Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are two of the most common neurodevelopmental conditions, each affecting roughly 1–2 % of children worldwide and often persisting into adulthood [

1]. Although their headline symptoms differ—social-communication difficulties and restricted interests in ASD; inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity in ADHD—the two syndromes turn up together more often than not. Population studies put the rate of comorbidity above 50 %, hinting at a substantial overlap in the biology that drives them [

2]. Dissecting what the disorders share and what sets them apart is therefore essential for crafting targeted treatments.

Genomic advances have moved that dissection from speculation to data. Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) reveal that risk for both ASD and ADHD is highly polygenic, with scores of common variants clustering in neurodevelopmental pathways [

3,

4]. Two mechanisms keep appearing. First, glitches in glutamatergic signalling—the backbone of excitatory transmission and synaptic plasticity—are thought to upset the excitation–inhibition balance in ASD [

5,

6]. Second, problems with synaptic pruning—the microglia-guided trimming of excess connections during childhood and adolescence—have been invoked for both conditions, though possibly in opposite directions: too much pruning may leave social circuits under-connected in ASD [

7,

8], whereas too little pruning may keep ADHD networks in an immature, noisy state [

9].

What is missing is a head-to-head genetic look at these two pathways across both disorders. Cheung [

10] recently argued that insufficient pruning could be a central driver of ADHD, underscoring the need for direct cross-disorder tests. We answer that call by applying three complementary tools—MAGMA gene-set analysis [

11], stratified linkage-disequilibrium score regression for heritability partitioning [

12], and tissue-specific transcriptome-wide association via S-PrediXcan [

13]. Using carefully curated gene panels for glutamatergic signalling, several flavours of synaptic pruning, and negative-control sets, we interrogate parallel ASD and ADHD GWAS datasets to tease apart shared versus disorder-specific signals and, where possible, to infer the biological direction of those effects.

By weaving together these multi-omic perspectives, we aim to determine whether dysregulated pruning, altered glutamatergic transmission, or some combination best explains the overlapping yet distinct profiles of ASD and ADHD. Clarifying that biology should sharpen etiologic models and point to age-specific targets for intervention across development.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

We examined common-variant risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) using the summary statistics released by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium and iPSYCH [

4]. The discovery sample included 18,381 diagnosed cases and 27,969 controls; after adjustment to the liability scale the effective sample numbered roughly 44,000 individuals. Variant identifiers, chromosomal positions and two-sided p values were reformatted for MAGMA version 1.10 [

11].

Gene testing relied on the European ancestry panel from 1000 Genomes Phase 3 to model linkage disequilibrium. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were mapped to genes if they lay within the coding region or fell inside a window extending 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream of NCBI Build 37 gene boundaries. After quality control, 18,423 protein-coding genes entered analysis. The SNP-wise mean model in MAGMA aggregated marker signals to a gene Z score while correcting for local LD.

To explore specific biological themes we pre-registered seven gene sets.

Focused Glutamatergic: 23 glutamate receptor and plasticity genes.

Expanded glutamatergic panel: 130 genes spanning receptors, transporters and downstream cascades.

Shortened pruning panel: 38 canonical pruning genes.

Expanded pruning panel: 262 genes covering complement, microglial, axon-guidance and cytoskeletal components.

Pruning-specific set: 225 pruning genes with glutamatergic overlap removed.

Monoamine control: 101 genes.

Housekeeping control: 182 genes.

Competitive gene-set tests compared mean gene Z scores in each panel with the genome-wide background; one-sided p values were Bonferroni-corrected across the seven tests (α = 0.0071). False-discovery rates were also recorded.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

We used stratified LD-score regression (LDSC v1.0.1) to quantify how much of the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) signal lies in pre-selected functional categories [

14,

12]. The input comprised summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium meta-analysis of 18,381 cases and 27,969 controls [

4]. Only HapMap3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with minor-allele frequency greater than 5 % in Europeans and outside the extended MHC were retained.

