1. Introduction

Aging is a significant risk factor for urological diseases, including underactive bladder and impaired bladder compliance, both of which are irreversible conditions associated with the development of tissue fibrosis.[1−3] Similarly, chronic radiation cystitis (RC) — a long-term bladder complication of pelvic radiation therapy (PRT)—shares similar pathological features. As RC advances, patients may develop fibrosis, vascular fragility, and severe hemorrhagic events.[4−6] Radiation exposure is known to accelerate aging phenotypes, particularly through the induction of cellular senescence, and promote fibrosis and tissue dysfunction across various tissues, including the bladder.[7−11] These parallels suggest that aging biology may play an underrecognized role in RC pathogenesis.

Cellular senescence is a fundamental hallmark of aging. It refers to a state of cell-cycle arrest.[12−14] triggered by diverse stressors, including DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress.[15−17] Although senescence initially serves protective functions, preventing the proliferation of damaged cells, suppressing tumors, aiding development, promoting wound healing, supporting tissues remodeling, and developing vasculature, its persistence becomes maladaptive. Accumulated senescent cells disrupt tissue homeostasis, promote chronic inflammation, and contribute to age-related diseases.[18−21] These dual roles underscore the importance of understanding how senescence is regulated in pathological contexts such as RC.

Senescent cells can acquire a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) characterized by the secretion of a complex mixture of inflammatory proteins, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and proteases. These factors can interfere with the surrounding tissue by fostering inflammation, recruiting immune cells, and prompting tissue remodeling. Although SASP initially prevents the proliferation of damaged cells, and facilitate short-term tissue repair, their chronic expression promotes sustained inflammation, aberrant immune cell recruitment, extracellular matrix degradation, and tissue dysfunction. Persistent SASP signaling is increasingly recognized as a driver of fibrosis and chronic inflammatory disease, positioning it as a potential contributor to RC progression.[18,19,22,23] RC presents as a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from mild dysuria and increased urinary frequency to severe hematuria and bladder dysfunction. Its pathophysiology involves complex inflammatory responses, vascular damage, and fibrosis.[4,5,24]. Despite technological advances in radiation delivery and supportive care, RC remains a significant clinical challenge, with no reliable diagnostic, preventive, or therapeutic options, hereby profoundly impacting patients` quality of life.[24−27] A deeper mechanistic understanding is therefore essential to inform new therapeutic strategies. RC develops in patients receiving PRT for malignancies such as prostate, cervical or colorectal cancer. Clinically, RC is characterized by three phases: an acute phase lasting only several weeks after treatment completion, a symptom-free latent phase, and a chronic phase that can start months to years after PRT. The reported incidence of RC varies significantly due to differences in study design, patient populations, and definitions of cystitis.[28−30] Acute RC is relatively common, with incidences as high as 50% during or shortly after treatment. Chronic RC, though less frequent, affects up to 15% of patients treated with PRT and may manifest months to years after treatment completion. Risk is in part influenced by radiation doses, treatment duration, and patient age, suggesting that both therapy-related and host-related factors shape disease susceptibility.

Using a CT-guided, multi-beam preclinical model of bladder-targeted irradiation, we previously demonstrated that mice develop progressive bladder fibrosis accompanied by functional impairments consistent with human RC.[31,32] Transcriptomic profiling revealed marked activation of apoptotic pathways during the acute phase followed by increased inflammatory, and tissue remodeling pathways at chronic stages.[33] However, the latent phase remained largely unexplored. In this study we integrate RNA sequencing to assess the immune cell profiling, inflammatory proteins measurements and bladder functional analysis to define the molecular and immunological mechanisms driving RC progression across all three phases.

We hypothesized that radiation induces persistent bladder senescence and that impaired immune surveillance during the latent phase permits senescent cell accumulation, thereby promoting SASP-driven inflammation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and eventual bladder dysfunction. By characterizing these mechanisms across acute, latent, and chronic phases, we aim to establish a mechanistic framework for RC progression and identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Radiation Cystitis Pre-Clinical Model

This study was conducted with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AL-2020-04; AL-23-02) and in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed, treated, and cared for in an AAALAC-accredited facility. Female C57Bl/6 mice, 8 weeks old, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Harbor, ME) and randomly assigned to either an irradiated or control group (N=5 per group and time point, unless stated otherwise).

Radiation was delivered to the mouse bladder using the Small Animal Radiation Research Platform (SARRP) with a two-beam approach, as previously described.[31] Briefly, anesthesia was induced with 2.5–3% isoflurane via inhalation and maintained at 1.5–2% during the 30-min procedure. Mice were positioned on the SARRP platform, and CT imaging was used to identify the bladder and guide beam positioning. Care was taken to avoid critical structures, including the spinal cord, long bones, colon, and areas where entrance and exit beams could overlap, minimizing off-target damage. Mice received a single 40 Gy dose evenly distributed over two beams using a 5 × 5 mm collimator.

