1. Introduction

Modern geopolitical and economic conditions, including increasing globalisation, the mobility of people and goods, as well as the emergence of new security threats, require a capable and coordinated response from states in managing their external borders. States are faced with increasingly diverse and complex threats – illegal migration, terrorist and organised crime activities, trafficking in people and drugs, illicit arms circulation, environmental and public health threats, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, as well as supply chain disruptions due to climate change or pandemics [

1]. These threats are often interconnected and exploit vulnerabilities in the same system, making traditional, separate approaches to border management insufficient.

External border security has emerged as a core arena where multiple security domains intersect, making it central to contemporary security studies. The literature study demonstrates that border management has evolved from simple territorial control to sophisticated risk governance systems that address migration, terrorism, public health, technology deployment, and geopolitical tensions [

2]. Customs and other border control services around the world manage external border security risks through coherent strategies, technological integration and cooperation systems. These efforts aim to strike a balance between facilitating legitimate trade and travel and preventing illegal activities, while ensuring national security. The implementation of these strategies involves a range of stakeholders, including international organisations, national governments and private sector partners. Contemporary border management increasingly operates through risk analysis and management frameworks rather than solely through traditional border policing approaches. This shift reframes how individuals and situations are categorised as "risks" and fundamentally alters resource allocation and operational priorities [

1]. Coordinating a common risk management strategy for external border security is challenging due to the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Effective information exchange is necessary, striking a balance between security and trade facilitation. Coordinated border management requires streamlining and integrating processes and technologies to enable different agencies to work together effectively on border issues, thereby reducing costs, enhancing border security, and facilitating trade [

3,

4,

5].

International organisations have developed several border management models based on cooperation, information exchange, and process integration. These include the Collaborated Border Management model developed by the World Bank [

4,

6], the Integrated Border Management (IBM) model developed and implemented by the European Union (EU), which is set out in European Commission Regulation (EC) 2016/1624, and the Coordinated Border Management model developed by the World Customs Organisation (WCO). A common element of these models is cooperation between border management agencies to enhance information exchange, minimise duplication of functions, and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of resource utilisation. Although international organisations have developed several border management models based on cooperation and information exchange and have established clear principles for the coordination of border management institutions, joint risk management, and the harmonisation of procedures and IT systems, it has not yet been possible to ensure that the services involved in ensuring border security use a unified and comprehensive approach to sustainable border security risk management. The literature consistently identifies governance fragmentation as a fundamental challenge in external border security management. Multiple agencies operating at different governmental levels (local, national, and supranational) often lack effective coordination mechanisms, resulting in gaps in resilience and response strategies. This fragmentation undermines the coherent implementation of border security policies, creating vulnerabilities that can be exploited [

2,

7]. This is also clearly demonstrated by the fact that this study found that, out of the 27 EU Member States, only a few Member States have a comprehensive and integrated approach to risk management at external borders. Most countries still use sectoral systems with varying degrees of cooperation.

A comprehensive approach to border security risk management requires an integration of multiple assessment methodologies. Qualitative risk assessment provides a basis for understanding subjective threat aspects, while quantitative analysis offers precise measurements for decision-making. This dual approach enables border control authorities to evaluate both measurable data points and contextual factors that may impact security outcomes. Effective management of external border security risks (hereinafter referred to as border security risk management) is crucial to prevent potential information gaps that arise when each authority operates in isolation. Only a joint risk analysis enables a comprehensive understanding of the nature and intensity of threats in various border segments and time periods. It facilitates timely decision-making, efficient reallocation of resources, and adaptive action in the event of new threats. In border management, it is essential to develop innovative and sustainable methodological approaches to managing border security risks. This would allow for the systematisation of processes and the identification of vulnerabilities in security systems. In the paper, the authors conclude that methodological solutions help organisations make informed decisions based on risk assessments, thereby improving resource allocation and the effectiveness of security measures. Ultimately, these methodologies provide a structured system that improves the ability to manage risks in a changing security environment.

This study identifies the main benefits of sustainable common border security risk management and methodological solutions that could support sustainable external border security. The study recommends ways to enhance tactical (one-year) border security risk management for faster response to evolving threats. Today's security environment is highly dynamic, with threats evolving in both nature and intensity, necessitating regular risk assessments and strategy updates. A one-year period is optimal for collecting and analysing statistical data on previous incidents, identifying trends, and setting priorities for the next period. This approach enables decisions to be based on current, empirical data rather than relying solely on long-term forecasts. The tactical-level model provides flexibility and the ability to adapt to new risks, such as geopolitical changes, fluctuations in migration flows, the emergence of new technologies or types of crime. A unified methodology, applied on an annual basis, promotes inter-institutional cooperation and a more efficient use of resources. This is particularly important because sustainable border security risk management involves several institutions with different functions and priorities. A tactical (annual) approach ensures timely decision-making and rapid reallocation of resources, which is essential for responding effectively to new threats and eliminating blind spots in the flow of information between institutions. In this article, the authors analyse approaches that would help national and international institutions to develop a unified, effective, and sustainable system for assessing and managing border security risks. This study aims to provide practical and analytically sound solutions that support sustainable border management, promote national and regional security, and foster international cooperation.

Structure of the article: (1) research topicality is described and a research gap to be filled is highlighted, (2) a combined (mix) qualitative and quantitative research methodology is employed to and explain key theory foundations, models, and analytical approaches that ground the study, (3) comprehensive literature review covering border security risk management approaches and techniques is provided, (4) main study results and discussion contain a risk management system, risk analysis model and approach, risk management process and experience are presented, (5) solutions for sustainable joint border security risk assessment at the tactical level are proposed. Conclusions briefly summarise the main study outcomes and insights.

2. Materials and Methods

The authors use a systematic, data-driven, interdisciplinary approach to develop unified risk management solutions for border control. Using a methodology that combines qualitative and quantitative research methods, it is possible to evaluate existing systems, identify needs, problems and current issues, compile examples of good practice, and outline measures to be implemented in the process of creating a unified system.

To gain a general overview of existing risk management systems in border management, a literature review and analysis of relevant policy documents and regulatory acts are conducted. This enables an assessment of risk management in various institutions involved in border management at both the national and European Union levels, as well as an examination of practices in different EU Member States. Particular attention is paid to practices in Latvia, as border management in Latvia focuses on ensuring the security of the EU's eastern border, based on common border management standards.

The study is based on well-established risk management theory foundations and models, which have shifted public safety strategies toward improving system security barriers and organisational processes, rather than just blaming front-line operators [

8]. Modern security risk management acknowledges complexity while striving for high reliability through training, redundancy, and adaptability. Thus, institutions and the public are preoccupied with future safety, and political conflicts often centre on the distribution and acceptance of risks [

9]. Cultural and sociological theories [

10] emphasise that public security risk management must consider social acceptance, risk communication, and the political context, in addition to technical risk calculations. Scholars emphasise that an effective public security risk management is multidisciplinary. Therefore, it requires scientific analysis of hazards, organisational learning, and engagement with public values and perceptions to ensure that risk reduction measures are both technically sound and socially robust. Academic studies emphasise that risk management in border security serves a dual objective – enhancing security while facilitating legitimate trade and travel. Contemporary research also highlights the growing role of technology (e.g., big data analytics, artificial intelligence) in border risk management [

11]. While the fundamental theories remain rooted in risk analysis, new methods enable handling the scale and complexity of global flows. Overall, the theoretical underpinnings of border security risk management are closely aligned with general risk management but tailored to the cross-border context. In this study, the authors examine the Common Integrated Risk Analysis Model (CIRAM), used by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency [

12]. It is concerned with a conceptual framework for assessing threats at external borders, providing structured methods for evaluating risk indicators and producing risk analyses that inform operational decisions. A gap analysis was performed during the study. By comparing the current situation with the desired model, the authors have identified gaps, opportunities to standardise systems, and proposed improvements that could deliver future benefits through better methodology.

3. Literature Review

The scientific articles and publications reviewed emphasise the importance of external border security risk management and the multifaceted approaches to addressing this risk. The articles and publications address aspects that influence the effectiveness, meaningfulness, and challenges of border security risk management.

Polner [

13] emphasises the importance of coordinated border management, arguing that it is a strategic approach that enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation by improving coordination between border authorities at both local and international levels. This includes joint policy development and operational action to streamline processes and reduce duplication. Fink and Rijpma [

8] analyse how the EU manages its external borders through shared competences, agencies, and regulatory frameworks within coordinated border management. Lawson & Bersin [

9] point to the challenges of border management cooperation. Cooperative border management challenges the traditional unilateral approach by supporting cooperation between neighbouring countries to facilitate legitimate trade and travel. The primary objective of this approach is to prevent and combat transnational crime, as well as manage transboundary ecological resources. A sustainable common European border security policy has been discussed by Georgiev [

16], who highlights early efforts to harmonise national approaches and balance security with freedom of movement.

Border control services around the world manage external border security risks through the integration of intelligence, coordinated border management, and joint efforts. These strategies are designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of border security while facilitating legitimate trade and travel. Ylönen & Aven [

17] point to the perspective of integrating intelligence and risk management. A key element of this approach is inter-agency interoperability and joint risk management. Intelligence involves the collection, exchange, processing, analysis and dissemination of information on threats related to cross-border movements, illicit activities, and organised crime. A common framework for integrating intelligence and risk management provides customs and border control services with new insights and tools to deal effectively with risk and intelligence issues.

