1. Introduction

Organizations undertaking enterprise-wide technology modernization frequently encounter a systems integration challenge: multiple transformation programs, each justified independently, create unforeseen interdependencies when executed concurrently. This challenge intensifies when programs operate under separate governance structures, compete for shared resources, and follow misaligned timelines. The result is often integration failures, cost overruns, and degraded operational effectiveness—outcomes documented repeatedly in government and industry modernization efforts [

1,

2].

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) currently faces an acute instance of this challenge. Three major cybersecurity modernization programs are underway simultaneously:

- 1.

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) Migration: Transitioning cryptographic infrastructure to quantum-resistant algorithms by 2030–2035, driven by the threat of future quantum computers breaking current encryption.

- 2.

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) Implementation: Deploying enterprise-wide continuous verification and least-privilege access controls by September 2027, replacing perimeter-based security models.

- 3.

AI Security Assurance: Establishing governance and technical controls for an expanding portfolio of AI-enabled capabilities, addressing adversarial manipulation and model integrity risks.

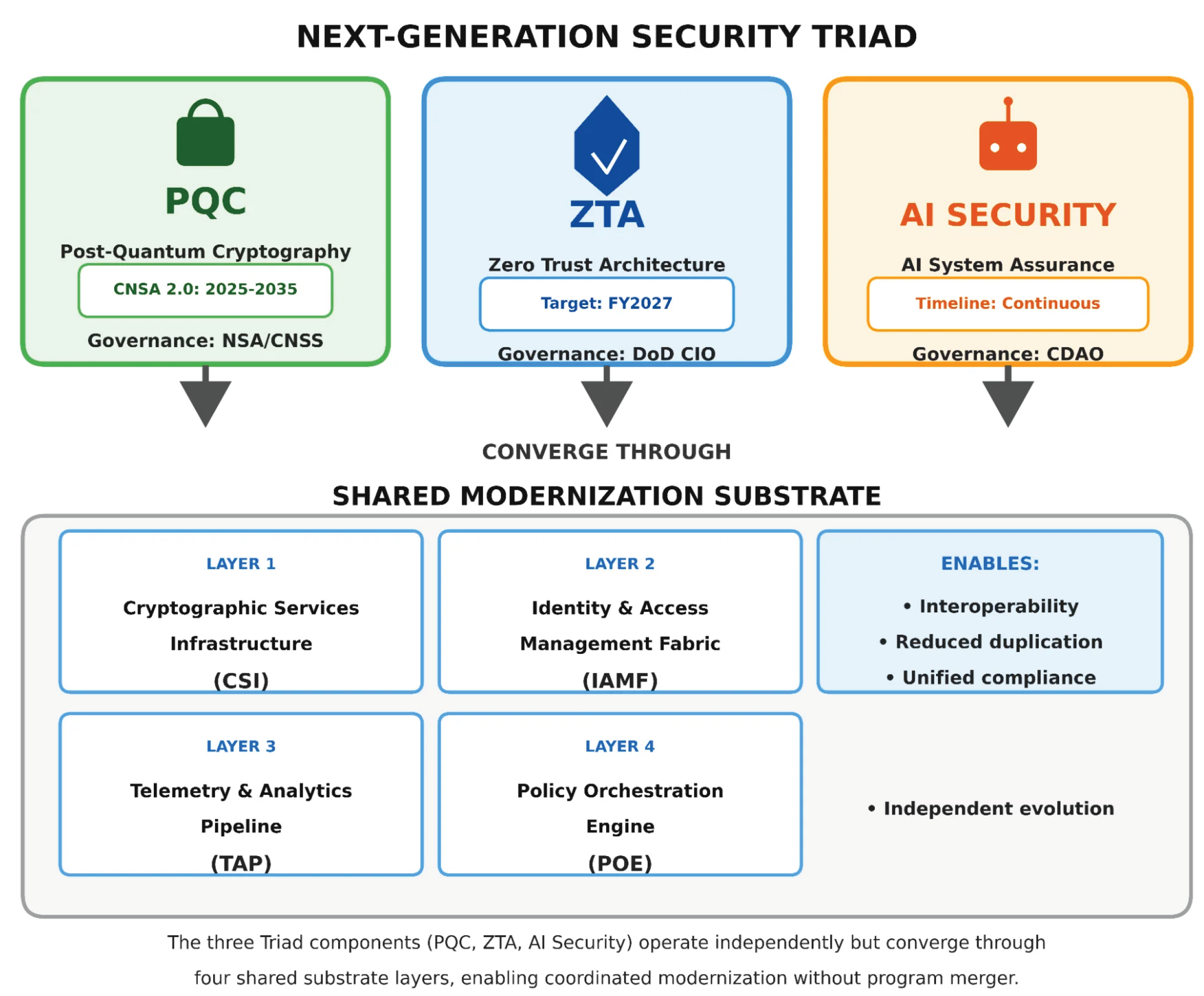

Together, these initiatives constitute what we term the Next-Generation Security Triad. Each program addresses a genuine and distinct threat: quantum computing threatens cryptographic foundations; sophisticated adversaries operating inside network perimeters undermine traditional trust models; adversarial machine learning attacks manipulate AI system outputs. The programs are individually necessary.

However, these programs are managed as independent initiatives with separate budget lines, governance committees, skill requirements, and compliance pathways. This fragmentation creates acute challenges for the personnel responsible for implementation. Chief Information Officers must reconcile competing modernization roadmaps. Program Management Offices struggle to sequence acquisitions when requirements create interdependencies. Authorizing Officials lack frameworks for assessing risk across all three domains simultaneously.

The conventional response—merge the programs—is impractical. Each program addresses fundamentally different threat models, requires distinct technical expertise, and operates under separate statutory authorities. Forced consolidation would likely impair all three efforts.

This paper proposes an alternative approach grounded in systems thinking: establish a shared modernization substrate—a common infrastructure foundation that all three programs build upon. Rather than forcing convergence at the program level, we enable integration at the infrastructure level. Each program retains its governance, timeline, and specialized focus while leveraging shared services that ensure interoperability, reduce duplication, and provide unified compliance visibility.

1.1. The Systems Integration Problem

The challenge addressed in this paper is fundamentally a systems integration problem rather than a purely technical one.

Table 1 summarizes the synchronization challenge across the three programs.

The programs exhibit three categories of interdependencies that isolated execution cannot address:

Technical Dependencies: ZTA’s continuous authentication relies on cryptographic primitives that PQC migration will replace. If the underlying signatures and key exchanges become vulnerable to quantum attack, the entire Zero Trust verification chain collapses. Conversely, AI-based behavioral analytics that inform ZTA trust decisions introduce new attack surfaces that neither the PQC nor ZTA programs are chartered to address.

Resource Dependencies: All three programs compete for the same enterprise infrastructure—identity services, key management systems, network monitoring capabilities, and policy enforcement points. Uncoordinated deployment creates conflicting requirements and duplicated investments.

Timeline Dependencies: The ZTA deadline (September 2027) precedes full PQC deployment (2030–2035). Systems achieving ZTA compliance with classical cryptography will require rework when PQC mandates take effect. Similarly, AI capabilities deployed without adversarial robustness controls will require retrofitting as AI security requirements mature.