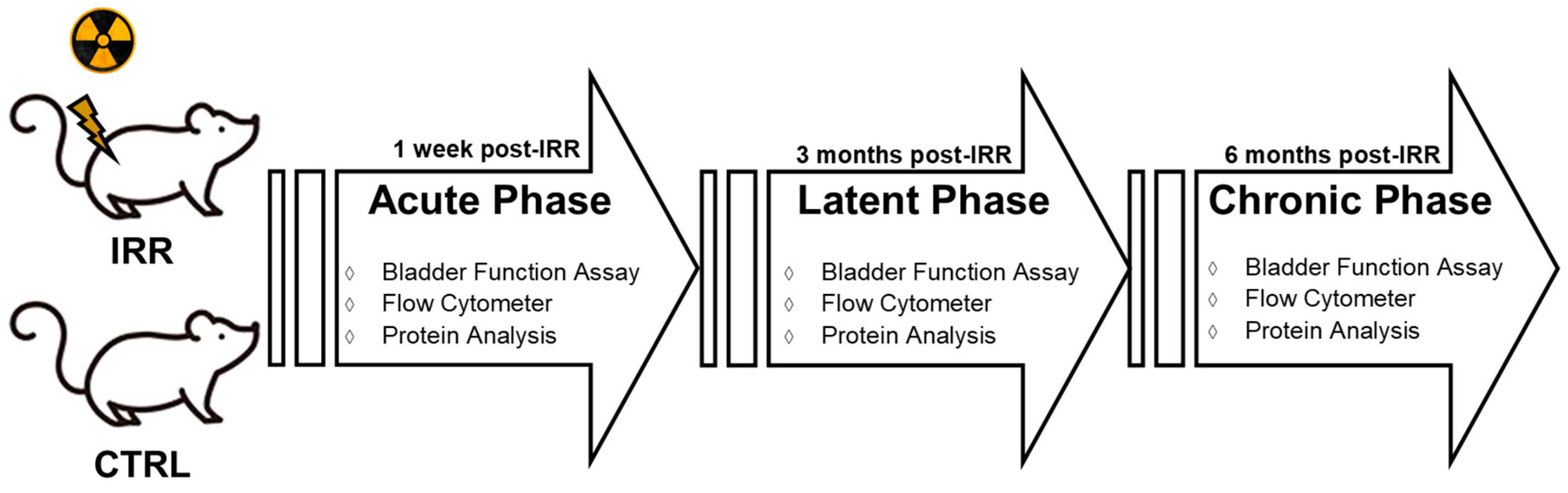

After radiation treatment, mice were placed in a heated recovery cage and returned to standard housing upon full recovery. They were provided with mash and hydrogel for seven days post-treatment. Untreated control mice underwent anesthesia for the same duration as their irradiated counterparts. Bladder function assays were performed at 1 week, 3 months, and 6 months post-IRR to represent acute, latent and chronic phases of RC disease progression. Bladder tissues were collected at each time point (

Figure 1).

2.2. RNA Sequencing

RNA sequencing results for acute and chronic phases were previously published.[33] During that study, bladders from the latent phase (three months post-IRR) were also collected; however, the RNA sequencing data from this phase was neither analyzed nor published. In this report, we present the RNA sequencing data from the latent phase and compare it with the data from the previously published acute and chronic phases. As previously described, samples were processed at the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core.[33] Libraries were constructed and sequenced using the NovaSeq-6000 platform (Illumina) with 151 paired-end or single-end cycles. Adapter sequences were removed with Cutadapt (v2.3), and quality control was performed using FastQC (v0.11.8). Reads were aligned to the GRCm38 reference genome (ENSEMBL) using STAR (v2.6.1b), and gene counts were assigned with RSEM (v1.3.1). Alignment parameters adhered to ENCODE standards for RNA sequencing, and post-alignment quality control was performed to ensure robust data for expression quantification and differential analysis.

2.3. Differential Expression Analysis

Gene expression data was pre-filtered to exclude genes with fewer than 10 counts across all samples. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2, employing a negative binomial generalized linear model. Thresholds were set at a linear fold change >1.5 or <−1.5, with a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR-adjusted p-value <0.05. Data visualization utilized DESeq2 plotting functions and additional R packages (v3.3.3). Genes were annotated with NCBI Entrez GeneIDs and associated text descriptions.

Functional analysis, including pathway activation/inhibition, p-values, and GO-term enrichment, was performed using the iPathwayGuide scoring system (ADVITA Bioinformatics). Two pruning methods were applied to reduce redundancy in GO terms: high specificity pruning, which identifies the most specific terms, and smallest common denominator pruning, which selects terms best summarizing the dataset.

2.4. Immune Cell Profiling

Immune cell profiling was assessed by flow cytometry. Bladders were collected and maintained in MACS Tissue Storage Solution (Miltenyi Biotec) for <12 h at 4 °C until analysis. Tissue samples were processed to single cells using a GentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s protocol for dissociation of mouse kidney using the Multi Tissue Dissociation Kit 2 (Miltenyi Biotec). Dissociated samples were washed and resuspended in Stain Buffer (BD) counted, assessed for viability, and stained with antibodies for CD324 (BD, Catalog# 752470), (BD, Catalog# 752470), CD44 (BD, Catalog# 560568), CD45 (BD, Catalog# 557235), CD31 (BD, Catalog# 553372), CD54 (BD, Catalog# 753779), CD1016 (BD, Catalog# 740471), CD206 (BD, Catalog# 566813), CD3e (BD, Catalog# 558214), CD19 (BD, Catalog# 565473), CD117 (BD, Catalog# 567818), CD127 (BD, Catalog# 565490), and AREG (LS Bio, Catalog# LS-C696945-100) for 30 min at 40 C. Viability was assessed via 7AAD staining. Samples were analyzed on a ZE5 flow cytometer (Bio-Rad), and all analysis was performed via FlowJo (V10.8.1). All presented plots and data were gaited on viable single cells.

