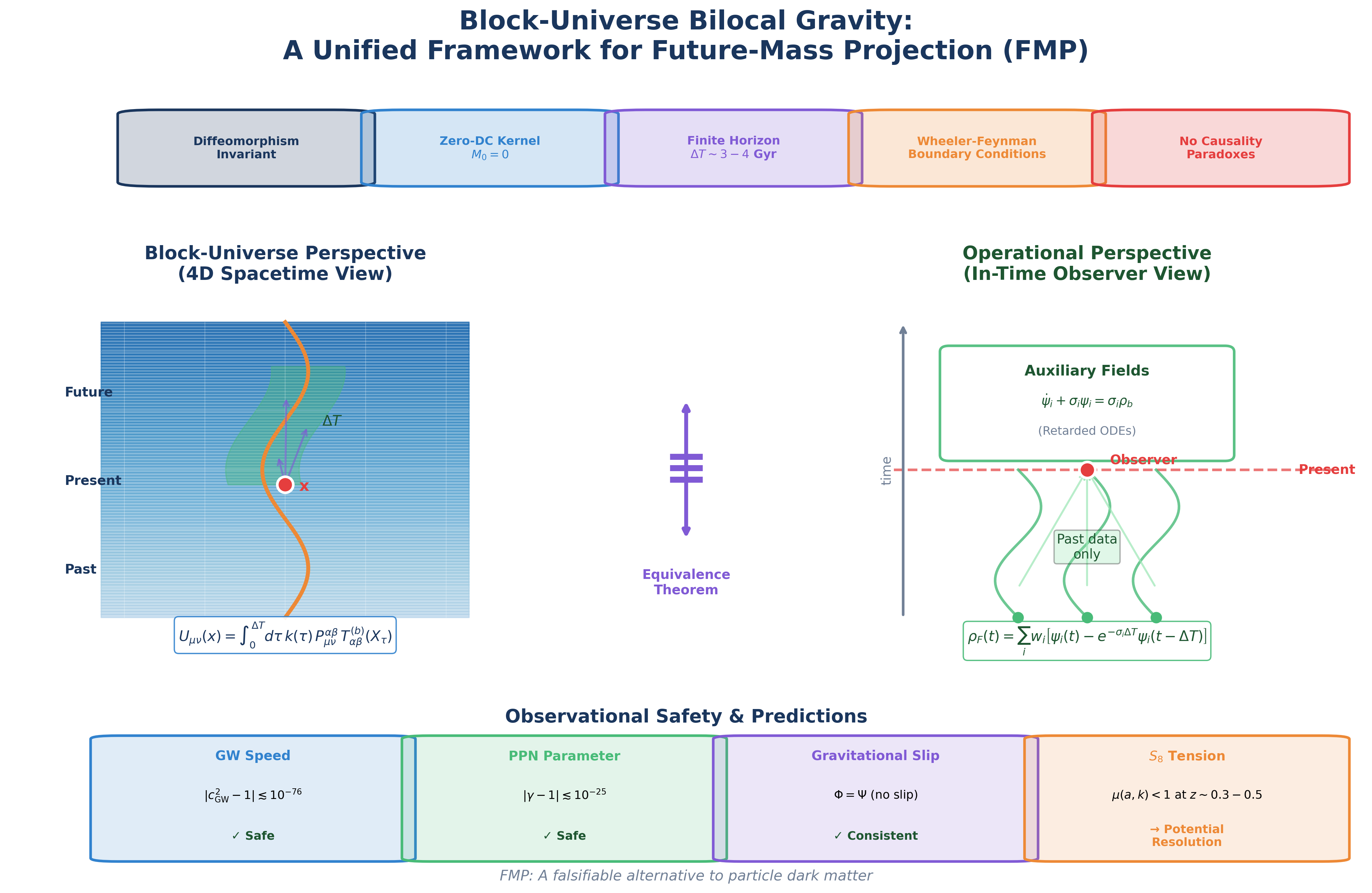

1.3. Future-Mass Projection: A New Paradigm

Future-Mass Projection (FMP) gravity represents a fundamentally distinct approach within the nonlocal gravity landscape. Rather than phenomenologically modifying acceleration laws or introducing inverse d’Alembertian corrections, FMP posits that the gravitational field responds to a worldline-localized bilocal functional of baryonic stress-energy, with support extending into a finite future domain along material worldlines.

