1. Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex psychiatric disorder marked by intense fear of weight gain, distorted body image, and restrictive behaviors aimed at weight loss [

1] . It is linked to poor quality of life [

2] and a mortality rate at least five times higher than healthy individuals [

3]. AN is now recognized as a multifactorial condition influenced by biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors [

4]. Diagnostic criteria have evolved across DSM editions: from DSM-III (1980) [

5], which first categorized AN as an eating disorder, to DSM-5 (2013) [

6], which removed amenorrhea as a requirement and emphasized body image disturbance and restrictive behaviors.

Several clinical variables contribute to a poor prognosis, including anxiety comorbidity, low body mass index (BMI), duration of untreated illness [

7], and longer illness duration [

8]. Later onset was also associated with lower BMI at initial medical evaluation [

9]. Current guidelines recommend psychotherapy—especially Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)—as first-line treatment for adults [

10]. Among medications, only olanzapine shows limited efficacy, mainly for weight gain [

11]. Given the serious cognitive and physical consequences of AN, including increased susceptibility to infections, early and targeted intervention is critical [

12].

Epidemiological data show that AN primarily affects females, with about 1% prevalence among adolescent girls and young women [

13]. Incidence in males is lower, possibly due to underdiagnosis [

13]. Onset typically occurs between ages 12 and 25, peaking around 14 and 18, though cases are increasingly reported in children as young as 8–9 [

14]. Adolescence is a sensitive time for body image and identity development, and sociocultural pressures to conform to idealized body standards may increase risk [

15]. In this framework, a key clinical variable in AN is represented by age at onset, which affects illness severity, response to treatment, and biological trajectory. An earlier onset would account for larger alterations on neurodevelopment, while a later onset is associated with lower BMI at initial assessment [

9]. This highlights the prognostic importance of when the illness begins.

In the light of these considerations, purpose of the present research is to investigate the role of age at onset (AAO) on the course of AN. This may help clinicians to tailor the management of AN patients, basing on clinical and biological variables associated with AAO.

2. Materials and Methods

A sample of patients diagnosed with AN were recruited for this observational, retrospective study. Participants were either hospitalized at the inpatient clinic of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico in Milan or followed as outpatients at the Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori in Monza. The diagnosis of AN was confirmed by experienced psychiatrists based on the criteria of the DSM-5.

Inclusion criteria consisted of a DSM-5 diagnosis of AN. Exclusion criteria included: (1) malnutrition due to severe medical complications such as renal failure, advanced liver disease, or severe gastrointestinal disorders; (2) pregnancy or breastfeeding, (3) and the intake of vitamin B or D supplements, which could interfere with biochemical analyses. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU Regulation 2016/679). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ospedale San Gerardo di Monza (Approval No. 4060, approved on 20/03/2023).

During the initial psychiatric evaluation, data were collected on demographic variables (age, marital status, employment status, years of education), and clinical variables (age at onset, total illness duration, duration of untreated illness-DUI, body mass index-BMI, treatment setting, substance use disorders including polysubstance use disorders, psychiatric family history, psychiatric and medical comorbidities, presence of personality disorders, and current psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments). A blood sample was collected in the same baseline visit at late morning to measure the following biochemical variables: sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K+), Na⁺/K⁺ ratio, red and white blood cell counts, mean corpuscular volume, haemoglobin, lymphocytes, neutrophils, platelets, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), iron, vitamin D, folate, vitamin B12, and total cholesterol.

DUI was defined as the time between the onset of AN and the initiation of an appropriate treatment according to international guidelines (family therapy for adolescents, cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults, and olanzapine for weigh gain) [

10,

7]. In cases of psychiatric comorbidity, AN was considered the main disorder when it had the greatest impact on the psychosocial functioning. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 29.0).

Descriptive analyses were conducted on all variables.

The total sample was first divided in two groups according to an early AAO (< 18 years) or late AAO (≥ 18 years). The groups were compared by unpaired sample t tests for continuos variables and χ2 tests with odds ratio-OR and 95% confidence interval-CI calculation for qualitative variables. The statistically significant variables at t tests were inserted as predictors in a binary logistic regression model with early versus late AAO as dependent variable.

Correlation analyses were then preformed between AAO and continuous variables. Those found to be statistically significant in the correlation analyses were inserted as independent variables in a linear regression model with AAO as dependent factor.

A p ≤ 0.05 was adopted as a statistically significant threshold for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 76 female patients affected by AN. Among these, 12 (15.8%) were hospitalized in the inpatient clinic for intensive residential treatment, while the remaining 64 (84.2%) were treated in the outpatient clinic with periodic visits and continuous monitoring.

The mean age of the participants was 23.19 years (± 8.32), with an age range from 18 to 40 years. The mean AAO of the disorder was 18.42 years (± 6.48), indicating a prevalence of the disorder at young age, with onset coinciding with life transition to adolescence or early adulthood. The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) was 17.21 kg/m² (± 2.21), significantly lower than the normal range, reflecting the severity of the eating disorder.