2.5. Inflammatory Protein Profiling

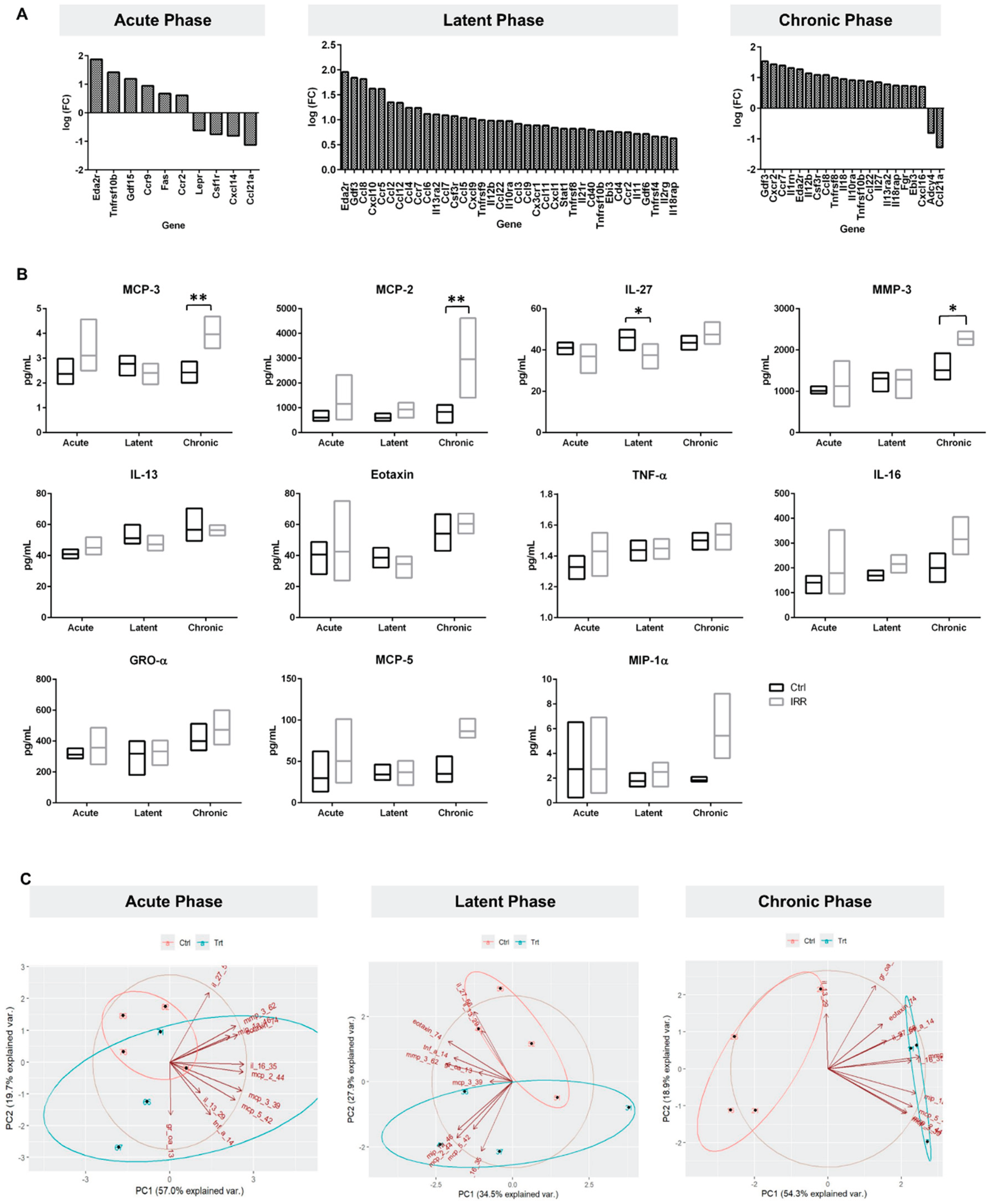

Guided by cytokine and chemokine signatures identified in the RC RNA sequencing data (Figure 4A), a 19-multiplex SASP protein Luminex panel was used to quantify inflammatory mediators associated with senescence [34]. IL-27 was included in the panel due to its established role in immune surveillance and lymphocyte activity.[35,36] All analytes were assessed in bladder tissue lysates collected across acute, latent and chronic phases, along with time-matched controls.

Cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors were measured in bladder tissue lysates using Magnetic Luminex Immunoassay and ELISA, following the manufacturers’ protocols. Irradiated and age-matched control bladders (N=4/group) were harvested at 1-week, 3-months, and 6-months post-treatment and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue lysates were prepared using a commercial Immunoprecipitation Kit (Abcam #ab206996). Briefly, frozen tissues were pulverized with a stainless-steel tissue grinder and resuspended in a non-denaturing cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (50 mg tissue powder per 1 mL buffer). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h, centrifuged (10,000 x g, 5 min, 4˚C) to remove debris, and the supernatant was transferred to fresh tubes. Samples were diluted 1:2 in assay buffer and analyzed in duplicate.

Proteins analyzed included MCP-1 (CCL2), MIP-1β (CCL4), MCP-3 (CCL7), Eotaxin (CCL11), MDC (CCL22), IP-10 (CXCL10), IFN-ɣ, IL-27, TNF-α, MIP-1α (CCL3), RANTES (CCL5), MCP-2 (CCL8), MCP-5 (CCL12), GROα (CXCL1), ICAM-1(CD54), IL-10, IL-16, MMP-3, IL-13 using R&D Systems’ Magnetic Luminex Immunoassay panels. ELISA was used for AREG (R&D Systems #DAR00) quantification. Data acquisition employed a Bio-Plex® Luminex® 200 IS System, with fluorescence intensity measured and converted to protein concentrations using 5-parameter logistic regression. Each plate was run with a standard curve to qualify assay performance.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Cell content and inflammatory protein was analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (GraphPad Prism), with significance set at p < 0.05. Principal inflammatory Component Analysis (PCA) was used to cluster irradiated and control samples using a data set of detect inflammatory proteins in bladder lysate samples.

3. Results

3.1. RC Latent Phase RNA Sequencing

RNA sequencing results for the acute and chronic phases were previously reported.[33] Transcriptional evaluation of latent-phase bladder samples demonstrated high sequencing quality with >30 million uniquely mapped reads per sample. Prior to multiple-testing correction, 68 pathways, 2,261 Gene Ontology (GO) terms, 2 miRNAs, 119 gene upstream regulators, 270 chemical upstream regulators, and 85 diseases were significantly enriched highlighting substantial transcriptomic remodeling during the latent phase.

Significant differentially expressed (SDE) genes were identified using a statistical threshold of

p < 0.05 and a log fold-change (logFC) with an absolute value of at least 0.585. A total of 457 SDE genes were identified (

Table S1) comparing latent phase to age matched control samples. Pathway

p-values were calculated using the iPathwayGuide scoring system, which employs the Impact Analysis method. The predominant impacted pathways are related to immune signaling, i.e., chemokine signaling, antigen processing and presentation, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathways (

Table S2), and the immune response was the primary biological process altered in response to irradiation (

Table S3).

