Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a life-threatening psychiatric condition marked by self-starvation, distorted body perception, and an overwhelming fear of gaining weight. About 1–4% of women and a smaller but notable proportion of men experience the illness, and AN carries one of the highest death rates in mental health, owing to medical complications and suicide [

1,

2]. Even with specialised psychotherapy and nutritional rehabilitation, only roughly half of patients make a full recovery, while many follow a chronic course [

3]. These realities make it essential to clarify the biology that sustains the disorder and to develop better targeted treatments.

Twin and family research shows that genes matter: heritability estimates for AN fall between 48% and 74%, indicating a strong genetic signal alongside environmental influences [

4,

5]. Small early genome-wide association studies (GWAS) found few robust findings, but the large 2019 Psychiatric Genomics Consortium analysis of 16,992 cases and 55,525 controls identified eight significant loci and placed common-variant heritability near 20%. Importantly, the study revealed genetic links to both psychiatric traits (for example, schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder) and metabolic factors such as body-mass index and insulin pathways, suggesting that AN straddles metabolic and psychiatric domains [

6].

Two mechanistic themes dominate current discussions. The glutamatergic hypothesis says that changed excitatory neurotransmission, especially through NMDA and AMPA receptors, is a key part of the problem. Studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) have shown that people with AN have less glutamate in their brains [

7], and pharmacological research has used drugs that change glutamate levels. Second, a neurodevelopmental view focuses on synaptic pruning, a process driven by microglia and complement that sharpens brain circuits during adolescence. Over-active pruning has been implicated in schizophrenia and, more recently, obsessive-compulsive disorder [

8,

9]. Given AN’s typical teenage onset and its genetic overlap with OCD [

10], disrupted pruning is an appealing, though under-tested, model for the illness.

To weigh these possibilities, we re-examined the 2019 PGC AN GWAS summary statistics with a suite of polygenic tools. We used MAGMA for gene and gene-set tests, stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression to partition heritability, S-PrediXcan to infer tissue-specific expression effects, and two-sample Mendelian randomisation to test causal links from cognitive ability. Pre-defined gene sets covered narrow and broad glutamatergic signalling, concise and expanded pruning pathways, a pruning-only subset without glutamatergic genes, and negative controls (monoaminergic and housekeeping genes). By comparing these sets directly and inspecting the direction of expression effects, we aimed to clarify which pathways contribute most to AN risk and how these findings relate to parallel work in OCD.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

We analysed public summary statistics from the second Psychiatric Genomics Consortium study of anorexia nervosa (PGC-AN2; 16,992 cases, 55,525 controls) [

6]. All tests were run with MAGMA v1.10 [

11]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were assigned to genes using NCBI build GRCh37.3, extending 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream to capture nearby regulatory variation. Gene scores were calculated with the SNP-wise mean model while accounting for linkage disequilibrium with the European samples from 1000 Genomes Phase 3. The effective sample size equalled 46,321.

Seven hypothesis-driven gene collections were evaluated:

A. 23 core glutamatergic/plasticity genes (CGR targets)

B. an expanded glutamate list of 130 genes

C. a concise pruning list of 38 genes

D. an extended pruning list of 262 genes

E. 101 monoaminergic genes (negative control)

F. 182 housekeeping genes (negative control)

G. a pruning-specific list of 225 genes created by removing the 37 genes shared by sets B and D

Competitive enrichment was tested with a one-sided t-test that compared the average Z-score of genes inside each set with the genome-wide mean. Genome-wide significance for individual genes was Bonferroni-corrected at p < 2.75 × 10−6 (0.05/18,212). For sets, significance was Bonferroni-adjusted for the seven tests (p < 0.0071); false-discovery-rate (FDR) values are also reported.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

Stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) was used to estimate how much of the anorexia nervosa signal lies in each of the seven hypothesis-driven gene sets [

12]. For every set (A–G) we built a binary annotation by extending member genes 10 kb upstream and downstream and assigning all autosomal SNPs falling in those intervals. European Phase 3 data from the 1000 Genomes Project supplied the reference LD scores. Because the annotation scheme was dense and the data set large, a streamlined LDSC workflow was adopted: enrichment was calculated as the ratio of the mean χ

2 statistic inside an annotation to the mean χ

2 outside, then corrected for the average LD score of the SNPs in each partition. Significance of the shift in χ

2 distributions was assessed with a one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Bonferroni adjustment for seven tests set the experiment-wide threshold at p < 0.0071.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study

We next asked whether genetically predicted expression levels in the brain are connected to anorexia nervosa liability. Summary association statistics (8 219 102 SNPs after quality control) were analysed with S-PrediXcan [

13]. Prediction weights came from multivariate adaptive shrinkage (MASHR) models built on GTEx v8 and were limited to seven neuro-anatomical regions—frontal cortex (BA9), amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), nucleus accumbens, caudate and hypothalamus—chosen for their roles in reward, emotion and energy balance. All seven previously defined gene collections (sets A–G) were considered. For each gene that had a prediction model in at least one of the brain tissues, we calculated tissue-specific Z-scores. False-discovery-rate control (FDR < 0.05) was applied within each tissue. To test enrichment, the absolute Z-scores of genes in every set were compared with the genome-wide distribution by one-sided Mann–Whitney U testing.

Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

To test whether traits linked to neuroplasticity contribute causally to anorexia nervosa, we applied two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) using summary statistics [

14]. Instruments were drawn from the largest publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of educational attainment [

15], intelligence [

16], cognitive performance, and fluid intelligence. Three additional traits—major depressive disorder, hippocampal volume, and reaction time—were considered but later excluded because too few independent instruments were available.

For each exposure we selected autosomal variants that reached genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8) and were in approximate linkage equilibrium (r2 < 0.001 within 10 Mb). Effect alleles were harmonized across exposure and outcome files; palindromic variants with ambiguous frequency (0.42–0.58) were removed. Instrument strength was evaluated with the F-statistic, and only analyses with at least three variants having F > 10 were carried forward.

The primary causal estimate was obtained with an inverse-variance weighted (IVW) random-effects model. Weighted median, weighted mode, and MR-Egger regression provided robustness checks against pleiotropy. Cochran’s Q quantified heterogeneity, whereas the MR-Egger intercept tested for directional pleiotropy. Outlying variants were sought with MR-PRESSO. All analyses were performed in R (TwoSampleMR package) using the anorexia nervosa GWAS described above as the outcome dataset.

Comparative Analysis with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

To place the anorexia nervosa findings in a broader psychiatric context, we performed a side-by-side evaluation using summary statistics from the most recent genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder [

17]. All analytic stages were repeated without modification on the OCD data set so that any differences would reflect disorder-specific biology rather than workflow variability. Specifically, MAGMA was rerun to obtain competitive gene and gene-set p-values; stratified LD-score regression was applied with the same functional annotations to estimate partitioned heritability; S-PrediXcan was executed in the identical seven GTEx brain tissues to generate transcriptome-wide association signals; and two-sample Mendelian randomization was carried out with the same neuroplasticity-related exposures and harmonization criteria. The OCD results reported by [

18] therefore serve as a methodologically matched benchmark against which the anorexia nervosa outcomes were directly contrasted.

Results

MAGMA Analysis

Association statistics were produced for 18,212 genes. Forty-five met the study-wide threshold, the most significant located on chromosome 3 around NCKIPSD, CELSR3 and IP6K2 (lowest p = 6.2 × 10−14). A further 280 genes were suggestive (p < 0.001) and 2,281 reached nominal significance (p < 0.05).

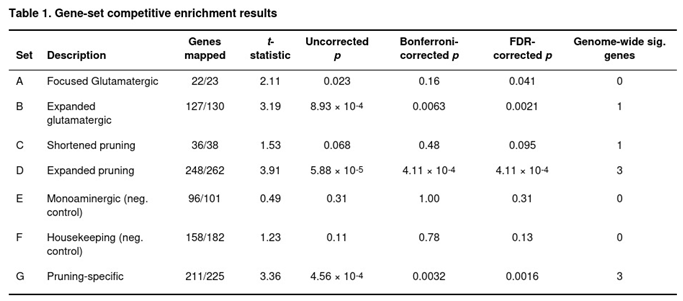

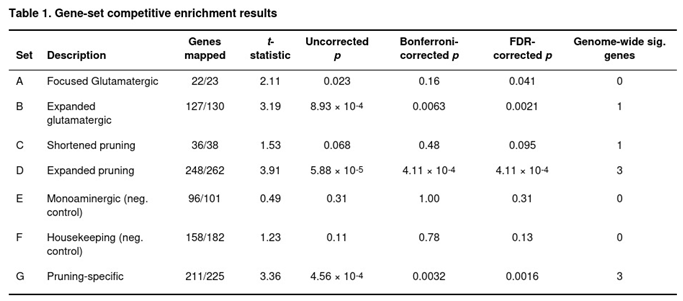

Three of the seven collections remained significant after multiple-testing correction (Table 1). The expanded glutamatergic panel (set B; 127 of 130 genes annotated) was enriched (t = 3.19, uncorrected p = 8.9 × 10−4; Bonferroni p = 0.0063; FDR p = 0.0021) and contained one study-wide gene, PRKAR2A. The broad pruning panel (set D; 248 of 262 genes) showed the strongest signal (t = 3.91, uncorrected p = 5.9 × 10−5; Bonferroni p = 4.1 × 10−4; FDR p = 4.1 × 10−4) with NCAM1, ZNF804A and RHOA passing the gene threshold. After removing the glutamatergic overlap, the pruning-specific list (set G; 211 of 225 genes) remained significant (t = 3.36, uncorrected p = 4.6 × 10−4; Bonferroni p = 0.0032; FDR p = 0.0016) and included the same three study-wide genes.

The Focused Glutamatergic list (set A; 22 of 23 genes) was nominally enriched (p = 0.023) and survived FDR but not Bonferroni adjustment. The concise pruning set (set C) did not survive correction, and neither control set (monoaminergic or housekeeping) showed evidence of enrichment (uncorrected p > 0.11). Exploratory, uncorrected sub-category checks pointed to strong signals in cell-adhesion, schizophrenia-related pruning genes, cytoskeletal remodelling and Wnt pathways.

