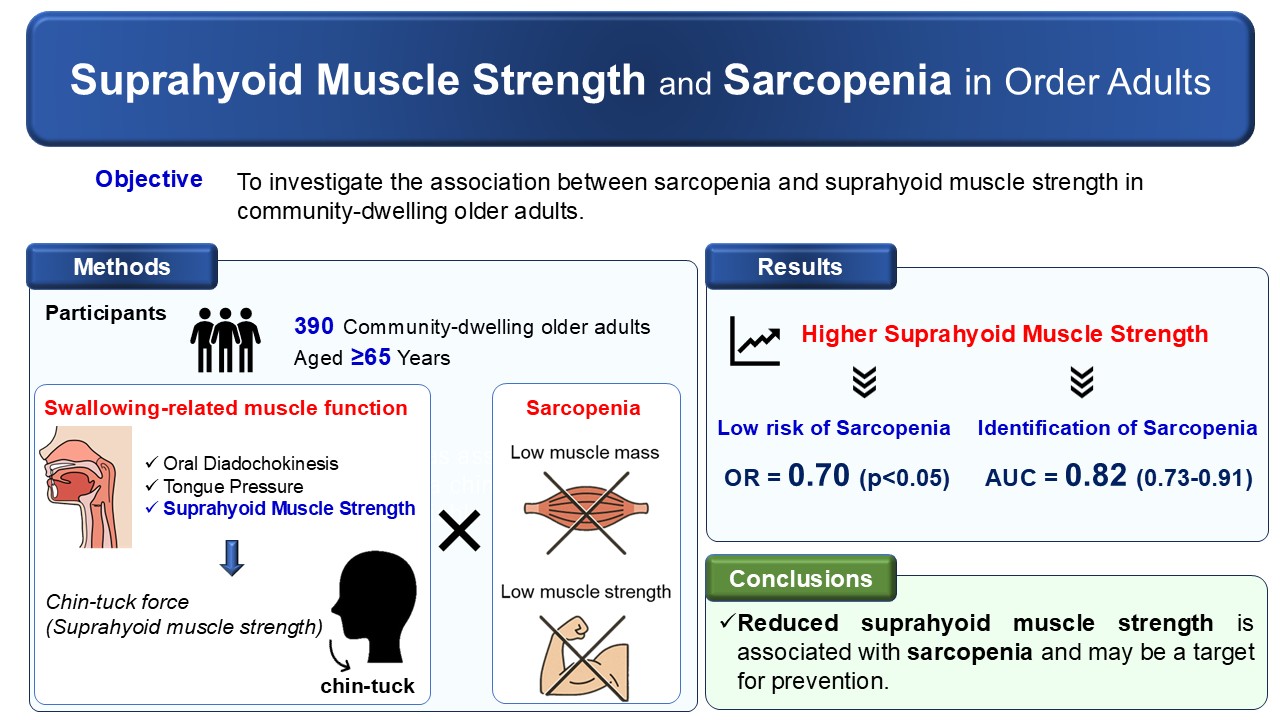

1. Introduction

Sarcopenia is defined as a progressive, generalized skeletal muscle disease characterized by declines in both muscle mass and muscle strength with advancing age [

1]. It is recognized as a major geriatric risk factor, and is associated with numerous adverse health outcomes, including increased risks of falls, fractures, reduced basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL and IADL), cognitive impairment, hospitalization, and mortality [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. A meta-analysis estimated the global prevalence of sarcopenia to be approximately 10% in both men and women [

8], indicating that it is a common age-related disease. Therefore, early detection and preventive interventions for sarcopenia are essential clinical priorities for healthcare professionals caring for older adults.

Multiple risk factors contribute to the development of sarcopenia. Physical inactivity and malnutrition are widely recognized modifiable factors, whereas acute and chronic wasting conditions caused by organ failure, inflammatory disease, malignancy, and endocrine disorders are also important contributors [

9]. In particular, in community-dwelling older adults, adequate physical activity and nutritional intake are strongly recommended for preventing sarcopenia [

10]. In addition, in the most recent consensus update by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS), swallowing dysfunction (dysphagia) has also been mentioned as a risk factor [

11], and is a common geriatric syndrome among community-dwelling older adults [

12], with a systematic review reporting a prevalence of 20.35% [

13].

Recently, increasing attention has been directed toward the relationship between sarcopenia and swallowing dysfunction, highlighted through the concept of sarcopenic dysphagia, which is characterized by reduced muscle mass and strength in both whole-body musculature and swallowing-related muscles [

14]. Although longitudinal evidence remains limited, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown clear associations between sarcopenia and impaired swallowing-related muscle function in community-dwelling older people [

15]. Accordingly, swallowing-related muscle weakness may represent an important risk factor for sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults.

