1. Introduction

Raman spectroscopy, a nondestructive analytical technique, can infer the composition and structure of a sample by analyzing the Raman spectrum contained in the scattered light [

1]. It is based on a phenomenon first reported in 1928 [

2] and is used for component analysis. Although methods for detecting trace substances in liquid samples include antigen–antibody reactions [

3], polymerase chain reaction [

4], and liquid chromatography [

5], Raman spectroscopy is advantageous owing to its ability for quick analysis without sample pretreatment [

6], and comprehensive analysis [

7], including unknown substances [

8]. However, a drawback of typical Raman spectroscopy is its relatively low detection sensitivity [

9].

To record the Raman spectrum of a liquid sample, the sample is typically placed in a small container such as a glass bottle [

10], a glass [

11], or quartz glass [

12] and irradiated with a laser. For samples with low concentrations of components, increasing the laser power or prolonging the irradiation time increases the risk of thermal damage to the sample. As the intensity of Raman scattered light is inversely proportional to the square of the wavelength of the excitation light, using shorter wavelength excitation light can produce a Raman spectrum with higher scattered light intensity [

13]. However, using shorter wavelength excitation light can result in strong autofluorescence from the sample, resulting in increased noise in the Raman spectrum [

14]. Another method involves placing a droplet of the sample onto a surface of glass plate [

15] or metal surface such as stainless steel [

15] or aluminum [

16], and drying it to concentrate it. However, dried samples are often thin, making it difficult to focus the laser on the sample, which can make it difficult to obtain a Raman spectrum with a high signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). Apart from glass and metals, calcium fluoride [

17] is also used; however, it generates Raman scattered light, raising concerns that it may affect the Raman spectrum of the sample. Silicon is also used as a substrate for Raman spectroscopy [

18], but because silicon also emits Raman scattered light, it is often used in combination with other materials such as silver. Techniques such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy [

19], resonance Raman spectroscopy [

20], and tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy [

21] have been developed to improve detection sensitivity. Noble metals such as gold [

22] and silver [

23] are sometimes used as substrates for Raman spectroscopy simply as metals, but they can also be used to obtain surface-enhanced Raman scattering light. It is thought to amplify Raman scattering through the electric field effect caused by surface plasmon resonance [

24] and the charge transfer effect caused by charge transfer between adsorbed molecules and the metal surface [

25]. However, the extent to which Raman scattering is enhanced is unstable and difficult to control. In resonance Raman spectroscopy, Raman scattering is significantly enhanced when the wavelength of the excitation light approaches or coincides with the electronic absorption band of a molecule. This method can increase the detection sensitivity of specific molecules, but the types of molecules that can be targeted are limited [

26]. Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy utilizes the electric field enhancement that occurs at the tip of a plasmon-responsive metal tip to achieve nanometer spatial resolution, exceeding the diffraction limit of light. However, it requires specialized equipment and is technically difficult to perform, making its practical application limited [

27].

Recently, Raman spectroscopy using blood has been applied for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer [

28], lung cancer [

29], breast cancer [

30], endometrial cancer [

31], and head and neck cancer [

32]. The use of Raman spectroscopy to analyze urine for prostate cancer diagnosis has also been reported [

33]. However, a standard cancer diagnostic technique using Raman spectroscopy has yet to be established. We have been developing disease screening techniques using Raman spectroscopy [

34,

35]. Our goal was to develop a simple and quick diagnostic technique for several major diseases, including cancer, using biological fluid samples such as serum and urine, overcoming the effects of autofluorescence and low detection sensitivity without compromising the advantages of Raman spectroscopy, such as speed and simplicity [

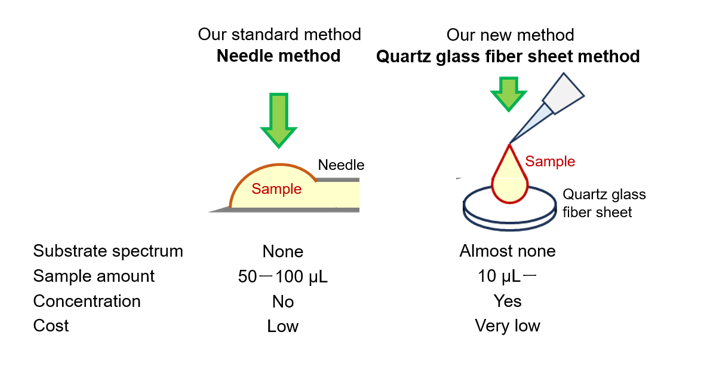

15]. To achieve this, obtaining high-quality Raman spectra with high sensitivity and low noise are necessary. Therefore, we proposed a quartz glass fiber sheet as a substrate for Raman spectroscopy, based on the hypothesis that the sheet will retain the liquid biological sample and that drying will concentrate the components in the sample, increasing the intensity of the Raman scattered light.