To improve the security and efficiency of border control systems, sustainable common border security risk management involves the strategic application of risk management principles. Such an approach is essential to address the complex challenges posed by cross-border threats, demographic pressures and technological developments. The integration of risk-based methodologies into border security aims to optimise resources, improve threat detection, and streamline border processes. Jain et al. [

18] in their study propose the implementation of a risk-based border management system to classify travellers into risk groups, allowing for more efficient use of resources and improved passenger flow. Peterson [

19] notes the primary strategies for addressing security risks. Security risk management includes proactive risk identification, assessment, vulnerability analysis, implementation of risk mitigation strategies and risk acceptance. Also important is the implementation of the 4Ds: deter, deny, detect, and delay. Johnson [

20] complements this perspective by examining how less visible border vulnerabilities can undermine national resilience, highlighting the importance of anticipatory and systemic risk management approaches. Tudor & Gavrila [

21] emphasise that risk analysis plays a crucial role in enhancing customs risk management, identifying regulatory gaps, and adapting to the complexity of sanctioning in the current geopolitical environment. The authors highlight significant gaps in sanctions regulation, such as overlapping laws, inconsistent application, insufficient systematisation, and inadequate risk management strategies. These shortcomings highlight an urgent need for reforms to enhance the effectiveness of sanctions enforcement. In this context, Hoffman et al. [

22] propose a structured methodology for designing customs risk models, emphasising systematic risk identification, data quality, and continuous model refinement.

Several scholars have highlighted the integration of technology in risk management in their research. Rousan & Intrigila [

23] highlight the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics in border security, which enhances the ability to manage complex data and improves threat detection capabilities. AI-based risk management systems can streamline border control processes, reduce human error and improve overall security measures. Oussama et al. [

24] propose using AI to develop recommendation systems for customs risk management, utilising supervised machine learning algorithms in shipment processing, and to assist customs inspectors in decision-making. García and Caballero [

25] further advance this approach by introducing a multi-objective Bayesian decision model combined with dynamic optimisation, demonstrating how machine learning can enhance customs fraud detection through adaptive risk scoring. Rats & Alfimova [

26] and Yadav et al. [

27] highlight the impact of AI in customs process automation, allowing real-time monitoring and analysis of potential risks. Kuo & Chou [

28] also highlight the ability of AI to analyse large data sets from import manifests and other sources to identify anomalies indicative of smuggling or fraud with sufficient accuracy. Tudor & Gavrila [

21] note that AI plays a crucial role in improving sanction detection and enforcement by enhancing monitoring capabilities, facilitating real-time data analysis and automating risk assessment, thereby supporting control authorities in their efforts to combat sanctions evasion. Razumei et al. [

29] highlight that while AI offers significant benefits in customs risk management, it is important to consider the challenges associated with its implementation. These include the need for interpretability of AI models, as customs officers need clear insight into AI-based decisions. Additionally, ethical considerations and data privacy concerns must be addressed to ensure the responsible use of AI in customs operations. As well, according to Rats & Alfimova [

26], AI integration should be aligned with international standards and practices to ensure consistency and efficiency across regions.

Livdāne & Arbidāne [

30] note CIRAM as a systematic approach to risk analysis, ensuring that the process is organised and free from randomness. CIRAM emphasises the importance of processing information at all levels – strategic, operational and tactical. This holistic approach enables a deeper understanding of threats, vulnerabilities, and impacts, which is essential for a qualitative risk analysis. CIRAM improves the quality of risk analysis through structured methodologies, comprehensive information processing, feedback mechanisms, quality control measures, training initiatives and efficient resource allocation. These elements work together to ensure that risk analysis is not only systematic but also responsive to the dynamic nature of border management challenges.

To improve the effectiveness of sustainable border management strategies in the EU, Mahmutovic & Alhamoudi [

31] propose the use of retrospective and prospective analysis, statistical indicators, categorisation of risk levels, holistic understanding of conditions and integration of tactical management to manage border risks.

Widdowson [

32] proposes an integrated compliance management system that encompasses several key components, collectively enhancing customs risk and compliance management. The author notes several standards and rules to be used in customs risk management. These are noted as the Kyoto Revised Convention, which requires the implementation of risk management in customs controls, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade Facilitation, which emphasises risk management to avoid discrimination, and the ISO 31000 international risk management standard, which is applicable across all sectors and which the World Customs Organization (WCO) has included in its Risk Management Handbook. The practical application of ISO 31000 is further elaborated in guidance materials such as the white paper by Lachapelle et al. [

33], which outlines key principles and implementation considerations for risk management frameworks.

Sustainable border security risk management combines resources from various agencies, countries, and technologies to address external threats more effectively. Several important aspects are highlighted in the literature. Schneller et al. [

34] further support this integrated approach by analysing converged security risk management, identifying organisational drivers and barriers to effective coordination across security domains. Coordinated border management enhances efficiency, reduces duplication, and fosters cooperation among border authorities [

4,

13]. The integration of intelligence and risk management enables the more effective identification of threats and their timely response [

17]. The use of technology, particularly AI, enhances data analysis, improves threat detection, and automates processes [

23,

24]. The CIRAM model provides a systematic and multi-level approach to risk analysis [

30]. International standards (e.g., ISO 31000, PTO agreement) ensure a consistent approach and quality [

32].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Key Steps of a Risk Management System

Ensuring a high level of security while maintaining the rapid flow of people and goods across customs borders has always been a key challenge for border management and remains so today. Border threats have increased significantly over the last decade. This has particularly affected the EU's external borders. For example, since 2015, when illegal migration reached more than 1.3 million asylum seekers [

35], illegal migration has remained a significant threat to the EU's security. Russia's aggression against Ukraine, which began in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and continued with the launch of active war in 2021, provoked a sharp reaction from Western countries. This resulted in sanctions, the administration of which falls within the competence of customs and requires considerable resources. These are just some of the many border security threats faced daily by border management services. Many of the world's most secure countries are economically developed countries with high incomes [

36,

37]. One of the main drivers of the economy is international trade. This means that the biggest challenge for border control services is to ensure secure borders while not hindering legal international trade and the flow of travellers. As resources are limited and the level of border security threats is increasing, border management services implement well-thought-out risk management systems to achieve their objectives [

11,

38]. Organisations use risk management to streamline their operations [

11]. A common and practical risk management model is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). ERM is a structured, organisation-wide system for identifying, assessing, and managing risks [

39]. Unlike traditional risk management, which often considers risks separately (finance, security, IT), ERM takes a holistic approach, integrating all risks across the organisation into a single system, ensuring that risk-taking is aligned with the organisation's objectives. A simplified ERM model is presented in