1.2. Contributions

This paper makes four contributions to the systems integration literature:

- 1.

Cross-program dependency analysis: Systematic identification and categorization of dependencies among three concurrent cybersecurity modernization programs, based on evidence synthesis of 47 policy and standards sources (Supplementary S2).

- 2.

Shared substrate architecture: A four-layer infrastructure framework (Cryptographic Services, Identity Management, Analytics Pipeline, Policy Orchestration) that enables coordinated program execution while preserving governance independence.

- 3.

Convergence maturity model: A five-level assessment framework with operationalized indicators enabling repeatable measurement of organizational progress toward integrated modernization.

- 4.

Performance characterization: Quantitative analysis of integration overhead and efficiency gains, derived from synthesis of 12 benchmark studies (Supplementary S2).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides background on the three modernization programs and their interdependencies.

Section 3 describes the systematic evidence synthesis methodology.

Section 4 presents the shared substrate architecture.

Section 5 introduces the convergence maturity model.

Section 6 presents performance analysis.

Section 7 discusses implications and limitations.

Section 8 concludes.

2. Background: The Next-Generation Security Triad

2.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography Migration

The cryptographic algorithms protecting most digital communications today—RSA, elliptic curve cryptography, Diffie-Hellman key exchange—rely on mathematical problems that quantum computers could solve efficiently [

3]. While cryptographically relevant quantum computers do not yet exist, the “harvest now, decrypt later” threat model motivates near-term migration: adversaries capturing encrypted data today could decrypt it once quantum capability matures [

4].

The National Security Agency’s Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0) establishes phased transition milestones for national security systems (

Table 2) [

5,

6]. For federal civilian agencies, OMB Memorandum M-23-02 mandates cryptographic inventory completion and migration planning, establishing deadlines for identifying vulnerable systems and prioritizing transition [

22]; CISA provides complementary discovery and inventory guidance [

24]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) finalized three post-quantum standards in August 2024: ML-KEM for key encapsulation [

7], ML-DSA for digital signatures [

8], and SLH-DSA for stateless hash-based signatures [

9].

The systems integration challenge for PQC migration stems from the significantly larger key and signature sizes of post-quantum algorithms. Classical elliptic curve keys are 32 bytes; ML-KEM public keys are 1,184–1,568 bytes. Classical signatures are 64–256 bytes; ML-DSA signatures are 3,309–4,627 bytes. This 40–70x size increase affects every system that transmits cryptographic material—authentication protocols, certificate chains, secure channels—with cascading impacts on network bandwidth, latency, and storage.

2.2. Zero Trust Architecture Implementation

The DoD Zero Trust Strategy, released in November 2022, mandates enterprise-wide “Target Level” ZTA by September 30, 2027, with “Advanced Level” capabilities by 2032 [

10,

11]. This represents a fundamental shift from perimeter-based security (“trust but verify”) to continuous verification (“never trust, always verify”) [

12].

ZTA implementation encompasses seven pillars: User, Device, Network/Environment, Application and Workload, Data, Visibility and Analytics, and Automation and Orchestration. Full implementation requires completion of 152 activities across these pillars (91 Target-level activities by FY2027, plus 61 Advanced-level activities by FY2032) [

11].

The July 2025 Directive-Type Memorandum (DTM) 25-003 established the Chief Zero Trust Officer position, formalized governance through the DoD Zero Trust Executive Committee, and mandated Target-level ZTA implementation across all DoD information systems [

13]. The November 2025 Zero Trust for Operational Technology Activities and Outcomes guidance extended ZTA mandates to control systems and industrial environments, introducing additional constraints around deterministic latency requirements [

14].

ZTA’s integration challenges center on its dependencies. Continuous verification requires robust identity services—the DoD Public Key Infrastructure services millions of users across the enterprise [

15]. Trust scoring requires reliable behavioral analytics. Most critically, ZTA assumes “cryptographic agility”—the ability to update cryptographic algorithms without architectural redesign [

16]. If PQC migration and ZTA deployment proceed independently, systems may achieve ZTA compliance with cryptographic foundations that will require replacement within years.

2.3. AI Security and Assurance

AI systems introduce attack surfaces fundamentally different from traditional cybersecurity threats [

17]. NIST AI 100-2e2025, published March 2025, provides a taxonomy of adversarial machine learning attacks including [

18]:

Training-time attacks: Data poisoning, model poisoning, and backdoor insertion that compromise models before deployment.

Deployment-time attacks: Evasion attacks and adversarial examples that cause misclassification during inference.

Supply chain attacks: Compromised pre-trained models or malicious code in machine learning libraries.

The Chief Digital and AI Office (CDAO) released the Responsible AI Toolkit in 2024, operationalizing DoD’s AI Ethical Principles [

19]. DoD has initiated multiple generative AI pilot programs through the AI Rapid Capabilities Cell, reflecting significant investment in AI capability development [

2,

19].

The integration risk is acute. ZTA increasingly relies on AI-based behavioral analytics for trust scoring—User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA) engines that detect anomalous access patterns. An adversary using adversarial ML techniques could manipulate these trust scores, effectively bypassing access controls without triggering alarms. Neither the ZTA program (focused on access architecture) nor the PQC program (focused on cryptographic algorithms) is chartered to address this vulnerability.

2.4. Related Work

Existing enterprise architecture frameworks address technology modernization but not the specific challenge of concurrent security program synchronization. The DoD Architecture Framework (DoDAF) provides standardized methods for enterprise architecture but lacks constructs for representing cryptographic transition states or AI assurance pipelines [

20]. The Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF) predates both PQC mandates and AI governance requirements [

21].

Prior integration efforts have addressed pairwise combinations. The NSA Cybersecurity Reference Architecture incorporates Zero Trust principles and cryptographic services but does not address AI security. CISA’s Zero Trust Maturity Model includes cryptographic considerations but treats cryptographic agility as an assumed capability rather than a parallel modernization challenge [

23]. NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework provides comprehensive AI governance but operates independently from cryptographic and network security frameworks [

25].

The fundamental gap is the absence of a shared infrastructure layer that enables federated compliance across program boundaries. Current approaches assume either sequential modernization (one program completes before another begins), independent execution with post-hoc integration, or programmatic merger that conflicts with distinct governance authorities. The shared substrate framework addresses this gap.

3. Methodology: Systematic Evidence Synthesis

3.1. Research Design and Contribution Type

This study makes two distinct contributions requiring different methodological approaches:

- 1.

Systematic Evidence Synthesis: A structured review of policy documents, technical standards, and performance benchmarks to characterize the current state of DoD security modernization and identify cross-program dependencies (

Section 3–

Section 2).

- 2.

Prescriptive Architecture and Assessment Model: A proposed shared infrastructure framework (

Section 4) and maturity model (

Section 5) derived from synthesized requirements, with illustrative performance analysis (

Section 6).

The methodology follows PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines adapted for policy and standards synthesis [

27]. This approach is appropriate because the research questions concern

what is documented about modernization challenges and

what requirements emerge from authoritative sources—not experimental validation of a deployed system. The prescriptive components (substrate architecture, TCMM) are derived artifacts requiring future operational validation.