The central ansatz of

FMP is:

where

is an effective source constructed from the baryonic stress-energy

via integration over a bounded future region along worldlines:

Here denotes the point reached by following the matter worldline through x for proper time , is a scalar temporal kernel, and is a tensor projector constructed from the parallel propagator.

This formulation immediately raises the question: How can a physically sensible theory depend on the “future”? The resolution lies in recognizing two mathematically equivalent but conceptually distinct perspectives.

1.4. The Two-Perspective Framework

The key insight of this paper is that FMP admits two equivalent formulations:

- 1.

Block-Universe (God’s-Eye) Perspective: In general relativity, spacetime is a four-dimensional manifold where past, present, and future coexist as a unified geometric structure. From this global viewpoint, the entire baryonic history is a single 4D object. The FMP modification is defined as a covariant bilocal functional of this object, with the kernel having support in a finite future domain. This perspective is mathematically clean and manifestly covariant.

- 2.

Operational (In-Time Observer) Perspective: An observer evolving along a worldline does not have direct access to future data. However, the same mathematical object can be represented through auxiliary fields satisfying retarded differential equations, combined with appropriate boundary conditions. This representation is what an operational observer would compute.

The connection between these perspectives is analogous to Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory in electrodynamics [

34,

35], where time-symmetric interactions between charges yield causal (retarded) radiation when appropriate absorber boundary conditions are imposed. In

FMP, the “future integral” in the block-universe formulation becomes mathematically equivalent to a retarded auxiliary-field system when final-state boundary conditions are enforced.

1.5. Theoretical Advantages over Dark Matter

The block-universe perspective offers several conceptual and practical advantages over the particle dark matter paradigm:

- (i)

Eliminates undetected particles: FMP requires no new particle species beyond the Standard Model, avoiding the persistent non-detection problem.

- (ii)

Unified explanation: A single kernel with 4 fundamental parameters (, , , ) can address phenomena from galactic to cosmological scales.

- (iii)

Natural regularities: The tight correlations in the radial acceleration relation emerge from the bilocal coupling between gravity and baryonic matter.

- (iv)

Falsifiability: The framework makes specific predictions for gravitational wave speed, PPN parameters, lensing geometry, and growth functions that can be tested with current and upcoming surveys.

- (v)

Theoretical elegance: The block-universe formulation naturally incorporates Wheeler-Feynman-type boundary conditions within a diffeomorphism-invariant framework.

1.6. Paper Organization

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical context, including nonlocal gravity, Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory, and the Schwinger-Keldysh formalism.

Section 3 presents the block-universe formulation with explicit kernel construction.

Section 4 develops the operational perspective via auxiliary fields and the CTP derivation.

Section 5 proves the equivalence theorem connecting both perspectives.

Section 6 discusses observational constraints and falsifiability.

Section 7 compares with previous

FMP versions and the dark matter paradigm.

Section 8 discusses conceptual implications and open questions.

Section 9 concludes.

2. Theoretical Context and Related Work

2.1. Nonlocal Gravity: From Quantum Corrections to Dark Phenomenology

Nonlocal modifications of gravity have deep roots in quantum field theory. When gravity is quantized perturbatively around flat or curved backgrounds, loop corrections generically produce nonlocal terms in the effective action [

45,

46]. These corrections involve the inverse d’Alembertian

acting on curvature invariants, leading to integro-differential equations of motion.

Deser Woodard [

27] pioneered the application of nonlocal gravity to cosmology, proposing models of the form

that can produce late-time acceleration without a cosmological constant. The key insight is that

, when defined via the retarded Green’s function, grows during matter domination and triggers modified dynamics at late times [

28].

The “RR” model of Maggiore Mancarella [

29] takes:

where

m is a mass parameter. This model successfully fits CMB, BAO, SNIa, and structure formation data [

30], and has been tested against lunar laser ranging constraints [

31].

Capozziello et al. [

33] provide a comprehensive overview of nonlocal gravity cosmology, exploring various functional forms

,

, and

and their cosmological solutions. Noether symmetry methods enable selection of viable functional forms and determination of exact solutions.