Seven custom annotations were prepared. Five captured biology of interest—(1) 23 core glutamatergic genes (CGR_Targets_Original), (2) an expanded glutamatergic list of 130 genes, (3) a 38-gene pruning core, (4) a 262-gene extended pruning panel and (5) a 225-gene pruning set with glutamatergic overlap removed. Two served as negative controls—101 monoaminergic genes and 182 housekeeping genes. Gene coordinates (NCBI build 37) were padded by 10 kb on either side, and annotation-specific LD scores were computed with the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 European reference. Enrichment was defined as the proportion of SNP heritability explained divided by the proportion of SNPs in the annotation. One-sided P values were derived from the block-jackknife standard error and judged significant after Bonferroni adjustment for seven tests (α = 0.0071).

Transcriptome-Wide Association

We used Summary-PrediXcan, the summary-statistic implementation of PrediXcan (Barbeira et al., 2018), to estimate the relationship between genetically predicted gene expression and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). GWAS input consisted of the meta-analysis by Grove et al. (2019); odds ratios and standard errors were converted to Z-scores, and the effective sample size (44 366) was supplied to S-PrediXcan.

Expression prediction relied on GTEx v8 multi-tissue MASHR weight sets (Urbut et al., 2019; Zenodo record 3518299). Analyses were confined to six CNS tissues—frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), hippocampus, amygdala, caudate and nucleus accumbens—selected for ASD relevance. For each tissue, S-PrediXcan produced gene-level Z-statistics and p -values, incorporating the tissue-specific linkage-disequilibrium covariance matrices distributed with the MASHR models.

The same seven prespecified gene collections were interrogated. Enrichment was tested in each tissue by contrasting the absolute S-PrediXcan Z-scores for genes inside a set with those for all other genes, using one-sided Mann-Whitney U tests. False-discovery-rate (FDR) adjustment was applied within each tissue.

Cross-Disorder Comparison

To compare the pathway-level polygenic landscape of the target disorder with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), we re-ran every analytic step described above on the summary statistics from the latest ADHD genome-wide association meta-analysis; these data comprise 38,691 diagnosed cases and 186,843 controls [

3]. The replication retained all parameters that had been applied to the focal disorder. All statistical thresholds, multiple-testing corrections and quality-control filters matched those applied to the primary disorder, enabling direct head-to-head evaluation of enrichment profiles, annotation effects and transcriptome-wide signals across conditions. The analytical results for the ADHD GWAS were previously reported in detail in another paper of the author [

10].

Results

MAGMA Analysis

Six loci surpassed the genome-wide Bonferroni threshold (P < 2.7 × 10⁻⁶). Three of these lay on chromosome 20—XRN2 (P = 4.5 × 10⁻⁹), NKX2-4 (P = 1.5 × 10⁻⁸) and KIZ (P = 4.0 × 10⁻⁸). Additional signals were observed for KCNN2 on chromosome 5, MFHAS1 on chromosome 8 and MACROD2 on chromosome 20. A further 103 genes showed suggestive evidence (P < 0.001) and 1,890 reached nominal significance (P < 0.05).