Thirteen subjects were in treatment with pharmacological compounds: 1 with sertraline, 2 with escitalopram, 1 with olanzapine, 2 with quetiapine, 1 with aripiprazole, 1 with mirtazapine, 2 with asenapine, 2 with duloxetine and 1 with haloperidol.

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

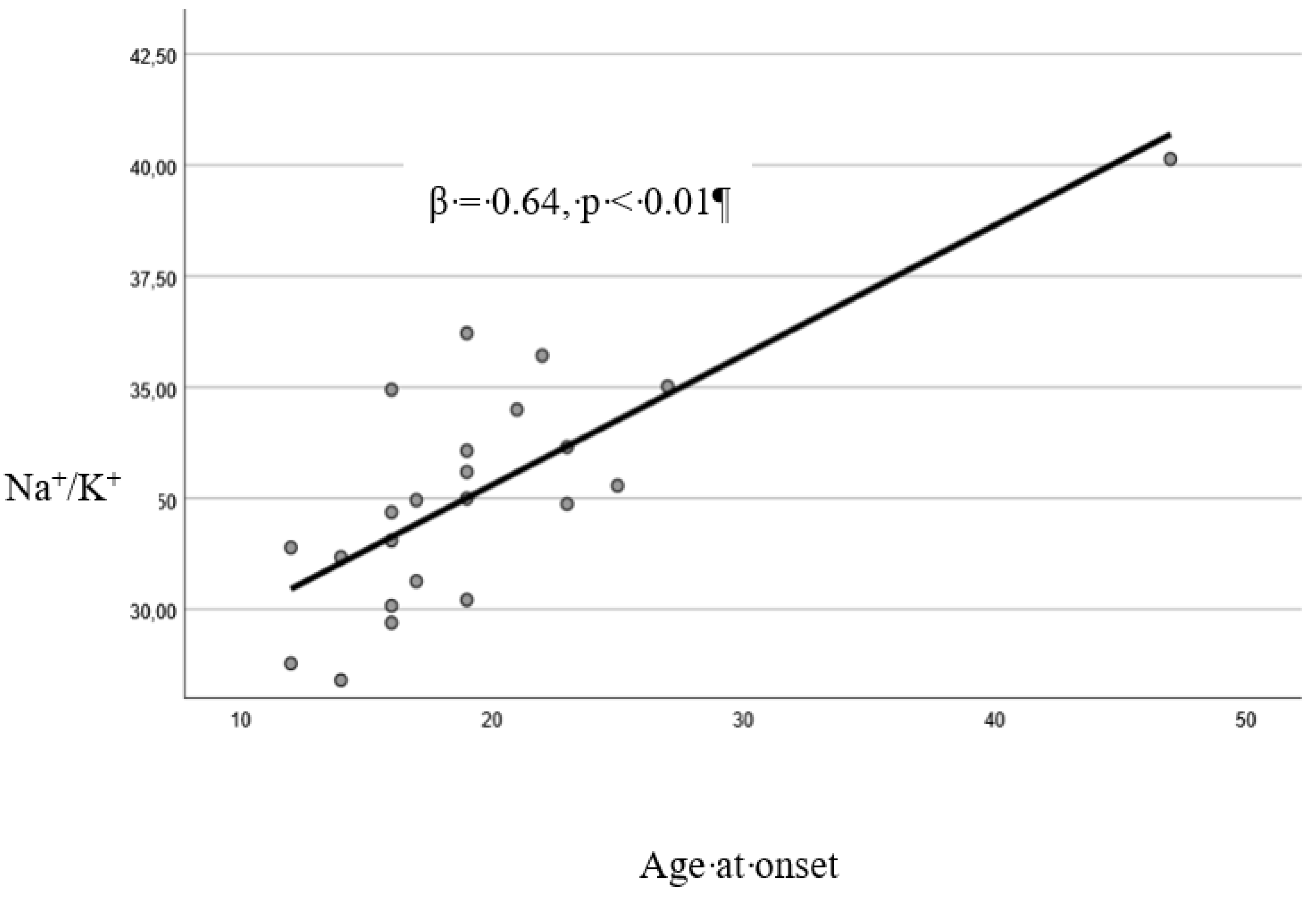

Table A2 summarize the descriptive analyses of the total sample and of the groups identified by AAO, as well as the results of respectively t tests and χ2 tests. Early versus late-onset patients resulted: to be younger (t=2.86, p<0.01), to have less years of education (t=3.10, p=0.01), to have a longer duration of illness at borderline statistical significance (t=1.88, p=0.06), to have higher K+ levels (t=3.63, p<0.01) and consequently lower Na+/K+ (t=3.39, p<0.01), to be more frequently students (χ2=12.23, p=0.02), to have less frequently comorbidity with depressive disorders (χ2=10.84, p=0.03) or medical comorbidity (χ2=13.63, p=0.02).

The goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer and Lemeshow Test: χ2=7.62, p=0.47) and omnibus test (χ2=11.97, p<0.01) showed that the model including duration of illness and Na+/K+ as possible predictors of early versus late AAO was reliable, allowing for a correct classification of 87.0% of the cases. A higher Na+/K+ resulted to predict a later age at onset (p=0.03) (

Table A3).

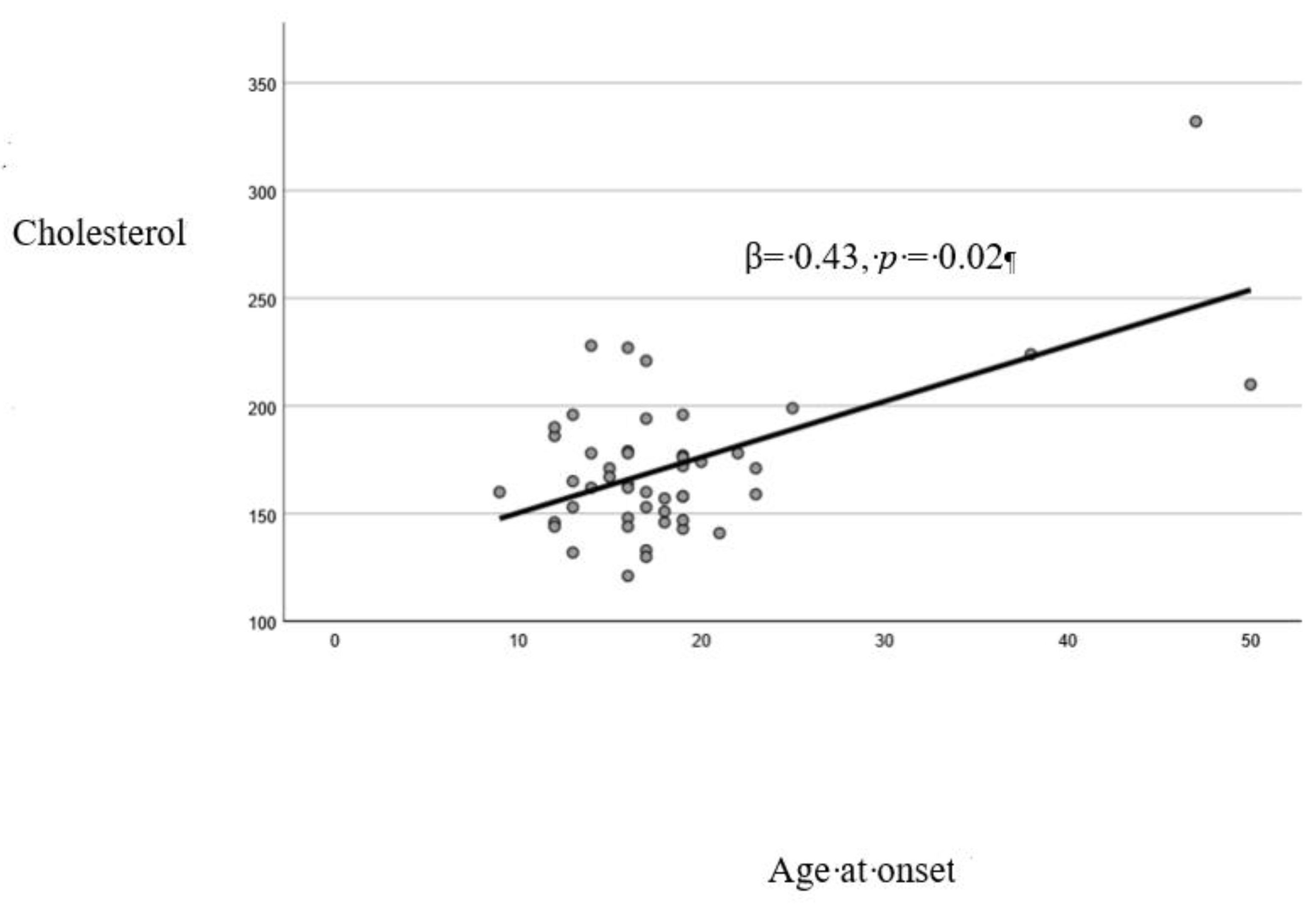

A significant direct correlation was found between AAO and: age (Pearson’s r=0.66, p<0.01). years of education (r=0.30, p<0.01), Na+/K+ (r=0.78, p<0.01), cholesterol plasma levels (r=0.57, p<0.01) (

Table A4).