Regarding the swallowing-related muscles and sarcopenia, several studies have reported associations between tongue pressure, which is widely used as an indicator of swallowing muscle strength, and sarcopenia [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, among swallowing-related muscles, the suprahyoid muscle group, which plays a crucial role in hyoid elevation and opening of the pharyngoesophageal segment, may be particularly important. Age-related changes in the geniohyoid muscle, including reduced muscle mass and increased intramuscular fat, have been documented [

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, targeted interventions, such as the Shaker exercise and chin-tuck in resistance training, have demonstrated improvements in swallowing function by strengthening the suprahyoid muscles [

23,

24,

25]. Thus, assessment of suprahyoid muscle function may be essential for understanding swallowing-related risk factors for sarcopenia.

Despite these findings, research examining the association between suprahyoid muscle strength and sarcopenia remains insufficient, primarily due to a lack of suitable assessment methods. To address this gap, we developed a device designed to measure the strength exerted during the chin-tuck maneuver, specifically targeting suprahyoid muscle strength, and confirmed its reliability and validity [

26]. Although previous studies have assessed tongue pressure and ultrasound-based morphology of the suprahyoid muscles, few have directly examined the relationship between suprahyoid muscle strength and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Therefore, the aim of this cross-sectional study was to clarify the relationship between sarcopenia and the strength of the suprahyoid muscles in community-dwelling older adults. By further elucidating the association between swallowing-related muscle function and overall muscle health, this study may contribute to identifying potential therapeutic targets for sarcopenia prevention and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This cross-sectional observational study included 390 community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and above who were living independently in Sagamihara City, Japan. Participants were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers and posters displayed in public facilities. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were aged 65 years or older, had no restrictions on oral food intake, as verified by the Functional Oral Intake Scale [

27], and were independent in their activities of daily living. Individuals were excluded if they were certified as needing support or care by the Japanese long-term insurance care system, had neck pain or neurological symptoms, such as numbness or weakness associated with cervical myelopathy or cervical disc herniation, had neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease or dementia, if they were institutionalized, or if they had a pacemaker. These exclusion criteria were confirmed through a self-reported questionnaire and a face-to-face interview conducted by trained researchers.

Sample size was calculated using a previously reported mean difference in tongue pressure of 5.4 kPa, and a standard deviation of 7.4 kPa between individuals with and without sarcopenia [

15], assuming a sarcopenia prevalence of 6.2% [

28], an alpha level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.80. Based on these parameters, the required sample size was estimated to be 272 participants.

The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the School of Allied Health Sciences at Kitasato University (Approval No. 2023-008), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