4. Discussion

We are currently investigating the use of Raman spectroscopy in human body fluid samples, such as serum and urine, to aid in the early diagnosis of diseases [

34,

35]. We aimed to establish a simple method for obtaining high-S/N Raman spectra from human serum and urine containing relatively low concentrations of components. Two measurement methods, NM and QSM, were evaluated using test samples (sodium benzoate and sodium sulfate), as well as human serum and human urine. Thus, we successfully obtained a Raman spectrum with a high S/N ratio from a small sample volume of 10 μL in a short time of 10 seconds. Furthermore, we succeeded in increasing the intensity of the Raman scattered light by increasing the number of times the sample was dropped onto the quartz glass fiber sheet. In summary, the quartz glass fiber sheet used as the Raman spectroscopy substrate in QSM has the following advantages: the Raman spectrum of the material itself is almost invisible; the concentration of components can be increased by repeatedly dropping samples onto the sheet, thereby improving detection sensitivity; comprehensive analysis is possible because there are no restrictions on the target to be detected; the technique is simple; it is quick and inexpensive.

Raman spectra of sodium benzoate and sodium sulfate were successfully recorded using both NM and QSM. Although the Raman shifts of the peaks in the solid and aqueous spectra recorded with NM were different, the shapes of the Raman spectra recorded with QSM matched those of both solid samples of sodium benzoate and sodium sulfate. In aqueous solution, sodium benzoate exhibits a peak at approximately 1390 cm

-1, which is attributed to the symmetric stretching motion of the carboxylate group (COO

-) dissociated from the carboxylic acid group (-COOH). In the solid state, peaks at approximately 1435 cm

-1 are attributed to the symmetric bending vibration of the methyl group (CH

3), the bending vibration of the methylene group (CH

2), the skeletal vibration of the benzene ring, and the C-O stretching motion. However, no peak near 1390 cm

-1 was observed [

31,

32]. In this study, a peak was observed at 1393 cm

-1 using the NM, whereas in the solid state and using the QSM it appeared at 1435 cm

−1. The peak due to the symmetric stretching motion of the sulfate ion (SO

42-) in sodium sulfate shifts based on the concentration of the sulfate ion (SO

42-), appearing at approximately 981 cm

-1 in aqueous solution and at approximately 994 cm

-1 in the solid state [

37]. In this study, a peak was observed at 980 cm

-1 using the NM, and at 994 cm

-1 in the solid state and using the QSM. These findings suggest that samples measured using QSM crystallize within the quartz glass fiber sheet. Consequently, each drop of sample concentrates the components, increasing the scattered light intensity in the Raman spectra. We recorded the Raman spectrum of the serum using QSM. A positive correlation was observed between the number of drops and the scattered light intensity, and a similar trend was observed in urine. Compared with NM, QSM was obtained ~7.3 times the scattered light intensity in serum and ~7.8 times the scattered light intensity in urine. Our QSM substrate does not cause strong Raman scattering light but rather crystallizes and concentrates sample components within the fiber structure. Therefore, compared to Raman spectra of serum and urine samples obtained using substrates such as glass plates [

15], stainless steel [

15], aluminum [

16], calcium fluoride [

17], and silicon [

18], the scattered light intensity is sufficiently high, and noise is low. Furthermore, the QSM substrate is less susceptible to autofluorescence, resulting in no baseline rise. Furthermore, compared to surface-enhanced Raman spectra obtained using substrates such as gold [

22] and silver [

23], the QSM substrate offers advantages such as comprehensive detection without target restriction, simple and easy handling, and low cost. These features make it an excellent substrate for Raman spectroscopy, suitable for a wide range of applications.