Reproducibility Commitment: All evidence extraction decisions, source coding, benchmark data transformations, and TCMM scoring calculations are fully documented in Supplementary Materials (S1_PRISMA_AuditTrail.csv, S2_Extraction_Dataset.csv, S3_TCMM_Rubric_and_TCMS_Inputs.csv, and supporting documentation in docs/) to enable independent verification and replication of the synthesis process.

3.2. Research Propositions

The research design addresses four propositions:

P1: Siloed modernization creates documented integration failures, cost growth, and compliance gaps.

P2: Cross-program dependencies exist among PQC, ZTA, and AI Security initiatives that isolated execution cannot address.

P3: Shared infrastructure approaches yield measurable efficiency gains over independent program execution.

P4: Published performance benchmarks can characterize integration requirements quantitatively.

3.3. Search Strategy

Searches were executed between January 15 and October 31, 2025 across five source classes using the following databases and repositories:

- 1.

Government Oversight: GAO.gov report database, DoD Inspector General FOIA reading room (2020–2025)

- 2.

Standards Bodies: NIST CSRC publications, NSA Cybersecurity Guidance repository, IETF Datatracker (2020–2025)

- 3.

DoD Policy: DoD CIO website (dodcio.defense.gov), CDAO public releases (2020–2025)

- 4.

Congressional Analysis: Congressional Research Service reports accessed via official Congressional distribution and archived committee documentation (2021–2025)

- 5.

Performance Benchmarks: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, IACR ePrint Archive (2020–2025)

The primary search string for academic databases was: ("post-quantum" OR "PQC" OR "quantum-resistant") AND ("zero trust" OR "ZTA") AND ("performance" OR "latency" OR "benchmark"). For policy sources, targeted searches used program-specific terms (e.g., “CNSA 2.0,” “DTM 25-003,” “DoD Zero Trust Strategy”).

3.4. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Published 2020–2025; (2) Addresses PQC, ZTA, or AI security in enterprise/government context; (3) Contains quantitative metrics, normative requirements, or documented implementation outcomes; (4) Available in English.

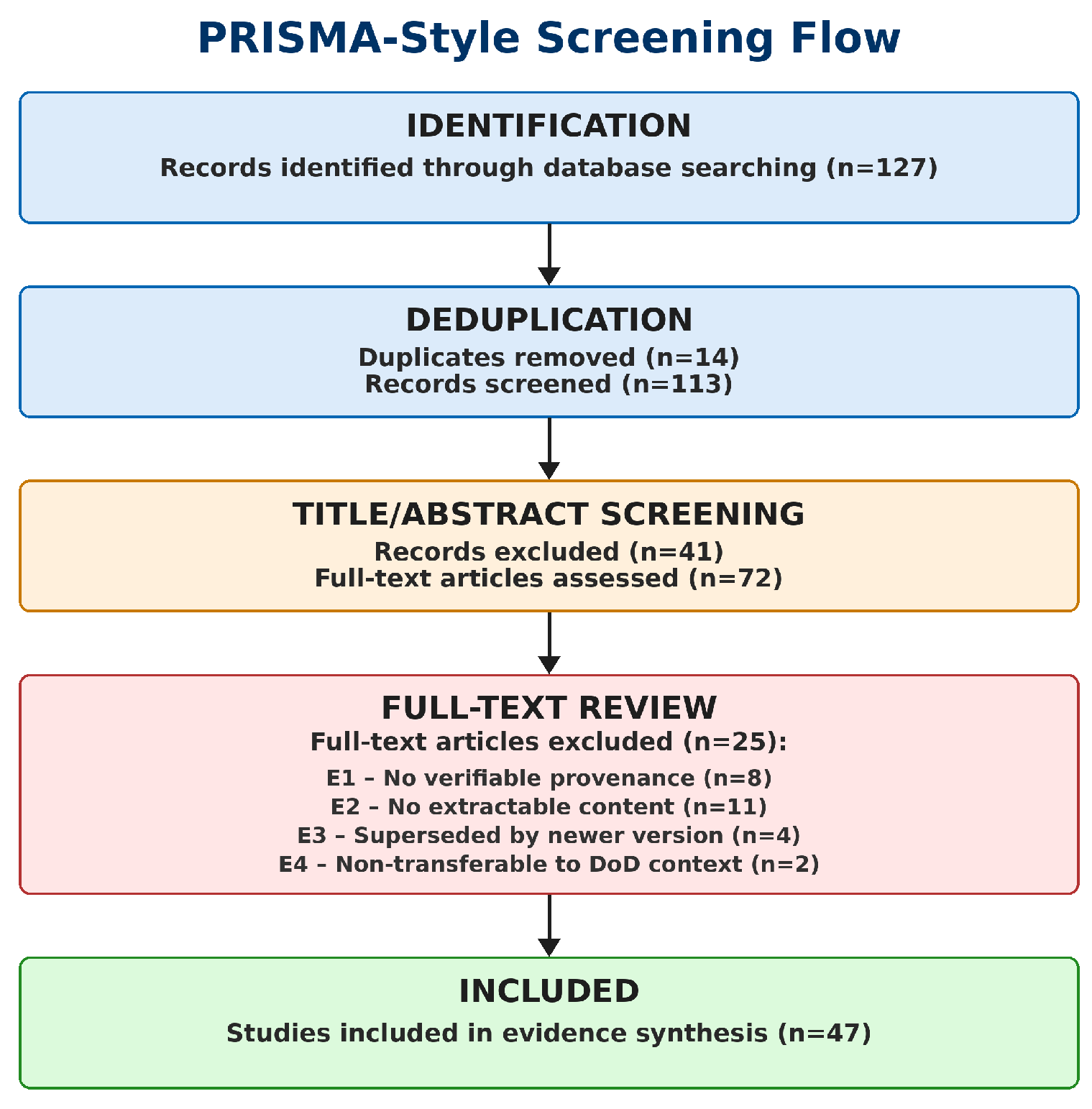

Exclusion criteria: (E1) No verifiable provenance (n=8); (E2) No extractable quantitative or normative content (n=11); (E3) Superseded by newer version (n=4); (E4) Non-transferable to DoD context (n=2).

3.5. Screening and Selection

Initial identification yielded 127 potentially relevant records. After deduplication (14 removed) and screening against eligibility criteria, 72 documents underwent full-text review. The final corpus comprised 59 included sources: 47 policy/standards documents plus 12 performance benchmarks (

Figure 1). The complete extraction dataset with all 59 sources is provided in Supplementary Materials (S2_Extraction_Dataset.csv).

3.6. Data Extraction and Coding

Each source was coded using a structured extraction template with the following fields: (1) Source identifier and citation; (2) Source type (policy/standard/benchmark/guidance); (3) Confidence tier (A/B/C); (4) Domain relevance (PQC/ZTA/AI Security/Cross-cutting); (5) Claim supported (mapped to propositions P1–P4); (6) Extracted metrics with units, experimental conditions, and context; (7) Limitations noted by original authors.

3.7. Quality Appraisal

Sources were classified into three confidence tiers based on methodological rigor and authority (

Table 3):

4. The Shared Modernization Substrate

4.1. Design Principles

The substrate architecture is grounded in three systems design principles:

Separation of Concerns: Each Triad program (PQC, ZTA, AI Security) retains its governance, timeline, budget authority, and specialized focus. The substrate provides shared infrastructure services rather than program integration.

Interface Standardization: Programs interact with the substrate through well-defined service interfaces, enabling independent evolution while ensuring interoperability.

Capability Composability: Substrate services can be consumed independently or in combination, allowing incremental adoption aligned with each program’s maturity.

4.2. Four-Layer Architecture

The shared substrate comprises four infrastructure layers that collectively enable program integration while preserving independence (

Figure 2).

4.2.1. Layer 1: Cryptographic Services Infrastructure (CSI)

The CSI layer provides enterprise-wide cryptographic services that decouple applications from specific algorithms. Rather than applications invoking cryptographic libraries directly, they request services from the CSI abstraction layer.

Key Capabilities:

Algorithm Abstraction: Applications request “secure key exchange” or “digital signature” without specifying algorithms. CSI selects appropriate algorithms based on policy and context.

Hybrid Mode Management: Per NSA CNSA 2.0 transition guidance [

6], systems will operate in hybrid mode during the PQC transition period (approximately 2025–2033 for software applications). CSI manages this complexity transparently. Per IETF hybrid key exchange specifications [

28,

29], the input keying material (IKM) is constructed by concatenating both the classical (e.g., ECDH) and post-quantum (e.g., ML-KEM) shared secrets; this combined IKM is then processed through the TLS 1.3 key schedule [

30] via HKDF. Backward compatibility is achieved through TLS supported_groups negotiation: endpoints advertise both classical-only groups (e.g., x25519) and hybrid groups (e.g., X25519MLKEM768 [

37]); the CSI layer manages group selection based on endpoint capabilities and policy requirements, enabling graceful coexistence of legacy and PQC-capable clients without protocol modification.

Key Lifecycle Services: Centralized management for cryptographic keys, handling the larger PQC key sizes and coordinating rotation with ZTA session policies.

Compliance Enforcement: Policy-based enforcement of minimum algorithm requirements, preventing downgrade attacks and ensuring CNSA 2.0 compliance.

Operational Technology (OT) Profiles: The November 2025 DoD Zero Trust for Operational Technology guidance [

14] introduces a critical bifurcation of OT environments into the

Operational Layer (supervisory systems, HMIs, historians) and the

Process Control Layer (PLCs, RTUs, actuators). This bifurcation has profound implications for CSI design:

Operational Layer Profile: Supervisory systems can tolerate PQC latencies of 100–300ms, as human-machine interactions operate on timescales of seconds. Full ML-KEM handshakes are acceptable, and the standard hybrid mode applies.

Process Control Layer Profile: Industrial control loops often execute on cycles of 10–20ms. PQC handshake latencies of 300ms+ would cause timing violations leading to physical system faults—missed control deadlines, oscillatory behavior, or safety system trips. For these environments, CSI must support alternative approaches: lightweight PQC candidates (when standardized), pre-shared key (PSK) modes with PQC-protected key distribution, or session resumption mechanisms that amortize handshake costs across multiple control cycles.

This OT bifurcation is not merely a performance optimization—it is a safety requirement. The CSI layer must maintain distinct cryptographic profiles and automatically select appropriate modes based on endpoint classification, preventing well-intentioned security upgrades from causing operational disruptions.

Integration Value: Without CSI, each application team must independently implement PQC migration, hybrid mode logic, algorithm selection, and OT-specific accommodations—multiplying effort and creating inconsistent security postures. CSI provides a single point of cryptographic policy enforcement that all three Triad programs can rely upon.

4.2.2. Layer 2: Identity and Access Management Fabric (IAMF)

The IAMF layer provides unified identity services for both human users and non-person entities (applications, AI models, IoT devices).

Key Capabilities:

Unified Identity Repository: Consolidated identity store supporting DoD’s millions of PKI users plus machine identities for AI models and autonomous systems.

PQC-Ready Credentials: Identity assertions cryptographically bound using post-quantum signatures, preventing “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks against long-lived credentials.

Trust Score Integration: Identity trust scores incorporate behavioral assessments from the TAP layer, enabling risk-adaptive authentication.

Federated Authentication: Support for cross-domain and coalition partner authentication with consistent security guarantees.

Integration Value: ZTA’s continuous verification depends on identity infrastructure. AI systems require identity for model provenance and API authentication. PQC migration affects all credential formats. IAMF ensures these requirements are addressed coherently rather than through conflicting program-specific implementations.

4.2.3. Layer 3: Telemetry and Analytics Pipeline (TAP)

The TAP layer provides unified security telemetry collection and analysis, including assurance controls for AI-based analytics.

Key Capabilities:

Unified Log Aggregation: Collection and normalization of security telemetry across enterprise and tactical environments.

Behavioral Analytics: ML-based anomaly detection providing trust scoring inputs to ZTA, with adversarial robustness controls.

Adversarial Input Detection: Validation layer that detects attempts to manipulate trust scores through crafted inputs.

Model Integrity Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of deployed ML models for output drift indicating compromise.

Adversarial AI Threat Integration: The TAP layer must address the specific attack taxonomy defined in NIST AI 100-2e2025 [

18] as it applies to ZTA trust scoring. Three attack categories pose direct threats to Zero Trust’s “never trust, always verify” logic:

Evasion Attacks Against Trust Scoring: An adversary can craft behavioral patterns that mimic legitimate user activity, causing the UEBA (User and Entity Behavior Analytics) engine to assign low risk scores while the adversary exfiltrates data. This is not merely a “risk”—it is a functional bypass of ZTA access controls. The adversary gains access not by compromising credentials but by manipulating the trust algorithm itself. TAP addresses this through ensemble scoring (multiple independent models), temporal consistency checks (sudden behavioral changes trigger alerts regardless of absolute score), and adversarial input validation that detects statistically anomalous feature distributions.

Model Poisoning in Federated Environments: In distributed DoD environments where behavioral models may be trained on data from multiple enclaves, an adversary controlling one enclave could inject poisoned training data that creates backdoors in the global model. TAP implements contribution validation—statistical tests that identify anomalous gradient updates before they are incorporated into federated model aggregation.

Model Extraction and Inversion: If adversaries can query the trust scoring API repeatedly, they may reconstruct the model’s decision boundaries (extraction) or infer sensitive information about training data (inversion). TAP implements rate limiting, query auditing, and differential privacy mechanisms that bound information leakage while preserving model utility.

The TAP layer thus serves as an “input validator” and “integrity monitor” for all AI models used in security decisions. Without this architectural layer, the integration of AI into ZTA creates the paradox of an intelligent security system that can be intelligently subverted.

Integration Value: ZTA trust scoring increasingly relies on AI-based analytics. Without TAP’s adversarial robustness controls, these analytics become attack vectors—adversaries can manipulate trust scores to bypass access controls. TAP ensures that AI integration enhances rather than undermines ZTA security.

4.2.4. Layer 4: Policy Orchestration Engine (POE)

The POE layer implements the Zero Trust policy decision point, synthesizing inputs from all substrate layers to make access decisions and coordinate automated responses.

Key Capabilities:

Attribute-Based Access Control: Policy evaluation integrating identity attributes (from IAMF), cryptographic status (from CSI), and risk scores (from TAP).

Cross-Layer Automation: Coordinated response across substrate layers. When TAP detects an anomaly, POE can trigger IAMF credential revocation and CSI session rekeying simultaneously.

Compliance Mapping: Automated mapping of policy decisions to compliance requirements across PQC (CNSA 2.0), ZTA (DTM 25-003), and AI Security (NIST AI RMF) frameworks.

Policy Distribution: Cryptographically authenticated distribution of policy updates to enforcement points.

Integration Value: POE transforms the three Triad programs from competing initiatives into coordinated capabilities. Access decisions consider cryptographic compliance, identity assurance, and behavioral risk together. Incident response orchestrates across all domains rather than requiring manual coordination between siloed teams.

4.3. Cross-Program Integration Points

Table 4 summarizes how the substrate layers create integration points where Triad programs converge.

5. Triad Convergence Maturity Model

To provide organizations with a measurable path toward integrated modernization, we introduce a five-level Triad Convergence Maturity Model (TCMM). The TCMM defines maturity levels and their associated indicators; the Triad Convergence Maturity Score (TCMS) provides the quantitative scoring formula for assessment. Each level includes operationalized indicators and assessment criteria supporting repeatable scoring.

Scope and Intent: The TCMM is a descriptive assessment framework designed to characterize an organization’s current integration state and identify capability gaps. It is not a predictive model—higher TCMS scores indicate greater integration maturity but do not guarantee better security outcomes or lower costs. The framework enables structured self-assessment and progress tracking; predictive validity would require longitudinal validation beyond this initial development.

5.1. Maturity Levels

Table 5 presents the five maturity levels with measurable indicators.

5.2. Scoring Methodology

The Triad Convergence Maturity Score (TCMS) provides quantitative assessment. Let

,

, and

denote domain subscores (0–1 scale) computed as weighted averages of indicator scores within each domain. Let

denote the cross-domain integration subscore. The composite TCMS is:

where

controls the relative weight of domain-specific capabilities versus cross-domain integration. The default weighting uses

, ensuring that organizations cannot achieve high maturity through domain excellence alone—cross-domain integration is structurally required. TCMS values map to levels: Level 0 (<0.20), Level 1 (0.20–0.39), Level 2 (0.40–0.59), Level 3 (0.60–0.79), Level 4 (≥0.80).

Weighting Sensitivity:

Table 6 presents TCMS scores and resulting maturity levels across the sensitivity range

.

Cases A and C demonstrate level stability across all tested weightings. Case B exhibits appropriate sensitivity near the Level 1/2 boundary (threshold 0.40), reflecting its strong ZTA domain score but weak cross-domain integration.

Missing Data Rules: When indicator evidence is unavailable: (1) If <50% of indicators within a domain are scorable, the domain subscore is marked “insufficient evidence” and excluded from TCMS calculation; (2) If ≥50% of indicators are scorable, missing indicators are scored as 0 (conservative assumption); (3) Assessment requires documentary evidence (policy documents, architecture diagrams, audit reports, or attestations) for each scored indicator—self-reported status without documentation scores 0.

Evidence Requirements: Each indicator requires minimum Tier B evidence (authoritative guidance or technical documentation). Tier C sources alone are insufficient. For quantitative indicators (e.g., “≥50% crypto centralized”), assessors must document the measurement methodology and data source.

Assessor Guidance and Bias Control: Single-rater assessment from public documentation introduces potential bias. Mitigation measures include: (1) documenting evidence sources and scoring rationale for each indicator to enable independent verification; (2) defaulting to lower scores when evidence is ambiguous; (3) using consistent indicator definitions across all assessed cases. The complete operationalized rubric—including measurement methods, minimum evidence requirements per indicator, and indicator-level scoring with citations for each case study—is provided in Supplementary Materials (docs/TCMM_Rubric_Definitions.md).

5.3. Case Study Application

To demonstrate the framework’s ability to differentiate modernization contexts, we applied TCMS scoring to three publicly documented DoD modernization contexts using evidence from the synthesis corpus (

Table 7).

Case A: DISA Thunderdome [

31] represents DISA’s Zero Trust security initiative, which integrates identity management, software-defined networking, and security analytics. Evidence sources include DISA public briefings and the DoD Zero Trust Portfolio Management Office documentation.

Case B: DON Flank Speed [

32] represents the Department of the Navy’s enterprise cloud and collaboration environment. Evidence sources include Navy CIO public presentations and GAO assessments of Navy IT modernization [

2].

Case C: Legacy Enclave represents a composite profile of pre-modernization environments based on GAO high-risk assessments [

1] documenting fragmented IT management across DoD components.

The three cases yielded TCMS scores spanning the maturity spectrum, with 0.25+ gaps between adjacent cases exceeding the 0.20 level threshold width, demonstrating the framework’s ability to distinguish meaningfully different modernization states. Note that this preliminary application employed single-rater scoring; future validation should incorporate multi-rater assessment with inter-rater reliability measures.

6. Performance Analysis

This section presents performance characterizations derived from evidence synthesis. Enterprise latency values in

Table 8 are measured values drawn directly from peer-reviewed benchmark studies. Tactical environment values are

modeled estimates derived by applying packet-loss extrapolation to measured enterprise baselines; they should be interpreted as indicative projections, not measured operational data.

Table 10 presents qualitative characterizations synthesized from adversarial ML literature.

Table 11 presents a qualitative modeled scenario illustrating potential orchestration benefits based on industry incident response benchmarks.

6.1. PQC Integration Overhead

Synthesis of benchmark studies reveals significant performance implications for uncoordinated PQC deployment [

33,

34,

35,

36].

Table 8 presents authentication handshake latency across network conditions.

Table 8.

Authentication Latency: Classical vs. Post-Quantum Cryptography (synthesized from benchmark studies).a

Table 8.

Authentication Latency: Classical vs. Post-Quantum Cryptography (synthesized from benchmark studies).a

| Configuration |

Handshake Payload (bytes) |

Enterprise (ms) |

Tactical (5% loss) |

Overhead (Tactical) |

| Classical (ECDH + ECDSA) |

KEM: 32 + Sig: 64 |

25 |

120 |

baseline |

| PQC Level 3 (ML-KEM-768 + ML-DSA-65) |

KEM: 1,184 + Sig: 3,309 |

28 |

310 |

+158% |

| PQC Level 5 (ML-KEM-1024 + ML-DSA-87) |

KEM: 1,568 + Sig: 4,627 |

35 |

580 |

+383% |

| Hybrid (ECDH + ML-KEM-768) |

KEM: 1,216 + Sig: 3,309 |

30 |

340 |

+183% |

Sensitivity Analysis:

Table 9 presents tactical latency projections for ML-KEM-768 across parameter variations. The base case (310 ms) is the

measured value from [

34]; sensitivity rows are

model projections using the calibrated formula to explore parameter variations.

Table 9.

Tactical Latency Sensitivity Analysis: ML-KEM-768 Configuration.

Table 9.

