Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

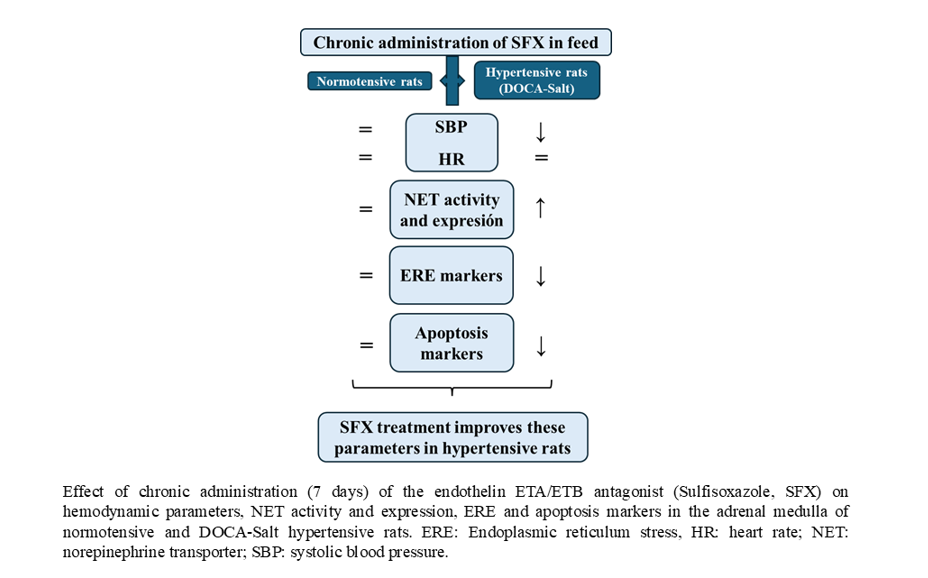

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Norepinephrine Uptake Assay

2.2.2. Western Blot Assay

2.2.3. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy Studies

2.2.5. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated dUTP-Biotin DNA-Nick End Labelling (TUNEL) Assay

