1. Introduction

Systemic arterial hypertension (SAH) is characterized by persistently high blood pressure in the systemic arteries and is the main risk factor for developing cardiovascular diseases. The etiology of SAH is multifactorial and is associated with various factors, including genetic predisposition, behavioral factors such as high sodium and fat consumption, and social factors like emotional stress. Strategies to counteract the effects of SAH include lifestyle modifications, medications, and emerging important research worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4].

During hypertension, structural and biochemical alterations occur, damaging arteries, the endothelium, and increasing vascular inflammation. These changes are associated with an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (∙O₂⁻) and peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻). One of the main biochemical modifications due to excess ROS is the uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase, caused by the oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH₄) to dihydrobiopterin (BH₂), which generates an uncoupling between oxygen and the oxidation process of L-arginine. This results in the release of superoxide anion and a decrease in the production of nitric oxide (NO) [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7], perpetuating the disease and increasing damage.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) is a regulator of NO levels and Ca²⁺ flux across cell and mitochondrial membranes in several cell types, including those of the cardiovascular system. It is a functional part of organelles such as mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus, and the rough endoplasmic reticulum. TRPV1 may be involved in the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane [

8,

9], as well as in the opening and closing of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), thereby regulating pro-apoptotic proteins, among other functions [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Depending on its location, whether neuronal or non-neuronal, TRPV1 is exposed to various physical and chemical stimuli that can activate or inactivate the receptor (e.g., its mediation of nociception) [

12,

14,

15,

16]. Capsaicin (CS), the active component of chili peppers, is the main exogenous agonist used as a tool to study TRPV1 functionality [

1,

17,

18].

An imbalance in Ca²⁺ flux in the heart is characteristic of endothelial dysfunction, leading to decreased bioavailability of NO, ischemia, increased endothelin-1, angiotensin II, increased ROS, apoptosis, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Therefore, TRPV1 activation may play an important role in the heart. The beneficial effects of TRPV1 activation by capsaicin include increased release of neuropeptides such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) [

1,

17], which, together with NO, have important vasodilatory properties that also depend on proper mitochondrial function. This receptor may participate in Ca²⁺ control even in conditions of systemic arterial hypertension.

In this context, mitochondria play a fundamental role as regulators of intracellular calcium levels. Thus, the expression and activation of TRPV1 could contribute to this mechanism directly or indirectly, as other authors have proposed.

Several studies have suggested that TRPV1 may constitute a therapeutic target for pain sensation and may play an important role in diseases such as hypertension, breast cancer, and, more recently, cardiovascular diseases, among others [

13,

16,

19].

In this work, we studied the possibility that the activation of TRPV1 at the systemic level might participate in heart protection against events that generate functional and tissue damage through the regulation of mitochondrial function in hypertensive rats. Our hypothesis was that TRPV1 activation protects mitochondrial function and, therefore, reduces heart damage in a hypertension model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

All reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MI, USA.

Capsaicin (CS) [8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide], capsazepine (CZ) (CS antagonist) [N-(2-(4-chlorophenyl)ethyl)-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-7,8-dihydroxy-2H-2-benzazepine-2-carbothioamide], and L-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) were used in this study.

2.2. Animals

Experimental animals (Wistar rats weighing 300–350 g) were obtained from the animal facilities of the National Institute of Cardiology Ignacio Chávez in Mexico City, with approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee for the use and care of experimental animals.

Animals were kept under standard light/dark conditions (12 hours light/dark cycle) at a controlled temperature (25 ± 3°C) and humidity (50 ± 10%). They were provided ad libitum access to water and a standard diet (LabDiet 5026, PMI Nutrition International, Richmond, IN, USA). All procedures followed the guidelines established by the Federal Regulation for Experimentation and Animal Care (SAGARPA, NOM-062-ZOO-1999, Mexico).