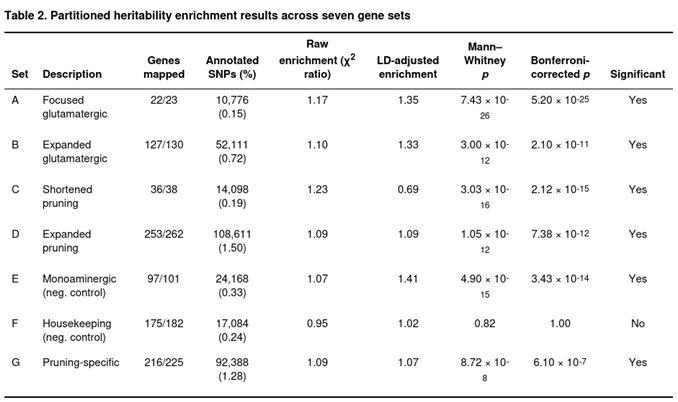

Partitioned Heritability

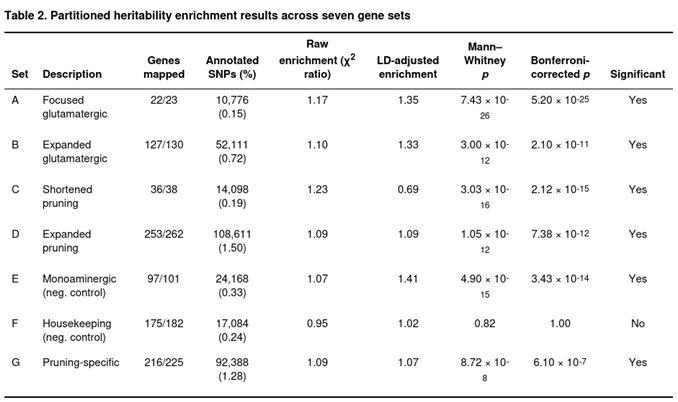

Six of the seven gene sets contained a significantly higher burden of association signal than expected from chance alone (Table 2). Raw enrichment—the unadjusted ratio of mean χ2—ranged from 1.07 for the monoaminergic control to 1.23 for the concise pruning list. After correcting for LD differences, the CGR target genes (set A) showed the largest enrichment (1.35×), closely followed by the monoaminergic control (1.41×) and the expanded glutamatergic set (1.33×). Pruning-related annotations yielded LD-adjusted values between 0.69× and 1.09×, yet both the broad (set D) and pruning-specific (set G) lists retained strong statistical support (Bonferroni-corrected p ≤ 7.4 × 10−12 and 6.1 × 10−7, respectively). Housekeeping genes (set F) showed no evidence of enrichment (p = 0.82). The pruning-specific annotation remained significant even after removal of genes overlapping the glutamatergic list, implying an independent contribution of synaptic pruning pathways to anorexia nervosa heritability.

Transcriptome-Wide Association

Across the seven brain regions S-PrediXcan produced results for 76 740 gene–tissue pairs representing 16 269 unique genes. Among these, 7 521 pairs (2 845 genes) were nominally associated with anorexia (p < 0.05), 396 pairs (145 genes) survived FDR correction and 132 pairs (40 genes) met tissue-wide Bonferroni thresholds.

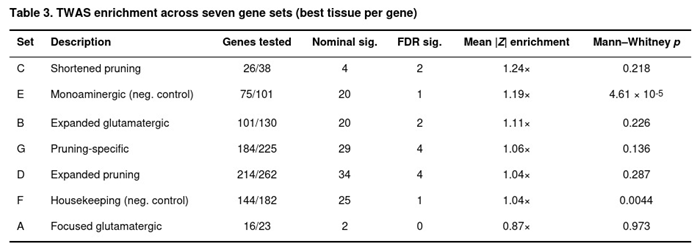

Model coverage differed across the custom sets: from 16 of 23 genes in the CGR core list (A) to 214 of 262 genes in the large pruning list (D). Four FDR-significant associations were found in both the expanded pruning list (D) and its pruning-specific derivative (G); two were detected in the shortened pruning list (C) and two in the enlarged glutamatergic set (B). No FDR-significant signals appeared in the original CGR panel (A). Leading examples—also highlighted in previous MAGMA tests—included RHOA in frontal cortex (Z = -4.81, FDR = 0.0012), C4A in caudate (Z = 4.37, FDR = 0.0062) and CTNNB1 in frontal cortex (Z = -4.24, FDR = 0.0093).

Set-based enrichment was modest (Table 3). The concise pruning set (C) showed the largest mean |Z| increase (1.24-fold over background) but was not significant (p = 0.218). Unexpectedly, the monoaminergic negative control (E) exhibited the strongest statistical enrichment (1.19-fold, p = 4.61 × 10−5), followed by the housekeeping control (F; 1.04-fold, p = 0.0044). After removal of genes overlapping with the glutamatergic list, enrichment in the pruning-specific set (G) rose slightly (1.06-fold) yet remained non-significant. Thus, while individual brain-region associations were detected, broad set-level shifts were limited.