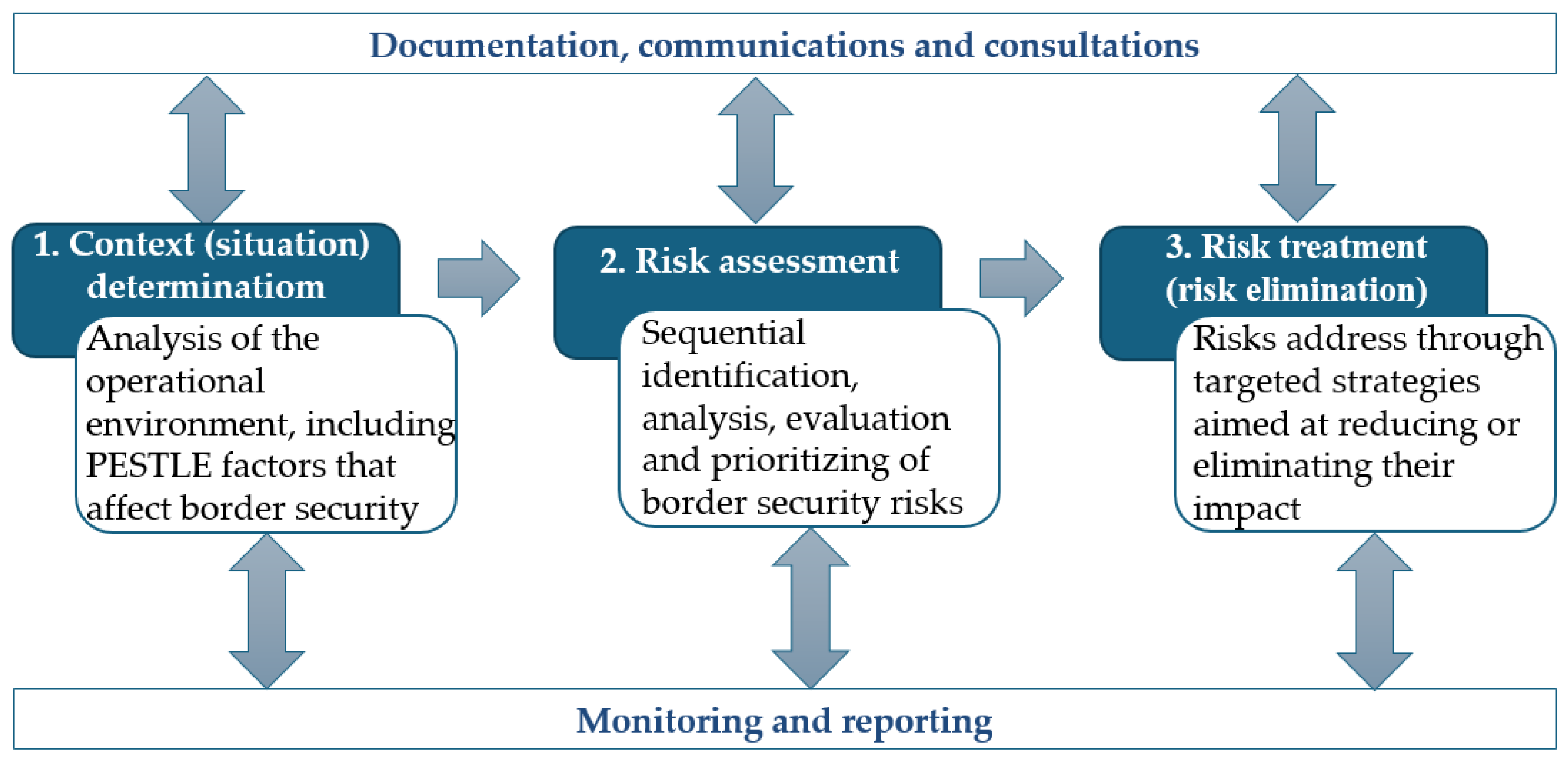

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that risk management is a continuous process that allows for the detection of changes in the external and internal environment that create new threats or alter the existing level of risk. Regular updates to risk assessments ensure that the management response is timely and effective. The transparency and effectiveness of the risk management process is ensured by clear documentation and open communication organised by management throughout the organisation. The sustainable risk management process, which is implemented at all levels of the organisation, includes detailed risk assessment and processing records, information exchange, as well as communication with stakeholders, experts, and the public to ensure sound decision-making. Monitoring, which also includes management reviews, is organised by senior management. The organisation's management may designate responsible units for maintaining risk management.

4.2. Elements of the Risk Management System for External Border Security

The literature review has already shown that effective external border security risk management requires a structured and integrated approach that combines various institutional, strategic, and technological components. This system is essential for identifying, assessing, and responding to a range of potential threats at the national border, thereby ensuring both security and compliance with international standards.

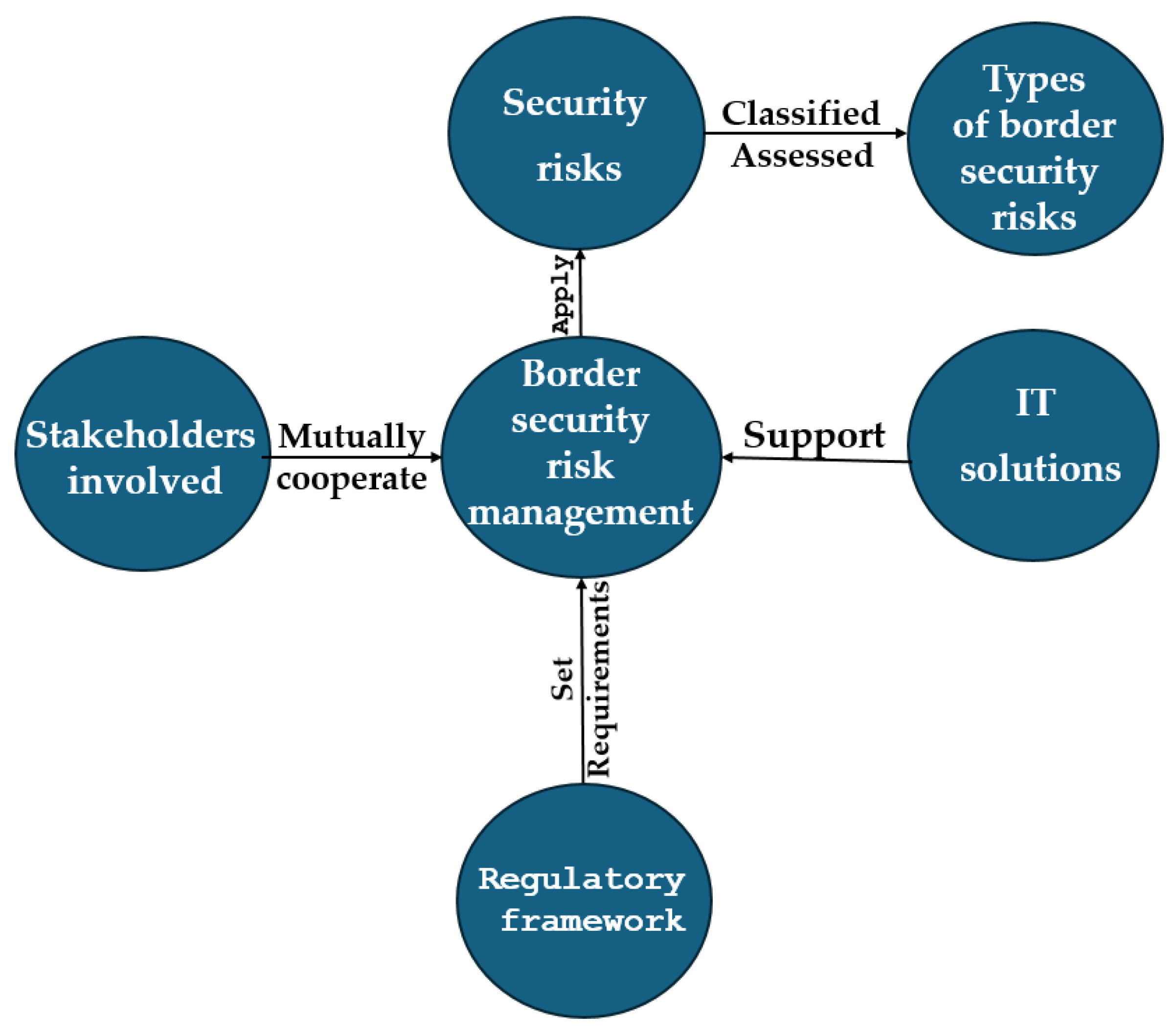

Figure 2 illustrates the primary elements that underpin the external border security risk management system. Effective border security risk management is based on multi-layered institutional cooperation involving several public authorities responsible for implementing border control measures. A distinction can be made between direct and indirect border management. Direct border management encompasses border control and surveillance, customs control, as well as food, veterinary, and phytosanitary control. The border guard implements direct border management by controlling the movement of people and monitoring the green border [

40]. At the same time, customs controls are implemented to monitor the flow of goods and ensure compliance with trade policies [

41]. In addition, veterinary, phytosanitary, sanitary, and food safety controls are implemented to ensure that animals, plants, and food products comply with regulatory requirements and to protect public health, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

42]. For example, in Latvia, direct border management functions are carried out by the State Border Guard, the Customs Administration of the State Revenue Service, and the Food and Veterinary Service (FVS). Border management functions are performed both outside direct border surveillance – in third countries, where diplomatic missions implement visa policies- and within the country, where migration and asylum policies are implemented. The Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Climate, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Culture, and other state administration institutions are involved in implementing indirect border management in Latvia.

Direct border management at the external border involves managing security risks, which encompass a wide range of threats, including illegal migration, the smuggling of goods and substances, human trafficking, terrorism, and the spread of diseases or hazardous materials. To ensure effective and sustainable risk management, each service develops a systematic process for identifying and assessing risks, and for developing and implementing strategies to reduce security risks to an acceptable level or to mitigate their impact. This includes strategic and tactical planning, as well as operational coordination and the use of data (including intelligence) in decision-making. Interagency cooperation is a highly effective tool in managing border security risks. Their coordinated action is crucial to reducing risk. This includes information exchange, joint training, and cooperation operations. Cooperation extends beyond national borders to involve international partners. It is prevalent within the EU.

An important aspect of sustainable border security risk management is the adoption of a common methodology and coordinated border control strategies, which ensure that all agencies involved operate within a unified framework. Coordination helps to avoid duplication of efforts, ensures the effective use of resources, and strengthens the overall security situation. It includes joint planning, common protocols, and integrated operations.

After reviewing the literature, the authors of the article believe that integrated information and communication technologies (ICT) are also an essential element of a common border security risk management system. ICT systems support real-time data exchange, monitoring, risk analysis, and decision-making. Integrated technologies improve situational awareness, streamline border procedures, and enable rapid response to new threats. Examples include biometric systems, surveillance drones, and interoperable databases.

The elements of the sustainable external border security risk management system (

Figure 2) together form a comprehensive and dynamic system for managing external border security risks. Their integration ensures that border control is not only reactive but also proactive, capable of adapting to changing threats and operational challenges. In

Table 1, the authors have summarised the main border security risks.

As several border management services address 43% of border security risks, close cooperation between the relevant border control services and a unified risk management methodology are necessary to assess the level of risk and develop unified measures to mitigate these risks. To focus the study, the authors examined current risk management methods used by agencies responsible for direct border management.