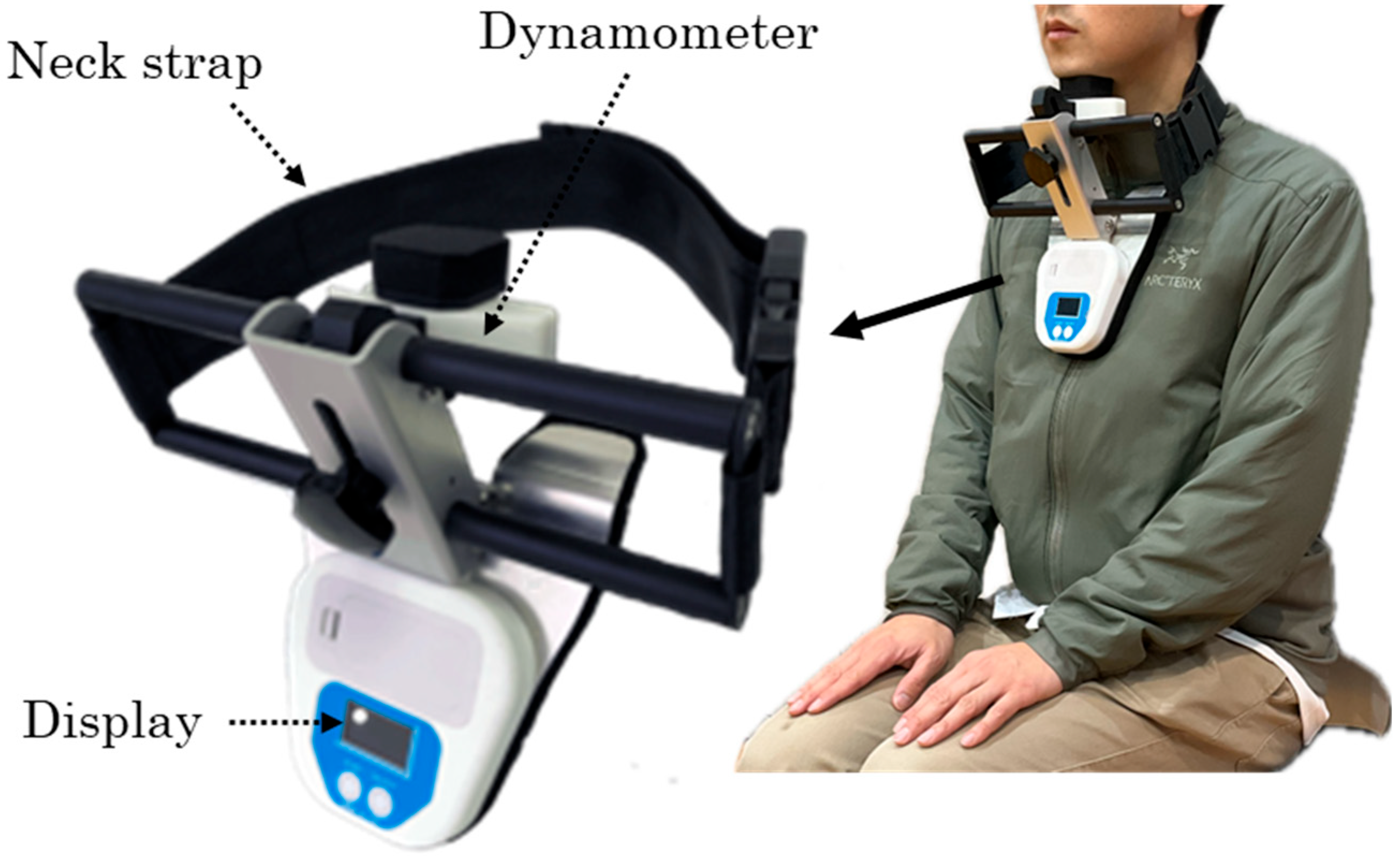

2.2. Assessment of Swallowing-Related Muscle Function and Oral Function

Swallowing-related muscle function was evaluated through measurement of suprahyoid muscle strength, tongue pressure, and oral diadochokinesis (ODK), and oral function was assessed using an established oral frailty scale. Suprahyoid muscle strength was measured as the maximum force generated during a chin-tuck maneuver using a dynamometer (Neckforce, T.K.K. 3359, SANKA Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan) (

Figure 1). The device was positioned with the participant’s neck in the neutral position, and measurements were taken while the participant sat on a standard armless chair with their back resting against the backrest. Participants were instructed to tuck their chin maximally toward the manubrium sterni and maintain the contraction for five seconds, during which the maximum force was recorded. Two trials were performed with a 30-second rest period between trials, and the mean value was used for analysis. Previous studies have demonstrated high reliability of this method, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.82 to 0.89, supporting its validity for assessing swallowing-related muscle strength [

26].

Tongue pressure was measured using a standardized device (TPM-02, JMS Co., Ltd., Hiroshima, Japan) following previously established procedures [

29]. Three measurements were obtained with a 30-second interval between trials, and the average value was used for analysis. ODK was assessed using a dedicated measurement device (T.K.K. 3351, SANKA Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan). Participants were instructed to repeat the syllables “pa,” “ta,” and “ka” as rapidly as possible, Participants were instructed to separately repeat the syllables “pa,” “ta,” and “ka” as rapidly as possible, for 5 seconds each, and the number of repetitions per second for each syllable was recorded. Oral function was further assessed using the Oral Frailty Five-Item Checklist (OF-5), which consists of self-reported items addressing fewer teeth, chewing difficulty, swallowing difficulty, dry mouth, and reduced articulatory motor skills [

30]. Possible total scores range from 0 to 5, with scores of two or higher indicating oral frailty.

2.3. Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia was defined according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) 2025 criteria [

11]. Muscle strength was assessed using handgrip strength measured with a Smedley-type dynamometer (T.K.K. 5401, SANKA Co., Ltd.). Values below 28 kg for men and 18 kg for women were classified as low muscle strength. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody 430; InBody Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and skeletal muscle mass index (SMI) was calculated by dividing ASM by height (in meters) squared (kg/m

2). Low muscle mass was defined as an SMI below 7.0 kg/m

2 for men and below 5.7 kg/m

2 for women. Participants were classified as having sarcopenia if they met both low muscle strength and low muscle mass criteria.

2.4. Potential Confounding Factors

Potential confounders were assessed using a combination of self-reported questionnaires and objective measures. The questionnaire collected information on age, physician-diagnosed comorbidities, number of prescribed medications, living arrangement (living alone or not), depressive symptoms, and dietary protein intake. Polypharmacy was defined as the use of six or more medications. Functional capacity was assessed using the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence (TMIG-IC), which evaluates higher-level functional abilities such as IADL and social roles, and ranges from 0 to 13 points, with higher scores indicating better functional capacity [

31]. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the five-item Geriatric Depression Scale, with scores of two or higher indicating the presence of depressive symptoms [

32]. Protein intake status was assessed using consumption markers for protein intake from the Mini Nutritional Assessment

®, including daily intake of dairy products, consumption of legumes or eggs at least twice weekly, and daily intake of meat or fish [

33].