In our measurements, the scattered light intensity of the serum or urine Raman spectra varied depending on the position on the sheet, and the position of maximum scattered light intensity changed depending on the number of drops of serum or urine (

Figure 4a–c, 5a–c). To understand the distribution of ingredients on the sheet, Raman spectra were recorded at multiple locations on the sheet, and the scattered light intensity of the Raman spectrum varied depending on the location on the sheet. As a result, as the amount of sample added increased, the area with the highest scattered light intensity shifted from the edge toward the center. This tendency was also common to both serum and urine. When serum or urine is dropped onto a quartz glass fiber sheet, it spreads horizontally owing to surface tension, as shown by Young’s equation [

40] and moves vertically owing to adsorption. The spreading of serum or urine is influenced by the surface tension of the liquid and the surface tension (surface free energy) of the solid (the quartz glass fiber sheet). The magnitude of surface free energy and the magnitude of spreading are correlated [

41]. In liquid samples, the “coffee ring” phenomenon [

42] occurs; components migrate outward due to convection caused by evaporation from the sample surface. When serum was dropped onto a quartz slide glass, the sample was observed to be thicker at the edges and thinner at the center, suggesting that the “coffee ring” phenomenon occurred on the quartz slide glass. Raman spectra obtained using a quartz glass fiber sheet showed that when the number of drops of serum was small (one and five drops), the Raman scattered light intensity tended to be slightly higher at the outer edge of the sheet. With increasing drops (five and ten drops), the position where the maximum Raman scattered light intensity was recorded tended to shift toward the center. A similar phenomenon was observed for urine, but the position at which the maximum Raman scattered light intensity was recorded tended to easily shift toward the center with increasing number of drops than with serum. This result can be explained by the “coffee ring” phenomenon. When a single drop of sample was applied to a quartz glass fiber sheet, the components in the sample migrated outward. However, due to the high adsorption capacity of the quartz glass fiber sheet (the first drop was absorbed almost instantly), the components may have been adsorbed to the sheet before they could migrate sufficiently outward, resulting in no significant difference in Raman scattered light intensity at the sheet position. When a sample is dropped onto the sheet multiple times, in addition to the components in the newly dropped sample, some of the components adsorbed to the sheet may redissolve and move again on the sheet. In this way, the components repeat a cycle of adsorption, redissolution, movement, and adsorption on the sheet, which may gradually lead to a more uniform distribution of components on the sheet. Dropping a drop of sample followed by a drop of water or other solvent and analyzing the change in Raman scattered light intensity with position on the sheet may reveal the adsorption and movement of components. However, serum components are diverse, and it is assumed that they move in a very complex manner. The surface of the quartz glass fiber sheet was observed under a microscope after serum application, and a fine granular structure relatively similar to the original quartz glass fiber sheet was observed after the application of one drop of serum. After three drops of serum were applied, a clear change was observed, with a slightly coarse granular structure observed from the edge to the middle, but the center was a mixture of fine and slightly coarse granules. After five and ten drops of serum were applied, a rock-like structure was observed from the edge to the center in both cases (

Figure 6). The area with the maximum scattered light intensity on the quartz glass fiber sheet shifted from the edge to the center depending on the number of serum drops applied and the state of the sheet surface. This indicates that the amount of serum components adsorbed and solidified on the fibers increased, the structure changed from fine granular to coarse granular to rock-like, and that this change progressed from the edge to the center. Experiments using a quartz slide and serum suggested that serum spreads in a circular shape, but with a single 10-μL drop, components concentrated between the center and the outermost periphery, and with increasing drop counts, components also concentrated toward the center (

Figure 7a–d). This phenomenon coincides with the phenomena in which the shape of the sheet surface and the position on the sheet showing the highest Raman scattering light intensity moves from the edge toward the center depending on the number of times the sample is dropped. As in this experiment we focused on permeability changes, determining the differences in the migration patterns of individual serum components was not possible. However, inverse correlation existed between the number of drops of serum and spreading. As the surface tension of serum and urine does not change, increasing the number of serum and urine drops is speculated to change the surface conditions of the quartz glass fiber sheet and quartz glass slide, resulting in a decrease in the surface free energy. The presence of organic matter decreases surface free energy [

43]. Therefore, the surface free energy of the quartz glass fiber sheet and quartz glass slide may decrease with an increasing number of drops of serum and urine. In contrast, the rougher the surface and the larger the surface area, the higher the surface free energy, whereas the smoother the surface and the smaller the surface area, the lower the surface free energy [

44]. In the case of the quartz glass fiber sheet, the drops of serum and urine fill the gaps between the fibers, making the surface smoother and reducing the surface area, which is thought to decrease the surface free energy. Serum or urine droplets placed at the center of a quartz glass fiber sheet are thought to pass through the sheet owing to surface tension and adsorption according to Young’s equation [

40,

41]. It is also assumed that components move within the sample droplets due to the “coffee ring phenomenon” [