FMP differs from these approaches in several key aspects:

The nonlocality is worldline-localized rather than spacetime-distributed.

The kernel has finite support , providing a natural cutoff.

The zero-DC condition ensures background neutrality.

The formulation directly targets dark matter phenomenology rather than dark energy.

2.2. Wheeler-Feynman Absorber Theory

The Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory [

34,

35] provides crucial conceptual underpinning for understanding how “future-dependent” theories can be physically sensible. In classical electrodynamics, the field of a point charge can be decomposed into retarded (outgoing) and advanced (incoming) components:

Wheeler and Feynman showed that if the universe contains a “perfect absorber” in the future (i.e., all outgoing radiation is eventually absorbed), then the sum of:

- 1.

the retarded field from the source, and

- 2.

the advanced response from all absorbers,

yields precisely the standard retarded electromagnetic field, including the correct radiation reaction force. The theory is time-symmetric at the fundamental level but produces time-asymmetric (causal) observables through the absorber boundary condition.

The philosophical significance was analyzed by Price [

36], who emphasized that the arrow of radiation derives from thermodynamic considerations rather than fundamental time-asymmetry. Hoyle Narlikar [

37] and Narlikar [

38] extended the absorber approach to gravity, developing a Machian theory where gravitational interactions are mediated by direct particle actions involving both retarded and advanced components.

For FMP, the Wheeler-Feynman framework suggests that:

- 1.

A “future-pointing” kernel does not imply acausal signaling.

- 2.

The boundary condition (fields bounded at late times) selects physical solutions.

- 3.

The apparent time-asymmetry emerges from global (cosmological) considerations.

2.3. Schwinger-Keldysh (Closed-Time-Path) Formalism

The Schwinger-Keldysh or closed-time-path (CTP) formalism [

39,

40] provides the standard framework for computing real-time, causal expectation values in quantum field theory. The generating functional is defined on a time contour that runs forward from

to

, then backward to

:

where

is the influence functional from integrating out environment degrees of freedom.

The influence functional generates bilocal kernels that decompose into retarded (

), advanced (

), and Hadamard (

) components:

In semiclassical and stochastic gravity [

41,

42], integrating out matter fields produces an influence functional with these kernel structures. The equations of motion derived from the CTP effective action are manifestly causal: they depend only on initial data.

The relevance to FMP is direct: the “future-pointing” kernel in the block-universe formulation corresponds to an advanced kernel in the CTP decomposition. With appropriate boundary conditions, the CTP variation yields retarded equations of motion, establishing the operational equivalence.

2.4. Bitensor Technology

Bilocal constructions require the mathematical machinery of bitensors [

43,

44]. The fundamental objects are:

- 1.

Synge world function: Half the squared geodesic distance between

x and

:

where

is the geodesic from

to

, and

(spacelike) or

(timelike).

- 2.

Parallel propagator: Transports vectors along the geodesic:

- 3.

Van Vleck-Morette determinant: Controls the spreading of geodesics.

These constructions are rigorously defined within a convex normal neighborhood where geodesics between any two points are unique. For FMP with few Gyr in a smooth FRW background, this condition is satisfied.

3. Block-Universe Formulation

3.1. The Block-Universe Ontology

In general relativity, spacetime is a four-dimensional pseudo-Riemannian manifold

. From the “block-universe” or “eternalist” perspective [

36,

47], all events—past, present, and future—exist equally as points in this geometric structure. There is no privileged “now”; the apparent flow of time is a feature of conscious experience, not fundamental physics.

This perspective is particularly natural in general relativity because:

- 1.

The theory is diffeomorphism-invariant, with no preferred time foliation.

- 2.

Solutions to Einstein’s equations are complete 4D metrics, not evolving 3D geometries.

- 3.

The causal structure (light cones) is determined by the metric, not by an external time parameter.

Within this framework, it is entirely consistent to define gravitational dynamics as a functional of the complete stress-energy distribution across all of spacetime. The FMP modification takes this perspective and constructs a bilocal functional with support restricted to a finite future domain along worldlines.