4.3. Common Integrated Risk Analysis Model (CIRAM)

In the field of border protection, FRONTEX, in cooperation with the border guard services of EU Member States, has developed the Common Integrated Risk Analysis Model (CIRAM) to establish a common risk analysis methodology across the EU and Schengen-associated countries [

30]. It is a standardised and unified system at the EU level to support a practical approach to risk analysis at the EU's external borders. However, it does not cover customs, veterinary, phytosanitary, sanitary, and food safety areas. CIRAM has been developed to enhance strategic, operational, and tactical decision-making processes by providing a structured methodology for identifying, assessing, and responding to risks that may impact both border security and internal security within the EU [

12]. It supports coordinated decision-making at all levels of governance, ensures the effective allocation of resources, and promotes the harmonised exchange of information. The model integrates threat, vulnerability, and impact assessments into a single, harmonised system. The CIRAM model is based on three main components: threat, vulnerability and impact assessments. According to CIRAM, the overall risk level

(Rb) is determined in accordance with equation (1):

The threat (T) assessment evaluates the extent and likelihood of pressures such as illegal migration or cross-border crime. It includes an analysis of intelligence reports, historical data, and current trends to identify potential threats. This assessment helps to understand the nature and extent of the risks faced at the external borders. The vulnerability (V) assessment analyses the ability of border management systems to mitigate the identified threats. This includes an assessment of the effectiveness of infrastructure, staffing levels, legal frameworks, and operational procedures. By understanding existing vulnerabilities, decision-makers can identify areas that require strengthening to enhance overall border security. The impact (I) assessment measures the potential consequences of the identified threats to internal security, border management operations, and humanitarian aid outcomes. This includes an analysis of the potential impact on public safety, economic stability, and social cohesion. The risk level assessment helps to prioritise risks based on their potential severity and informs the development of mitigation strategies. It should be noted that equation (1) for risk level assessment is applied in all strategic, operational, and tactical decision-making processes of border guard services.

CIRAM follows an intelligence cycle that includes mission definition, collection, evaluation, comparison, analysis and interpretation, reporting, dissemination, and review. Both qualitative and quantitative methods are used in the analysis and assessment of information, including scenario analysis, risk matrices, and indicator-based monitoring.

Scenario analysis is the primary tool used by CIRAM to explore possible future developments under conditions of uncertainty. It helps decision-makers prepare for different outcomes by producing messages (reports) based on historical trends, expert judgments, intelligence reports, and socio-political developments. Scenarios typically include a baseline scenario (current trends), a worst-case scenario (high impact, low preparedness), a best-case scenario (effective mitigation), a disruptive scenario (unexpected events), and a hybrid scenario (multiple variable threats).

CIRAM structures risk assessment into four levels: third countries (preventive measures at source), neighbouring third countries (cooperation and information exchange), border control (surveillance and checks at external borders), and the Schengen area (internal control and return operations). CIRAM develops risk analysis reports tailored to strategic (long-term planning), operational (resource allocation) and tactical (real-time decisions) needs. Recommendations are categorised as preventive, corrective, directive, and detective. All results must be based on the SMART approach, i.e., specific, measurable, acceptable, realistic, and time-bound. CIRAM integrates real-time monitoring tools, such as EUROSUR and FRAN, and extends monitoring to third countries to anticipate emerging threats. It combines indicator-based and intelligence-based systems to provide a comprehensive picture of the risk landscape [

12]. At the same time, it is worth noting that the CIRAM model is continually being improved and is currently in the CIRAM 3.0 development stage, which includes both changes in risk level assessment and more precise indicators for measuring the level of individual risk assessment components.

4.4. Customs Risk Management Process

Effective risk management by customs authorities ensures robust security standards while promoting trade efficiency. By prioritising high-risk shipments for scrutiny and expediting the clearance of low-risk consignments, customs strike an optimal balance between regulatory control and trade facilitation. Customs risk management, like border guarding, can be divided into three levels: operational, tactical, and strategic [

43]. It should be noted that Frontex designates the tactical level of management as the lowest and the operational level as the middle [

44]. In contrast, in business and customs management, the lowest level of management is operational, and the middle level is tactical [

43,

45]. This approach also applies to border security risk management, and this study will apply the approach used in business and customs services. It is worth noting that border management services approach operational and tactical levels of management differently.

The implementation of customs risk management worldwide is governed by frameworks such as the Revised Kyoto Convention and the SAFE Standards, thereby achieving a common approach to customs risk management. These principles ensure that customs services can effectively manage risks while supporting legitimate trade and economic growth [

46]. The customs risk management process is sustainable, cyclical and systematic, providing a structured approach to identifying, assessing, and controlling risks. Customs risk analysis is based on a risk assessment approach that combines the probability of a risk event occurring with its impact [

47].

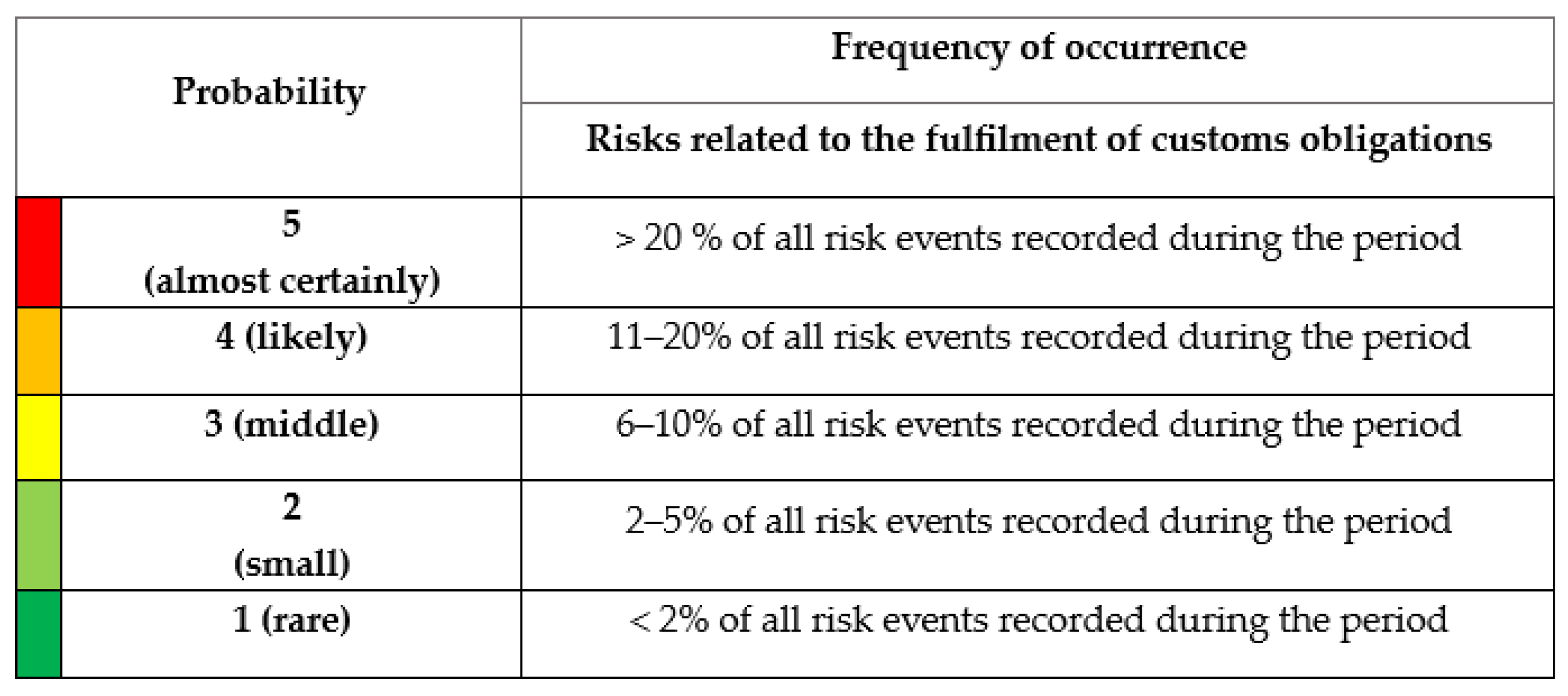

The matrix method [

48] is used to assess the level of risk, as well as the probability of a risk event occurring and its impact. In accordance with ISO 31010, the following equation (2) is used to determine the level of customs risk:

where R – customs risk level, P – probability of customs risk occurrence, and I – customs risk impact level.

At the operational level, several methods are employed to assess customs risks, which collectively enable the determination of the probability and impact level of these risks. Customs uses electronic data, predictive analytics, and machine learning for accurate, data-driven risk assessment.

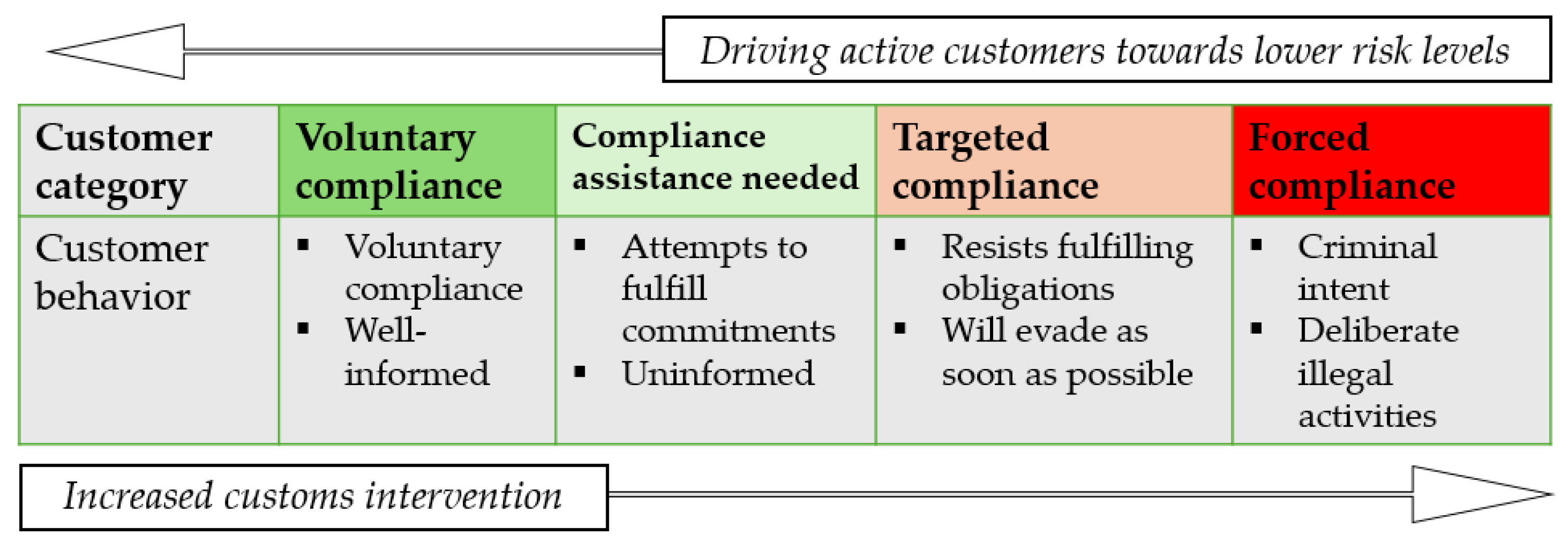

At the same time, compliance management distinguishes between compliant and non-compliant participants in international trade by grouping them according to risk levels. Risk-based compliance management allows customers (supply chain operators) to be segmented into categories based on their behaviour (see

Figure 3).