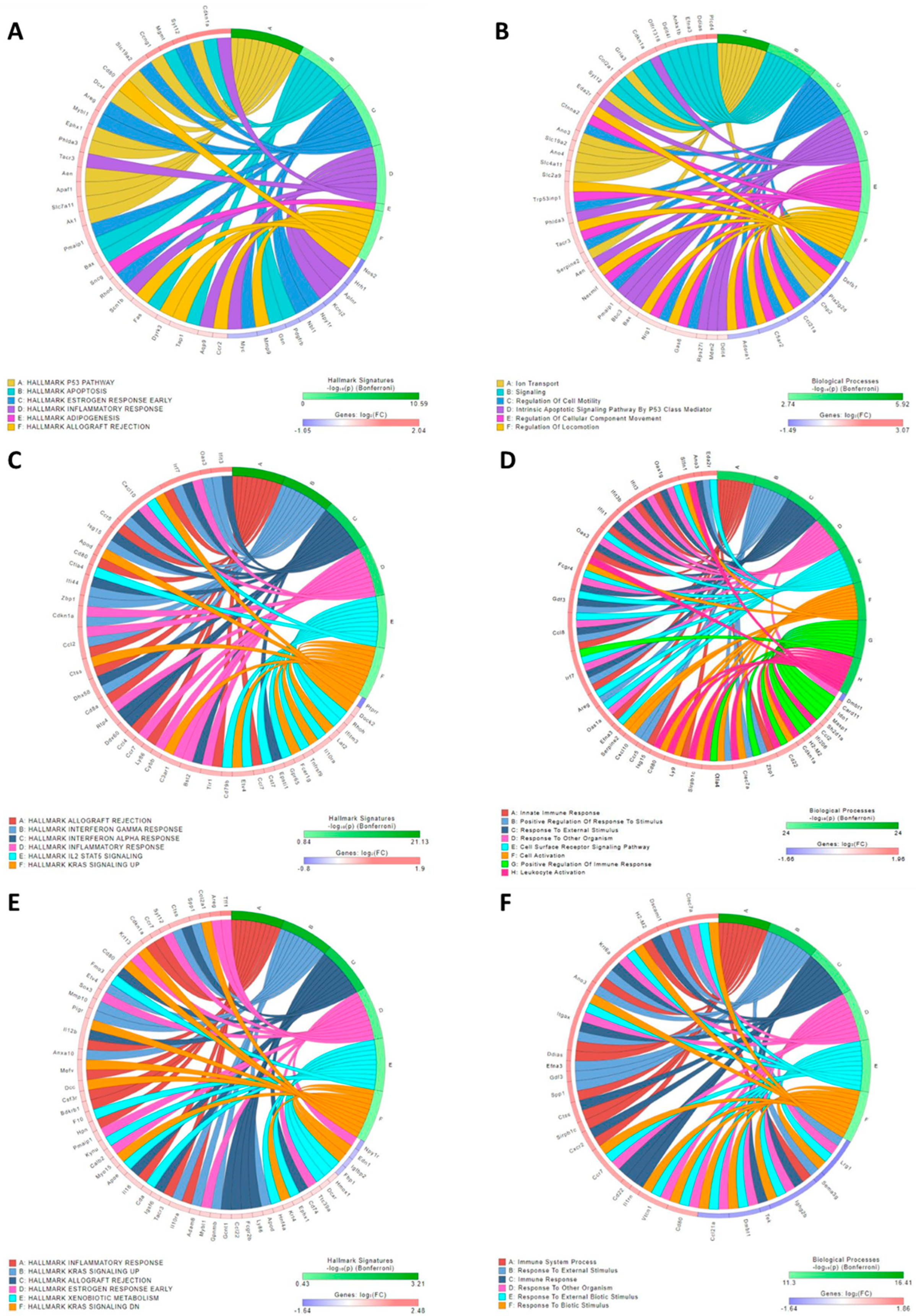

RNA sequencing identified upregulation of apoptotic pathway activity during the acute phase (

Figure 2A-B). During the latent (

Figure 2C-D) and chronic (

Figure 2E-F) phases, inflammatory pathways and processes were significantly increased. However, the immune response profile changed over time. Interestingly, a significant increase in

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (Cdkn1α), which encodes for the P21 protein, persisted across the acute, latent, and chronic phases (

Figure 2) with logFC values for acute, latent and chronic phases of 2.04, 1.41 and 1.38, respectively (p ≤ 0.000001 at all-time points).