3.2. Worldline-Localized Kernel Construction

A naive bilocal integral over the full 4D future light cone,

suffers from several problems: computational intractability (4D integration), extreme sensitivity to distant matter, and inconsistency with the operational 1D form used in phenomenology.

The resolution is worldline projection: restrict the integral to the material worldline through x.

Definition 1 (Worldline map).

Given the matter 4-velocity field (), the worldline map is the integral curve of passing through x at :

Definition 2 (Worldline-localized delta).

where is the spatial metric orthogonal to , and .

With this construction, the 4D integral collapses to a 1D worldline integral:

Theorem 1 (4D to 1D reduction).

The bilocal integral with worldline-localized kernel reduces exactly to:

where .

3.3. Tensor Projector Structure

The tensor projector must be constructed to ensure:

- 1.

Covariant transformation under diffeomorphisms,

- 2.

Controlled gravitational slip (relation between metric potentials and ).

We adopt the trace-adjusted form:

where

is the parallel propagator along the worldline, and

is a trace-mixing parameter.

For , the projector ensures (no gravitational slip) when acting on dust stress-energy, as required for consistency with observations.

3.4. The Zero-DC Kernel

The scalar temporal kernel

must satisfy the

zero-DC condition:

This condition is essential for several reasons:

- 1.

It ensures that vanishes for homogeneous, time-independent configurations, preserving the cosmological background.

- 2.

It implies the kernel must change sign within its support, acting as a “high-pass filter” on matter fluctuations.

- 3.

It provides suppression of FMP effects in quasi-stationary environments like the Solar System.

The simplest kernel satisfying zero-DC with finite support

is linear:

where

(dimensionless) controls the strength of the

FMP effect.

3.5. Kernel Moments

The temporal kernel moments encode the effective time structure:

For , the moments and , producing gravitational suppression in certain regimes—the signature needed to address the tension.

3.6. Diffeomorphism Invariance and Covariant Conservation

The

FMP action is constructed to be diffeomorphism-invariant:

Theorem 2 (Noether conservation).

If the total action is invariant under diffeomorphisms, then the effective stress-energy tensor is covariantly conserved:

Proof sketch. Under an infinitesimal diffeomorphism

:

Diffeomorphism invariance of

S implies

. Using the Bianchi identity

and the field equations

, we obtain

. □

3.7. Spatial Response Function

For cosmological perturbations in Fourier space, the worldline kernel induces an effective spatial response:

where

is the 1D worldline integral result, and

encodes the spatial scale dependence.

A phenomenologically motivated UV-suppressed form is:

with

/Mpc the characteristic

FMP scale and

.

This ensures:

4. Operational (In-Time Observer) Formulation

4.1. The Operational Challenge

An observer at spacetime point x, evolving forward in time, cannot directly measure stress-energy at future points . How, then, can such an observer compute the FMP contribution ?

The answer involves two complementary approaches:

- 1.

Moment/derivative expansion: Valid when field evolution is slow ().

- 2.

Auxiliary-field representation: Valid for arbitrary evolution timescales.

Both yield the same result as the block-universe integral under appropriate boundary conditions.

4.2. Moment Expansion (Adiabatic Regime)

For cosmological perturbations where the evolution timescale

Gyr greatly exceeds the kernel horizon

–4 Gyr, we expand the future stress-energy in a Taylor series:

Substituting into Eq. (

14):

using

(zero-DC condition).

Key insight: The “future integral” becomes an expression involving only present-time fields and their derivatives. No future data is required. The moments encode the kernel’s time structure, and the expansion is valid when fields evolve slowly compared to .

For cosmological perturbations with , the expansion gives ∼1–3% accuracy when truncated at second order.

4.3. Auxiliary-Field Representation (General Regime)

For galaxy-scale dynamics where yr , the moment expansion fails. The full integral form must be used, but can be reformulated through auxiliary fields.

The central mathematical result is:

Lemma 1 (Windowed exponential memory).

For any function and decay rate :

where is the infinite-memory auxiliary field:

For the linear zero-DC kernel, a Prony decomposition

with

yields:

where each

satisfies the

retarded first-order ODE:

Critical observation: The auxiliary field equations (

32) are manifestly retarded—

depends only on

at times

. The cutoff at

is exact, not approximate. Implementation requires storing

history or solving a delay-differential system.