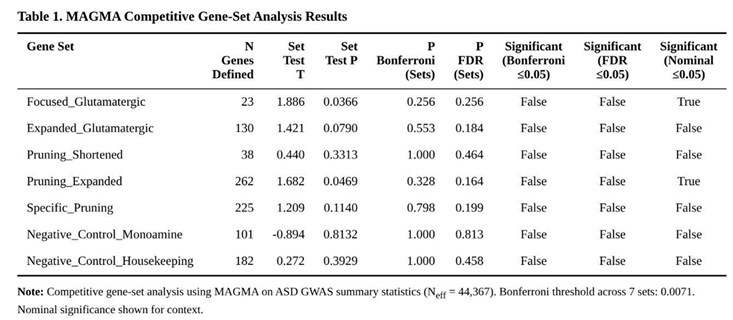

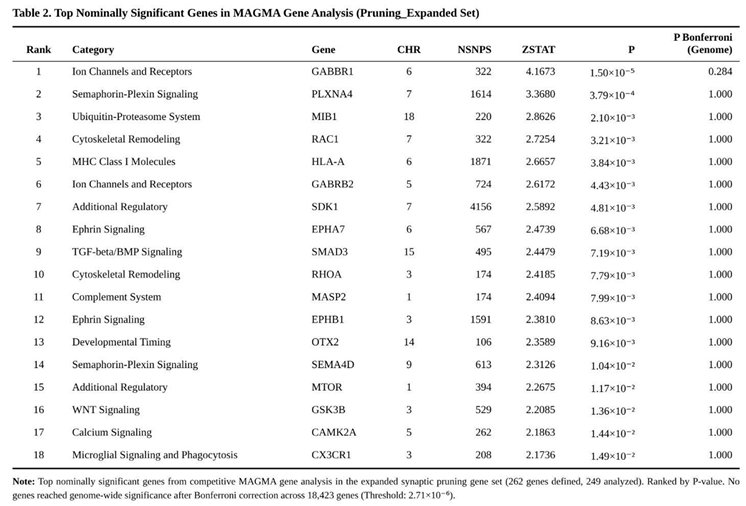

None of the seven hypothesis-driven sets cleared the study-wide Bonferroni cut-off. Nevertheless, two panels displayed nominal enrichment: the 23-gene core glutamatergic set (P = 0.037) and the 262-gene expanded pruning set (P = 0.047) (Table 1). Within the glutamatergic group, GRIA1 (P = 0.0047) and MTOR (P = 0.012) were the principal contributors. For pruning biology, leading genes included GABBR1 (P = 1.5 × 10⁻⁵), RAC1 (P = 0.0032) and HLA-A (P = 0.0038) (Table 2). Monoaminergic and housekeeping controls showed no evidence of enrichment (both P > 0.24). The pruning-specific subset, from which glutamatergic genes had been excluded, retained a non-significant trend (P = 0.114).

Collectively, these findings point to modest but convergent contributions from excitatory synaptic signalling and pruning machinery to ASD liability, although neither pathway reached stringent significance after correction for multiple testing.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

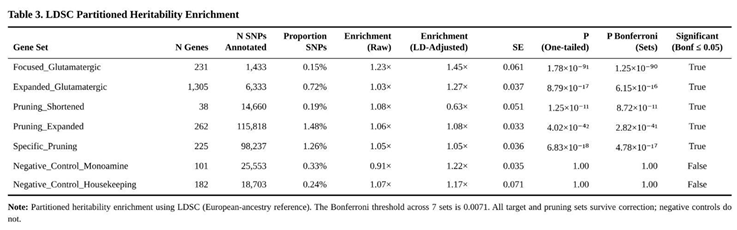

Common-variant risk for ASD was concentrated in regions assigned to glutamatergic and synaptic-pruning genes (Table 3). The 23-gene core glutamatergic set carried a 1.45-fold excess of SNP heritability relative to its SNP count (P ≈ 1 × 10⁻⁹⁰; Bonferroni-adjusted P ≈ 1 × 10⁻⁸⁹). The larger glutamatergic panel showed similar enrichment (1.27-fold; adjusted P ≈ 6 × 10⁻¹⁶).

Pruning categories were also over-represented. The 262-gene extended set displayed 1.08-fold enrichment (adjusted P ≈ 3 × 10⁻⁴¹) and the 225-gene pruning-specific list remained significant at 1.05-fold (adjusted P ≈ 5 × 10⁻¹⁷). The 38-gene core pruning group produced a suggestive signal (P = 1.3 × 10⁻¹¹) that did not survive multiple-testing correction.

Control annotations behaved as expected. Monoaminergic (1.22-fold) and housekeeping (1.17-fold) categories showed no significant enrichment (both adjusted P = 1.0).

Transcriptome-Wide Association

After alignment of GWAS and prediction SNPs, between ten and twelve thousand genes were evaluated per tissue, giving 70 396 gene-tissue tests overall. Bonferroni correction within tissues yielded one to four genome-wide significant genes per tissue. Using an FDR threshold of 0.05, 62 significant gene-tissue associations were observed, corresponding to 31 distinct genes; 5 952 additional associations were nominally significant (p < 0.05).

