Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- An LSTM-EKF-based dynamic attitude estimation algorithm is proposed to address the degradation of estimation accuracy caused by visual information loss. By integrating temporal prediction into the EKF framework, the proposed method enhances the stability and robustness of attitude estimation under vision-degraded conditions;

- A visual prediction LSTM network is designed to compensate for missing visual measurements, providing reliable pseudo-observations for the EKF when visual data are unavailable. This enables stable attitude estimation during a certain degree of visual occlusion and effectively extends the measurable angular range of the attitude measurement system;

- Extensive experimental validations are conducted on a precision turntable platform, including long-term reciprocating rotation experiments, visual occlusion scanning experiments, and ablation studies. The results demonstrate that the proposed LSTM-EKF approach achieves higher accuracy and stronger robustness than EKF and AKF methods, particularly under visual occlusion.

2. Principle of Dynamic Attitude Measurement

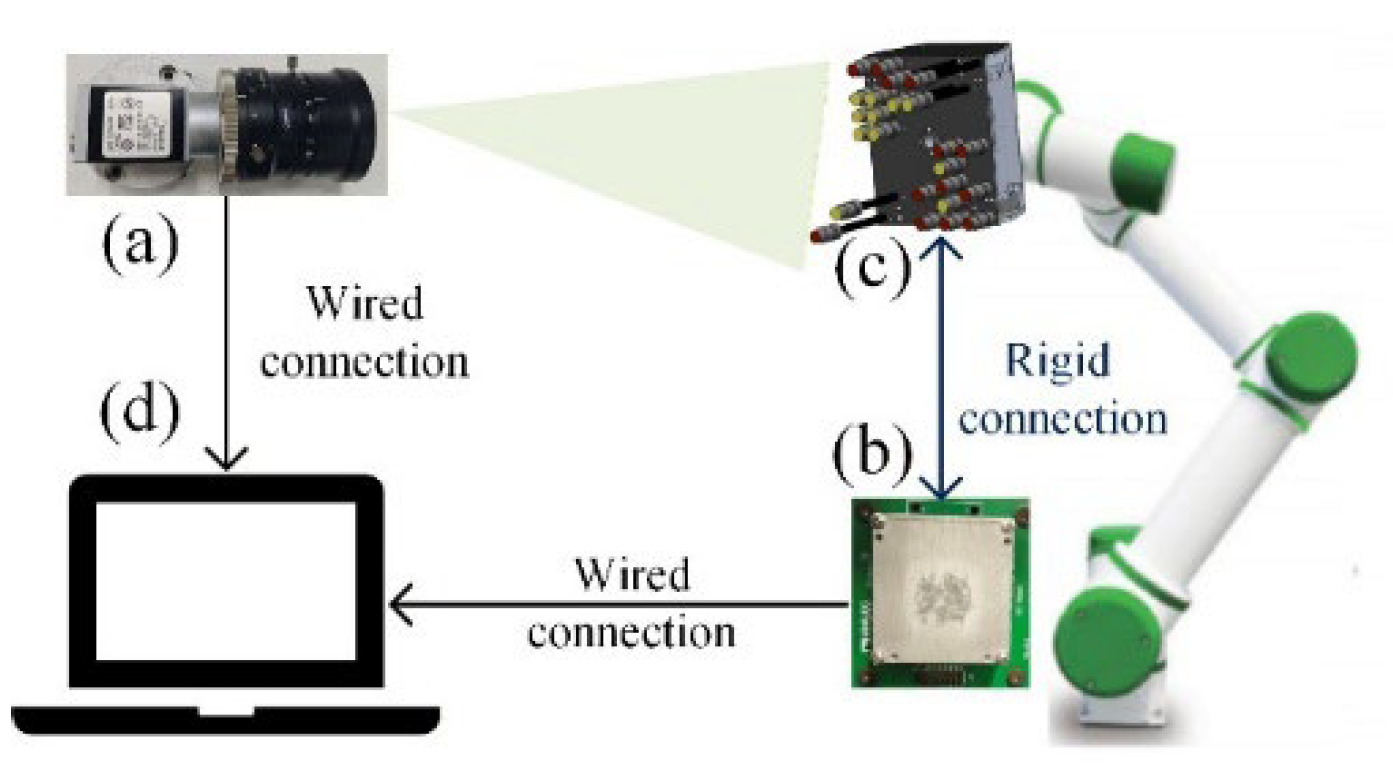

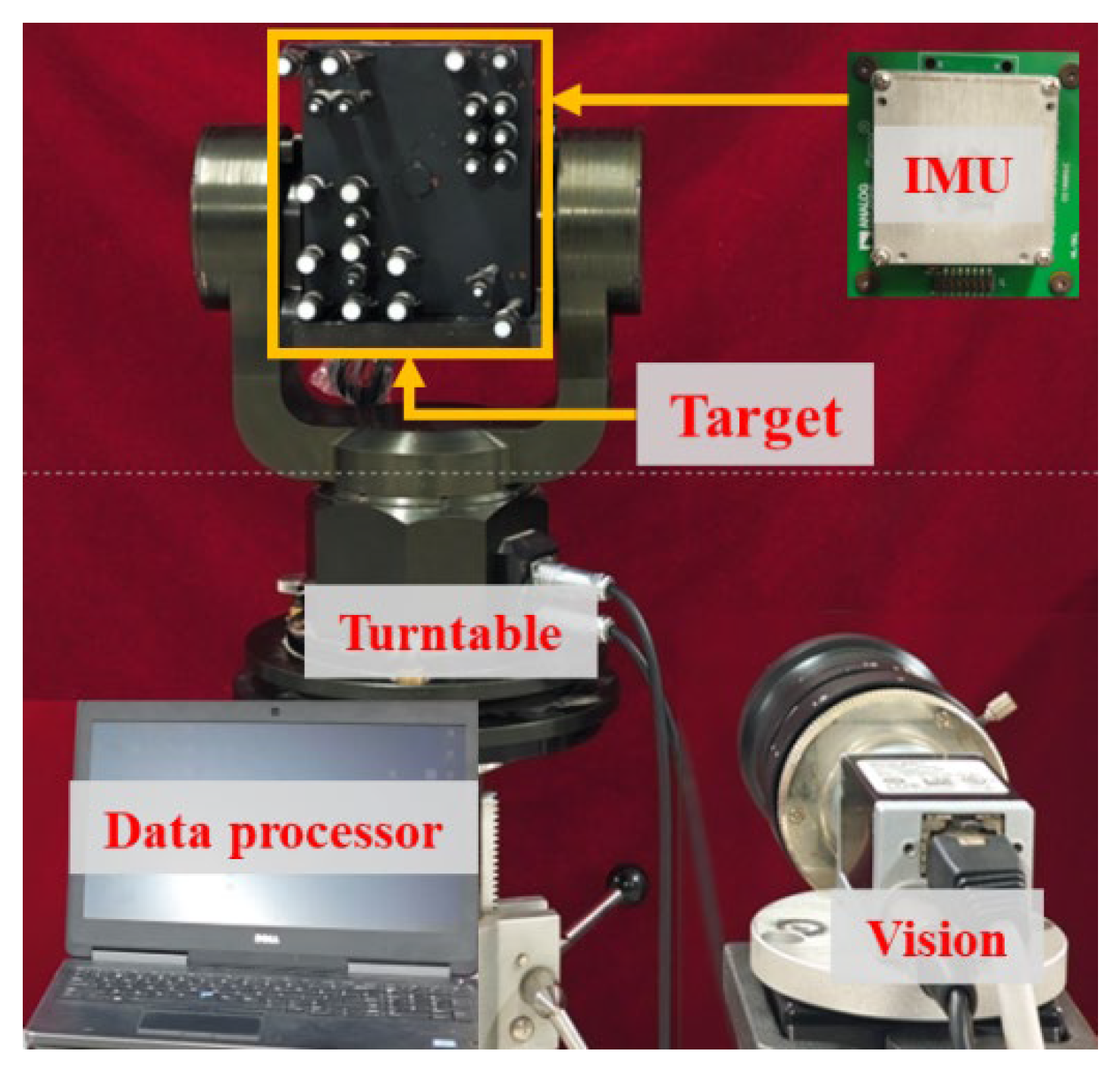

2.1. Attitude Measurement System Components

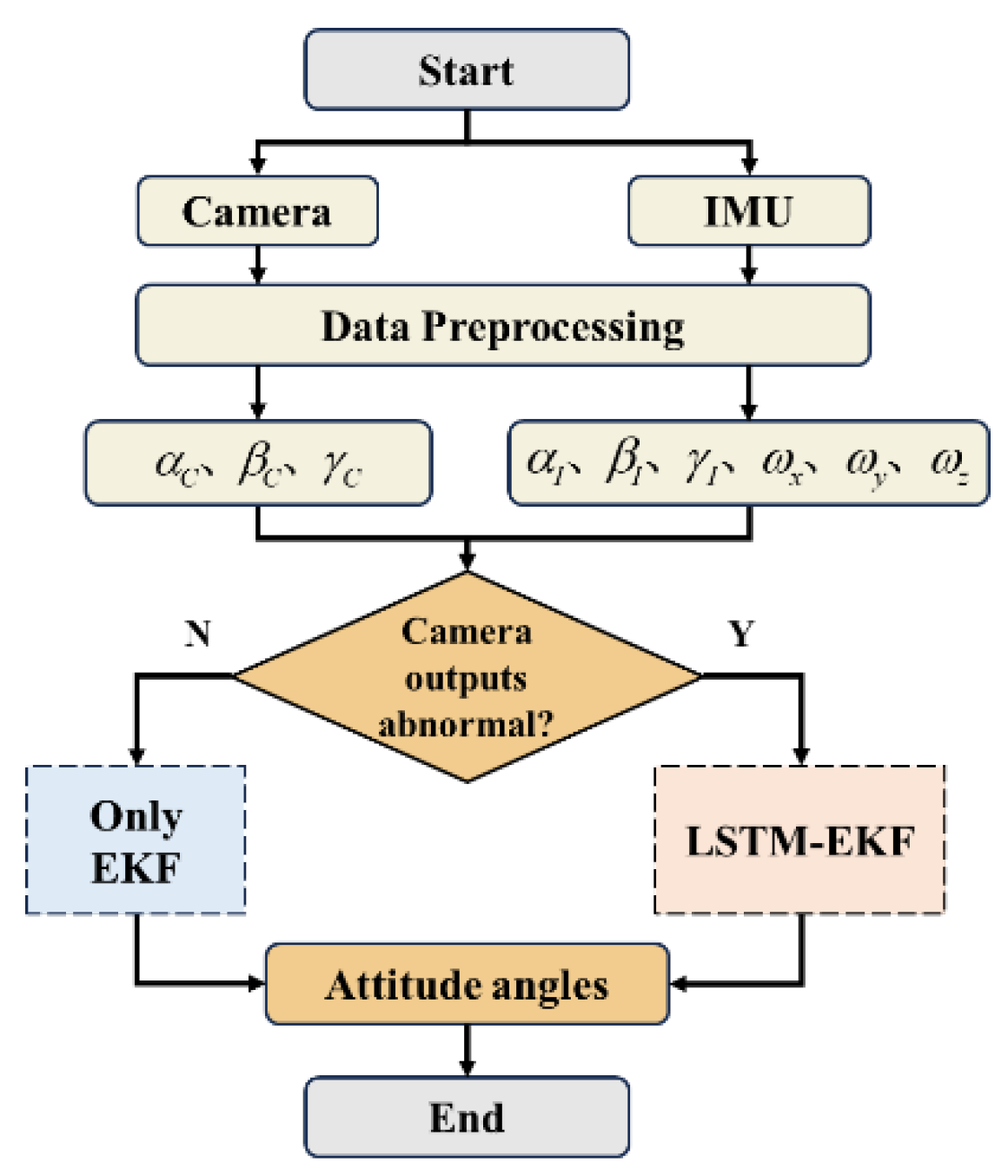