The linear regression model resulted to be reliable (Durbin-Watson: 2.25). Cholesterol (p=0.02) and Na+/K+ (p<0.01) resulted to be significantly associated with AAO (

Table A5).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the AAO in AN is significantly associated with several clinical and biochemical parameters. In particular, a relationship was found between the onset of AN and the Na+/K+, blood cholesterol levels, years of education, employment status, psychiatric and medical comorbidity.

The association between an earlier AAO and a lower Na

+/K

+ could point out that patients with childhood or adolescent onset tend to show electrolyte imbalances that may reflect more pronounced metabolic dysregulation, potentially involving the renin-angiotensin system [

16]. Furthermore, even though there is no robust evidence to this phenomenon in the scientific literature, it is known that some individuals with AN tend to misuse dietary supplements containing electrolytes such as K

+ [

17]. It is therefore plausible to hypothesize that the observed electrolyte imbalances may, at least in part, be attributed to a pathological compensatory mechanism related to the disorder. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that many individuals with AN engage in extreme exercise regimens, often combined with excessive use of dietary supplements, in an effort to enhance physical performance and, indirectly, increase energy expenditure [

18]. Moreover, as mentioned above, abnormalities in Na

+ and K

+ levels serve as indirect indicators of alterations in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, a condition well documented in women with AN and potentially more pronounced in those who remain without adequate medical supervision for extended periods [

19].

Blood cholesterol levels also appear to be influenced by AAO, suggesting that patients with late-onset AN may be at greater risk of developing metabolic-related cardiovascular complications over the course of the illness. This finding may be explained by the fact that during adolescence and early adulthood, women undergo significant hormonal changes that influence lipid metabolism, being oestrogens protective against dyslipidemia [

20]. For example, AN-related variations in estrogen production as well as in thyroid function could have a greater impact in women with late AAO [

21]. Of note, cholesterol plays important roles in mental health, contributing to integrity of central nervous system [

22] and being precursor of important molecules such as vitamin D that regulates dopamine pathways [

23]. It should be noted that in our sample, women with late AAO presented more psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depressive disorders.

The differences in years of education between the two AAO groups could simply be explained by the fact that many patients are still in school. However, they suggest that early-onset (childhood/adolescence) AN may be associated with developmental and relational issues, thereby influencing the course and management of the disorder. The education level of patients with AN can be a critical aspect to examine in relation to the course of the illness. Of note, a recent article examined the educational level of patients’ parents, finding that subjects with parents with high educational levels had a longer length of stay during hospitalizations, less dietary restraint, and higher personal standards [

24]. As mentioned above, the results of our analysis pointed out that patients with adult-onset AN show a higher frequency of comorbid depression. Psychiatric comorbidities are conditions that may occur before or after the onset of AN, increasing the severity of the illness and potentially complicating treatment management and future prognosis [

25]. The frequent co-occurrence of depression in patients with late-onset AN makes challenging their management due to the overlap of certain symptomatic characteristics between AN and depression, such as reduced food intake or insomnia [

26]. These issues are further exacerbated by the fact that patients with late-onset AN are more likely to have medical comorbidities, which in turn increases their vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and worsens the course of AN [

27].

5. Study limitations

The results of this study must be interpreted with caution, considering several methodological limitations. A first limitation is the retrospective nature of data collection, which in some cases made it difficult to retrieve detailed information on specific clinical aspects of the patients included in the study, although the computerized medical records and regional databases facilitated this task. In addition, a large amount of data are lacking for some variables as they are not routinely collected in one of the participating centers. Second, the clinical characteristics and illness severity of our sample may not be fully representative of patients with AN who do not access specialized services or those with milder forms of the disorder. Third, some clinical data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, a context that may have negatively affected the course of eating disorders [

28,

29]. Fourth, in our study only total cholesterol (TC) was measured, without including a complete lipid profile, and only total vitamin B12 was evaluated, without assessing other biomarkers useful for a more in-depth analysis of cobalamin status, such as holotranscobalamin [

30] or other markers of this vitamin status [

31]. Fifth, another criticism concerns the diagnosis of AN severity, which was based solely on BMI, in accordance with the DSM-5. However, the severity of the disorder is a more complex concept, encompassing not only the rate of weight loss, but also body composition, and psychological aspects such as body image distortion [

32]. Sixth, an additional factor to consider is that some subjects were undergoing pharmacological treatment. While the effectiveness of these drugs in weight recovery in patients with AN remains debated [

33], it is plausible that they may positively impact symptoms such as anxiety, compulsive behaviors, and depression [

34]. In addition, it is known that these medications can influence biochemical parameters [

35]. Lastly, despite excluding patients taking vitamin B12 supplements, the use of other supplements or substances may have altered some biomarker values, representing a further confounding factor.