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hemodynamic Parameters

3.2. NET Activity and Expression

3.3. Ultrastructural Changes in the Adrenal Medulla Following SFX Administration

3.4. ER Stress Makers Following SFX Administration

3.5. Effect of SFX Treatment on Apoptosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, M-Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L-X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: a novel mechanism and therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.D.; Wu, R.F.; Terada, L.S. ROS signaling and ER stress in cardiovascular disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 63, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhara, M.; Neikirk, K.; Marshall, A.; Hinton, A., Jr.; Kirabo, A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertension and salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almanza, A.; Carlesso, A.; Chintha, C.; Creedican, S.; Doultsinos, D.; Leuzzi, B.; Luis, A.; McCarthy, N.; Montibeller, L.; More, S.; Papaioannou, A.; Püschel, F.; Sassano, M.L.; Skoko, J.; Agostinis, P.; de Belleroche, J.; Eriksson, L.A.; Fulda, S.; Gorman, A.M.; Healy, S.; Kozlov, A.; Muñoz-Pinedo, C.; Rehm, M.; Chevet, E.; Samali, A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling – from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019, 286(2), 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Gu, R.; Han, R.; Li, Z.; Xu, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A.P.; Hyndman, K.A.; Dhaun, N.; Southan, C.; Kohan, D.E.; Pollock, J.S.; Pollock, D.M.; Webb, D.J.; Maguire, J.J. Endothelin. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 357–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enevoldsen, F.C.; Sahana, J.; Wehland, M.; Grimm, D.; Infanger, M.; Krüger, M. Endothelin receptor antagonists: status quo and future perspectives for targeted therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.; Yanagisawa, M. Endothelin: 30 Years from discovery to therapy. Hypertension 2019, 74, 1232–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaun, N.; Webb, D.J. Endothelins in cardiovascular biology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.M.; Sudano, I.; Ghiadoni, L.; Masi, L.; Taddei, S. Interactions between sympathetic nervous system and endogenous endothelin in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 2011, 57, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, E.L.; Pollock, D.M. Endothelin system in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 2024, 81, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, G.; Bouvier, M.; de Champlain, J. Enhanced sympathoadrenal reactivity to haemorrhagic stress in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 1989, 7, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.L.; Haywood, J.R.; Hinojosa-Laborde, C. Role of the adrenal medullae in male and female DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 1998, 31 1 Pt 2, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Jiménez, R.; Sánchez, M.; Zarzuelo, M.J.; Galindo, P.; Quintela, A.M.; LópezSepúlveda, R; Romero, M.; Tamargo, J.; Vargas, F.; Pérez-Vizcaíno, F.; Duarte, J. Epicatechin lowers blood pressure, restores endothelial function, and decreases oxidative stress and endothelin-1 and NADPH oxidase activity in DOCA-salt hypertension. J. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52(1), 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohan, D.; Rossi, N.F.; Inscho, E.W.; Pollock, D.M. Regulation of blood pressure and salt homeostasis by endothelin. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.S.; Andersen, J.; Jørgensen, T.N.; Sørensen, L.; Eriksen, J.; Loland, C.J.; Strømgaard, K.; Gether, U. SLC6 Neurotransmitter transporters: Structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 585–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, D.P.; Blakely, R.D. Kinase-dependent regulation of monoamine neurotransmitter transporters. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 888–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, L.D.; Ramamoorthy, S. Role of phosphorylation of serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in animal behavior: Relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, C.; Jordan, J. Norepinephrine transporter function and human cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 303, H1273–H1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrwein, E.A.; Novotny, M.; Swain, G.M.; Parker, L.M.; Esfahanian, M.; Spitsbergen, J.M.; Habecker, B.A.; Kreulen, D.L. Regional changes in cardiac and stellate ganglion norepinephrine transporter in DOCA-salt hypertension. Auton. Neurosci. 2013, 179(1-2), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Iwai, C.; Qin, F.; Liang, C-S. Norepinephrine induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and downregulation of norepinephrine transporter density in PC12 cells via oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H2381–H2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C-S. Cardiac sympathetic nerve terminal function in congestive heart failure. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28(7), 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, S.I.; Schmipp, J.; Rossi, A.H.; Bianciotti, L.G.; Vatta, M.S. Regulation of the neuronal norepinephrine transporter by endothelin-1 and -3 in the rat anterior and posterior hypothalamus. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 53, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramoff, T.; Guil, M.J.; Morales, V.P.; Hope, S.I.; Soria, C.; Bianciotti, L.G.; Vatta, M.S. Enhanced assymetrical noradrenergic transmission in the olfactory bulb of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramoff, T.; Guil, M.J.; Morales, V.P.; Hope, S.I.; Höcht, C.; Bianciotti, L.G.; Vatta, M.S. Involvement of endothelins in deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt hypertension through the modulation of noradrenergic transmission in the rat posterior hypothalamus. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100.6, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guil, M.J.; Schöller, M.I.; Cassinotti, L.R.; Biancardi, V.C.; Pitra, S.; Bianciotti, L.G.; Stern, J.E.; Vatta, M.S. Role of endothelin receptor type A on catecholamine regulation in the olfactory bulb of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats: Hemodynamic implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 165527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinotti, L.; Guil, M.; Bianciotti, L.; Vatta, M. Role of brain endothelin receptor type B (ETB) in the regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase in the olfactory bulb of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 21(4), 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchino, T.; Sanyal, S.N.; Yamane, M.; Kaku, T.; Takebashi, S.; Shimaoka, T.; Shimada, T.; Noguchi, T.; Ono, K. Rescue of Pulmonary Hypertension with an Oral Sulfonamide Antibiotic Sulfisoxazole by Endothelin Receptor Antagonistic Actions. Hypertens. Res. 2008, 31, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Champlain, J.; Van Ameringen, MR. Regulation of blood pressure by sympathetic nerve fibers and adrenal medulla in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Circ. Res. 1972, 31(4), 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reims, H.M.; Fossum, E.; Høieggen, A.; Moan, A.; Eide, I.; Kjeldsen, S.E. Adrenal medullary overactivity in lean, borderline hypertensive young men. Am. J. Hypertens. 2004, 17(7), 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, V.T.; Hammes, S.R. Recent Insights on Circulating Catecholamines in Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Freel, E.M.; Perry, C.G.; Dominiczak, A.F. Disorders of blood pressure regulation-role of catecholamine biosynthesis, release, and metabolism. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2012, 14, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.L.; Haywood, J.R.; Hinojosa-Laborde, C. Endothelin enhances and inhibits adrenal catecholamine release in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2000, 35 1 Pt 2, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.S.; Xie, H.H.; Shen, F.M.; Cai, G.J.; Su, D.F. Blood pressure variability, cardiac baroreflex sensitivity and organ damage in experimentally hypertensive rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005, 32(7), 545–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basting, T.; Lazartigues, E. DOCA-salt hypertension: an update. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19(4), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.K.; Johnston, J.G.; Young, C.M.; Torres Rodriguez, A.A.; Jin, C.; Pollock, D.M. Endothelin B receptors impair baroreflex function and increase blood pressure variability during high salt diet. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2021, 232, 102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hana, S.; Bala, N.B.; Sadib, G.; Usanmaz, S.E.; Tuglu, M.M.; Uludag, M.O.; Demirel-Yilmaz, E. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress protected DOCA-salt hypertension-induced vascular dysfunction. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 113, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnier, M. Update on Endothelin Receptor Antagonists in Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostov, K. The Causal Relationship between Endothelin-1 and Hypertension: Focusing on Endothelial Dysfunction, Arterial Stiffness, Vascular Remodeling, and Blood Pressure Regulation. Life 2021, 11, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxwalla, M.; Matwyshyn, G.; Puppala, B.L.; Andurkar, S.V.; Gulati, A. Involvement of imidazoline and opioid receptors in the enhancement of clonidine-induced analgesia by sulfisoxazole. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88(5), 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, H.; Safa, R.; Chidlow, G.; Osbornem, N.N. Sulfisoxazole, an endothelin receptor antagonist, protects retinal neurones from insults of ischemia/reperfusion or lipopolysaccharide. Neurochem. Int. 2006, 48, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E-J; Lee, C-H; Moon, P-G; et al. Sulfisoxazole inhibits the secretion of small extracellular vesicles by targeting the endothelin receptor A. Nature Commun 2019, 10, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backs, J; Bresch, E; Lutz, M; Kristen, AV; Haass, M. Endothelin-1 inhibits the neuronal norepinephrine transporter in hearts of male rats. Cardiovasc Res 2005, 67(2), 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, CN. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Exp Physiol 2017, 102.8, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, NB; Hana, S; Kiremitcib, S; Sadic, G; Uludaga, O; Demirel-Yilmazd, E. Hypertension-induced cardiac impairment is reversed by the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Pharm Pharmacol 2019, 71, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, NB; Han, S; Kiremitci, S; Uludag, MO; Demirel-Yilmaz, E. Reversal of deleterious effect of hypertension on the liver by inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 2243–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y-H; Zheng, C-M; Chou, Ch-L; et al. Therapeutic effect of endothelin-converting enzyme inhibitor on chronic kidney disease through the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A. Endothelin-1–induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2013, 346, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, HP; Zhang, Y; Ron, D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 1999, 397, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J; Kim, K; Kim, J-H; Park, Y. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in cardiovascular disease and exercise. Int J Vasc Med 2017, 2049217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S; Binder, P; Fang, Q; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart: insights into mechanisms and drug targets. Br J Pharmacol 2018, 175, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S; Ding, H; Li, Y; Zhang, X. Molecular mechanism underlying the role of the XBP1s in cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2022, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufey, E; Sepúlveda, D; Rojas-Rivera, D; Hetz, C. Cellular mechanisms of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in health and disease. 1. An overview. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2017, 307, C582–C594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).