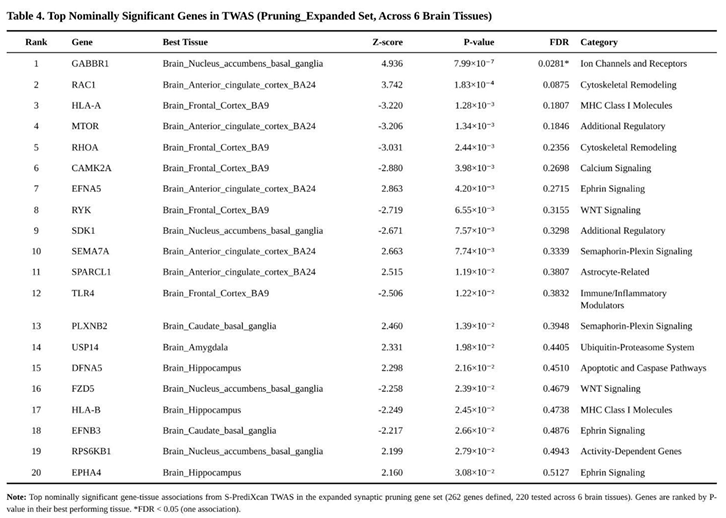

None of the seven sets survived correction for the multiple gene-set comparisons, yet pruning-related panels displayed modest shifts toward larger effects. The expanded pruning collection (262 genes) showed a 6 % inflation of |Z| relative to the genomic background (U = 31 112 137, p = 0.023). Within this set, 31 genes reached nominal significance and one survived FDR adjustment: lower predicted expression of GABBR1 in nucleus accumbens (Z = 4.94, p = 7.99 × 10⁻⁷, FDR = 0.028). A similar pattern held for the 225-gene “specific pruning” list, which removed glutamatergic overlap (enrichment 4 %, p = 0.067) and again highlighted GABBR1. Nominal pruning hits included up-regulation signals for RAC1, HLA-A and RHOA, and down-regulation for EFNA5 and SEMA7A across various tissues (Table 4).

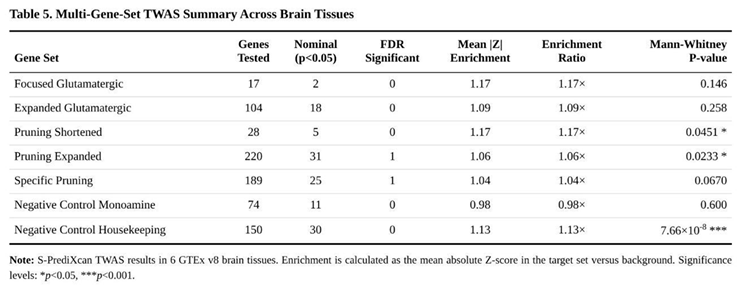

Glutamatergic panels produced weaker evidence (Table 5). The 23-gene core set showed a 17 % enrichment that did not reach significance (p = 0.146); signals were driven mainly by negative associations for MTOR and CYP2D6. The 130-gene expanded glutamatergic list yielded a non-significant 9 % enrichment (p = 0.258). Control collections behaved as expected: monoaminergic genes were null (−2 % enrichment, p = 0.600), while housekeeping genes showed a modest 13 % shift (p = 7.66 × 10⁻⁸), plausibly reflecting general neuronal expression bias rather than ASD biology.

When the four target panels (glutamatergic plus pruning) were aggregated, the mean enrichment across tissues was 11 %, compared with 6 % for the two control panels, consistent with subtle, tissue-restricted dysregulation of genes involved in synaptic pruning in ASD.