42] or the like. However, the migration of serum and urine components is thought to be affected by various factors, including molecular weight, size, and charge. Serum contains a variety of components, including proteins such as albumin and globulin, amino acids, glucose, lipids, electrolytes, and hormones. Meanwhile, urine has a simpler composition than serum, with its main components being urea, creatinine, uric acid, sodium, potassium, magnesium, and urobilin. Differences in serum and urine components are thought to affect the relationship between the number of sample droplets and scattered light intensity. Adjusting the properties of the quartz glass fiber sheet, such as its density and thickness, it is possible to achieve a uniform distribution of components on the sheet, while at the same time controlling the heterogeneity may enable selective detection of components in the sample.

Serum and urine contain disease-related proteins, amino acids, glycans, and nucleic acids. Therefore, high-S/N Raman spectra obtained using comprehensive Raman spectroscopy may provide valuable information for disease diagnosis. Morasso et al. analyzed the Raman spectra of dried plasma from 120 patients and reported that by focusing on peaks representing tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, lipids, carotenoids, and disulfide bonds, colon cancer patients could be identified and monitored with 87.5% accuracy [

28]. Jo K et al. revealed the possibility of identifying colorectal cancer patients using spectral data obtained from colonic mucus using a plasmonic gold nanopolyhedron-coated needle-based surface-enhanced Raman scattering sensor [

45]. Xu et al. reported that detecting lung cancer-associated circular RNA using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and a unique optical biosensor is useful for lung cancer screening and prognosis prediction [

29]. Hajab et al. claimed that analyzing proteins contained in specific fractions obtained by serum centrifugation using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy was able to diagnose breast cancer patients with 81% sensitivity and 76% specificity [

30]. Furthermore, Schiemer et al. compared the accuracy of endometrial cancer detection using ATR-FTIR and Raman spectroscopy using plasma and dried plasma, reporting a 78% accuracy for ATR-FTIR, 82% accuracy for Raman spectroscopy, and 86% accuracy for the combined method [

31]. Koster et al. reported that the combined Raman spectral analysis of plasma and saliva had diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 96.3% and 85.7%, respectively, for head and neck cancer patients [

32]. Li et al. analyzed the plasma of 199 patients with esophageal cancer and 135 healthy individuals using resonance Raman spectroscopy and reported that it was useful for diagnosing esophageal cancer and assessing its progression [

46]. Yang J et al. reported an in vitro cancer cell detection technique using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and silver nanoprobes [

47]. Mitura et al. analyzed the Raman spectrum of urine and stated that the scattered light intensity of the Raman shift peaks at 1009 cm

-1 and 2937 cm

-1 was strongly related to prostate cancer [

33]. Desroches J et al. reported that they developed a quick cancer cell detection system using high-wavenumber Raman spectroscopy and were able to evaluate cancerous lesions in pig brain tissue in real time [

48]. Uckermann et al. demonstrated the possibility of detecting brain tumors by simultaneously acquiring and analyzing Raman scattered light and near-infrared autofluorescence from the brain during brain surgery [

49]. Chen et al. also presented a needle-type Raman spectroscopy system with near-infrared autofluorescence imaging capabilities for distinguishing between breast cancer and normal breast tissue [

50]. Although applying Raman spectroscopy in the medical field is gradually progressing, standard methods for disease diagnosis have yet to be established, and many techniques require complex procedures. Our QSM technique is characterized by its relatively simple nature and is advantageous in that it is easy, quick, and provides highly reproducible Raman spectra.