The customs surveillance system uses an approach based on different levels of compliance. These levels differ in terms of the degree of risk and the intensity of intervention required. Risk categorisation allows participants to be classified from those who comply voluntarily to those who deliberately violate the rules. Appropriate guidelines and responses are applied to each level. Voluntary compliance refers to the situation where companies or individuals voluntarily adhere to the rules without external enforcement. In this case, the risk is low, and operators are rewarded with simplified procedures that facilitate cooperation with the Customs Service. Assisted compliance refers to situations where companies or individuals require additional guidance and support to comply with regulations. Targeted compliance requires active monitoring and targeted intervention, as there is a higher risk that the rules will not be followed without effective control. Enforced compliance refers to high-risk situations where strict control and supervision are necessary to ensure adherence. Customs services aim to guide the behaviour of companies and individuals so that as many participants as possible comply with the rules voluntarily. This enables customs authorities to concentrate their resources on more significant threats and risks. To achieve this goal, a comprehensive approach is employed, which encompasses several key elements. For example, legislation is used to clearly define responsibilities so that all parties involved are aware of their obligations. To promote understanding of the requirements set out in the regulations and to encourage voluntary compliance, customers are informed and educated, including on decisions taken by customs, using various information and communication technology tools, which in turn improves the effectiveness of the risk management system.

Given that most countries around the world have accepted the implementation of the SAFE standard [

46], a widely used approach is to request advance information about shipments of goods. This allows customs authorities to assess the level of customs risk probability (P) for a particular shipment promptly, taking into account characteristic risk indicators, which include a wide range of indicators – from the assessment of the reliability of companies involved in the movement of goods (consignor, consignee, carrier, broker, etc., see

Figure 3), to the summary of operational information on the shipment, as well as the assessment of the goods, transport conditions and other factors included in the customs declaration.

The level of impact of customs risk (I) is determined by assessing various possible consequences. Both quantitative and qualitative assessments are applied. Quantitatively, it is mainly possible to assess the fiscal impact caused by the occurrence of customs risk. The occurrence of security risks can be assessed mainly qualitatively, for example, based on the impact of a specific risk on human health. The overall risk level is determined by applying a probability and impact matrix.

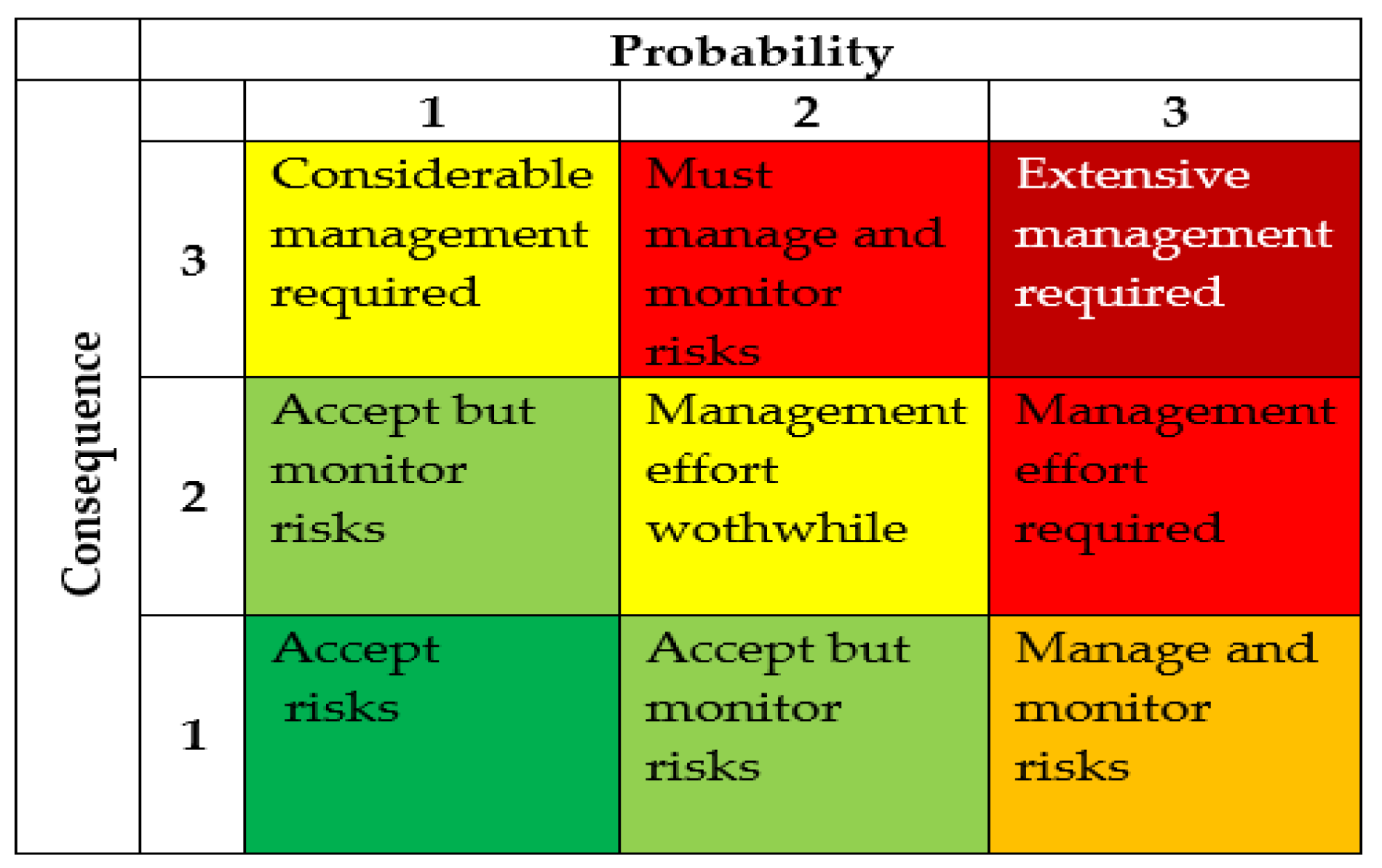

Figure 4 illustrates a 3x3 level matrix, in which the WCO recommends risk management measures tailored to each risk level [

46].

At the tactical management level, there is no defined approach to scientific research in the field of customs, However, in practice, the quantitative assessment model developed by the WCO is used, which is based on the analysis of risk incident statistics collected in the previous period, calculating the percentage of specific customs risk incidents detected in relation to the total number of risk incidents detected. The following equation (3) is used for the calculations:

where

– level of customs risk probability,

– number of specific customs risk incidents per year, Z – total number of customs risk incidents per year. The mathematical values of the probability (P) level range from 0% to over 20% for a high-risk probability assessment. The methodology for assessing the impact and overall level of risk remains unchanged, like the assessment of operational customs risks.

At the strategic risk management level, the customs service assesses the dynamics of risk levels in previous periods, analyses risk event development scenarios, and evaluates the likelihood of new risks emerging or rapidly increasing. For example, after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the risk of circumventing the EU sanctions increased, while after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the risk of circumventing the EU sanctions rose sharply and became catastrophically high. It should be noted that, at both the tactical and strategic levels, the impact of customs risks is assessed cumulatively on an annual basis.

4.5. Risk Analysis Approach to Imported Foodstuffs and Phytosanitary Surveillance

In the field of food safety, risk management is based on the provisions of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Codex Alimentarius Commission [

49]. The risk management system is based on a sustainable risk assessment methodology that is based on the three classic stages of risk management, adapted to food safety and expressed by the equation (4):

The methodology for assessing the level of risk (R) in food safety covers the undesirable effects of hazards on human health (S) (Severity of hazard), the likelihood of exposure (E) (Exposure likelihood), the quality of data, and the impact (I) (Impact) of the hazard on national trade and the economy [

40]. First, the severity of the hazard (S) is assessed. The assessment must identify which biological, chemical or physical factors (hazards) could hurt human health, while determining the nature of the hazard (e.g., pathogenic bacteria, mycotoxins, heavy metals). The hazard characterisation, in turn, involves determining the extent of exposure and its relationship to the probability and severity of adverse effects. The main issues analysed are the severity of the hazard. The main factors assessed are the level of hospitalisation or mortality. To determine this, it is necessary to use scientific literature, surveillance data, and established toxicology and epidemiology [

40]. To assess exposure, the extent, frequency, and duration of human exposure to the hazard through consumption of the food in question are determined. The assessment uses data on concentrations, consumption patterns, the likelihood of contamination, and other factors that influence the extent of exposure. The third factor is the assessment of the threat's impact (I). When assessing this factor, it is necessary to analyse the threat posed to the national economy, trade, or commercial activities of companies. Factors such as the share of exports affected, the impact on national income and farmers' income, as well as possible trade bans and product recalls, can be used as sub-criteria for the assessment. The risk level components (S, E, I) are evaluated using matrices with scales (e.g., 1-5 or 1-10), taking into account available weights.