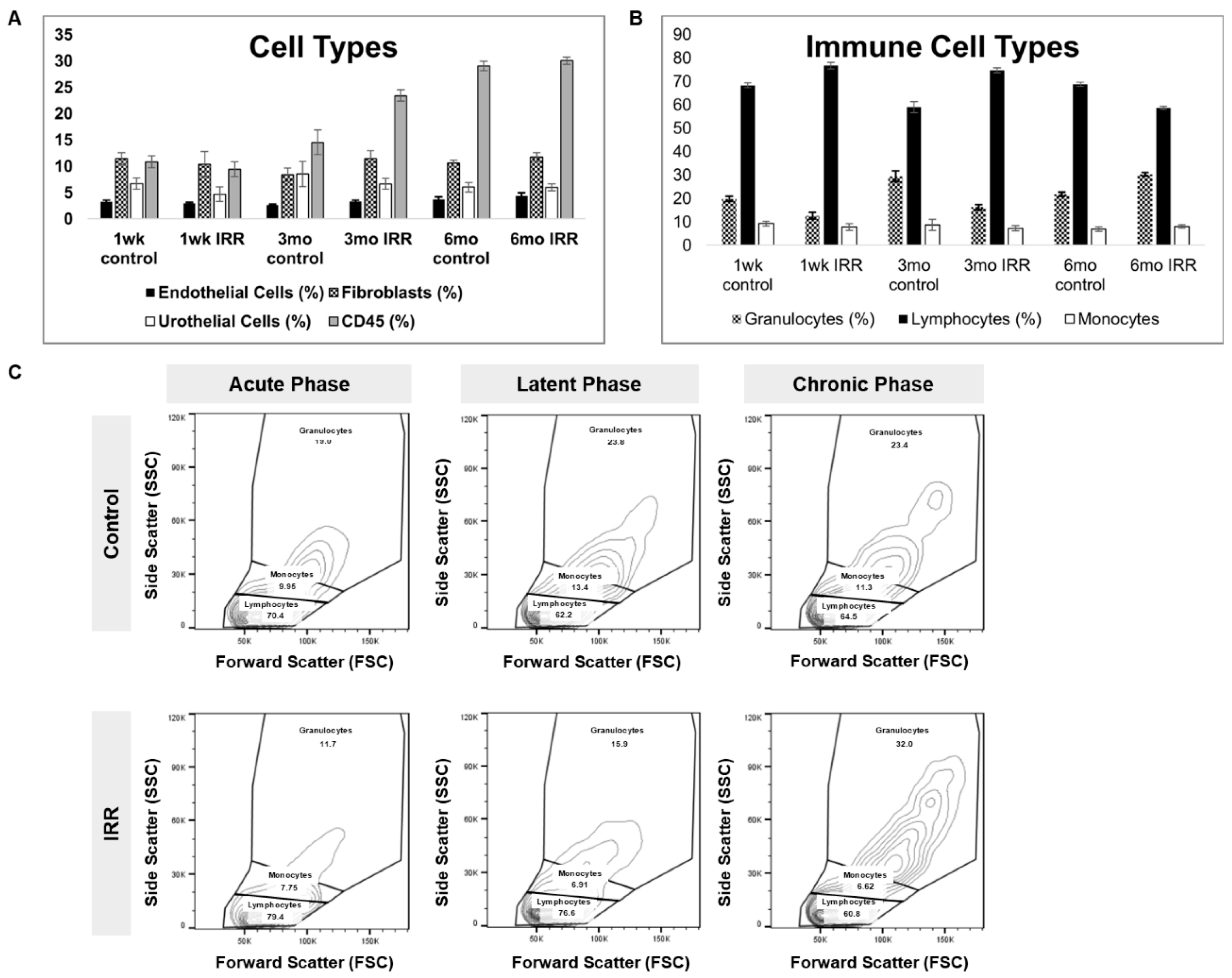

3.2. Cell Profiling in RC Disease Progression

To characterize immune dynamics during RC progression, we performed flow cytometric profiling of dissociated bladder tissue across acute, latent, and chronic time points. Significant interaction between phase and treatment were detected for granulocytes, lymphocytes, Mast cells and ILC2 cells (p-values 0.0205, 0.0283, 0.0037, 0.0493, respectively) (

Table S4). Comparison of CD45+ immune cells between control and irradiated bladders at acute, latent, and chronic phases (representative plots,

Figure S1) indicated an increase in the proportion of granulocytes with time. The proportion of granulocytes was inversely correlated to the proportion of lymphocytes after irradiation: during the acute and latent phases a higher proportion of lymphocytes was observed, while during the chronic phase granulocytes were more abundant than lymphocytes. No significant phase- or treatment-dependent differences were observed in endothelial, fibroblast, urothelial, or CD45+ cell abundance.

Each phase demonstrated unique shifts in immune composition over time (

Figure 3). Bladder-resident cell phenotypes (

Figure 3A,B

) highlights dynamic remodeling of the immune microenvironment following irradiation, supporting the notion that distinct immune states characterize each phase of RC. Distinct shifts in bladder-resident cell populations occurred, with significant phase-by-treatment interactions observed for granulocytes, lymphocytes, mast cells, and ILC2 cells (

Table S4). Comparisons of CD45

+ subsets demonstrated that lymphocytes predominated earlier in disease progression, whereas granulocytes became more abundant during the chronic phase.

3.3. Inflammatory Protein Profiling in RC Disease Progression

A total of 11 analytes were detected in bladder tissue lysate samples within assay limits (

Figure 4B): These included MCP-3, Eotaxin, IL-27, TNF-α, MIP-1α, MCP-2, MCP-5, GROα, IL-16, MMP-3, and IL-13. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant phase-by-treatment interaction for MCP-3, MCP-2, IL-27, and MMP-3 (

p-value 0.0142, 0.0364, 0.0391 and 0.0462 respectively,

Figure 4B, S5 Table). Notably, IL-27 levels were significantly higher in control bladders compared with irradiated bladders at the latent (3-month) phase consistent with impaired immune surveillance following irradiation. Chronic phase exhibited marked increases in MCP-3, MCP-2, and MMP-3 mediators associated with leukocyte recruitment and extracellular matrix remodeling, indicating a transition toward a pro-inflammatory, fibrotic microenvironment

PCA of the 11 inflammatory proteins detected in bladder tissue samples (

Figure 4C) revealed clear phase-dependent clustering between irradiated and control samples with higher precision in the chronic phase. At the latent phase PC1 and PC2 accounted for 62.36% of the variability in the data, with MMP-3, Eotaxin, IL-16, and IL-27 exerting the strongest influence on sample separation. Discriminatory power increased in the chronic phase, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 73.26% of variance. Chronic phase clustering was driven primarily by elevated MMP-3, MIP-1α, GRO-α, and IL-13 markers associated with chronic inflammation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and SASP activity.

4. Discussion

Radiation cystitis is a complex condition marked by acute and chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and vascular damage, progressing through three distinct phases. The initial phase involves bladder symptoms a few weeks after pelvic radiation therapy. This is followed by a symptom-free latent phase, which can last months to years. During which molecular changes may continue despite the absence of clinical signs. Ultimately, the final chronic phase is irreversible, marked by spectrum of clinical symptoms, from mild dysuria to impaired bladder compliance and hemorrhaging, for which no standard effective treatment exists. Understanding the biological mechanisms governing the transition between these phases is essential for developing strategies to prevent or mitigate chronic RC.

An established pre-clinical model of RC was employed to investigate RC disease progression.[24,32] This model resembles clinical manifestation of RC, with 1-week, 3-months and 6–months post-IRR representing the acute, latent phase and chronic phases. As previously published, irradiated mice are asymptomatic in the latent phase and develop a significant increase in extracellular matrix stiffness and compromised bladder function 6-months post-IRR treatment.[32] This model therefore provides a controlled framework for dissecting phase-specific molecular and immunological events that precede overt functional decline.

RC RNA sequencing data for acute and chronic phases were previously published [33], here we report RNA sequencing data for the latent phase.[33] Transcriptomic analysis across disease stages revealed a dynamic shift in biological pathways in apoptotic and inflammatory pathways as the disease progresses with acute injury dominated by apoptosis-related gene expression, reflecting direct cellular damage immediately following irradiation. By contrast, both latent and chronic phases showed strong enrichment of inflammatory pathways, with each phase displaying distinct cytokine and chemokine profiles. Extracellular matrix remodeling genes were highly expressed in the chronic phase, consistent with fibrosis development, indicating an attempt to repair the damage induced by irradiation. Notably, Cdkn1a (encoding P21), a key senescence mediator, was persistently elevated across all phases. Sustained P21 expression strongly suggests prolonged senescence induction beginning early after irradiation and continuing into advanced disease stages.

Radiation is known to induce senescence through P21 overexpression in a dose-dependent manner.[16,37] Radiation triggers DNA damage response (DDR) pathways, activating key sensor proteins such as ATM and ATR which in turn phosphorylate downstream effectors, including tumor suppressor p53. Activated p53 induces transcription of Cdkn1a (P21), enforcing cell-cycle arrest and stabilizing the senescent phenotype. This mechanism has been reported across multiple cell types, including smooth muscle, fibroblasts, osteocytes, myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells, show increased p21 expression after radiation exposure.[38−41] The sustained elevation of P21 observed in our study is therefore consistent with ongoing DDR activation and persistent senescence within the irradiated bladder

Accumulating evidence indicates that radiation-induced tissue damage progresses through a self-amplifying feedback loop involving DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and SASP proteins.[41−43] Under healthy conditions, senescent cells are efficiently eliminated by immune surveillance mechanisms. However, in disease states, senescent cells accumulate in the tissue due to inadequate immune surveillance, enhanced anti-apoptotic mechanisms, increased rates of senescence, or a combination of these factors.[43−45] Their SASP output can chronically inflame and remodel the tissue microenvironment, promoting fibrosis and functional deterioration. Our findings suggest that such mechanisms may underlie RC progression.

SASP proteins contribute to inflammation, regulate immune responses, alter the microenvironment, impair wound healing, and promote fibrosis.[44,46] Many cytokines and chemokines upregulated in our transcriptomic data are established SASP components.[23] By integrating cell and inflammatory protein profiling with bladder function and RNA sequencing, senescence-associated immune dysregulation contributions to RC progression was determined. As RC progresses, we observed a dynamic change in immune cell populations and inflammatory cytokines. Granulocytes, lymphocytes, CD117 and CD127 cells, as well as MCP-3, MCP-2, IL-27, and MMP-3 demonstrated significant differences between phases. A progressively inflamed and remodeling-prone tissue environment was highlighted by MCP-3 and MCP-2, indicating enhanced inflammatory chemotaxis of cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes. In addition, increases in MMP-3 indicate that these alterations in the immune microenvironment are commensurate with alterations in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling.

A particularly notable finding was the significant reduction of IL-27 in irradiated bladders during the latent phase, due to its role in response to damaged cells by antigen presenting cells which coordinate both innate and adaptive immunity by activating NK and cytotoxic T cells while limiting excessive granulocyte activity.[35,47] IL-27 acts as a negative regulator of granulocytes activity, interfering with both cytokine and ROS production.[48] These immune subsets play central roles in the clearance of senescent cells. Thus, reduced IL-27 at the latent phase may compromise immune surveillance, enabling senescent cells to accumulate. Consistent with this interpretation, immunophenotyping revealed a shift from lymphocyte predominance in earlier phases toward granulocyte enrichment in the chronic phase, a pattern compatible with impaired IL-27–mediated regulation and progressive inflammatory dysregulation. These findings highlight the latent phase as a critical window during which immune surveillance failure may drive long-term RC pathology.

As the disease progresses to the chronic phase, IL-27 levels rebound, surpassing those in control samples likely reflecting a compensatory or dysregulated immune response in the context of persistent inflammation. Chronic-phase clustering was driven by increased MMP-3, MIP-1α, GRO-α, and IL-13 mediators, which are associated with extracellular matrix turnover and chronic inflammatory signaling. These biochemical changes coincided with increased granulocytes and lymphocytes infiltration. Over time, MMP-3 levels were markedly elevated, which could reflect heightened tissue-remodeling activity. Together, these data support a model in which early senescence induction, followed by latent-phase immune surveillance failure, leads to SASP amplification and tissue remodeling.

Understanding the mechanisms underlying radiation-induced bladder senescence and tissue fibrosis is crucial for developing preventive and targeted therapies for radiation cystitis. Potential options include the use of senotherapies, a group of chemical compounds that target senescent cells in aging and disease, or immunomodulatory therapies.[49−51] These therapies may offer a means to mitigate radiation-induced bladder fibrosis and dysfunction.[9,10,22,52,53] Collaboration among radiation oncologists, biologists, and clinicians is essential for translating these findings into clinical applications that can optimize treatment outcomes and enhance the quality of life for patients undergoing pelvic radiation. Further research employing single-cell resolution and longitudinal profiling will be essential for defining senescent cell subtypes, immune-surveillance dynamics, and the temporal windows in which intervention is most effective. Translating these insights into clinical strategies will require close collaboration among radiation oncologists, urologists, biologists, and immunologists to improve treatment outcomes and survivorship for patients receiving pelvic radiation therapy.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that radiation induces a bladder environment resembling accelerated aging, characterized by persistent senescence, altered immune regulation, and progressive tissue remodeling. Central to this process is the latent phase, during which reduced IL-27 and shifts in immune composition suggest impaired senescence surveillance. Failure to eliminate senescent cells likely permits their accumulation, amplifying SASP-mediated inflammation and promoting extracellular matrix remodeling. By the chronic phase, this inflammatory–fibrotic loop manifests as structural and functional bladder decline. These results establish a framework in which senescence, immune dysregulation, and SASP activity act sequentially and synergistically to drive radiation cystitis progression

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprint.org. Figure S1: Cell profiling at 1 week, 3 months, and 6 months post-IRR to represent acute, latent and chronic phases of RC disease progression; Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes at 3 months post radiation treatment compared to age matched controls; Table S2: Pathways and their calculated p-values at 3 months post radiation treatment compared to age matched control samples; Table S3: Biological Processes and their calculated p-values at 3 months post radiation treatment compared to age matched control samples; Table S4: Two-way ANOVA analysis for bladder cells in irradiated samples versus time matched controls harvested at 1 week, 3 months and 6 months post-IRR treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SM, MC, BZ; Data curation: EW; Formal analysis: SM, AG, EW, YCL; Investigation: SM, AG, EW, SB, AM; Methodology: SM, BZ, MC; Project administration: SM, BZ; Supervision: BZ; Visualization: SM, AG; Writing—original manuscript: SM; Writing—reviewing and editing: RM, AG, BZ.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health, grant number R01DK135986.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Corewell Health Research Institute (AL-2020-04, approved on 01/19/2021;AL-23-02, approved on 12/28/2023).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IRR |

Irradiation |

| PRT |

Pelvic Radiation Therapy |

| RC |

Radiation Cystitis |

| RSEM |

RNA-seq by Expectation-Maximization |

| SARRP |

Small Animal Radiation Research Platform |

| SASP |

Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype |

References

- Siroky, M. B. The aging bladder. Rev Urol 2004, 6 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1), S3-7. From NLM.

- Kim, S. J.; Kim, J.; Na, Y. G.; Kim, K. H. Irreversible Bladder Remodeling Induced by Fibrosis. Int Neurourol J 2021, 25 (Suppl 1), S3-7 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Ko, I. G.; Hwang, L.; Jin, J. J.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, C. J.; Choi, Y. H.; Kim, H. Y.; Yoo, J. M.; Kim, S. J. Pirfenidone improves voiding function by suppressing bladder fibrosis in underactive bladder rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 977, 176721 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Brossard, C.; Lefranc, A. C.; Pouliet, A. L.; Simon, J. M.; Benderitter, M.; Milliat, F.; Chapel, A. Molecular Mechanisms and Key Processes in Interstitial, Hemorrhagic and Radiation Cystitis. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11 (7) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Helissey, C.; Cavallero, S.; Brossard, C.; Dusaud, M.; Chargari, C.; François, S. Chronic Inflammation and Radiation-Induced Cystitis: Molecular Background and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 10 (1) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Fijardo, M.; Kwan, J. Y. Y.; Bissey, P. A.; Citrin, D. E.; Yip, K. W.; Liu, F. F. The clinical manifestations and molecular pathogenesis of radiation fibrosis. EBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105089 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Straub, J. M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C. D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S. M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: mechanisms and implications for therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015, 141 (11), 1985-1994 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C. M.; Menias, C. O.; Katz, D. S. Radiation-induced effects to nontarget abdominal and pelvic viscera. Radiol Clin North Am 2014, 52 (5), 1041-1053 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J. Senolytic therapy ameliorates renal fibrosis postacute kidney injury by alleviating renal senescence. Faseb j 2021, 35 (1), e21229 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, C.; Song, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Tissue fibrosis induced by radiotherapy: current understanding of the molecular mechanisms, diagnosis and therapeutic advances. J Transl Med 2023, 21 (1), 708 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H. N.; Hardman, M. J. Cellular Senescence in Acute and Chronic Wound Repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2022, 14 (11) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L. Theories of biological aging. Exp Gerontol 1985, 20 (3-4), 145-159 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P. S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 1961, 25, 585-621 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L. J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J. L.; Lerman, L. O. Cellular senescence: the good, the bad and the unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18 (10), 611-627 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Mooi, W. J.; Peeper, D. S. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev 2010, 24 (22), 2463-2479 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Roger, L.; Tomas, F.; Gire, V. Mechanisms and Regulation of Cellular Senescence. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22 (23) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, J. P. Cellular senescence in normal physiology. Science 2024, 384 (6702), 1300-1301 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Burton, D. G.; Krizhanovsky, V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71 (22), 4373-4386 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P. D. Healing and hurting: molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol Cell 2009, 36 (1), 2-14 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L. E.; Yousefzadeh, M. J.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Robbins, P. D.; Zhu, Y. Cellular senescence: a key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J Clin Invest 2022, 132 (15) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186 (2), 243-278 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, S.; Tsou, P. S.; Varga, J. Senescence and tissue fibrosis: opportunities for therapeutic targeting. Trends Mol Med 2024 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Paciencia, S.; Saint-Germain, E.; Rowell, M. C.; Ruiz, A. F.; Kalegari, P.; Ferbeyre, G. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its regulation. Cytokine 2019, 117, 15-22 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zwaans, B. M.; Chancellor, M. B.; Lamb, L. E. Modeling and Treatment of Radiation Cystitis. Urology 2016, 88, 14-21 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zwaans, B. M. M.; Lamb, L. E.; Bartolone, S.; Nicolai, H. E.; Chancellor, M. B.; Klaudia, S. W. Cancer survivorship issues with radiation and hemorrhagic cystitis in gynecological malignancies. Int Urol Nephrol 2018, 50 (10), 1745-1751 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Huh, J. W.; Tanksley, J.; Chino, J.; Willett, C. G.; Dewhirst, M. W. Long-term Consequences of Pelvic Irradiation: Toxicities, Challenges, and Therapeutic Opportunities with Pharmacologic Mitigators. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26 (13), 3079-3090 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Dalsania, R. M.; Shah, K. P.; Stotsky-Himelfarb, E.; Hoffe, S.; Willingham, F. F. Management of Long-Term Toxicity From Pelvic Radiation Therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2021, 41, 1-11 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Neckonoff, E. L.; Marte, J.; Gorroochurn, P.; Joice, G. A.; Anderson, C. B. National Trends of Inpatient Radiation Cystitis: 2016-2019. Urol Pract 2024, 11 (4), 700-707 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Bagshaw, H. P.; Arnow, K. D.; Trickey, A. W.; Leppert, J. T.; Wren, S. M.; Morris, A. M. Assessment of Second Primary Cancer Risk Among Men Receiving Primary Radiotherapy vs. Surgery for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5 (7), e2223025 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Sanguedolce, F.; Sancho Pardo, G.; Mercadé Sanchez, A.; Balaña Lucena, J.; Pisano, F.; Cortez, J. C.; Territo, A.; Huguet Perez, J.; Gaya Sopeña, J.; Esquina Lopez, C.; et al. Radiation-induced haemorrhagic cystitis after prostate cancer radiotherapy: factors associated to hospitalization and treatment strategies. Prostate Int 2021, 9 (1), 48-53 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zwaans, B. M. M.; Wegner, K. A.; Bartolone, S. N.; Vezina, C. M.; Chancellor, M. B.; Lamb, L. E. Radiation cystitis modeling: A comparative study of bladder fibrosis radio-sensitivity in C57BL/6, C3H, and BALB/c mice. Physiol Rep 2020, 8 (4), e14377 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zwaans, B. M. M.; Grobbel, M.; Carabulea, A. L.; Lamb, L. E.; Roccabianca, S. Increased extracellular matrix stiffness accompanies compromised bladder function in a murine model of radiation cystitis. Acta Biomater 2022, 144, 221-229 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Mota, S.; Ward, E. P.; Bartolone, S. N.; Chancellor, M. B.; Zwaans, B. M. M. Identification of Molecular Mechanisms in Radiation Cystitis: Insights from RNA Sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25 (5) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J. P.; Desprez, P. Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol 2010, 5, 99-118 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Hunter, C. A. The immunobiology of interleukin-27. Annu Rev Immunol 2015, 33, 417-443 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Y.; Wang, C. J.; Shen, H. H.; Jiang, F.; Shi, J. L.; Wang, W. J.; Li, M. Q. Impaired IL-27 signaling aggravates macrophage senescence and sensitizes premature ovarian insufficiency induction by high-fat diet. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2024, 1870 (8), 167469 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M. A.; Rahman, M.; Ayad, A. A.; Warrington, A. E.; Burns, T. C. P21 Overexpression Promotes Cell Death and Induces Senescence in Human Glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15 (4) From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S.; Cho, H. J.; Cho, H. J.; Park, S. J.; Park, K. W.; Chae, I. H.; Oh, B. H.; Park, Y. B.; Lee, M. M. The essential role of p21 in radiation-induced cell cycle arrest of vascular smooth muscle cell. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004, 37 (4), 871-880 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Lagnado, A. B.; Farr, J. N.; Doolittle, M.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J. L.; LeBrasseur, N. K.; Robbins, P. D.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Ikeno, Y.; et al. Targeted clearance of p21- but not p16-positive senescent cells prevents radiation-induced osteoporosis and increased marrow adiposity. Aging Cell 2022, 21 (5), e13602 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K. K.; Stuart, J.; Chuang, Y. Y.; Little, J. B.; Yuan, Z. M. Low-dose radiation-induced senescent stromal fibroblasts render nearby breast cancer cells radioresistant. Radiat Res 2009, 172 (3), 306-313 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Rodier, F.; Coppé, J. P.; Patil, C. K.; Hoeijmakers, W. A.; Muñoz, D. P.; Raza, S. R.; Freund, A.; Campeau, E.; Davalos, A. R.; Campisi, J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11 (8), 973-979 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Passos, J. F.; Nelson, G.; Wang, C.; Richter, T.; Simillion, C.; Proctor, C. J.; Miwa, S.; Olijslagers, S.; Hallinan, J.; Wipat, A.; et al. Feedback between p21 and reactive oxygen production is necessary for cell senescence. Mol Syst Biol 2010, 6, 347 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. W.; Johmura, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Omori, S.; Migita, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; Yamazaki, S.; Shimizu, E.; Imoto, S.; et al. Blocking PD-L1-PD-1 improves senescence surveillance and ageing phenotypes. Nature 2022, 611 (7935), 358-364 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Ovadya, Y.; Landsberger, T.; Leins, H.; Vadai, E.; Gal, H.; Biran, A.; Yosef, R.; Sagiv, A.; Agrawal, A.; Shapira, A.; et al. Impaired immune surveillance accelerates accumulation of senescent cells and aging. Nat Commun 2018, 9 (1), 5435 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Palacio, L.; Goyer, M. L.; Maggiorani, D.; Espinosa, A.; Villeneuve, N.; Bourbonnais, S.; Moquin-Beaudry, G.; Le, O.; Demaria, M.; Davalos, A. R.; et al. Restored immune cell functions upon clearance of senescence in the irradiated splenic environment. Aging Cell 2019, 18 (4), e12971 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Papismadov, N.; Levi, N.; Roitman, L.; Agrawal, A.; Ovadya, Y.; Cherqui, U.; Yosef, R.; Akiva, H.; Gal, H.; Krizhanovsky, V. p21 regulates expression of ECM components and promotes pulmonary fibrosis via CDK4 and Rb. Embo j 2024, 43 (22), 5360-5380 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. D.; Wang, D. C.; Zhao, M.; Huang, A. F. An updated advancement of bifunctional IL-27 in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1366377 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. P.; Wu, H.; Xing, W.; Yang, S. G.; Lu, S. H.; Du, W. T.; Yu, J. X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Han, Z. C. Interleukin-27 as a negative regulator of human neutrophil function. Scand J Immunol 2010, 72 (4), 284-292 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Davies, H. R.; Richeldi, L.; Walters, E. H. Immunomodulatory agents for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003, (3), CD003134 From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Paget, J. T.; Ward, J. A.; McKean, A. R.; Mansfield, D. C.; McLaughlin, M.; Kyula-Currie, J. N.; Smith, H. G.; Roulstone, V.; Li, C.; Zhou, Y.; et al. CXCL12-Targeted Immunomodulatory Gene Therapy Reduces Radiation-Induced Fibrosis in Healthy Tissues. Mol Cancer Ther 2025, 24 (3), 431-443 From NLM Medline. [CrossRef]

- Seon, G. M.; Kim, I. G.; Um, S. W.; Chung, E. J.; Yang, H. C. Mitigation of radiation-induced esophageal fibrosis by macrophage-targeted phosphatidylserine-containing liposomes with partial PEGylation. Bioact Mater 2025, 52, 574-587 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, A.; Kellogg, D., 3rd; Justice, J.; Goros, M.; Gelfond, J.; Pascual, R.; Hashmi, S.; Masternak, M.; Prata, L.; LeBrasseur, N.; et al. Senolytics dasatinib and quercetin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results of a phase I, single-blind, single-center, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial on feasibility and tolerability. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104481 From NLM. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J. L.; Tchkonia, T. Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. J Intern Med 2020, 288 (5), 518-536 From NLM. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).