Tactical Latency Sensitivity Analysis: ML-KEM-768 Configuration.

| Parameter |

Low |

Base |

High |

Range |

Notes |

| Base case (measured) |

|

p = 5%, measured |

– |

310 ms |

– |

– |

From [34] |

| Packet loss variation (model, k=16, MTU=1500) |

|

p = 1% |

158 ms |

– |

– |

– |

Near-enterprise (modeled) |

|

p = 10% |

– |

– |

504 ms |

158–504 ms |

Degraded tactical (modeled) |

| Conservative scenarios (model, k=40, p=5%) |

|

k = 40 (conservative) |

– |

– |

600 ms |

– |

Higher retransmission penalty |

|

k = 60 (pessimistic) |

– |

– |

840 ms |

310–840 ms |

Severe congestion |

| Combined projections (model) |

| Best (p=1%, k=16) |

158 ms |

– |

– |

– |

+32% vs Classical |

| Base (measured) |

– |

310 ms |

– |

– |

+158% vs Classical |

| Worst (p=10%, k=60) |

– |

– |

1,080 ms |

158–1,080 ms |

+800% vs Classical |

Key Finding: In the specific LAN/TLS 1.3 benchmark conditions of [

33,

34,

35], incremental enterprise PQC handshake latency is single-digit milliseconds (3–10 ms overhead). In tactical networks with packet loss, measured and extrapolated values indicate PQC latency increases of 158–383% due to fragmentation and retransmission—effects are dominated by payload size under loss, not by cryptographic computation. The enterprise baselines are drawn from TLS 1.3 handshake measurements in the cited benchmark studies; tactical values derive from measurements under 5% loss conditions. The large cryptographic payloads (up to 6KB for a complete handshake) span multiple network packets; loss of any fragment triggers full retransmission, which dominates latency under lossy conditions.

Scope caveat: Results may differ with other implementations, certificate chains, hardware, or handshake modes; these values represent specific benchmark conditions, not universal predictions.

Systems Implication: Without substrate-level coordination (CSI layer), ZTA deployments in tactical environments will fail latency requirements when PQC mandates take effect. The CSI layer enables adaptive algorithm selection, pre-shared key modes for constrained environments, and session resumption—optimizations that individual application teams cannot implement consistently.

6.1.1. Operational Technology Latency Constraints

The performance implications become critical when considering Operational Technology (OT) environments. The DoD Zero Trust for OT guidance [

14] distinguishes between the Operational Layer and the Process Control Layer, each with distinct latency tolerances:

Operational Layer (SCADA servers, historians, HMIs): These supervisory systems interact with human operators on timescales of seconds. Authentication latencies of 100–340ms (as shown in

Table 8 for tactical environments) are acceptable, as they represent a small fraction of typical human-machine interaction cycles.

-

Process Control Layer (PLCs, RTUs, actuators): Industrial control loops typically execute on cycles of 10–100ms, with safety-critical loops often requiring sub-20ms determinism [

14,

26]. A PQC handshake latency of 310–580ms would span 15–30 control cycles, causing:

- -

Missed control deadlines leading to open-loop operation

- -

Oscillatory behavior as controllers lose synchronization

- -

Safety system trips due to watchdog timeouts

- -

In extreme cases, physical damage to equipment or processes

This bifurcation has direct implications for the Shared Modernization Substrate. The CSI layer cannot apply uniform cryptographic policies across all environments. Instead, it must maintain environment-aware profiles:

- 1.

Enterprise Profile: Full ML-KEM + ML-DSA hybrid handshakes; latency budget 50–100ms.

- 2.

Tactical Profile: Hybrid handshakes with session resumption; latency budget 200–500ms.

- 3.

OT Operational Profile: Standard PQC with extended session validity; latency budget 100–300ms.

- 4.

OT Process Control Profile: PSK mode with PQC-protected key distribution; real-time latency budget <20ms for ongoing operations, with PQC overhead amortized to key establishment phases.

The Process Control Profile represents a necessary compromise: the control-plane communications use pre-shared keys (meeting real-time constraints), while the key distribution infrastructure uses full PQC (protecting against “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks on key material). This layered approach ensures quantum resistance for long-term secrets while preserving operational safety.

6.2. Adversarial Impact on Trust Scoring

Table 10 presents detection performance for behavioral analytics under adversarial attack, comparing standard implementations against hardened configurations [

17,

38].

Key Finding: Standard behavioral analytics can suffer substantial degradation under adversarial attack—the literature consistently reports significant detection capability reductions under sophisticated evasion techniques, with some controlled experiments demonstrating near-complete evasion. Adversarially hardened models incorporating defensive techniques (adversarial training, input validation, ensemble methods) demonstrate substantially better resilience across studies.

Systems Implication: ZTA programs deploying AI-based trust scoring without adversarial robustness controls create exploitable vulnerabilities. The TAP layer’s adversarial input detection and model integrity monitoring are not optional enhancements—they are structural necessities for ZTA security.

Table 10.

Behavioral Analytics Detection Under Adversarial Conditions (qualitative characterization from literature synthesis).b

Table 10.

Behavioral Analytics Detection Under Adversarial Conditions (qualitative characterization from literature synthesis).b

| Scenario |

Standard ML |

Hardened ML |

Hardening Impact |

| Baseline (benign traffic) |

High |

High |

Minimal |

| Lateral movement detection |

High |

High |

Minimal |

| Adversarial evasion (gradient-based) |

Degraded |

Maintained |

Substantial |

| Adversarial evasion (optimization) |

Severely degraded |

Maintained |

Substantial |

| Training data poisoning (5%) |

Moderately degraded |

Maintained |

Moderate |

| Training data poisoning (10%) |

Substantially degraded |

Moderately degraded |

Moderate |

6.3. Orchestration Efficiency

Table 11 compares incident response metrics for siloed versus substrate-orchestrated approaches, based on a decomposition model of response time components.

Response Time Decomposition Model: Industry incident response studies decompose total response time into sequential phases. We model siloed response time as:

Based on SANS IR Survey 2023 findings [

40], we estimate relative phase contributions for organizations with siloed security tools: telemetry collection (15%), cross-system correlation (25%), initial triage (15%), escalation to appropriate team (10%), cross-team coordination (25%), and containment action (10%). The substrate architecture affects specific phases:

TAP layer reduces through unified telemetry (estimated 80% reduction in correlation time)

POE layer eliminates and through automated orchestration (100% reduction)

Pre-authorized playbooks reduce (estimated 50% reduction)

Key Finding: The decomposition model suggests substrate-orchestrated response could reduce active response time by approximately 60% compared to siloed approaches. The largest gains come from eliminating cross-team coordination delays (35% of siloed response time) through POE’s automated orchestration. This estimate is model-derived and requires operational validation.

Systems Implication: The POE layer’s automated cross-domain response eliminates coordination delays. When the TAP layer detects an anomaly, POE can simultaneously trigger IAMF credential suspension and CSI session rekeying without manual escalation between program teams.

Table 11.

Incident Response: Siloed vs. Substrate-Orchestrated (modeled scenario).c

Table 11.

Incident Response: Siloed vs. Substrate-Orchestrated (modeled scenario).c

| Response Phase |

Siloed (%) |

Substrate (%) |

Reduction |

| Telemetry collection |

15% |

15% |

0% |

| Cross-system correlation |

25% |

5% |

80% |

| Initial triage |

15% |

15% |

0% |

| Escalation to team |

10% |

0% |

100% |

| Cross-team coordination |

25% |

0% |

100% |

| Containment action |

10% |

5% |

50% |

| Total (normalized) |

100% |

40% |

60% |

7. Discussion

7.1. Implications for Enterprise Architecture

The shared substrate framework offers several implications for organizations managing concurrent modernization programs:

Infrastructure-level integration preserves program independence: Organizations need not choose between siloed execution (with integration failures) and forced program merger (with governance conflicts). The substrate provides a middle path—shared infrastructure services that enable coordination while preserving program autonomy.

Cross-program dependencies require explicit architectural treatment: Dependencies among concurrent programs do not resolve through parallel execution. The PQC-ZTA-AI Security dependencies identified in this study would create failures regardless of individual program success. Architectural mechanisms (the four substrate layers) are necessary to address dependencies that program governance cannot.

Maturity assessment enables incremental progress: The five-level TCMM provides organizations with actionable intermediate targets. An organization at Level 0 (Fragmented) can progress to Level 1 (Aware) through dependency analysis and roadmap alignment, without requiring full infrastructure deployment.

7.2. Limitations

Several limitations constrain interpretation of these findings:

Synthesis rather than experimentation: Performance characterizations derive from synthesis of published benchmarks, not direct experimentation in operational environments. While benchmark normalization and projection follow established practices, operational validation is required.

Benchmark heterogeneity (threat to validity): The performance values in

Table 8 and

Table 10 synthesize results from studies conducted across different hardware platforms, software stacks, network configurations, and tuning parameters. These results are not directly comparable in a strict experimental sense. Normalized values presented are approximate central tendencies; confidence intervals are not implied unless explicitly computed in the source studies. Tactical network estimates (158–383% overhead) are derived from extrapolation models applied to enterprise measurements—they represent plausible projections under stated assumptions (5% packet loss, 1500-byte MTU), not measured operational values. Readers should interpret these figures as indicative of relative magnitude rather than precise operational predictions.

DoD-specific context: The framework addresses DoD modernization programs with specific governance structures, timelines, and compliance requirements. Generalization to other organizational contexts requires adaptation.

Evolving standards: PQC standards, ZTA guidance, and AI security frameworks continue to evolve. The substrate architecture accommodates this evolution through its abstraction layers, but specific interface definitions will require updates as standards mature.

Implementation complexity: The substrate architecture introduces infrastructure that must itself be developed, deployed, and maintained. Organizations must weigh integration benefits against substrate implementation costs.

Single-rater scoring: The TCMM case study application employed single-rater scoring based on publicly available documentation. Formal validation of the maturity model requires multi-rater assessment with inter-rater reliability statistics to establish measurement validity.

TCMM scope and validation status: The Triad Convergence Maturity Model is presented as a descriptive assessment framework for characterizing current organizational state, not as a predictive model for forecasting modernization outcomes. The illustrative case study demonstrates the framework’s ability to differentiate maturity levels but does not establish predictive validity (i.e., that higher TCMS scores correlate with better security outcomes or lower integration costs). Establishing predictive validity would require longitudinal studies tracking organizations through modernization programs, which is beyond the scope of this initial framework development. Users should apply TCMM for structured assessment and gap identification, not for predicting program success probabilities.

7.3. Future Work

Priority areas for future research include:

- 1.

Pilot implementation with a DoD pathfinder organization to validate performance projections under operational conditions.

- 2.

Extension of the maturity model to address coalition partner interoperability and cross-organizational integration.

- 3.

Development of training curricula aligned with DoD Cyber Workforce Framework competencies.

- 4.

Investigation of substrate applicability to commercial enterprise security modernization.

- 5.

Multi-rater validation of the TCMM scoring methodology with inter-rater reliability assessment (e.g., Cohen’s ) to establish measurement validity.

8. Conclusion

Large organizations executing concurrent security modernization programs face a systems integration challenge: programs justified independently create unforeseen interdependencies that isolated execution cannot address. This paper examined the DoD’s simultaneous implementation of post-quantum cryptography migration, Zero Trust Architecture deployment, and AI security assurance—three programs with distinct governance, timelines, and technical requirements that nonetheless share critical dependencies.

Through systematic evidence synthesis of 59 sources (47 policy/standards documents and 12 benchmarks; full corpus in Supplementary S2), we identified cross-program dependencies in three categories: technical dependencies (ZTA cryptographic foundations, AI-based trust scoring), resource dependencies (shared infrastructure and personnel), and timeline dependencies (ZTA deadlines preceding PQC completion).

The shared modernization substrate provides an architectural response to these dependencies. Four infrastructure layers—Cryptographic Services (CSI), Identity and Access Management (IAMF), Telemetry and Analytics (TAP), and Policy Orchestration (POE)—enable coordinated program execution while preserving governance independence. The substrate transforms fragmented modernization into synchronized capability delivery.

The Triad Convergence Maturity Model provides organizations with measurable progress indicators, enabling incremental advancement from fragmented execution (Level 0) through awareness (Level 1), alignment (Level 2), integration (Level 3), to adaptive operation (Level 4). Case study application demonstrated the framework’s ability to differentiate meaningfully across three DoD modernization contexts.

Performance analysis, synthesizing published benchmarks and scenario modeling, indicates that uncoordinated execution carries significant costs: modest enterprise PQC overhead (measured) but projected 158–383% latency overhead in tactical networks under packet-loss conditions (modeled); substantial detection degradation for trust scoring without TAP adversarial controls (synthesized from literature); and extended incident response windows without POE orchestration (scenario-modeled). These costs are potentially avoidable through substrate-enabled coordination.

The framework offers practical guidance for CIOs, program managers, and enterprise architects facing concurrent technology transitions. The core insight is broadly applicable: when multiple transformation programs share dependencies, infrastructure-level integration enables coordination that program-level governance cannot achieve. The shared substrate transforms competing programs into complementary capabilities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, investigation, writing: R.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study follows a systematic evidence synthesis approach to develop and parameterize the proposed PQC–ZTA–AI triad convergence architecture and maturity model. To support reproducibility, we provide as Supplementary Materials the complete bibliographic corpus, screening decisions, extracted quantitative and qualitative fields, and the computation steps used to derive all synthesized tables and the Triad Convergence Maturity Score (TCMS). Specifically:

Search Strategy and Screening Records (data/S1_PRISMA_AuditTrail.csv). Exact search strings, databases/sources, date ranges, and inclusion/exclusion criteria consistent with the PRISMA flow in

Section 3. For each screened record: screening stage outcomes, exclusion reason codes, and final inclusion status. Search strategy details documented in docs/PRISMA_Search_Strings.md.

Evidence Extraction Dataset (data/S2_Extraction_Dataset.csv). Machine-readable dataset containing all included sources (Tier A/B/C) and extracted fields (algorithm parameters, protocol context, performance metrics, environment descriptors). Each quantitative field includes units and measurement context. Schema and controlled vocabularies documented in docs/Codebook_S2_Extraction_Dataset.md.

Maturity Model Scoring Inputs (data/S3_TCMM_Rubric_and_TCMS_Inputs.csv). Per-dimension raw scores for each case, missing-data handling flags, computed TCMS outputs, and sensitivity parameters. Rubric definitions and scoring rules documented in docs/TCMM_Rubric_Definitions.md.