Mobility was assessed using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test performed at the fastest walking speed, and cognitive function was assessed using the Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured height and weight.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Initially, the associations between the presence of sarcopenia and swallowing-related muscle functions, oral function, and all potential confounding factors were examined using t-tests or Fisher’s exact tests. Logistic regression analysis was then conducted to examine the association of swallowing-related muscle function and oral function with sarcopenia, with the presence of sarcopenia as the dependent variable, each swallowing-related muscle function and oral function as the independent variables, and potential confounding factors as covariates. Covariates were selected based on prior literature and clinical relevance of the potential confounding factors. Variables that showed an association with sarcopenia in univariate analysis were also considered as candidates. Finally, collinearity was considered using the variance inflation factor.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the discriminatory ability of each swallowing-related muscle function for identifying sarcopenia, and an area under the curve (AUC) ≥ 0.7 was considered as acceptable discrimination [

34]. In addition, the cutoff values, sensitivity, and specificity were determined using the Youden index. Furthermore, comparisons of discriminatory ability among swallowing-related muscle functions were conducted using DeLong’s test for AUCs, net reclassification improvement (NRI), and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). The significance level was set at 5%, and all statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

Descriptive statistics for all collected variables are presented in

Table 1. Regarding sarcopenia, 35 participants had low muscle strength and 104 had low muscle mass; consequently, 21 participants (5.4%) were diagnosed with sarcopenia. Among medical conditions, hypertension was the most frequently reported comorbidity, whereas other diseases—including diabetes mellitus, stroke, kidney disease, respiratory disease, and heart disease—were relatively uncommon. Comorbidities and polypharmacy were not significantly associated with the presence of sarcopenia. Living arrangement (living alone or depressive symptoms, TMIG-IC score, and dietary protein intake were also not significantly associated with sarcopenia. In contrast, age, BMI, TUG time, and TMT part B time differed significantly by sarcopenia status. Participants with sarcopenia were older, had lower BMI, and demonstrated longer TUG and TMT Part B times compared with those without sarcopenia.

3.2. Swallowing-Related Muscle Function, Oral Function, and Sarcopenia

Tongue pressure, ODK “ta,” ODK “ka,” and suprahyoid muscle strength were all significantly associated with sarcopenia. Individuals with sarcopenia exhibited lower values of these measures compared with those without sarcopenia in univariate analysis (

Table 1). Oral frailty, however, did not differ by sarcopenia status.

To further examine these associations, logistic regression analyses adjusted for potential confounders were conducted. For ODK, only the syllable “ta” was included in the models because it showed the largest effect size (Cohen’s d) among the ODK measures. In Model 1, age, sex, and BMI were included as confounders; in Model 2, all potential confounders were included. In both models, only suprahyoid muscle strength remained significantly associated with sarcopenia among the swallowing-related muscle function and oral function measures. Higher suprahyoid muscle strength was associated with lower odds of sarcopenia (Model 1: Odd ratio (OR) = 0.64, p < 0.001; Model 2: OR = 0.70, p < 0.05) (

Table 2).

1 TMIG-IC: Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence, 2 ODK: Oral diadochokinesis, 3 OR: odds ratio, 4 95%CI; 95% confidence interval. The highest variance inflation factor values for the independent variables were 1.61 and 2.20 for Models 1 and 2, respectively. Model 1 included age, sex, BMI, oral frailty, ODK, tongue pressure, and suprahyoid muscle strength. Model 2 additionally included diabetes mellitus, TMIG-IC score, living alone, the Timed Up and Go test, and the Trail Making Test.

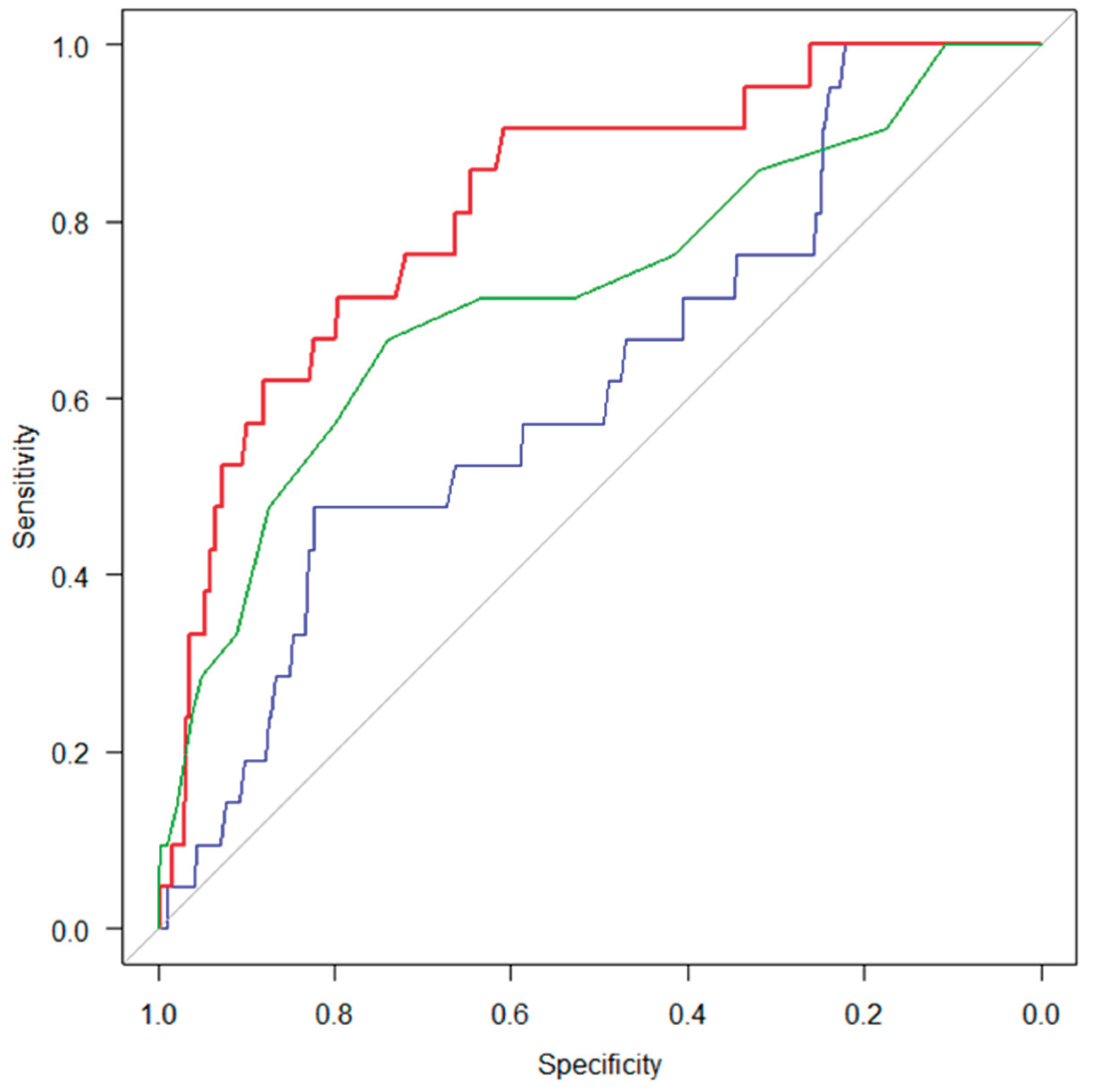

3.3. Discriminative Abilities of Swallowing-Related Muscle Function for Sarcopenia

ROC analyses were conducted to assess the discriminative abilities of ODK “ta,” tongue pressure, and suprahyoid muscle strength for identifying sarcopenia in the total sample and in sex-stratified subgroups (

Table 3). The AUC for suprahyoid muscle strength was higher than those for both ODK and tongue pressure in the overall sample, as well as in the gender-specific analyses. Notably, when comparing discriminative performance among the swallowing-related muscle function measures, the AUC for suprahyoid muscle strength was significantly larger than that for tongue pressure (DeLong’s test, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2). The superiority of suprahyoid muscle strength over tongue pressure was further supported by NRI and IDI analyses (NRI = 0.893, 95% CI = 0.517–1.270, p < 0.001; IDI = 0.086, 95% CI = 0.046–0.127, p < 0.001). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were observed between suprahyoid muscle strength and ODK “ta” in their discriminative abilities, as indicated by both DeLong’s test and the NRI and IDI analyses.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional observational study, we examined the association between swallowing-related muscle function and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. An important strength of the present study is that in addition to tongue pressure and oral diadochokinesis (ODK), which have been widely used in previous research and clinical practice, we assessed suprahyoid muscle strength as an indicator of swallowing-related muscle function. Our findings showed that suprahyoid muscle strength was significantly associated with sarcopenia even after adjusting for potential confounders. Moreover, suprahyoid muscle strength demonstrated good discriminatory ability for identifying sarcopenia. Previous studies in related fields have reported associations between tongue pressure or ODK and sarcopenia [

15,

35]. Consistent with these findings, the present study also found that both tongue pressure and ODK were associated with sarcopenia in univariate analyses. However, few investigations have specifically examined the relationship between suprahyoid muscle strength and sarcopenia. Therefore, the findings of this study provide novel insights into the association between swallowing-related musculature and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults.

Evidence regarding the association between suprahyoid muscle strength and sarcopenia remains limited. A previous study examined this relationship using jaw-opening force as an index of suprahyoid muscle strength [

17], and suggested a potential association with sarcopenia. However, interpretation of its findings was limited by sex-specific inconsistencies and insufficient adjustment for confounding factors. In the present study, suprahyoid muscle strength was assessed by measuring the force generated during the chin tuck maneuver. Previous studies using surface electromyography have demonstrated that the chin tuck maneuver increases muscle activity in the suprahyoid muscles [

36,

37]. Moreover, chin tuck has been reported to be a robust method that enhances suprahyoid muscle activity, while minimizing variability due to differences in task instructions [

38]. Kinematic analyses of swallowing have further shown that tucking the chin facilitates vertical displacement of the epiglottis and narrowing of the airway entrance during swallowing [

39]. Additionally, chin tuck against resistance has been identified as an effective therapeutic intervention for improving oropharyngeal dysphagia [

25,

40]. Taken together, these findings support the validity of measuring force generated during the chin tuck maneuver as an indicator of swallowing-related muscle strength, particularly that of the suprahyoid muscles.

Regarding the association between swallowing-related muscle function and sarcopenia, the present study found that ODK, tongue pressure, and suprahyoid muscle strength were all associated with sarcopenia in univariate analyses. Swallowing function is essential for adequate nutritional intake, and involves a variety of swallowing-related muscles, including those related to mastication and occlusion, as well as muscles responsible for laryngeal elevation and descent during swallowing [

41]. The results of this study suggest that lower skeletal muscle mass and strength may be associated with various swallowing-related muscle functions, not just that of specific muscles such as the tongue. In contrast, oral frailty was not associated with sarcopenia, even in univariate analyses, in the present study. Previous longitudinal observational studies have reported oral frailty as a predictor of sarcopenia [

42]; however, those studies assessed oral frailty using objective measures. The assessment tool used in the present study, the OF-5, although validated, is based on subjective self-reported measures. Subjective assessments of oral function have been reported to be influenced by depressive symptoms [

43], which may limit their ability to accurately reflect actual oral function. Therefore, the present findings suggest that, when evaluating swallowing function in relation to sarcopenia, objective assessments of swallowing-related muscle function may provide more reliable information.

Among the swallowing-related muscle function measures assessed in the present study, only suprahyoid muscle strength remained significantly associated with sarcopenia after adjustment for potential confounders. In addition, suprahyoid muscle strength demonstrated acceptable discriminatory ability for sarcopenia, and showed the highest discriminative performance among the measured variables. These findings suggest that suprahyoid muscle strength may be more closely associated with sarcopenia than other swallowing-related muscle functions in community-dwelling older adults. However, the underlying reasons for this observation cannot be clearly determined based on the results of this study alone. One possible explanation may relate to functional differences during swallowing between the tongue, which is assessed by tongue pressure and ODK, and the suprahyoid muscles. The tongue plays a primary role in propelling the bolus into the pharynx during the oral phase of swallowing, whereas the suprahyoid muscles contribute to laryngeal elevation and closure of the airway entrance during the pharyngeal phase [

41]. The suprahyoid muscles have been reported to be affected by age-related changes, and diminished activity of these muscles is considered one of the mechanisms responsible for aspiration in older adults [

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, a decrease in upper esophageal sphincter opening diameter and prolongation of pharyngeal clearance time—both of which involve suprahyoid muscle function—have been documented in older adults [

44,

45]. In contrast, tongue function has been reported to be influenced by factors other than swallowing, such as social interaction and opportunities for vocalization in daily life [

46,

47]. Taken together, these findings suggest that suprahyoid muscle function may more sensitively reflect swallowing dysfunction in older adults and may be more closely associated with sarcopenia, potentially through pathways related to undernutrition. Nevertheless, further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between suprahyoid muscle strength and sarcopenia. Despite this limitation, the present findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive and objective assessment of swallowing-related muscle function in older adults, including evaluation of suprahyoid muscle strength.

Several limitations of this study needed to be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes any inference regarding causal relationships between swallowing-related muscle function and sarcopenia. It is, therefore, not possible to determine whether impairments in swallowing-related muscle function contribute to the development of sarcopenia or whether sarcopenia itself leads to decline in swallowing-related muscle function. Second, the study population consisted exclusively of community-dwelling older adults; thus, generalizability of the findings to frailer populations, such as institutionalized individuals or those requiring long-term care, may be limited. Third, although the chin tuck maneuver has been shown to robustly activate the suprahyoid muscles, the force measured during this task may not exclusively reflect suprahyoid muscle strength, as contributions from other cervical muscles (e.g., the sternocleidomastoid muscle) cannot be completely excluded. In addition, direct assessments of muscle morphology or muscle mass using imaging techniques were not performed. Fourth, despite adjustment for multiple potential confounders, residual confounding by unmeasured factors, such as detailed nutritional intake, inflammatory status, and physical activity levels, cannot be ruled out. Finally, swallowing function was evaluated primarily through muscle function measurements rather than comprehensive instrumental swallowing assessments, such as videofluoroscopic or endoscopic examinations. These limitations highlight the need for future longitudinal and interventional studies to clarify the temporal relationships and underlying mechanisms linking swallowing-related muscle function, particularly suprahyoid muscle strength, with sarcopenia in older adults. The results of this study suggest that lower skeletal muscle mass and strength may be associated not only with specific muscles, such as the tongue, but also with other swallowing-related muscle function.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the association between sarcopenia and swallowing-related muscle function, including suprahyoid muscle strength, tongue pressure, and ODK, in community-dwelling older adults. Suprahyoid muscle strength, assessed by the force generated during the chin tuck maneuver, was significantly associated with sarcopenia even after adjustment for potential confounders, whereas tongue pressure and ODK were not independently associated with sarcopenia. In addition, suprahyoid muscle strength demonstrated acceptable discriminatory ability for sarcopenia, and showed the highest discriminative performance among the swallowing-related muscle function measures evaluated. These findings suggest that, when assessing swallowing-related muscle function in relation to sarcopenia among community-dwelling older adults, a comprehensive and objective evaluation that includes suprahyoid muscle strength may be particularly informative.

6. Patents

Dr. Kamide and Dr. Murakami are the inventors of the measuring device for suprahyoid muscle strength (Patent No. 7495133), which is registered with the Japan Patent Office.

Author Contributions

N.K. contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of subjects and data, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. T.M., T.S., M.A., and M.S. contributed to acquisition of subjects and data and data interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by N.K., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences (Grant-in-Aid for Research Project, No. 2025-025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the School of Allied Health Sciences at Kitasato University (Approval No. 2023-008).

Informed Consent Statement

The purpose and content of the study were explained to the participants both orally and in a written document. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

SANKA Co., Ltd. provided the suprahyoid muscle strength measuring device (Neckforce, T.K.K. 3359, SANKA Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan) free of charge for this study. The company had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. Dr. Kamide and Dr. Murakami are the inventors of the device for measuring suprahyoid muscle strength (Patent No. 7495133), which is registered with the Japan Patent Office.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASM |

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| IADL |

Instrumental activities of daily living |

| IDI |

Integrated discrimination improvement |

| NRI |

Net reclassification improvement |

| ODK |

Oral diadochokinesis |

| OF-5 |

Oral Frailty Five-Item Checklist |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| SMI |

Skeletal muscle mass index |

| TMIG-IC |

Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence |

| TMT |

Trail Making Test |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go |

References

- Kirk, B.; Cawthon, P.M.; Arai, H.; Ávila-Funes, J.A.; Barazzoni, R.; Bhasin, S.; Binder, E.F.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Chen, L.K.; et al. The conceptual definition of sarcopenia: Delphi consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS). Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Zaaria, M.; Pasleau, F.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Health outcomes of sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, Q.; Ge, M.; Dong, B. Association of sarcopenia and fractures in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Hao, Q.; Hai, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, L.; Dong, B. Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2017, 103, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cao, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H. Association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in older people: A meta-analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Pham, V.K.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Lim, W.K.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C.; Alcazar, J.; Aprahamian, I.; Batsis, J.A.; Yamada, Y.; Prado, C.M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, D.; Lim, W.S.; Sim, M.; et al. Health outcomes of sarcopenia: A consensus report by the outcome working group of the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS). Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, G.; Keshtkar, A.; Soltani, A.; Ahadi, Z.; Larijani, B.; Heshmat, R. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of general population studies. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokata, H.; Shimada, H.; Satake, S.; Endo, N.; Shibasaki, K.; Ogawa, S.; Arai, H. Epidemiology of sarcopenia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18 Suppl. 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzuya, M.; Sugimoto, K.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Kamibayashi, K.; Kurihara, T.; Fujimoto, M.; Arai, H. Prevention of sarcopenia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18 Suppl. 1, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K.; Hsiao, F.Y.; Akishita, M.; Assantachai, P.; Lee, W.J.; Lim, W.S.; Muangpaisan, W.; Kim, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Peng, L.N.; et al. A focus shift from sarcopenia to muscle health in the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2025 consensus update. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, A. Preclinical dysphagia in community dwelling older adults: What should we look for? Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2021, 30, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rech, R.S.; de Goulart, B.N.G.; Dos Santos, K.W.; Marcolino, M.A.Z.; Hilgert, J.B. Frequency and associated factors for swallowing impairment in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 2945–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, I.; Fujiu-Kurachi, M.; Arai, H.; Hyodo, M.; Kagaya, H.; Maeda, K.; Mori, T.; Nishioka, S.; Oshima, F.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Sarcopenia and dysphagia: Position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Nakayama, E.; Yoneoka, D.; Sakata, N.; Iijima, K.; Tanaka, T.; Hayashi, K.; Sakuma, K.; Hoshino, E. Association of oral function and dysphagia with frailty and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cells 2022, 11, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Koyama, S.; Kimura, Y.; Ishiyama, D.; Otobe, Y.; Nishio, N.; Ichikawa, T.; Kunieda, Y.; Ohji, S.; Ito, D.; Yamada, M. Relationship between characteristics of skeletal muscle and oral function in community-dwelling older women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 79, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, N.; Tohara, H.; Hara, K.; Kumakura, A.; Wakasugi, Y.; Nakane, A.; Minakuchi, S. Effects of aging and sarcopenia on tongue pressure and jaw-opening force. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugimiya, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Ohara, Y.; Motokawa, K.; Edahiro, A.; Shirobe, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Obuchi, S.; Kawai, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. Relationship between oral hypofunction and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: The Otassha Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugimiya, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Ohara, Y.; Motokawa, K.; Edahiro, A.; Shirobe, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Seino, S.; Abe, T.; et al. Association between sarcopenia and oral functions in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Todd, T.; Lintzenich, C.R.; Ding, J.; Carr, J.J.; Ge, Y.; Browne, J.D.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Butler, S.G. Aging-related geniohyoid muscle atrophy is related to aspiration status in healthy older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Honda, K.; Yamashita, T.; Saito, S.; Domen, K. Age-related composition changes in swallowing-related muscles: A Dixon MRI study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 3205–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Izumi, S.; Suzukamo, Y.; Okazaki, T.; Iketani, S. Ultrasonography to detect age-related changes in swallowing muscles. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 10, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, R.; Easterling, C.; Kern, M.; Nitschke, T.; Massey, B.; Daniels, S.; Grande, B.; Kazandjian, M.; Dikeman, K. Rehabilitation of swallowing by exercise in tube-fed patients with pharyngeal dysphagia secondary to abnormal UES opening. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mepani, R.; Antonik, S.; Massey, B.; Kern, M.; Logemann, J.; Pauloski, B.; Rademaker, A.; Easterling, C.; Shaker, R. Augmentation of deglutitive thyrohyoid muscle shortening by the Shaker exercise. Dysphagia 2009, 24, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Hwang, N.K. Chin tuck against resistance exercise for dysphagia rehabilitation: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, N.; Murakami, T.; Ando, M.; Sawada, T.; Hata, W.; Sakamoto, M. Reliability and validity of measuring the strength of the chin-tuck maneuver in community-dwelling older adults as a means of evaluating swallowing-related muscle strength. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crary, M.A.; Mann, G.D.; Groher, M.E. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 1516–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makizako, H.; Nakai, Y.; Tomioka, K.; Taniguchi, Y. Prevalence of sarcopenia defined using the Asia Working Group for Sarcopenia criteria in Japanese community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. Res. 2019, 22, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utanohara, Y.; Hayashi, R.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshida, M.; Tsuga, K.; Akagawa, Y. Standard values of maximum tongue pressure taken using newly developed disposable tongue pressure measurement device. Dysphagia 2008, 23, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Hirano, H.; Ikebe, K.; Ueda, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Minakuchi, S.; Arai, H.; Akishita, M.; Kozaki, K.; Iijima, K. Consensus statement on “Oral frailty” from the Japan Geriatrics Society, the Japanese Society of Gerodontology, and the Japanese Association on Sarcopenia and Frailty. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, W.; Shibata, H.; Nakazato, K.; Haga, H.; Suyama, Y. Measurement of competence: Reliability and validity of the TMIG Index of Competence. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1991, 13, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyl, M.T.; Alessi, C.A.; Harker, J.O.; Josephson, K.R.; Pietruszka, F.M.; Koelfgen, M.; Mervis, J.R.; Fitten, L.J.; Rubenstein, L.Z. Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B.; Garry, P.J. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr. Rev. 1996, 54, S59–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apfel, C.C.; Kranke, P.; Greim, C.A.; Roewer, N. What can be expected from risk scores for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting? Br. J. Anaesth. 2001, 86, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatta, K.; Ikebe, K. Association between oral health and sarcopenia: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, W.L.; Khoo, J.K.; Rickard Liow, S.J. Chin tuck against resistance (CTAR): New method for enhancing suprahyoid muscle activity using a Shaker-type exercise. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Jung, J.H.; Hahm, S.C.; Jung, K.S.; Suh, H.R.; Cho, H.Y. Effects of chin tuck exercise using neckline slimmer device on suprahyoid and sternocleidomastoid muscle activation in healthy adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.D.; Brajot, F.X.; Wang, H.I.; Han, D.S. Differential muscle activation during sustained chin-tuck against resistance (CTAR) contraction is consistent across different instructional conditions in older adults. Dysphagia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.H.; Oh, B.M.; Seo, H.G.; Lee, G.J.; Min, Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.C.; Han, T.R. Influence of the chin-down and chin-tuck maneuver on the swallowing kinematics of healthy adults. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, A.; Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Windsor, C.; Korim, Ž.; Tedla, M. Evaluating behavioural interventions for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of swallowing manoeuvres, exercises, and postural techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, M.; Goldenberg, D. Surgical anatomy and physiology of swallowing. Oper. Tech. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 27, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Hirano, H.; Kikutani, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Furuya, H.; Akishita, M.; Iijima, K. Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, Y.; Kamide, N.; Murakami, T.; Ichikura, K.; Murase, H.; Sakamoto, M.; Shiba, Y.; Tagaya, T. Correlation between depression and objective-subjective assessment of oral health among community-dwelling elderly. Rounenshakaigaku 2021, 43, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Hamdy, S. The upper oesophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2005, 17 Suppl. 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Suzuki, K.; Mikami, R.; Hidaka, R.; Jayatilake, D.; Srinivasan, M.; Kanazawa, M. Application of an artificial intelligence-assisted electronic stethoscope for evaluating swallowing function decline across age groups and sex in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2025, 25, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayoshi, M.; Higashi, M.; Takamura, N.; Tamai, M.; Koyamatsu, J.; Yamanashi, H.; Kadota, K.; Sato, S.; Kawashiri, S.Y.; Koyama, Z.; et al. Social networks, leisure activities and maximum tongue pressure: Cross-sectional associations in the Nagasaki Islands Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayoshi, M.; Tamai, M.; Takeuchi, K.; Yamanashi, H.; Koyamatsu, J.; Nonaka, F.; Nobusue, K.; Honda, Y.; Kawashiri, S.Y.; Nagata, Y.; et al. Frequency of conversation, laughter and other vocalising opportunities in daily life and maximum tongue pressure: The Goto Longevity Study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).