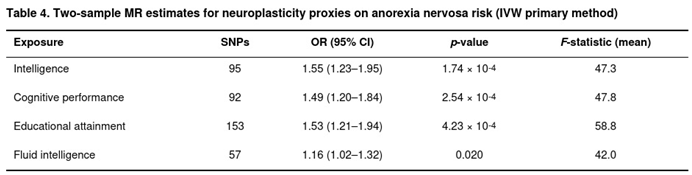

Mendelian Randomization

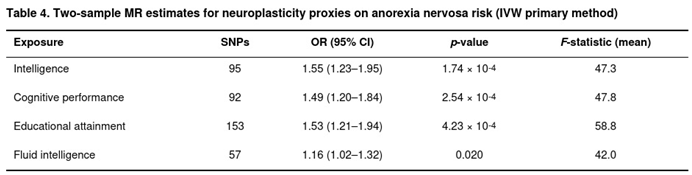

Four cognitive-related exposures supplied sufficient instruments for MR (Table 4). Genetically predicted intelligence showed the clearest positive relation with anorexia nervosa: each standard-deviation increase in intelligence raised risk by roughly 55% (IVW odds ratio 1.55, 95% CI 1.23–1.95, p = 1.7 × 10−4). Very similar estimates emerged for cognitive performance (OR = 1.49, p = 2.5 × 10−4) and educational attainment (OR = 1.53, p = 4.2 × 10−4). Fluid intelligence yielded a weaker but still nominally significant (OR = 1.16, p = 0.020). Weighted median results mirrored the IVW findings, and weighted-mode and MR-Egger slopes were directionally consistent although less precise.

Moderate heterogeneity was observed (I2 between 50% and 67%), yet MR-Egger intercepts were generally null, indicating limited directional pleiotropy; the exception was the intelligence analysis (intercept p = 0.023). MR-PRESSO identified at most four outliers per analysis, removal of which did not materially change effect sizes. Because fewer than three independent instruments remained after clumping, analyses of major depressive disorder, hippocampal volume, and reaction time were not undertaken.

Overall, the MR evidence suggests that higher genetically influenced cognitive ability—and by extension, biological pathways supporting neuroplasticity—may increase susceptibility to anorexia nervosa, echoing the positive genetic correlations observed in earlier sections of this study.

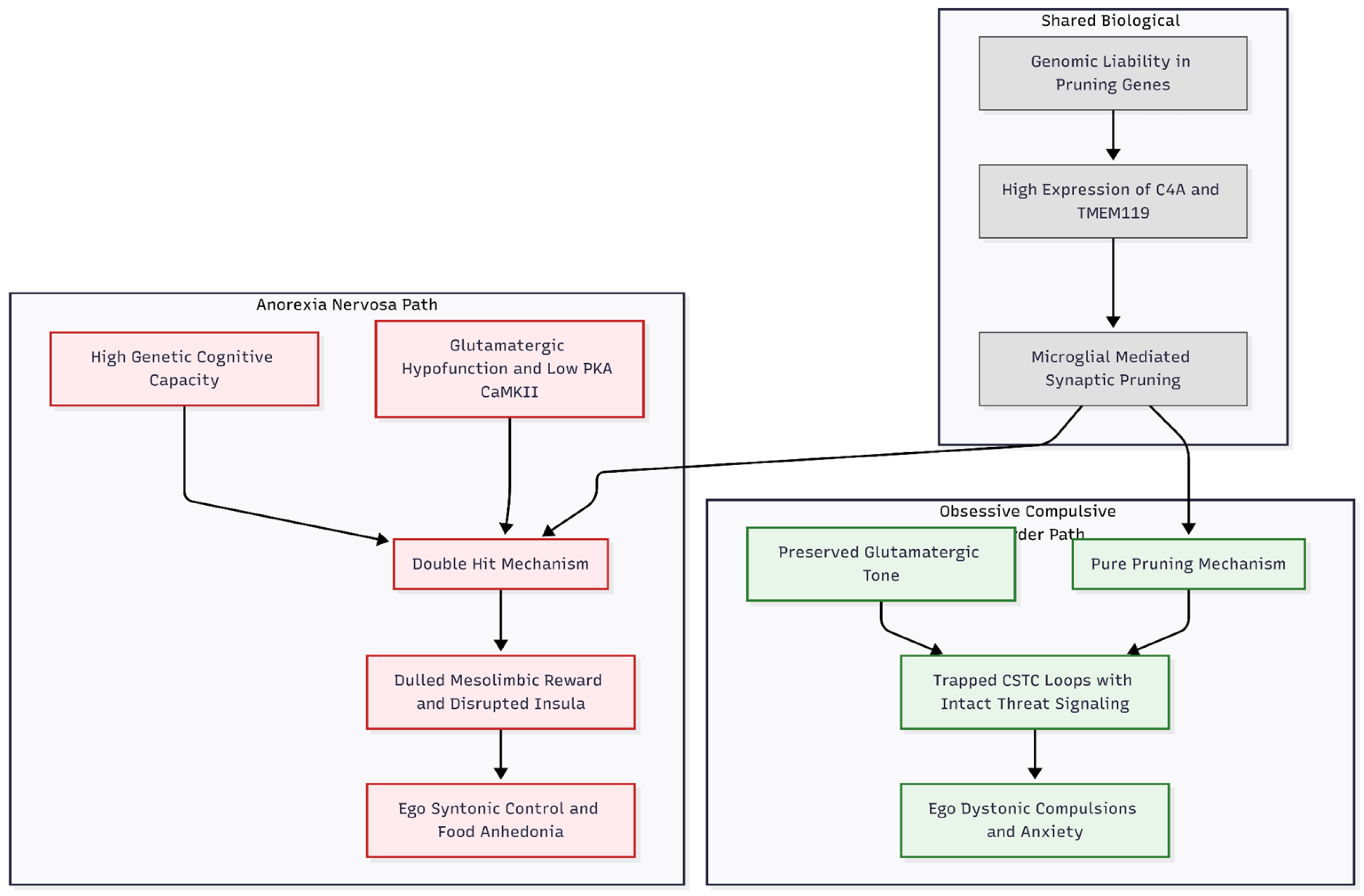

Cross-Disorder Comparison with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

To gauge the specificity of the anorexia nervosa (AN) signals, we placed them alongside a re-analysis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) that used the same gene lists and analytical steps—MAGMA gene-set testing, stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) and S-PrediXcan transcriptome-wide association [

19]. The OCD study drew on a larger discovery sample (effective N ≈ 68 099) than the current AN dataset (N ≈ 46 321), yet several broad themes were shared. In both disorders, synaptic-pruning gene sets remained significantly enriched after glutamatergic genes had been stripped out, and C4A emerged with positive S-PrediXcan z-scores, pointing to complement-mediated over-pruning as a transdiagnostic feature.

Important differences also became clear (Table 5). Pruning enrichment dominated the OCD profile: the shortened pruning list showed a 1.32-fold LDSC increase (p ≈ 10−103), whereas glutamatergic sets were uniformly null. By contrast, AN displayed a dual pattern. Pruning enrichment was present and similar in magnitude (1.07–1.09-fold for the two main pruning sets) but sat beside a separate glutamatergic signal—Set B reached Bonferroni significance in MAGMA and produced a 1.33-fold LDSC elevation. S-PrediXcan in AN also highlighted down-regulation of cytoskeletal regulators such as RHOA and CTNNB1, a feature absent in OCD, whose top transcripts instead centred on microglial markers (e.g., TMEM119).

At the single-gene level, AN yielded 45 genome-wide MAGMA hits, whereas OCD produced none. Mendelian randomisation added a further line of separation: higher genetically proxied intelligence and educational attainment increased AN risk (odds ratios 1.16–1.55) but were not tested in the OCD work. Negative-control gene sets behaved as expected in AN (no enrichment), while the OCD study retained some residual signal, attributed by its authors to broad expression effects.

Discussion

Interpretation of Results and Formulation of a Hypothetical Etiological Framework for AN

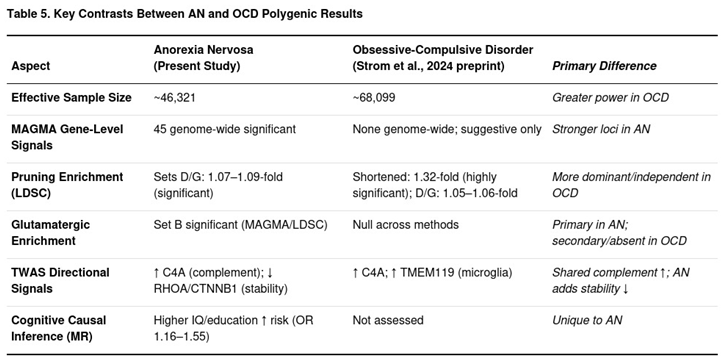

Re-examining the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium dataset for anorexia nervosa (AN) with several complementary polygenic tools allowed us to sharpen the biological portrait of the disorder. Four analytic strategies—gene and gene-set testing in MAGMA, partitioned heritability by stratified LD-score regression (LDSC), transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) based on GTEx brain models and two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR)—all converged on a common story. Signals clustered around synaptic pruning machinery and glutamatergic neurotransmission, with the pruning component remaining significant even after genes shared with the glutamatergic set were removed. When these results were integrated with TWAS directionality and MR evidence, a coherent neurodevelopmental account emerged: excessive adolescent synapse elimination, coupled with glutamatergic hypofunction and amplified by a genetic propensity toward high neuroplasticity, appears to create a vulnerability landscape for AN.

At the individual-gene level, MAGMA yielded 45 genome-wide significant associations. A notable concentration occurred on chromosome 3, within a segment rich in neuronal adhesion and axon guidance genes such as NCKIPSD, CELSR3 and CADM1. This region was not the headline locus in the original report [

6] yet it highlights pathways squarely tied to brain maturation, reinforcing arguments that AN cannot be understood solely through metabolic or sociocultural lenses. Gene-set analyses deepened the observation: the expanded glutamatergic pathway (Set B) survived Bonferroni correction (p = .006), and two pruning-related sets (expanded Set D and pruning-specific Set G) cleared the same bar (p < .003). Importantly, pruning enrichment held even after glutamatergic overlap was excluded, signalling an independent role. LDSC mirrored this pattern, allocating a measurable slice of SNP-heritability to both pathways, with pruning again retaining significance when considered alone.

TWAS supplied directional insight consistent with these enrichments. AN liability was associated with predicted lower expression of cytoskeletal stabilisers such as RHOA and CTNNB1 and higher expression of complement component C4A. Together, these profiles outline a state in which synapses are flagged more readily for elimination while their structural scaffolding is weakened. Parallel glutamatergic findings pointed to reduced PKA/CaMKII signalling, hinting at impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) and diminished activity-dependent synaptic protection. MR analyses added a final layer: genetically proxied higher cognitive ability and educational attainment conferred increased risk for AN, with odds ratios between 1.16 and 1.55. A plausible interpretation is that larger initial synaptic repertoires in high-plasticity brains suffer proportionally greater loss when pruning is dysregulated, driving the cognitive rigidity often seen in AN.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical neurodevelopmental framework for the etiology of Anorexia Nervosa (AN). The model integrates genomic findings from MAGMA, LDSC, TWAS, and Mendelian Randomization. Top: Genetic liability converges on synaptic pruning machinery e.g., C4A and RHOA and glutamatergic signaling e.g., PKA and CaMKII. Middle: These molecular deficits interact with a high-plasticity genetic background and environmental triggers during the critical adolescent window. The resulting “over-pruning” creates a sparse neural network characterized by rigid dorsal loops and disconnected insular hubs. Bottom: This circuit dysfunction manifests as the core clinical symptoms of AN, including cognitive inflexibility, anhedonia, and body image distortion.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical neurodevelopmental framework for the etiology of Anorexia Nervosa (AN). The model integrates genomic findings from MAGMA, LDSC, TWAS, and Mendelian Randomization. Top: Genetic liability converges on synaptic pruning machinery e.g., C4A and RHOA and glutamatergic signaling e.g., PKA and CaMKII. Middle: These molecular deficits interact with a high-plasticity genetic background and environmental triggers during the critical adolescent window. The resulting “over-pruning” creates a sparse neural network characterized by rigid dorsal loops and disconnected insular hubs. Bottom: This circuit dysfunction manifests as the core clinical symptoms of AN, including cognitive inflexibility, anhedonia, and body image distortion.

Putting all the pieces together, we arrive at a developmental story in which common variants tilt the normal pruning-versus-plasticity balance that shapes the adolescent brain. Extra complement activity driven by C4A tags too many synapses for removal, while weaker WNT–cytoskeleton support from genes such as CTNNB1 and RHOA makes the surviving contacts fragile, pushing the system toward over-pruning [

20,

21]. At the same time, low glutamatergic tone robs circuits of the activity-dependent “rescue” signals that usually spare useful connections, so the end product is a sparse, somewhat inefficient network. The fact that pruning enrichment remains significant after every glutamatergic gene is taken out sets anorexia nervosa apart from disorders like obsessive–compulsive disorder, where pruning dominates without a parallel glutamate signal.

This developmental tilt neatly explains several headline symptoms. Distorted body image and an intense fear of weight gain may occur if excessive pruning in the insular and parietal hubs interferes with the integration of interoceptive and visual information, a situation exacerbated by inadequate glutamatergic calibration [

22]. Endless restrictions on food fit with muted reward coding in the ventral striatum: fewer glutamatergic inputs mean smaller dopaminergic bursts, and lost projections make eating less pleasurable, which makes people want to control their hunger more with their minds [

23]. Cognitive inflexibility and perfectionism—traits that often pre-date illness—emerge when over-pruning, especially in individuals with high baseline intelligence, locks dorsal prefrontal–striatal loops into rigid response sets [

24]. Anxiety and emotional lability follow naturally from weakened inhibitory links between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

Epidemiological patterns line up as well. Onset peaks in mid-adolescence, exactly when synaptic pruning is most active, and the striking female predominance may reflect estrogen’s ability to modulate microglial behaviour [

25]. Environmental factors that stimulate microglial activation—such as early dieting, psychosocial stress, and gut dysbiosis—may precipitate a threshold response in a genetically predisposed brain [

26]. The model integrates pruning dynamics, glutamatergic tone, and cognitive style, producing distinct, testable predictions and indicating therapies that either mitigate excessive synapse elimination or augment glutamatergic plasticity.

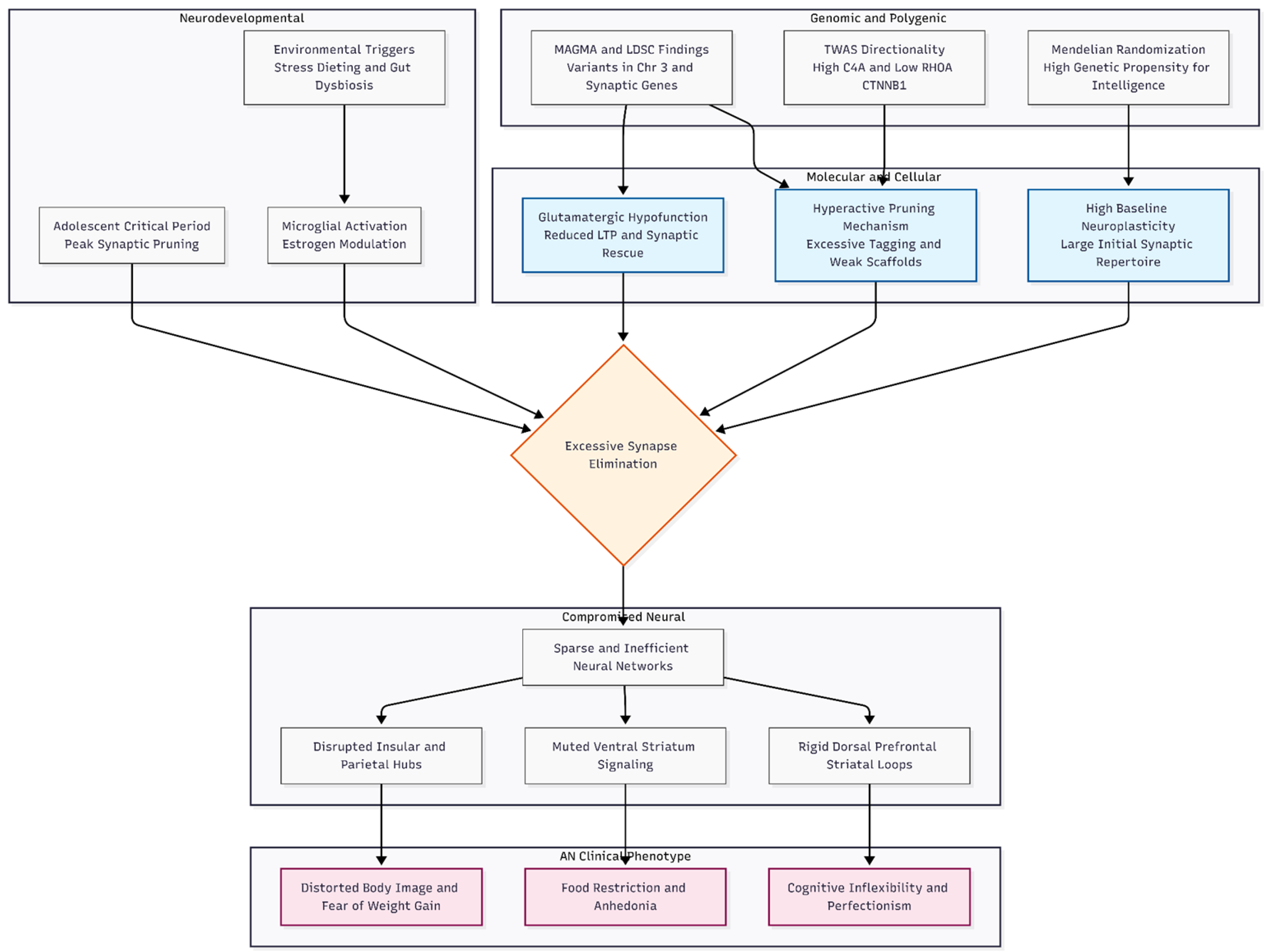

Insights from the Contrasts with the Parallel OCD Study

Placing our anorexia nervosa (AN) results alongside a nearly parallel genome-wide study of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) adds useful context. Using the same analytic toolkit—MAGMA gene and gene-set tests, stratified LD-score regression (LDSC) and transcriptome-wide association (TWAS)—the OCD analysis [

19] found no single genes at genome-wide significance, yet showed clear enrichment of heritability in microglial-mediated synaptic pruning pathways. Pruning signals remained significant after glutamatergic genes were removed, whereas glutamatergic pathways were largely absent. TWAS in OCD pointed to higher expression of complement genes such as C4A and of microglial marker TMEM119, reinforcing a picture of immune-driven over-pruning in cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits.

Our AN data share that pruning signature—Bonferroni-significant enrichment in pruning gene sets and LDSC enrichment above unity—but differ in two important ways. First, AN also shows independent enrichment of glutamatergic signalling genes, including TWAS evidence for reduced PKA/CaMKII-related expression. Second, Mendelian randomisation (MR) links genetically predicted higher intelligence and educational attainment to greater AN risk, suggesting that unusually high baseline synaptic plasticity may amplify vulnerability to excessive pruning. These distinctions, absent in the OCD profile, imply partly shared but ultimately divergent biological routes: pruning appears to be a common developmental risk process, while glutamatergic hypofunction and cognitive amplification seem specific to AN.

This contrast helps explain the clinical overlap and differences between the disorders (

Figure 2). Both illnesses feature behavioural rigidity, consistent with pruning-driven reductions in frontal-striatal connectivity. Yet OCD is dominated by anxiety-provoking obsessions and ego-dystonic compulsions, a pattern compatible with “pure” pruning that traps CSTC loops in habitual feedback while leaving enough glutamatergic tone for threat signalling and partial extinction learning [

9]. In AN, pruning works with primary glutamatergic deficits to dull the reward system in the mesolimbic area and make eating less rewarding [

23]. More pruning in the insular and parietal networks probably messes up how we process our body image and interoception [

22]. High cognitive capacity, when coupled with synaptic loss, may then foster an extreme, ego-syntonic pursuit of dietary control. Persistent illness and resistance to treatment may stem from this double hit: synapses are not only removed but also poorly protected by weakened long-term potentiation, leaving little plasticity for recovery [

7].

The shared pruning signal raises trans-diagnostic possibilities. Agents that temper microglial activity—minocycline, for example—might benefit both disorders, whereas glutamate-enhancing strategies (e.g., ketamine, d-cycloserine) could be particularly relevant to AN, where glutamatergic deficits are primary rather than secondary.

Strengths, Limitations and Conclusion

The present re-analysis extends synaptic pruning models to eating disorders and places anorexia nervosa (AN) within the emerging “pruning spectrum” of psychiatric illness. Until now, pruning has been examined mainly in schizophrenia and, more recently, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); in AN evidence was largely speculative, drawn from neuroimaging or metabolic theories [

6,

10]. By showing that pruning gene sets are enriched in AN—independently of glutamatergic genes—and that TWAS points to the same direction of effect, we provide the first genomic support that excessive adolescent synapse elimination is central to AN pathophysiology. Mendelian-randomisation links between higher cognitive ability and AN risk add a plausible amplification mechanism that has not been reported in OCD [

19].

Seen alongside the parallel OCD study that used an almost identical pipeline [

19], several themes emerge. First, pruning enrichment appears trans-diagnostic; both AN and OCD show robust signals that survive removal of glutamatergic genes. Second, the two disorders diverge downstream. In OCD, pruning is more common than glutamatergic pathways, and TWAS shows that immune markers like C4A are turned on, which is consistent with microglia-driven synaptic loss in cortico-striatal circuits. In anorexia nervosa (AN), pruning occurs alongside glutamatergic hypofunction and the down-regulation of cytoskeletal genes. This indicates that diminished long-term potentiation restricts synaptic maintenance, thereby amplifying the effects of pruning.The MR signal connecting cognitive traits to AN but not OCD further differentiates the two conditions, implying that individuals with greater baseline plasticity may be more vulnerable to pruning-related loss.

These biological differences fit perfectly with how the disease looks in people. Shared pruning could explain why both disorders cause cognitive rigidity and habitual responding. On the other hand, AN’s extra glutamatergic deficit fits with a lack of reward and a constant avoidance of food [

27]. Body-image distortion may result from pruning in interoceptive networks, exacerbated by glutamatergic underactivity that disrupts sensory calibration. In contrast, OCD’s anxiety-driven rituals fit with pruning-induced habit loops that remain sensitive to threat signals because glutamatergic tone is relatively intact.

The findings have practical implications. Minocycline and other microglial modulators, already tested in schizophrenia and OCD, might also benefit AN by dampening pruning. At the same time, glutamate-enhancing agents—ketamine, d-cycloserine, or nutritional zinc—could target the AN-specific glutamatergic deficit. Monitoring adolescents with high cognitive polygenic scores during periods of caloric restriction may offer a preventive angle, given the MR link to intelligence.

Limitations include reliance on the 2019 PGC AN dataset, TWAS constrained by GTEx tissue coverage, and potential residual confounding in partitioned heritability. Replication in larger and more diverse samples is essential, as is experimental work to test gene–environment interplay in shaping microglial activity.

In summary, we propose that AN stems from exaggerated synaptic pruning during adolescence, reinforced by primary glutamatergic hypofunction and amplified in cognitively plastic individuals. This model amalgamates metabolic, cognitive, and neurodevelopmental evidence, reconceptualizes AN within neurobiological frameworks common to other psychiatric disorders, and indicates biologically informed interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. [CrossRef]

- Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406–414. [CrossRef]

- Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the twentieth century. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(8), 1284–1293. [CrossRef]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Tozzi F, et al. Prevalence, heritability, and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(3), 305-312.

- Thornton LM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM. The heritability of eating disorders: methods and current findings. Behavioral neurobiology of eating disorders, 141-156.

- Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nature Genetics, 51(8), 1207–1214. [CrossRef]

- Godlewska BR, Pike A, Sharpley AL, et al. Brain glutamate in anorexia nervosa: A magnetic resonance spectroscopy case-control study at 7 Tesla. Psychopharmacology, 234(3), 421–426. [CrossRef]

- Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature, 530(7589), 177–183. [CrossRef]

- Piantadosi SC, Chamberlain BL, Glausier JR, et al. Lower excitatory synaptic gene expression in orbitofrontal cortex and striatum in subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(3), 986–998. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Z, Hardaway JA, Bulik CM. Genetics and epigenetics of eating disorders. Advances in genomics and genetics, 131-150.

- de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, et al. MAGMA: Generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLOS Computational Biology, 11(4), e1004219. [CrossRef]

- Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan B, Gusev A, et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nature Genetics, 47(11), 1228-1235. [CrossRef]

- Barbeira AN, Dickinson SP, Bonazzola R, et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1825. [CrossRef]

- Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genetic Epidemiology, 37, 658-665. [CrossRef]

- Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nature Genetics, 50, 1112-1121. [CrossRef]

- Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269 867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nature Genetics, 50, 912-919. [CrossRef]

- Strom NI, Gerring ZF, Galimberti M, et al. Genome-wide analyses identify 30 loci associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. medRxiv : the preprint server for health sciences, 2024.03.13.24304161. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Multi-Method Polygenic Investigation Implicates Dysregulated Synaptic Pruning in the Etiology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Strom NI, Gerring ZF, Galimberti M, et al. Genome-wide analyses identify 30 loci associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. medRxiv : the preprint server for health sciences, 2024.03.13.24304161. [CrossRef]

- Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science, 333(6048), 1456–1458. [CrossRef]

- Stephan AH, Barres BA, Stevens B. The complement system: An unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 369–389. [CrossRef]

- Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Manara R, et al. Disruption of visuospatial and somatosensory functional connectivity in anorexia nervosa. Biological psychiatry, 72(10), 864-870.

- Peters SK, Dunlop K, Downar J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the salience network: a central pathway in psychiatric disease and treatment. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 10, 104.

- Sato Y, Saito N, Utsumi A, et al. Neural basis of impaired cognitive flexibility in patients with anorexia nervosa. PloS one, 8(5), e61108.

- Juraska JM, Sisk CL, DonCarlos LL. Sexual differentiation of the adolescent rodent brain: hormonal influences and developmental mechanisms. Hormones and behavior, 64(2), 203-210.

- Breton J, Déchelotte P, Ribet D. Intestinal microbiota and anorexia nervosa. Clinical Nutrition Experimental, 28, 11-21.

- Hermens DF, Simcock G, Dutton M, et al. Anorexia nervosa, zinc deficiency and the glutamate system: The ketamine option. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 101, 109921.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).