4.4. CTP Derivation

The Schwinger-Keldysh formalism provides a rigorous foundation for the operational equivalence. The FMP construction corresponds to a constrained advanced kernel with:

- 1.

Finite support: ,

- 2.

Zero-DC: .

Lemma 2 (CTP retarded equivalence).

Let be an advanced kernel satisfying the above conditions. Define the “future integral”:

Then under the final-state boundary condition

the equations of motion derived from are equivalent to a purely retarded system.

Proof sketch Step 1:. Taylor expansion of

yields:

where

and

is a boundary functional.

Step 2: With , the leading term vanishes, and the moment expansion involves derivatives at t.

Step 3: The derivatives are determined by the equations of motion from initial data.

Step 4: The boundary condition (

34) sets

for fields approaching equilibrium.

Thus the “future integral” equals the moment expansion, which is operationally retarded. □

4.5. Physical Interpretation: Absorber Condition

The final-state boundary condition (

34) is the gravitational analog of the Wheeler-Feynman absorber condition: fields remain bounded at late times, consistent with thermodynamic equilibrium in the far future.

This is not a fine-tuned assumption but a natural consequence of:

- 1.

The expansion and dilution of the universe.

- 2.

The thermodynamic arrow of time (entropy increase toward the future).

- 3.

The requirement that perturbations do not grow without bound.

The “future dependence” in the block-universe formulation is thus physically equivalent to imposing specific boundary conditions at late times—just as in Wheeler-Feynman electrodynamics.

5. Equivalence Theorem

5.1. Statement of the Theorem

Theorem 3 (Block-to-Operational Equivalence). Under the following assumptions:

-

(A1)

Worldline-projected kernel (15) with trace-adjusted projector, -

(A2)

-

(A3)

Stability: bounded operator norm and no runaway modes,

-

(A4)

Final-state boundary condition (34),

the following equivalences hold:

(I) Cosmological regime(): The gauge-invariant metric potentials from the block-universe form equal those from the derivative-expansion operational form up to .

(II) Galaxy regime(): The block-universe form is equivalent to the auxiliary-field system (32)–(31), yielding identical .

In both regimes, no future data is required for the operational computation.

5.2. Proof Strategy

The proof proceeds through several key steps:

Step 1: Auxiliary field matching. The “block-universe” future integral (with

):

equals the “operational” past-directed expression:

if and only if the boundary condition

holds.

Step 2: Green’s function structure. The infinite-memory auxiliary field admits two representations:

Under the boundary condition, both yield the same .

Step 3: Metric perturbations. In the weak-field limit, the metric potentials satisfy:

Whether is computed from the block-universe integral or the operational auxiliary-field system, the result is identical, hence and agree.

5.3. Validity Domains

The equivalence holds within specific validity domains:

Table 1.

Validity domains for the block-to-operational equivalence.

Table 1.

Validity domains for the block-to-operational equivalence.

| Regime |

Expansion |

Error |

| Cosmology () |

Moments |

|

| Galaxies ( yr) |

Auxiliary fields |

Exact |

| Solar System (quasi-static) |

Zero-DC suppression |

|

5.4. No Paradoxes

The equivalence theorem demonstrates that no causal paradoxes can arise in FMP:

- 1.

The “future” contribution is not a controllable signal—it is a fixed functional of the stress-energy distribution.

- 2.

An agent cannot encode arbitrary information in that would be decoded by the FMP response at an earlier time.

- 3.

Self-consistent solutions exist: the 4D block-universe picture is internally consistent, not paradoxical.

- 4.

The operational formulation involves only retarded (past-directed) auxiliary field equations.

6. Observational Constraints and Falsifiability

6.1. Gravitational Wave Speed

Post-GW170817, any modification of gravity must satisfy

[

48].

For subhorizon gravitational wave modes (

,

), the

FMP modification to the dispersion relation scales as:

where both ratios provide suppression.

Numerical estimate for LIGO (

Hz):

Combined with

and

:

This is vastly below the observational bound.

6.2. PPN Parameters

The Parameterized Post-Newtonian (PPN) parameters

and

are constrained by Solar System tests. The Cassini bound is

[

49].