In this study, we used the QSM too quickly and easily obtain high-S/N Raman spectra from serum and urine samples. However, it should be noted that this QSM method dries the measurement sample, so it may not be possible to accurately evaluate volatile substances or substances that change due to temperature changes, drying, or light exposure. Using a circular quartz glass fiber sheet as a substrate for Raman spectroscopy measurements, we found that components in the sample can crystallize within the quartz glass fiber structure, that the Raman scattered light intensity increases as the amount of sample dropped increases, that the Raman scattered light intensity changes depending on the measurement position on the sheet, and that the peak of Raman scattered light intensity tends to move from the edge of the sheet toward the center depending on the amount of sample dropped. However, we have not been able to confirm whether the change in scattered light intensity results in a change in the proportions of the Raman spectrum. To use our QSM in clinical testing, we need to fully understand, control, and utilize the mechanisms underlying the changes in the Raman spectrum on the sheet. In this study, we found that the Raman scattering intensity changes with position on the sheet, but it is not yet clear whether the spectral shape also changes. If the spectral shape itself changes, it would indicate that components in the sample move along the sheet according to different rules. We need to decide whether to make the QSM sheet uniform or to control its heterogeneity for selective detection. Of course, we can also achieve both uniformity and heterogeneity (selective component detection) by increasing the variety of sheets. We are investigating the migration patterns of compounds with basic structures on the quartz glass fiber sheet and are also working on developing methods to precisely control the measurement position on the sheet. Furthermore, we are investigating the compatibility of various biological samples (including serum, urine, pleural effusion, ascites, cerebrospinal fluid, bile, and pancreatic juice) with various quartz glass fiber sheets with different properties (including shape, size, thickness, and fiber density), including the optimal sample volume and the optimal time from instillation to measurement. We have also begun the basic design of a microdevice for measurement. Despite the limitations to be resolved, the QSM has potential for use in screening for diverse diseases, including cancer, metabolic diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, congenital disorders, and infectious diseases. Compared to other materials used for Raman spectroscopy, the QSM we developed does not emit Raman scattered light, and can crystallize and concentrate components, resulting in high scattered light intensity and low noise. Furthermore, it is an excellent substrate for Raman spectroscopy, with features such as ease of handling and extremely low cost, making it a cost-effective method. Furthermore, as no additional equipment beyond a Raman microscope is required, this simple and affordable novel technique can be implemented in setting with limited medical resources.

Figure 1.

Microdevices fabricated to record Raman spectra depending on the state of the sample, such as solid or aqueous solution. (a) Stainless-steel plate with depression for measuring the Raman spectrum of solid-state samples. (b) Needle method (NM; Japan Patent No. 7129732) for measuring the Raman spectrum of liquid samples. Raman spectra were recorded by irradiating a laser on a droplet of a sample prepared at the tip of a stainless-steel injection needle having an outer diameter of 1.20 mm. (c) Quartz sheet methods (QSM; Patent PCT pending; Application number: PCT/JP2024/038092) for the measurement of the Raman spectrum of liquid samples. (d) Raman spectra were recorded at six points at distances of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mm from the edge.

Figure 1.

Microdevices fabricated to record Raman spectra depending on the state of the sample, such as solid or aqueous solution. (a) Stainless-steel plate with depression for measuring the Raman spectrum of solid-state samples. (b) Needle method (NM; Japan Patent No. 7129732) for measuring the Raman spectrum of liquid samples. Raman spectra were recorded by irradiating a laser on a droplet of a sample prepared at the tip of a stainless-steel injection needle having an outer diameter of 1.20 mm. (c) Quartz sheet methods (QSM; Patent PCT pending; Application number: PCT/JP2024/038092) for the measurement of the Raman spectrum of liquid samples. (d) Raman spectra were recorded at six points at distances of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mm from the edge.

Figure 2.

Comparing the Raman spectra of crown glass, quartz glass slide, and quartz glass fiber sheet, peaks were observed in the crown glass and quartz glass, but in the Raman spectrum of the quartz glass fiber sheet, a slight peak due to the bending motion of Si-O-Si was observed around 495 cm-1, but no other clear peaks were observed.

Figure 2.

Comparing the Raman spectra of crown glass, quartz glass slide, and quartz glass fiber sheet, peaks were observed in the crown glass and quartz glass, but in the Raman spectrum of the quartz glass fiber sheet, a slight peak due to the bending motion of Si-O-Si was observed around 495 cm-1, but no other clear peaks were observed.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of the test sample in solid and aqueous solution (1 mol/dm3). Raman spectra of the aqueous test sample were recorded using two methods: needle method (NM) and quartz sheet method (QSM). (a) Raman spectra of sodium benzoate (C7H5NaO2, molecular weight: 144.1). Spectra of the solid state and the aqueous solution recorded by QSM had the same Raman shift, but the Raman spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by NM had different Raman shifts, e.g., no peak was observed at 1435 cm-1, whereas a peak was observed at 1393 cm-1 (red numbers). Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra recorded by QSM increased in a positive correlation with the number of drops. (b) Raman spectra of sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, molecular weight: 142.04). Spectra of the solid state and the spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by QSM had the same Raman shift, but the Raman spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by NM had different Raman shifts, e.g., no peak was observed at 994 cm-1, whereas a peak was observed at 980 cm-1 (red numbers). Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra recorded by QSM increased in a positive correlation with the number of drops.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of the test sample in solid and aqueous solution (1 mol/dm3). Raman spectra of the aqueous test sample were recorded using two methods: needle method (NM) and quartz sheet method (QSM). (a) Raman spectra of sodium benzoate (C7H5NaO2, molecular weight: 144.1). Spectra of the solid state and the aqueous solution recorded by QSM had the same Raman shift, but the Raman spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by NM had different Raman shifts, e.g., no peak was observed at 1435 cm-1, whereas a peak was observed at 1393 cm-1 (red numbers). Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra recorded by QSM increased in a positive correlation with the number of drops. (b) Raman spectra of sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, molecular weight: 142.04). Spectra of the solid state and the spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by QSM had the same Raman shift, but the Raman spectra of the aqueous solution recorded by NM had different Raman shifts, e.g., no peak was observed at 994 cm-1, whereas a peak was observed at 980 cm-1 (red numbers). Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra recorded by QSM increased in a positive correlation with the number of drops.

Figure 4.

Averaged Raman spectra of the serum. (a) The Raman spectra recorded by the QSM method had higher scattered light intensity than the spectra recorded by the NM method, and the scattered light intensity increased with the number of serum drops. (b) In QSM, the position showing the highest scattered light intensity shifted from the periphery to the center as the number of serum drops increased. (c) As the number of serum drops increased, the scattered light intensity increased, and the position showing the highest scattered light intensity tended to shift from the periphery toward the center. After five drops of serum were dropped, significant differences were observed for all combinations of positions, with p values less than 0.01. After 10 drops of serum were dropped, significant differences were observed for the 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm combinations, with p values less than 0.01 for all other combinations.

Figure 4.

Averaged Raman spectra of the serum. (a) The Raman spectra recorded by the QSM method had higher scattered light intensity than the spectra recorded by the NM method, and the scattered light intensity increased with the number of serum drops. (b) In QSM, the position showing the highest scattered light intensity shifted from the periphery to the center as the number of serum drops increased. (c) As the number of serum drops increased, the scattered light intensity increased, and the position showing the highest scattered light intensity tended to shift from the periphery toward the center. After five drops of serum were dropped, significant differences were observed for all combinations of positions, with p values less than 0.01. After 10 drops of serum were dropped, significant differences were observed for the 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm combinations, with p values less than 0.01 for all other combinations.

Figure 5.

Averaged Raman spectra of urine. (a) The scattered light intensity of the Raman spectrum obtained by QSM was higher than that obtained by NM, and increased with the number of drops of sample. However, there was no clear difference between the 5-drop and 10-drop samples except for the peak at 1000 cm-1. (b) When the scattered light intensity was examined according to the position on the sheet, the scattered light intensity was highest at 1.0 mm from the edge after 5 drops and at 2.0 mm (center) after 10 drops. (c) When the Raman scattered light intensity of the peak around 1000 cm-1 was compared, the scattered light intensity was similar between the 0.1 mm and 1.0 mm positions from the edge after 5 and 10 drops of urine. The scattered light intensity at 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm positions increased significantly after 10 drops.

Figure 5.

Averaged Raman spectra of urine. (a) The scattered light intensity of the Raman spectrum obtained by QSM was higher than that obtained by NM, and increased with the number of drops of sample. However, there was no clear difference between the 5-drop and 10-drop samples except for the peak at 1000 cm-1. (b) When the scattered light intensity was examined according to the position on the sheet, the scattered light intensity was highest at 1.0 mm from the edge after 5 drops and at 2.0 mm (center) after 10 drops. (c) When the Raman scattered light intensity of the peak around 1000 cm-1 was compared, the scattered light intensity was similar between the 0.1 mm and 1.0 mm positions from the edge after 5 and 10 drops of urine. The scattered light intensity at 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm positions increased significantly after 10 drops.

Figure 6.

Surface condition of a quartz glass fiber sheet after serum application. A 4 mm diameter, quartz glass fiber sheet (same as that used to record Raman spectra) was examined under a microscope after serum application. Serum (10 μL) was applied as five treatments: (a) no serum, (b) one drop, (c) three drops, (d) five drops, and (e) ten drops, with a 15-min interval between applications. A sheet without serum application served as control. A fine fibrous structure was observed on the surface of the sheet without serum application. A very fine granular structure was observed on the surface of the sheet with one serum application. A coarse granular structure was observed from the edge to the center on the surface of the sheet with three serum applications. In the center, a mixture of fine- and coarse-grained structures was observed. On the surface of the sheet with five drops of serum applied, a slightly uneven, rock-like structure was observed from the edge to the center. On the surface of the sheet with ten drops of serum applied, a relatively uniform, rock-like structure was observed from the edge to the center.

Figure 6.

Surface condition of a quartz glass fiber sheet after serum application. A 4 mm diameter, quartz glass fiber sheet (same as that used to record Raman spectra) was examined under a microscope after serum application. Serum (10 μL) was applied as five treatments: (a) no serum, (b) one drop, (c) three drops, (d) five drops, and (e) ten drops, with a 15-min interval between applications. A sheet without serum application served as control. A fine fibrous structure was observed on the surface of the sheet without serum application. A very fine granular structure was observed on the surface of the sheet with one serum application. A coarse granular structure was observed from the edge to the center on the surface of the sheet with three serum applications. In the center, a mixture of fine- and coarse-grained structures was observed. On the surface of the sheet with five drops of serum applied, a slightly uneven, rock-like structure was observed from the edge to the center. On the surface of the sheet with ten drops of serum applied, a relatively uniform, rock-like structure was observed from the edge to the center.

Figure 7.

Verification of spreading using quartz slides and serum. (a) Immediately after 10 μL of serum was dropped onto a glass slide. (b) Twenty-five minutes after 10 μL of serum was dropped onto a glass slide, the serum had almost completely dried. Visual observation revealed that the permeability of the dried serum decreased at the periphery, while the permeability from the center to the middle was relatively high. (c) An additional 20 μL of serum was dropped onto the dried serum (30 μL in total). After the serum dried, the permeability at the outermost periphery remained unchanged, but the thickness of the sample increased from the center to the outermost periphery, and the permeability decreased. (d) When the fifth drop of serum (50 μL in total) was observed in its dried state, it was possible to distinguish three regions based on their transparency characteristics: the outermost periphery, the center to the middle, and a region between the two. (e) An additional 50 μL of serum was dropped onto the dried serum (100 μL in total). The thickened area spread from the center to the periphery.

Figure 7.

Verification of spreading using quartz slides and serum. (a) Immediately after 10 μL of serum was dropped onto a glass slide. (b) Twenty-five minutes after 10 μL of serum was dropped onto a glass slide, the serum had almost completely dried. Visual observation revealed that the permeability of the dried serum decreased at the periphery, while the permeability from the center to the middle was relatively high. (c) An additional 20 μL of serum was dropped onto the dried serum (30 μL in total). After the serum dried, the permeability at the outermost periphery remained unchanged, but the thickness of the sample increased from the center to the outermost periphery, and the permeability decreased. (d) When the fifth drop of serum (50 μL in total) was observed in its dried state, it was possible to distinguish three regions based on their transparency characteristics: the outermost periphery, the center to the middle, and a region between the two. (e) An additional 50 μL of serum was dropped onto the dried serum (100 μL in total). The thickened area spread from the center to the periphery.

Table 1.

Summary of sample types, measurement methods, number of measurement locations, and number of recorded Raman spectra.

Table 1.

Summary of sample types, measurement methods, number of measurement locations, and number of recorded Raman spectra.

| Crown and quartz glass, and quartz glass fiber sheet |

|---|

| Sample |

Number of measurement points |

Number of total spectra |

| Crown glass |

5 |

25 |

| Quartz glass |

5 |

25 |

| Quartz glass fiber sheet |

5 |

25 |

| Sodium benzoate and sodium sulfate |

| Method |

Number of measurement points |

Number of total spectra |

| Solid state |

4 |

20 |

| NM |

1 (4 sets) |

20 |

| QSM, one drop |

1 |

20 |

| QSM, two drops |

1 |

20 |

| QSM, three drops |

1 |

20 |

| Serum and urine |

| Method |

Number of measurement points |

Number of total spectra |

| NM |

1 |

5 |

| QSM, one drop |

6 |

300 |

| QSM, five drops |

6 |

300 |

| QSM, ten drops |

6 |

300 |

Table 2.

Comparison of sample concentrations between NM and QSM.

Table 2.

Comparison of sample concentrations between NM and QSM.

| |

Sodium benzoate (molecular weight 144.1) |

Sodium sulfate (molecular weight 142.04) |

| |

Weight percent |

Weight/volume percent (g/100 mL) |

Weight percent |

Weight/volume percent (g/100 mL) |

| NM (1 mol/dm3) |

12.60% |

14.41% |

12.436% |

14.204% |

| QSM with one drop (1 mol/dm3, 10 μL) |

40.29% |

12.08% |

39.945% |

11.902% |

| QSM with two drops (1 mol/dm3, 20 μL) |

57.44% |

24.15% |

57.087% |

23.805% |

| QSM with three drops (1 mol/dm3, 30 μL) |

66.93% |

36.23% |

66.616% |

35.707% |

Table 3.

Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra of crown glass, quartz glass, quartz glass fiber sheet, sodium benzoate, and sodium sulfate.

Table 3.

Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra of crown glass, quartz glass, quartz glass fiber sheet, sodium benzoate, and sodium sulfate.

| Slide glass and quartz glass fiber sheet |

|---|

| Sample |

Raman shift (cm-1) |

Intensity (a.u.), mean (standard deviation) |

| Crown glass |

1095 |

1601.60 (394.48) |

| Quartz glass |

489 |

1788.22 (177.29) |

| Quartz glass fiber sheet |

501 |

217.94 (83.72) |

| Sodium benzoate |

| Method |

Intensity at 844 cm-1 (a.u.), mean (standard deviation) |

| Solid state |

27626.93 (341.00) |

| NM |

2330.58 (506.48) |

| QSM, one drop |

6841.43 (164.55) |

| QSM, two drops |

11434.46 (95.09) |

| QSM, three drops |

18355.08 (537.99) |

| Sodium sulfate |

| Method |

Intensity at 1101 cm-1 (a.u.), mean (standard deviation) |

| Solid state |

4551.01 (43.01) |

| NM |

351.62 (103.64) |

| QSM, one drop |

753.76 (47.22) |

| QSM, two drops |

1589.95 (46.51) |

| QSM, three drops |

2869.23 (47.31) |

Table 4.

Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra of serum and urine.

Table 4.

Scattered light intensity of the Raman spectra of serum and urine.

| Serum |

|---|

| Method |

Intensity at 1004 cm-1 (a.u.), mean (standard deviation) |

| NM |

231.88 (39.66) |

| QSM, one drop |

Overall |

638.15 (109.91) |

| 0.1 mm from edge |

790.37 (52.77) |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

753.95 (54.12) |

| 604.36 (48.05) |

| 1.0 mm from edge |

566.56 (40.62) |

| 1.5 mm from edge |

533.17 (62.15) |

| 2.0 mm from edge |

580.49 (41.86) |

| QSM, five drops |

Overall |

1236.82 (309.75) |

| |

0.1 mm from edge |

1794.66 (53.33) |

| |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

1288.61 (50.58) |

| 1117.50 (40.85) |

| |

1.0 mm from edge |

1390.06 (48.04) |

| |

1.5 mm from edge |

960.55 (38.50) |

| |

2.0 mm from edge |

869.57 (45.07) |

| QSM, ten drops |

Overall |

2417.79 (710.31) |

| 0.1 mm from edge |

1750.64 (53.99) |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

1720.49 (46.24) |

| 1965.77 (63.71) |

| 1.0 mm from edge |

2352.48 (61.82) |

| 1.5 mm from edge |

3569.55 (76.74) |

| 2.0 mm from edge |

3147.82 (94.89) |

| Urine |

| Method |

Intensity around 1000 cm-1 (a.u.), mean (standard deviation) |

| NM |

754.45 (121.16) |

| QSM, one drop |

Overall |

1357.38 (248.37) |

| 0.1 mm from edge |

1394.70 (51.53) |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

1362.09 (55.91) |

| 1595.20 (31.53) |

| 1.0 mm from edge |

1636.66 (58.85) |

| 1.5 mm from edge |

902.98 (73.73) |

| 2.0 mm from edge |

1252.66 (31.93) |

| QSM, five drops |

Overall |

6254.91 (707.35) |

| 0.1 mm from edge |

4858.71 (94.01) |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

6035.36 (94.12) |

| 6500.81 (128.92) |

| 1.0 mm from edge |

7054.76 (154.24) |

| 1.5 mm from edge |

6375.96 (67.03) |

| 2.0 mm from edge |

6703.86 (159.59) |

| QSM, ten drops |

Overall |

6871.53 (1766.02) |

| 0.1 mm from edge |

4687.70 (96.28) |

0.3 mm from edge

0.5 mm from edge |

6125.93 (86.88)) |

| 6043.01 (75.05) |

| 1.0 mm from edge |

7119.49 (113.11)) |

| 1.5 mm from edge |

8589.06 (146.10) |

| 2.0 mm from edge |

9538.70 (87.24) |