6. Conclusion

These results highlight the importance of personalizing therapeutic approaches based on the AAO of the disorder, in order to optimize interventions and improve clinical outcomes for each patient group. Our analysis highlighted how patients, depending on their AAO, may have different clinical and metabolic profiles that require specific treatment (electrolyte imbalance for earlier AAO and dyslipidemia for later AAO individuals). Considering the clinical implications arising from our research, it becomes clear that an integrated and multidisciplinary therapeutic approach is essential to effectively address the management of AN. As well as a pharmacological or psychotherapeutic approach, according to patients’ AAO, it will be necessary to take in consideration the prescription of targeted diets to prevent electrolyte imbalance and hypercholesterolemia, or complementary treatments such as yoga to address psychiatric/medical comorbidity [

36,

37].

Future research will have to confirm the results of the present article, and studies with larger samples are necessary to clarify the role of AAO in the outcome of patients affected by AN.

Abbreviations:

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AN – Anorexia Nervosa

AAO – Age at Onset

BMI – Body Mass Index

CBT – Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

DUI – Duration of Untreated Illness

Na – Sodium ion

K – Potassium ion

Na/K – Sodium-to-Potassium Ratio

NLR – Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio

PLR – Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio

OR – Odds Ratio

CI – Confidence Interval

SPSS – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TC – Total Cholesterol

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.; methodology, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, A.C., E.C., L.F., and L.M.A.; resources, E.C., L.M.A. and M.C.; data curation, E.C., L.F., and L.M.A; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and L.F; writing—review and editing, A.C., L.F, and M.B.; supervision, A.C., A.D., M.B. and M.C.; project administration, E.C., A.D. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration 230 of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) CET3 of Lombardia. Region (protocol code 3951).

Informed Consent Statement

Being a retrospective study informed consent could have been obtained after the collection of data and in some cases lacking due to no-follow up in the involved centers. The data presented in this article are aggregated and anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, is funded by the Italian Ministry of Education and Research (MUR): Dipartmenti di Eccellenza Program 2023 to 2027.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Appendix A

Table A1.

Continuous clinical variables and biochemical parameters of the total sample and of the two groups identified by age at onset.

Table A1.

Continuous clinical variables and biochemical parameters of the total sample and of the two groups identified by age at onset.

| Variables |

Total sample

n= 76 |

Early Onset

(< 18 years)

n=42 |

Late onset

(≥ 18 years)

n=34 |

t |

p |

Age

Missing n = 0 |

23.12 ± 8.32 |

20.69 ± 6.48 |

26.12 ± 9.40 |

2.86 |

<0.01 |

DUI (years)

Missing n = 0 |

2.11 ± 2.71 |

2.26 ± 2.27 |

1.92 ± 3.15 |

0.54 |

0.59 |

Duration of illness (years)

Missing n = 0 |

4.17 ± 5.81 |

5.28 ± 7.01 |

2.80 ± 3.45 |

1.88 |

0.06 |

Educational status (years)

Missing n = 4 |

12.21 ± 3.04 |

11.26 ± 3.05 |

13.33 ± 2.64 |

3.10 |

0.01 |

BMI

Missing n = 4 |

17.23 ± 2.23 |

17.25 ± 1.92 |

17.21 ± 2.57 |

0.07 |

0.95 |

NA+ (mmol/L)

Missing n = 52 |

140.33 ± 2.78 |

140.99 ± 2.58 |

139.56 ± 2.91 |

1.08 |

0.29 |

K+ (mmol/L)

Missing n = 53 |

4.33 ± 0.35 |

4.55 ± 0.28 |

4.12 ± 0.29 |

3.63 |

<0.01 |

NA+/K+

Missing n = 53 |

32.66 ± 2.68 |

31.03 ± 1.84 |

34.15 ± 2.49 |

3.39 |

<0.01 |

Red blood cells (10⁶/mm³)

Missing n = 50 |

4.27 ± 0.44 |

4.19 ± 0.42 |

4.32 ± 0.46 |

0.76 |

0.45 |

MCV (fL)

Missing n = 50 |

90.82 ± 5.47 |

90.39 ± 4.50 |

91.14 ± 6.21 |

0.34 |

0.74 |

Hb (g/dL)

Missing n = 50 |

13.05 ± 1.26 |

12.80 ± 1.44 |

13.23 ± 1.13 |

0.85 |

0.41 |

Leukocytes (10⁹/L)

Missing n = 2 |

5.67 ± 1.76 |

5.80 ± 1.81 |

5.51 ± 1.71 |

0.71 |

0.48 |

Lymphocytes (10⁹/L)

Missing n = 3 |

2.13 ± 0.75 |

2.23 ± 0.81 |

2.00 ± 0.64 |

1.28 |

0.20 |

Neutrophils (10⁹/L)

Missing n = 29 |

3.23 ± 1.70 |

3.25 ± 1.77 |

3.20 ± 1.63 |

0.11 |

0.91 |

Platelets (10⁹/L)