2.3. Experimental Groups

Animals were divided into 5 groups, with 8 animals per group, as follows: 1) Control (C), 2) Hypertensive (H), 3) H+Capsaicin (H+CS), 4) H+Capsazepine (H+CZ), and 5) H+CS+CZ.

Mean arterial pressure was measured in all groups using a non-invasive method, with a pneumatic pressure monitor placed at the base of the animal’s tail, at the beginning and end of treatments [

20].

Systemic arterial hypertension in the rats (groups 2–5) was induced by adding L-NAME (200 mg/L) to their drinking water for 40 days [

21,

22]. On day 36 of L-NAME treatment, the following treatments were applied for 4 days prior to the experiment: Group 3 received a daily subcutaneous dose of CS (5 mg/kg body weight) [

16]. Group 4 received a subcutaneous dose of CZ (6 mg/kg body weight). Group 5 received a combination of CS and CZ, with CZ applied first, followed by CS one hour later.

L-NAME treatment continued throughout the experiment, and the animals were euthanized on day 40 [

23]. Reagents CS and CZ were diluted in ethanol and water in a 2:1 ratio.

2.4. Isolated and Perfused Heart (Langendorff Method)

The animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg), and the surgery was performed as follows: a tracheotomy was performed to insert a cannula into the trachea, which was connected to an artificial ventilator to maintain lung function during the surgery. The heart was exposed via thoracotomy, and the ascending aorta was identified and ligated with a silk thread. The heart was then removed and placed in a cold (4 oC) Krebs–Henseleit solution (K–H buffer, mM: NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl₂ 2.0, MgSO₄ 1.2, KH₂PO₄ 1.2, EDTA 0.5, NaHCO₃ 25, glucose 11, pH 7.4, 37°C, 95% O₂ and 5% CO₂), to stop mechanical activity.

After a few seconds, the aorta was connected to a perfusion cannula, and the Krebs solution was retrogradely perfused at 37°C. The flow rate was set at 13 mL/min using a peristaltic pump (SAD22, Grass Instruments Co., Quincy, MA, USA), with a 30-minute adaptation period. The heart was adapted with a flow of 25 mL/min for 5 minutes, followed by 13 mL/min for 25 minutes. Heart rate (HR) was maintained at 312–324 beats per minute using a Grass stimulator (U7, Grass Instruments Co., Quincy, MA, USA). Coronary flow (F) was held at 13 mL/min using the peristaltic pump throughout the experiment.

Parameters such as left intraventricular pressure (LIVP) were recorded using a Grass hydropneumatic pressure transducer connected to a latex balloon inserted through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. An internal pressure of 5–10 mmHg (diastolic pressure) was applied. Perfusion pressure (PP) was also recorded, with a range of 55–70 mmHg considered as an inclusion criterion. Using HR and LIVP values, cardiac work (CW) was calculated as HR × LIVP = CW. Coronary vascular resistance (CVR) was calculated as PP/F = CVR [

24].