Cross-Disorder Polygenic Architecture

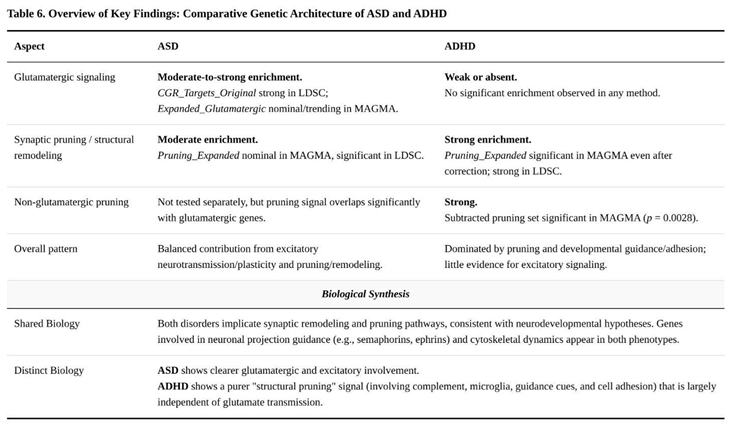

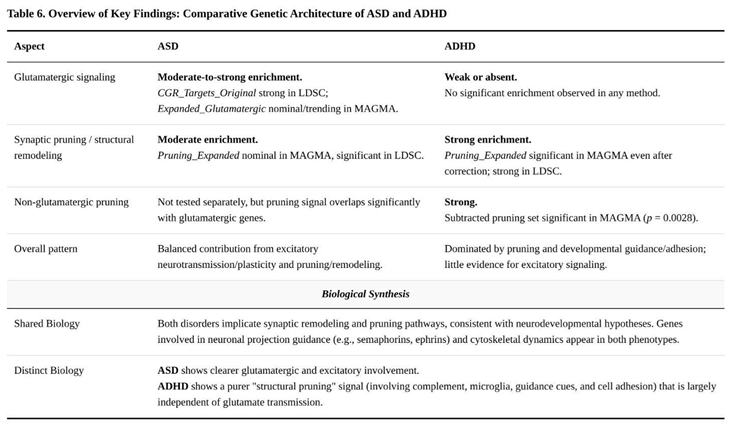

Running identical pipelines on the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) genome-wide data highlighted areas of overlap but also clear distinctions (Table 6). Within MAGMA, the expanded synaptic-pruning panel reached only nominal evidence of association for ASD (P = 0.047) yet surpassed the multiple-testing threshold in ADHD (P = 0.0008). Removing glutamatergic genes from that panel did not diminish the ADHD signal (P = 0.0028), indicating that pruning effects in ADHD do not depend on excitatory-synapse genes. Conversely, the two glutamatergic sets produced weak trends that were confined to ASD (focused set P = 0.037; expanded set P = 0.079) and were absent in ADHD.

Stratified LD-score regression corroborated these patterns. Pruning annotations were enriched in both disorders, showing an identical 1.08-fold inflation of heritability, but the pruning-only annotation fell below significance in ADHD (1.04-fold, P = 0.11). Glutamatergic annotations were strongly enriched in ASD (focused set 1.45-fold, P ≈ 10⁻⁹⁰; expanded set 1.27-fold, P ≈ 10⁻¹⁶) and completely null in ADHD. Neither disorder showed enrichment for the negative-control annotations.

Transcriptome-wide association in six cortical and subcortical tissues yielded modest pruning signals for ASD: the expanded pruning list produced a 1.06-fold increase in absolute Z-scores (Mann–Whitney P = 0.023) and one false-discovery-rate (FDR)-significant gene—down-regulation of GABBR1 in nucleus accumbens (Z = –4.94). In ADHD, the pruning-only list generated five FDR-significant genes, including up-regulation of PLXNB2 (Z = 4.51) and down-regulation of SEMA3F (Z = –4.08), yet the overall enrichment statistic was neutral. Glutamatergic sets again showed little evidence of association in either condition.

Discussion

Interpretation of Results

Taken together, these results indicate that aberrant synaptic pruning is a convergent biological theme across ASD and ADHD, but the underlying molecular emphasis differs. In ADHD the pruning effect remains after glutamatergic genes are removed and centres on guidance molecules such as SEMA3F and cytoskeletal regulators such as RHOA, consistent with a general delay of cortical refinement reported in longitudinal imaging [

9]. ASD, by contrast, shows pruning enrichment intertwined with glutamatergic dysregulation; the nucleus-accumbens signal for GABBR1 down-regulation suggests that inhibitory feedback onto excitatory circuits may be weakened, potentially amplifying excitation/inhibition imbalance [

5] and precipitating compensatory over-pruning.