Pest Risk Analysis (PRA) is a structured and scientifically based process used in the field of phytosanitary safety to assess the potential risks that specific organisms may pose to plants, the environment, and the economy. This analysis is essential to identify whether a particular organism is considered harmful, whether it should be regulated, and what phytosanitary measures would be necessary to mitigate the associated risk. The PRA process is defined in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM 5) and is widely used by member countries of the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). PRA consists of three main stages (initiation, risk assessment, risk management), which provide a comprehensive approach to risk assessment and management and can be expressed by the equation (5):

To assess the risk level (R), the biology of the organism and its potential spread (SP) are analysed, as well as its potential impact (I) on host plants, ecosystems, and economic aspects. Factors influencing an organism's survival, spread, and impact in a region are considered. Quantitative and qualitative data are used at this stage to determine the level of risk. Specific phytosanitary measures are developed for risk management based on the results of the assessment. These may include quarantine requirements, inspection procedures, certification mechanisms, or even bans on the import or movement of certain commodities. The aim is to reduce the risk to an acceptable level while ensuring that the measures are proportionate and do not violate international trade principles. The IPPC has created international standards for PRA, including ISPM 2 (framework), ISPM 11 (methodology for assessing harmful organisms), and ISPM 21 (risk analysis of invasive plants). These standards promote a harmonised approach among countries and provide a scientific basis for phytosanitary decision-making. PRA is a dynamic tool that allows competent authorities to adapt to changing risks, improve the effectiveness of phytosanitary measures, and promote sustainable plant protection. Its application is essential not only at the local level, but also globally, given the increasing intensity of international trade and the associated phytosanitary challenges [

50,

51].

4.6. The Experience of the EU Member States' Customs Services in Managing External Border Security Risks

A questionnaire was sent to the customs administrations of EU Member States to gather information about the experiences of other EU Member States' customs administrations in managing border security risks. A total of 13 Member States' customs administrations responded to the questionnaire. Two questions were asked. (1) "Does your country have a unified risk management system in place with annual risk assessments covering border, immigration, customs, veterinary, phytosanitary, food safety and other risks?" (2) "If a common risk management system has been implemented, is a common methodology applied to the assessment of the above-mentioned risks? If so, we would be very grateful if you could provide an insight into the existing methodology."

This report (

Table 2) summarises the results of the survey. The summary provides information on countries with a common approach, those with partial cooperation, those without a common system, and cooperation with other authorities.

Only a few Member States (notably Finland) have a comprehensive and integrated approach to risk management at external borders. Most countries still use sectoral systems with varying degrees of cooperation. Cross-agency cooperation is more common in countries with mature systems or specific bilateral/multilateral agreements. No common EU-wide methodology has been established, although some countries are developing or are interested in such systems.

4.7. Solutions for Sustainable Common Border Security Risks Management

Sustainable border management faces a variety of security risks that require the development of comprehensive methodological solutions to manage and mitigate these threats. Effective border management must integrate risk management methodologies, ensuring continuous cooperation between international stakeholders, government agencies, and the private sector. Maintaining strong border security requires regular updating and improvement of risk management strategies, including the introduction of new technologies and methodologies.

The development of an integrated risk assessment methodology represents significant progress in organisational risk management. Integrated risk management differs significantly from traditional approaches in its holistic perspective on organisational risk. Instead of managing risks separately, the methodology promotes a holistic system that connects all risk management functions, ensuring complete transparency of potential threats in operational and strategic areas. This holistic approach enables organisations to make more informed decisions while supporting compliance with governance standards and regulatory requirements. The integration of various risk management components creates a more flexible and adaptive organisational structure that can respond more effectively to new challenges. The cornerstone of an effective integrated and sustainable risk assessment methodology is its alignment with the objectives set for the area in question. The risk identification and assessment system should include both qualitative and quantitative elements. Effective and sustainable integrated risk assessment methodologies emphasise cross-functional collaboration and stakeholder involvement. This collaborative approach allows for the identification of potential partnerships with other entities to manage risks specific to the area in question. While methodological advances have been made, border security risk management still faces challenges, including integrating technology, adapting to evolving threats, and ensuring legal consistency across jurisdictions. Additionally, the transition to more digital solutions presents challenges related to data security and privacy that necessitate careful management. Looking ahead, attention should be paid to enhancing the adaptability of existing methodologies to incorporate emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and blockchain. These technologies have the potential to automate risk assessment processes and improve data management, thereby ensuring more effective border security operations. By using these methodological innovations, border management authorities can better protect national interests while facilitating the lawful cross-border movement of persons and goods. The state should be considered the owner of the border and the primary responsible party, and border security should be viewed as an indivisible concept. Customs, border guards, and other border managers currently oversee and assess multiple risk management models with varying functions and priorities. The creation of a sustainable common risk management framework at the border will ensure more effective management, more reliable results, protection of all interests, faster manoeuvring and changing of priorities, as well as better use of resources. Each risk assessment method used by border management services has its own strengths and weaknesses, which should be considered when creating a unified risk model. The risk assessment methodology included in CIRAM 2.1 is well structured. Its three-factor analysis ensures a consistent approach to each component of risk assessment. The results of the analysis are comparable across different dimensions. The CIRAM 2.1 methodology utilises a broad range of analytical evidence, including historical data, intelligence data, expert judgments, and trend analysis. The analysed levels of threat, vulnerability, and impact are interrelated and help to adapt to different border security contexts and data availability. CIRAM 2.1 is used not only in the event of immediate threats, but also to assess "megatrends" (climate change, geopolitical changes, etc.). In relation to migration, cross-border crime, return, and other issues, it is helpful to anticipate future risks [

44]. However, CIRAM 2.1 has several shortcomings. For example, CIRAM 2.1 does not offer clearly defined criteria and methods for assessing factors that influence the level of risk. Consequently, the skills and abilities of risk analysts in evaluating a wide range of information significantly influence the results of the risk analysis. Although flexibility is a strength, risk analysis places a relatively high emphasis on expert judgment or qualitative assessments, which can lead to bias and differing interpretations among analysts. The statistical or empirical basis is sometimes limited. It should be noted that assessment data is often classified, which limits transparency and the ability to use it in other services. [

52].

Customs services employ various methods at different levels of border management. At the operational (lowest) level, the probability of risk occurrence is assessed based on the evaluation of a set of risk indicators. At the tactical and strategic levels, a historical data analysis model is used. At all levels of risk management, the risk management method is based on a combination of probability and impact, but this analysis does not include vulnerability analysis. Customs reduce risk by setting tasks and priorities. The methodology used in the field of food safety is focused on determining the level of risk for specific shipments; the tactical and strategic level risk management methodology is not analysed in depth.

When reviewing the border security risk assessment models used by border control services, it is worth noting that they are based on probability and impact assessments using the matrix method [

12]. At the tactical and strategic levels, however, a wide range of methods are used to determine the probability of border security risks occurring. These include threat assessment scenario-based analysis and expert judgment to estimate probabilities when data is limited [

53], survey-based estimation for visa overstays and unregistered entries [

54], and historical trend analysis using past data to forecast future risks and their levels [

46].

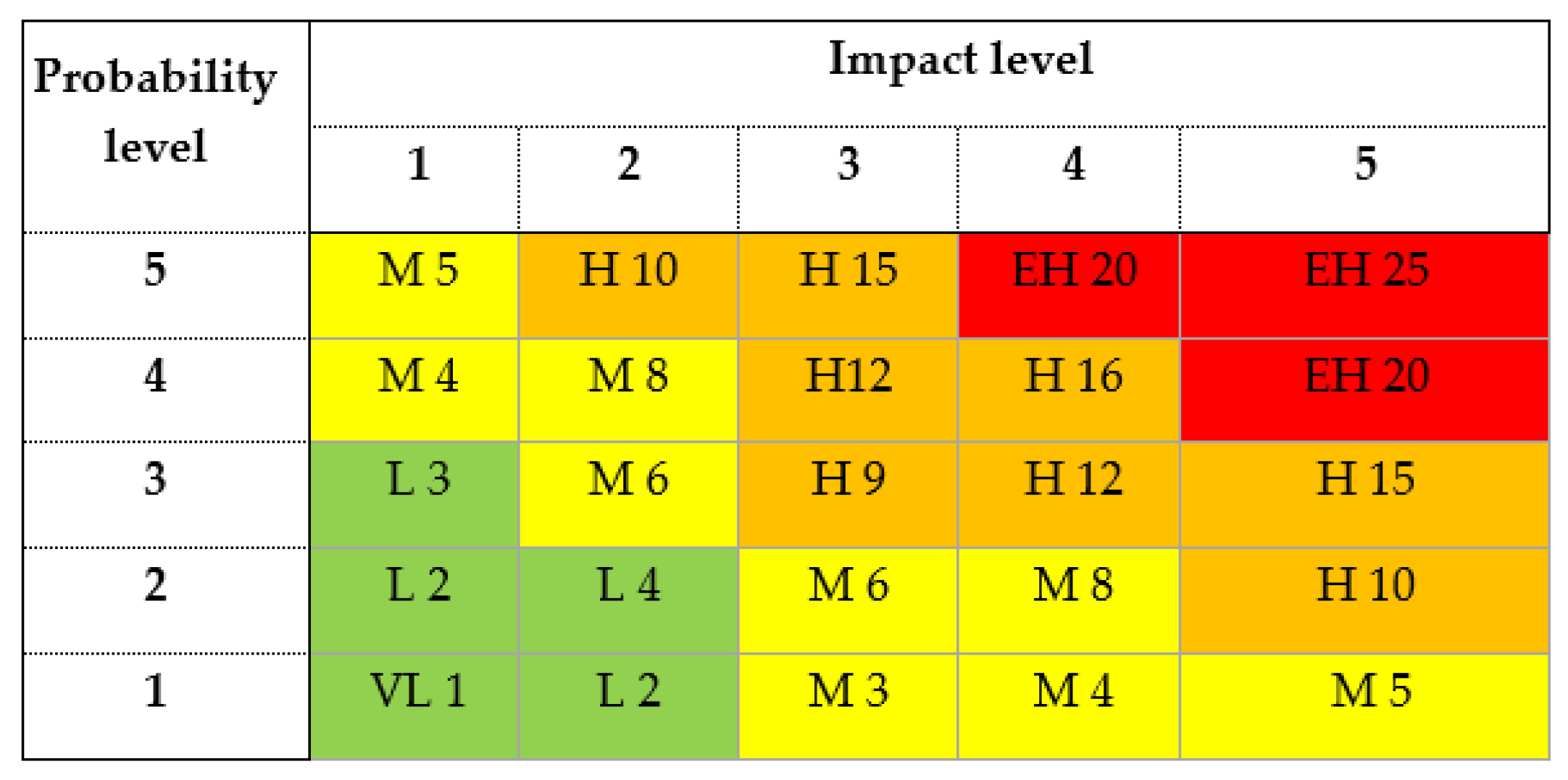

The authors propose a probability and impact assessment using the matrix method as the primary basis for a unified tactical-level border security risk assessment methodology, clearly defining a scale of criteria for determining the probability and impact levels of each border security risk.

The World Customs Organisation's (WCO) recommended customs risk assessment method uses a 3x3 matrix assessment method to evaluate risk probability, impact, and overall risk level. The CIRAM 2.1 model also provides a 3-level assessment model for assessing threats, vulnerabilities, and impacts. When applying such methods, the risk level is divided into high, medium, and low. The 3x3 risk management model simplifies risk assessment by categorising risks as high, medium, or low, making results easy to communicate and understand. At the same time, it should be noted that such a simplified approach creates shortcomings in the risk management process, because the range of criteria for determining probability and impact in the risk assessment results is sufficiently broad at each level, which in turn means that, for example, a relatively large number of shipments fall into the medium risk level, which in turn creates challenges in determining the need for appropriate risk mitigation measures and increases the risk that significant threats may not be adequately controlled and will have consequences for public safety.

The Customs Risk Management Framework (CRMF) proposed by the EU TAXUD suggests using the 5x5 matrix method for risk assessment. The assessment of 5x5 level risk elements is more complex, as it requires more detailed criteria for each level and more in-depth data analysis to ensure that the relevant risk assessment elements and results comply with the established framework. However, the result obtained is of higher quality and ensures greater consistency in assessing the flow of goods. The authors believe that an equivalent benefit will be achieved by applying a 5x5 level risk element assessment in the migration and veterinary, phytosanitary and food safety risk management process, developing specific indicators for formulating risk impact and probability level thresholds. Therefore, for those border security risks that are common to both the border guard and customs services, as well as in the areas of veterinary, phytosanitary and food safety, the authors recommend using the risk probability and impact criteria scales approved by the Latvian Customs Service, which are based on CRMF recommendations (see

Figure 5).

To assess the impact of border security risks, the authors propose a 5-level matrix, where quantitative and qualitative criteria for each level are determined based on empirical measurements in each country, taking into account the specifics of national legislation. For example, it is not possible to define uniform indicators characterising the level of impact of drugs, because in Germany, for example, the use of marijuana for personal needs is permitted, while in Latvia, transporting it across the border is a criminal offence. The ranking of criteria for the public safety and security risk and corruption risk impact level matrix is shown in

Appendix A. The border security risk assessment matrix (

Figure 6) has been developed by combining the assessment levels determined in the border security risk probability and impact matrices into a single model. The developed solution offers a unified approach to border security risk assessment and the development of a corresponding action plan. It can be used not only for border security but also for fiscal and strategic risk assessment, by supplementing the assessment matrix with criteria formulations and an appropriate indicator scale.

5. Conclusions

This study examines external border security risk management to identify the primary benefits of sustainable common border security risk management and the methodological solutions that can support sustainable external border security. Based on the results reported in this paper, the following conclusions are drawn.

Effective border security requires a unified and coordinated approach, as traditional fragmented systems are no longer sufficient to address today's complex and interconnected threats. The involvement of many agencies with overlapping responsibilities and reporting to different ministries creates significant difficulties in coordination and information sharing. Although international frameworks and models for integrated border management exist, most of the EU Member States have not yet implemented comprehensive risk management systems. Strengthening inter-agency cooperation, harmonising procedures, and improving IT system integration are essential steps toward more effective border security.

In summary, the results show the need for a unified and sustainable risk management approach at the tactical (one-year) level, supported by research and experience. To address evolving global threats, EU Member States should adopt a unified and sustainable border security risk management model that enhances coordination, efficiency, and resilience among all border control authorities. Common risk management allows for better use of available resources, reducing costs and improving operational efficiency.

An integrated approach allows for faster and more accurate identification and prevention of threats, including organised crime and smuggling. Reducing bureaucracy and improving the transparency of processes facilitates the flow of goods and people, while a common approach promotes trust and information exchange at the international and national levels. In this study, the authors propose a unified approach to security risk assessment. At the same time, the authors encourage further research into specific elements of the risk management system, where opportunities for integration should be explored, and cooperation among various stakeholders should be enhanced. Thus, a significant contribution to research would be the application of common risk management model elements in practice and the analysis of the resulting data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.K.-A. and A.A.; methodology, S.K-A., A.G. and A.C.; software, S.K.-A. and N.R.; validation, S.K.-A., N.R., L.G. and A.C.; formal analysis, S.K.-A., N.R., A.C. and A.A.; investigation, S.K.-A., N.R. and A.A.; resources, A.C. and L.G.; data curation, S.K.-A. and N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.-A., N.R. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, S.K.-A., A.A. and A.G.; visualisation, N.R.; supervision, A.C., A.G., L.G. and A.A.; project administration, A.G., A.C.; funding acquisition A.G., A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by RD grant No. RTU-PA-2024/1-0042 under the European Union Recovery and Resilience Mechanism funded project No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| CIRAM |

Common Integrated Risk Analysis Model |

| CRMF |

Customs Risk Management Framework |

| ERM |

Enterprise Risk Management |

| EU |

European Union |

| EUROSUR |

European border surveillance system |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations |

| FRONTEX |

European Border and Coast Guard Agency |

| FVS |

Food and Veterinary Service |

| IBM |

Integrated border management |

| ICT |

Information and communication technologies |

| IPPC |

International Plant Protection Convention |

| ISPM |

International standard for phytosanitary measures |

| PRA |

Pest risk analysis |

| SAFE |

Standards to secure and facilitate global trade |

| SP |

Spread potential |

| TAXUD |

Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union of the European Commission |

| WCO |

World Customs Organisation |

| WTO |

World Trade Organisation |

Appendix A

Assessment of the Impact of External Border Security Risks

| Impact |

Type of impact |

Description of impact |

| |

5

(extremely high)

|

National/

EU budget losses |

Importation of contraband goods causes national/ EU budget losses, exceeding Y × 1,000 euros annually |

| Threat to public safety and security |

Significant threats to public safety and health, environmental threats, including:

narcotic, psychotropic, new psychoactive substances, and precursors: signs of a criminal offence are evident (criminal proceedings have been initiated); goods whose movement is subject to sanctions imposed; goods of strategic importance – signs of a criminal offence have been identified in connection with the movement of goods of strategic importance; weapons (all types of weapons of mass destruction, their raw materials and military technology); cash – signs of a criminal offence are evident in the non-declaration of cash; organised crossing of the border by groups of illegal migrants outside border crossing points; organised support for illegal migration detected; mass use of forged travel documents; trafficking in human beings; very high risks in food, phytosanitary and veterinary controls.

|

| Reputation |

Damage to the reputation of border management services at the international level has been raised in the international media, resulting in a loss of national public support |

| |

4

(high)

|

National/

EU budget losses |

Losses to the national or EU budgets from a single risk event range from Yx100 to Yx1000 euros per year |

| Threat to public safety and security |

Threats to personal safety and health, threats to the environment, including:

narcotic, psychotropic, new psychoactive substances, and precursors are detected; an administrative proceeding has been initiated because strategic goods were handled without the required official license; cash – administrative proceedings have been initiated for undeclared cash; violations of intellectual property rights: more than 1000 units of one trademark in one shipment; goods that pose a danger to consumers; illegal migrant groups crossing the border outside border crossing points; detected support for illegal migration; use of forged travel documents; high risks in food, phytosanitary and veterinary controls.

|

| |

|

Reputation |

Damage to the reputation of the border management services at the national level has been raised in the national media, with negative publications on social networks |

| |

3

(medium)

|

National/ EU budget losses |

Losses to the national or EU budgets from a single risk event range from Yx10 to Yx100 euros per year |

| Threat to public safety and security |

Threat to personal safety and health, including where undeclared goods are found because of customs control measures:

violations of intellectual property rights: from 11 to 999 units of a single trademark in a single consignment; goods are subject to restrictions or prohibitions; violation of the border and border regime; medium risks in food, phytosanitary and veterinary controls.

|

| Reputation |

Various adverse reports have been published in the national and regional media, and there have been negative publications on social networks about the reputation |

| |

2

(low)

|

National/ EU budget losses |

Losses to the national or EU budgets from a single risk event range from Y to Yx10 euros per year |

| Threat to public safety and security |

Threat to personal safety and health, including if customs control measures result in the detection of undeclared goods that infringe intellectual property rights – up to 10 units of a single trademark in a single consignment

Insignificant border and border regime violations.

Low risks in food, phytosanitary and veterinary controls |

| Reputation |

Negative news published in local media or on social networks does not typically lead to increased public interest |

| |

1

(very low)

|

National/ EU budget losses |

Losses to the national or EU budget from a single risk event are up to EUR Y per year. |

| Threat to public safety and security |

No threat to personal safety and health |

| Reputation |

No attention from the local community/media |

References

- Jankowska-Ambroziak, E.; Niedzwiecki, A.; Proniewski, M. The complexity of European border control system and illegal migration issue. Communications of International Proceedings. 2024, 2024. Available online: https://ibimapublishing.com/p-articles/44PublicAdm/2024/4454424/.

- Georgescu, E. Challenges of illegal migration in the context of Romania’s accession to the Schengen area. In Proceedings of the Strategies XXI International Scientific Conference: The complex and dynamic nature of the security environment, 21st ed.; Cîrciumaru, F., Lică, D., Eds.; Carol I National Defence University Publishing House, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taute, B. Integrated control of the South African border environment. South African Joint Air Defence Symposium 2007, Pretoria, 30-31 May; 2007; p. pp. 7. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/82684461/Integrated_control_of_the_South_African_border_environment (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Doyle, T. Collaborative border management. World Customs Journal 2010, 4(1), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter American Development Bank. Interoperability at the border: coordinated border management best practices & case studies 2011. [CrossRef]

- McLinden, G. Collaborative border management: A new approach to an old problem. In Economic Premise; Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Network, World Bank, 2012; Volume No. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Deliversky, J. “ILLEGAL MIGRATION PROCESSES MANAGEMENT IN THE LIGHT OF THE NEW EUROPEAN UNION PACT ON MIGRATION AND ASYLUM”. ETR 2024, vol. 4, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortey, L.; Edwards, D.J.; Roberts, C.; Rillie, I. A review of safety risk theories and models and the development of a digital highway construction safety risk model. Digital 2022, 2(2), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Risk society: Towards a new modernity; Ritter, M., Translator; Sage Publications, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Wildavsky, A. Risk and culture: An essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers; University of California Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Karklina-Admine, S.; Cevers, A.; Kovalenko, A.; Auzins, A. Challenges for customs risk management today: A literature review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2024, 17(8), 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex). Common integrated risk analysis model (CIRAM): Monitoring and risk analysis. 2025. Available online: https://www.frontex.europa.eu/what-we-do/monitoring-and-risk-analysis/ciram/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Polner, M. Coordinated border management: From theory to practice. World Customs Journal 2011, 5(2), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Rijpma, J. The management of the European Union’s external borders. In Research handbook on EU migration and asylum law; Tsourdi, E., De Bruycker, P., Eds.; 2022; pp. 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.; Bersin, A. Collaborative border management. World Customs Journal 2020, 14(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V. P. Towards a common European border security policy. European Security 2010, 19(2), 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylönen, M.; Aven, T. A new perspective for the integration of intelligence and risk management in a customs and border control context. Journal of Risk Research 2023, 26(4), 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. K.; Ruiter, J.; Häring, I.; Fehling-Kaschek, M.; Stolz, A. Design, simulation and performance evaluation of a risk-based border management system. Sustainability 2023, 15(17), 12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K. E. Security risk management. In The professional protection officer: Practical security strategies and emerging trends; IFPO, Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2010; pp. 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. Invisible border security: Vulnerabilities and risks to New Zealand’s resilience. National Security Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, F.; Gavrilă, S.P. Strengthening cooperation for customs risks management at European borders in the new regional security context. In Proceedings of the 10th SWS International Scientific Conference on Social Sciences – ISCSS 2023, 2024; SGEM World Science (SWS) Scholarly Society; Vol. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.; Grater, S.; Venter, W. C.; Maree, J.; Liebenberg, D. Designing a new methodology for customs risk models. World Customs Journal 2019, 13(1), 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousan, M. S. A.; Intrigila, B. A data-sharing model to secure borders using an artificial-intelligence-based risk engine and big-data concepts. American Journal of Applied Sciences 2022, 19(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussama, R.; Nacer, B.; Wissam, A. Role of artificial intelligence in managing customs risk for Algerian customs. Les Cahiers Du Cread 2024, 40(1), 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I. G.; Caballero, A. M. A multi-objective bayesian approach with dynamic optimisation (MOBADO). A hybrid of decision theory and machine learning applied to customs fraud control in Spain. Mathematics 2021, 9(13), 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rаts, О.; Alfimova, A. Current approaches of the EU countries to customs risk management and their implementation in the customs activities of Ukraine. Бізнес-Навігатoр 2024, 4(77), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Gupta, P.; Sijariya, R.; Sharma, Y. K. Artificial intelligence in risk management. In Artificial intelligence for risk mitigation in the financial industry; Mishra, A. K., Anand, S., Debnath, N. C., Pokhariyal, P., Patel, A., Eds.; Scrivener Publishing LLC, 2024; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Chou, S.-C. Manifest monitoring model as support for customs risk management: Evidence from Taiwan. World Customs Journal 2021, 15(2), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumei, M.; Kveliashvili, I.; Kazantsev, S.; Hranyk, Y.; Akimov, O.; Akimova, L. Directions and prospects of the application of artificial intelligence in customs affairs in the context of international relations. AD ALTA, Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 2024, 14(1), 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livdāne, J.; Arbidāne, I. Intelligence cycle as part of effective risk analysis under integrated border management. Journal if Internal Security and Civil Defence Sciences 2020, 3(8), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmutovic, A.; Alhamoudi, A. European border security rethinking the concept of open borders. PETITA Jurnal Kajian Ilmu Hukum dan Syariah 2023, 8(2), 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdowson, D. Managing customs risk and compliance: an integrated approach. World Customs Journal 2020, 14(2), 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, E.; Aliu, F.; Emini, E. ISO 31000:2018 – Risk management guidelines [White paper]. PECB Group Inc. 2018. Available online: https://pecb.com/whitepaper/iso-310002018-risk-management-guidelines (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Schneller, L.; Porter, C.N.; Wakefield, A. Implementing converged security risk management: drivers, barriers, and facilitators. Security Journal 36 2022, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015 (News Release 44/2016). 4 March 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). Global peace index 2024: Measuring peace in a complex world. 2024. Available online: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/GPI-2024-web.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- World Bank Group. Metadata: World development indicators (WDI). 2024. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Aniszewski, S. Coordinated border management – a concept paper. (WCO Research Paper No. 2). World Customs Organization. 2009. Available online: https://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/topics/research/research-paper-series/cbm.pdf?la=en (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). Enterprise risk management – Integrating with strategy and performance. 2017. Available online: https://www.coso.org/guidance-erm (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- European Commission. Effective management of external borders. 2023. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen/effective-management-external-borders_en (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- World Customs Organization (WCO). Coordinated Border Management Compendium. 2023. Available online: https://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/facilitation/activities-and-programmes/coordinated-border-management.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Policy and technical considerations for implementing a risk-based approach to international travel in the context of COVID-19. 2 July 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/policy-and-technical-considerations-for-implementing-a-risk-based-approach-to-international-travel-in-the-context-of-covid-19 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Biljan, J.; Trajkov, A. Risk management and customs performance improvements. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 44, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex). The Strategic risk analysis report; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzevari, M.; Sajadi, S. M.; Molana, M. H. Supply chain reconfiguration for a new product development with risk management approach. Scientia Iranica, International Journal of Science and Technology 2019, 27(4), 2108–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Customs Organization (WCO). Risk management compendium. 2009, Vol. 1. Available online: https://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/activities-and-programmes/risk-management-and-intelligence/risk-management-compendium-volume-1.pdf?db=web (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 31000:2018; Risk management: Guidelines. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 31010:2019; Risk management: Risk assessment techniques. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FAO. Risk based imported food control manual (Food Safety and Quality Series No. 1). 2016. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e7b45c96-7727-4e11-9b5b-ba5aaafac5f1/content (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FAO. FAO guide to ranking food safety risks at the national level (Food Safety and Quality Series No. 10). 2020. [CrossRef]

- International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). (n.d.). PEST risk analysis – PRA process. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/centre-of-excellence/phytosanitary-systems/contributed-resources-pest-risk-analysis/pest-risk-analysis-pra-process/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the evaluation of Regulation (EU) 2019/1896 on the European Border and Coast Guard, including a review of the Standing Corps (Commission staff working document). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52024DC0075 (accessed on 11 November 2025).