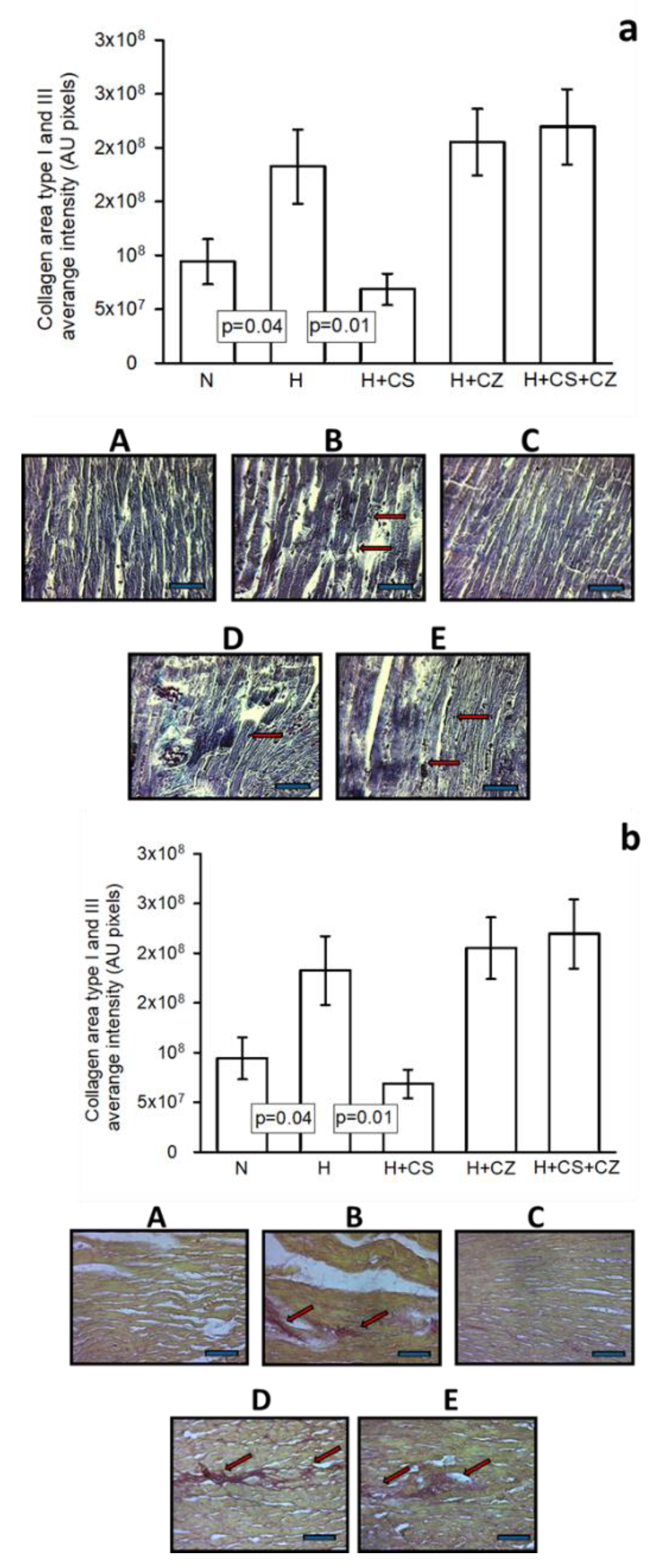

2.5. Histological Sections

After perfusion, hearts from each group were fixed by immersion in 10% formaldehyde until histological sections were prepared. Sections were processed using conventional histological methods with Masson’s trichrome stain. Histological sections were analyzed using a Carl Zeiss light microscope (Carl Zeiss Axio Imager Z2, West Germany) with an EC Plan-Neofluar 10x objective, connected to an HP Z800 computer and HP ZR30W screen. Microphotographs were analyzed by densitometry using the SigmaScan Pro 5 Image Analysis software. Density values are expressed in units of pixels.

In another analysis, the Syrian red staining technique was used in groups: (A) Control (C), (B) Hypertensive (H), (C) H+CS, (D) H+CZ, and (E) H+CS+CZ. Representative photomicrographs of cardiac tissue were obtained at 20x magnification after conventional histological processing.

2.6. Isolation of Mitochondria

Six hearts from each group were collected for mitochondrial studies. The heart was placed in an isolation buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.3, and stored at 4°C. The heart was minced and incubated for 10 minutes in isolation buffer with 1 mg/mL proteinase Type XXIV (Sigma-Aldrich). It was then centrifuged at 8,000 x g for 10 minutes. The pellet was homogenized in a glass Potter-type homogenizer with isolation buffer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 600 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove connective tissue and cellular debris. The supernatant was recovered and centrifuged at 8,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to obtain the mitochondrial fraction. The resulting pellet was suspended in isolation buffer with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 10 minutes at 4°C. After incubation, 20 mL of isolation buffer was added, and the mixture was centrifuged again at 8,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The mitochondrial fraction was suspended in 1 mL of the same buffer without BSA and stored at 4°C for the duration of the experiments [

25].

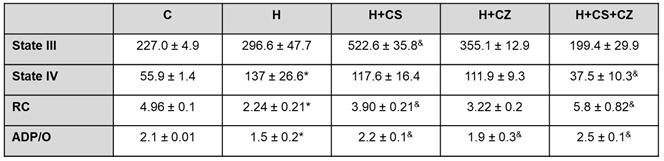

2.7. Mitochondrial Function

2.7.1. Mitochondrial Oxygen Uptake

Mitochondrial respiratory rates were measured with a Clark-type O₂ electrode by incubating 1 mg protein/mL of fresh mitochondria at 30°C in an air-saturated medium containing 125 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH), 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM K₂HPO₄. Oxygen uptake was assessed in forward electron transport fluxes by energizing mitochondria with glutamate/malate (5/3 mM). ADP (250 μM) was added to evaluate state III, and state IV corresponded to oxygen uptake after ADP exhaustion [

26].

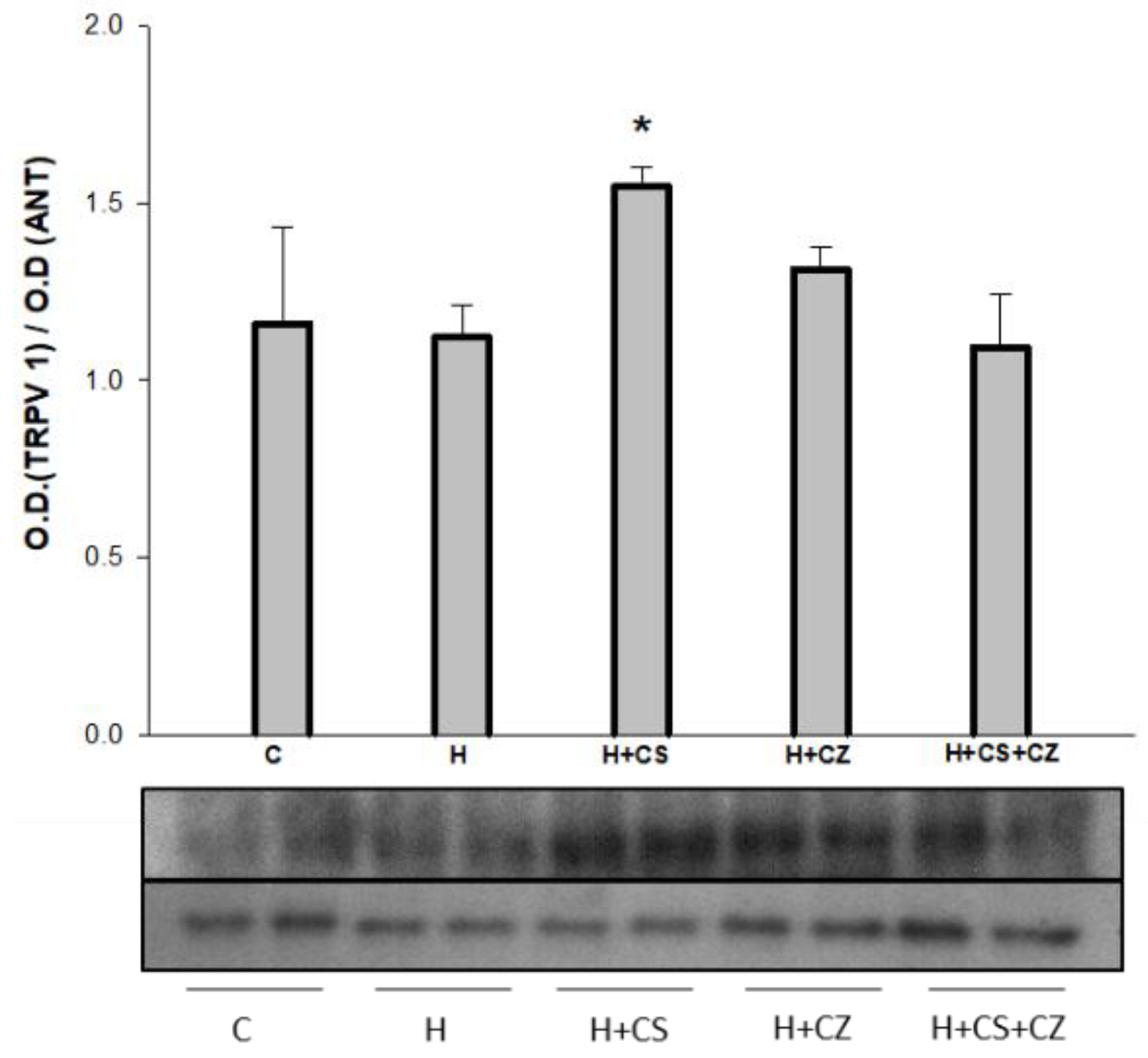

2.7.2. Apoptotic Protein Markers

Eighty micrograms of mitochondrial protein were analyzed by Western blot to determine the abundance of Cyt c, Bax, and Apaf-1 as apoptotic markers. The TRPV1 proteins were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (BioRad). Membranes were incubated with a 1% casein buffer (BioRad) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, primary rabbit polyclonal anti-Cyt (1:3000 dilution) (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-APAF1 (1:1000 dilution) (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-BAX (1:1000 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit monoclonal anti-TRPV1 (1:2000 dilution) (Sigma) antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. For the loading control, rabbit polyclonal anti-ANT (1:1000 dilution) (Abcam) was used. The PVDF membranes were washed with TBS-Tween buffer (Tris 150 mM, NaCl 50 mM, pH 7.4, 1% Tween 20) and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies at a 1:20,000 dilution, respectively. Proteins on the membrane were detected by chemiluminescence using the commercial SuperSignal™ Western Blot Enhancer (Thermo Fisher) and Kodak BioMax radiographic plates. Bands obtained on the plate corresponding to each of the proteins of interest were analyzed using ImageJ software.

2.8. Catalase Activity

For catalase activity detection, 60 μg of mitochondrial protein were spotted onto 8% native polyacrylamide gels. Proteins in their native form were electrophoretically separated in a Tris-glycine buffer (pH 8.3) at 100 V for 4 hours at 4°C. Gels were then washed with distilled water for 10 minutes under constant shaking. Afterward, gels were incubated with 20 mM H

2O

2 for 10 minutes. The gels were then incubated with a solution of 1% K

3Fe (CN)

6 and 1% FeCl

3•6H

2O (v/v) for 10 minutes in the dark. After this, gels were stained blue, except for the bands corresponding to catalase activity [

27].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey post hoc test was applied using the SigmaPlot program version 11 (Jandel Scientific, San José, CA, USA). For statistical analyses of mitochondrial samples, Student’s t-test was performed using SigmaPlot version 11 (Systat Software Inc., CA, U.S.A.).

4. Discussion

Various animal models have been proposed with protocols that mimic the complications of systemic arterial hypertension (SAH), offering potential experimental solutions due to the variable origins of SAH. Hypertension induced by high doses of L-NAME constitutes a model in which the three isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS)—neuronal, inducible, and endothelial—are nonspecifically inhibited, leading to decreased nitric oxide (NO) levels [

3,

7,

22,

23,

28].

In this study, we used capsaicin, a potent exogenous agent, to investigate the role of TRPV1 in myocardial protection in hypertensive rats. We analyzed the heart’s ability to recover from the damage induced by hypertension through TRPV1 activation by capsaicin. The aim of this work was to determine whether TRPV1 might contribute to myocardial protection by regulating mitochondrial metabolism in hypertensive rats. As expected, the activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin (CS) had a protective effect on cardiac work, preventing the damage caused by hypertension. Under hypertensive conditions, the cardiac work decrease 20% compared to the control group. In comparation with H group, CS protects against the hypertension damage and the cardiac work was recovered. In addition, CZ hasn’t any effect on the recovery of cardiac work and the combination of CZ+CS have an inhibitory effect on the CS protection.

The protective effect was also evident in the significant increase in coronary vascular resistance (CVR) in the H group, whereas in the H+CS group, CVR decreased significantly due to TRPV1 activation. However, CZ and the combination of CS+CZ also improved CVR. This behavior in the CZ and CS+CZ groups was also observed in the mitochondrial parameters and could be attributed to the concentration of CZ used or the antioxidant characteristics of this molecule [

18,

29].

The findings of this study are consistent with observations made in cardiac tissue, where no damage was observed in hypertensive rats treated with CS when compared to control and hypertensive hearts. We believe that the beneficial effect on the heart is, in part, due to TRPV1 activation by CS, as this molecule reduces oxidative stress, regulates calcium flux, and restores the NO pathway by increasing its bioavailability, as supported by our previous studies [

19]. Furthermore, we observed a decrease in collagen fibers in the ventricular tissue in the H+CS group, which played a key role in preventing impairment of cardiac mechanical function.

Mitochondrial metabolism provides most of the energy consumed by cells such as cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction, characterized by a loss of efficiency in the electron transport chain and reduced ATP production, is a hallmark of many chronic diseases, including hypertension [

30]. In addition, mitochondria play a central role in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and their dysfunction promotes an increase in ROS, contributing to oxidative stress and associated pathologies, including hypertension [

9]. Our results show that both respiratory control and ATP synthesis were significantly decreased in the H group; however, both parameters were restored in the H+CS group, which may be directly linked to TRPV1 activation. This finding supports the idea that TRPV1 activation improves mitochondrial metabolism in the context of hypertension, reflected in the maintenance of ATP synthesis. These observations align with those reported in primary cardiomyocytes, where the activation of TRPV1 by CS regulates the mitochondrial transmembrane potential through an interaction with calcineurin, suggesting a cardioprotective mechanism [

14].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is closely associated with oxidative stress, which is directly linked to the release of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from the mitochondria into the cytosol, initiating cell death through apoptosis. Cyt c is released from the inner mitochondrial membrane into the intermembrane space when oxidized by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and can subsequently exit into the cytosol due to the opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) or through pores formed by BAX/BAK. Apaf-1 is another protein that leaves the mitochondria and, together with Cyt c and caspase-9, forms the apoptosome. In hypertensive (H) rats, we observed a significant decrease in Cyt c content in the mitochondria compared to the control group, suggesting that Cyt c may have been released into the cytosol, contributing to the apoptotic process. This finding is consistent with other studies showing increased apoptosis in cardiomyocytes from genetically hypertensive rats [

31].

In the mitochondria of animals treated with capsaicin (CS), Cyt c and Apaf-1 content were maintained at control levels, while no significant changes were observed in the H+CZ and H+CS+CZ groups. Additionally, a significant decrease in BAX content was observed in the mitochondria of the H+CS group compared to the H group, indicating that BAX was not being inserted to form pores that allow the release of pro-apoptotic proteins. These results suggest that activation of TRPV1 by CS protects the mitochondria not only by improving their metabolism but also by inhibiting pro-apoptotic signals in the heart of hypertensive rats. Similar protective effects of TRPV1 activation against apoptosis have been reported in ischemia and reperfusion models, where decreased BAX insertion and increased Bcl-2 levels were observed, often associated with activation of the AKT/ERK pathway [

32].

The increased oxygen consumption observed in the H+CS mitochondria during state III of mitochondrial respiration could result from uncoupling, which is mediated by uncoupling proteins (UCPs) that are overexpressed under oxidative stress conditions. Oxidative stress is common in pathologies such as hypertension [

9]. UCPs, particularly UCP2 and UCP3, are expressed in the heart and regulate the generation of superoxide anions. It has been proposed that proton leakage across UCPs, rather than across ATP synthase, accelerates the reduction of molecular oxygen to water, preventing its leakage and formation of superoxide anion.

TRPV1 and thermogenic UCP-1 (for example) are involved in the regulation of body temperature and may also influence mitochondrial activity through mechanisms regulating Ca²⁺ flux, NO synthesis, and ∙O₂⁻ formation, which controls mitochondrial ROS production. The interaction between TRPV1 and UCP-1 has primarily been studied in mouse models of obesity, where inhibition of both proteins has been attributed to their thermoregulatory roles. TRPV1 has also been shown to reduce blood glucose levels, and treatment with CS increases UCP-1 expression in adipocytes [

1]. More recently, the control of ROS in mitochondria has been linked to the involvement of UCP-2 and UCP-3 proteins [

33].

Moreover, respiratory control (RC) with CS treatment showed a significant improvement, and although CZ treatment showed a tendency to decrease RC, interestingly, RC improved significantly in the CS+CZ group. The beneficial effects on mitochondrial activity in the H+CZ and H+CS+CZ groups could be attributed to the antioxidant effects of CZ. This is because both CS and CZ, which contain phenolic groups, act as free radical scavengers and superoxide anion quenchers, helping to reduce ROS damage due to their antioxidant properties [

34]. Another possibility is that the concentration of CZ used did not block the actions of CS, but only inhibited it.

Hypertension impacts mitochondrial function (

Table 1), as evidenced by the decrease in RC and ATP synthesis. The increased acceleration in oxygen consumption was not corrected by CZ treatment, but CS treatment significantly improved mitochondrial function in the H group. Unexpectedly, mitochondrial function was restored to control levels in the CS+CZ group, and ATP synthesis was restored to control values.

On the other hand, increased ROS directly affects the activity of antioxidant enzymes, leading to oxidative stress. Our results show that catalase activity was significantly increased in the heart mitochondria of hypertensive animals, and treatment with CS significantly decreased the activity of this enzyme. In the H+CZ and H+CS+CZ groups, catalase activity remained at levels similar to those in the H group. The increase in catalase activity is likely due to increased superoxide anion production in the mitochondria of H animals. CS treatment decreased superoxide anion generation through mitochondrial uncoupling, as previously discussed, thereby reducing the need to activate the catalase antioxidant system. This behavior in catalase activity has also been observed in renal hypertension models, where it is associated with a decrease in GPX activity, responsible for eliminating peroxides [

35].

Our results suggest that TRPV1 plays a crucial role in regulating mitochondrial function, offering protective effects to the myocardium. Notably, its expression was observed in mitochondria. However, the precise mechanism behind its expression remains unclear. Further studies are needed to explore the potential interaction between TRPV1, UCP-2, and Sirt3, a mitochondrial protein involved in ROS regulation. These investigations could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the protective mechanisms TRPV1 may offer in the context of hypertension

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Angelica Ruíz-Ramírez and Juan Torres-Narváez; Investigation, Angelica Ruíz-Ramírez, Vicente Castrejón-Téllez, Verónica Guarner-Lans and Juan Torres-Narváez; Methodology, Vicente Castrejón-Téllez, Leonardo del Valle-Mondragón, Israel Pérez-Torres, Oralia Medina-Rodríguez, Rodrigo Velázquez-Espejel, Álvaro Vargas-González, Pedro Flores-Chávez and Raúl Martínez-Memije; Resources, Oralia Medina-Rodríguez, Rodrigo Velázquez-Espejel and Álvaro Vargas-González; Software, Leonardo del Valle-Mondragón, Israel Pérez-Torres, Pedro Flores-Chávez and Raúl Martínez-Memije; Supervision, Angelica Ruíz-Ramírez, Vicente Castrejón-Téllez, Israel Pérez-Torres and Juan Torres-Narváez; Writing – original draft, Angelica Ruíz-Ramírez and Juan Torres-Narváez; Writing – review & editing, Angelica Ruíz-Ramírez, Vicente Castrejón-Téllez, Verónica Guarner-Lans and Juan Torres-Narváez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.