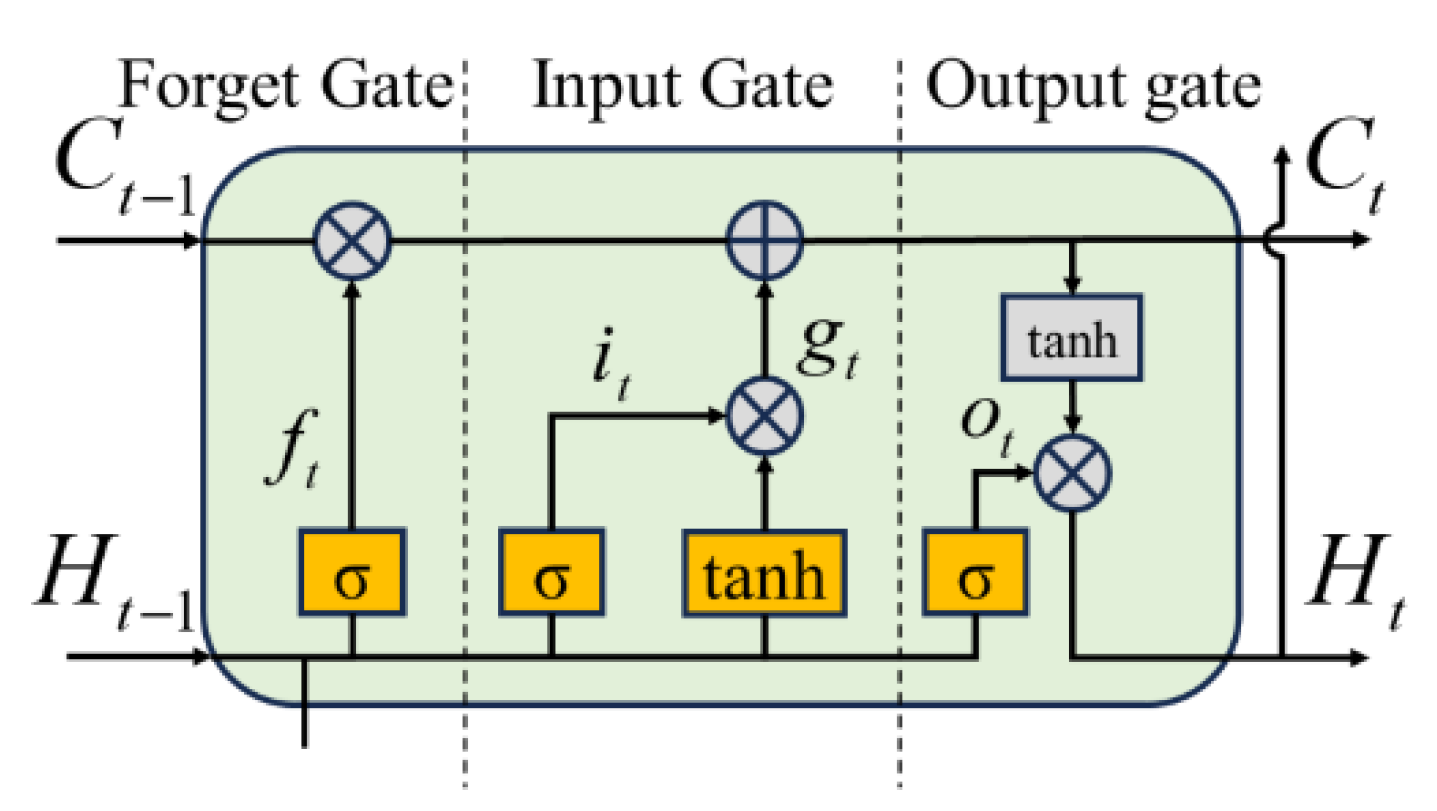

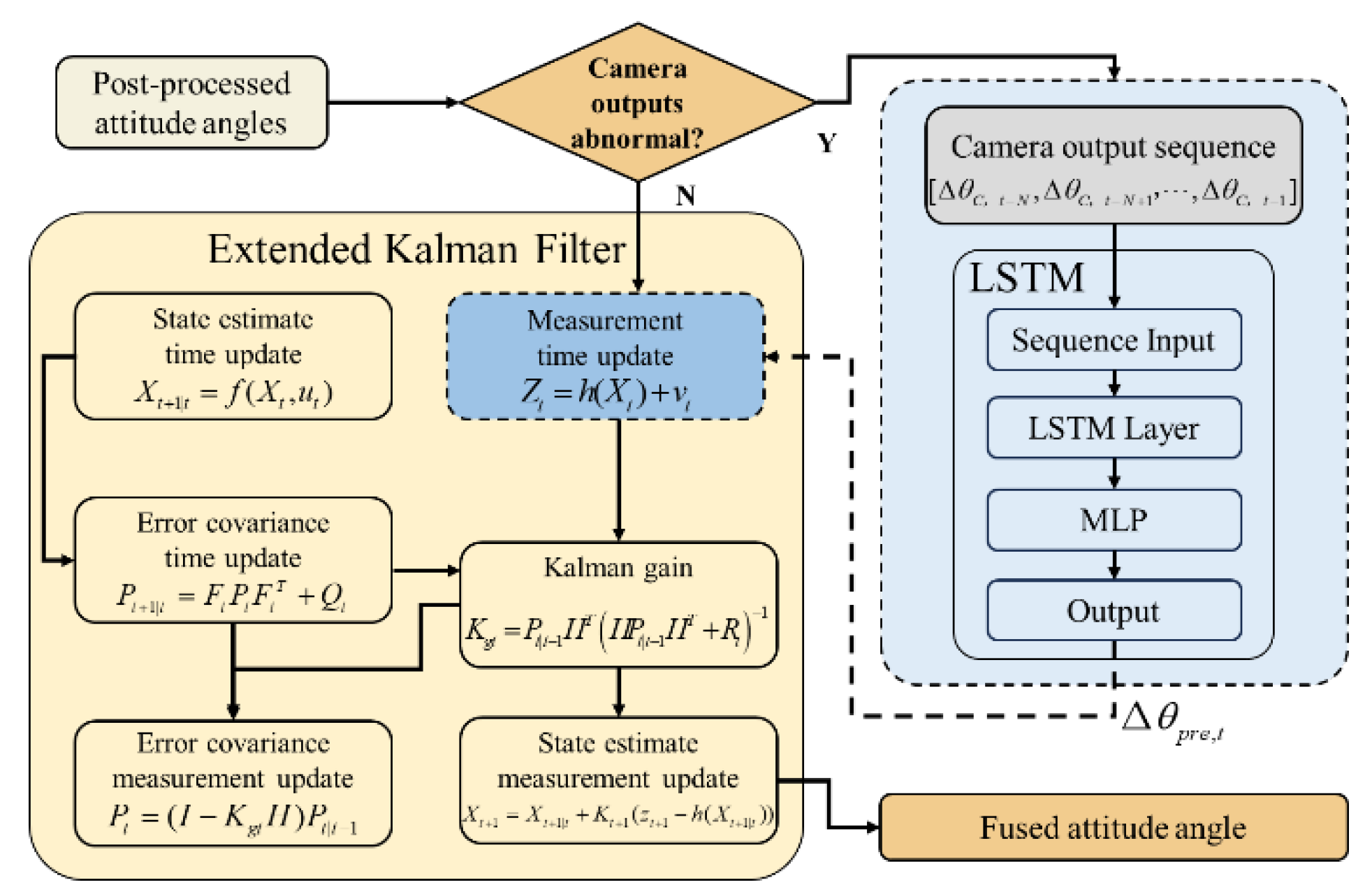

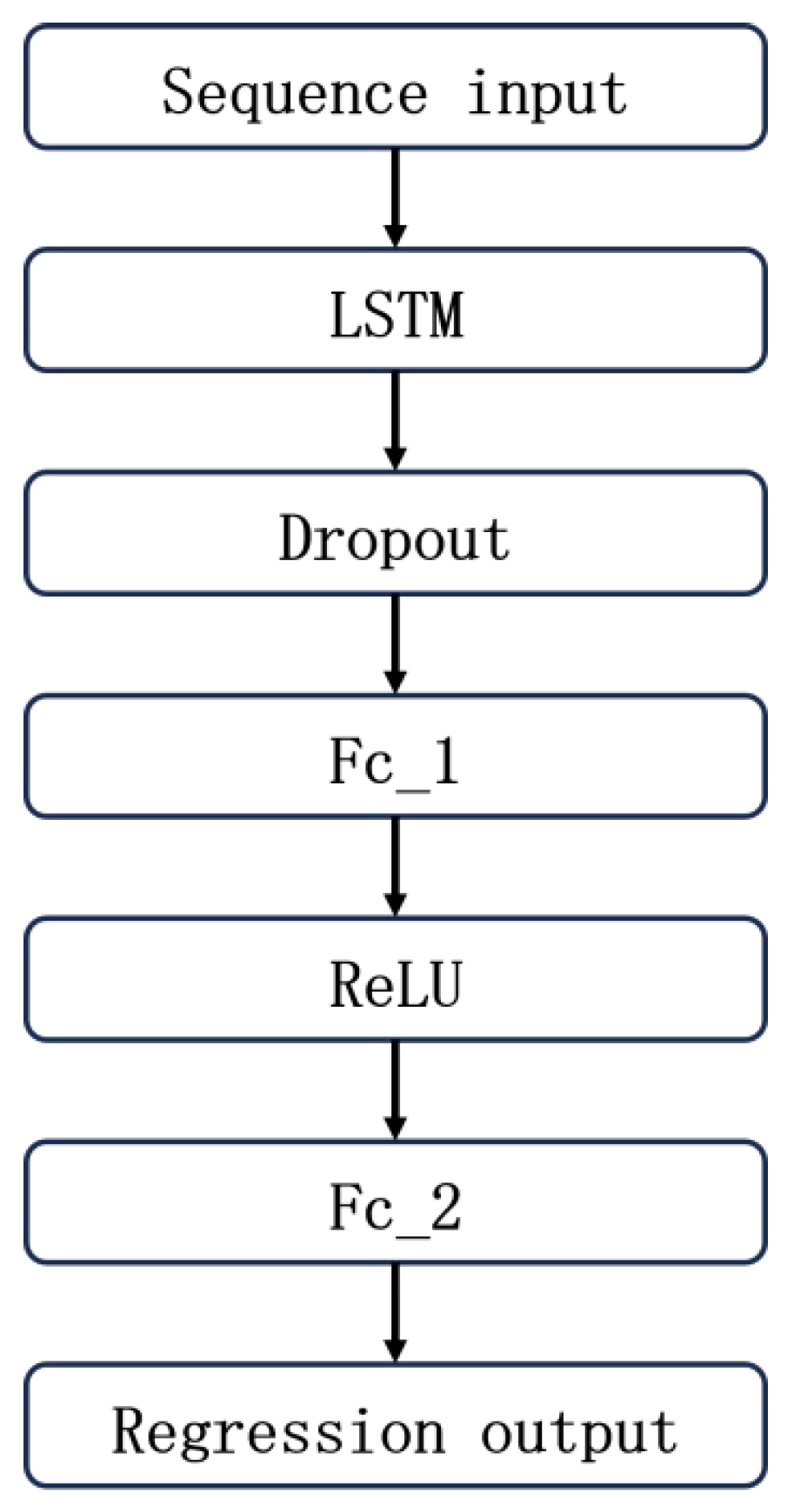

2.2. Algorithm Design By LSTM-enhanced Extended Kalman Filter

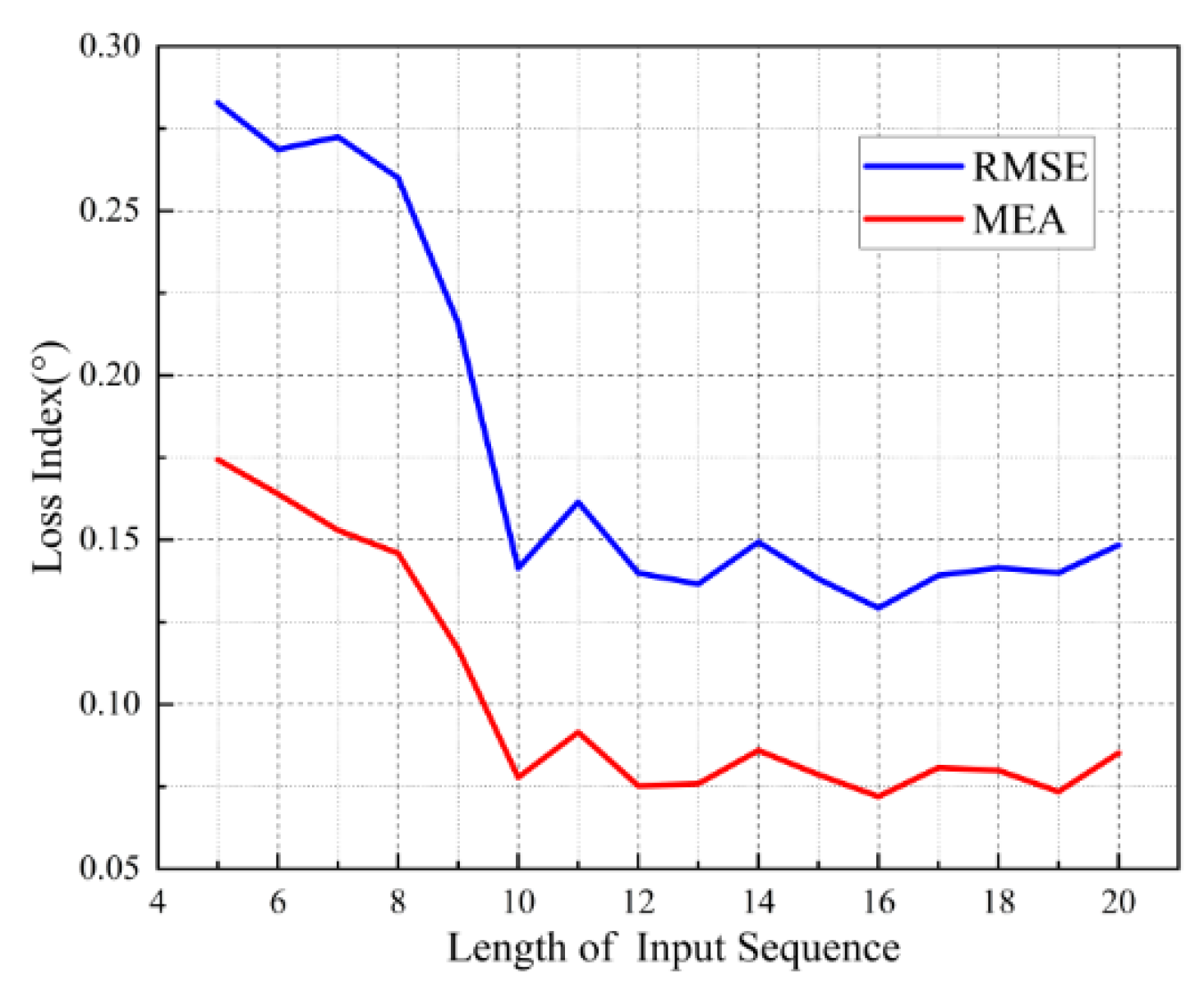

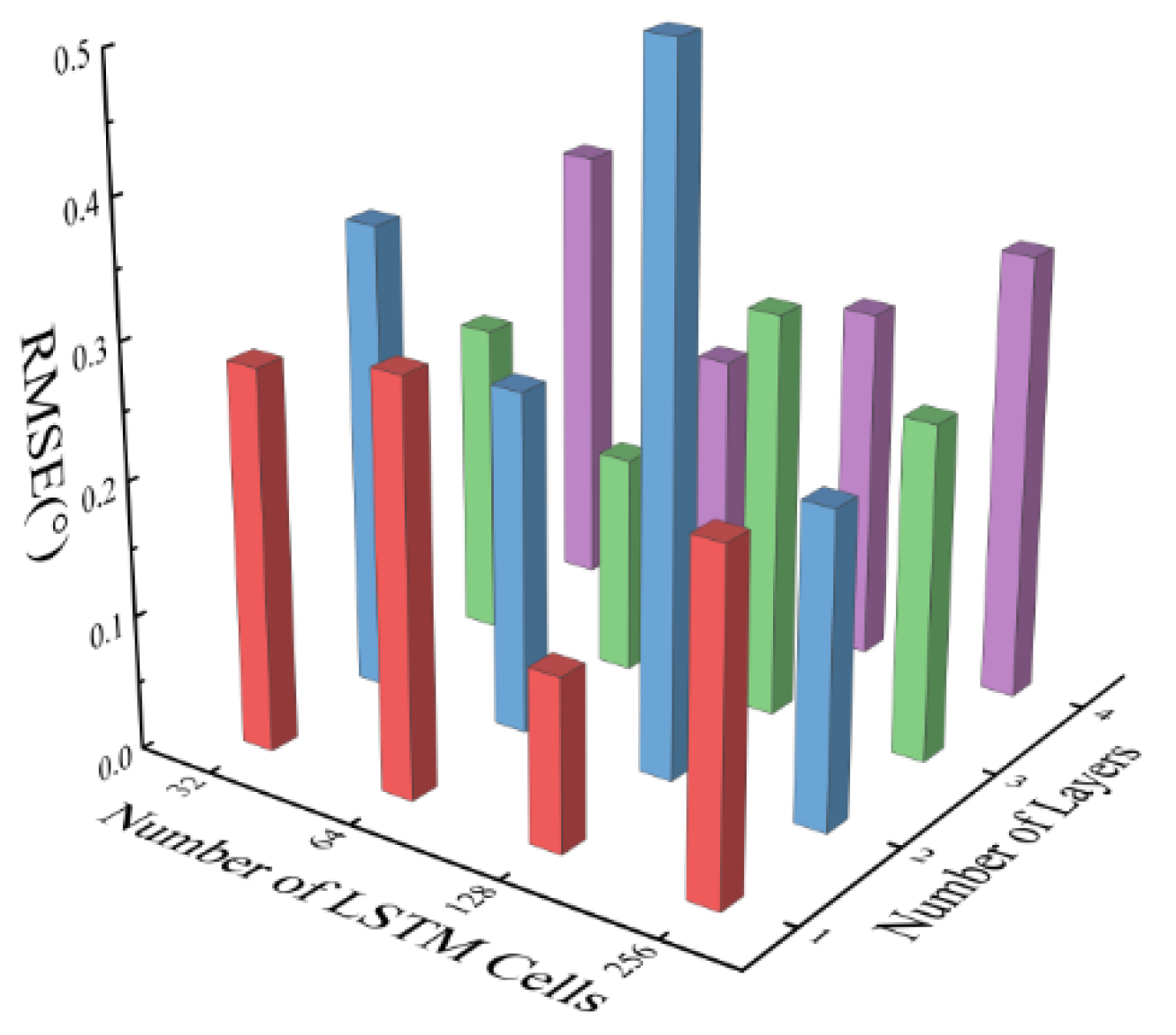

3. Training Parameter Settings and Simulation

3.1. Dataset Construction and Network Structure Design

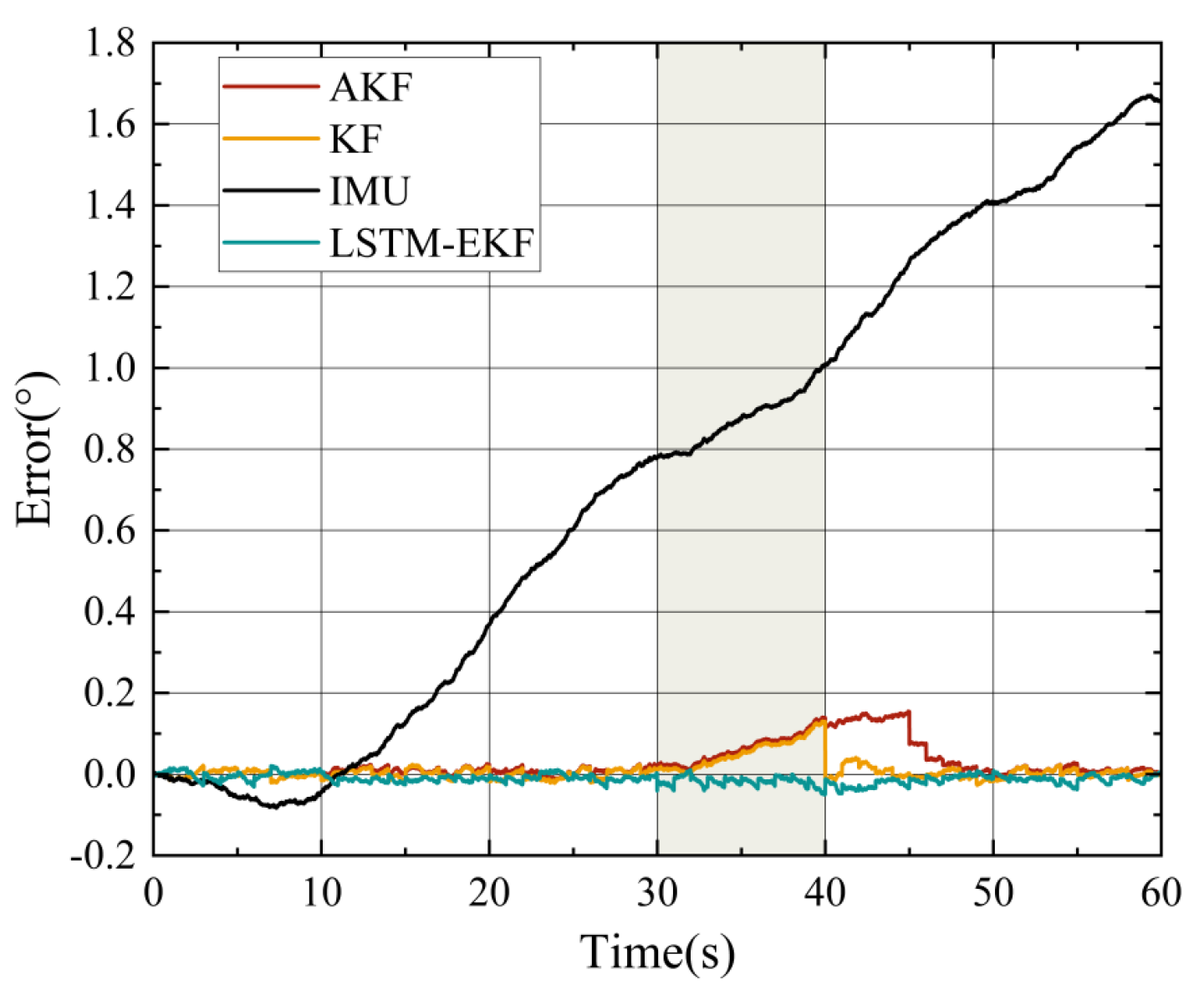

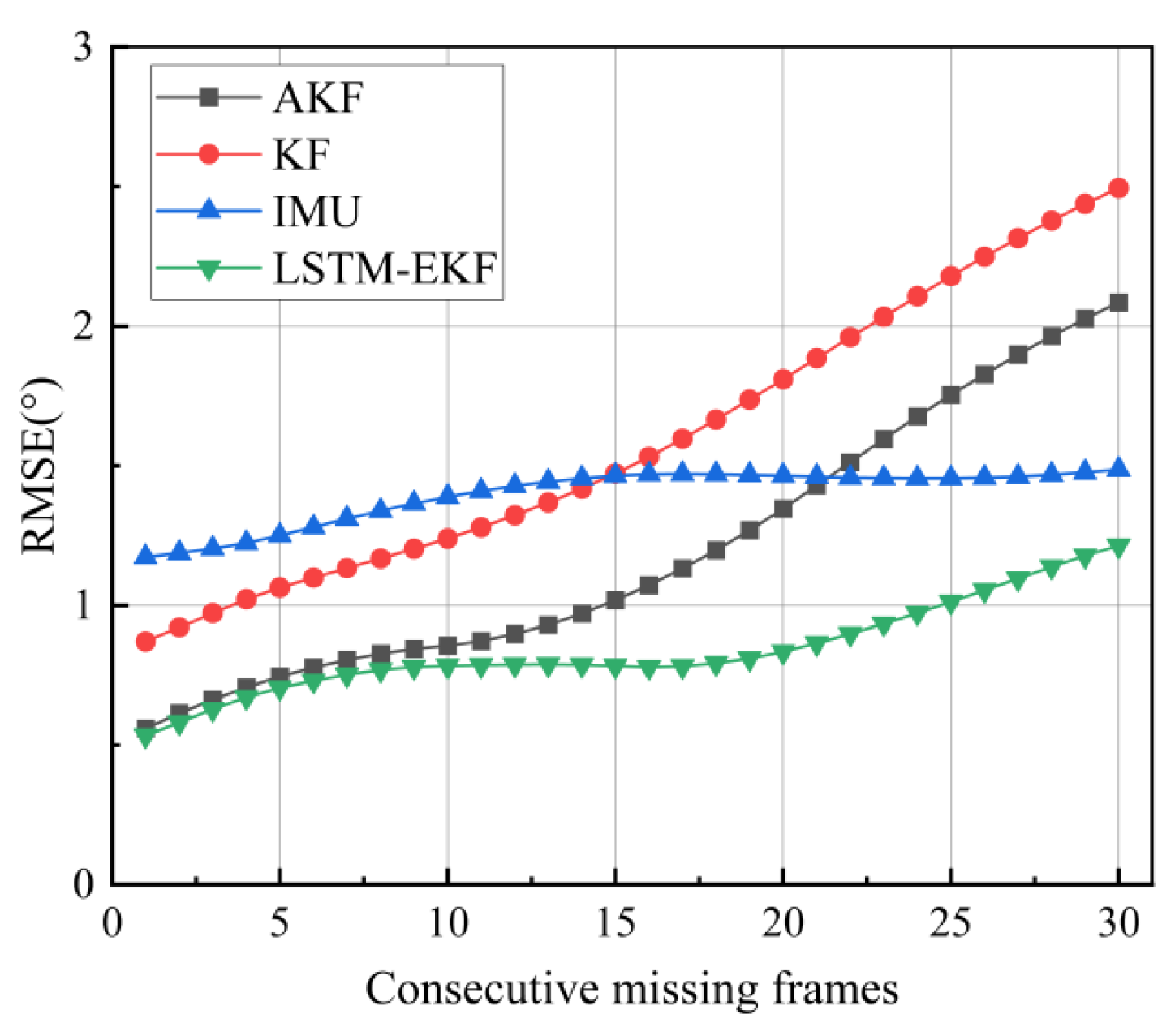

3.2. Performance Simulation Analysis of Fusion Algorithms

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Platform

4.2. Design of Experiments

- Long-Term Reciprocating Rotation Experiment:

- 2.

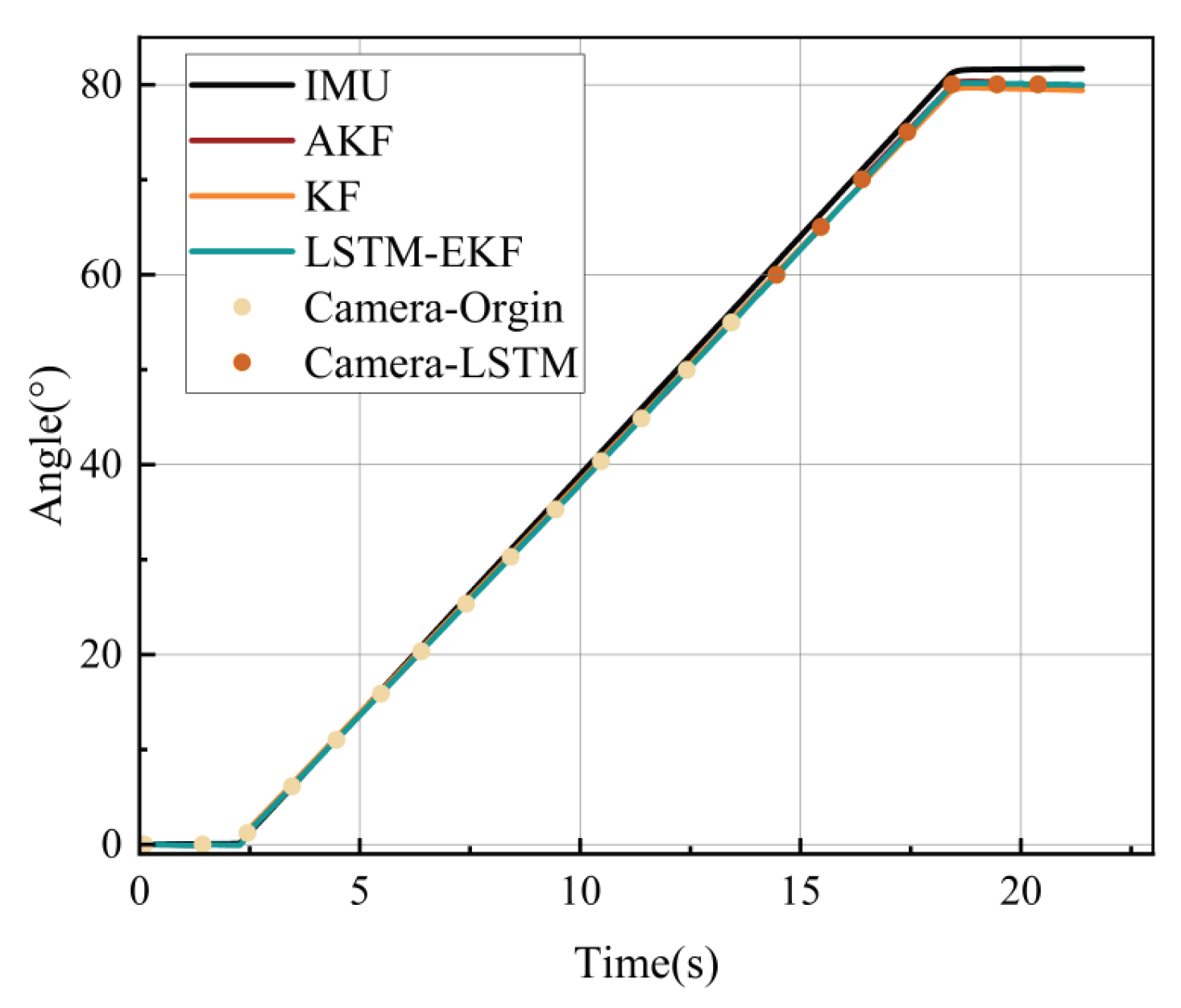

- Camera Occlusion Scanning Experiment:

- 3.

- Attitude Accuracy Evaluation Experiment:

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

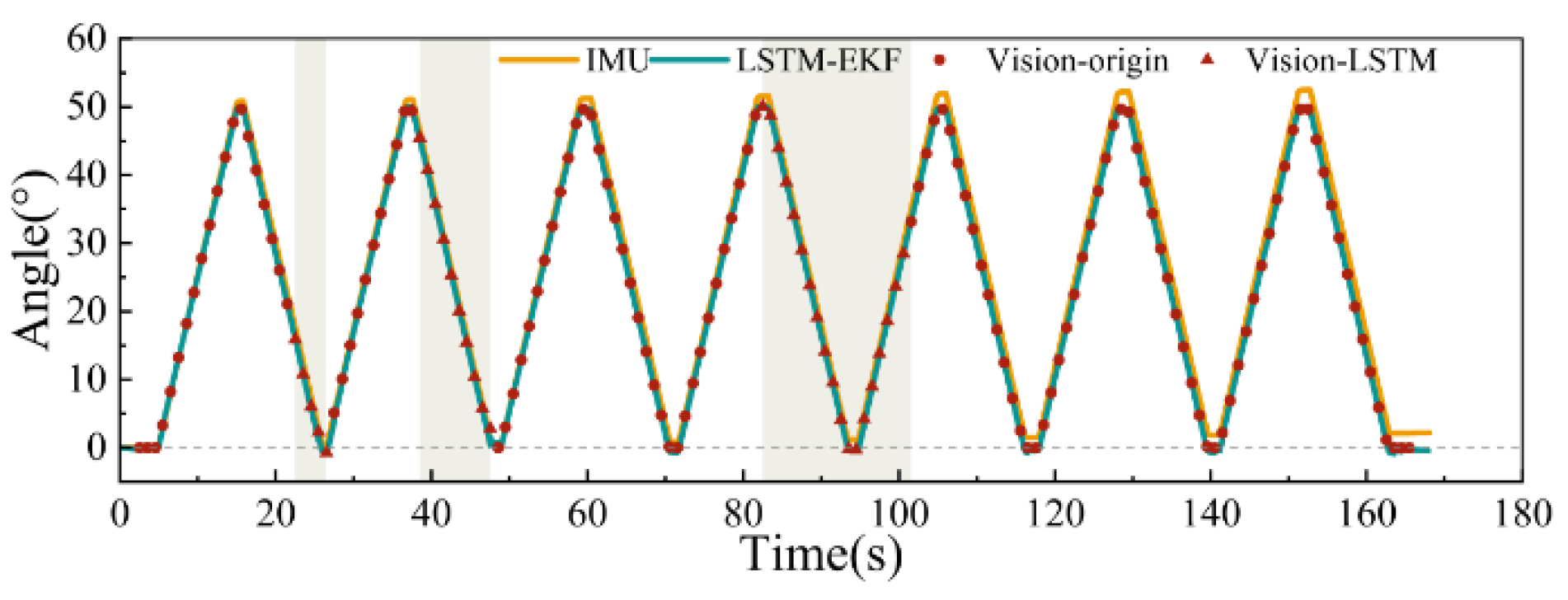

- Long-Term Reciprocating Rotation Experiment:

- 2.

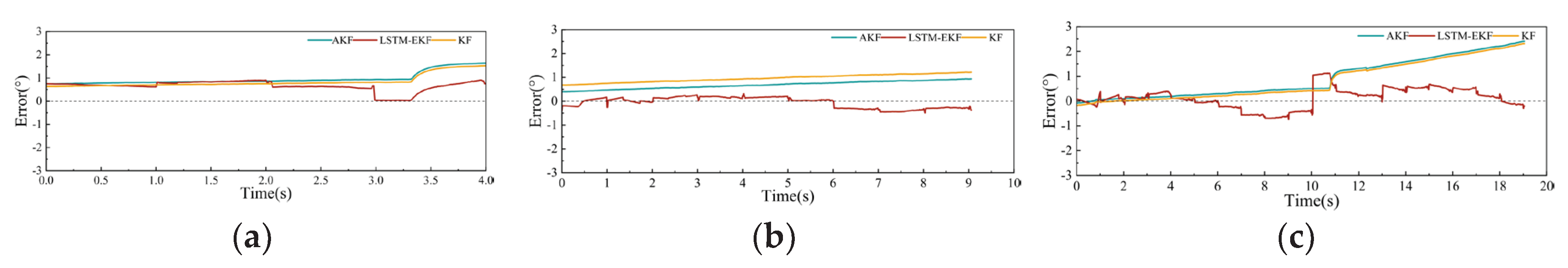

- Camera Occlusion Scanning Experiment:

- 3.

- Attitude Accuracy Evaluation Experiment:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| LSTM-EKF | LSTM-enhanced Extended Kalman Filter |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| AKF | Adaptive Kalman Filter |

| AEKF | Adaptive Extended Kalman Filter |

| KF | Kalman Filtering |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman Filter |

| BP | Back Propagation |

| EPNP | Efficient Perspective-n-Point |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ReUL | Rectified Linear Unit |

| ME | Mean Error |

References

- Liu, Y; Zhou, J; Li, Y; Zhang, Y; He, Y; Wang, J. A high-accuracy pose measurement system for robotic automated assembly in large-scale space. Measurement 2022, vol. 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A. Vision and IMU Data Fusion: Closed-Form Solutions for Attitude, Speed, Absolute Scale, and Bias Determination. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2012, vol. 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Sun, L. Huang, P. Wang, and X. Guo, Fused Pose Measurement Algorithm Based on Double IMU and Vision Relative to a Moving Platform. Chinese Journal of Sensors and Actuators 2018, vol. 31(no. 9), 1365–1372.

- Yan, K.; Xiong, Z.; Lao, D.B.; Zhou, W.H.; Zhang, L.G.; Xia, Z.P.; Chen, T. Attitude measurement method based on 2DPSD and monocular vision. In Proceedings of the Applied Optics and Photonics China (2019), Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Xiong et al., A laser tracking attitude dynamic measurement method based on real-time calibration and AEKF with a multi-factor influence analysis model. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, vol. 36(no. 2). [CrossRef]

- Khodarahmi, M; Maihami, V. A Review on Kalman Filter Models. In Arch. Comput. Methods Eng.; 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, X. Adaptive robust Kalman filtering for precise point positioning. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, vol. 25(no. 10), 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, K.; Gunther, S.; Yaz, E.; Unbehauen, R. Stochastic Stability of the Discrete-Time Extended Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1999, vol. 44(no. 4), 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T. N.; Khenchaf, A.; Comblet, F.; Franck, P.; Champeyroux, J. M.; Reichert, O. Robust-Extended Kalman Filter and Long Short-Term Memory Combination to Enhance the Quality of Single Point Positioning. Appl. Sci.-Basel 2020, vol. 10(no. 12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhao et al.; Large-Space Laser Tracking Attitude Combination Measurement Using Backpropagation Algorithm Based on Neighborhood Search. Appl. Sci. 2025, vol. 15(no. 3). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ye, G.; Yang, P.; et al. Application of multi-sensor fusion localization algorithm based on recurrent neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, vol. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X. Y.; Yang, G. H. Secure State Estimation for Train-to-Train Communication Systems: A Neural Network-Aided Robust EKF Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, vol. 71(no. 10), 13092–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. S; Wu, Y. F; Kao, M. C. Inertial Sensor Error Compensation for Global Positioning System Signal Blocking “Extended Kalman Filter vs Long- and Short-term Memory”. Sensors and materials: An International Journal on Sensor Technology 2022, vol. 34, pp:2427–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent; Lepetit; Francesc; et al. EPnP: An Accurate O(n) Solution to the PnP Problem. International Journal of Computer Vision 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y; Zhang, Y; Li, Z; et al. IMU/UWB Fusion Method Using a Complementary Filter and a Kalman Filter for Hybrid Upper Limb Motion Estimation[J]. Sensors (14248220) 2023, 23(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensor | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|

| IMU | Gyroscope bias | 0.01°/h |

| Angular velocity random walk | ||

| Sampling interval | 0.01s | |

| Camera | Measurement bias | 0.01° |

| Sampling interval | 1s |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Input dimensions | 3×16 |

| Number of LSTM layers | 1 |

| Number of LSTM layer cells | 64 |

| Dataset size | 2400 |

| Initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| Learning rate decay interval | 100 |

| Learning rate decay factor | 0.1 |

| L2 regularization coefficient | 0.01 |

| Parameters | KF/° | AKF/° | LSTM-EKF/° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole | MAE | 0.490 | 0.535 | 0.396 |

| RMSE | 0.668 | 0.698 | 0.469 | |

| ME | 0.418 | 0.518 | 0.294 | |

| Vision Loss | MAE | 0.864 | 0.848 | 0.344 |

| RMSE | 1.054 | 1.049 | 0.428 | |

| ME | 0.856 | 0.845 | 0.121 | |

| Reference angle | IMU/° | LSTM-EKF/° | AKF/° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within visual range | 0 | 0.122 | 0.051 | 0.077 |

| 5 | 0.173 | 0.091 | 0.106 | |

| 10 | 0.213 | 0.104 | 0.152 | |

| 15 | 0.226 | 0.117 | 0.186 | |

| 20 | 0.276 | 0.128 | 0.191 | |

| 25 | 0.290 | 0.136 | 0.221 | |

| 30 | 0.374 | 0.157 | 0.233 | |

| 35 | 0.407 | 0.160 | 0.248 | |

| 40 | 0.526 | 0.157 | 0.225 | |

| 45 | 0.628 | 0.150 | 0.220 | |

| 50 | 0.720 | 0.151 | 0.284 | |

| 55 | 0.779 | 0.182 | 0.267 | |

| Out of visual range | 60 | 0.812 | 0.204 | 0.342 |

| 65 | 0.848 | 0.221 | 0.352 | |

| 70 | 0.858 | 0.236 | 0.379 | |

| 75 | 0.883 | 0.255 | 0.334 | |

| 80 | 1.001 | 0.264 | 0.384 | |

| Algorithm | Experiment 1/° | Experiment 2/° | Experiment 3/° |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM-EKF | 0.463 | 0.753 | 0.14 |

| Only EKF | 0.972 | 0.964 | 0.258 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.