These distinctions refine earlier observations that complement-driven synapse elimination contributes to neurodevelopmental disorders [

15]. Our data imply that ADHD involves widespread structural-remodelling deficits largely independent of excitatory signalling, whereas ASD implicates excitatory pathways directly. Nonetheless, shared loci on chromosome 20 (XRN2, NKX2-4, KIZ) support a common neurodevelopmental liability, echoing the high clinical co-occurrence of the two diagnoses [

2]. Directionally, most risk alleles promote greater pruning activity, yet longitudinal imaging and rare-variant studies will be required to pinpoint time windows and causality.

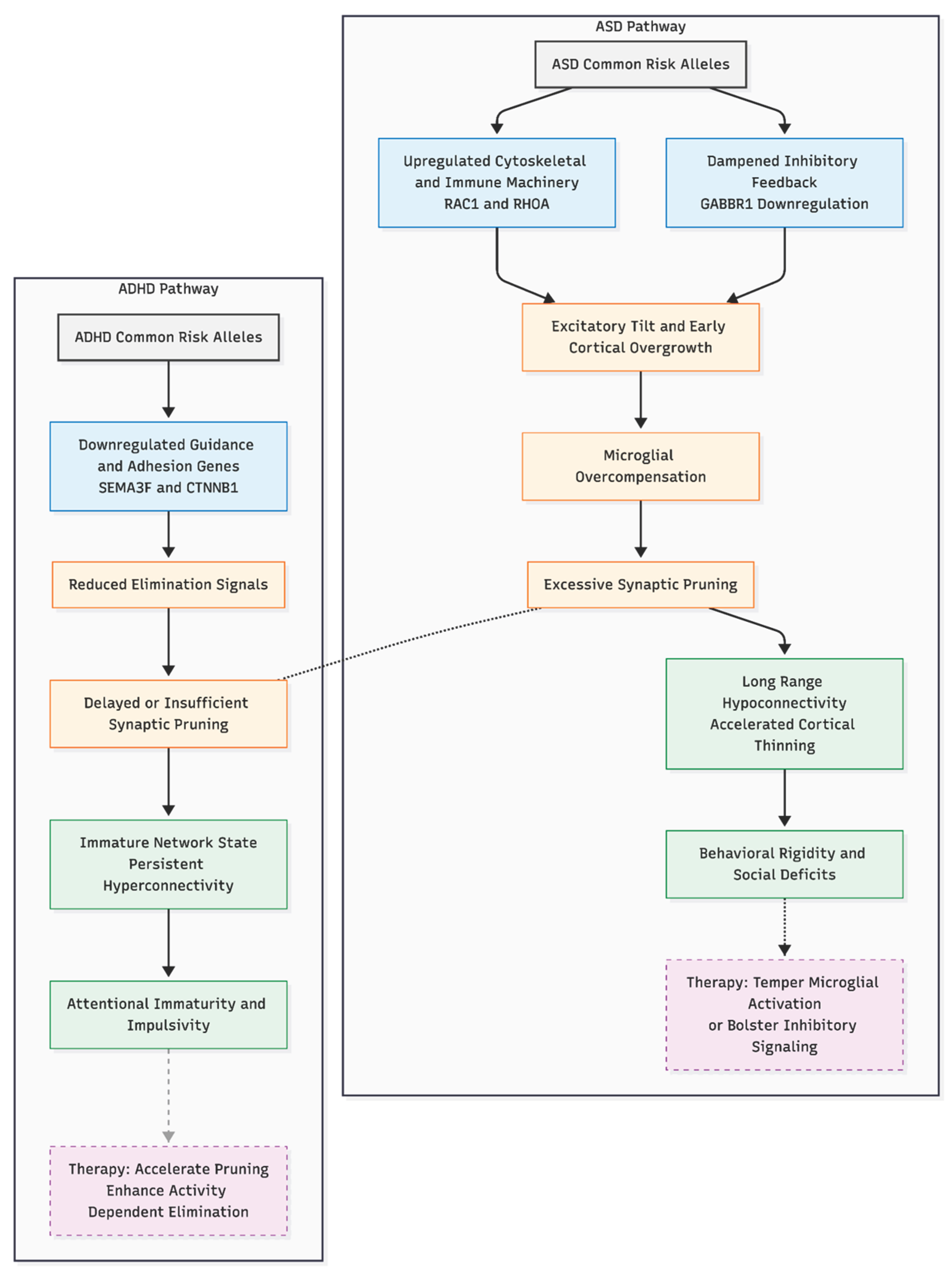

An Etiological Model that Links Pruning Pressure with Glutamatergic Control

The convergent genetic patterns reported here suggest that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may arise when the timing and intensity of microglia-driven synapse removal are no longer properly coordinated with glutamatergic circuit plasticity early in life. We built this working model by integrating three empirical strands. First, both pruning and glutamate gene sets showed nominal effects in MAGMA, whereas stratified LD-score regression produced clear heritability inflation for pruning (1.08-fold, P ≈ 10⁻⁴¹) and strong glutamatergic enrichment (focused set 1.45-fold). Second, transcriptome-wide association pointed to reduced inhibitory feedback within reward circuitry (for example, GABBR1 down-regulation in nucleus accumbens, Z = –4.94). Third, previous neuropathological work documents early synaptic over-production followed by abnormal elimination [

7] and excessive complement activity [

16,

8].

Together these findings outline a two-step cascade. Common ASD risk alleles appear to boost the activity of cytoskeletal and immune pruning machinery (positive TWAS Z-scores for RAC1 and RHOA) while simultaneously dampening inhibitory or homeostatic plasticity hubs such as GABBR1. The resulting excitatory tilt is expected to fuel early cortical over-growth; microglia then over-compensate, pruning too many synapses and producing the characteristic long-range hypo-connectivity and behavioral rigidity described by Rubenstein and Merzenich [

5] and by Uzunova et al. [

6]. The model predicts accelerated cortical thinning after infancy and provides a mechanistic bridge between the excitatory–inhibitory imbalance hypothesis and more recent accounts that emphasize immune-regulated circuit refinement.