FMP effects in the Solar System are suppressed by:

- 1.

-

Zero-DC suppression: For quasi-stationary sources (

):

With solar secular evolution

s

−1 and

s:

- 2.

UV suppression in : At Solar System scales,

m

−1:

The

FMP modification to gravity involves

:

This is far below the Cassini bound.

6.3. Gravitational Slip

The gravitational slip parameter is constrained by weak lensing and galaxy clustering comparisons.

For the trace-adjusted projector (

15) with

acting on dust (

):

Proposition 1 (Vanishing slip).

The trace-free (anisotropic) part of vanishes:

hence .

This follows from the projector symmetry: (parallel transport preserves the orthogonal decomposition), so the momentum flux does not contribute to .

6.4. Linear Cosmological Perturbations

The modified Poisson and lensing equations are:

with effective gravitational coupling:

where

is the growth rate and

is the

FMP ratio.

For and –4 Gyr, in a band around –0.5, –0.2 h/Mpc, potentially resolving the tension.

6.5. Falsifiability Criteria

FMP is falsifiable through:

- 1.

Bullet Cluster geometry: If FMP predicts lensing mass centered on the X-ray gas (not offset from it), the theory is ruled out.

- 2.

Galaxy rotation universality: If different galaxies require drastically different , FMP loses predictive power.

- 3.

GW speed: Detection of at level rules out leading-order FMP.

- 4.

RSD-Lensing consistency: Inconsistent and from redshift-space distortions and weak lensing would falsify FMP.

- 5.

EP tests: Detection of composition-dependent gravitational effects exceeding activity-filter predictions.

7. Comparison with Previous Formulations and the Dark Matter Paradigm

7.1. Evolution of FMP Formulations

The FMP framework has evolved through several versions, each addressing specific theoretical challenges:

Table 2.

Evolution of FMP formulations.

Table 2.

Evolution of FMP formulations.

| Version |

Key Developments |

| v1 |

Basic block-universe formulation; 4D bilocal integral; zero-DC condition introduced |

| v2 |

Worldline projection; CTP derivation; activity filter; matter EoMs |

| v3 |

Proper geometric delta decomposition; windowed exponentials; corrected GW scaling

|

| v4 |

Exact finite-horizon identity; consistent GW/PPN estimates; derived

|

| v5 |

Auxiliary-field matching without Taylor expansion; projector symmetry argument; honest parameter counting |

The present paper synthesizes these developments into a unified, pedagogically accessible framework.

7.2. Key Technical Improvements

- 1.

4D vs. 1D resolution: The tension between 4D covariant definitions and 1D worldline convolutions is resolved through matter-flow projection using the geometric delta decomposition (Lemma 2.2 in v3).

- 2.

Positivity/zero-DC conflict: A kernel with zero-DC (, requiring sign change) and (growth suppression) cannot be positive semi-definite. The stability criterion is replaced by bounded operator norm and passivity.

- 3.

Finite horizon implementation: The exact windowed-exponential identity (

28) provides a hard cutoff at

without approximation.

- 4.

Retarded operational form: The auxiliary field equations (

32) are manifestly past-directed; the equivalence to the “future integral” requires boundary conditions, not access to future data.

- 5.

Activity filter derivation: The filter scale emerges from the Prony decomposition rates, not an ad hoc choice.

7.3. Comparison with CDM + Dark Matter

Table 3.

Comparison between CDM + dark matter and FMP.

Table 3.

Comparison between CDM + dark matter and FMP.

| Aspect |

CDM + DM |

FMP |

| New particles |

Yes (CDM) |

No |

| Detection status |

Null after 40 years |

N/A |

| Cosmological parameters |

6 |

6 |

| Dark sector parameters |

1 (CDM normalization) |

4 (, , , ) |

| Total |

7 |

10 |

| Galaxy RC universality |

Requires tuned halos |

Single kernel |

| Radial acceleration relation |

Fine-tuned |

Natural |

|

tension |

Unresolved |

Potential resolution |

While FMP has more parameters, it makes distinct scale-dependent predictions testable across multiple regimes with a single parameter set, rather than requiring per-object halo fitting.

7.4. Theoretical Advantages of the Block-Universe Perspective

The block-universe formulation of FMP offers several theoretical advantages:

- 1.

Manifest covariance: The bilocal functional is constructed from geometric objects (parallel propagator, Synge function), ensuring diffeomorphism invariance.

- 2.

Natural boundary conditions: The Wheeler-Feynman-type absorber condition emerges naturally from thermodynamic considerations, not as an ad hoc addition.

- 3.

Unified dark phenomenology: Both galactic and cosmological “dark matter” effects arise from the same kernel with different relevant moments.

- 4.

No new fields: Unlike scalar-tensor modifications (TeVeS, Bekenstein), FMP requires no additional propagating degrees of freedom beyond the metric and baryonic matter.

- 5.

Clear ontological status: The 4D stress-energy tensor is a well-defined geometric object; no “dark matter particles” need exist.

8. Discussion

8.1. Philosophical Implications

The FMP framework raises interesting philosophical questions about time, causality, and the ontological status of spacetime.

Block universe vs. presentism: The block-universe formulation treats past, present, and future as equally real. This is the standard interpretation in relativity theory, though some philosophers prefer “presentist” alternatives. FMP does not adjudicate this debate but shows that even “future-dependent” dynamics can be operationally equivalent to retarded formulations.

Causality: No operational paradoxes arise because the “future” contribution is not a controllable signal. The equivalence theorem demonstrates that the apparent future-dependence reduces to boundary conditions on the late-time behavior of fields.

Thermodynamic arrow: The absorber-type boundary condition aligns with the thermodynamic arrow of time. The universe’s expansion and dilution ensure that fields remain bounded at late times, selecting the physical solution.

8.2. Relation to Other Frameworks

MOND:FMP is fundamentally distinct from MOND. While MOND modifies the acceleration law phenomenologically, FMP is a bilocal field theory with causal kernels based on Wheeler-Feynman principles. The characteristic scale in MOND corresponds to the kernel parameters in FMP, but the theoretical structures are different.

Entropic gravity: Verlinde [

50] proposed that gravity is an entropic force. While

FMP does not claim gravity is entropic in origin, the kernel structure may ultimately derive from statistical-mechanical coarse-graining of N-body correlations—a connection explored in companion work on entropic

FMP.

Deffayet-Woodard nonlocal MOND: The recent work by Deffayet Woodard [

32] shares the goal of explaining dark matter phenomenology through nonlocal gravity but uses a different construction based on inverse d’Alembertian operators and mimetic fields.

FMP’s worldline-localized kernel provides a complementary approach with potentially different phenomenological signatures.

8.3. Open Questions and Limitations

- 1.

Microscopic derivation: The kernel remains phenomenological. A derivation from N-body statistical mechanics, thermodynamic principles, or quantum gravity would strengthen the framework.

- 2.

Spatial response: The factorization is an ansatz. Rigorous derivation requires specifying the full 3D kernel structure.

- 3.

Nonlinear regime: N-body simulations with the auxiliary-field system are needed for structure formation and halo profiles.

- 4.

Radiation era: Behavior during radiation domination and recombination requires separate analysis, as the matter 4-velocity field is ill-defined for relativistic species.

- 5.

Cluster mergers: Detailed Bullet Cluster modeling requires numerical implementation of the full FMP equations.

9. Conclusions

We have presented a comprehensive formulation of Future-Mass Projection gravity in two mathematically equivalent perspectives:

- 1.

Block-Universe: The gravitational field responds to a covariant worldline-localized bilocal functional of baryonic stress-energy, with support in a finite future domain .

- 2.

Operational: An in-time observer computes identical effects using retarded auxiliary field equations, with the equivalence established through boundary conditions analogous to Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory.

The framework satisfies essential consistency requirements:

Covariant conservation via diffeomorphism invariance.

Background neutrality through the zero-DC condition .

Stability through bounded operator norm and passivity.

Observational safety: , , .

FMP offers a falsifiable alternative to particle dark matter with several theoretical advantages:

No undetected exotic particles required.

Unified explanation across galactic and cosmological scales.

Natural emergence of observed correlations (radial acceleration relation).

Clear falsification criteria testable with current and upcoming surveys.

The ultimate test will be whether FMP can match the full ensemble of cosmological and astrophysical data with comparable or greater predictive power than CDM + particle dark matter. The mathematical machinery developed here provides the foundation for such a fair comparison.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues for discussions on causality, kernel inference, and galaxy dynamics, and acknowledges constructive criticism that substantially improved the mathematical rigor and clarity of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- F. Zwicky, Helv. Phys. Acta 6, 110 (1933).

- V. C. Rubin, W. K. Ford, and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J. 238, 471 (1980).

- Y. Sofue and V. Rubin, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 39, 137 (2001).

- D. Clowe et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 648, L109 (2006).

- R. Massey, T. Kitching, and J. Richard, Rep. Prog. Phys. 73, 086901 (2010).

- N. Aghanim et al. (Planck Collaboration), Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020).

- D. J. Eisenstein et al., Astrophys. J. 633, 560 (2005).

- V. Springel et al., Nature 440, 1137 (2006).

- E. Aprile et al. (XENON Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 111302 (2018).

- LZ Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 041002 (2023).

- PandaX-4T Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 191001 (2024).

- W. J. G. de Blok, Adv. Astron. 2010, 789293 (2010).

- A. Klypin et al., Astrophys. J. 522, 82 (1999).

- M. Boylan-Kolchin, J. S. Bullock, and M. Kaplinghat, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 415, L40 (2011).

- S. S. McGaugh et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 533, L99 (2000).

- F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, and J. M. Schombert, Astron. J. 152, 157 (2016).

- S. S. McGaugh, F. Lelli, and J. M. Schombert, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 201101 (2016).

- C. Heymans et al. (KiDS Collaboration), Astron. Astrophys. 646, A140 (2021).

- DES Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 105, 023520 (2022).

- M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 365 (1983).

- M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 371 (1983).

- R. H. Sanders and S. S. McGaugh, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40, 263 (2002).

- B. Famaey and S. S. McGaugh, Living Rev. Relativ. 15, 10 (2012).

- R. H. Sanders, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 342, 901 (2003).

- J. D. Bekenstein, Phys. Rev. D 70, 083509 (2004).

- C. Skordis and T. Złośnik, Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 161302 (2021).

- S. Deser and R. P. Woodard, Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 111301 (2007).

- R. P. Woodard, Found. Phys. 44, 213 (2014).

- M. Maggiore and M. Mancarella, Phys. Rev. D 90, 023005 (2014).

- E. Belgacem et al., J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 03, 002 (2018).

- E. Belgacem et al., J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 02, 035 (2020).

- C. Deffayet and R. P. Woodard, arXiv:2512.10513 (2024).

- S. Capozziello, M. Capriolo, and S. Nojiri, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 31, 2130009 (2022).

- J. A. Wheeler and R. P. Feynman, Rev. Mod. Phys. 17, 157 (1945).

- J. A. Wheeler and R. P. Feynman, Rev. Mod. Phys. 21, 425 (1949).

- H. Price, Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- F. Hoyle and J. V. Narlikar, Proc. R. Soc. A 282, 191 (1964).

- J. V. Narlikar, Action at a Distance in Physics and Cosmology (Freeman, 1974).

- J. Schwinger, J. Math. Phys. 2, 407 (1961).

- L. V. Keldysh, Sov. Phys. JETP 20, 1018 (1965).

- B. L. Hu and E. Verdaguer, Living Rev. Relativ. 11, 3 (2008).

- E. A. Calzetta and B. L. Hu, Nonequilibrium Quantum Field Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- J. L. Synge, Relativity: The General Theory (North-Holland, 1960). North-Holland.

- E. Poisson, A. Pound, and I. Vega, Living Rev. Relativ. 14, 7 (2011).

- A. O. Barvinsky, Phys. Lett. B 572, 109 (2003).

- J. F. Donoghue, Phys. Rev. D 50, 3874 (1994).

- V. Petkov, Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime (Springer, 2006).

- B. P. Abbott et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 848, L13 (2017).

- B. Bertotti, L. Iess, and P. Tortora, Nature 425, 374 (2003).

- E. Verlinde, J. High Energy Phys. 04, 029 (2011).

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity (University of Chicago Press, 1984).

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation (W. H. Freeman, 1973).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).