Analytic Workflow (code/reproduce_tables.py). Self-contained Python script that ingests the extraction dataset and reproduces Tables 6–10. Dependencies listed in code/requirements.txt. All model parameters and assumptions documented in docs/Assumptions_and_Model_Parameters.md.

The dataset preserves original reporting context and includes normalization/compatibility flags for subset

analyses. All modeled estimates are explicitly labeled with corresponding parameter values. Availability: Supplementary Materials are provided with this manuscript as a compressed archive (supplementary_materials.zip).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More. GAO-25-108125, 2025. Available: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-108125 (Accessed: January 4, 2026.). January.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Information Technology: DOD Annual Assessment. GAO-25-107649, March 2025. Available: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-107649 (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Chen, L.; et al. Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography. NIST IR 8105, 2016. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/ir/8105/final. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M.; Piani, M. Quantum Threat Timeline Report 2024. Global Risk Institute, 2024. Available: https://globalriskinstitute.org/publication/2024-quantum-threat-timeline-report/ (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- National Security Agency. Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0). NSA Cybersecurity Advisory, 2022. Available: https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/07/2003071834/-1/-1/0/CSA_CNSA_2.0_ALGORITHMS_.PDF (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- National Security Agency. CNSA 2.0 and Quantum Computing FAQ, Version 2.1. 2024. Available: https://media.defense.gov/2024/Aug/20/2003529287/-1/-1/0/CTR_CNSA2.0_FAQ.PDF (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard. FIPS 203, August 2024. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/203/final. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard. FIPS 204, August 2024. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/204/final. August. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard. FIPS 205, August 2024. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/205/final. [CrossRef]

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Zero Trust Strategy. November 2022. Available: https://dodcio.defense.gov/Portals/0/Documents/Library/DoD-ZTStrategy.pdf (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Zero Trust Capability Execution Roadmap, Version 1.1. Washington, DC: DoD CIO, December 2024. Available: https://dodcio.defense.gov/Portals/0/Documents/Library/DoD-ZTRoadmap.pdf (Enumerates 91 Target-level and 61 Advanced-level activities totaling 152 ZTA implementation activities.) (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; Mitchell, S.; Connelly, S. Zero Trust Architecture. NIST SP 800-207, 2020. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/207/final. [CrossRef]

- Department of Defense. Directive-Type Memorandum (DTM) 25-003: Implementing the DoD Zero Trust Strategy. Washington, DC: Washington Headquarters Services, July 2025. Available: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dtm/DTM-25-003.PDF (Accessed: January 4, 2026.) [Establishes Component Chief Zero Trust Officer (CZTO) position and Zero Trust Portfolio Management Office (ZT PfMO) governance structure.].

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. Zero Trust for Operational Technology Activities and Outcomes. Washington, DC: DoD CIO, November 2025. Available: https://dodcio.defense.gov/Portals/0/Documents/Library/ZT-OT-Activities-Outcomes.pdf (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Department of Defense Chief Information Officer. DoD Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) Strategy. 2020. Available: https://dodcio.defense.gov/Portals/0/Documents/Cyber/DoD_Enterprise_ICAM_Strategy.pdf (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards. NIST IR 8547, November 2024.

- Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Wild Patterns: Ten Years After the Rise of Adversarial Machine Learning. Pattern Recognition 2018, 84, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, A.; Oprea, A.; Fordyce, A. Adversarial Machine Learning: A Taxonomy and Terminology of Attacks and Mitigations. NIST AI 100-2e2025, National Institute of Standards and Technology, March 2025. Available: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.AI.100-2e2025 (Accessed: January 4, 2026.). March. [CrossRef]

- Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office. Responsible AI Strategy and Implementation Pathway. 2024. Available: https://www.ai.mil/docs/RAI_Strategy_Implementation_Pathway_2024.pdf (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Department of Defense. DoD Architecture Framework (DoDAF), Version 2.02. 2010.

- Office of Management and Budget. Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework, Version 2. 2013.

- Office of Management and Budget. Memorandum M-23-02: Migrating to Post-Quantum Cryptography. November 2022. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/M-23-02-M-Memo-on-Migrating-to-Post-Quantum-Cryptography.pdf (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Zero Trust Maturity Model, Version 2.0. April 2023. Available: https://www.cisa.gov/zero-trust-maturity-model (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Post-Quantum Cryptography Initiative. 2024. Available: https://www.cisa.gov/quantum (Accessed: January 4, 2026.) [Includes cryptographic inventory guidance and migration planning resources.].

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. AI Risk Management Framework 1.0. NIST AI 100-1, 2023.

- Stouffer, K.; Pillitteri, V.; Lightman, S.; Abrams, M.; Hahn, A. Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security. NIST SP 800-82 Revision 3, September 2023. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/82/r3/final. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebila, D.; Fluhrer, S.; Gueron, S. Hybrid Key Exchange in TLS 1.3. IETF Internet-Draft (work in progress), draft-ietf-tls-hybrid-design-12, January 2025. Available: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-tls-hybrid-design/ (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Schwabe, P.; Stebila, D.; Wiggers, T. ML-KEM for TLS 1.3. IETF Internet-Draft (work in progress), draft-ietf-tls-mlkem-05, November 2025. Available: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-tls-mlkem/ (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Rescorla, E. The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.3. RFC 8446, August 2018. Available: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8446. [CrossRef]

- Defense Information Systems Agency. Thunderdome: DISA’s Zero Trust Security Initiative. 2024. Available: https://www.disa.mil/About/Strategic-Initiatives/Thunderdome (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Department of the Navy Chief Information Officer. Flank Speed: DON Enterprise Cloud Environment. Washington, DC: DON CIO, 2023. Available: https://www.doncio.navy.mil/FlankSpeed.aspx (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Paquin, C.; Stebila, D.; Tamvada, G. Benchmarking Post-Quantum Cryptography in TLS. PQCrypto 2020, pp. 72–91. [CrossRef]

- Sikeridis, D.; Kampanakis, P.; Devetsikiotis, M. Post-Quantum Authentication in TLS 1.3: A Performance Study. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, February 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kampanakis, P.; Sikeridis, D.; Devetsikiotis, M. Post-Quantum TLS Performance. IACR ePrint 2020/071. Available: https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/071 (Accessed: January 4, 2026.).

- Stebila, D.; Mosca, M. Post-Quantum Key Exchange for the Internet and the Open Quantum Safe Project. SAC 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, K.; Kampanakis, P.; Westerbaan, B.; Stebila, D. X25519Kyber768Draft00 Hybrid Post-Quantum Key Agreement. IETF Internet-Draft (work in progress), draft-tls-westerbaan-xyber768d00-03, March 2024. Available: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-tls-westerbaan-xyber768d00/ (Accessed: January 4, 2026.) Note: This individual draft documents early hybrid deployment experience; production implementations should reference current WG drafts [25,26].

- Apruzzese, G.; Laskov, P.; Tastemirova, A. SoK: The Impact of Unlabelled Data in Cyberthreat Detection. IEEE EuroS&P 2023.

- IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024; IBM Corporation, July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SANS Institute. SANS 2023 Incident Response Survey; SANS Institute, 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).