Relationship to the ADHD Pruning Hypothesis

Cheung's [

10] re-analysis of the latest ADHD GWAS framed that disorder as one of delayed or insufficient pruning, causing persistent hyper-connectivity and attentional immaturity. Our ASD model shares the theme of pruning dysregulation but differs in direction and in its dependence on glutamatergic control. Whereas ADHD signals persisted after glutamate genes were removed (SEMA3F and CTNNB1 down-regulation pointing to reduced elimination), ASD heritability is dominated by loci that couple pruning genes to excitatory transmission. Clinically, this dichotomy dovetails with ASD's social-communication core and ADHD's executive-attention profile [

2] and aligns with imaging work showing expedited cortical thinning in ASD but protracted maturation in ADHD [

9].

Figure 1.

Divergent synaptic pruning mechanisms in ASD versus ADHD. The model contrasts the glutamate-dependent "over-pruning" cascade proposed for Autism Spectrum Disorder (left) with the "under-pruning" or delayed maturation hypothesis for ADHD (right). In ASD, genetic risk factors drive an excitatory tilt that triggers microglial over-compensation, resulting in accelerated cortical thinning. In contrast, ADHD risk alleles are associated with reduced elimination signals, leading to persistent hyper-connectivity.

Figure 1.

Divergent synaptic pruning mechanisms in ASD versus ADHD. The model contrasts the glutamate-dependent "over-pruning" cascade proposed for Autism Spectrum Disorder (left) with the "under-pruning" or delayed maturation hypothesis for ADHD (right). In ASD, genetic risk factors drive an excitatory tilt that triggers microglial over-compensation, resulting in accelerated cortical thinning. In contrast, ADHD risk alleles are associated with reduced elimination signals, leading to persistent hyper-connectivity.

If excessive, glutamate-sensitive pruning contributes to ASD, early interventions that temper microglial activation or bolster inhibitory signaling could be beneficial, whereas later phases might require agents that foster synaptogenesis or circuit stabilization. Conversely, ADHD might benefit from strategies that accelerate—or mimic—the pruning step, for example by enhancing activity-dependent elimination. The opposing directions implied here (over-pruning in ASD, under-pruning in ADHD) offer a framework for stratified trials and may explain the frequent co-diagnosis when genetic liabilities from both ends of the pruning spectrum co-occur.