Missing n = 2 |

227.66 ± 49.34 |

232.53 ± 45.76 |

221.94 ± 53.37 |

0.92 |

0.36 |

NLR

Missing n = 29 |

1.55 ± 0.94 |

1.37 ± 0.69 |

1.83 ± 1.20 |

1.49 |

0.15 |

PLR

Missing n = 3 |

117.06 ± 41.06 |

114.04 ± 38.26 |

120.72 ± 44.54 |

0.69 |

0.49 |

Iron (μg/dL)

Missing n = 20 |

106.60 ± 74.72 |

110.73 ± 87.67 |

101.82 ± 57.64 |

0.64 |

0.66 |

Vitamin D (ng/mL)

Missing n = 34 |

30.58 ± 14.24 |

29.92 ± 14.41 |

31.46 ± 14.39 |

0.34 |

0.73 |

Folate (ng/mL)

Missing n = 21 |

8.86 ± 6.24 |

7.91 ± 3.69 |

10.00 ± 8.29 |

1.17 |

0.25 |

Vitamin B12 (pg/mL)

Missing n = 26 |

529.42 ± 325.68 |

553.03 ± 376.15 |

500.92 ± 256.90 |

0.58 |

0.57 |

Cholesterol (mg/dL)

Missing n = 28 |

172.10 ± 34.94 |

167.57 ± 28.13 |

178.45 ± 42.69 |

1.07 |

0.29 |

Table A2.

Qualitative clinical variables of the total sample and of the two groups identified by age at onset.

Table A2.

Qualitative clinical variables of the total sample and of the two groups identified by age at onset.

Variables

|

Total sample

n = 76 |

Early Onset

(< 18 years)

n=42 |

Late onset

(≥ 18 years)

n=34 |

χ2

|

OR (95% CI) |

p |

Current partner

Missing n = 10 |

No |

47 (71.2%) |

21 (63.6%) |

26 (78.8%) |

1.85 |

0.47 (0.16-1.41) |

0.28 |

| Yes |

19 (28.8%) |

12 (36.4%) |

7 (21.2%) |

Work status

Missing n = 3 |

Unemployed |

13 (17.8%) |

10 (25%) |

3 (9.1%) |

12.23 |

/* |

0.02 |

| Student |

49 (67.1%) |

29 (72.5%) |

20 (60.6%) |

| Worker |

11 (15.1%) |

1 (2.5%) |

10 (30.3%) |

Lifetime substance use disorders

Missing n = 2 |

No |

65 (87.8%) |

36 (90.0%) |

29 (85.3%) |

0.38 |

1.55 (0.38-6.31) |

0.72 |

| Yes |

9 (12.2%) |

4 (10.0%) |

5 (14.7%) |

Lifetime poly-substance use disorders

Missing n = 3 |

No |

70 (95.9%) |

38 (95.0%) |

32 (97.0%) |

0.51 |

2.38 (0.21-27.42) |

0.59 |

| Yes |

3 (4.1%) |

2 (5.0%) |

1 (3.0%) |

Psychiatric family history

Missing n = 2 |

No |

49 (66.2%) |

25 (62.5%) |

24 (70.6%) |

0.54 |

0.69 (0.26-1.84) |

0.62 |

| Yes |

25 (33.8%) |

15 (37.5%) |

10 (29.4%) |

Current psychotherapy

Missing n = 14 |

No |

58 (93.5%) |

32 (97%) |

26 (89.7%) |

1.37 |

3.69 (0.36-37.63) |

0.33 |

| Yes |

4 (6.5%) |

1 (3.0%) |

3 (10.3%) |

Psychiatric comorbidity

Missing n = 0 |

No |

51 (67.1%) |

29 (69.0%) |

22 (64.7%) |

0.16 |

1.22 (0.47-3.18) |

0.80 |

| Yes |

25 32.9%) |

13 (31.0%) |

12 (35.3%) |

Type of psychiatric comorbidity

Missing n = 0 |

None |

51 (67.1%) |

29 (69.0%) |

22 (64.7%) |

10.84 |

/* |

0.03 |

| Depression |

10 (13.2%) |

2 (4.8%) |

8 (23.5%) |

| Anxiety disorders |

8 (10.5%) |

4 (9.5%) |

4 (11.8%) |

| OCD |

2 (2.6%) |

2 (4.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Other |

5 (6.6%) |

5 (11.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

Psychiatric poly-comorbidity

Missing n = 0 |

No |

68 (89.5%) |

37 (88.1%) |

31 (91.2%) |

0.19 |

0.72 (0.16-3.24) |

0.73 |

| Yes |

8 (10.5%) |

5 (11.9%) |

3 (8.8%) |

Personality Disorder

Missing n = 4 |

None |

63 (87.4%) |

32 (84.3%) |

31 (91.2%) |

8.82 |

/* |

0.06 |

| Schizoid |

1 (1.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (2.9%) |

| Schizotypal |

2 (2.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (5.9%) |

| Borderline |

4 (5.6%) |

4 (10.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| OCD |

1 (1.4%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| PD-NOS |

1 (1.4%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

Thyroid disorders

Missing n = 10 |

No |

65 (98.5%) |

38 (97.4%) |

27 (100%) |

0.70 |

0.58 (0.48-0.72) |

1.00 |

| Yes |

1 (1.5%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0 (0%) |

Hypercholesterolemia

Missing n = 7 |

No |

66 (95.7%) |

37 (94.9%) |

29 (96.7%) |

0.31 |

0.64 (0.06-7.39) |

1.00 |

| Yes |

3 (4.3%) |

2 (5.1%) |

1 (3.3%) |

Diabetes

Missing n = 8 |

No |

68 (100%) |

39 (100%) |

29 (100%) |

/** |

/** |

/** |

| Yes |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

Current medical poly-comorbidity

Missing n = 4 |

No |

69 (95.8%) |

40 (97.6%) |

29 (93.5%) |

0.71 |

2.76 (0.24-31.89) |

0.57 |

| Yes |

3 (4.2%) |

1 (2.4%) |

2 (6.5%) |

Type of current medical comorbidity

Missing n = 27 |

None |

37 (75.6%) |

26 (86.7%) |

11 (57.9%) |

13.63 |

/* |

0.02 |

| CRF |

1 (2.0%) |

1 (3.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| GERD |

2 (4.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (10.5%) |

| Hyperthyroidism |

1 (2.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (5.3%) |

| Thalassemia |

2 (4.1%) |

2 (6.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Endocrine disorders |

3 (6.2%) |

1 (3.3%) |

2 (10.5%) |

| Blood disorders |

1 (2.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (5.3%) |

| Others |

2 (4.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (10.5%) |

Table A3.

Summary of the results from binary logistic regression model.

Table A3.

Summary of the results from binary logistic regression model.

| Variables |

B |

SE |

P avlue |

OR |

95% CI |

| Inferior |

Superior |

| Duration of illness |

-0.17 |

0.19 |

0.36 |

0.84 |

0.58 |

1.21 |

| Sodium/Potassium |

0.80 |

0.37 |

0.03 |

2.23 |

1.1 |

4.57 |

Table A4.

Significant correlations between age at onset and continuos variables.

Table A4.

Significant correlations between age at onset and continuos variables.

| Variables correlated with age at onset |

r |

p |

| Age (years) |

0.66 |

< 0.01 |

| Education level (years) |

0.30 |

< 0.01 |

| K+ (mmol/L) |

-0.75 |

< 0.01 |

| NA+/K+ |

0.78 |

<0.01 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

0.57 |

<0.01 |

Table A5.

Linear regression model with age at onset as dependent variable.

Table A5.

Linear regression model with age at onset as dependent variable.

| VARIABLE |

B |

SE |

β |

p |

| Cholesterol |

0.07 |

0.02 |

0.43 |

0.02 |

| NA+/K+ |

1.68 |

0.31 |

0.64 |

< 0.01 |

Figure A1.

Linear relationship between cholesterol and age at onset.

Figure A1.

Linear relationship between cholesterol and age at onset.

Figure A2.

Linear relationship between the sodium/potassium (Na+/K+) ratio and age at onset.

Figure A2.

Linear relationship between the sodium/potassium (Na+/K+) ratio and age at onset.

References

- Yu, Z.; Muehleman, V. Eating Disorders and Metabolic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the Burden of Eating Disorders: Mortality, Disability, Costs, Quality of Life, and Family Burden. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artoni, P.; Chierici, M.L.; Arnone, F. Body Perception Treatment, a Possible Way to Treat Body Image Disturbance in Eating Disorders: A Case–Control Efficacy Study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Affaticati, L.M.; Capuzzi, E.; Zuliani, T.; Legnani, F.; Vaccaro, N.; Manzo, F.; Scalia, A.; La Tegola, D.; Nicastro, M.; Colmegna, F.; et al. The Role of Duration of Untreated Illness (DUI) on the Course and Biochemical Parameters of Female Patients Affected by Anorexia Nervosa. Brain Behav. 2025, 15, e70584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasofer, D.R.; Muratore, A.F.; Attia, E.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Minkoff, H.; Rufin, T.; Walsh, B.T.; Steinglass, J.E. Predictors of Illness Course and Health Maintenance Following Inpatient Treatment among Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, H.; Tonoike, T.; Muroya, T.; Yoshida, K.; Ozaki, N. Age of Onset Has Limited Association with Body Mass Index at Time of Presentation for Anorexia Nervosa: Comparison of Peak-Onset and Late-Onset Anorexia Nervosa Groups. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 61, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resmark, G.; Herpertz, S.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Zeeck, A. Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa—New Evidence-Based Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerich, H.; Lewis, Y.D.; Conti, C.; Mutwalli, H.; Karwautz, A.; Sjögren, J.M.; Uribe Isaza, M.M.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M.; Aigner, M.; McElroy, S.L.; et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines Update 2023 on the Pharmacological Treatment of Eating Disorders. World J. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Hay, P.; Schmidt, U. Anorexia Nervosa: Aetiology, Assessment, and Treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Zipfel, S.; Micali, N.; Wade, T.; Stice, E.; Claudino, A.; Schmidt, U.; Frank, G.K.; Bulik, C.M.; Wentz, E. Anorexia Nervosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayrolles, A.; et al. Early-Onset Anorexia Nervosa: A Scoping Review and Management Guidelines. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, L.I.; Wilms, S.; Föcker, M.; Dalhoff, A.; Müller, J.M.; Wessing, I. Influence of Identity Development on Weight Gain in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 887588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoli, M.; Esposito, C.M.; Ceresa, A.; Di Paolo, M.; Legnani, F.; Pan, A.; Ferrari, L.; Bollati, V.; Monti, P. Biomarkers Associated with Antidepressant Response and Illness Severity in Major Depressive Disorder: A Pilot Study. Pharmacol. Rep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J. Eating Disorders and Dietary Supplements: A Review of the Science. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savino, G.; Valenti, L.; D'Alisera, R.; et al. Dietary Supplements, Drugs and Doping in the Sport Society. Ann. Ig. 2019, 31, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, O.; Tamai, H.; Fujita, M.; et al. Vascular Responses to Angiotensin II in Anorexia Nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 1993, 34, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torosyan, N.; Visrodia, P.; Torbati, T.; Minissian, M.B.; Shufelt, C.L. Dyslipidemia in Midlife Women: Approach and Considerations during the Menopausal Transition. Maturitas 2022, 166, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohwada, R.; Hotta, M.; Oikawa, S.; Takano, K. Etiology of Hypercholesterolemia in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006, 39, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Fitzner, D.; Bosch-Queralt, M.; Weil, M.T.; Su, M.; Sen, P.; Ruhwedel, T.; Mitkovski, M.; Trendelenburg, G.; Lütjohann, D.; et al. Defective Cholesterol Clearance Limits Remyelination in the Aged Central Nervous System. Science 2018, 359, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertile, R.A.N.; Brigden, R.; Raman, V.; Cui, X.; Du, Z.; Eyles, D. Vitamin D: A Potent Regulator of Dopaminergic Neuron Differentiation and Function. J. Neurochem. 2023, 166, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevione, F.; Martini, M.; Longo, P.; Toppino, F.; Musetti, A.; Amodeo, L.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Panero, M. Role of Parental Educational Level as Psychosocial Factor in a Sample of Inpatients with Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1408695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagielska, G.; Kacperska, I. Outcome, Comorbidity and Prognosis in Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panero, M.; Marzola, E.; Tamarin, T.; Brustolin, A.; Abbate-Daga, G. Comparison between Inpatients with Anorexia Nervosa with and without Major Depressive Disorder: Clinical Characteristics and Outcome. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westmoreland, P.; Krantz, M.J.; Mehler, P.S. Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrașcu, M.C.; et al. Anorexia Nervosa: COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldiroli, A.; La Tegola, D.; Manzo, F.; Scalia, A.; Affaticati, L.M.; Capuzzi, E.; Colmegna, F.; Argyrides, M.; Giaginis, C.; Mendolicchio, L.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nexo, E.; Parkner, T. Vitamin B12-Related Biomarkers. Food Nutr. Food Nutr. Bull. 2024, 45 (Suppl. 1), S28–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedosov, S.N.; Brito, A.; Miller, J.W.; Green, R.; Allen, L.H. Combined Indicator of Vitamin B12 Status: Modification for Missing Biomarkers and Folate Status and Recommendations for Revised Cut-Points. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G.; Riva, G. Dysfunctional Bodily Experiences in Anorexia Nervosa: Where Are We? Eat. Weight Disord. 2016, 21, 731–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, S.C.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Touyz, S.; McGregor, I.S.; Maguire, S.; National Eating Disorder Research Consortium. Pharmacotherapy, Alternative and Adjunctive Therapies for Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, M.C.; Sánchez, J.M.; Salazar, A.M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Antipsychotics and Antidepressants in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2021, 50, S0034–S7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovinazzo, S.; Sukkar, S.G.; Rosa, G.M.; et al. Anorexia Nervosa and Heart Disease: A Systematic Review. Eat. Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakers, A.; Cimolai, V. Complementary and Integrative Medicine and Eating Disorders in Youth: Traditional Yoga, Virtual Reality, Light Therapy, Neurofeedback, Acupuncture, Energy Psychology Techniques, Art Therapies, and Spirituality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 32, 421–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoli, M.; Legnani, F.; Mastroianni, M.; Affaticati, L.M.; Capuzzi, E.; Clerici, M.; Caldiroli, A. Effectiveness of Yoga as a Complementary Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Yoga 2024, 17, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).