Novelty and Broader Implications

Research on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has long pointed to two biological themes—synaptic pruning abnormalities and glutamatergic imbalance [

5,

9,

7]. What has been missing is a side-by-side genetic test of those themes across both conditions. By applying identical pathway analyses to the most recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) results for ASD [

4] and ADHD [

3], the present work delivers that comparison. The results sharpen the picture: ASD liability aligns with a combination of excitatory-inhibitory disruption and excessive pruning, whereas ADHD risk maps more cleanly onto delayed or insufficient pruning that shows little overlap with glutamatergic genes. Our results help explain why earlier cross-disorder studies focused on shared risk but had trouble explaining different symptom profiles. They build on Cheung's [

10] idea that pruning delay is a key part of ADHD. Eliminating overlapping genes to isolate "pure" pruning effects was particularly enlightening, uncovering disorder-specific genetic signatures that conventional overlap metrics may conceal.

These insights matter for theory and practice. They support developmental-timing models in which early hyperexcitability in ASD drives compensatory over-pruning, while slower structural refinement underlies ADHD. Such models can steer circuit-level studies—examining, for instance, social-reward pathways in ASD or prefrontal control networks in ADHD—and may help tailor interventions. Polygenic scores that weight pruning versus glutamatergic components could, in principle, forecast treatment response. For example, therapies that modulate microglial activity might suit individuals with ASD-linked pruning excess, whereas plasticity-enhancing agents could benefit those with ADHD-related immaturity. The data also give a mechanistic rationale for mixed clinical pictures: some children may share early pruning liability but diverge later according to glutamatergic influences.

Limitations

These findings should be read with several caveats in mind. First, genome-wide association studies focus on common variants and therefore explain only a slice of total heritability; rare mutations and copy-number variants—well known to play a sizeable role in ASD—were not part of our analysis. Second, the transcriptome-wide association results rest on adult brain data from GTEx. Gene-expression programs during childhood and adolescence, when synaptic pruning is at its peak, may look quite different, so we could have missed development-specific isoforms. Third, both discovery GWAS were drawn largely from individuals of European ancestry, which limits how confidently we can extend the results to other populations. Fourth, analytic choices such as assigning SNPs to genes within ±10–35 kb windows inevitably add a degree of arbitrariness. Finally, any directionality we infer from TWAS—for example, the predicted down-regulation of GABBR1—is correlative, not causal. Rigorous functional work will be needed to confirm and extend these genetic hints.

Conclusion

Taken together, the analyses frame ASD and ADHD along a continuum of pruning dysregulation: ASD exhibits glutamatergic-linked over-pruning, whereas ADHD shows glutamatergic-independent pruning delay. This mechanistic lens connects genetic risk to developmental brain trajectories and helps explain clinical diversity. Larger, ancestrally diverse cohorts, rare-variant integration, and longitudinal imaging will be the next steps, but the current evidence already points toward timing-specific therapeutic strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. .

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable. .

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, Y. The co-occurrence of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children – What do we know? Front Hum Neurosci. 2014, 8, 268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demontis, D; Walters, GB; Athanasiadis, G; et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat Genet. 2023, 55, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, J; Ripke, S; Als, TD; et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019, 51, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, JLR; Merzenich, MM. Model of autism: Increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003, 2, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzunova, G; Pallanti, S; Hollander, E. Excitatory/inhibitory imbalance in autism spectrum disorders: Implications for interventions and therapeutics. World J Biol Psychiatry 2016, 17, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G; Gudsnuk, K; Kuo, SH; et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron 2014, 83, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y; Paolicelli, RC; Sforazzini, F; et al. Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2014, 17, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P; Eckstrand, K; Sharp, W; et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104, 19649–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. From maturational delay to insufficient pruning: Genetic insights into ADHD neurobiology; Preprints, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, CA; Mooij, JM; Heskes, T; et al. MAGMA: Generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015, 11, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, HK; Bulik-Sullivan, B; Gusev, A; et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, AN; Dickinson, SP; Bonazzola, R; et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulik-Sullivan, BK; Loh, PR; Finucane, HK; et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, A; Bialas, AR; de Rivera, H; et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 2016, 530, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C; Yue, H; Hu, Z; et al. Microglia mediate forgetting via complement-dependent synaptic elimination. Science 2020, 367, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |